User login

Lipoprotein(a) Elevation: A New Diagnostic Code with Relevance to Service Members and Veterans (FULL)

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) remains the leading cause of global mortality. In 2015, 41.5% of the US population had at least 1 form of CVD and CVD accounted for nearly 18 million deaths worldwide.1,2 The major disease categories represented include myocardial infarction (MI), sudden death, strokes, calcific aortic valve stenosis (CAVS), and peripheral vascular disease.1,2 In terms of health care costs, quality of life, and caregiver burden, the overall impact of disease prevalence continues to rise.1,3-6 There is an urgent need for more precise and earlier CVD risk assessment to guide lifestyle and therapeutic interventions for prevention of disease progression as well as potential reversal of preclinical disease. Even at a young age, visible coronary atherosclerosis has been found in up to 11% of “healthy” active individuals during autopsies for trauma fatalities.7,8

The impact of CVD on the US and global populations is profound. In 2011, CVD prevalence was predicted to reach 40% by 2030.9 That estimate was exceeded in 2015, and it is now predicted that by 2035, 45% of the US population will suffer from some form of clinical or preclinical CVD. In 2015, the decadeslong decline in CVD mortality was reversed for the first time since 1969, showing a 1% increase in deaths from CVD.1 Nearly 300,000 of those using US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) services were hospitalized for CVD between 2010 and 2014.10 The annual direct and indirect costs related to CVD in the US are estimated at $329.7 billion, and these costs are predicted to top $1 trillion by 2035.1 Heart attack, coronary atherosclerosis, and stroke accounted for 3 of the 10 most expensive conditions treated in US hospitals in 2013.11 Globally, the estimate for CVD-related direct and indirect costs was $863 billion in 2010 and may exceed $1 trillion by 2030.12

The nature of military service adds additional risk factors, such as posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, sleep disorders and physical trauma which increase CVD morbidity/ mortality in service members, veterans, and their families.13-16 In addition, living in lowerincome areas (countries or neighborhoods) can increase the risk of both CVD incidence and fatalities, particularly in younger individuals.17-20 The Military Health System (MHS) and VA are responsible for the care of those individuals who have voluntarily taken on these additional risks through their time in service. This responsibility calls for rapid translation to practice tools and resources that can support interventions to minimize as many modifiable risk factors as possible and improve longterm health. This strategy aligns with the World Health Organization’s (WHO) focus on prevention of disease progression through interventions targeting modifiable risk.3-6,21-23 The driving force behind the launch of the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Million Hearts program was the goal of preventing 1 million heart attacks and strokes by 2017 with risk reduction through aspirin, blood pressure control, cholesterol management, smoking cessation, sodium reduction, and physical activity.24,25 While some reductions in CVD events have been documented, the outcomes fell short of the goals set, highlighting both the need and value of continued and expanded efforts for CVD risk reduction.26

More precise assessment of risk factors during preventative care, as well as after a diagnosis of CVD, may improve the timeliness and precision of earlier interventions (both lifestyle and therapeutic) that reduce CVD morbidity and mortality.27 Personalized or precision medicine approaches take into account differences in socioeconomic, environmental, and lifestyle factors that are potentially reversible, as well as gender, race, and ethnicity.28-31 Current methods of predicting CVD risk have considerable room for improvement.27 About 40% of patients with newly diagnosed CVD have normal traditional cholesterol profiles, including those whose first cardiac event proves fatal.29-33 Currently available risk scores (hundreds have been described in the literature) mischaracterize risk in minority populations and women, and have shown deficiencies in identifying preclinical atherosclerosis.34,35 The failure to recognize preclinical CVD in military personnel during their active duty life cycle results in missed opportunities for improved health and readiness sustainment.

Most CVD risk prediction models incorporate some form of blood lipids. Total cholesterol (TC) is most commonly used in clinical practice, along with high-density lipoprotein (HDLC), low-density lipoprotein (LDLC), and triglycerides (TG).23,27,36 High LDLC and/or TC are well established as lipid-related CVD risk factors and are incorporated into many CVD risk scoring systems/models described in the literature.27 LDLC reduction is commonly recommended as CVD prevention, but even with optimal statin treatment, there is still considerable residual risk for new and recurrent CVD events.28,32,34,35,37-42

Incorporating novel biomarkers and alternative lipid measurements may improve risk prediction and aid targeted treatment, ultimately reducing CVD events.27 Apolipoprotein B (ApoB) is a major atherogenic component embedded in LDL and VLDL correlating to non-HDLC and may be useful in the setting of triglycerides ≥ 200 mg/d as levels > 130 mg/ dL appear to be risk-enhancing, but measurements may be unreliable.43 According to the 2018 Cholesterol Guidelines, lipoprotein(a) [Lp(a)] elevation also is recognized as a risk-enhancing factor that is particularly implicated when there is a strong family history of premature atherosclerotic CVD or personal history of CVD not explained by major risk factors.43

Lp(a) elevation is a largely underrecognized category of lipid disorder that impacts up to 20% to 30% of the population globally and within the US, although there is considerable variability by geographic location and ethnicity.44 Globally, Lp(a) elevation places > 1 billion people at moderate to high risk for CVD.44 Lp(a) has a strong genetic component and is recognized as a distinct and independent risk factor for MI, sudden death, strokes and CAVS. Lp(a) has an extensive body of evidence to support its distinct role both as a causal factor in CVD and as an augmentation to traditional risk factors.44-48

Lipoproteni(a) Elevation Use For Diagnosis

The importance of Lp(a) elevation as a clinical diagnosis rather than a laboratory abnormality alone was brought forward by the Lipoprotein(a) Foundation. Its founder, Sandra Tremulis, is a survivor of an acute coronary event that occurred when she was 39-years old, despite running marathons and having none of the traditional CVD lifestyle risk factors.49 This experience inspired her to create the Lipoprotein(a) Foundation to give a voice to families living with or at risk for CVD due to Lp(a) elevation.

As often happens in the progress of medicine, patients and their families drive change based on their personal experiences with the gaps in standard clinical practice. It was this foundation—not a member of the medical establishment—that submitted the formal request for the addition of new ICD-10-CM diagnostic and family history codes for Lp(a) elevation during the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) September 2017 ICD-10-CM Coordination and Maintenance Committee meeting.50 In June 2018, the final ICD-10-CM code addenda for 2019 was released and included the new codes E78.41 (Elevated Lp[a]) and Z83.430 (Family history of elevated Lp[a]).52 After the new codes were approved, both the American Heart Association and the National Lipid Association added recommendations regarding Lp(a) testing to their clinical practice guidelines.43,52

Practically, these codes standardize billing and payment for legitimate clinical work and laboratory testing. Prior to the addition of Lp(a) elevation as a clinical diagnosis, testing and treatment of Lp(a) elevation was considered experimental and not medically necessary until after a cardiovascular event had already occurred. Services for Lp(a) elevation were therefore not reimbursed by many healthcare organizations and insurance companies. The new ICD-10-CM codes encourage the assessment of Lp(a) both in individuals with early onset major CVD events and in presumably fit, healthy individuals, particularly when there is a family history of Lp(a) elevation. Given that Lp(a) levels do not change significantly over time, the current understanding is that only a single measurement is needed to define the individual risk over a lifetime.41,42,44,45 As therapies targeting Lp(a) levels evolve, repeated measurements may be indicated to monitor response and direct changes in management. “Elevated Lipoprotein(a)” is the first laboratory testing abnormality that has achieved the status of a clinical diagnosis.

Lp(a) Measurements

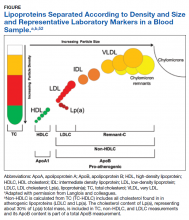

There is considerable complexity to the measurement of lipoproteins in blood samples due to heterogeneity in both density and size of particles as illustrated in the Figure.53

For traditional lipids measured in clinical practice, the size and density ranges from small high-density lipoprotein (HDL) through LDLC and intermediate- density lipoprotein (IDL) to the largest least dense particles in the very low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) and chylomicron remnant fractions. Standard lipid profiles consist of mass concentration measurements (mg/dL) of TC, TG, HDLC, and LDLC.53 Non-HDLC (calculated as: TC−HDLC) consists of all cholesterol found in atherogenic lipoproteins, including remnant-C and Lp(a). Until recently, the cholesterol content of Lp(a), corresponding to about 30% of Lp(a) total mass, was included in the TC, non-HDLC and LDLC measurements with no separate reporting by the majority of clinical laboratories.

After > 50 years of research on the structure and biochemistry of Lp(a), the physiology and biological functions of these complex and polymorphic lipoprotein particles are not fully understood. Lp(a) is composed of a lipoprotein particle similar in composition to LDL (protein and lipid), containing 1 molecule of ApoB wrapped around a core of cholesteryl ester and triglyceride with phospholipids and unesterified cholesterol at its surface.48 The presence of a unique hydrophilic, highly glycosylated protein referred to as apolopoprotienA (apo[a]), covalently attached to ApoB-100 by a single disulfide bridge, differentiates Lp(a) from LDL.48 Cholesterol rich ApoB is an important component within many lipoproteins pathogenic for atherosclerosis and CVD.45,47,53

The apo(a) contributes to the increased density of Lp(a) compared to LDLC with associated reduced binding affinity to the LDL receptor. This reduced receptor binding affinity is a presumed mechanism for the lack of Lp(a) plasma level response to statin therapies, which increase hepatic LDL receptor activity.47 Apo(a) evolved from the plasminogen gene through duplication and remodeling and demonstrates extensive heterogeneity in protein size, with > 40 different apo(a) isoforms resulting in > 40 different Lp(a) particle sizes. Size of the apo(a) particle is determined by the number of pleated structures known as kringles. Most people (> 80%) carry 2 different-sized apo(a) isoforms. Plasma Lp(a) level is determined by the net production of apo(a) in each isoform, and the smaller apo(a) isoforms are associated with higher plasma levels of Lp(a).45

Given the heterogeneity in Lp(a) molecular weight, which can vary even within individuals, recommendations have been made for reporting results as particle numbers or concentrations (nmol/L or mmol/L) rather than as mass concentration (mg/dL).55 However, the majority of the large CVD morbidity and mortality outcomes studies used Lp(a) mass concentration levels in mg/ dL to characterize risk levels.56,57 There is no standardized method to convert Lp(a) measurements from mg/dL to nmol/L.55 Current assays using WHO standardized reagents and controls are reliable for categorizing risk levels.58

The European Atherosclerosis Society consensus panel recommended that desirable Lp(a) levels should be below the 80th percentile (< 50 mg/dL or < 125 nmol/L) in patients with intermediate or high CVD risk.59 Subsequent epidemiological and Mendelian randomization studies have been performed in general populations with no history of CVD and demonstrated that increased CVD risk can be detected with Lp(a) levels as low as 25 to 30 mg/dL.56,60-63 In secondary prevention populations with prior CVD and optimal treatment (statins, antiplatelet drugs), recurrent event risk was also increased with elevated Lp(a).63-66

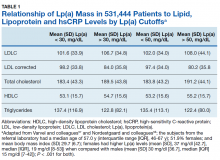

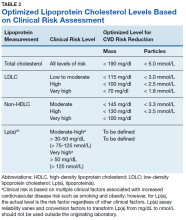

Using immunoturbidometric assays, Varvel and colleagues reported the prevalence of elevated Lp(a) mass concentration levels (mg/dL) in > 500,000 US patients undergoing clinical evaluations based on data from a referral laboratory of patients.58 The mean Lp(a) levels were 34.0 mg/dL with median (interquartile range [IQR]) levels at 17 (7-47) mg/dL and overall range of 0 to 907 mg/dL.58 Females had higher Lp(a) levels compared to males but no ethnic or racial breakdown was provided. Lp(a) levels > 30 mg/dL and > 50 mg/dL were present in 35% and 24% of subjects, respectively. Table 1 displays the relationship between various Lp(a) level cut-offs to mean levels of LDLC, estimated LDLC corrected for Lp(a), TC, HDLC, and TG.58 The data demonstrate that Lp(a) elevation cannot be inferred from LDLC levels nor from any of the other traditional lipoprotein measures. Patients with high risk Lp(a) levels may have normal LDLC. While Lp(a) thresholds have been identified for stratification of CVD risk, the target levels for risk reduction have not been specifically defined, particularly since therapies are not widely available for reduction of Lp(a). Table 2 provides an overview of clinical lipoprotein measurements that may be reasonable targets for therapeutic interventions and reduction of CVD risk.44,53,55 In general, existing studies suggest that radical reduction (> 80%) is required to impact long-term outcomes, particularly in individuals with severe disease.68,69

LDLC reduction alone leaves a residual CVD risk that is greater than the risk reduced.40 In addition, the autoimmune inflammation and lipid specific autoantibodies play an important role in increased CVD morbidity and mortality risk.70,71 The presence of autoantibodies such as antiphospholipid antibodies (without a specific autoimmune disease diagnosis) increases the risk of subclinical atherosclerosis.72,73 Certain autoimmune diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus are recognized as independent risk factors for CVD.74,75 Autoantibodies appear to mediate CVD events and mortality risk, independent of traditional therapies for risk reduction.73 Further research is needed to clarify the role of autoantibodies as markers of increased or decreased CVD risk and their mechanism of action.

Autoantibodies directed at new antigens in lipoproteins within atherosclerotic lesions can modulate the impact of atherosclerosis via activation of the innate and adaptive immune system.76 The lipid-associated neopeptides are recognized as damage-associated or danger- associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), also known as alarmins, which signal molecules that can trigger and perpetuate noninfectious inflammatory responses.77-79 Plasma autoantibodies (immunoglobulin M and G [IgM, IgG]) modify proinflammatory oxidation-specific epitopes on oxidized phospholipids (oxPL) within lipoproteins and are linked with markers of inflammation and CVD events.80-82 Modified LDLC and ApoB-100 immune complexes with specific autoantibodies in the IgG class are associated with increased CVD.76 These and other risk-modulating autoantibodies may explain some of the variability in CVD outcomes by ethnicity and between individuals.

Some antibodies to oxidized LDL (ox-LDL) may have a protective role in the development of atherosclerosis.83,84 In a cohort of > 500 women, the number of carotid atherosclerotic plaques and total carotid plaque area were inversely correlated with a specific IgM autoantibody (MDA-p210).84 High concentrations of Lp(a)- containing circulating immune complexes and Lp(a)-specific IgM and IgG have been described in patients with coronary heart disease (CHD).85 Like ox-LDL, oxidized Lp(a) [ox-Lp(a)] is more potent than native Lp(a) in increasing atherosclerosis risk and is increased in patients with CHD compared to healthy controls.86-88 Ox-Lp(a) levels may represent an even stronger risk marker for CVD than ox-LDL.85

Possible Mechanisms of Pathogenesis

While the precise quantification of Lp(a) in human plasma (or serum) has been challenging, current clinical laboratories use standardized international reference reagents and controls in their assays. Most current Lp(a) assays are based on immunological methods (eg, immunonephelometry, immunoturbidimetry, or enzyme linked immunosorbent assay [ELISA]) using antibodies against apo(a).89 Apo(a) contains 10 subtypes of kringle IV and 1 copy of kringle V. Some assays use antibodies against kringle-IV type 2; however, it has been recommended that newer methods should use antibodies against the specific bridging kringle-IV Type 9 domain, which has a more stable bond and is present as a single copy.48,89 Other approaches to Lp(a) measurement include ultraperformance liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry that can determine both the concentration and particle size of apo(a).48,90 For routine clinical care, currently available assays reporting in mg/dL can be considered fairly accurate for separating low-risk from moderate-to-high-risk patients.45

The physiologic role of Lp(a) in humans remains to be fully defined and individuals with extremely low plasma Lp(a) levels present no disease or deficiency syndromes.91 Lp(a) accumulates in endothelial injuries and binds to components of the vessel wall and subendothelial matrix, presumably due to the strong lysine binding site in apo(a).46 Mediated by apo(a), the binding stimulates chemotactic activation of monocytes/macrophages and thereby modulating angiogenesis and inflammation.89 Lp(a) may contribute to CVD and CAVS via its LDL-like component, with proinflammatory effects of oxidized phospholipids (OxPL) on both ApoB and apo(a) and antifibrinolytic/prothrombotic effects of apo(a).92 In Vitro studies have demonstrated that apo(a) modifies cellular function of cultured vascular endothelial cells (promoting stress fiber formation, endothelial contraction and vascular permeability), smooth muscles, and monocytes/ macrophages (promoting differentiation of proinflammatory M1-1 type macrophages) via complex mechanisms of cell signaling and cytokine production.89 Lp(a) is the only monogenetic risk factor for aortic valve calcification and stenosis93 and is strongly linked specifically with the single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) rs10455872 in the gene LPA encoding for apo(a).94

CVD Risk Predictive Value

There are a large number of studies demonstrating that Lp(a) elevations are an independent predictor of adverse cardiovascular outcomes including MI, sudden death, strokes, calcific aortic valve stenosis and peripheral vascular disease (Table 3). The Copenhagen City Heart Study and Copenhagen General Population Study are well known prospective population- based cohort studies that track outcomes through national patient registries.95 These studies demonstrate increased risk for MI, CHD, CAVS, and heart failure when subjects with very high Lp(a) levels (50-115 mg/dL) are compared with subjects with very low Lp(a) levels (< 5 mg/dL).96-100 Subjects with less extreme Lp(a) elevations (> 30 mg/dL) also show increased risk of CVD when they have comorbid LDLC elevations.101 However, the Copenhagen studies are composed exclusively of white subjects and the effects of Lp(a) are known to vary with race or ethnicity.

The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) recruited an ethnically diverse sample of > 6,000 Americans, aged 45 to 84 years, without CVD, into an ongoing prospective cohort study. Research using subjects from this study has found consistently increased risk of CHD, heart failure, subclinical aortic valve calcification, and more severe CAVS in white subjects with elevated Lp(a).60,102,103 Black subjects with elevated Lp(a) had increased risk of CHD and more severe CAVS and Hispanic subjects with Lp(a) elevation were at higher risk for CHD.60,102 So far, no studies of MESA subjects have identified a relationship between Lp(a) elevation and CVD events for Asian-Americans subjects (predominantly of Chinese descent). There is a need for ongoing research to more precisely define relevant cut-off levels by race, ethnicity and sex.

The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study was a prospective multiethnic cohort study including > 15,000 US adults, aged 45 to 64 years.103 Lp(a) elevations in this cohort were associated with greater risks for first CVD events, heart failure, and recurrent CVD events.61,64,105 The risk of stroke for subjects with elevated Lp(a) was greater for black and white women, and for black men.61,106 However, a meta-analysis of case-control studies showed increased ischemic stroke risk in both men and women with elevated Lp(a).57

A recent European meta-analysis collected blood samples and outcome data from > 50,000 subjects in 7 prospective cohort studies. Using a central laboratory to standardize Lp(a) measurements, researchers found increased risk of major coronary events and new CVD in subjects with Lp(a) > 50 mg/dL compared to those below that threshold.107

Although many of these studies show modest increases in risk of CVD events with Lp(a) elevation, it should be noted that other studies do not demonstrate such consistent associations. This is particularly true in studies of women and nonwhite ethnic groups.103,108-112 The variability of study results may be due to other confounding factors such as autoantibodies that either upregulate or downregulate atherogenicity of LDLC and potentially other lipoproteins. This is particularly relevant to women who have an increased risk for autoimmune disease.

Lp(a) has significant genetic heritability—75% in Europeans and 85% in African Americans.113 In whites, the LPA gene on chromosome 6p26- 27 with the polymorphism genetic variants rs10455872 and rs3798220 is consistently associated with elevated Lp(a) levels.63,100,113 However, the degree of Lp(a) elevation associated with these specific genetic variants varies by ethnicity.78,113,115

Lifestyle and Cardiovascular Health

It is noteworthy that the Lp(a) genetic risks can also be modified by lifestyle risk reduction even in the absence of significant blood level reductions. For example, Khera and colleagues constructed a genetic risk profile for CVD that included genes related to Lp(a).116 Subjects with high genetic risk were more likely to experience CVD events compared with subjects with low genetic risk. However, risks for CVD were attenuated by 4 healthy lifestyle factors: current nonsmoker, body mass index < 30, at least weekly physical activity, and a healthy diet. Subjects with high genetic risk and an unhealthy lifestyle (0 or 1 of the 4 healthy lifestyle factors) were the most likely to develop CVD (Hazard ratio [HR], 3.5), but that risk was lower for subjects with healthy (3 or 4 of the 4 healthy lifestyle factors) and intermediate lifestyles (2 of the 4 healthy lifestyle factors) (HR, 1.9 and 2.2, respectively), despite despite high genetic risk for CVD.

While the independent CVD risk associated with elevated Lp(a) does not appear to be responsive to lifestyle risk reduction alone, certainly elevated LDLC and traditional risk factors can increase the overall CVD risk and are worthy of preventive interventions. In particular, inflammation from any source exacerbates CVD risk. Proatherogenic diet, insufficient sleep, lack of exercise, and maladaptive stress responses are other targets for personalized CVD risk reduction. 28,117 Studies of dietary modifications and other lifestyle factors have shown reduced risk of CVD events, despite lack of reduction in Lp(a) levels.119,120 It is noteworthy that statin therapy (with or without ezetimibe) fails to impact CAVS progression, likely because statins either raise or have no effect on Lp(a) levels.92,119

Until recently, there has been no evidence supporting any therapeutic intervention causing clinically meaningful reductions in Lp(a). Table 4 lists major drug classes and their effects on Lp(a) and CVD outcomes; however, a detailed discussion of each of these therapies is beyond the scope of this review. Drugs that reduce Lp(a) by 20-30% have varying effects on CVD outcomes, from no effect122,123 to a 10% to 20% decrease in CVD events when compared with a placebo.124,125 Because these drugs also produce substantial reductions in LDLC, it is not possible to determine how much of the beneficial effects are due to reductions in Lp(a).

Lipoprotein apheresis produces profound reductions in Lp(a) of 60 to 80% in very highrisk populations.69,126 Within-subjects comparisons show up to 80% reductions in CVD events, relative to event rates prior to treatment initiation.69,127 Early trials of antisense oligonucleotide against apo(a) therapies show potential to produce similar outcomes.128,129 These treatments may be particularly effective in patients with isolated Lp(a) elevations.

Summary

Lp(a) elevation is a major contributor to cardiovascular disease risk and has been recognized as an ICD-10-CM coded clinical diagnosis, the first laboratory abnormality to be defined a clinical disease in the asymptomatic healthy young individuals. This change addresses currently under- diagnosed CVD risk independent of LDLC reduction strategies. A brief overview of recent guidelines for the clinical use of Lp(a) testing from the American Heart Association43,151 and the National Lipid Association52 can be found in Table 5. Although drug therapies for lowering Lp(a) levels remain limited, new treatment options are actively being developed.

Many Americans with high Lp(a) have not yet been identified. Expanded one-time screening can inform these patients of their cardiovascular risk and increase their access to early, aggressive lifestyle modification and optimal lipid-lowering therapy. Given the further increased CVD risk factors for military service members and veterans, a case can be made for broader screening and enhanced surveillance of elevated Lp(a) in these presumably healthy and fit individuals as well as management focused on modifiable risk factors.

Acknowledgements

This program initiative was conducted by the Henry M. Jackson Foundation for the Advancement of Military Medicine, Inc. as part of the Integrative Cardiac Health Project at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center (WRNMMC), and is made possible by a cooperative agreement that was awarded and administered by the US Army Medical Research & Materiel Command (USAMRMC), at Fort Detrick under Contract Number: W81XWH-16-2-0007. It reflects literature review preparatory work for a research protocol but does not involve an actual research project. The work in this manuscript was supported by the staff of the Integrative Cardiac Health Project (ICHP) with special thanks to Claire Fuller, Elaine Walizer, Dr. Mariam Kashani and the entire health coaching team.

1. American Heart Association. Cardiovascular disease: a costly burden for America, projections through 2035. http://www.heart.org/idc/groups /heart-public/@wcm/@adv/documents/downloadable /ucm_491543.pdf. Accessed October 10, 2019.

2. Benjamin EJ, Virani SS, Callaway CW, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2018 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2018;137(12):e67-e492.

3. Roth GA, Johnson C, Abajobir A, et al. Global, regional, and national burden of cardiovascular diseases for 10 causes, 1990 to 2015. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70(1):1-25.

4. Thrift AG, Cadilhac DA, Thayabaranathan T, et al. Global stroke statistics. Int J Stroke. 2014;9(1):6-18.

5. Murray CJ, Barber RM, Foreman KJ, et al; GBD 2013 DALYs and HALE Collaborators. Global, regional, and national disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 306 diseases and injuries and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 188 countries, 1990-2013: quantifying the epidemiological transition. Lancet. 2015;386(10009):2145-2191.

6. Mukherjee D, Patil CG. Epidemiology and the global burden of stroke. World Neurosurg. 2011;76(6 suppl):S85-S90.

7. Joseph A, Ackerman D, Talley JD, Johnstone J, Kupersmith J. Manifestations of coronary atherosclerosis in young trauma victims—an autopsy study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1993;22(2):459-467.

8. Webber BJ, Seguin PG, Burnett DG, Clark LL, Otto JL. Prevalence of and risk factors for autopsy-determined atherosclerosis among US service members, 2001-2011. JAMA. 2012;308(24):2577-2583.

9. Heidenreich PA, Trogdon JG, Khavjou OA, et al. Forecasting the future of cardiovascular disease in the United States: a policy statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2011;123(8):933-944.

10. Krishnamurthi N, Francis J, Fihn SD, Meyer CS, Whooley MA. Leading causes of cardiovascular hospitalization in 8.45 million US veterans. PLoS One. 2018;13(3):e0193996.

11. Torio CM, Moore BJ. National inpatient hospital costs: the most expensive conditions by payer. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Statistical Brief No. 204. http:// www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb204-Most -Expensive-Hospital-Conditions.pdf. Published May 2016. Accessed October 10, 2019.

12. Bloom DE, Cafiero ET, Jané-Llopis E, et al. The global economic burden of noncommunicable diseases. https:// www.weforum.org/reports/global-economic-burden-non -communicable-diseases. Published September 18, 2011. Accessed October 10, 2019.

13. Crum-Cianflone NF, Bagnell ME, Schaller E, et al. Impact of combat deployment and posttraumatic stress disorder on newly reported coronary heart disease among US active duty and reserve forces. Circulation. 2014;129(18):1813-1820.

14. Fryar CD, Herrick K, Afful J, Ogden CL. Cardiovascular disease risk factors among male veterans, U.S., 2009- 2012. Am J Prev Med. 2016;50(1):101-105.

15. Ulmer CS, Bosworth HB, Germain A, et al; VA Mid-Atlantic Mental Illness Research Education and Clinical Center Registry Workgroup. Associations between sleep difficulties and risk factors for cardiovascular disease in veterans and active duty military personnel of the Iraq and Afghanistan conflicts. J Behav Med. 2015;38(3):544-555.

16. Lutwak N, Dill C. Military sexual trauma increases risk of post-traumatic stress disorder and depression thereby amplifying the possibility of suicidal ideation and cardiovascular disease. Mil Med. 2013;178(4):359-361.

17. Bowry ADK, Lewey J, Dugani SB, Choudhry NK. The burden of cardiovascular disease in low- and middle-income countries: epidemiology and management. Can J Cardiol. 2015;31(9):1151-1159.

18. Reinier K, Stecker EC, Vickers C, Gunson K, Jui J, Chugh SS. Incidence of sudden cardiac arrest is higher in areas of low socioeconomic status: a prospective two year study in a large United States community. Resuscitation. 2006;70(2):186-192.

19. Reinier K, Thomas E, Andrusiek DL, et al; Resuscitation Outcomes Consortium Investigators. Socioeconomic status and incidence of sudden cardiac arrest. CMAJ. 2011;183(15):1705-1712.

20. Yusuf S, Rangarajan S, Teo K, et al; PURE Investigators. Cardiovascular risk and events in 17 low-, middle-, and high-income countries. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(9):818-827.

21. World Health Organization. Health topics: cardiovascular disease. http://www.who.int/cardiovascular_diseases/en/. Updated 2019. Accessed October 10, 2019.

22. Berkowitz AL. Stroke and the noncommunicable diseases: A global burden in need of global advocacy. Neurology. 2015;84(21):2183-2184.

23. Holt T. Predicting cardiovascular disease. BMJ. 2016;353:i2621.

24. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Million hearts: strategies to reduce the prevalence of leading cardiovascular disease risk factors—United States, 2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(36):1248-1251.

25. Fryar CD, Chen TC, Li X. Prevalence of uncontrolled risk factors for cardiovascular disease: United States, 1999- 2010. NCHS Data Brief. 2012;103:1-8.

26. Ritchey MD, Loustalot F, Wall HK, et al. Million Hearts: description of the national surveillance and modeling methodology used to monitor the number of cardiovascular events prevented during 2012-2016. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6(5):pii:e00602.

27. Goff DC Jr, Lloyd-Jones DM, Bennett G, et al. 2013 ACC/ AHA guideline on the assessment of cardiovascular risk: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(25 pt B):2935-2959.

28. Yusuf S, Hawken S, Ounpuu S, et al. Effect of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with myocardial infarction in 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): casecontrol study. Lancet. 2004;364(9438):937-952.

29. Eckel RH, Jakicic JM, Ard JD, et al. 2013 AHA/ACC guideline on lifestyle management to reduce cardiovascular risk: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(25 pt B):2960-2984.

30. Bansilal S, Castellano JM, Fuster V. Global burden of CVD: focus on secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Int J Cardiol. 2015;201(suppl 1):S1-S7.

31. Havranek EP, Mujahid MS, Barr DA, et al. Social determinants of risk and outcomes for cardiovascular disease: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2015;132(9):873-898.

32. Miedema MD, Garberich RF, Schnaidt LJ, et al. Statin eligibility and outpatient care prior to ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6(4): pii: e005333.

33. Noheria A, Teodorescu C, Uy-Evanado A, et al. Distinctive profile of sudden cardiac arrest in middle-aged vs. older adults: a community-based study. Int J Cardiol. 2013;168(4):3495-3499.

34. Lieb W, Enserro DM, Larson MG, Vasan RS. Residual cardiovascular risk in individuals on lipid-lowering treatment: quantifying absolute and relative risk in the community. Open Heart. 2018;5(1):e000722.

35. Sachdeva A, Cannon CP, Deedwania PC, et al. Lipid levels in patients hospitalized with coronary artery disease: an analysis of 136,905 hospitalizations in Get With The Guidelines. Am Heart J. 2009;157(1):111-117.e2.

36. Damen JA, Hooft L, Schuit E, et al. Prediction models for cardiovascular disease risk in the general population: systematic review. BMJ. 2016;353:i2416.

37. Fulcher J, O’Connell R, Voysey M, et al; Cholesterol Treatment Trialists (CTT) Collaboration. Efficacy and safety of LDL-lowering therapy among men and women: metaanalysis of individual data from 174,000 participants in 27 randomised trials. Lancet. 2015;385(9976):1397-1405.

38. Perrone V, Sangiorgi D, Buda S, Degli Esposti L. Residual cardiovascular risk in patients who received lipid-lowering treatment in a real-life setting: retrospective study. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2016;8:649-655.

39. Sirimarco G, Labreuche J, Bruckert E, et al; PERFORM and SPARCL Investigators. Atherogenic dyslipidemia and residual cardiovascular risk in statin-treated patients. Stroke. 2014;45(5):1429-1436.

40. Kones R. Molecular sources of residual cardiovascular risk, clinical signals, and innovative solutions: relationship with subclinical disease, undertreatment, and poor adherence: implications of new evidence upon optimizing cardiovascular patient outcomes. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2013;9:617-670.

41. Hayashi M, Shimizu W, Albert CM. The spectrum of epidemiology underlying sudden cardiac death. Circ Res. 2015;116(12):1887-1906.

42. Downs JR, O’Malley PG. Management of dyslipidemia for cardiovascular disease risk reduction: synopsis of the 2014 U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs and U.S. Department of Defense clinical practice guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(4):291-297.

43. Grundy SM, Stone NJ, Bailey AL, et al. 2018 AHA/ACC/ AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/ NLA/PCNA Guideline on the management of blood cholesterol: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73(24):3168-3209.

44. Tsimikas S, Fazio S, Ferdinand KC, et al. NHLBI Working Group recommendations to reduce lipoprotein(a)-mediated risk of cardiovascular disease and aortic stenosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71(2):177-192.

45. Tsimikas S. A test in context: Lipoprotein(a): diagnosis, prognosis, controversies, and emerging therapies. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69(6):692-711.

46. Ellis KL, Boffa MB, Sahebkar A, Koschinsky ML, Watts GF. The renaissance of lipoprotein(a): brave new world for preventive cardiology? Prog Lipid Res. 2017;68:57-82.

47. Thompson GR, Seed M. Lipoprotein(a): the underestimated cardiovascular risk factor. Heart. 2014;100(7):534-535.

48. Marcovina SM, Albers JJ. Lipoprotein (a) measurements for clinical application. J Lipid Res. 2016;57(4):526-537.

49. Tremulis SR. Founder’s Story: Lipoprotein(a) Foundation. https://www.lipoproteinafoundation.org/page /Sandrastory. Accessed October 10, 2019.

50. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. ICD-10 Coordination and Maintenance Committee meeting, September 12-13, 2017 diagnosis agenda. https://www.cdc. gov/nchs/data/icd/Topic_Packet_Sept_2017.pdf. Accessed October 10, 2019.

51. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. 2019 ICD- 10-CM codes descriptions in tabular order. https://www. cms.gov/Medicare/Coding/ICD10/2019-ICD-10-CM.html. Accessed October 10, 2019.

52. Wilson DP, Jacobson TA, Jones PH, et al. Use of Lipoprotein(a) in clinical practice: a biomarker whose time has come. A scientific statement from the National Lipid Association. J Clin Lipidol. 2019;13(3):374-392.

53. Langlois MR, Chapman MJ, Cobbaert C, et al. Quantifying atherogenic lipoproteins: current and future challenges in the era of personalized medicine and very low concentrations of ldl cholesterol. A consensus statement from EAS and EFLM. Clin Chem. 2018;64(7):1006-1033.

54. Shapiro MD, Fazio S. Apolipoprotein B-containing lipoproteins and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. F1000Res. 2017;6:134.

55. Tsimikas S, Fazio S, Viney NJ, Xia S, Witztum JL, Marcovina SM. Relationship of lipoprotein(a) molar concentrations and mass according to lipoprotein(a) thresholds and apolipoprotein(a) isoform size. J Clin Lipidol. 2018;12(5):1313-1323.

56. Erqou S, Kaptoge S, Perry PL, et al; Emerging Risk Factors Collaboration. Lipoprotein(a) concentration and the risk of coronary heart disease, stroke, and nonvascular mortality. JAMA. 2009;302(4):412-423.

57. Nave AH, Lange KS, Leonards CO, et al. Lipoprotein (a) as a risk factor for ischemic stroke: a meta-analysis. Atherosclerosis. 2015;242(2):496-503.

58. Varvel S, McConnell JP, Tsimikas S. Prevalence of elevated Lp(a) mass levels and patient thresholds in 532,359 patients in the United States. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2016;36(11):2239-2245.

59. Nordestgaard BG, Chapman MJ, Ray K, et al; European Atherosclerosis Society Consensus Panel. Lipoprotein(a) as a cardiovascular risk factor: current status. Eur Heart J. 2010;31(23):2844-2853.

60. Guan W, Cao J, Steffen BT, et al. Race is a key variable in assigning lipoprotein(a) cutoff values for coronary heart disease risk assessment: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2015;35(4):996-1001.

61. Virani SS, Brautbar A, Davis BC, et al. Associations between lipoprotein(a) levels and cardiovascular outcomes in black and white subjects: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study. Circulation. 2012;125(2):241-249.

62. Tsimikas S, Mallat Z, Talmud PJ, et al. Oxidation-specific biomarkers, lipoprotein(a), and risk of fatal and nonfatal coronary events. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56(12):946-955.

63. Clarke R, Peden JF, Hopewell JC, et al; PROCARDIS Consortium. Genetic variants associated with Lp(a) lipoprotein level and coronary disease. New Eng J Med. 2009;361(26):2518-2528.

64. Wattanakit K, Folsom AR, Chambless LE, Nieto FJ. Risk factors for cardiovascular event recurrence in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study. Am Heart J. 2005;149(4):606-612.

65. Ruotolo G, Lincoff MA, Menon V, et al. Lipoprotein(a) is a determinant of residual cardiovascular risk in the setting of optimal LDL-C in statin-treated patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease [Abstract 17400]. Circulation. 2018;136(suppl 1):A17400.

66. Suwa S, Ogita M, Miyauchi K, et al. Impact of lipoprotein (a) on long-term outcomes in patients with coronary artery disease treated with statin after a first percutaneous coronary intervention. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2017;24(11):1125-1131.

67. Nestel PJ, Barnes EH, Tonkin AM, et al. Plasma lipoprotein(a) concentration predicts future coronary and cardiovascular events in patients with stable coronary heart disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2013;33(12):2902-2908.

68. Burgess S, Ference BA, et al. Association of LPA variants with risk of coronary disease and the implications for lipoprotein(a)-lowering therapies: a Mendelian randomization analysis. JAMA Cardiol. 2018;3(7):619-627.

69. Roeseler E, Julius U, Heigl F, et al; Pro(a)LiFe-Study Group. Lipoprotein apheresis for lipoprotein(a)-associated cardiovascular disease: prospective 5 years of followup and apolipoprotein(a) characterization. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2016;36(9):2019-2027.

70. Matsuura E, Atzeni F, Sarzi-Puttini P, Turiel M, Lopez LR, Nurmohamed MT. Is atherosclerosis an autoimmune disease? BMC Med. 2014;12:47.

71. Ahearn J, Shields KJ, Liu CC, Manzi S. Cardiovascular disease biomarkers across autoimmune diseases. Clin Immunol. 2015;161(1):59-63.

72. Di Minno MND, Emmi G, Ambrosino P, et al. Subclinical atherosclerosis in asymptomatic carriers of persistent antiphospholipid antibodies positivity: a cross-sectional study. Int J Cardiol. 2019;274:1-6.

72. Di Minno MND, Emmi G, Ambrosino P, et al. Subclinical atherosclerosis in asymptomatic carriers of persistent antiphospholipid antibodies positivity: a cross-sectional study. Int J Cardiol. 2019;274:1-6.

73. Iseme RA, McEvoy M, Kelly B, et al. A role for autoantibodies in atherogenesis. Cardiovasc Res. 2017;113(10):1102-1112.

74. Sinicato NA, da Silva Cardoso PA, Appenzeller S. Risk factors in cardiovascular disease in systemic lupus erythematosus. Curr Cardiol Rev. 2013;9(1):15-19.

75. Sciatti E, Cavazzana I, Vizzardi E, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus and endothelial dysfunction: a close relationship. Curr Rheumatol Rev. 2018;15(3):177-188.

76. Prasad A, Clopton P, Ayers C, et al. Relationship of autoantibodies to MDA-LDL and ApoB-Immune complexes to sex, ethnicity, subclinical atherosclerosis, and cardiovascular events. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2017;37(6):1213-1221.

77. Miller YI, Choi SH, Wiesner P, et al. Oxidation-specific epitopes are danger-associated molecular patterns recognized by pattern recognition receptors of innate immunity. Circ Res. 2011;108(2):235-248.

78. Libby P, Lichtman AH, Hansson GK. Immune effector mechanisms implicated in atherosclerosis: from mice to humans. Immunity. 2013;38(6):1092-1104.

79. Binder CJ, Papac-Milicevic N, Witztum JL. Innate sensing of oxidation-specific epitopes in health and disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2016;16(8):485-497.

80. Freigang S. The regulation of inflammation by oxidized phospholipids. Eur J Immunol. 2016;46(8):1818-1825.

81. Ravandi A, Boekholdt SM, Mallat Z, et al. Relationship of oxidized LDL with markers of oxidation and inflammation and cardiovascular events: results from the EPIC-Norfolk Study. J Lipid Res. 2011;52(10):1829-1836.

82. Tsimikas S, Willeit P, Willeit J, et al. Oxidation-specific biomarkers, prospective 15-year cardiovascular and stroke outcomes, and net reclassification of cardiovascular events. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60(21):2218-2229.

83. Cinoku I, Mavragani CP, Tellis CC, Nezos A, Tselepis AD, Moutsopoulos HM. Autoantibodies to ox-LDL in Sjogren’s syndrome: are they atheroprotective? Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2018;36 Suppl 112(3):61-67.

84. Fagerberg B, Prahl Gullberg U, Alm R, Nilsson J, Fredrikson GN. Circulating autoantibodies against the apolipoprotein B-100 peptides p45 and p210 in relation to the occurrence of carotid plaques in 64-year-old women. PLoS One. 2015;10(3):e0120744.

85. Klesareva EA, Afanas’eva OI, Donskikh VV, Adamova IY, Pokrovskii SN. Characteristics of lipoprotein(a)-containing circulating immune complexes as markers of coronary heart disease. Bull Exp Biol Med. 2016;162(2):231-236.

86. Morishita R, Ishii J, Kusumi Y, et al. Association of serum oxidized lipoprotein(a) concentration with coronary artery disease: potential role of oxidized lipoprotein(a) in the vasucular wall. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2009;16(4):410-418.

87. Wang J, Zhang C, Gong J, et al. Development of new enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for oxidized lipoprotein(a) by using purified human oxidized lipoprotein(a) autoantibodies as capture antibody. Clin Chim Acta. 2007;385(1-2):73-78.

88. Wang JJ, Han AZ, Meng Y, et al. Measurement of oxidized lipoprotein (a) in patients with acute coronary syndromes and stable coronary artery disease by 2 ELISAs: using different capture antibody against oxidized lipoprotein (a) or oxidized LDL. Clin Biochem. 2010;43(6):571-575.

89. Orso E, Schmitz G. Lipoprotein(a) and its role in inflammation, atherosclerosis and malignancies. Clin Res Cardiol Suppl. 2017;12(Suppl 1):31-37.

90. Lassman ME, McLaughlin TM, Zhou H, et al. Simultaneous quantitation and size characterization of apolipoprotein(a) by ultra-performance liquid chromatography/ mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2014;28(10):1101-1106.

91. Lippi G, Guidi G. Lipoprotein(a): from ancestral benefit to modern pathogen? QJM. 2000;93(2):75-84.

92. van der Valk FM, Bekkering S, Kroon J, et al. Oxidized phospholipids on lipoprotein(a) elicit arterial wall inflammation and an inflammatory monocyte response in humans. Circulation. 2016;134(8):611-624.

93. Yeang C, Wilkinson MJ, Tsimikas S. Lipoprotein(a) and oxidized phospholipids in calcific aortic valve stenosis. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2016;31(4):440-450.

94. Thanassoulis G, Campbell CY, Owens DS, et al; CHARGE Extracoronary Calcium Working Group. Genetic associations with valvular calcification and aortic stenosis. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(6):503-512.

95. Aguib Y, Al Suwaidi J. The Copenhagen City Heart Study (Osterbroundersogelsen). Glob Cardiol Sci Pract. 2015;2015(3):33.

96. Kamstrup PR, Benn M, Tybjaerg-Hansen A, Nordestgaard BG. Extreme lipoprotein(a) levels and risk of myocardial infarction in the general population: the Copenhagen City Heart Study. Circulation. 2008;117(2):176-184.

97. Kamstrup PR, Tybjærg-Hansen A, Steffensen R, Nordestgaard BG. Genetically elevated lipoprotein(a) and increased risk of myocardial infarction. JAMA. 2009;301(22):2331-2339.

98. Kamstrup PR, Tybjaerg-Hansen A, Nordestgaard BG. Extreme lipoprotein(a) levels and improved cardiovascular risk prediction. J Am Coll Cardiol.2013;61(11):1146-1156.

99. Kamstrup PR, Tybjaerg-Hansen A, Nordestgaard BG. Elevated lipoprotein(a) and risk of aortic valve stenosis in the general population. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(5):470-477.

100. Kamstrup PR, Nordestgaard BG. Elevated lipoprotein(a) levels, LPA risk genotypes, and increased risk of heart failure in the general population. JACC Heart Fail.2016;4(1):78-87.

101. Verbeek R, Hoogeveen RM, Langsted A, et al. Cardiovascular disease risk associated with elevated lipoprotein(a) attenuates at low low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels in a primary prevention setting. Eur Heart J. 2018;39(27):2589-2596.

102. Cao J, Steffen BT, Budoff M, et al. Lipoprotein(a) levels are associated with subclinical calcific aortic valve disease in white and black individuals: the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2016;36(5):1003-1009.

103. Steffen BT, Duprez D, Bertoni AG, Guan W, Tsai M. Lp(a) [lipoprotein(a)]-related risk of heart failure is evident in whites but not in other racial/ethnic groups.Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2018;38(10):2498-2504.

104. ARIC Investigators. The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study: design and objectives. Am J Epidemiol. 1989;129(4):687-702.

105. Agarwala A, Pokharel Y, Saeed A, et al. The association of lipoprotein(a) with incident heart failure hospitalization: Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study. Atherosclerosis. 2017;262:131-137.

106. Ohira T, Schreiner PJ, Morrisett JD, Chambless LE, Rosamond WD, Folsom AR. Lipoprotein(a) and incident ischemic stroke: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study. Stroke. 2006;37(6):1407-1412.

107. Waldeyer C, Makarova N, Zeller T, et al. Lipoprotein(a) and the risk of cardiovascular disease in the European population: results from the BiomarCaRE consortium. Eur Heart J. 2017;38(32):2490-2498.

108. Cook NR, Mora S, Ridker PM. Lipoprotein(a) and cardiovascular risk prediction among women. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72(3):287-296.

109. Suk Danik J, Rifai N, Buring JE, Ridker PM. Lipoprotein(a), measured with an assay independent of apolipoprotein(a) isoform size, and risk of future cardiovascular events among initially healthy women. JAMA. 2006;296(11):1363-1370.

110. Suk Danik J, Rifai N, Buring JE, Ridker PM. Lipoprotein(a), hormone replacement therapy, and risk of future cardiovascular events. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52(2):124-131.

111. Chien KL, Hsu HC, Su TC, Sung FC, Chen MF, Lee YT. Lipoprotein(a) and cardiovascular disease in ethnic Chinese: the Chin-Shan Community Cardiovascular Cohort Study. Clin Chem. 2008;54(2):285-291.

112. Lee SR, Prasad A, Choi YS, et al. LPA gene, ethnicity, and cardiovascular events. Circulation.2017;135(3):251-263.

113. Zekavat SM, Ruotsalainen S, Handsaker RE, et al. Deep coverage whole genome sequences and plasma lipoprotein(a) in individuals of European and African ancestries. Nat Commun.2018;9(1):2606.

114. Zewinger S, Kleber ME, Tragante V, et al. Relations between lipoprotein(a) concentrations, LPA genetic variants, and the risk of mortality in patients with established coronary heart disease: a molecular and genetic association study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017;5(7):534-543.

115. Li J, Lange LA, Sabourin J, et al. Genome- and exomewide association study of serum lipoprotein (a) in the Jackson Heart Study. J Hum Genet. 2015;60(12):755-761.

116. Khera AV, Emdin CA, Drake I, et al, Kathiresan S. Genetic risk, adherence to a healthy lifestyle, and coronary disease. N Engl J Med.2016;375(24):2349-2358.

117. Nordestgaard BG, Langsted A. Lipoprotein(a) as a cause of cardiovascular disease: insights from epidemiology, genetics, and biology. J Lipid Res.2016;57(11):1953-1975.

118. Sofi F, Cesari F, Casini A, Macchi C, Abbate R, Gensini GF. Insomnia and risk of cardiovascular disease: a metaanalysis. Eur J Prev Cardiol.2014;21(1):57-64.

119. Estruch R, Ros E, Salas-Salvado J, et al. Primary prevention of cardiovascular disease with a mediterranean diet supplemented with extra-virgin olive oil or nuts. N Engl J Med.2018;378(25):e34.

120. Perrot N, Verbeek R, Sandhu M, et al. Ideal cardiovascular health influences cardiovascular disease risk associated with high lipoprotein(a) levels and genotype: The EPICNorfolk prospective population study. Atherosclerosis. 2017;256:47-52.

121. Teo KK, Corsi DJ, Tam JW, Dumesnil JG, Chan KL. Lipid lowering on progression of mild to moderate aortic stenosis: meta-analysis of the randomized placebocontrolled clinical trials on 2344 patients. Can J Cardiol. 2011;27(6):800-808.

122. Albers JJ, Slee A, O’Brien KD, et al. Relationship of apolipoproteins A-1 and B, and lipoprotein(a) to cardiovascular outcomes: the AIM-HIGH trial (Atherothrombosis Intervention in Metabolic Syndrome with Low HDL/High Triglyceride and Impact on Global Health Outcomes). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62(17):1575-1579.

123. Lincoff AM, Nicholls SJ, Riesmeyer JS, et al; ACCELERATE Investigators. Evacetrapib and cardiovascular outcomes in high-risk vascular disease. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(20):1933-1942.

124. Schmidt AF, Pearce LS, Wilkins JT, Overington JP, Hingorani AD, Casas JP. PCSK9 monoclonal antibodies for the primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev.2017;4:CD011748.

125. Bowman L, Hopewell JC, Chen F, et al; PHS3/TIM155-REVEAL Collaborative Group. Effects of anacetrapib in patients with atherosclerotic vascular disease.

126. Leebmann J, Roeseler E, Julius U, et al; Pro(a)LiFe Study Group. Lipoprotein apheresis in patients with maximally tolerated lipid-lowering therapy, lipoprotein(a)-hyperlipoproteinemia, and progressive cardiovascular disease: prospective observational multicenter study. Circulation. 2013;128(24):2567-2576.

127. Heigl F, Hettich R, Lotz N, et al. Efficacy, safety, and tolerability of long-term lipoprotein apheresis in patients with LDL- or Lp(a) hyperlipoproteinemia: Findings gathered from more than 36,000 treatments at one center in Germany. Atheroscler Suppl. 2015;18:154-162.

128. Viney NJ, van Capelleveen JC, Geary RS, et al. Antisense oligonucleotides targeting apolipoprotein(a) in people with raised lipoprotein(a): two randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging trials. Lancet. 2016;388(10057):2239-2253.

129. Graham MJ, Viney N, Crooke RM, Tsimikas S. Antisense inhibition of apolipoprotein (a) to lower plasma lipoprotein (a) levels in humans. J Lipid Res. 2016;57(3):340-351.

130. Keene D, Price C, Shun-Shin MJ, Francis DP. Effect on cardiovascular risk of high density lipoprotein targeted drug treatments niacin, fibrates, and CETP inhibitors: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials including 117,411 patients. BMJ. 2014;349:g4379.

131. Nicholls SJ, Ruotolo G, Brewer HB, et al. Evacetrapib alone or in combination with statins lowers lipoprotein(a) and total and small LDL particle concentrations in mildly hypercholesterolemic patients. J Clin Lipidol. 2016;10(3):519-527.e4.

132. Schwartz GG, Ballantyne CM, Barter PJ, et al. Association of lipoprotein(a) with risk of recurrent ischemic events following acute coronary syndrome: analysis of the dal-outcomes randomized clinical trial. JAMA Cardiol.2018;3(2):164-168.

133. Schwartz GG, Olsson AG, Abt M, et al; dal-OUTCOMES Investigators. Effects of dalcetrapib in patients with a recent acute coronary syndrome. N Engl J Med.2012;367(22):2089-2099.

134. Thomas T, Zhou H, Karmally W, et al. CETP (Cholesteryl Ester Transfer Protein) inhibition with anacetrapib decreases production of lipoprotein(a) in mildly hypercholesterolemic subjects. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol.2017;37(9):1770-1775.

135. Khera AV, Everett BM, Caulfield MP, et al. Lipoprotein(a) concentrations, rosuvastatin therapy, and residual vascular risk: an analysis from the JUPITER Trial (Justification for the Use of Statins in Prevention: an Intervention Trial Evaluating Rosuvastatin). Circulation. 2014;129(6):635-642.

136. Yeang C, Hung MY, Byun YS, et al. Effect of therapeutic interventions on oxidized phospholipids on apolipoprotein B100 and lipoprotein(a). J Clin Lipidol. 2016;10(3):594-603.

137. Zhou Z, Rahme E, Pilote L. Are statins created equal? Evidence from randomized trials of pravastatin, simvastatin, and atorvastatin for cardiovascular disease prevention.Am Heart J. 2006;151(2):273-281.

138. Ridker PM, MacFadyen JG, Fonseca FA, et al; JUPITER Study Group. Number needed to treat with rosuvastatin to prevent first cardiovascular events and death among men and women with low low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and elevated high-sensitivity C-reactive protein: justification for the use of statins in prevention: an intervention trial evaluating rosuvastatin (JUPITER). Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2009;2(6):616-623.

139. Raal FJ, Giugliano RP, Sabatine MS, et al. Reduction in lipoprotein(a) with PCSK9 monoclonal antibody evolocumab (AMG 145): a pooled analysis of more than 1,300 patients in 4 phase II trials. J Am Coll Cardiol.2014;63(13):1278-1288.

140. Sabatine MS, Giugliano RP, Wiviott SD, et al. Efficacy and safety of evolocumab in reducing lipids and cardiovascular events. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(16):1500-1509.

141. Koren MJ, Sabatine MS, Giugliano RP, et al. Long-term low-density lipoprotein cholesterol-lowering efficacy, persistence, and safety of evolocumab in treatment of hypercholesterolemia: results up to 4 years from the open-label OSLER-1 extension study. JAMA Cardiol.2017;2(6):598-607.

142. Desai NR, Kohli P, Giugliano RP, et al. AMG145, a monoclonal antibody against proprotein convertase subtilisin kexin type 9, significantly reduces lipoprotein(a) in hypercholesterolemic patients receiving statin therapy: an analysis from the LDL-C Assessment with Proprotein Convertase Subtilisin Kexin Type 9 Monoclonal Antibody Inhibition Combined with Statin Therapy (LAPLACE)-Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) 57 trial. Circulation.2013;128(9):962-969.

143. Schwartz GG, Steg PG, Szarek M, et al; ODYSSEY OUTCOMES Committees and Investigators. Alirocumab and cardiovascular outcomes after acute coronary syndrome.N Engl J Med. 2018;379(22):2097-2107.

144. Sabatine MS, Giugliano RP, Keech AC, et al; FOURIER Steering Committee and Investigators. Evolocumab and clinical outcomes in patients with cardiovascular Disease.N Engl J Med. 2017;376(18):1713-1722.

145. Karatasakis A, Danek BA, Karacsonyi J, et al. Effect of PCSK9 inhibitors on clinical outcomes in patients with hypercholesterolemia: A meta-analysis of 35 randomized controlled trials. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6(12):e006910.

146. Santos RD, Duell PB, East C, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of mipomersen in patients with familial hypercholesterolaemia: 2-year interim results of an open-label extension.Eur Heart J. 2015;36(9):566-575.

147. Duell PB, Santos RD, Kirwan BA, Witztum JL, Tsimikas S, Kastelein JJP. Long-term mipomersen treatment is associated with a reduction in cardiovascular events in patients with familial hypercholesterolemia. J Clin Lipidol. 2016;10(4):1011-1021.

148. McGowan MP, Tardif JC, Ceska R, et al. Randomized, placebo-controlled trial of mipomersen in patients with severe hypercholesterolemia receiving maximally tolerated lipid-lowering therapy. PLoS One.2012;7(11):e49006.

149. Jaeger BR, Richter Y, Nagel D, et al. Longitudinal cohort study on the effectiveness of lipid apheresis treatment to reduce high lipoprotein(a) levels and prevent major adverse coronary events. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med.2009;6(3):229-239.

150. Rosada A, Kassner U, Vogt A, Willhauck M, Parhofer K, Steinhagen-Thiessen E. Does regular lipid apheresis in Does regular lipid apheresis in patients with isolated elevated lipoprotein(a) levels reduce the incidence of cardiovascular events? Artif Organs. 2014;38(2):135-141.

151. Arnett DK, Blumenthal RS, Albert MA, et al. 2019 ACC/AHA Guideline on the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2019;140(11):e596-e646.

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) remains the leading cause of global mortality. In 2015, 41.5% of the US population had at least 1 form of CVD and CVD accounted for nearly 18 million deaths worldwide.1,2 The major disease categories represented include myocardial infarction (MI), sudden death, strokes, calcific aortic valve stenosis (CAVS), and peripheral vascular disease.1,2 In terms of health care costs, quality of life, and caregiver burden, the overall impact of disease prevalence continues to rise.1,3-6 There is an urgent need for more precise and earlier CVD risk assessment to guide lifestyle and therapeutic interventions for prevention of disease progression as well as potential reversal of preclinical disease. Even at a young age, visible coronary atherosclerosis has been found in up to 11% of “healthy” active individuals during autopsies for trauma fatalities.7,8

The impact of CVD on the US and global populations is profound. In 2011, CVD prevalence was predicted to reach 40% by 2030.9 That estimate was exceeded in 2015, and it is now predicted that by 2035, 45% of the US population will suffer from some form of clinical or preclinical CVD. In 2015, the decadeslong decline in CVD mortality was reversed for the first time since 1969, showing a 1% increase in deaths from CVD.1 Nearly 300,000 of those using US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) services were hospitalized for CVD between 2010 and 2014.10 The annual direct and indirect costs related to CVD in the US are estimated at $329.7 billion, and these costs are predicted to top $1 trillion by 2035.1 Heart attack, coronary atherosclerosis, and stroke accounted for 3 of the 10 most expensive conditions treated in US hospitals in 2013.11 Globally, the estimate for CVD-related direct and indirect costs was $863 billion in 2010 and may exceed $1 trillion by 2030.12

The nature of military service adds additional risk factors, such as posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, sleep disorders and physical trauma which increase CVD morbidity/ mortality in service members, veterans, and their families.13-16 In addition, living in lowerincome areas (countries or neighborhoods) can increase the risk of both CVD incidence and fatalities, particularly in younger individuals.17-20 The Military Health System (MHS) and VA are responsible for the care of those individuals who have voluntarily taken on these additional risks through their time in service. This responsibility calls for rapid translation to practice tools and resources that can support interventions to minimize as many modifiable risk factors as possible and improve longterm health. This strategy aligns with the World Health Organization’s (WHO) focus on prevention of disease progression through interventions targeting modifiable risk.3-6,21-23 The driving force behind the launch of the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Million Hearts program was the goal of preventing 1 million heart attacks and strokes by 2017 with risk reduction through aspirin, blood pressure control, cholesterol management, smoking cessation, sodium reduction, and physical activity.24,25 While some reductions in CVD events have been documented, the outcomes fell short of the goals set, highlighting both the need and value of continued and expanded efforts for CVD risk reduction.26

More precise assessment of risk factors during preventative care, as well as after a diagnosis of CVD, may improve the timeliness and precision of earlier interventions (both lifestyle and therapeutic) that reduce CVD morbidity and mortality.27 Personalized or precision medicine approaches take into account differences in socioeconomic, environmental, and lifestyle factors that are potentially reversible, as well as gender, race, and ethnicity.28-31 Current methods of predicting CVD risk have considerable room for improvement.27 About 40% of patients with newly diagnosed CVD have normal traditional cholesterol profiles, including those whose first cardiac event proves fatal.29-33 Currently available risk scores (hundreds have been described in the literature) mischaracterize risk in minority populations and women, and have shown deficiencies in identifying preclinical atherosclerosis.34,35 The failure to recognize preclinical CVD in military personnel during their active duty life cycle results in missed opportunities for improved health and readiness sustainment.

Most CVD risk prediction models incorporate some form of blood lipids. Total cholesterol (TC) is most commonly used in clinical practice, along with high-density lipoprotein (HDLC), low-density lipoprotein (LDLC), and triglycerides (TG).23,27,36 High LDLC and/or TC are well established as lipid-related CVD risk factors and are incorporated into many CVD risk scoring systems/models described in the literature.27 LDLC reduction is commonly recommended as CVD prevention, but even with optimal statin treatment, there is still considerable residual risk for new and recurrent CVD events.28,32,34,35,37-42

Incorporating novel biomarkers and alternative lipid measurements may improve risk prediction and aid targeted treatment, ultimately reducing CVD events.27 Apolipoprotein B (ApoB) is a major atherogenic component embedded in LDL and VLDL correlating to non-HDLC and may be useful in the setting of triglycerides ≥ 200 mg/d as levels > 130 mg/ dL appear to be risk-enhancing, but measurements may be unreliable.43 According to the 2018 Cholesterol Guidelines, lipoprotein(a) [Lp(a)] elevation also is recognized as a risk-enhancing factor that is particularly implicated when there is a strong family history of premature atherosclerotic CVD or personal history of CVD not explained by major risk factors.43

Lp(a) elevation is a largely underrecognized category of lipid disorder that impacts up to 20% to 30% of the population globally and within the US, although there is considerable variability by geographic location and ethnicity.44 Globally, Lp(a) elevation places > 1 billion people at moderate to high risk for CVD.44 Lp(a) has a strong genetic component and is recognized as a distinct and independent risk factor for MI, sudden death, strokes and CAVS. Lp(a) has an extensive body of evidence to support its distinct role both as a causal factor in CVD and as an augmentation to traditional risk factors.44-48

Lipoproteni(a) Elevation Use For Diagnosis

The importance of Lp(a) elevation as a clinical diagnosis rather than a laboratory abnormality alone was brought forward by the Lipoprotein(a) Foundation. Its founder, Sandra Tremulis, is a survivor of an acute coronary event that occurred when she was 39-years old, despite running marathons and having none of the traditional CVD lifestyle risk factors.49 This experience inspired her to create the Lipoprotein(a) Foundation to give a voice to families living with or at risk for CVD due to Lp(a) elevation.

As often happens in the progress of medicine, patients and their families drive change based on their personal experiences with the gaps in standard clinical practice. It was this foundation—not a member of the medical establishment—that submitted the formal request for the addition of new ICD-10-CM diagnostic and family history codes for Lp(a) elevation during the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) September 2017 ICD-10-CM Coordination and Maintenance Committee meeting.50 In June 2018, the final ICD-10-CM code addenda for 2019 was released and included the new codes E78.41 (Elevated Lp[a]) and Z83.430 (Family history of elevated Lp[a]).52 After the new codes were approved, both the American Heart Association and the National Lipid Association added recommendations regarding Lp(a) testing to their clinical practice guidelines.43,52

Practically, these codes standardize billing and payment for legitimate clinical work and laboratory testing. Prior to the addition of Lp(a) elevation as a clinical diagnosis, testing and treatment of Lp(a) elevation was considered experimental and not medically necessary until after a cardiovascular event had already occurred. Services for Lp(a) elevation were therefore not reimbursed by many healthcare organizations and insurance companies. The new ICD-10-CM codes encourage the assessment of Lp(a) both in individuals with early onset major CVD events and in presumably fit, healthy individuals, particularly when there is a family history of Lp(a) elevation. Given that Lp(a) levels do not change significantly over time, the current understanding is that only a single measurement is needed to define the individual risk over a lifetime.41,42,44,45 As therapies targeting Lp(a) levels evolve, repeated measurements may be indicated to monitor response and direct changes in management. “Elevated Lipoprotein(a)” is the first laboratory testing abnormality that has achieved the status of a clinical diagnosis.

Lp(a) Measurements

There is considerable complexity to the measurement of lipoproteins in blood samples due to heterogeneity in both density and size of particles as illustrated in the Figure.53

For traditional lipids measured in clinical practice, the size and density ranges from small high-density lipoprotein (HDL) through LDLC and intermediate- density lipoprotein (IDL) to the largest least dense particles in the very low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) and chylomicron remnant fractions. Standard lipid profiles consist of mass concentration measurements (mg/dL) of TC, TG, HDLC, and LDLC.53 Non-HDLC (calculated as: TC−HDLC) consists of all cholesterol found in atherogenic lipoproteins, including remnant-C and Lp(a). Until recently, the cholesterol content of Lp(a), corresponding to about 30% of Lp(a) total mass, was included in the TC, non-HDLC and LDLC measurements with no separate reporting by the majority of clinical laboratories.

After > 50 years of research on the structure and biochemistry of Lp(a), the physiology and biological functions of these complex and polymorphic lipoprotein particles are not fully understood. Lp(a) is composed of a lipoprotein particle similar in composition to LDL (protein and lipid), containing 1 molecule of ApoB wrapped around a core of cholesteryl ester and triglyceride with phospholipids and unesterified cholesterol at its surface.48 The presence of a unique hydrophilic, highly glycosylated protein referred to as apolopoprotienA (apo[a]), covalently attached to ApoB-100 by a single disulfide bridge, differentiates Lp(a) from LDL.48 Cholesterol rich ApoB is an important component within many lipoproteins pathogenic for atherosclerosis and CVD.45,47,53

The apo(a) contributes to the increased density of Lp(a) compared to LDLC with associated reduced binding affinity to the LDL receptor. This reduced receptor binding affinity is a presumed mechanism for the lack of Lp(a) plasma level response to statin therapies, which increase hepatic LDL receptor activity.47 Apo(a) evolved from the plasminogen gene through duplication and remodeling and demonstrates extensive heterogeneity in protein size, with > 40 different apo(a) isoforms resulting in > 40 different Lp(a) particle sizes. Size of the apo(a) particle is determined by the number of pleated structures known as kringles. Most people (> 80%) carry 2 different-sized apo(a) isoforms. Plasma Lp(a) level is determined by the net production of apo(a) in each isoform, and the smaller apo(a) isoforms are associated with higher plasma levels of Lp(a).45

Given the heterogeneity in Lp(a) molecular weight, which can vary even within individuals, recommendations have been made for reporting results as particle numbers or concentrations (nmol/L or mmol/L) rather than as mass concentration (mg/dL).55 However, the majority of the large CVD morbidity and mortality outcomes studies used Lp(a) mass concentration levels in mg/ dL to characterize risk levels.56,57 There is no standardized method to convert Lp(a) measurements from mg/dL to nmol/L.55 Current assays using WHO standardized reagents and controls are reliable for categorizing risk levels.58

The European Atherosclerosis Society consensus panel recommended that desirable Lp(a) levels should be below the 80th percentile (< 50 mg/dL or < 125 nmol/L) in patients with intermediate or high CVD risk.59 Subsequent epidemiological and Mendelian randomization studies have been performed in general populations with no history of CVD and demonstrated that increased CVD risk can be detected with Lp(a) levels as low as 25 to 30 mg/dL.56,60-63 In secondary prevention populations with prior CVD and optimal treatment (statins, antiplatelet drugs), recurrent event risk was also increased with elevated Lp(a).63-66

Using immunoturbidometric assays, Varvel and colleagues reported the prevalence of elevated Lp(a) mass concentration levels (mg/dL) in > 500,000 US patients undergoing clinical evaluations based on data from a referral laboratory of patients.58 The mean Lp(a) levels were 34.0 mg/dL with median (interquartile range [IQR]) levels at 17 (7-47) mg/dL and overall range of 0 to 907 mg/dL.58 Females had higher Lp(a) levels compared to males but no ethnic or racial breakdown was provided. Lp(a) levels > 30 mg/dL and > 50 mg/dL were present in 35% and 24% of subjects, respectively. Table 1 displays the relationship between various Lp(a) level cut-offs to mean levels of LDLC, estimated LDLC corrected for Lp(a), TC, HDLC, and TG.58 The data demonstrate that Lp(a) elevation cannot be inferred from LDLC levels nor from any of the other traditional lipoprotein measures. Patients with high risk Lp(a) levels may have normal LDLC. While Lp(a) thresholds have been identified for stratification of CVD risk, the target levels for risk reduction have not been specifically defined, particularly since therapies are not widely available for reduction of Lp(a). Table 2 provides an overview of clinical lipoprotein measurements that may be reasonable targets for therapeutic interventions and reduction of CVD risk.44,53,55 In general, existing studies suggest that radical reduction (> 80%) is required to impact long-term outcomes, particularly in individuals with severe disease.68,69

LDLC reduction alone leaves a residual CVD risk that is greater than the risk reduced.40 In addition, the autoimmune inflammation and lipid specific autoantibodies play an important role in increased CVD morbidity and mortality risk.70,71 The presence of autoantibodies such as antiphospholipid antibodies (without a specific autoimmune disease diagnosis) increases the risk of subclinical atherosclerosis.72,73 Certain autoimmune diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus are recognized as independent risk factors for CVD.74,75 Autoantibodies appear to mediate CVD events and mortality risk, independent of traditional therapies for risk reduction.73 Further research is needed to clarify the role of autoantibodies as markers of increased or decreased CVD risk and their mechanism of action.

Autoantibodies directed at new antigens in lipoproteins within atherosclerotic lesions can modulate the impact of atherosclerosis via activation of the innate and adaptive immune system.76 The lipid-associated neopeptides are recognized as damage-associated or danger- associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), also known as alarmins, which signal molecules that can trigger and perpetuate noninfectious inflammatory responses.77-79 Plasma autoantibodies (immunoglobulin M and G [IgM, IgG]) modify proinflammatory oxidation-specific epitopes on oxidized phospholipids (oxPL) within lipoproteins and are linked with markers of inflammation and CVD events.80-82 Modified LDLC and ApoB-100 immune complexes with specific autoantibodies in the IgG class are associated with increased CVD.76 These and other risk-modulating autoantibodies may explain some of the variability in CVD outcomes by ethnicity and between individuals.

Some antibodies to oxidized LDL (ox-LDL) may have a protective role in the development of atherosclerosis.83,84 In a cohort of > 500 women, the number of carotid atherosclerotic plaques and total carotid plaque area were inversely correlated with a specific IgM autoantibody (MDA-p210).84 High concentrations of Lp(a)- containing circulating immune complexes and Lp(a)-specific IgM and IgG have been described in patients with coronary heart disease (CHD).85 Like ox-LDL, oxidized Lp(a) [ox-Lp(a)] is more potent than native Lp(a) in increasing atherosclerosis risk and is increased in patients with CHD compared to healthy controls.86-88 Ox-Lp(a) levels may represent an even stronger risk marker for CVD than ox-LDL.85

Possible Mechanisms of Pathogenesis

While the precise quantification of Lp(a) in human plasma (or serum) has been challenging, current clinical laboratories use standardized international reference reagents and controls in their assays. Most current Lp(a) assays are based on immunological methods (eg, immunonephelometry, immunoturbidimetry, or enzyme linked immunosorbent assay [ELISA]) using antibodies against apo(a).89 Apo(a) contains 10 subtypes of kringle IV and 1 copy of kringle V. Some assays use antibodies against kringle-IV type 2; however, it has been recommended that newer methods should use antibodies against the specific bridging kringle-IV Type 9 domain, which has a more stable bond and is present as a single copy.48,89 Other approaches to Lp(a) measurement include ultraperformance liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry that can determine both the concentration and particle size of apo(a).48,90 For routine clinical care, currently available assays reporting in mg/dL can be considered fairly accurate for separating low-risk from moderate-to-high-risk patients.45

The physiologic role of Lp(a) in humans remains to be fully defined and individuals with extremely low plasma Lp(a) levels present no disease or deficiency syndromes.91 Lp(a) accumulates in endothelial injuries and binds to components of the vessel wall and subendothelial matrix, presumably due to the strong lysine binding site in apo(a).46 Mediated by apo(a), the binding stimulates chemotactic activation of monocytes/macrophages and thereby modulating angiogenesis and inflammation.89 Lp(a) may contribute to CVD and CAVS via its LDL-like component, with proinflammatory effects of oxidized phospholipids (OxPL) on both ApoB and apo(a) and antifibrinolytic/prothrombotic effects of apo(a).92 In Vitro studies have demonstrated that apo(a) modifies cellular function of cultured vascular endothelial cells (promoting stress fiber formation, endothelial contraction and vascular permeability), smooth muscles, and monocytes/ macrophages (promoting differentiation of proinflammatory M1-1 type macrophages) via complex mechanisms of cell signaling and cytokine production.89 Lp(a) is the only monogenetic risk factor for aortic valve calcification and stenosis93 and is strongly linked specifically with the single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) rs10455872 in the gene LPA encoding for apo(a).94

CVD Risk Predictive Value