User login

Shedding Light on Onychomadesis

Onychomadesis is an acute, noninflammatory, painless, proximal separation of the nail plate from the nail matrix. It occurs due to an abrupt stoppage of nail production by matrix cells, producing temporary cessation of nail growth with or without subsequent complete shedding of nails.1-10 Onychomadesis has a wide spectrum of clinical presentations ranging from mild transverse ridges of the nail plate (Beau lines) to complete nail shedding.4,11 Onychomadesis may be related to systemic and dermatologic diseases, drugs (eg, chemotherapeutic agents, anticonvulsants, lithium, retinoids), nail trauma, fever, or infection,5 and a connection between onychomadesis and hand-foot-and-mouth disease (HFMD) was first described by Clementz et al12 following outbreaks in Europe, Asia, and the United States.

Epidemiology

Onychomadesis has been observed in children of all ages including neonates. Neonatal onychomadesis is thought to be related to perinatal stressors and birth trauma, with possible exacerbation by superimposed candidiasis.10 Depending on the underlying cause, there may be involvement of a single nail or multiple nails. Nag et al1 noted that onychomadesis was most commonly observed in nails of the middle finger (73.7%), followed by the thumb (63.2%) and ring finger (52.6%). Fingernails are more commonly involved than toenails.1

Clementz et al12 first proposed the association between onychomadesis and HFMD in 2000. Patients with a history of HFMD were found to be 14 times more likely to develop onychomadesis (relative risk, 14; 95% confidence interval, 4.57-42.86).4 A common pathogen for HFMD is coxsackievirus A6 (CVA6),13,14 but the mechanism of onychomadesis in HFMD remains unclear.5,7,13 Outbreaks of HFMD have been reported in Spain, Finland, Japan, Thailand, the United States, Singapore, and China.15 During an outbreak of HFMD in Taiwan, the incidence of onychomadesis following CVA6 infection was 37% (48/130) compared to 5% (7/145) in cases with non-CVA6 causative strains.16 There also have been observed differences in the prevalence of onychomadesis by age: a 55% (18/33) occurrence rate was noted in the youngest age group (range, 9–23 months), 30% (8/27) in the middle age group (range, 24–32 months), and 4% (1/28) in the oldest age group (range, 33–42 months), with an average of 4 nails shed per case.17 A study in Spain also found a high occurrence of onychomadesis in a nursery setting, with 92% (11/12) of onychomadesis cases preceded by HFMD 2 months prior.18

Etiology

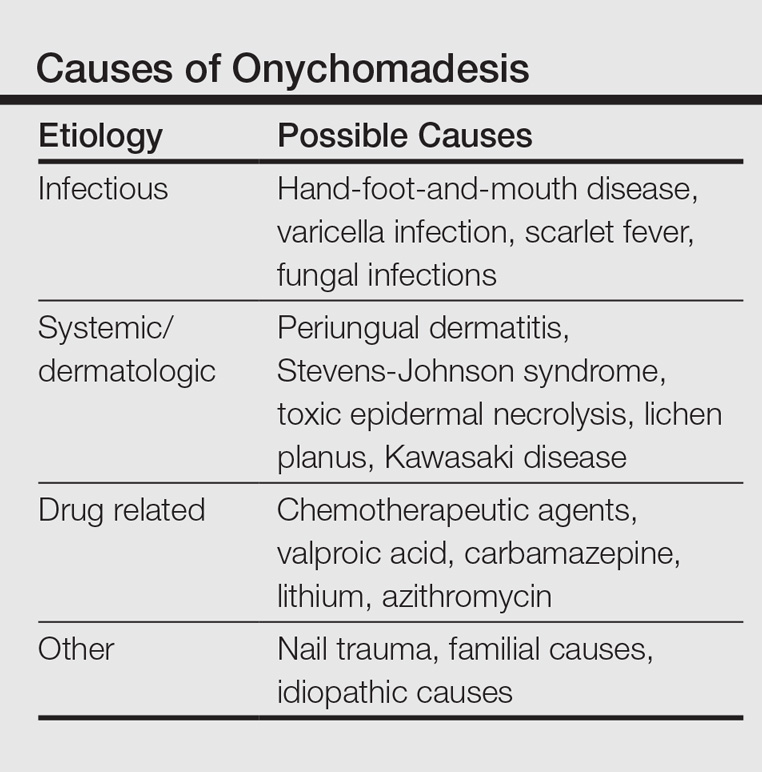

Local trauma to the nail bed is the most common cause of single-digit onychomadesis.4 Multiple-digit involvement suggests a systemic etiology such as fever, erythroderma, and Kawasaki disease; use of drugs (eg, chemotherapeutic agents, anticonvulsants, lithium, retinoids); and viral infections such as HFMD and varicella at the infantile age (Table).5,9,19 Most drug-related nail changes are the outcome of acute toxicity to the proliferating nail matrix epithelium. If onychomadesis affects all nails at the same level, the patient’s history of medication use and other treatments taken 2 to 3 weeks prior to the appearance of the nail findings should be evaluated. Chemotherapeutic agents produce nail changes in a high proportion of patients, which often are related to drug dosage. These effects also are reproducible with re-administration of the drug.20 Onychomadesis also has been reported as a possible side effect of anticonvulsants such as valproic acid (VPA).21 One study evaluating the link between VPA and onychomadesis indicated that nail changes may be due to a disturbance of zinc metabolism.22 However, the pathomechanism of onychomadesis associated with VPA treatment remains unclear.21 Onychomadesis also has developed after an allergic drug reaction to oral penicillin V after treatment of a sore throat in a 23-month-old child.23

Nail involvement has been reported in 10% of cases of inflammatory conditions such as lichen planus21; however, it may be more common but underrecognized and underreported. Grover et al9 indicated that lichen planus–induced severe inflammation in the matrix of the nail unit leading to a temporary growth arrest was the possible mechanism leading to nail shedding. Prompt systemic and intramatricial steroid treatment of lichen planus is required to avoid potential scarring of the nail matrix and permanent damage.9

Onychomadesis also has been reported following varicella infection (chickenpox). Podder et al19 reported the case of a 7-year-old girl who had recovered from a varicella infection 5 weeks prior and presented with onychomadesis of the right index fingernail with all other fingernails and toenails appearing normal. Kocak and Koçak5 reported onychomadesis in 2 sisters with varicella infection. There are few reported cases, so it is still unclear whether varicella infection is an inciting factor.19

One of the most studied viral infections linked to onychomadesis is HFMD, which is a common viral infection that mostly affects children younger than 10 years.1 The precise mechanism of onychomadesis for these viral infection events remains unclear.7,10,13 Several theories have been delineated, including nail matrix arrest from fever occurring during HFMD.6 However, this cause is unlikely, as fevers are typically low grade and present only for a few hours.4,6,13 Direct inflammation spreading from skin lesions of HFMD around the nails or maceration associated with finger blisters could cause onychomadesis.1,5,7 Haneke24 hypothesized that nail shedding may be the consequence of vesicles localized in the periungual tissue, but studies have shown incidence without prior lesions on the fingers and no relationship between nail matrix arrest and severity of HFMD.5,6,13 Bettoli et al25 reported that inflammation secondary to viral infection around the nail matrix might be induced directly by viruses or indirectly by virus-specific immunocomplexes and consequent distal embolism. Osterback et al14 used reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction to detect CVA6 in fragmented nails from 2 children and 1 parent following an HFMD episode, suggesting that virus replication could damage the nail matrix, resulting in onychomadesis. Cabrerizo et al18 also suggested that virus replication directly damages the nail matrix based on the presence of CVA6 in shed nails. Because fingernails with onychomadesis are not always of the fingers affected by HFMD, an indirect effect of viral infection on the nail matrix is more plausible.8 Additional studies are needed to clarify the virus-associated mechanism of nail matrix arrest.6 Finally, frequent washing of hands15 resulting in maceration, Candida infection, and allergic contact dermatitis2 may be possible causes. It is unclear if onychomadesis following HFMD is related to viral replication, inflammation, or intensive hygienic measures, and further investigation is needed.2,15

Clinical Characteristics

The ventral floor is the site of the germinal matrix and is responsible for 90% of nail production. As a result, more of the nail plate substance is produced proximally, leading to a natural convex curvature from the proximal to distal nail.11 Beau lines are transverse ridging of the nail plates.6 Onychomadesis may be viewed as a more severe form of Beau lines, with complete separation and possible shedding of the nail plate (Figure).3,4 In both cases, an insult to the nail matrix is followed by recovery and production of the nail plate at the nail matrix.4 In Beau lines, slowing or disruption of cell growth from the proximal matrix results in a thinner nail plate, leading to transverse depressions. Onychomadesis has a similar pathophysiology but is associated with a complete halt in the nail plate production.3

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of onychomadesis is made clinically.3,10 Distinct nail changes can be detected by inspection and palpation of the nail plate,3,11 which allows for differentiation between Beau lines and complete nail shedding. Additionally, any signs of nail trauma need to be noted, as well as pain, swelling, or pruritus, as these symptoms also can guide in determining the etiology of the nail dystrophy. Ultrasonography can confirm the diagnosis, as the defect can be identified beneath the proximal nail fold.3,26 When it occurs after HFMD or varicella, onychomadesis tends to present in 28 to 40 days following infection.4,6,10 Physicians should consider underlying associations. A review of viral illnesses within 1 to 2 months prior to development of nail changes often will identify the causative disease.4 Each patient should be evaluated for recent nail trauma; medications; viral infection; and autoimmune, systemic, and inflammatory diseases.

Treatment

Onychomadesis typically is mild and self-limited.4,10 There is no specific treatment,10 but a conservative approach to management is recommended. Treatment of any underlying medical conditions or discontinuation of an offending medication may help to prevent recurrent onychomadesis.3 Supportive care along with protection of the nail bed by maintaining short nails and using adhesive bandages over the affected nails to avoid snagging the nail or ripping off the partially attached nails is recommended.4 In some cases, onychomadesis has been treated with topical application of urea cream 40% under occlusion27 or halcinonide cream 0.1% under occlusion for 5 to 6 days,28 but these treatments have not been universally effective.3 External use of basic fibroblast growth factor to stimulate new regrowth of the nail plate has been advocated.3 It is important to reassure patients that as long as the underlying causes are eliminated and the nail matrix has not been permanently scarred, the nails should grow back within 12 weeks or sooner in children. Thus, typically only reassurance and counseling of parents/guardians is required for onychomadesis in children.1,2 However, the nails may be dystrophic or fail to regrow if there is poor peripheral circulation or permanent nail matrix damage.

Conclusion

Fortunately, onychomadesis is self-limited. Physicians should look for underlying causes of onychomadesis, including a history of viral infections such as HFMD and varicella as well as systemic diseases and use of medications. As long as any underlying disorder or condition has been resolved, spontaneous regrowth of healthy nails usually but not always occurs within 12 weeks or sooner in children.

- Nag SS, Dutta A, Mandal RK. Delayed cutaneous findings of hand, foot, and mouth disease. Indian Pediatr. 2016;53:42-44.

- Tan ZH, Koh MJ. Nail shedding following hand, foot and mouth disease. Arch Dis Child. 2013;98:665.

- Braswell MA, Daniel CR, Brodell RT. Beau lines, onychomadesis, and retronychia: a unifying hypothesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:849-855.

- Clark CM, Silverberg NB, Weinberg JM. What is your diagnosis? onychomadesis following hand-foot-and-mouth disease. Cutis. 2015;95:312, 319-320.

- Kocak AY, Koçak O. Onychomadesis in two sisters induced by varicella infection. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:E108-E109.

- Shin JY, Cho BK, Park HJ. A clinical study of nail changes occurring secondary to hand-foot-mouth disease: onychomadesis and Beau’s lines. Ann Dermatol. 2014;26:280-283.

- Shikuma E, Endo Y, Fujisawa A, et al. Onychomadesis developed only on the nails having cutaneous lesions of severe hand-foot-mouth disease. Case Rep Dermatol Med. 2011;2011:324193.

- Kim EJ, Park HS, Yoon HS, et al. Four cases of onychomadesis after hand-foot-mouth disease. Ann Dermatol. 2014;26:777-778.

- Grover C, Vohra S. Onychomadesis with lichen planus: an under-recognized manifestation. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:420.

- Chu DH, Rubin AI. Diagnosis and management of nail disorders. In: Holland K, ed. The Pediatric Clinics of North America. Vol 61. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2014:301-302.

- Kowalewski C, Schwartz RA. Components, growth, and composition of the nail. In: Demis D, ed. Clinical Dermatology. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott-Raven; 1998.

- Clementz GC, Mancini AJ. Nail matrix arrest following hand-foot-mouth disease: a report of five children. Pediatr Dermatol. 2000;17:7-11.

- Scarfì F, Arunachalam M, Galeone M, et al. An uncommon onychomadesis in adults. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:1392-1394.

- Osterback R, Vuorinen T, Linna M, et al. Coxsackievirus A6 and hand, foot, and mouth disease, Finland. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15:1485-1488.

- Yan X, Zhang ZZ, Yang ZH, et al. Clinical and etiological characteristics of atypical hand-foot-and-mouth disease in children from Chongqing, China: a retrospective study [published online November 26, 2015]. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:802046.

- Wei SH, Huang YP, Liu MC, et al. An outbreak of coxsackievirus A6 hand, foot, and mouth disease associated with onychomadesis in Taiwan, 2010. BMC Infect Dis. 2011;11:346.

- Guimbao J, Rodrigo P, Alberto MJ, et al. Onychomadesis outbreak linked to hand, foot, and mouth disease, Spain, July 2008. Euro Surveill. 2010;15:19663.

- Cabrerizo M, De Miguel T, Armada A, et al. Onychomadesis after a hand, foot, and mouth disease outbreak in Spain, 2009. Epidemiol Infect. 2010;138:1775-1778.

- Podder I, Das A, Gharami RC. Onychomadesis following varicella infection: is it a mere co-incidence? Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:626-627.

- Piraccini BM, Iorizzo M, Tosti A. Drug-induced nail abnormalities. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2003;4:31-37.

- Poretti A, Lips U, Belvedere M, et al. Onychomadesis: a rare side-effect of valproic acid medication? Pediatr Dermatol. 2009;26:749-750.

- Grech V, Vella C. Generalized onycholoysis associated with sodium valproate therapy. Eur Neurol. 1999;42:64-65.

- Shah RK, Uddin M, Fatunde OJ. Onychomadesis secondary to penicillin allergy in a child. J Pediatr. 2012;161:166.

- Haneke E. Onychomadesis and hand, foot and mouth disease—is there a connection? Euro Surveill. 2010;15(37).

- Bettoli V, Zauli S, Toni G, et al. Onychomadesis following hand, foot, and mouth disease: a case report from Italy and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:728-730.

- Wortsman X, Wortsman J, Guerrero R, et al. Anatomical changes in retronychia and onychomadesis detected using ultrasound. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:1615-1620.

- Fleming CJ, Hunt MJ, Barnetson RS. Mycosis fungoides with onychomadesis. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135:1012-1013.

- Mishra D, Singh G, Pandey SS. Possible carbamazepine-induced reversible onychomadesis. Int J Dermatol. 1989;28:460-461.

Onychomadesis is an acute, noninflammatory, painless, proximal separation of the nail plate from the nail matrix. It occurs due to an abrupt stoppage of nail production by matrix cells, producing temporary cessation of nail growth with or without subsequent complete shedding of nails.1-10 Onychomadesis has a wide spectrum of clinical presentations ranging from mild transverse ridges of the nail plate (Beau lines) to complete nail shedding.4,11 Onychomadesis may be related to systemic and dermatologic diseases, drugs (eg, chemotherapeutic agents, anticonvulsants, lithium, retinoids), nail trauma, fever, or infection,5 and a connection between onychomadesis and hand-foot-and-mouth disease (HFMD) was first described by Clementz et al12 following outbreaks in Europe, Asia, and the United States.

Epidemiology

Onychomadesis has been observed in children of all ages including neonates. Neonatal onychomadesis is thought to be related to perinatal stressors and birth trauma, with possible exacerbation by superimposed candidiasis.10 Depending on the underlying cause, there may be involvement of a single nail or multiple nails. Nag et al1 noted that onychomadesis was most commonly observed in nails of the middle finger (73.7%), followed by the thumb (63.2%) and ring finger (52.6%). Fingernails are more commonly involved than toenails.1

Clementz et al12 first proposed the association between onychomadesis and HFMD in 2000. Patients with a history of HFMD were found to be 14 times more likely to develop onychomadesis (relative risk, 14; 95% confidence interval, 4.57-42.86).4 A common pathogen for HFMD is coxsackievirus A6 (CVA6),13,14 but the mechanism of onychomadesis in HFMD remains unclear.5,7,13 Outbreaks of HFMD have been reported in Spain, Finland, Japan, Thailand, the United States, Singapore, and China.15 During an outbreak of HFMD in Taiwan, the incidence of onychomadesis following CVA6 infection was 37% (48/130) compared to 5% (7/145) in cases with non-CVA6 causative strains.16 There also have been observed differences in the prevalence of onychomadesis by age: a 55% (18/33) occurrence rate was noted in the youngest age group (range, 9–23 months), 30% (8/27) in the middle age group (range, 24–32 months), and 4% (1/28) in the oldest age group (range, 33–42 months), with an average of 4 nails shed per case.17 A study in Spain also found a high occurrence of onychomadesis in a nursery setting, with 92% (11/12) of onychomadesis cases preceded by HFMD 2 months prior.18

Etiology

Local trauma to the nail bed is the most common cause of single-digit onychomadesis.4 Multiple-digit involvement suggests a systemic etiology such as fever, erythroderma, and Kawasaki disease; use of drugs (eg, chemotherapeutic agents, anticonvulsants, lithium, retinoids); and viral infections such as HFMD and varicella at the infantile age (Table).5,9,19 Most drug-related nail changes are the outcome of acute toxicity to the proliferating nail matrix epithelium. If onychomadesis affects all nails at the same level, the patient’s history of medication use and other treatments taken 2 to 3 weeks prior to the appearance of the nail findings should be evaluated. Chemotherapeutic agents produce nail changes in a high proportion of patients, which often are related to drug dosage. These effects also are reproducible with re-administration of the drug.20 Onychomadesis also has been reported as a possible side effect of anticonvulsants such as valproic acid (VPA).21 One study evaluating the link between VPA and onychomadesis indicated that nail changes may be due to a disturbance of zinc metabolism.22 However, the pathomechanism of onychomadesis associated with VPA treatment remains unclear.21 Onychomadesis also has developed after an allergic drug reaction to oral penicillin V after treatment of a sore throat in a 23-month-old child.23

Nail involvement has been reported in 10% of cases of inflammatory conditions such as lichen planus21; however, it may be more common but underrecognized and underreported. Grover et al9 indicated that lichen planus–induced severe inflammation in the matrix of the nail unit leading to a temporary growth arrest was the possible mechanism leading to nail shedding. Prompt systemic and intramatricial steroid treatment of lichen planus is required to avoid potential scarring of the nail matrix and permanent damage.9

Onychomadesis also has been reported following varicella infection (chickenpox). Podder et al19 reported the case of a 7-year-old girl who had recovered from a varicella infection 5 weeks prior and presented with onychomadesis of the right index fingernail with all other fingernails and toenails appearing normal. Kocak and Koçak5 reported onychomadesis in 2 sisters with varicella infection. There are few reported cases, so it is still unclear whether varicella infection is an inciting factor.19

One of the most studied viral infections linked to onychomadesis is HFMD, which is a common viral infection that mostly affects children younger than 10 years.1 The precise mechanism of onychomadesis for these viral infection events remains unclear.7,10,13 Several theories have been delineated, including nail matrix arrest from fever occurring during HFMD.6 However, this cause is unlikely, as fevers are typically low grade and present only for a few hours.4,6,13 Direct inflammation spreading from skin lesions of HFMD around the nails or maceration associated with finger blisters could cause onychomadesis.1,5,7 Haneke24 hypothesized that nail shedding may be the consequence of vesicles localized in the periungual tissue, but studies have shown incidence without prior lesions on the fingers and no relationship between nail matrix arrest and severity of HFMD.5,6,13 Bettoli et al25 reported that inflammation secondary to viral infection around the nail matrix might be induced directly by viruses or indirectly by virus-specific immunocomplexes and consequent distal embolism. Osterback et al14 used reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction to detect CVA6 in fragmented nails from 2 children and 1 parent following an HFMD episode, suggesting that virus replication could damage the nail matrix, resulting in onychomadesis. Cabrerizo et al18 also suggested that virus replication directly damages the nail matrix based on the presence of CVA6 in shed nails. Because fingernails with onychomadesis are not always of the fingers affected by HFMD, an indirect effect of viral infection on the nail matrix is more plausible.8 Additional studies are needed to clarify the virus-associated mechanism of nail matrix arrest.6 Finally, frequent washing of hands15 resulting in maceration, Candida infection, and allergic contact dermatitis2 may be possible causes. It is unclear if onychomadesis following HFMD is related to viral replication, inflammation, or intensive hygienic measures, and further investigation is needed.2,15

Clinical Characteristics

The ventral floor is the site of the germinal matrix and is responsible for 90% of nail production. As a result, more of the nail plate substance is produced proximally, leading to a natural convex curvature from the proximal to distal nail.11 Beau lines are transverse ridging of the nail plates.6 Onychomadesis may be viewed as a more severe form of Beau lines, with complete separation and possible shedding of the nail plate (Figure).3,4 In both cases, an insult to the nail matrix is followed by recovery and production of the nail plate at the nail matrix.4 In Beau lines, slowing or disruption of cell growth from the proximal matrix results in a thinner nail plate, leading to transverse depressions. Onychomadesis has a similar pathophysiology but is associated with a complete halt in the nail plate production.3

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of onychomadesis is made clinically.3,10 Distinct nail changes can be detected by inspection and palpation of the nail plate,3,11 which allows for differentiation between Beau lines and complete nail shedding. Additionally, any signs of nail trauma need to be noted, as well as pain, swelling, or pruritus, as these symptoms also can guide in determining the etiology of the nail dystrophy. Ultrasonography can confirm the diagnosis, as the defect can be identified beneath the proximal nail fold.3,26 When it occurs after HFMD or varicella, onychomadesis tends to present in 28 to 40 days following infection.4,6,10 Physicians should consider underlying associations. A review of viral illnesses within 1 to 2 months prior to development of nail changes often will identify the causative disease.4 Each patient should be evaluated for recent nail trauma; medications; viral infection; and autoimmune, systemic, and inflammatory diseases.

Treatment

Onychomadesis typically is mild and self-limited.4,10 There is no specific treatment,10 but a conservative approach to management is recommended. Treatment of any underlying medical conditions or discontinuation of an offending medication may help to prevent recurrent onychomadesis.3 Supportive care along with protection of the nail bed by maintaining short nails and using adhesive bandages over the affected nails to avoid snagging the nail or ripping off the partially attached nails is recommended.4 In some cases, onychomadesis has been treated with topical application of urea cream 40% under occlusion27 or halcinonide cream 0.1% under occlusion for 5 to 6 days,28 but these treatments have not been universally effective.3 External use of basic fibroblast growth factor to stimulate new regrowth of the nail plate has been advocated.3 It is important to reassure patients that as long as the underlying causes are eliminated and the nail matrix has not been permanently scarred, the nails should grow back within 12 weeks or sooner in children. Thus, typically only reassurance and counseling of parents/guardians is required for onychomadesis in children.1,2 However, the nails may be dystrophic or fail to regrow if there is poor peripheral circulation or permanent nail matrix damage.

Conclusion

Fortunately, onychomadesis is self-limited. Physicians should look for underlying causes of onychomadesis, including a history of viral infections such as HFMD and varicella as well as systemic diseases and use of medications. As long as any underlying disorder or condition has been resolved, spontaneous regrowth of healthy nails usually but not always occurs within 12 weeks or sooner in children.

Onychomadesis is an acute, noninflammatory, painless, proximal separation of the nail plate from the nail matrix. It occurs due to an abrupt stoppage of nail production by matrix cells, producing temporary cessation of nail growth with or without subsequent complete shedding of nails.1-10 Onychomadesis has a wide spectrum of clinical presentations ranging from mild transverse ridges of the nail plate (Beau lines) to complete nail shedding.4,11 Onychomadesis may be related to systemic and dermatologic diseases, drugs (eg, chemotherapeutic agents, anticonvulsants, lithium, retinoids), nail trauma, fever, or infection,5 and a connection between onychomadesis and hand-foot-and-mouth disease (HFMD) was first described by Clementz et al12 following outbreaks in Europe, Asia, and the United States.

Epidemiology

Onychomadesis has been observed in children of all ages including neonates. Neonatal onychomadesis is thought to be related to perinatal stressors and birth trauma, with possible exacerbation by superimposed candidiasis.10 Depending on the underlying cause, there may be involvement of a single nail or multiple nails. Nag et al1 noted that onychomadesis was most commonly observed in nails of the middle finger (73.7%), followed by the thumb (63.2%) and ring finger (52.6%). Fingernails are more commonly involved than toenails.1

Clementz et al12 first proposed the association between onychomadesis and HFMD in 2000. Patients with a history of HFMD were found to be 14 times more likely to develop onychomadesis (relative risk, 14; 95% confidence interval, 4.57-42.86).4 A common pathogen for HFMD is coxsackievirus A6 (CVA6),13,14 but the mechanism of onychomadesis in HFMD remains unclear.5,7,13 Outbreaks of HFMD have been reported in Spain, Finland, Japan, Thailand, the United States, Singapore, and China.15 During an outbreak of HFMD in Taiwan, the incidence of onychomadesis following CVA6 infection was 37% (48/130) compared to 5% (7/145) in cases with non-CVA6 causative strains.16 There also have been observed differences in the prevalence of onychomadesis by age: a 55% (18/33) occurrence rate was noted in the youngest age group (range, 9–23 months), 30% (8/27) in the middle age group (range, 24–32 months), and 4% (1/28) in the oldest age group (range, 33–42 months), with an average of 4 nails shed per case.17 A study in Spain also found a high occurrence of onychomadesis in a nursery setting, with 92% (11/12) of onychomadesis cases preceded by HFMD 2 months prior.18

Etiology

Local trauma to the nail bed is the most common cause of single-digit onychomadesis.4 Multiple-digit involvement suggests a systemic etiology such as fever, erythroderma, and Kawasaki disease; use of drugs (eg, chemotherapeutic agents, anticonvulsants, lithium, retinoids); and viral infections such as HFMD and varicella at the infantile age (Table).5,9,19 Most drug-related nail changes are the outcome of acute toxicity to the proliferating nail matrix epithelium. If onychomadesis affects all nails at the same level, the patient’s history of medication use and other treatments taken 2 to 3 weeks prior to the appearance of the nail findings should be evaluated. Chemotherapeutic agents produce nail changes in a high proportion of patients, which often are related to drug dosage. These effects also are reproducible with re-administration of the drug.20 Onychomadesis also has been reported as a possible side effect of anticonvulsants such as valproic acid (VPA).21 One study evaluating the link between VPA and onychomadesis indicated that nail changes may be due to a disturbance of zinc metabolism.22 However, the pathomechanism of onychomadesis associated with VPA treatment remains unclear.21 Onychomadesis also has developed after an allergic drug reaction to oral penicillin V after treatment of a sore throat in a 23-month-old child.23

Nail involvement has been reported in 10% of cases of inflammatory conditions such as lichen planus21; however, it may be more common but underrecognized and underreported. Grover et al9 indicated that lichen planus–induced severe inflammation in the matrix of the nail unit leading to a temporary growth arrest was the possible mechanism leading to nail shedding. Prompt systemic and intramatricial steroid treatment of lichen planus is required to avoid potential scarring of the nail matrix and permanent damage.9

Onychomadesis also has been reported following varicella infection (chickenpox). Podder et al19 reported the case of a 7-year-old girl who had recovered from a varicella infection 5 weeks prior and presented with onychomadesis of the right index fingernail with all other fingernails and toenails appearing normal. Kocak and Koçak5 reported onychomadesis in 2 sisters with varicella infection. There are few reported cases, so it is still unclear whether varicella infection is an inciting factor.19

One of the most studied viral infections linked to onychomadesis is HFMD, which is a common viral infection that mostly affects children younger than 10 years.1 The precise mechanism of onychomadesis for these viral infection events remains unclear.7,10,13 Several theories have been delineated, including nail matrix arrest from fever occurring during HFMD.6 However, this cause is unlikely, as fevers are typically low grade and present only for a few hours.4,6,13 Direct inflammation spreading from skin lesions of HFMD around the nails or maceration associated with finger blisters could cause onychomadesis.1,5,7 Haneke24 hypothesized that nail shedding may be the consequence of vesicles localized in the periungual tissue, but studies have shown incidence without prior lesions on the fingers and no relationship between nail matrix arrest and severity of HFMD.5,6,13 Bettoli et al25 reported that inflammation secondary to viral infection around the nail matrix might be induced directly by viruses or indirectly by virus-specific immunocomplexes and consequent distal embolism. Osterback et al14 used reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction to detect CVA6 in fragmented nails from 2 children and 1 parent following an HFMD episode, suggesting that virus replication could damage the nail matrix, resulting in onychomadesis. Cabrerizo et al18 also suggested that virus replication directly damages the nail matrix based on the presence of CVA6 in shed nails. Because fingernails with onychomadesis are not always of the fingers affected by HFMD, an indirect effect of viral infection on the nail matrix is more plausible.8 Additional studies are needed to clarify the virus-associated mechanism of nail matrix arrest.6 Finally, frequent washing of hands15 resulting in maceration, Candida infection, and allergic contact dermatitis2 may be possible causes. It is unclear if onychomadesis following HFMD is related to viral replication, inflammation, or intensive hygienic measures, and further investigation is needed.2,15

Clinical Characteristics

The ventral floor is the site of the germinal matrix and is responsible for 90% of nail production. As a result, more of the nail plate substance is produced proximally, leading to a natural convex curvature from the proximal to distal nail.11 Beau lines are transverse ridging of the nail plates.6 Onychomadesis may be viewed as a more severe form of Beau lines, with complete separation and possible shedding of the nail plate (Figure).3,4 In both cases, an insult to the nail matrix is followed by recovery and production of the nail plate at the nail matrix.4 In Beau lines, slowing or disruption of cell growth from the proximal matrix results in a thinner nail plate, leading to transverse depressions. Onychomadesis has a similar pathophysiology but is associated with a complete halt in the nail plate production.3

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of onychomadesis is made clinically.3,10 Distinct nail changes can be detected by inspection and palpation of the nail plate,3,11 which allows for differentiation between Beau lines and complete nail shedding. Additionally, any signs of nail trauma need to be noted, as well as pain, swelling, or pruritus, as these symptoms also can guide in determining the etiology of the nail dystrophy. Ultrasonography can confirm the diagnosis, as the defect can be identified beneath the proximal nail fold.3,26 When it occurs after HFMD or varicella, onychomadesis tends to present in 28 to 40 days following infection.4,6,10 Physicians should consider underlying associations. A review of viral illnesses within 1 to 2 months prior to development of nail changes often will identify the causative disease.4 Each patient should be evaluated for recent nail trauma; medications; viral infection; and autoimmune, systemic, and inflammatory diseases.

Treatment

Onychomadesis typically is mild and self-limited.4,10 There is no specific treatment,10 but a conservative approach to management is recommended. Treatment of any underlying medical conditions or discontinuation of an offending medication may help to prevent recurrent onychomadesis.3 Supportive care along with protection of the nail bed by maintaining short nails and using adhesive bandages over the affected nails to avoid snagging the nail or ripping off the partially attached nails is recommended.4 In some cases, onychomadesis has been treated with topical application of urea cream 40% under occlusion27 or halcinonide cream 0.1% under occlusion for 5 to 6 days,28 but these treatments have not been universally effective.3 External use of basic fibroblast growth factor to stimulate new regrowth of the nail plate has been advocated.3 It is important to reassure patients that as long as the underlying causes are eliminated and the nail matrix has not been permanently scarred, the nails should grow back within 12 weeks or sooner in children. Thus, typically only reassurance and counseling of parents/guardians is required for onychomadesis in children.1,2 However, the nails may be dystrophic or fail to regrow if there is poor peripheral circulation or permanent nail matrix damage.

Conclusion

Fortunately, onychomadesis is self-limited. Physicians should look for underlying causes of onychomadesis, including a history of viral infections such as HFMD and varicella as well as systemic diseases and use of medications. As long as any underlying disorder or condition has been resolved, spontaneous regrowth of healthy nails usually but not always occurs within 12 weeks or sooner in children.

- Nag SS, Dutta A, Mandal RK. Delayed cutaneous findings of hand, foot, and mouth disease. Indian Pediatr. 2016;53:42-44.

- Tan ZH, Koh MJ. Nail shedding following hand, foot and mouth disease. Arch Dis Child. 2013;98:665.

- Braswell MA, Daniel CR, Brodell RT. Beau lines, onychomadesis, and retronychia: a unifying hypothesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:849-855.

- Clark CM, Silverberg NB, Weinberg JM. What is your diagnosis? onychomadesis following hand-foot-and-mouth disease. Cutis. 2015;95:312, 319-320.

- Kocak AY, Koçak O. Onychomadesis in two sisters induced by varicella infection. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:E108-E109.

- Shin JY, Cho BK, Park HJ. A clinical study of nail changes occurring secondary to hand-foot-mouth disease: onychomadesis and Beau’s lines. Ann Dermatol. 2014;26:280-283.

- Shikuma E, Endo Y, Fujisawa A, et al. Onychomadesis developed only on the nails having cutaneous lesions of severe hand-foot-mouth disease. Case Rep Dermatol Med. 2011;2011:324193.

- Kim EJ, Park HS, Yoon HS, et al. Four cases of onychomadesis after hand-foot-mouth disease. Ann Dermatol. 2014;26:777-778.

- Grover C, Vohra S. Onychomadesis with lichen planus: an under-recognized manifestation. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:420.

- Chu DH, Rubin AI. Diagnosis and management of nail disorders. In: Holland K, ed. The Pediatric Clinics of North America. Vol 61. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2014:301-302.

- Kowalewski C, Schwartz RA. Components, growth, and composition of the nail. In: Demis D, ed. Clinical Dermatology. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott-Raven; 1998.

- Clementz GC, Mancini AJ. Nail matrix arrest following hand-foot-mouth disease: a report of five children. Pediatr Dermatol. 2000;17:7-11.

- Scarfì F, Arunachalam M, Galeone M, et al. An uncommon onychomadesis in adults. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:1392-1394.

- Osterback R, Vuorinen T, Linna M, et al. Coxsackievirus A6 and hand, foot, and mouth disease, Finland. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15:1485-1488.

- Yan X, Zhang ZZ, Yang ZH, et al. Clinical and etiological characteristics of atypical hand-foot-and-mouth disease in children from Chongqing, China: a retrospective study [published online November 26, 2015]. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:802046.

- Wei SH, Huang YP, Liu MC, et al. An outbreak of coxsackievirus A6 hand, foot, and mouth disease associated with onychomadesis in Taiwan, 2010. BMC Infect Dis. 2011;11:346.

- Guimbao J, Rodrigo P, Alberto MJ, et al. Onychomadesis outbreak linked to hand, foot, and mouth disease, Spain, July 2008. Euro Surveill. 2010;15:19663.

- Cabrerizo M, De Miguel T, Armada A, et al. Onychomadesis after a hand, foot, and mouth disease outbreak in Spain, 2009. Epidemiol Infect. 2010;138:1775-1778.

- Podder I, Das A, Gharami RC. Onychomadesis following varicella infection: is it a mere co-incidence? Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:626-627.

- Piraccini BM, Iorizzo M, Tosti A. Drug-induced nail abnormalities. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2003;4:31-37.

- Poretti A, Lips U, Belvedere M, et al. Onychomadesis: a rare side-effect of valproic acid medication? Pediatr Dermatol. 2009;26:749-750.

- Grech V, Vella C. Generalized onycholoysis associated with sodium valproate therapy. Eur Neurol. 1999;42:64-65.

- Shah RK, Uddin M, Fatunde OJ. Onychomadesis secondary to penicillin allergy in a child. J Pediatr. 2012;161:166.

- Haneke E. Onychomadesis and hand, foot and mouth disease—is there a connection? Euro Surveill. 2010;15(37).

- Bettoli V, Zauli S, Toni G, et al. Onychomadesis following hand, foot, and mouth disease: a case report from Italy and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:728-730.

- Wortsman X, Wortsman J, Guerrero R, et al. Anatomical changes in retronychia and onychomadesis detected using ultrasound. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:1615-1620.

- Fleming CJ, Hunt MJ, Barnetson RS. Mycosis fungoides with onychomadesis. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135:1012-1013.

- Mishra D, Singh G, Pandey SS. Possible carbamazepine-induced reversible onychomadesis. Int J Dermatol. 1989;28:460-461.

- Nag SS, Dutta A, Mandal RK. Delayed cutaneous findings of hand, foot, and mouth disease. Indian Pediatr. 2016;53:42-44.

- Tan ZH, Koh MJ. Nail shedding following hand, foot and mouth disease. Arch Dis Child. 2013;98:665.

- Braswell MA, Daniel CR, Brodell RT. Beau lines, onychomadesis, and retronychia: a unifying hypothesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:849-855.

- Clark CM, Silverberg NB, Weinberg JM. What is your diagnosis? onychomadesis following hand-foot-and-mouth disease. Cutis. 2015;95:312, 319-320.

- Kocak AY, Koçak O. Onychomadesis in two sisters induced by varicella infection. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:E108-E109.

- Shin JY, Cho BK, Park HJ. A clinical study of nail changes occurring secondary to hand-foot-mouth disease: onychomadesis and Beau’s lines. Ann Dermatol. 2014;26:280-283.

- Shikuma E, Endo Y, Fujisawa A, et al. Onychomadesis developed only on the nails having cutaneous lesions of severe hand-foot-mouth disease. Case Rep Dermatol Med. 2011;2011:324193.

- Kim EJ, Park HS, Yoon HS, et al. Four cases of onychomadesis after hand-foot-mouth disease. Ann Dermatol. 2014;26:777-778.

- Grover C, Vohra S. Onychomadesis with lichen planus: an under-recognized manifestation. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:420.

- Chu DH, Rubin AI. Diagnosis and management of nail disorders. In: Holland K, ed. The Pediatric Clinics of North America. Vol 61. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2014:301-302.

- Kowalewski C, Schwartz RA. Components, growth, and composition of the nail. In: Demis D, ed. Clinical Dermatology. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott-Raven; 1998.

- Clementz GC, Mancini AJ. Nail matrix arrest following hand-foot-mouth disease: a report of five children. Pediatr Dermatol. 2000;17:7-11.

- Scarfì F, Arunachalam M, Galeone M, et al. An uncommon onychomadesis in adults. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:1392-1394.

- Osterback R, Vuorinen T, Linna M, et al. Coxsackievirus A6 and hand, foot, and mouth disease, Finland. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15:1485-1488.

- Yan X, Zhang ZZ, Yang ZH, et al. Clinical and etiological characteristics of atypical hand-foot-and-mouth disease in children from Chongqing, China: a retrospective study [published online November 26, 2015]. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:802046.

- Wei SH, Huang YP, Liu MC, et al. An outbreak of coxsackievirus A6 hand, foot, and mouth disease associated with onychomadesis in Taiwan, 2010. BMC Infect Dis. 2011;11:346.

- Guimbao J, Rodrigo P, Alberto MJ, et al. Onychomadesis outbreak linked to hand, foot, and mouth disease, Spain, July 2008. Euro Surveill. 2010;15:19663.

- Cabrerizo M, De Miguel T, Armada A, et al. Onychomadesis after a hand, foot, and mouth disease outbreak in Spain, 2009. Epidemiol Infect. 2010;138:1775-1778.

- Podder I, Das A, Gharami RC. Onychomadesis following varicella infection: is it a mere co-incidence? Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:626-627.

- Piraccini BM, Iorizzo M, Tosti A. Drug-induced nail abnormalities. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2003;4:31-37.

- Poretti A, Lips U, Belvedere M, et al. Onychomadesis: a rare side-effect of valproic acid medication? Pediatr Dermatol. 2009;26:749-750.

- Grech V, Vella C. Generalized onycholoysis associated with sodium valproate therapy. Eur Neurol. 1999;42:64-65.

- Shah RK, Uddin M, Fatunde OJ. Onychomadesis secondary to penicillin allergy in a child. J Pediatr. 2012;161:166.

- Haneke E. Onychomadesis and hand, foot and mouth disease—is there a connection? Euro Surveill. 2010;15(37).

- Bettoli V, Zauli S, Toni G, et al. Onychomadesis following hand, foot, and mouth disease: a case report from Italy and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:728-730.

- Wortsman X, Wortsman J, Guerrero R, et al. Anatomical changes in retronychia and onychomadesis detected using ultrasound. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:1615-1620.

- Fleming CJ, Hunt MJ, Barnetson RS. Mycosis fungoides with onychomadesis. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135:1012-1013.

- Mishra D, Singh G, Pandey SS. Possible carbamazepine-induced reversible onychomadesis. Int J Dermatol. 1989;28:460-461.

Practice Points

- Onychomadesis in a child may be a cutaneous sign of systemic disease.

- In childhood, onychomadesis is sometimes linked with hand-foot-and-mouth disease.

- Spontaneous nail regrowth usually occurs within 12 weeks but may occur faster in children.