User login

An Interdisciplinary Approach to Educating Medical Students About Dementia Assessment and Treatment Planning

The global burden of dementia is increasing at an alarming pace and is estimated to soon affect 81 million individuals worldwide.1 The World Health Organization and the Institute of Medicine have recommended greater dementia awareness and education.2,3 Despite this emphasis on dementia education, many general practitioners consider dementia care beyond their clinical domain and feel that specialists, such as geriatricians, geriatric psychiatrists, or neurologists should address dementia assessment and treatment. 4 Unfortunately, the geriatric health care workforce has been shrinking. The American Geriatrics Society estimates the need for 30,000 geriatricians by 2030, although there are only 7,300 board-certified geriatricians currently in the US.5 There is an urgent need for educating all medical trainees in dementia care regardless of their specialization interest. As the largest underwriter of graduate medical education in the US, the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) is well placed for rolling out focused dementia education. Training needs to be practical, brief, and responsive to knowledge gaps to reach the most trainees.

Despite growing emphasis on geriatric training, many medical students have limited experience with patients with dementia or their caregivers, lack exposure to interdisciplinary teams, have a poor attitude toward geriatric patients, and display specific knowledge gaps in dementia assessment and management. 6-9 Other knowledge gaps noted in medical students included assessing behavioral problems, function, safety, and caregiver burden. Medical students also had limited exposure to interdisciplinary team dementia assessment and management.

Our goal was to develop a multicomponent, experiential, brief curriculum using team-based learning to expose senior medical students to interdisciplinary assessment of dementia. The curriculum was developed with input from the interdisciplinary team to address dementia knowledge gaps while providing an opportunity to interact with caregivers. The curriculum targeted all medical students regardless of their interest in geriatrics. Particular emphasis was placed on systems-based learning and the importance of teamwork in managing complex conditions such as dementia. Students were taught that incorporating interdisciplinary input would be more effective during dementia care planning rather than developing specialized knowledge.

Methods

Our team developed a curriculum for fourthyear medical students who rotated through the VA Memory Disorders Clinic as a part of their geriatric medicine clerkship at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences in Little Rock. The Memory Disorders Clinic is a consultation practice at the Central Arkansas Veterans Healthcare System (CAVHS) where patients with memory problems are evaluated by a team consisting of a geriatric psychiatrist, a geriatrician, a social worker, and a neuropsychologist. Each specialist addresses specific areas of dementia assessment and management. The curriculum included didactics, clinical experience, and team-based learning.

Didactics

An hour-long didactic session lead by the team geriatrician provided a general overview of interdisciplinary assessment of dementia to groups of 2 to 3 students at a time. The geriatrician presented an overview of dementia types, comorbidities, medications that affect memory, details of the physical examination, and laboratory, cognitive, and behavioral assessments along with treatment plan development. Students also learned about the roles of the social worker, geriatrician, neuropsychologist, and geriatric psychiatrist in the clinic. Pictographs and pie charts highlighted the role of disciplines in assessing and managing aspects of dementia.

The social work evaluation included advance care planning, functional assessment, safety assessment (driving, guns, wandering behaviors, etc), home safety evaluation, support system, and financial evaluation. Each medical student received a binder with local resources to become familiar with the depth and breadth of agencies involved in dementia care. Each medical student learned how to administer the Zarit Burden Scale to assess caregiver burden.10 The details of the geriatrician assessment included reviewing medical comorbidities and medications contributing to dementia, a physical examination, including a focused neurologic examination, laboratory assessment, and judicious use of neuroimaging.

The neuropsychology assessment education included a battery of tests and assessments. The global screening instruments included the Modified Mini-Mental State examination (3MS), Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), and Saint Louis University Mental Status examination (SLUMS).11-13 Executive function is evaluated using the Trails Making Test A and Trails Making Test B, Controlled Oral Word Association Test, Semantic Fluency Test, and Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status test. Cognitive tests were compared and age- , education-, and race-adjusted norms for rating scales were listed if available. Each student was expected to show proficiency in ≥ 2 cognitive screening instruments (3MS, MoCA, or SLUMS). The geriatric psychiatry assessment included clinical history, onset, and course of memory problems from patient and caregiver perspectives, the Neuropsychiatric Inventory for assessing behavioral problems, employing the clinical dementia rating scale, integrating the team data, summarizing assessment, and formulating a treatment plan.14

Clinical

Students had a single clinical exposure. Students followed 1 patient and his or her caregiver through the team assessment and observed each provider’s assessment to learn interview techniques to adapt to the patient’s sensory or cognitive impairment and become familiar with different tools and devices used in the dementia clinic, such as hearing amplifiers. Each specialist provided hands-on experience. This encounter helped the students connect with caregivers and appreciate their role in patient care.

Systems learning was an important component integrated throughout the clinical experience. Examples include using video teleconferences to communicate findings among team members and electronic health records to seamlessly obtain and integrate data. Students learned how to create worksheets to graph laboratory data such as B12, thyroid-stimulating hormone, and rapid plasma regain levels. Student gained experience in using applications to retrieve neuroimaging data, results of sleep studies, and other data. Many patients had not received the results of their sleep study, and students had the responsibility to share these reports, including the number of apneic episodes. Students used the VA Computerized Patient Record System for reviewing patient records. One particularly useful tool was Joint Legacy Viewer, a remote access tool used to retrieve data on veterans from anywhere within the US. Students were also trained on medication and consult order menus in the system.

Team-Based

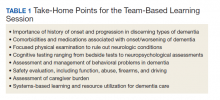

Learning The objectives of the team-based learning section were to teach students basic concepts of integrating the interdisciplinary assessment and formulating a treatment plan, to provide an opportunity to present their case in a group format, to discuss the differential diagnosis, management and treatment plan with a geriatrician in the team-based learning format, and to answer questions from other students. The instructors developed a set of prepared take-home points (Table 1). The team-based learning sessions were structured so that all take-home points were covered.

Evaluations

Evaluations were performed before and immediately after the clinical experience. In preevaluation, students reported the frequency of their participation in an interdisciplinary team assessment of any condition and specifically for dementia. In pre- and postevaluation, students rated their perception of the role of interdisciplinary team members in assessing and managing dementia, their personal abilities to assess cognition, behavioral problems, caregiver burden, and their perception of the impact of behavioral problems on dementia care. A Likert scale (poor = 1; fair = 2; good = 3; very good = 4; and excellent = 5) was employed (eApendices 1 and 2 can be found at doi:10.12788/fp.0052). The only demographic information collected was the student’s gender. Semistructured interviews were conducted to assess students’ current knowledge, experience, and needs. These interviews lasted about 20 minutes and collected information regarding the students’ knowledge about cognitive and behavioral problems in general and those occurring in dementia, their experience with screening, and any problems they encountered.

Statistical Analysis

Student baseline characteristics were assessed. Pre- and postassessments were analyzed with the McNemar test for paired data, and associations with experience were evaluated using χ2 tests. Ratings were dichotomized as very good/excellent vs poor/fair/ good because our educational goal was “very good” to “excellent” experience in dementia care and to avoid expected small cell counts. Two-sided P < .05 indicated statistical significance. Data were analyzed using SAS Enterprise Guide v5.1.

Results

One hundred fourth-year medical students participated, including 54 women. Thirtysix percent reported they had not previously attended an interdisciplinary team assessment for dementia, while 18% stated that they had attended only 1 interdisciplinary team assessment for dementia.

Before the education, students rated their dementia ability as poor. Only 2% (1 of 54), of those with 0 to 1 assessment experience rated their ability for assessing dementia with an interdisciplinary team format as very good/excellent compared with 20% (9/46) of those previously attending ≥ 2 assessments (P = .03); other ratings of ability were not associated with prior experience.

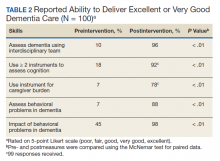

There was a significant change in the students’ self-efficacy ratings pre- to postassessment (P < .05) (Table 2). Only 10% rated their ability to assess for dementia as very good/excellent in before the intervention compared with 96% in postassessment (P < .01). Students’ perception of the impact of behavioral problems on dementia care improved significantly (45% to 98%, P < .01). Similarly, student’s perception of their ability to assess behavioral problems, caregiver burden, and cognition improved significantly from 7 to 88%; 7 to 78%, and 18 to 92%, respectively (P < .01). Students perception of the role of social worker, neuropsychologist, geriatrician, and geriatric psychiatrist also improved significantly for most measures from 81 to 98% (P = .02), 87 to 98% (P = .05), 94 to 99% (P = .06), and 88 to 100% (P = .01), respectively.

The semistructured interviews revealed that awareness of behavioral problems associated with dementia varied for different behavioral problems. Although many students showed familiarity with depression, agitation, and psychosis, they were not comfortable assessing them in a patient with dementia. These students were less aware of other behavioral problems such as disinhibition, apathy, and movement disorders. Deficits were noted in the skill of administering commonly used global cognitive screens, such as the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE).15

In semistructured interviews, only 7% of senior medical students were comfortable assessing behavioral problems associated with dementia. Most were not aware of any validated rating scale to assess neuropsychiatric symptoms. Similarly, only 7% of students were comfortable assessing caregiver burden, and most were not aware of any validated rating scale to assess caregiver burden. Only 1 in 5 students were comfortable using 2 cognitive screens to assess cognitive deficits. Many students stated that they were not routinely expected to perform common cognitive screens, such as the MMSE during their medical training except students who had expressed an interest in psychiatry and were expected to be proficient in the MMSE. Most students were making common mistakes, such as converting the 3-command task to 3 individual single commands, helping too much with serial 7s, and giving too much positive feedback throughout the test.

Discussion

Significant knowledge gaps regarding dementia were found in our study, which is in keeping with other studies in the area. Dementia knowledge deficits among medical trainees have been identified in the United Kingdom, Australia, and the US.6-9

In our study, a brief multicomponent experiential curriculum improved senior medical students’ perception and self-efficacy in diagnosing dementia. This is in keeping with other studies, such as the PAIRS Program.7 Findings from another study indicated that education for geriatric- oriented physicians should focus on experiential learning components through observation and interaction with older adults.16

A background of direct experience with older adults is associated with more positive attitudes toward older adults and increased interest in geriatric medicine.16 In our study, the exposure was brief; therefore, the results could not be compared with other long-term exposure studies. However, even with this brief intervention most students reported being comfortable with assessing caregiver burden (78%), behavioral problems of dementia (88%), and using ≥ 2 cognitive screens (92%). Comfortable in dementia assessment increased after the intervention from 10% to 96%. This finding is encouraging because brief multicomponent dementia education can be devised easily. This finding needs to be taken with caution because we did not conduct a formal skills evaluation.

A unique component of our experience was to learn medical students’ perception about the impact of neuropsychiatric symptoms on the trajectory, outcomes, and management of dementia. These symptoms included delusions, hallucinations, agitation, depression, anxiety, euphoria, apathy, disinhibition, irritability, motor disturbance, nighttime behaviors, and appetite and eating. Less than half the students thought that neuropsychiatric symptoms had a significant impact on dementia before the experience. Through didactics, systematic assessment of neuropsychiatric symptoms and interaction with caregivers, > 98% of students learned that these symptoms have a significant impact on dementia management.

This experience also emphasized the role of several disciplines in dementia assessment and management. Students’ experience positively influenced appreciation of the role of the memory clinic team. Our hope is that students will seek input from social workers, neuropsychologists, and other team members when working with patients with dementia or their caregivers. The common reason why primary care physicians focus on an exclusive medical model is the time commitment for communicating with an interdisciplinary team. Students experienced the feasibility of the interdisciplinary team involvement and how technology could be used for synchronous and asynchronous communication among team members. Medical students also were introduced to complex billing codes used when ≥ 3 disciplines assess/manage a geriatric patient.

Limitations

This study is limited by the lack of long-term follow-up evaluations, no metrics for practice changes clinical outcomes, and implementation in a single medical school. The postexperience evaluation in this study was performed immediately after the intervention. Long-term follow-up would inform whether the changes noted are durable. Because of the brief nature of our intervention, we do not believe that it would change practice in clinical care. It will be informative to follow this cohort of students to study whether their clinical approach to dementia care changes. The intervention needs to be replicated in other medical schools and in more heterogeneous groups to generalize the results of the study.

Conclusions

Senior medical students are not routinely exposed to interdisciplinary team assessments. Dementia knowledge gaps were prevalent in this cohort of senior medical students. Providing interdisciplinary geriatric educational experience improved their perception of their ability to assess for dementia and their recognition of the roles of interdisciplinary team members. Plans are in place to continue and expand the program to other complex geriatric syndromes.

Acknowledgments

Poster presented at the 2019 annual meeting of the American Geriatrics Society. Oral presentation at the same meeting as part of the select Geriatric Education Methods and Materials Swap workshop.

1. Ferri CP, Prince M, Brayne C, et al. Global prevalence of dementia: a Delphi consensus study. Lancet. 2005;366(9503):2112-2117. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67889-0

2. Janca A, Aarli JA, Prilipko L, Dua T, Saxena S, Saraceno B. WHO/WFN survey of neurological services: a worldwide perspective. J Neurol Sci. 2006;247(1):29-34. doi:10.1016/j.jns.2006.03.003

3. Wilkins KM, Blazek MC, Brooks WB, Lehmann SW, Popeo D, Wagenaar D. Six things all medical students need to know about geriatric psychiatry (and how to teach them). Acad Psychiatry. 2017;41(5):693-700. doi:10.1007/s40596-017-0691-7

4. Turner S, Iliffe S, Downs M, et al. General practitioners’ knowledge, confidence and attitudes in the diagnosis and management of dementia. Age Ageing. 2004;33(5):461- 467. doi:10.1093/ageing/afh140

5. Lester PE, Dharmarajan TS, Weinstein E. The looming geriatrician shortage: ramifications and solutions. J Aging Health. 2019:898264319879325. doi:10.1177/0898264319879325

6. Struck BD, Bernard MA, Teasdale TA; Oklahoma University Geriatric Education G. Effect of a mandatory geriatric medicine clerkship on third-year students. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(11):2007-2011. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.00473.x

7. Jefferson AL, Cantwell NG, Byerly LK, Morhardt D. Medical student education program in Alzheimer’s disease: the PAIRS Program. BMC Med Educ. 2012;12:80. doi:10.1186/1472-6920-12-80

8. Nagle BJ, Usita PM, Edland SD. United States medical students’ knowledge of Alzheimer disease. J Educ Eval Health Prof. 2013;10:4. doi:10.3352/jeehp.2013.10.4

9. Scott TL, Kugelman M, Tulloch K. How medical professional students view older people with dementia: Implications for education and practice. PLoS One. 2019;14(11):e0225329. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0225329.

10. Zarit SH, Reever KE, Bach-Peterson J. Relatives of the impaired elderly: correlates of feelings of burden. Gerontologist. 1980;20(6):649-655. doi:10.1093/geront/20.6.649

11. McDowell I, Kristjansson B, Hill GB, Hebert R. Community screening for dementia: the Mini Mental State Exam (MMSE) and Modified Mini-Mental State Exam (3MS) compared. J Clin Epidemiol. 1997;50(4):377-383. doi:10.1016/s0895-4356(97)00060-7

12. Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bedirian V, et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Ger iatr Soc. 2005;53(4):695-699. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53221.x

13. Tariq SH, Tumosa N, Chibnall JT, Perry MH, 3rd, Morley JE. Comparison of the Saint Louis University mental status examination and the Mini-Mental State Examination for detecting dementia and mild neurocognitive disorder--a pilot study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14(11):900-910. doi:10.1097/01.JGP.0000221510.33817.86

14. Cummings JL, Mega M, Gray K, Rosenberg-Thompson S, Carusi DA, Gornbein J. The Neuropsychiatric Inventory: comprehensive assessment of psychopathology in dementia. Neurology. 1994;44(12):2308-2314. doi:10.1212/wnl.44.12.2308

15. Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state.” A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189-198. doi:10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6

16. Fitzgerald JT, Wray LA, Halter JB, Williams BC, Supiano MA. Relating medical students’ knowledge, attitudes, and experience to an interest in geriatric medicine. Gerontologist. 2003;43(6):849-855. doi:10.1093/geront/43.6.849

The global burden of dementia is increasing at an alarming pace and is estimated to soon affect 81 million individuals worldwide.1 The World Health Organization and the Institute of Medicine have recommended greater dementia awareness and education.2,3 Despite this emphasis on dementia education, many general practitioners consider dementia care beyond their clinical domain and feel that specialists, such as geriatricians, geriatric psychiatrists, or neurologists should address dementia assessment and treatment. 4 Unfortunately, the geriatric health care workforce has been shrinking. The American Geriatrics Society estimates the need for 30,000 geriatricians by 2030, although there are only 7,300 board-certified geriatricians currently in the US.5 There is an urgent need for educating all medical trainees in dementia care regardless of their specialization interest. As the largest underwriter of graduate medical education in the US, the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) is well placed for rolling out focused dementia education. Training needs to be practical, brief, and responsive to knowledge gaps to reach the most trainees.

Despite growing emphasis on geriatric training, many medical students have limited experience with patients with dementia or their caregivers, lack exposure to interdisciplinary teams, have a poor attitude toward geriatric patients, and display specific knowledge gaps in dementia assessment and management. 6-9 Other knowledge gaps noted in medical students included assessing behavioral problems, function, safety, and caregiver burden. Medical students also had limited exposure to interdisciplinary team dementia assessment and management.

Our goal was to develop a multicomponent, experiential, brief curriculum using team-based learning to expose senior medical students to interdisciplinary assessment of dementia. The curriculum was developed with input from the interdisciplinary team to address dementia knowledge gaps while providing an opportunity to interact with caregivers. The curriculum targeted all medical students regardless of their interest in geriatrics. Particular emphasis was placed on systems-based learning and the importance of teamwork in managing complex conditions such as dementia. Students were taught that incorporating interdisciplinary input would be more effective during dementia care planning rather than developing specialized knowledge.

Methods

Our team developed a curriculum for fourthyear medical students who rotated through the VA Memory Disorders Clinic as a part of their geriatric medicine clerkship at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences in Little Rock. The Memory Disorders Clinic is a consultation practice at the Central Arkansas Veterans Healthcare System (CAVHS) where patients with memory problems are evaluated by a team consisting of a geriatric psychiatrist, a geriatrician, a social worker, and a neuropsychologist. Each specialist addresses specific areas of dementia assessment and management. The curriculum included didactics, clinical experience, and team-based learning.

Didactics

An hour-long didactic session lead by the team geriatrician provided a general overview of interdisciplinary assessment of dementia to groups of 2 to 3 students at a time. The geriatrician presented an overview of dementia types, comorbidities, medications that affect memory, details of the physical examination, and laboratory, cognitive, and behavioral assessments along with treatment plan development. Students also learned about the roles of the social worker, geriatrician, neuropsychologist, and geriatric psychiatrist in the clinic. Pictographs and pie charts highlighted the role of disciplines in assessing and managing aspects of dementia.

The social work evaluation included advance care planning, functional assessment, safety assessment (driving, guns, wandering behaviors, etc), home safety evaluation, support system, and financial evaluation. Each medical student received a binder with local resources to become familiar with the depth and breadth of agencies involved in dementia care. Each medical student learned how to administer the Zarit Burden Scale to assess caregiver burden.10 The details of the geriatrician assessment included reviewing medical comorbidities and medications contributing to dementia, a physical examination, including a focused neurologic examination, laboratory assessment, and judicious use of neuroimaging.

The neuropsychology assessment education included a battery of tests and assessments. The global screening instruments included the Modified Mini-Mental State examination (3MS), Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), and Saint Louis University Mental Status examination (SLUMS).11-13 Executive function is evaluated using the Trails Making Test A and Trails Making Test B, Controlled Oral Word Association Test, Semantic Fluency Test, and Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status test. Cognitive tests were compared and age- , education-, and race-adjusted norms for rating scales were listed if available. Each student was expected to show proficiency in ≥ 2 cognitive screening instruments (3MS, MoCA, or SLUMS). The geriatric psychiatry assessment included clinical history, onset, and course of memory problems from patient and caregiver perspectives, the Neuropsychiatric Inventory for assessing behavioral problems, employing the clinical dementia rating scale, integrating the team data, summarizing assessment, and formulating a treatment plan.14

Clinical

Students had a single clinical exposure. Students followed 1 patient and his or her caregiver through the team assessment and observed each provider’s assessment to learn interview techniques to adapt to the patient’s sensory or cognitive impairment and become familiar with different tools and devices used in the dementia clinic, such as hearing amplifiers. Each specialist provided hands-on experience. This encounter helped the students connect with caregivers and appreciate their role in patient care.

Systems learning was an important component integrated throughout the clinical experience. Examples include using video teleconferences to communicate findings among team members and electronic health records to seamlessly obtain and integrate data. Students learned how to create worksheets to graph laboratory data such as B12, thyroid-stimulating hormone, and rapid plasma regain levels. Student gained experience in using applications to retrieve neuroimaging data, results of sleep studies, and other data. Many patients had not received the results of their sleep study, and students had the responsibility to share these reports, including the number of apneic episodes. Students used the VA Computerized Patient Record System for reviewing patient records. One particularly useful tool was Joint Legacy Viewer, a remote access tool used to retrieve data on veterans from anywhere within the US. Students were also trained on medication and consult order menus in the system.

Team-Based

Learning The objectives of the team-based learning section were to teach students basic concepts of integrating the interdisciplinary assessment and formulating a treatment plan, to provide an opportunity to present their case in a group format, to discuss the differential diagnosis, management and treatment plan with a geriatrician in the team-based learning format, and to answer questions from other students. The instructors developed a set of prepared take-home points (Table 1). The team-based learning sessions were structured so that all take-home points were covered.

Evaluations

Evaluations were performed before and immediately after the clinical experience. In preevaluation, students reported the frequency of their participation in an interdisciplinary team assessment of any condition and specifically for dementia. In pre- and postevaluation, students rated their perception of the role of interdisciplinary team members in assessing and managing dementia, their personal abilities to assess cognition, behavioral problems, caregiver burden, and their perception of the impact of behavioral problems on dementia care. A Likert scale (poor = 1; fair = 2; good = 3; very good = 4; and excellent = 5) was employed (eApendices 1 and 2 can be found at doi:10.12788/fp.0052). The only demographic information collected was the student’s gender. Semistructured interviews were conducted to assess students’ current knowledge, experience, and needs. These interviews lasted about 20 minutes and collected information regarding the students’ knowledge about cognitive and behavioral problems in general and those occurring in dementia, their experience with screening, and any problems they encountered.

Statistical Analysis

Student baseline characteristics were assessed. Pre- and postassessments were analyzed with the McNemar test for paired data, and associations with experience were evaluated using χ2 tests. Ratings were dichotomized as very good/excellent vs poor/fair/ good because our educational goal was “very good” to “excellent” experience in dementia care and to avoid expected small cell counts. Two-sided P < .05 indicated statistical significance. Data were analyzed using SAS Enterprise Guide v5.1.

Results

One hundred fourth-year medical students participated, including 54 women. Thirtysix percent reported they had not previously attended an interdisciplinary team assessment for dementia, while 18% stated that they had attended only 1 interdisciplinary team assessment for dementia.

Before the education, students rated their dementia ability as poor. Only 2% (1 of 54), of those with 0 to 1 assessment experience rated their ability for assessing dementia with an interdisciplinary team format as very good/excellent compared with 20% (9/46) of those previously attending ≥ 2 assessments (P = .03); other ratings of ability were not associated with prior experience.

There was a significant change in the students’ self-efficacy ratings pre- to postassessment (P < .05) (Table 2). Only 10% rated their ability to assess for dementia as very good/excellent in before the intervention compared with 96% in postassessment (P < .01). Students’ perception of the impact of behavioral problems on dementia care improved significantly (45% to 98%, P < .01). Similarly, student’s perception of their ability to assess behavioral problems, caregiver burden, and cognition improved significantly from 7 to 88%; 7 to 78%, and 18 to 92%, respectively (P < .01). Students perception of the role of social worker, neuropsychologist, geriatrician, and geriatric psychiatrist also improved significantly for most measures from 81 to 98% (P = .02), 87 to 98% (P = .05), 94 to 99% (P = .06), and 88 to 100% (P = .01), respectively.

The semistructured interviews revealed that awareness of behavioral problems associated with dementia varied for different behavioral problems. Although many students showed familiarity with depression, agitation, and psychosis, they were not comfortable assessing them in a patient with dementia. These students were less aware of other behavioral problems such as disinhibition, apathy, and movement disorders. Deficits were noted in the skill of administering commonly used global cognitive screens, such as the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE).15

In semistructured interviews, only 7% of senior medical students were comfortable assessing behavioral problems associated with dementia. Most were not aware of any validated rating scale to assess neuropsychiatric symptoms. Similarly, only 7% of students were comfortable assessing caregiver burden, and most were not aware of any validated rating scale to assess caregiver burden. Only 1 in 5 students were comfortable using 2 cognitive screens to assess cognitive deficits. Many students stated that they were not routinely expected to perform common cognitive screens, such as the MMSE during their medical training except students who had expressed an interest in psychiatry and were expected to be proficient in the MMSE. Most students were making common mistakes, such as converting the 3-command task to 3 individual single commands, helping too much with serial 7s, and giving too much positive feedback throughout the test.

Discussion

Significant knowledge gaps regarding dementia were found in our study, which is in keeping with other studies in the area. Dementia knowledge deficits among medical trainees have been identified in the United Kingdom, Australia, and the US.6-9

In our study, a brief multicomponent experiential curriculum improved senior medical students’ perception and self-efficacy in diagnosing dementia. This is in keeping with other studies, such as the PAIRS Program.7 Findings from another study indicated that education for geriatric- oriented physicians should focus on experiential learning components through observation and interaction with older adults.16

A background of direct experience with older adults is associated with more positive attitudes toward older adults and increased interest in geriatric medicine.16 In our study, the exposure was brief; therefore, the results could not be compared with other long-term exposure studies. However, even with this brief intervention most students reported being comfortable with assessing caregiver burden (78%), behavioral problems of dementia (88%), and using ≥ 2 cognitive screens (92%). Comfortable in dementia assessment increased after the intervention from 10% to 96%. This finding is encouraging because brief multicomponent dementia education can be devised easily. This finding needs to be taken with caution because we did not conduct a formal skills evaluation.

A unique component of our experience was to learn medical students’ perception about the impact of neuropsychiatric symptoms on the trajectory, outcomes, and management of dementia. These symptoms included delusions, hallucinations, agitation, depression, anxiety, euphoria, apathy, disinhibition, irritability, motor disturbance, nighttime behaviors, and appetite and eating. Less than half the students thought that neuropsychiatric symptoms had a significant impact on dementia before the experience. Through didactics, systematic assessment of neuropsychiatric symptoms and interaction with caregivers, > 98% of students learned that these symptoms have a significant impact on dementia management.

This experience also emphasized the role of several disciplines in dementia assessment and management. Students’ experience positively influenced appreciation of the role of the memory clinic team. Our hope is that students will seek input from social workers, neuropsychologists, and other team members when working with patients with dementia or their caregivers. The common reason why primary care physicians focus on an exclusive medical model is the time commitment for communicating with an interdisciplinary team. Students experienced the feasibility of the interdisciplinary team involvement and how technology could be used for synchronous and asynchronous communication among team members. Medical students also were introduced to complex billing codes used when ≥ 3 disciplines assess/manage a geriatric patient.

Limitations

This study is limited by the lack of long-term follow-up evaluations, no metrics for practice changes clinical outcomes, and implementation in a single medical school. The postexperience evaluation in this study was performed immediately after the intervention. Long-term follow-up would inform whether the changes noted are durable. Because of the brief nature of our intervention, we do not believe that it would change practice in clinical care. It will be informative to follow this cohort of students to study whether their clinical approach to dementia care changes. The intervention needs to be replicated in other medical schools and in more heterogeneous groups to generalize the results of the study.

Conclusions

Senior medical students are not routinely exposed to interdisciplinary team assessments. Dementia knowledge gaps were prevalent in this cohort of senior medical students. Providing interdisciplinary geriatric educational experience improved their perception of their ability to assess for dementia and their recognition of the roles of interdisciplinary team members. Plans are in place to continue and expand the program to other complex geriatric syndromes.

Acknowledgments

Poster presented at the 2019 annual meeting of the American Geriatrics Society. Oral presentation at the same meeting as part of the select Geriatric Education Methods and Materials Swap workshop.

The global burden of dementia is increasing at an alarming pace and is estimated to soon affect 81 million individuals worldwide.1 The World Health Organization and the Institute of Medicine have recommended greater dementia awareness and education.2,3 Despite this emphasis on dementia education, many general practitioners consider dementia care beyond their clinical domain and feel that specialists, such as geriatricians, geriatric psychiatrists, or neurologists should address dementia assessment and treatment. 4 Unfortunately, the geriatric health care workforce has been shrinking. The American Geriatrics Society estimates the need for 30,000 geriatricians by 2030, although there are only 7,300 board-certified geriatricians currently in the US.5 There is an urgent need for educating all medical trainees in dementia care regardless of their specialization interest. As the largest underwriter of graduate medical education in the US, the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) is well placed for rolling out focused dementia education. Training needs to be practical, brief, and responsive to knowledge gaps to reach the most trainees.

Despite growing emphasis on geriatric training, many medical students have limited experience with patients with dementia or their caregivers, lack exposure to interdisciplinary teams, have a poor attitude toward geriatric patients, and display specific knowledge gaps in dementia assessment and management. 6-9 Other knowledge gaps noted in medical students included assessing behavioral problems, function, safety, and caregiver burden. Medical students also had limited exposure to interdisciplinary team dementia assessment and management.

Our goal was to develop a multicomponent, experiential, brief curriculum using team-based learning to expose senior medical students to interdisciplinary assessment of dementia. The curriculum was developed with input from the interdisciplinary team to address dementia knowledge gaps while providing an opportunity to interact with caregivers. The curriculum targeted all medical students regardless of their interest in geriatrics. Particular emphasis was placed on systems-based learning and the importance of teamwork in managing complex conditions such as dementia. Students were taught that incorporating interdisciplinary input would be more effective during dementia care planning rather than developing specialized knowledge.

Methods

Our team developed a curriculum for fourthyear medical students who rotated through the VA Memory Disorders Clinic as a part of their geriatric medicine clerkship at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences in Little Rock. The Memory Disorders Clinic is a consultation practice at the Central Arkansas Veterans Healthcare System (CAVHS) where patients with memory problems are evaluated by a team consisting of a geriatric psychiatrist, a geriatrician, a social worker, and a neuropsychologist. Each specialist addresses specific areas of dementia assessment and management. The curriculum included didactics, clinical experience, and team-based learning.

Didactics

An hour-long didactic session lead by the team geriatrician provided a general overview of interdisciplinary assessment of dementia to groups of 2 to 3 students at a time. The geriatrician presented an overview of dementia types, comorbidities, medications that affect memory, details of the physical examination, and laboratory, cognitive, and behavioral assessments along with treatment plan development. Students also learned about the roles of the social worker, geriatrician, neuropsychologist, and geriatric psychiatrist in the clinic. Pictographs and pie charts highlighted the role of disciplines in assessing and managing aspects of dementia.

The social work evaluation included advance care planning, functional assessment, safety assessment (driving, guns, wandering behaviors, etc), home safety evaluation, support system, and financial evaluation. Each medical student received a binder with local resources to become familiar with the depth and breadth of agencies involved in dementia care. Each medical student learned how to administer the Zarit Burden Scale to assess caregiver burden.10 The details of the geriatrician assessment included reviewing medical comorbidities and medications contributing to dementia, a physical examination, including a focused neurologic examination, laboratory assessment, and judicious use of neuroimaging.

The neuropsychology assessment education included a battery of tests and assessments. The global screening instruments included the Modified Mini-Mental State examination (3MS), Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), and Saint Louis University Mental Status examination (SLUMS).11-13 Executive function is evaluated using the Trails Making Test A and Trails Making Test B, Controlled Oral Word Association Test, Semantic Fluency Test, and Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status test. Cognitive tests were compared and age- , education-, and race-adjusted norms for rating scales were listed if available. Each student was expected to show proficiency in ≥ 2 cognitive screening instruments (3MS, MoCA, or SLUMS). The geriatric psychiatry assessment included clinical history, onset, and course of memory problems from patient and caregiver perspectives, the Neuropsychiatric Inventory for assessing behavioral problems, employing the clinical dementia rating scale, integrating the team data, summarizing assessment, and formulating a treatment plan.14

Clinical

Students had a single clinical exposure. Students followed 1 patient and his or her caregiver through the team assessment and observed each provider’s assessment to learn interview techniques to adapt to the patient’s sensory or cognitive impairment and become familiar with different tools and devices used in the dementia clinic, such as hearing amplifiers. Each specialist provided hands-on experience. This encounter helped the students connect with caregivers and appreciate their role in patient care.

Systems learning was an important component integrated throughout the clinical experience. Examples include using video teleconferences to communicate findings among team members and electronic health records to seamlessly obtain and integrate data. Students learned how to create worksheets to graph laboratory data such as B12, thyroid-stimulating hormone, and rapid plasma regain levels. Student gained experience in using applications to retrieve neuroimaging data, results of sleep studies, and other data. Many patients had not received the results of their sleep study, and students had the responsibility to share these reports, including the number of apneic episodes. Students used the VA Computerized Patient Record System for reviewing patient records. One particularly useful tool was Joint Legacy Viewer, a remote access tool used to retrieve data on veterans from anywhere within the US. Students were also trained on medication and consult order menus in the system.

Team-Based

Learning The objectives of the team-based learning section were to teach students basic concepts of integrating the interdisciplinary assessment and formulating a treatment plan, to provide an opportunity to present their case in a group format, to discuss the differential diagnosis, management and treatment plan with a geriatrician in the team-based learning format, and to answer questions from other students. The instructors developed a set of prepared take-home points (Table 1). The team-based learning sessions were structured so that all take-home points were covered.

Evaluations

Evaluations were performed before and immediately after the clinical experience. In preevaluation, students reported the frequency of their participation in an interdisciplinary team assessment of any condition and specifically for dementia. In pre- and postevaluation, students rated their perception of the role of interdisciplinary team members in assessing and managing dementia, their personal abilities to assess cognition, behavioral problems, caregiver burden, and their perception of the impact of behavioral problems on dementia care. A Likert scale (poor = 1; fair = 2; good = 3; very good = 4; and excellent = 5) was employed (eApendices 1 and 2 can be found at doi:10.12788/fp.0052). The only demographic information collected was the student’s gender. Semistructured interviews were conducted to assess students’ current knowledge, experience, and needs. These interviews lasted about 20 minutes and collected information regarding the students’ knowledge about cognitive and behavioral problems in general and those occurring in dementia, their experience with screening, and any problems they encountered.

Statistical Analysis

Student baseline characteristics were assessed. Pre- and postassessments were analyzed with the McNemar test for paired data, and associations with experience were evaluated using χ2 tests. Ratings were dichotomized as very good/excellent vs poor/fair/ good because our educational goal was “very good” to “excellent” experience in dementia care and to avoid expected small cell counts. Two-sided P < .05 indicated statistical significance. Data were analyzed using SAS Enterprise Guide v5.1.

Results

One hundred fourth-year medical students participated, including 54 women. Thirtysix percent reported they had not previously attended an interdisciplinary team assessment for dementia, while 18% stated that they had attended only 1 interdisciplinary team assessment for dementia.

Before the education, students rated their dementia ability as poor. Only 2% (1 of 54), of those with 0 to 1 assessment experience rated their ability for assessing dementia with an interdisciplinary team format as very good/excellent compared with 20% (9/46) of those previously attending ≥ 2 assessments (P = .03); other ratings of ability were not associated with prior experience.

There was a significant change in the students’ self-efficacy ratings pre- to postassessment (P < .05) (Table 2). Only 10% rated their ability to assess for dementia as very good/excellent in before the intervention compared with 96% in postassessment (P < .01). Students’ perception of the impact of behavioral problems on dementia care improved significantly (45% to 98%, P < .01). Similarly, student’s perception of their ability to assess behavioral problems, caregiver burden, and cognition improved significantly from 7 to 88%; 7 to 78%, and 18 to 92%, respectively (P < .01). Students perception of the role of social worker, neuropsychologist, geriatrician, and geriatric psychiatrist also improved significantly for most measures from 81 to 98% (P = .02), 87 to 98% (P = .05), 94 to 99% (P = .06), and 88 to 100% (P = .01), respectively.

The semistructured interviews revealed that awareness of behavioral problems associated with dementia varied for different behavioral problems. Although many students showed familiarity with depression, agitation, and psychosis, they were not comfortable assessing them in a patient with dementia. These students were less aware of other behavioral problems such as disinhibition, apathy, and movement disorders. Deficits were noted in the skill of administering commonly used global cognitive screens, such as the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE).15

In semistructured interviews, only 7% of senior medical students were comfortable assessing behavioral problems associated with dementia. Most were not aware of any validated rating scale to assess neuropsychiatric symptoms. Similarly, only 7% of students were comfortable assessing caregiver burden, and most were not aware of any validated rating scale to assess caregiver burden. Only 1 in 5 students were comfortable using 2 cognitive screens to assess cognitive deficits. Many students stated that they were not routinely expected to perform common cognitive screens, such as the MMSE during their medical training except students who had expressed an interest in psychiatry and were expected to be proficient in the MMSE. Most students were making common mistakes, such as converting the 3-command task to 3 individual single commands, helping too much with serial 7s, and giving too much positive feedback throughout the test.

Discussion

Significant knowledge gaps regarding dementia were found in our study, which is in keeping with other studies in the area. Dementia knowledge deficits among medical trainees have been identified in the United Kingdom, Australia, and the US.6-9

In our study, a brief multicomponent experiential curriculum improved senior medical students’ perception and self-efficacy in diagnosing dementia. This is in keeping with other studies, such as the PAIRS Program.7 Findings from another study indicated that education for geriatric- oriented physicians should focus on experiential learning components through observation and interaction with older adults.16

A background of direct experience with older adults is associated with more positive attitudes toward older adults and increased interest in geriatric medicine.16 In our study, the exposure was brief; therefore, the results could not be compared with other long-term exposure studies. However, even with this brief intervention most students reported being comfortable with assessing caregiver burden (78%), behavioral problems of dementia (88%), and using ≥ 2 cognitive screens (92%). Comfortable in dementia assessment increased after the intervention from 10% to 96%. This finding is encouraging because brief multicomponent dementia education can be devised easily. This finding needs to be taken with caution because we did not conduct a formal skills evaluation.

A unique component of our experience was to learn medical students’ perception about the impact of neuropsychiatric symptoms on the trajectory, outcomes, and management of dementia. These symptoms included delusions, hallucinations, agitation, depression, anxiety, euphoria, apathy, disinhibition, irritability, motor disturbance, nighttime behaviors, and appetite and eating. Less than half the students thought that neuropsychiatric symptoms had a significant impact on dementia before the experience. Through didactics, systematic assessment of neuropsychiatric symptoms and interaction with caregivers, > 98% of students learned that these symptoms have a significant impact on dementia management.

This experience also emphasized the role of several disciplines in dementia assessment and management. Students’ experience positively influenced appreciation of the role of the memory clinic team. Our hope is that students will seek input from social workers, neuropsychologists, and other team members when working with patients with dementia or their caregivers. The common reason why primary care physicians focus on an exclusive medical model is the time commitment for communicating with an interdisciplinary team. Students experienced the feasibility of the interdisciplinary team involvement and how technology could be used for synchronous and asynchronous communication among team members. Medical students also were introduced to complex billing codes used when ≥ 3 disciplines assess/manage a geriatric patient.

Limitations

This study is limited by the lack of long-term follow-up evaluations, no metrics for practice changes clinical outcomes, and implementation in a single medical school. The postexperience evaluation in this study was performed immediately after the intervention. Long-term follow-up would inform whether the changes noted are durable. Because of the brief nature of our intervention, we do not believe that it would change practice in clinical care. It will be informative to follow this cohort of students to study whether their clinical approach to dementia care changes. The intervention needs to be replicated in other medical schools and in more heterogeneous groups to generalize the results of the study.

Conclusions

Senior medical students are not routinely exposed to interdisciplinary team assessments. Dementia knowledge gaps were prevalent in this cohort of senior medical students. Providing interdisciplinary geriatric educational experience improved their perception of their ability to assess for dementia and their recognition of the roles of interdisciplinary team members. Plans are in place to continue and expand the program to other complex geriatric syndromes.

Acknowledgments

Poster presented at the 2019 annual meeting of the American Geriatrics Society. Oral presentation at the same meeting as part of the select Geriatric Education Methods and Materials Swap workshop.

1. Ferri CP, Prince M, Brayne C, et al. Global prevalence of dementia: a Delphi consensus study. Lancet. 2005;366(9503):2112-2117. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67889-0

2. Janca A, Aarli JA, Prilipko L, Dua T, Saxena S, Saraceno B. WHO/WFN survey of neurological services: a worldwide perspective. J Neurol Sci. 2006;247(1):29-34. doi:10.1016/j.jns.2006.03.003

3. Wilkins KM, Blazek MC, Brooks WB, Lehmann SW, Popeo D, Wagenaar D. Six things all medical students need to know about geriatric psychiatry (and how to teach them). Acad Psychiatry. 2017;41(5):693-700. doi:10.1007/s40596-017-0691-7

4. Turner S, Iliffe S, Downs M, et al. General practitioners’ knowledge, confidence and attitudes in the diagnosis and management of dementia. Age Ageing. 2004;33(5):461- 467. doi:10.1093/ageing/afh140

5. Lester PE, Dharmarajan TS, Weinstein E. The looming geriatrician shortage: ramifications and solutions. J Aging Health. 2019:898264319879325. doi:10.1177/0898264319879325

6. Struck BD, Bernard MA, Teasdale TA; Oklahoma University Geriatric Education G. Effect of a mandatory geriatric medicine clerkship on third-year students. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(11):2007-2011. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.00473.x

7. Jefferson AL, Cantwell NG, Byerly LK, Morhardt D. Medical student education program in Alzheimer’s disease: the PAIRS Program. BMC Med Educ. 2012;12:80. doi:10.1186/1472-6920-12-80

8. Nagle BJ, Usita PM, Edland SD. United States medical students’ knowledge of Alzheimer disease. J Educ Eval Health Prof. 2013;10:4. doi:10.3352/jeehp.2013.10.4

9. Scott TL, Kugelman M, Tulloch K. How medical professional students view older people with dementia: Implications for education and practice. PLoS One. 2019;14(11):e0225329. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0225329.

10. Zarit SH, Reever KE, Bach-Peterson J. Relatives of the impaired elderly: correlates of feelings of burden. Gerontologist. 1980;20(6):649-655. doi:10.1093/geront/20.6.649

11. McDowell I, Kristjansson B, Hill GB, Hebert R. Community screening for dementia: the Mini Mental State Exam (MMSE) and Modified Mini-Mental State Exam (3MS) compared. J Clin Epidemiol. 1997;50(4):377-383. doi:10.1016/s0895-4356(97)00060-7

12. Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bedirian V, et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Ger iatr Soc. 2005;53(4):695-699. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53221.x

13. Tariq SH, Tumosa N, Chibnall JT, Perry MH, 3rd, Morley JE. Comparison of the Saint Louis University mental status examination and the Mini-Mental State Examination for detecting dementia and mild neurocognitive disorder--a pilot study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14(11):900-910. doi:10.1097/01.JGP.0000221510.33817.86

14. Cummings JL, Mega M, Gray K, Rosenberg-Thompson S, Carusi DA, Gornbein J. The Neuropsychiatric Inventory: comprehensive assessment of psychopathology in dementia. Neurology. 1994;44(12):2308-2314. doi:10.1212/wnl.44.12.2308

15. Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state.” A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189-198. doi:10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6

16. Fitzgerald JT, Wray LA, Halter JB, Williams BC, Supiano MA. Relating medical students’ knowledge, attitudes, and experience to an interest in geriatric medicine. Gerontologist. 2003;43(6):849-855. doi:10.1093/geront/43.6.849

1. Ferri CP, Prince M, Brayne C, et al. Global prevalence of dementia: a Delphi consensus study. Lancet. 2005;366(9503):2112-2117. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67889-0

2. Janca A, Aarli JA, Prilipko L, Dua T, Saxena S, Saraceno B. WHO/WFN survey of neurological services: a worldwide perspective. J Neurol Sci. 2006;247(1):29-34. doi:10.1016/j.jns.2006.03.003

3. Wilkins KM, Blazek MC, Brooks WB, Lehmann SW, Popeo D, Wagenaar D. Six things all medical students need to know about geriatric psychiatry (and how to teach them). Acad Psychiatry. 2017;41(5):693-700. doi:10.1007/s40596-017-0691-7

4. Turner S, Iliffe S, Downs M, et al. General practitioners’ knowledge, confidence and attitudes in the diagnosis and management of dementia. Age Ageing. 2004;33(5):461- 467. doi:10.1093/ageing/afh140

5. Lester PE, Dharmarajan TS, Weinstein E. The looming geriatrician shortage: ramifications and solutions. J Aging Health. 2019:898264319879325. doi:10.1177/0898264319879325

6. Struck BD, Bernard MA, Teasdale TA; Oklahoma University Geriatric Education G. Effect of a mandatory geriatric medicine clerkship on third-year students. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(11):2007-2011. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.00473.x

7. Jefferson AL, Cantwell NG, Byerly LK, Morhardt D. Medical student education program in Alzheimer’s disease: the PAIRS Program. BMC Med Educ. 2012;12:80. doi:10.1186/1472-6920-12-80

8. Nagle BJ, Usita PM, Edland SD. United States medical students’ knowledge of Alzheimer disease. J Educ Eval Health Prof. 2013;10:4. doi:10.3352/jeehp.2013.10.4

9. Scott TL, Kugelman M, Tulloch K. How medical professional students view older people with dementia: Implications for education and practice. PLoS One. 2019;14(11):e0225329. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0225329.

10. Zarit SH, Reever KE, Bach-Peterson J. Relatives of the impaired elderly: correlates of feelings of burden. Gerontologist. 1980;20(6):649-655. doi:10.1093/geront/20.6.649

11. McDowell I, Kristjansson B, Hill GB, Hebert R. Community screening for dementia: the Mini Mental State Exam (MMSE) and Modified Mini-Mental State Exam (3MS) compared. J Clin Epidemiol. 1997;50(4):377-383. doi:10.1016/s0895-4356(97)00060-7

12. Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bedirian V, et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Ger iatr Soc. 2005;53(4):695-699. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53221.x

13. Tariq SH, Tumosa N, Chibnall JT, Perry MH, 3rd, Morley JE. Comparison of the Saint Louis University mental status examination and the Mini-Mental State Examination for detecting dementia and mild neurocognitive disorder--a pilot study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14(11):900-910. doi:10.1097/01.JGP.0000221510.33817.86

14. Cummings JL, Mega M, Gray K, Rosenberg-Thompson S, Carusi DA, Gornbein J. The Neuropsychiatric Inventory: comprehensive assessment of psychopathology in dementia. Neurology. 1994;44(12):2308-2314. doi:10.1212/wnl.44.12.2308

15. Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state.” A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189-198. doi:10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6

16. Fitzgerald JT, Wray LA, Halter JB, Williams BC, Supiano MA. Relating medical students’ knowledge, attitudes, and experience to an interest in geriatric medicine. Gerontologist. 2003;43(6):849-855. doi:10.1093/geront/43.6.849

Development and Implementation of a Geriatric Walking Clinic

Inactivity and increased sedentary time are major public health problems, particularly among older adults.1-3 Inactivity increases with age and produces deleterious effects on physical health, mental health, and quality of life and leads to increased health care costs.4 The high prevalence of a sedentary lifestyle among older veterans may be due to multiple factors, including misconceptions about the health benefits of exercise, lack of motivation, or associating exercise with discomfort or pain. Older veterans living in rural areas are at high risk because they are more sedentary than are urban-dwelling veterans.5 Of veterans aged ≥ 65 years who use health care services in VISN 16, 59% live in rural or highly rural areas.

Given the large number of older veterans and their at-risk status, addressing inactivity among this population is critical. Until recently, few programs existed within the VHA that addressed this need. Despite strong evidence that physical activity helps maintain functional independence and avoids institutionalization of frail elderly veterans, the VHA had no established procedures or guidelines for assessment and counseling.

To address this void, a Geriatric Walking Clinic (GWC) was established at the Central Arkansas Veterans Healthcare System (CAVHS) in March 2013. The GWC developed a patient-centric, home-based program that implements a comprehensive approach to assess, educate, motivate, and activate older veterans to commit to, engage in, and adhere to, a long-term program of regular physical activity primarily in the form of walking. The program uses proven strategies, such as motivational counseling, follow-up phone calls from a nurse, and self-monitoring using pedometers.6-8 Funding for the GWC project was provided by the VHA Office of Geriatrics and Extended Care as part of its Transition to the 21st Century (T21) initiative and by the VHA Office of Rural Health.

Methods

Quality improvement (QI) principles were used to develop the program, which received a nonresearch determination status from the local institutional review board. The GWC is staffed by a registered nurse, health technician, and physician. Both the nurse and the health technician were trained on the use of various assessments. Several tactics were developed to promote patient recruitment to the GWC, including systemwide in-services, an easy-to-use consultation request within the electronic medical record, patient and provider brochures, and informational booths and kiosks. Collaborations were developed with various clinical services to promote referrals. Several other services, such as Primary Care, Geriatrics, the Move! Weight Management Program, Cardiology (including Congestive Heart Failure), Hematology/Oncology, and Mental Health referred patients to the GWC.

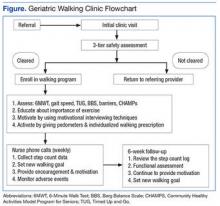

The GWC targets sedentary, community-dwelling veterans aged ≥ 60 years who are able to ambulate in their home without an assistive device, are willing to walk for exercise, and are willing to receive phone calls. All-comers are included in the program. Although most of these veterans have multiple chronic medical problems, only those with absolute contraindications to exercise per the American College of Sports Medicine guidelines and those with any medical condition that is likely to compromise their ability to safely participate in the walking program are excluded (Figure).

First Visit

At the first visit, veterans receive a brief education about GWC, highlighting its potential health benefits. If veterans want to join, they are evaluated using a 3-tier screening assessment to determine the safety of starting a new walking regimen. Veterans who fail the 3-tier safety screening are referred to their primary care physician (PCP) for further assessment (eg, cardiac stress testing) to better define eligibility status. Veterans who pass the screen complete brief tests of physical performance, including gait speed, 6-Minute Walk Test (6MWT), Timed Up and Go test, and Berg Balance Scale.9-12 Participants also complete short surveys that provide useful information about their social support, barriers to exercise, response to physical activity, and usual activity level as measured by Community Healthy Activities Model Program for Seniors.13,14 This information is used to help develop an individualized walking prescription.

After completing the baseline assessments, the GWC staff members help the veteran set realistic goals, using motivational counseling techniques. The veteran receives a walking prescription to walk indoors or outdoors, based on current physical condition, self-identified goals, perceived barriers, and strength of support system; educational material about safe walking; a log for recording daily step count; information on follow-up calls; and an invitation to return for follow-up visits. The veteran also receives a pedometer and is instructed to continue his or her usual routine for the first week. The average daily step count is recorded as the baseline. The veteran is instructed to start the walking program after the baseline week with goals tailored to the personal activity level. For example: Some patients are asked to simply add an extra minute to their walking, whereas others savvy with pedometer numbers are asked to increase their step count.

Follow-up

Veterans are followed closely between their clinic appointments via phone calls from a nurse who provides encouragement and helps set new goals. The nurse collects the step count data to determine progress and set new walking goals. Those unable to adhere to their walking prescription are reassessed for their barriers. The nurse also helps participants identify ways to overcome individual challenges. The PCP is consulted when barriers include medical problems, such as pain or poor blood sugar control.

At the 6-week follow-up visit, the health care provider reviews the pedometer log and repeats all outcome assessments, including the physical performance testing and the participant surveys. Veterans receive feedback from these outcome assessments. To assess participant satisfaction, CAVHS GRECC developed a satisfaction questionnaire, which was given to participants.

Results

A total of 249 older veterans participated in the GWC program. The mean age was 67 (±6) years; 92% were male, 60% were white, and 39% were African American. Most participants lived in a rural location (60%) and were obese (69%); consistent with national standards, obesity was defined as a body mass index (BMI) ≥ 30 kg/m2. Several barriers to exercise were endorsed by the veterans. Most commonly endorsed barriers included bad weather, lack of motivation, feeling tired, and fear of pain. Most participants (93%) were actively engaged via regular phone follow-ups visits; 121 (49%) participants returned to the clinic for the 6-week reassessment. Repeat performance testing at the 6-week visit showed a clinically significant average 14% improvement in the 6MWT, 6% improvement in the Timed Up and Go test, and a 27% improvement in gait speed. Of those veterans who were obese, 64% lost weight. On entry into the program, 32 participants (13%) had poorly controlled diabetes mellitus (DM), defined as hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) ≥ 8. Among this group, HbA1c improved by an average of 1.5% by the 6-week visit. The GWC program may have contributed to the improved glycemic control as a generally accepted frequency of monitoring HbA1c is at least 3 months.

At the 6-week clinic visit, 94% of those surveyed completed a program evaluation. The GWC scored high on satisfaction; over 80% strongly agreed that they were satisfied with the GWC program as a whole, 80% strongly agreed that the program increased their awareness about need for exercise, 82% strongly agreed that the clinician’s advice was applicable to them, and 77% strongly agreed that the program improved their motivation to walk regularly (Table 1).

Program Economics

An analysis of the clinic costs and benefits was performed to determine whether costs could potentially be offset by the savings realized from improved health outcomes of participating veterans. For this simplified analysis, costs of maintaining the GWC were set equal to the costs of the full-time equivalent employee hours, equipment, and educational materials. Based on the authors’ experience, they projected that for each 1,000 older veterans enrolled in the GWC, there is a requirement for 0.5 medical support assistant (GS-6 pay scale), 1.0 registered nurse grade 2 (RN), 1.0 health science specialist (GS-7), and 0.25 physician. At the host facility, the annual personnel costs are estimated at $205,149. The total annual cost of the GWC, including the equipment and educational materials, is estimated at $240,149.

Although full financial return on investment has yet to be determined, the authors estimated potential cost savings resulting if patients enrolled in a GWC achieved and maintained the types of improvements observed in the first cohort of patients. These estimates were based on identified improvements in 3 patient outcome measures cited in the medical literature that are associated with reductions in subsequent health care costs. These measures include gait speed, weight loss, and HbA1c. It is estimated that the cost savings associated with improvement of gait speed by 0.1 m/s (a clinically relevant change) is $1,200 annually.15

On average, patients enrolled in the GWC program improved their gait speed by 0.22 m/s. Cost savings related to gait speed improvement for 1,000 participants could reach $1,200,000. Conservative estimates of cost savings per 1% reduction of HbA1c is $950/year.16 Among those with poorly controlled DM (ie, HbA1c of ≥ 8), average HbA1c declined by 1.5%. Provided that 13% of the patients have poorly controlled DM, the total cost saving for 1,000 participants could be $209,950 annually.

It also is estimated that a 1% weight loss in obese patients is associated with a $256 decrease in subsequent total health care costs.17 In the GWC, the obese participants lost an average of 1.3% of their baseline weight. Assuming that about 60% of all older veterans participating in the clinic program are obese, annual cost savings per 1,000 participants related to weight loss is estimated to be $199,680. After accounting for the costs of operating the clinic, the total cost savings for a GWC with 1,000 enrolled older veterans is estimated to be as much as $1.4 million annually. Such a favorable cost assessment suggests that the program should be evaluated for widespread dissemination throughout the entire VHA system. Other potential benefits associated with GWC participation, such as improved quality of life and greater functional independence, may be of even greater importance to veterans.

Limitations

Results of this QI project need to be considered in light of its limitations. One of the most important limitations is the design of the project. Since this was a clinical initiative and not a research study, there was no control group or randomization. There were also limitations on data availability. HbA1c tests were not ordered as part of this QI project. Instead, baseline HbA1c was set equal to the most recent of any value obtained clinically within 2 months before the participant’s GWC enrollment; the 6-week follow-up value was set to any HbA1c obtained within 2 months after the 6-week visit. It is also recognized that factors other than the veterans’ participation in the GWC (eg, alterations in their DM medication regimen) may have contributed to the changes noted in some participant’s HbA1c. Although not necessarily a limitation, 140 of the 247 participants (57%) were enrolled in MOVE! as well. MOVE! is a widely popular weight management program in the VA focusing on diet control.18 The authors, however, have no information about the veterans’ adherence to MOVE!

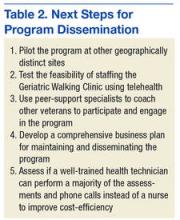

Five immediate next steps to disseminate the program have been identified (Table 2).

Conclusion

The GWC was successfully developed and implemented as a QI project at CAVHS and was met with much satisfaction by older veterans. Participants experienced clinically significant improvements in physical performance and other health indicators, suggesting that these benefits could potentially offset clinic costs.

1. Jefferis BJ, Sartini C, Ash S, et al. Trajectories of objectively measured physical activity in free-living older men. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2015;47(2):343-349.

2. Sun F, Norman IJ, While AE. Physical activity in older people: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:449.

3. Troiano RP, Berrigan D, Dodd KW, Mâsse LC, Tilert T, McDowell M. Physical activity in the United States measured by accelerometer. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2008;40(1):181-188.

4. Vogel T, Brechat PH, Lepretre PM, Kaltenbach G, Berthel M, Lonsdorfer J. Health benefits of physical activity in older patients: a review. Int J Clin Pract. 2009;63(2):303-320.

5. Patterson PD, Moore CG, Probst JC, Shinogle JA. Obesity and physical inactivity in rural America. J Rural Health. 2004;20(2):151-159.

6. Dubbert PM, Cooper KM, Kirchner KA, Meydrech EF, Bilbrew D. Effects of nurse counseling on walking for exercise in elderly primary care patients. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2002;57(11):M733-M740.

7. Dubbert PM, Morey MC, Kirchner KA, Meydrech EF, Grothe K. Counseling for home-based walking and strength exercise in older primary care patients. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(9):979-986.

8. Newton RL Jr, HH M, Dubbert PM, et al. Pedometer determined physical activity tracks in African American adults: the Jackson Heart Study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2012;9:44.

9. Bohannon RW. Comfortable and maximum walking speed of adults aged 20-79 years: reference values and determinants. Age Ageing. 1997;26(1):15-19.

10. Guyatt GH, Sullivan MJ, Thompson PJ, et al. The 6-minute walk: a new measure of exercise capacity in patients with chronic heart failure. Can Med Assoc J. 1985;132(8):919-923.

11. Hiengkaew V, Jitaree K, Chaiyawat P. Minimal detectable changes of the Berg Balance Scale, Fugl-Meyer Assessment Scale, Timed “Up & Go” Test, gait speeds, and 2-minute walk test in individuals with chronic stroke with different degrees of ankle plantarflexor tone. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2012;93(7):1201-1208.

12. Muir SW, Berg K, Chesworth B, Speechley M. Use of the Berg Balance Scale for predicting multiple falls in community-dwelling elderly people: a prospective study. Phys Ther. 2008;88(4):449-459.

13. Clark DO, Nothwehr F. Exercise self-efficacy and its correlates among socioeconomically disadvantaged older adults. Health Educ Behav. 1999;26(4):535-546.

14. Stewart AL, Verboncoeur CJ, McLellan BY, et al. Physical activity outcomes of CHAMPS II: a physical activity promotion program for older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56(8):M465-M470.

15. Purser JL, Weinberger M, Cohen HJ, et al. Walking speed predicts health status and hospital costs for frail elderly male Veterans. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2005;42(4):535-546.

16. Wagner EH, Sandhu N, Newton KM, McCulloch DK, Ramsey SD, Grothaus LC. Effect of improved glycemic control on health care costs and utilization. JAMA. 2001;285(2):182-189.

17. Yu AP, Wu EQ, Birnbaum HG, et al. Short-term economic impact of body weight change among patients with type 2 diabetes treated with antidiabetic agents: analysis using claims, laboratory, and medical record data. Curr Med Res Opin. 2007;23(9):2157-2169.

18. Romanova M, Liang LJ, Deng ML, Li Z, Heber D. Effectiveness of the MOVE! multidisciplinary weight loss program for veterans in Los Angeles. Prev Chronic Dis. 2013;10:E112.

Inactivity and increased sedentary time are major public health problems, particularly among older adults.1-3 Inactivity increases with age and produces deleterious effects on physical health, mental health, and quality of life and leads to increased health care costs.4 The high prevalence of a sedentary lifestyle among older veterans may be due to multiple factors, including misconceptions about the health benefits of exercise, lack of motivation, or associating exercise with discomfort or pain. Older veterans living in rural areas are at high risk because they are more sedentary than are urban-dwelling veterans.5 Of veterans aged ≥ 65 years who use health care services in VISN 16, 59% live in rural or highly rural areas.

Given the large number of older veterans and their at-risk status, addressing inactivity among this population is critical. Until recently, few programs existed within the VHA that addressed this need. Despite strong evidence that physical activity helps maintain functional independence and avoids institutionalization of frail elderly veterans, the VHA had no established procedures or guidelines for assessment and counseling.

To address this void, a Geriatric Walking Clinic (GWC) was established at the Central Arkansas Veterans Healthcare System (CAVHS) in March 2013. The GWC developed a patient-centric, home-based program that implements a comprehensive approach to assess, educate, motivate, and activate older veterans to commit to, engage in, and adhere to, a long-term program of regular physical activity primarily in the form of walking. The program uses proven strategies, such as motivational counseling, follow-up phone calls from a nurse, and self-monitoring using pedometers.6-8 Funding for the GWC project was provided by the VHA Office of Geriatrics and Extended Care as part of its Transition to the 21st Century (T21) initiative and by the VHA Office of Rural Health.

Methods

Quality improvement (QI) principles were used to develop the program, which received a nonresearch determination status from the local institutional review board. The GWC is staffed by a registered nurse, health technician, and physician. Both the nurse and the health technician were trained on the use of various assessments. Several tactics were developed to promote patient recruitment to the GWC, including systemwide in-services, an easy-to-use consultation request within the electronic medical record, patient and provider brochures, and informational booths and kiosks. Collaborations were developed with various clinical services to promote referrals. Several other services, such as Primary Care, Geriatrics, the Move! Weight Management Program, Cardiology (including Congestive Heart Failure), Hematology/Oncology, and Mental Health referred patients to the GWC.