User login

Deep Soft Tissue Mass of the Knee

The Diagnosis: Nodular Fasciitis

The diagnosis of spindle cell tumors can be challenging; however, by using a variety of immunoperoxidase stains and fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) testing in conjunction with histology, it often is possible to arrive at a definitive diagnosis. For this case, the histologic features in conjunction with the immunoperoxidase stains and FISH were consistent with a diagnosis of nodular fasciitis.

Nodular fasciitis is a benign, self-limiting, myofibroblastic, soft-tissue proliferation typically found in the subcutaneous tissue.1 It can be found anywhere on the body but most commonly on the upper arms and trunk. It most often is seen in young adults, and many cases have been reported in association with a history of trauma to the area.1,2 It typically measures less than 2 cm in diameter.3 The diagnosis of nodular fasciitis is particularly challenging because it mimics sarcoma, both in presentation and in histologic findings with rapid growth, high mitotic activity, and increased cellularity.1,4-7 In contrast to malignancy, nodular fasciitis has no atypical mitoses and little cytologic atypia.8,9 Rather, it contains plump myofibroblasts loosely arranged in a myxoid or fibrous stroma that also may contain lymphocytes, extravasated erythrocytes, and osteoclastlike giant cells distributed throughout.5,10,11 In this case, lymphocytes, extravasated red blood cells, and myxoid change are present, suggesting the diagnosis of nodular fasciitis. In other cases, however, these features may be much more limited, making the diagnosis more challenging. The spindle cells are arranged in poorly defined short fascicles. The tumor cells do not infiltrate between individual adipocytes. There is no notable cytologic atypia.

Because of the difficulty in making the diagnosis, overtreatment of this benign condition can be a problem, causing increased morbidity.1 Erickson-Johnson et al12 identified the role of an ubiquitin-specific peptidase 6, USP6, gene rearrangement on chromosome 17p13 in 92% (44/48) of cases of nodular fasciitis. The USP6 gene most often is rearranged with the myosin heavy chain 9 gene, MYH9, on chromosome 22q12.3. With this rearrangement, the MYH9 promoter leads to the overexpression of USP6, causing tumor formation.2,13 The use of multiple immunoperoxidase stains can be important in the identification of nodular fasciitis. Nodular fasciitis stains negative for S-100, epithelial membrane antigen, CD34, β-catenin, and cytokeratin, but typically stains positive for smooth muscle actin.9

Although dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP) was in the differential diagnosis, these tumors tend to have greater cellularity than nodular fasciitis. In addition, the spindle cells of DFSP typically are arranged in a storiform pattern. Another characteristic feature of DFSP is that the tumor cells will infiltrate between adipose cells creating a lacelike or honeycomblike appearance within the subcutaneous tissue (Figure 1). Immunohistochemistry staining and FISH testing may be useful in making a diagnosis of DFSP. These tumors typically are positive for CD34 by immunoperoxidase staining and demonstrate a translocation t(17;22)(q21;q13) between platelet-derived growth factor subunit B gene, PDGFB, and collagen type I alpha 1 chain gene, COL1A1, by FISH.

The distinction between the fibrous phase of nodular fasciitis and fibromatosis can be challenging. The size of the lesion may be helpful, with most lesions of nodular fasciitis being less than 3 cm, while lesions of fibromatosis have a mean diameter of 7 cm.5,14 Microscopically, both tumors demonstrate a fascicular growth pattern; however, the fascicles in nodular fasciitis tend to be short and irregular compared to the longer fascicles seen in fibromatosis (Figure 2). Immunohistochemistry staining has limited utility with only 56% (14/25) of superficial fibromatoses having positive nuclear staining for β-catenin.15

Low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma (LGFMS) would be unusual in this clinical scenario. Only 13% to 19% of cases present in patients younger than 18 years (mean age, 33 years).16 In LGFMS there are cytologically bland spindle cells that are typically arranged in a patternless or whorled pattern (Figure 3), though fascicular architecture may be seen. There are alternating areas of fibrous and myxoid stroma. A curvilinear vasculature network and lack of lymphocytes and extravasated red blood cells are histologic features favoring LGFMS over nodular fasciitis. Immunohistochemistry staining and FISH testing can be useful in making the diagnosis of LGFMS. These tumors are characterized by a translocation t(7;16)(q34;p11) involving the fusion in sarcoma, FUS, and cAMP responsive element binding protein 3 like 2, CREB3L2, genes.16 Positive immunohistochemistry staining for MUC4 can be seen in up to 100% of LGFMS and is absent in many other spindle cell tumors.16

Plexiform fibrohistiocytic tumor (PFT) is least likely to be confused with nodular fasciitis. Histologically these tumors are characterized by multiple small nodules arranged in a plexiform pattern (Figure 4). Within the nodules, 3 cell types may be noted: spindle fibroblast-like cells, mononuclear histiocyte-like cells, and osteoclastlike cells.17 Either the spindle cells or the mononuclear cells may predominate in cases of PFT. Immunohistochemistry staining of PFT is nonspecific and there are no molecular/FISH studies that can be used to help confirm the diagnosis.

- Shin C, Low I, Ng D, et al. USP6 gene rearrangement in nodular fasciitis and histological mimics. Histopathology. 2016;69:784-791.

- Kumar E, Patel NR, Demicco EG, et al. Cutaneous nodular fasciitis with genetic analysis: a case series. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:1143-1149.

- Nishio J. Updates on the cytogenetics and molecular cytogenetics of benign and intermediate soft tissue tumors. Oncol Lett. 2013;5:12-18.

- Lin X, Wang L, Zhang Y, et al. Variable Ki67 proliferative index in 65 cases of nodular fasciitis, compared with fibrosarcoma and fibromatosis. Diagn Pathol. 2013;8:50.

- Goldstein J, Cates J. Differential diagnostic considerations of desmoid-type fibromatosis. Adv Anat Pathol. 2015;22:260-266.

- Fletcher CDM, Bridge JA, Hogendoorn PCW, et al, eds. WHO Classification of Tumours of Soft Tissue and Bone. 4th ed. Lyons, France: IARC Press; 2013.

- Bridge JA, Cushman-Vokoun AM. Molecular diagnostics of soft tissue tumors. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2011;135:588-601.

- Anzeljc AJ, Oliveira AM, Grossniklaus HE, et al. Nodular fasciitis of the orbit: a case report confirmed by molecular cytogenetic analysis. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017;33(3S suppl 1):S152-S155.

- de Paula SA, Cruz AA, de Alencar VM, et al. Nodular fasciitis presenting as a large mass in the upper eyelid. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;22:494-495.

- Bernstein KE, Lattes R. Nodular (pseudosarcomatous) fasciitis, a nonrecurrent lesion: clinicopathologic study of 134 cases. Cancer. 1982;49:1668-1678.

- Shimizu S, Hashimoto H, Enjoji M. Nodular fasciitis: an analysis of 250 patients. Pathology. 1984;16:161-166.

- Erickson-Johnson MR, Chou MM, Evers BR, et al. Nodular fasciitis: a novel model of transient neoplasia induced by MYH9-USP6 gene fusion. Lab Invest. 2011;91:1427-1433.

- Amary MF, Ye H, Berisha F, et al. Detection of USP6 gene rearrangement in nodular fasciitis: an important diagnostic tool. Virchows Arch. 2013;463:97-98.

- Wirth L, Klein A, Baur-Melnyk A. Desmoid tumors of the extremity and trunk. a retrospective study of 44 patients. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2018;19:2.

- Carlson JW, Fletcher CD. Immunohistochemistry for beta-catenin in the differential diagnosis of spindle cells lesions: analysis of a series and review of the literature. Histopathology. 2007;51:509-514.

- Mohamed M, Fisher C, Thway K. Low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma: clinical, morphologic and genetic features. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2017;28:60-67.

- Taher A, Pushpanathan C. Plexiform fibrohistiocytic tumor: a brief review. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2007;131:1135-1138.

The Diagnosis: Nodular Fasciitis

The diagnosis of spindle cell tumors can be challenging; however, by using a variety of immunoperoxidase stains and fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) testing in conjunction with histology, it often is possible to arrive at a definitive diagnosis. For this case, the histologic features in conjunction with the immunoperoxidase stains and FISH were consistent with a diagnosis of nodular fasciitis.

Nodular fasciitis is a benign, self-limiting, myofibroblastic, soft-tissue proliferation typically found in the subcutaneous tissue.1 It can be found anywhere on the body but most commonly on the upper arms and trunk. It most often is seen in young adults, and many cases have been reported in association with a history of trauma to the area.1,2 It typically measures less than 2 cm in diameter.3 The diagnosis of nodular fasciitis is particularly challenging because it mimics sarcoma, both in presentation and in histologic findings with rapid growth, high mitotic activity, and increased cellularity.1,4-7 In contrast to malignancy, nodular fasciitis has no atypical mitoses and little cytologic atypia.8,9 Rather, it contains plump myofibroblasts loosely arranged in a myxoid or fibrous stroma that also may contain lymphocytes, extravasated erythrocytes, and osteoclastlike giant cells distributed throughout.5,10,11 In this case, lymphocytes, extravasated red blood cells, and myxoid change are present, suggesting the diagnosis of nodular fasciitis. In other cases, however, these features may be much more limited, making the diagnosis more challenging. The spindle cells are arranged in poorly defined short fascicles. The tumor cells do not infiltrate between individual adipocytes. There is no notable cytologic atypia.

Because of the difficulty in making the diagnosis, overtreatment of this benign condition can be a problem, causing increased morbidity.1 Erickson-Johnson et al12 identified the role of an ubiquitin-specific peptidase 6, USP6, gene rearrangement on chromosome 17p13 in 92% (44/48) of cases of nodular fasciitis. The USP6 gene most often is rearranged with the myosin heavy chain 9 gene, MYH9, on chromosome 22q12.3. With this rearrangement, the MYH9 promoter leads to the overexpression of USP6, causing tumor formation.2,13 The use of multiple immunoperoxidase stains can be important in the identification of nodular fasciitis. Nodular fasciitis stains negative for S-100, epithelial membrane antigen, CD34, β-catenin, and cytokeratin, but typically stains positive for smooth muscle actin.9

Although dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP) was in the differential diagnosis, these tumors tend to have greater cellularity than nodular fasciitis. In addition, the spindle cells of DFSP typically are arranged in a storiform pattern. Another characteristic feature of DFSP is that the tumor cells will infiltrate between adipose cells creating a lacelike or honeycomblike appearance within the subcutaneous tissue (Figure 1). Immunohistochemistry staining and FISH testing may be useful in making a diagnosis of DFSP. These tumors typically are positive for CD34 by immunoperoxidase staining and demonstrate a translocation t(17;22)(q21;q13) between platelet-derived growth factor subunit B gene, PDGFB, and collagen type I alpha 1 chain gene, COL1A1, by FISH.

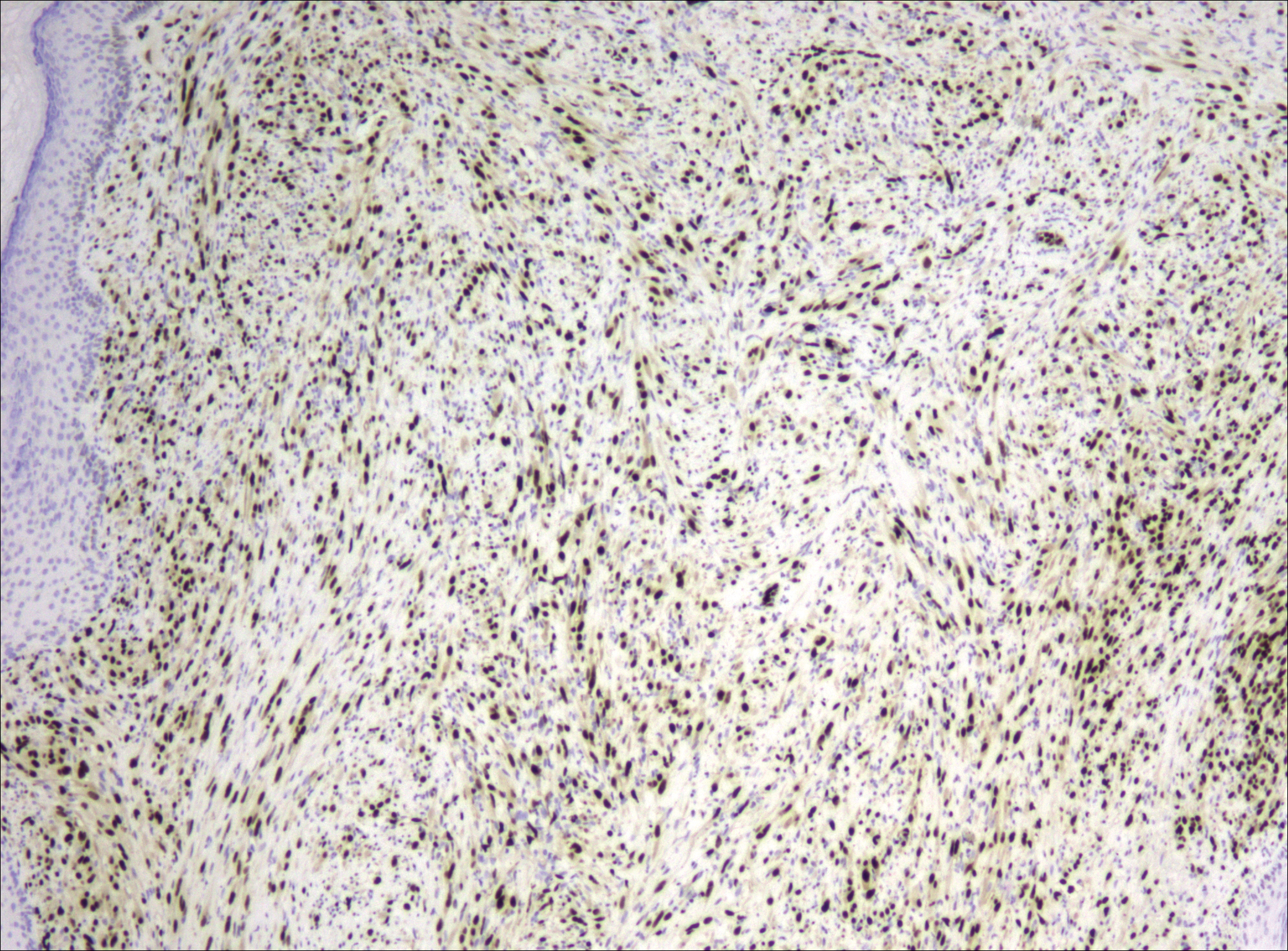

The distinction between the fibrous phase of nodular fasciitis and fibromatosis can be challenging. The size of the lesion may be helpful, with most lesions of nodular fasciitis being less than 3 cm, while lesions of fibromatosis have a mean diameter of 7 cm.5,14 Microscopically, both tumors demonstrate a fascicular growth pattern; however, the fascicles in nodular fasciitis tend to be short and irregular compared to the longer fascicles seen in fibromatosis (Figure 2). Immunohistochemistry staining has limited utility with only 56% (14/25) of superficial fibromatoses having positive nuclear staining for β-catenin.15

Low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma (LGFMS) would be unusual in this clinical scenario. Only 13% to 19% of cases present in patients younger than 18 years (mean age, 33 years).16 In LGFMS there are cytologically bland spindle cells that are typically arranged in a patternless or whorled pattern (Figure 3), though fascicular architecture may be seen. There are alternating areas of fibrous and myxoid stroma. A curvilinear vasculature network and lack of lymphocytes and extravasated red blood cells are histologic features favoring LGFMS over nodular fasciitis. Immunohistochemistry staining and FISH testing can be useful in making the diagnosis of LGFMS. These tumors are characterized by a translocation t(7;16)(q34;p11) involving the fusion in sarcoma, FUS, and cAMP responsive element binding protein 3 like 2, CREB3L2, genes.16 Positive immunohistochemistry staining for MUC4 can be seen in up to 100% of LGFMS and is absent in many other spindle cell tumors.16

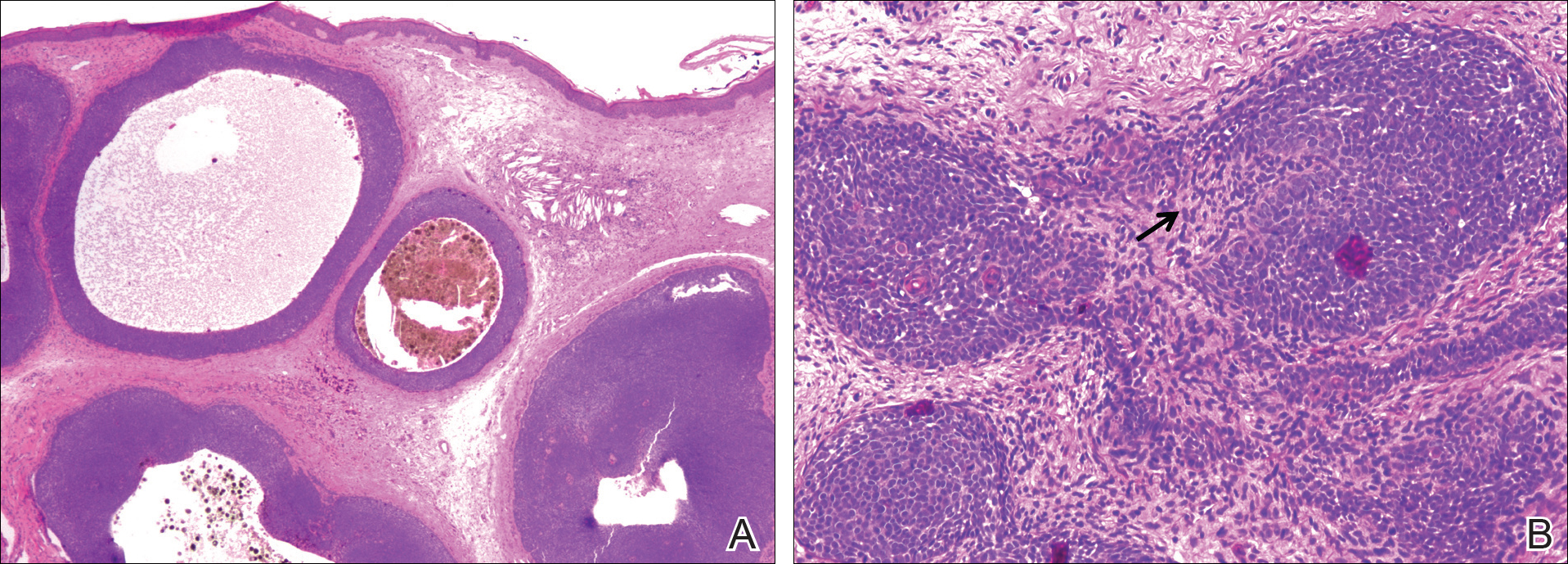

Plexiform fibrohistiocytic tumor (PFT) is least likely to be confused with nodular fasciitis. Histologically these tumors are characterized by multiple small nodules arranged in a plexiform pattern (Figure 4). Within the nodules, 3 cell types may be noted: spindle fibroblast-like cells, mononuclear histiocyte-like cells, and osteoclastlike cells.17 Either the spindle cells or the mononuclear cells may predominate in cases of PFT. Immunohistochemistry staining of PFT is nonspecific and there are no molecular/FISH studies that can be used to help confirm the diagnosis.

The Diagnosis: Nodular Fasciitis

The diagnosis of spindle cell tumors can be challenging; however, by using a variety of immunoperoxidase stains and fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) testing in conjunction with histology, it often is possible to arrive at a definitive diagnosis. For this case, the histologic features in conjunction with the immunoperoxidase stains and FISH were consistent with a diagnosis of nodular fasciitis.

Nodular fasciitis is a benign, self-limiting, myofibroblastic, soft-tissue proliferation typically found in the subcutaneous tissue.1 It can be found anywhere on the body but most commonly on the upper arms and trunk. It most often is seen in young adults, and many cases have been reported in association with a history of trauma to the area.1,2 It typically measures less than 2 cm in diameter.3 The diagnosis of nodular fasciitis is particularly challenging because it mimics sarcoma, both in presentation and in histologic findings with rapid growth, high mitotic activity, and increased cellularity.1,4-7 In contrast to malignancy, nodular fasciitis has no atypical mitoses and little cytologic atypia.8,9 Rather, it contains plump myofibroblasts loosely arranged in a myxoid or fibrous stroma that also may contain lymphocytes, extravasated erythrocytes, and osteoclastlike giant cells distributed throughout.5,10,11 In this case, lymphocytes, extravasated red blood cells, and myxoid change are present, suggesting the diagnosis of nodular fasciitis. In other cases, however, these features may be much more limited, making the diagnosis more challenging. The spindle cells are arranged in poorly defined short fascicles. The tumor cells do not infiltrate between individual adipocytes. There is no notable cytologic atypia.

Because of the difficulty in making the diagnosis, overtreatment of this benign condition can be a problem, causing increased morbidity.1 Erickson-Johnson et al12 identified the role of an ubiquitin-specific peptidase 6, USP6, gene rearrangement on chromosome 17p13 in 92% (44/48) of cases of nodular fasciitis. The USP6 gene most often is rearranged with the myosin heavy chain 9 gene, MYH9, on chromosome 22q12.3. With this rearrangement, the MYH9 promoter leads to the overexpression of USP6, causing tumor formation.2,13 The use of multiple immunoperoxidase stains can be important in the identification of nodular fasciitis. Nodular fasciitis stains negative for S-100, epithelial membrane antigen, CD34, β-catenin, and cytokeratin, but typically stains positive for smooth muscle actin.9

Although dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP) was in the differential diagnosis, these tumors tend to have greater cellularity than nodular fasciitis. In addition, the spindle cells of DFSP typically are arranged in a storiform pattern. Another characteristic feature of DFSP is that the tumor cells will infiltrate between adipose cells creating a lacelike or honeycomblike appearance within the subcutaneous tissue (Figure 1). Immunohistochemistry staining and FISH testing may be useful in making a diagnosis of DFSP. These tumors typically are positive for CD34 by immunoperoxidase staining and demonstrate a translocation t(17;22)(q21;q13) between platelet-derived growth factor subunit B gene, PDGFB, and collagen type I alpha 1 chain gene, COL1A1, by FISH.

The distinction between the fibrous phase of nodular fasciitis and fibromatosis can be challenging. The size of the lesion may be helpful, with most lesions of nodular fasciitis being less than 3 cm, while lesions of fibromatosis have a mean diameter of 7 cm.5,14 Microscopically, both tumors demonstrate a fascicular growth pattern; however, the fascicles in nodular fasciitis tend to be short and irregular compared to the longer fascicles seen in fibromatosis (Figure 2). Immunohistochemistry staining has limited utility with only 56% (14/25) of superficial fibromatoses having positive nuclear staining for β-catenin.15

Low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma (LGFMS) would be unusual in this clinical scenario. Only 13% to 19% of cases present in patients younger than 18 years (mean age, 33 years).16 In LGFMS there are cytologically bland spindle cells that are typically arranged in a patternless or whorled pattern (Figure 3), though fascicular architecture may be seen. There are alternating areas of fibrous and myxoid stroma. A curvilinear vasculature network and lack of lymphocytes and extravasated red blood cells are histologic features favoring LGFMS over nodular fasciitis. Immunohistochemistry staining and FISH testing can be useful in making the diagnosis of LGFMS. These tumors are characterized by a translocation t(7;16)(q34;p11) involving the fusion in sarcoma, FUS, and cAMP responsive element binding protein 3 like 2, CREB3L2, genes.16 Positive immunohistochemistry staining for MUC4 can be seen in up to 100% of LGFMS and is absent in many other spindle cell tumors.16

Plexiform fibrohistiocytic tumor (PFT) is least likely to be confused with nodular fasciitis. Histologically these tumors are characterized by multiple small nodules arranged in a plexiform pattern (Figure 4). Within the nodules, 3 cell types may be noted: spindle fibroblast-like cells, mononuclear histiocyte-like cells, and osteoclastlike cells.17 Either the spindle cells or the mononuclear cells may predominate in cases of PFT. Immunohistochemistry staining of PFT is nonspecific and there are no molecular/FISH studies that can be used to help confirm the diagnosis.

- Shin C, Low I, Ng D, et al. USP6 gene rearrangement in nodular fasciitis and histological mimics. Histopathology. 2016;69:784-791.

- Kumar E, Patel NR, Demicco EG, et al. Cutaneous nodular fasciitis with genetic analysis: a case series. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:1143-1149.

- Nishio J. Updates on the cytogenetics and molecular cytogenetics of benign and intermediate soft tissue tumors. Oncol Lett. 2013;5:12-18.

- Lin X, Wang L, Zhang Y, et al. Variable Ki67 proliferative index in 65 cases of nodular fasciitis, compared with fibrosarcoma and fibromatosis. Diagn Pathol. 2013;8:50.

- Goldstein J, Cates J. Differential diagnostic considerations of desmoid-type fibromatosis. Adv Anat Pathol. 2015;22:260-266.

- Fletcher CDM, Bridge JA, Hogendoorn PCW, et al, eds. WHO Classification of Tumours of Soft Tissue and Bone. 4th ed. Lyons, France: IARC Press; 2013.

- Bridge JA, Cushman-Vokoun AM. Molecular diagnostics of soft tissue tumors. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2011;135:588-601.

- Anzeljc AJ, Oliveira AM, Grossniklaus HE, et al. Nodular fasciitis of the orbit: a case report confirmed by molecular cytogenetic analysis. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017;33(3S suppl 1):S152-S155.

- de Paula SA, Cruz AA, de Alencar VM, et al. Nodular fasciitis presenting as a large mass in the upper eyelid. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;22:494-495.

- Bernstein KE, Lattes R. Nodular (pseudosarcomatous) fasciitis, a nonrecurrent lesion: clinicopathologic study of 134 cases. Cancer. 1982;49:1668-1678.

- Shimizu S, Hashimoto H, Enjoji M. Nodular fasciitis: an analysis of 250 patients. Pathology. 1984;16:161-166.

- Erickson-Johnson MR, Chou MM, Evers BR, et al. Nodular fasciitis: a novel model of transient neoplasia induced by MYH9-USP6 gene fusion. Lab Invest. 2011;91:1427-1433.

- Amary MF, Ye H, Berisha F, et al. Detection of USP6 gene rearrangement in nodular fasciitis: an important diagnostic tool. Virchows Arch. 2013;463:97-98.

- Wirth L, Klein A, Baur-Melnyk A. Desmoid tumors of the extremity and trunk. a retrospective study of 44 patients. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2018;19:2.

- Carlson JW, Fletcher CD. Immunohistochemistry for beta-catenin in the differential diagnosis of spindle cells lesions: analysis of a series and review of the literature. Histopathology. 2007;51:509-514.

- Mohamed M, Fisher C, Thway K. Low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma: clinical, morphologic and genetic features. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2017;28:60-67.

- Taher A, Pushpanathan C. Plexiform fibrohistiocytic tumor: a brief review. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2007;131:1135-1138.

- Shin C, Low I, Ng D, et al. USP6 gene rearrangement in nodular fasciitis and histological mimics. Histopathology. 2016;69:784-791.

- Kumar E, Patel NR, Demicco EG, et al. Cutaneous nodular fasciitis with genetic analysis: a case series. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:1143-1149.

- Nishio J. Updates on the cytogenetics and molecular cytogenetics of benign and intermediate soft tissue tumors. Oncol Lett. 2013;5:12-18.

- Lin X, Wang L, Zhang Y, et al. Variable Ki67 proliferative index in 65 cases of nodular fasciitis, compared with fibrosarcoma and fibromatosis. Diagn Pathol. 2013;8:50.

- Goldstein J, Cates J. Differential diagnostic considerations of desmoid-type fibromatosis. Adv Anat Pathol. 2015;22:260-266.

- Fletcher CDM, Bridge JA, Hogendoorn PCW, et al, eds. WHO Classification of Tumours of Soft Tissue and Bone. 4th ed. Lyons, France: IARC Press; 2013.

- Bridge JA, Cushman-Vokoun AM. Molecular diagnostics of soft tissue tumors. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2011;135:588-601.

- Anzeljc AJ, Oliveira AM, Grossniklaus HE, et al. Nodular fasciitis of the orbit: a case report confirmed by molecular cytogenetic analysis. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017;33(3S suppl 1):S152-S155.

- de Paula SA, Cruz AA, de Alencar VM, et al. Nodular fasciitis presenting as a large mass in the upper eyelid. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;22:494-495.

- Bernstein KE, Lattes R. Nodular (pseudosarcomatous) fasciitis, a nonrecurrent lesion: clinicopathologic study of 134 cases. Cancer. 1982;49:1668-1678.

- Shimizu S, Hashimoto H, Enjoji M. Nodular fasciitis: an analysis of 250 patients. Pathology. 1984;16:161-166.

- Erickson-Johnson MR, Chou MM, Evers BR, et al. Nodular fasciitis: a novel model of transient neoplasia induced by MYH9-USP6 gene fusion. Lab Invest. 2011;91:1427-1433.

- Amary MF, Ye H, Berisha F, et al. Detection of USP6 gene rearrangement in nodular fasciitis: an important diagnostic tool. Virchows Arch. 2013;463:97-98.

- Wirth L, Klein A, Baur-Melnyk A. Desmoid tumors of the extremity and trunk. a retrospective study of 44 patients. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2018;19:2.

- Carlson JW, Fletcher CD. Immunohistochemistry for beta-catenin in the differential diagnosis of spindle cells lesions: analysis of a series and review of the literature. Histopathology. 2007;51:509-514.

- Mohamed M, Fisher C, Thway K. Low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma: clinical, morphologic and genetic features. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2017;28:60-67.

- Taher A, Pushpanathan C. Plexiform fibrohistiocytic tumor: a brief review. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2007;131:1135-1138.

A 16-year-old adolescent girl presented with a bump over the left posterior knee of 1 month's duration. Her medical history was unremarkable. She denied recent trauma or injury to the area. On physical examination there was a visible and palpable tense nontender mass the size of an egg over the left posterior knee. Magnetic resonance imaging showed a lobulated mass-like focus of T2 hyperintensity centered at the subcutaneous tissues and superficial myofascial plane of the gastrocnemius on the posterior knee. Complete excision of the lesion was performed and demonstrated a 2.6.2 ×2.9.2 ×2.1-cm mass within subcutaneous adipose tissue. There was no microscopic involvement of skeletal muscle. Immunohistochemistry staining of the tumor was performed that was positive for smooth muscle actin and negative for desmin, S-100, CD34, pan-cytokeratin, and β-catenin. Fluorescent in situ hybridization testing demonstrated rearrangement of the ubiquitin-specific peptidase 6 gene, USP6, locus (17p13).

Pseudomyogenic Hemangioendothelioma

Pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma (PMHE), also referred to as epithelioid sarcoma–like hemangioendothelioma,1 is a rare soft tissue tumor that was described in 1992 by Mirra et al2 as a fibromalike variant of epithelioid sarcoma. It predominantly affects males between the second and fifth decades of life and most commonly presents as multiple nodules that may involve either the superficial or deep soft tissues of the legs and less often the arms. It also can arise on the trunk. We present a case of PMHE occurring in a young man and briefly review the literature on clinical presentation and histologic differentiation of this unique tumor, comparing these findings to its mimickers.

Case Report

A 20-year-old man presented with skin lesions on the left leg that had been present for 1 year. The patient described the lesions as tender pimples that would drain yellow discharge on occasion but had now transformed into large brown plaques. Physical examination showed 4 verrucous plaques ranging in size from 1 to 3 cm with hyperpigmentation and a central crust (Figure 1). Initially, the patient thought the lesions appeared due to shaving his legs for sports. He presented to the emergency department multiple times over the past year; pain control was provided and local skin care was recommended. Culture of the discharge had been performed 6 months prior to biopsy with negative results. No biopsy was performed on initial presentation and the lesions were diagnosed in the emergency department clinically as boils.

After failing to improve, the patient was seen by an outside dermatologist and the clinical differential diagnosis included deep fungal infection, atypical mycobacterial infection, and keloids. A 4-mm punch biopsy was taken from the periphery of one of the lesions and demonstrated hyperkeratosis, papillomatosis, and acanthosis (Figure 2). Within the superficial and deep dermis and focally extending into the subcutaneous tissue, there were sheets of spindled to epithelioid-appearing cells with moderate cytologic atypia (Figure 3). The tumor showed infiltrative margins. There was moderate cellularity. The individual cells had a rhabdoid appearance with large eccentric vesicular nuclei, prominent nucleoli, and abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm (Figure 4). No definitive evidence of glandular, squamous, or vascular differentiation was present. There was an associated moderate inflammatory host response composed of neutrophils and lymphocytes. Occasional extravasated red blood cells were present. Immunohistochemistry staining was performed and the atypical cells demonstrated diffuse positive staining for friend leukemia integration 1 transcription factor (FLI-1), erythroblastosis virus E26 transforming sequence-related gene (ERG)(Figure 5), CD31, and CD68. There was patchy positive staining for cytokeratin AE1/AE3, CD10, and factor VIII. There was no remarkable staining for human herpesvirus 8, epithelial membrane antigen, S-100, CD34, cytokeratin 903, and desmin. Overall, the histologic features in conjunction with the immunohistochemistry staining were consistent with a diagnosis of PMHE.

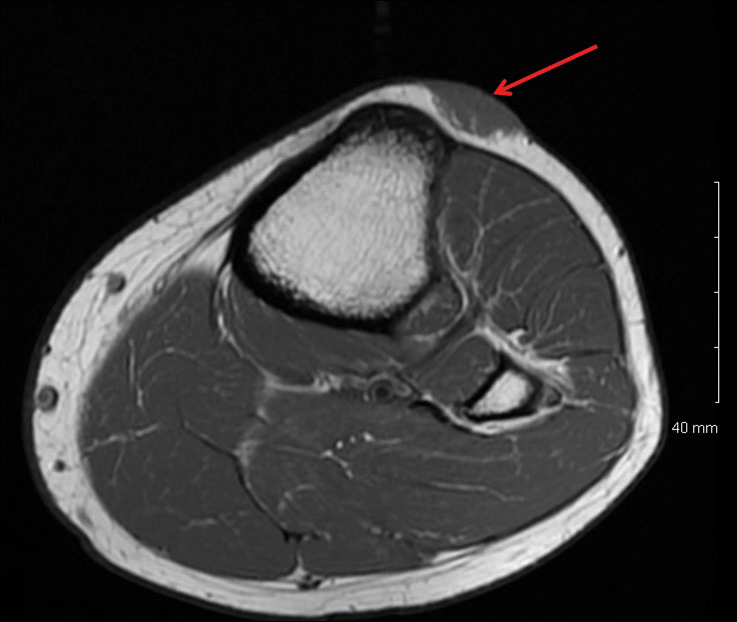

Magnetic resonance imaging was then performed to evaluate the depth and extent of the lesions for surgical excision planning (Figure 6), which showed 5 nodular lesions within the dermis and subcutis adjacent to the proximal aspect of the left tibia and medial aspect of the left knee. An additional lesion was noted between the sartorius and semimembranosus muscles, which was thought to represent either a lymph node or an additional neoplastic lesion. Chest computed tomography also displayed indeterminate lesions in the lungs.

Excision of the superficial lesions was performed. All of the lesions demonstrated similar histologic changes to the previously described biopsy specimen. The tumor was limited to the dermis and subcutaneous tissue. The patient was lost to follow-up and the etiology of the lung lesions was unknown.

Comment

Nomenclature

Pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma is a relatively new type of vascular tumor that has been included in the updated 2013 edition of the World Health Organization classification as an intermediate malignant tumor that rarely metastasizes.3 It typically involves multiple tissue planes, most notably the dermis and subcutaneous layers but also muscle and bone.4 The term pseudomyogenic refers to the histologic resemblance of some of the cells to rhabdomyoblasts; however, these tumors are negative for all immunohistochemical muscle markers, most notably myogenin, desmin, and α-smooth muscle actin.5

Clinical Presentation

Gross features of PMHE typically include multiple firm nodules with ill-defined margins. The tumor was initially described in 1992 by Mirra et al2 as a fibromalike variant of epithelioid sarcoma. In 2003, a series of 7 cases of PMHE was reported by Billings et al6 under the term epithelioid sarcomalike hemangioendothelioma. Other than the predominance of an epithelioid morphology, the cases reported as epithelioid sarcomalike hemangioendothelioma had similar clinical features and immunophenotype to what has been reported as PMHE.

Based on a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the term pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma, the 2 largest case series were reported by Pradhan et al7 (N=8) in 2017 and Hornick and Fletcher4 (N=50) in 2011. Hornick and Fletcher4 reported a male (41/50 [82.0%]) to female (9/50 [18.0%]) ratio of 4.6 to 1, and an average age at presentation of 31 years with 82% (41/50) of patients 40 years or younger. Pradhan et al7 also reported a male predominance (7/8 [87.5%]) with a similar average age at presentation of 29 years (age range, 9–62 years). The size of individual tumors ranged from 0.3 to 5.5 cm (mean size, 1.9 cm) in the series by Hornick and Fletcher4 and 0.3 to 6.0 com in the series by Pradhan et al.7 Hornick and Fletcher4 reported the most common site of involvement was the leg (27/50 [54.0%]), followed by the arm (12/50 [24.0%]), trunk (9/50 [18.0%]), and head and neck (2/50 [4.0%]). The leg (6/8 [75.0%]) also was the most common site of involvement in the series by Pradhan et al,7 with 2 cases occurring on the arm. In the series by Hornick and Fletcher,4 the tumors typically involved the dermis and subcutaneous tissue (26/50 [52%]) with a smaller number involving skeletal muscle (17/50 [34%]) and bone (7/50 [14%]). They reported 66% of their patients (33/50) had multifocal disease at presentation.4 Pradhan et al7 also reported 2 (25.0%) cases being limited to the superficial soft tissue, 2 (25.0%) being limited to the deep soft tissue, and 4 (50.0%) involving the bone; 5 (62.5%) patients had multifocal disease at presentation. The presentation of our patient in regards to gender, age, and tumor characteristics is consistent with other published cases.5-10

Histopathology

Microscopic features of PMHE include sheets of spindled to epithelioid-appearing cells with mild to moderate nuclear atypia and eosinophilic cytoplasm. The tumor has an infiltrative growth pattern. Some of the cells may resemble rhabdomyoblastlike cells, hence the moniker pseudomyogenic. There is no recapitulation of vascular structures or remarkable cytoplasmic vacuolization. Mitotic rate is low and there is no tumor necrosis.4 The tumor cells do not appear to arise from a vessel or display an angiocentric growth pattern. Many cases report the presence of an inflammatory infiltrate containing neutrophils interspersed within the tumor.4,5,7 The overlying epidermis will commonly show hyperkeratosis, epidermal hyperplasia, and acanthosis.4,11

Differential Diagnosis

The histopathologic differential diagnosis would include epithelioid sarcoma, epithelioid hemangioendothelioma, and to a lesser extent dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP) and rhabdomyosarcoma. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans is the most commonly encountered of these tumors. Histologically, DFSP is characterized by a cellular proliferation of small spindle cells with plump nuclei arranged in a storiform or cartwheel pattern. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans tends to be limited to the dermis and subcutaneous tissue and only rarely involves underlying skeletal muscle. The presence of the storiform growth pattern in conjunction with the lack of rhabdoid changes would favor a diagnosis of DFSP. Another characteristic histologic finding typically only associated with DFSP is the interdigitating growth pattern of the spindle cells within the lobules of the subcutaneous tissue, creating a lacelike or honeycomb appearance.

Immunohistochemistry staining is necessary to help differentiate PMHE from other tumors in the differential diagnosis. Pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma stains positive for cytokeratin AE1/AE3; integrase interactor 1; and vascular markers FLI-1, CD31, and ERG, and negative for CD34.4,6,12-15 In contrast to epithelioid hemangioendothelioma, DFSP, and to a lesser extent epithelioid sarcoma, all of which are positive for CD34, epithelioid sarcoma is negative for both CD31 and integrase interactor 1. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans is negative for cytokeratin AE1/AE3. Rhabdomyosarcomas are positive for myogenic markers such as MyoD1 and myogenin, unlike any of the other tumors mentioned. Histologically, epithelioid sarcomas will tend to have a granulomalike growth pattern with central necrosis, unlike PMHE.12 Epithelioid hemangioendothelioma often will have a cordlike growth pattern in a myxochondroid background. Unlike PMHE, these tumors often will appear to be arising from vessels, and intracytoplasmic vacuoles are common. Three cases of PMHE have been reported to have a t(7;19)(q22;q13) chromosomal anomaly, which is not consistent with every case.16

Treatment Options

Standard treatment typically includes wide excision of the lesions, as was done in our case. Because of the substantial risk of local recurrence, which was up to 58% in the series by Hornick and Fletcher,4 adjuvant therapy may be considered if positive margins are found on excision. Metastasis to lymph nodes and the lungs has been reported but is rare.2,4 Most cases have been shown to have a favorable prognosis; however, local recurrence seems to be common. Rarely, amputation of the limb may be required.5 In contrast, epithelioid sarcomas have been found to spread to lymph nodes and the lungs in up to 50% of cases with a 5-year survival rate of 10% to 30%.13

Conclusion

In summary, we describe a case of PMHE involving the lower leg in a 20-year-old man. These tumors often are multinodular and multiplanar, with the dermis and subcutaneous tissues being the most common areas affected. It has a high rate of local recurrence but rarely has distant metastasis. Pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma, similar to other soft tissue tumors, can be difficult to diagnose on shave biopsy or superficial punch biopsy not extending into subcutaneous tissue. Deep incisional or punch biopsies are required to more definitively diagnose these types of tumors. The diagnosis of PMHE versus other soft tissue tumors requires correlation of histology and immunohistochemistry staining with clinical information and radiographic findings.

- Billings SD, Folpe AL, Weiss SW. Epithelioid sarcoma-like hemangioendothelioma (pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma). Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35:1088; author reply 1088-1089.

- Mirra JM, Kessler S, Bhuta S, et al. The fibroma-like variant of epithelioid sarcoma. a fibrohistiocytic/myoid cell lesion often confused with benign and malignant spindle cell tumors. Cancer. 1992;69:1382-1395.

- Jo VY, Fletcher CD. WHO classification of soft tissue tumours: an update based on the 2013 (4th) edition. Pathology. 2014;46:95-104.

- Hornick JL, Fletcher CD. Pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma: a distinctive, often multicentric tumor with indolent behavior. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35:190-201.

- Sheng W, Pan Y, Wang J. Pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma: report of an additional case with aggressive clinical course. Am J Dermatopathol. 2013;35:597-600.

- Billings SD, Folpe AL, Weiss SW. Epithelioid sarcoma-like hemangioendothelioma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27:48-57.

- Pradhan D, Schoedel K, McGough RL, et al. Pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma of skin, bone and soft tissue—a clinicopathological, immunohistochemical and fluorescence in situ hybridization study [published online November 2, 2017]. Hum Pathol. 2017. doi:0.1016/j.humpath.2017.10.023.

- Requena L, Santonja C, Martinez-Amo JL, et al. Cutaneous epithelioid sarcoma like (pseudomyogenic) hemangioendothelioma: a little-known low-grade cutaneous vascular neoplasm. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:459-465.

- McGinity M, Bartanusz V, Dengler B, et al. Pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma (epithelioid sarcoma-like hemangioendothelioma, fibroma-like variant of epithelioid sarcoma) of the thoracic spine. Eur Spine J. 2013;22(suppl 3):S506-S511.

- Stuart LN, Gardner JM, Lauer SR, et al. Epithelioid sarcoma-like (pseudomyogenic) hemangioendothelioma, clinically mimicking dermatofibroma, diagnosed by skin biopsy in a 30-year-old man. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:909-913.

- Amary MF, O’Donnell P, Berisha F, et al. Pseudomyogenic (epithelioid sarcoma-like) hemangioendothelioma: characterization of five cases. Skeletal Radiol. 2013;42:947-957.

- Hornick JL, Dal Cin P, Fletcher CD. Loss of INI1 expression is characteristic of both conventional and proximal-type epithelioid sarcoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33:542-550.

- Chbani L, Guillou L, Terrier P, et al. Epithelioid sarcoma: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical analysis of 106 cases from the French Sarcoma Group. Am J Clin Pathol. 2009;131:222-227.

- Fisher C. Epithelioid sarcoma of Enzinger. Adv Anat Pathol. 2006;13:114-121.

- Requena L, Santonja C, Martinez-Amo JL, et al. Cutaneous epithelioid sarcoma like (pseudomyogenic) hemangioendothelioma: a little-known low-grade cutaneous vascular neoplasm. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:459-465.

- Trombetta D, Magnusson L, von Steyern FV, et al. Translocation t(7;19)(q22;q13)—a recurrent chromosome aberration in pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma? Cancer Genet. 2011;204:211-215.

Pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma (PMHE), also referred to as epithelioid sarcoma–like hemangioendothelioma,1 is a rare soft tissue tumor that was described in 1992 by Mirra et al2 as a fibromalike variant of epithelioid sarcoma. It predominantly affects males between the second and fifth decades of life and most commonly presents as multiple nodules that may involve either the superficial or deep soft tissues of the legs and less often the arms. It also can arise on the trunk. We present a case of PMHE occurring in a young man and briefly review the literature on clinical presentation and histologic differentiation of this unique tumor, comparing these findings to its mimickers.

Case Report

A 20-year-old man presented with skin lesions on the left leg that had been present for 1 year. The patient described the lesions as tender pimples that would drain yellow discharge on occasion but had now transformed into large brown plaques. Physical examination showed 4 verrucous plaques ranging in size from 1 to 3 cm with hyperpigmentation and a central crust (Figure 1). Initially, the patient thought the lesions appeared due to shaving his legs for sports. He presented to the emergency department multiple times over the past year; pain control was provided and local skin care was recommended. Culture of the discharge had been performed 6 months prior to biopsy with negative results. No biopsy was performed on initial presentation and the lesions were diagnosed in the emergency department clinically as boils.

After failing to improve, the patient was seen by an outside dermatologist and the clinical differential diagnosis included deep fungal infection, atypical mycobacterial infection, and keloids. A 4-mm punch biopsy was taken from the periphery of one of the lesions and demonstrated hyperkeratosis, papillomatosis, and acanthosis (Figure 2). Within the superficial and deep dermis and focally extending into the subcutaneous tissue, there were sheets of spindled to epithelioid-appearing cells with moderate cytologic atypia (Figure 3). The tumor showed infiltrative margins. There was moderate cellularity. The individual cells had a rhabdoid appearance with large eccentric vesicular nuclei, prominent nucleoli, and abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm (Figure 4). No definitive evidence of glandular, squamous, or vascular differentiation was present. There was an associated moderate inflammatory host response composed of neutrophils and lymphocytes. Occasional extravasated red blood cells were present. Immunohistochemistry staining was performed and the atypical cells demonstrated diffuse positive staining for friend leukemia integration 1 transcription factor (FLI-1), erythroblastosis virus E26 transforming sequence-related gene (ERG)(Figure 5), CD31, and CD68. There was patchy positive staining for cytokeratin AE1/AE3, CD10, and factor VIII. There was no remarkable staining for human herpesvirus 8, epithelial membrane antigen, S-100, CD34, cytokeratin 903, and desmin. Overall, the histologic features in conjunction with the immunohistochemistry staining were consistent with a diagnosis of PMHE.

Magnetic resonance imaging was then performed to evaluate the depth and extent of the lesions for surgical excision planning (Figure 6), which showed 5 nodular lesions within the dermis and subcutis adjacent to the proximal aspect of the left tibia and medial aspect of the left knee. An additional lesion was noted between the sartorius and semimembranosus muscles, which was thought to represent either a lymph node or an additional neoplastic lesion. Chest computed tomography also displayed indeterminate lesions in the lungs.

Excision of the superficial lesions was performed. All of the lesions demonstrated similar histologic changes to the previously described biopsy specimen. The tumor was limited to the dermis and subcutaneous tissue. The patient was lost to follow-up and the etiology of the lung lesions was unknown.

Comment

Nomenclature

Pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma is a relatively new type of vascular tumor that has been included in the updated 2013 edition of the World Health Organization classification as an intermediate malignant tumor that rarely metastasizes.3 It typically involves multiple tissue planes, most notably the dermis and subcutaneous layers but also muscle and bone.4 The term pseudomyogenic refers to the histologic resemblance of some of the cells to rhabdomyoblasts; however, these tumors are negative for all immunohistochemical muscle markers, most notably myogenin, desmin, and α-smooth muscle actin.5

Clinical Presentation

Gross features of PMHE typically include multiple firm nodules with ill-defined margins. The tumor was initially described in 1992 by Mirra et al2 as a fibromalike variant of epithelioid sarcoma. In 2003, a series of 7 cases of PMHE was reported by Billings et al6 under the term epithelioid sarcomalike hemangioendothelioma. Other than the predominance of an epithelioid morphology, the cases reported as epithelioid sarcomalike hemangioendothelioma had similar clinical features and immunophenotype to what has been reported as PMHE.

Based on a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the term pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma, the 2 largest case series were reported by Pradhan et al7 (N=8) in 2017 and Hornick and Fletcher4 (N=50) in 2011. Hornick and Fletcher4 reported a male (41/50 [82.0%]) to female (9/50 [18.0%]) ratio of 4.6 to 1, and an average age at presentation of 31 years with 82% (41/50) of patients 40 years or younger. Pradhan et al7 also reported a male predominance (7/8 [87.5%]) with a similar average age at presentation of 29 years (age range, 9–62 years). The size of individual tumors ranged from 0.3 to 5.5 cm (mean size, 1.9 cm) in the series by Hornick and Fletcher4 and 0.3 to 6.0 com in the series by Pradhan et al.7 Hornick and Fletcher4 reported the most common site of involvement was the leg (27/50 [54.0%]), followed by the arm (12/50 [24.0%]), trunk (9/50 [18.0%]), and head and neck (2/50 [4.0%]). The leg (6/8 [75.0%]) also was the most common site of involvement in the series by Pradhan et al,7 with 2 cases occurring on the arm. In the series by Hornick and Fletcher,4 the tumors typically involved the dermis and subcutaneous tissue (26/50 [52%]) with a smaller number involving skeletal muscle (17/50 [34%]) and bone (7/50 [14%]). They reported 66% of their patients (33/50) had multifocal disease at presentation.4 Pradhan et al7 also reported 2 (25.0%) cases being limited to the superficial soft tissue, 2 (25.0%) being limited to the deep soft tissue, and 4 (50.0%) involving the bone; 5 (62.5%) patients had multifocal disease at presentation. The presentation of our patient in regards to gender, age, and tumor characteristics is consistent with other published cases.5-10

Histopathology

Microscopic features of PMHE include sheets of spindled to epithelioid-appearing cells with mild to moderate nuclear atypia and eosinophilic cytoplasm. The tumor has an infiltrative growth pattern. Some of the cells may resemble rhabdomyoblastlike cells, hence the moniker pseudomyogenic. There is no recapitulation of vascular structures or remarkable cytoplasmic vacuolization. Mitotic rate is low and there is no tumor necrosis.4 The tumor cells do not appear to arise from a vessel or display an angiocentric growth pattern. Many cases report the presence of an inflammatory infiltrate containing neutrophils interspersed within the tumor.4,5,7 The overlying epidermis will commonly show hyperkeratosis, epidermal hyperplasia, and acanthosis.4,11

Differential Diagnosis

The histopathologic differential diagnosis would include epithelioid sarcoma, epithelioid hemangioendothelioma, and to a lesser extent dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP) and rhabdomyosarcoma. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans is the most commonly encountered of these tumors. Histologically, DFSP is characterized by a cellular proliferation of small spindle cells with plump nuclei arranged in a storiform or cartwheel pattern. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans tends to be limited to the dermis and subcutaneous tissue and only rarely involves underlying skeletal muscle. The presence of the storiform growth pattern in conjunction with the lack of rhabdoid changes would favor a diagnosis of DFSP. Another characteristic histologic finding typically only associated with DFSP is the interdigitating growth pattern of the spindle cells within the lobules of the subcutaneous tissue, creating a lacelike or honeycomb appearance.

Immunohistochemistry staining is necessary to help differentiate PMHE from other tumors in the differential diagnosis. Pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma stains positive for cytokeratin AE1/AE3; integrase interactor 1; and vascular markers FLI-1, CD31, and ERG, and negative for CD34.4,6,12-15 In contrast to epithelioid hemangioendothelioma, DFSP, and to a lesser extent epithelioid sarcoma, all of which are positive for CD34, epithelioid sarcoma is negative for both CD31 and integrase interactor 1. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans is negative for cytokeratin AE1/AE3. Rhabdomyosarcomas are positive for myogenic markers such as MyoD1 and myogenin, unlike any of the other tumors mentioned. Histologically, epithelioid sarcomas will tend to have a granulomalike growth pattern with central necrosis, unlike PMHE.12 Epithelioid hemangioendothelioma often will have a cordlike growth pattern in a myxochondroid background. Unlike PMHE, these tumors often will appear to be arising from vessels, and intracytoplasmic vacuoles are common. Three cases of PMHE have been reported to have a t(7;19)(q22;q13) chromosomal anomaly, which is not consistent with every case.16

Treatment Options

Standard treatment typically includes wide excision of the lesions, as was done in our case. Because of the substantial risk of local recurrence, which was up to 58% in the series by Hornick and Fletcher,4 adjuvant therapy may be considered if positive margins are found on excision. Metastasis to lymph nodes and the lungs has been reported but is rare.2,4 Most cases have been shown to have a favorable prognosis; however, local recurrence seems to be common. Rarely, amputation of the limb may be required.5 In contrast, epithelioid sarcomas have been found to spread to lymph nodes and the lungs in up to 50% of cases with a 5-year survival rate of 10% to 30%.13

Conclusion

In summary, we describe a case of PMHE involving the lower leg in a 20-year-old man. These tumors often are multinodular and multiplanar, with the dermis and subcutaneous tissues being the most common areas affected. It has a high rate of local recurrence but rarely has distant metastasis. Pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma, similar to other soft tissue tumors, can be difficult to diagnose on shave biopsy or superficial punch biopsy not extending into subcutaneous tissue. Deep incisional or punch biopsies are required to more definitively diagnose these types of tumors. The diagnosis of PMHE versus other soft tissue tumors requires correlation of histology and immunohistochemistry staining with clinical information and radiographic findings.

Pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma (PMHE), also referred to as epithelioid sarcoma–like hemangioendothelioma,1 is a rare soft tissue tumor that was described in 1992 by Mirra et al2 as a fibromalike variant of epithelioid sarcoma. It predominantly affects males between the second and fifth decades of life and most commonly presents as multiple nodules that may involve either the superficial or deep soft tissues of the legs and less often the arms. It also can arise on the trunk. We present a case of PMHE occurring in a young man and briefly review the literature on clinical presentation and histologic differentiation of this unique tumor, comparing these findings to its mimickers.

Case Report

A 20-year-old man presented with skin lesions on the left leg that had been present for 1 year. The patient described the lesions as tender pimples that would drain yellow discharge on occasion but had now transformed into large brown plaques. Physical examination showed 4 verrucous plaques ranging in size from 1 to 3 cm with hyperpigmentation and a central crust (Figure 1). Initially, the patient thought the lesions appeared due to shaving his legs for sports. He presented to the emergency department multiple times over the past year; pain control was provided and local skin care was recommended. Culture of the discharge had been performed 6 months prior to biopsy with negative results. No biopsy was performed on initial presentation and the lesions were diagnosed in the emergency department clinically as boils.

After failing to improve, the patient was seen by an outside dermatologist and the clinical differential diagnosis included deep fungal infection, atypical mycobacterial infection, and keloids. A 4-mm punch biopsy was taken from the periphery of one of the lesions and demonstrated hyperkeratosis, papillomatosis, and acanthosis (Figure 2). Within the superficial and deep dermis and focally extending into the subcutaneous tissue, there were sheets of spindled to epithelioid-appearing cells with moderate cytologic atypia (Figure 3). The tumor showed infiltrative margins. There was moderate cellularity. The individual cells had a rhabdoid appearance with large eccentric vesicular nuclei, prominent nucleoli, and abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm (Figure 4). No definitive evidence of glandular, squamous, or vascular differentiation was present. There was an associated moderate inflammatory host response composed of neutrophils and lymphocytes. Occasional extravasated red blood cells were present. Immunohistochemistry staining was performed and the atypical cells demonstrated diffuse positive staining for friend leukemia integration 1 transcription factor (FLI-1), erythroblastosis virus E26 transforming sequence-related gene (ERG)(Figure 5), CD31, and CD68. There was patchy positive staining for cytokeratin AE1/AE3, CD10, and factor VIII. There was no remarkable staining for human herpesvirus 8, epithelial membrane antigen, S-100, CD34, cytokeratin 903, and desmin. Overall, the histologic features in conjunction with the immunohistochemistry staining were consistent with a diagnosis of PMHE.

Magnetic resonance imaging was then performed to evaluate the depth and extent of the lesions for surgical excision planning (Figure 6), which showed 5 nodular lesions within the dermis and subcutis adjacent to the proximal aspect of the left tibia and medial aspect of the left knee. An additional lesion was noted between the sartorius and semimembranosus muscles, which was thought to represent either a lymph node or an additional neoplastic lesion. Chest computed tomography also displayed indeterminate lesions in the lungs.

Excision of the superficial lesions was performed. All of the lesions demonstrated similar histologic changes to the previously described biopsy specimen. The tumor was limited to the dermis and subcutaneous tissue. The patient was lost to follow-up and the etiology of the lung lesions was unknown.

Comment

Nomenclature

Pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma is a relatively new type of vascular tumor that has been included in the updated 2013 edition of the World Health Organization classification as an intermediate malignant tumor that rarely metastasizes.3 It typically involves multiple tissue planes, most notably the dermis and subcutaneous layers but also muscle and bone.4 The term pseudomyogenic refers to the histologic resemblance of some of the cells to rhabdomyoblasts; however, these tumors are negative for all immunohistochemical muscle markers, most notably myogenin, desmin, and α-smooth muscle actin.5

Clinical Presentation

Gross features of PMHE typically include multiple firm nodules with ill-defined margins. The tumor was initially described in 1992 by Mirra et al2 as a fibromalike variant of epithelioid sarcoma. In 2003, a series of 7 cases of PMHE was reported by Billings et al6 under the term epithelioid sarcomalike hemangioendothelioma. Other than the predominance of an epithelioid morphology, the cases reported as epithelioid sarcomalike hemangioendothelioma had similar clinical features and immunophenotype to what has been reported as PMHE.

Based on a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the term pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma, the 2 largest case series were reported by Pradhan et al7 (N=8) in 2017 and Hornick and Fletcher4 (N=50) in 2011. Hornick and Fletcher4 reported a male (41/50 [82.0%]) to female (9/50 [18.0%]) ratio of 4.6 to 1, and an average age at presentation of 31 years with 82% (41/50) of patients 40 years or younger. Pradhan et al7 also reported a male predominance (7/8 [87.5%]) with a similar average age at presentation of 29 years (age range, 9–62 years). The size of individual tumors ranged from 0.3 to 5.5 cm (mean size, 1.9 cm) in the series by Hornick and Fletcher4 and 0.3 to 6.0 com in the series by Pradhan et al.7 Hornick and Fletcher4 reported the most common site of involvement was the leg (27/50 [54.0%]), followed by the arm (12/50 [24.0%]), trunk (9/50 [18.0%]), and head and neck (2/50 [4.0%]). The leg (6/8 [75.0%]) also was the most common site of involvement in the series by Pradhan et al,7 with 2 cases occurring on the arm. In the series by Hornick and Fletcher,4 the tumors typically involved the dermis and subcutaneous tissue (26/50 [52%]) with a smaller number involving skeletal muscle (17/50 [34%]) and bone (7/50 [14%]). They reported 66% of their patients (33/50) had multifocal disease at presentation.4 Pradhan et al7 also reported 2 (25.0%) cases being limited to the superficial soft tissue, 2 (25.0%) being limited to the deep soft tissue, and 4 (50.0%) involving the bone; 5 (62.5%) patients had multifocal disease at presentation. The presentation of our patient in regards to gender, age, and tumor characteristics is consistent with other published cases.5-10

Histopathology

Microscopic features of PMHE include sheets of spindled to epithelioid-appearing cells with mild to moderate nuclear atypia and eosinophilic cytoplasm. The tumor has an infiltrative growth pattern. Some of the cells may resemble rhabdomyoblastlike cells, hence the moniker pseudomyogenic. There is no recapitulation of vascular structures or remarkable cytoplasmic vacuolization. Mitotic rate is low and there is no tumor necrosis.4 The tumor cells do not appear to arise from a vessel or display an angiocentric growth pattern. Many cases report the presence of an inflammatory infiltrate containing neutrophils interspersed within the tumor.4,5,7 The overlying epidermis will commonly show hyperkeratosis, epidermal hyperplasia, and acanthosis.4,11

Differential Diagnosis

The histopathologic differential diagnosis would include epithelioid sarcoma, epithelioid hemangioendothelioma, and to a lesser extent dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP) and rhabdomyosarcoma. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans is the most commonly encountered of these tumors. Histologically, DFSP is characterized by a cellular proliferation of small spindle cells with plump nuclei arranged in a storiform or cartwheel pattern. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans tends to be limited to the dermis and subcutaneous tissue and only rarely involves underlying skeletal muscle. The presence of the storiform growth pattern in conjunction with the lack of rhabdoid changes would favor a diagnosis of DFSP. Another characteristic histologic finding typically only associated with DFSP is the interdigitating growth pattern of the spindle cells within the lobules of the subcutaneous tissue, creating a lacelike or honeycomb appearance.

Immunohistochemistry staining is necessary to help differentiate PMHE from other tumors in the differential diagnosis. Pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma stains positive for cytokeratin AE1/AE3; integrase interactor 1; and vascular markers FLI-1, CD31, and ERG, and negative for CD34.4,6,12-15 In contrast to epithelioid hemangioendothelioma, DFSP, and to a lesser extent epithelioid sarcoma, all of which are positive for CD34, epithelioid sarcoma is negative for both CD31 and integrase interactor 1. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans is negative for cytokeratin AE1/AE3. Rhabdomyosarcomas are positive for myogenic markers such as MyoD1 and myogenin, unlike any of the other tumors mentioned. Histologically, epithelioid sarcomas will tend to have a granulomalike growth pattern with central necrosis, unlike PMHE.12 Epithelioid hemangioendothelioma often will have a cordlike growth pattern in a myxochondroid background. Unlike PMHE, these tumors often will appear to be arising from vessels, and intracytoplasmic vacuoles are common. Three cases of PMHE have been reported to have a t(7;19)(q22;q13) chromosomal anomaly, which is not consistent with every case.16

Treatment Options

Standard treatment typically includes wide excision of the lesions, as was done in our case. Because of the substantial risk of local recurrence, which was up to 58% in the series by Hornick and Fletcher,4 adjuvant therapy may be considered if positive margins are found on excision. Metastasis to lymph nodes and the lungs has been reported but is rare.2,4 Most cases have been shown to have a favorable prognosis; however, local recurrence seems to be common. Rarely, amputation of the limb may be required.5 In contrast, epithelioid sarcomas have been found to spread to lymph nodes and the lungs in up to 50% of cases with a 5-year survival rate of 10% to 30%.13

Conclusion

In summary, we describe a case of PMHE involving the lower leg in a 20-year-old man. These tumors often are multinodular and multiplanar, with the dermis and subcutaneous tissues being the most common areas affected. It has a high rate of local recurrence but rarely has distant metastasis. Pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma, similar to other soft tissue tumors, can be difficult to diagnose on shave biopsy or superficial punch biopsy not extending into subcutaneous tissue. Deep incisional or punch biopsies are required to more definitively diagnose these types of tumors. The diagnosis of PMHE versus other soft tissue tumors requires correlation of histology and immunohistochemistry staining with clinical information and radiographic findings.

- Billings SD, Folpe AL, Weiss SW. Epithelioid sarcoma-like hemangioendothelioma (pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma). Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35:1088; author reply 1088-1089.

- Mirra JM, Kessler S, Bhuta S, et al. The fibroma-like variant of epithelioid sarcoma. a fibrohistiocytic/myoid cell lesion often confused with benign and malignant spindle cell tumors. Cancer. 1992;69:1382-1395.

- Jo VY, Fletcher CD. WHO classification of soft tissue tumours: an update based on the 2013 (4th) edition. Pathology. 2014;46:95-104.

- Hornick JL, Fletcher CD. Pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma: a distinctive, often multicentric tumor with indolent behavior. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35:190-201.

- Sheng W, Pan Y, Wang J. Pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma: report of an additional case with aggressive clinical course. Am J Dermatopathol. 2013;35:597-600.

- Billings SD, Folpe AL, Weiss SW. Epithelioid sarcoma-like hemangioendothelioma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27:48-57.

- Pradhan D, Schoedel K, McGough RL, et al. Pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma of skin, bone and soft tissue—a clinicopathological, immunohistochemical and fluorescence in situ hybridization study [published online November 2, 2017]. Hum Pathol. 2017. doi:0.1016/j.humpath.2017.10.023.

- Requena L, Santonja C, Martinez-Amo JL, et al. Cutaneous epithelioid sarcoma like (pseudomyogenic) hemangioendothelioma: a little-known low-grade cutaneous vascular neoplasm. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:459-465.

- McGinity M, Bartanusz V, Dengler B, et al. Pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma (epithelioid sarcoma-like hemangioendothelioma, fibroma-like variant of epithelioid sarcoma) of the thoracic spine. Eur Spine J. 2013;22(suppl 3):S506-S511.

- Stuart LN, Gardner JM, Lauer SR, et al. Epithelioid sarcoma-like (pseudomyogenic) hemangioendothelioma, clinically mimicking dermatofibroma, diagnosed by skin biopsy in a 30-year-old man. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:909-913.

- Amary MF, O’Donnell P, Berisha F, et al. Pseudomyogenic (epithelioid sarcoma-like) hemangioendothelioma: characterization of five cases. Skeletal Radiol. 2013;42:947-957.

- Hornick JL, Dal Cin P, Fletcher CD. Loss of INI1 expression is characteristic of both conventional and proximal-type epithelioid sarcoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33:542-550.

- Chbani L, Guillou L, Terrier P, et al. Epithelioid sarcoma: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical analysis of 106 cases from the French Sarcoma Group. Am J Clin Pathol. 2009;131:222-227.

- Fisher C. Epithelioid sarcoma of Enzinger. Adv Anat Pathol. 2006;13:114-121.

- Requena L, Santonja C, Martinez-Amo JL, et al. Cutaneous epithelioid sarcoma like (pseudomyogenic) hemangioendothelioma: a little-known low-grade cutaneous vascular neoplasm. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:459-465.

- Trombetta D, Magnusson L, von Steyern FV, et al. Translocation t(7;19)(q22;q13)—a recurrent chromosome aberration in pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma? Cancer Genet. 2011;204:211-215.

- Billings SD, Folpe AL, Weiss SW. Epithelioid sarcoma-like hemangioendothelioma (pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma). Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35:1088; author reply 1088-1089.

- Mirra JM, Kessler S, Bhuta S, et al. The fibroma-like variant of epithelioid sarcoma. a fibrohistiocytic/myoid cell lesion often confused with benign and malignant spindle cell tumors. Cancer. 1992;69:1382-1395.

- Jo VY, Fletcher CD. WHO classification of soft tissue tumours: an update based on the 2013 (4th) edition. Pathology. 2014;46:95-104.

- Hornick JL, Fletcher CD. Pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma: a distinctive, often multicentric tumor with indolent behavior. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35:190-201.

- Sheng W, Pan Y, Wang J. Pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma: report of an additional case with aggressive clinical course. Am J Dermatopathol. 2013;35:597-600.

- Billings SD, Folpe AL, Weiss SW. Epithelioid sarcoma-like hemangioendothelioma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27:48-57.

- Pradhan D, Schoedel K, McGough RL, et al. Pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma of skin, bone and soft tissue—a clinicopathological, immunohistochemical and fluorescence in situ hybridization study [published online November 2, 2017]. Hum Pathol. 2017. doi:0.1016/j.humpath.2017.10.023.

- Requena L, Santonja C, Martinez-Amo JL, et al. Cutaneous epithelioid sarcoma like (pseudomyogenic) hemangioendothelioma: a little-known low-grade cutaneous vascular neoplasm. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:459-465.

- McGinity M, Bartanusz V, Dengler B, et al. Pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma (epithelioid sarcoma-like hemangioendothelioma, fibroma-like variant of epithelioid sarcoma) of the thoracic spine. Eur Spine J. 2013;22(suppl 3):S506-S511.

- Stuart LN, Gardner JM, Lauer SR, et al. Epithelioid sarcoma-like (pseudomyogenic) hemangioendothelioma, clinically mimicking dermatofibroma, diagnosed by skin biopsy in a 30-year-old man. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:909-913.

- Amary MF, O’Donnell P, Berisha F, et al. Pseudomyogenic (epithelioid sarcoma-like) hemangioendothelioma: characterization of five cases. Skeletal Radiol. 2013;42:947-957.

- Hornick JL, Dal Cin P, Fletcher CD. Loss of INI1 expression is characteristic of both conventional and proximal-type epithelioid sarcoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33:542-550.

- Chbani L, Guillou L, Terrier P, et al. Epithelioid sarcoma: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical analysis of 106 cases from the French Sarcoma Group. Am J Clin Pathol. 2009;131:222-227.

- Fisher C. Epithelioid sarcoma of Enzinger. Adv Anat Pathol. 2006;13:114-121.

- Requena L, Santonja C, Martinez-Amo JL, et al. Cutaneous epithelioid sarcoma like (pseudomyogenic) hemangioendothelioma: a little-known low-grade cutaneous vascular neoplasm. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:459-465.

- Trombetta D, Magnusson L, von Steyern FV, et al. Translocation t(7;19)(q22;q13)—a recurrent chromosome aberration in pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma? Cancer Genet. 2011;204:211-215.

Practice Points

- Pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma (PMHE) is an uncommon vascular tumor that most often presents as multiple distinct nodules on the legs in young men.

- Pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma has an unusual immunohistochemistry staining pattern, with positive staining for cytokeratin AE1/AE3, CD31, and ERG but negative for CD34.

- Although local reoccurrence is common, PMHE metastasis is very uncommon.

Melanotrichoblastoma: A Rare Pigmented Variant of Trichoblastoma

Trichoblastomas are rare cutaneous tumors that recapitulate the germinative hair bulb and the surrounding mesenchyme. Although benign, they can present diagnostic difficulties for both the clinician and pathologist because of their rarity and overlap both clinically and microscopically with other follicular neoplasms as well as basal cell carcinoma (BCC). Several classification schemes for hair follicle neoplasms have been established based on the relative proportions of epithelial and mesenchymal components as well as stromal inductive change, but nomenclature continues to be problematic, as individual neoplasms show varying degrees of differentiation that do not always uniformly fit within these categories.1,2 One of these established categories is a pigmented trichoblastoma.3 An exceedingly rare variant of a pigmented trichoblastoma referred to as melanotrichoblastoma was first described in 20024 and has only been documented in 3 cases, according to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the term melanotrichoblastoma.4-6 We report another case of this rare tumor and review the literature on this unique group of tumors.

Case Report

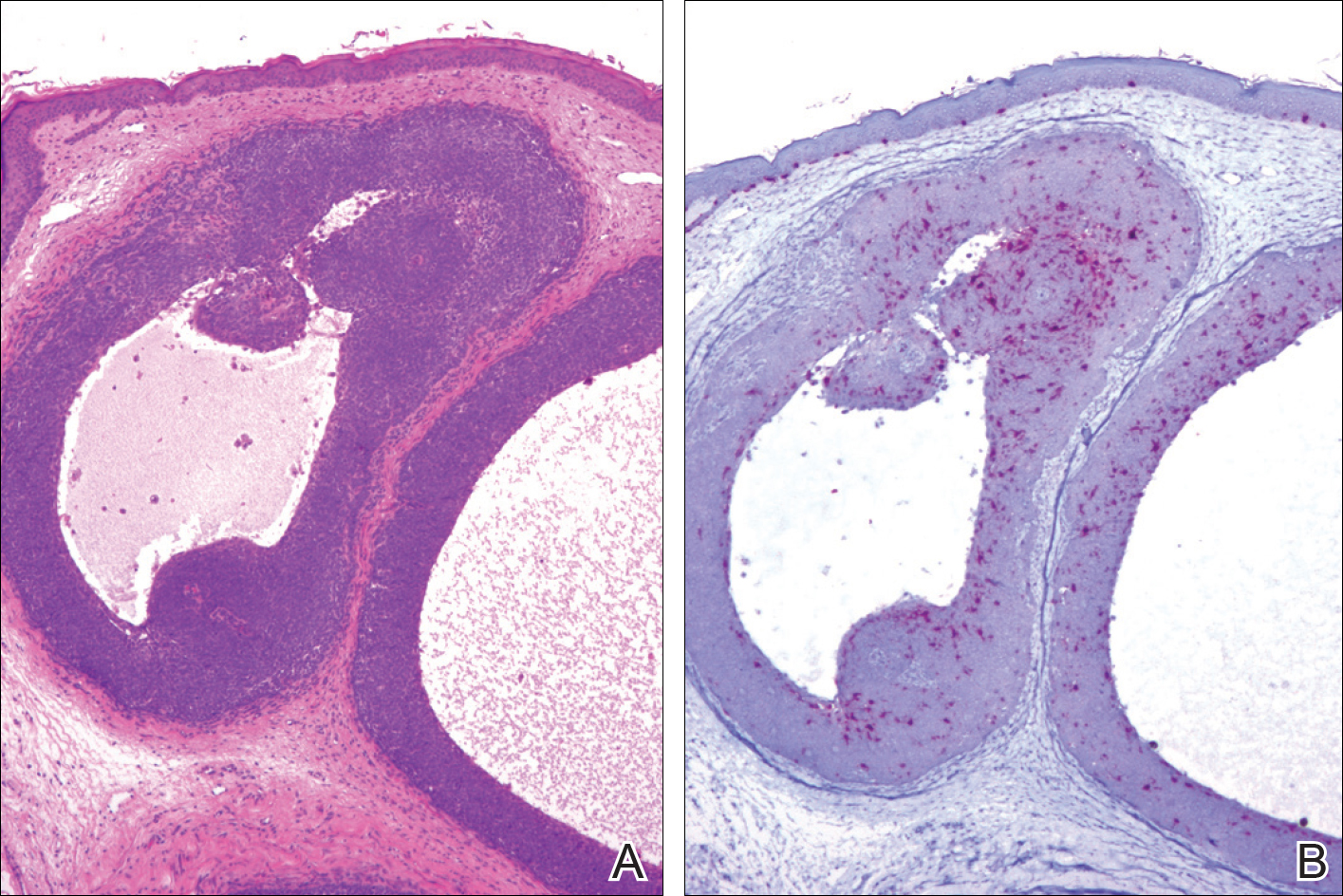

A 25-year-old white woman with a medical history of chronic migraines, myofascial syndrome, and Arnold-Chiari malformation type I presented to dermatology with a 1.5-cm, pedunculated, well-circumscribed tumor on the left side of the scalp (Figure 1). The tumor was grossly flesh colored with heterogeneous areas of dark pigmentation. Microscopic examination demonstrated that within the superficial and deep dermis were variable-sized nests of basaloid cells. Some of the nests had large central cystic spaces with brown pigment within some of these spaces and focal pigmentation of the basaloid cells (Figure 2A). Focal areas of keratinization were present. Mitotic figures were easily identified; however, no atypical mitotic figures were present. Areas of peripheral palisading were present but there was no retraction artifact. Connection to the overlying epidermis was not identified. Surrounding the basaloid nodules was a mildly cellular proliferation of cytologically bland spindle cells. Occasional pigment-laden macrophages were present in the dermis. Focal areas suggestive of papillary mesenchymal body formation were present (Figure 2B). Immunohistochemical staining for Melan-A was performed and demonstrated the presence of a prominent number of melanocytes in some of the nests (Figure 3) and minimal to no melanocytes in other nests. There was no evidence of a melanocytic lesion involving the overlying epidermis. Features of nevus sebaceus were not present. Immunohistochemical staining for cytokeratin (CK) 20 was performed and demonstrated no notable number of Merkel cells within the lesion.

Comment

Overview of Trichoblastomas

Trichoblastomas most often present as solitary, flesh-colored, well-circumscribed, slow-growing tumors that usually progress in size over months to years. Although they may be present at any age, they most commonly occur in adults in the fifth to seventh decades of life and are equally distributed between males and females.7,8 They most often occur on the head and neck with a predilection for the scalp. Although they behave in a benign fashion, cases of malignant trichoblastomas have been reported.9

Histopathology

Histologically, these tumors are well circumscribed but unencapsulated and usually located within the deep dermis, often with extension into the subcutaneous tissue. An epidermal connection is not identified. The tumor typically is composed of variable-sized nests of basaloid cells surrounded by a variable cellular stromal component. Although peripheral palisading is present in the basaloid component, retraction artifact is not present. Several histologic variants of trichoblastomas have been reported including cribriform, racemiform, retiform, pigmented, giant, subcutaneous, rippled pattern, and clear cell.5 Pigmented trichoblastomas are histologically similar to typical trichoblastomas, except for the presence of large amounts of melanin deposited within and around the tumor nests.6 A melanotrichoblastoma is a rare variant of a pigmented trichoblastoma; pigment is present in the lesion and melanocytes are identified within the basaloid nests.

The stromal component of trichoblastomas may show areas of condensation associated with some of the basaloid cells, resembling an attempt at hair bulb formation. Staining for CD10 will be positive in these areas of papillary mesenchymal bodies.10

In an immunohistochemical study of 13 cases of trichoblastomas, there was diffuse positive staining for CK14 and CK17 in all cases (similar to BCC) and positive staining for CK19 in 70% (9/13) of cases compared to 21% (4/19) of BCC cases. Staining for CK8 and CK20 demonstrated the presence of numerous Merkel cells in all trichoblastomas but in none of the 19 cases of BCC tested.11 However, other studies have reported the presence of Merkel cells in only 42% to 70% of trichoblastomas.12,13 Despite the lack of Merkel cells in our case, the lesion was interpreted as a melanotrichoblastoma based on the histologic features in conjunction with the presence of the melanocytes.

Differential Diagnosis

The clinical and histologic differential diagnosis of trichoblastomas includes both trichoepithelioma and BCC. Clinically, all 3 lesions often are slow growing, dome shaped, and small in size (several millimeters), and are observed in the same anatomic distribution of the head and neck region. Furthermore, they often affect middle-aged to older individuals and those of Caucasian descent, though other ethnicities can be affected. Histologic evaluation often is necessary to differentiate between these 3 entities.

Histologically, trichoepitheliomas are composed of nodules of basaloid cells encircled by stromal spindle cells. Although there can be histologic overlap between trichoepitheliomas and trichoblastoma, trichoepitheliomas typically will display obvious features of hair follicle differentiation with the presence of small keratinous cysts and hair bulb structures, while trichoblastomas tend to display minimal changes suggestive of its hair follicle origin. Similar to trichoblastomas, BCC is composed of nests of basaloid cells; however, BCCs often demonstrate retraction artifact and connection to the overlying epidermis. In addition, BCCs typically demonstrate a fibromucinous stromal component that is distinct from the cellular stroma of trichoblastic tumors. Immunoperoxidase staining for androgen receptors has been reported to be positive in 78% (25/32) of BCCs and negative in trichoblastic tumors.14

Melanotrichoblastoma Differentiating Characteristics

An exceedingly rare variant of pigmented trichoblastoma is the melanotrichoblastoma. There are clinical and histologic similarities and differences between the reported cases. The first case, described by Kanitakis et al,4 reported a 32-year-old black woman with a 2-cm scalp mass that slowly enlarged over the course of 2 years. The second case, presented by Kim et al,5 described a 51-year-old Korean man with a subcutaneous 6-cm mass on the back that had been present and slowly enlarging over the course of 5 years. The third case, reported by Hung et al,6 described a 34-year-old Taiwanese man with a 1-cm, left-sided, temporal scalp mass present for 3 years, arising from a nevus sebaceous. Comparing these clinical findings with our case of a 25-year-old white woman with a 1.5-cm mass on the left side of the scalp, melanotrichoblastomas demonstrate a relatively similar age of onset in the early to middle-aged adult years. All 4 tumors were slow growing. Additionally, 3 of 4 cases demonstrated a predilection for the head, particularly the scalp, and grossly showed well-circumscribed lesions with notable pigmentation. Although age, size, location, and gross appearance were similar, a comparable ethnic and gender demographic was not identified.

Microscopic similarities between the 4 cases were present. Each case was characterized by a large, well-circumscribed, unencapsulated, basaloid tumor present in the lower dermis, with only 1 case having tumor cells occasionally reaching the undersurface of the epidermis. The tumor cells were monomorphic round-ovoid in appearance with scant cytoplasm. There was melanin pigment in the basaloid nests. The basaloid nests were surrounded by a proliferation of stromal cells. The mitotic rate was sparse in 2 cases, brisk in 1 case, and not discussed in 1 case. Melanocytes were identified in the basaloid nests in all 4 cases; however, in the current case, the melanocytes were seen in only some of the nests. None of the cases exhibited an overlying junctional melanocytic lesion, which would argue against a possible collision tumor or colonization of an epithelial lesion by a melanocytic lesion.

Although the histologic features of our cases are consistent with prior reports of melanotrichoblastoma, there is some question as to whether it represents a true variant of a pigmented trichoblastoma. There are relatively few articles in the literature that describe pigmented trichoblastomas, and of those, immunohistochemistry staining for melanocytes is uncommon. In one of the earliest descriptions of a pigmented trichoblastoma, dendritic melanocytes were present within the tumor lobules; however, the lesion was reported as a pigmented trichoblastoma and not a melanotrichoblastoma.3 It is possible that all pigmented trichoblastomas may contain some number of dendritic melanocytes, thus negating the existence of a melanotrichoblastoma as a true subtype of pigmented trichoblastomas. Additional study looking at multiple examples of pigmented trichoblastomas would be required to more definitively classify melanotrichoblastomas. It is important to appreciate that at least some cases of pigmented trichoblastomas may contain melanocytes and not to confuse the lesion as representing an example of colonization or collision tumor. A rare case of melanoma possibly arising from these dendritic melanocytes has been reported.15

Conclusion