User login

A less common source of dyspnea in scleroderma

A 48-year-old man reports progressive exercise intolerance, shortness of breath, fatigue, and melena over the past month. He has a long history of Raynaud phenomenon, and 5 months ago he developed severe sclerodactyly in both hands, diagnosed as limited cutaneous systemic sclerosis (scleroderma).

He has no chest pain, swelling of the lower limbs, change in weight, cough, fever, chills, or sick contacts, and he has not traveled recently.

His symptoms began as fatigue and shortness of breath, which worsened until he began having episodes of abdominal pain with melena and dizzy spills, although he never passed out.

He is currently taking long-term low-dose prednisone and mycophenolate mofetil (Cell-Cept) for the systemic sclerosis, and omeprazole (Prilosec) for gastroesophageal reflux. His father had lupus, and his grandmother had colon cancer.

An outpatient workup for sclerosis-related lung and heart involvement is negative. The workup includes computed tomography of the chest, pulmonary function tests, and Doppler echocardiography.

He is afebrile, with a blood pressure of 105/60 mm Hg and a pulse of 98. His cardiopulmonary examination results are normal. He has mild epigastric tenderness without rebound or guarding. His hemoglobin concentration at the time of hospital admission is 7.8 g/dL, down from 14.5 g/dL recorded when limited cutaneous systemic sclerosis was diagnosed. Iron studies reveal iron deficiency.

The antral ectasia is treated with argon plasma coagulation during the endoscopic examination.

Afterward, the patient's hemoglobin stabilizes, and the melena resolves. He is discharged on an oral proton pump inhibitor, with instructions to follow up for another endoscopic session in 1 month.

GASTROINTESTINAL FEATURES OF SYSTEMIC SCLEROSIS

Sclerodermal disorders have diverse manifestations that always include characteristic cutaneous signs. While there are several well-recognized symptomatic conditions commonly associated with scleroderma, attention must also be paid to the less common causes of these symptoms. Scleroderma has gastrointestinal complications that can easily be missed and may not respond to immunomodulatory or proton pump inhibitor therapy: complications can include esophageal dysmotility, hypomotility, gastric paresis, reflux esophagitis, strictures, drug-related ulcer, malabsorption, bacterial overgrowth, and pseudo-obstruction.1

This patient had an underrecognized cause of dyspnea in the setting of systemic sclerosis. Vascular symptoms of limited cutaneous systemic sclerosis are typically attributed to Raynaud phenomenon; gastrointestinal symptoms are typically attributed to esophageal dysmotility; and associated dyspnea is often considered to represent pulmonary or cardiac involvement of the sclerosis. However, gastric antral vascular ectasia should be considered in any patient with scleroderma and evidence of anemia.

The prevalence of gastric antral vascular ectasia in patients with systemic sclerosis is estimated to be about 6%.2–4 It is a relatively rare cause of upper gastrointestinal blood loss that can be clinically silent until the patient develops severe iron deficiency anemia and symptoms of dyspnea, fatigue, or congestive heart failure.

Gastric antral vascular ectasia in scleroderma usually presents as iron deficiency anemia, and only presents overtly as hematemesis or melena 10% to 14% of the time.4 Because of the often occult nature of the bleeding, the condition may be clinically silent in the early phase. Symptoms of shortness of breath and fatigue may not develop until the anemia worsens rapidly or becomes severe. Anemia is present in almost all cases of gastric antral vascular ectasia (96% to 100%) and should be a strong clinical clue for early endoscopic evaluation in patients with scleroderma, especially if there is already suspicion of upper gastrointestinal bleeding.2–5

The distinctive endoscopic streaky pattern of ectasia along the stomach antrum seen in gastric antral vascular ectasia is called “watermelon stomach”4,5 because the striped pattern recalls the stripes of a watermelon. The endoscopic appearance can vary, however, from the watermelon pattern to a coalescence of angiodysplastic lesions termed “honeycomb stomach,” which can easily be mistaken for antral gastritis.4,5 Therefore, biopsy often serves to confirm the diagnosis, with histologic features including dilated mucosal capillaries with focal fibrin thrombosis and fibromuscular hyperplasia of the lamina propria.

Gastric antral vascular ectasia often requires multiple transfusions of red blood cells, as well as repeated treatments with endoscopic argon plasma coagulation, whereby ionized argon gas is used to conduct an electric current that coagulates the surface of the mucosa to a few millimeters depth.4–6

A knowledge of the association between scleroderma and gastric antral vascular ectasia can lead to earlier recognition and treatment and can avoid unnecessary testing and complications of severe anemia.

- Forbes A, Marie I. Gastrointestinal complications: the most frequent internal complications of systemic sclerosis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2009; 48(suppl 3):iii36–iii39.

- Ingraham KM, O’Brien MS, Shenin M, Derk CT, Steen VD. Gastric antral vascular ectasia in systemic sclerosis: demographics and disease predictors. J Rheumatol 2010; 37:603–607.

- Watson M, Hally RJ, McCue PA, Varga J, Jiménez SA. Gastric antral vascular ectasia (watermelon stomach) in patients with systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Rheum 1996; 39:341–346.

- Marie I, Ducrotte P, Antonietti M, Herve S, Levesque H. Watermelon stomach in systemic sclerosis: its incidence and management. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2008; 28:412–421.

- Selinger CP, Ang YS. Gastric antral vascular ectasia (GAVE): an update on clinical presentation, pathophysiology and treatment. Digestion 2008; 77:131–137.

- Chaves DM, Sakai P, Oliveira CV, Cheng S, Ishioka S. Watermelon stomach: clinical aspects and treatment with argon plasma coagulation. Arq Gastroenterol 2006; 43:191–195.

A 48-year-old man reports progressive exercise intolerance, shortness of breath, fatigue, and melena over the past month. He has a long history of Raynaud phenomenon, and 5 months ago he developed severe sclerodactyly in both hands, diagnosed as limited cutaneous systemic sclerosis (scleroderma).

He has no chest pain, swelling of the lower limbs, change in weight, cough, fever, chills, or sick contacts, and he has not traveled recently.

His symptoms began as fatigue and shortness of breath, which worsened until he began having episodes of abdominal pain with melena and dizzy spills, although he never passed out.

He is currently taking long-term low-dose prednisone and mycophenolate mofetil (Cell-Cept) for the systemic sclerosis, and omeprazole (Prilosec) for gastroesophageal reflux. His father had lupus, and his grandmother had colon cancer.

An outpatient workup for sclerosis-related lung and heart involvement is negative. The workup includes computed tomography of the chest, pulmonary function tests, and Doppler echocardiography.

He is afebrile, with a blood pressure of 105/60 mm Hg and a pulse of 98. His cardiopulmonary examination results are normal. He has mild epigastric tenderness without rebound or guarding. His hemoglobin concentration at the time of hospital admission is 7.8 g/dL, down from 14.5 g/dL recorded when limited cutaneous systemic sclerosis was diagnosed. Iron studies reveal iron deficiency.

The antral ectasia is treated with argon plasma coagulation during the endoscopic examination.

Afterward, the patient's hemoglobin stabilizes, and the melena resolves. He is discharged on an oral proton pump inhibitor, with instructions to follow up for another endoscopic session in 1 month.

GASTROINTESTINAL FEATURES OF SYSTEMIC SCLEROSIS

Sclerodermal disorders have diverse manifestations that always include characteristic cutaneous signs. While there are several well-recognized symptomatic conditions commonly associated with scleroderma, attention must also be paid to the less common causes of these symptoms. Scleroderma has gastrointestinal complications that can easily be missed and may not respond to immunomodulatory or proton pump inhibitor therapy: complications can include esophageal dysmotility, hypomotility, gastric paresis, reflux esophagitis, strictures, drug-related ulcer, malabsorption, bacterial overgrowth, and pseudo-obstruction.1

This patient had an underrecognized cause of dyspnea in the setting of systemic sclerosis. Vascular symptoms of limited cutaneous systemic sclerosis are typically attributed to Raynaud phenomenon; gastrointestinal symptoms are typically attributed to esophageal dysmotility; and associated dyspnea is often considered to represent pulmonary or cardiac involvement of the sclerosis. However, gastric antral vascular ectasia should be considered in any patient with scleroderma and evidence of anemia.

The prevalence of gastric antral vascular ectasia in patients with systemic sclerosis is estimated to be about 6%.2–4 It is a relatively rare cause of upper gastrointestinal blood loss that can be clinically silent until the patient develops severe iron deficiency anemia and symptoms of dyspnea, fatigue, or congestive heart failure.

Gastric antral vascular ectasia in scleroderma usually presents as iron deficiency anemia, and only presents overtly as hematemesis or melena 10% to 14% of the time.4 Because of the often occult nature of the bleeding, the condition may be clinically silent in the early phase. Symptoms of shortness of breath and fatigue may not develop until the anemia worsens rapidly or becomes severe. Anemia is present in almost all cases of gastric antral vascular ectasia (96% to 100%) and should be a strong clinical clue for early endoscopic evaluation in patients with scleroderma, especially if there is already suspicion of upper gastrointestinal bleeding.2–5

The distinctive endoscopic streaky pattern of ectasia along the stomach antrum seen in gastric antral vascular ectasia is called “watermelon stomach”4,5 because the striped pattern recalls the stripes of a watermelon. The endoscopic appearance can vary, however, from the watermelon pattern to a coalescence of angiodysplastic lesions termed “honeycomb stomach,” which can easily be mistaken for antral gastritis.4,5 Therefore, biopsy often serves to confirm the diagnosis, with histologic features including dilated mucosal capillaries with focal fibrin thrombosis and fibromuscular hyperplasia of the lamina propria.

Gastric antral vascular ectasia often requires multiple transfusions of red blood cells, as well as repeated treatments with endoscopic argon plasma coagulation, whereby ionized argon gas is used to conduct an electric current that coagulates the surface of the mucosa to a few millimeters depth.4–6

A knowledge of the association between scleroderma and gastric antral vascular ectasia can lead to earlier recognition and treatment and can avoid unnecessary testing and complications of severe anemia.

A 48-year-old man reports progressive exercise intolerance, shortness of breath, fatigue, and melena over the past month. He has a long history of Raynaud phenomenon, and 5 months ago he developed severe sclerodactyly in both hands, diagnosed as limited cutaneous systemic sclerosis (scleroderma).

He has no chest pain, swelling of the lower limbs, change in weight, cough, fever, chills, or sick contacts, and he has not traveled recently.

His symptoms began as fatigue and shortness of breath, which worsened until he began having episodes of abdominal pain with melena and dizzy spills, although he never passed out.

He is currently taking long-term low-dose prednisone and mycophenolate mofetil (Cell-Cept) for the systemic sclerosis, and omeprazole (Prilosec) for gastroesophageal reflux. His father had lupus, and his grandmother had colon cancer.

An outpatient workup for sclerosis-related lung and heart involvement is negative. The workup includes computed tomography of the chest, pulmonary function tests, and Doppler echocardiography.

He is afebrile, with a blood pressure of 105/60 mm Hg and a pulse of 98. His cardiopulmonary examination results are normal. He has mild epigastric tenderness without rebound or guarding. His hemoglobin concentration at the time of hospital admission is 7.8 g/dL, down from 14.5 g/dL recorded when limited cutaneous systemic sclerosis was diagnosed. Iron studies reveal iron deficiency.

The antral ectasia is treated with argon plasma coagulation during the endoscopic examination.

Afterward, the patient's hemoglobin stabilizes, and the melena resolves. He is discharged on an oral proton pump inhibitor, with instructions to follow up for another endoscopic session in 1 month.

GASTROINTESTINAL FEATURES OF SYSTEMIC SCLEROSIS

Sclerodermal disorders have diverse manifestations that always include characteristic cutaneous signs. While there are several well-recognized symptomatic conditions commonly associated with scleroderma, attention must also be paid to the less common causes of these symptoms. Scleroderma has gastrointestinal complications that can easily be missed and may not respond to immunomodulatory or proton pump inhibitor therapy: complications can include esophageal dysmotility, hypomotility, gastric paresis, reflux esophagitis, strictures, drug-related ulcer, malabsorption, bacterial overgrowth, and pseudo-obstruction.1

This patient had an underrecognized cause of dyspnea in the setting of systemic sclerosis. Vascular symptoms of limited cutaneous systemic sclerosis are typically attributed to Raynaud phenomenon; gastrointestinal symptoms are typically attributed to esophageal dysmotility; and associated dyspnea is often considered to represent pulmonary or cardiac involvement of the sclerosis. However, gastric antral vascular ectasia should be considered in any patient with scleroderma and evidence of anemia.

The prevalence of gastric antral vascular ectasia in patients with systemic sclerosis is estimated to be about 6%.2–4 It is a relatively rare cause of upper gastrointestinal blood loss that can be clinically silent until the patient develops severe iron deficiency anemia and symptoms of dyspnea, fatigue, or congestive heart failure.

Gastric antral vascular ectasia in scleroderma usually presents as iron deficiency anemia, and only presents overtly as hematemesis or melena 10% to 14% of the time.4 Because of the often occult nature of the bleeding, the condition may be clinically silent in the early phase. Symptoms of shortness of breath and fatigue may not develop until the anemia worsens rapidly or becomes severe. Anemia is present in almost all cases of gastric antral vascular ectasia (96% to 100%) and should be a strong clinical clue for early endoscopic evaluation in patients with scleroderma, especially if there is already suspicion of upper gastrointestinal bleeding.2–5

The distinctive endoscopic streaky pattern of ectasia along the stomach antrum seen in gastric antral vascular ectasia is called “watermelon stomach”4,5 because the striped pattern recalls the stripes of a watermelon. The endoscopic appearance can vary, however, from the watermelon pattern to a coalescence of angiodysplastic lesions termed “honeycomb stomach,” which can easily be mistaken for antral gastritis.4,5 Therefore, biopsy often serves to confirm the diagnosis, with histologic features including dilated mucosal capillaries with focal fibrin thrombosis and fibromuscular hyperplasia of the lamina propria.

Gastric antral vascular ectasia often requires multiple transfusions of red blood cells, as well as repeated treatments with endoscopic argon plasma coagulation, whereby ionized argon gas is used to conduct an electric current that coagulates the surface of the mucosa to a few millimeters depth.4–6

A knowledge of the association between scleroderma and gastric antral vascular ectasia can lead to earlier recognition and treatment and can avoid unnecessary testing and complications of severe anemia.

- Forbes A, Marie I. Gastrointestinal complications: the most frequent internal complications of systemic sclerosis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2009; 48(suppl 3):iii36–iii39.

- Ingraham KM, O’Brien MS, Shenin M, Derk CT, Steen VD. Gastric antral vascular ectasia in systemic sclerosis: demographics and disease predictors. J Rheumatol 2010; 37:603–607.

- Watson M, Hally RJ, McCue PA, Varga J, Jiménez SA. Gastric antral vascular ectasia (watermelon stomach) in patients with systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Rheum 1996; 39:341–346.

- Marie I, Ducrotte P, Antonietti M, Herve S, Levesque H. Watermelon stomach in systemic sclerosis: its incidence and management. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2008; 28:412–421.

- Selinger CP, Ang YS. Gastric antral vascular ectasia (GAVE): an update on clinical presentation, pathophysiology and treatment. Digestion 2008; 77:131–137.

- Chaves DM, Sakai P, Oliveira CV, Cheng S, Ishioka S. Watermelon stomach: clinical aspects and treatment with argon plasma coagulation. Arq Gastroenterol 2006; 43:191–195.

- Forbes A, Marie I. Gastrointestinal complications: the most frequent internal complications of systemic sclerosis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2009; 48(suppl 3):iii36–iii39.

- Ingraham KM, O’Brien MS, Shenin M, Derk CT, Steen VD. Gastric antral vascular ectasia in systemic sclerosis: demographics and disease predictors. J Rheumatol 2010; 37:603–607.

- Watson M, Hally RJ, McCue PA, Varga J, Jiménez SA. Gastric antral vascular ectasia (watermelon stomach) in patients with systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Rheum 1996; 39:341–346.

- Marie I, Ducrotte P, Antonietti M, Herve S, Levesque H. Watermelon stomach in systemic sclerosis: its incidence and management. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2008; 28:412–421.

- Selinger CP, Ang YS. Gastric antral vascular ectasia (GAVE): an update on clinical presentation, pathophysiology and treatment. Digestion 2008; 77:131–137.

- Chaves DM, Sakai P, Oliveira CV, Cheng S, Ishioka S. Watermelon stomach: clinical aspects and treatment with argon plasma coagulation. Arq Gastroenterol 2006; 43:191–195.

Unmasking gastric cancer

A 50-year-old male Japanese immigrant with a history of smoking and occasional untreated heartburn presented with the recent onset of flank pain, weight loss, headache, syncope, and blurred vision.

Previously healthy, he began feeling moderate pain in his left flank 1 month ago; it was diagnosed as kidney stones and was treated conservatively. Two weeks later he had an episode of syncope and soon after developed blurred vision, mainly in his left eye, along with severe bifrontal headache. An eye examination and magnetic resonance imaging of the brain indicated optic neuritis, for which he was given glucocorticoids intravenously for 3 days, with moderate improvement.

As his symptoms continued over the next 2 weeks, he lost 20 lb (9.1 kg) due to the pain, loss of appetite, nausea, and occasional vomiting.

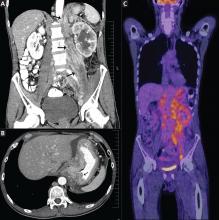

Positron emission tomography showed the retroperitoneal infiltrative process and the thickened gastric cardia to be hypermetabolic (Figure 1C).

The area of retroperitoneal infiltration was biopsied under CT guidance, and pathologic study showed poorly differentiated carcinoma with signet-ring cells, a feature of gastric cancer.

The patient underwent lumbar puncture. His cerebrospinal fluid had 206 white blood cells/μL (reference range 0–5) and large numbers of poorly differentiated malignant cells, most consistent with adenocarcinoma on cytologic study.

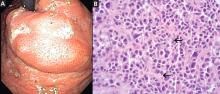

duodenoscopy (EGD) revealed a large, ulcerated, submucosal, nodular mass in the cardia of the stomach extending to the gastroesophageal junction (Figure 2A). Biopsy of the mass again revealed poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma with scattered signet-ring cells undermining the gastric mucosa, favoring a gastric origin (Figure 2B).

THREE SUBTYPES OF GASTRIC CANCER

Worldwide, gastric cancer is the third most common type of cancer and the second most common cause of cancer-related deaths.1 In the United States, blacks and people of Asian ancestry have almost twice the risk of death, with the highest incidence and mortality rates.2,3

Most cases of gastric adenocarcinoma can be categorized as either intestinal or diffuse, but a new proximal subtype is emerging.4

Intestinal-type gastric adenocarcinoma is the most common subtype and accounts for almost all the ethnic and geographic variation in incidence.2 The lesions are often ulcerative and distal; the pathogenesis is stepwise and is initiated by chronic inflammation. Risk factors include old age, Helicobacter pylori infection, tobacco smoking, family history, and high salt intake, with an observed risk-reduction with the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and with a high intake of fruits and vegetables.3

Diffuse gastric adenocarcinoma, on the other hand, has a uniform distribution worldwide, and its incidence is increasing. It typically carries a poor prognosis. Evidence thus far has shown its pathogenesis to be independent of chronic inflammation, but it has a strong tendency to be hereditary.3

Proximal gastric adenocarcinoma is observed in the gastric cardia and near the gastroesophageal junction. It is often grouped with the distal esophageal adenocarcinomas and has similar risk factors, including reflux disease, obesity, alcohol abuse, and tobacco smoking. Interestingly, however, H pylori infection does not contribute to the pathogenesis of this type, and it may even have a protective role.3

DIFFICULT TO DETECT EARLY

Gastric cancer is difficult to detect early enough in its course to be cured. Understanding its risk factors, recognizing its common symptoms, and regarding its uncommon symptoms with suspicion may lead to earlier diagnosis and more effective treatment.

Our patient’s proximal gastric cancer was diagnosed late even though he had several risk factors for it (he was Japanese, he was a smoker, and he had gastroesophageal reflux disease) because of a late and atypical presentation with misleading paraneoplastic symptoms.

Early diagnosis is difficult because most patients have no symptoms in the early stage; weight loss and abdominal pain are often late signs of tumor progression.

Screening may be justified in high-risk groups in the United States, although the issue is debatable. Diagnostic imaging is the only effective method for screening,5 with EGD considered the first-line targeted evaluation should there be suspicion of gastric cancer either from the clinical presentation or from barium swallow.6 Candidates for screening may include elderly patients with atrophic gastritis or pernicious anemia, immigrants from countries with high rates of gastric carcinoma, and people with a family history of gastrointestinal cancer.7

- Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, Pisani P. Global cancer statistics, 2002. CA Cancer J Clin 2005; 55:74–108.

- Crew KD, Neugut AI. Epidemiology of gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol 2006; 12:354–362.

- Shah MA, Kelsen DP. Gastric cancer: a primer on the epidemiology and biology of the disease and an overview of the medical management of advanced disease. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2010; 8:437–447.

- Fine G, Chan K. Alimentary tract. In:Kissane JM, editor. Anderson’s Pathology. 8th ed. Saint Louis, MO: Mosby; 1985:1055–1095.

- Kunisaki C, Ishino J, Nakajima S, et al. Outcomes of mass screening for gastric carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol 2006; 13:221–228.

- Cappell MS, Friedel D. The role of esophagogastroduodenoscopy in the diagnosis and management of upper gastrointestinal disorders. Med Clin North Am 2002; 86:1165–1216.

- Hisamuchi S, Fukao P, Sugawara N, et al. Evaluation of mass screening programme for stomach cancer in Japan. In:Miller AB, Chamberlain J, Day NE, et al, editors. Cancer Screening. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 1991:357–372.

A 50-year-old male Japanese immigrant with a history of smoking and occasional untreated heartburn presented with the recent onset of flank pain, weight loss, headache, syncope, and blurred vision.

Previously healthy, he began feeling moderate pain in his left flank 1 month ago; it was diagnosed as kidney stones and was treated conservatively. Two weeks later he had an episode of syncope and soon after developed blurred vision, mainly in his left eye, along with severe bifrontal headache. An eye examination and magnetic resonance imaging of the brain indicated optic neuritis, for which he was given glucocorticoids intravenously for 3 days, with moderate improvement.

As his symptoms continued over the next 2 weeks, he lost 20 lb (9.1 kg) due to the pain, loss of appetite, nausea, and occasional vomiting.

Positron emission tomography showed the retroperitoneal infiltrative process and the thickened gastric cardia to be hypermetabolic (Figure 1C).

The area of retroperitoneal infiltration was biopsied under CT guidance, and pathologic study showed poorly differentiated carcinoma with signet-ring cells, a feature of gastric cancer.

The patient underwent lumbar puncture. His cerebrospinal fluid had 206 white blood cells/μL (reference range 0–5) and large numbers of poorly differentiated malignant cells, most consistent with adenocarcinoma on cytologic study.

duodenoscopy (EGD) revealed a large, ulcerated, submucosal, nodular mass in the cardia of the stomach extending to the gastroesophageal junction (Figure 2A). Biopsy of the mass again revealed poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma with scattered signet-ring cells undermining the gastric mucosa, favoring a gastric origin (Figure 2B).

THREE SUBTYPES OF GASTRIC CANCER

Worldwide, gastric cancer is the third most common type of cancer and the second most common cause of cancer-related deaths.1 In the United States, blacks and people of Asian ancestry have almost twice the risk of death, with the highest incidence and mortality rates.2,3

Most cases of gastric adenocarcinoma can be categorized as either intestinal or diffuse, but a new proximal subtype is emerging.4

Intestinal-type gastric adenocarcinoma is the most common subtype and accounts for almost all the ethnic and geographic variation in incidence.2 The lesions are often ulcerative and distal; the pathogenesis is stepwise and is initiated by chronic inflammation. Risk factors include old age, Helicobacter pylori infection, tobacco smoking, family history, and high salt intake, with an observed risk-reduction with the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and with a high intake of fruits and vegetables.3

Diffuse gastric adenocarcinoma, on the other hand, has a uniform distribution worldwide, and its incidence is increasing. It typically carries a poor prognosis. Evidence thus far has shown its pathogenesis to be independent of chronic inflammation, but it has a strong tendency to be hereditary.3

Proximal gastric adenocarcinoma is observed in the gastric cardia and near the gastroesophageal junction. It is often grouped with the distal esophageal adenocarcinomas and has similar risk factors, including reflux disease, obesity, alcohol abuse, and tobacco smoking. Interestingly, however, H pylori infection does not contribute to the pathogenesis of this type, and it may even have a protective role.3

DIFFICULT TO DETECT EARLY

Gastric cancer is difficult to detect early enough in its course to be cured. Understanding its risk factors, recognizing its common symptoms, and regarding its uncommon symptoms with suspicion may lead to earlier diagnosis and more effective treatment.

Our patient’s proximal gastric cancer was diagnosed late even though he had several risk factors for it (he was Japanese, he was a smoker, and he had gastroesophageal reflux disease) because of a late and atypical presentation with misleading paraneoplastic symptoms.

Early diagnosis is difficult because most patients have no symptoms in the early stage; weight loss and abdominal pain are often late signs of tumor progression.

Screening may be justified in high-risk groups in the United States, although the issue is debatable. Diagnostic imaging is the only effective method for screening,5 with EGD considered the first-line targeted evaluation should there be suspicion of gastric cancer either from the clinical presentation or from barium swallow.6 Candidates for screening may include elderly patients with atrophic gastritis or pernicious anemia, immigrants from countries with high rates of gastric carcinoma, and people with a family history of gastrointestinal cancer.7

A 50-year-old male Japanese immigrant with a history of smoking and occasional untreated heartburn presented with the recent onset of flank pain, weight loss, headache, syncope, and blurred vision.

Previously healthy, he began feeling moderate pain in his left flank 1 month ago; it was diagnosed as kidney stones and was treated conservatively. Two weeks later he had an episode of syncope and soon after developed blurred vision, mainly in his left eye, along with severe bifrontal headache. An eye examination and magnetic resonance imaging of the brain indicated optic neuritis, for which he was given glucocorticoids intravenously for 3 days, with moderate improvement.

As his symptoms continued over the next 2 weeks, he lost 20 lb (9.1 kg) due to the pain, loss of appetite, nausea, and occasional vomiting.

Positron emission tomography showed the retroperitoneal infiltrative process and the thickened gastric cardia to be hypermetabolic (Figure 1C).

The area of retroperitoneal infiltration was biopsied under CT guidance, and pathologic study showed poorly differentiated carcinoma with signet-ring cells, a feature of gastric cancer.

The patient underwent lumbar puncture. His cerebrospinal fluid had 206 white blood cells/μL (reference range 0–5) and large numbers of poorly differentiated malignant cells, most consistent with adenocarcinoma on cytologic study.

duodenoscopy (EGD) revealed a large, ulcerated, submucosal, nodular mass in the cardia of the stomach extending to the gastroesophageal junction (Figure 2A). Biopsy of the mass again revealed poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma with scattered signet-ring cells undermining the gastric mucosa, favoring a gastric origin (Figure 2B).

THREE SUBTYPES OF GASTRIC CANCER

Worldwide, gastric cancer is the third most common type of cancer and the second most common cause of cancer-related deaths.1 In the United States, blacks and people of Asian ancestry have almost twice the risk of death, with the highest incidence and mortality rates.2,3

Most cases of gastric adenocarcinoma can be categorized as either intestinal or diffuse, but a new proximal subtype is emerging.4

Intestinal-type gastric adenocarcinoma is the most common subtype and accounts for almost all the ethnic and geographic variation in incidence.2 The lesions are often ulcerative and distal; the pathogenesis is stepwise and is initiated by chronic inflammation. Risk factors include old age, Helicobacter pylori infection, tobacco smoking, family history, and high salt intake, with an observed risk-reduction with the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and with a high intake of fruits and vegetables.3

Diffuse gastric adenocarcinoma, on the other hand, has a uniform distribution worldwide, and its incidence is increasing. It typically carries a poor prognosis. Evidence thus far has shown its pathogenesis to be independent of chronic inflammation, but it has a strong tendency to be hereditary.3

Proximal gastric adenocarcinoma is observed in the gastric cardia and near the gastroesophageal junction. It is often grouped with the distal esophageal adenocarcinomas and has similar risk factors, including reflux disease, obesity, alcohol abuse, and tobacco smoking. Interestingly, however, H pylori infection does not contribute to the pathogenesis of this type, and it may even have a protective role.3

DIFFICULT TO DETECT EARLY

Gastric cancer is difficult to detect early enough in its course to be cured. Understanding its risk factors, recognizing its common symptoms, and regarding its uncommon symptoms with suspicion may lead to earlier diagnosis and more effective treatment.

Our patient’s proximal gastric cancer was diagnosed late even though he had several risk factors for it (he was Japanese, he was a smoker, and he had gastroesophageal reflux disease) because of a late and atypical presentation with misleading paraneoplastic symptoms.

Early diagnosis is difficult because most patients have no symptoms in the early stage; weight loss and abdominal pain are often late signs of tumor progression.

Screening may be justified in high-risk groups in the United States, although the issue is debatable. Diagnostic imaging is the only effective method for screening,5 with EGD considered the first-line targeted evaluation should there be suspicion of gastric cancer either from the clinical presentation or from barium swallow.6 Candidates for screening may include elderly patients with atrophic gastritis or pernicious anemia, immigrants from countries with high rates of gastric carcinoma, and people with a family history of gastrointestinal cancer.7

- Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, Pisani P. Global cancer statistics, 2002. CA Cancer J Clin 2005; 55:74–108.

- Crew KD, Neugut AI. Epidemiology of gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol 2006; 12:354–362.

- Shah MA, Kelsen DP. Gastric cancer: a primer on the epidemiology and biology of the disease and an overview of the medical management of advanced disease. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2010; 8:437–447.

- Fine G, Chan K. Alimentary tract. In:Kissane JM, editor. Anderson’s Pathology. 8th ed. Saint Louis, MO: Mosby; 1985:1055–1095.

- Kunisaki C, Ishino J, Nakajima S, et al. Outcomes of mass screening for gastric carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol 2006; 13:221–228.

- Cappell MS, Friedel D. The role of esophagogastroduodenoscopy in the diagnosis and management of upper gastrointestinal disorders. Med Clin North Am 2002; 86:1165–1216.

- Hisamuchi S, Fukao P, Sugawara N, et al. Evaluation of mass screening programme for stomach cancer in Japan. In:Miller AB, Chamberlain J, Day NE, et al, editors. Cancer Screening. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 1991:357–372.

- Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, Pisani P. Global cancer statistics, 2002. CA Cancer J Clin 2005; 55:74–108.

- Crew KD, Neugut AI. Epidemiology of gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol 2006; 12:354–362.

- Shah MA, Kelsen DP. Gastric cancer: a primer on the epidemiology and biology of the disease and an overview of the medical management of advanced disease. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2010; 8:437–447.

- Fine G, Chan K. Alimentary tract. In:Kissane JM, editor. Anderson’s Pathology. 8th ed. Saint Louis, MO: Mosby; 1985:1055–1095.

- Kunisaki C, Ishino J, Nakajima S, et al. Outcomes of mass screening for gastric carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol 2006; 13:221–228.

- Cappell MS, Friedel D. The role of esophagogastroduodenoscopy in the diagnosis and management of upper gastrointestinal disorders. Med Clin North Am 2002; 86:1165–1216.

- Hisamuchi S, Fukao P, Sugawara N, et al. Evaluation of mass screening programme for stomach cancer in Japan. In:Miller AB, Chamberlain J, Day NE, et al, editors. Cancer Screening. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 1991:357–372.