User login

From neuroplasticity to psychoplasticity: Psilocybin may reverse personality disorders and political fanaticism

One of psychiatry’s long-standing dogmas is that personality disorders are enduring, unchangeable, and not amenable to treatment with potent psychotropics or intensive psychotherapy. I propose that this dogma may soon be shattered.

Several other dogmas in psychiatry have been demolished over the past several decades:

- that “insanity” is completely irreversible and requires lifetime institutionalization. The serendipitous discovery of chlorpromazine1 annihilated this centuries-old dogma

- that chronic, severe, refractory depression (with ongoing suicidal urges) that fails to improve with pharmacotherapy or electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is hopeless and untreatable, until ketamine not only pulverized this dogma, but did it with lightning speed, dazzling us all2

- that dissociative agents such as ketamine are dangerous and condemnable drugs of abuse, until the therapeutic effect of ketamine slayed that dragon3

- that ECT “fries” the brain (as malevolently propagated by antipsychiatry cults), which was completely disproven by neuroimaging studies that show the hippocampus (which shrinks during depression) actually grows by >10% after a few ECT sessions4

- that psychotherapy is not a “real” treatment because talking cannot reverse a psychiatric brain disorder, until studies showed significant neuroplasticity with psychotherapy and decrease in inflammatory biomarkers with cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT)5

- that persons with refractory hallucinations and delusions are doomed to a life of disability, until clozapine torpedoed that pessimistic dogma6

- that hallucinogens/psychedelics are dangerous and should be banned, until a jarring paradigm shift occurred with the discovery of psilocybin’s transformative effects, and the remarkable therapeutic effects of its mystical trips.7

Psilocybin’s therapeutic effects

Psilocybin has already proved to have a strong and lasting effect on depression and promises to have therapeutic benefits for patients with substance use disorders, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and anxiety.8 In addition, when the multiple psychological and neurobiological effects of psilocybin (and of other psychedelics) are examined, I see a very promising path to amelioration of severe personality disorders such as psychopathy, antisocial behavior, and narcissism. The mechanism(s) of action of psilocybin on the human brain are drastically different from any man-made psychotropic agent. As a psychiatric neuroscientist, I envision the neurologic impact of psilocybin to be conducive to a complete transformation of a patient’s view of themself, other people, and the meaning of life. It is reminiscent of religious conversion.

The psychological effects of psilocybin in humans have been described as follows:

- emotional breakthrough9

- increased psychological flexibility,10,11 a very cortical effect

- mystical experience,12 which results in sudden and significant changes in behavior and perception and includes the following dimensions: sacredness, noetic quality, deeply felt positive mood, ineffability, paradoxicality, and transcendence of time and space13

- oceanic boundlessness, feeling “one with the universe”14

- universal interconnectedness, insightfulness, blissful state, spiritual experience14

- ego dissolution,15 with loss of one’s personal identity

- increased neuroplasticity16

- changes in cognition and increase in insight.17

The neurobiological effects of psilocybin are mediated by serotonin 5HT2A agonism and include the following18:

- reduction in the activity of the medial prefrontal cortex, which regulates memory, attention, inhibitory control, and habit

- a decrease in the connectivity between the medial prefrontal cortex and the posterior cingulate cortex, which regulates memory and emotions

- reducing the default mode network, which is active during rest, stimulating internal thoughts and reminiscing about previous feelings and events, sometimes including ruminations. Psilocybin reverses those processes to thinking about others, not just the self, and becoming more open-minded about the world and other people. This can be therapeutic for depression, which is often associated with negative ruminations but also with entrenched habits (addictive behaviors), anxiety, PTSD, and obsessive-compulsive disorders

- increased global functional connectivity among various brain networks, leading to stronger functional integration of behavior

- collapse of major cortical oscillatory rhythms such as alpha and others that perpetuate “prior” beliefs

- extensive neuroplasticity and recalibration of thought processes and decomposition of pathological beliefs, referred to as REBUS (relaxed beliefs under psychedelics).

The bottom line is psilocybin and other psychedelics can dramatically alter, reshape, and relax rigid beliefs and personality traits by decreasing “neuroticism” and increasing “extraversion,” insightfulness, openness, and possibly conscientiousness.19 Although no studies of psychedelics in psychopathic, antisocial, or narcissistic personality disorders have been conducted, it is very reasonable to speculate that psilocybin may reverse traits of these disorders such as callousness, lack of empathy, and pathological self-centeredness.

Going further, a preliminary report suggests psilocybin can modify political views by decreasing authoritarianism and increasing libertarianism.20,21 In the current political zeitgeist, could psychedelics such as psilocybin reduce or even eliminate political extremism and visceral hatred on all sides? It would be remarkable research to carry out to heal a politically divided populace.The dogma of untreatable personality disorders or hopelessly entrenched political extremism is on the chopping block, and psychedelics offer hope to splinter those beliefs by concurrently remodeling brain tissue (neuroplasticity) and rectifying the mindset (psychoplasticity).

1. Delay J, Deniker P. Neuroleptic effects of chlorpromazine in therapeutics of neuropsychiatry. J Clin Exp Psychopathol. 1955;16(2):104-112.

2. Walsh Z, Mollaahmetoglu OM, Rootman, J, et al. Ketamine for the treatment of mental health and substance use disorders: comprehensive systematic review. BJPsych Open. 2021;8(1):e19. doi:10.1192/bjo.2021.1061

3. Lener MS, Kadriu B, Zarate CA Jr. Ketamine and beyond: investigations into the potential of glutamatergic agents to treat depression. Drugs. 2017;77(4):381-401.

4. Ayers B, Leaver A, Woods RP, et al. Structural plasticity of the hippocampus and amygdala induced by electroconvulsive therapy in major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2016;79(4):282-292.

5. Cao B, Li R, Ding L, Xu J, et al. Does cognitive behaviour therapy affect peripheral inflammation of depression? A protocol for the systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2021;11(12):e048162. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-048162

6. Wagner E, Siafis S, Fernando P, et al. Efficacy and safety of clozapine in psychotic disorders—a systematic quantitative meta-review. Transl Psychiatry. 2021;11(1):487.

7. Daws RE, Timmermann C, Giribaldi B, et al. Increased global integration in the brain after psilocybin therapy for depression. Nat Med. 2022;28(4):844-851.

8. Pearson C, Siegel J, Gold JA. Psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy for depression: emerging research on a psychedelic compound with a rich history. J Neurol Sci. 2022;434:120096. doi:10.1016/j.jns.2021.120096

9. Roseman L, Haijen E, Idialu-Ikato K, et al. Emotional breakthrough and psychedelics: validation of the Emotional Breakthrough Inventory. J Psychopharmacol. 2019;33(9):1076-1087.

10. Davis AK, Barrett FS, Griffiths RR. Psychological flexibility mediates the relations between acute psychedelic effects and subjective decreases in depression and anxiety. J Contextual Behav Sci. 2020;15:39-45.

11. Hayes SC, Luoma JB, Bond FW, et al. Acceptance and commitment therapy: model, processes and outcomes. Behav Res Ther. 2006;44(1):1-25.

12. Ross S, Bossis A, Guss J, et al. Rapid and sustained symptom reduction following psilocybin treatment for anxiety and depression in patients with life-threatening cancer: a randomized controlled trial. J Psychopharmacol. 2016;30(12):1165-1180.

13. Stace WT. Mysticism and Philosophy. Macmillan Pub Ltd; 1960:37.

14. Barrett FS, Griffiths RR. Classic hallucinogens and mystical experiences: phenomenology and neural correlates. Curr Top Behav Neurosci. 2018;36:393-430.

15. Nour MM, Evans L, Nutt D, et al. Ego-dissolution and psychedelics: validation of the Ego-Dissolution Inventory (EDI). Front Hum Neurosci. 2016;10:269. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2016.00269

16. Olson DE. The subjective effects of psychedelics may not be necessary for their enduring therapeutic effects. ACS Pharmacol Transl Sci. 2020;4(2):563-567.

17. Carhart-Harris RL, Bolstridge M, Day CMJ, et al. Psilocybin with psychological support for treatment-resistant depression: six-month follow-up. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2018;235(2):399-408.

18. Carhart-Harris RL. How do psychedelics work? Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2019;32(1):16-21.

19. Erritzoe D, Roseman L, Nour MM, et al. Effects of psilocybin therapy on personality structure. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2018;138(5):368-378.

20. Lyons T, Carhart-Harris RL. Increased nature relatedness and decreased authoritarian political views after psilocybin for treatment-resistant depression. J Psychopharmacol. 2018;32(7):811-819.

21. Nour MM, Evans L, Carhart-Harris RL. Psychedelics, personality and political perspectives. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2017;49(3):182-191.

One of psychiatry’s long-standing dogmas is that personality disorders are enduring, unchangeable, and not amenable to treatment with potent psychotropics or intensive psychotherapy. I propose that this dogma may soon be shattered.

Several other dogmas in psychiatry have been demolished over the past several decades:

- that “insanity” is completely irreversible and requires lifetime institutionalization. The serendipitous discovery of chlorpromazine1 annihilated this centuries-old dogma

- that chronic, severe, refractory depression (with ongoing suicidal urges) that fails to improve with pharmacotherapy or electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is hopeless and untreatable, until ketamine not only pulverized this dogma, but did it with lightning speed, dazzling us all2

- that dissociative agents such as ketamine are dangerous and condemnable drugs of abuse, until the therapeutic effect of ketamine slayed that dragon3

- that ECT “fries” the brain (as malevolently propagated by antipsychiatry cults), which was completely disproven by neuroimaging studies that show the hippocampus (which shrinks during depression) actually grows by >10% after a few ECT sessions4

- that psychotherapy is not a “real” treatment because talking cannot reverse a psychiatric brain disorder, until studies showed significant neuroplasticity with psychotherapy and decrease in inflammatory biomarkers with cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT)5

- that persons with refractory hallucinations and delusions are doomed to a life of disability, until clozapine torpedoed that pessimistic dogma6

- that hallucinogens/psychedelics are dangerous and should be banned, until a jarring paradigm shift occurred with the discovery of psilocybin’s transformative effects, and the remarkable therapeutic effects of its mystical trips.7

Psilocybin’s therapeutic effects

Psilocybin has already proved to have a strong and lasting effect on depression and promises to have therapeutic benefits for patients with substance use disorders, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and anxiety.8 In addition, when the multiple psychological and neurobiological effects of psilocybin (and of other psychedelics) are examined, I see a very promising path to amelioration of severe personality disorders such as psychopathy, antisocial behavior, and narcissism. The mechanism(s) of action of psilocybin on the human brain are drastically different from any man-made psychotropic agent. As a psychiatric neuroscientist, I envision the neurologic impact of psilocybin to be conducive to a complete transformation of a patient’s view of themself, other people, and the meaning of life. It is reminiscent of religious conversion.

The psychological effects of psilocybin in humans have been described as follows:

- emotional breakthrough9

- increased psychological flexibility,10,11 a very cortical effect

- mystical experience,12 which results in sudden and significant changes in behavior and perception and includes the following dimensions: sacredness, noetic quality, deeply felt positive mood, ineffability, paradoxicality, and transcendence of time and space13

- oceanic boundlessness, feeling “one with the universe”14

- universal interconnectedness, insightfulness, blissful state, spiritual experience14

- ego dissolution,15 with loss of one’s personal identity

- increased neuroplasticity16

- changes in cognition and increase in insight.17

The neurobiological effects of psilocybin are mediated by serotonin 5HT2A agonism and include the following18:

- reduction in the activity of the medial prefrontal cortex, which regulates memory, attention, inhibitory control, and habit

- a decrease in the connectivity between the medial prefrontal cortex and the posterior cingulate cortex, which regulates memory and emotions

- reducing the default mode network, which is active during rest, stimulating internal thoughts and reminiscing about previous feelings and events, sometimes including ruminations. Psilocybin reverses those processes to thinking about others, not just the self, and becoming more open-minded about the world and other people. This can be therapeutic for depression, which is often associated with negative ruminations but also with entrenched habits (addictive behaviors), anxiety, PTSD, and obsessive-compulsive disorders

- increased global functional connectivity among various brain networks, leading to stronger functional integration of behavior

- collapse of major cortical oscillatory rhythms such as alpha and others that perpetuate “prior” beliefs

- extensive neuroplasticity and recalibration of thought processes and decomposition of pathological beliefs, referred to as REBUS (relaxed beliefs under psychedelics).

The bottom line is psilocybin and other psychedelics can dramatically alter, reshape, and relax rigid beliefs and personality traits by decreasing “neuroticism” and increasing “extraversion,” insightfulness, openness, and possibly conscientiousness.19 Although no studies of psychedelics in psychopathic, antisocial, or narcissistic personality disorders have been conducted, it is very reasonable to speculate that psilocybin may reverse traits of these disorders such as callousness, lack of empathy, and pathological self-centeredness.

Going further, a preliminary report suggests psilocybin can modify political views by decreasing authoritarianism and increasing libertarianism.20,21 In the current political zeitgeist, could psychedelics such as psilocybin reduce or even eliminate political extremism and visceral hatred on all sides? It would be remarkable research to carry out to heal a politically divided populace.The dogma of untreatable personality disorders or hopelessly entrenched political extremism is on the chopping block, and psychedelics offer hope to splinter those beliefs by concurrently remodeling brain tissue (neuroplasticity) and rectifying the mindset (psychoplasticity).

One of psychiatry’s long-standing dogmas is that personality disorders are enduring, unchangeable, and not amenable to treatment with potent psychotropics or intensive psychotherapy. I propose that this dogma may soon be shattered.

Several other dogmas in psychiatry have been demolished over the past several decades:

- that “insanity” is completely irreversible and requires lifetime institutionalization. The serendipitous discovery of chlorpromazine1 annihilated this centuries-old dogma

- that chronic, severe, refractory depression (with ongoing suicidal urges) that fails to improve with pharmacotherapy or electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is hopeless and untreatable, until ketamine not only pulverized this dogma, but did it with lightning speed, dazzling us all2

- that dissociative agents such as ketamine are dangerous and condemnable drugs of abuse, until the therapeutic effect of ketamine slayed that dragon3

- that ECT “fries” the brain (as malevolently propagated by antipsychiatry cults), which was completely disproven by neuroimaging studies that show the hippocampus (which shrinks during depression) actually grows by >10% after a few ECT sessions4

- that psychotherapy is not a “real” treatment because talking cannot reverse a psychiatric brain disorder, until studies showed significant neuroplasticity with psychotherapy and decrease in inflammatory biomarkers with cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT)5

- that persons with refractory hallucinations and delusions are doomed to a life of disability, until clozapine torpedoed that pessimistic dogma6

- that hallucinogens/psychedelics are dangerous and should be banned, until a jarring paradigm shift occurred with the discovery of psilocybin’s transformative effects, and the remarkable therapeutic effects of its mystical trips.7

Psilocybin’s therapeutic effects

Psilocybin has already proved to have a strong and lasting effect on depression and promises to have therapeutic benefits for patients with substance use disorders, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and anxiety.8 In addition, when the multiple psychological and neurobiological effects of psilocybin (and of other psychedelics) are examined, I see a very promising path to amelioration of severe personality disorders such as psychopathy, antisocial behavior, and narcissism. The mechanism(s) of action of psilocybin on the human brain are drastically different from any man-made psychotropic agent. As a psychiatric neuroscientist, I envision the neurologic impact of psilocybin to be conducive to a complete transformation of a patient’s view of themself, other people, and the meaning of life. It is reminiscent of religious conversion.

The psychological effects of psilocybin in humans have been described as follows:

- emotional breakthrough9

- increased psychological flexibility,10,11 a very cortical effect

- mystical experience,12 which results in sudden and significant changes in behavior and perception and includes the following dimensions: sacredness, noetic quality, deeply felt positive mood, ineffability, paradoxicality, and transcendence of time and space13

- oceanic boundlessness, feeling “one with the universe”14

- universal interconnectedness, insightfulness, blissful state, spiritual experience14

- ego dissolution,15 with loss of one’s personal identity

- increased neuroplasticity16

- changes in cognition and increase in insight.17

The neurobiological effects of psilocybin are mediated by serotonin 5HT2A agonism and include the following18:

- reduction in the activity of the medial prefrontal cortex, which regulates memory, attention, inhibitory control, and habit

- a decrease in the connectivity between the medial prefrontal cortex and the posterior cingulate cortex, which regulates memory and emotions

- reducing the default mode network, which is active during rest, stimulating internal thoughts and reminiscing about previous feelings and events, sometimes including ruminations. Psilocybin reverses those processes to thinking about others, not just the self, and becoming more open-minded about the world and other people. This can be therapeutic for depression, which is often associated with negative ruminations but also with entrenched habits (addictive behaviors), anxiety, PTSD, and obsessive-compulsive disorders

- increased global functional connectivity among various brain networks, leading to stronger functional integration of behavior

- collapse of major cortical oscillatory rhythms such as alpha and others that perpetuate “prior” beliefs

- extensive neuroplasticity and recalibration of thought processes and decomposition of pathological beliefs, referred to as REBUS (relaxed beliefs under psychedelics).

The bottom line is psilocybin and other psychedelics can dramatically alter, reshape, and relax rigid beliefs and personality traits by decreasing “neuroticism” and increasing “extraversion,” insightfulness, openness, and possibly conscientiousness.19 Although no studies of psychedelics in psychopathic, antisocial, or narcissistic personality disorders have been conducted, it is very reasonable to speculate that psilocybin may reverse traits of these disorders such as callousness, lack of empathy, and pathological self-centeredness.

Going further, a preliminary report suggests psilocybin can modify political views by decreasing authoritarianism and increasing libertarianism.20,21 In the current political zeitgeist, could psychedelics such as psilocybin reduce or even eliminate political extremism and visceral hatred on all sides? It would be remarkable research to carry out to heal a politically divided populace.The dogma of untreatable personality disorders or hopelessly entrenched political extremism is on the chopping block, and psychedelics offer hope to splinter those beliefs by concurrently remodeling brain tissue (neuroplasticity) and rectifying the mindset (psychoplasticity).

1. Delay J, Deniker P. Neuroleptic effects of chlorpromazine in therapeutics of neuropsychiatry. J Clin Exp Psychopathol. 1955;16(2):104-112.

2. Walsh Z, Mollaahmetoglu OM, Rootman, J, et al. Ketamine for the treatment of mental health and substance use disorders: comprehensive systematic review. BJPsych Open. 2021;8(1):e19. doi:10.1192/bjo.2021.1061

3. Lener MS, Kadriu B, Zarate CA Jr. Ketamine and beyond: investigations into the potential of glutamatergic agents to treat depression. Drugs. 2017;77(4):381-401.

4. Ayers B, Leaver A, Woods RP, et al. Structural plasticity of the hippocampus and amygdala induced by electroconvulsive therapy in major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2016;79(4):282-292.

5. Cao B, Li R, Ding L, Xu J, et al. Does cognitive behaviour therapy affect peripheral inflammation of depression? A protocol for the systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2021;11(12):e048162. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-048162

6. Wagner E, Siafis S, Fernando P, et al. Efficacy and safety of clozapine in psychotic disorders—a systematic quantitative meta-review. Transl Psychiatry. 2021;11(1):487.

7. Daws RE, Timmermann C, Giribaldi B, et al. Increased global integration in the brain after psilocybin therapy for depression. Nat Med. 2022;28(4):844-851.

8. Pearson C, Siegel J, Gold JA. Psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy for depression: emerging research on a psychedelic compound with a rich history. J Neurol Sci. 2022;434:120096. doi:10.1016/j.jns.2021.120096

9. Roseman L, Haijen E, Idialu-Ikato K, et al. Emotional breakthrough and psychedelics: validation of the Emotional Breakthrough Inventory. J Psychopharmacol. 2019;33(9):1076-1087.

10. Davis AK, Barrett FS, Griffiths RR. Psychological flexibility mediates the relations between acute psychedelic effects and subjective decreases in depression and anxiety. J Contextual Behav Sci. 2020;15:39-45.

11. Hayes SC, Luoma JB, Bond FW, et al. Acceptance and commitment therapy: model, processes and outcomes. Behav Res Ther. 2006;44(1):1-25.

12. Ross S, Bossis A, Guss J, et al. Rapid and sustained symptom reduction following psilocybin treatment for anxiety and depression in patients with life-threatening cancer: a randomized controlled trial. J Psychopharmacol. 2016;30(12):1165-1180.

13. Stace WT. Mysticism and Philosophy. Macmillan Pub Ltd; 1960:37.

14. Barrett FS, Griffiths RR. Classic hallucinogens and mystical experiences: phenomenology and neural correlates. Curr Top Behav Neurosci. 2018;36:393-430.

15. Nour MM, Evans L, Nutt D, et al. Ego-dissolution and psychedelics: validation of the Ego-Dissolution Inventory (EDI). Front Hum Neurosci. 2016;10:269. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2016.00269

16. Olson DE. The subjective effects of psychedelics may not be necessary for their enduring therapeutic effects. ACS Pharmacol Transl Sci. 2020;4(2):563-567.

17. Carhart-Harris RL, Bolstridge M, Day CMJ, et al. Psilocybin with psychological support for treatment-resistant depression: six-month follow-up. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2018;235(2):399-408.

18. Carhart-Harris RL. How do psychedelics work? Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2019;32(1):16-21.

19. Erritzoe D, Roseman L, Nour MM, et al. Effects of psilocybin therapy on personality structure. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2018;138(5):368-378.

20. Lyons T, Carhart-Harris RL. Increased nature relatedness and decreased authoritarian political views after psilocybin for treatment-resistant depression. J Psychopharmacol. 2018;32(7):811-819.

21. Nour MM, Evans L, Carhart-Harris RL. Psychedelics, personality and political perspectives. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2017;49(3):182-191.

1. Delay J, Deniker P. Neuroleptic effects of chlorpromazine in therapeutics of neuropsychiatry. J Clin Exp Psychopathol. 1955;16(2):104-112.

2. Walsh Z, Mollaahmetoglu OM, Rootman, J, et al. Ketamine for the treatment of mental health and substance use disorders: comprehensive systematic review. BJPsych Open. 2021;8(1):e19. doi:10.1192/bjo.2021.1061

3. Lener MS, Kadriu B, Zarate CA Jr. Ketamine and beyond: investigations into the potential of glutamatergic agents to treat depression. Drugs. 2017;77(4):381-401.

4. Ayers B, Leaver A, Woods RP, et al. Structural plasticity of the hippocampus and amygdala induced by electroconvulsive therapy in major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2016;79(4):282-292.

5. Cao B, Li R, Ding L, Xu J, et al. Does cognitive behaviour therapy affect peripheral inflammation of depression? A protocol for the systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2021;11(12):e048162. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-048162

6. Wagner E, Siafis S, Fernando P, et al. Efficacy and safety of clozapine in psychotic disorders—a systematic quantitative meta-review. Transl Psychiatry. 2021;11(1):487.

7. Daws RE, Timmermann C, Giribaldi B, et al. Increased global integration in the brain after psilocybin therapy for depression. Nat Med. 2022;28(4):844-851.

8. Pearson C, Siegel J, Gold JA. Psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy for depression: emerging research on a psychedelic compound with a rich history. J Neurol Sci. 2022;434:120096. doi:10.1016/j.jns.2021.120096

9. Roseman L, Haijen E, Idialu-Ikato K, et al. Emotional breakthrough and psychedelics: validation of the Emotional Breakthrough Inventory. J Psychopharmacol. 2019;33(9):1076-1087.

10. Davis AK, Barrett FS, Griffiths RR. Psychological flexibility mediates the relations between acute psychedelic effects and subjective decreases in depression and anxiety. J Contextual Behav Sci. 2020;15:39-45.

11. Hayes SC, Luoma JB, Bond FW, et al. Acceptance and commitment therapy: model, processes and outcomes. Behav Res Ther. 2006;44(1):1-25.

12. Ross S, Bossis A, Guss J, et al. Rapid and sustained symptom reduction following psilocybin treatment for anxiety and depression in patients with life-threatening cancer: a randomized controlled trial. J Psychopharmacol. 2016;30(12):1165-1180.

13. Stace WT. Mysticism and Philosophy. Macmillan Pub Ltd; 1960:37.

14. Barrett FS, Griffiths RR. Classic hallucinogens and mystical experiences: phenomenology and neural correlates. Curr Top Behav Neurosci. 2018;36:393-430.

15. Nour MM, Evans L, Nutt D, et al. Ego-dissolution and psychedelics: validation of the Ego-Dissolution Inventory (EDI). Front Hum Neurosci. 2016;10:269. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2016.00269

16. Olson DE. The subjective effects of psychedelics may not be necessary for their enduring therapeutic effects. ACS Pharmacol Transl Sci. 2020;4(2):563-567.

17. Carhart-Harris RL, Bolstridge M, Day CMJ, et al. Psilocybin with psychological support for treatment-resistant depression: six-month follow-up. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2018;235(2):399-408.

18. Carhart-Harris RL. How do psychedelics work? Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2019;32(1):16-21.

19. Erritzoe D, Roseman L, Nour MM, et al. Effects of psilocybin therapy on personality structure. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2018;138(5):368-378.

20. Lyons T, Carhart-Harris RL. Increased nature relatedness and decreased authoritarian political views after psilocybin for treatment-resistant depression. J Psychopharmacol. 2018;32(7):811-819.

21. Nour MM, Evans L, Carhart-Harris RL. Psychedelics, personality and political perspectives. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2017;49(3):182-191.

Reversing depression: A plethora of therapeutic strategies and mechanisms

Despite much progress, major depressive disorder (MDD) continues to be a challenging and life-threatening neuropsychiatric disorder. It is highly prevalent and afflicts tens of millions of Americans.

It is also ranked as the No. 1 disabling medical (not just psychiatric) condition by the World Health Organization.1 A significant proportion of patients with MDD do not respond adequately to several rounds of antidepressant medications,2 and many are labeled as having “treatment-resistant depression” (TRD).

In a previous article, I provocatively proposed that TRD is a myth.3 What I meant is that in a heterogeneous syndrome such as depression, failure to respond to 1, 2, or even 3 antidepressants should not imply TRD, because there is a “right treatment” that has not yet been identified for a given depressed patient. Most of those labeled as TRD have simply not yet received the pharmacotherapy or somatic therapy with the requisite mechanism of action for their variant of depression within a heterogeneous syndrome. IV ketamine, which, astonishingly, often reverses severe TRD of chronic duration within a few hours, is a prime example of why the term TRD is often used prematurely. Ketamine’s mechanism of action (immediate neuroplasticity via glutamate N-methyl-

Some clinicians may not be aware of the abundance of mechanisms of action currently available for the treatment of MDD as well as bipolar depression. Many practitioners, in both psychiatry and primary care, usually start the treatment of depression with a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, and if that does not produce a response or remission, they might switch to a serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor. If that does not control the patient’s depressive symptoms, they start entertaining the notion that the patient may have TRD, not realizing that they have barely scratched the surface of the many therapeutic options and mechanisms of action, one of which could be the “best match” for a given patient.4

There will come a day when “precision psychiatry” finally arrives, and specific biomarkers will be developed to identify the “right” treatment for each patient within the heterogenous syndrome of depression.5 Until that day arrives, the treatment of depression will continue to be a process of trial and error, and hit or miss. But research will eventually discover genetic, neurochemical, neurophysiological, neuroimaging, or neuroimmune biomarkers that will rapidly guide clinicians to the correct treatment. This is critical to avoid inordinate delays in achieving remission and avert the ever-present risk of suicidal behavior.

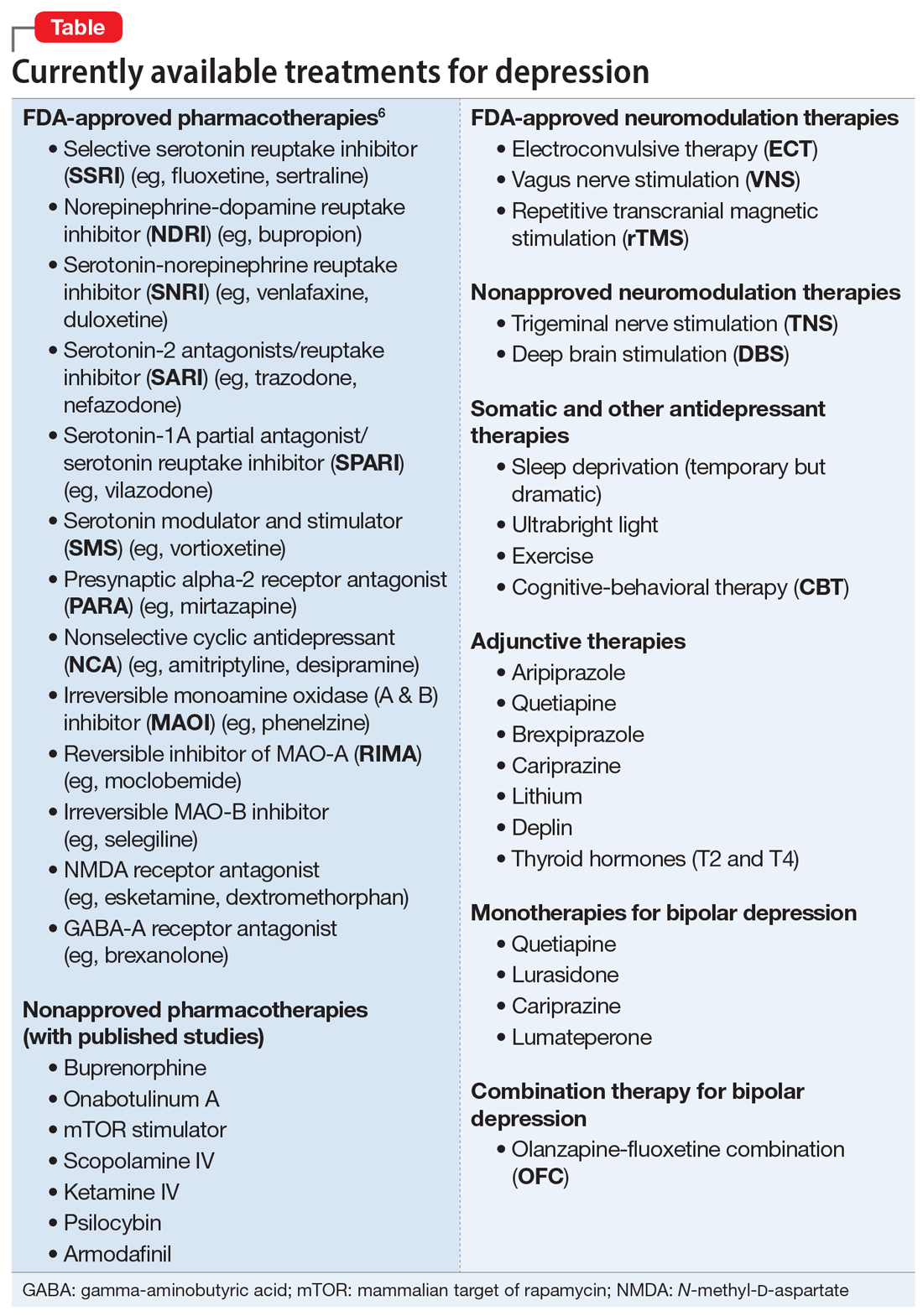

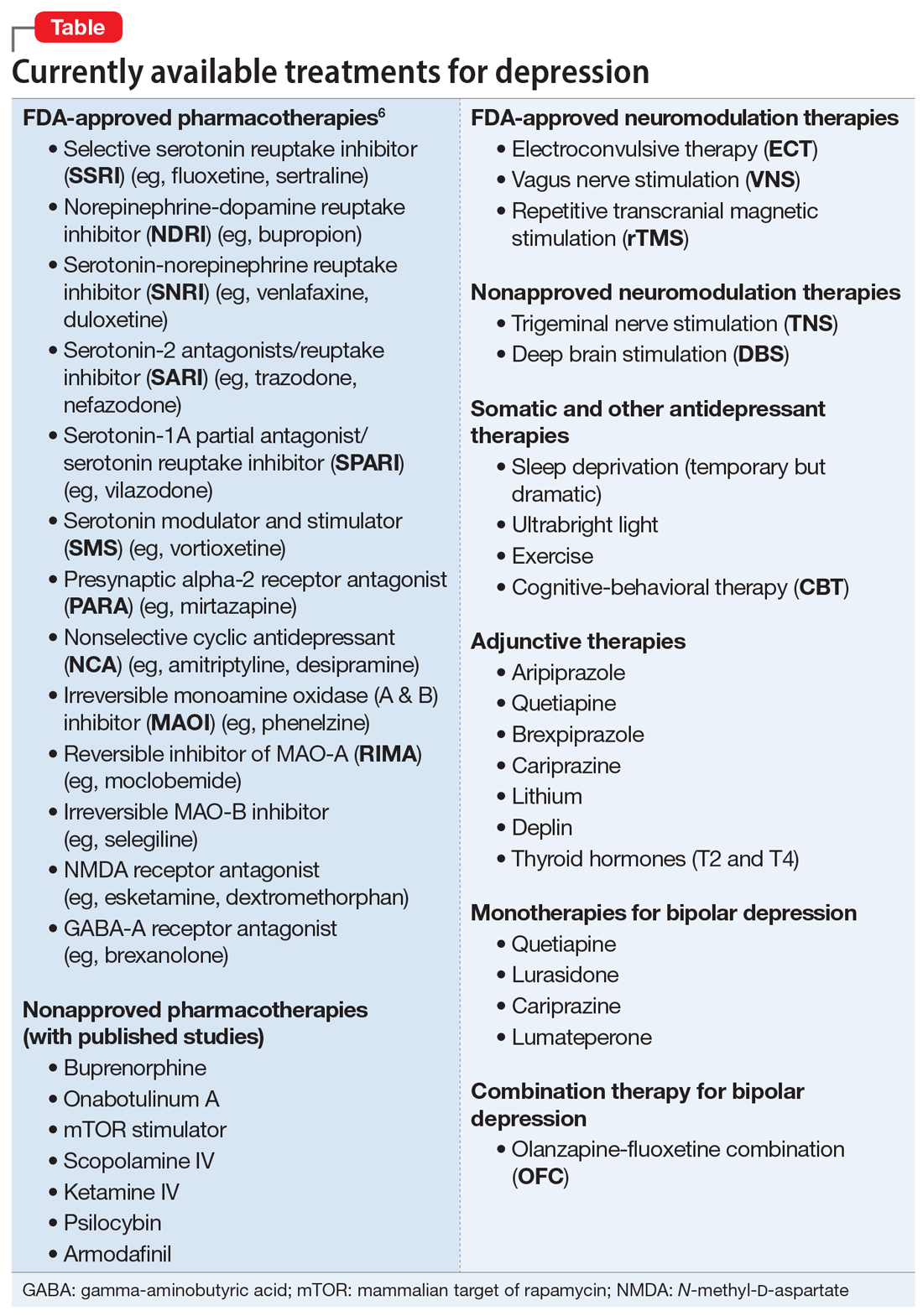

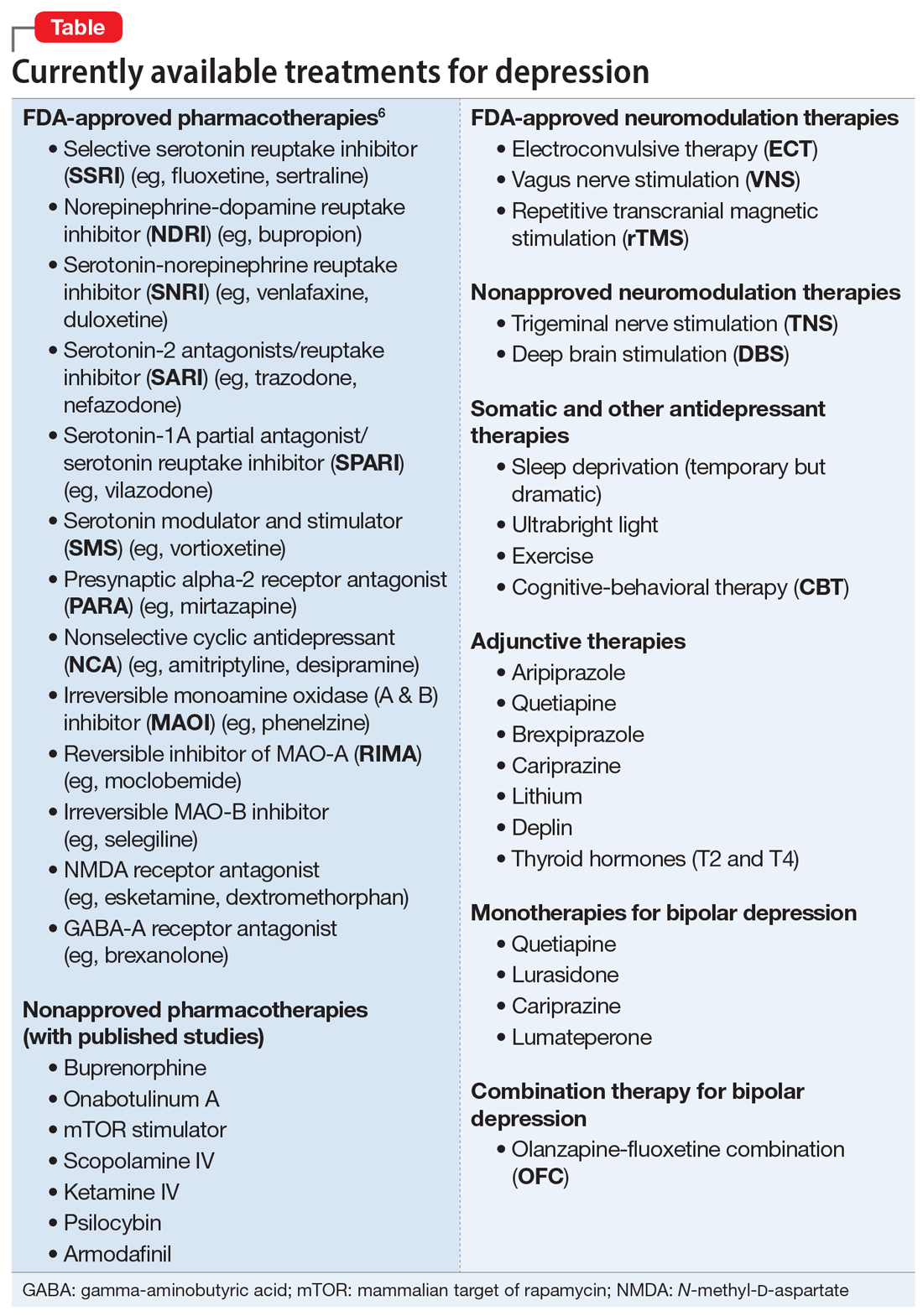

The Table6 provides an overview of the numerous treatments currently available to manage depression. All increase brain-derived neurotrophic factor and restore healthy neuroplasticity and neurogenesis, which are impaired in MDD and currently believed to be a final common pathway for all depression treatments.7

These 41 therapeutic approaches to treating MDD or bipolar depression reflect the heterogeneity of mechanisms of action to address an equally heterogeneous syndrome. This implies that clinicians have a wide array of on-label options to manage patients with depression, aiming for remission, not just a good response, which typically is defined as a ≥50% reduction in total score on one of the validated rating scales used to quantify depression severity, such as the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale, Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, or Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia.

Continue to: When several FDA-approved pharmacotherapies...

When several FDA-approved pharmacotherapies fall short and produce a suboptimal response, clinicians can resort to other treatment options known to have a higher efficacy than oral antidepressants. These include electroconvulsive therapy, repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation, and vagus nerve stimulation. Other on-label options include adjunctive therapy with one of the approved second-generation antipsychotic agents or with adjunctive esketamine.

But if the patient still does not improve, one of many emerging off-label treatment options may work. One of the exciting new discoveries is the hallucinogen psilocybin, whose mechanism of action is truly unique. Unlike standard antidepressant medications, which modulate neurotransmitters, psilocybin increases the brain’s network flexibility, decreases the modularity of several key brain networks (especially the default-brain network, or DMN), and alters the dark and distorted mental perspective of depression to a much healthier and optimistic outlook about the self and the world.8 Such novel breakthroughs in the treatment of severe depression will shed some unprecedented insights into the core neurobiology of depression, and may lead to early intervention and prevention.

As the saying goes, all roads lead to Rome. Psychiatric clinicians should rejoice that there are abundant approaches and therapeutic mechanisms to relieve their severely melancholic (and often suicidal) patients from the grips of this disabling and life-altering brain syndrome.

1. World Health Organization. Depression: let’s talk says WHO, as depression tops list of causes of ill health. March 30, 2017. Accessed July 5, 2022. www.who.int/news/item/30-03-2017--depression-let-s-talk-says-who-as-depression-tops-list-of-causes-of-ill-health

2. Trivedi MH, Fava M, Wisniewski SR, et al. Medication augmentation after the failure of SSRIs for depression. N Eng J Med. 2006;354(12)1243-1252.

3. Nasrallah HA. Treatment resistance is a myth! Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(3):14-16,28.

4. Nasrallah HA. 10 Recent paradigm shifts in the neurobiology and treatment of depression. Current Psychiatry. 2015;14(2):10-13.

5. Nasrallah HA. Biomarkers in neuropsychiatric disorders: translating research to clinical applications. Biomarkers in Neuropsychiatry. 2019;1:100001. doi:10.1016/j.bionps.2019.100001

6. Procyshyn RM, Bezchlibnyk-Butler KZ, Jeffries JJ. Clinical Handbook of Psychotropic Drugs. 23rd ed. Hogrefe; 2019.

7. Tartt AN, Mariani, MB, Hen R, et al. Dysregulation of adult hippocampal neuroplasticity in major depression: pathogenesis and therapeutic implications. Mol Psychiatry. 2022;27(6):2689-2699.

8. Lowe H, Toyang N, Steele B, et al. The therapeutic potential of psilocybin. Molecules. 2021;26(10):2948. doi: 10.3390/molecules26102948

Despite much progress, major depressive disorder (MDD) continues to be a challenging and life-threatening neuropsychiatric disorder. It is highly prevalent and afflicts tens of millions of Americans.

It is also ranked as the No. 1 disabling medical (not just psychiatric) condition by the World Health Organization.1 A significant proportion of patients with MDD do not respond adequately to several rounds of antidepressant medications,2 and many are labeled as having “treatment-resistant depression” (TRD).

In a previous article, I provocatively proposed that TRD is a myth.3 What I meant is that in a heterogeneous syndrome such as depression, failure to respond to 1, 2, or even 3 antidepressants should not imply TRD, because there is a “right treatment” that has not yet been identified for a given depressed patient. Most of those labeled as TRD have simply not yet received the pharmacotherapy or somatic therapy with the requisite mechanism of action for their variant of depression within a heterogeneous syndrome. IV ketamine, which, astonishingly, often reverses severe TRD of chronic duration within a few hours, is a prime example of why the term TRD is often used prematurely. Ketamine’s mechanism of action (immediate neuroplasticity via glutamate N-methyl-

Some clinicians may not be aware of the abundance of mechanisms of action currently available for the treatment of MDD as well as bipolar depression. Many practitioners, in both psychiatry and primary care, usually start the treatment of depression with a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, and if that does not produce a response or remission, they might switch to a serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor. If that does not control the patient’s depressive symptoms, they start entertaining the notion that the patient may have TRD, not realizing that they have barely scratched the surface of the many therapeutic options and mechanisms of action, one of which could be the “best match” for a given patient.4

There will come a day when “precision psychiatry” finally arrives, and specific biomarkers will be developed to identify the “right” treatment for each patient within the heterogenous syndrome of depression.5 Until that day arrives, the treatment of depression will continue to be a process of trial and error, and hit or miss. But research will eventually discover genetic, neurochemical, neurophysiological, neuroimaging, or neuroimmune biomarkers that will rapidly guide clinicians to the correct treatment. This is critical to avoid inordinate delays in achieving remission and avert the ever-present risk of suicidal behavior.

The Table6 provides an overview of the numerous treatments currently available to manage depression. All increase brain-derived neurotrophic factor and restore healthy neuroplasticity and neurogenesis, which are impaired in MDD and currently believed to be a final common pathway for all depression treatments.7

These 41 therapeutic approaches to treating MDD or bipolar depression reflect the heterogeneity of mechanisms of action to address an equally heterogeneous syndrome. This implies that clinicians have a wide array of on-label options to manage patients with depression, aiming for remission, not just a good response, which typically is defined as a ≥50% reduction in total score on one of the validated rating scales used to quantify depression severity, such as the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale, Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, or Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia.

Continue to: When several FDA-approved pharmacotherapies...

When several FDA-approved pharmacotherapies fall short and produce a suboptimal response, clinicians can resort to other treatment options known to have a higher efficacy than oral antidepressants. These include electroconvulsive therapy, repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation, and vagus nerve stimulation. Other on-label options include adjunctive therapy with one of the approved second-generation antipsychotic agents or with adjunctive esketamine.

But if the patient still does not improve, one of many emerging off-label treatment options may work. One of the exciting new discoveries is the hallucinogen psilocybin, whose mechanism of action is truly unique. Unlike standard antidepressant medications, which modulate neurotransmitters, psilocybin increases the brain’s network flexibility, decreases the modularity of several key brain networks (especially the default-brain network, or DMN), and alters the dark and distorted mental perspective of depression to a much healthier and optimistic outlook about the self and the world.8 Such novel breakthroughs in the treatment of severe depression will shed some unprecedented insights into the core neurobiology of depression, and may lead to early intervention and prevention.

As the saying goes, all roads lead to Rome. Psychiatric clinicians should rejoice that there are abundant approaches and therapeutic mechanisms to relieve their severely melancholic (and often suicidal) patients from the grips of this disabling and life-altering brain syndrome.

Despite much progress, major depressive disorder (MDD) continues to be a challenging and life-threatening neuropsychiatric disorder. It is highly prevalent and afflicts tens of millions of Americans.

It is also ranked as the No. 1 disabling medical (not just psychiatric) condition by the World Health Organization.1 A significant proportion of patients with MDD do not respond adequately to several rounds of antidepressant medications,2 and many are labeled as having “treatment-resistant depression” (TRD).

In a previous article, I provocatively proposed that TRD is a myth.3 What I meant is that in a heterogeneous syndrome such as depression, failure to respond to 1, 2, or even 3 antidepressants should not imply TRD, because there is a “right treatment” that has not yet been identified for a given depressed patient. Most of those labeled as TRD have simply not yet received the pharmacotherapy or somatic therapy with the requisite mechanism of action for their variant of depression within a heterogeneous syndrome. IV ketamine, which, astonishingly, often reverses severe TRD of chronic duration within a few hours, is a prime example of why the term TRD is often used prematurely. Ketamine’s mechanism of action (immediate neuroplasticity via glutamate N-methyl-

Some clinicians may not be aware of the abundance of mechanisms of action currently available for the treatment of MDD as well as bipolar depression. Many practitioners, in both psychiatry and primary care, usually start the treatment of depression with a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, and if that does not produce a response or remission, they might switch to a serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor. If that does not control the patient’s depressive symptoms, they start entertaining the notion that the patient may have TRD, not realizing that they have barely scratched the surface of the many therapeutic options and mechanisms of action, one of which could be the “best match” for a given patient.4

There will come a day when “precision psychiatry” finally arrives, and specific biomarkers will be developed to identify the “right” treatment for each patient within the heterogenous syndrome of depression.5 Until that day arrives, the treatment of depression will continue to be a process of trial and error, and hit or miss. But research will eventually discover genetic, neurochemical, neurophysiological, neuroimaging, or neuroimmune biomarkers that will rapidly guide clinicians to the correct treatment. This is critical to avoid inordinate delays in achieving remission and avert the ever-present risk of suicidal behavior.

The Table6 provides an overview of the numerous treatments currently available to manage depression. All increase brain-derived neurotrophic factor and restore healthy neuroplasticity and neurogenesis, which are impaired in MDD and currently believed to be a final common pathway for all depression treatments.7

These 41 therapeutic approaches to treating MDD or bipolar depression reflect the heterogeneity of mechanisms of action to address an equally heterogeneous syndrome. This implies that clinicians have a wide array of on-label options to manage patients with depression, aiming for remission, not just a good response, which typically is defined as a ≥50% reduction in total score on one of the validated rating scales used to quantify depression severity, such as the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale, Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, or Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia.

Continue to: When several FDA-approved pharmacotherapies...

When several FDA-approved pharmacotherapies fall short and produce a suboptimal response, clinicians can resort to other treatment options known to have a higher efficacy than oral antidepressants. These include electroconvulsive therapy, repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation, and vagus nerve stimulation. Other on-label options include adjunctive therapy with one of the approved second-generation antipsychotic agents or with adjunctive esketamine.

But if the patient still does not improve, one of many emerging off-label treatment options may work. One of the exciting new discoveries is the hallucinogen psilocybin, whose mechanism of action is truly unique. Unlike standard antidepressant medications, which modulate neurotransmitters, psilocybin increases the brain’s network flexibility, decreases the modularity of several key brain networks (especially the default-brain network, or DMN), and alters the dark and distorted mental perspective of depression to a much healthier and optimistic outlook about the self and the world.8 Such novel breakthroughs in the treatment of severe depression will shed some unprecedented insights into the core neurobiology of depression, and may lead to early intervention and prevention.

As the saying goes, all roads lead to Rome. Psychiatric clinicians should rejoice that there are abundant approaches and therapeutic mechanisms to relieve their severely melancholic (and often suicidal) patients from the grips of this disabling and life-altering brain syndrome.

1. World Health Organization. Depression: let’s talk says WHO, as depression tops list of causes of ill health. March 30, 2017. Accessed July 5, 2022. www.who.int/news/item/30-03-2017--depression-let-s-talk-says-who-as-depression-tops-list-of-causes-of-ill-health

2. Trivedi MH, Fava M, Wisniewski SR, et al. Medication augmentation after the failure of SSRIs for depression. N Eng J Med. 2006;354(12)1243-1252.

3. Nasrallah HA. Treatment resistance is a myth! Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(3):14-16,28.

4. Nasrallah HA. 10 Recent paradigm shifts in the neurobiology and treatment of depression. Current Psychiatry. 2015;14(2):10-13.

5. Nasrallah HA. Biomarkers in neuropsychiatric disorders: translating research to clinical applications. Biomarkers in Neuropsychiatry. 2019;1:100001. doi:10.1016/j.bionps.2019.100001

6. Procyshyn RM, Bezchlibnyk-Butler KZ, Jeffries JJ. Clinical Handbook of Psychotropic Drugs. 23rd ed. Hogrefe; 2019.

7. Tartt AN, Mariani, MB, Hen R, et al. Dysregulation of adult hippocampal neuroplasticity in major depression: pathogenesis and therapeutic implications. Mol Psychiatry. 2022;27(6):2689-2699.

8. Lowe H, Toyang N, Steele B, et al. The therapeutic potential of psilocybin. Molecules. 2021;26(10):2948. doi: 10.3390/molecules26102948

1. World Health Organization. Depression: let’s talk says WHO, as depression tops list of causes of ill health. March 30, 2017. Accessed July 5, 2022. www.who.int/news/item/30-03-2017--depression-let-s-talk-says-who-as-depression-tops-list-of-causes-of-ill-health

2. Trivedi MH, Fava M, Wisniewski SR, et al. Medication augmentation after the failure of SSRIs for depression. N Eng J Med. 2006;354(12)1243-1252.

3. Nasrallah HA. Treatment resistance is a myth! Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(3):14-16,28.

4. Nasrallah HA. 10 Recent paradigm shifts in the neurobiology and treatment of depression. Current Psychiatry. 2015;14(2):10-13.

5. Nasrallah HA. Biomarkers in neuropsychiatric disorders: translating research to clinical applications. Biomarkers in Neuropsychiatry. 2019;1:100001. doi:10.1016/j.bionps.2019.100001

6. Procyshyn RM, Bezchlibnyk-Butler KZ, Jeffries JJ. Clinical Handbook of Psychotropic Drugs. 23rd ed. Hogrefe; 2019.

7. Tartt AN, Mariani, MB, Hen R, et al. Dysregulation of adult hippocampal neuroplasticity in major depression: pathogenesis and therapeutic implications. Mol Psychiatry. 2022;27(6):2689-2699.

8. Lowe H, Toyang N, Steele B, et al. The therapeutic potential of psilocybin. Molecules. 2021;26(10):2948. doi: 10.3390/molecules26102948

3 steps to bend the curve of schizophrenia

Schizophrenia is arguably the most serious psychiatric brain syndrome. It disables teens and young adults and robs them of their potential and life dreams. It is widely regarded as a hopeless illness.

But it does not have to be. The reason most patients with schizophrenia do not return to their baseline is because obsolete clinical management approaches, a carryover from the last century, continue to be used.

Approximately 20 years ago, psychiatric researchers made a major discovery: psychosis is a neurotoxic state, and each psychotic episode is associated with significant brain damage in both gray and white matter.1 Based on that discovery, a more rational management of schizophrenia has emerged, focused on protecting patients from experiencing psychotic recurrence after the first-episode psychosis (FEP). In the past century, this strategy did not exist because psychiatrists were in a state of scientific ignorance, completely unaware that the malignant component of schizophrenia that leads to disability is psychotic relapses, the primary cause of which is very poor medication adherence after hospital discharge following the FEP.

Based on the emerging scientific evidence, here are 3 essential principles to halt the deterioration and bend the curve of outcomes in schizophrenia:

1. Minimize the duration of untreated psychosis (DUP)

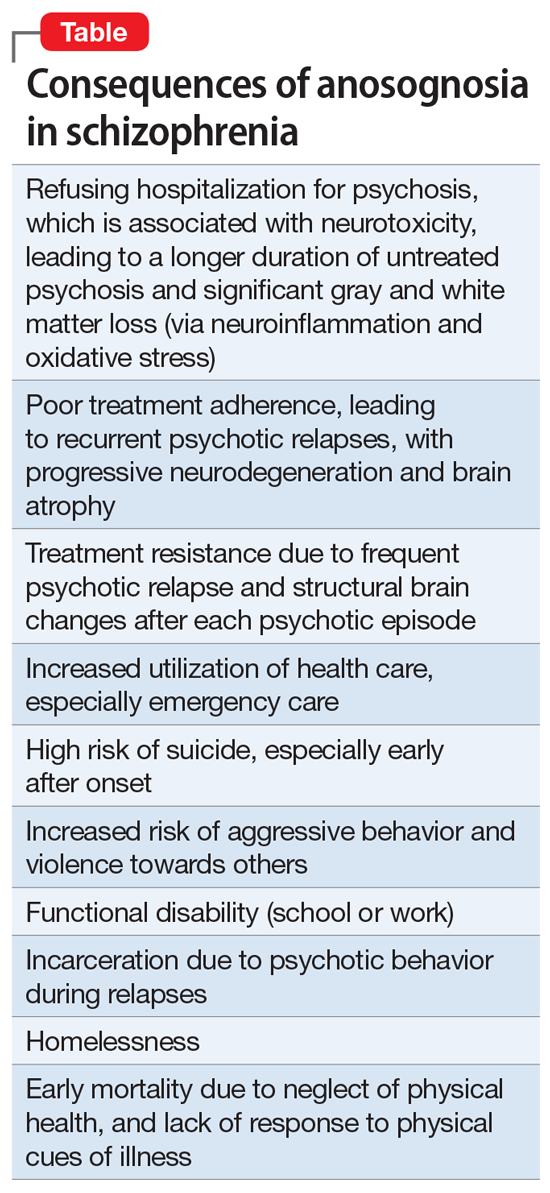

Numerous studies have shown that the longer the DUP, the worse the outcome in schizophrenia.2,3 It is therefore vital to shorten the DUP spanning the emergence of psychotic symptoms at home, prior to the first hospital admission.4 The DUP is often prolonged from weeks to months by a combination of anosognosia by the patient, who fails to recognize how pathological their hallucinations and delusions are, plus the stigma of mental illness, which leads parents to delay bringing their son or daughter for psychiatric evaluation and treatment.

Another reason for a prolonged DUP is the legal system’s governing of the initiation of antipsychotic medications for an acutely psychotic patient who does not believe he/she is sick, and who adamantly refuses to receive medications. Laws passed decades ago have not kept up with scientific advances about brain damage during the DUP. Instead of delegating the rapid administration of an antipsychotic medication to the psychiatric physician who evaluated and diagnosed a patient with acute psychosis, the legal system further prolongs the DUP by requiring the psychiatrist to go to court and have a judge order the administration of antipsychotic medications. Such a legal requirement that delays urgently needed treatment has never been imposed on neurologists when administering medication to an obtunded stroke patient. Yet psychosis damages brain tissue and must be treated as urgently as stroke.5

Perhaps the most common reason for a long DUP is the recurrent relapses of psychosis, almost always caused by the high nonadherence rate among patients with schizophrenia due to multiple factors related to the illness itself.6 Ensuring uninterrupted delivery of an antipsychotic to a patient’s brain is as important to maintaining remission in schizophrenia as uninterrupted insulin treatment is for an individual with diabetes. The only way to guarantee ongoing daily pharmacotherapy in schizophrenia and avoid a longer DUP and more brain damage is to use long-acting injectable (LAI) formulations of antipsychotic medications, which are infrequently used despite making eminent sense to protect patients from the tragic consequences of psychotic relapse.7

Continue to: Start very early use of LAIs

2. Start very early use of LAIs

There is no doubt that switching from an oral to an LAI antipsychotic immediately after hospital discharge for the FEP is the single most important medical decision psychiatrists can make for patients with schizophrenia.8 This is because disability in schizophrenia begins after the second episode, not the first.9-11 Therefore, psychiatrists must behave like cardiologists,12 who strive to prevent a second destructive myocardial infarction. Regrettably, 99.9% of psychiatric practitioners never start an LAI after the FEP, and usually wait until the patient experiences multiple relapses, after extensive gray matter atrophy and white matter disintegration have occurred due to the neuroinflammation and oxidative stress (free radicals) that occur with every psychotic episode.13,14 This clearly does not make clinical sense, but remains the standard current practice.

In oncology, chemotherapy is far more effective in Stage 1 cancer, immediately after the diagnosis is made, rather than in Stage 4, when the prognosis is very poor. Similarly, LAIs are best used in Stage 1 schizophrenia, which is the first episode (schizophrenia researchers now regard the illness as having stages).15 Unfortunately, it is now rare for patients with schizophrenia to be switched to LAI pharmacotherapy right after recovery from the FEP. Instead, LAIs are more commonly used in Stage 3 or Stage 4, when the brains of patients with chronic schizophrenia have been already structurally damaged, and functional disability had set in. Bending the cure of outcome in schizophrenia is only possible when LAIs are used very early to prevent the second episode.

The prevention of relapse by using LAIs in FEP is truly remarkable. Subotnik et al16 reported that only 5% of FEP patients who received an LAI antipsychotic relapsed, compared to 33% of those who received an oral formulation of the same antipsychotic (a 650% difference). It is frankly inexplicable why psychiatrists do not exploit the relapse-preventing properties of LAIs at the time of discharge after the FEP, and instead continue to perpetuate the use of prescribing oral tablets to patients who are incapable of full adherence and doomed to “self-destruct.” This was the practice model in the previous century, when there was total ignorance about the brain-damaging effects of psychosis, and no sense of urgency about preventing psychotic relapses and DUP. Psychiatrists regarded LAIs as a last resort instead of a life-saving first resort.

In addition to relapse prevention,17 the benefits of second-generation LAIs include neuroprotection18 and lower all-cause mortality,19 a remarkable triad of benefits for patients with schizophrenia.20

3. Implement comprehensive psychosocial treatment

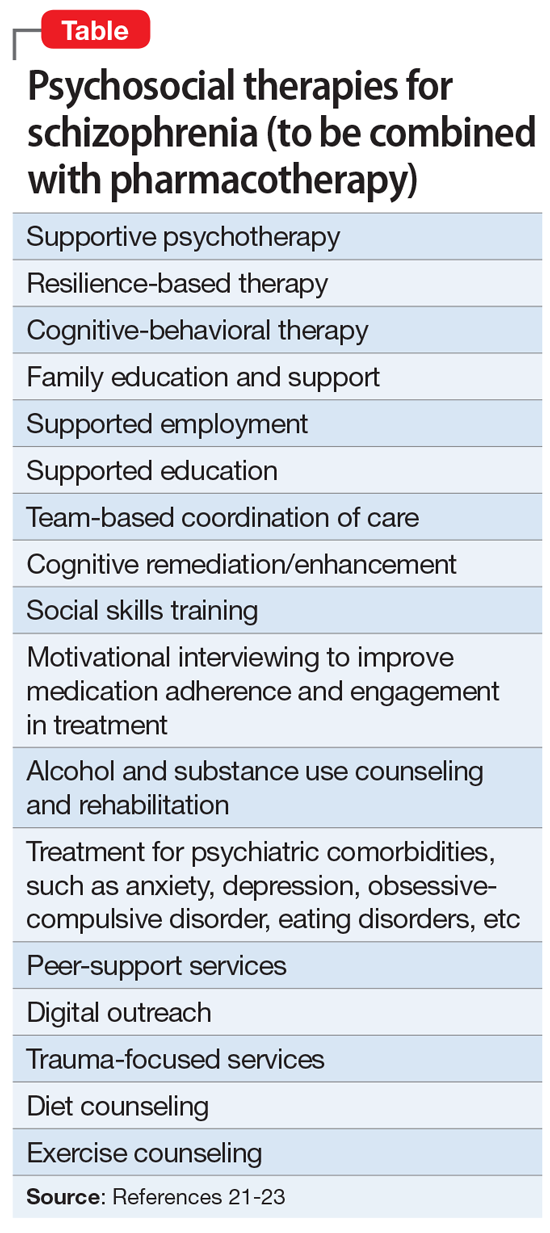

Most patients with schizophrenia do not have access to the array of psychosocial treatments that have been shown to be vital for rehabilitation following the FEP, just as physical rehabilitation is indispensable after the first stroke. Studies such as RAISE,21 which was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health, have demonstrated the value of psychosocial therapies (Table21-23). Collaborative care with primary care physicians is also essential due to the high prevalence of metabolic disorders (obesity, diabetics, dyslipidemia, hypertension), which tend to be undertreated in patients with schizophrenia.24

Finally, when patients continue to experience delusions and hallucinations despite full adherence (with LAIs), clozapine must be used. Like LAIs, clozapine is woefully underutilized25 despite having been shown to restore mental health and full recovery to many (but not all) patients written off as hopeless due to persistent and refractory psychotic symptoms.26

If clinicians who treat schizophrenia implement these 3 steps in their FEP patients, they will be gratified to witness a more benign trajectory of schizophrenia, which I have personally seen. The curve can indeed be bent in favor of better outcomes. By using the 3 evidence-based steps described here, clinicians will realize that schizophrenia does not have to carry the label of “the worst disease affecting mankind,” as an editorial in a top-tier journal pessimistically stated over 3 decades ago.27

1. Cahn W, Hulshoff Pol HE, Lems EB, et al. Brain volume changes in first-episode schizophrenia: a 1-year follow-up study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59(11):1002-1010.

2. Howes OD, Whitehurst T, Shatalina E, et al. The clinical significance of duration of untreated psychosis: an umbrella review and random-effects meta-analysis. World Psychiatry. 2021;20(1):75-95.

3. Oliver D, Davies C, Crossland G, et al. Can we reduce the duration of untreated psychosis? A systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled interventional studies. Schizophr Bull. 2018;44(6):1362-1372.

4. Srihari VH, Ferrara M, Li F, et al. Reducing the duration of untreated psychosis (DUP) in a US community: a quasi-experimental trial. Schizophr Bull Open. 2022;3(1):sgab057. doi:10.1093/schizbullopen/sgab057

5. Nasrallah HA, Roque A. FAST and RAPID: acronyms to prevent brain damage in stroke and psychosis. Current Psychiatry. 2018;17(8):6-8.

6. Lieslehto J, Tiihonen J, Lähteenvuo M, et al. Primary nonadherence to antipsychotic treatment among persons with schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2022;48(3):665-663.

7. Nasrallah HA. 10 devastating consequences of psychotic relapses. Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(5):9-12.

8. Emsley R, Oosthuizen P, Koen L, et al. Remission in patients with first-episode schizophrenia receiving assured antipsychotic medication: a study with risperidone long-acting injection. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;23(6):325-331.

9. Alvarez-Jiménez M, Parker AG, Hetrick SE, et al. Preventing the second episode: a systematic review and meta-analysis of psychosocial and pharmacological trials in first-episode psychosis. Schizophr Bull. 2011;37(3):619-630.

10. Taipale H, Tanskanen A, Correll CU, et al. Real-world effectiveness of antipsychotic doses for relapse prevention in patients with first-episode schizophrenia in Finland: a nationwide, register-based cohort study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2022;9(4):271-279.

11. Gardner KN, Nasrallah HA. Managing first-episode psychosis: rationale and evidence for nonstandard first-line treatments for schizophrenia. Current Psychiatry. 2015;14(7):38-45,e3.

12. Nasrallah HA. For first-episode psychosis, psychiatrists should behave like cardiologists. Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(8):4-7.

13. Feigenson KA, Kusnecov AW, Silverstein SM. Inflammation and the two-hit hypothesis of schizophrenia. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2014;38:72-93.

14. Flatow J, Buckley P, Miller BJ. Meta-analysis of oxidative stress in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;74(6):400-409.

15. Lavoie S, Polari AR, Goldstone S, et al. Staging model in psychiatry: review of the evolution of electroencephalography abnormalities in major psychiatric disorders. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2019;13(6):1319-1328.

16. Subotnik KL, Casaus LR, Ventura J, et al. Long-acting injectable risperidone for relapse prevention and control of breakthrough symptoms after a recent first episode of schizophrenia. A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(8):822-829.

17. Lin YH, Wu CS, Liu CC, et al. Comparative effectiveness of antipsychotics in preventing readmission for first-admission schizophrenia patients in national cohorts from 2001 to 2017 in Taiwan. Schizophr Bull. 2022;sbac046. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbac046

18. Chen AT, Nasrallah HA. Neuroprotective effects of the second generation antipsychotics. Schizophr Res. 2019;208:1-7.

19. Taipale H, Mittendorfer-Rutz E, Alexanderson K, et al. Antipsychotics and mortality in a nationwide cohort of 29,823 patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2018;197:274-280.

20. Nasrallah HA. Triple advantages of injectable long acting second generation antipsychotics: relapse prevention, neuroprotection, and lower mortality. Schizophr Res. 2018;197:69-70.

21. Kane JM, Robinson DG, Schooler NR, et al. Comprehensive versus usual community care for first-episode psychosis: 2-year outcomes from the NIMH RAISE Early Treatment Program. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(4):362-372.

22. Keshavan MS, Ongur D, Srihari VH. Toward an expanded and personalized approach to coordinated specialty care in early course psychoses. Schizophr Res. 2022;241:119-121.

23. Srihari VH, Keshavan MS. Early intervention services for schizophrenia: looking back and looking ahead. Schizophr Bull. 2022;48(3):544-550.

24. Nasrallah HA, Meyer JM, Goff DC, et al. Low rates of treatment for hypertension, dyslipidemia and diabetes in schizophrenia: data from the CATIE schizophrenia trial sample at baseline. Schizophr Res. 2006;86(1-3):15-22.

25. Nasrallah HA. Clozapine is a vastly underutilized, unique agent with multiple applications. Current Psychiatry. 2014;13(10):21,24-25.

26. CureSZ Foundation. Clozapine success stories. Accessed June 1, 2022. https://curesz.org/clozapine-success-stories/

27. Where next with psychiatric illness? Nature. 1988;336(6195):95-96.

Schizophrenia is arguably the most serious psychiatric brain syndrome. It disables teens and young adults and robs them of their potential and life dreams. It is widely regarded as a hopeless illness.

But it does not have to be. The reason most patients with schizophrenia do not return to their baseline is because obsolete clinical management approaches, a carryover from the last century, continue to be used.

Approximately 20 years ago, psychiatric researchers made a major discovery: psychosis is a neurotoxic state, and each psychotic episode is associated with significant brain damage in both gray and white matter.1 Based on that discovery, a more rational management of schizophrenia has emerged, focused on protecting patients from experiencing psychotic recurrence after the first-episode psychosis (FEP). In the past century, this strategy did not exist because psychiatrists were in a state of scientific ignorance, completely unaware that the malignant component of schizophrenia that leads to disability is psychotic relapses, the primary cause of which is very poor medication adherence after hospital discharge following the FEP.

Based on the emerging scientific evidence, here are 3 essential principles to halt the deterioration and bend the curve of outcomes in schizophrenia:

1. Minimize the duration of untreated psychosis (DUP)

Numerous studies have shown that the longer the DUP, the worse the outcome in schizophrenia.2,3 It is therefore vital to shorten the DUP spanning the emergence of psychotic symptoms at home, prior to the first hospital admission.4 The DUP is often prolonged from weeks to months by a combination of anosognosia by the patient, who fails to recognize how pathological their hallucinations and delusions are, plus the stigma of mental illness, which leads parents to delay bringing their son or daughter for psychiatric evaluation and treatment.

Another reason for a prolonged DUP is the legal system’s governing of the initiation of antipsychotic medications for an acutely psychotic patient who does not believe he/she is sick, and who adamantly refuses to receive medications. Laws passed decades ago have not kept up with scientific advances about brain damage during the DUP. Instead of delegating the rapid administration of an antipsychotic medication to the psychiatric physician who evaluated and diagnosed a patient with acute psychosis, the legal system further prolongs the DUP by requiring the psychiatrist to go to court and have a judge order the administration of antipsychotic medications. Such a legal requirement that delays urgently needed treatment has never been imposed on neurologists when administering medication to an obtunded stroke patient. Yet psychosis damages brain tissue and must be treated as urgently as stroke.5

Perhaps the most common reason for a long DUP is the recurrent relapses of psychosis, almost always caused by the high nonadherence rate among patients with schizophrenia due to multiple factors related to the illness itself.6 Ensuring uninterrupted delivery of an antipsychotic to a patient’s brain is as important to maintaining remission in schizophrenia as uninterrupted insulin treatment is for an individual with diabetes. The only way to guarantee ongoing daily pharmacotherapy in schizophrenia and avoid a longer DUP and more brain damage is to use long-acting injectable (LAI) formulations of antipsychotic medications, which are infrequently used despite making eminent sense to protect patients from the tragic consequences of psychotic relapse.7

Continue to: Start very early use of LAIs

2. Start very early use of LAIs

There is no doubt that switching from an oral to an LAI antipsychotic immediately after hospital discharge for the FEP is the single most important medical decision psychiatrists can make for patients with schizophrenia.8 This is because disability in schizophrenia begins after the second episode, not the first.9-11 Therefore, psychiatrists must behave like cardiologists,12 who strive to prevent a second destructive myocardial infarction. Regrettably, 99.9% of psychiatric practitioners never start an LAI after the FEP, and usually wait until the patient experiences multiple relapses, after extensive gray matter atrophy and white matter disintegration have occurred due to the neuroinflammation and oxidative stress (free radicals) that occur with every psychotic episode.13,14 This clearly does not make clinical sense, but remains the standard current practice.

In oncology, chemotherapy is far more effective in Stage 1 cancer, immediately after the diagnosis is made, rather than in Stage 4, when the prognosis is very poor. Similarly, LAIs are best used in Stage 1 schizophrenia, which is the first episode (schizophrenia researchers now regard the illness as having stages).15 Unfortunately, it is now rare for patients with schizophrenia to be switched to LAI pharmacotherapy right after recovery from the FEP. Instead, LAIs are more commonly used in Stage 3 or Stage 4, when the brains of patients with chronic schizophrenia have been already structurally damaged, and functional disability had set in. Bending the cure of outcome in schizophrenia is only possible when LAIs are used very early to prevent the second episode.

The prevention of relapse by using LAIs in FEP is truly remarkable. Subotnik et al16 reported that only 5% of FEP patients who received an LAI antipsychotic relapsed, compared to 33% of those who received an oral formulation of the same antipsychotic (a 650% difference). It is frankly inexplicable why psychiatrists do not exploit the relapse-preventing properties of LAIs at the time of discharge after the FEP, and instead continue to perpetuate the use of prescribing oral tablets to patients who are incapable of full adherence and doomed to “self-destruct.” This was the practice model in the previous century, when there was total ignorance about the brain-damaging effects of psychosis, and no sense of urgency about preventing psychotic relapses and DUP. Psychiatrists regarded LAIs as a last resort instead of a life-saving first resort.

In addition to relapse prevention,17 the benefits of second-generation LAIs include neuroprotection18 and lower all-cause mortality,19 a remarkable triad of benefits for patients with schizophrenia.20

3. Implement comprehensive psychosocial treatment

Most patients with schizophrenia do not have access to the array of psychosocial treatments that have been shown to be vital for rehabilitation following the FEP, just as physical rehabilitation is indispensable after the first stroke. Studies such as RAISE,21 which was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health, have demonstrated the value of psychosocial therapies (Table21-23). Collaborative care with primary care physicians is also essential due to the high prevalence of metabolic disorders (obesity, diabetics, dyslipidemia, hypertension), which tend to be undertreated in patients with schizophrenia.24

Finally, when patients continue to experience delusions and hallucinations despite full adherence (with LAIs), clozapine must be used. Like LAIs, clozapine is woefully underutilized25 despite having been shown to restore mental health and full recovery to many (but not all) patients written off as hopeless due to persistent and refractory psychotic symptoms.26

If clinicians who treat schizophrenia implement these 3 steps in their FEP patients, they will be gratified to witness a more benign trajectory of schizophrenia, which I have personally seen. The curve can indeed be bent in favor of better outcomes. By using the 3 evidence-based steps described here, clinicians will realize that schizophrenia does not have to carry the label of “the worst disease affecting mankind,” as an editorial in a top-tier journal pessimistically stated over 3 decades ago.27

Schizophrenia is arguably the most serious psychiatric brain syndrome. It disables teens and young adults and robs them of their potential and life dreams. It is widely regarded as a hopeless illness.

But it does not have to be. The reason most patients with schizophrenia do not return to their baseline is because obsolete clinical management approaches, a carryover from the last century, continue to be used.

Approximately 20 years ago, psychiatric researchers made a major discovery: psychosis is a neurotoxic state, and each psychotic episode is associated with significant brain damage in both gray and white matter.1 Based on that discovery, a more rational management of schizophrenia has emerged, focused on protecting patients from experiencing psychotic recurrence after the first-episode psychosis (FEP). In the past century, this strategy did not exist because psychiatrists were in a state of scientific ignorance, completely unaware that the malignant component of schizophrenia that leads to disability is psychotic relapses, the primary cause of which is very poor medication adherence after hospital discharge following the FEP.

Based on the emerging scientific evidence, here are 3 essential principles to halt the deterioration and bend the curve of outcomes in schizophrenia:

1. Minimize the duration of untreated psychosis (DUP)

Numerous studies have shown that the longer the DUP, the worse the outcome in schizophrenia.2,3 It is therefore vital to shorten the DUP spanning the emergence of psychotic symptoms at home, prior to the first hospital admission.4 The DUP is often prolonged from weeks to months by a combination of anosognosia by the patient, who fails to recognize how pathological their hallucinations and delusions are, plus the stigma of mental illness, which leads parents to delay bringing their son or daughter for psychiatric evaluation and treatment.

Another reason for a prolonged DUP is the legal system’s governing of the initiation of antipsychotic medications for an acutely psychotic patient who does not believe he/she is sick, and who adamantly refuses to receive medications. Laws passed decades ago have not kept up with scientific advances about brain damage during the DUP. Instead of delegating the rapid administration of an antipsychotic medication to the psychiatric physician who evaluated and diagnosed a patient with acute psychosis, the legal system further prolongs the DUP by requiring the psychiatrist to go to court and have a judge order the administration of antipsychotic medications. Such a legal requirement that delays urgently needed treatment has never been imposed on neurologists when administering medication to an obtunded stroke patient. Yet psychosis damages brain tissue and must be treated as urgently as stroke.5

Perhaps the most common reason for a long DUP is the recurrent relapses of psychosis, almost always caused by the high nonadherence rate among patients with schizophrenia due to multiple factors related to the illness itself.6 Ensuring uninterrupted delivery of an antipsychotic to a patient’s brain is as important to maintaining remission in schizophrenia as uninterrupted insulin treatment is for an individual with diabetes. The only way to guarantee ongoing daily pharmacotherapy in schizophrenia and avoid a longer DUP and more brain damage is to use long-acting injectable (LAI) formulations of antipsychotic medications, which are infrequently used despite making eminent sense to protect patients from the tragic consequences of psychotic relapse.7

Continue to: Start very early use of LAIs

2. Start very early use of LAIs

There is no doubt that switching from an oral to an LAI antipsychotic immediately after hospital discharge for the FEP is the single most important medical decision psychiatrists can make for patients with schizophrenia.8 This is because disability in schizophrenia begins after the second episode, not the first.9-11 Therefore, psychiatrists must behave like cardiologists,12 who strive to prevent a second destructive myocardial infarction. Regrettably, 99.9% of psychiatric practitioners never start an LAI after the FEP, and usually wait until the patient experiences multiple relapses, after extensive gray matter atrophy and white matter disintegration have occurred due to the neuroinflammation and oxidative stress (free radicals) that occur with every psychotic episode.13,14 This clearly does not make clinical sense, but remains the standard current practice.

In oncology, chemotherapy is far more effective in Stage 1 cancer, immediately after the diagnosis is made, rather than in Stage 4, when the prognosis is very poor. Similarly, LAIs are best used in Stage 1 schizophrenia, which is the first episode (schizophrenia researchers now regard the illness as having stages).15 Unfortunately, it is now rare for patients with schizophrenia to be switched to LAI pharmacotherapy right after recovery from the FEP. Instead, LAIs are more commonly used in Stage 3 or Stage 4, when the brains of patients with chronic schizophrenia have been already structurally damaged, and functional disability had set in. Bending the cure of outcome in schizophrenia is only possible when LAIs are used very early to prevent the second episode.

The prevention of relapse by using LAIs in FEP is truly remarkable. Subotnik et al16 reported that only 5% of FEP patients who received an LAI antipsychotic relapsed, compared to 33% of those who received an oral formulation of the same antipsychotic (a 650% difference). It is frankly inexplicable why psychiatrists do not exploit the relapse-preventing properties of LAIs at the time of discharge after the FEP, and instead continue to perpetuate the use of prescribing oral tablets to patients who are incapable of full adherence and doomed to “self-destruct.” This was the practice model in the previous century, when there was total ignorance about the brain-damaging effects of psychosis, and no sense of urgency about preventing psychotic relapses and DUP. Psychiatrists regarded LAIs as a last resort instead of a life-saving first resort.

In addition to relapse prevention,17 the benefits of second-generation LAIs include neuroprotection18 and lower all-cause mortality,19 a remarkable triad of benefits for patients with schizophrenia.20

3. Implement comprehensive psychosocial treatment

Most patients with schizophrenia do not have access to the array of psychosocial treatments that have been shown to be vital for rehabilitation following the FEP, just as physical rehabilitation is indispensable after the first stroke. Studies such as RAISE,21 which was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health, have demonstrated the value of psychosocial therapies (Table21-23). Collaborative care with primary care physicians is also essential due to the high prevalence of metabolic disorders (obesity, diabetics, dyslipidemia, hypertension), which tend to be undertreated in patients with schizophrenia.24

Finally, when patients continue to experience delusions and hallucinations despite full adherence (with LAIs), clozapine must be used. Like LAIs, clozapine is woefully underutilized25 despite having been shown to restore mental health and full recovery to many (but not all) patients written off as hopeless due to persistent and refractory psychotic symptoms.26

If clinicians who treat schizophrenia implement these 3 steps in their FEP patients, they will be gratified to witness a more benign trajectory of schizophrenia, which I have personally seen. The curve can indeed be bent in favor of better outcomes. By using the 3 evidence-based steps described here, clinicians will realize that schizophrenia does not have to carry the label of “the worst disease affecting mankind,” as an editorial in a top-tier journal pessimistically stated over 3 decades ago.27

1. Cahn W, Hulshoff Pol HE, Lems EB, et al. Brain volume changes in first-episode schizophrenia: a 1-year follow-up study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59(11):1002-1010.

2. Howes OD, Whitehurst T, Shatalina E, et al. The clinical significance of duration of untreated psychosis: an umbrella review and random-effects meta-analysis. World Psychiatry. 2021;20(1):75-95.

3. Oliver D, Davies C, Crossland G, et al. Can we reduce the duration of untreated psychosis? A systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled interventional studies. Schizophr Bull. 2018;44(6):1362-1372.

4. Srihari VH, Ferrara M, Li F, et al. Reducing the duration of untreated psychosis (DUP) in a US community: a quasi-experimental trial. Schizophr Bull Open. 2022;3(1):sgab057. doi:10.1093/schizbullopen/sgab057

5. Nasrallah HA, Roque A. FAST and RAPID: acronyms to prevent brain damage in stroke and psychosis. Current Psychiatry. 2018;17(8):6-8.

6. Lieslehto J, Tiihonen J, Lähteenvuo M, et al. Primary nonadherence to antipsychotic treatment among persons with schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2022;48(3):665-663.

7. Nasrallah HA. 10 devastating consequences of psychotic relapses. Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(5):9-12.

8. Emsley R, Oosthuizen P, Koen L, et al. Remission in patients with first-episode schizophrenia receiving assured antipsychotic medication: a study with risperidone long-acting injection. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;23(6):325-331.

9. Alvarez-Jiménez M, Parker AG, Hetrick SE, et al. Preventing the second episode: a systematic review and meta-analysis of psychosocial and pharmacological trials in first-episode psychosis. Schizophr Bull. 2011;37(3):619-630.

10. Taipale H, Tanskanen A, Correll CU, et al. Real-world effectiveness of antipsychotic doses for relapse prevention in patients with first-episode schizophrenia in Finland: a nationwide, register-based cohort study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2022;9(4):271-279.