User login

Thick Scaly Plaques on the Wrists, Knees, and Feet

The Diagnosis: Secondary Syphilis

Syphilis, known as the great mimicker, has a wide-ranging clinical and histologic presentation. There can be overlapping features with many of the entities included in the differential diagnoses. As our patient exemplifies, clinicians and pathologists must have a high index of suspicion, and any concerning features should lead to a more in-depth patient history, spirochete stains, and serologic testing.

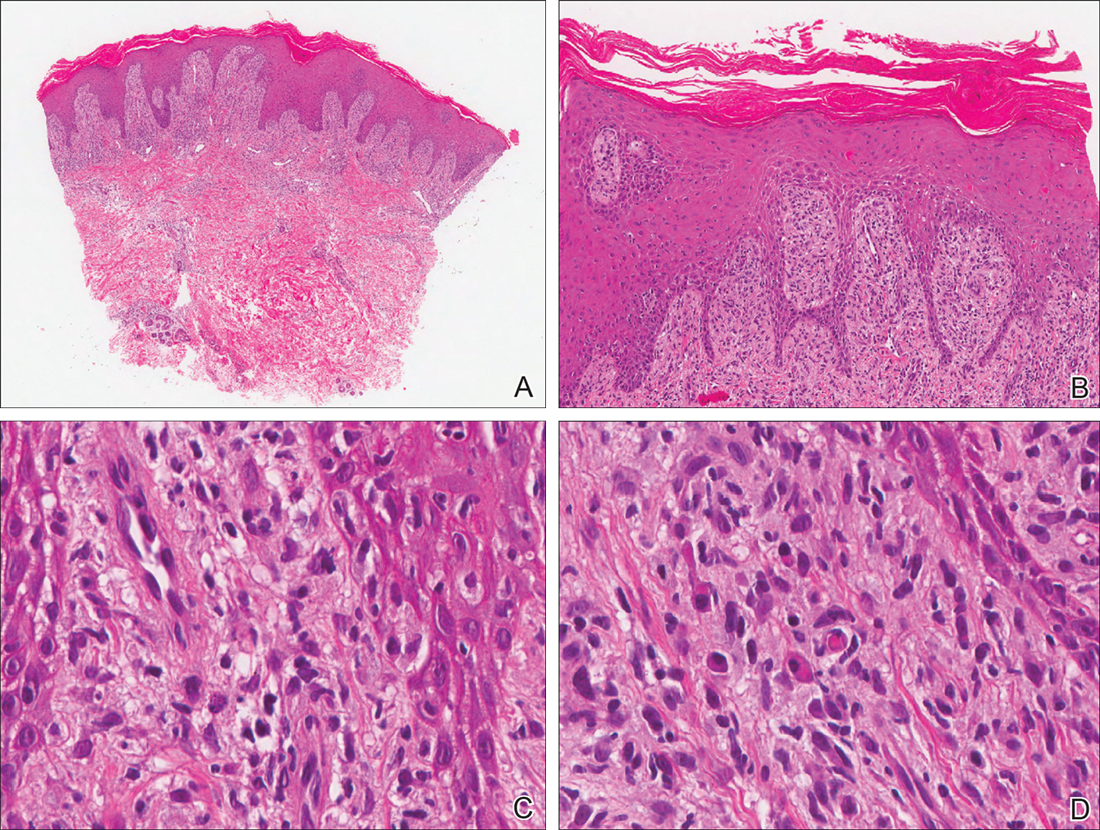

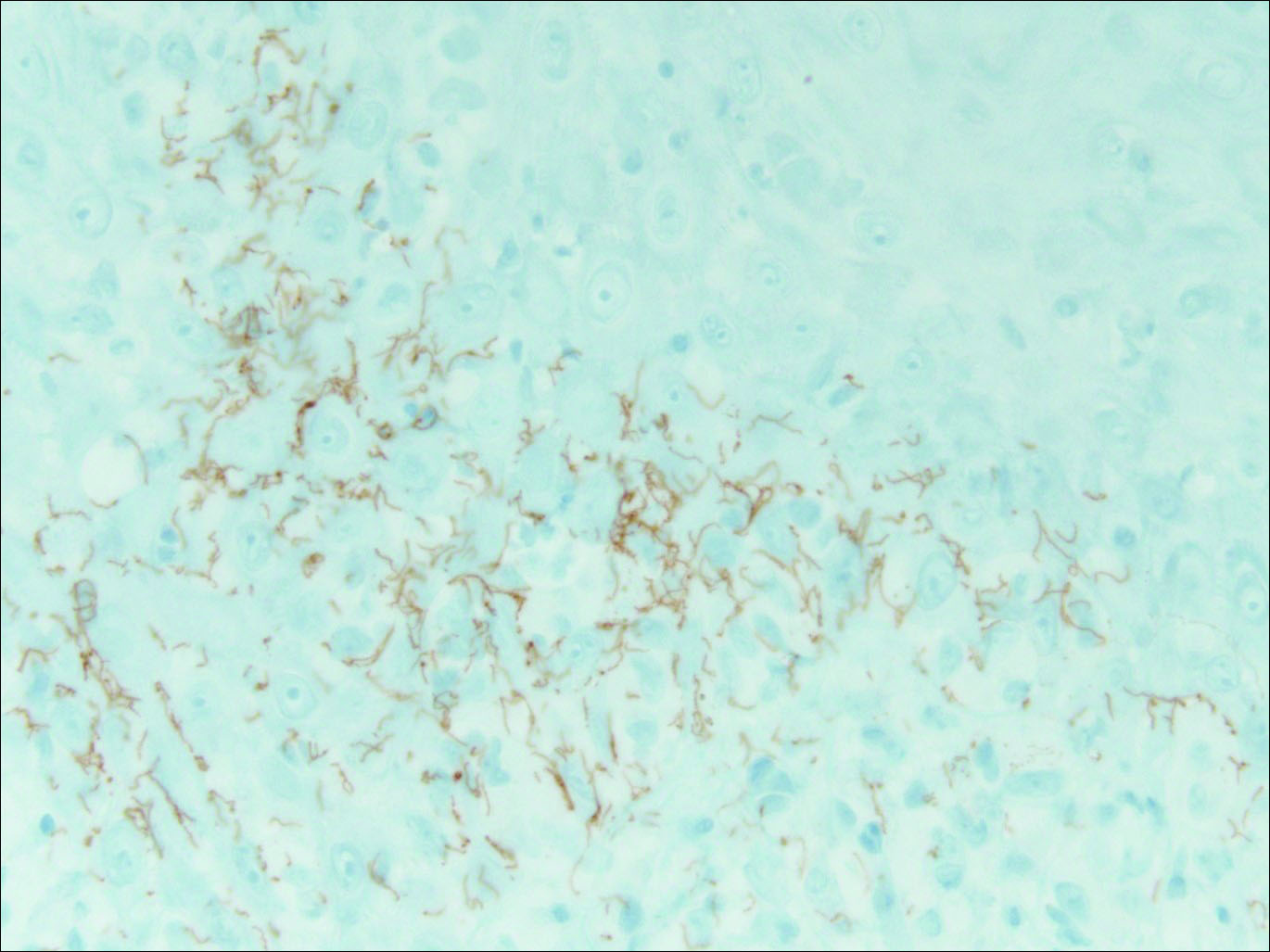

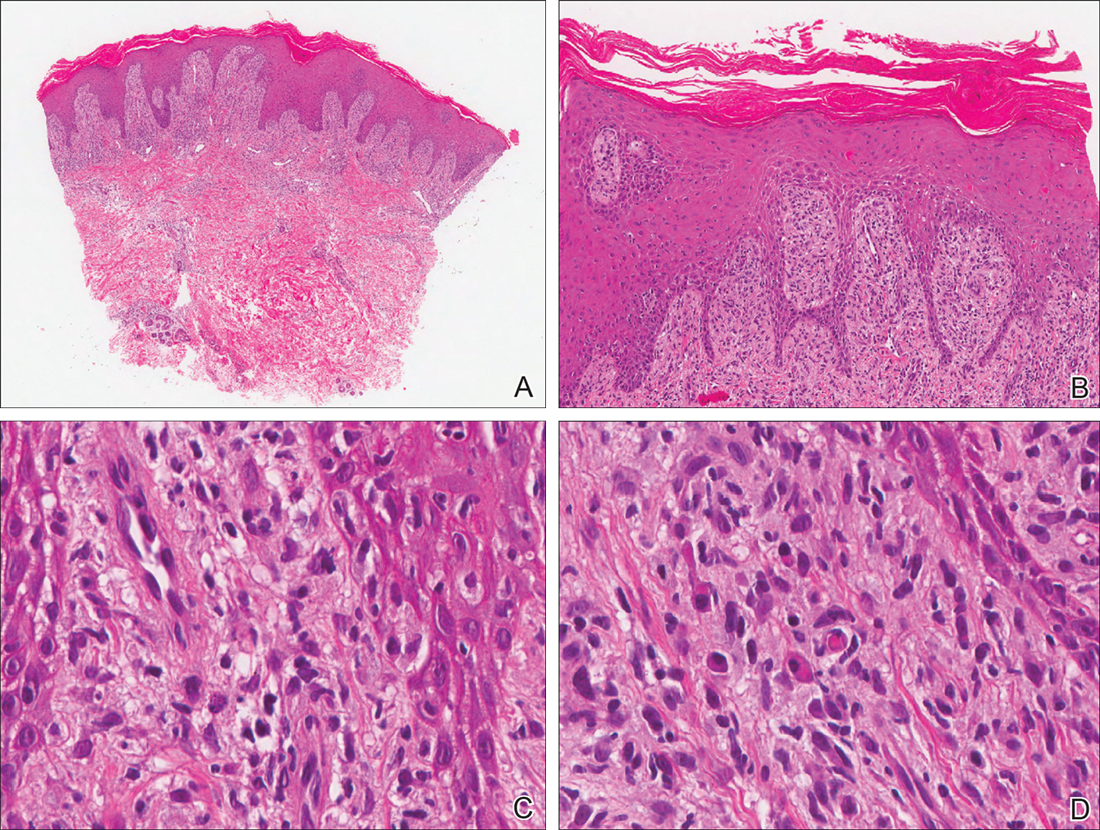

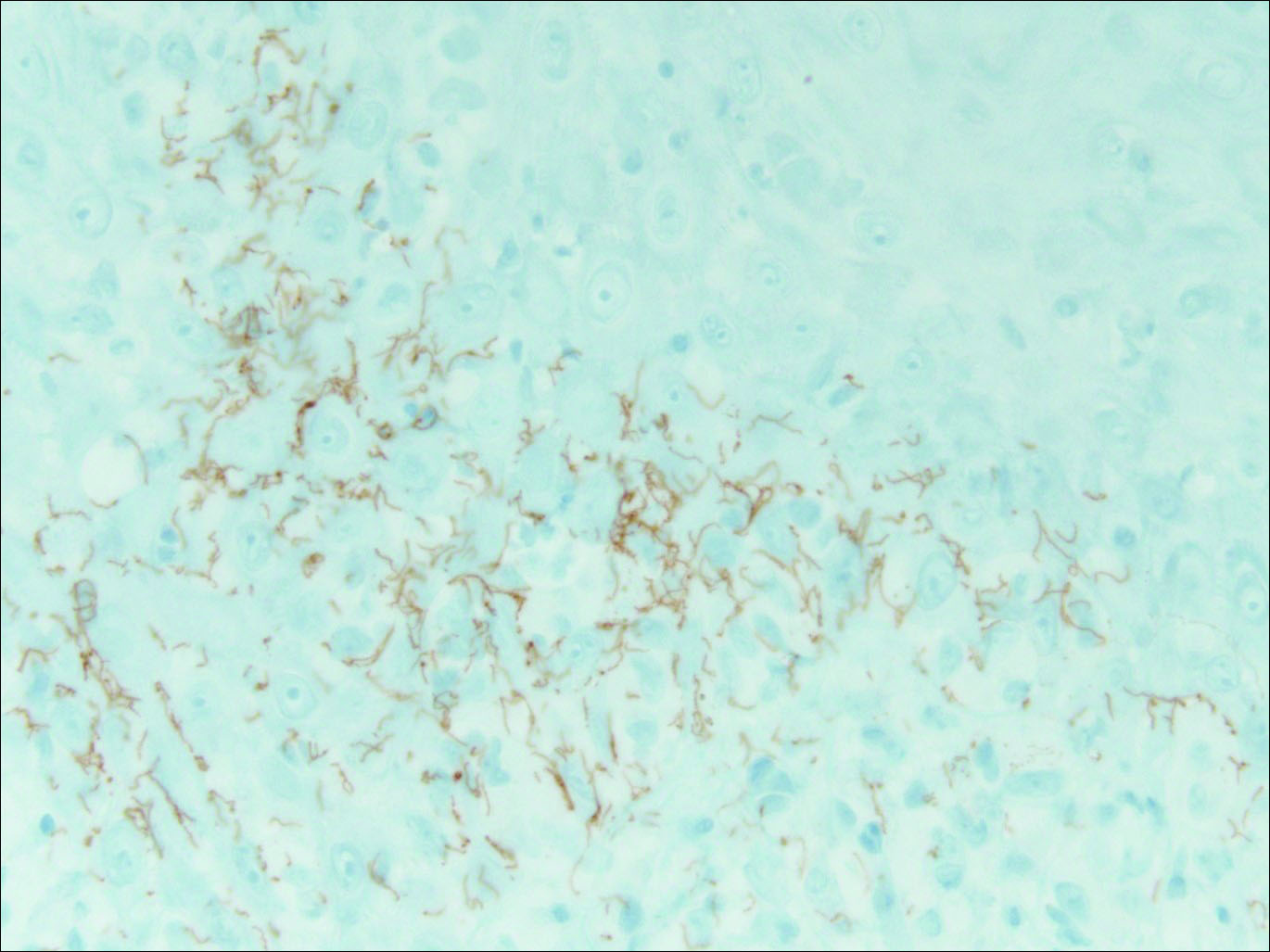

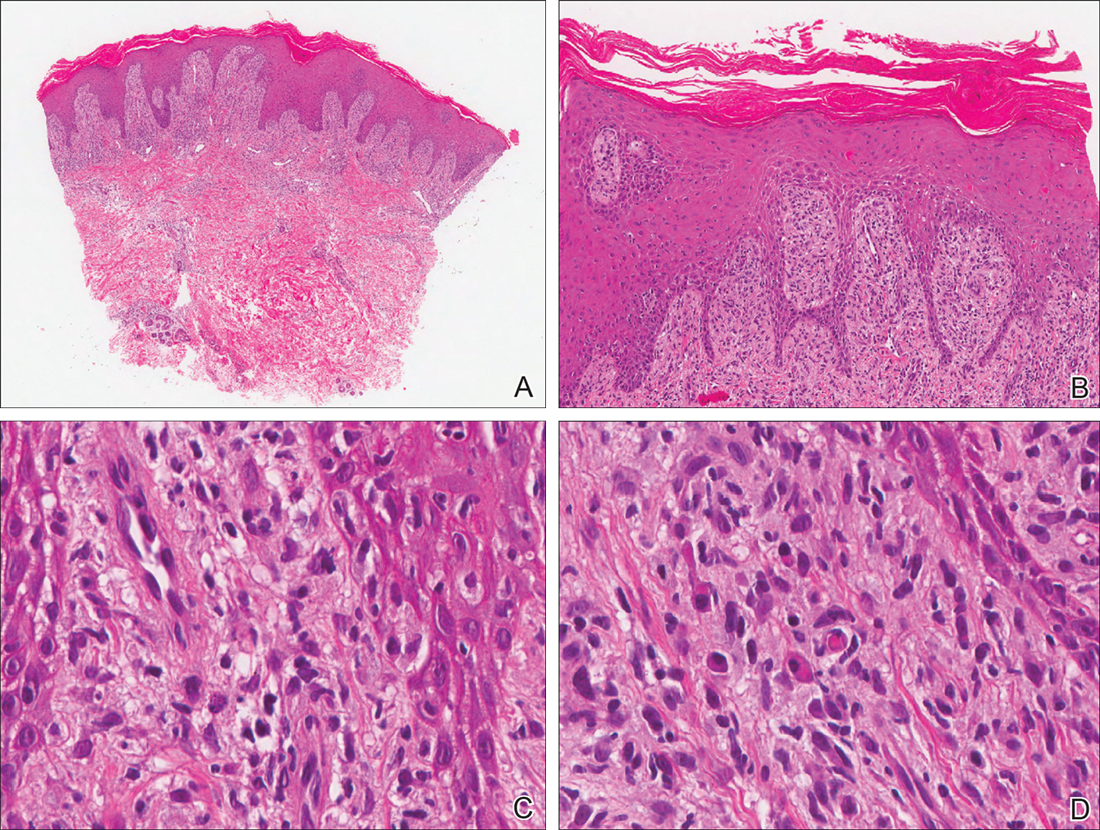

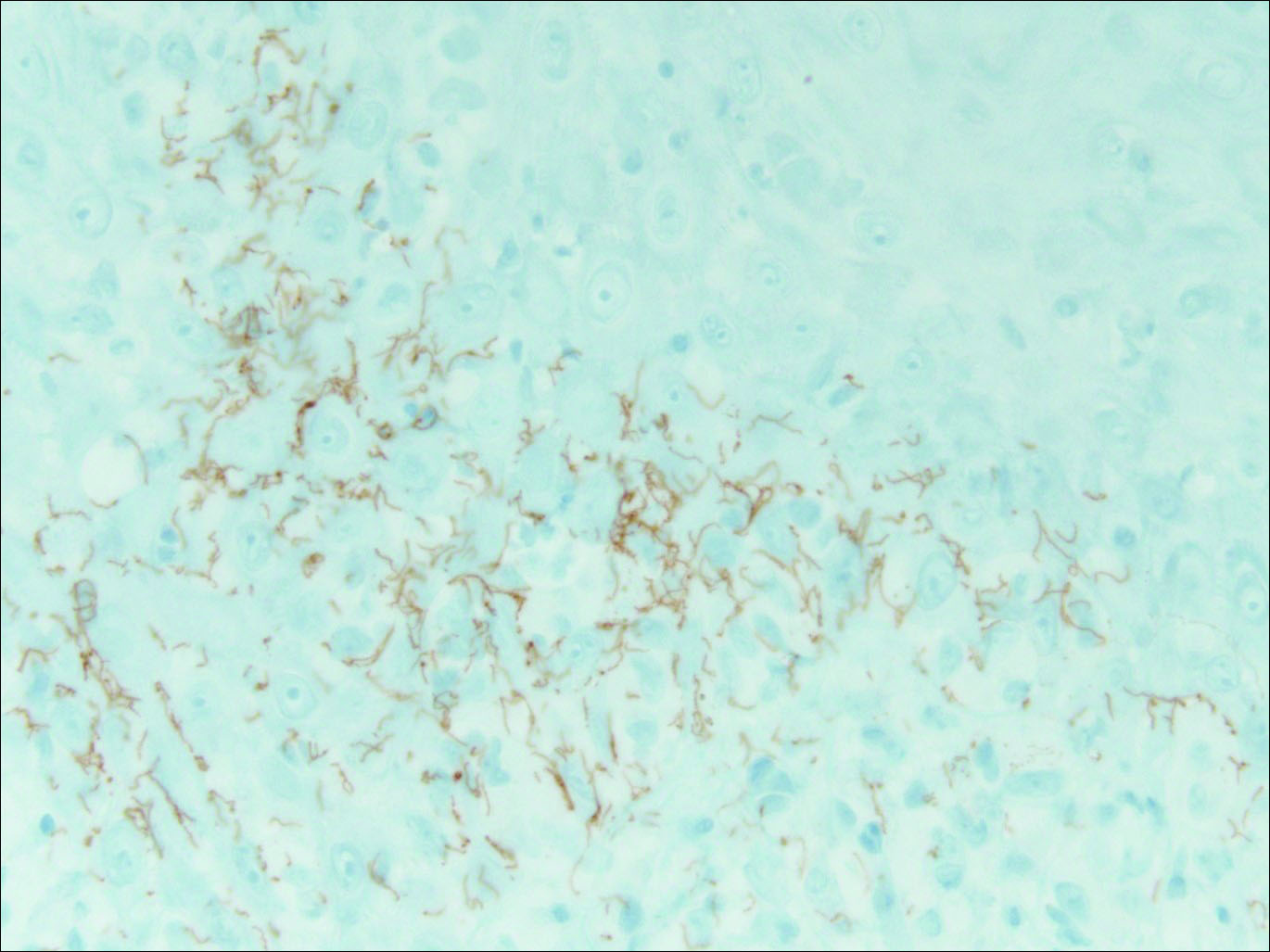

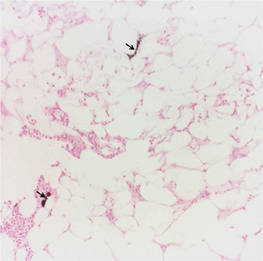

Our patient was seen by several dermatologists over the course of 2 years and therapy with topical steroids failed. He was eager to pursue more aggressive therapy with methotrexate, and a punch biopsy was performed to confirm the diagnosis of psoriasis prior to initiating treatment. Hematoxylin and eosin staining results on low power can be seen in Figure 1A. Medium-power view demonstrated vacuolar interface dermatitis (Figure 1B) with psoriasiform epidermal hyperplasia with slender elongation of rete ridges; neutrophils in the stratum corneum; endothelial cell swelling (Figure 1C); and mixed infiltrate with high plasma cells (Figure 1D), lymphocytes, and histiocytes. Although the biopsy results were psoriasiform, there was high suspicion for syphilis in this case. Additional staining for spirochetes was performed with syphilis immunohistochemical stain1 (Figure 2), which revealed spirochetes present on the patient's biopsy, confirming the diagnosis of syphilis. Warthin-Starry stain also can be performed to confirm the diagnosis.

Based on histologic features, the differential diagnosis includes psoriasis vulgaris, eczema, lichen planus, or lichenoid drug eruption. Psoriasis vulgaris displays regular psoriasiform epidermal hyperplasia with hypergranulosis and confluent parakeratosis. The elongated rete pegs are broad rather than slender.2 Neutrophils are present in the stratum corneum. In contrast, eczematous dermatitis is characterized by epidermal hyperplasia, spongiosis, parakeratosis, and eosinophils. Lichen planus classically displays a brisk bandlike lymphocytic infiltrate that closely abuts or obscures the dermoepidermal junction. Parakeratosis, neutrophils, and eosinophils should be absent. The rete pegs taper to a point, similar to a sawtooth, while they are long and slender with syphilis, similar to an ice pick. Although lichenoid drug eruption presents with interface dermatitis, parakeratosis, and eosinophils, the epidermis is hyperplastic without the slender elongation of rete pegs seen in syphilis.

Further workup with serologic testing demonstrated that the patient had a syphilis IgG titer of greater than 8.0 (reactive, >6.0), indicating the patient had been infected.3 Reactive syphilis IgG, a specific treponemal test, should be followed with a nontreponemal assay of either rapid plasma reagin (RPR) or VDRL test to confirm disease activity, according to recommendations from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention,4 which represents a change to the traditional algorithm that called for screening with a nontreponemal test and confirming with a specific treponemal test. The patient had a positive RPR and quantitative RPR titer was found as 1:2048, indicating that syphilis was active or recently treated. Testing for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) revealed a quantitative RNA polymerase chain reaction of 145,000 copies/mL and a CD4 count of 18 cells/µL (reference range, 533-1674 cells/µL).

The patient initially was treated for latent syphilis with 3 doses of intramuscular penicillin G benzathine 2.4 million U once weekly for 3 weeks. Due to his high RPR titers and low CD4 count, a lumbar puncture was later pursued, which revealed positive results from a cerebrospinal fluid (CSF)-VDRL test, confirming a diagnosis of neurosyphilis. Although a positive CSF-VDRL test is specific for the diagnosis of neurosyphilis, the sensitivity of the CSF-VDRL test against clinical diagnosis is only 30% to 70%.5 Intravenous aqueous penicillin G 4 million U every 4 hours was started for 14 days for neurosyphilis. One month following the completion of the intravenous penicillin, the rash completely resolved. The patient was in a 10-year monogamous relationship with a man and did not use condoms. Typically, signs and symptoms of secondary syphilis begin 4 to 10 weeks after the appearance of a chancre. However, the classic chancre of primary syphilis among men who have sex with men may go unnoticed in those who may not be able to see anal lesions.6 Also, infection with syphilis increases the likelihood of acquiring and transmitting HIV. All patients diagnosed with syphilis should have additional testing for HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases.

For patients with a history of thick scaly plaques on the wrists, knees, and feet resistant to topical steroid therapy, dermatologists should maintain a high index of clinical suspicion for syphilis.

- Toby M, White J, Van der Walt J. A new test for an old foe... spirochaete immunostaining in the diagnosis of syphilis. Sex Transm Infect. 2013;89:391.

- Nazzaro G, Boneschi V, Coggi A, et al. Syphilis with a lichen planus-like pattern (hypertrophic syphilis). J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:805-807.

- Yen-Lieberman B, Daniel J, Means C, et al. Identification of false-positive syphilis antibody results using a semiquantitative algorithm. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2011;18:1038-1040.

- Pope V. Use of syphilis test to screen for syphilis. Infect Med. 2004;21:399-404.

- Larsen S, Kraus S, Whittington W. Diagnostic tests. In: Larsen SA, Hunter E, Kraus S, eds. A Manual of Tests for Syphilis. Washington, DC: American Public Health Association; 1990:2-26.

- Golden MR, Marra CM, Holmes KK. Update on syphilis: resurgence of an old problem. JAMA. 2003;290:1510-1514.

The Diagnosis: Secondary Syphilis

Syphilis, known as the great mimicker, has a wide-ranging clinical and histologic presentation. There can be overlapping features with many of the entities included in the differential diagnoses. As our patient exemplifies, clinicians and pathologists must have a high index of suspicion, and any concerning features should lead to a more in-depth patient history, spirochete stains, and serologic testing.

Our patient was seen by several dermatologists over the course of 2 years and therapy with topical steroids failed. He was eager to pursue more aggressive therapy with methotrexate, and a punch biopsy was performed to confirm the diagnosis of psoriasis prior to initiating treatment. Hematoxylin and eosin staining results on low power can be seen in Figure 1A. Medium-power view demonstrated vacuolar interface dermatitis (Figure 1B) with psoriasiform epidermal hyperplasia with slender elongation of rete ridges; neutrophils in the stratum corneum; endothelial cell swelling (Figure 1C); and mixed infiltrate with high plasma cells (Figure 1D), lymphocytes, and histiocytes. Although the biopsy results were psoriasiform, there was high suspicion for syphilis in this case. Additional staining for spirochetes was performed with syphilis immunohistochemical stain1 (Figure 2), which revealed spirochetes present on the patient's biopsy, confirming the diagnosis of syphilis. Warthin-Starry stain also can be performed to confirm the diagnosis.

Based on histologic features, the differential diagnosis includes psoriasis vulgaris, eczema, lichen planus, or lichenoid drug eruption. Psoriasis vulgaris displays regular psoriasiform epidermal hyperplasia with hypergranulosis and confluent parakeratosis. The elongated rete pegs are broad rather than slender.2 Neutrophils are present in the stratum corneum. In contrast, eczematous dermatitis is characterized by epidermal hyperplasia, spongiosis, parakeratosis, and eosinophils. Lichen planus classically displays a brisk bandlike lymphocytic infiltrate that closely abuts or obscures the dermoepidermal junction. Parakeratosis, neutrophils, and eosinophils should be absent. The rete pegs taper to a point, similar to a sawtooth, while they are long and slender with syphilis, similar to an ice pick. Although lichenoid drug eruption presents with interface dermatitis, parakeratosis, and eosinophils, the epidermis is hyperplastic without the slender elongation of rete pegs seen in syphilis.

Further workup with serologic testing demonstrated that the patient had a syphilis IgG titer of greater than 8.0 (reactive, >6.0), indicating the patient had been infected.3 Reactive syphilis IgG, a specific treponemal test, should be followed with a nontreponemal assay of either rapid plasma reagin (RPR) or VDRL test to confirm disease activity, according to recommendations from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention,4 which represents a change to the traditional algorithm that called for screening with a nontreponemal test and confirming with a specific treponemal test. The patient had a positive RPR and quantitative RPR titer was found as 1:2048, indicating that syphilis was active or recently treated. Testing for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) revealed a quantitative RNA polymerase chain reaction of 145,000 copies/mL and a CD4 count of 18 cells/µL (reference range, 533-1674 cells/µL).

The patient initially was treated for latent syphilis with 3 doses of intramuscular penicillin G benzathine 2.4 million U once weekly for 3 weeks. Due to his high RPR titers and low CD4 count, a lumbar puncture was later pursued, which revealed positive results from a cerebrospinal fluid (CSF)-VDRL test, confirming a diagnosis of neurosyphilis. Although a positive CSF-VDRL test is specific for the diagnosis of neurosyphilis, the sensitivity of the CSF-VDRL test against clinical diagnosis is only 30% to 70%.5 Intravenous aqueous penicillin G 4 million U every 4 hours was started for 14 days for neurosyphilis. One month following the completion of the intravenous penicillin, the rash completely resolved. The patient was in a 10-year monogamous relationship with a man and did not use condoms. Typically, signs and symptoms of secondary syphilis begin 4 to 10 weeks after the appearance of a chancre. However, the classic chancre of primary syphilis among men who have sex with men may go unnoticed in those who may not be able to see anal lesions.6 Also, infection with syphilis increases the likelihood of acquiring and transmitting HIV. All patients diagnosed with syphilis should have additional testing for HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases.

For patients with a history of thick scaly plaques on the wrists, knees, and feet resistant to topical steroid therapy, dermatologists should maintain a high index of clinical suspicion for syphilis.

The Diagnosis: Secondary Syphilis

Syphilis, known as the great mimicker, has a wide-ranging clinical and histologic presentation. There can be overlapping features with many of the entities included in the differential diagnoses. As our patient exemplifies, clinicians and pathologists must have a high index of suspicion, and any concerning features should lead to a more in-depth patient history, spirochete stains, and serologic testing.

Our patient was seen by several dermatologists over the course of 2 years and therapy with topical steroids failed. He was eager to pursue more aggressive therapy with methotrexate, and a punch biopsy was performed to confirm the diagnosis of psoriasis prior to initiating treatment. Hematoxylin and eosin staining results on low power can be seen in Figure 1A. Medium-power view demonstrated vacuolar interface dermatitis (Figure 1B) with psoriasiform epidermal hyperplasia with slender elongation of rete ridges; neutrophils in the stratum corneum; endothelial cell swelling (Figure 1C); and mixed infiltrate with high plasma cells (Figure 1D), lymphocytes, and histiocytes. Although the biopsy results were psoriasiform, there was high suspicion for syphilis in this case. Additional staining for spirochetes was performed with syphilis immunohistochemical stain1 (Figure 2), which revealed spirochetes present on the patient's biopsy, confirming the diagnosis of syphilis. Warthin-Starry stain also can be performed to confirm the diagnosis.

Based on histologic features, the differential diagnosis includes psoriasis vulgaris, eczema, lichen planus, or lichenoid drug eruption. Psoriasis vulgaris displays regular psoriasiform epidermal hyperplasia with hypergranulosis and confluent parakeratosis. The elongated rete pegs are broad rather than slender.2 Neutrophils are present in the stratum corneum. In contrast, eczematous dermatitis is characterized by epidermal hyperplasia, spongiosis, parakeratosis, and eosinophils. Lichen planus classically displays a brisk bandlike lymphocytic infiltrate that closely abuts or obscures the dermoepidermal junction. Parakeratosis, neutrophils, and eosinophils should be absent. The rete pegs taper to a point, similar to a sawtooth, while they are long and slender with syphilis, similar to an ice pick. Although lichenoid drug eruption presents with interface dermatitis, parakeratosis, and eosinophils, the epidermis is hyperplastic without the slender elongation of rete pegs seen in syphilis.

Further workup with serologic testing demonstrated that the patient had a syphilis IgG titer of greater than 8.0 (reactive, >6.0), indicating the patient had been infected.3 Reactive syphilis IgG, a specific treponemal test, should be followed with a nontreponemal assay of either rapid plasma reagin (RPR) or VDRL test to confirm disease activity, according to recommendations from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention,4 which represents a change to the traditional algorithm that called for screening with a nontreponemal test and confirming with a specific treponemal test. The patient had a positive RPR and quantitative RPR titer was found as 1:2048, indicating that syphilis was active or recently treated. Testing for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) revealed a quantitative RNA polymerase chain reaction of 145,000 copies/mL and a CD4 count of 18 cells/µL (reference range, 533-1674 cells/µL).

The patient initially was treated for latent syphilis with 3 doses of intramuscular penicillin G benzathine 2.4 million U once weekly for 3 weeks. Due to his high RPR titers and low CD4 count, a lumbar puncture was later pursued, which revealed positive results from a cerebrospinal fluid (CSF)-VDRL test, confirming a diagnosis of neurosyphilis. Although a positive CSF-VDRL test is specific for the diagnosis of neurosyphilis, the sensitivity of the CSF-VDRL test against clinical diagnosis is only 30% to 70%.5 Intravenous aqueous penicillin G 4 million U every 4 hours was started for 14 days for neurosyphilis. One month following the completion of the intravenous penicillin, the rash completely resolved. The patient was in a 10-year monogamous relationship with a man and did not use condoms. Typically, signs and symptoms of secondary syphilis begin 4 to 10 weeks after the appearance of a chancre. However, the classic chancre of primary syphilis among men who have sex with men may go unnoticed in those who may not be able to see anal lesions.6 Also, infection with syphilis increases the likelihood of acquiring and transmitting HIV. All patients diagnosed with syphilis should have additional testing for HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases.

For patients with a history of thick scaly plaques on the wrists, knees, and feet resistant to topical steroid therapy, dermatologists should maintain a high index of clinical suspicion for syphilis.

- Toby M, White J, Van der Walt J. A new test for an old foe... spirochaete immunostaining in the diagnosis of syphilis. Sex Transm Infect. 2013;89:391.

- Nazzaro G, Boneschi V, Coggi A, et al. Syphilis with a lichen planus-like pattern (hypertrophic syphilis). J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:805-807.

- Yen-Lieberman B, Daniel J, Means C, et al. Identification of false-positive syphilis antibody results using a semiquantitative algorithm. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2011;18:1038-1040.

- Pope V. Use of syphilis test to screen for syphilis. Infect Med. 2004;21:399-404.

- Larsen S, Kraus S, Whittington W. Diagnostic tests. In: Larsen SA, Hunter E, Kraus S, eds. A Manual of Tests for Syphilis. Washington, DC: American Public Health Association; 1990:2-26.

- Golden MR, Marra CM, Holmes KK. Update on syphilis: resurgence of an old problem. JAMA. 2003;290:1510-1514.

- Toby M, White J, Van der Walt J. A new test for an old foe... spirochaete immunostaining in the diagnosis of syphilis. Sex Transm Infect. 2013;89:391.

- Nazzaro G, Boneschi V, Coggi A, et al. Syphilis with a lichen planus-like pattern (hypertrophic syphilis). J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:805-807.

- Yen-Lieberman B, Daniel J, Means C, et al. Identification of false-positive syphilis antibody results using a semiquantitative algorithm. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2011;18:1038-1040.

- Pope V. Use of syphilis test to screen for syphilis. Infect Med. 2004;21:399-404.

- Larsen S, Kraus S, Whittington W. Diagnostic tests. In: Larsen SA, Hunter E, Kraus S, eds. A Manual of Tests for Syphilis. Washington, DC: American Public Health Association; 1990:2-26.

- Golden MR, Marra CM, Holmes KK. Update on syphilis: resurgence of an old problem. JAMA. 2003;290:1510-1514.

A 34-year-old man presented with thick scaly plaques on the wrists, knees, and feet of 2 years' duration. He had seen several dermatologists, and despite the use of topical steroids, he had no improvement.

What Is Your Diagnosis? Calciphylaxis

A 62-year-old woman who was obese with idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura; a history of diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and acute renal insufficiency; recent treatment with high-dose (2 mg/kg) glucocorticosteroids; and sepsis presented with ulcers on the thighs and buttocks after being transferred in a patient lift. The ulcers had developed in areas of pressure corresponding to placement in the patient lift.

The Diagnosis: Calciphylaxis

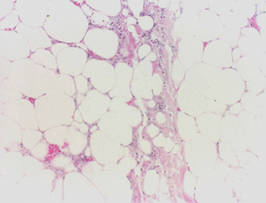

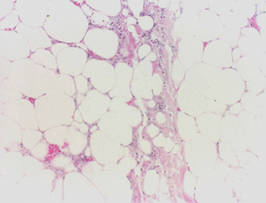

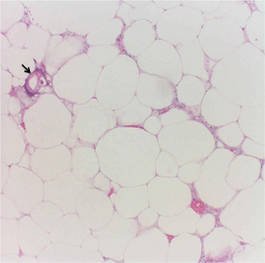

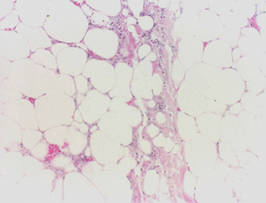

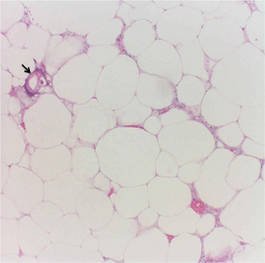

Calciphylaxis is a rare disorder that most commonly affects patients with impaired renal failure. Calciphylaxis, known as calcific uremic arteriolopathy,1,2 involves calcification of small- and medium-sized blood vessels,3 which may lead to necrosis of the dermis, subcutaneous tissue, muscles, fascia, and internal organs.4-6 Calciphylaxis usually occurs in fatty areas such as the calves, thighs (Figure 1), abdomen, and buttocks.3,7,8 Although calciphylaxis most commonly is associated with severe renal disease,1,3 pharmacologic agents such as glucocorticoids, high-dose vitamin D, warfarin, iron salts, insulin injections, calcium-based phosphate binders, and chemotherapeutic agents also may precipitate this condition.9,10 Diagnostic biopsies typically reveal fat necrosis, inflammation, and associated small vessel calcification (Figures 2 and 3).

Our patient may have been predisposed to calciphylaxis due to her history of obesity, diabetes mellitus, and hypertension, and recent high-dose (2 mg/kg) glucocorticosteroid treatment. Five months prior to the current presentation, the patient was admitted to the hospital for treatment of sepsis with high-dose glucocorticoids for presumed idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. She also developed several ecchymotic regions on her skin at that time. Additionally, she developed acute renal insufficiency resulting from septic shock that improved over several weeks. Interestingly, 2 months after full recovery of her renal function, which was marked by normal creatinine levels and glomerular filtration rate, she developed a violaceous rash over the thighs and buttocks in the distribution of the straps from a patient lift that was used to transfer her from a bed into a wheelchair while residing at a physical rehabilitation facility. In the time after recovery of renal function, the eruption progressed to necrosis over 2 weeks in the areas of skin that came into contact with the lift’s straps. The patient’s renal function and parathyroid hormone, ionized calcium, phosphate, and vitamin D levels were all within reference range at the time of diagnosis.

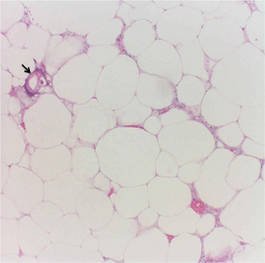

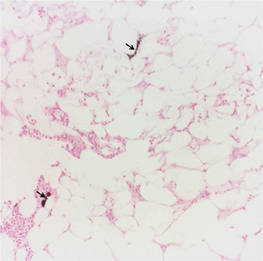

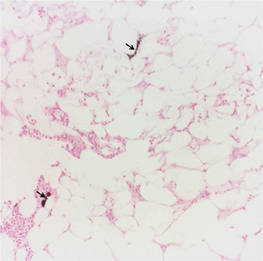

On biopsy, characteristic findings established the diagnosis of calciphylaxis. Furthermore, the pattern of ulceration in pressure areas associated with the patient lift indicated that infection was not the precipitating event. A von Kossa stain highlighted the calcium deposition in small blood vessels in areas of panniculitis (Figure 4). Atherosclerosis may be associated with vascular calcification but does not involve acute small blood vessel calcification, and other ulcerative disorders in the differential diagnosis (eg, pyoderma gangrenosum) would not be associated with small vessel vasculitis.

Treatment of calciphylaxis must be individualized. It is important to treat any underlying disease and remove any precipitating factors. In the case of severe renal disease, a multidisciplinary approach typically is necessary.3 Correction of serum calcium and phosphate levels, rapid and safe rehydration, dialysis, and intravenous bisphosphonates all may be needed in patients with chronic kidney disease.11 Surgical management of the nonhealing necrotic skin lesions via surgical debridement and skin grafting has been reported to improve overall morbidity and survival rates.12 For patients with calciphylaxis from hyperparathyroidism, parathyroidectomy has been used but has demonstrated minimal effects on survival rates.9 Currently, there is no standard therapy in place for treatment of calciphylaxis but several are under investigation. Most notably, sodium thiosulfate, an inorganic salt that promotes dissolution of calcium deposits by chelating calcium, has shown rapid improvement when other treatments have failed.13-16 In patients with marginal decreases in blood flow and ischemia of skin, hyperbaric oxygen therapy has been found to resolve cutaneous ulcers of calciphylaxis.17,18 Patients with renal disease who develop calciphylaxis have benefited from treatment with cinacalcet, a calcimemetic that lowers parathyroid hormone levels and improves calcium phosphorus metabolism in patients undergoing dialysis.13,14

Our patient was treated with 2 weeks of broad-spectrum antibiotics along with extensive wound care and vacuum-assisted closure of surgically debrided tissue on her thighs and buttocks. Glucocorticoid therapy was rapidly tapered. Three months after the initial presentation, the patient was placed in outpatient wound care with evaluation for hyperbaric oxygen therapy.

Calciphylaxis is a rare condition with a high mortality rate, most often due to septicemia from secondary infection of skin lesions.19 The exact pathogenic mechanisms are vague but may be the result of several precipitating factors.10 Local wound care and therapeutics should be used synergistically and individualized for each patient with calciphylaxis.

- Brandenburg VM, Cozzolino M, Ketteler M. Calciphylaxis: a still unmet challenge. J Nephrol. 2011;24:142-148.

- Hafner J, Keusch G, Wahl C, et al. Uremic small-artery disease with medial calcification and intimal hyperplasia (so-called calciphylaxis): a complication of chronic renal failure and benefit from parathyroidectomy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33:954-962.

- Ng AT, Peng DH. Calciphylaxis. Dermatol Ther. 2011;24:256-262.

- Ahmed S, O’Neill KD, Hood AF, et al. Calciphylaxis associated with hyperphosphatemia and increased osteopontin expression by vascular smooth muscle cells. Am J Kidney Dis. 2001;37:1267-1276.

- Bleyer AJ, Choi M, Igwemezie B, et al. A case control study of proximal calciphylaxis. Am J Kidney Dis. 1998;32:376-383.

- Mazhar AR, Johnson RJ, Gillen D, et al. Risk factors and mortality associated with calciphylaxis in end-stage renal disease. Kidney Int. 2001;60:324-332.

- Scheinman PL, Helm KF, Fairley JA. Acral necrosis in a patient with chronic renal failure. calciphylaxis. Arch Dermatol. 1991;127:248-249, 251-252.

- Hafner J, Keusch G, Wahl C, et al. Calciphylaxis: a syndrome of skin necrosis and acral gangrene in chronic renal failure. Vasa. 1998;27:137-143.

- Weenig RH, Sewell LD, Davis MD, et al. Calciphylaxis: natural history, risk factor analysis, and outcome [published online ahead of print December 1, 2006]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:569-579.

- Guldbakke KK, Khachemoune A. Calciphylaxis. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46:231-238.

- Hanafusa T, Yamaguchi Y, Tani M, et al. Intractable wounds caused by calcific uremic arteriolopathy treated with bisphosphonates. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:1021-1025.

- Janigan DT, Hirsch DJ, Klassen GA, et al. Calcified subcutaneous arterioles with infarcts of the subcutis and skin (“calciphylaxis”) in chronic renal failure. Am J Kidney Dis. 2000;35:588-597.

- Robinson MR, Augustine JJ, Korman NJ. Cinacalcet for the treatment of calciphylaxis. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:152-154.

- Sharma A, Burkitt-Wright E, Rustom R. Cinacalcet as an adjunct in successful treatment of calciphylaxis. Br J Dermatol. 2006;155:1295-1297.

- Cicone JS, Petronis JB, Embert CD, et al. Successful treatment of calciphylaxis with intravenous sodium thiosulfate. Am J Kidney Dis. 2004;43:1104-1108.

- Guerra G, Shah RC, Ross EA. Rapid resolution of calciphylaxis with intravenous sodium thiosulfate and continuous venovenous haemofiltration using low calcium replacement fluid: case report [published online ahead of print May 3, 2005]. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2005;20:1260-1262.

- Podymow T, Wherrett C, Burns KD. Hyperbaricoxygen in the treatment of calciphylaxis: a case series. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2001;16:2176-2180.

- Basile C, Montanaro A, Masi M, et al. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy for calcific uremic arteriolopathy: a case series. J Nephrol. 2002;15:676-680.

- Fine A, Zacharias J. Calciphylaxis is usually non-ulcerating: risk factors, outcome and therapy. Kidney Int. 2002;61:2210-2217.

A 62-year-old woman who was obese with idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura; a history of diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and acute renal insufficiency; recent treatment with high-dose (2 mg/kg) glucocorticosteroids; and sepsis presented with ulcers on the thighs and buttocks after being transferred in a patient lift. The ulcers had developed in areas of pressure corresponding to placement in the patient lift.

The Diagnosis: Calciphylaxis

Calciphylaxis is a rare disorder that most commonly affects patients with impaired renal failure. Calciphylaxis, known as calcific uremic arteriolopathy,1,2 involves calcification of small- and medium-sized blood vessels,3 which may lead to necrosis of the dermis, subcutaneous tissue, muscles, fascia, and internal organs.4-6 Calciphylaxis usually occurs in fatty areas such as the calves, thighs (Figure 1), abdomen, and buttocks.3,7,8 Although calciphylaxis most commonly is associated with severe renal disease,1,3 pharmacologic agents such as glucocorticoids, high-dose vitamin D, warfarin, iron salts, insulin injections, calcium-based phosphate binders, and chemotherapeutic agents also may precipitate this condition.9,10 Diagnostic biopsies typically reveal fat necrosis, inflammation, and associated small vessel calcification (Figures 2 and 3).

Our patient may have been predisposed to calciphylaxis due to her history of obesity, diabetes mellitus, and hypertension, and recent high-dose (2 mg/kg) glucocorticosteroid treatment. Five months prior to the current presentation, the patient was admitted to the hospital for treatment of sepsis with high-dose glucocorticoids for presumed idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. She also developed several ecchymotic regions on her skin at that time. Additionally, she developed acute renal insufficiency resulting from septic shock that improved over several weeks. Interestingly, 2 months after full recovery of her renal function, which was marked by normal creatinine levels and glomerular filtration rate, she developed a violaceous rash over the thighs and buttocks in the distribution of the straps from a patient lift that was used to transfer her from a bed into a wheelchair while residing at a physical rehabilitation facility. In the time after recovery of renal function, the eruption progressed to necrosis over 2 weeks in the areas of skin that came into contact with the lift’s straps. The patient’s renal function and parathyroid hormone, ionized calcium, phosphate, and vitamin D levels were all within reference range at the time of diagnosis.

On biopsy, characteristic findings established the diagnosis of calciphylaxis. Furthermore, the pattern of ulceration in pressure areas associated with the patient lift indicated that infection was not the precipitating event. A von Kossa stain highlighted the calcium deposition in small blood vessels in areas of panniculitis (Figure 4). Atherosclerosis may be associated with vascular calcification but does not involve acute small blood vessel calcification, and other ulcerative disorders in the differential diagnosis (eg, pyoderma gangrenosum) would not be associated with small vessel vasculitis.

Treatment of calciphylaxis must be individualized. It is important to treat any underlying disease and remove any precipitating factors. In the case of severe renal disease, a multidisciplinary approach typically is necessary.3 Correction of serum calcium and phosphate levels, rapid and safe rehydration, dialysis, and intravenous bisphosphonates all may be needed in patients with chronic kidney disease.11 Surgical management of the nonhealing necrotic skin lesions via surgical debridement and skin grafting has been reported to improve overall morbidity and survival rates.12 For patients with calciphylaxis from hyperparathyroidism, parathyroidectomy has been used but has demonstrated minimal effects on survival rates.9 Currently, there is no standard therapy in place for treatment of calciphylaxis but several are under investigation. Most notably, sodium thiosulfate, an inorganic salt that promotes dissolution of calcium deposits by chelating calcium, has shown rapid improvement when other treatments have failed.13-16 In patients with marginal decreases in blood flow and ischemia of skin, hyperbaric oxygen therapy has been found to resolve cutaneous ulcers of calciphylaxis.17,18 Patients with renal disease who develop calciphylaxis have benefited from treatment with cinacalcet, a calcimemetic that lowers parathyroid hormone levels and improves calcium phosphorus metabolism in patients undergoing dialysis.13,14

Our patient was treated with 2 weeks of broad-spectrum antibiotics along with extensive wound care and vacuum-assisted closure of surgically debrided tissue on her thighs and buttocks. Glucocorticoid therapy was rapidly tapered. Three months after the initial presentation, the patient was placed in outpatient wound care with evaluation for hyperbaric oxygen therapy.

Calciphylaxis is a rare condition with a high mortality rate, most often due to septicemia from secondary infection of skin lesions.19 The exact pathogenic mechanisms are vague but may be the result of several precipitating factors.10 Local wound care and therapeutics should be used synergistically and individualized for each patient with calciphylaxis.

A 62-year-old woman who was obese with idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura; a history of diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and acute renal insufficiency; recent treatment with high-dose (2 mg/kg) glucocorticosteroids; and sepsis presented with ulcers on the thighs and buttocks after being transferred in a patient lift. The ulcers had developed in areas of pressure corresponding to placement in the patient lift.

The Diagnosis: Calciphylaxis

Calciphylaxis is a rare disorder that most commonly affects patients with impaired renal failure. Calciphylaxis, known as calcific uremic arteriolopathy,1,2 involves calcification of small- and medium-sized blood vessels,3 which may lead to necrosis of the dermis, subcutaneous tissue, muscles, fascia, and internal organs.4-6 Calciphylaxis usually occurs in fatty areas such as the calves, thighs (Figure 1), abdomen, and buttocks.3,7,8 Although calciphylaxis most commonly is associated with severe renal disease,1,3 pharmacologic agents such as glucocorticoids, high-dose vitamin D, warfarin, iron salts, insulin injections, calcium-based phosphate binders, and chemotherapeutic agents also may precipitate this condition.9,10 Diagnostic biopsies typically reveal fat necrosis, inflammation, and associated small vessel calcification (Figures 2 and 3).

Our patient may have been predisposed to calciphylaxis due to her history of obesity, diabetes mellitus, and hypertension, and recent high-dose (2 mg/kg) glucocorticosteroid treatment. Five months prior to the current presentation, the patient was admitted to the hospital for treatment of sepsis with high-dose glucocorticoids for presumed idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. She also developed several ecchymotic regions on her skin at that time. Additionally, she developed acute renal insufficiency resulting from septic shock that improved over several weeks. Interestingly, 2 months after full recovery of her renal function, which was marked by normal creatinine levels and glomerular filtration rate, she developed a violaceous rash over the thighs and buttocks in the distribution of the straps from a patient lift that was used to transfer her from a bed into a wheelchair while residing at a physical rehabilitation facility. In the time after recovery of renal function, the eruption progressed to necrosis over 2 weeks in the areas of skin that came into contact with the lift’s straps. The patient’s renal function and parathyroid hormone, ionized calcium, phosphate, and vitamin D levels were all within reference range at the time of diagnosis.

On biopsy, characteristic findings established the diagnosis of calciphylaxis. Furthermore, the pattern of ulceration in pressure areas associated with the patient lift indicated that infection was not the precipitating event. A von Kossa stain highlighted the calcium deposition in small blood vessels in areas of panniculitis (Figure 4). Atherosclerosis may be associated with vascular calcification but does not involve acute small blood vessel calcification, and other ulcerative disorders in the differential diagnosis (eg, pyoderma gangrenosum) would not be associated with small vessel vasculitis.

Treatment of calciphylaxis must be individualized. It is important to treat any underlying disease and remove any precipitating factors. In the case of severe renal disease, a multidisciplinary approach typically is necessary.3 Correction of serum calcium and phosphate levels, rapid and safe rehydration, dialysis, and intravenous bisphosphonates all may be needed in patients with chronic kidney disease.11 Surgical management of the nonhealing necrotic skin lesions via surgical debridement and skin grafting has been reported to improve overall morbidity and survival rates.12 For patients with calciphylaxis from hyperparathyroidism, parathyroidectomy has been used but has demonstrated minimal effects on survival rates.9 Currently, there is no standard therapy in place for treatment of calciphylaxis but several are under investigation. Most notably, sodium thiosulfate, an inorganic salt that promotes dissolution of calcium deposits by chelating calcium, has shown rapid improvement when other treatments have failed.13-16 In patients with marginal decreases in blood flow and ischemia of skin, hyperbaric oxygen therapy has been found to resolve cutaneous ulcers of calciphylaxis.17,18 Patients with renal disease who develop calciphylaxis have benefited from treatment with cinacalcet, a calcimemetic that lowers parathyroid hormone levels and improves calcium phosphorus metabolism in patients undergoing dialysis.13,14

Our patient was treated with 2 weeks of broad-spectrum antibiotics along with extensive wound care and vacuum-assisted closure of surgically debrided tissue on her thighs and buttocks. Glucocorticoid therapy was rapidly tapered. Three months after the initial presentation, the patient was placed in outpatient wound care with evaluation for hyperbaric oxygen therapy.

Calciphylaxis is a rare condition with a high mortality rate, most often due to septicemia from secondary infection of skin lesions.19 The exact pathogenic mechanisms are vague but may be the result of several precipitating factors.10 Local wound care and therapeutics should be used synergistically and individualized for each patient with calciphylaxis.

- Brandenburg VM, Cozzolino M, Ketteler M. Calciphylaxis: a still unmet challenge. J Nephrol. 2011;24:142-148.

- Hafner J, Keusch G, Wahl C, et al. Uremic small-artery disease with medial calcification and intimal hyperplasia (so-called calciphylaxis): a complication of chronic renal failure and benefit from parathyroidectomy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33:954-962.

- Ng AT, Peng DH. Calciphylaxis. Dermatol Ther. 2011;24:256-262.

- Ahmed S, O’Neill KD, Hood AF, et al. Calciphylaxis associated with hyperphosphatemia and increased osteopontin expression by vascular smooth muscle cells. Am J Kidney Dis. 2001;37:1267-1276.

- Bleyer AJ, Choi M, Igwemezie B, et al. A case control study of proximal calciphylaxis. Am J Kidney Dis. 1998;32:376-383.

- Mazhar AR, Johnson RJ, Gillen D, et al. Risk factors and mortality associated with calciphylaxis in end-stage renal disease. Kidney Int. 2001;60:324-332.

- Scheinman PL, Helm KF, Fairley JA. Acral necrosis in a patient with chronic renal failure. calciphylaxis. Arch Dermatol. 1991;127:248-249, 251-252.

- Hafner J, Keusch G, Wahl C, et al. Calciphylaxis: a syndrome of skin necrosis and acral gangrene in chronic renal failure. Vasa. 1998;27:137-143.

- Weenig RH, Sewell LD, Davis MD, et al. Calciphylaxis: natural history, risk factor analysis, and outcome [published online ahead of print December 1, 2006]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:569-579.

- Guldbakke KK, Khachemoune A. Calciphylaxis. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46:231-238.

- Hanafusa T, Yamaguchi Y, Tani M, et al. Intractable wounds caused by calcific uremic arteriolopathy treated with bisphosphonates. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:1021-1025.

- Janigan DT, Hirsch DJ, Klassen GA, et al. Calcified subcutaneous arterioles with infarcts of the subcutis and skin (“calciphylaxis”) in chronic renal failure. Am J Kidney Dis. 2000;35:588-597.

- Robinson MR, Augustine JJ, Korman NJ. Cinacalcet for the treatment of calciphylaxis. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:152-154.

- Sharma A, Burkitt-Wright E, Rustom R. Cinacalcet as an adjunct in successful treatment of calciphylaxis. Br J Dermatol. 2006;155:1295-1297.

- Cicone JS, Petronis JB, Embert CD, et al. Successful treatment of calciphylaxis with intravenous sodium thiosulfate. Am J Kidney Dis. 2004;43:1104-1108.

- Guerra G, Shah RC, Ross EA. Rapid resolution of calciphylaxis with intravenous sodium thiosulfate and continuous venovenous haemofiltration using low calcium replacement fluid: case report [published online ahead of print May 3, 2005]. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2005;20:1260-1262.

- Podymow T, Wherrett C, Burns KD. Hyperbaricoxygen in the treatment of calciphylaxis: a case series. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2001;16:2176-2180.

- Basile C, Montanaro A, Masi M, et al. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy for calcific uremic arteriolopathy: a case series. J Nephrol. 2002;15:676-680.

- Fine A, Zacharias J. Calciphylaxis is usually non-ulcerating: risk factors, outcome and therapy. Kidney Int. 2002;61:2210-2217.

- Brandenburg VM, Cozzolino M, Ketteler M. Calciphylaxis: a still unmet challenge. J Nephrol. 2011;24:142-148.

- Hafner J, Keusch G, Wahl C, et al. Uremic small-artery disease with medial calcification and intimal hyperplasia (so-called calciphylaxis): a complication of chronic renal failure and benefit from parathyroidectomy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33:954-962.

- Ng AT, Peng DH. Calciphylaxis. Dermatol Ther. 2011;24:256-262.

- Ahmed S, O’Neill KD, Hood AF, et al. Calciphylaxis associated with hyperphosphatemia and increased osteopontin expression by vascular smooth muscle cells. Am J Kidney Dis. 2001;37:1267-1276.

- Bleyer AJ, Choi M, Igwemezie B, et al. A case control study of proximal calciphylaxis. Am J Kidney Dis. 1998;32:376-383.

- Mazhar AR, Johnson RJ, Gillen D, et al. Risk factors and mortality associated with calciphylaxis in end-stage renal disease. Kidney Int. 2001;60:324-332.

- Scheinman PL, Helm KF, Fairley JA. Acral necrosis in a patient with chronic renal failure. calciphylaxis. Arch Dermatol. 1991;127:248-249, 251-252.

- Hafner J, Keusch G, Wahl C, et al. Calciphylaxis: a syndrome of skin necrosis and acral gangrene in chronic renal failure. Vasa. 1998;27:137-143.

- Weenig RH, Sewell LD, Davis MD, et al. Calciphylaxis: natural history, risk factor analysis, and outcome [published online ahead of print December 1, 2006]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:569-579.

- Guldbakke KK, Khachemoune A. Calciphylaxis. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46:231-238.

- Hanafusa T, Yamaguchi Y, Tani M, et al. Intractable wounds caused by calcific uremic arteriolopathy treated with bisphosphonates. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:1021-1025.

- Janigan DT, Hirsch DJ, Klassen GA, et al. Calcified subcutaneous arterioles with infarcts of the subcutis and skin (“calciphylaxis”) in chronic renal failure. Am J Kidney Dis. 2000;35:588-597.

- Robinson MR, Augustine JJ, Korman NJ. Cinacalcet for the treatment of calciphylaxis. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:152-154.

- Sharma A, Burkitt-Wright E, Rustom R. Cinacalcet as an adjunct in successful treatment of calciphylaxis. Br J Dermatol. 2006;155:1295-1297.

- Cicone JS, Petronis JB, Embert CD, et al. Successful treatment of calciphylaxis with intravenous sodium thiosulfate. Am J Kidney Dis. 2004;43:1104-1108.

- Guerra G, Shah RC, Ross EA. Rapid resolution of calciphylaxis with intravenous sodium thiosulfate and continuous venovenous haemofiltration using low calcium replacement fluid: case report [published online ahead of print May 3, 2005]. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2005;20:1260-1262.

- Podymow T, Wherrett C, Burns KD. Hyperbaricoxygen in the treatment of calciphylaxis: a case series. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2001;16:2176-2180.

- Basile C, Montanaro A, Masi M, et al. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy for calcific uremic arteriolopathy: a case series. J Nephrol. 2002;15:676-680.

- Fine A, Zacharias J. Calciphylaxis is usually non-ulcerating: risk factors, outcome and therapy. Kidney Int. 2002;61:2210-2217.