User login

How to Manage Family-Centered Rounds

From the Department of Pediatrics, George Washington University and Children’s National Medical Center, Washington, DC (Dr. Kern), the Department of Pediatrics, Children’s Hospital Los Angeles and University of Southern California Keck School of Medicine, Los Angeles, CA (Dr. Gay), and the Department of Pediatrics, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center and Children’s Health System, Dallas, TX (Dr. Mittal).

Abstract

- Objective: To present a model for operationalizing successful family-centered rounds (FCRs).

- Methods: Literature review and experience with leading FCR workshops at national meetings.

- Results: FCRs are multidisciplinary rounds that involve patients and families in decision-making. The model has gained substantial momentum nationally and is widely practiced in US pediatric hospitals. Many quality improvement–related FCR benefits have been identified, including improved parental satisfaction, communication, team-based practice, incorporation of practice guidelines, prevention of medication errors, and improved trainee and staff education and satisfaction. Physical and time constraints, variability in attending FCR style and teaching style, lack of FCR structure and process, specific and sensitive patient conditions, and language barriers are key challenges to implementing FCRs. Operationalizing a successful FCR program requires key stakeholders developing and defining a FCR process and structure, including developing a strong faculty development program.

- Conclusion: FCR benefits for a health care system are many. Key stakeholders involvement, developing FCR "ground rules," troubleshooting FCR barriers, and developing a strong faculty development program are key to managing successful FCRs.

The practice of medicine is a team sport and no team is complete without the patient and family being an integral part of it. Over the past 15 years, health care and the practice of medicine has slowly moved away from physician-centered care to patient- and family-centered care (FCC). This change has been a gradual shift in our culture and FCC has become a widely adopted philosophy within the US health care system [1]. FCC has been recognized and embraced by numerous medical and professional societies, including the Institute of Medicine (IOM), the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), and family advocacy organizations such as Family Voices and the Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care [1,2]. At its most basic, “family-centered care” occurs when patients/families and medical providers partner together to formulate medical plans that are built upon the sharing of open and unbiased information and that account for the diversity and individual strengths and needs of each patient and family unit [3]. FCC in the inpatient setting for hospitalized patients is most exemplified by the practice of family-centered (bedside) rounds, or FCRs [1].

Interestingly, FCC as a philosophy of care developed during a time when bedside rounds, and by extension clinical teaching, moved away from the bedside. Rounds are an integral part of how work is done in the inpatient setting. They come in many different flavors, from “pre-rounds” to “card-flip rounds” to “attending rounds,” “table/conference room rounds,” “hallway rounds,” “bedside rounds,” and the aforementioned family-centered rounds. In the first half of the 20th century,the majority of teaching rounds took place at the patient’s bedside, in the model advocated by Sir William Osler [4]. Indeed, as Dr. Osler wrote in 1903, “there should be no teaching without a patient for a text, and the best teaching is that taught by the patient himself” [5]. By the late 1970s through the mid-1990s, however, the proportion of clinical teaching occurring at the bedside had decreased to as low as 16% [6–8]. Many reasons behind the change have been speculated, including faculty comfort with lecture-based teaching and desire to control the content of teaching discussions, as well as technological advancement necessitating access to computers during case review.

In contrast, the patient-and family-centered movement began in the mid-20th century as a response to the separation trauma experienced by hospitalized children and their families [9]. Hospitals responded by liberalizing their visiting policies and encouraging direct care-giving by parents. FCC was further bolstered by consumer-led movements in the 1960s and 1970s, and by federal legislation in the 1980s targeting children with special health care needs. FCC gained national recognition in 2001 when the Institute of Medicine emphasized that involving patients and families in health care decisions increased the quality of their care [2]. Subsequently, the AAP endorsed FCC as a guiding approach to pediatric care in their 2003 report “Family-centered care and the pediatrician’s role” [1]. As part of this report, the AAP recommended that bedside presentations with active engagement of families become the standard of care. FCRs developed at several children’s hospitals in the US in the following years, with the first conceptual model of FCR published by Muething et al in 2007 [10].

Definition of Family-Centered Rounds

While no consensus definition of FCR exists, the most frequently cited description comes from Sisterhen et al who describe FCR as “interdisciplinary work rounds at the bedside in which the patient and family share in the control of the management plan as well as in the evaluation of the process itself” [11]. Three key features should be noted in this definition. First, FCR requires the active participation of family members, not merely their presence. In this way, patient and family voices are heard and their preferences solicited with respect to clinical decision-making. Second, FCR take place at the bedside, in alignment with the 2003 AAP policy statement that standard practice should be to conduct attending rounds with full case presentations in patient rooms in the presence of family. Third, FCR are typically interdisciplinary, involving patients and their families, physicians and trainees, nurses, and other ancillary staff (such as interpreters, case managers, and pharmacists) [1,10,11,12].

Since the IOM report, FCRs have gained substantial national momentum. A PRIS (Pediatric Research in Inpatient Setting) network study in 2010 published the first survey of pediatric hospitalist rounding practices in the US and Canada [12]. The study reported that 44% of pediatric hospitalists conducted FCRs, and about a quarter conducted rounds as hallway rounds or sit down rounds. Academic hospitalists were significantly more likely to conduct FCRs compared with non-academic (48% vs. 31%; P < 0.05) hospitalists. In accordance with Muething et al’s experience with FCRs in the Cincinnati model, the survey respondents did not associate FCR with prolonged rounding duration [10,12]. FCRs were also associated with greater bedside nurse participation [12]. Given the momentum behind FCC and the oft-cited benefits of FCR, it can only be presumed that the number of pediatric hospitals conducting FCR has significantly increased since the PRIS study was published in 2010.

FCRs Can Improve Quality of Care for Hospitalized Children

FCRs bring together multiple stakeholders involved in the patient’s care in the same place at the same time everyday. This allows for shared-decision making, identification of medical teams by families, and allows for direct and open communication between parents and medical teams [1,10–12]. The key stakeholders on a FCR team include the patient and family members and the medical team. The medical team includes attending physician, fellow, resident, and students, bedside nurse, care coordinator/case manager and other ancillary services. Although not enough data is available on who should attend rounds, case mangers and bedside nurse along with medical team and patients and families were found to be crucial in the general inpatient setting [12].

Integrating FCRs into the daily workflow in the inpatient setting provides several benefits for patients and families and the medical team, including trainees. Improvements in family-centered care principles, parental satisfaction, interdisciplinary team communication, efficiency, patient safety, and resident and medical student education have been reported consistently [9–23].

FCR Benefits for Patients and Families

Muething et al described increased patient-family satis-faction with higher levels of family participation in rounds and earlier discharge times [10]. On FCRs, families report having the opportunity to communicate directly with the entire care team, clarify misinformation and better understand care plans including discharge goals, leading to higher levels family satisfaction [10,14,24]. Both English and limited-English-proficient families report positive experiences with FCRs [21–23]. Families express appreciation with learning opportunities on FCRs, as well as the opportunity to serve as teachers to the medical team [14,16,21]. Families reported comfort with trainees being on rounds and appreciated seeing the medical personnel working as team [21]. They also report trust, comfort, and accountability towards the system and providers as they saw them working together as teams. They felt respected and involved as the medical teams involved them during rounds. Parents also report comfort with diversity of providers and feel that having multidisciplinary and diverse teams help with cultural competencies. Parents appreciated trainees being led by attending physician and felt that attending FCRs made them understand the medical process and the steps involved in caring for their child. They also reported that attending FCRs helps trainees learn about answering the kind of questions that parents usually ask. Contrary to the popular belief, parental participation has not increased the duration of FCRs and parental presence during rounds decreases time spent discussing each patient [14,25].

FCRs and Staff Satisfaction

Staff satisfaction with FCRs has been consistently high [13,14,18–23]. Nursing and medical staffs report valuing FCRs as they foster a sense of teamwork, improve understanding of the patient’s care plan and enhance communication between the care team and families [14]. FCRs significantly increase bedside nurse participation during rounds [12]. Presence of nursing and ancillary staff on FCRs improves efficiency by providing valuable information and helping address discharge goal [10]. Anecdotal data suggests that FCRs reduces number of pages trainees receive from nurses.

FCRs and Outcomes

FCRs have been perceived to improve in patient safety including errors in history taking and miscommunication, and incorrect information; and promote medication reconciliation, safety and adherence [17,20,21]. FCRs have shown to improve patient satisfaction, communication, and coordination of care and trainee education [10,14,21].

Educational Benefits of FCRs

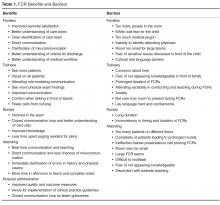

families (Table 1) [26].

FCR Benefits for Hospitals and Health Care Systems

As health care prepares to fully adopt reforms and shift from volume-based to value-based payment systems, creating value in every patient encounter is vital. Conducting daily FCRs provide an dynamic venue for hospitals where daily rounds can incorporate evidence-based practice guidelines, prevent medication errors, ensure safety, reduce unnecessary tests and treatments, and improve transparency and accountability in care. This model can help hospital financially by meeting key quality and safety metrics and also help provide cost effective care through use and reinforcement of clinical pathways during rounds.

FCR Barriers

While many hospitals have adopted FCRs, many barriers to FCR implementation exist [10–14,18–23] (Table 1). Understanding these barriers and overcoming them are crucial for successful implementation. Conducting FCRs involve many aspects of care that happen during rounds. These include discussions about history, physical examinations, labs, and other tests; clinical decision-making and communication between parents and providers; team communication; teaching of trainees; discharge planning; and coordination of care [20]. Given all these aspects of care involved during rounds, being able to conduct multidisciplinary rounds in a timely and efficient way can be a challenge in a busy and dynamic inpatient setting.

Key identified FCR barriers have included physical constraints such as small patient rooms, large team size, patients being on multiple floors or units, infection control precautions leading to increased time involved with teams gowning and gloving; lack of training on FCRs for trainees and faculty; language and cultural barriers; family/patient concerns of privacy/disclosure of sensitive information; trainee’s fears of not appearing knowledgeable in front of families; and variability in attending physicians’ teaching style and approach to FCR [10–15,21].

Operationalizing Successful FCRs

Forming FCR Steering Committee: Developing Ground Rules

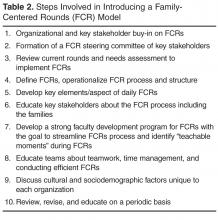

While there are many barriers to conducting efficient FCRs there are some that are unique to each institution. Therefore, for those institutions planning to initiate FCRs, the first step might be to form a FCR steering committee of key stakeholders who could review the current state, do a needs assessment for initiating FCRs, develop a structured and standardized FCR process and revise the FCR process periodically to meet the needs of the dynamic inpatient setting [10,12,14].

Defining and Identifying the FCR Process: Who, Where, and When of FCRs

The steering committee should clearly define FCRs and identify what FCRs would involve. For example, should FCRs involve complete case presentations and discussion in front of the parent or focused relevent H&P in a language that the parent understands? The steering committee should identify key elements/aspects of FCRs that would happen on daily rounds. For example: how should each patient receive information about FCRs? Should FCRs be offered to all patients? Do patients have options to opt-in or opt-out of FCRs on a daily basis or a one-time basis? Who should attend FCRs? For example, other than medical team, the bedside nurse and case manager should attend FCRs on a general pediatric service. Should the team round based on nursing assignments or resident assignments or in the order of room numbers? What should a typical rounding encounter involve? For example, each encounter should begin with the intern knocking on the door, asking parental permission for FCR team to enter the room, who should present, who should lead the rounds (the senior resident or the attending), who should stand where in the room? What should each encounter involve—for example, case presentation and discussion, parental involvement in decision-making, clarification of any parental questions, plan for that day, criteria for discharge and discharge needs assessment, teaching of resident and students, use of lay language etc. How should each rounding encounter end? Should the intern ask if parents have additional questions? It is important that the steering committee clearly identify these minute rounding details. Additionally, the committee should identify the rounding wards/area, the timing and duration of FCRs, how information about FCRs will be shared with patients and families, how trainees and attendees will be educated about FCRs and when are FCRs appropriate and when not. Defining the process early through stakeholder identification can reduce variability and create some standardization yet allow for individual style variations within the constraints of standardization. This will help reduced attending variability, which was cited as the most common FCR barrier by trainees.

As Seltz et al described, Latino families reported positive experiences with FCRs when a Spanish-speaking provider was involved. However, they report less satisfaction with telephone interpreters and did not feel empowered at times on FCRs due to language differences [23]. Addressing the language needs based on demographics and cultural needs will promote greater acceptance of FCRs [23].

Identifying and Defining Trainee Role

Participating in the FCR can create anxiety for medical students and residents. Therefore, educating them about the FCR process and structure beforehand and clearly defining roles can help them conceptualize their roles and expectation and ease their anxiety with FCRs. This will require the steering committee to collaboratively discuss how each encounter would look during FCR from a trainee’s perspective. Who will present the case? The third- year medical student versus the fourth-year medical student or the intern or based on case allocations? How should the case be presented? Should it be short and pointed presentation versus complete history and physical examination on each patient? How long should an encounter last on a new patient and on a follow-up patient? Who will examine the patient? The student who is presenting the case, the attending, the intern who overlooks the student, or the senior resident? Who will answer the follow-up questions from a parent initially? Should the senior resident lead the team under the attending guidance? How will the senior resident be prepared for morning rounds? Using lay language when talking to parents should be encouraged and taught to trainees routinely during FCRs.

Identifying and Defining Clinical Teaching Styles

Faculty Development Program and Importance of “Safe Environment”

Developing an educational program to train faculty, trainee and staff about FCRs can help streamline FCRs. Conducting FCRs is a cultural change and focusing on early adopters is crucial. Muething et al’s model showed better acceptance of FCRs by interns than by senior residents. Being patient during change management is key to successful implementation. Anecdotal discussions during PAS workshops suggests that on an average programs have required 3 years to get significant buy-in and streamlining of FCRs [10,12].

Suboptimal attending behavior such as attending variability in the FCRs process and teaching strategies have been reported as FCR barriers [14,21]. Residents report attending physician as an important factor determining success of FCRs. As attending physicians typically are the leaders of the FCRs team, training faculty about conducting effective and efficient FCRs is crucial to successful FCRs. [12,21]. Key aspects of faculty development should include: (1) education about the FCR standard process for the institution, (2) importance of time management during rounds, including tips and strategies to be efficient, (3) teaching styles during FCRs, including demonstrating role modeling, and (4) direct observation of trainees and individual and team feedback to streamline FCRs. Role-plays or simulated FCRs might be a venue to explore for faculty development on FCRs [14,21].

Creating a “safe environment” during FCRs where each person feels comfortable and secure is vital to team work [7,12,21]. Often trainees are apprehensive or afraid due to medical hierarchy and this might prevent developing a teaching and learning environment. Trainees fear not appearing knowledgeable in front of families and student rotate too often to adapt to different attending styles [21]. Therefore, reassuring trainees that the goal of FCRs is to conduct daily inpatient rounding to ensure key aspects of FCRs are met without disrespecting and insulting any person on rounds and clarifying and reassuring trainees that their fear of not appearing knowledgeable is real and it will be respected, might help create a safe environment where FCR teams are not only conducting the daily ritual of inpatient rounding, and teaching but also ensuring that trainees are enjoying being the clinician and physicians that they want to be. Therefore, attending role modeling is crucial and it is no surprise that in multiple studies variability in attending rounding and teaching style was identified consistently as a FCR barrier.

Preparing for Daily FCRS: Team Work, Efficiency, and Time Management

Conducting daily timely and efficient rounds require daily preparation by teams. Prior to FCRs, teams should know about all of the patients on whom FCRs will be conducted including those who refused FCRs, if any. This can be done via a pre-round or card-flip rounding method where the teams discuss key diagnoses, indication for admission, and identify any outliers to conducting FCRs such as sensitive patient condition, patients refused FCRs, etc. Some institutions have incorporated these at “morning check out” or at morning “huddles.” These help faculty avoid any last minute surprises during rounds and helps with time management during FCRs [12]. Faculty can then plan on some anticipated “teaching moments” before rounds to keep the rounds flowing, for example, a physical exam finding, a clarifying history that can clinch a diagnoses, a clinical pearl, a complex medical case where the parent might share their story and knowledge, an interesting interpretation of a lab, an x-ray or MRI finding. Faculties are multitasking during FCRs by diagnosing and managing patient and learners and leading effective efficient and timely rounds where parental questions are answered, orders are written, to-do work is identified, discharge planning and care coordination is done and trainees stay focused and attend noon conference on time. This requires thoughtful planning before starting FCRs. Time management and managing priorities is key to positive team experiences of FCRs. Both starting and ending FCRs on time should be emphasized and reinforced continually.

Nurse Preparation for FCRs

Nurses are the frontline providers and educating them about FCRs process can help them better explain FCRs to patients and families. Nurses often know the minute details such as timing of an MRI, if the patient has vomited in the morning, or when the parents are coming, etc. This important information sharing during FCRs can help team prepare for the day and provide patients and families’ expectations for the day. Nursing participation can also enhance their knowledge about the thought process behind decisions and care plans and avoid additional time paging house staff to obtain clarification [12–15,21].

Trainee Preparation for FCRs

While pediatric residents do report that FCRs leads to fewer requests for clarifications from families and nurses after FCRs, many still harbor concerns about the time required for FCRs and the overall efficiency of rounds [14]. Educating trainees about the FCR process and explaining why FCRs are beneficial can help alleviate trainee anxiety around FCRs. Involving trainees in the FCR communication and creating a safe and nurturing environment during FCRs can further reduce trainee anxiety [21]. Parents who have attended FCRs with trainees report understanding that trainees are in training and that they have felt comfortable to see attending physician lead the trainees.

FCRs and Technology

Use of technology during FCRs can be helpful to write orders in real time, follow-up and share lab values and or imaging study with parents or teach students. The increasing use of technology on FCRs, such as computers and handheld devices, can help with rounding and teaching; however, it also has the potential to be a distractor and requires that the medical team remain vigilant that the patient and family are the focus of FCRs [26].

Efficiency Pearls

Certain strategies can be utilized to keep FCRs efficient:

- Orient the FCR team about FCR process

- Identify rounding sequence for the day so team can move efficiently between rooms. Identifying potential discharges for the following morning and discharging those patients before rounds can reduce rounding census and provide additional rounding time. Teams can identify approximate time spent in each room based on census, as rounding time is constant.

- Starting and ending FCRs at the allocated time is key to success of FCRs. Sometimes this might require the attending and senior resident splitting the last 1–2 patients to finish rounds on time.

- Prepare students and interns for effective and efficient yet complete presentations during rounds that reflect their knowledge and thought process rather than presenting the entire H&P.

- Keep teaching during rounds focused. As a resident reported, “attendings should keep it short and not go off on a half hour lecture during FCRs. On FCRs I want to hear bam…bam…bam! tidbits, little hints, clinical pearls. Things that you would not know and only see and know when you were there in the room [21].”

- Encourage and teach senior residents’ role as a leader and teacher [21].

- With a situation requiring more time talking to families, request to go back later in the afternoon so as to stay on track on FCR time.

- Faculty can review lab results and history and physical findings on new admissions before rounds to avoid surprises during FCRs and to save time. This can be done during pre-round/card flip/or morning huddle.

Limitations

This article is based on the authors’ review of literature, experience in conducting FCRs, and experience from leading and attending FCR-related workshops at annual pediatric academic societies’ meetings and annual pediatric hospital medicine meetings between 2010 and 2015. There are several limitations to this work. Firstly, the majority of FCR literature is based on perceptions and are not measured outcomes. In addition, how FCRs will apply on services with complex patients needs more study. Different institutions have different physical constraints as well as sociodemographic and cultural factors that might affect FCRs. Daily census among hospitals varies and rounding duration may vary for them.

Conclusion

Family-centered rounds are widely accepted among pediatric hospitalists in the US. Reported benefits of FCRs include improved parent satisfaction, communication, better team communication, improved patient safety and better education for trainees. Many barriers to efficient FCRs exist, and for programs planning to incorporate FCRs in their daily rounds it is crucial to understand FCR benefits and barriers and assess their current state, including physical environment, when planning FCRs. Having a period to plan for FCR implementation through key stakeholder involvement helps define FCR process and lay down a conceptual model suited to individual organization. Educating the team members including families about FCRs and developing a strong faculty development program can further strengthen FCR implementation. Special focus should be given to time management, teaching styles during FCRs, and creating a safe and nurturing environment for FCRs to succeed.

Corresponding author: Vineeta Mittal, MD, MBA, 1935 Medical District Dr., Dallas, TX 75235, vineeta.mittal@childrens.com.

1. American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Hospital Care. Family-centered care and the pediatrician’s role. Pediatrics 2003;112:691–7.

2. Institute of Medicine, Committee on Quality Health Care in America. Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2001.

3. Kuo DZ, Joutrow AJ, Arango P, et al. Family-centered care: current applications and future directions in pediatric health care. Matern Child Health J 2012;16:297–305.

4. Reichsman F, Browning FE, Hinshaw JR. Observations of undergraduate clinical teaching in action. J Med Educ 1964;39:147–63.

5. Osler W. On the need of a radical reform in our methods of teaching senior students. Med News 1903;82:49–53.

6. Collins GF, Cassie JM, Dagget CJ. The role of the attending physician in clinical training. J Med Educ 1978;53:429–31.

7. Lacombe MA. On bedside teaching. Ann Intern Med 1997;126:217–20.

8. Linfors EW, Neelon FA. Sounding board. The case of bedside rounds. N Engl J Med 1980;303:1230–3.

9. Jolley J, Shields J. The evolution of family-centered care. J Pediatr Nursing 2009;42:164–70.

10. Muething SE, Kotagal UR, Schoettker PJ, et al. Family-centered rounds: a new approach to patient care and teaching. Pediatrics 2007;119:829–32.

11. Sisterhen LL, Blaszak RT, Woods MB, Smith CE. Defining family-centered rounds. Teach Learn Med 2007;19:319–22.

12. Mittal V, Sigrest T, Ottolini M, et al. Family-centered rounds on pediatric wards: a PRIS network survey of Canadian and US hospitalists. Pediatrics 2010;126:37–43.

13. Rosen P, Stenger E, Bochkoris M, et al. Family-centered multidisciplinary rounds enhance the team approach in pediatrics. Pediatrics 2009;123:e603–8.

14. Rappaport DI, Ketterer TA, Nilforoshan V, Sharif I. Family-centered rounds: views of families, nurses, trainees, and attending physicians. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2012;51:260–6.

15. Young HN, Schumacher JB, Moreno MA, et al. Medical student self-efficacy with family-centered care during bedside rounds. Acad Med 2012;87:767–75.

16. Beck J, Meyer R, Kind T, Bhansali B. The importance of situational awareness: a qualitative study of family members’ and nurses’ perspectives on teaching during family-centered rounds. Acad Med 2015 Jul 21. Epub ahead of print.

17. Benjamin J, Cox E, Trapskin P, et al. Family-initiated dialogue about medicaitons during family-centered rounds. Pediatrics 2015;135:94–100.

18. Cox E, Schumacher J, Young H, et al. Medical student outcomes after family-centered bedside rounds. Acad Pediatri 2011;11:403–8.

19. Latta LC, Dick R, Parry C, Tamura GS. Parental responses to involvement in rounds on a pediatric inpatient unit at a teaching hospital: a qualitative study. Acad Med 2008;83:292–7.

20. Mittal V. Family-centered rounds. Pediatr Clin North Am 2014;61:663–70.

21. Mittal V, Krieger E, Lee B, et al. Pediatric residents’ perspectives on family-centered rounds - a qualitative study at 2 children’s hospitals. J Grad Med Educ 2013;5:81–7.

22. Lion KC, Mangione-Smith R, Martyn M, et al. Comprehension on family-centered rounds for limited English proficient families. Acad Pediatr 2013;13:236–42.

23. Seltz LB, Zimmer L, Ochoa-Nunez L, et al. Latino families’ experiences with family-centered rounds at an academic children’s hospital. Acad Pediatr 2011;11:432–8.

24. Kuo DZ, Sisterhen LL, Sigrest TE, et al. Family experiences and pediatric health services use associated with family-centered rounds. Pediatrics 2012;130:299–305.

25. Bhansali P, Birch S, Campbell JK, et al. A time-motion study of inpatient rounds using a family-centered rounds model. Hosp Pediatr 2013;3:31–8.

26. Kern J, Bhansali P. Handheld electronic device use by pediatric hospitalists on family centered rounds. J Med Syst 2016;40:9.

From the Department of Pediatrics, George Washington University and Children’s National Medical Center, Washington, DC (Dr. Kern), the Department of Pediatrics, Children’s Hospital Los Angeles and University of Southern California Keck School of Medicine, Los Angeles, CA (Dr. Gay), and the Department of Pediatrics, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center and Children’s Health System, Dallas, TX (Dr. Mittal).

Abstract

- Objective: To present a model for operationalizing successful family-centered rounds (FCRs).

- Methods: Literature review and experience with leading FCR workshops at national meetings.

- Results: FCRs are multidisciplinary rounds that involve patients and families in decision-making. The model has gained substantial momentum nationally and is widely practiced in US pediatric hospitals. Many quality improvement–related FCR benefits have been identified, including improved parental satisfaction, communication, team-based practice, incorporation of practice guidelines, prevention of medication errors, and improved trainee and staff education and satisfaction. Physical and time constraints, variability in attending FCR style and teaching style, lack of FCR structure and process, specific and sensitive patient conditions, and language barriers are key challenges to implementing FCRs. Operationalizing a successful FCR program requires key stakeholders developing and defining a FCR process and structure, including developing a strong faculty development program.

- Conclusion: FCR benefits for a health care system are many. Key stakeholders involvement, developing FCR "ground rules," troubleshooting FCR barriers, and developing a strong faculty development program are key to managing successful FCRs.

The practice of medicine is a team sport and no team is complete without the patient and family being an integral part of it. Over the past 15 years, health care and the practice of medicine has slowly moved away from physician-centered care to patient- and family-centered care (FCC). This change has been a gradual shift in our culture and FCC has become a widely adopted philosophy within the US health care system [1]. FCC has been recognized and embraced by numerous medical and professional societies, including the Institute of Medicine (IOM), the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), and family advocacy organizations such as Family Voices and the Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care [1,2]. At its most basic, “family-centered care” occurs when patients/families and medical providers partner together to formulate medical plans that are built upon the sharing of open and unbiased information and that account for the diversity and individual strengths and needs of each patient and family unit [3]. FCC in the inpatient setting for hospitalized patients is most exemplified by the practice of family-centered (bedside) rounds, or FCRs [1].

Interestingly, FCC as a philosophy of care developed during a time when bedside rounds, and by extension clinical teaching, moved away from the bedside. Rounds are an integral part of how work is done in the inpatient setting. They come in many different flavors, from “pre-rounds” to “card-flip rounds” to “attending rounds,” “table/conference room rounds,” “hallway rounds,” “bedside rounds,” and the aforementioned family-centered rounds. In the first half of the 20th century,the majority of teaching rounds took place at the patient’s bedside, in the model advocated by Sir William Osler [4]. Indeed, as Dr. Osler wrote in 1903, “there should be no teaching without a patient for a text, and the best teaching is that taught by the patient himself” [5]. By the late 1970s through the mid-1990s, however, the proportion of clinical teaching occurring at the bedside had decreased to as low as 16% [6–8]. Many reasons behind the change have been speculated, including faculty comfort with lecture-based teaching and desire to control the content of teaching discussions, as well as technological advancement necessitating access to computers during case review.

In contrast, the patient-and family-centered movement began in the mid-20th century as a response to the separation trauma experienced by hospitalized children and their families [9]. Hospitals responded by liberalizing their visiting policies and encouraging direct care-giving by parents. FCC was further bolstered by consumer-led movements in the 1960s and 1970s, and by federal legislation in the 1980s targeting children with special health care needs. FCC gained national recognition in 2001 when the Institute of Medicine emphasized that involving patients and families in health care decisions increased the quality of their care [2]. Subsequently, the AAP endorsed FCC as a guiding approach to pediatric care in their 2003 report “Family-centered care and the pediatrician’s role” [1]. As part of this report, the AAP recommended that bedside presentations with active engagement of families become the standard of care. FCRs developed at several children’s hospitals in the US in the following years, with the first conceptual model of FCR published by Muething et al in 2007 [10].

Definition of Family-Centered Rounds

While no consensus definition of FCR exists, the most frequently cited description comes from Sisterhen et al who describe FCR as “interdisciplinary work rounds at the bedside in which the patient and family share in the control of the management plan as well as in the evaluation of the process itself” [11]. Three key features should be noted in this definition. First, FCR requires the active participation of family members, not merely their presence. In this way, patient and family voices are heard and their preferences solicited with respect to clinical decision-making. Second, FCR take place at the bedside, in alignment with the 2003 AAP policy statement that standard practice should be to conduct attending rounds with full case presentations in patient rooms in the presence of family. Third, FCR are typically interdisciplinary, involving patients and their families, physicians and trainees, nurses, and other ancillary staff (such as interpreters, case managers, and pharmacists) [1,10,11,12].

Since the IOM report, FCRs have gained substantial national momentum. A PRIS (Pediatric Research in Inpatient Setting) network study in 2010 published the first survey of pediatric hospitalist rounding practices in the US and Canada [12]. The study reported that 44% of pediatric hospitalists conducted FCRs, and about a quarter conducted rounds as hallway rounds or sit down rounds. Academic hospitalists were significantly more likely to conduct FCRs compared with non-academic (48% vs. 31%; P < 0.05) hospitalists. In accordance with Muething et al’s experience with FCRs in the Cincinnati model, the survey respondents did not associate FCR with prolonged rounding duration [10,12]. FCRs were also associated with greater bedside nurse participation [12]. Given the momentum behind FCC and the oft-cited benefits of FCR, it can only be presumed that the number of pediatric hospitals conducting FCR has significantly increased since the PRIS study was published in 2010.

FCRs Can Improve Quality of Care for Hospitalized Children

FCRs bring together multiple stakeholders involved in the patient’s care in the same place at the same time everyday. This allows for shared-decision making, identification of medical teams by families, and allows for direct and open communication between parents and medical teams [1,10–12]. The key stakeholders on a FCR team include the patient and family members and the medical team. The medical team includes attending physician, fellow, resident, and students, bedside nurse, care coordinator/case manager and other ancillary services. Although not enough data is available on who should attend rounds, case mangers and bedside nurse along with medical team and patients and families were found to be crucial in the general inpatient setting [12].

Integrating FCRs into the daily workflow in the inpatient setting provides several benefits for patients and families and the medical team, including trainees. Improvements in family-centered care principles, parental satisfaction, interdisciplinary team communication, efficiency, patient safety, and resident and medical student education have been reported consistently [9–23].

FCR Benefits for Patients and Families

Muething et al described increased patient-family satis-faction with higher levels of family participation in rounds and earlier discharge times [10]. On FCRs, families report having the opportunity to communicate directly with the entire care team, clarify misinformation and better understand care plans including discharge goals, leading to higher levels family satisfaction [10,14,24]. Both English and limited-English-proficient families report positive experiences with FCRs [21–23]. Families express appreciation with learning opportunities on FCRs, as well as the opportunity to serve as teachers to the medical team [14,16,21]. Families reported comfort with trainees being on rounds and appreciated seeing the medical personnel working as team [21]. They also report trust, comfort, and accountability towards the system and providers as they saw them working together as teams. They felt respected and involved as the medical teams involved them during rounds. Parents also report comfort with diversity of providers and feel that having multidisciplinary and diverse teams help with cultural competencies. Parents appreciated trainees being led by attending physician and felt that attending FCRs made them understand the medical process and the steps involved in caring for their child. They also reported that attending FCRs helps trainees learn about answering the kind of questions that parents usually ask. Contrary to the popular belief, parental participation has not increased the duration of FCRs and parental presence during rounds decreases time spent discussing each patient [14,25].

FCRs and Staff Satisfaction

Staff satisfaction with FCRs has been consistently high [13,14,18–23]. Nursing and medical staffs report valuing FCRs as they foster a sense of teamwork, improve understanding of the patient’s care plan and enhance communication between the care team and families [14]. FCRs significantly increase bedside nurse participation during rounds [12]. Presence of nursing and ancillary staff on FCRs improves efficiency by providing valuable information and helping address discharge goal [10]. Anecdotal data suggests that FCRs reduces number of pages trainees receive from nurses.

FCRs and Outcomes

FCRs have been perceived to improve in patient safety including errors in history taking and miscommunication, and incorrect information; and promote medication reconciliation, safety and adherence [17,20,21]. FCRs have shown to improve patient satisfaction, communication, and coordination of care and trainee education [10,14,21].

Educational Benefits of FCRs

families (Table 1) [26].

FCR Benefits for Hospitals and Health Care Systems

As health care prepares to fully adopt reforms and shift from volume-based to value-based payment systems, creating value in every patient encounter is vital. Conducting daily FCRs provide an dynamic venue for hospitals where daily rounds can incorporate evidence-based practice guidelines, prevent medication errors, ensure safety, reduce unnecessary tests and treatments, and improve transparency and accountability in care. This model can help hospital financially by meeting key quality and safety metrics and also help provide cost effective care through use and reinforcement of clinical pathways during rounds.

FCR Barriers

While many hospitals have adopted FCRs, many barriers to FCR implementation exist [10–14,18–23] (Table 1). Understanding these barriers and overcoming them are crucial for successful implementation. Conducting FCRs involve many aspects of care that happen during rounds. These include discussions about history, physical examinations, labs, and other tests; clinical decision-making and communication between parents and providers; team communication; teaching of trainees; discharge planning; and coordination of care [20]. Given all these aspects of care involved during rounds, being able to conduct multidisciplinary rounds in a timely and efficient way can be a challenge in a busy and dynamic inpatient setting.

Key identified FCR barriers have included physical constraints such as small patient rooms, large team size, patients being on multiple floors or units, infection control precautions leading to increased time involved with teams gowning and gloving; lack of training on FCRs for trainees and faculty; language and cultural barriers; family/patient concerns of privacy/disclosure of sensitive information; trainee’s fears of not appearing knowledgeable in front of families; and variability in attending physicians’ teaching style and approach to FCR [10–15,21].

Operationalizing Successful FCRs

Forming FCR Steering Committee: Developing Ground Rules

While there are many barriers to conducting efficient FCRs there are some that are unique to each institution. Therefore, for those institutions planning to initiate FCRs, the first step might be to form a FCR steering committee of key stakeholders who could review the current state, do a needs assessment for initiating FCRs, develop a structured and standardized FCR process and revise the FCR process periodically to meet the needs of the dynamic inpatient setting [10,12,14].

Defining and Identifying the FCR Process: Who, Where, and When of FCRs

The steering committee should clearly define FCRs and identify what FCRs would involve. For example, should FCRs involve complete case presentations and discussion in front of the parent or focused relevent H&P in a language that the parent understands? The steering committee should identify key elements/aspects of FCRs that would happen on daily rounds. For example: how should each patient receive information about FCRs? Should FCRs be offered to all patients? Do patients have options to opt-in or opt-out of FCRs on a daily basis or a one-time basis? Who should attend FCRs? For example, other than medical team, the bedside nurse and case manager should attend FCRs on a general pediatric service. Should the team round based on nursing assignments or resident assignments or in the order of room numbers? What should a typical rounding encounter involve? For example, each encounter should begin with the intern knocking on the door, asking parental permission for FCR team to enter the room, who should present, who should lead the rounds (the senior resident or the attending), who should stand where in the room? What should each encounter involve—for example, case presentation and discussion, parental involvement in decision-making, clarification of any parental questions, plan for that day, criteria for discharge and discharge needs assessment, teaching of resident and students, use of lay language etc. How should each rounding encounter end? Should the intern ask if parents have additional questions? It is important that the steering committee clearly identify these minute rounding details. Additionally, the committee should identify the rounding wards/area, the timing and duration of FCRs, how information about FCRs will be shared with patients and families, how trainees and attendees will be educated about FCRs and when are FCRs appropriate and when not. Defining the process early through stakeholder identification can reduce variability and create some standardization yet allow for individual style variations within the constraints of standardization. This will help reduced attending variability, which was cited as the most common FCR barrier by trainees.

As Seltz et al described, Latino families reported positive experiences with FCRs when a Spanish-speaking provider was involved. However, they report less satisfaction with telephone interpreters and did not feel empowered at times on FCRs due to language differences [23]. Addressing the language needs based on demographics and cultural needs will promote greater acceptance of FCRs [23].

Identifying and Defining Trainee Role

Participating in the FCR can create anxiety for medical students and residents. Therefore, educating them about the FCR process and structure beforehand and clearly defining roles can help them conceptualize their roles and expectation and ease their anxiety with FCRs. This will require the steering committee to collaboratively discuss how each encounter would look during FCR from a trainee’s perspective. Who will present the case? The third- year medical student versus the fourth-year medical student or the intern or based on case allocations? How should the case be presented? Should it be short and pointed presentation versus complete history and physical examination on each patient? How long should an encounter last on a new patient and on a follow-up patient? Who will examine the patient? The student who is presenting the case, the attending, the intern who overlooks the student, or the senior resident? Who will answer the follow-up questions from a parent initially? Should the senior resident lead the team under the attending guidance? How will the senior resident be prepared for morning rounds? Using lay language when talking to parents should be encouraged and taught to trainees routinely during FCRs.

Identifying and Defining Clinical Teaching Styles

Faculty Development Program and Importance of “Safe Environment”

Developing an educational program to train faculty, trainee and staff about FCRs can help streamline FCRs. Conducting FCRs is a cultural change and focusing on early adopters is crucial. Muething et al’s model showed better acceptance of FCRs by interns than by senior residents. Being patient during change management is key to successful implementation. Anecdotal discussions during PAS workshops suggests that on an average programs have required 3 years to get significant buy-in and streamlining of FCRs [10,12].

Suboptimal attending behavior such as attending variability in the FCRs process and teaching strategies have been reported as FCR barriers [14,21]. Residents report attending physician as an important factor determining success of FCRs. As attending physicians typically are the leaders of the FCRs team, training faculty about conducting effective and efficient FCRs is crucial to successful FCRs. [12,21]. Key aspects of faculty development should include: (1) education about the FCR standard process for the institution, (2) importance of time management during rounds, including tips and strategies to be efficient, (3) teaching styles during FCRs, including demonstrating role modeling, and (4) direct observation of trainees and individual and team feedback to streamline FCRs. Role-plays or simulated FCRs might be a venue to explore for faculty development on FCRs [14,21].

Creating a “safe environment” during FCRs where each person feels comfortable and secure is vital to team work [7,12,21]. Often trainees are apprehensive or afraid due to medical hierarchy and this might prevent developing a teaching and learning environment. Trainees fear not appearing knowledgeable in front of families and student rotate too often to adapt to different attending styles [21]. Therefore, reassuring trainees that the goal of FCRs is to conduct daily inpatient rounding to ensure key aspects of FCRs are met without disrespecting and insulting any person on rounds and clarifying and reassuring trainees that their fear of not appearing knowledgeable is real and it will be respected, might help create a safe environment where FCR teams are not only conducting the daily ritual of inpatient rounding, and teaching but also ensuring that trainees are enjoying being the clinician and physicians that they want to be. Therefore, attending role modeling is crucial and it is no surprise that in multiple studies variability in attending rounding and teaching style was identified consistently as a FCR barrier.

Preparing for Daily FCRS: Team Work, Efficiency, and Time Management

Conducting daily timely and efficient rounds require daily preparation by teams. Prior to FCRs, teams should know about all of the patients on whom FCRs will be conducted including those who refused FCRs, if any. This can be done via a pre-round or card-flip rounding method where the teams discuss key diagnoses, indication for admission, and identify any outliers to conducting FCRs such as sensitive patient condition, patients refused FCRs, etc. Some institutions have incorporated these at “morning check out” or at morning “huddles.” These help faculty avoid any last minute surprises during rounds and helps with time management during FCRs [12]. Faculty can then plan on some anticipated “teaching moments” before rounds to keep the rounds flowing, for example, a physical exam finding, a clarifying history that can clinch a diagnoses, a clinical pearl, a complex medical case where the parent might share their story and knowledge, an interesting interpretation of a lab, an x-ray or MRI finding. Faculties are multitasking during FCRs by diagnosing and managing patient and learners and leading effective efficient and timely rounds where parental questions are answered, orders are written, to-do work is identified, discharge planning and care coordination is done and trainees stay focused and attend noon conference on time. This requires thoughtful planning before starting FCRs. Time management and managing priorities is key to positive team experiences of FCRs. Both starting and ending FCRs on time should be emphasized and reinforced continually.

Nurse Preparation for FCRs

Nurses are the frontline providers and educating them about FCRs process can help them better explain FCRs to patients and families. Nurses often know the minute details such as timing of an MRI, if the patient has vomited in the morning, or when the parents are coming, etc. This important information sharing during FCRs can help team prepare for the day and provide patients and families’ expectations for the day. Nursing participation can also enhance their knowledge about the thought process behind decisions and care plans and avoid additional time paging house staff to obtain clarification [12–15,21].

Trainee Preparation for FCRs

While pediatric residents do report that FCRs leads to fewer requests for clarifications from families and nurses after FCRs, many still harbor concerns about the time required for FCRs and the overall efficiency of rounds [14]. Educating trainees about the FCR process and explaining why FCRs are beneficial can help alleviate trainee anxiety around FCRs. Involving trainees in the FCR communication and creating a safe and nurturing environment during FCRs can further reduce trainee anxiety [21]. Parents who have attended FCRs with trainees report understanding that trainees are in training and that they have felt comfortable to see attending physician lead the trainees.

FCRs and Technology

Use of technology during FCRs can be helpful to write orders in real time, follow-up and share lab values and or imaging study with parents or teach students. The increasing use of technology on FCRs, such as computers and handheld devices, can help with rounding and teaching; however, it also has the potential to be a distractor and requires that the medical team remain vigilant that the patient and family are the focus of FCRs [26].

Efficiency Pearls

Certain strategies can be utilized to keep FCRs efficient:

- Orient the FCR team about FCR process

- Identify rounding sequence for the day so team can move efficiently between rooms. Identifying potential discharges for the following morning and discharging those patients before rounds can reduce rounding census and provide additional rounding time. Teams can identify approximate time spent in each room based on census, as rounding time is constant.

- Starting and ending FCRs at the allocated time is key to success of FCRs. Sometimes this might require the attending and senior resident splitting the last 1–2 patients to finish rounds on time.

- Prepare students and interns for effective and efficient yet complete presentations during rounds that reflect their knowledge and thought process rather than presenting the entire H&P.

- Keep teaching during rounds focused. As a resident reported, “attendings should keep it short and not go off on a half hour lecture during FCRs. On FCRs I want to hear bam…bam…bam! tidbits, little hints, clinical pearls. Things that you would not know and only see and know when you were there in the room [21].”

- Encourage and teach senior residents’ role as a leader and teacher [21].

- With a situation requiring more time talking to families, request to go back later in the afternoon so as to stay on track on FCR time.

- Faculty can review lab results and history and physical findings on new admissions before rounds to avoid surprises during FCRs and to save time. This can be done during pre-round/card flip/or morning huddle.

Limitations

This article is based on the authors’ review of literature, experience in conducting FCRs, and experience from leading and attending FCR-related workshops at annual pediatric academic societies’ meetings and annual pediatric hospital medicine meetings between 2010 and 2015. There are several limitations to this work. Firstly, the majority of FCR literature is based on perceptions and are not measured outcomes. In addition, how FCRs will apply on services with complex patients needs more study. Different institutions have different physical constraints as well as sociodemographic and cultural factors that might affect FCRs. Daily census among hospitals varies and rounding duration may vary for them.

Conclusion

Family-centered rounds are widely accepted among pediatric hospitalists in the US. Reported benefits of FCRs include improved parent satisfaction, communication, better team communication, improved patient safety and better education for trainees. Many barriers to efficient FCRs exist, and for programs planning to incorporate FCRs in their daily rounds it is crucial to understand FCR benefits and barriers and assess their current state, including physical environment, when planning FCRs. Having a period to plan for FCR implementation through key stakeholder involvement helps define FCR process and lay down a conceptual model suited to individual organization. Educating the team members including families about FCRs and developing a strong faculty development program can further strengthen FCR implementation. Special focus should be given to time management, teaching styles during FCRs, and creating a safe and nurturing environment for FCRs to succeed.

Corresponding author: Vineeta Mittal, MD, MBA, 1935 Medical District Dr., Dallas, TX 75235, vineeta.mittal@childrens.com.

From the Department of Pediatrics, George Washington University and Children’s National Medical Center, Washington, DC (Dr. Kern), the Department of Pediatrics, Children’s Hospital Los Angeles and University of Southern California Keck School of Medicine, Los Angeles, CA (Dr. Gay), and the Department of Pediatrics, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center and Children’s Health System, Dallas, TX (Dr. Mittal).

Abstract

- Objective: To present a model for operationalizing successful family-centered rounds (FCRs).

- Methods: Literature review and experience with leading FCR workshops at national meetings.

- Results: FCRs are multidisciplinary rounds that involve patients and families in decision-making. The model has gained substantial momentum nationally and is widely practiced in US pediatric hospitals. Many quality improvement–related FCR benefits have been identified, including improved parental satisfaction, communication, team-based practice, incorporation of practice guidelines, prevention of medication errors, and improved trainee and staff education and satisfaction. Physical and time constraints, variability in attending FCR style and teaching style, lack of FCR structure and process, specific and sensitive patient conditions, and language barriers are key challenges to implementing FCRs. Operationalizing a successful FCR program requires key stakeholders developing and defining a FCR process and structure, including developing a strong faculty development program.

- Conclusion: FCR benefits for a health care system are many. Key stakeholders involvement, developing FCR "ground rules," troubleshooting FCR barriers, and developing a strong faculty development program are key to managing successful FCRs.

The practice of medicine is a team sport and no team is complete without the patient and family being an integral part of it. Over the past 15 years, health care and the practice of medicine has slowly moved away from physician-centered care to patient- and family-centered care (FCC). This change has been a gradual shift in our culture and FCC has become a widely adopted philosophy within the US health care system [1]. FCC has been recognized and embraced by numerous medical and professional societies, including the Institute of Medicine (IOM), the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), and family advocacy organizations such as Family Voices and the Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care [1,2]. At its most basic, “family-centered care” occurs when patients/families and medical providers partner together to formulate medical plans that are built upon the sharing of open and unbiased information and that account for the diversity and individual strengths and needs of each patient and family unit [3]. FCC in the inpatient setting for hospitalized patients is most exemplified by the practice of family-centered (bedside) rounds, or FCRs [1].

Interestingly, FCC as a philosophy of care developed during a time when bedside rounds, and by extension clinical teaching, moved away from the bedside. Rounds are an integral part of how work is done in the inpatient setting. They come in many different flavors, from “pre-rounds” to “card-flip rounds” to “attending rounds,” “table/conference room rounds,” “hallway rounds,” “bedside rounds,” and the aforementioned family-centered rounds. In the first half of the 20th century,the majority of teaching rounds took place at the patient’s bedside, in the model advocated by Sir William Osler [4]. Indeed, as Dr. Osler wrote in 1903, “there should be no teaching without a patient for a text, and the best teaching is that taught by the patient himself” [5]. By the late 1970s through the mid-1990s, however, the proportion of clinical teaching occurring at the bedside had decreased to as low as 16% [6–8]. Many reasons behind the change have been speculated, including faculty comfort with lecture-based teaching and desire to control the content of teaching discussions, as well as technological advancement necessitating access to computers during case review.

In contrast, the patient-and family-centered movement began in the mid-20th century as a response to the separation trauma experienced by hospitalized children and their families [9]. Hospitals responded by liberalizing their visiting policies and encouraging direct care-giving by parents. FCC was further bolstered by consumer-led movements in the 1960s and 1970s, and by federal legislation in the 1980s targeting children with special health care needs. FCC gained national recognition in 2001 when the Institute of Medicine emphasized that involving patients and families in health care decisions increased the quality of their care [2]. Subsequently, the AAP endorsed FCC as a guiding approach to pediatric care in their 2003 report “Family-centered care and the pediatrician’s role” [1]. As part of this report, the AAP recommended that bedside presentations with active engagement of families become the standard of care. FCRs developed at several children’s hospitals in the US in the following years, with the first conceptual model of FCR published by Muething et al in 2007 [10].

Definition of Family-Centered Rounds

While no consensus definition of FCR exists, the most frequently cited description comes from Sisterhen et al who describe FCR as “interdisciplinary work rounds at the bedside in which the patient and family share in the control of the management plan as well as in the evaluation of the process itself” [11]. Three key features should be noted in this definition. First, FCR requires the active participation of family members, not merely their presence. In this way, patient and family voices are heard and their preferences solicited with respect to clinical decision-making. Second, FCR take place at the bedside, in alignment with the 2003 AAP policy statement that standard practice should be to conduct attending rounds with full case presentations in patient rooms in the presence of family. Third, FCR are typically interdisciplinary, involving patients and their families, physicians and trainees, nurses, and other ancillary staff (such as interpreters, case managers, and pharmacists) [1,10,11,12].

Since the IOM report, FCRs have gained substantial national momentum. A PRIS (Pediatric Research in Inpatient Setting) network study in 2010 published the first survey of pediatric hospitalist rounding practices in the US and Canada [12]. The study reported that 44% of pediatric hospitalists conducted FCRs, and about a quarter conducted rounds as hallway rounds or sit down rounds. Academic hospitalists were significantly more likely to conduct FCRs compared with non-academic (48% vs. 31%; P < 0.05) hospitalists. In accordance with Muething et al’s experience with FCRs in the Cincinnati model, the survey respondents did not associate FCR with prolonged rounding duration [10,12]. FCRs were also associated with greater bedside nurse participation [12]. Given the momentum behind FCC and the oft-cited benefits of FCR, it can only be presumed that the number of pediatric hospitals conducting FCR has significantly increased since the PRIS study was published in 2010.

FCRs Can Improve Quality of Care for Hospitalized Children

FCRs bring together multiple stakeholders involved in the patient’s care in the same place at the same time everyday. This allows for shared-decision making, identification of medical teams by families, and allows for direct and open communication between parents and medical teams [1,10–12]. The key stakeholders on a FCR team include the patient and family members and the medical team. The medical team includes attending physician, fellow, resident, and students, bedside nurse, care coordinator/case manager and other ancillary services. Although not enough data is available on who should attend rounds, case mangers and bedside nurse along with medical team and patients and families were found to be crucial in the general inpatient setting [12].

Integrating FCRs into the daily workflow in the inpatient setting provides several benefits for patients and families and the medical team, including trainees. Improvements in family-centered care principles, parental satisfaction, interdisciplinary team communication, efficiency, patient safety, and resident and medical student education have been reported consistently [9–23].

FCR Benefits for Patients and Families

Muething et al described increased patient-family satis-faction with higher levels of family participation in rounds and earlier discharge times [10]. On FCRs, families report having the opportunity to communicate directly with the entire care team, clarify misinformation and better understand care plans including discharge goals, leading to higher levels family satisfaction [10,14,24]. Both English and limited-English-proficient families report positive experiences with FCRs [21–23]. Families express appreciation with learning opportunities on FCRs, as well as the opportunity to serve as teachers to the medical team [14,16,21]. Families reported comfort with trainees being on rounds and appreciated seeing the medical personnel working as team [21]. They also report trust, comfort, and accountability towards the system and providers as they saw them working together as teams. They felt respected and involved as the medical teams involved them during rounds. Parents also report comfort with diversity of providers and feel that having multidisciplinary and diverse teams help with cultural competencies. Parents appreciated trainees being led by attending physician and felt that attending FCRs made them understand the medical process and the steps involved in caring for their child. They also reported that attending FCRs helps trainees learn about answering the kind of questions that parents usually ask. Contrary to the popular belief, parental participation has not increased the duration of FCRs and parental presence during rounds decreases time spent discussing each patient [14,25].

FCRs and Staff Satisfaction

Staff satisfaction with FCRs has been consistently high [13,14,18–23]. Nursing and medical staffs report valuing FCRs as they foster a sense of teamwork, improve understanding of the patient’s care plan and enhance communication between the care team and families [14]. FCRs significantly increase bedside nurse participation during rounds [12]. Presence of nursing and ancillary staff on FCRs improves efficiency by providing valuable information and helping address discharge goal [10]. Anecdotal data suggests that FCRs reduces number of pages trainees receive from nurses.

FCRs and Outcomes

FCRs have been perceived to improve in patient safety including errors in history taking and miscommunication, and incorrect information; and promote medication reconciliation, safety and adherence [17,20,21]. FCRs have shown to improve patient satisfaction, communication, and coordination of care and trainee education [10,14,21].

Educational Benefits of FCRs

families (Table 1) [26].

FCR Benefits for Hospitals and Health Care Systems

As health care prepares to fully adopt reforms and shift from volume-based to value-based payment systems, creating value in every patient encounter is vital. Conducting daily FCRs provide an dynamic venue for hospitals where daily rounds can incorporate evidence-based practice guidelines, prevent medication errors, ensure safety, reduce unnecessary tests and treatments, and improve transparency and accountability in care. This model can help hospital financially by meeting key quality and safety metrics and also help provide cost effective care through use and reinforcement of clinical pathways during rounds.

FCR Barriers

While many hospitals have adopted FCRs, many barriers to FCR implementation exist [10–14,18–23] (Table 1). Understanding these barriers and overcoming them are crucial for successful implementation. Conducting FCRs involve many aspects of care that happen during rounds. These include discussions about history, physical examinations, labs, and other tests; clinical decision-making and communication between parents and providers; team communication; teaching of trainees; discharge planning; and coordination of care [20]. Given all these aspects of care involved during rounds, being able to conduct multidisciplinary rounds in a timely and efficient way can be a challenge in a busy and dynamic inpatient setting.

Key identified FCR barriers have included physical constraints such as small patient rooms, large team size, patients being on multiple floors or units, infection control precautions leading to increased time involved with teams gowning and gloving; lack of training on FCRs for trainees and faculty; language and cultural barriers; family/patient concerns of privacy/disclosure of sensitive information; trainee’s fears of not appearing knowledgeable in front of families; and variability in attending physicians’ teaching style and approach to FCR [10–15,21].

Operationalizing Successful FCRs

Forming FCR Steering Committee: Developing Ground Rules

While there are many barriers to conducting efficient FCRs there are some that are unique to each institution. Therefore, for those institutions planning to initiate FCRs, the first step might be to form a FCR steering committee of key stakeholders who could review the current state, do a needs assessment for initiating FCRs, develop a structured and standardized FCR process and revise the FCR process periodically to meet the needs of the dynamic inpatient setting [10,12,14].

Defining and Identifying the FCR Process: Who, Where, and When of FCRs

The steering committee should clearly define FCRs and identify what FCRs would involve. For example, should FCRs involve complete case presentations and discussion in front of the parent or focused relevent H&P in a language that the parent understands? The steering committee should identify key elements/aspects of FCRs that would happen on daily rounds. For example: how should each patient receive information about FCRs? Should FCRs be offered to all patients? Do patients have options to opt-in or opt-out of FCRs on a daily basis or a one-time basis? Who should attend FCRs? For example, other than medical team, the bedside nurse and case manager should attend FCRs on a general pediatric service. Should the team round based on nursing assignments or resident assignments or in the order of room numbers? What should a typical rounding encounter involve? For example, each encounter should begin with the intern knocking on the door, asking parental permission for FCR team to enter the room, who should present, who should lead the rounds (the senior resident or the attending), who should stand where in the room? What should each encounter involve—for example, case presentation and discussion, parental involvement in decision-making, clarification of any parental questions, plan for that day, criteria for discharge and discharge needs assessment, teaching of resident and students, use of lay language etc. How should each rounding encounter end? Should the intern ask if parents have additional questions? It is important that the steering committee clearly identify these minute rounding details. Additionally, the committee should identify the rounding wards/area, the timing and duration of FCRs, how information about FCRs will be shared with patients and families, how trainees and attendees will be educated about FCRs and when are FCRs appropriate and when not. Defining the process early through stakeholder identification can reduce variability and create some standardization yet allow for individual style variations within the constraints of standardization. This will help reduced attending variability, which was cited as the most common FCR barrier by trainees.

As Seltz et al described, Latino families reported positive experiences with FCRs when a Spanish-speaking provider was involved. However, they report less satisfaction with telephone interpreters and did not feel empowered at times on FCRs due to language differences [23]. Addressing the language needs based on demographics and cultural needs will promote greater acceptance of FCRs [23].

Identifying and Defining Trainee Role

Participating in the FCR can create anxiety for medical students and residents. Therefore, educating them about the FCR process and structure beforehand and clearly defining roles can help them conceptualize their roles and expectation and ease their anxiety with FCRs. This will require the steering committee to collaboratively discuss how each encounter would look during FCR from a trainee’s perspective. Who will present the case? The third- year medical student versus the fourth-year medical student or the intern or based on case allocations? How should the case be presented? Should it be short and pointed presentation versus complete history and physical examination on each patient? How long should an encounter last on a new patient and on a follow-up patient? Who will examine the patient? The student who is presenting the case, the attending, the intern who overlooks the student, or the senior resident? Who will answer the follow-up questions from a parent initially? Should the senior resident lead the team under the attending guidance? How will the senior resident be prepared for morning rounds? Using lay language when talking to parents should be encouraged and taught to trainees routinely during FCRs.

Identifying and Defining Clinical Teaching Styles

Faculty Development Program and Importance of “Safe Environment”

Developing an educational program to train faculty, trainee and staff about FCRs can help streamline FCRs. Conducting FCRs is a cultural change and focusing on early adopters is crucial. Muething et al’s model showed better acceptance of FCRs by interns than by senior residents. Being patient during change management is key to successful implementation. Anecdotal discussions during PAS workshops suggests that on an average programs have required 3 years to get significant buy-in and streamlining of FCRs [10,12].

Suboptimal attending behavior such as attending variability in the FCRs process and teaching strategies have been reported as FCR barriers [14,21]. Residents report attending physician as an important factor determining success of FCRs. As attending physicians typically are the leaders of the FCRs team, training faculty about conducting effective and efficient FCRs is crucial to successful FCRs. [12,21]. Key aspects of faculty development should include: (1) education about the FCR standard process for the institution, (2) importance of time management during rounds, including tips and strategies to be efficient, (3) teaching styles during FCRs, including demonstrating role modeling, and (4) direct observation of trainees and individual and team feedback to streamline FCRs. Role-plays or simulated FCRs might be a venue to explore for faculty development on FCRs [14,21].

Creating a “safe environment” during FCRs where each person feels comfortable and secure is vital to team work [7,12,21]. Often trainees are apprehensive or afraid due to medical hierarchy and this might prevent developing a teaching and learning environment. Trainees fear not appearing knowledgeable in front of families and student rotate too often to adapt to different attending styles [21]. Therefore, reassuring trainees that the goal of FCRs is to conduct daily inpatient rounding to ensure key aspects of FCRs are met without disrespecting and insulting any person on rounds and clarifying and reassuring trainees that their fear of not appearing knowledgeable is real and it will be respected, might help create a safe environment where FCR teams are not only conducting the daily ritual of inpatient rounding, and teaching but also ensuring that trainees are enjoying being the clinician and physicians that they want to be. Therefore, attending role modeling is crucial and it is no surprise that in multiple studies variability in attending rounding and teaching style was identified consistently as a FCR barrier.

Preparing for Daily FCRS: Team Work, Efficiency, and Time Management