User login

Atypical Keratotic Nodule on the Knuckle

The Diagnosis: Atypical Mycobacterial Infection

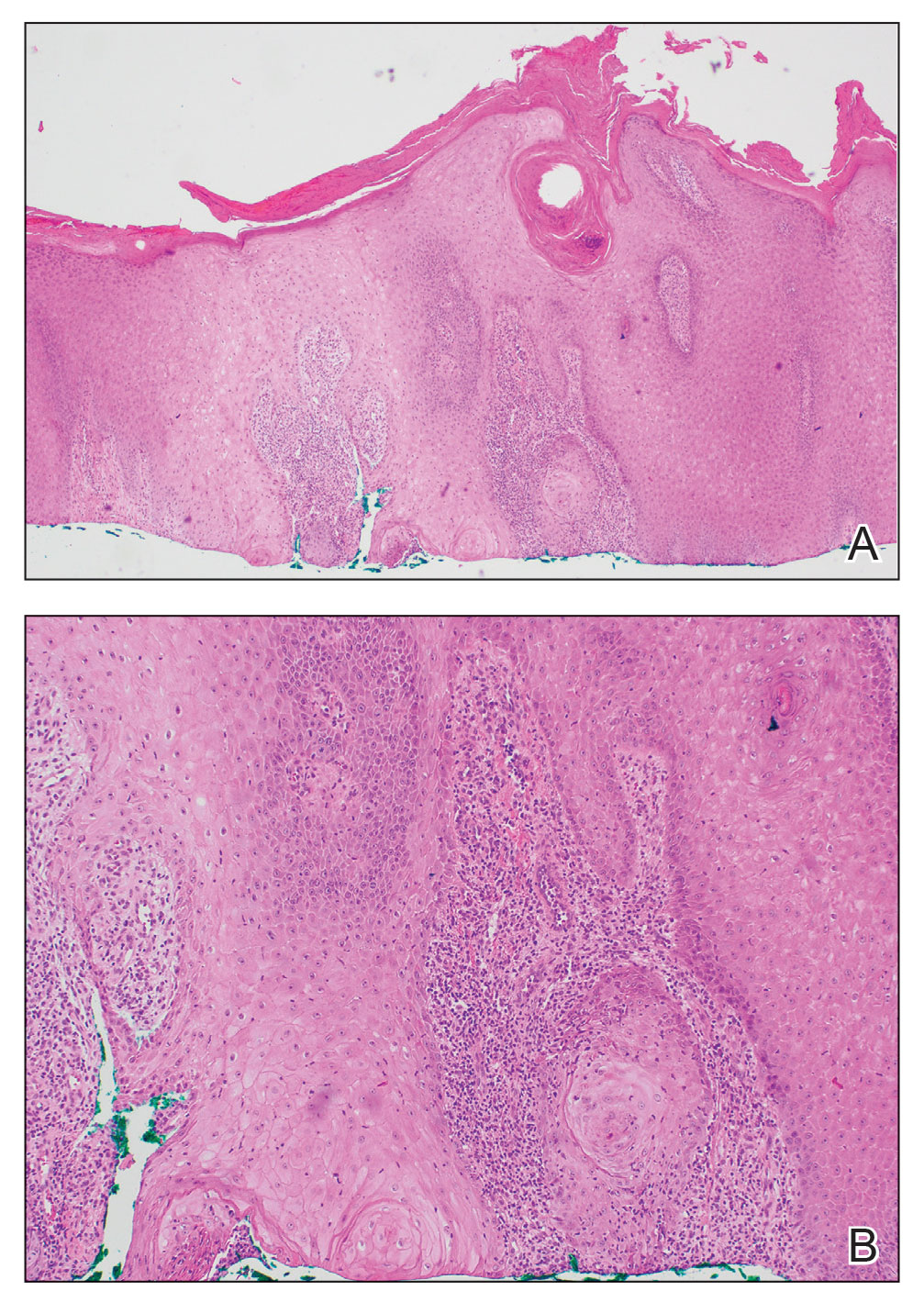

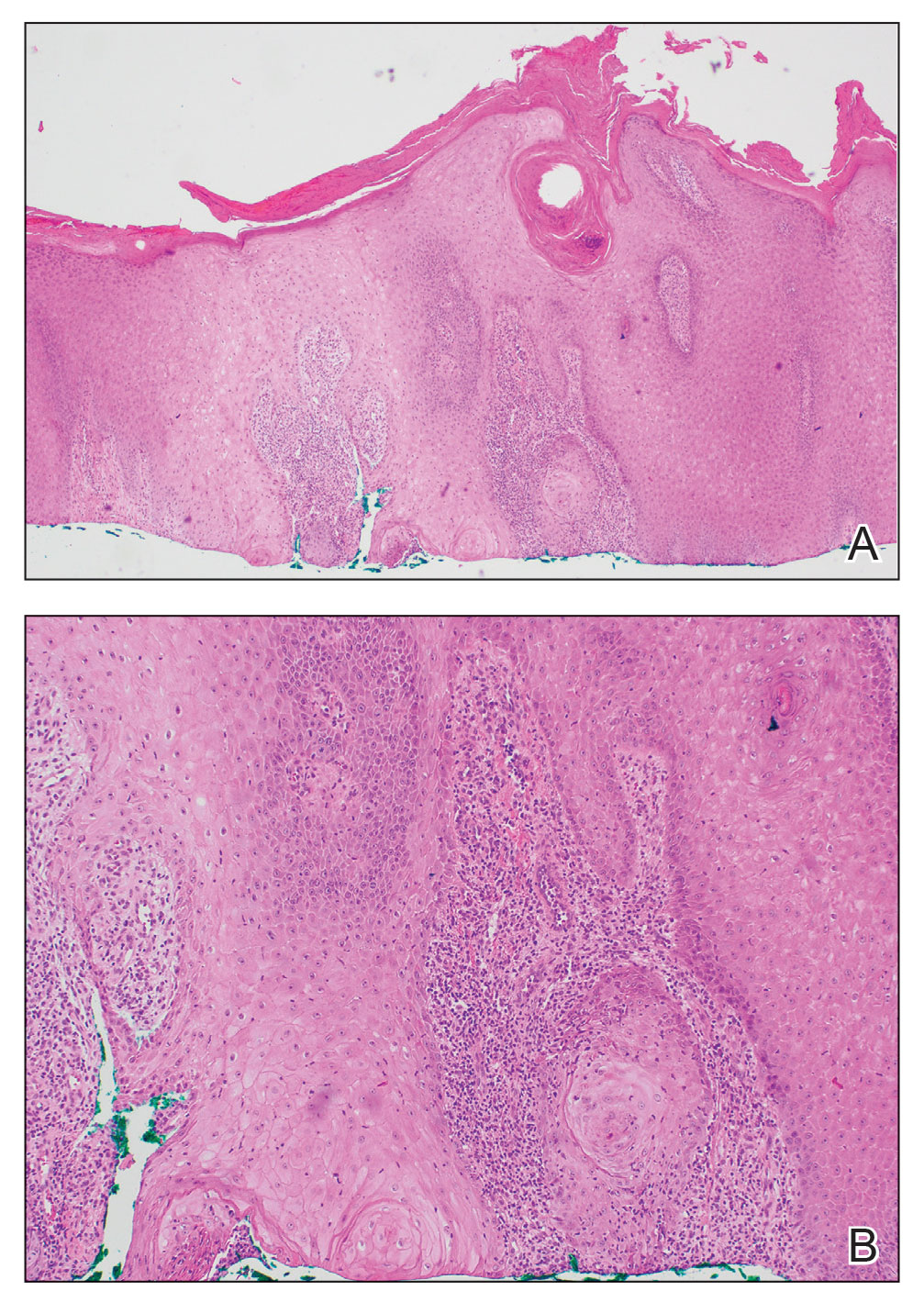

The history of rapid growth followed by shrinkage as well as the craterlike clinical appearance of our patient’s lesion were suspicious for the keratoacanthoma variant of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). Periodic acid–Schiff green staining was negative for fungal or bacterial organisms, and the biopsy findings of keratinocyte atypia and irregular epidermal proliferation seemed to confirm our suspicion for well-differentiated SCC (Figure 1). Our patient subsequently was scheduled for Mohs micrographic surgery. Fortunately, a sample of tissue had been sent for panculture—bacterial, fungal, and mycobacterial—to rule out infectious etiologies, given the history of possible traumatic inoculation, and returned positive for Mycobacterium marinum infection prior to the surgery. Mohs surgery was canceled, and he was referred to an infectious disease specialist who started antibiotic treatment with azithromycin, ethambutol, and rifabutin. After 1 month of treatment the lesion substantially improved (Figure 2), further supporting the diagnosis of M marinum infection over SCC.

The differential diagnosis also included sporotrichosis, leishmaniasis, and chromoblastomycosis. Sporotrichosis lesions typically develop as multiple nodules and ulcers along a path of lymphatic drainage and can exhibit asteroid bodies and cigar-shaped yeast forms on histology. Chromoblastomycosis may display pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia and granulomatous inflammation; however, pathognomonic pigmented Medlar bodies also likely would be present.1 Leishmaniasis has a wide variety of presentations; however, it typically occurs in patients with exposure to endemic areas outside of the United States. Although leishmaniasis may demonstrate pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, ulceration, and mixed inflammation on histology, it also likely would show amastigotes within dermal macrophages.2

Atypical mycobacterial infections initially may be misdiagnosed as SCC due to their tendency to induce irregular acanthosis in the form of pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia as well as mild keratinocyte atypia secondary to inflammation.3,4 Our case is unique because it occurred with M marinum infection specifically. The histopathologic findings of M marinum infections are variable and may additionally include granulomas, most commonly suppurative; intraepithelial abscesses; small vessel proliferation; dermal fibrosis; multinucleated giant cells; and transepidermal elimination.4,5 Periodic acid–Schiff, Ziehl-Neelsen (acid-fast bacilli), and Fite staining may be used to distinguish M marinum infection from SCC but have low sensitivities (approximately 30%). Culture remains the most reliable test, with a sensitivity of nearly 80%.5-7 In our patient, a Periodic acid–Schiff stain was obtained prior to receiving culture results, and acid-fast bacilli and Fite staining were added after the culture returned positive; however, all 3 stains failed to highlight any mycobacteria.

The primary risk factor for infection with M marinum is contact with aquatic environments or marine animals, and most cases involve the fingers or the hand.6 After we reached the diagnosis and further discussed the patient’s history, he recalled fishing for and cleaning raw shrimp around the time that he had a splinter. The Infectious Diseases Society of America recommends a treatment course extending 1 to 2 months after clinical symptoms resolve with ethambutol in addition to clarithromycin or azithromycin.8 If the infection is near a joint, rifampin should be empirically added to account for a potentially deeper infection. Imaging should be obtained to evaluate for joint space involvement, with magnetic resonance imaging being the preferred modality. If joint space involvement is confirmed, surgical debridement is indicated. Surgical debridement also is indicated for infections that fail to respond to antibiotic therapy.8

This case highlights M marinum infection as a potential mimicker of SCC, particularly if the biopsy is relatively superficial, as often occurs when obtained via the common shave technique. The distinction is critical, as M marinum infection is highly treatable and inappropriate surgery on the typical hand and finger locations may subject patients to substantial morbidity, such as the need for a skin graft, reduced mobility from scarring, or risk for serious wound infection.9 For superficial biopsies of an atypical squamous process, pathologists also may consider routinely recommending tissue culture, especially for hand and finger locations or when a history of local trauma is reported, instead of recommending complete excision or repeat biopsy alone.

- Elewski BE, Hughey LC, Hunt KM, et al. Fungal diseases. In: Bolognia J, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2018:1329-1363.

- Bravo FG. Protozoa and worms. In: Bolognia J, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2018:1470-1502.

- Zayour M, Lazova R. Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia: a review. Am J Dermatopathol. 2011;33:112-122; quiz 123-126. doi:10.1097 /DAD.0b013e3181fcfb47

- Li JJ, Beresford R, Fyfe J, et al. Clinical and histopathological features of cutaneous nontuberculous mycobacterial infection: a review of 13 cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:433-443. doi:10.1111/cup.12903

- Abbas O, Marrouch N, Kattar MM, et al. Cutaneous non-tuberculous mycobacterial infections: a clinical and histopathological study of 17 cases from Lebanon. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:33-42. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2010.03684.x

- Johnson MG, Stout JE. Twenty-eight cases of Mycobacterium marinum infection: retrospective case series and literature review. Infection. 2015;43:655-662. doi:10.1007/s15010-015-0776-8

- Aubry A, Mougari F, Reibel F, et al. Mycobacterium marinum. Microbiol Spectr. 2017;5. doi:10.1128/microbiolspec.TNMI7-0038-2016

- Griffith DE, Aksamit T, Brown-Elliott BA, et al. An official ATS/IDSA statement: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of nontuberculous mycobacterial diseases. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:367-416. doi:10.1164/rccm.200604-571ST

- Alam M, Ibrahim O, Nodzenski M, et al. Adverse events associated with Mohs micrographic surgery: multicenter prospective cohort study of 20,821 cases at 23 centers. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:1378-1385. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.6255

The Diagnosis: Atypical Mycobacterial Infection

The history of rapid growth followed by shrinkage as well as the craterlike clinical appearance of our patient’s lesion were suspicious for the keratoacanthoma variant of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). Periodic acid–Schiff green staining was negative for fungal or bacterial organisms, and the biopsy findings of keratinocyte atypia and irregular epidermal proliferation seemed to confirm our suspicion for well-differentiated SCC (Figure 1). Our patient subsequently was scheduled for Mohs micrographic surgery. Fortunately, a sample of tissue had been sent for panculture—bacterial, fungal, and mycobacterial—to rule out infectious etiologies, given the history of possible traumatic inoculation, and returned positive for Mycobacterium marinum infection prior to the surgery. Mohs surgery was canceled, and he was referred to an infectious disease specialist who started antibiotic treatment with azithromycin, ethambutol, and rifabutin. After 1 month of treatment the lesion substantially improved (Figure 2), further supporting the diagnosis of M marinum infection over SCC.

The differential diagnosis also included sporotrichosis, leishmaniasis, and chromoblastomycosis. Sporotrichosis lesions typically develop as multiple nodules and ulcers along a path of lymphatic drainage and can exhibit asteroid bodies and cigar-shaped yeast forms on histology. Chromoblastomycosis may display pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia and granulomatous inflammation; however, pathognomonic pigmented Medlar bodies also likely would be present.1 Leishmaniasis has a wide variety of presentations; however, it typically occurs in patients with exposure to endemic areas outside of the United States. Although leishmaniasis may demonstrate pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, ulceration, and mixed inflammation on histology, it also likely would show amastigotes within dermal macrophages.2

Atypical mycobacterial infections initially may be misdiagnosed as SCC due to their tendency to induce irregular acanthosis in the form of pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia as well as mild keratinocyte atypia secondary to inflammation.3,4 Our case is unique because it occurred with M marinum infection specifically. The histopathologic findings of M marinum infections are variable and may additionally include granulomas, most commonly suppurative; intraepithelial abscesses; small vessel proliferation; dermal fibrosis; multinucleated giant cells; and transepidermal elimination.4,5 Periodic acid–Schiff, Ziehl-Neelsen (acid-fast bacilli), and Fite staining may be used to distinguish M marinum infection from SCC but have low sensitivities (approximately 30%). Culture remains the most reliable test, with a sensitivity of nearly 80%.5-7 In our patient, a Periodic acid–Schiff stain was obtained prior to receiving culture results, and acid-fast bacilli and Fite staining were added after the culture returned positive; however, all 3 stains failed to highlight any mycobacteria.

The primary risk factor for infection with M marinum is contact with aquatic environments or marine animals, and most cases involve the fingers or the hand.6 After we reached the diagnosis and further discussed the patient’s history, he recalled fishing for and cleaning raw shrimp around the time that he had a splinter. The Infectious Diseases Society of America recommends a treatment course extending 1 to 2 months after clinical symptoms resolve with ethambutol in addition to clarithromycin or azithromycin.8 If the infection is near a joint, rifampin should be empirically added to account for a potentially deeper infection. Imaging should be obtained to evaluate for joint space involvement, with magnetic resonance imaging being the preferred modality. If joint space involvement is confirmed, surgical debridement is indicated. Surgical debridement also is indicated for infections that fail to respond to antibiotic therapy.8

This case highlights M marinum infection as a potential mimicker of SCC, particularly if the biopsy is relatively superficial, as often occurs when obtained via the common shave technique. The distinction is critical, as M marinum infection is highly treatable and inappropriate surgery on the typical hand and finger locations may subject patients to substantial morbidity, such as the need for a skin graft, reduced mobility from scarring, or risk for serious wound infection.9 For superficial biopsies of an atypical squamous process, pathologists also may consider routinely recommending tissue culture, especially for hand and finger locations or when a history of local trauma is reported, instead of recommending complete excision or repeat biopsy alone.

The Diagnosis: Atypical Mycobacterial Infection

The history of rapid growth followed by shrinkage as well as the craterlike clinical appearance of our patient’s lesion were suspicious for the keratoacanthoma variant of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). Periodic acid–Schiff green staining was negative for fungal or bacterial organisms, and the biopsy findings of keratinocyte atypia and irregular epidermal proliferation seemed to confirm our suspicion for well-differentiated SCC (Figure 1). Our patient subsequently was scheduled for Mohs micrographic surgery. Fortunately, a sample of tissue had been sent for panculture—bacterial, fungal, and mycobacterial—to rule out infectious etiologies, given the history of possible traumatic inoculation, and returned positive for Mycobacterium marinum infection prior to the surgery. Mohs surgery was canceled, and he was referred to an infectious disease specialist who started antibiotic treatment with azithromycin, ethambutol, and rifabutin. After 1 month of treatment the lesion substantially improved (Figure 2), further supporting the diagnosis of M marinum infection over SCC.

The differential diagnosis also included sporotrichosis, leishmaniasis, and chromoblastomycosis. Sporotrichosis lesions typically develop as multiple nodules and ulcers along a path of lymphatic drainage and can exhibit asteroid bodies and cigar-shaped yeast forms on histology. Chromoblastomycosis may display pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia and granulomatous inflammation; however, pathognomonic pigmented Medlar bodies also likely would be present.1 Leishmaniasis has a wide variety of presentations; however, it typically occurs in patients with exposure to endemic areas outside of the United States. Although leishmaniasis may demonstrate pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, ulceration, and mixed inflammation on histology, it also likely would show amastigotes within dermal macrophages.2

Atypical mycobacterial infections initially may be misdiagnosed as SCC due to their tendency to induce irregular acanthosis in the form of pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia as well as mild keratinocyte atypia secondary to inflammation.3,4 Our case is unique because it occurred with M marinum infection specifically. The histopathologic findings of M marinum infections are variable and may additionally include granulomas, most commonly suppurative; intraepithelial abscesses; small vessel proliferation; dermal fibrosis; multinucleated giant cells; and transepidermal elimination.4,5 Periodic acid–Schiff, Ziehl-Neelsen (acid-fast bacilli), and Fite staining may be used to distinguish M marinum infection from SCC but have low sensitivities (approximately 30%). Culture remains the most reliable test, with a sensitivity of nearly 80%.5-7 In our patient, a Periodic acid–Schiff stain was obtained prior to receiving culture results, and acid-fast bacilli and Fite staining were added after the culture returned positive; however, all 3 stains failed to highlight any mycobacteria.

The primary risk factor for infection with M marinum is contact with aquatic environments or marine animals, and most cases involve the fingers or the hand.6 After we reached the diagnosis and further discussed the patient’s history, he recalled fishing for and cleaning raw shrimp around the time that he had a splinter. The Infectious Diseases Society of America recommends a treatment course extending 1 to 2 months after clinical symptoms resolve with ethambutol in addition to clarithromycin or azithromycin.8 If the infection is near a joint, rifampin should be empirically added to account for a potentially deeper infection. Imaging should be obtained to evaluate for joint space involvement, with magnetic resonance imaging being the preferred modality. If joint space involvement is confirmed, surgical debridement is indicated. Surgical debridement also is indicated for infections that fail to respond to antibiotic therapy.8

This case highlights M marinum infection as a potential mimicker of SCC, particularly if the biopsy is relatively superficial, as often occurs when obtained via the common shave technique. The distinction is critical, as M marinum infection is highly treatable and inappropriate surgery on the typical hand and finger locations may subject patients to substantial morbidity, such as the need for a skin graft, reduced mobility from scarring, or risk for serious wound infection.9 For superficial biopsies of an atypical squamous process, pathologists also may consider routinely recommending tissue culture, especially for hand and finger locations or when a history of local trauma is reported, instead of recommending complete excision or repeat biopsy alone.

- Elewski BE, Hughey LC, Hunt KM, et al. Fungal diseases. In: Bolognia J, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2018:1329-1363.

- Bravo FG. Protozoa and worms. In: Bolognia J, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2018:1470-1502.

- Zayour M, Lazova R. Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia: a review. Am J Dermatopathol. 2011;33:112-122; quiz 123-126. doi:10.1097 /DAD.0b013e3181fcfb47

- Li JJ, Beresford R, Fyfe J, et al. Clinical and histopathological features of cutaneous nontuberculous mycobacterial infection: a review of 13 cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:433-443. doi:10.1111/cup.12903

- Abbas O, Marrouch N, Kattar MM, et al. Cutaneous non-tuberculous mycobacterial infections: a clinical and histopathological study of 17 cases from Lebanon. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:33-42. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2010.03684.x

- Johnson MG, Stout JE. Twenty-eight cases of Mycobacterium marinum infection: retrospective case series and literature review. Infection. 2015;43:655-662. doi:10.1007/s15010-015-0776-8

- Aubry A, Mougari F, Reibel F, et al. Mycobacterium marinum. Microbiol Spectr. 2017;5. doi:10.1128/microbiolspec.TNMI7-0038-2016

- Griffith DE, Aksamit T, Brown-Elliott BA, et al. An official ATS/IDSA statement: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of nontuberculous mycobacterial diseases. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:367-416. doi:10.1164/rccm.200604-571ST

- Alam M, Ibrahim O, Nodzenski M, et al. Adverse events associated with Mohs micrographic surgery: multicenter prospective cohort study of 20,821 cases at 23 centers. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:1378-1385. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.6255

- Elewski BE, Hughey LC, Hunt KM, et al. Fungal diseases. In: Bolognia J, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2018:1329-1363.

- Bravo FG. Protozoa and worms. In: Bolognia J, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2018:1470-1502.

- Zayour M, Lazova R. Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia: a review. Am J Dermatopathol. 2011;33:112-122; quiz 123-126. doi:10.1097 /DAD.0b013e3181fcfb47

- Li JJ, Beresford R, Fyfe J, et al. Clinical and histopathological features of cutaneous nontuberculous mycobacterial infection: a review of 13 cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:433-443. doi:10.1111/cup.12903

- Abbas O, Marrouch N, Kattar MM, et al. Cutaneous non-tuberculous mycobacterial infections: a clinical and histopathological study of 17 cases from Lebanon. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:33-42. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2010.03684.x

- Johnson MG, Stout JE. Twenty-eight cases of Mycobacterium marinum infection: retrospective case series and literature review. Infection. 2015;43:655-662. doi:10.1007/s15010-015-0776-8

- Aubry A, Mougari F, Reibel F, et al. Mycobacterium marinum. Microbiol Spectr. 2017;5. doi:10.1128/microbiolspec.TNMI7-0038-2016

- Griffith DE, Aksamit T, Brown-Elliott BA, et al. An official ATS/IDSA statement: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of nontuberculous mycobacterial diseases. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:367-416. doi:10.1164/rccm.200604-571ST

- Alam M, Ibrahim O, Nodzenski M, et al. Adverse events associated with Mohs micrographic surgery: multicenter prospective cohort study of 20,821 cases at 23 centers. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:1378-1385. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.6255

A 75-year-old man presented with a lesion on the knuckle of 5 months’ duration. He reported that the lesion initially grew very quickly before shrinking down to its current size. He denied any bleeding or pain but thought he may have had a splinter in the area around the time the lesion appeared. He reported spending a lot of time outdoors and noted several recent insect and tick bites. He also owned a boat and frequently went fishing. He previously had been treated for actinic keratoses but had no history of skin cancer and no family history of melanoma. Physical examination revealed a 2-cm erythematous nodule with central hyperkeratosis overlying the metacarpophalangeal joint of the right index finger. A shave biopsy was performed.

Vegetative Plaques on the Face

THE DIAGNOSIS: Vegetative Majocchi Granuloma

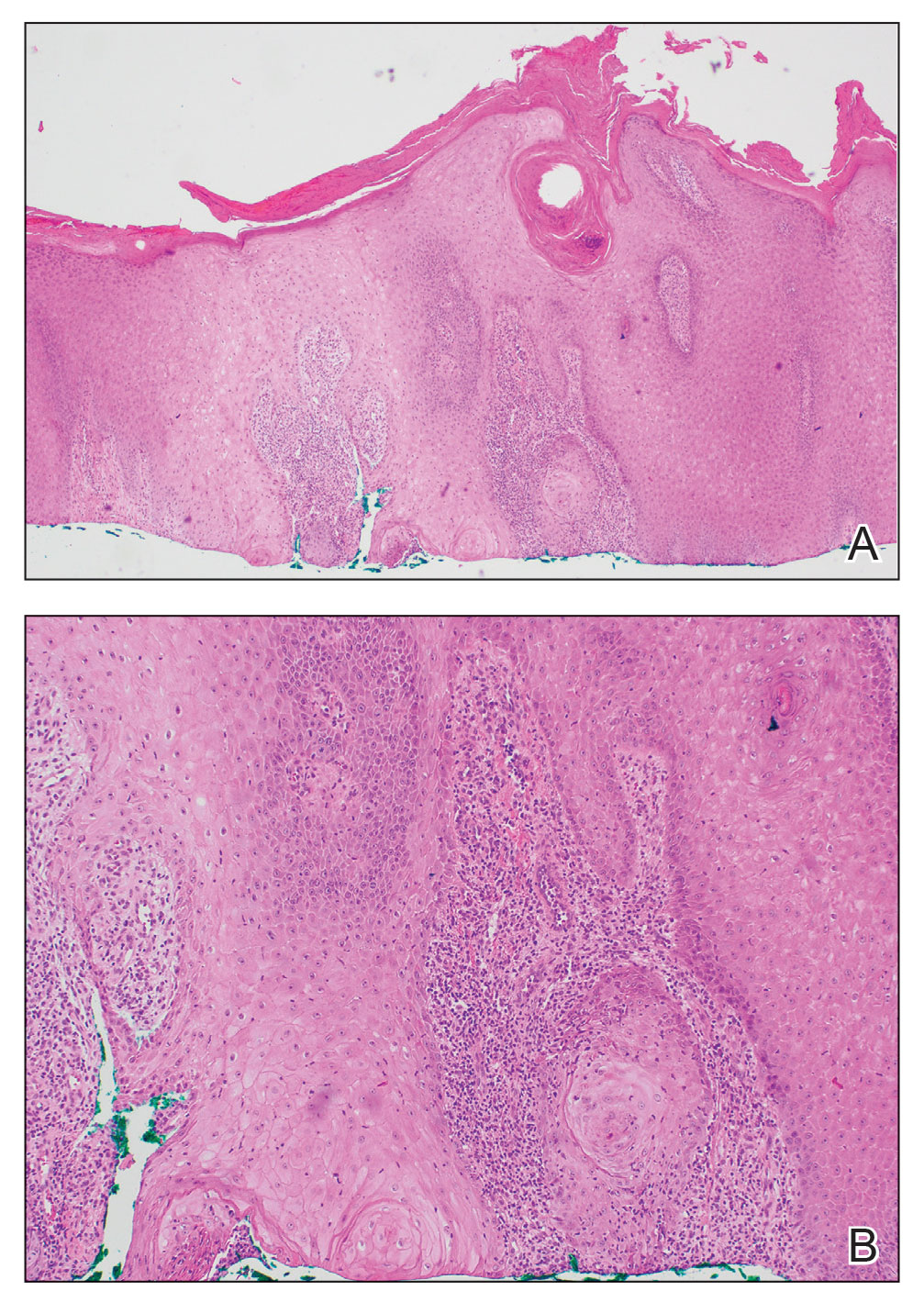

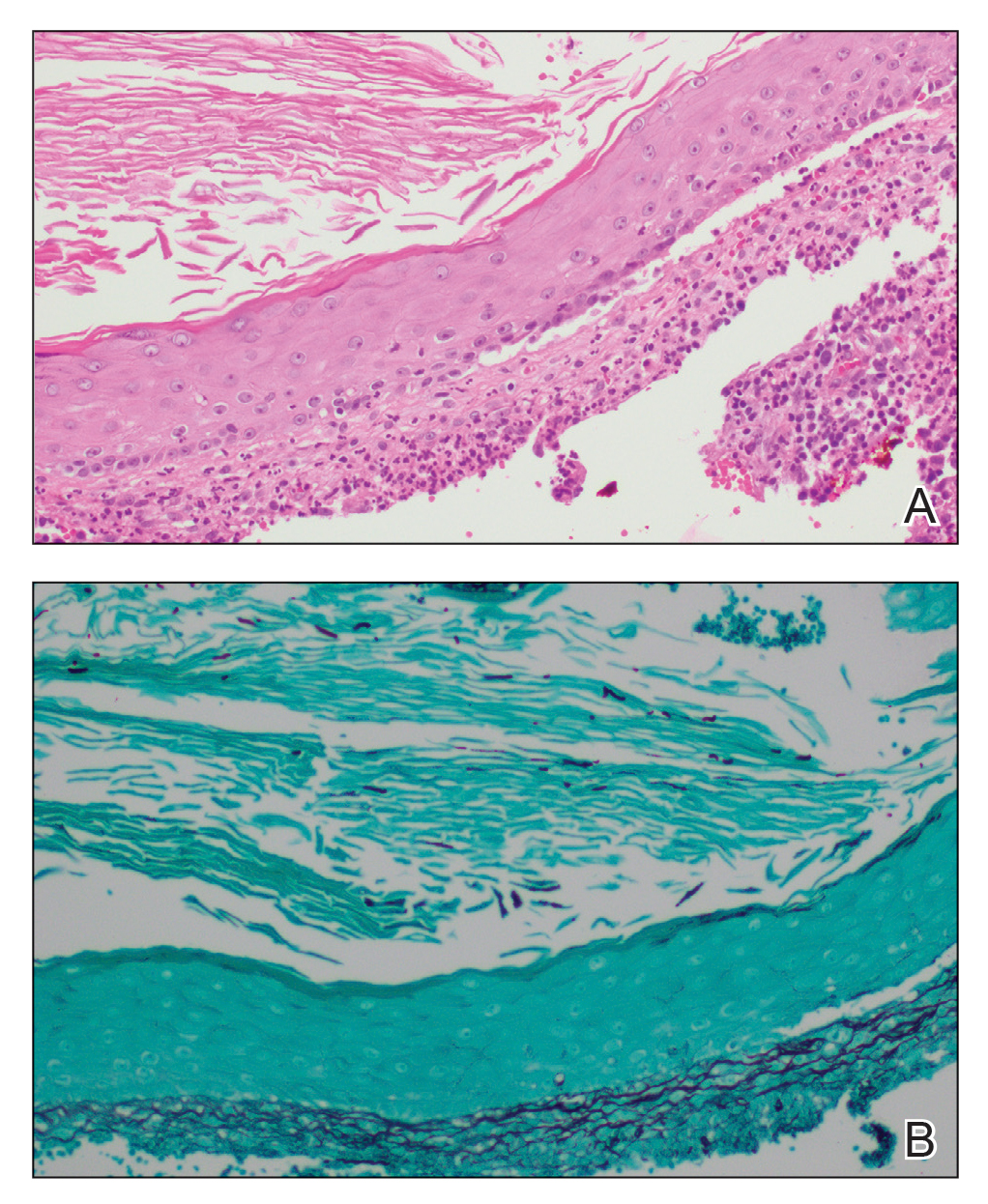

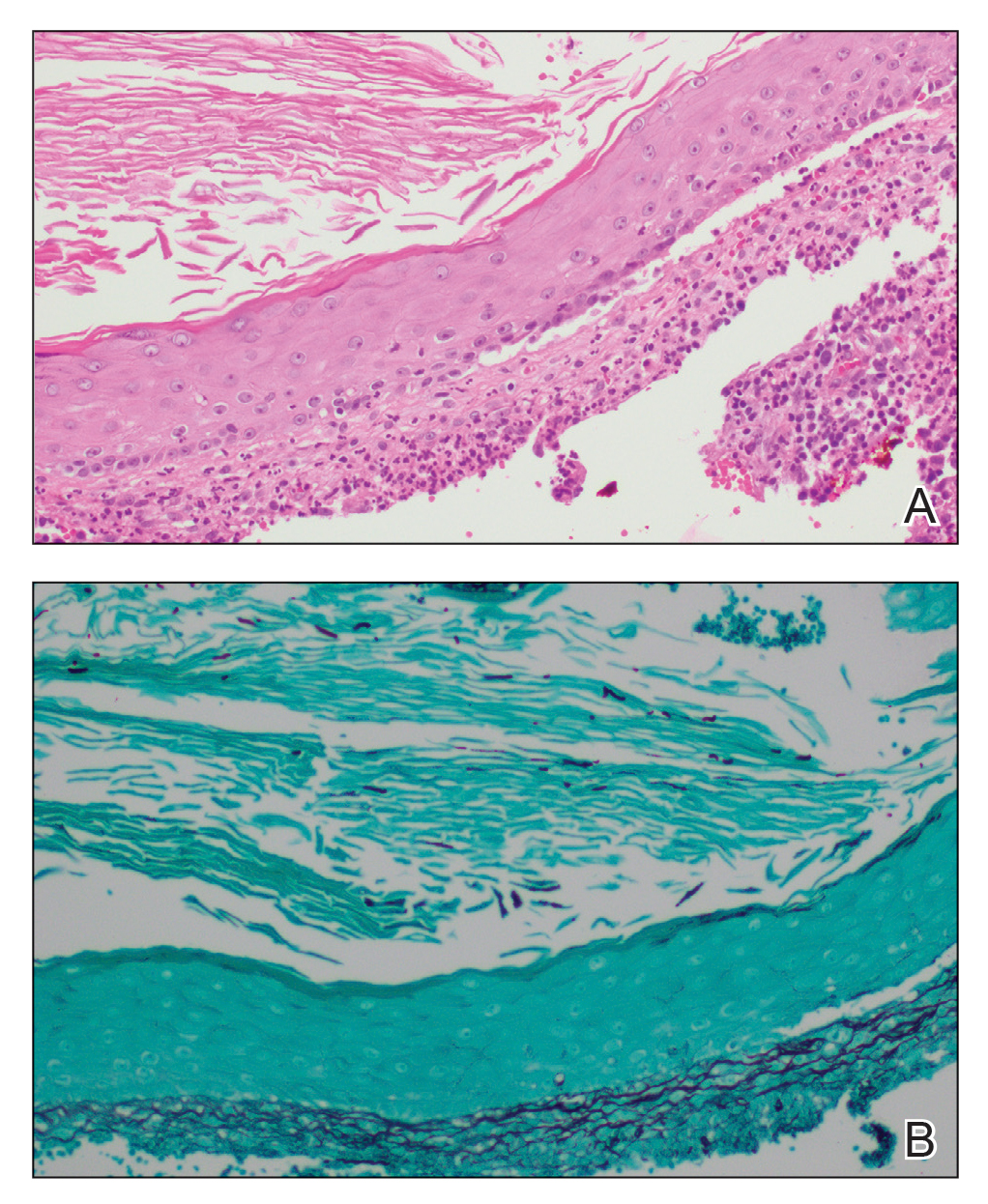

A biopsy and tissue culture showed acute dermal inflammation with granulomatous features and numerous fungal hyphae within the stratum corneum (Figure 1A), which were confirmed on GrocottGomori methenamine-silver staining (Figure 1B). Gram and Fite stains were negative for bacteria. A tissue culture speciated Trichophyton rubrum, which led to a diagnosis of deep dermatophyte infection (Majocchi granuloma) with a highly unusual clinical presentation of vegetative plaques. Predisposing factors included treatment with topical corticosteroids and possibly poor health and nutritional status at baseline. Our patient was treated with fluconazole 200 mg daily for 6 weeks, with near resolution of lesions at 3-week follow-up (Figure 2).

Dermatophytes are a common cause of superficial skin infections. The classic morphology consists of an annular scaly plaque; however, a wide variety of presentations have been observed (eg, verrucous, vesicular, pustular, granulomatous). Therefore, dermatophyte infections often mimic other dermatologic conditions, including atopic dermatitis, rosacea, psoriasis, bacterial abscess, erythema gyratum repens, lupus, granuloma annulare, cutaneous lymphoma, Hailey-Hailey disease, scarring alopecia, and syphilis.1

Notably, when dermatophytes grow downward along hair follicles causing deeper infection, disruption of the follicular wall can lead to an excessive inflammatory response with granulomatous features.2 Risk factors include cutaneous trauma, long-standing infection, immunocompromise, and treatment with topical corticosteroids.3 This disease evolution clinically appears as a nodule or infiltrated plaque, often without scale. The most well-known example is a kerion on the scalp. Elsewhere on the body, lesions often are termed Majocchi granulomas.2

Vegetative plaques, as seen in our patient, are a highly unusual morphology for deep tinea infection. Guanziroli et al4 reported a case of vegetative lesions on the forearm of a 67-year-old immunocompromised man that were successfully treated with a 3-month course of oral terbinafine after Trichophyton verrucosum was isolated. Skorepova et al5 reported a case of pyoderma vegetans triggered by recurrent Trichophyton mentagrophytes on the dorsal hands of a 64-year-old man with immunoglobulin deficiency of unknown etiology. The lesions were successfully treated with a prolonged course of doxycycline, topical triamcinolone, and intravenous immunoglobulin following 2 initial courses of terbinafine.

The differential diagnosis for vegetative lesions includes pemphigus vegetans, a vegetative variant of pyoderma gangrenosum; halogenoderma; and a variety of infections, including dimorphic fungi (histoplasmosis, blastomycosis), blastomycosislike pyoderma (bacterial), and candidiasis.6 These conditions usually can be distinguished based on histopathology. Clinically, pemphigus vegetans presents with pustules and vegetative lesions, as in our patient, but usually is more diffuse and favors the intertriginous areas. Histology likely would reveal foci of acantholysis and eosinophils. Vegetative pyoderma gangrenosum favors the trunk, particularly in sites of surgical trauma. In our patient, no lesions were present near the abdominal surgical sites, and there was no antecedent cribriform ulceration. Halogenoderma was a strong initial consideration given the localization, presence of large pustules, and history of numerous contrast computed tomography studies; however, our patient’s iodine levels were normal. Infectious etiologies including dimorphic fungi and blastomycosislike pyoderma generally are not restricted to the head and neck, and tissue culture helps exclude them. Vegetative lesions may occur in the setting of other infections, and tissue culture may be necessary to differentiate them if histopathology is not suggestive.

Deep dermatophyte infections require treatment with oral antifungals, as topicals do not penetrate adequately into the hair follicles. Exact regimens vary, but generally oral terbinafine or an oral azole (except ketoconazole) is administered for 2 to 6 weeks, with immunocompromise necessitating longer courses.

We present a rare case of vegetative Majocchi granuloma secondary to T rubrum infection. A dermatophyte infection should be included in the differential for vegetative lesions, especially in dense hair-bearing areas such as the beard. Treatment generally is straightforward with oral antifungals.

- Atzori L, Pau M, Aste N, et al. Dermatophyte infections mimicking other skin diseases: a 154-person case survey of tinea atypica in the district of Cagliari (Italy). Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:410-415.

- Ilkit M, Durdu M, Karakas M. Majocchi’s granuloma: a symptom complex caused by fungal pathogens. Med Mycol. 2012;50:449-457.

- Jevremovic L, Ilijin I, Kostic K, et al. Pyoderma vegetans—a case report. Serbian J Dermatol Venereol. 2017;9:22-28.

- Guanziroli E, Pavia G, Guttadauro A, et al. Deep dermatophytosis caused by Trichophyton verrucosum in an immunosuppressed patient: successful outcome with terbinafine. Mycopathologia. 2019;184:543-545.

- Skorepová M, Stuchlík D. Chronic pyoderma vegetans triggered by Trichophyton mentagrophytes. Mycoses. 2006;49:143-144.

- Reinholz M, Hermans C, Dietrich A, et al. A case of cutaneous vegetating candidiasis in a patient with keratitis-ichthyosis-deafness syndrome. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:537-539.

THE DIAGNOSIS: Vegetative Majocchi Granuloma

A biopsy and tissue culture showed acute dermal inflammation with granulomatous features and numerous fungal hyphae within the stratum corneum (Figure 1A), which were confirmed on GrocottGomori methenamine-silver staining (Figure 1B). Gram and Fite stains were negative for bacteria. A tissue culture speciated Trichophyton rubrum, which led to a diagnosis of deep dermatophyte infection (Majocchi granuloma) with a highly unusual clinical presentation of vegetative plaques. Predisposing factors included treatment with topical corticosteroids and possibly poor health and nutritional status at baseline. Our patient was treated with fluconazole 200 mg daily for 6 weeks, with near resolution of lesions at 3-week follow-up (Figure 2).

Dermatophytes are a common cause of superficial skin infections. The classic morphology consists of an annular scaly plaque; however, a wide variety of presentations have been observed (eg, verrucous, vesicular, pustular, granulomatous). Therefore, dermatophyte infections often mimic other dermatologic conditions, including atopic dermatitis, rosacea, psoriasis, bacterial abscess, erythema gyratum repens, lupus, granuloma annulare, cutaneous lymphoma, Hailey-Hailey disease, scarring alopecia, and syphilis.1

Notably, when dermatophytes grow downward along hair follicles causing deeper infection, disruption of the follicular wall can lead to an excessive inflammatory response with granulomatous features.2 Risk factors include cutaneous trauma, long-standing infection, immunocompromise, and treatment with topical corticosteroids.3 This disease evolution clinically appears as a nodule or infiltrated plaque, often without scale. The most well-known example is a kerion on the scalp. Elsewhere on the body, lesions often are termed Majocchi granulomas.2

Vegetative plaques, as seen in our patient, are a highly unusual morphology for deep tinea infection. Guanziroli et al4 reported a case of vegetative lesions on the forearm of a 67-year-old immunocompromised man that were successfully treated with a 3-month course of oral terbinafine after Trichophyton verrucosum was isolated. Skorepova et al5 reported a case of pyoderma vegetans triggered by recurrent Trichophyton mentagrophytes on the dorsal hands of a 64-year-old man with immunoglobulin deficiency of unknown etiology. The lesions were successfully treated with a prolonged course of doxycycline, topical triamcinolone, and intravenous immunoglobulin following 2 initial courses of terbinafine.

The differential diagnosis for vegetative lesions includes pemphigus vegetans, a vegetative variant of pyoderma gangrenosum; halogenoderma; and a variety of infections, including dimorphic fungi (histoplasmosis, blastomycosis), blastomycosislike pyoderma (bacterial), and candidiasis.6 These conditions usually can be distinguished based on histopathology. Clinically, pemphigus vegetans presents with pustules and vegetative lesions, as in our patient, but usually is more diffuse and favors the intertriginous areas. Histology likely would reveal foci of acantholysis and eosinophils. Vegetative pyoderma gangrenosum favors the trunk, particularly in sites of surgical trauma. In our patient, no lesions were present near the abdominal surgical sites, and there was no antecedent cribriform ulceration. Halogenoderma was a strong initial consideration given the localization, presence of large pustules, and history of numerous contrast computed tomography studies; however, our patient’s iodine levels were normal. Infectious etiologies including dimorphic fungi and blastomycosislike pyoderma generally are not restricted to the head and neck, and tissue culture helps exclude them. Vegetative lesions may occur in the setting of other infections, and tissue culture may be necessary to differentiate them if histopathology is not suggestive.

Deep dermatophyte infections require treatment with oral antifungals, as topicals do not penetrate adequately into the hair follicles. Exact regimens vary, but generally oral terbinafine or an oral azole (except ketoconazole) is administered for 2 to 6 weeks, with immunocompromise necessitating longer courses.

We present a rare case of vegetative Majocchi granuloma secondary to T rubrum infection. A dermatophyte infection should be included in the differential for vegetative lesions, especially in dense hair-bearing areas such as the beard. Treatment generally is straightforward with oral antifungals.

THE DIAGNOSIS: Vegetative Majocchi Granuloma

A biopsy and tissue culture showed acute dermal inflammation with granulomatous features and numerous fungal hyphae within the stratum corneum (Figure 1A), which were confirmed on GrocottGomori methenamine-silver staining (Figure 1B). Gram and Fite stains were negative for bacteria. A tissue culture speciated Trichophyton rubrum, which led to a diagnosis of deep dermatophyte infection (Majocchi granuloma) with a highly unusual clinical presentation of vegetative plaques. Predisposing factors included treatment with topical corticosteroids and possibly poor health and nutritional status at baseline. Our patient was treated with fluconazole 200 mg daily for 6 weeks, with near resolution of lesions at 3-week follow-up (Figure 2).

Dermatophytes are a common cause of superficial skin infections. The classic morphology consists of an annular scaly plaque; however, a wide variety of presentations have been observed (eg, verrucous, vesicular, pustular, granulomatous). Therefore, dermatophyte infections often mimic other dermatologic conditions, including atopic dermatitis, rosacea, psoriasis, bacterial abscess, erythema gyratum repens, lupus, granuloma annulare, cutaneous lymphoma, Hailey-Hailey disease, scarring alopecia, and syphilis.1

Notably, when dermatophytes grow downward along hair follicles causing deeper infection, disruption of the follicular wall can lead to an excessive inflammatory response with granulomatous features.2 Risk factors include cutaneous trauma, long-standing infection, immunocompromise, and treatment with topical corticosteroids.3 This disease evolution clinically appears as a nodule or infiltrated plaque, often without scale. The most well-known example is a kerion on the scalp. Elsewhere on the body, lesions often are termed Majocchi granulomas.2

Vegetative plaques, as seen in our patient, are a highly unusual morphology for deep tinea infection. Guanziroli et al4 reported a case of vegetative lesions on the forearm of a 67-year-old immunocompromised man that were successfully treated with a 3-month course of oral terbinafine after Trichophyton verrucosum was isolated. Skorepova et al5 reported a case of pyoderma vegetans triggered by recurrent Trichophyton mentagrophytes on the dorsal hands of a 64-year-old man with immunoglobulin deficiency of unknown etiology. The lesions were successfully treated with a prolonged course of doxycycline, topical triamcinolone, and intravenous immunoglobulin following 2 initial courses of terbinafine.

The differential diagnosis for vegetative lesions includes pemphigus vegetans, a vegetative variant of pyoderma gangrenosum; halogenoderma; and a variety of infections, including dimorphic fungi (histoplasmosis, blastomycosis), blastomycosislike pyoderma (bacterial), and candidiasis.6 These conditions usually can be distinguished based on histopathology. Clinically, pemphigus vegetans presents with pustules and vegetative lesions, as in our patient, but usually is more diffuse and favors the intertriginous areas. Histology likely would reveal foci of acantholysis and eosinophils. Vegetative pyoderma gangrenosum favors the trunk, particularly in sites of surgical trauma. In our patient, no lesions were present near the abdominal surgical sites, and there was no antecedent cribriform ulceration. Halogenoderma was a strong initial consideration given the localization, presence of large pustules, and history of numerous contrast computed tomography studies; however, our patient’s iodine levels were normal. Infectious etiologies including dimorphic fungi and blastomycosislike pyoderma generally are not restricted to the head and neck, and tissue culture helps exclude them. Vegetative lesions may occur in the setting of other infections, and tissue culture may be necessary to differentiate them if histopathology is not suggestive.

Deep dermatophyte infections require treatment with oral antifungals, as topicals do not penetrate adequately into the hair follicles. Exact regimens vary, but generally oral terbinafine or an oral azole (except ketoconazole) is administered for 2 to 6 weeks, with immunocompromise necessitating longer courses.

We present a rare case of vegetative Majocchi granuloma secondary to T rubrum infection. A dermatophyte infection should be included in the differential for vegetative lesions, especially in dense hair-bearing areas such as the beard. Treatment generally is straightforward with oral antifungals.

- Atzori L, Pau M, Aste N, et al. Dermatophyte infections mimicking other skin diseases: a 154-person case survey of tinea atypica in the district of Cagliari (Italy). Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:410-415.

- Ilkit M, Durdu M, Karakas M. Majocchi’s granuloma: a symptom complex caused by fungal pathogens. Med Mycol. 2012;50:449-457.

- Jevremovic L, Ilijin I, Kostic K, et al. Pyoderma vegetans—a case report. Serbian J Dermatol Venereol. 2017;9:22-28.

- Guanziroli E, Pavia G, Guttadauro A, et al. Deep dermatophytosis caused by Trichophyton verrucosum in an immunosuppressed patient: successful outcome with terbinafine. Mycopathologia. 2019;184:543-545.

- Skorepová M, Stuchlík D. Chronic pyoderma vegetans triggered by Trichophyton mentagrophytes. Mycoses. 2006;49:143-144.

- Reinholz M, Hermans C, Dietrich A, et al. A case of cutaneous vegetating candidiasis in a patient with keratitis-ichthyosis-deafness syndrome. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:537-539.

- Atzori L, Pau M, Aste N, et al. Dermatophyte infections mimicking other skin diseases: a 154-person case survey of tinea atypica in the district of Cagliari (Italy). Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:410-415.

- Ilkit M, Durdu M, Karakas M. Majocchi’s granuloma: a symptom complex caused by fungal pathogens. Med Mycol. 2012;50:449-457.

- Jevremovic L, Ilijin I, Kostic K, et al. Pyoderma vegetans—a case report. Serbian J Dermatol Venereol. 2017;9:22-28.

- Guanziroli E, Pavia G, Guttadauro A, et al. Deep dermatophytosis caused by Trichophyton verrucosum in an immunosuppressed patient: successful outcome with terbinafine. Mycopathologia. 2019;184:543-545.

- Skorepová M, Stuchlík D. Chronic pyoderma vegetans triggered by Trichophyton mentagrophytes. Mycoses. 2006;49:143-144.

- Reinholz M, Hermans C, Dietrich A, et al. A case of cutaneous vegetating candidiasis in a patient with keratitis-ichthyosis-deafness syndrome. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:537-539.

An 86-year-old man was admitted to the hospital for sigmoid colon perforation secondary to ischemic colitis. His medical history consisted of sequelae from atherosclerotic vascular disease. He had no known personal or family history of skin disease. His bowel perforation was surgically repaired, and his clinical status was stabilized, enabling transfer to a transitional care hospital. His course was complicated by delayed healing of the midline abdominal surgical wounds, leading to multiple computed tomography studies with iodinated contrast. One week following arrival at the transitional care hospital, he was noted to have a pustular rash on the face. He was empirically treated with topical steroids, mupirocin, and sulfacetamide. The rash did not improve, and the appearance changed, at which point dermatology was consulted. On evaluation, the patient was afebrile with a normal white blood cell count. Physical examination revealed gray-brown, moist, vegetative plaques on the cheeks with a few large pustules as well as similar-appearing lesions on the neck and upper chest. Attempted removal of a portion of the plaque left an erosion.

Larval Tick Infestation Causing an Eruption of Pruritic Papules and Pustules

Case Reports

Patient 1

A 65-year-old woman presented to the dermatology clinic in July with a pruritic rash of 2 days’ duration that started on the back and spread diffusely. The patient gardened regularly. Physical examination showed inflammatory papules and pustules on the back (Figure 1), as well as the groin, breasts, and ears. There was a punctate black dot in the center of some papules, and dermoscopy revealed ticks (Figure 2). Removal and microscopic examination confirmed larval-stage lone star ticks (Figure 3). The patient was prescribed topical steroids for pruritus as well as oral doxycycline for prophylaxis against tick-borne illnesses.

Patient 2

A 54-year-old man presented to the same clinic in July with pruritic lesions on the back, legs, ankles, and scrotum of 3 days’ duration that first appeared 24 hours after performing yardwork. Physical examination revealed diffusely distributed papules, pustules, and vesicles on the back (Figure 4). Some papules featured a punctate black dot in the center (similar to patient 1), and dermoscopy again revealed ticks. Removal and microscopic examination confirmed larval-stage ticks. The patient was treated with topical steroids and oral antihistamines for pruritus as well as prophylactic oral doxycycline.

Comment

Ticks are well-known human parasites, representing the second most common vector of human infectious disease.1 Ticks have 3 motile stages: larva (or “seed”), nymph, and adult. They can bite humans during all stages. Larval ticks, distinguished by having 6 legs rather than 8 legs in nymphs and adults, can attack in droves and cause an infestation that presents as diffuse, pruritic, erythematous papules and pustules.2-4 The first report of larval tick infestation in humans may have been in 1728 by William Byrd who described finding ticks on the skin that were too small to see without a microscope.5

Identification

The ticks in both of our cases were lone star ticks (Amblyomma americanum). The larval stage of A americanum is a proven cause of cutaneous reaction.6,7 A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE as well as a Google Scholar search using the terms tick, seed tick, or tick bite in combination with rash, eruption, infestation, papule, pustule, or pruritic revealed 6 reported cases of larval tick infestation in the literature (including our case); 5 were caused by A americanum and 1 by Ixodes dammini (now known as Ixodes scapularis); all occurred in July or August.3,7-10 This time frame is consistent with the general tick life cycle across species: Adults feed from April to June, then lay eggs that hatch into larval ticks within 4 to 6 weeks. After hatching, larval ticks climb grass and weeds awaiting a passing host.4

Diagnosis

Larval tick infestation remains a frequently misdiagnosed etiology of diffuse pruritic papules and pustules, especially in urban settings where physicians are less likely to be familiar with this type of manifestation.3,9-11 Larval ticks are submillimeter in size and difficult to appreciate with the naked eye, contributing to misdiagnosis. A punctate black dot may sometimes be seen in papules; however, dermoscopy is critical for accurate diagnosis, as hemorrhagic crust is a frequent misdiagnosis.

Management

In addition to symptomatic therapy, both of our patients received doxycycline as antibiotic prophylaxis for tick-borne illnesses given that a high number of ticks had been attached for more than 2 days.12,13 Antibiotic prophylaxis for tick-borne illness is controversial. The exception is Lyme disease transmitted by nymphal or adult I scapularis when specific conditions are met: the bite must have occurred in an endemic area, doxycycline cannot be contraindicated, estimated duration of attachment is at least 36 hours, and prophylaxis must be started within 72 hours of tick removal.13 There are no official recommendations for the A americanum species or for larval-stage ticks of any species. Larval-stage ticks acting as vectors for disease transmission is not well documented in recent literature, and there currently is limited evidence supporting prophylactic antibiotics for larval tick bites. The presence of spotted fever rickettsioses has been reported (with the exception of Rickettsia rickettsii and Ehrlichia chaffeensis) in larval A americanum ticks, suggesting a theoretical possibility that they could act as disease vectors.3,8,11,14-17 At a minimum, both prompt tick removal and close patient follow-up is warranted.

Conclusion

Human infestation with larval ticks is a common occurrence but can present a diagnostic challenge to an unfamiliar physician. We encourage consideration of larval tick infestation as the etiology of multiple or diffuse pruritic papules with a history of outdoor exposure.

- Sonenshine DE. Biology of Ticks. New York, NY: Oxford University; 1991.

- Alexander JOD. The effects of tick bites. In: Alexander JOD. Arthropods and Human Skin. London, England: Springer London; 1984:363-382.

- Duckworth PF Jr, Hayden GF, Reed CN. Human infestation by Amblyomma americanum larvae (“seed ticks”). South Med J. 1985;78:751-753.

- Parola P, Raoult D. Ticks and tickborne bacterial diseases in humans: an emerging infectious threat. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32:897-928.

- Cropley TG. William Byrd on ticks, 1728. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:187.

- Goddard J. A ten-year study of tick biting in Mississippi: implications for human disease transmission. J Agromedicine. 2002;8:25-32.

- Goddard J, Portugal JS. Cutaneous lesions due to bites by larval Amblyomma americanum ticks. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1373-1375.

- Fibeger EA, Erickson QL, Weintraub BD, et al. Larval tick infestation: a case report and review of tick-borne disease. Cutis. 2008;82:38-46.

- Jones BE. Human ‘seed tick’ infestation: Amblyomma americanum larvae. Arch Dermatol. 1981;117:812-814.

- Fisher EJ, Mo J, Lucky AW. Multiple pruritic papules from lone star tick larvae bites. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:491-494.

- Culp JS. Seed ticks. Am Fam Physician. 1987;36:121-123.

- Perea AE, Hinckley AF, Mead PS. Tick bite prophylaxis: results from a 2012 survey of healthcare providers. Zoonoses Public Health. 2015;62:388-392.

- Tick bites/prevention. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. https://www.cdc.gov/ticks/tickbornediseases/tick-bites-prevention.html. Revised January 10, 2019. Accessed September 17, 2019.

- Moncayo AC, Cohen SB, Fritzen CM, et al. Absence of Rickettsia rickettsii and occurrence of other spotted fever group rickettsiae in ticks from Tennessee. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2010;83:653-657.

- Castellaw AH, Showers J, Goddard J, et al. Detection of vector-borne agents in lone star ticks, Amblyomma americanum (Acari: Ixodidae), from Mississippi. J Med Entomol. 2010;47:473-476.

- Stromdahl EY, Vince MA, Billingsley PM, et al. Rickettsia amblyommii infecting Amblyomma americanum larvae. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2008;8:15-24.

- Long SW, Zhang X, Zhang J, et al. Evaluation of transovarial transmission and transmissibility of Ehrlichia chaffeensis (Rickettsiales: Anaplasmataceae) in Amblyomma americanum (Acari: Ixodidae). J Med Entomol. 2003;40:1000-1004.

Case Reports

Patient 1

A 65-year-old woman presented to the dermatology clinic in July with a pruritic rash of 2 days’ duration that started on the back and spread diffusely. The patient gardened regularly. Physical examination showed inflammatory papules and pustules on the back (Figure 1), as well as the groin, breasts, and ears. There was a punctate black dot in the center of some papules, and dermoscopy revealed ticks (Figure 2). Removal and microscopic examination confirmed larval-stage lone star ticks (Figure 3). The patient was prescribed topical steroids for pruritus as well as oral doxycycline for prophylaxis against tick-borne illnesses.

Patient 2

A 54-year-old man presented to the same clinic in July with pruritic lesions on the back, legs, ankles, and scrotum of 3 days’ duration that first appeared 24 hours after performing yardwork. Physical examination revealed diffusely distributed papules, pustules, and vesicles on the back (Figure 4). Some papules featured a punctate black dot in the center (similar to patient 1), and dermoscopy again revealed ticks. Removal and microscopic examination confirmed larval-stage ticks. The patient was treated with topical steroids and oral antihistamines for pruritus as well as prophylactic oral doxycycline.

Comment

Ticks are well-known human parasites, representing the second most common vector of human infectious disease.1 Ticks have 3 motile stages: larva (or “seed”), nymph, and adult. They can bite humans during all stages. Larval ticks, distinguished by having 6 legs rather than 8 legs in nymphs and adults, can attack in droves and cause an infestation that presents as diffuse, pruritic, erythematous papules and pustules.2-4 The first report of larval tick infestation in humans may have been in 1728 by William Byrd who described finding ticks on the skin that were too small to see without a microscope.5

Identification

The ticks in both of our cases were lone star ticks (Amblyomma americanum). The larval stage of A americanum is a proven cause of cutaneous reaction.6,7 A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE as well as a Google Scholar search using the terms tick, seed tick, or tick bite in combination with rash, eruption, infestation, papule, pustule, or pruritic revealed 6 reported cases of larval tick infestation in the literature (including our case); 5 were caused by A americanum and 1 by Ixodes dammini (now known as Ixodes scapularis); all occurred in July or August.3,7-10 This time frame is consistent with the general tick life cycle across species: Adults feed from April to June, then lay eggs that hatch into larval ticks within 4 to 6 weeks. After hatching, larval ticks climb grass and weeds awaiting a passing host.4

Diagnosis

Larval tick infestation remains a frequently misdiagnosed etiology of diffuse pruritic papules and pustules, especially in urban settings where physicians are less likely to be familiar with this type of manifestation.3,9-11 Larval ticks are submillimeter in size and difficult to appreciate with the naked eye, contributing to misdiagnosis. A punctate black dot may sometimes be seen in papules; however, dermoscopy is critical for accurate diagnosis, as hemorrhagic crust is a frequent misdiagnosis.

Management

In addition to symptomatic therapy, both of our patients received doxycycline as antibiotic prophylaxis for tick-borne illnesses given that a high number of ticks had been attached for more than 2 days.12,13 Antibiotic prophylaxis for tick-borne illness is controversial. The exception is Lyme disease transmitted by nymphal or adult I scapularis when specific conditions are met: the bite must have occurred in an endemic area, doxycycline cannot be contraindicated, estimated duration of attachment is at least 36 hours, and prophylaxis must be started within 72 hours of tick removal.13 There are no official recommendations for the A americanum species or for larval-stage ticks of any species. Larval-stage ticks acting as vectors for disease transmission is not well documented in recent literature, and there currently is limited evidence supporting prophylactic antibiotics for larval tick bites. The presence of spotted fever rickettsioses has been reported (with the exception of Rickettsia rickettsii and Ehrlichia chaffeensis) in larval A americanum ticks, suggesting a theoretical possibility that they could act as disease vectors.3,8,11,14-17 At a minimum, both prompt tick removal and close patient follow-up is warranted.

Conclusion

Human infestation with larval ticks is a common occurrence but can present a diagnostic challenge to an unfamiliar physician. We encourage consideration of larval tick infestation as the etiology of multiple or diffuse pruritic papules with a history of outdoor exposure.

Case Reports

Patient 1

A 65-year-old woman presented to the dermatology clinic in July with a pruritic rash of 2 days’ duration that started on the back and spread diffusely. The patient gardened regularly. Physical examination showed inflammatory papules and pustules on the back (Figure 1), as well as the groin, breasts, and ears. There was a punctate black dot in the center of some papules, and dermoscopy revealed ticks (Figure 2). Removal and microscopic examination confirmed larval-stage lone star ticks (Figure 3). The patient was prescribed topical steroids for pruritus as well as oral doxycycline for prophylaxis against tick-borne illnesses.

Patient 2

A 54-year-old man presented to the same clinic in July with pruritic lesions on the back, legs, ankles, and scrotum of 3 days’ duration that first appeared 24 hours after performing yardwork. Physical examination revealed diffusely distributed papules, pustules, and vesicles on the back (Figure 4). Some papules featured a punctate black dot in the center (similar to patient 1), and dermoscopy again revealed ticks. Removal and microscopic examination confirmed larval-stage ticks. The patient was treated with topical steroids and oral antihistamines for pruritus as well as prophylactic oral doxycycline.

Comment

Ticks are well-known human parasites, representing the second most common vector of human infectious disease.1 Ticks have 3 motile stages: larva (or “seed”), nymph, and adult. They can bite humans during all stages. Larval ticks, distinguished by having 6 legs rather than 8 legs in nymphs and adults, can attack in droves and cause an infestation that presents as diffuse, pruritic, erythematous papules and pustules.2-4 The first report of larval tick infestation in humans may have been in 1728 by William Byrd who described finding ticks on the skin that were too small to see without a microscope.5

Identification

The ticks in both of our cases were lone star ticks (Amblyomma americanum). The larval stage of A americanum is a proven cause of cutaneous reaction.6,7 A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE as well as a Google Scholar search using the terms tick, seed tick, or tick bite in combination with rash, eruption, infestation, papule, pustule, or pruritic revealed 6 reported cases of larval tick infestation in the literature (including our case); 5 were caused by A americanum and 1 by Ixodes dammini (now known as Ixodes scapularis); all occurred in July or August.3,7-10 This time frame is consistent with the general tick life cycle across species: Adults feed from April to June, then lay eggs that hatch into larval ticks within 4 to 6 weeks. After hatching, larval ticks climb grass and weeds awaiting a passing host.4

Diagnosis

Larval tick infestation remains a frequently misdiagnosed etiology of diffuse pruritic papules and pustules, especially in urban settings where physicians are less likely to be familiar with this type of manifestation.3,9-11 Larval ticks are submillimeter in size and difficult to appreciate with the naked eye, contributing to misdiagnosis. A punctate black dot may sometimes be seen in papules; however, dermoscopy is critical for accurate diagnosis, as hemorrhagic crust is a frequent misdiagnosis.

Management

In addition to symptomatic therapy, both of our patients received doxycycline as antibiotic prophylaxis for tick-borne illnesses given that a high number of ticks had been attached for more than 2 days.12,13 Antibiotic prophylaxis for tick-borne illness is controversial. The exception is Lyme disease transmitted by nymphal or adult I scapularis when specific conditions are met: the bite must have occurred in an endemic area, doxycycline cannot be contraindicated, estimated duration of attachment is at least 36 hours, and prophylaxis must be started within 72 hours of tick removal.13 There are no official recommendations for the A americanum species or for larval-stage ticks of any species. Larval-stage ticks acting as vectors for disease transmission is not well documented in recent literature, and there currently is limited evidence supporting prophylactic antibiotics for larval tick bites. The presence of spotted fever rickettsioses has been reported (with the exception of Rickettsia rickettsii and Ehrlichia chaffeensis) in larval A americanum ticks, suggesting a theoretical possibility that they could act as disease vectors.3,8,11,14-17 At a minimum, both prompt tick removal and close patient follow-up is warranted.

Conclusion

Human infestation with larval ticks is a common occurrence but can present a diagnostic challenge to an unfamiliar physician. We encourage consideration of larval tick infestation as the etiology of multiple or diffuse pruritic papules with a history of outdoor exposure.

- Sonenshine DE. Biology of Ticks. New York, NY: Oxford University; 1991.

- Alexander JOD. The effects of tick bites. In: Alexander JOD. Arthropods and Human Skin. London, England: Springer London; 1984:363-382.

- Duckworth PF Jr, Hayden GF, Reed CN. Human infestation by Amblyomma americanum larvae (“seed ticks”). South Med J. 1985;78:751-753.

- Parola P, Raoult D. Ticks and tickborne bacterial diseases in humans: an emerging infectious threat. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32:897-928.

- Cropley TG. William Byrd on ticks, 1728. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:187.

- Goddard J. A ten-year study of tick biting in Mississippi: implications for human disease transmission. J Agromedicine. 2002;8:25-32.

- Goddard J, Portugal JS. Cutaneous lesions due to bites by larval Amblyomma americanum ticks. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1373-1375.

- Fibeger EA, Erickson QL, Weintraub BD, et al. Larval tick infestation: a case report and review of tick-borne disease. Cutis. 2008;82:38-46.

- Jones BE. Human ‘seed tick’ infestation: Amblyomma americanum larvae. Arch Dermatol. 1981;117:812-814.

- Fisher EJ, Mo J, Lucky AW. Multiple pruritic papules from lone star tick larvae bites. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:491-494.

- Culp JS. Seed ticks. Am Fam Physician. 1987;36:121-123.

- Perea AE, Hinckley AF, Mead PS. Tick bite prophylaxis: results from a 2012 survey of healthcare providers. Zoonoses Public Health. 2015;62:388-392.

- Tick bites/prevention. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. https://www.cdc.gov/ticks/tickbornediseases/tick-bites-prevention.html. Revised January 10, 2019. Accessed September 17, 2019.

- Moncayo AC, Cohen SB, Fritzen CM, et al. Absence of Rickettsia rickettsii and occurrence of other spotted fever group rickettsiae in ticks from Tennessee. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2010;83:653-657.

- Castellaw AH, Showers J, Goddard J, et al. Detection of vector-borne agents in lone star ticks, Amblyomma americanum (Acari: Ixodidae), from Mississippi. J Med Entomol. 2010;47:473-476.

- Stromdahl EY, Vince MA, Billingsley PM, et al. Rickettsia amblyommii infecting Amblyomma americanum larvae. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2008;8:15-24.

- Long SW, Zhang X, Zhang J, et al. Evaluation of transovarial transmission and transmissibility of Ehrlichia chaffeensis (Rickettsiales: Anaplasmataceae) in Amblyomma americanum (Acari: Ixodidae). J Med Entomol. 2003;40:1000-1004.

- Sonenshine DE. Biology of Ticks. New York, NY: Oxford University; 1991.

- Alexander JOD. The effects of tick bites. In: Alexander JOD. Arthropods and Human Skin. London, England: Springer London; 1984:363-382.

- Duckworth PF Jr, Hayden GF, Reed CN. Human infestation by Amblyomma americanum larvae (“seed ticks”). South Med J. 1985;78:751-753.

- Parola P, Raoult D. Ticks and tickborne bacterial diseases in humans: an emerging infectious threat. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32:897-928.

- Cropley TG. William Byrd on ticks, 1728. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:187.

- Goddard J. A ten-year study of tick biting in Mississippi: implications for human disease transmission. J Agromedicine. 2002;8:25-32.

- Goddard J, Portugal JS. Cutaneous lesions due to bites by larval Amblyomma americanum ticks. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1373-1375.

- Fibeger EA, Erickson QL, Weintraub BD, et al. Larval tick infestation: a case report and review of tick-borne disease. Cutis. 2008;82:38-46.

- Jones BE. Human ‘seed tick’ infestation: Amblyomma americanum larvae. Arch Dermatol. 1981;117:812-814.

- Fisher EJ, Mo J, Lucky AW. Multiple pruritic papules from lone star tick larvae bites. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:491-494.

- Culp JS. Seed ticks. Am Fam Physician. 1987;36:121-123.

- Perea AE, Hinckley AF, Mead PS. Tick bite prophylaxis: results from a 2012 survey of healthcare providers. Zoonoses Public Health. 2015;62:388-392.

- Tick bites/prevention. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. https://www.cdc.gov/ticks/tickbornediseases/tick-bites-prevention.html. Revised January 10, 2019. Accessed September 17, 2019.

- Moncayo AC, Cohen SB, Fritzen CM, et al. Absence of Rickettsia rickettsii and occurrence of other spotted fever group rickettsiae in ticks from Tennessee. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2010;83:653-657.

- Castellaw AH, Showers J, Goddard J, et al. Detection of vector-borne agents in lone star ticks, Amblyomma americanum (Acari: Ixodidae), from Mississippi. J Med Entomol. 2010;47:473-476.

- Stromdahl EY, Vince MA, Billingsley PM, et al. Rickettsia amblyommii infecting Amblyomma americanum larvae. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2008;8:15-24.

- Long SW, Zhang X, Zhang J, et al. Evaluation of transovarial transmission and transmissibility of Ehrlichia chaffeensis (Rickettsiales: Anaplasmataceae) in Amblyomma americanum (Acari: Ixodidae). J Med Entomol. 2003;40:1000-1004.

Practice Points

- Larval (“seed”) ticks can attack in droves, causing a widespread rash consisting of pruritic erythematous papules and pustules.

- Tiny black dots can be seen in some papules, which are the seed ticks themselves. Careful dermoscopic examination is critical to avoid easy misdiagnosis as hemorrhagic crust.

- We encourage providers to include larval tick infestation in the differential for eruptive pruritic papules and pustules with a history of outdoor exposure, especially during the summer months.