User login

Make the Diagnosis - March 2021

Because of the lack of improvement with topical corticosteroids, a skin biopsy was performed from a lesion on the lower back which showed an epidermis with compact hyperkeratosis and a thickened granular layer. Within the dermis, there was a lichenoid infiltrate of lymphocytes with a prominent interface change and rare dyskeratotic keratinocytes consistent with lichen planus.

Lichen planus is an inflammatory condition of the skin seen mainly in the adult population and is rare in children. This condition affects 0.5%-1% of the population, with maybe a higher prevalence in woman with no racial predilection in the adult or pediatric population. Most patients diagnosed are described to be over 40 years of age, but in children, the mean age for presentation is reported between the ages of 7 and 11.8 years.1 Interestingly, most of the published larger studies of lichen planus in children originate from India. In a U.K. study, about 80% of the cases reported were from children of Indian descent, as is our patient; so it is possible that lichen planus may be more prevalent in India.1 In a study based in the United States, cases were more prevalent in African American children.2

The exact cause of this condition is not known but studies have suggested that activated T cells, particularly CD8+, attack and cause apoptosis of the basal keratinocytes.3 There appears to be an up-regulation of Th1 cytokines such as interferon‐gamma, tumor necrosis factor–alpha, interleukin‐1 alpha, IL‐6, and IL‐8, as well as other apoptosis-related molecules.3

Lichen planus has been associated with other systemic conditions especially liver disease (chronic active hepatitis C and primary biliary cirrhosis). Children and adults may also have coexistence of other autoimmune diseases such as autoimmune polyendocrinopathy, myasthenia gravis, autoimmune thyroid disease, vitiligo, and thymoma. Some reports have also found a higher prevalence of atopic dermatitis in children with lichen planus.4

The lesions are typically described as the four “Ps” for pruritic, polygonal, purpuric flat-topped papules, and plaques. The papules of lichen planus have characteristically dry fine white streaks known as Wickham’s striae. The lesions can occur anywhere on the body, but they tend to occur more commonly on the flexures of the forearms, the wrists, ankles, shins, knees, and the torso. The face is rarely affected. In some patients oral, scalp (lichen planopilaris), nails, and rarely conjunctival, genital, and esophageal involvement can occur.2

In histopathology, the lesions are characterized by a wedge-shaped hypergranulosis, marked hyperkeratosis, and irregular sawtooth-like acanthosis of rete ridges on the epidermis. The dermal-epidermal junction typically shows an interstitial dermatitis. Civatte bodies may also be seen. On direct immunofluorescence, IgM-staining of the cytoid bodies in the dermal papilla or peribasilar areas are suggestive of lichen planus.1

The differential diagnosis of lichen planus includes severe lichenified atopic dermatitis, drug-induced lichen planus, graft-versus-host disease, psoriasis, pityriasis rosea, subacute cutaneous lupus, discoid lupus, secondary syphilis, and lichen simplex chronicus. Interestingly, our patient presented with lesions that were not pruritic and more generalized. Compared with eczema, were flexures are commonly affected, our patient’s lesions were localized to the ankles, wrists, extensor knees, and elbows, and no pruritus was reported. Lichenification of skin lesions occurs as a response to chronic scratching as it occurs in atopic dermatitis and lichen simplex chronicus, was considered in our patient, but the lack of pruritus and the more acute presentation made it unlikely.

Lichen planus is considered a self-limiting disease, so treatment is focused on the control of pruritus and to accelerate resolution. The first-line therapy for classic cutaneous lichen planus is the use of potent or superpotent topical corticosteroids for localized disease on the body and extremities and mild to mid-potency for intertriginous areas and the face. Clinical response should be assessed after 2-3 weeks of treatment. For patients with more generalized or recalcitrant disease like our patient, other treatment modalities like phototherapy (narrow-band UVB), a 4- to 6-week course of oral glucocorticoids, or acitretin may be considered. Our patient recently started narrow-band UVB. Other medications that have been reported beneficial for more severe cases include methotrexate, cyclosporine, griseofulvin, hydroxychloroquine, metronidazole, dapsone, and mycophenolate. Recent studies in the adult population have shown apremilast, a phosphodiesterase inhibitor, to be a promising medication for patients with cutaneous lichen planus, though this medication has not been approved yet for use in the pediatric population.5

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego.

References

1. Payette MJ et al. Clin Dermatol. 2015 Nov-Dec;33(6):631-43.

2. Walton KE et al. Pediatr Dermatol. 2010;27:34-8.

3. Lehman JS et al. Int J Dermatol. 2009 Jul;48(7):682-94.

4. Laughter D et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:649-55.

5. Paul J et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013 Feb;68(2):255-61.

Because of the lack of improvement with topical corticosteroids, a skin biopsy was performed from a lesion on the lower back which showed an epidermis with compact hyperkeratosis and a thickened granular layer. Within the dermis, there was a lichenoid infiltrate of lymphocytes with a prominent interface change and rare dyskeratotic keratinocytes consistent with lichen planus.

Lichen planus is an inflammatory condition of the skin seen mainly in the adult population and is rare in children. This condition affects 0.5%-1% of the population, with maybe a higher prevalence in woman with no racial predilection in the adult or pediatric population. Most patients diagnosed are described to be over 40 years of age, but in children, the mean age for presentation is reported between the ages of 7 and 11.8 years.1 Interestingly, most of the published larger studies of lichen planus in children originate from India. In a U.K. study, about 80% of the cases reported were from children of Indian descent, as is our patient; so it is possible that lichen planus may be more prevalent in India.1 In a study based in the United States, cases were more prevalent in African American children.2

The exact cause of this condition is not known but studies have suggested that activated T cells, particularly CD8+, attack and cause apoptosis of the basal keratinocytes.3 There appears to be an up-regulation of Th1 cytokines such as interferon‐gamma, tumor necrosis factor–alpha, interleukin‐1 alpha, IL‐6, and IL‐8, as well as other apoptosis-related molecules.3

Lichen planus has been associated with other systemic conditions especially liver disease (chronic active hepatitis C and primary biliary cirrhosis). Children and adults may also have coexistence of other autoimmune diseases such as autoimmune polyendocrinopathy, myasthenia gravis, autoimmune thyroid disease, vitiligo, and thymoma. Some reports have also found a higher prevalence of atopic dermatitis in children with lichen planus.4

The lesions are typically described as the four “Ps” for pruritic, polygonal, purpuric flat-topped papules, and plaques. The papules of lichen planus have characteristically dry fine white streaks known as Wickham’s striae. The lesions can occur anywhere on the body, but they tend to occur more commonly on the flexures of the forearms, the wrists, ankles, shins, knees, and the torso. The face is rarely affected. In some patients oral, scalp (lichen planopilaris), nails, and rarely conjunctival, genital, and esophageal involvement can occur.2

In histopathology, the lesions are characterized by a wedge-shaped hypergranulosis, marked hyperkeratosis, and irregular sawtooth-like acanthosis of rete ridges on the epidermis. The dermal-epidermal junction typically shows an interstitial dermatitis. Civatte bodies may also be seen. On direct immunofluorescence, IgM-staining of the cytoid bodies in the dermal papilla or peribasilar areas are suggestive of lichen planus.1

The differential diagnosis of lichen planus includes severe lichenified atopic dermatitis, drug-induced lichen planus, graft-versus-host disease, psoriasis, pityriasis rosea, subacute cutaneous lupus, discoid lupus, secondary syphilis, and lichen simplex chronicus. Interestingly, our patient presented with lesions that were not pruritic and more generalized. Compared with eczema, were flexures are commonly affected, our patient’s lesions were localized to the ankles, wrists, extensor knees, and elbows, and no pruritus was reported. Lichenification of skin lesions occurs as a response to chronic scratching as it occurs in atopic dermatitis and lichen simplex chronicus, was considered in our patient, but the lack of pruritus and the more acute presentation made it unlikely.

Lichen planus is considered a self-limiting disease, so treatment is focused on the control of pruritus and to accelerate resolution. The first-line therapy for classic cutaneous lichen planus is the use of potent or superpotent topical corticosteroids for localized disease on the body and extremities and mild to mid-potency for intertriginous areas and the face. Clinical response should be assessed after 2-3 weeks of treatment. For patients with more generalized or recalcitrant disease like our patient, other treatment modalities like phototherapy (narrow-band UVB), a 4- to 6-week course of oral glucocorticoids, or acitretin may be considered. Our patient recently started narrow-band UVB. Other medications that have been reported beneficial for more severe cases include methotrexate, cyclosporine, griseofulvin, hydroxychloroquine, metronidazole, dapsone, and mycophenolate. Recent studies in the adult population have shown apremilast, a phosphodiesterase inhibitor, to be a promising medication for patients with cutaneous lichen planus, though this medication has not been approved yet for use in the pediatric population.5

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego.

References

1. Payette MJ et al. Clin Dermatol. 2015 Nov-Dec;33(6):631-43.

2. Walton KE et al. Pediatr Dermatol. 2010;27:34-8.

3. Lehman JS et al. Int J Dermatol. 2009 Jul;48(7):682-94.

4. Laughter D et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:649-55.

5. Paul J et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013 Feb;68(2):255-61.

Because of the lack of improvement with topical corticosteroids, a skin biopsy was performed from a lesion on the lower back which showed an epidermis with compact hyperkeratosis and a thickened granular layer. Within the dermis, there was a lichenoid infiltrate of lymphocytes with a prominent interface change and rare dyskeratotic keratinocytes consistent with lichen planus.

Lichen planus is an inflammatory condition of the skin seen mainly in the adult population and is rare in children. This condition affects 0.5%-1% of the population, with maybe a higher prevalence in woman with no racial predilection in the adult or pediatric population. Most patients diagnosed are described to be over 40 years of age, but in children, the mean age for presentation is reported between the ages of 7 and 11.8 years.1 Interestingly, most of the published larger studies of lichen planus in children originate from India. In a U.K. study, about 80% of the cases reported were from children of Indian descent, as is our patient; so it is possible that lichen planus may be more prevalent in India.1 In a study based in the United States, cases were more prevalent in African American children.2

The exact cause of this condition is not known but studies have suggested that activated T cells, particularly CD8+, attack and cause apoptosis of the basal keratinocytes.3 There appears to be an up-regulation of Th1 cytokines such as interferon‐gamma, tumor necrosis factor–alpha, interleukin‐1 alpha, IL‐6, and IL‐8, as well as other apoptosis-related molecules.3

Lichen planus has been associated with other systemic conditions especially liver disease (chronic active hepatitis C and primary biliary cirrhosis). Children and adults may also have coexistence of other autoimmune diseases such as autoimmune polyendocrinopathy, myasthenia gravis, autoimmune thyroid disease, vitiligo, and thymoma. Some reports have also found a higher prevalence of atopic dermatitis in children with lichen planus.4

The lesions are typically described as the four “Ps” for pruritic, polygonal, purpuric flat-topped papules, and plaques. The papules of lichen planus have characteristically dry fine white streaks known as Wickham’s striae. The lesions can occur anywhere on the body, but they tend to occur more commonly on the flexures of the forearms, the wrists, ankles, shins, knees, and the torso. The face is rarely affected. In some patients oral, scalp (lichen planopilaris), nails, and rarely conjunctival, genital, and esophageal involvement can occur.2

In histopathology, the lesions are characterized by a wedge-shaped hypergranulosis, marked hyperkeratosis, and irregular sawtooth-like acanthosis of rete ridges on the epidermis. The dermal-epidermal junction typically shows an interstitial dermatitis. Civatte bodies may also be seen. On direct immunofluorescence, IgM-staining of the cytoid bodies in the dermal papilla or peribasilar areas are suggestive of lichen planus.1

The differential diagnosis of lichen planus includes severe lichenified atopic dermatitis, drug-induced lichen planus, graft-versus-host disease, psoriasis, pityriasis rosea, subacute cutaneous lupus, discoid lupus, secondary syphilis, and lichen simplex chronicus. Interestingly, our patient presented with lesions that were not pruritic and more generalized. Compared with eczema, were flexures are commonly affected, our patient’s lesions were localized to the ankles, wrists, extensor knees, and elbows, and no pruritus was reported. Lichenification of skin lesions occurs as a response to chronic scratching as it occurs in atopic dermatitis and lichen simplex chronicus, was considered in our patient, but the lack of pruritus and the more acute presentation made it unlikely.

Lichen planus is considered a self-limiting disease, so treatment is focused on the control of pruritus and to accelerate resolution. The first-line therapy for classic cutaneous lichen planus is the use of potent or superpotent topical corticosteroids for localized disease on the body and extremities and mild to mid-potency for intertriginous areas and the face. Clinical response should be assessed after 2-3 weeks of treatment. For patients with more generalized or recalcitrant disease like our patient, other treatment modalities like phototherapy (narrow-band UVB), a 4- to 6-week course of oral glucocorticoids, or acitretin may be considered. Our patient recently started narrow-band UVB. Other medications that have been reported beneficial for more severe cases include methotrexate, cyclosporine, griseofulvin, hydroxychloroquine, metronidazole, dapsone, and mycophenolate. Recent studies in the adult population have shown apremilast, a phosphodiesterase inhibitor, to be a promising medication for patients with cutaneous lichen planus, though this medication has not been approved yet for use in the pediatric population.5

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego.

References

1. Payette MJ et al. Clin Dermatol. 2015 Nov-Dec;33(6):631-43.

2. Walton KE et al. Pediatr Dermatol. 2010;27:34-8.

3. Lehman JS et al. Int J Dermatol. 2009 Jul;48(7):682-94.

4. Laughter D et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:649-55.

5. Paul J et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013 Feb;68(2):255-61.

There was no prior personal or family history of atopic dermatitis or psoriasis. He has no other medical conditions and is not taking any medications.

He denied any joint pain, sun sensitivity, mouth sores, or other symptoms. After the initial consultation he was treated with fluocinonide 0.05% ointment for 2 weeks with slight improvement on the lesions.

On physical exam he presented with hyperpigmented and violaceous lichenified papules and plaques on the extremities and the torso. (photos 1 and 2). He also had hyperpigmented violaceous macules on the eyelids and around the mouth (photos 1 and 2).

A girl presents with blotchy, slightly itchy spots on her chest, back

On close evaluation of the picture on her chest, she has pale macules and patches surrounded by erythematous ill-defined patches consistent with nevus anemicus. The findings of the picture raise the suspicion for neurofibromatosis, and it was recommended for her to be evaluated in person.

She comes several days later to the clinic. The caretaker, who is her aunt, reports she does not know much of the girl’s medical history as she recently moved from South America to live with her. The girl is a very nice and pleasant 8-year-old. She reports noticing the spots on her chest for about a year and that they seem to get a little itchier and more noticeable when she is hot or when she is running. She also reports increasing headaches for several months. She is being home schooled, and according to her aunt she is at par with her cousins who are about the same age. There is no history of seizures. She has had back surgery in the past. There is no history of hypertension. There is no family history of any genetic disorder or similar lesions.

On physical exam, her vital signs are normal, but her head circumference is over the 90th percentile. She is pleasant and interactive. On skin examination, she has slightly noticeable pale macules and patches on the chest and back that become more apparent after rubbing her skin. She has multiple light brown macules and oval patches on the chest, back, and neck. She has no axillary or inguinal freckling. She has scars on the back from her prior surgery.

As she was having worsening headaches, an MRI of the brain was ordered, which showed a left optic glioma. She was then referred to ophthalmology, neurology, and genetics.

Neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) is a common genetic autosomal dominant disorder cause by mutations on the NF1 gene on chromosome 17, which encodes for the protein neurofibromin. This protein works in the Ras-mitogen–activated protein kinase pathway as a negative regulator. Based on the National Institute of Health criteria, children need two or more of the following to be diagnosed with NF1: more than six café au lait macules larger than 5 mm in prepubescent children and 2.5 cm after puberty; axillary or inguinal freckling; two or more Lisch nodules; optic gliomas; two or more neurofibromas or one plexiform neurofibroma; or a first degree relative with a diagnosis of NF1. With these criteria, about 70% of the children can be diagnosed before the age of 1 year.1

Nevus anemicus is an uncommon birthmark, sometimes overlooked, that is characterized by pale, hypopigmented, well-defined macules and patches that do not turn red after trauma or changes in temperature. Nevus anemicus is usually localized on the torso but can be seen on the face, neck, and extremities. These lesions are present in 1%-2% of the general population. They are thought to occur because of increased sensitivity of the affected blood vessels to catecholamines, which causes permanent vasoconstriction, which leads to hypopigmentation on the area.2 These lesions are usually present at birth and have been described in patients with tuberous sclerosis, neurofibromatosis, and phakomatosis pigmentovascularis.

Recent studies of patients with neurofibromatosis and other RASopathies have noticed that nevus anemicus is present in about 8.8%-51% of the patients studied with a diagnosis NF1, compared with only 2% of the controls.3,4 The studies failed to report any cases of nevus anemicus in patients with other RASopathies associated with café au lait macules. Bulteel and colleagues recently reported two cases of non-NF1 RASopathies also associated with nevus anemicus in a patient with Legius syndrome and a patient with Noonan syndrome with multiple lentigines.5 The nevus anemicus was reported to occur most commonly on the anterior chest and be multiple, as seen in our patient.

The authors of the published studies advocate for the introduction of nevus anemicus as part of the diagnostic criteria for NF1, especially because it can be an early finding seen in babies, which can aid in early diagnosis of NF1.

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego. She has no relevant financial disclosures. Email Dr. Matiz at pdnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Pediatrics. 2000 Mar. doi: 10.1542/peds.105.3.608.

2. Nevus Anemicus. StatPearls [Internet] (Treasure Island, Fla.: StatPearls Publishing; 2020 Jan).

3. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013 Nov. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2013.06.039.

4. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015 May-Jun. doi: 10.1111/pde.12525.

5. JAAD Case Rep. 2018 Apr 5. doi: 10.1016/j.jdcr.2017.09.037.

On close evaluation of the picture on her chest, she has pale macules and patches surrounded by erythematous ill-defined patches consistent with nevus anemicus. The findings of the picture raise the suspicion for neurofibromatosis, and it was recommended for her to be evaluated in person.

She comes several days later to the clinic. The caretaker, who is her aunt, reports she does not know much of the girl’s medical history as she recently moved from South America to live with her. The girl is a very nice and pleasant 8-year-old. She reports noticing the spots on her chest for about a year and that they seem to get a little itchier and more noticeable when she is hot or when she is running. She also reports increasing headaches for several months. She is being home schooled, and according to her aunt she is at par with her cousins who are about the same age. There is no history of seizures. She has had back surgery in the past. There is no history of hypertension. There is no family history of any genetic disorder or similar lesions.

On physical exam, her vital signs are normal, but her head circumference is over the 90th percentile. She is pleasant and interactive. On skin examination, she has slightly noticeable pale macules and patches on the chest and back that become more apparent after rubbing her skin. She has multiple light brown macules and oval patches on the chest, back, and neck. She has no axillary or inguinal freckling. She has scars on the back from her prior surgery.

As she was having worsening headaches, an MRI of the brain was ordered, which showed a left optic glioma. She was then referred to ophthalmology, neurology, and genetics.

Neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) is a common genetic autosomal dominant disorder cause by mutations on the NF1 gene on chromosome 17, which encodes for the protein neurofibromin. This protein works in the Ras-mitogen–activated protein kinase pathway as a negative regulator. Based on the National Institute of Health criteria, children need two or more of the following to be diagnosed with NF1: more than six café au lait macules larger than 5 mm in prepubescent children and 2.5 cm after puberty; axillary or inguinal freckling; two or more Lisch nodules; optic gliomas; two or more neurofibromas or one plexiform neurofibroma; or a first degree relative with a diagnosis of NF1. With these criteria, about 70% of the children can be diagnosed before the age of 1 year.1

Nevus anemicus is an uncommon birthmark, sometimes overlooked, that is characterized by pale, hypopigmented, well-defined macules and patches that do not turn red after trauma or changes in temperature. Nevus anemicus is usually localized on the torso but can be seen on the face, neck, and extremities. These lesions are present in 1%-2% of the general population. They are thought to occur because of increased sensitivity of the affected blood vessels to catecholamines, which causes permanent vasoconstriction, which leads to hypopigmentation on the area.2 These lesions are usually present at birth and have been described in patients with tuberous sclerosis, neurofibromatosis, and phakomatosis pigmentovascularis.

Recent studies of patients with neurofibromatosis and other RASopathies have noticed that nevus anemicus is present in about 8.8%-51% of the patients studied with a diagnosis NF1, compared with only 2% of the controls.3,4 The studies failed to report any cases of nevus anemicus in patients with other RASopathies associated with café au lait macules. Bulteel and colleagues recently reported two cases of non-NF1 RASopathies also associated with nevus anemicus in a patient with Legius syndrome and a patient with Noonan syndrome with multiple lentigines.5 The nevus anemicus was reported to occur most commonly on the anterior chest and be multiple, as seen in our patient.

The authors of the published studies advocate for the introduction of nevus anemicus as part of the diagnostic criteria for NF1, especially because it can be an early finding seen in babies, which can aid in early diagnosis of NF1.

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego. She has no relevant financial disclosures. Email Dr. Matiz at pdnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Pediatrics. 2000 Mar. doi: 10.1542/peds.105.3.608.

2. Nevus Anemicus. StatPearls [Internet] (Treasure Island, Fla.: StatPearls Publishing; 2020 Jan).

3. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013 Nov. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2013.06.039.

4. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015 May-Jun. doi: 10.1111/pde.12525.

5. JAAD Case Rep. 2018 Apr 5. doi: 10.1016/j.jdcr.2017.09.037.

On close evaluation of the picture on her chest, she has pale macules and patches surrounded by erythematous ill-defined patches consistent with nevus anemicus. The findings of the picture raise the suspicion for neurofibromatosis, and it was recommended for her to be evaluated in person.

She comes several days later to the clinic. The caretaker, who is her aunt, reports she does not know much of the girl’s medical history as she recently moved from South America to live with her. The girl is a very nice and pleasant 8-year-old. She reports noticing the spots on her chest for about a year and that they seem to get a little itchier and more noticeable when she is hot or when she is running. She also reports increasing headaches for several months. She is being home schooled, and according to her aunt she is at par with her cousins who are about the same age. There is no history of seizures. She has had back surgery in the past. There is no history of hypertension. There is no family history of any genetic disorder or similar lesions.

On physical exam, her vital signs are normal, but her head circumference is over the 90th percentile. She is pleasant and interactive. On skin examination, she has slightly noticeable pale macules and patches on the chest and back that become more apparent after rubbing her skin. She has multiple light brown macules and oval patches on the chest, back, and neck. She has no axillary or inguinal freckling. She has scars on the back from her prior surgery.

As she was having worsening headaches, an MRI of the brain was ordered, which showed a left optic glioma. She was then referred to ophthalmology, neurology, and genetics.

Neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) is a common genetic autosomal dominant disorder cause by mutations on the NF1 gene on chromosome 17, which encodes for the protein neurofibromin. This protein works in the Ras-mitogen–activated protein kinase pathway as a negative regulator. Based on the National Institute of Health criteria, children need two or more of the following to be diagnosed with NF1: more than six café au lait macules larger than 5 mm in prepubescent children and 2.5 cm after puberty; axillary or inguinal freckling; two or more Lisch nodules; optic gliomas; two or more neurofibromas or one plexiform neurofibroma; or a first degree relative with a diagnosis of NF1. With these criteria, about 70% of the children can be diagnosed before the age of 1 year.1

Nevus anemicus is an uncommon birthmark, sometimes overlooked, that is characterized by pale, hypopigmented, well-defined macules and patches that do not turn red after trauma or changes in temperature. Nevus anemicus is usually localized on the torso but can be seen on the face, neck, and extremities. These lesions are present in 1%-2% of the general population. They are thought to occur because of increased sensitivity of the affected blood vessels to catecholamines, which causes permanent vasoconstriction, which leads to hypopigmentation on the area.2 These lesions are usually present at birth and have been described in patients with tuberous sclerosis, neurofibromatosis, and phakomatosis pigmentovascularis.

Recent studies of patients with neurofibromatosis and other RASopathies have noticed that nevus anemicus is present in about 8.8%-51% of the patients studied with a diagnosis NF1, compared with only 2% of the controls.3,4 The studies failed to report any cases of nevus anemicus in patients with other RASopathies associated with café au lait macules. Bulteel and colleagues recently reported two cases of non-NF1 RASopathies also associated with nevus anemicus in a patient with Legius syndrome and a patient with Noonan syndrome with multiple lentigines.5 The nevus anemicus was reported to occur most commonly on the anterior chest and be multiple, as seen in our patient.

The authors of the published studies advocate for the introduction of nevus anemicus as part of the diagnostic criteria for NF1, especially because it can be an early finding seen in babies, which can aid in early diagnosis of NF1.

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego. She has no relevant financial disclosures. Email Dr. Matiz at pdnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Pediatrics. 2000 Mar. doi: 10.1542/peds.105.3.608.

2. Nevus Anemicus. StatPearls [Internet] (Treasure Island, Fla.: StatPearls Publishing; 2020 Jan).

3. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013 Nov. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2013.06.039.

4. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015 May-Jun. doi: 10.1111/pde.12525.

5. JAAD Case Rep. 2018 Apr 5. doi: 10.1016/j.jdcr.2017.09.037.

A teen presents with a severe, tender rash on the extremities

“There’s rue for you, and here’s some for me; we may call it herb of grace o’ Sundays. O, you must wear your rue with a difference.”

— Ophelia in Hamlet by William Shakespeare

The patient was admitted to the hospital for IV fluids, pain control, and observation. The following day she admitted using the leaves of a plant on the trail as a bug repellent, as one time was taught by her grandfather. She rubbed some of the leaves on the brother as well. The grandfather shared some pictures of the bushes, and the plant was identified as Ruta graveolens.

The blisters were deroofed, cleaned with saline, and wrapped with triamcinolone ointment and petrolatum. The patient was also started on a prednisone taper and received analgesics for the severe pain.

Ruta graveolens also known as common rue or herb of grace, is an ornamental plant from the Rutaceae family. This plant is also used as a medicinal herb, condiment, and as an insect repellent. If ingested in large doses, it can cause severe abdominal pain and vomiting. It also can be hepatotoxic.

The herb contains furocumarines, such as 8-methoxypsoralen and 5-methoxypsoralen and furoquinoline alkaloids. These chemicals when exposed to UVA radiation cause cell injury and inflammation of the skin. This is considered a phototoxic reaction of the skin, compared with allergic reactions, such as poison ivy dermatitis, which need a prior sensitization to the allergen for the T cells to be activated and cause injury in the skin. Other common plants and fruits that can cause phytophotodermatitis include citrus fruits, figs, carrots, celery, parsnips, parsley, and other wildflowers like hogweed.

Depending on the degree of injury, the patients can be treated with topical corticosteroids, petrolatum wraps, and pain control. In severe cases like our patient, systemic prednisone may help stop the progression of the lesions and help with the inflammation. Skin hyperpigmentation after the initial injury may take months to clear, and some patient can develop scars.

The differential diagnosis should include severe bullous contact dermatitis like exposure to urushiol in poison ivy; second- and third-degree burns; severe medications reactions such Stevens-Johnson syndrome or toxic epidermal necrolysis, and inmunobullous diseases such as bullous lupus erythematosus, pemphigus vulgaris, or bullous pemphigoid. If there is no history of exposure or there are any other systemic symptoms, consider performing a skin biopsy of one of the lesions.

In this patient’s case, the history of exposure and skin findings helped the dermatologist on call make the right diagnosis.

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego. Email her at pdnews@mdedge.com.

References

J Burn Care Res. 2018 Oct 23;39(6):1064-6.

Dermatitis. 2007 Mar;18(1):52-5.

BMJ Case Rep. 2015 Dec 23;2015:bcr2015213388.

“There’s rue for you, and here’s some for me; we may call it herb of grace o’ Sundays. O, you must wear your rue with a difference.”

— Ophelia in Hamlet by William Shakespeare

The patient was admitted to the hospital for IV fluids, pain control, and observation. The following day she admitted using the leaves of a plant on the trail as a bug repellent, as one time was taught by her grandfather. She rubbed some of the leaves on the brother as well. The grandfather shared some pictures of the bushes, and the plant was identified as Ruta graveolens.

The blisters were deroofed, cleaned with saline, and wrapped with triamcinolone ointment and petrolatum. The patient was also started on a prednisone taper and received analgesics for the severe pain.

Ruta graveolens also known as common rue or herb of grace, is an ornamental plant from the Rutaceae family. This plant is also used as a medicinal herb, condiment, and as an insect repellent. If ingested in large doses, it can cause severe abdominal pain and vomiting. It also can be hepatotoxic.

The herb contains furocumarines, such as 8-methoxypsoralen and 5-methoxypsoralen and furoquinoline alkaloids. These chemicals when exposed to UVA radiation cause cell injury and inflammation of the skin. This is considered a phototoxic reaction of the skin, compared with allergic reactions, such as poison ivy dermatitis, which need a prior sensitization to the allergen for the T cells to be activated and cause injury in the skin. Other common plants and fruits that can cause phytophotodermatitis include citrus fruits, figs, carrots, celery, parsnips, parsley, and other wildflowers like hogweed.

Depending on the degree of injury, the patients can be treated with topical corticosteroids, petrolatum wraps, and pain control. In severe cases like our patient, systemic prednisone may help stop the progression of the lesions and help with the inflammation. Skin hyperpigmentation after the initial injury may take months to clear, and some patient can develop scars.

The differential diagnosis should include severe bullous contact dermatitis like exposure to urushiol in poison ivy; second- and third-degree burns; severe medications reactions such Stevens-Johnson syndrome or toxic epidermal necrolysis, and inmunobullous diseases such as bullous lupus erythematosus, pemphigus vulgaris, or bullous pemphigoid. If there is no history of exposure or there are any other systemic symptoms, consider performing a skin biopsy of one of the lesions.

In this patient’s case, the history of exposure and skin findings helped the dermatologist on call make the right diagnosis.

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego. Email her at pdnews@mdedge.com.

References

J Burn Care Res. 2018 Oct 23;39(6):1064-6.

Dermatitis. 2007 Mar;18(1):52-5.

BMJ Case Rep. 2015 Dec 23;2015:bcr2015213388.

“There’s rue for you, and here’s some for me; we may call it herb of grace o’ Sundays. O, you must wear your rue with a difference.”

— Ophelia in Hamlet by William Shakespeare

The patient was admitted to the hospital for IV fluids, pain control, and observation. The following day she admitted using the leaves of a plant on the trail as a bug repellent, as one time was taught by her grandfather. She rubbed some of the leaves on the brother as well. The grandfather shared some pictures of the bushes, and the plant was identified as Ruta graveolens.

The blisters were deroofed, cleaned with saline, and wrapped with triamcinolone ointment and petrolatum. The patient was also started on a prednisone taper and received analgesics for the severe pain.

Ruta graveolens also known as common rue or herb of grace, is an ornamental plant from the Rutaceae family. This plant is also used as a medicinal herb, condiment, and as an insect repellent. If ingested in large doses, it can cause severe abdominal pain and vomiting. It also can be hepatotoxic.

The herb contains furocumarines, such as 8-methoxypsoralen and 5-methoxypsoralen and furoquinoline alkaloids. These chemicals when exposed to UVA radiation cause cell injury and inflammation of the skin. This is considered a phototoxic reaction of the skin, compared with allergic reactions, such as poison ivy dermatitis, which need a prior sensitization to the allergen for the T cells to be activated and cause injury in the skin. Other common plants and fruits that can cause phytophotodermatitis include citrus fruits, figs, carrots, celery, parsnips, parsley, and other wildflowers like hogweed.

Depending on the degree of injury, the patients can be treated with topical corticosteroids, petrolatum wraps, and pain control. In severe cases like our patient, systemic prednisone may help stop the progression of the lesions and help with the inflammation. Skin hyperpigmentation after the initial injury may take months to clear, and some patient can develop scars.

The differential diagnosis should include severe bullous contact dermatitis like exposure to urushiol in poison ivy; second- and third-degree burns; severe medications reactions such Stevens-Johnson syndrome or toxic epidermal necrolysis, and inmunobullous diseases such as bullous lupus erythematosus, pemphigus vulgaris, or bullous pemphigoid. If there is no history of exposure or there are any other systemic symptoms, consider performing a skin biopsy of one of the lesions.

In this patient’s case, the history of exposure and skin findings helped the dermatologist on call make the right diagnosis.

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego. Email her at pdnews@mdedge.com.

References

J Burn Care Res. 2018 Oct 23;39(6):1064-6.

Dermatitis. 2007 Mar;18(1):52-5.

BMJ Case Rep. 2015 Dec 23;2015:bcr2015213388.

She started taking lithium for depression and anxiety 3 weeks prior to her developing the rash. She denies taking any other medications, supplements, or recreational drugs.

She denied any prior history of photosensitivity, no history of mouth ulcers, joint pain, muscle weakness, hair loss, or any other symptoms.

Besides her brother, there are no other affected family members, and no history of immune bullous disorders or other skin conditions.

On physical exam, the girl appears in a lot of pain and is uncomfortable. The skin is red and hot, and there are tense bullae on the neck, arms, and legs. There are no ocular or mucosal lesions.

A 4-year-old with a lesion on her cheek, which grew and became firmer over two months

The patient was diagnosed with idiopathic facial aseptic granuloma (IFAG) based on the clinical findings, as well as the associated history of chalazia and erythematous papules seen in childhood rosacea.

She was treated with several months of azithromycin, sulfur wash, and metronidazole cream with improvement of some of the smaller lesions but no change on the larger nodules. Later she was treated with oral and topical ivermectin with no improvement. Some of the nodules slowly resolved except for the larger lesion on the right cheek. She was later treated with a 6-week course of clarithromycin with partial improvement of the nodule. The lesion resolved after 2 months of stopping clarithromycin.

IFAG is a rare condition seen in prepubescent children. The etiology of this condition is not well understood and is thought to be on the spectrum of childhood rosacea.1 From several recent reports, IFAG usually is seen in children with associated conditions including chalazia, conjunctivitis, blepharitis, and telangiectasias, which can be seen in patients with rosacea. These associated findings suggest the possibility of IFAG being a form of granulomatous rosacea in children.

This condition presents in childhood between the ages of 8 months and 13 years. Most of the cases occur in toddlers, and girls appear to be more affected than boys. The lesions appear as pink, rubbery, nontender, nonfluctuant nodules on the cheeks, which can be single or multiple. A large prospective study in 30 children demonstrated that more 70% of the lesions cultured were negative for bacteria. Histologic analysis of some of the lesions showed a chronic dermal lymphohistiocytic granulomatous perifollicular infiltrate with numerous foreign body–type giant cells.2

The differential diagnosis of these lesions should include infectious pyodermas such as mycobacterial infections, cutaneous leishmaniasis, and botryomycosis; deep fungal infections such as sporotrichosis, coccidioidomycosis, and cryptococcosis; childhood nodulocystic acne; pilomatrixoma; epidermoid cyst; vascular tumors or malformations; and leukemia cutis.3

The diagnosis is usually clinical but in atypical cases a skin biopsy with tissue cultures should be performed. The decision to biopsy these lesions will need to be done in a one by one basis, as a biopsy may leave scaring on the area affected.

It has been postulated that a color Doppler ultrasound of the lesion may be a helpful ancillary study. Echographic findings show a well demarcated solid-cystic, hypoechoic dermal lesion, the largest axis of which lies parallel to the skin surface. The lesion lacks calcium deposits. Other findings include increased echogenicity of the underlaying hypodermis. The findings may vary depending on the stage of the lesion.4

The course of the condition may last on average months to years. Some lesions resolve spontaneously and others may respond to courses of oral antibiotics such as clarithromycin, azithromycin, or ivermectin. In our patient, several lesions improved with oral antibiotics, but the larger lesions were more persistent and resolved after a year.

The lesions usually resolve without scarring. In those patients with associated rosacea, maintenance topical treatments may be warranted and also may need follow-up with ophthalmology because they tend to commonly have ocular rosacea as well.

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at pdnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013 Jan-Feb;30(1):109-11.

2. Br J Dermatol. 2007 Apr;156(4):705-8.

3. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018 Jul;35(4):490-3.

4. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2019 Oct;110(8):637-41.

The patient was diagnosed with idiopathic facial aseptic granuloma (IFAG) based on the clinical findings, as well as the associated history of chalazia and erythematous papules seen in childhood rosacea.

She was treated with several months of azithromycin, sulfur wash, and metronidazole cream with improvement of some of the smaller lesions but no change on the larger nodules. Later she was treated with oral and topical ivermectin with no improvement. Some of the nodules slowly resolved except for the larger lesion on the right cheek. She was later treated with a 6-week course of clarithromycin with partial improvement of the nodule. The lesion resolved after 2 months of stopping clarithromycin.

IFAG is a rare condition seen in prepubescent children. The etiology of this condition is not well understood and is thought to be on the spectrum of childhood rosacea.1 From several recent reports, IFAG usually is seen in children with associated conditions including chalazia, conjunctivitis, blepharitis, and telangiectasias, which can be seen in patients with rosacea. These associated findings suggest the possibility of IFAG being a form of granulomatous rosacea in children.

This condition presents in childhood between the ages of 8 months and 13 years. Most of the cases occur in toddlers, and girls appear to be more affected than boys. The lesions appear as pink, rubbery, nontender, nonfluctuant nodules on the cheeks, which can be single or multiple. A large prospective study in 30 children demonstrated that more 70% of the lesions cultured were negative for bacteria. Histologic analysis of some of the lesions showed a chronic dermal lymphohistiocytic granulomatous perifollicular infiltrate with numerous foreign body–type giant cells.2

The differential diagnosis of these lesions should include infectious pyodermas such as mycobacterial infections, cutaneous leishmaniasis, and botryomycosis; deep fungal infections such as sporotrichosis, coccidioidomycosis, and cryptococcosis; childhood nodulocystic acne; pilomatrixoma; epidermoid cyst; vascular tumors or malformations; and leukemia cutis.3

The diagnosis is usually clinical but in atypical cases a skin biopsy with tissue cultures should be performed. The decision to biopsy these lesions will need to be done in a one by one basis, as a biopsy may leave scaring on the area affected.

It has been postulated that a color Doppler ultrasound of the lesion may be a helpful ancillary study. Echographic findings show a well demarcated solid-cystic, hypoechoic dermal lesion, the largest axis of which lies parallel to the skin surface. The lesion lacks calcium deposits. Other findings include increased echogenicity of the underlaying hypodermis. The findings may vary depending on the stage of the lesion.4

The course of the condition may last on average months to years. Some lesions resolve spontaneously and others may respond to courses of oral antibiotics such as clarithromycin, azithromycin, or ivermectin. In our patient, several lesions improved with oral antibiotics, but the larger lesions were more persistent and resolved after a year.

The lesions usually resolve without scarring. In those patients with associated rosacea, maintenance topical treatments may be warranted and also may need follow-up with ophthalmology because they tend to commonly have ocular rosacea as well.

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at pdnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013 Jan-Feb;30(1):109-11.

2. Br J Dermatol. 2007 Apr;156(4):705-8.

3. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018 Jul;35(4):490-3.

4. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2019 Oct;110(8):637-41.

The patient was diagnosed with idiopathic facial aseptic granuloma (IFAG) based on the clinical findings, as well as the associated history of chalazia and erythematous papules seen in childhood rosacea.

She was treated with several months of azithromycin, sulfur wash, and metronidazole cream with improvement of some of the smaller lesions but no change on the larger nodules. Later she was treated with oral and topical ivermectin with no improvement. Some of the nodules slowly resolved except for the larger lesion on the right cheek. She was later treated with a 6-week course of clarithromycin with partial improvement of the nodule. The lesion resolved after 2 months of stopping clarithromycin.

IFAG is a rare condition seen in prepubescent children. The etiology of this condition is not well understood and is thought to be on the spectrum of childhood rosacea.1 From several recent reports, IFAG usually is seen in children with associated conditions including chalazia, conjunctivitis, blepharitis, and telangiectasias, which can be seen in patients with rosacea. These associated findings suggest the possibility of IFAG being a form of granulomatous rosacea in children.

This condition presents in childhood between the ages of 8 months and 13 years. Most of the cases occur in toddlers, and girls appear to be more affected than boys. The lesions appear as pink, rubbery, nontender, nonfluctuant nodules on the cheeks, which can be single or multiple. A large prospective study in 30 children demonstrated that more 70% of the lesions cultured were negative for bacteria. Histologic analysis of some of the lesions showed a chronic dermal lymphohistiocytic granulomatous perifollicular infiltrate with numerous foreign body–type giant cells.2

The differential diagnosis of these lesions should include infectious pyodermas such as mycobacterial infections, cutaneous leishmaniasis, and botryomycosis; deep fungal infections such as sporotrichosis, coccidioidomycosis, and cryptococcosis; childhood nodulocystic acne; pilomatrixoma; epidermoid cyst; vascular tumors or malformations; and leukemia cutis.3

The diagnosis is usually clinical but in atypical cases a skin biopsy with tissue cultures should be performed. The decision to biopsy these lesions will need to be done in a one by one basis, as a biopsy may leave scaring on the area affected.

It has been postulated that a color Doppler ultrasound of the lesion may be a helpful ancillary study. Echographic findings show a well demarcated solid-cystic, hypoechoic dermal lesion, the largest axis of which lies parallel to the skin surface. The lesion lacks calcium deposits. Other findings include increased echogenicity of the underlaying hypodermis. The findings may vary depending on the stage of the lesion.4

The course of the condition may last on average months to years. Some lesions resolve spontaneously and others may respond to courses of oral antibiotics such as clarithromycin, azithromycin, or ivermectin. In our patient, several lesions improved with oral antibiotics, but the larger lesions were more persistent and resolved after a year.

The lesions usually resolve without scarring. In those patients with associated rosacea, maintenance topical treatments may be warranted and also may need follow-up with ophthalmology because they tend to commonly have ocular rosacea as well.

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at pdnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013 Jan-Feb;30(1):109-11.

2. Br J Dermatol. 2007 Apr;156(4):705-8.

3. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018 Jul;35(4):490-3.

4. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2019 Oct;110(8):637-41.

A 4-year-old female is brought to our pediatric dermatology clinic for evaluation of a persistent lesion on the cheek.

The mother of the child reports that the lesion started as a small "bug bite" and then started growing and getting firmer for the past 2 months. The girl has developed other smaller red, pimple-like lesions on the cheeks and one of them is starting to increase in size.

She denies any tenderness on the area or any purulent discharge. She has had no fevers, chills, weight loss, nose bleeds, fatigue, or any other symptoms. The mother has not noted any changes on the child's body odor, any rapid growth, or hair on her axillary or pubic area. She was treated with three different courses of oral antibiotics including cephalexin, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, and clindamycin, as well as topical mupirocin, with no improvement.

Her past medical history is significant for several episodes of eyelid cysts that were treated with warm compresses and topical erythromycin ointment. The family history is significant for the father having severe acne as a teenager. She has two cats, she has not traveled, and she has an older sister who has no lesions.

On physical examination she is a lovely 4-year-old female in no acute distress. Her height is on the 70th percentile and weight on the 40th percentile for her age. Her blood pressure is 95/84 with a heart rate of 96. On skin examination she has several pink macules and papules on her bilateral cheeks. On the left cheek there are two pink nodules: One is 1 cm, and the other is 7 mm. The nodules are not tender. There is no warmth, fluctuance, or discharge from the lesions.

She has no cervical lymphadenopathy. She has no axillary or pubic hair. She is Tanner stage I.

What presents as deep erythematous papules, pustules, and may form an annular or circular plaque?

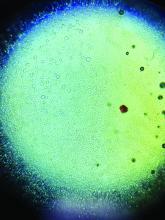

Scrapings of the child’s rash were analyzed with potassium hydroxide (KOH) under microscopy which revealed multiple septate hyphae.

She was diagnosed with Majocchi’s granuloma. The fungal culture was positive for Trichophyton rubrum.

Majocchi’s granuloma (MG) is cutaneous mycosis in which the fungal infection goes deeper into the hair follicle causing granulomatous folliculitis and perifolliculitis.1 It was first described by Domenico Majocchi in 1883, and he named the condition “granuloma tricofitico.”2

It is commonly caused by T. rubrum but also can be caused by T. mentagrophytes, T. tonsurans, T. verrucosum, Microsporum canis, and Epidermophyton floccosum.2,3 Patients at risk for developing this infection include those previously treated with topical corticosteroids, immunosuppressed patients, patients with areas under occlusion, and those with areas traumatized by shaving. This infection is most commonly seen in the lower extremities, but can happen anywhere in the body. The lesions present as deep erythematous papules, pustules, and may form an annular or circular plaque as seen on our patient.

A KOH test of skin scrapings and hair extractions often can reveal fungal hyphae. Identification of the pathogen can be performed with culture or polymerase chain reaction of skin samples. If the diagnosis is uncertain or the KOH is negative, a skin biopsy can be performed. Histopathologic examination reveals perifollicular granulomas with associated dermal abscesses. Giant cells may be observed. MG is associated with chronic inflammation with lymphocytes, macrophages, epithelioid cells, and scattered multinucleated giant cells.2,3

The differential diagnosis for these lesions in children includes other granulomatous conditions such as granulomatous rosacea, sarcoidosis, and granuloma faciale, as well as bacterial or atypical mycobacterial infections, cutaneous leishmaniasis, and eosinophilic pustular folliculitis.

Treatment of MG requires systemic treatment with griseofulvin, itraconazole, or terbinafine for at least 4-8 weeks or until all the lesions have resolved. Our patient was treated with 6 weeks of high-dose griseofulvin with resolution of her lesions.

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at pdnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Dermatol Online J. 2018 Dec 15;24(12):13030/qt89k4t6wj.

2. Med Mycol. 2012 Jul;50(5):449-57.

3. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2011 Apr;24(2):247-80.

Scrapings of the child’s rash were analyzed with potassium hydroxide (KOH) under microscopy which revealed multiple septate hyphae.

She was diagnosed with Majocchi’s granuloma. The fungal culture was positive for Trichophyton rubrum.

Majocchi’s granuloma (MG) is cutaneous mycosis in which the fungal infection goes deeper into the hair follicle causing granulomatous folliculitis and perifolliculitis.1 It was first described by Domenico Majocchi in 1883, and he named the condition “granuloma tricofitico.”2

It is commonly caused by T. rubrum but also can be caused by T. mentagrophytes, T. tonsurans, T. verrucosum, Microsporum canis, and Epidermophyton floccosum.2,3 Patients at risk for developing this infection include those previously treated with topical corticosteroids, immunosuppressed patients, patients with areas under occlusion, and those with areas traumatized by shaving. This infection is most commonly seen in the lower extremities, but can happen anywhere in the body. The lesions present as deep erythematous papules, pustules, and may form an annular or circular plaque as seen on our patient.

A KOH test of skin scrapings and hair extractions often can reveal fungal hyphae. Identification of the pathogen can be performed with culture or polymerase chain reaction of skin samples. If the diagnosis is uncertain or the KOH is negative, a skin biopsy can be performed. Histopathologic examination reveals perifollicular granulomas with associated dermal abscesses. Giant cells may be observed. MG is associated with chronic inflammation with lymphocytes, macrophages, epithelioid cells, and scattered multinucleated giant cells.2,3

The differential diagnosis for these lesions in children includes other granulomatous conditions such as granulomatous rosacea, sarcoidosis, and granuloma faciale, as well as bacterial or atypical mycobacterial infections, cutaneous leishmaniasis, and eosinophilic pustular folliculitis.

Treatment of MG requires systemic treatment with griseofulvin, itraconazole, or terbinafine for at least 4-8 weeks or until all the lesions have resolved. Our patient was treated with 6 weeks of high-dose griseofulvin with resolution of her lesions.

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at pdnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Dermatol Online J. 2018 Dec 15;24(12):13030/qt89k4t6wj.

2. Med Mycol. 2012 Jul;50(5):449-57.

3. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2011 Apr;24(2):247-80.

Scrapings of the child’s rash were analyzed with potassium hydroxide (KOH) under microscopy which revealed multiple septate hyphae.

She was diagnosed with Majocchi’s granuloma. The fungal culture was positive for Trichophyton rubrum.

Majocchi’s granuloma (MG) is cutaneous mycosis in which the fungal infection goes deeper into the hair follicle causing granulomatous folliculitis and perifolliculitis.1 It was first described by Domenico Majocchi in 1883, and he named the condition “granuloma tricofitico.”2

It is commonly caused by T. rubrum but also can be caused by T. mentagrophytes, T. tonsurans, T. verrucosum, Microsporum canis, and Epidermophyton floccosum.2,3 Patients at risk for developing this infection include those previously treated with topical corticosteroids, immunosuppressed patients, patients with areas under occlusion, and those with areas traumatized by shaving. This infection is most commonly seen in the lower extremities, but can happen anywhere in the body. The lesions present as deep erythematous papules, pustules, and may form an annular or circular plaque as seen on our patient.

A KOH test of skin scrapings and hair extractions often can reveal fungal hyphae. Identification of the pathogen can be performed with culture or polymerase chain reaction of skin samples. If the diagnosis is uncertain or the KOH is negative, a skin biopsy can be performed. Histopathologic examination reveals perifollicular granulomas with associated dermal abscesses. Giant cells may be observed. MG is associated with chronic inflammation with lymphocytes, macrophages, epithelioid cells, and scattered multinucleated giant cells.2,3

The differential diagnosis for these lesions in children includes other granulomatous conditions such as granulomatous rosacea, sarcoidosis, and granuloma faciale, as well as bacterial or atypical mycobacterial infections, cutaneous leishmaniasis, and eosinophilic pustular folliculitis.

Treatment of MG requires systemic treatment with griseofulvin, itraconazole, or terbinafine for at least 4-8 weeks or until all the lesions have resolved. Our patient was treated with 6 weeks of high-dose griseofulvin with resolution of her lesions.

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at pdnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Dermatol Online J. 2018 Dec 15;24(12):13030/qt89k4t6wj.

2. Med Mycol. 2012 Jul;50(5):449-57.

3. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2011 Apr;24(2):247-80.

A 3-year-old girl with a known history of eczema presented to our dermatology clinic for evaluation of a persistent rash for about a year on the right cheek.

The mother reported she was treating the lesions with hydrocortisone cream 2.5% as instructed previously for her eczema. Initially the rash got partially better but then started getting worse again. The area was itchy.

The child was later seen in the emergency department, where she was recommended to treat the area with a combination cream of terbinafine 1% and betamethasone dipropionate 0.05%. The mother applied this cream as instructed for 3 weeks with some improvement of the lesions on the cheek.

A few weeks later, pimples started coming back. The mother tried the medication again but this time it was not helpful and the rash continued to expand.

The mother reported having a rash on her hand months back, which she successfully treated with the combination cream provided at the emergency department. They have no pets at home.

The child has a little sister who also has mild eczema.

She goes to day care and dances ballet.

What's your diagnosis?

A punch biopsy of one of the lesions showed a superficial and deep mixed inflammatory cell infiltrate, including neutrophils and eosinophils. There was also vasculitis, karyorrhexis and extravasated red blood cells. The findings are those of leukocytoclastic vasculitis, suggestive of acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy. Direct immunofluorescence was positive for IgM, C3, and fibrinogen, but negative for IgA.

Acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy (AHEI), also known as Finkelstein disease, is form of leukocytoclastic vasculitis that occurs in infants and toddlers aged between4 months and 3 years.

The lesions start as petechiae or edematous, erythematous to violaceous nodules that later coalesce and form “cockade”-like plaques with a central clearing on the face and extremities. Gastrointestinal, renal, and joint involvement are rare.1 AHEI follows a benign course with resolution of the lesions and symptoms within days to weeks. The etiology of this condition is not known but infection triggers have been reported including coronavirus infections, coxsackie virus infections, Escherichia coli urinary tract infections, herpes simplex virus stomatitis, and pneumococcal bacteremia.2,3 Our patient had a prior history of pneumococcal pneumonia and metapneumovirus infection. MMR vaccine also has been reported as a possible trigger, as well as some medications.

Laboratory results are usually normal, but some patients may have elevated inflammatory markers (C-reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate), as noted in our patient, and leukocytosis, thrombocytosis, and eosinophilia. Microscopic analysis demonstrates leukocytoclastic vasculitis of small vessels with associated karyorrhexis and extravasated red blood cells.

The differential diagnosis includes other vasculitic conditions, primarily Henoch-Schönlein purpura (HSP). Patients with HSP tend to be older in age and the lesions described as palpable purpura commonly affect the lower extremities and buttocks. These patients can present with abdominal pain and arthritis; renal compromise also can occur. Direct immunofluorescence can commonly be positive for IgA, which was negative in our patient.

AHEI and HSP are considered different entities, but both present with leukocytoclastic vasculitis.1 Another condition to consider in patients with fever, rash, and edema is Kawasaki disease, also a form of vasculitis, that affects small- and medium-size muscular vessels with predilection for the coronary arteries. Patients with Kawasaki disease present with fever (usually longer than 5 days), facial and extremity edema (similar to AHEI), skin lesions (which may have multiple presentations, the most common being macular, papular and erythematous, and urticarial eruptions), but also lymphadenopathy and conjunctivitis. These patients appear sicker than children with AHEI. Their laboratory results show leukocytosis, thrombocytosis or thrombocytopenia, elevated inflammatory markers, and sterile pyuria.4

Patients with erythema nodosum present with tender erythematous nodules, which can look like early AHEI lesions. The most common location is the lower extremities, but in children erythema nodosum can occur on the face, trunk, and arms. The lesions can occur secondary to infections such as streptococcus, mycoplasma, tuberculosis, coccidioidomycosis, and sarcoidosis, as well as to malignancy or medications. These patients do not appear sick, are not febrile, and are rarely seen under 2 years of age.5

Acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis – Sweets’ syndrome – also should be considered in a patient with tender nodules, fever, and leukocytosis. The skin lesions in Sweets’ syndrome, compared with those in AHEI, are painful and can present as papules, nodules, and bullae on the face and extremities. A prior history of an upper respiratory infection is commonly described in children with Sweets’ syndrome. These patients present with fever, which may start days to weeks prior to the lesions starting. Children with Sweets’ syndrome also can have conjunctivitis, myalgias, polyarthritis, and in severe cases septic shock and multiorgan dysfunction. Sweets’ syndrome can be seen in patients with inflammatory bowel disease, systemic lupus erythematosus, chronic multifocal osteomyelitis, and malignancy; it also may be induced by certain medications.6

As mentioned above, the course of AHEI is benign, and the condition resolves within days to weeks. Treatment is supportive.

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego. She had no relevant financial disclosures. Email Dr. Matiz at pdnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. F1000Res. 2019;8:1771.

2. Pediatr Dermatol. 2006 Jul-Aug;23(4):361-4.

3. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015 Nov-Dec;32(6):e309-11.

4. Clin Dermatol. 2017 Nov-Dec;35(6):530-40.

5. Yonsei Med J. 2019 Mar;60(3):312-4.

6. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015 Jul-Aug;32(4):437-46.

A punch biopsy of one of the lesions showed a superficial and deep mixed inflammatory cell infiltrate, including neutrophils and eosinophils. There was also vasculitis, karyorrhexis and extravasated red blood cells. The findings are those of leukocytoclastic vasculitis, suggestive of acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy. Direct immunofluorescence was positive for IgM, C3, and fibrinogen, but negative for IgA.

Acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy (AHEI), also known as Finkelstein disease, is form of leukocytoclastic vasculitis that occurs in infants and toddlers aged between4 months and 3 years.

The lesions start as petechiae or edematous, erythematous to violaceous nodules that later coalesce and form “cockade”-like plaques with a central clearing on the face and extremities. Gastrointestinal, renal, and joint involvement are rare.1 AHEI follows a benign course with resolution of the lesions and symptoms within days to weeks. The etiology of this condition is not known but infection triggers have been reported including coronavirus infections, coxsackie virus infections, Escherichia coli urinary tract infections, herpes simplex virus stomatitis, and pneumococcal bacteremia.2,3 Our patient had a prior history of pneumococcal pneumonia and metapneumovirus infection. MMR vaccine also has been reported as a possible trigger, as well as some medications.

Laboratory results are usually normal, but some patients may have elevated inflammatory markers (C-reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate), as noted in our patient, and leukocytosis, thrombocytosis, and eosinophilia. Microscopic analysis demonstrates leukocytoclastic vasculitis of small vessels with associated karyorrhexis and extravasated red blood cells.

The differential diagnosis includes other vasculitic conditions, primarily Henoch-Schönlein purpura (HSP). Patients with HSP tend to be older in age and the lesions described as palpable purpura commonly affect the lower extremities and buttocks. These patients can present with abdominal pain and arthritis; renal compromise also can occur. Direct immunofluorescence can commonly be positive for IgA, which was negative in our patient.

AHEI and HSP are considered different entities, but both present with leukocytoclastic vasculitis.1 Another condition to consider in patients with fever, rash, and edema is Kawasaki disease, also a form of vasculitis, that affects small- and medium-size muscular vessels with predilection for the coronary arteries. Patients with Kawasaki disease present with fever (usually longer than 5 days), facial and extremity edema (similar to AHEI), skin lesions (which may have multiple presentations, the most common being macular, papular and erythematous, and urticarial eruptions), but also lymphadenopathy and conjunctivitis. These patients appear sicker than children with AHEI. Their laboratory results show leukocytosis, thrombocytosis or thrombocytopenia, elevated inflammatory markers, and sterile pyuria.4

Patients with erythema nodosum present with tender erythematous nodules, which can look like early AHEI lesions. The most common location is the lower extremities, but in children erythema nodosum can occur on the face, trunk, and arms. The lesions can occur secondary to infections such as streptococcus, mycoplasma, tuberculosis, coccidioidomycosis, and sarcoidosis, as well as to malignancy or medications. These patients do not appear sick, are not febrile, and are rarely seen under 2 years of age.5

Acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis – Sweets’ syndrome – also should be considered in a patient with tender nodules, fever, and leukocytosis. The skin lesions in Sweets’ syndrome, compared with those in AHEI, are painful and can present as papules, nodules, and bullae on the face and extremities. A prior history of an upper respiratory infection is commonly described in children with Sweets’ syndrome. These patients present with fever, which may start days to weeks prior to the lesions starting. Children with Sweets’ syndrome also can have conjunctivitis, myalgias, polyarthritis, and in severe cases septic shock and multiorgan dysfunction. Sweets’ syndrome can be seen in patients with inflammatory bowel disease, systemic lupus erythematosus, chronic multifocal osteomyelitis, and malignancy; it also may be induced by certain medications.6

As mentioned above, the course of AHEI is benign, and the condition resolves within days to weeks. Treatment is supportive.

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego. She had no relevant financial disclosures. Email Dr. Matiz at pdnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. F1000Res. 2019;8:1771.

2. Pediatr Dermatol. 2006 Jul-Aug;23(4):361-4.

3. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015 Nov-Dec;32(6):e309-11.

4. Clin Dermatol. 2017 Nov-Dec;35(6):530-40.

5. Yonsei Med J. 2019 Mar;60(3):312-4.

6. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015 Jul-Aug;32(4):437-46.

A punch biopsy of one of the lesions showed a superficial and deep mixed inflammatory cell infiltrate, including neutrophils and eosinophils. There was also vasculitis, karyorrhexis and extravasated red blood cells. The findings are those of leukocytoclastic vasculitis, suggestive of acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy. Direct immunofluorescence was positive for IgM, C3, and fibrinogen, but negative for IgA.

Acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy (AHEI), also known as Finkelstein disease, is form of leukocytoclastic vasculitis that occurs in infants and toddlers aged between4 months and 3 years.

The lesions start as petechiae or edematous, erythematous to violaceous nodules that later coalesce and form “cockade”-like plaques with a central clearing on the face and extremities. Gastrointestinal, renal, and joint involvement are rare.1 AHEI follows a benign course with resolution of the lesions and symptoms within days to weeks. The etiology of this condition is not known but infection triggers have been reported including coronavirus infections, coxsackie virus infections, Escherichia coli urinary tract infections, herpes simplex virus stomatitis, and pneumococcal bacteremia.2,3 Our patient had a prior history of pneumococcal pneumonia and metapneumovirus infection. MMR vaccine also has been reported as a possible trigger, as well as some medications.

Laboratory results are usually normal, but some patients may have elevated inflammatory markers (C-reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate), as noted in our patient, and leukocytosis, thrombocytosis, and eosinophilia. Microscopic analysis demonstrates leukocytoclastic vasculitis of small vessels with associated karyorrhexis and extravasated red blood cells.

The differential diagnosis includes other vasculitic conditions, primarily Henoch-Schönlein purpura (HSP). Patients with HSP tend to be older in age and the lesions described as palpable purpura commonly affect the lower extremities and buttocks. These patients can present with abdominal pain and arthritis; renal compromise also can occur. Direct immunofluorescence can commonly be positive for IgA, which was negative in our patient.

AHEI and HSP are considered different entities, but both present with leukocytoclastic vasculitis.1 Another condition to consider in patients with fever, rash, and edema is Kawasaki disease, also a form of vasculitis, that affects small- and medium-size muscular vessels with predilection for the coronary arteries. Patients with Kawasaki disease present with fever (usually longer than 5 days), facial and extremity edema (similar to AHEI), skin lesions (which may have multiple presentations, the most common being macular, papular and erythematous, and urticarial eruptions), but also lymphadenopathy and conjunctivitis. These patients appear sicker than children with AHEI. Their laboratory results show leukocytosis, thrombocytosis or thrombocytopenia, elevated inflammatory markers, and sterile pyuria.4

Patients with erythema nodosum present with tender erythematous nodules, which can look like early AHEI lesions. The most common location is the lower extremities, but in children erythema nodosum can occur on the face, trunk, and arms. The lesions can occur secondary to infections such as streptococcus, mycoplasma, tuberculosis, coccidioidomycosis, and sarcoidosis, as well as to malignancy or medications. These patients do not appear sick, are not febrile, and are rarely seen under 2 years of age.5

Acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis – Sweets’ syndrome – also should be considered in a patient with tender nodules, fever, and leukocytosis. The skin lesions in Sweets’ syndrome, compared with those in AHEI, are painful and can present as papules, nodules, and bullae on the face and extremities. A prior history of an upper respiratory infection is commonly described in children with Sweets’ syndrome. These patients present with fever, which may start days to weeks prior to the lesions starting. Children with Sweets’ syndrome also can have conjunctivitis, myalgias, polyarthritis, and in severe cases septic shock and multiorgan dysfunction. Sweets’ syndrome can be seen in patients with inflammatory bowel disease, systemic lupus erythematosus, chronic multifocal osteomyelitis, and malignancy; it also may be induced by certain medications.6

As mentioned above, the course of AHEI is benign, and the condition resolves within days to weeks. Treatment is supportive.

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego. She had no relevant financial disclosures. Email Dr. Matiz at pdnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. F1000Res. 2019;8:1771.

2. Pediatr Dermatol. 2006 Jul-Aug;23(4):361-4.

3. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015 Nov-Dec;32(6):e309-11.

4. Clin Dermatol. 2017 Nov-Dec;35(6):530-40.

5. Yonsei Med J. 2019 Mar;60(3):312-4.

6. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015 Jul-Aug;32(4):437-46.

At 3 a.m., you receive a call from the ED for a baby with a new rash on the arms, legs, and face. Some of the lesions appear to be tender. He has a mild fever of 38.4° C (101.1° F) and is not in acute distress. He is drinking, but not eating much.

The parents also have noted some swelling on the hands and the feet. He has no upper respiratory or gastrointestinal symptoms. He is not walking yet.

He was admitted to the hospital 3 weeks prior for streptococcal pneumonia and metapneumovirus infection. He was treated with ceftriaxone, supportive respiratory care, and an albuterol inhaler. Influenza and respiratory syncytial virus tests were negative.

On physical exam, the child is tired and sleeping in his mom's arms. He has red and some purpuric papules on the face. On the arms and legs, he has purpuric papules and nodules. There is some edema on the face, hands, and feet. His conjunctiva is normal, and he has no oral lesions. He has no lymphadenopathy or hepatosplenomegaly.

Blood work shows normal complete blood count, coagulation tests, comprehensive metabolic panel, and urinalysis, but he has an elevated C-reactive protein of 114 mg/L and an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 71 mm/hour.

Nail dystrophy and nail plate thinning

At a follow-up visit, a biopsy of the skin on the fingertips was performed, which showed lichenoid lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrate with associated hyperkeratosis, hypergranulosis, and acanthosis.

No fungal elements were seen. The findings were consistent with lichen planus.

The patient was started on hydroxychloroquine. It was recommended she start a 6-week course of oral prednisone, but the mother was opposed to systemic treatment because of potential side effects.