User login

Ossification and Migration of a Nodule Following Calcium Hydroxylapatite Injection

To the Editor:

Calcium hydroxylapatite is an injectable filler approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for moderate to severe rhytides of the face and the treatment of facial lipodystrophy in patients with HIV.1 This long-lasting filler generally is well tolerated with minimal side effects; however, there have been reports of nodules or granulomatous formation following injection.2 We present a case of a migrating nodule following injection of a calcium hydroxylapatite filler that appeared ossified on radiographic imaging. We highlight this rarely reported phenomenon to increase awareness of this complication.

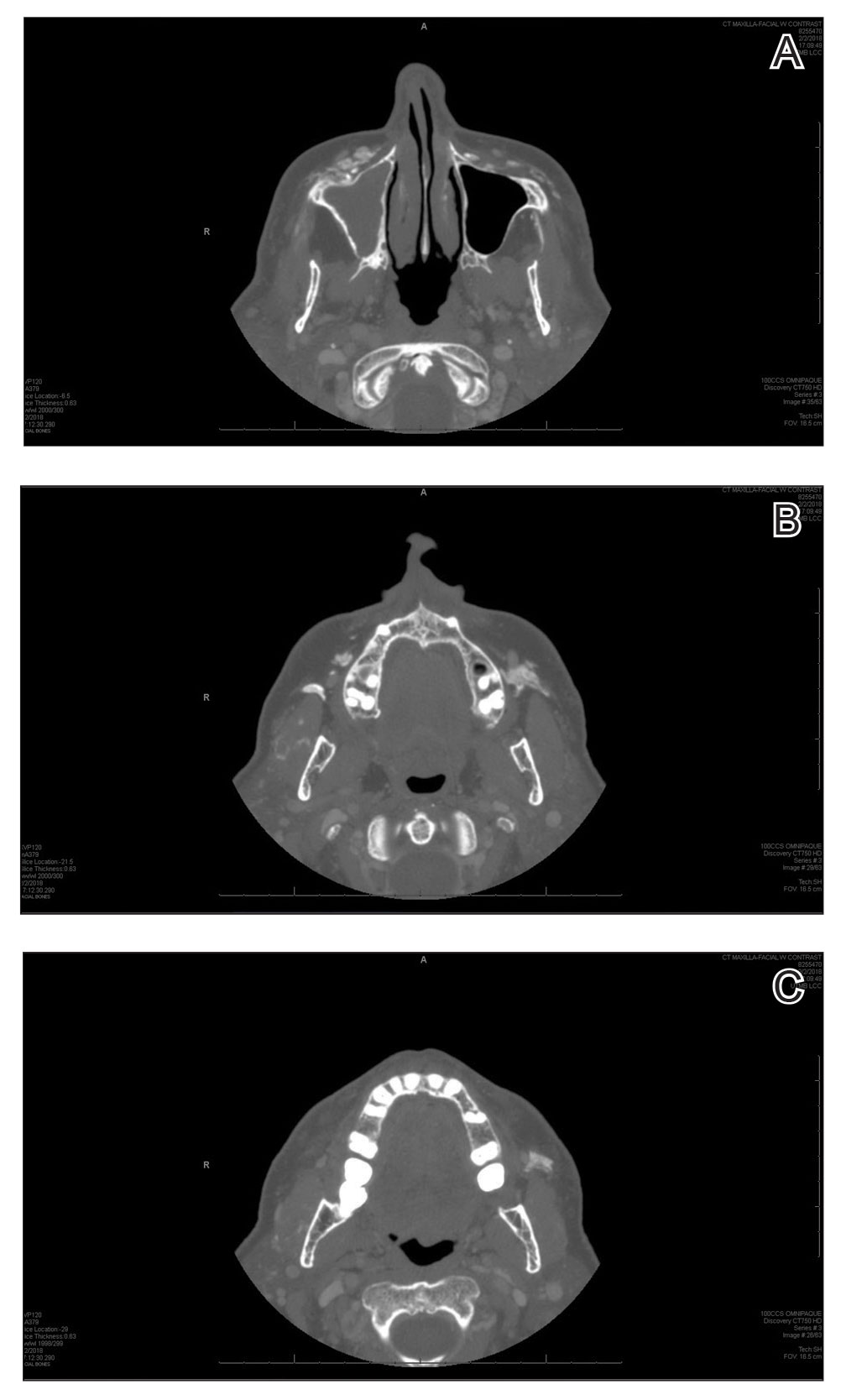

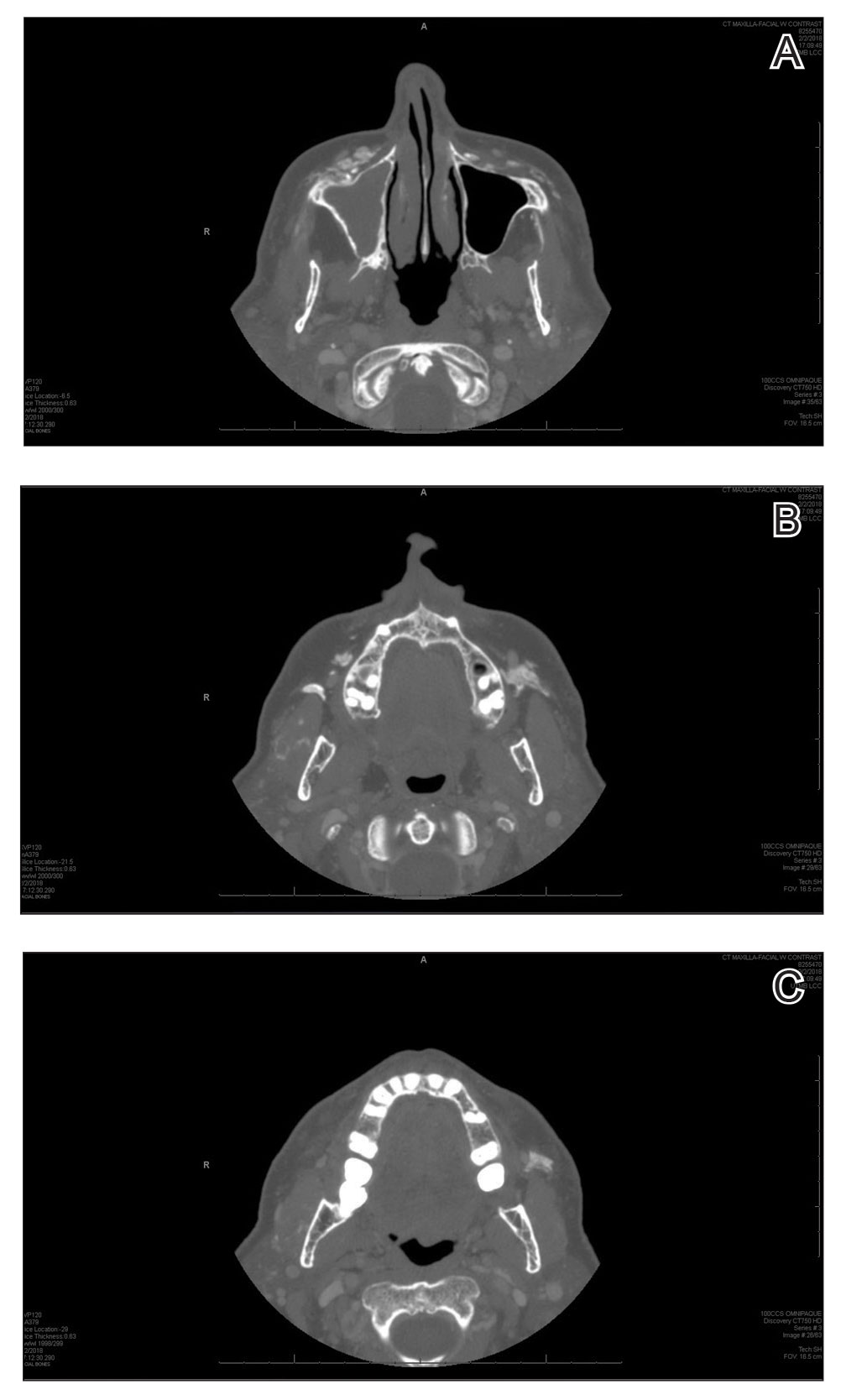

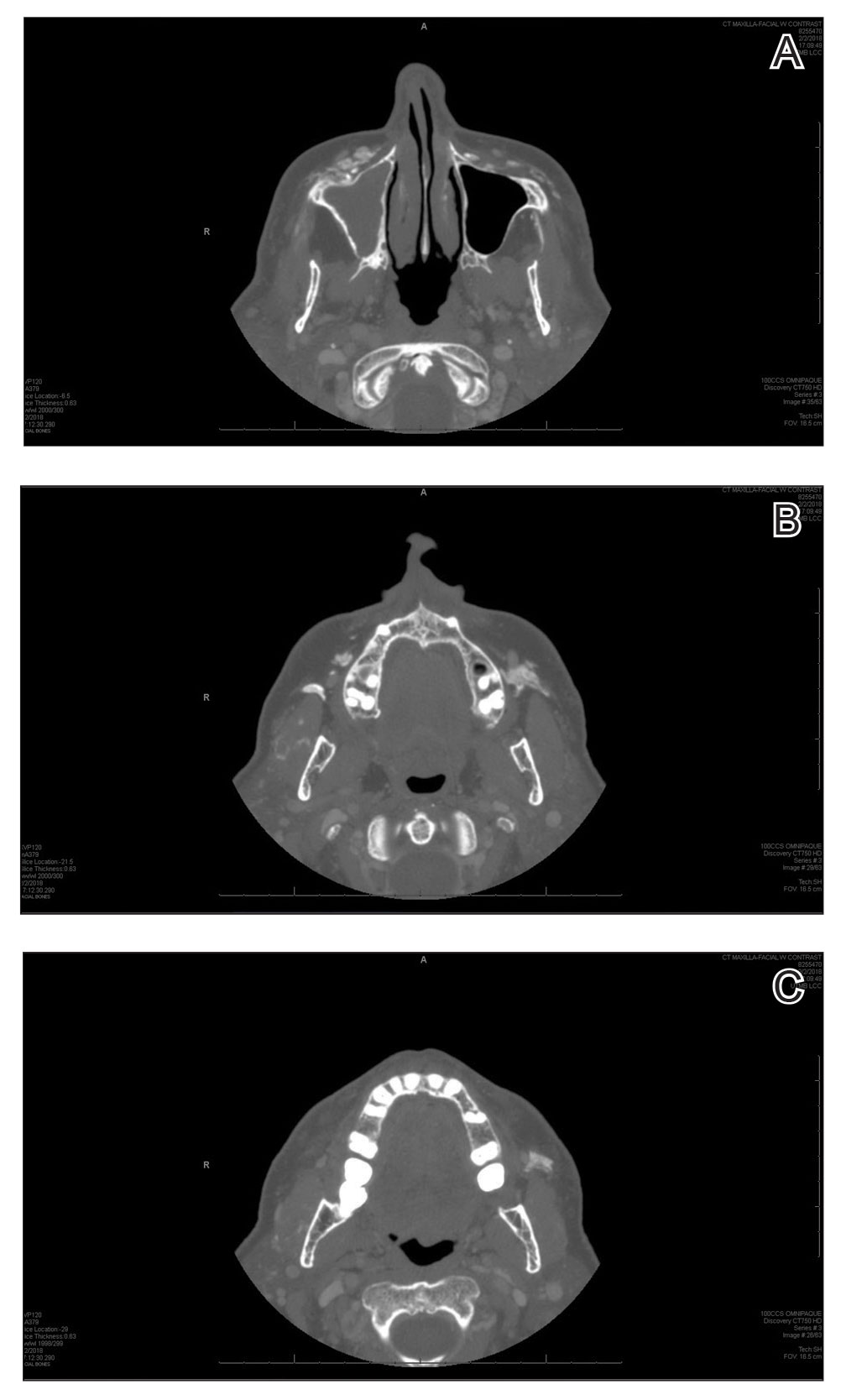

A 72-year-old woman presented to our clinic with a mass on the left cheek. The patient had a history of treatment with facial fillers but no notable medical conditions. She initially received hyaluronic acid injectable gel dermal filler twice—3 years apart—before switching to calcium hydroxylapatite injections twice—4 months apart—from an outside provider. One month after the second treatment, she noticed a mass on the left cheek and promptly returned to the provider who performed the calcium hydroxylapatite injections. The provider, who had originally injected in the infraorbital area, stated it was unlikely that the filler would have migrated to the mid cheek and referred the patient to a general dentist who suspected salivary gland pathology. The patient was referred to an oral and maxillofacial surgeon who suspected the mass was related to the parotid gland. Maxillofacial computed tomography (CT) revealed heterotopic ossification vs myositis ossificans, possibly related to the recent injection. The patient was eventually referred to the Division of Plastic Surgery, Department of Surgery, at the University of Texas Medical Branch (Galveston, Texas) for further evaluation. Physical examination revealed a 2×1-cm firm, mobile, nontender mass in the left cheek in the area of the buccinator muscles. The mass did not express any fluid and was most easily palpable from the oral cavity. Radiography findings showed that the calcium hydroxylapatite filler had migrated to this location and formed a nodule (Figure). Because calcium hydroxylapatite fillers generally last 12 to 18 months, we opted to observe the lesion for spontaneous resolution. Four months later, the patient presented to our clinic for follow-up and the mass had reduced in size and appeared to be spontaneously resolving.

We present a unique case of a migrating nodule that occurred after injection with calcium hydroxylapatite, which led to concern for neoplastic tumor formation. This complication is rare, and it is important for practitioners who inject calcium hydroxylapatite as well as those who these patients may be referred to for evaluation to be aware that migrating nodules can occur. This awareness can help reduce unnecessary referrals, medical procedures, and anxiety.

Calcium hydroxylapatite filler is composed of 30% calcium hydroxylapatite microspheres suspended in a 70% sodium carboxymethylcellulose gel. The water-soluble gel rapidly becomes absorbed upon injection; however, the microspheres form a scaffold for the production of newly synthesized collagen. The filling effect generally lasts 12 to 18 months.1

Calcium hydroxylapatite, similar to most fillers, generally is well tolerated with a low complication rate of 3%.1 Although nodule formation with calcium hydroxylapatite is rare, it is the most common adverse event and encompasses 96% of complications. The remaining 4% of complications include persistent inflammation, swelling, erythema, and technical mistakes leading to overcorrection.1 Migrating nodules are rare; however, Beer3 reported a similar case.

Treatment of calcium hydroxylapatite nodules depends on differentiating a cause based on the time of onset. Early nodules that occur within 1 to 2 weeks of the injection usually represent incorrect positioning of the filler and can be treated by massaging the nodule. Other more invasive techniques involve aspiration or injection of sterile water. Late-onset nodules have shown response to corticosteroid injections. For inflammatory nodules of infectious origin, antibiotics can be useful. Surgical excision of the nodule rarely is required, as most nodules will resolve spontaneously, even without intervention.1,2

Radiologic findings of calcium hydroxylapatite appear as high-attenuation linear streaks or masses on CT (280–700 HU) and as low to intermediate signal intensity on T1- or T2-weighted sequences on magnetic resonance imaging. Oftentimes, calcium hydroxylapatite has a similar radiographic appearance to bone and can persist for 2 years or more on radiographic imaging, longer than they are clinically visible.4 The nodule formation from injection with calcium hydroxylapatite can mimic pathologic conditions such as miliary osteomas, myositis ossificans, heterotrophic/dystrophic calcifications, and foreign bodies on CT. Our patient’s CT findings of high attenuation linear streaks and nodules of similar signal intensity to bone were consistent with those previously described in the radiographic literature.

Calcium hydroxylapatite fillers have a good safety profile, but it is important to recognize that nodule formation is a common adverse event and that migration of nodules can occur. Practitioners should recognize this possibility in patients presenting with new masses after filler injection before advocating for potentially invasive and costly procedures and diagnostic modalities.

- Kadouch JA. Calcium hydroxylapatite: a review on safety and complications. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2017;16:152-161.

- Moulinets I, Arnaud E, Bui P, et al. Foreign body reaction to Radiesse: 2 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2013;35:e37-40.

- Beer KR. Radiesse nodule of the lips from a distant injection site: report of a case and consideration of etiology and management. J Drugs Dermatol. 2007;6:846-847.

- Ginat DT, Schatz CJ. Imaging features of midface injectable fillers and associated complications. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2013;34:1488-1495.

To the Editor:

Calcium hydroxylapatite is an injectable filler approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for moderate to severe rhytides of the face and the treatment of facial lipodystrophy in patients with HIV.1 This long-lasting filler generally is well tolerated with minimal side effects; however, there have been reports of nodules or granulomatous formation following injection.2 We present a case of a migrating nodule following injection of a calcium hydroxylapatite filler that appeared ossified on radiographic imaging. We highlight this rarely reported phenomenon to increase awareness of this complication.

A 72-year-old woman presented to our clinic with a mass on the left cheek. The patient had a history of treatment with facial fillers but no notable medical conditions. She initially received hyaluronic acid injectable gel dermal filler twice—3 years apart—before switching to calcium hydroxylapatite injections twice—4 months apart—from an outside provider. One month after the second treatment, she noticed a mass on the left cheek and promptly returned to the provider who performed the calcium hydroxylapatite injections. The provider, who had originally injected in the infraorbital area, stated it was unlikely that the filler would have migrated to the mid cheek and referred the patient to a general dentist who suspected salivary gland pathology. The patient was referred to an oral and maxillofacial surgeon who suspected the mass was related to the parotid gland. Maxillofacial computed tomography (CT) revealed heterotopic ossification vs myositis ossificans, possibly related to the recent injection. The patient was eventually referred to the Division of Plastic Surgery, Department of Surgery, at the University of Texas Medical Branch (Galveston, Texas) for further evaluation. Physical examination revealed a 2×1-cm firm, mobile, nontender mass in the left cheek in the area of the buccinator muscles. The mass did not express any fluid and was most easily palpable from the oral cavity. Radiography findings showed that the calcium hydroxylapatite filler had migrated to this location and formed a nodule (Figure). Because calcium hydroxylapatite fillers generally last 12 to 18 months, we opted to observe the lesion for spontaneous resolution. Four months later, the patient presented to our clinic for follow-up and the mass had reduced in size and appeared to be spontaneously resolving.

We present a unique case of a migrating nodule that occurred after injection with calcium hydroxylapatite, which led to concern for neoplastic tumor formation. This complication is rare, and it is important for practitioners who inject calcium hydroxylapatite as well as those who these patients may be referred to for evaluation to be aware that migrating nodules can occur. This awareness can help reduce unnecessary referrals, medical procedures, and anxiety.

Calcium hydroxylapatite filler is composed of 30% calcium hydroxylapatite microspheres suspended in a 70% sodium carboxymethylcellulose gel. The water-soluble gel rapidly becomes absorbed upon injection; however, the microspheres form a scaffold for the production of newly synthesized collagen. The filling effect generally lasts 12 to 18 months.1

Calcium hydroxylapatite, similar to most fillers, generally is well tolerated with a low complication rate of 3%.1 Although nodule formation with calcium hydroxylapatite is rare, it is the most common adverse event and encompasses 96% of complications. The remaining 4% of complications include persistent inflammation, swelling, erythema, and technical mistakes leading to overcorrection.1 Migrating nodules are rare; however, Beer3 reported a similar case.

Treatment of calcium hydroxylapatite nodules depends on differentiating a cause based on the time of onset. Early nodules that occur within 1 to 2 weeks of the injection usually represent incorrect positioning of the filler and can be treated by massaging the nodule. Other more invasive techniques involve aspiration or injection of sterile water. Late-onset nodules have shown response to corticosteroid injections. For inflammatory nodules of infectious origin, antibiotics can be useful. Surgical excision of the nodule rarely is required, as most nodules will resolve spontaneously, even without intervention.1,2

Radiologic findings of calcium hydroxylapatite appear as high-attenuation linear streaks or masses on CT (280–700 HU) and as low to intermediate signal intensity on T1- or T2-weighted sequences on magnetic resonance imaging. Oftentimes, calcium hydroxylapatite has a similar radiographic appearance to bone and can persist for 2 years or more on radiographic imaging, longer than they are clinically visible.4 The nodule formation from injection with calcium hydroxylapatite can mimic pathologic conditions such as miliary osteomas, myositis ossificans, heterotrophic/dystrophic calcifications, and foreign bodies on CT. Our patient’s CT findings of high attenuation linear streaks and nodules of similar signal intensity to bone were consistent with those previously described in the radiographic literature.

Calcium hydroxylapatite fillers have a good safety profile, but it is important to recognize that nodule formation is a common adverse event and that migration of nodules can occur. Practitioners should recognize this possibility in patients presenting with new masses after filler injection before advocating for potentially invasive and costly procedures and diagnostic modalities.

To the Editor:

Calcium hydroxylapatite is an injectable filler approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for moderate to severe rhytides of the face and the treatment of facial lipodystrophy in patients with HIV.1 This long-lasting filler generally is well tolerated with minimal side effects; however, there have been reports of nodules or granulomatous formation following injection.2 We present a case of a migrating nodule following injection of a calcium hydroxylapatite filler that appeared ossified on radiographic imaging. We highlight this rarely reported phenomenon to increase awareness of this complication.

A 72-year-old woman presented to our clinic with a mass on the left cheek. The patient had a history of treatment with facial fillers but no notable medical conditions. She initially received hyaluronic acid injectable gel dermal filler twice—3 years apart—before switching to calcium hydroxylapatite injections twice—4 months apart—from an outside provider. One month after the second treatment, she noticed a mass on the left cheek and promptly returned to the provider who performed the calcium hydroxylapatite injections. The provider, who had originally injected in the infraorbital area, stated it was unlikely that the filler would have migrated to the mid cheek and referred the patient to a general dentist who suspected salivary gland pathology. The patient was referred to an oral and maxillofacial surgeon who suspected the mass was related to the parotid gland. Maxillofacial computed tomography (CT) revealed heterotopic ossification vs myositis ossificans, possibly related to the recent injection. The patient was eventually referred to the Division of Plastic Surgery, Department of Surgery, at the University of Texas Medical Branch (Galveston, Texas) for further evaluation. Physical examination revealed a 2×1-cm firm, mobile, nontender mass in the left cheek in the area of the buccinator muscles. The mass did not express any fluid and was most easily palpable from the oral cavity. Radiography findings showed that the calcium hydroxylapatite filler had migrated to this location and formed a nodule (Figure). Because calcium hydroxylapatite fillers generally last 12 to 18 months, we opted to observe the lesion for spontaneous resolution. Four months later, the patient presented to our clinic for follow-up and the mass had reduced in size and appeared to be spontaneously resolving.

We present a unique case of a migrating nodule that occurred after injection with calcium hydroxylapatite, which led to concern for neoplastic tumor formation. This complication is rare, and it is important for practitioners who inject calcium hydroxylapatite as well as those who these patients may be referred to for evaluation to be aware that migrating nodules can occur. This awareness can help reduce unnecessary referrals, medical procedures, and anxiety.

Calcium hydroxylapatite filler is composed of 30% calcium hydroxylapatite microspheres suspended in a 70% sodium carboxymethylcellulose gel. The water-soluble gel rapidly becomes absorbed upon injection; however, the microspheres form a scaffold for the production of newly synthesized collagen. The filling effect generally lasts 12 to 18 months.1

Calcium hydroxylapatite, similar to most fillers, generally is well tolerated with a low complication rate of 3%.1 Although nodule formation with calcium hydroxylapatite is rare, it is the most common adverse event and encompasses 96% of complications. The remaining 4% of complications include persistent inflammation, swelling, erythema, and technical mistakes leading to overcorrection.1 Migrating nodules are rare; however, Beer3 reported a similar case.

Treatment of calcium hydroxylapatite nodules depends on differentiating a cause based on the time of onset. Early nodules that occur within 1 to 2 weeks of the injection usually represent incorrect positioning of the filler and can be treated by massaging the nodule. Other more invasive techniques involve aspiration or injection of sterile water. Late-onset nodules have shown response to corticosteroid injections. For inflammatory nodules of infectious origin, antibiotics can be useful. Surgical excision of the nodule rarely is required, as most nodules will resolve spontaneously, even without intervention.1,2

Radiologic findings of calcium hydroxylapatite appear as high-attenuation linear streaks or masses on CT (280–700 HU) and as low to intermediate signal intensity on T1- or T2-weighted sequences on magnetic resonance imaging. Oftentimes, calcium hydroxylapatite has a similar radiographic appearance to bone and can persist for 2 years or more on radiographic imaging, longer than they are clinically visible.4 The nodule formation from injection with calcium hydroxylapatite can mimic pathologic conditions such as miliary osteomas, myositis ossificans, heterotrophic/dystrophic calcifications, and foreign bodies on CT. Our patient’s CT findings of high attenuation linear streaks and nodules of similar signal intensity to bone were consistent with those previously described in the radiographic literature.

Calcium hydroxylapatite fillers have a good safety profile, but it is important to recognize that nodule formation is a common adverse event and that migration of nodules can occur. Practitioners should recognize this possibility in patients presenting with new masses after filler injection before advocating for potentially invasive and costly procedures and diagnostic modalities.

- Kadouch JA. Calcium hydroxylapatite: a review on safety and complications. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2017;16:152-161.

- Moulinets I, Arnaud E, Bui P, et al. Foreign body reaction to Radiesse: 2 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2013;35:e37-40.

- Beer KR. Radiesse nodule of the lips from a distant injection site: report of a case and consideration of etiology and management. J Drugs Dermatol. 2007;6:846-847.

- Ginat DT, Schatz CJ. Imaging features of midface injectable fillers and associated complications. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2013;34:1488-1495.

- Kadouch JA. Calcium hydroxylapatite: a review on safety and complications. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2017;16:152-161.

- Moulinets I, Arnaud E, Bui P, et al. Foreign body reaction to Radiesse: 2 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2013;35:e37-40.

- Beer KR. Radiesse nodule of the lips from a distant injection site: report of a case and consideration of etiology and management. J Drugs Dermatol. 2007;6:846-847.

- Ginat DT, Schatz CJ. Imaging features of midface injectable fillers and associated complications. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2013;34:1488-1495.

Practice Points

- Calcium hydroxylapatite filler can migrate and form nodules in distant locations from the original injection site.

- Practitioners of calcium hydroxylapatite fillers should be aware of the potential for nodule migration to avoid costly, time-consuming, and invasive referrals and procedures.

Upper Lip Anatomy, Mechanics of Local Flaps, and Considerations for Reconstruction

The upper lip poses challenges during reconstruction. Distortion of well-defined anatomic structures, including the vermilion border, oral commissures, Cupid’s bow, and philtrum, leads to noticeable deformities. Furthermore, maintenance of upper and lower lip function is essential for verbal communication, facial expression, and controlled opening of the oral cavity.

Similar to a prior review focused on the lower lip,1 we conducted a review of the literature using the PubMed database (1976-2017) and the following search terms: upper lip, lower lip, anatomy, comparison, cadaver, histology, local flap, and reconstruction. We reviewed studies that assessed anatomic and histologic characteristics of the upper and the lower lips, function of the upper lip, mechanics of local flaps, and upper lip reconstruction techniques including local flaps and regional flaps. Articles with an emphasis on free flaps were excluded.

The initial search resulted in 1326 articles. Of these, 1201 were excluded after abstracts were screened. Full-text review of the remaining 125 articles resulted in exclusion of 85 papers (9 foreign language, 4 duplicates, and 72 irrelevant). Among the 40 articles eligible for inclusion, 12 articles discussed anatomy and histology of the upper lip, 9 examined function of the upper lip, and 19 reviewed available techniques for reconstruction of the upper lip.

In this article, we review the anatomy and function of the upper lip as well as various repair techniques to provide the reconstructive surgeon with greater familiarity with the local flaps and an algorithmic approach for upper lip reconstruction.

Anatomic Characteristics of the Upper Lip

The muscular component of the upper lip primarily is comprised of the orbicularis oris (OO) muscle divided into 2 distinct concentric components: pars peripheralis and pars marginalis.2,3 It is discontinuous in some individuals.4 Although OO is the primary muscle of the lower lip, the upper lip is remarkably complex. Orbicularis oris and 3 additional muscles contribute to upper lip function: depressor septi nasi, the alar portion of the nasalis, and levator labii superioris alaeque nasi (LLSAN).5

The modiolus, a muscular structure located just lateral to the commissures, serves as a convergence point for facial muscle animation and lip function while distributing contraction forces between the lips and face.6 It is imperative to preserve its location in reconstruction to allow for good functional and aesthetic outcomes.

The upper lip is divided into 3 distinct aesthetic subunits: the philtrum and 1 lateral subunit on each side.7,8 Its unique surface features include the Cupid’s bow, vermilion tubercle, and philtral columns. The philtral columns are created by the dermal insertion on each side of the OO, which originates from the modiolus, decussates, and inserts into the skin of the contralateral philtral groove.2,9-11 The OO has additional insertions into the dermis lateral to the philtrum.5 During its course across the midline, it decreases its insertions, leading to the formation and thinness of the philtral dimple.9 The philtral shape primarily is due to the intermingling of LLSAN and the pars peripheralis in an axial plane. The LLSAN enters superolateral to the ipsilateral philtral ridge and courses along this ridge to contribute to the philtral shape.2 Formation of the philtrum’s contour arises from the opposing force of both muscles pulling the skin in opposite directions.2,5 The vermilion tubercle arises from the dermal insertion of the pars marginalis originating from the ipsilateral modiolus and follows the vermilion border.2 The Cupid’s bow is part of the white roll at the vermilion-cutaneous junction produced by the anterior projection of the pars peripheralis.10 The complex anatomy of this structure explains the intricacy of lip reconstructions in this area.

Function of the Upper Lip

Although the primary purpose of OO is sphincteric function, the upper lip’s key role is coverage of dentition and facial animation.12 The latter is achieved through the relationship of multiple muscles, including levator labii superioris, levator septi nasi, risorius, zygomaticus minor, zygomaticus major, levator anguli oris, and buccinator.7,13-17 Their smooth coordination results in various facial expressions. In comparison, the lower lip is critical for preservation of oral competence, prevention of drooling, eating, and speech due to the actions of OO and vertical support from the mentalis muscle.1,18-22

Reconstructive Methods for the Upper Lip

Multiple options are available for reconstruction of upper lip defects, with the aim to preserve facial animation and coverage of dentition. When animation muscles are involved, restoring function is the goal, which can be achieved by placing sutures to reapproximate the muscle edges in smaller defects or anchor the remaining muscle edge to preserve deep structures in larger defects, respecting the vector of contraction and attempting simulation of the muscle function. Additionally, restoration of the continuity of OO also is important for good aesthetic and functional outcomes.

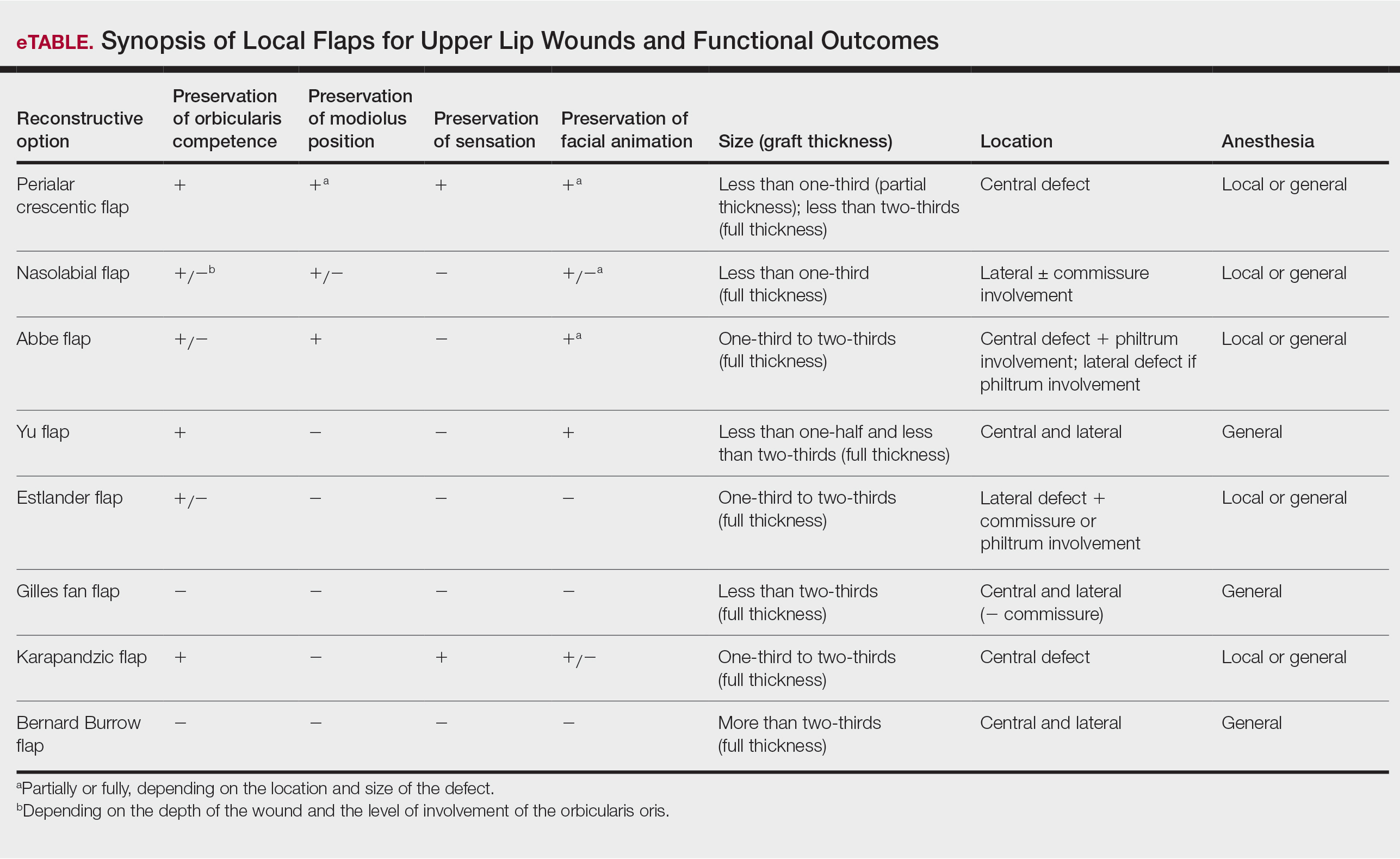

Janis23 proposed the rule of thirds to approach upper and lower lip reconstruction. Using these rules, we briefly analyze the available flaps focusing on animation, OO restoration, preservation of the modiolus position, and sensation for each (eTable).

The perialar crescentic flap, an advancement flap, can be utilized for laterally located partial-thickness defects affecting up to one-third of the upper lip, especially those adjacent to the alar base, as well as full-thickness defects affecting up to two-thirds of the upper lip.7,24 The OO continuity and position of the modiolus often are preserved, sensation is maintained, and muscles of animation commonly are unaffected by this flap, especially in partial-thickness defects. In males, caution should be exercised where non–hair-bearing skin of the cheek is advanced to the upper lip region. Other potential complications include obliteration of the melolabial crease and pincushioning.7

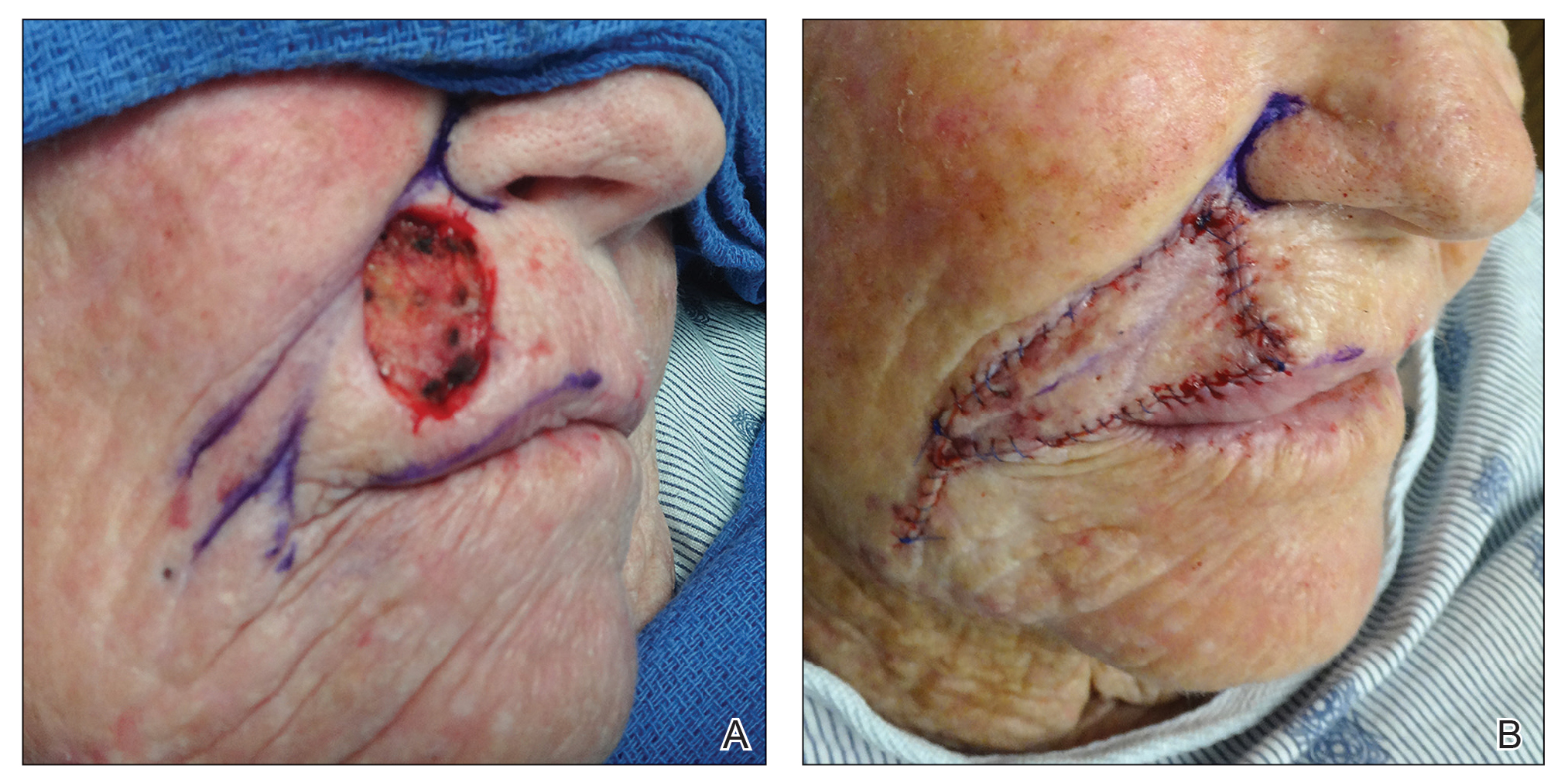

Nasolabial (ie, melolabial) flaps are suggested for repair of defects up to one-third of the upper lip, especially when the vermilion is unaffected, or in lateral defects with or without commissure involvement.7,24-28 This flap is based on the facial artery and may be used as a direct transposition, V-Y advancement, or island flap with good aesthetic and functional outcomes (Figure 1).29,30 There is limited literature regarding the effects on animation. However, it may be beneficial in avoiding microstomia, as regional tissue is transferred from the cheek area, maintaining upper lip length. Additionally, the location of the modiolus often is unaffected, especially when the flap is harvested above the level of the muscle, providing superior facial animation function. Flap design is critical in areas lateral to the commissure and over the modiolus, as distortion of its position can occur.26 Similar to crescentic advancement, it is important to exercise caution in male patients, as non–hair-bearing tissue can be transferred to the upper lip. Reported adverse outcomes of the nasolabial flap include a thin flat upper lip, obliteration of the Cupid’s bow, and hypoesthesia that may improve over time.30

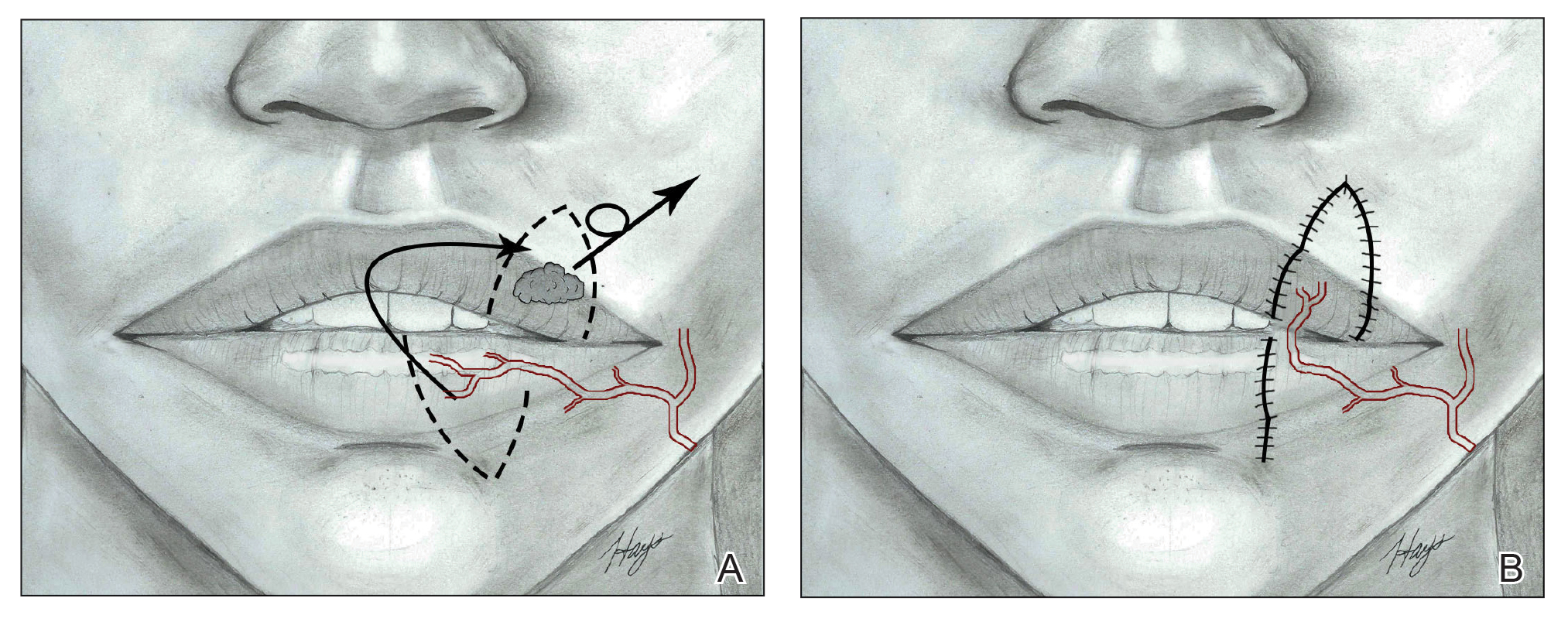

The Abbe flap is suitable for reconstruction of upper lip defects affecting up to two-thirds of the upper lip and lateral defects, provided the commissure or philtrum is unaffected.7,8 It is a 2-stage lip-switch flap based on the inferior labial artery, where tissue is harvested and transferred from the lower lip (Figure 2).23,31 It is particularly useful for philtral reconstruction, as incision lines at the flap edges can recreate the skin folds of the philtrum. Moreover, incision lines are better concealed under the nose, making it favorable for female patients. Surgeons should consider the difference in philtral width between sexes when designing this flap for optimal aesthetic outcome, as males have larger philtral width than females.21 The Abbe flap allows preservation of the Cupid’s bow, oral commissure, and modiolus position; however, it is an insensate flap and does not establish continuity of OO.23 For central defects, the function of animation muscles is not critically affected. In philtral reconstruction using an Abbe flap, a common adverse outcome is widening of the central segment because of tension and contraction forces applied by the adjacent OO. Restoration of the continuity of the muscle through dissection and advancement in small defects or anchoring of muscle edges on deeper surfaces may avoid direct pull on the flap. In larger central defects extending beyond the native philtrum, it is important to recreate the philtrum proportional to the remaining upper and lower lips. The recommended technique is a combination of a thin Abbe flap with bilateral perialar crescentic advancement flaps to maintain a proportional philtrum. Several variations have been described, including 3D planning with muscular suspension for natural raised philtral columns, avoiding a flat upper lip.5

The Yu flap, a sensate single-stage rotational advancement flap, can be used in a variety of ways for repair of upper lip defects, depending on the size and location.26 Lateral defects up to one-half of the upper lip should be repaired with a unilateral reverse Yu flap, central defects up to one-half of the upper lip can be reconstructed with bilateral reverse Yu flaps, and defects up to two-thirds of the upper lip can be repaired with bilateral Yu flaps. This flap restores OO continuity and thus preserves sphincter function, minimizes oral incompetence, and has a low risk of microstomia. The muscles of facial animation are preserved, yet the modiolus is not. Good aesthetic outcomes have been reported depending on the location of the Yu flap because scars can be placed in the nasolabial sulcus, commissures, or medially to recreate the philtrum.26

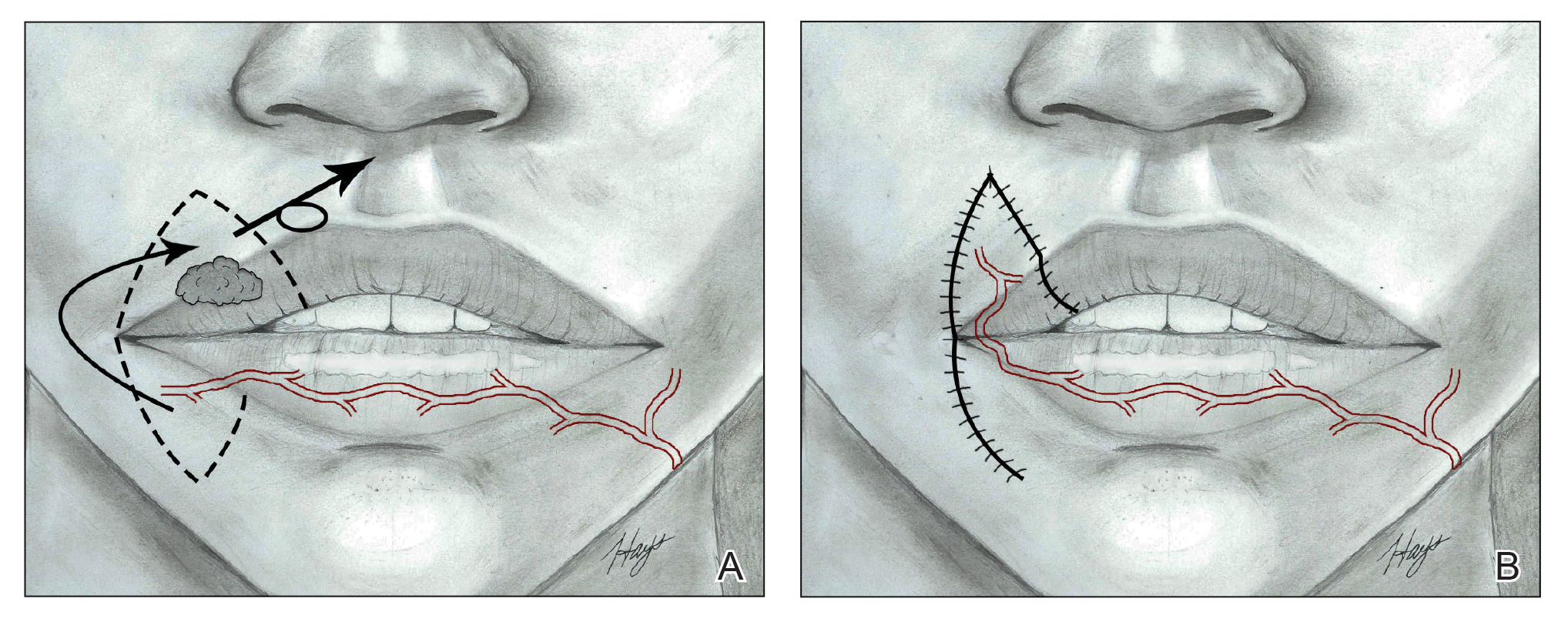

The Estlander flap is a single-stage flap utilizing donor tissue from the opposing lip for reconstruction of lateral defects up to two-thirds of the upper lip with commissure and philtrum involvement (Figure 3).8,23,32 It is an insensate flap that alters the position of the modiolus, distorting oral and facial animation.23 The superomedial position of the modiolus is better tolerated in the upper lip because it increases the relaxation tone of the lower lip and simulates the vector of contraction of major animation muscles, positively impacting the sphincteric function of the reconstructed lip. Sphincteric function action is not as impaired compared with the lower lip because the new position of the modiolus tightens the lower lip and prevents drooling.33 When designing the flap, one should consider that the inferior labial artery has been reported to remain with 10 mm of the superior border of the lower lip; therefore, pedicles of the Abbe and Estlander flaps should be at least 10 mm from the vermilion border to preserve vascular supply.34,35

The Karapandzic flap, a modified Gilles fan flap, can be employed for repair of central defects up to two-thirds of the upper lip.8,23,32,36-39 The bilateral advancement of full-thickness adjacent tissue edges preserves neurovascular structures allowing sensation and restores OO continuation.40 Prior studies have shown the average distance of the superior labial artery emergence from the facial artery and labial commissure is 12.1 mm; thus, at least 12.1 mm of tissue from the commissure should be preserved to prevent vascular compromise in Karapandzic flaps.34,35 The modiolus position is altered, and facial animation muscles are disrupted, consequently impairing facial animation, especially elevation of the lip.36 The philtrum is obliterated, producing unfavorable aesthetic outcomes. Finally, the upper lip is thinner and smaller in volume than the lower lip, increasing the risk for microstomia compared with the lower lip with a similar reconstructive technique.36

Defects larger than two-thirds of the upper lip require a Bernard Burrow flap, distant free flap, or combination of multiple regional and local flaps dependent on the characteristics of the defect.36,41 Distant free flaps are beyond the scope of this review. The Bernard Burrow flap consists of bilaterally opposing cheek advancement flaps. It is an insensate flap that does not restore OO continuity, producing minimal muscle function and poor animation. Microstomia is a common adverse outcome.36

Conclusion

Comprehensive understanding of labial anatomy and its intimate relationship to function and aesthetics of the upper lip are critical. Flap anatomy and mechanics are key factors for successful reconstruction. The purpose of this article is to utilize knowledge of histology, anatomy, and function of the upper lip to improve the outcomes of reconstruction. The Abbe flap often is utilized for reconstruction of the philtrum and central upper lip defects, though it is a less desirable option for lower lip reconstruction. The Karapandzic flap, while sensate and restorative of OO continuity, may have less optimal functional and cosmetic results compared with its use in the lower lip. Regarding lateral defects involving the commissure, the Estlander flap provides a reasonable option for the upper lip when compared with its use in lower lip defects, where outcomes are usually inferior.

- Boukovalas S, Boson AL, Hays JP, et al. A systematic review of lower lip anatomy, mechanics of local flaps, and special considerations for lower lip reconstruction. J Drugs Dermatol. 2017;16:1254-1261.

- Wu J, Yin N. Detailed anatomy of the nasolabial muscle in human fetuses as determined by micro-CT combined with iodine staining. Ann Plast Surg. 2016;76:111-116.

- Pepper JP, Baker SR. Local flaps: cheek and lip reconstruction. JAMA Facial Plast Surg. 2013;15:374-382.

- Rogers CR, Weinberg SM, Smith TD, et al. Anatomical basis for apparent subepithelial cleft lip: a histological and ultrasonographic survey of the orbicularis oris muscle. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2008;45:518-524.

- Yin N, Wu D, Wang Y, et al. Complete philtrum reconstruction on the partial-thickness cross-lip flap by nasolabial muscle tension line group reconstruction in the same stage of flap transfer. JAMA Facial Plast Surg. 2017;19:496-501.

- Al-Hoqail RA, Abdel Meguid EM. An anatomical and analytical study of the modiolus: enlightening its relevance to plastic surgery. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2009;33:147-152.

- Galyon SW, Frodel JL. Lip and perioral defects. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2001;34:647-666.

- Massa AF, Otero-Rivas M, González-Sixto B, et al. Combined cutaneous rotation flap and myomucosal tongue flap for reconstruction of an upper lip defect. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2014;105:869-871.

- Latham RA, Deaton TG. The structural basis of the philtrum and the contour of the vermilion border: a study of the musculature of the upper lip. J Anat. 1976;121:151-160.

- Garcia de Mitchell CA, Pessa JE, Schaverien MV, et al. The philtrum: anatomical observations from a new perspective. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;122:1756-1760.

- Bo C, Ningbei Y. Reconstruction of upper lip muscle system by anatomy, magnetic resonance imaging, and serial histological sections. J Craniofac Surg. 2014;25:48-54.

- Ishii LE, Byrne PJ. Lip reconstruction. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2009;17:445-453.

- Hur MS, Youn KH, Hu KS, et al. New anatomic considerations on the levator labii superioris related with the nasal ala. J Craniofac Surg. 2010;21:258-260.

- Song R, Ma H, Pan F. The “levator septi nasi muscle” and its clinical significance. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;109:1707-1712; discussion 1713.

- Choi DY, Hur MS, Youn KH, et al. Clinical anatomic considerations of the zygomaticus minor muscle based on the morphology and insertion pattern. Dermatol Surg. 2014;40:858-863.

- Youn KH, Park JT, Park DS, et al. Morphology of the zygomaticus minor and its relationship with the orbicularis oculi muscle. J Craniofac Surg. 2012;23:546-548.

- Vercruysse H, Van Nassauw L, San Miguel-Moragas J, et al. The effect of a Le Fort I incision on nose and upper lip dynamics: unraveling the mystery of the “Le Fort I lip.” J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2016;44:1917-1921.

- Vinkka-Puhakka H, Kean MR, Heap SW. Ultrasonic investigation of the circumoral musculature. J Anat. 1989;166:121-133.

- Ferrario VF, Rosati R, Peretta R, et al. Labial morphology: a 3-dimensional anthropometric study. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009;67:1832-1839.

- Ferrario VF, Sforza C, Schmitz JH, et al. Normal growth and development of the lips: a 3-dimensional study from 6 years to adulthood using a geometric model. J Anat. 2000;196:415-423.

- Sforza C, Grandi G, Binelli M, et al. Age- and sex-related changes in three-dimensional lip morphology. Forensic Sci Int. 2010;200:182.e181-187.

- Wilson DB. Embryonic development of the head and neck: part 3, the face. Head Neck Surg. 1979;2:145-153.

- Janis JE, ed. Essentials of Plastic Surgery. 2nd ed. Boca Raton, FL: Taylor & Francis Group; 2014.

- Burusapat C, Pitiseree A. Advanced squamous cell carcinoma involving both upper and lower lips and oral commissure with simultaneous reconstruction by local flap: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2012;6:23.

- El-Marakby HH. The versatile naso-labial flaps in facial reconstruction. J Egypt Natl Canc Inst. 2005;17:245-250.

- Li ZN, Li RW, Tan XX, et al. Yu’s flap for lower lip and reverse Yu’s flap for upper lip reconstruction: 20 years experience. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2013;51:767-772.

- Wollina U. Reconstructive surgery in advanced perioral non-melanoma skin cancer. Results in elderly patients. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2014;8:103-107.

- Younger RA. The versatile melolabial flap. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1992;107:721-726.

- Włodarkiewicz A, Wojszwiłło-Geppert E, Placek W, et al. Upper lip reconstruction with local island flap after neoplasm excision. Dermatol Surg. 1997;23:1075-1079.

- Cook JL. The reconstruction of two large full-thickness wounds of the upper lip with different operative techniques: when possible, a local flap repair is preferable to reconstruction with free tissue transfer. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:281-289.

- Kriet JD, Cupp CL, Sherris DA, et al. The extended Abbé flap. Laryngoscope. 1995;105:988-992.

- Khan AA, Kulkarni JV. Karapandzic flap. Indian J Dent. 2014;5:107-109.

- Raschke GF, Rieger UM, Bader RD, et al. Lip reconstruction: an anthropometric and functional analysis of surgical outcomes. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012;41:744-750.

- Maǧden O, Edizer M, Atabey A, et al. Cadaveric study of the arterial anatomy of the upper lip. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;114:355-359.

- Al-Hoqail RA, Meguid EM. Anatomic dissection of the arterial supply of the lips: an anatomical and analytical approach. J Craniofac Surg. 2008;19:785-794.

- Kim JC, Hadlock T, Varvares MA, et al. Hair-bearing temporoparietal fascial flap reconstruction of upper lip and scalp defects. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2001;3:170-177.

- Teemul TA, Telfer A, Singh RP, et al. The versatility of the Karapandzic flap: a review of 65 cases with patient-reported outcomes. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2017;45:325-329.

- Matteini C, Mazzone N, Rendine G, et al. Lip reconstruction with local m-shaped composite flap. J Craniofac Surg. 2010;21:225-228.

- Williams EF, Setzen G, Mulvaney MJ. Modified Bernard-Burow cheek advancement and cross-lip flap for total lip reconstruction. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1996;122:1253-1258.

- Jaquet Y, Pasche P, Brossard E, et al. Meyer’s surgical procedure for the treatment of lip carcinoma. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2005;262:11-16.

- Dang M, Greenbaum SS. Modified Burow’s wedge flap for upper lateral lip defects. Dermatol Surg. 2000;26:497-498.

The upper lip poses challenges during reconstruction. Distortion of well-defined anatomic structures, including the vermilion border, oral commissures, Cupid’s bow, and philtrum, leads to noticeable deformities. Furthermore, maintenance of upper and lower lip function is essential for verbal communication, facial expression, and controlled opening of the oral cavity.

Similar to a prior review focused on the lower lip,1 we conducted a review of the literature using the PubMed database (1976-2017) and the following search terms: upper lip, lower lip, anatomy, comparison, cadaver, histology, local flap, and reconstruction. We reviewed studies that assessed anatomic and histologic characteristics of the upper and the lower lips, function of the upper lip, mechanics of local flaps, and upper lip reconstruction techniques including local flaps and regional flaps. Articles with an emphasis on free flaps were excluded.

The initial search resulted in 1326 articles. Of these, 1201 were excluded after abstracts were screened. Full-text review of the remaining 125 articles resulted in exclusion of 85 papers (9 foreign language, 4 duplicates, and 72 irrelevant). Among the 40 articles eligible for inclusion, 12 articles discussed anatomy and histology of the upper lip, 9 examined function of the upper lip, and 19 reviewed available techniques for reconstruction of the upper lip.

In this article, we review the anatomy and function of the upper lip as well as various repair techniques to provide the reconstructive surgeon with greater familiarity with the local flaps and an algorithmic approach for upper lip reconstruction.

Anatomic Characteristics of the Upper Lip

The muscular component of the upper lip primarily is comprised of the orbicularis oris (OO) muscle divided into 2 distinct concentric components: pars peripheralis and pars marginalis.2,3 It is discontinuous in some individuals.4 Although OO is the primary muscle of the lower lip, the upper lip is remarkably complex. Orbicularis oris and 3 additional muscles contribute to upper lip function: depressor septi nasi, the alar portion of the nasalis, and levator labii superioris alaeque nasi (LLSAN).5

The modiolus, a muscular structure located just lateral to the commissures, serves as a convergence point for facial muscle animation and lip function while distributing contraction forces between the lips and face.6 It is imperative to preserve its location in reconstruction to allow for good functional and aesthetic outcomes.

The upper lip is divided into 3 distinct aesthetic subunits: the philtrum and 1 lateral subunit on each side.7,8 Its unique surface features include the Cupid’s bow, vermilion tubercle, and philtral columns. The philtral columns are created by the dermal insertion on each side of the OO, which originates from the modiolus, decussates, and inserts into the skin of the contralateral philtral groove.2,9-11 The OO has additional insertions into the dermis lateral to the philtrum.5 During its course across the midline, it decreases its insertions, leading to the formation and thinness of the philtral dimple.9 The philtral shape primarily is due to the intermingling of LLSAN and the pars peripheralis in an axial plane. The LLSAN enters superolateral to the ipsilateral philtral ridge and courses along this ridge to contribute to the philtral shape.2 Formation of the philtrum’s contour arises from the opposing force of both muscles pulling the skin in opposite directions.2,5 The vermilion tubercle arises from the dermal insertion of the pars marginalis originating from the ipsilateral modiolus and follows the vermilion border.2 The Cupid’s bow is part of the white roll at the vermilion-cutaneous junction produced by the anterior projection of the pars peripheralis.10 The complex anatomy of this structure explains the intricacy of lip reconstructions in this area.

Function of the Upper Lip

Although the primary purpose of OO is sphincteric function, the upper lip’s key role is coverage of dentition and facial animation.12 The latter is achieved through the relationship of multiple muscles, including levator labii superioris, levator septi nasi, risorius, zygomaticus minor, zygomaticus major, levator anguli oris, and buccinator.7,13-17 Their smooth coordination results in various facial expressions. In comparison, the lower lip is critical for preservation of oral competence, prevention of drooling, eating, and speech due to the actions of OO and vertical support from the mentalis muscle.1,18-22

Reconstructive Methods for the Upper Lip

Multiple options are available for reconstruction of upper lip defects, with the aim to preserve facial animation and coverage of dentition. When animation muscles are involved, restoring function is the goal, which can be achieved by placing sutures to reapproximate the muscle edges in smaller defects or anchor the remaining muscle edge to preserve deep structures in larger defects, respecting the vector of contraction and attempting simulation of the muscle function. Additionally, restoration of the continuity of OO also is important for good aesthetic and functional outcomes.

Janis23 proposed the rule of thirds to approach upper and lower lip reconstruction. Using these rules, we briefly analyze the available flaps focusing on animation, OO restoration, preservation of the modiolus position, and sensation for each (eTable).

The perialar crescentic flap, an advancement flap, can be utilized for laterally located partial-thickness defects affecting up to one-third of the upper lip, especially those adjacent to the alar base, as well as full-thickness defects affecting up to two-thirds of the upper lip.7,24 The OO continuity and position of the modiolus often are preserved, sensation is maintained, and muscles of animation commonly are unaffected by this flap, especially in partial-thickness defects. In males, caution should be exercised where non–hair-bearing skin of the cheek is advanced to the upper lip region. Other potential complications include obliteration of the melolabial crease and pincushioning.7

Nasolabial (ie, melolabial) flaps are suggested for repair of defects up to one-third of the upper lip, especially when the vermilion is unaffected, or in lateral defects with or without commissure involvement.7,24-28 This flap is based on the facial artery and may be used as a direct transposition, V-Y advancement, or island flap with good aesthetic and functional outcomes (Figure 1).29,30 There is limited literature regarding the effects on animation. However, it may be beneficial in avoiding microstomia, as regional tissue is transferred from the cheek area, maintaining upper lip length. Additionally, the location of the modiolus often is unaffected, especially when the flap is harvested above the level of the muscle, providing superior facial animation function. Flap design is critical in areas lateral to the commissure and over the modiolus, as distortion of its position can occur.26 Similar to crescentic advancement, it is important to exercise caution in male patients, as non–hair-bearing tissue can be transferred to the upper lip. Reported adverse outcomes of the nasolabial flap include a thin flat upper lip, obliteration of the Cupid’s bow, and hypoesthesia that may improve over time.30

The Abbe flap is suitable for reconstruction of upper lip defects affecting up to two-thirds of the upper lip and lateral defects, provided the commissure or philtrum is unaffected.7,8 It is a 2-stage lip-switch flap based on the inferior labial artery, where tissue is harvested and transferred from the lower lip (Figure 2).23,31 It is particularly useful for philtral reconstruction, as incision lines at the flap edges can recreate the skin folds of the philtrum. Moreover, incision lines are better concealed under the nose, making it favorable for female patients. Surgeons should consider the difference in philtral width between sexes when designing this flap for optimal aesthetic outcome, as males have larger philtral width than females.21 The Abbe flap allows preservation of the Cupid’s bow, oral commissure, and modiolus position; however, it is an insensate flap and does not establish continuity of OO.23 For central defects, the function of animation muscles is not critically affected. In philtral reconstruction using an Abbe flap, a common adverse outcome is widening of the central segment because of tension and contraction forces applied by the adjacent OO. Restoration of the continuity of the muscle through dissection and advancement in small defects or anchoring of muscle edges on deeper surfaces may avoid direct pull on the flap. In larger central defects extending beyond the native philtrum, it is important to recreate the philtrum proportional to the remaining upper and lower lips. The recommended technique is a combination of a thin Abbe flap with bilateral perialar crescentic advancement flaps to maintain a proportional philtrum. Several variations have been described, including 3D planning with muscular suspension for natural raised philtral columns, avoiding a flat upper lip.5

The Yu flap, a sensate single-stage rotational advancement flap, can be used in a variety of ways for repair of upper lip defects, depending on the size and location.26 Lateral defects up to one-half of the upper lip should be repaired with a unilateral reverse Yu flap, central defects up to one-half of the upper lip can be reconstructed with bilateral reverse Yu flaps, and defects up to two-thirds of the upper lip can be repaired with bilateral Yu flaps. This flap restores OO continuity and thus preserves sphincter function, minimizes oral incompetence, and has a low risk of microstomia. The muscles of facial animation are preserved, yet the modiolus is not. Good aesthetic outcomes have been reported depending on the location of the Yu flap because scars can be placed in the nasolabial sulcus, commissures, or medially to recreate the philtrum.26

The Estlander flap is a single-stage flap utilizing donor tissue from the opposing lip for reconstruction of lateral defects up to two-thirds of the upper lip with commissure and philtrum involvement (Figure 3).8,23,32 It is an insensate flap that alters the position of the modiolus, distorting oral and facial animation.23 The superomedial position of the modiolus is better tolerated in the upper lip because it increases the relaxation tone of the lower lip and simulates the vector of contraction of major animation muscles, positively impacting the sphincteric function of the reconstructed lip. Sphincteric function action is not as impaired compared with the lower lip because the new position of the modiolus tightens the lower lip and prevents drooling.33 When designing the flap, one should consider that the inferior labial artery has been reported to remain with 10 mm of the superior border of the lower lip; therefore, pedicles of the Abbe and Estlander flaps should be at least 10 mm from the vermilion border to preserve vascular supply.34,35

The Karapandzic flap, a modified Gilles fan flap, can be employed for repair of central defects up to two-thirds of the upper lip.8,23,32,36-39 The bilateral advancement of full-thickness adjacent tissue edges preserves neurovascular structures allowing sensation and restores OO continuation.40 Prior studies have shown the average distance of the superior labial artery emergence from the facial artery and labial commissure is 12.1 mm; thus, at least 12.1 mm of tissue from the commissure should be preserved to prevent vascular compromise in Karapandzic flaps.34,35 The modiolus position is altered, and facial animation muscles are disrupted, consequently impairing facial animation, especially elevation of the lip.36 The philtrum is obliterated, producing unfavorable aesthetic outcomes. Finally, the upper lip is thinner and smaller in volume than the lower lip, increasing the risk for microstomia compared with the lower lip with a similar reconstructive technique.36

Defects larger than two-thirds of the upper lip require a Bernard Burrow flap, distant free flap, or combination of multiple regional and local flaps dependent on the characteristics of the defect.36,41 Distant free flaps are beyond the scope of this review. The Bernard Burrow flap consists of bilaterally opposing cheek advancement flaps. It is an insensate flap that does not restore OO continuity, producing minimal muscle function and poor animation. Microstomia is a common adverse outcome.36

Conclusion

Comprehensive understanding of labial anatomy and its intimate relationship to function and aesthetics of the upper lip are critical. Flap anatomy and mechanics are key factors for successful reconstruction. The purpose of this article is to utilize knowledge of histology, anatomy, and function of the upper lip to improve the outcomes of reconstruction. The Abbe flap often is utilized for reconstruction of the philtrum and central upper lip defects, though it is a less desirable option for lower lip reconstruction. The Karapandzic flap, while sensate and restorative of OO continuity, may have less optimal functional and cosmetic results compared with its use in the lower lip. Regarding lateral defects involving the commissure, the Estlander flap provides a reasonable option for the upper lip when compared with its use in lower lip defects, where outcomes are usually inferior.

The upper lip poses challenges during reconstruction. Distortion of well-defined anatomic structures, including the vermilion border, oral commissures, Cupid’s bow, and philtrum, leads to noticeable deformities. Furthermore, maintenance of upper and lower lip function is essential for verbal communication, facial expression, and controlled opening of the oral cavity.

Similar to a prior review focused on the lower lip,1 we conducted a review of the literature using the PubMed database (1976-2017) and the following search terms: upper lip, lower lip, anatomy, comparison, cadaver, histology, local flap, and reconstruction. We reviewed studies that assessed anatomic and histologic characteristics of the upper and the lower lips, function of the upper lip, mechanics of local flaps, and upper lip reconstruction techniques including local flaps and regional flaps. Articles with an emphasis on free flaps were excluded.

The initial search resulted in 1326 articles. Of these, 1201 were excluded after abstracts were screened. Full-text review of the remaining 125 articles resulted in exclusion of 85 papers (9 foreign language, 4 duplicates, and 72 irrelevant). Among the 40 articles eligible for inclusion, 12 articles discussed anatomy and histology of the upper lip, 9 examined function of the upper lip, and 19 reviewed available techniques for reconstruction of the upper lip.

In this article, we review the anatomy and function of the upper lip as well as various repair techniques to provide the reconstructive surgeon with greater familiarity with the local flaps and an algorithmic approach for upper lip reconstruction.

Anatomic Characteristics of the Upper Lip

The muscular component of the upper lip primarily is comprised of the orbicularis oris (OO) muscle divided into 2 distinct concentric components: pars peripheralis and pars marginalis.2,3 It is discontinuous in some individuals.4 Although OO is the primary muscle of the lower lip, the upper lip is remarkably complex. Orbicularis oris and 3 additional muscles contribute to upper lip function: depressor septi nasi, the alar portion of the nasalis, and levator labii superioris alaeque nasi (LLSAN).5

The modiolus, a muscular structure located just lateral to the commissures, serves as a convergence point for facial muscle animation and lip function while distributing contraction forces between the lips and face.6 It is imperative to preserve its location in reconstruction to allow for good functional and aesthetic outcomes.

The upper lip is divided into 3 distinct aesthetic subunits: the philtrum and 1 lateral subunit on each side.7,8 Its unique surface features include the Cupid’s bow, vermilion tubercle, and philtral columns. The philtral columns are created by the dermal insertion on each side of the OO, which originates from the modiolus, decussates, and inserts into the skin of the contralateral philtral groove.2,9-11 The OO has additional insertions into the dermis lateral to the philtrum.5 During its course across the midline, it decreases its insertions, leading to the formation and thinness of the philtral dimple.9 The philtral shape primarily is due to the intermingling of LLSAN and the pars peripheralis in an axial plane. The LLSAN enters superolateral to the ipsilateral philtral ridge and courses along this ridge to contribute to the philtral shape.2 Formation of the philtrum’s contour arises from the opposing force of both muscles pulling the skin in opposite directions.2,5 The vermilion tubercle arises from the dermal insertion of the pars marginalis originating from the ipsilateral modiolus and follows the vermilion border.2 The Cupid’s bow is part of the white roll at the vermilion-cutaneous junction produced by the anterior projection of the pars peripheralis.10 The complex anatomy of this structure explains the intricacy of lip reconstructions in this area.

Function of the Upper Lip

Although the primary purpose of OO is sphincteric function, the upper lip’s key role is coverage of dentition and facial animation.12 The latter is achieved through the relationship of multiple muscles, including levator labii superioris, levator septi nasi, risorius, zygomaticus minor, zygomaticus major, levator anguli oris, and buccinator.7,13-17 Their smooth coordination results in various facial expressions. In comparison, the lower lip is critical for preservation of oral competence, prevention of drooling, eating, and speech due to the actions of OO and vertical support from the mentalis muscle.1,18-22

Reconstructive Methods for the Upper Lip

Multiple options are available for reconstruction of upper lip defects, with the aim to preserve facial animation and coverage of dentition. When animation muscles are involved, restoring function is the goal, which can be achieved by placing sutures to reapproximate the muscle edges in smaller defects or anchor the remaining muscle edge to preserve deep structures in larger defects, respecting the vector of contraction and attempting simulation of the muscle function. Additionally, restoration of the continuity of OO also is important for good aesthetic and functional outcomes.

Janis23 proposed the rule of thirds to approach upper and lower lip reconstruction. Using these rules, we briefly analyze the available flaps focusing on animation, OO restoration, preservation of the modiolus position, and sensation for each (eTable).

The perialar crescentic flap, an advancement flap, can be utilized for laterally located partial-thickness defects affecting up to one-third of the upper lip, especially those adjacent to the alar base, as well as full-thickness defects affecting up to two-thirds of the upper lip.7,24 The OO continuity and position of the modiolus often are preserved, sensation is maintained, and muscles of animation commonly are unaffected by this flap, especially in partial-thickness defects. In males, caution should be exercised where non–hair-bearing skin of the cheek is advanced to the upper lip region. Other potential complications include obliteration of the melolabial crease and pincushioning.7

Nasolabial (ie, melolabial) flaps are suggested for repair of defects up to one-third of the upper lip, especially when the vermilion is unaffected, or in lateral defects with or without commissure involvement.7,24-28 This flap is based on the facial artery and may be used as a direct transposition, V-Y advancement, or island flap with good aesthetic and functional outcomes (Figure 1).29,30 There is limited literature regarding the effects on animation. However, it may be beneficial in avoiding microstomia, as regional tissue is transferred from the cheek area, maintaining upper lip length. Additionally, the location of the modiolus often is unaffected, especially when the flap is harvested above the level of the muscle, providing superior facial animation function. Flap design is critical in areas lateral to the commissure and over the modiolus, as distortion of its position can occur.26 Similar to crescentic advancement, it is important to exercise caution in male patients, as non–hair-bearing tissue can be transferred to the upper lip. Reported adverse outcomes of the nasolabial flap include a thin flat upper lip, obliteration of the Cupid’s bow, and hypoesthesia that may improve over time.30

The Abbe flap is suitable for reconstruction of upper lip defects affecting up to two-thirds of the upper lip and lateral defects, provided the commissure or philtrum is unaffected.7,8 It is a 2-stage lip-switch flap based on the inferior labial artery, where tissue is harvested and transferred from the lower lip (Figure 2).23,31 It is particularly useful for philtral reconstruction, as incision lines at the flap edges can recreate the skin folds of the philtrum. Moreover, incision lines are better concealed under the nose, making it favorable for female patients. Surgeons should consider the difference in philtral width between sexes when designing this flap for optimal aesthetic outcome, as males have larger philtral width than females.21 The Abbe flap allows preservation of the Cupid’s bow, oral commissure, and modiolus position; however, it is an insensate flap and does not establish continuity of OO.23 For central defects, the function of animation muscles is not critically affected. In philtral reconstruction using an Abbe flap, a common adverse outcome is widening of the central segment because of tension and contraction forces applied by the adjacent OO. Restoration of the continuity of the muscle through dissection and advancement in small defects or anchoring of muscle edges on deeper surfaces may avoid direct pull on the flap. In larger central defects extending beyond the native philtrum, it is important to recreate the philtrum proportional to the remaining upper and lower lips. The recommended technique is a combination of a thin Abbe flap with bilateral perialar crescentic advancement flaps to maintain a proportional philtrum. Several variations have been described, including 3D planning with muscular suspension for natural raised philtral columns, avoiding a flat upper lip.5

The Yu flap, a sensate single-stage rotational advancement flap, can be used in a variety of ways for repair of upper lip defects, depending on the size and location.26 Lateral defects up to one-half of the upper lip should be repaired with a unilateral reverse Yu flap, central defects up to one-half of the upper lip can be reconstructed with bilateral reverse Yu flaps, and defects up to two-thirds of the upper lip can be repaired with bilateral Yu flaps. This flap restores OO continuity and thus preserves sphincter function, minimizes oral incompetence, and has a low risk of microstomia. The muscles of facial animation are preserved, yet the modiolus is not. Good aesthetic outcomes have been reported depending on the location of the Yu flap because scars can be placed in the nasolabial sulcus, commissures, or medially to recreate the philtrum.26

The Estlander flap is a single-stage flap utilizing donor tissue from the opposing lip for reconstruction of lateral defects up to two-thirds of the upper lip with commissure and philtrum involvement (Figure 3).8,23,32 It is an insensate flap that alters the position of the modiolus, distorting oral and facial animation.23 The superomedial position of the modiolus is better tolerated in the upper lip because it increases the relaxation tone of the lower lip and simulates the vector of contraction of major animation muscles, positively impacting the sphincteric function of the reconstructed lip. Sphincteric function action is not as impaired compared with the lower lip because the new position of the modiolus tightens the lower lip and prevents drooling.33 When designing the flap, one should consider that the inferior labial artery has been reported to remain with 10 mm of the superior border of the lower lip; therefore, pedicles of the Abbe and Estlander flaps should be at least 10 mm from the vermilion border to preserve vascular supply.34,35

The Karapandzic flap, a modified Gilles fan flap, can be employed for repair of central defects up to two-thirds of the upper lip.8,23,32,36-39 The bilateral advancement of full-thickness adjacent tissue edges preserves neurovascular structures allowing sensation and restores OO continuation.40 Prior studies have shown the average distance of the superior labial artery emergence from the facial artery and labial commissure is 12.1 mm; thus, at least 12.1 mm of tissue from the commissure should be preserved to prevent vascular compromise in Karapandzic flaps.34,35 The modiolus position is altered, and facial animation muscles are disrupted, consequently impairing facial animation, especially elevation of the lip.36 The philtrum is obliterated, producing unfavorable aesthetic outcomes. Finally, the upper lip is thinner and smaller in volume than the lower lip, increasing the risk for microstomia compared with the lower lip with a similar reconstructive technique.36

Defects larger than two-thirds of the upper lip require a Bernard Burrow flap, distant free flap, or combination of multiple regional and local flaps dependent on the characteristics of the defect.36,41 Distant free flaps are beyond the scope of this review. The Bernard Burrow flap consists of bilaterally opposing cheek advancement flaps. It is an insensate flap that does not restore OO continuity, producing minimal muscle function and poor animation. Microstomia is a common adverse outcome.36

Conclusion

Comprehensive understanding of labial anatomy and its intimate relationship to function and aesthetics of the upper lip are critical. Flap anatomy and mechanics are key factors for successful reconstruction. The purpose of this article is to utilize knowledge of histology, anatomy, and function of the upper lip to improve the outcomes of reconstruction. The Abbe flap often is utilized for reconstruction of the philtrum and central upper lip defects, though it is a less desirable option for lower lip reconstruction. The Karapandzic flap, while sensate and restorative of OO continuity, may have less optimal functional and cosmetic results compared with its use in the lower lip. Regarding lateral defects involving the commissure, the Estlander flap provides a reasonable option for the upper lip when compared with its use in lower lip defects, where outcomes are usually inferior.

- Boukovalas S, Boson AL, Hays JP, et al. A systematic review of lower lip anatomy, mechanics of local flaps, and special considerations for lower lip reconstruction. J Drugs Dermatol. 2017;16:1254-1261.

- Wu J, Yin N. Detailed anatomy of the nasolabial muscle in human fetuses as determined by micro-CT combined with iodine staining. Ann Plast Surg. 2016;76:111-116.

- Pepper JP, Baker SR. Local flaps: cheek and lip reconstruction. JAMA Facial Plast Surg. 2013;15:374-382.

- Rogers CR, Weinberg SM, Smith TD, et al. Anatomical basis for apparent subepithelial cleft lip: a histological and ultrasonographic survey of the orbicularis oris muscle. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2008;45:518-524.

- Yin N, Wu D, Wang Y, et al. Complete philtrum reconstruction on the partial-thickness cross-lip flap by nasolabial muscle tension line group reconstruction in the same stage of flap transfer. JAMA Facial Plast Surg. 2017;19:496-501.

- Al-Hoqail RA, Abdel Meguid EM. An anatomical and analytical study of the modiolus: enlightening its relevance to plastic surgery. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2009;33:147-152.

- Galyon SW, Frodel JL. Lip and perioral defects. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2001;34:647-666.

- Massa AF, Otero-Rivas M, González-Sixto B, et al. Combined cutaneous rotation flap and myomucosal tongue flap for reconstruction of an upper lip defect. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2014;105:869-871.

- Latham RA, Deaton TG. The structural basis of the philtrum and the contour of the vermilion border: a study of the musculature of the upper lip. J Anat. 1976;121:151-160.

- Garcia de Mitchell CA, Pessa JE, Schaverien MV, et al. The philtrum: anatomical observations from a new perspective. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;122:1756-1760.

- Bo C, Ningbei Y. Reconstruction of upper lip muscle system by anatomy, magnetic resonance imaging, and serial histological sections. J Craniofac Surg. 2014;25:48-54.

- Ishii LE, Byrne PJ. Lip reconstruction. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2009;17:445-453.

- Hur MS, Youn KH, Hu KS, et al. New anatomic considerations on the levator labii superioris related with the nasal ala. J Craniofac Surg. 2010;21:258-260.

- Song R, Ma H, Pan F. The “levator septi nasi muscle” and its clinical significance. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;109:1707-1712; discussion 1713.

- Choi DY, Hur MS, Youn KH, et al. Clinical anatomic considerations of the zygomaticus minor muscle based on the morphology and insertion pattern. Dermatol Surg. 2014;40:858-863.

- Youn KH, Park JT, Park DS, et al. Morphology of the zygomaticus minor and its relationship with the orbicularis oculi muscle. J Craniofac Surg. 2012;23:546-548.

- Vercruysse H, Van Nassauw L, San Miguel-Moragas J, et al. The effect of a Le Fort I incision on nose and upper lip dynamics: unraveling the mystery of the “Le Fort I lip.” J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2016;44:1917-1921.

- Vinkka-Puhakka H, Kean MR, Heap SW. Ultrasonic investigation of the circumoral musculature. J Anat. 1989;166:121-133.

- Ferrario VF, Rosati R, Peretta R, et al. Labial morphology: a 3-dimensional anthropometric study. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009;67:1832-1839.

- Ferrario VF, Sforza C, Schmitz JH, et al. Normal growth and development of the lips: a 3-dimensional study from 6 years to adulthood using a geometric model. J Anat. 2000;196:415-423.

- Sforza C, Grandi G, Binelli M, et al. Age- and sex-related changes in three-dimensional lip morphology. Forensic Sci Int. 2010;200:182.e181-187.

- Wilson DB. Embryonic development of the head and neck: part 3, the face. Head Neck Surg. 1979;2:145-153.

- Janis JE, ed. Essentials of Plastic Surgery. 2nd ed. Boca Raton, FL: Taylor & Francis Group; 2014.

- Burusapat C, Pitiseree A. Advanced squamous cell carcinoma involving both upper and lower lips and oral commissure with simultaneous reconstruction by local flap: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2012;6:23.

- El-Marakby HH. The versatile naso-labial flaps in facial reconstruction. J Egypt Natl Canc Inst. 2005;17:245-250.

- Li ZN, Li RW, Tan XX, et al. Yu’s flap for lower lip and reverse Yu’s flap for upper lip reconstruction: 20 years experience. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2013;51:767-772.

- Wollina U. Reconstructive surgery in advanced perioral non-melanoma skin cancer. Results in elderly patients. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2014;8:103-107.

- Younger RA. The versatile melolabial flap. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1992;107:721-726.

- Włodarkiewicz A, Wojszwiłło-Geppert E, Placek W, et al. Upper lip reconstruction with local island flap after neoplasm excision. Dermatol Surg. 1997;23:1075-1079.

- Cook JL. The reconstruction of two large full-thickness wounds of the upper lip with different operative techniques: when possible, a local flap repair is preferable to reconstruction with free tissue transfer. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:281-289.

- Kriet JD, Cupp CL, Sherris DA, et al. The extended Abbé flap. Laryngoscope. 1995;105:988-992.

- Khan AA, Kulkarni JV. Karapandzic flap. Indian J Dent. 2014;5:107-109.

- Raschke GF, Rieger UM, Bader RD, et al. Lip reconstruction: an anthropometric and functional analysis of surgical outcomes. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012;41:744-750.

- Maǧden O, Edizer M, Atabey A, et al. Cadaveric study of the arterial anatomy of the upper lip. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;114:355-359.

- Al-Hoqail RA, Meguid EM. Anatomic dissection of the arterial supply of the lips: an anatomical and analytical approach. J Craniofac Surg. 2008;19:785-794.

- Kim JC, Hadlock T, Varvares MA, et al. Hair-bearing temporoparietal fascial flap reconstruction of upper lip and scalp defects. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2001;3:170-177.

- Teemul TA, Telfer A, Singh RP, et al. The versatility of the Karapandzic flap: a review of 65 cases with patient-reported outcomes. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2017;45:325-329.

- Matteini C, Mazzone N, Rendine G, et al. Lip reconstruction with local m-shaped composite flap. J Craniofac Surg. 2010;21:225-228.

- Williams EF, Setzen G, Mulvaney MJ. Modified Bernard-Burow cheek advancement and cross-lip flap for total lip reconstruction. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1996;122:1253-1258.

- Jaquet Y, Pasche P, Brossard E, et al. Meyer’s surgical procedure for the treatment of lip carcinoma. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2005;262:11-16.

- Dang M, Greenbaum SS. Modified Burow’s wedge flap for upper lateral lip defects. Dermatol Surg. 2000;26:497-498.

- Boukovalas S, Boson AL, Hays JP, et al. A systematic review of lower lip anatomy, mechanics of local flaps, and special considerations for lower lip reconstruction. J Drugs Dermatol. 2017;16:1254-1261.

- Wu J, Yin N. Detailed anatomy of the nasolabial muscle in human fetuses as determined by micro-CT combined with iodine staining. Ann Plast Surg. 2016;76:111-116.

- Pepper JP, Baker SR. Local flaps: cheek and lip reconstruction. JAMA Facial Plast Surg. 2013;15:374-382.

- Rogers CR, Weinberg SM, Smith TD, et al. Anatomical basis for apparent subepithelial cleft lip: a histological and ultrasonographic survey of the orbicularis oris muscle. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2008;45:518-524.

- Yin N, Wu D, Wang Y, et al. Complete philtrum reconstruction on the partial-thickness cross-lip flap by nasolabial muscle tension line group reconstruction in the same stage of flap transfer. JAMA Facial Plast Surg. 2017;19:496-501.

- Al-Hoqail RA, Abdel Meguid EM. An anatomical and analytical study of the modiolus: enlightening its relevance to plastic surgery. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2009;33:147-152.

- Galyon SW, Frodel JL. Lip and perioral defects. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2001;34:647-666.

- Massa AF, Otero-Rivas M, González-Sixto B, et al. Combined cutaneous rotation flap and myomucosal tongue flap for reconstruction of an upper lip defect. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2014;105:869-871.

- Latham RA, Deaton TG. The structural basis of the philtrum and the contour of the vermilion border: a study of the musculature of the upper lip. J Anat. 1976;121:151-160.

- Garcia de Mitchell CA, Pessa JE, Schaverien MV, et al. The philtrum: anatomical observations from a new perspective. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;122:1756-1760.

- Bo C, Ningbei Y. Reconstruction of upper lip muscle system by anatomy, magnetic resonance imaging, and serial histological sections. J Craniofac Surg. 2014;25:48-54.

- Ishii LE, Byrne PJ. Lip reconstruction. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2009;17:445-453.

- Hur MS, Youn KH, Hu KS, et al. New anatomic considerations on the levator labii superioris related with the nasal ala. J Craniofac Surg. 2010;21:258-260.

- Song R, Ma H, Pan F. The “levator septi nasi muscle” and its clinical significance. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;109:1707-1712; discussion 1713.

- Choi DY, Hur MS, Youn KH, et al. Clinical anatomic considerations of the zygomaticus minor muscle based on the morphology and insertion pattern. Dermatol Surg. 2014;40:858-863.

- Youn KH, Park JT, Park DS, et al. Morphology of the zygomaticus minor and its relationship with the orbicularis oculi muscle. J Craniofac Surg. 2012;23:546-548.

- Vercruysse H, Van Nassauw L, San Miguel-Moragas J, et al. The effect of a Le Fort I incision on nose and upper lip dynamics: unraveling the mystery of the “Le Fort I lip.” J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2016;44:1917-1921.

- Vinkka-Puhakka H, Kean MR, Heap SW. Ultrasonic investigation of the circumoral musculature. J Anat. 1989;166:121-133.

- Ferrario VF, Rosati R, Peretta R, et al. Labial morphology: a 3-dimensional anthropometric study. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009;67:1832-1839.

- Ferrario VF, Sforza C, Schmitz JH, et al. Normal growth and development of the lips: a 3-dimensional study from 6 years to adulthood using a geometric model. J Anat. 2000;196:415-423.

- Sforza C, Grandi G, Binelli M, et al. Age- and sex-related changes in three-dimensional lip morphology. Forensic Sci Int. 2010;200:182.e181-187.

- Wilson DB. Embryonic development of the head and neck: part 3, the face. Head Neck Surg. 1979;2:145-153.

- Janis JE, ed. Essentials of Plastic Surgery. 2nd ed. Boca Raton, FL: Taylor & Francis Group; 2014.

- Burusapat C, Pitiseree A. Advanced squamous cell carcinoma involving both upper and lower lips and oral commissure with simultaneous reconstruction by local flap: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2012;6:23.

- El-Marakby HH. The versatile naso-labial flaps in facial reconstruction. J Egypt Natl Canc Inst. 2005;17:245-250.

- Li ZN, Li RW, Tan XX, et al. Yu’s flap for lower lip and reverse Yu’s flap for upper lip reconstruction: 20 years experience. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2013;51:767-772.

- Wollina U. Reconstructive surgery in advanced perioral non-melanoma skin cancer. Results in elderly patients. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2014;8:103-107.

- Younger RA. The versatile melolabial flap. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1992;107:721-726.

- Włodarkiewicz A, Wojszwiłło-Geppert E, Placek W, et al. Upper lip reconstruction with local island flap after neoplasm excision. Dermatol Surg. 1997;23:1075-1079.

- Cook JL. The reconstruction of two large full-thickness wounds of the upper lip with different operative techniques: when possible, a local flap repair is preferable to reconstruction with free tissue transfer. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:281-289.

- Kriet JD, Cupp CL, Sherris DA, et al. The extended Abbé flap. Laryngoscope. 1995;105:988-992.

- Khan AA, Kulkarni JV. Karapandzic flap. Indian J Dent. 2014;5:107-109.

- Raschke GF, Rieger UM, Bader RD, et al. Lip reconstruction: an anthropometric and functional analysis of surgical outcomes. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012;41:744-750.

- Maǧden O, Edizer M, Atabey A, et al. Cadaveric study of the arterial anatomy of the upper lip. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;114:355-359.

- Al-Hoqail RA, Meguid EM. Anatomic dissection of the arterial supply of the lips: an anatomical and analytical approach. J Craniofac Surg. 2008;19:785-794.

- Kim JC, Hadlock T, Varvares MA, et al. Hair-bearing temporoparietal fascial flap reconstruction of upper lip and scalp defects. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2001;3:170-177.

- Teemul TA, Telfer A, Singh RP, et al. The versatility of the Karapandzic flap: a review of 65 cases with patient-reported outcomes. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2017;45:325-329.

- Matteini C, Mazzone N, Rendine G, et al. Lip reconstruction with local m-shaped composite flap. J Craniofac Surg. 2010;21:225-228.

- Williams EF, Setzen G, Mulvaney MJ. Modified Bernard-Burow cheek advancement and cross-lip flap for total lip reconstruction. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1996;122:1253-1258.

- Jaquet Y, Pasche P, Brossard E, et al. Meyer’s surgical procedure for the treatment of lip carcinoma. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2005;262:11-16.

- Dang M, Greenbaum SS. Modified Burow’s wedge flap for upper lateral lip defects. Dermatol Surg. 2000;26:497-498.