User login

Acute Generalized Exanthematous Pustulosis Induced by the Second-Generation Antipsychotic Cariprazine

To the Editor:

A 57-year-old woman presented to an outpatient clinic with severe pruritus and burning of the skin as well as subjective fevers and chills. She had been discharged from a psychiatric hospital for attempted suicide 1 day prior. There were no recent changes in the medication regimen, which consisted of linaclotide, fluoxetine, lorazepam, and gabapentin. While admitted, the patient was started on the atypical antipsychotic cariprazine. Within 24 hours of the first dose, she developed severe facial erythema that progressed to diffuse erythema over more than 60% of the body surface area. The attending psychiatrist promptly discontinued cariprazine. During the next 24 hours, there were no reports of fever, leukocytosis, or signs of systemic organ involvement. Given the patient’s mental and medical stability, she was discharged with instructions to follow up with the outpatient dermatology clinic.

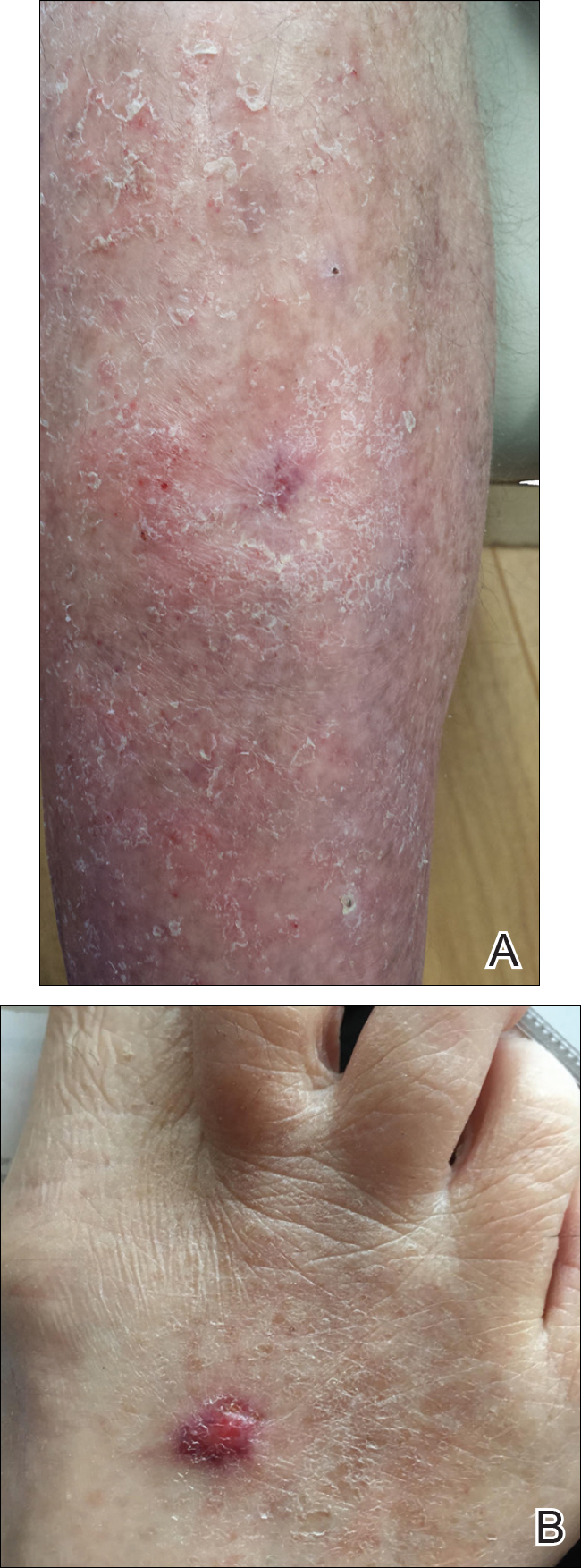

At the current presentation, physical examination revealed innumerable 1- to 4-mm pustules coalescing to lakes of pus on an erythematous base over more than 60% of the body surface area (Figure 1). The mucous membranes were clear of lesions, the Nikolsky sign was negative, and the patient’s temperature was 99.6 °F in the office. Complete blood cell count and complete metabolic panel results were within reference range.

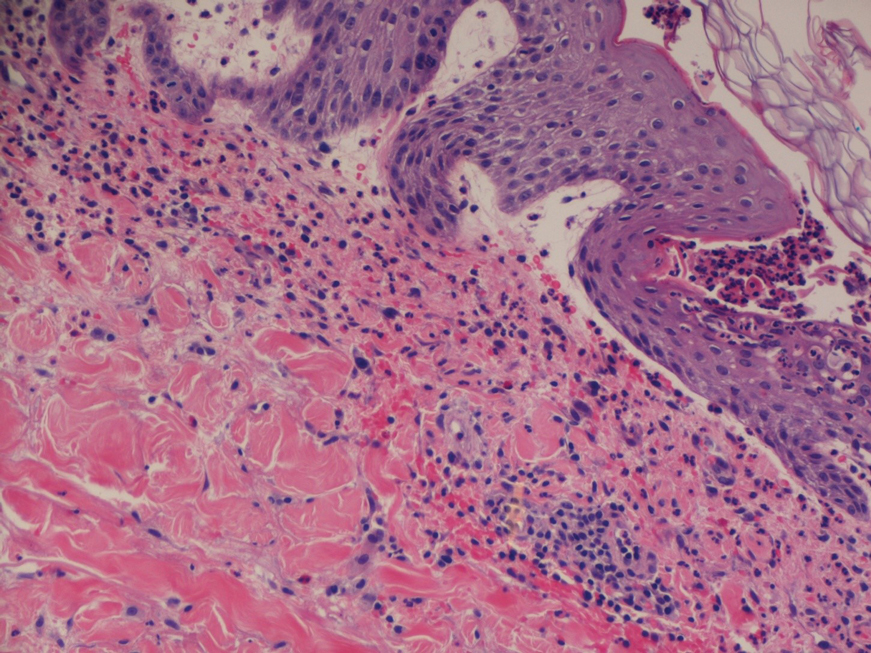

A 4-mm abdominal punch biopsy showed subcorneal neutrophilic pustules, papillary dermal edema, and superficial dermal lymphohistiocytic inflammation with numerous neutrophils, eosinophils, and extravasated red blood cells, consistent with acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP)(Figure 2). The patient was started on wet wraps with triamcinolone cream 0.1%.

Two days later, physical examination revealed the erythema noted on initial examination had notably decreased, and the patient no longer reported burning or pruritus. One week after initial presentation to the clinic, the patient’s rash had resolved, and only a few small areas of desquamation remained.

Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis is a severe cutaneous adverse reaction characterized by the development of numerous nonfollicular sterile pustules on an edematous and erythematous base. In almost 90% of reported cases, the cause is related to use of antibiotics, antifungals, antimalarials, or diltiazem (a calcium channel blocker). This rare cutaneous reaction occurs in 1 to 5 patients per million per year1; it carries a 1% to 2% mortality rate with proper supportive treatment.

The clinical symptoms of AGEP typically present 24 to 48 hours after drug initiation with the rapid development of dozens to thousands of 1- to 4-mm pustules, typically localized to the flexor surfaces and face. In the setting of AGEP, acute onset of fever and leukocytosis typically occur at the time of the cutaneous eruption. These features were absent in this patient. The eruption usually starts on the face and then migrates to the trunk and extremities, sparing the palms and soles. Systemic involvement most commonly presents as hepatic, renal, or pulmonary insufficiency, which has been seen in 20% of cases.2

The immunologic response associated with the reaction has been studied in vitro. Drug-specific CD8 T cells use perforin/granzyme B and Fas ligand mechanisms to induce apoptosis of the keratinocytes within the epidermis, leading to vesicle formation.3 During the very first stages of formation, vesicles mainly comprise CD8 T cells and keratinocytes. These cells then begin producing CXC-18, a potent neutrophil chemokine, leading to extensive chemotaxis of neutrophils into vesicles, which then rapidly transform to pustules.3 This rapid transformation leads to the lakes of pustules, a description often associated with AGEP.

Treatment of AGEP is mainly supportive and consists of discontinuing use of the causative agent. Topical corticosteroids can be used during the pustular phase for symptom management. There is no evidence that systemic steroids reduce the duration of the disease.2 Other supportive measures such as application of wet wraps can be used to provide comfort.

Cutaneous adverse drug reactions commonly are associated with psychiatric pharmacotherapy, but first-and second-generation antipsychotics rarely are associated with these types of reactions. In this patient, the causative agent of the AGEP was cariprazine, an atypical antipsychotic that had no reported association with AGEP or cutaneous adverse drug reactions prior to this presentation.

- Fernando SL. Acute generalised exanthematous pustulosis. Australas J Dermatol. 2012;53:87-92.

- Feldmeyer L, Heidemeyer K, Yawalkar N. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis: pathogenesis, genetic background, clinical variants and therapy. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17:1214.

- Szatkowski J, Schwartz RA. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP): a review and update. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:843-848.

To the Editor:

A 57-year-old woman presented to an outpatient clinic with severe pruritus and burning of the skin as well as subjective fevers and chills. She had been discharged from a psychiatric hospital for attempted suicide 1 day prior. There were no recent changes in the medication regimen, which consisted of linaclotide, fluoxetine, lorazepam, and gabapentin. While admitted, the patient was started on the atypical antipsychotic cariprazine. Within 24 hours of the first dose, she developed severe facial erythema that progressed to diffuse erythema over more than 60% of the body surface area. The attending psychiatrist promptly discontinued cariprazine. During the next 24 hours, there were no reports of fever, leukocytosis, or signs of systemic organ involvement. Given the patient’s mental and medical stability, she was discharged with instructions to follow up with the outpatient dermatology clinic.

At the current presentation, physical examination revealed innumerable 1- to 4-mm pustules coalescing to lakes of pus on an erythematous base over more than 60% of the body surface area (Figure 1). The mucous membranes were clear of lesions, the Nikolsky sign was negative, and the patient’s temperature was 99.6 °F in the office. Complete blood cell count and complete metabolic panel results were within reference range.

A 4-mm abdominal punch biopsy showed subcorneal neutrophilic pustules, papillary dermal edema, and superficial dermal lymphohistiocytic inflammation with numerous neutrophils, eosinophils, and extravasated red blood cells, consistent with acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP)(Figure 2). The patient was started on wet wraps with triamcinolone cream 0.1%.

Two days later, physical examination revealed the erythema noted on initial examination had notably decreased, and the patient no longer reported burning or pruritus. One week after initial presentation to the clinic, the patient’s rash had resolved, and only a few small areas of desquamation remained.

Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis is a severe cutaneous adverse reaction characterized by the development of numerous nonfollicular sterile pustules on an edematous and erythematous base. In almost 90% of reported cases, the cause is related to use of antibiotics, antifungals, antimalarials, or diltiazem (a calcium channel blocker). This rare cutaneous reaction occurs in 1 to 5 patients per million per year1; it carries a 1% to 2% mortality rate with proper supportive treatment.

The clinical symptoms of AGEP typically present 24 to 48 hours after drug initiation with the rapid development of dozens to thousands of 1- to 4-mm pustules, typically localized to the flexor surfaces and face. In the setting of AGEP, acute onset of fever and leukocytosis typically occur at the time of the cutaneous eruption. These features were absent in this patient. The eruption usually starts on the face and then migrates to the trunk and extremities, sparing the palms and soles. Systemic involvement most commonly presents as hepatic, renal, or pulmonary insufficiency, which has been seen in 20% of cases.2

The immunologic response associated with the reaction has been studied in vitro. Drug-specific CD8 T cells use perforin/granzyme B and Fas ligand mechanisms to induce apoptosis of the keratinocytes within the epidermis, leading to vesicle formation.3 During the very first stages of formation, vesicles mainly comprise CD8 T cells and keratinocytes. These cells then begin producing CXC-18, a potent neutrophil chemokine, leading to extensive chemotaxis of neutrophils into vesicles, which then rapidly transform to pustules.3 This rapid transformation leads to the lakes of pustules, a description often associated with AGEP.

Treatment of AGEP is mainly supportive and consists of discontinuing use of the causative agent. Topical corticosteroids can be used during the pustular phase for symptom management. There is no evidence that systemic steroids reduce the duration of the disease.2 Other supportive measures such as application of wet wraps can be used to provide comfort.

Cutaneous adverse drug reactions commonly are associated with psychiatric pharmacotherapy, but first-and second-generation antipsychotics rarely are associated with these types of reactions. In this patient, the causative agent of the AGEP was cariprazine, an atypical antipsychotic that had no reported association with AGEP or cutaneous adverse drug reactions prior to this presentation.

To the Editor:

A 57-year-old woman presented to an outpatient clinic with severe pruritus and burning of the skin as well as subjective fevers and chills. She had been discharged from a psychiatric hospital for attempted suicide 1 day prior. There were no recent changes in the medication regimen, which consisted of linaclotide, fluoxetine, lorazepam, and gabapentin. While admitted, the patient was started on the atypical antipsychotic cariprazine. Within 24 hours of the first dose, she developed severe facial erythema that progressed to diffuse erythema over more than 60% of the body surface area. The attending psychiatrist promptly discontinued cariprazine. During the next 24 hours, there were no reports of fever, leukocytosis, or signs of systemic organ involvement. Given the patient’s mental and medical stability, she was discharged with instructions to follow up with the outpatient dermatology clinic.

At the current presentation, physical examination revealed innumerable 1- to 4-mm pustules coalescing to lakes of pus on an erythematous base over more than 60% of the body surface area (Figure 1). The mucous membranes were clear of lesions, the Nikolsky sign was negative, and the patient’s temperature was 99.6 °F in the office. Complete blood cell count and complete metabolic panel results were within reference range.

A 4-mm abdominal punch biopsy showed subcorneal neutrophilic pustules, papillary dermal edema, and superficial dermal lymphohistiocytic inflammation with numerous neutrophils, eosinophils, and extravasated red blood cells, consistent with acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP)(Figure 2). The patient was started on wet wraps with triamcinolone cream 0.1%.

Two days later, physical examination revealed the erythema noted on initial examination had notably decreased, and the patient no longer reported burning or pruritus. One week after initial presentation to the clinic, the patient’s rash had resolved, and only a few small areas of desquamation remained.

Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis is a severe cutaneous adverse reaction characterized by the development of numerous nonfollicular sterile pustules on an edematous and erythematous base. In almost 90% of reported cases, the cause is related to use of antibiotics, antifungals, antimalarials, or diltiazem (a calcium channel blocker). This rare cutaneous reaction occurs in 1 to 5 patients per million per year1; it carries a 1% to 2% mortality rate with proper supportive treatment.

The clinical symptoms of AGEP typically present 24 to 48 hours after drug initiation with the rapid development of dozens to thousands of 1- to 4-mm pustules, typically localized to the flexor surfaces and face. In the setting of AGEP, acute onset of fever and leukocytosis typically occur at the time of the cutaneous eruption. These features were absent in this patient. The eruption usually starts on the face and then migrates to the trunk and extremities, sparing the palms and soles. Systemic involvement most commonly presents as hepatic, renal, or pulmonary insufficiency, which has been seen in 20% of cases.2

The immunologic response associated with the reaction has been studied in vitro. Drug-specific CD8 T cells use perforin/granzyme B and Fas ligand mechanisms to induce apoptosis of the keratinocytes within the epidermis, leading to vesicle formation.3 During the very first stages of formation, vesicles mainly comprise CD8 T cells and keratinocytes. These cells then begin producing CXC-18, a potent neutrophil chemokine, leading to extensive chemotaxis of neutrophils into vesicles, which then rapidly transform to pustules.3 This rapid transformation leads to the lakes of pustules, a description often associated with AGEP.

Treatment of AGEP is mainly supportive and consists of discontinuing use of the causative agent. Topical corticosteroids can be used during the pustular phase for symptom management. There is no evidence that systemic steroids reduce the duration of the disease.2 Other supportive measures such as application of wet wraps can be used to provide comfort.

Cutaneous adverse drug reactions commonly are associated with psychiatric pharmacotherapy, but first-and second-generation antipsychotics rarely are associated with these types of reactions. In this patient, the causative agent of the AGEP was cariprazine, an atypical antipsychotic that had no reported association with AGEP or cutaneous adverse drug reactions prior to this presentation.

- Fernando SL. Acute generalised exanthematous pustulosis. Australas J Dermatol. 2012;53:87-92.

- Feldmeyer L, Heidemeyer K, Yawalkar N. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis: pathogenesis, genetic background, clinical variants and therapy. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17:1214.

- Szatkowski J, Schwartz RA. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP): a review and update. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:843-848.

- Fernando SL. Acute generalised exanthematous pustulosis. Australas J Dermatol. 2012;53:87-92.

- Feldmeyer L, Heidemeyer K, Yawalkar N. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis: pathogenesis, genetic background, clinical variants and therapy. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17:1214.

- Szatkowski J, Schwartz RA. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP): a review and update. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:843-848.

Practice Points

- The second-generation antipsychotic cariprazine has been shown to be a potential causative agent in acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP).

- Treatment of AGEP is mainly supportive and consists of discontinuation of the causative agent as well as symptom control using cold compresses and topical corticosteroids.

Topical Timolol May Improve Overall Scar Cosmesis in Acute Surgical Wounds

Timolol is a nonselective β-adrenergic receptor antagonist indicated for treating glaucoma, heart attacks, hypertension, and migraine headaches. It is made in both an oral and ophthalmic form. In dermatology, the beta-blocker propranolol is approved for the treatment of infantile hemangiomas (IHs). The exact mechanism of action of beta-blockers for the treatment of IHs is not yet completely understood, but it is postulated that they inhibit growth by at least 4 distinct mechanisms: (1) vasoconstriction, (2) inhibition of angiogenesis or vasculogenesis, (3) induction of apoptosis, and (4) recruitment of endothelial progenitor cells to the site of the hemangioma.1

Scar cosmesis can be calculated using the visual analog scale (VAS), which is a subjective scar assessment scored from poor to excellent. The multidimensional VAS is a photograph-based scale derived from evaluating standardized digital photographs in 4 dimensions—pigmentation, vascularity, acceptability, and observer comfort—plus contour. It uses the sum of the individual scores to obtain a single overall score ranging from excellent to poor.2 In this study, we sought to determine if the use of topical timolol after excision or Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) treatment of nonmelanoma skin cancers improved the overall cosmesis of the scar.

Methods

The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board at Roger Williams Medical Center (Providence, Rhode Island). Eligibility criteria included patients who required excision or MMS for their nonmelanoma skin cancer located below the patella and those who agreed to allow their wounds to heal by secondary intention when given options for closure of their wounds. Patients were randomized to either the timolol (study medication) group or the saline (placebo) group. The initial defects were measured and photographed. Patients were educated on how to apply the study medication. All patients were prescribed 40 mm Hg compression stockings to wear following application of the study medication. Patients were asked to return at 1 and 5 weeks postsurgery and then every 1 to 2 weeks for wound assessment and measurement until their wounds had healed or at 13 weeks, depending on which came first. A healed wound was defined as having no exudate, exhibiting complete reepithelialization, and being stable for 1 week.

Healed wounds were assessed by a blinded outside dermatologist who examined photographs of the wounds and then completed the VAS for each participant’s scar.

Results

A total of 9 participants were enrolled in the study. Three participants were lost to follow-up; 6 completed the study (4 females, 2 males). The mean age was 70 years (age range, 46–89 years). The average wound size was 2×2 cm with a depth of 1 mm. Three participants were in the active medication group and 3 were in the control group.

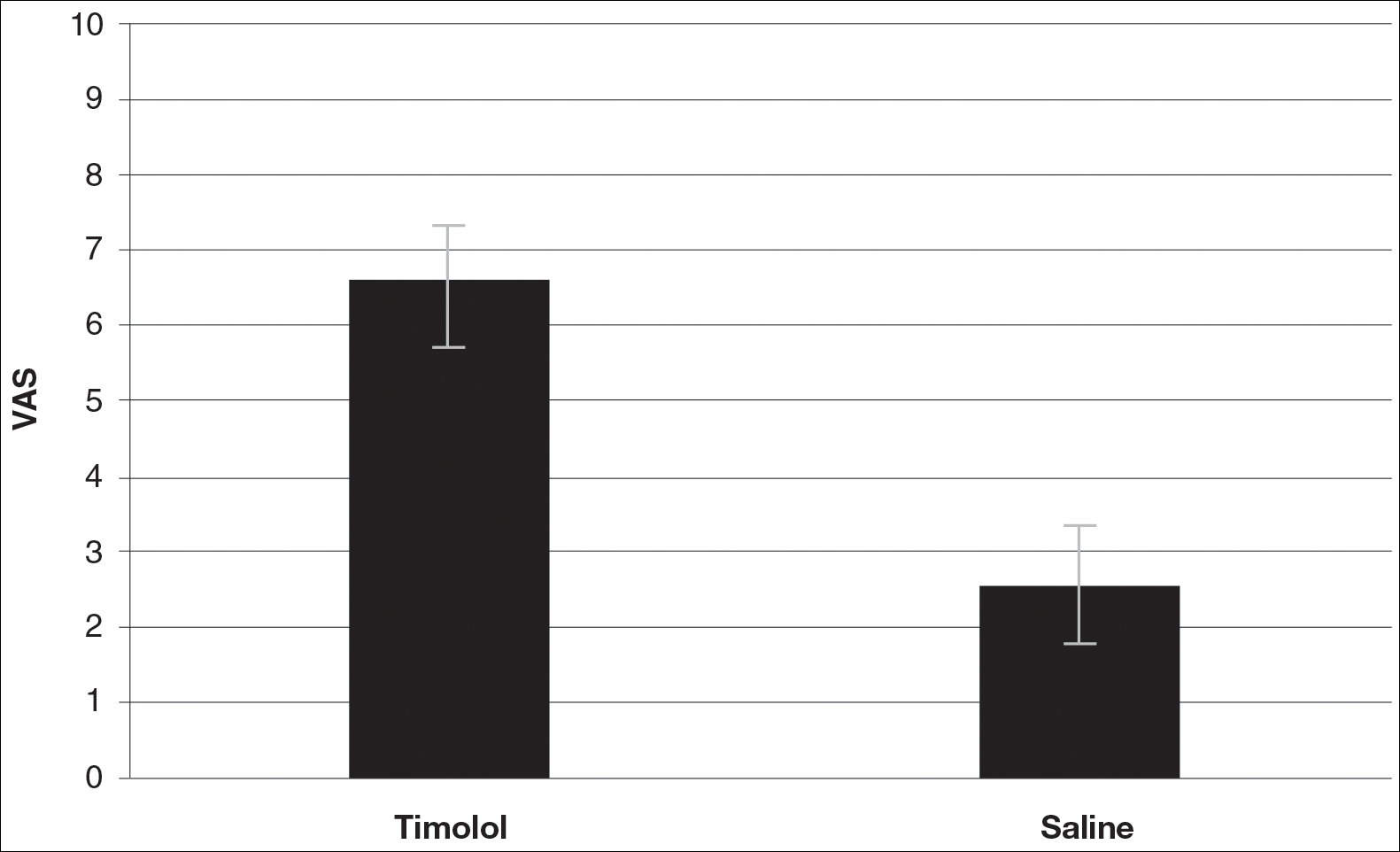

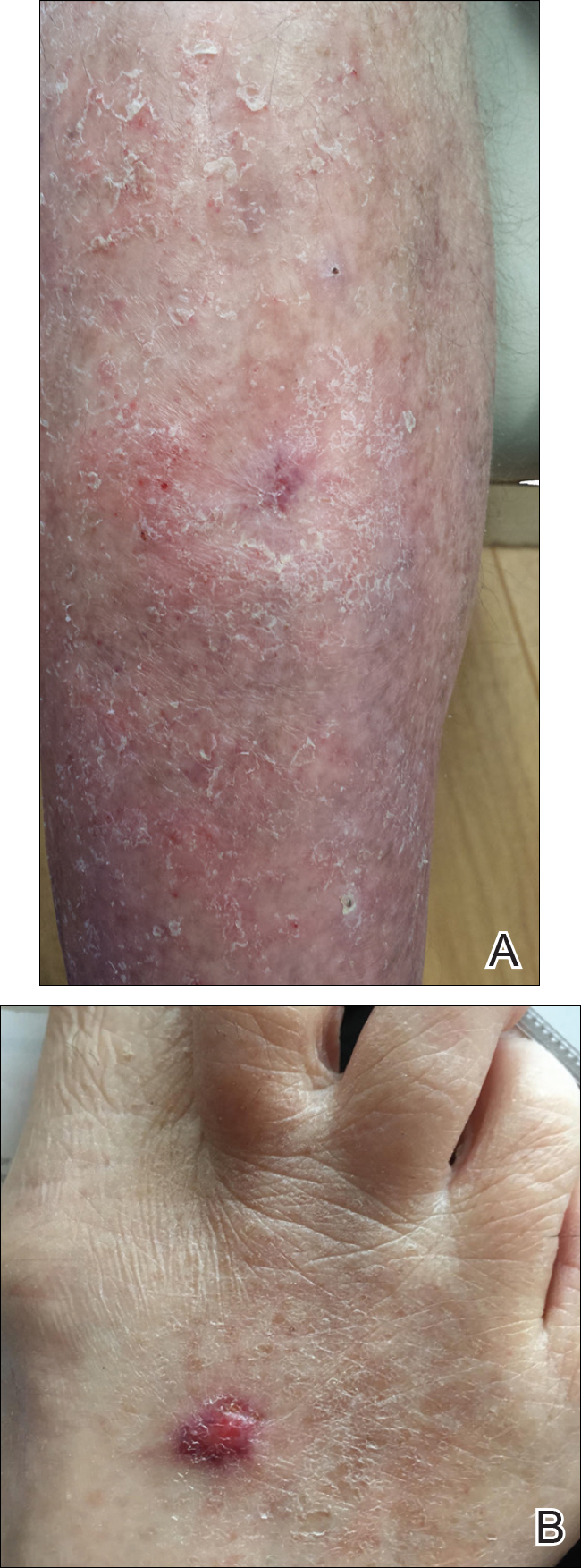

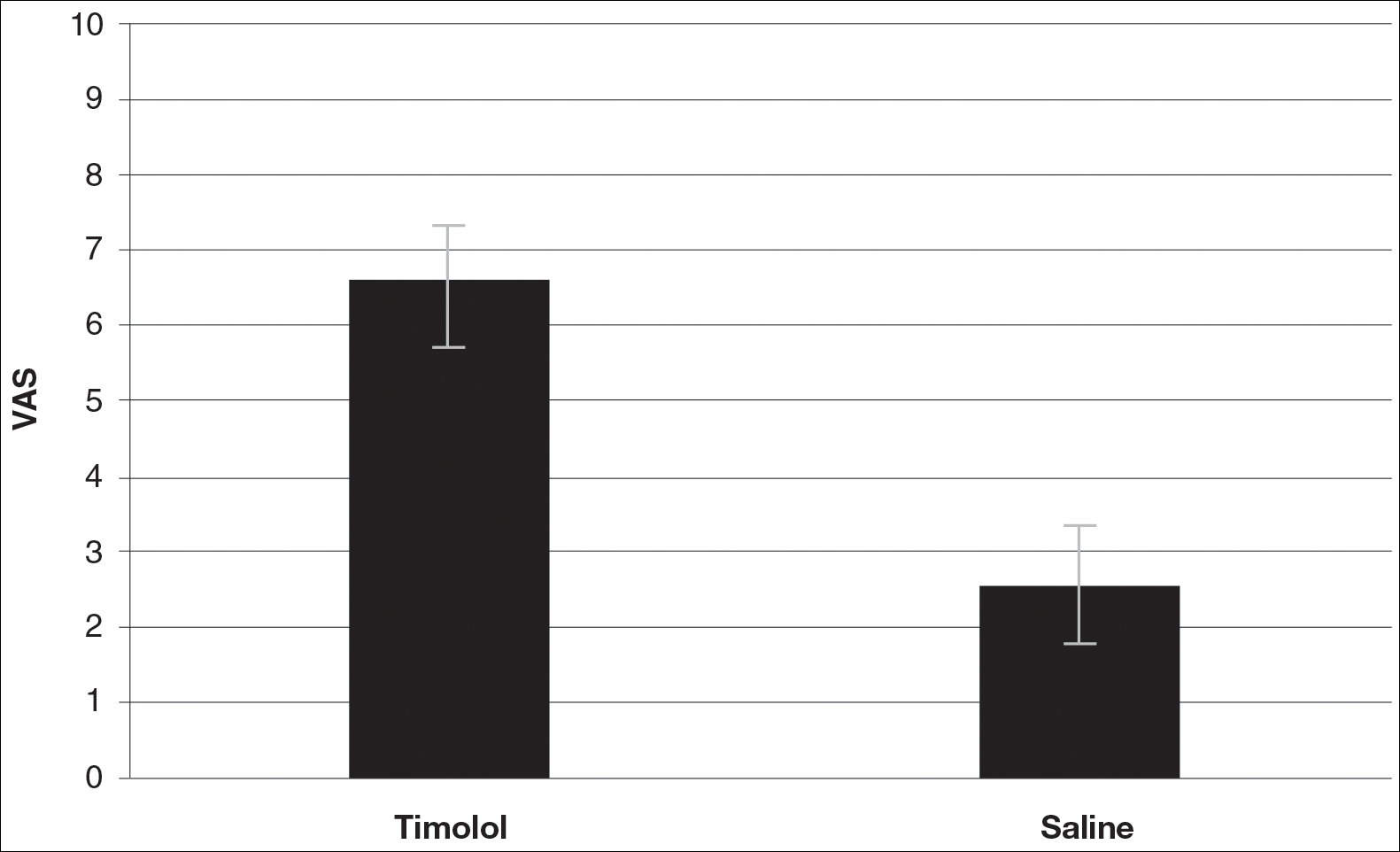

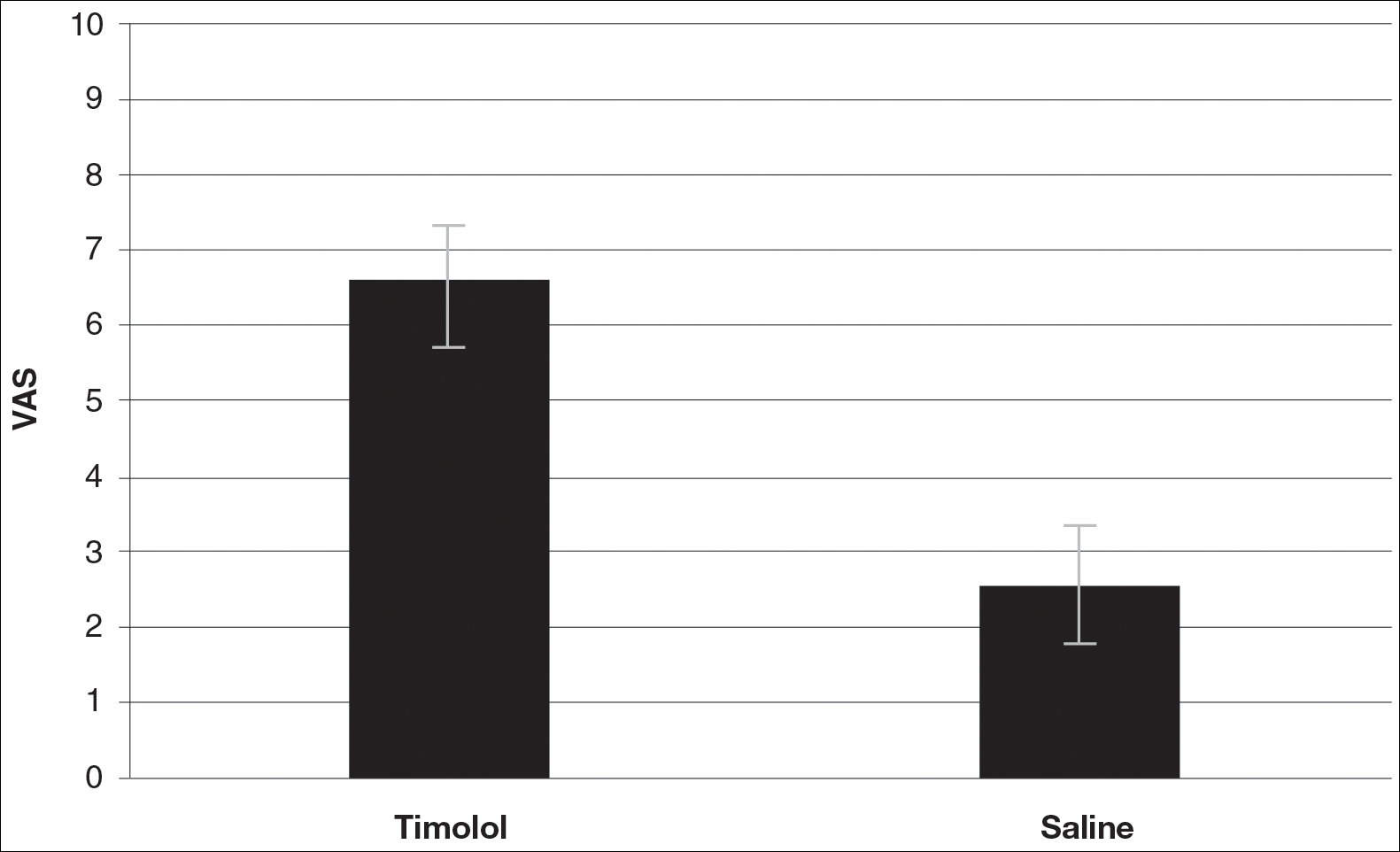

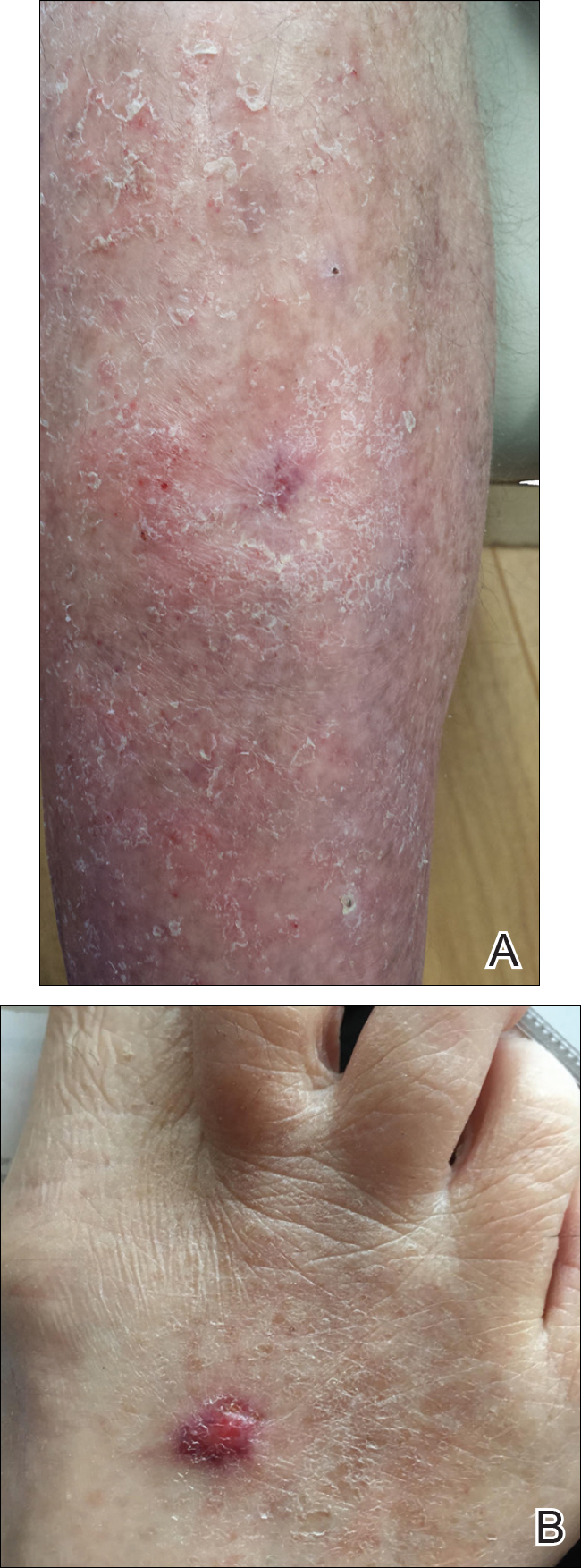

A VAS was completed for each participant’s scar by an outside blinded dermatologist. Based on the VAS, wounds treated with timolol resulted in more cosmetically favorable scars (scored higher on the VAS) compared to control (mean [SD]: 6.5±0.9 vs 2.5±0.7; P<0.05). See Figures 1 and 2 for representative results.

Comment

Dermatologists create acute wounds in patients on a daily basis. Ensuring that patients achieve the most desirable cosmetic outcome is a primary goal for dermatologists and an important component of patient satisfaction. A number of studies have examined patient satisfaction following MMS.3,4 Patient satisfaction is an especially important outcome measure in dermatology, as dermatologic diseases affect cosmetic appearance and are related to quality of life.3,4

Timolol is a nonselective β-adrenergic receptor antagonist that is used in dermatology to treat IHs. In this preliminary study, the authors sought to determine if topical timolol applied to acute wounds following surgical removal of nonmelanoma skin cancers could improve the overall cosmetic outcome of acute surgical scars. The results showed that compared to control, topical timolol resulted in a more cosmetically favorable scar. The results are preliminary, and it would be of future interest to further study the effects of topical timolol on acute surgical wounds from a wound-healing standpoint as well as to further test its effects on the cosmesis of these wounds.

- Chisholm KM, Chang KW, Truong MT, et al. β-Adrenergic receptor expression in vascular tumors [published online June 29, 2012]. Mod Pathol. 2012;25:1446-1451.

- Fearmonti R, Bond J, Erdmann D, et al. A review of scar scales and scar measuring devices. Eplasty. 2010;10:e43.

- Asgari MM, Warton EM, Neugebauer R, et al. Predictors of patient satisfaction with Mohs surgery: analysis of preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative factors in a prospective cohort. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:1387-1394.

- Asgari MM, Bertenthal D, Sen S, et al. Patient satisfaction after treatment of nonmelanoma skin cancer. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:1041-1049.

Timolol is a nonselective β-adrenergic receptor antagonist indicated for treating glaucoma, heart attacks, hypertension, and migraine headaches. It is made in both an oral and ophthalmic form. In dermatology, the beta-blocker propranolol is approved for the treatment of infantile hemangiomas (IHs). The exact mechanism of action of beta-blockers for the treatment of IHs is not yet completely understood, but it is postulated that they inhibit growth by at least 4 distinct mechanisms: (1) vasoconstriction, (2) inhibition of angiogenesis or vasculogenesis, (3) induction of apoptosis, and (4) recruitment of endothelial progenitor cells to the site of the hemangioma.1

Scar cosmesis can be calculated using the visual analog scale (VAS), which is a subjective scar assessment scored from poor to excellent. The multidimensional VAS is a photograph-based scale derived from evaluating standardized digital photographs in 4 dimensions—pigmentation, vascularity, acceptability, and observer comfort—plus contour. It uses the sum of the individual scores to obtain a single overall score ranging from excellent to poor.2 In this study, we sought to determine if the use of topical timolol after excision or Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) treatment of nonmelanoma skin cancers improved the overall cosmesis of the scar.

Methods

The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board at Roger Williams Medical Center (Providence, Rhode Island). Eligibility criteria included patients who required excision or MMS for their nonmelanoma skin cancer located below the patella and those who agreed to allow their wounds to heal by secondary intention when given options for closure of their wounds. Patients were randomized to either the timolol (study medication) group or the saline (placebo) group. The initial defects were measured and photographed. Patients were educated on how to apply the study medication. All patients were prescribed 40 mm Hg compression stockings to wear following application of the study medication. Patients were asked to return at 1 and 5 weeks postsurgery and then every 1 to 2 weeks for wound assessment and measurement until their wounds had healed or at 13 weeks, depending on which came first. A healed wound was defined as having no exudate, exhibiting complete reepithelialization, and being stable for 1 week.

Healed wounds were assessed by a blinded outside dermatologist who examined photographs of the wounds and then completed the VAS for each participant’s scar.

Results

A total of 9 participants were enrolled in the study. Three participants were lost to follow-up; 6 completed the study (4 females, 2 males). The mean age was 70 years (age range, 46–89 years). The average wound size was 2×2 cm with a depth of 1 mm. Three participants were in the active medication group and 3 were in the control group.

A VAS was completed for each participant’s scar by an outside blinded dermatologist. Based on the VAS, wounds treated with timolol resulted in more cosmetically favorable scars (scored higher on the VAS) compared to control (mean [SD]: 6.5±0.9 vs 2.5±0.7; P<0.05). See Figures 1 and 2 for representative results.

Comment

Dermatologists create acute wounds in patients on a daily basis. Ensuring that patients achieve the most desirable cosmetic outcome is a primary goal for dermatologists and an important component of patient satisfaction. A number of studies have examined patient satisfaction following MMS.3,4 Patient satisfaction is an especially important outcome measure in dermatology, as dermatologic diseases affect cosmetic appearance and are related to quality of life.3,4

Timolol is a nonselective β-adrenergic receptor antagonist that is used in dermatology to treat IHs. In this preliminary study, the authors sought to determine if topical timolol applied to acute wounds following surgical removal of nonmelanoma skin cancers could improve the overall cosmetic outcome of acute surgical scars. The results showed that compared to control, topical timolol resulted in a more cosmetically favorable scar. The results are preliminary, and it would be of future interest to further study the effects of topical timolol on acute surgical wounds from a wound-healing standpoint as well as to further test its effects on the cosmesis of these wounds.

Timolol is a nonselective β-adrenergic receptor antagonist indicated for treating glaucoma, heart attacks, hypertension, and migraine headaches. It is made in both an oral and ophthalmic form. In dermatology, the beta-blocker propranolol is approved for the treatment of infantile hemangiomas (IHs). The exact mechanism of action of beta-blockers for the treatment of IHs is not yet completely understood, but it is postulated that they inhibit growth by at least 4 distinct mechanisms: (1) vasoconstriction, (2) inhibition of angiogenesis or vasculogenesis, (3) induction of apoptosis, and (4) recruitment of endothelial progenitor cells to the site of the hemangioma.1

Scar cosmesis can be calculated using the visual analog scale (VAS), which is a subjective scar assessment scored from poor to excellent. The multidimensional VAS is a photograph-based scale derived from evaluating standardized digital photographs in 4 dimensions—pigmentation, vascularity, acceptability, and observer comfort—plus contour. It uses the sum of the individual scores to obtain a single overall score ranging from excellent to poor.2 In this study, we sought to determine if the use of topical timolol after excision or Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) treatment of nonmelanoma skin cancers improved the overall cosmesis of the scar.

Methods

The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board at Roger Williams Medical Center (Providence, Rhode Island). Eligibility criteria included patients who required excision or MMS for their nonmelanoma skin cancer located below the patella and those who agreed to allow their wounds to heal by secondary intention when given options for closure of their wounds. Patients were randomized to either the timolol (study medication) group or the saline (placebo) group. The initial defects were measured and photographed. Patients were educated on how to apply the study medication. All patients were prescribed 40 mm Hg compression stockings to wear following application of the study medication. Patients were asked to return at 1 and 5 weeks postsurgery and then every 1 to 2 weeks for wound assessment and measurement until their wounds had healed or at 13 weeks, depending on which came first. A healed wound was defined as having no exudate, exhibiting complete reepithelialization, and being stable for 1 week.

Healed wounds were assessed by a blinded outside dermatologist who examined photographs of the wounds and then completed the VAS for each participant’s scar.

Results

A total of 9 participants were enrolled in the study. Three participants were lost to follow-up; 6 completed the study (4 females, 2 males). The mean age was 70 years (age range, 46–89 years). The average wound size was 2×2 cm with a depth of 1 mm. Three participants were in the active medication group and 3 were in the control group.

A VAS was completed for each participant’s scar by an outside blinded dermatologist. Based on the VAS, wounds treated with timolol resulted in more cosmetically favorable scars (scored higher on the VAS) compared to control (mean [SD]: 6.5±0.9 vs 2.5±0.7; P<0.05). See Figures 1 and 2 for representative results.

Comment

Dermatologists create acute wounds in patients on a daily basis. Ensuring that patients achieve the most desirable cosmetic outcome is a primary goal for dermatologists and an important component of patient satisfaction. A number of studies have examined patient satisfaction following MMS.3,4 Patient satisfaction is an especially important outcome measure in dermatology, as dermatologic diseases affect cosmetic appearance and are related to quality of life.3,4

Timolol is a nonselective β-adrenergic receptor antagonist that is used in dermatology to treat IHs. In this preliminary study, the authors sought to determine if topical timolol applied to acute wounds following surgical removal of nonmelanoma skin cancers could improve the overall cosmetic outcome of acute surgical scars. The results showed that compared to control, topical timolol resulted in a more cosmetically favorable scar. The results are preliminary, and it would be of future interest to further study the effects of topical timolol on acute surgical wounds from a wound-healing standpoint as well as to further test its effects on the cosmesis of these wounds.

- Chisholm KM, Chang KW, Truong MT, et al. β-Adrenergic receptor expression in vascular tumors [published online June 29, 2012]. Mod Pathol. 2012;25:1446-1451.

- Fearmonti R, Bond J, Erdmann D, et al. A review of scar scales and scar measuring devices. Eplasty. 2010;10:e43.

- Asgari MM, Warton EM, Neugebauer R, et al. Predictors of patient satisfaction with Mohs surgery: analysis of preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative factors in a prospective cohort. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:1387-1394.

- Asgari MM, Bertenthal D, Sen S, et al. Patient satisfaction after treatment of nonmelanoma skin cancer. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:1041-1049.

- Chisholm KM, Chang KW, Truong MT, et al. β-Adrenergic receptor expression in vascular tumors [published online June 29, 2012]. Mod Pathol. 2012;25:1446-1451.

- Fearmonti R, Bond J, Erdmann D, et al. A review of scar scales and scar measuring devices. Eplasty. 2010;10:e43.

- Asgari MM, Warton EM, Neugebauer R, et al. Predictors of patient satisfaction with Mohs surgery: analysis of preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative factors in a prospective cohort. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:1387-1394.

- Asgari MM, Bertenthal D, Sen S, et al. Patient satisfaction after treatment of nonmelanoma skin cancer. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:1041-1049.

Resident Pearl

- Dermatologists create acute surgical wounds on a daily basis. We should strive for excellent patient outcomes as well as the most desirable cosmetic result. This research article points to a possible new application of a longstanding medication to improve the cosmetic outcome in acute surgical wounds.