User login

Ill-Defined Macule on the Abdomen

The Diagnosis: Microvenular Hemangioma

Microvenular hemangioma is an acquired benign vascular neoplasm that was described by Hunt et al1 in 1991, though Bantel et al2 reported a similar entity termed micropapillary angioma in 1989. Microvenular hemangioma typically presents as a solitary, slowly enlarging, red to violaceous, asymptomatic papule, plaque, or nodule measuring 5 to 20 mm in diameter. It usually is located on the trunk, arms, or legs of young adults without any gender predilection. Microvenular hemangioma is rare.3 The etiology has not been elucidated, though a relationship with hormonal factors such as pregnancy or hormonal contraceptives has been described.2

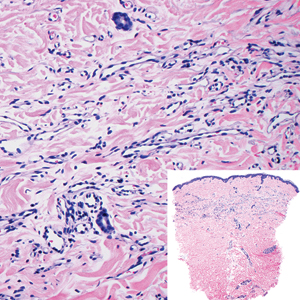

Histopathologically, microvenular hemangioma has a characteristic morphology. It is comprised of a well-circumscribed collection of thin-walled blood vessels with narrow lumens (quiz image).4 The blood vessels tend to infiltrate the superficial and deep dermis and are surrounded by a collagenous or desmoplastic stroma. The endothelial cells are normal in size without atypia, mitotic figures, or pleomorphism. A mild lymphoplasmacytic inflammatory infiltrate sometimes is present. Microvenular hemangioma expresses many vascular markers confirming its endothelial origin, including CD34, CD31, WT1, factor VIII-related antigen, and von Willebrand factor.3 Moreover, WT1 staining suggests the lesion is a vascular proliferative growth, as it usually is negative in vascular malformations due to errors of endothelial development.5 In addition, it lacks expression of podoplanin (D2-40), which also supports a vascular as opposed to a lymphatic origin.4

Cutaneous angiosarcoma is a rare and highly aggressive malignant neoplasm of the vascular endothelium with a predilection for the skin and superficial soft tissue. Clinical presentation is variable, as it can arise sporadically, commonly on the scalp and face of elderly patients, in areas of chronic radiation therapy, or in association with chronic lymphedema (Stewart-Treves syndrome).6 Sporadic neoplasms appear clinically as purpuric macules, plaques, or nodules and are more common in elderly men than women. They are aggressive tumors that tend to recur and metastasize despite aggressive therapy and therefore carry a poor prognosis.7 Histopathologically, well-differentiated tumors are characterized by irregular dissecting vessels lined with crowded inconspicuous endothelial cells (Figure 1). Cutaneous angiosarcoma is poorly circumscribed with marked cytologic atypia, and the vessels can take on a sinusoidal growth pattern.8

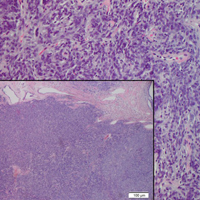

Kaposi sarcoma (KS) is a virally induced lymphoangioproliferative disease, with human herpesvirus 8 as the implicated agent. There are 4 principal clinical variants of KS: epidemic or AIDS-associated KS, endemic or African KS, KS due to iatrogenic immunosuppression, and Mediterranean or classic KS.9 Cutaneous lesions vary from pink patches to dark purple plaques or nodules that commonly occur on the lower legs10; however, the clinical appearance of KS varies depending on the clinical variant and stage. Histopathologically, early lesions of KS exhibit a superficial dermal proliferation of small angulated and jagged vessels that tend to separate into collagen bundles and are surrounded by a lymphoplasmacytic perivascular infiltrate. These native vascular structures often are surrounded by more ectatic neoplastic channels with plump endothelial cells, known as the promontory sign (Figure 2).11 With more advanced lesions, the proliferation of slitlike vessels becomes more cellular and extends deeper into the dermis and subcutis. Although the histopathologic features vary with the stage of the lesion, they do not notably vary between clinical subtypes.

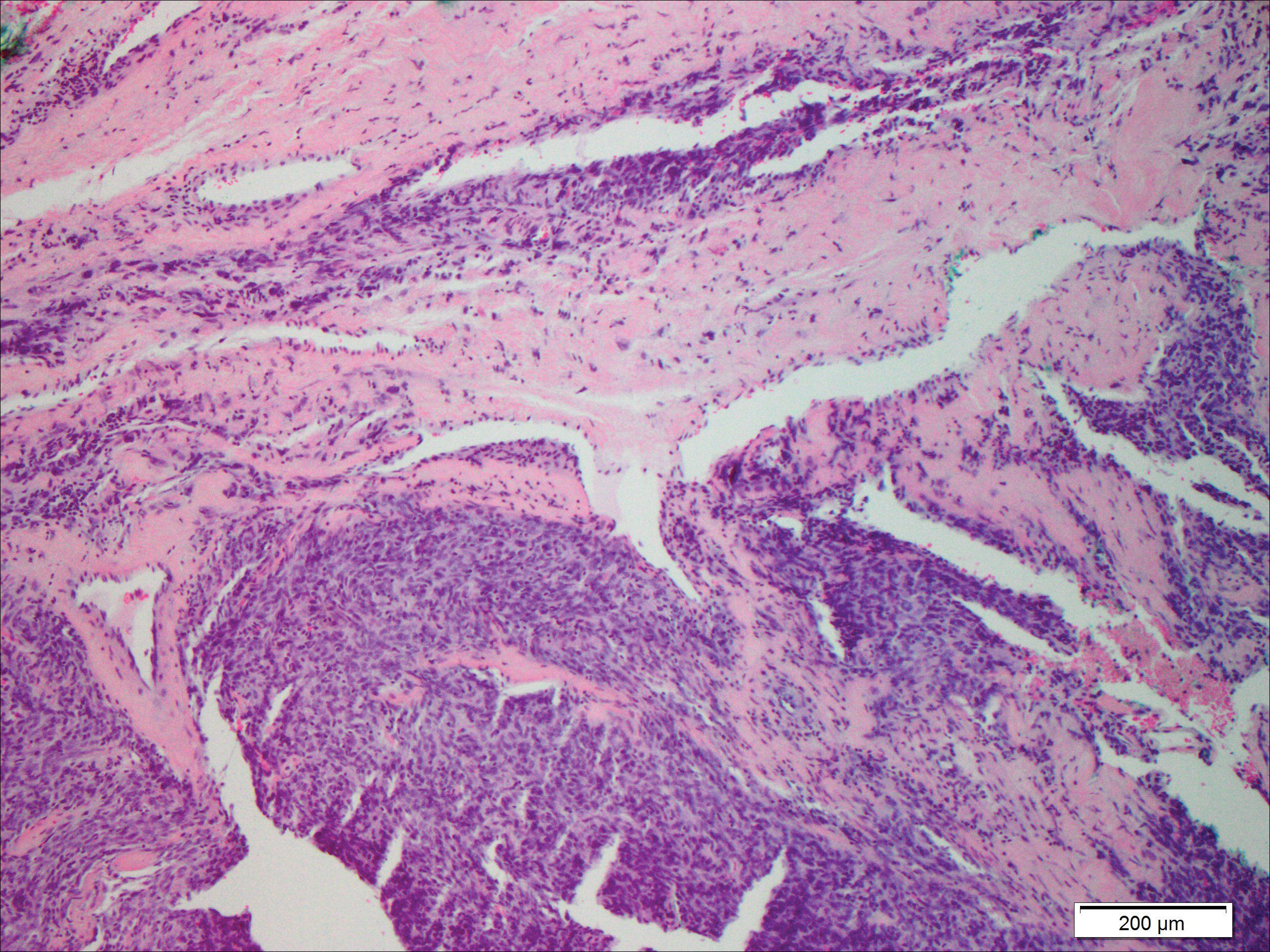

Targetoid hemosiderotic hemangioma, also known as hobnail hemangioma, is a small, benign, vascular tumor that usually affects the trunk, arms, and legs in young to middle-aged adults without a gender predilection. Clinically, it appears as a small, solitary, red to purple papule or macule that typically is surrounded by a pale thin area and a peripheral ecchymotic ring, creating a targetoid appearance, thus the term targetoid hemosiderotic hemangioma.12 Histopathologically, there is a prominent dermal vascular proliferation. In the papillary dermis, there are dilated superficial vessels lined with a single layer of endothelial cells characterized by a plump, hobnail-like appearance that protrude into the lumen (Figure 3). In the deeper dermis, the vascular spaces are angulated and slitlike and appear to dissect through collagen bundles. Hemosiderin, thrombi, extravasated erythrocytes, and a lymphocytic infiltrate also are often seen.13

Tufted angioma is a rare benign vascular lesion that usually presents as an acquired lesion in children and young adults, though it may be congenital. It is commonly localized to the skin and subcutaneous tissues. Clinically, the lesions appear as red to purple patches and plaques that typically are located on the neck or trunk. More than 50% of cases present during the first year of life and slowly spread to involve large areas before stabilizing in size.14 Partial spontaneous regression may occur, but complete regression is rare.15 Lesions usually are asymptomatic but may be painful during periods of platelet trapping (Kasabach-Merritt phenomenon), which may develop in congenital cases. Tufted angioma is named for its characteristic histopathologic appearance, which consists of multiple discrete lobules or tufts of tightly packed capillaries in a cannonball-like appearance throughout the dermis and subcutis (Figure 4).14,15

- Hunt SJ, Santa Cruz DJ, Barr RJ. Microvenular hemangioma. J Cutan Pathol. 1991;18:235-240.

- Bantel E, Grosshans E, Ortonne JP. Understanding microcapillary angioma, observations in pregnant patients and in females treated with hormonal contraceptives [in German]. Z Hautkr. 1989;64:1071-1074.

- Mansur AT, Demirci GT, Ozbal Koc E, et al. An unusual lesion on the nose: microvenular hemangioma. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2018;8:7-11.

- Napekoski KM, Fernandez AP, Billings SD. Microvenular hemangioma: a clinicopathologic review of 13 cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2014;41:816-822.

- Trinidade F, Tellechea O, Torrelo A, et al. Wilms tumor 1 expression in vascular neoplasms and vascular malformations. Am J Dermatopathol. 2011;33:569-572.

- Shustef E, Kazlouskaya V, Prieto VG, et al. Cutaneous angiosarcoma: a current update. J Clin Pathol. 2017;70:917-925.

- Morgan M, Swann M, Somach S, et al. Cutaneous angiosarcoma: a case series with prognostic correlation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:867-874.

- Shon W, Billings SD. Cutaneous malignant vascular neoplasms. Clin Lab Med. 2017;37:633-646.

- Régnier-Rosencher E, Guillot B, Dupin N. Treatments for classic Kaposi sarcoma: a systematic review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:313-331.

- Tappero JW, Conant MA, Wolfe SF, et al. Kaposi's sarcoma: epidemiology, pathogenesis, histology, clinical spectrum, staging criteria and therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;28:371-395.

- Grayson W, Pantanowitz L. Histological variants of cutaneous Kaposi sarcoma. Diagn Pathol. 2008;3:31.

- Mentzel T, Partanen TA, Kutzner H. Hobnail hemangioma ("targetoid hemosiderotic hemangioma"): clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical analysis of 62 cases. J Cutan Pathol. 1999;26:279-286.

- Morales-Callaghan AM, Martinez-Garcia G, Aragoneses-Fraile H, et al. Targetoid hemosiderotic hemangioma: clinical and dermoscopical findings. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007;21:267-269.

- Kamath GH, Bhat RM, Kumar S. Tufted angioma. Int J Dermatol. 2005;44:1045-1047.

- Prasuna A, Rao P. A tufted angioma. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2015;6:266-268.

The Diagnosis: Microvenular Hemangioma

Microvenular hemangioma is an acquired benign vascular neoplasm that was described by Hunt et al1 in 1991, though Bantel et al2 reported a similar entity termed micropapillary angioma in 1989. Microvenular hemangioma typically presents as a solitary, slowly enlarging, red to violaceous, asymptomatic papule, plaque, or nodule measuring 5 to 20 mm in diameter. It usually is located on the trunk, arms, or legs of young adults without any gender predilection. Microvenular hemangioma is rare.3 The etiology has not been elucidated, though a relationship with hormonal factors such as pregnancy or hormonal contraceptives has been described.2

Histopathologically, microvenular hemangioma has a characteristic morphology. It is comprised of a well-circumscribed collection of thin-walled blood vessels with narrow lumens (quiz image).4 The blood vessels tend to infiltrate the superficial and deep dermis and are surrounded by a collagenous or desmoplastic stroma. The endothelial cells are normal in size without atypia, mitotic figures, or pleomorphism. A mild lymphoplasmacytic inflammatory infiltrate sometimes is present. Microvenular hemangioma expresses many vascular markers confirming its endothelial origin, including CD34, CD31, WT1, factor VIII-related antigen, and von Willebrand factor.3 Moreover, WT1 staining suggests the lesion is a vascular proliferative growth, as it usually is negative in vascular malformations due to errors of endothelial development.5 In addition, it lacks expression of podoplanin (D2-40), which also supports a vascular as opposed to a lymphatic origin.4

Cutaneous angiosarcoma is a rare and highly aggressive malignant neoplasm of the vascular endothelium with a predilection for the skin and superficial soft tissue. Clinical presentation is variable, as it can arise sporadically, commonly on the scalp and face of elderly patients, in areas of chronic radiation therapy, or in association with chronic lymphedema (Stewart-Treves syndrome).6 Sporadic neoplasms appear clinically as purpuric macules, plaques, or nodules and are more common in elderly men than women. They are aggressive tumors that tend to recur and metastasize despite aggressive therapy and therefore carry a poor prognosis.7 Histopathologically, well-differentiated tumors are characterized by irregular dissecting vessels lined with crowded inconspicuous endothelial cells (Figure 1). Cutaneous angiosarcoma is poorly circumscribed with marked cytologic atypia, and the vessels can take on a sinusoidal growth pattern.8

Kaposi sarcoma (KS) is a virally induced lymphoangioproliferative disease, with human herpesvirus 8 as the implicated agent. There are 4 principal clinical variants of KS: epidemic or AIDS-associated KS, endemic or African KS, KS due to iatrogenic immunosuppression, and Mediterranean or classic KS.9 Cutaneous lesions vary from pink patches to dark purple plaques or nodules that commonly occur on the lower legs10; however, the clinical appearance of KS varies depending on the clinical variant and stage. Histopathologically, early lesions of KS exhibit a superficial dermal proliferation of small angulated and jagged vessels that tend to separate into collagen bundles and are surrounded by a lymphoplasmacytic perivascular infiltrate. These native vascular structures often are surrounded by more ectatic neoplastic channels with plump endothelial cells, known as the promontory sign (Figure 2).11 With more advanced lesions, the proliferation of slitlike vessels becomes more cellular and extends deeper into the dermis and subcutis. Although the histopathologic features vary with the stage of the lesion, they do not notably vary between clinical subtypes.

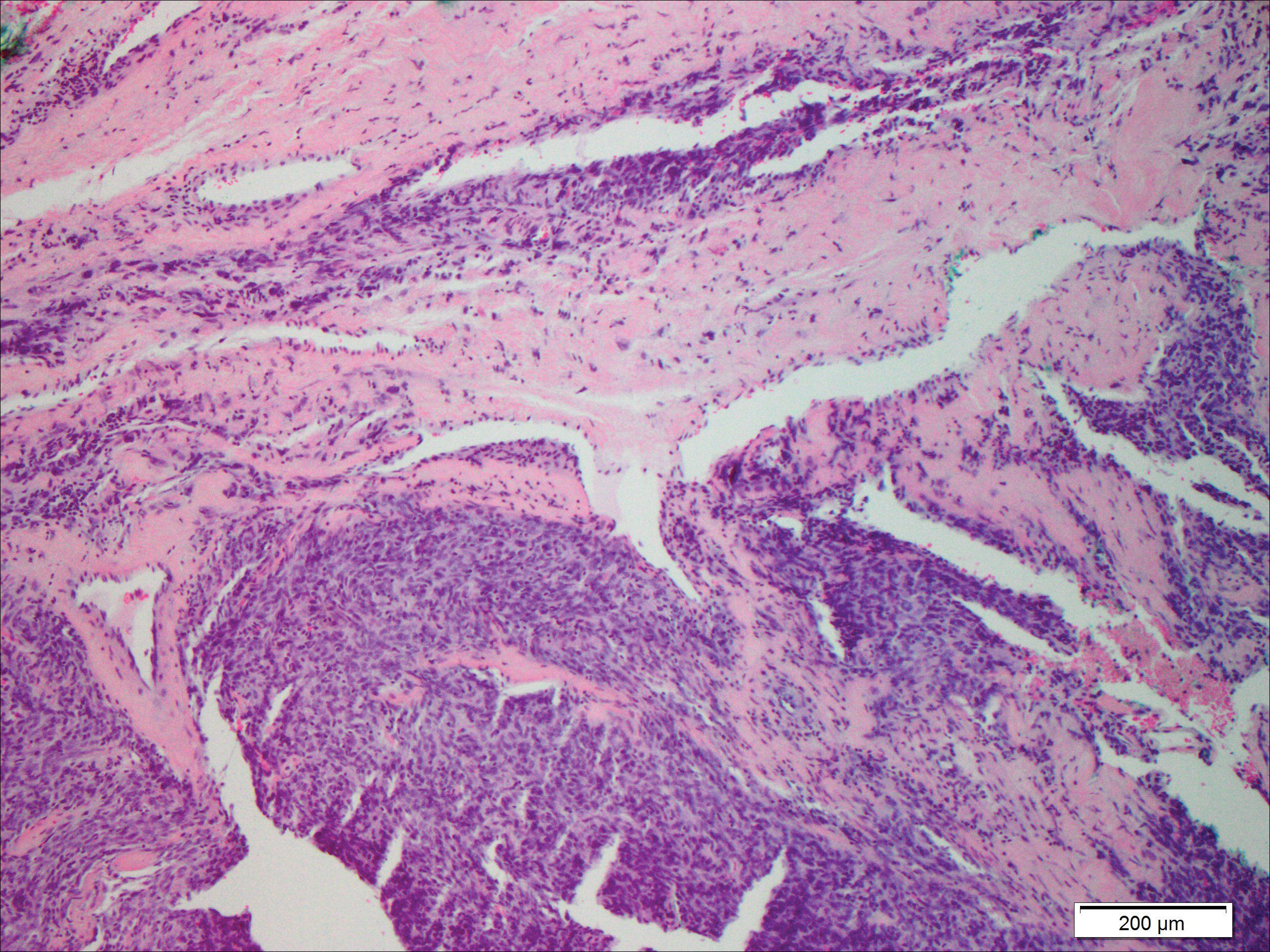

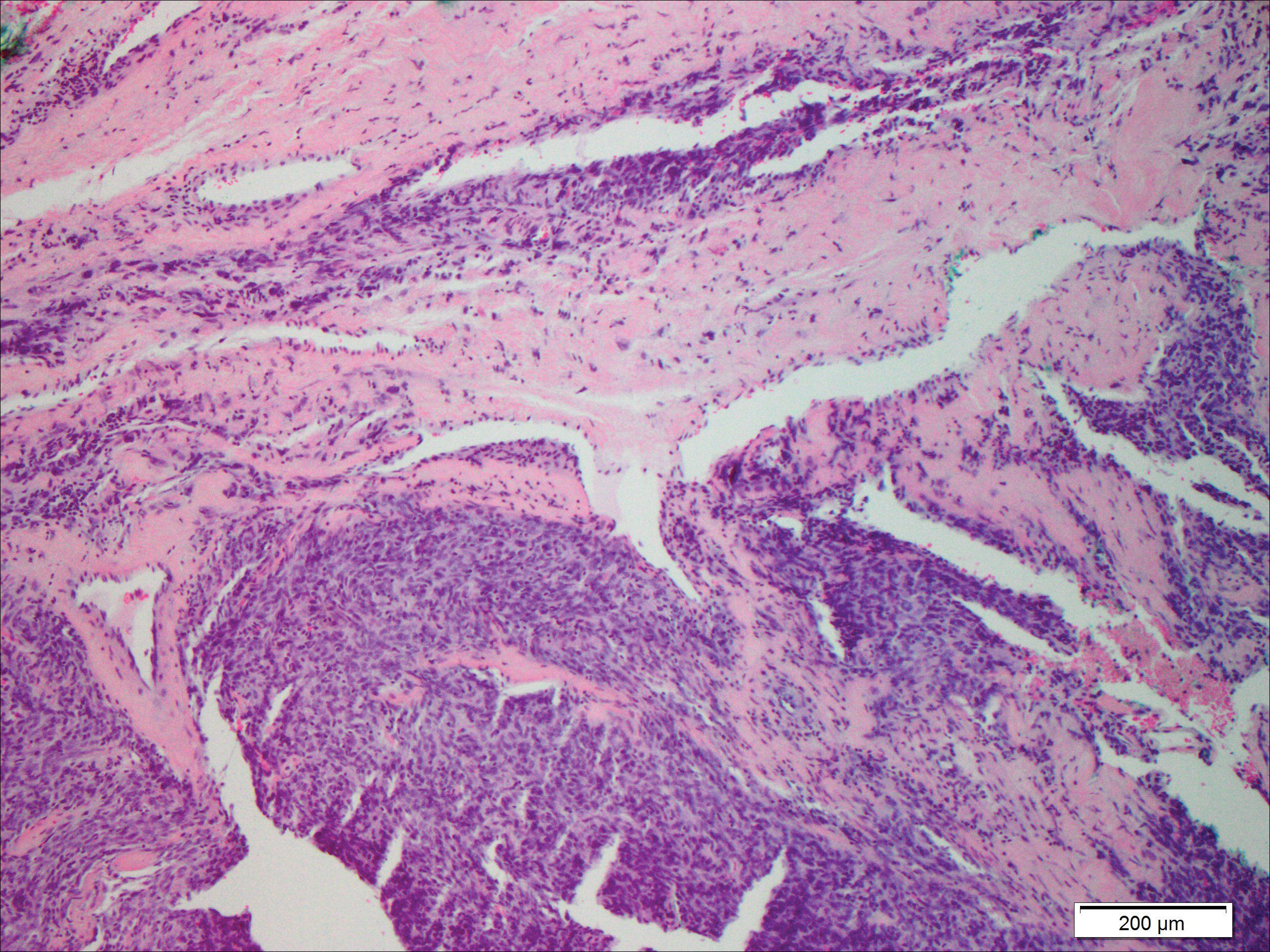

Targetoid hemosiderotic hemangioma, also known as hobnail hemangioma, is a small, benign, vascular tumor that usually affects the trunk, arms, and legs in young to middle-aged adults without a gender predilection. Clinically, it appears as a small, solitary, red to purple papule or macule that typically is surrounded by a pale thin area and a peripheral ecchymotic ring, creating a targetoid appearance, thus the term targetoid hemosiderotic hemangioma.12 Histopathologically, there is a prominent dermal vascular proliferation. In the papillary dermis, there are dilated superficial vessels lined with a single layer of endothelial cells characterized by a plump, hobnail-like appearance that protrude into the lumen (Figure 3). In the deeper dermis, the vascular spaces are angulated and slitlike and appear to dissect through collagen bundles. Hemosiderin, thrombi, extravasated erythrocytes, and a lymphocytic infiltrate also are often seen.13

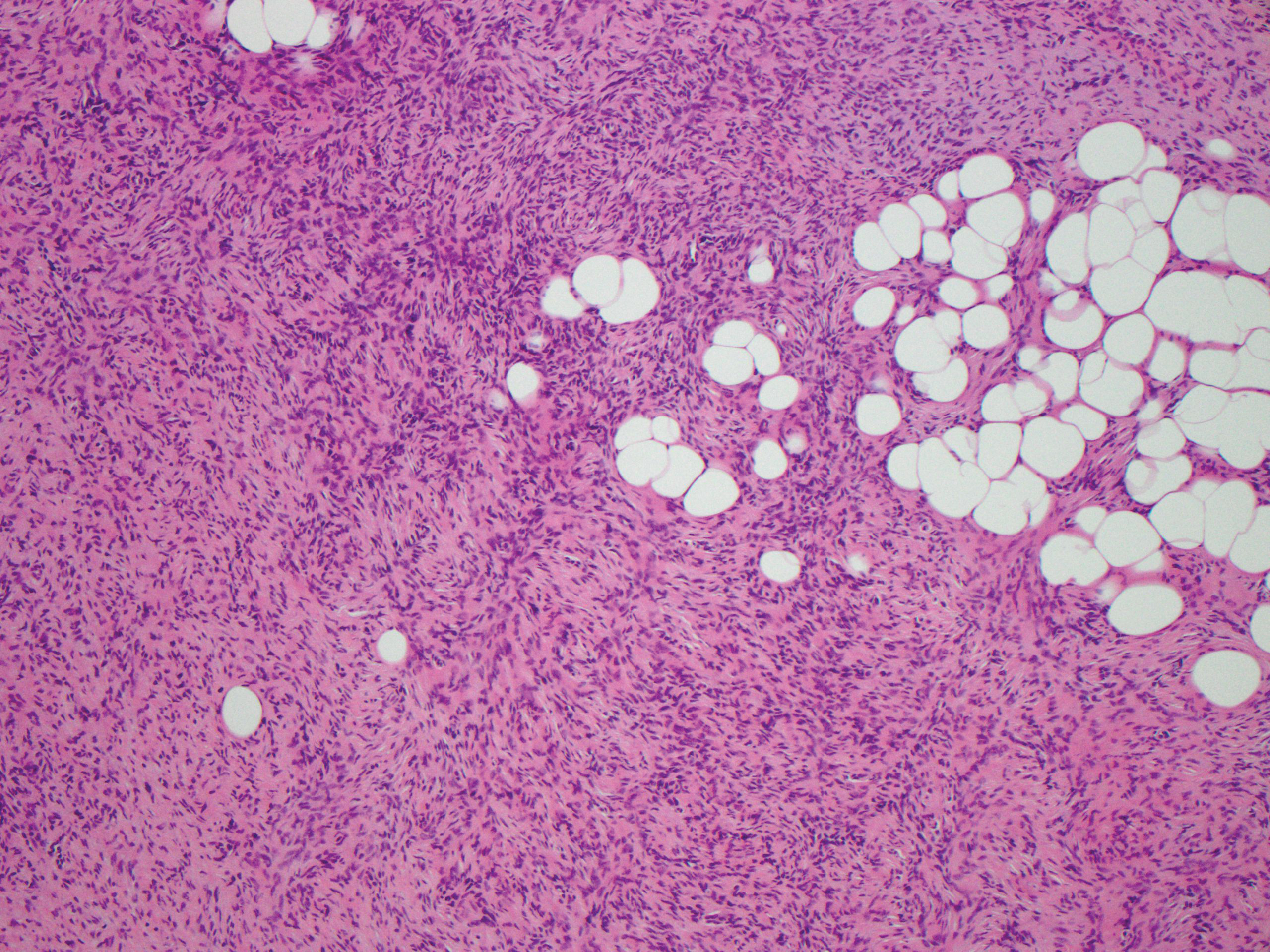

Tufted angioma is a rare benign vascular lesion that usually presents as an acquired lesion in children and young adults, though it may be congenital. It is commonly localized to the skin and subcutaneous tissues. Clinically, the lesions appear as red to purple patches and plaques that typically are located on the neck or trunk. More than 50% of cases present during the first year of life and slowly spread to involve large areas before stabilizing in size.14 Partial spontaneous regression may occur, but complete regression is rare.15 Lesions usually are asymptomatic but may be painful during periods of platelet trapping (Kasabach-Merritt phenomenon), which may develop in congenital cases. Tufted angioma is named for its characteristic histopathologic appearance, which consists of multiple discrete lobules or tufts of tightly packed capillaries in a cannonball-like appearance throughout the dermis and subcutis (Figure 4).14,15

The Diagnosis: Microvenular Hemangioma

Microvenular hemangioma is an acquired benign vascular neoplasm that was described by Hunt et al1 in 1991, though Bantel et al2 reported a similar entity termed micropapillary angioma in 1989. Microvenular hemangioma typically presents as a solitary, slowly enlarging, red to violaceous, asymptomatic papule, plaque, or nodule measuring 5 to 20 mm in diameter. It usually is located on the trunk, arms, or legs of young adults without any gender predilection. Microvenular hemangioma is rare.3 The etiology has not been elucidated, though a relationship with hormonal factors such as pregnancy or hormonal contraceptives has been described.2

Histopathologically, microvenular hemangioma has a characteristic morphology. It is comprised of a well-circumscribed collection of thin-walled blood vessels with narrow lumens (quiz image).4 The blood vessels tend to infiltrate the superficial and deep dermis and are surrounded by a collagenous or desmoplastic stroma. The endothelial cells are normal in size without atypia, mitotic figures, or pleomorphism. A mild lymphoplasmacytic inflammatory infiltrate sometimes is present. Microvenular hemangioma expresses many vascular markers confirming its endothelial origin, including CD34, CD31, WT1, factor VIII-related antigen, and von Willebrand factor.3 Moreover, WT1 staining suggests the lesion is a vascular proliferative growth, as it usually is negative in vascular malformations due to errors of endothelial development.5 In addition, it lacks expression of podoplanin (D2-40), which also supports a vascular as opposed to a lymphatic origin.4

Cutaneous angiosarcoma is a rare and highly aggressive malignant neoplasm of the vascular endothelium with a predilection for the skin and superficial soft tissue. Clinical presentation is variable, as it can arise sporadically, commonly on the scalp and face of elderly patients, in areas of chronic radiation therapy, or in association with chronic lymphedema (Stewart-Treves syndrome).6 Sporadic neoplasms appear clinically as purpuric macules, plaques, or nodules and are more common in elderly men than women. They are aggressive tumors that tend to recur and metastasize despite aggressive therapy and therefore carry a poor prognosis.7 Histopathologically, well-differentiated tumors are characterized by irregular dissecting vessels lined with crowded inconspicuous endothelial cells (Figure 1). Cutaneous angiosarcoma is poorly circumscribed with marked cytologic atypia, and the vessels can take on a sinusoidal growth pattern.8

Kaposi sarcoma (KS) is a virally induced lymphoangioproliferative disease, with human herpesvirus 8 as the implicated agent. There are 4 principal clinical variants of KS: epidemic or AIDS-associated KS, endemic or African KS, KS due to iatrogenic immunosuppression, and Mediterranean or classic KS.9 Cutaneous lesions vary from pink patches to dark purple plaques or nodules that commonly occur on the lower legs10; however, the clinical appearance of KS varies depending on the clinical variant and stage. Histopathologically, early lesions of KS exhibit a superficial dermal proliferation of small angulated and jagged vessels that tend to separate into collagen bundles and are surrounded by a lymphoplasmacytic perivascular infiltrate. These native vascular structures often are surrounded by more ectatic neoplastic channels with plump endothelial cells, known as the promontory sign (Figure 2).11 With more advanced lesions, the proliferation of slitlike vessels becomes more cellular and extends deeper into the dermis and subcutis. Although the histopathologic features vary with the stage of the lesion, they do not notably vary between clinical subtypes.

Targetoid hemosiderotic hemangioma, also known as hobnail hemangioma, is a small, benign, vascular tumor that usually affects the trunk, arms, and legs in young to middle-aged adults without a gender predilection. Clinically, it appears as a small, solitary, red to purple papule or macule that typically is surrounded by a pale thin area and a peripheral ecchymotic ring, creating a targetoid appearance, thus the term targetoid hemosiderotic hemangioma.12 Histopathologically, there is a prominent dermal vascular proliferation. In the papillary dermis, there are dilated superficial vessels lined with a single layer of endothelial cells characterized by a plump, hobnail-like appearance that protrude into the lumen (Figure 3). In the deeper dermis, the vascular spaces are angulated and slitlike and appear to dissect through collagen bundles. Hemosiderin, thrombi, extravasated erythrocytes, and a lymphocytic infiltrate also are often seen.13

Tufted angioma is a rare benign vascular lesion that usually presents as an acquired lesion in children and young adults, though it may be congenital. It is commonly localized to the skin and subcutaneous tissues. Clinically, the lesions appear as red to purple patches and plaques that typically are located on the neck or trunk. More than 50% of cases present during the first year of life and slowly spread to involve large areas before stabilizing in size.14 Partial spontaneous regression may occur, but complete regression is rare.15 Lesions usually are asymptomatic but may be painful during periods of platelet trapping (Kasabach-Merritt phenomenon), which may develop in congenital cases. Tufted angioma is named for its characteristic histopathologic appearance, which consists of multiple discrete lobules or tufts of tightly packed capillaries in a cannonball-like appearance throughout the dermis and subcutis (Figure 4).14,15

- Hunt SJ, Santa Cruz DJ, Barr RJ. Microvenular hemangioma. J Cutan Pathol. 1991;18:235-240.

- Bantel E, Grosshans E, Ortonne JP. Understanding microcapillary angioma, observations in pregnant patients and in females treated with hormonal contraceptives [in German]. Z Hautkr. 1989;64:1071-1074.

- Mansur AT, Demirci GT, Ozbal Koc E, et al. An unusual lesion on the nose: microvenular hemangioma. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2018;8:7-11.

- Napekoski KM, Fernandez AP, Billings SD. Microvenular hemangioma: a clinicopathologic review of 13 cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2014;41:816-822.

- Trinidade F, Tellechea O, Torrelo A, et al. Wilms tumor 1 expression in vascular neoplasms and vascular malformations. Am J Dermatopathol. 2011;33:569-572.

- Shustef E, Kazlouskaya V, Prieto VG, et al. Cutaneous angiosarcoma: a current update. J Clin Pathol. 2017;70:917-925.

- Morgan M, Swann M, Somach S, et al. Cutaneous angiosarcoma: a case series with prognostic correlation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:867-874.

- Shon W, Billings SD. Cutaneous malignant vascular neoplasms. Clin Lab Med. 2017;37:633-646.

- Régnier-Rosencher E, Guillot B, Dupin N. Treatments for classic Kaposi sarcoma: a systematic review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:313-331.

- Tappero JW, Conant MA, Wolfe SF, et al. Kaposi's sarcoma: epidemiology, pathogenesis, histology, clinical spectrum, staging criteria and therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;28:371-395.

- Grayson W, Pantanowitz L. Histological variants of cutaneous Kaposi sarcoma. Diagn Pathol. 2008;3:31.

- Mentzel T, Partanen TA, Kutzner H. Hobnail hemangioma ("targetoid hemosiderotic hemangioma"): clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical analysis of 62 cases. J Cutan Pathol. 1999;26:279-286.

- Morales-Callaghan AM, Martinez-Garcia G, Aragoneses-Fraile H, et al. Targetoid hemosiderotic hemangioma: clinical and dermoscopical findings. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007;21:267-269.

- Kamath GH, Bhat RM, Kumar S. Tufted angioma. Int J Dermatol. 2005;44:1045-1047.

- Prasuna A, Rao P. A tufted angioma. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2015;6:266-268.

- Hunt SJ, Santa Cruz DJ, Barr RJ. Microvenular hemangioma. J Cutan Pathol. 1991;18:235-240.

- Bantel E, Grosshans E, Ortonne JP. Understanding microcapillary angioma, observations in pregnant patients and in females treated with hormonal contraceptives [in German]. Z Hautkr. 1989;64:1071-1074.

- Mansur AT, Demirci GT, Ozbal Koc E, et al. An unusual lesion on the nose: microvenular hemangioma. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2018;8:7-11.

- Napekoski KM, Fernandez AP, Billings SD. Microvenular hemangioma: a clinicopathologic review of 13 cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2014;41:816-822.

- Trinidade F, Tellechea O, Torrelo A, et al. Wilms tumor 1 expression in vascular neoplasms and vascular malformations. Am J Dermatopathol. 2011;33:569-572.

- Shustef E, Kazlouskaya V, Prieto VG, et al. Cutaneous angiosarcoma: a current update. J Clin Pathol. 2017;70:917-925.

- Morgan M, Swann M, Somach S, et al. Cutaneous angiosarcoma: a case series with prognostic correlation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:867-874.

- Shon W, Billings SD. Cutaneous malignant vascular neoplasms. Clin Lab Med. 2017;37:633-646.

- Régnier-Rosencher E, Guillot B, Dupin N. Treatments for classic Kaposi sarcoma: a systematic review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:313-331.

- Tappero JW, Conant MA, Wolfe SF, et al. Kaposi's sarcoma: epidemiology, pathogenesis, histology, clinical spectrum, staging criteria and therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;28:371-395.

- Grayson W, Pantanowitz L. Histological variants of cutaneous Kaposi sarcoma. Diagn Pathol. 2008;3:31.

- Mentzel T, Partanen TA, Kutzner H. Hobnail hemangioma ("targetoid hemosiderotic hemangioma"): clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical analysis of 62 cases. J Cutan Pathol. 1999;26:279-286.

- Morales-Callaghan AM, Martinez-Garcia G, Aragoneses-Fraile H, et al. Targetoid hemosiderotic hemangioma: clinical and dermoscopical findings. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007;21:267-269.

- Kamath GH, Bhat RM, Kumar S. Tufted angioma. Int J Dermatol. 2005;44:1045-1047.

- Prasuna A, Rao P. A tufted angioma. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2015;6:266-268.

A 38-year-old woman presented with an asymptomatic lesion on the abdomen. On physical examination, there was a 5×2-mm, solitary, ill-defined pink macule on the right side of the abdomen. The patient denied recent change in size or color of the lesion, prior trauma, or a personal or family history of similar lesions. Due to the uncertain diagnostic appearance, a punch biopsy was performed.

Solitary Tender Nodule on the Back

The Diagnosis: Solitary Fibrous Tumor

Solitary fibrous tumors (SFTs), as first described by Klemperer and Rabin1 in 1931, are relatively uncommon mesenchymal neoplasms that occur primarily in the pleura. This lesion is now known to affect many other extrathoracic sites, such as the liver, kidney, adrenal glands, thyroid, central nervous system, and soft tissue, with rare examples originating from the skin.2 Okamura et al3 reported the first known case of cutaneous SFT in 1997, with most of the literature limited to case reports. Erdag et al2 described one of the largest case series of primary cutaneous SFTs. These lesions can occur across a wide age range but tend to primarily affect middle-aged adults. Solitary fibrous tumors have been known to have no sex predilection; however, Erdag et al2 found a male predominance with a male to female ratio of 4 to 1.

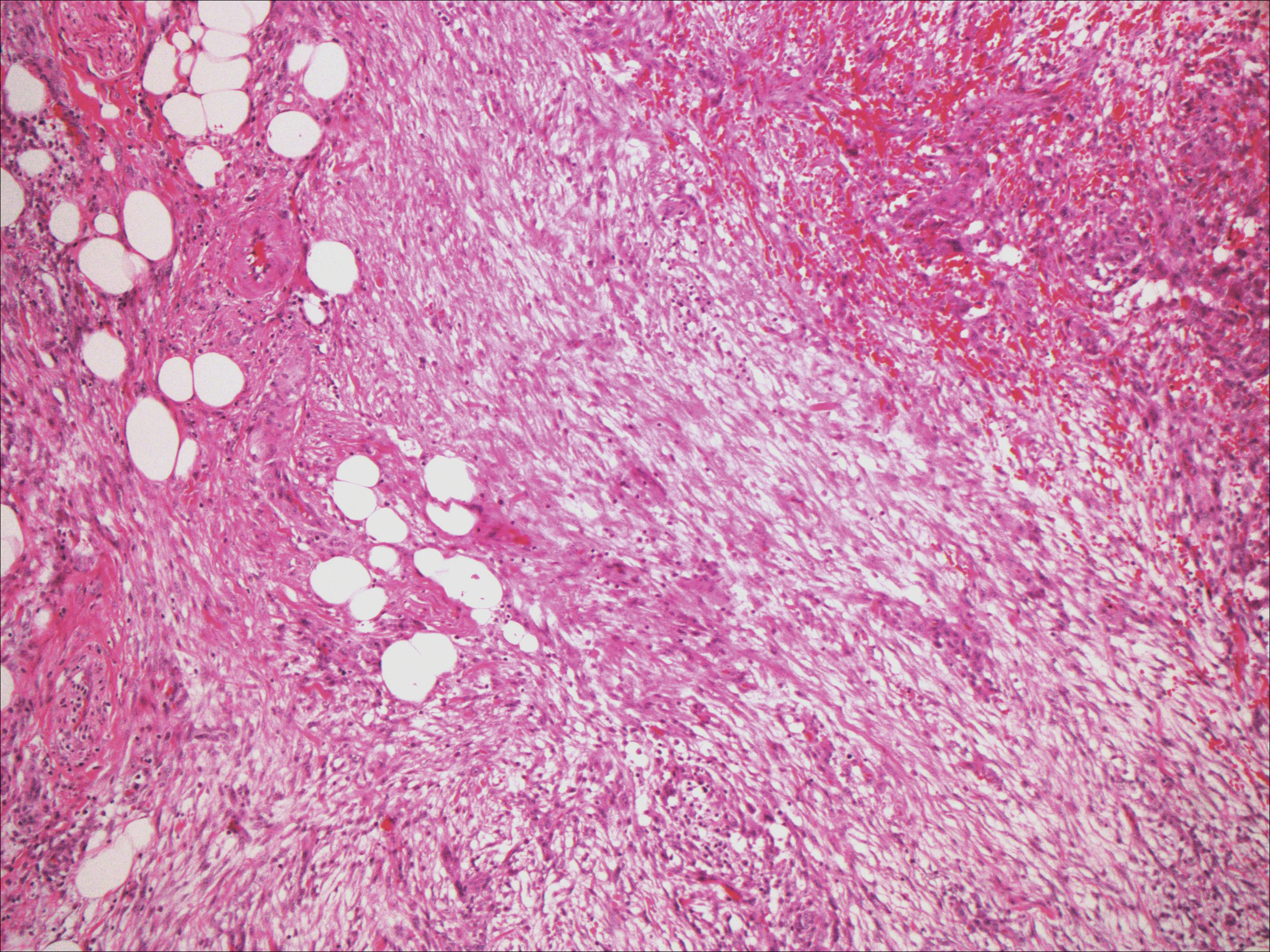

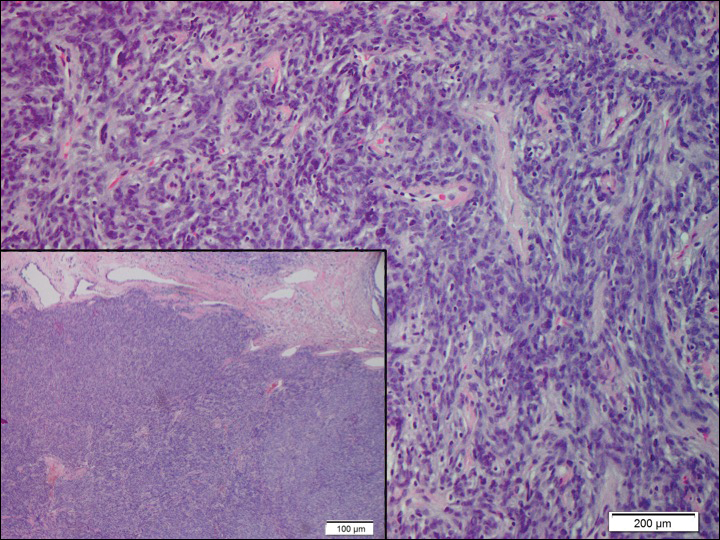

Histopathologically, a cutaneous SFT is known to appear as a well-circumscribed nodular spindle cell proliferation arranged in interlacing fascicles with an abundant hyalinized collagen stroma (quiz image). Alternating hypocellular and hypercellular areas can be seen. Supporting vasculature often is relatively prominent, represented by angulated and branching staghorn blood vessels (Figure 1).2 A common histopathologic finding of SFTs is a patternless pattern, which suggests that the tumor can have a variety of morphologic appearances (eg, storiform, fascicular, neural, herringbone growth patterns), making histologic diagnosis difficult (quiz image).4 Therefore, immunohistochemistry plays a large role in the diagnosis of this tumor. The most important positive markers include CD34, CD99, B-cell lymphoma 2 (BCL-2), and signal transducer and activator of transcription 6 (STAT6).5 Nuclear STAT6 staining is an immunomarker for NGFI-A binding protein 2 (NAB2)-STAT6 gene fusion, which is specific for SFT.5,6 Vivero et al7 also reported glutamate receptor, inotropic, AMPA 2 (GRIA2) as a useful immunostain in SFT, though it is also expressed in dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP). In this case, the clinical and histopathologic findings best supported a diagnosis of SFT. Some consider hemangiopericytomas to be examples of SFTs; however, true hemangiopericytomas lack the thick hyalinized collagen and hypercellular areas seen in SFT.

A cellular dermatofibroma generally presents as a single round, reddish brown papule or nodule approximately 0.5 to 1 cm in diameter that is firm to palpation with a central depression or dimple created over the lesion from the lateral pressure. Cellular dermatofibromas mostly occur in middle-aged adults, with the most common locations on the legs and on the sides of the trunk. They are thought to arise after injuries to the skin. On histopathologic examination, cellular dermatofibromas typically exhibit a proliferation of fibrohistiocytic cells with collagen trapping, often at the periphery of the tumor (Figure 2). Although cellular dermatofibromas appear clinically different than SFTs, they often mimic SFTs histopathologically. Immunostaining also can be helpful in differentiating cellular dermatofibromas in which cells stain positive for factor XIIIa. CD34 staining is negative.

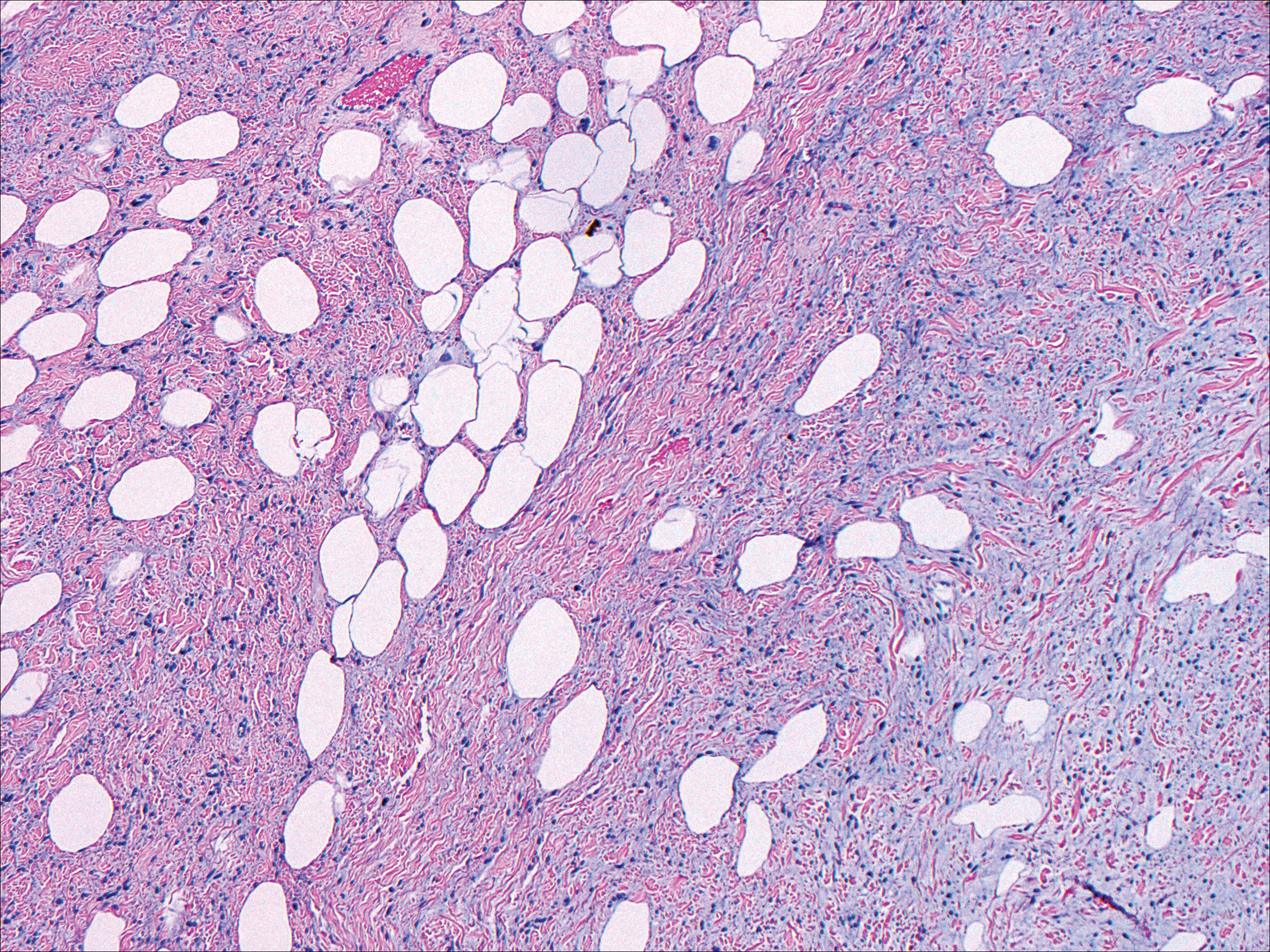

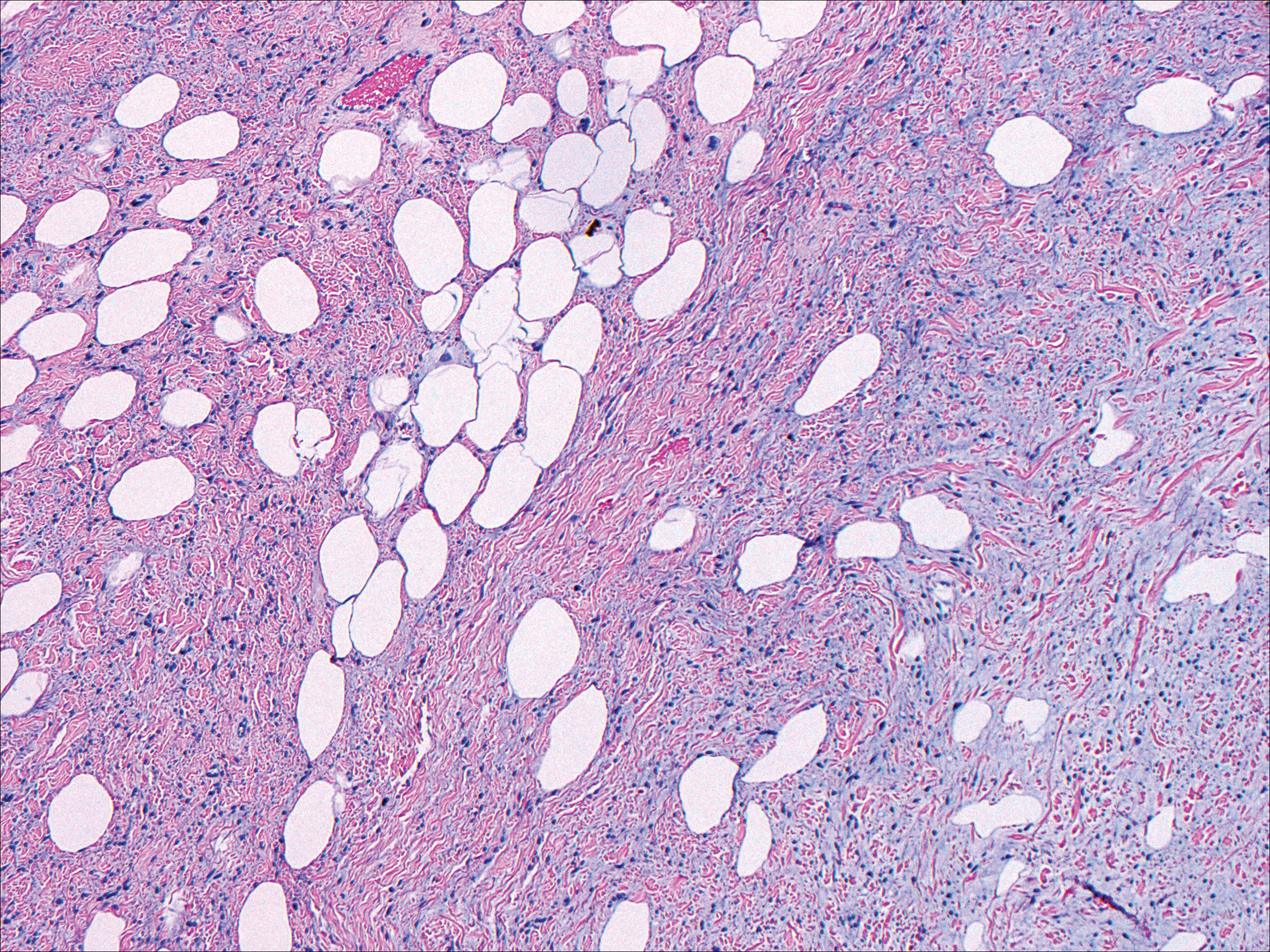

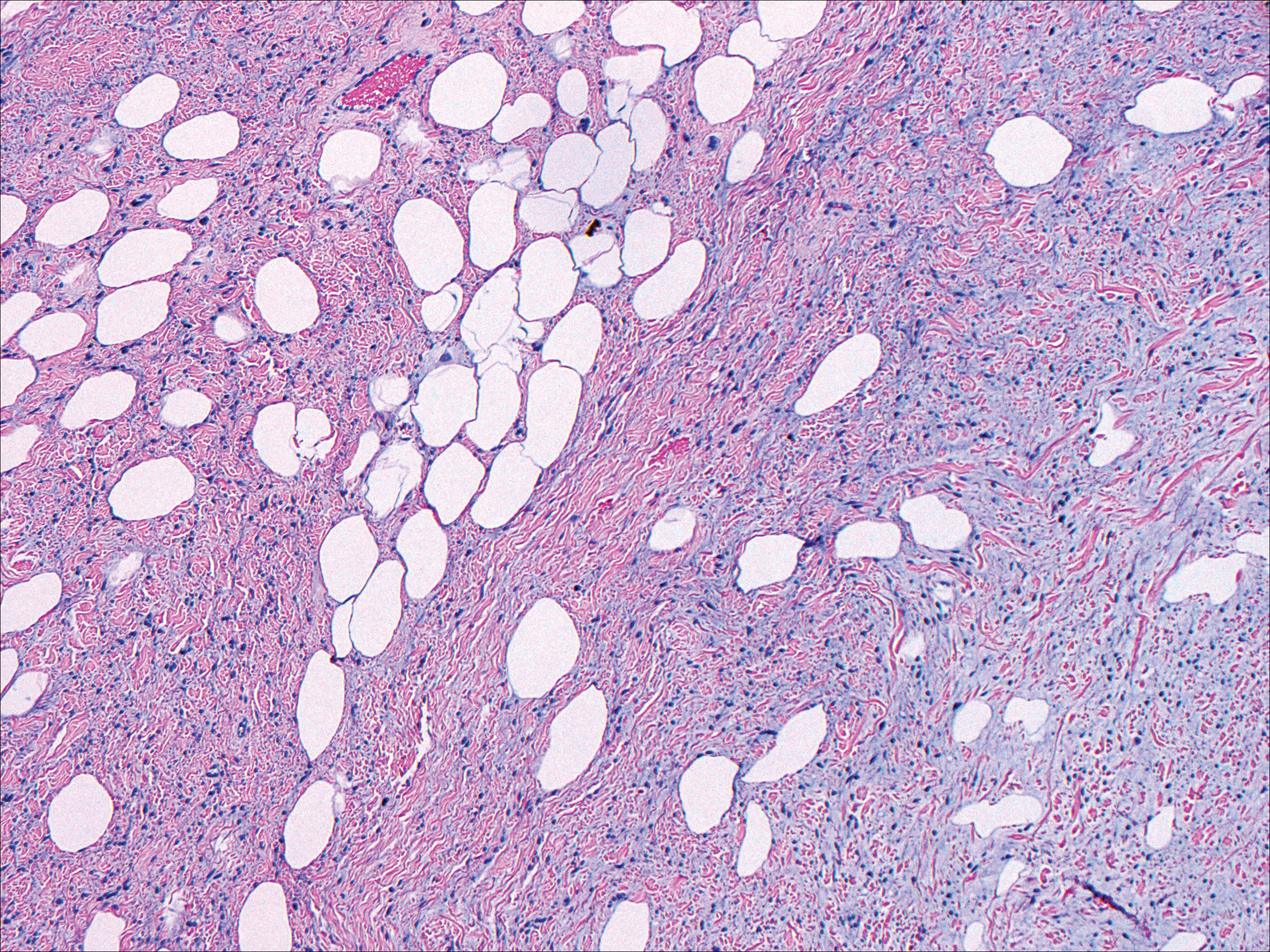

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans usually appears as one or multiple firm, red to violaceous nodules or plaques. They most often occur on the trunk in middle-aged adults. Histopathologically, DFSP presents with a dense, hypercellular, spindle cell proliferation that demonstrates a typical storiform pattern. The tumor generally infiltrates into the deep dermis and subcutaneous adipose layer with characteristic adipocyte entrapment (Figure 3). Positive CD34 and negative factor XIIIa staining helps to differentiate DFSP from a cellular dermatofibroma. Immunohistochemically, it is more difficult to distinguish DFSP from SFT, as both are CD34+ spindle cell neoplasms that also stain positive for CD99 and BCL-2.2 GRIA2 positivity also is seen in both SFT and DFSP.7 However, differentiation can be made on morphologic grounds alone, as DFSP has ill-defined tumor borders with adnexal and fat entrapment and SFT tends to be more circumscribed with prominent arborizing hyalinized vessels.8

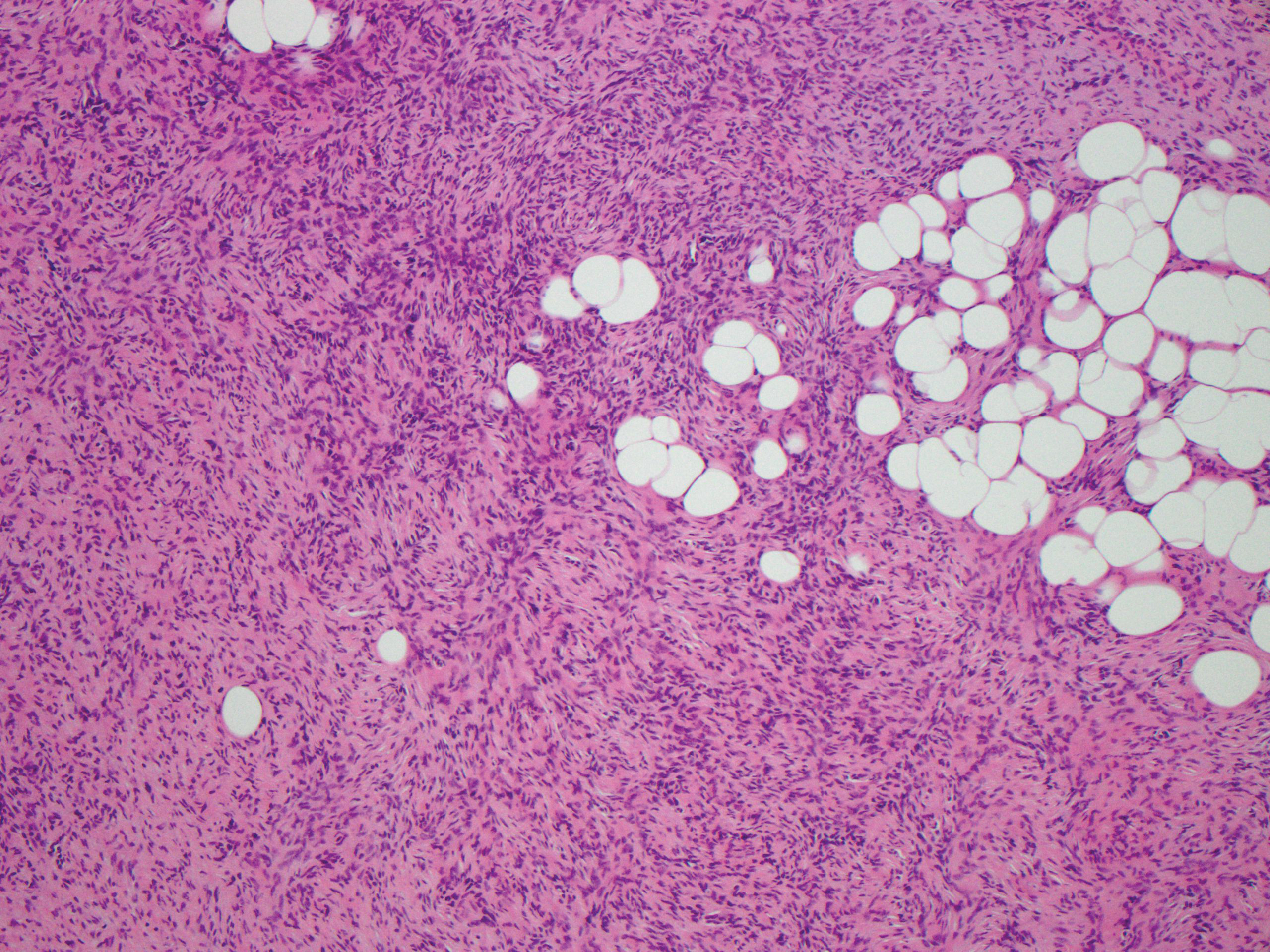

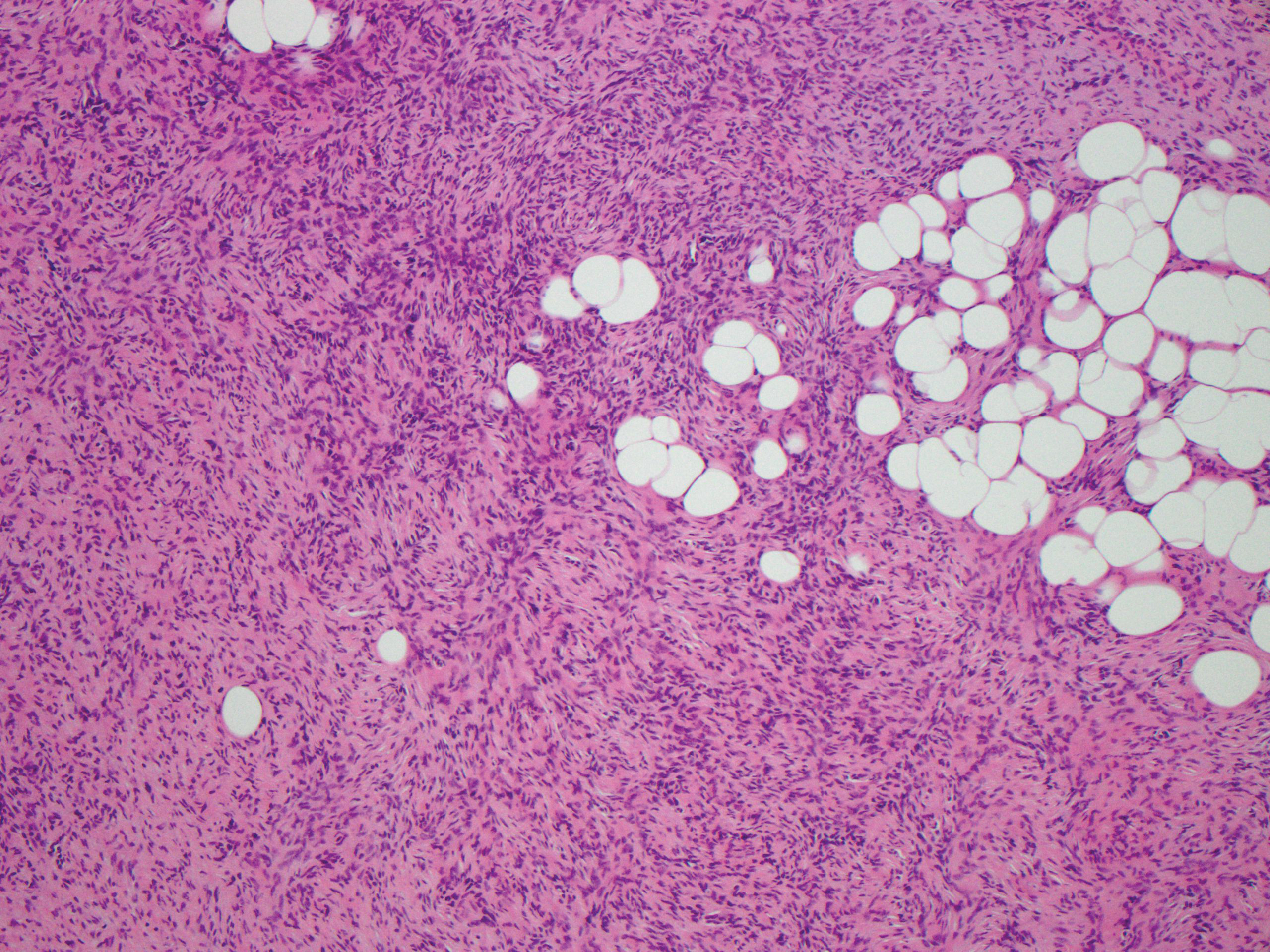

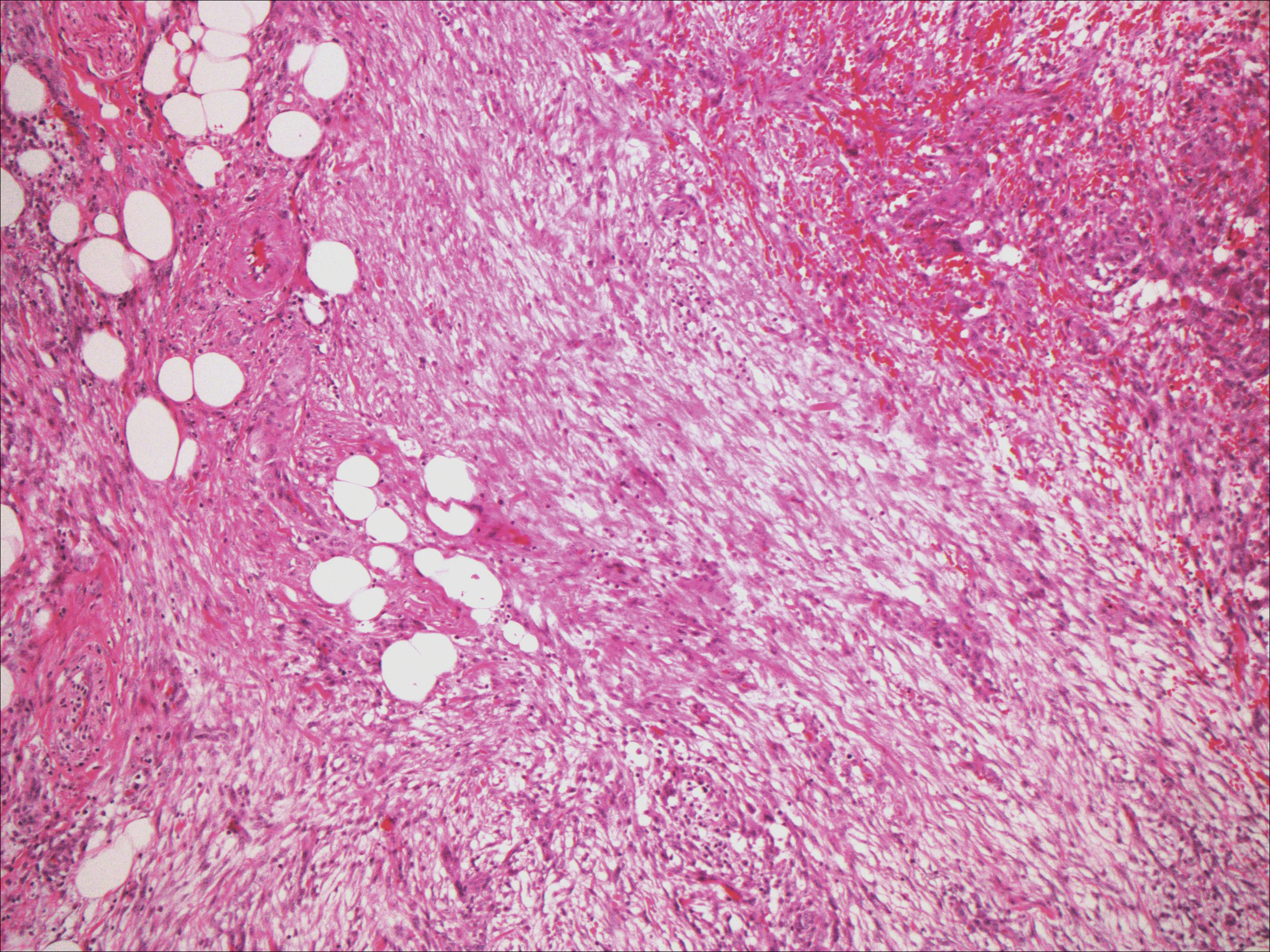

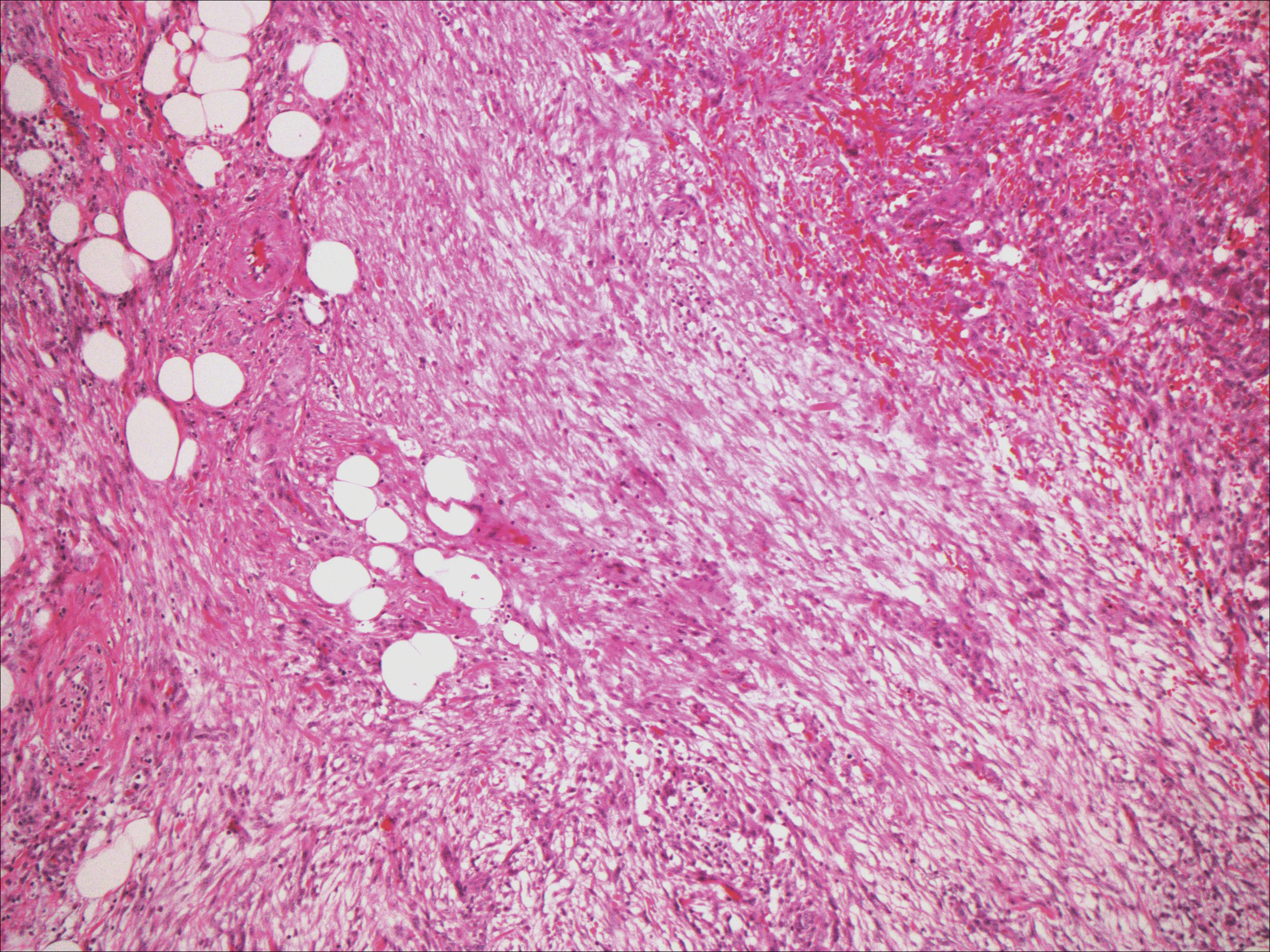

Spindle cell lipoma (SCL) is an asymptomatic subcutaneous tumor commonly located on the back, neck, and shoulders in older patients, typically men. It often presents as a solitary lesion, though multiple lesions may occur. It is a well-circumscribed tumor of mature adipose tissue with areas of spindle cell proliferation and ropey collagen bundles (Figure 4). In early lesions, the spindle cell areas are myxoid with the presence of many mast cells.9 The spindle cells stain positive for CD34. Although spindle cell lipoma would be included in both the clinical and histopathologic differential diagnosis for SFT, its histopathologic features often are enough to differentiate SCL, which is highlighted by the aforementioned features as well as a relatively low cellularity and lack of ectatic vessels.8 However, discerning tumor variants, such as low-fat pseudoangiomatous SCL and lipomatous or myxoid SFT, might prove more challenging.

Nodular fasciitis typically presents as a rapidly growing subcutaneous nodule that may be tender. It is a benign reactive process usually affecting the arms and trunk of young to middle-aged adults, though it commonly involves the head and neck region in children.10 The tumor histopathologically appears as a well-circumscribed subcutaneous or fascial nodule with an angulated appearance. Spindle-shaped and stellate fibroblasts are loosely arranged in an edematous myxomatous stroma with a feathered appearance (Figure 5). Extravasated erythrocytes often are present. With time, collagen bundles become thicker and hyalinized. Immunohistochemical studies demonstrate positivity for vimentin, calponin, muscle-specific actin, and smooth muscle actin. Desmin, CD34, cytokeratin, and S-100 typically are negative.10-12 Therefore, CD34 staining is one of the main differentiating factors between nodular fasciitis and SFTs.

- Klemperer P, Rabin CB. Primary neoplasms of the pleura: a report of five cases. Arch Pathol. 1931;11:385-412.

- Erdag G, Qureshi HS, Patterson JW, et al. Solitary fibrous tumors of the skin: a clinicopathologic study of 10 cases and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2007;34:844-850.

- Okamura JM, Barr RJ, Battifora H. Solitary fibrous tumor of the skin. Am J Dermatopathol. 1997;19:515-518.

- Lee JY, Park SE, Shin SJ, et al. Solitary fibrous tumor with myxoid stromal change. Am J Dermatopathol. 2015;37:570-573.

- Geramizadeh B, Marzban M, Churg A. Role of immunohistochemistry in the diagnosis of solitary fibrous tumor, a review. Iran J Pathol. 2016;11:195-293.

- Creytens D, Ferdinande L, Dorpe JV. Histopathologically malignant solitary fibrous tumor of the skin: a report of an unusual case. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:629-631.

- Vivero M, Doyle LA, Fletcher CD, et al. GRIA2 is a novel diagnostic marker for solitary fibrous tumour identified through gene expression profiling. Histopathology. 2014;65:71-80.

- Wood L, Fountaine TJ, Rosamilia L, et al. Cutaneous CD34 spindle cell neoplasms: histopathologic features distinguish spindle cell lipoma, solitary fibrous tumor, and dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:764-768.

- Khatib Y, Khade AL, Shah VB, et al. Cytohistological features of spindle cell lipoma--a case report with differential diagnosis. J Clin Diagn Res. 2017;11:10-11.

- Kumar E, Patel NR, Demicco EG, et al. Cutaneous nodular fasciitis with genetic analysis: a case series. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:1143-1149.

- Bracey TS, Wharton S, Smith ME. Nodular 'fasciitis' presenting as a cutaneous polyp. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:980-982.

- Perez-Montiel MD, Plaza JA, Dominguez-Malagon H, et al. Differential expression of smooth muscle myosin, smooth muscle actin, h-caldesmon, and calponin in the diagnosis of myofibroblastic and smooth muscle lesions of skin and soft tissue. Am J Dermatopathol. 2006;28:105-111.

The Diagnosis: Solitary Fibrous Tumor

Solitary fibrous tumors (SFTs), as first described by Klemperer and Rabin1 in 1931, are relatively uncommon mesenchymal neoplasms that occur primarily in the pleura. This lesion is now known to affect many other extrathoracic sites, such as the liver, kidney, adrenal glands, thyroid, central nervous system, and soft tissue, with rare examples originating from the skin.2 Okamura et al3 reported the first known case of cutaneous SFT in 1997, with most of the literature limited to case reports. Erdag et al2 described one of the largest case series of primary cutaneous SFTs. These lesions can occur across a wide age range but tend to primarily affect middle-aged adults. Solitary fibrous tumors have been known to have no sex predilection; however, Erdag et al2 found a male predominance with a male to female ratio of 4 to 1.

Histopathologically, a cutaneous SFT is known to appear as a well-circumscribed nodular spindle cell proliferation arranged in interlacing fascicles with an abundant hyalinized collagen stroma (quiz image). Alternating hypocellular and hypercellular areas can be seen. Supporting vasculature often is relatively prominent, represented by angulated and branching staghorn blood vessels (Figure 1).2 A common histopathologic finding of SFTs is a patternless pattern, which suggests that the tumor can have a variety of morphologic appearances (eg, storiform, fascicular, neural, herringbone growth patterns), making histologic diagnosis difficult (quiz image).4 Therefore, immunohistochemistry plays a large role in the diagnosis of this tumor. The most important positive markers include CD34, CD99, B-cell lymphoma 2 (BCL-2), and signal transducer and activator of transcription 6 (STAT6).5 Nuclear STAT6 staining is an immunomarker for NGFI-A binding protein 2 (NAB2)-STAT6 gene fusion, which is specific for SFT.5,6 Vivero et al7 also reported glutamate receptor, inotropic, AMPA 2 (GRIA2) as a useful immunostain in SFT, though it is also expressed in dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP). In this case, the clinical and histopathologic findings best supported a diagnosis of SFT. Some consider hemangiopericytomas to be examples of SFTs; however, true hemangiopericytomas lack the thick hyalinized collagen and hypercellular areas seen in SFT.

A cellular dermatofibroma generally presents as a single round, reddish brown papule or nodule approximately 0.5 to 1 cm in diameter that is firm to palpation with a central depression or dimple created over the lesion from the lateral pressure. Cellular dermatofibromas mostly occur in middle-aged adults, with the most common locations on the legs and on the sides of the trunk. They are thought to arise after injuries to the skin. On histopathologic examination, cellular dermatofibromas typically exhibit a proliferation of fibrohistiocytic cells with collagen trapping, often at the periphery of the tumor (Figure 2). Although cellular dermatofibromas appear clinically different than SFTs, they often mimic SFTs histopathologically. Immunostaining also can be helpful in differentiating cellular dermatofibromas in which cells stain positive for factor XIIIa. CD34 staining is negative.

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans usually appears as one or multiple firm, red to violaceous nodules or plaques. They most often occur on the trunk in middle-aged adults. Histopathologically, DFSP presents with a dense, hypercellular, spindle cell proliferation that demonstrates a typical storiform pattern. The tumor generally infiltrates into the deep dermis and subcutaneous adipose layer with characteristic adipocyte entrapment (Figure 3). Positive CD34 and negative factor XIIIa staining helps to differentiate DFSP from a cellular dermatofibroma. Immunohistochemically, it is more difficult to distinguish DFSP from SFT, as both are CD34+ spindle cell neoplasms that also stain positive for CD99 and BCL-2.2 GRIA2 positivity also is seen in both SFT and DFSP.7 However, differentiation can be made on morphologic grounds alone, as DFSP has ill-defined tumor borders with adnexal and fat entrapment and SFT tends to be more circumscribed with prominent arborizing hyalinized vessels.8

Spindle cell lipoma (SCL) is an asymptomatic subcutaneous tumor commonly located on the back, neck, and shoulders in older patients, typically men. It often presents as a solitary lesion, though multiple lesions may occur. It is a well-circumscribed tumor of mature adipose tissue with areas of spindle cell proliferation and ropey collagen bundles (Figure 4). In early lesions, the spindle cell areas are myxoid with the presence of many mast cells.9 The spindle cells stain positive for CD34. Although spindle cell lipoma would be included in both the clinical and histopathologic differential diagnosis for SFT, its histopathologic features often are enough to differentiate SCL, which is highlighted by the aforementioned features as well as a relatively low cellularity and lack of ectatic vessels.8 However, discerning tumor variants, such as low-fat pseudoangiomatous SCL and lipomatous or myxoid SFT, might prove more challenging.

Nodular fasciitis typically presents as a rapidly growing subcutaneous nodule that may be tender. It is a benign reactive process usually affecting the arms and trunk of young to middle-aged adults, though it commonly involves the head and neck region in children.10 The tumor histopathologically appears as a well-circumscribed subcutaneous or fascial nodule with an angulated appearance. Spindle-shaped and stellate fibroblasts are loosely arranged in an edematous myxomatous stroma with a feathered appearance (Figure 5). Extravasated erythrocytes often are present. With time, collagen bundles become thicker and hyalinized. Immunohistochemical studies demonstrate positivity for vimentin, calponin, muscle-specific actin, and smooth muscle actin. Desmin, CD34, cytokeratin, and S-100 typically are negative.10-12 Therefore, CD34 staining is one of the main differentiating factors between nodular fasciitis and SFTs.

The Diagnosis: Solitary Fibrous Tumor

Solitary fibrous tumors (SFTs), as first described by Klemperer and Rabin1 in 1931, are relatively uncommon mesenchymal neoplasms that occur primarily in the pleura. This lesion is now known to affect many other extrathoracic sites, such as the liver, kidney, adrenal glands, thyroid, central nervous system, and soft tissue, with rare examples originating from the skin.2 Okamura et al3 reported the first known case of cutaneous SFT in 1997, with most of the literature limited to case reports. Erdag et al2 described one of the largest case series of primary cutaneous SFTs. These lesions can occur across a wide age range but tend to primarily affect middle-aged adults. Solitary fibrous tumors have been known to have no sex predilection; however, Erdag et al2 found a male predominance with a male to female ratio of 4 to 1.

Histopathologically, a cutaneous SFT is known to appear as a well-circumscribed nodular spindle cell proliferation arranged in interlacing fascicles with an abundant hyalinized collagen stroma (quiz image). Alternating hypocellular and hypercellular areas can be seen. Supporting vasculature often is relatively prominent, represented by angulated and branching staghorn blood vessels (Figure 1).2 A common histopathologic finding of SFTs is a patternless pattern, which suggests that the tumor can have a variety of morphologic appearances (eg, storiform, fascicular, neural, herringbone growth patterns), making histologic diagnosis difficult (quiz image).4 Therefore, immunohistochemistry plays a large role in the diagnosis of this tumor. The most important positive markers include CD34, CD99, B-cell lymphoma 2 (BCL-2), and signal transducer and activator of transcription 6 (STAT6).5 Nuclear STAT6 staining is an immunomarker for NGFI-A binding protein 2 (NAB2)-STAT6 gene fusion, which is specific for SFT.5,6 Vivero et al7 also reported glutamate receptor, inotropic, AMPA 2 (GRIA2) as a useful immunostain in SFT, though it is also expressed in dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP). In this case, the clinical and histopathologic findings best supported a diagnosis of SFT. Some consider hemangiopericytomas to be examples of SFTs; however, true hemangiopericytomas lack the thick hyalinized collagen and hypercellular areas seen in SFT.

A cellular dermatofibroma generally presents as a single round, reddish brown papule or nodule approximately 0.5 to 1 cm in diameter that is firm to palpation with a central depression or dimple created over the lesion from the lateral pressure. Cellular dermatofibromas mostly occur in middle-aged adults, with the most common locations on the legs and on the sides of the trunk. They are thought to arise after injuries to the skin. On histopathologic examination, cellular dermatofibromas typically exhibit a proliferation of fibrohistiocytic cells with collagen trapping, often at the periphery of the tumor (Figure 2). Although cellular dermatofibromas appear clinically different than SFTs, they often mimic SFTs histopathologically. Immunostaining also can be helpful in differentiating cellular dermatofibromas in which cells stain positive for factor XIIIa. CD34 staining is negative.

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans usually appears as one or multiple firm, red to violaceous nodules or plaques. They most often occur on the trunk in middle-aged adults. Histopathologically, DFSP presents with a dense, hypercellular, spindle cell proliferation that demonstrates a typical storiform pattern. The tumor generally infiltrates into the deep dermis and subcutaneous adipose layer with characteristic adipocyte entrapment (Figure 3). Positive CD34 and negative factor XIIIa staining helps to differentiate DFSP from a cellular dermatofibroma. Immunohistochemically, it is more difficult to distinguish DFSP from SFT, as both are CD34+ spindle cell neoplasms that also stain positive for CD99 and BCL-2.2 GRIA2 positivity also is seen in both SFT and DFSP.7 However, differentiation can be made on morphologic grounds alone, as DFSP has ill-defined tumor borders with adnexal and fat entrapment and SFT tends to be more circumscribed with prominent arborizing hyalinized vessels.8

Spindle cell lipoma (SCL) is an asymptomatic subcutaneous tumor commonly located on the back, neck, and shoulders in older patients, typically men. It often presents as a solitary lesion, though multiple lesions may occur. It is a well-circumscribed tumor of mature adipose tissue with areas of spindle cell proliferation and ropey collagen bundles (Figure 4). In early lesions, the spindle cell areas are myxoid with the presence of many mast cells.9 The spindle cells stain positive for CD34. Although spindle cell lipoma would be included in both the clinical and histopathologic differential diagnosis for SFT, its histopathologic features often are enough to differentiate SCL, which is highlighted by the aforementioned features as well as a relatively low cellularity and lack of ectatic vessels.8 However, discerning tumor variants, such as low-fat pseudoangiomatous SCL and lipomatous or myxoid SFT, might prove more challenging.

Nodular fasciitis typically presents as a rapidly growing subcutaneous nodule that may be tender. It is a benign reactive process usually affecting the arms and trunk of young to middle-aged adults, though it commonly involves the head and neck region in children.10 The tumor histopathologically appears as a well-circumscribed subcutaneous or fascial nodule with an angulated appearance. Spindle-shaped and stellate fibroblasts are loosely arranged in an edematous myxomatous stroma with a feathered appearance (Figure 5). Extravasated erythrocytes often are present. With time, collagen bundles become thicker and hyalinized. Immunohistochemical studies demonstrate positivity for vimentin, calponin, muscle-specific actin, and smooth muscle actin. Desmin, CD34, cytokeratin, and S-100 typically are negative.10-12 Therefore, CD34 staining is one of the main differentiating factors between nodular fasciitis and SFTs.

- Klemperer P, Rabin CB. Primary neoplasms of the pleura: a report of five cases. Arch Pathol. 1931;11:385-412.

- Erdag G, Qureshi HS, Patterson JW, et al. Solitary fibrous tumors of the skin: a clinicopathologic study of 10 cases and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2007;34:844-850.

- Okamura JM, Barr RJ, Battifora H. Solitary fibrous tumor of the skin. Am J Dermatopathol. 1997;19:515-518.

- Lee JY, Park SE, Shin SJ, et al. Solitary fibrous tumor with myxoid stromal change. Am J Dermatopathol. 2015;37:570-573.

- Geramizadeh B, Marzban M, Churg A. Role of immunohistochemistry in the diagnosis of solitary fibrous tumor, a review. Iran J Pathol. 2016;11:195-293.

- Creytens D, Ferdinande L, Dorpe JV. Histopathologically malignant solitary fibrous tumor of the skin: a report of an unusual case. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:629-631.

- Vivero M, Doyle LA, Fletcher CD, et al. GRIA2 is a novel diagnostic marker for solitary fibrous tumour identified through gene expression profiling. Histopathology. 2014;65:71-80.

- Wood L, Fountaine TJ, Rosamilia L, et al. Cutaneous CD34 spindle cell neoplasms: histopathologic features distinguish spindle cell lipoma, solitary fibrous tumor, and dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:764-768.

- Khatib Y, Khade AL, Shah VB, et al. Cytohistological features of spindle cell lipoma--a case report with differential diagnosis. J Clin Diagn Res. 2017;11:10-11.

- Kumar E, Patel NR, Demicco EG, et al. Cutaneous nodular fasciitis with genetic analysis: a case series. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:1143-1149.

- Bracey TS, Wharton S, Smith ME. Nodular 'fasciitis' presenting as a cutaneous polyp. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:980-982.

- Perez-Montiel MD, Plaza JA, Dominguez-Malagon H, et al. Differential expression of smooth muscle myosin, smooth muscle actin, h-caldesmon, and calponin in the diagnosis of myofibroblastic and smooth muscle lesions of skin and soft tissue. Am J Dermatopathol. 2006;28:105-111.

- Klemperer P, Rabin CB. Primary neoplasms of the pleura: a report of five cases. Arch Pathol. 1931;11:385-412.

- Erdag G, Qureshi HS, Patterson JW, et al. Solitary fibrous tumors of the skin: a clinicopathologic study of 10 cases and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2007;34:844-850.

- Okamura JM, Barr RJ, Battifora H. Solitary fibrous tumor of the skin. Am J Dermatopathol. 1997;19:515-518.

- Lee JY, Park SE, Shin SJ, et al. Solitary fibrous tumor with myxoid stromal change. Am J Dermatopathol. 2015;37:570-573.

- Geramizadeh B, Marzban M, Churg A. Role of immunohistochemistry in the diagnosis of solitary fibrous tumor, a review. Iran J Pathol. 2016;11:195-293.

- Creytens D, Ferdinande L, Dorpe JV. Histopathologically malignant solitary fibrous tumor of the skin: a report of an unusual case. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:629-631.

- Vivero M, Doyle LA, Fletcher CD, et al. GRIA2 is a novel diagnostic marker for solitary fibrous tumour identified through gene expression profiling. Histopathology. 2014;65:71-80.

- Wood L, Fountaine TJ, Rosamilia L, et al. Cutaneous CD34 spindle cell neoplasms: histopathologic features distinguish spindle cell lipoma, solitary fibrous tumor, and dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:764-768.

- Khatib Y, Khade AL, Shah VB, et al. Cytohistological features of spindle cell lipoma--a case report with differential diagnosis. J Clin Diagn Res. 2017;11:10-11.

- Kumar E, Patel NR, Demicco EG, et al. Cutaneous nodular fasciitis with genetic analysis: a case series. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:1143-1149.

- Bracey TS, Wharton S, Smith ME. Nodular 'fasciitis' presenting as a cutaneous polyp. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:980-982.

- Perez-Montiel MD, Plaza JA, Dominguez-Malagon H, et al. Differential expression of smooth muscle myosin, smooth muscle actin, h-caldesmon, and calponin in the diagnosis of myofibroblastic and smooth muscle lesions of skin and soft tissue. Am J Dermatopathol. 2006;28:105-111.

A 73-year-old man presented with a tender nodule on the back that had recently increased in size. On physical examination, a solitary 4-cm nodule was noted in the right trapezius region. The patient denied any personal or family history of similar lesions or a penchant for cysts. Due to the symptomatic nature of the lesion, surgical excision was performed.