User login

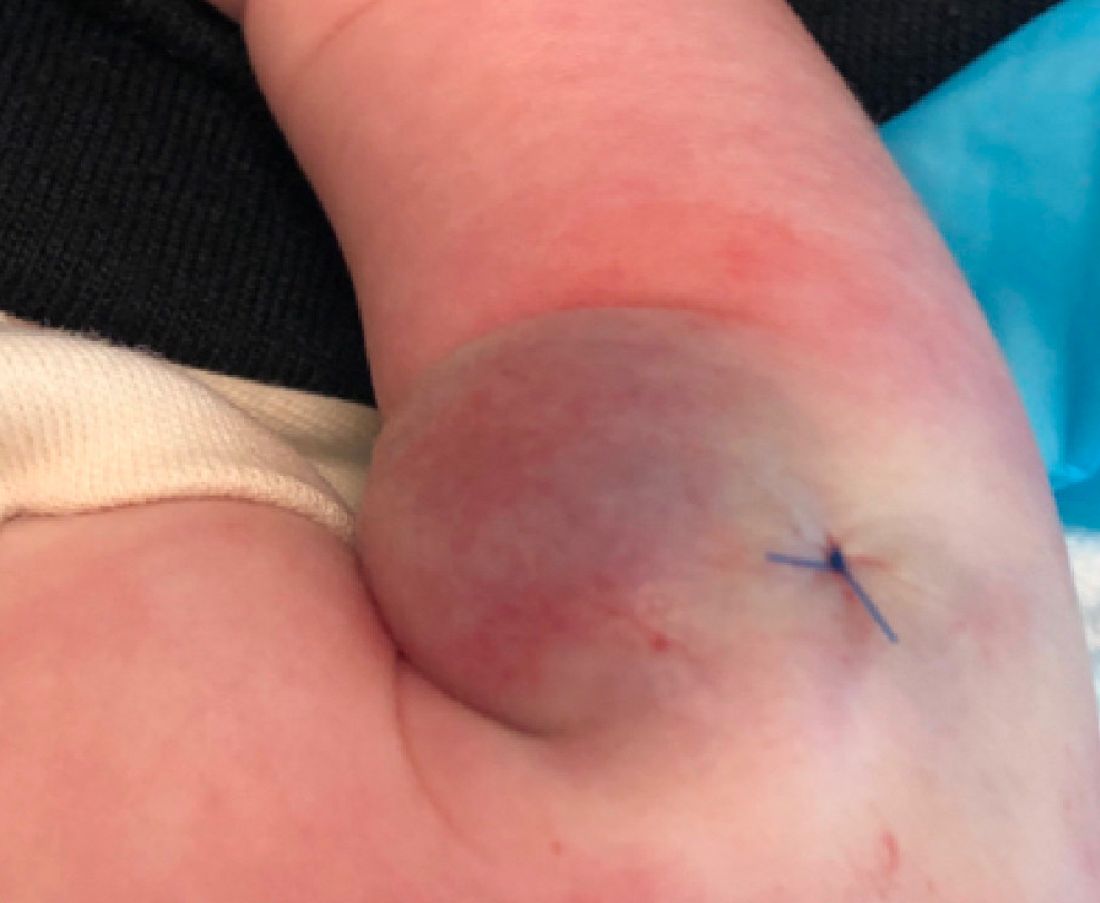

An infant with a tender bump on her ear

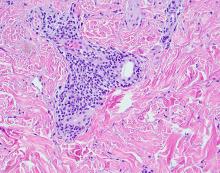

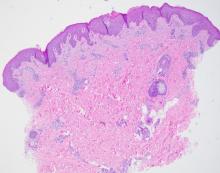

A biopsy of the lesion was performed that showed a well-defined nodulocystic tumor composed of nests of basaloid cells that are undergoing trichilemmal keratinization. Shadow cells are seen as well as small areas of calcification. There is also a histiocytic infiltrate with multinucleated giant cells. The histologic diagnosis is of a pilomatrixoma.

Pilomatrixoma, also known as calcifying epithelioma of Malherbe, was first described in 1880, as a tumor of sebaceous gland origin. Later, in 1961, Robert Forbis Jr, MD, and Elson B. Helwig, MD, coined the term pilomatrixoma to describe the hair follicle matrix as the source of the tumor. Pilomatrixomas are commonly seen in the pediatric population, usually in children between 8 and 13 years of age. Our patient is one of the youngest described. The lesions are commonly seen on the face and neck in about 70% of the cases followed by the upper extremities, back, and legs. Clinically, the lesions appear as a firm dermal papule or nodule, which moves freely and may have associated erythema on the skin surface or a blueish gray hue on the underlying skin.

Most pilomatrixomas that have been studied have shown a mutation in Exon 3 of the beta-catenin gene (CTNNB1). The beta-catenin molecule is a subunit of the cadherin protein, which is part of an important pathway in the terminal hair follicle differentiation. Beta-catenin also plays an important role in the Wnt pathway, which regulates cell fate as well as early embryonic patterning. Beta-catenin is responsible for forming adhesion junctions among cells. There have also been immunohistochemical studies that have shown a BCL2 proto-oncogene overexpression to pilomatrixoma.

There are several genetic syndromes that have been associated with the presence of pilomatrixomas: Turner syndrome (XO chromosome abnormality associated with short stature and cardiac defects), Gardner syndrome (polyposis coli and colon and rectal cancer), myotonic dystrophy, Rubinstein-Taybi syndrome (characterized by broad thumbs and toes, short stature, distinctive facial features, and varying degrees of intellectual disability), and trisomy 9. On physical examination our patient didn’t present with any of the typical features or history that could suggest any of these syndromes. A close follow-up and evaluation by a geneticist was recommended because after the initial visit she developed a second lesion on the forehead.

The differential diagnosis for this lesion includes other cysts that may occur on the ear such as epidermal inclusion cyst or dermoid cysts, though these lesions do not tend to be as firm as pilomatrixomas are, which can help with the diagnosis. Dermoid cysts are made of dermal and epidermal components. They are usually present at birth and are commonly seen on the scalp and the periorbital face.

Keloids are rubbery nodules of scar tissue that can form on sites of trauma, and although the lesion occurred after she had her ears pierced, the consistency and rapid growth of the lesion as well as the pathological description made this benign fibrous growth less likely.

When pilomatrixomas are inflamed they can be confused with vascular growths: in this particular case, a hemangioma or another vascular tumor such as a tufted angioma or kaposiform hemangioendothelioma. An ultrasound of the lesion could have helped in the differential diagnosis of the lesion.

Pilomatrixomas can grow significantly and in some cases get inflamed or infected. Surgical management of pilomatrixomas is often required because the lesions do not regress spontaneously.

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego.

References

Forbis R Jr and Helwig EB. Arch Dermatol 1961;83:606-18.

Schwarz Y et al. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2016 Jun;85:148-53.

A biopsy of the lesion was performed that showed a well-defined nodulocystic tumor composed of nests of basaloid cells that are undergoing trichilemmal keratinization. Shadow cells are seen as well as small areas of calcification. There is also a histiocytic infiltrate with multinucleated giant cells. The histologic diagnosis is of a pilomatrixoma.

Pilomatrixoma, also known as calcifying epithelioma of Malherbe, was first described in 1880, as a tumor of sebaceous gland origin. Later, in 1961, Robert Forbis Jr, MD, and Elson B. Helwig, MD, coined the term pilomatrixoma to describe the hair follicle matrix as the source of the tumor. Pilomatrixomas are commonly seen in the pediatric population, usually in children between 8 and 13 years of age. Our patient is one of the youngest described. The lesions are commonly seen on the face and neck in about 70% of the cases followed by the upper extremities, back, and legs. Clinically, the lesions appear as a firm dermal papule or nodule, which moves freely and may have associated erythema on the skin surface or a blueish gray hue on the underlying skin.

Most pilomatrixomas that have been studied have shown a mutation in Exon 3 of the beta-catenin gene (CTNNB1). The beta-catenin molecule is a subunit of the cadherin protein, which is part of an important pathway in the terminal hair follicle differentiation. Beta-catenin also plays an important role in the Wnt pathway, which regulates cell fate as well as early embryonic patterning. Beta-catenin is responsible for forming adhesion junctions among cells. There have also been immunohistochemical studies that have shown a BCL2 proto-oncogene overexpression to pilomatrixoma.

There are several genetic syndromes that have been associated with the presence of pilomatrixomas: Turner syndrome (XO chromosome abnormality associated with short stature and cardiac defects), Gardner syndrome (polyposis coli and colon and rectal cancer), myotonic dystrophy, Rubinstein-Taybi syndrome (characterized by broad thumbs and toes, short stature, distinctive facial features, and varying degrees of intellectual disability), and trisomy 9. On physical examination our patient didn’t present with any of the typical features or history that could suggest any of these syndromes. A close follow-up and evaluation by a geneticist was recommended because after the initial visit she developed a second lesion on the forehead.

The differential diagnosis for this lesion includes other cysts that may occur on the ear such as epidermal inclusion cyst or dermoid cysts, though these lesions do not tend to be as firm as pilomatrixomas are, which can help with the diagnosis. Dermoid cysts are made of dermal and epidermal components. They are usually present at birth and are commonly seen on the scalp and the periorbital face.

Keloids are rubbery nodules of scar tissue that can form on sites of trauma, and although the lesion occurred after she had her ears pierced, the consistency and rapid growth of the lesion as well as the pathological description made this benign fibrous growth less likely.

When pilomatrixomas are inflamed they can be confused with vascular growths: in this particular case, a hemangioma or another vascular tumor such as a tufted angioma or kaposiform hemangioendothelioma. An ultrasound of the lesion could have helped in the differential diagnosis of the lesion.

Pilomatrixomas can grow significantly and in some cases get inflamed or infected. Surgical management of pilomatrixomas is often required because the lesions do not regress spontaneously.

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego.

References

Forbis R Jr and Helwig EB. Arch Dermatol 1961;83:606-18.

Schwarz Y et al. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2016 Jun;85:148-53.

A biopsy of the lesion was performed that showed a well-defined nodulocystic tumor composed of nests of basaloid cells that are undergoing trichilemmal keratinization. Shadow cells are seen as well as small areas of calcification. There is also a histiocytic infiltrate with multinucleated giant cells. The histologic diagnosis is of a pilomatrixoma.

Pilomatrixoma, also known as calcifying epithelioma of Malherbe, was first described in 1880, as a tumor of sebaceous gland origin. Later, in 1961, Robert Forbis Jr, MD, and Elson B. Helwig, MD, coined the term pilomatrixoma to describe the hair follicle matrix as the source of the tumor. Pilomatrixomas are commonly seen in the pediatric population, usually in children between 8 and 13 years of age. Our patient is one of the youngest described. The lesions are commonly seen on the face and neck in about 70% of the cases followed by the upper extremities, back, and legs. Clinically, the lesions appear as a firm dermal papule or nodule, which moves freely and may have associated erythema on the skin surface or a blueish gray hue on the underlying skin.

Most pilomatrixomas that have been studied have shown a mutation in Exon 3 of the beta-catenin gene (CTNNB1). The beta-catenin molecule is a subunit of the cadherin protein, which is part of an important pathway in the terminal hair follicle differentiation. Beta-catenin also plays an important role in the Wnt pathway, which regulates cell fate as well as early embryonic patterning. Beta-catenin is responsible for forming adhesion junctions among cells. There have also been immunohistochemical studies that have shown a BCL2 proto-oncogene overexpression to pilomatrixoma.

There are several genetic syndromes that have been associated with the presence of pilomatrixomas: Turner syndrome (XO chromosome abnormality associated with short stature and cardiac defects), Gardner syndrome (polyposis coli and colon and rectal cancer), myotonic dystrophy, Rubinstein-Taybi syndrome (characterized by broad thumbs and toes, short stature, distinctive facial features, and varying degrees of intellectual disability), and trisomy 9. On physical examination our patient didn’t present with any of the typical features or history that could suggest any of these syndromes. A close follow-up and evaluation by a geneticist was recommended because after the initial visit she developed a second lesion on the forehead.

The differential diagnosis for this lesion includes other cysts that may occur on the ear such as epidermal inclusion cyst or dermoid cysts, though these lesions do not tend to be as firm as pilomatrixomas are, which can help with the diagnosis. Dermoid cysts are made of dermal and epidermal components. They are usually present at birth and are commonly seen on the scalp and the periorbital face.

Keloids are rubbery nodules of scar tissue that can form on sites of trauma, and although the lesion occurred after she had her ears pierced, the consistency and rapid growth of the lesion as well as the pathological description made this benign fibrous growth less likely.

When pilomatrixomas are inflamed they can be confused with vascular growths: in this particular case, a hemangioma or another vascular tumor such as a tufted angioma or kaposiform hemangioendothelioma. An ultrasound of the lesion could have helped in the differential diagnosis of the lesion.

Pilomatrixomas can grow significantly and in some cases get inflamed or infected. Surgical management of pilomatrixomas is often required because the lesions do not regress spontaneously.

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego.

References

Forbis R Jr and Helwig EB. Arch Dermatol 1961;83:606-18.

Schwarz Y et al. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2016 Jun;85:148-53.

A 4-month-old female was referred to our clinic for evaluation of a bump on the right ear. The lesion was first noted at 2 months of age as a little pimple. She was evaluated by her pediatrician and was treated with topical and oral antibiotics without resolution of the lesion. The bump continued to grow and seemed tender to palpation, so she was referred to dermatology for evaluation.

She was born via normal vaginal delivery at 40 weeks. Her mother has no medical conditions and the pregnancy was uneventful. She has been growing and developing well. She takes vitamin D and is currently breast fed.

There have been no other family members with similar lesions. She had her ears pierced at a month of age without any complications.

On skin examination she has a firm red nodule on the right ear that appears slightly tender to touch. She has no other skin lesions of concern. She has normal muscle tone and there are no other abnormalities noted on the physical exam. She has no hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, or lymphadenopathy.

A 9-year-old girl was evaluated for a week-long history of rash on the feet

A complete body examination failed to reveal any other lesions suggestive of a fungal infection. A blood count and urinalysis were within normal limits. She had no lymphadenopathy or hepatosplenomegaly. She was diagnosed with cutaneous larva migrans (CLM) given the clinical appearance of the lesions and the recent travel history.

CLM is a zoonotic infection caused by several hookworms such as Ancylostoma braziliense, Ancylostoma caninum, and Uncinaria stenocephala, as well as human hookworms such as Ancylostoma duodenale and Necator americanus. The hookworms can be present in contaminated soils and sandy beaches on the coastal regions of South America, the Caribbean, the Southeastern United States, Southeast Asia, and Africa.1-5

It is a common disease in the tourist population visiting tropical countries because of exposure to the hookworms in the soil without use of proper foot protection.

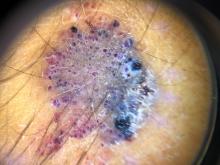

The clinical features are of an erythematous linear serpiginous plaque that is pruritic and can progress from millimeters to centimeters in size within a few days to weeks. Vesicles and multiple tracks can also be seen. The most common locations are the feet, buttocks, and thighs.

The larvae in the soil come from eggs excreted in the feces of infected cats and dogs. The infection is caused by direct contact of the larvae with the stratum corneum of the skin creating a burrow and an inflammatory response that will cause erythema, edema, track formation, and pruritus.

Diagnosis is made clinically. Rarely, a skin biopsy is warranted. The differential diagnosis includes tinea pedis, granuloma annulare, larva currens, contact dermatitis, and herpes zoster.

Tinea pedis is a fungal infection of the skin of the feet, commonly localized on the web spaces. The risk factors are a hot and humid environment, prolonged wear of occlusive footwear, excess sweating, and prolonged exposure to water.6 Diagnosis is confirmed by microscopic evaluation of skin scrapings with potassium hydroxide or a fungal culture. The infection is treated with topical antifungal creams and, in severe cases, systemic antifungals. Granuloma annulare is a benign chronic skin condition that presents with annular-shaped lesions. Its etiology is unknown. The lesions may be asymptomatic or mildly pruritic. Localized granuloma annulare typically presents as reddish-brown papules or plaques on the fingers, hands, elbows, dorsal feet, or ankles. The feature distinguishing granuloma annulare from other annular lesions is its absence of scale.

Allergic contact dermatitis is caused by skin exposure to an allergen and a secondary inflammatory response to this material on the skin causing inflammation, vesiculation, and pruritus. Lesions are treated with topical corticosteroids and avoidance of the allergen.

Herpes zoster is caused by a viral infection of the latent varicella-zoster virus. Its reactivation causes the presence of vesicles with an erythematous base that have a dermatomal distribution. The lesions are usually tender. Treatment is recommended to be started within 72 hours of the eruption with antivirals such as acyclovir or valacyclovir.

Cutaneous larva currens is caused by the cutaneous infection with Strongyloides stercoralis. In comparison with CLM, the lesions progress faster, at up to a centimeter within hours.

CLM is usually self-limited. If the patient has multiple lesions or more severe disease, oral albendazole or ivermectin can be prescribed. Other treatments, though not preferred, include freezing and topical thiabendazole solutions.

As our patient had several lesions, oral ivermectin was chosen as treatment and the lesions cleared within a week. Also, she was recommended to always wear shoes when walking on the beach.

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego. Dr. Valderrama is a pediatric dermatologist at Fundación Cardioinfantil, Bogota, Colombia.

References

1. Feldmeier H and Schuster A. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2012 Jun;31(6):915-8.

2. Jacobson CC and Abel EA. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007 Jun;56(6):1026-43.

3. Kincaid L et al. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2015 Sep-Oct;13(5):382-7.

4. Gill N et al. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2020 Jul;33(7):356-9.

5. Rodenas-Herranz T et al. Dermatol Ther. 2020 May;33(3):e13316.

6. Pramod K et al. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (Fla): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan.

A complete body examination failed to reveal any other lesions suggestive of a fungal infection. A blood count and urinalysis were within normal limits. She had no lymphadenopathy or hepatosplenomegaly. She was diagnosed with cutaneous larva migrans (CLM) given the clinical appearance of the lesions and the recent travel history.

CLM is a zoonotic infection caused by several hookworms such as Ancylostoma braziliense, Ancylostoma caninum, and Uncinaria stenocephala, as well as human hookworms such as Ancylostoma duodenale and Necator americanus. The hookworms can be present in contaminated soils and sandy beaches on the coastal regions of South America, the Caribbean, the Southeastern United States, Southeast Asia, and Africa.1-5

It is a common disease in the tourist population visiting tropical countries because of exposure to the hookworms in the soil without use of proper foot protection.

The clinical features are of an erythematous linear serpiginous plaque that is pruritic and can progress from millimeters to centimeters in size within a few days to weeks. Vesicles and multiple tracks can also be seen. The most common locations are the feet, buttocks, and thighs.

The larvae in the soil come from eggs excreted in the feces of infected cats and dogs. The infection is caused by direct contact of the larvae with the stratum corneum of the skin creating a burrow and an inflammatory response that will cause erythema, edema, track formation, and pruritus.

Diagnosis is made clinically. Rarely, a skin biopsy is warranted. The differential diagnosis includes tinea pedis, granuloma annulare, larva currens, contact dermatitis, and herpes zoster.

Tinea pedis is a fungal infection of the skin of the feet, commonly localized on the web spaces. The risk factors are a hot and humid environment, prolonged wear of occlusive footwear, excess sweating, and prolonged exposure to water.6 Diagnosis is confirmed by microscopic evaluation of skin scrapings with potassium hydroxide or a fungal culture. The infection is treated with topical antifungal creams and, in severe cases, systemic antifungals. Granuloma annulare is a benign chronic skin condition that presents with annular-shaped lesions. Its etiology is unknown. The lesions may be asymptomatic or mildly pruritic. Localized granuloma annulare typically presents as reddish-brown papules or plaques on the fingers, hands, elbows, dorsal feet, or ankles. The feature distinguishing granuloma annulare from other annular lesions is its absence of scale.

Allergic contact dermatitis is caused by skin exposure to an allergen and a secondary inflammatory response to this material on the skin causing inflammation, vesiculation, and pruritus. Lesions are treated with topical corticosteroids and avoidance of the allergen.

Herpes zoster is caused by a viral infection of the latent varicella-zoster virus. Its reactivation causes the presence of vesicles with an erythematous base that have a dermatomal distribution. The lesions are usually tender. Treatment is recommended to be started within 72 hours of the eruption with antivirals such as acyclovir or valacyclovir.

Cutaneous larva currens is caused by the cutaneous infection with Strongyloides stercoralis. In comparison with CLM, the lesions progress faster, at up to a centimeter within hours.

CLM is usually self-limited. If the patient has multiple lesions or more severe disease, oral albendazole or ivermectin can be prescribed. Other treatments, though not preferred, include freezing and topical thiabendazole solutions.

As our patient had several lesions, oral ivermectin was chosen as treatment and the lesions cleared within a week. Also, she was recommended to always wear shoes when walking on the beach.

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego. Dr. Valderrama is a pediatric dermatologist at Fundación Cardioinfantil, Bogota, Colombia.

References

1. Feldmeier H and Schuster A. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2012 Jun;31(6):915-8.

2. Jacobson CC and Abel EA. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007 Jun;56(6):1026-43.

3. Kincaid L et al. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2015 Sep-Oct;13(5):382-7.

4. Gill N et al. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2020 Jul;33(7):356-9.

5. Rodenas-Herranz T et al. Dermatol Ther. 2020 May;33(3):e13316.

6. Pramod K et al. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (Fla): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan.

A complete body examination failed to reveal any other lesions suggestive of a fungal infection. A blood count and urinalysis were within normal limits. She had no lymphadenopathy or hepatosplenomegaly. She was diagnosed with cutaneous larva migrans (CLM) given the clinical appearance of the lesions and the recent travel history.

CLM is a zoonotic infection caused by several hookworms such as Ancylostoma braziliense, Ancylostoma caninum, and Uncinaria stenocephala, as well as human hookworms such as Ancylostoma duodenale and Necator americanus. The hookworms can be present in contaminated soils and sandy beaches on the coastal regions of South America, the Caribbean, the Southeastern United States, Southeast Asia, and Africa.1-5

It is a common disease in the tourist population visiting tropical countries because of exposure to the hookworms in the soil without use of proper foot protection.

The clinical features are of an erythematous linear serpiginous plaque that is pruritic and can progress from millimeters to centimeters in size within a few days to weeks. Vesicles and multiple tracks can also be seen. The most common locations are the feet, buttocks, and thighs.

The larvae in the soil come from eggs excreted in the feces of infected cats and dogs. The infection is caused by direct contact of the larvae with the stratum corneum of the skin creating a burrow and an inflammatory response that will cause erythema, edema, track formation, and pruritus.

Diagnosis is made clinically. Rarely, a skin biopsy is warranted. The differential diagnosis includes tinea pedis, granuloma annulare, larva currens, contact dermatitis, and herpes zoster.

Tinea pedis is a fungal infection of the skin of the feet, commonly localized on the web spaces. The risk factors are a hot and humid environment, prolonged wear of occlusive footwear, excess sweating, and prolonged exposure to water.6 Diagnosis is confirmed by microscopic evaluation of skin scrapings with potassium hydroxide or a fungal culture. The infection is treated with topical antifungal creams and, in severe cases, systemic antifungals. Granuloma annulare is a benign chronic skin condition that presents with annular-shaped lesions. Its etiology is unknown. The lesions may be asymptomatic or mildly pruritic. Localized granuloma annulare typically presents as reddish-brown papules or plaques on the fingers, hands, elbows, dorsal feet, or ankles. The feature distinguishing granuloma annulare from other annular lesions is its absence of scale.

Allergic contact dermatitis is caused by skin exposure to an allergen and a secondary inflammatory response to this material on the skin causing inflammation, vesiculation, and pruritus. Lesions are treated with topical corticosteroids and avoidance of the allergen.

Herpes zoster is caused by a viral infection of the latent varicella-zoster virus. Its reactivation causes the presence of vesicles with an erythematous base that have a dermatomal distribution. The lesions are usually tender. Treatment is recommended to be started within 72 hours of the eruption with antivirals such as acyclovir or valacyclovir.

Cutaneous larva currens is caused by the cutaneous infection with Strongyloides stercoralis. In comparison with CLM, the lesions progress faster, at up to a centimeter within hours.

CLM is usually self-limited. If the patient has multiple lesions or more severe disease, oral albendazole or ivermectin can be prescribed. Other treatments, though not preferred, include freezing and topical thiabendazole solutions.

As our patient had several lesions, oral ivermectin was chosen as treatment and the lesions cleared within a week. Also, she was recommended to always wear shoes when walking on the beach.

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego. Dr. Valderrama is a pediatric dermatologist at Fundación Cardioinfantil, Bogota, Colombia.

References

1. Feldmeier H and Schuster A. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2012 Jun;31(6):915-8.

2. Jacobson CC and Abel EA. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007 Jun;56(6):1026-43.

3. Kincaid L et al. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2015 Sep-Oct;13(5):382-7.

4. Gill N et al. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2020 Jul;33(7):356-9.

5. Rodenas-Herranz T et al. Dermatol Ther. 2020 May;33(3):e13316.

6. Pramod K et al. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (Fla): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan.

Her mother reported recent travel to a beachside city in Colombia. A review of systems was negative. She was not taking any other medications or vitamin supplements. There were no pets at home and no other affected family members. Physical exam was notable for an erythematous curvilinear plaque on the feet and a small vesicle.

Adolescent female with rash on the arms and posterior legs

Erythema annulare centrifugum

A thorough body examination failed to reveal any other rashes or lesions suggestive of a fungal infection. A blood count and urinalysis were within normal limits. She had no lymphadenopathy or hepatosplenomegaly. A potassium hydroxide analysis of skin scrapings was negative for fungal elements. Punch biopsy of the skin on the left arm revealed focal intermittent parakeratosis, mildly acanthotic and spongiotic epidermis, and a tight superficial perivascular chronic dermatitis consisting of lymphocytes and histiocytes (Figures). Given these findings, a diagnosis of erythema annulare centrifugum (EAC) was rendered.

EAC is a rare, reactive skin rash characterized by redness (erythema) and ring-shaped lesions (annulare) that slowly spread from the center (centrifugum). The lesions present with a characteristic trailing scale on the inner border of the erythematous ring. Lesions may be asymptomatic or mildly pruritic and commonly involve the trunk, buttocks, hips, and upper legs. It is important to note that its duration is highly variable, ranging from weeks to decades, with most cases persisting for 9 months. EAC typically affects young or middle-aged adults but can occur at any age.

Although the etiology of EAC is unknown, it is believed to be a hypersensitivity reaction to a foreign antigen. Cutaneous fungal infections are commonly reported as triggers as well as other viral infections, medications, malignancy, underlying systemic disease, and certain foods. Treatment depends on the underlying condition and removing the implicated agent. However, most cases of EAC are idiopathic and self-limiting. It is possible that our patient’s prior history of tinea capitis could have triggered the skin lesions suggestive of EAC, but interestingly, these lesions did not go away after the fungal infection was cleared and have continued to recur. For patients with refractory lesions or treatment of patients without an identifiable cause, the use of oral antimicrobials has been proposed. Medications such as azithromycin, erythromycin, fluconazole, and metronidazole have been reported to be helpful in some patients with refractory EAC. Our patient wanted to continue topical treatment with betamethasone as needed and may consider antimicrobial therapy if the lesions continue to recur.

Tinea corporis refers to a superficial fungal infection of the skin. It may present as one or more asymmetrical, annular, pruritic plaques with a raised scaly leading edge rather than the trailing scale seen with EAC. Diagnosis is made by KOH examination of skin scrapings. Common risk factors include close contact with an infected person or animal, warm, moist environments, sharing personal items, and prolonged use of systemic corticosteroids. Our patient’s KOH analysis of skin scrapings was negative for fungal elements.

Erythema marginatum is a rare skin rash commonly seen with acute rheumatic fever secondary to streptococcal infection. It presents as annular erythematous lesions on the trunk and proximal extremities that are exacerbated by heat. It is often associated with active carditis related to rheumatic fever. This self-limited rash usually resolves in 2-3 days. Our patient was asymptomatic without involvement of other organs.

Like EAC, granuloma annulare is a benign chronic skin condition that presents with ring-shaped lesions. Its etiology is unknown, and lesions may be asymptomatic or mildly pruritic. Localized granuloma annulare typically presents as reddish-brown papules or plaques on the fingers, hands, elbows, dorsal feet, or ankles. The distinguishing feature of granuloma annulare from other annular lesions is its absence of scale.

Urticaria multiforme is an allergic hypersensitivity reaction commonly linked to viral infections, medications, and immunizations. Clinical features include blanchable annular/polycyclic lesions with a central purplish or dusky hue. Diagnostic pearls include the presence of pruritus, dermatographism, and individual lesions that resolve within 24 hours, all of which were not found in our patient’s case.

Ms. Laborada is a pediatric dermatology research associate in the division of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at the University of California, San Diego, and Rady Children’s Hospital. Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego. Ms. Laborada and Dr. Matiz have no relevant financial disclosures.

References

1. Paller A and Mancini AJ. Hurwitz Clinical Pediatric Dermatology: A Textbook of Skin Disorders of Childhood and Adolescence. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders, 2011.

2. McDaniel B and Cook C. “Erythema annulare centrifugum” 2021 Aug 27. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island, Fla.: StatPearls Publishing, 2022 Jan. PMID: 29494101.

3. Leung AK e al. Drugs Context. 2020 Jul 20;9:5-6.

4. Majmundar VD and Nagalli S. “Erythema marginatum” 2022 May 8. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island, Fla.: StatPearls Publishing, 2022 Jan.

5. Piette EW and Rosenbach M. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016 Sep;75(3):467-79.

6. Barros M et al. BMJ Case Rep. 2021 Jan 28;14(1):e241011.

Erythema annulare centrifugum

A thorough body examination failed to reveal any other rashes or lesions suggestive of a fungal infection. A blood count and urinalysis were within normal limits. She had no lymphadenopathy or hepatosplenomegaly. A potassium hydroxide analysis of skin scrapings was negative for fungal elements. Punch biopsy of the skin on the left arm revealed focal intermittent parakeratosis, mildly acanthotic and spongiotic epidermis, and a tight superficial perivascular chronic dermatitis consisting of lymphocytes and histiocytes (Figures). Given these findings, a diagnosis of erythema annulare centrifugum (EAC) was rendered.

EAC is a rare, reactive skin rash characterized by redness (erythema) and ring-shaped lesions (annulare) that slowly spread from the center (centrifugum). The lesions present with a characteristic trailing scale on the inner border of the erythematous ring. Lesions may be asymptomatic or mildly pruritic and commonly involve the trunk, buttocks, hips, and upper legs. It is important to note that its duration is highly variable, ranging from weeks to decades, with most cases persisting for 9 months. EAC typically affects young or middle-aged adults but can occur at any age.

Although the etiology of EAC is unknown, it is believed to be a hypersensitivity reaction to a foreign antigen. Cutaneous fungal infections are commonly reported as triggers as well as other viral infections, medications, malignancy, underlying systemic disease, and certain foods. Treatment depends on the underlying condition and removing the implicated agent. However, most cases of EAC are idiopathic and self-limiting. It is possible that our patient’s prior history of tinea capitis could have triggered the skin lesions suggestive of EAC, but interestingly, these lesions did not go away after the fungal infection was cleared and have continued to recur. For patients with refractory lesions or treatment of patients without an identifiable cause, the use of oral antimicrobials has been proposed. Medications such as azithromycin, erythromycin, fluconazole, and metronidazole have been reported to be helpful in some patients with refractory EAC. Our patient wanted to continue topical treatment with betamethasone as needed and may consider antimicrobial therapy if the lesions continue to recur.

Tinea corporis refers to a superficial fungal infection of the skin. It may present as one or more asymmetrical, annular, pruritic plaques with a raised scaly leading edge rather than the trailing scale seen with EAC. Diagnosis is made by KOH examination of skin scrapings. Common risk factors include close contact with an infected person or animal, warm, moist environments, sharing personal items, and prolonged use of systemic corticosteroids. Our patient’s KOH analysis of skin scrapings was negative for fungal elements.

Erythema marginatum is a rare skin rash commonly seen with acute rheumatic fever secondary to streptococcal infection. It presents as annular erythematous lesions on the trunk and proximal extremities that are exacerbated by heat. It is often associated with active carditis related to rheumatic fever. This self-limited rash usually resolves in 2-3 days. Our patient was asymptomatic without involvement of other organs.

Like EAC, granuloma annulare is a benign chronic skin condition that presents with ring-shaped lesions. Its etiology is unknown, and lesions may be asymptomatic or mildly pruritic. Localized granuloma annulare typically presents as reddish-brown papules or plaques on the fingers, hands, elbows, dorsal feet, or ankles. The distinguishing feature of granuloma annulare from other annular lesions is its absence of scale.

Urticaria multiforme is an allergic hypersensitivity reaction commonly linked to viral infections, medications, and immunizations. Clinical features include blanchable annular/polycyclic lesions with a central purplish or dusky hue. Diagnostic pearls include the presence of pruritus, dermatographism, and individual lesions that resolve within 24 hours, all of which were not found in our patient’s case.

Ms. Laborada is a pediatric dermatology research associate in the division of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at the University of California, San Diego, and Rady Children’s Hospital. Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego. Ms. Laborada and Dr. Matiz have no relevant financial disclosures.

References

1. Paller A and Mancini AJ. Hurwitz Clinical Pediatric Dermatology: A Textbook of Skin Disorders of Childhood and Adolescence. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders, 2011.

2. McDaniel B and Cook C. “Erythema annulare centrifugum” 2021 Aug 27. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island, Fla.: StatPearls Publishing, 2022 Jan. PMID: 29494101.

3. Leung AK e al. Drugs Context. 2020 Jul 20;9:5-6.

4. Majmundar VD and Nagalli S. “Erythema marginatum” 2022 May 8. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island, Fla.: StatPearls Publishing, 2022 Jan.

5. Piette EW and Rosenbach M. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016 Sep;75(3):467-79.

6. Barros M et al. BMJ Case Rep. 2021 Jan 28;14(1):e241011.

Erythema annulare centrifugum

A thorough body examination failed to reveal any other rashes or lesions suggestive of a fungal infection. A blood count and urinalysis were within normal limits. She had no lymphadenopathy or hepatosplenomegaly. A potassium hydroxide analysis of skin scrapings was negative for fungal elements. Punch biopsy of the skin on the left arm revealed focal intermittent parakeratosis, mildly acanthotic and spongiotic epidermis, and a tight superficial perivascular chronic dermatitis consisting of lymphocytes and histiocytes (Figures). Given these findings, a diagnosis of erythema annulare centrifugum (EAC) was rendered.

EAC is a rare, reactive skin rash characterized by redness (erythema) and ring-shaped lesions (annulare) that slowly spread from the center (centrifugum). The lesions present with a characteristic trailing scale on the inner border of the erythematous ring. Lesions may be asymptomatic or mildly pruritic and commonly involve the trunk, buttocks, hips, and upper legs. It is important to note that its duration is highly variable, ranging from weeks to decades, with most cases persisting for 9 months. EAC typically affects young or middle-aged adults but can occur at any age.

Although the etiology of EAC is unknown, it is believed to be a hypersensitivity reaction to a foreign antigen. Cutaneous fungal infections are commonly reported as triggers as well as other viral infections, medications, malignancy, underlying systemic disease, and certain foods. Treatment depends on the underlying condition and removing the implicated agent. However, most cases of EAC are idiopathic and self-limiting. It is possible that our patient’s prior history of tinea capitis could have triggered the skin lesions suggestive of EAC, but interestingly, these lesions did not go away after the fungal infection was cleared and have continued to recur. For patients with refractory lesions or treatment of patients without an identifiable cause, the use of oral antimicrobials has been proposed. Medications such as azithromycin, erythromycin, fluconazole, and metronidazole have been reported to be helpful in some patients with refractory EAC. Our patient wanted to continue topical treatment with betamethasone as needed and may consider antimicrobial therapy if the lesions continue to recur.

Tinea corporis refers to a superficial fungal infection of the skin. It may present as one or more asymmetrical, annular, pruritic plaques with a raised scaly leading edge rather than the trailing scale seen with EAC. Diagnosis is made by KOH examination of skin scrapings. Common risk factors include close contact with an infected person or animal, warm, moist environments, sharing personal items, and prolonged use of systemic corticosteroids. Our patient’s KOH analysis of skin scrapings was negative for fungal elements.

Erythema marginatum is a rare skin rash commonly seen with acute rheumatic fever secondary to streptococcal infection. It presents as annular erythematous lesions on the trunk and proximal extremities that are exacerbated by heat. It is often associated with active carditis related to rheumatic fever. This self-limited rash usually resolves in 2-3 days. Our patient was asymptomatic without involvement of other organs.

Like EAC, granuloma annulare is a benign chronic skin condition that presents with ring-shaped lesions. Its etiology is unknown, and lesions may be asymptomatic or mildly pruritic. Localized granuloma annulare typically presents as reddish-brown papules or plaques on the fingers, hands, elbows, dorsal feet, or ankles. The distinguishing feature of granuloma annulare from other annular lesions is its absence of scale.

Urticaria multiforme is an allergic hypersensitivity reaction commonly linked to viral infections, medications, and immunizations. Clinical features include blanchable annular/polycyclic lesions with a central purplish or dusky hue. Diagnostic pearls include the presence of pruritus, dermatographism, and individual lesions that resolve within 24 hours, all of which were not found in our patient’s case.

Ms. Laborada is a pediatric dermatology research associate in the division of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at the University of California, San Diego, and Rady Children’s Hospital. Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego. Ms. Laborada and Dr. Matiz have no relevant financial disclosures.

References

1. Paller A and Mancini AJ. Hurwitz Clinical Pediatric Dermatology: A Textbook of Skin Disorders of Childhood and Adolescence. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders, 2011.

2. McDaniel B and Cook C. “Erythema annulare centrifugum” 2021 Aug 27. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island, Fla.: StatPearls Publishing, 2022 Jan. PMID: 29494101.

3. Leung AK e al. Drugs Context. 2020 Jul 20;9:5-6.

4. Majmundar VD and Nagalli S. “Erythema marginatum” 2022 May 8. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island, Fla.: StatPearls Publishing, 2022 Jan.

5. Piette EW and Rosenbach M. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016 Sep;75(3):467-79.

6. Barros M et al. BMJ Case Rep. 2021 Jan 28;14(1):e241011.

A review of systems was noncontributory. She was not taking any other medications or vitamin supplements. There were no pets at home and no other affected family members. Physical exam was notable for scattered, pink, annular plaques with central clearing, faint brownish pigmentation, and fine scale.

A 14-year-old male presents to clinic with a new-onset rash of the hands

Photosensitivity due to doxycycline

As the patient’s rash presented in sun-exposed areas with both skin and nail changes, our patient was diagnosed with a phototoxic reaction to doxycycline, the oral antibiotic used to treat his acne.

Photosensitive cutaneous drug eruptions are reactions that occur after exposure to a medication and subsequent exposure to UV radiation or visible light. Reactions can be classified into two ways based on their mechanism of action: phototoxic or photoallergic.1 Phototoxic reactions are more common and are a result of direct keratinocyte damage and cellular necrosis. Many classes of medications may cause this adverse effect, but the tetracycline class of antibiotics is a common culprit.2 Photoallergic reactions are less common and are a result of a type IV immune reaction to the offending agent.1

Phototoxic reactions generally present shortly after sun or UV exposure with a photo-distributed eruption pattern.3 Commonly involved areas include the face, the neck, and the extensor surfaces of extremities, with sparing of relatively protected skin such as the upper eyelids and the skin folds.2 Erythema may initially develop in the exposed skin areas, followed by appearance of edema, vesicles, or bullae.1-3 The eruption may be painful and itchy, with some patients reporting severe pain.3

Doxycycline phototoxicity may also cause onycholysis of the nails.2 The reaction is dose dependent, with higher doses of medication leading to a higher likelihood of symptoms.1,2 It is also more prevalent in patients with Fitzpatrick skin type I and II. The usual UVA wavelength required to induce this reaction appears to be in the 320-400 nm range of the UV spectrum.4 By contrast, photoallergic reactions are dose independent, and require a sensitization period prior to the eruption.1 An eczematous eruption is most commonly seen with photoallergic reactions.3

Treatment of drug-induced photosensitivity reactions requires proper identification of the diagnosis and the offending agent, followed by cessation of the medication. If cessation is not possible, then lowering the dose can help to minimize worsening of the condition. However, for photoallergic reactions, the reaction is dose independent so switching to another tolerated agent is likely required. For persistent symptoms following medication withdrawal, topical or systemic steroids and oral antihistamine can help with symptom management.1 For patients with photo-onycholysis, treatment involves stopping the medication and waiting for the intact nail plate to grow.

Prevention is key in the management of photosensitivity reactions. Patients should be counseled about the increased risk of photosensitivity while on tetracycline medications and encouraged to engage in enhanced sun protection measures such as wearing sun protective hats and clothing, increasing use of sunscreen that provides mainly UVA but also UVB protection, and avoiding the sun during the midday when the UV index is highest.1-3

Dermatomyositis

Dermatomyositis is an autoimmune condition that presents with skin lesions as well as systemic findings such as myositis. The cutaneous findings are variable, but pathognomonic findings include Gottron papules of the hands, Gottron’s sign on the elbows, knees, and ankles, and the heliotrope rash of the face. Eighty percent of patients have myopathy presenting as muscle weakness, and commonly have elevated creatine kinase, aspartate transaminase, and alanine transaminase values.5 Diagnosis may be confirmed through skin or muscle biopsy, though antibody studies can also play a helpful role in diagnosis. Treatment is generally with oral corticosteroids or other immunosuppressants as well as sun protection.6 The rash seen in our patient could have been seen in patients with dermatomyositis, though it was not in the typical location on the knuckles (Gottron papules) as it also affected the lateral sides of the fingers.

Systemic lupus erythematosus

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is an autoimmune condition characterized by systemic and cutaneous manifestations. Systemic symptoms may include weight loss, fever, fatigue, arthralgia, or arthritis; patients are at risk of renal, cardiovascular, pulmonary, and neurologic complications of SLE.7 The most common cutaneous finding is malar rash, though there are myriad dermatologic manifestations that can occur associated with photosensitivity. Diagnosis is made based on history, physical, and laboratory testing. Treatment options include NSAIDs, oral glucocorticoids, antimalarial drugs, and immunosuppressants.7 Though our patient exhibited photosensitivity, he had none of the systemic findings associated with SLE, making this diagnosis unlikely.

Allergic contact dermatitis

Allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) is a type IV hypersensitivity reaction, and may present as acute, subacute, or chronic dermatitis. The clinical findings vary based on chronicity. Acute ACD presents as pruritic erythematous papules and vesicles or bullae, similar to how it occurred in our patient, though our patient’s lesions were more tender than pruritic. Chronic ACD presents with erythematous lesions with pruritis, lichenification, scaling, and/or fissuring. Observing shapes or sharp demarcation of lesions may help with diagnosis. Patch testing is also useful in the diagnosis of ACD.

Treatment generally involves avoiding the offending agent with topical corticosteroids for symptom management.8

Polymorphous light eruption

Polymorphous light eruption (PLE) is a delayed, type IV hypersensitivity reaction to UV-induced antigens, though these antigens are unknown. PLE presents hours to days following solar or UV exposure and presents only in sun-exposed areas. Itching and burning are always present, but lesion morphology varies from erythema and papules to vesico-papules and blisters. Notably, PLE must be distinguished from drug photosensitivity through history. Treatment generally involves symptom management with topical steroids and sun protective measures for prevention.9 While PLE may present similarly to drug photosensitivity reactions, our patient’s use of a known phototoxic agent makes PLE a less likely diagnosis.

Ms. Appiah is a pediatric dermatology research associate and medical student at the University of California, San Diego, and Rady Children’s Hospital, San Diego. Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego. Neither Dr. Matiz nor Ms. Appiah has any relevant financial disclosures.

References

1. Montgomery S et al. Clin Dermatol. 2022;40(1):57-63.

2. Blakely KM et al. Drug Saf. 2019;42(7):827-47.

3. Goetze S et al. Skin Pharmacol Physiol. 2017;30(2):76-80.

4. Odorici G et al. Dermatol Ther. 2021;34(4):e14978.

5. DeWane ME et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82(2):267-81.

6. Waldman R et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82(2):283-96.

7. Kiriakidou M et al. Ann Intern Med. 2020;172(11):ITC81-ITC96.

8. Nassau S et al. Med Clin North Am. 2020;104(1):61-76.

9. Guarrera M. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2017;996:61-70.

Photosensitivity due to doxycycline

As the patient’s rash presented in sun-exposed areas with both skin and nail changes, our patient was diagnosed with a phototoxic reaction to doxycycline, the oral antibiotic used to treat his acne.

Photosensitive cutaneous drug eruptions are reactions that occur after exposure to a medication and subsequent exposure to UV radiation or visible light. Reactions can be classified into two ways based on their mechanism of action: phototoxic or photoallergic.1 Phototoxic reactions are more common and are a result of direct keratinocyte damage and cellular necrosis. Many classes of medications may cause this adverse effect, but the tetracycline class of antibiotics is a common culprit.2 Photoallergic reactions are less common and are a result of a type IV immune reaction to the offending agent.1

Phototoxic reactions generally present shortly after sun or UV exposure with a photo-distributed eruption pattern.3 Commonly involved areas include the face, the neck, and the extensor surfaces of extremities, with sparing of relatively protected skin such as the upper eyelids and the skin folds.2 Erythema may initially develop in the exposed skin areas, followed by appearance of edema, vesicles, or bullae.1-3 The eruption may be painful and itchy, with some patients reporting severe pain.3

Doxycycline phototoxicity may also cause onycholysis of the nails.2 The reaction is dose dependent, with higher doses of medication leading to a higher likelihood of symptoms.1,2 It is also more prevalent in patients with Fitzpatrick skin type I and II. The usual UVA wavelength required to induce this reaction appears to be in the 320-400 nm range of the UV spectrum.4 By contrast, photoallergic reactions are dose independent, and require a sensitization period prior to the eruption.1 An eczematous eruption is most commonly seen with photoallergic reactions.3

Treatment of drug-induced photosensitivity reactions requires proper identification of the diagnosis and the offending agent, followed by cessation of the medication. If cessation is not possible, then lowering the dose can help to minimize worsening of the condition. However, for photoallergic reactions, the reaction is dose independent so switching to another tolerated agent is likely required. For persistent symptoms following medication withdrawal, topical or systemic steroids and oral antihistamine can help with symptom management.1 For patients with photo-onycholysis, treatment involves stopping the medication and waiting for the intact nail plate to grow.

Prevention is key in the management of photosensitivity reactions. Patients should be counseled about the increased risk of photosensitivity while on tetracycline medications and encouraged to engage in enhanced sun protection measures such as wearing sun protective hats and clothing, increasing use of sunscreen that provides mainly UVA but also UVB protection, and avoiding the sun during the midday when the UV index is highest.1-3

Dermatomyositis

Dermatomyositis is an autoimmune condition that presents with skin lesions as well as systemic findings such as myositis. The cutaneous findings are variable, but pathognomonic findings include Gottron papules of the hands, Gottron’s sign on the elbows, knees, and ankles, and the heliotrope rash of the face. Eighty percent of patients have myopathy presenting as muscle weakness, and commonly have elevated creatine kinase, aspartate transaminase, and alanine transaminase values.5 Diagnosis may be confirmed through skin or muscle biopsy, though antibody studies can also play a helpful role in diagnosis. Treatment is generally with oral corticosteroids or other immunosuppressants as well as sun protection.6 The rash seen in our patient could have been seen in patients with dermatomyositis, though it was not in the typical location on the knuckles (Gottron papules) as it also affected the lateral sides of the fingers.

Systemic lupus erythematosus

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is an autoimmune condition characterized by systemic and cutaneous manifestations. Systemic symptoms may include weight loss, fever, fatigue, arthralgia, or arthritis; patients are at risk of renal, cardiovascular, pulmonary, and neurologic complications of SLE.7 The most common cutaneous finding is malar rash, though there are myriad dermatologic manifestations that can occur associated with photosensitivity. Diagnosis is made based on history, physical, and laboratory testing. Treatment options include NSAIDs, oral glucocorticoids, antimalarial drugs, and immunosuppressants.7 Though our patient exhibited photosensitivity, he had none of the systemic findings associated with SLE, making this diagnosis unlikely.

Allergic contact dermatitis

Allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) is a type IV hypersensitivity reaction, and may present as acute, subacute, or chronic dermatitis. The clinical findings vary based on chronicity. Acute ACD presents as pruritic erythematous papules and vesicles or bullae, similar to how it occurred in our patient, though our patient’s lesions were more tender than pruritic. Chronic ACD presents with erythematous lesions with pruritis, lichenification, scaling, and/or fissuring. Observing shapes or sharp demarcation of lesions may help with diagnosis. Patch testing is also useful in the diagnosis of ACD.

Treatment generally involves avoiding the offending agent with topical corticosteroids for symptom management.8

Polymorphous light eruption

Polymorphous light eruption (PLE) is a delayed, type IV hypersensitivity reaction to UV-induced antigens, though these antigens are unknown. PLE presents hours to days following solar or UV exposure and presents only in sun-exposed areas. Itching and burning are always present, but lesion morphology varies from erythema and papules to vesico-papules and blisters. Notably, PLE must be distinguished from drug photosensitivity through history. Treatment generally involves symptom management with topical steroids and sun protective measures for prevention.9 While PLE may present similarly to drug photosensitivity reactions, our patient’s use of a known phototoxic agent makes PLE a less likely diagnosis.

Ms. Appiah is a pediatric dermatology research associate and medical student at the University of California, San Diego, and Rady Children’s Hospital, San Diego. Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego. Neither Dr. Matiz nor Ms. Appiah has any relevant financial disclosures.

References

1. Montgomery S et al. Clin Dermatol. 2022;40(1):57-63.

2. Blakely KM et al. Drug Saf. 2019;42(7):827-47.

3. Goetze S et al. Skin Pharmacol Physiol. 2017;30(2):76-80.

4. Odorici G et al. Dermatol Ther. 2021;34(4):e14978.

5. DeWane ME et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82(2):267-81.

6. Waldman R et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82(2):283-96.

7. Kiriakidou M et al. Ann Intern Med. 2020;172(11):ITC81-ITC96.

8. Nassau S et al. Med Clin North Am. 2020;104(1):61-76.

9. Guarrera M. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2017;996:61-70.

Photosensitivity due to doxycycline

As the patient’s rash presented in sun-exposed areas with both skin and nail changes, our patient was diagnosed with a phototoxic reaction to doxycycline, the oral antibiotic used to treat his acne.

Photosensitive cutaneous drug eruptions are reactions that occur after exposure to a medication and subsequent exposure to UV radiation or visible light. Reactions can be classified into two ways based on their mechanism of action: phototoxic or photoallergic.1 Phototoxic reactions are more common and are a result of direct keratinocyte damage and cellular necrosis. Many classes of medications may cause this adverse effect, but the tetracycline class of antibiotics is a common culprit.2 Photoallergic reactions are less common and are a result of a type IV immune reaction to the offending agent.1

Phototoxic reactions generally present shortly after sun or UV exposure with a photo-distributed eruption pattern.3 Commonly involved areas include the face, the neck, and the extensor surfaces of extremities, with sparing of relatively protected skin such as the upper eyelids and the skin folds.2 Erythema may initially develop in the exposed skin areas, followed by appearance of edema, vesicles, or bullae.1-3 The eruption may be painful and itchy, with some patients reporting severe pain.3

Doxycycline phototoxicity may also cause onycholysis of the nails.2 The reaction is dose dependent, with higher doses of medication leading to a higher likelihood of symptoms.1,2 It is also more prevalent in patients with Fitzpatrick skin type I and II. The usual UVA wavelength required to induce this reaction appears to be in the 320-400 nm range of the UV spectrum.4 By contrast, photoallergic reactions are dose independent, and require a sensitization period prior to the eruption.1 An eczematous eruption is most commonly seen with photoallergic reactions.3

Treatment of drug-induced photosensitivity reactions requires proper identification of the diagnosis and the offending agent, followed by cessation of the medication. If cessation is not possible, then lowering the dose can help to minimize worsening of the condition. However, for photoallergic reactions, the reaction is dose independent so switching to another tolerated agent is likely required. For persistent symptoms following medication withdrawal, topical or systemic steroids and oral antihistamine can help with symptom management.1 For patients with photo-onycholysis, treatment involves stopping the medication and waiting for the intact nail plate to grow.

Prevention is key in the management of photosensitivity reactions. Patients should be counseled about the increased risk of photosensitivity while on tetracycline medications and encouraged to engage in enhanced sun protection measures such as wearing sun protective hats and clothing, increasing use of sunscreen that provides mainly UVA but also UVB protection, and avoiding the sun during the midday when the UV index is highest.1-3

Dermatomyositis

Dermatomyositis is an autoimmune condition that presents with skin lesions as well as systemic findings such as myositis. The cutaneous findings are variable, but pathognomonic findings include Gottron papules of the hands, Gottron’s sign on the elbows, knees, and ankles, and the heliotrope rash of the face. Eighty percent of patients have myopathy presenting as muscle weakness, and commonly have elevated creatine kinase, aspartate transaminase, and alanine transaminase values.5 Diagnosis may be confirmed through skin or muscle biopsy, though antibody studies can also play a helpful role in diagnosis. Treatment is generally with oral corticosteroids or other immunosuppressants as well as sun protection.6 The rash seen in our patient could have been seen in patients with dermatomyositis, though it was not in the typical location on the knuckles (Gottron papules) as it also affected the lateral sides of the fingers.

Systemic lupus erythematosus

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is an autoimmune condition characterized by systemic and cutaneous manifestations. Systemic symptoms may include weight loss, fever, fatigue, arthralgia, or arthritis; patients are at risk of renal, cardiovascular, pulmonary, and neurologic complications of SLE.7 The most common cutaneous finding is malar rash, though there are myriad dermatologic manifestations that can occur associated with photosensitivity. Diagnosis is made based on history, physical, and laboratory testing. Treatment options include NSAIDs, oral glucocorticoids, antimalarial drugs, and immunosuppressants.7 Though our patient exhibited photosensitivity, he had none of the systemic findings associated with SLE, making this diagnosis unlikely.

Allergic contact dermatitis

Allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) is a type IV hypersensitivity reaction, and may present as acute, subacute, or chronic dermatitis. The clinical findings vary based on chronicity. Acute ACD presents as pruritic erythematous papules and vesicles or bullae, similar to how it occurred in our patient, though our patient’s lesions were more tender than pruritic. Chronic ACD presents with erythematous lesions with pruritis, lichenification, scaling, and/or fissuring. Observing shapes or sharp demarcation of lesions may help with diagnosis. Patch testing is also useful in the diagnosis of ACD.

Treatment generally involves avoiding the offending agent with topical corticosteroids for symptom management.8

Polymorphous light eruption

Polymorphous light eruption (PLE) is a delayed, type IV hypersensitivity reaction to UV-induced antigens, though these antigens are unknown. PLE presents hours to days following solar or UV exposure and presents only in sun-exposed areas. Itching and burning are always present, but lesion morphology varies from erythema and papules to vesico-papules and blisters. Notably, PLE must be distinguished from drug photosensitivity through history. Treatment generally involves symptom management with topical steroids and sun protective measures for prevention.9 While PLE may present similarly to drug photosensitivity reactions, our patient’s use of a known phototoxic agent makes PLE a less likely diagnosis.

Ms. Appiah is a pediatric dermatology research associate and medical student at the University of California, San Diego, and Rady Children’s Hospital, San Diego. Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego. Neither Dr. Matiz nor Ms. Appiah has any relevant financial disclosures.

References

1. Montgomery S et al. Clin Dermatol. 2022;40(1):57-63.

2. Blakely KM et al. Drug Saf. 2019;42(7):827-47.

3. Goetze S et al. Skin Pharmacol Physiol. 2017;30(2):76-80.

4. Odorici G et al. Dermatol Ther. 2021;34(4):e14978.

5. DeWane ME et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82(2):267-81.

6. Waldman R et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82(2):283-96.

7. Kiriakidou M et al. Ann Intern Med. 2020;172(11):ITC81-ITC96.

8. Nassau S et al. Med Clin North Am. 2020;104(1):61-76.

9. Guarrera M. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2017;996:61-70.

He reported no hiking or gardening, no new topical products such as new sunscreens or lotions, and no new medications. The patient had a history of acne, for which he used over-the-counter benzoyl peroxide wash, adapalene gel, and an oral antibiotic for 3 months. His review of systems was negative for fevers, chills, muscle weakness, mouth sores, or joint pain and no prior rashes following sun exposure.

On physical exam he presented with pink plaques with thin vesicles on the dorsum of the hands that were more noticeable on the lateral aspect of both the first and second fingers (Figures 1 and 2). His nails also had a yellow discoloration.

A 19-month-old vaccinated female with 2 days of rash

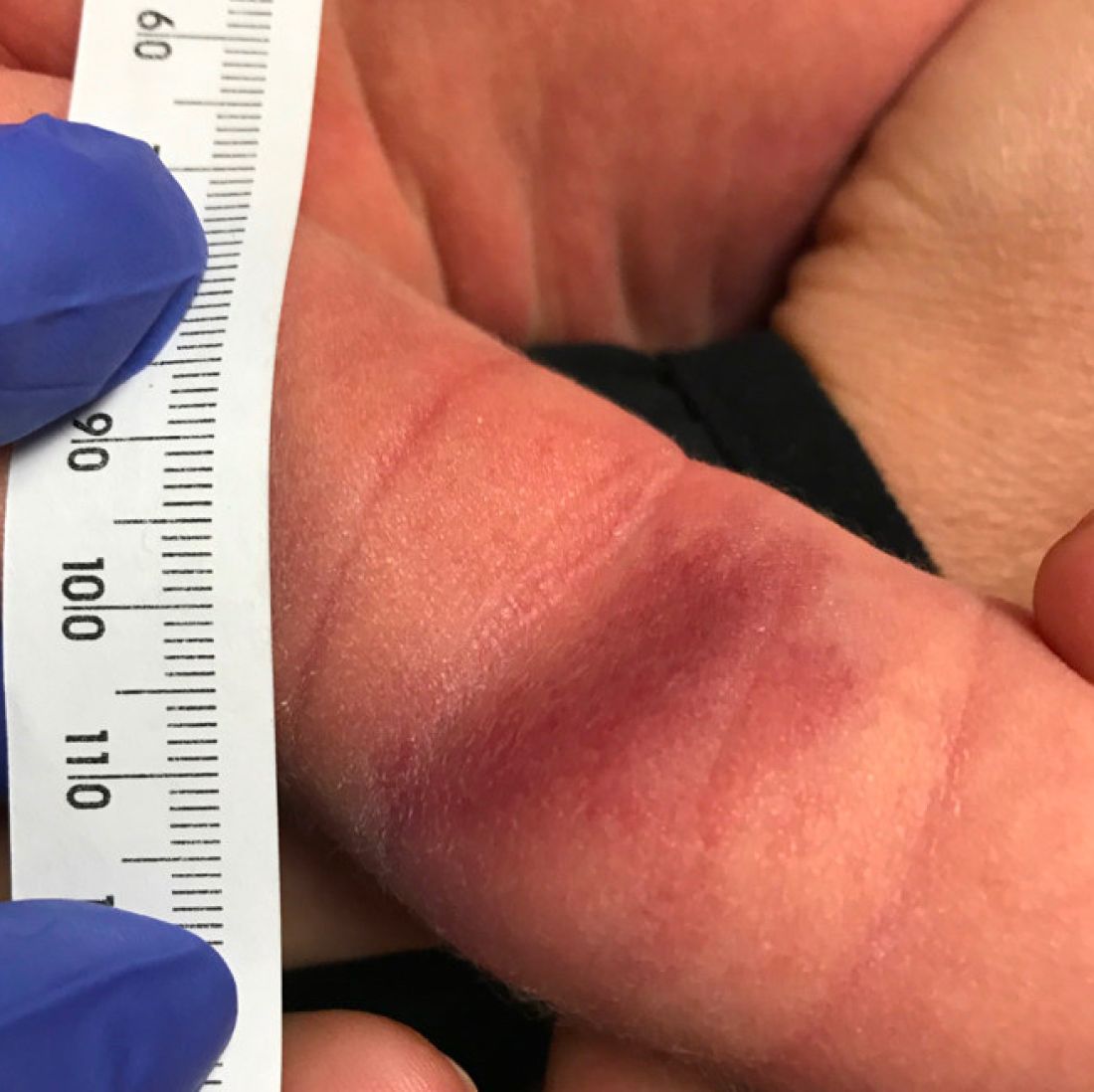

Acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy (AHEI) is a leukocytoclastic vasculitis that typically affects children between 4 months and 2 years of age.1 Etiology is unknown but the majority of cases are preceded by infections, vaccinations, or certain medications.2

AHEI is a self-limited disease that runs a benign course with spontaneous resolution within days to 3 weeks.3 Classic presentation involves acute onset of fever, purpura, ecchymosis, and inflammatory edema. Edema is often the first sign, and may involve the face, ears, scrotum, or extremities. Hemorrhagic lesions may vary in size but often coalesce and present in a distinctive “cockade” or rosette pattern with scalloped borders. Systemic manifestations are rare, but renal and joint involvement may occur.4 Despite the dramatic and sometimes extensive appearance of the dermatologic manifestations, patients with AHEI are usually not in significant distress.

Diagnosis is clinical, but skin biopsy may show leukocytoclastic vasculitis of the superficial small vessels with infiltrations of neutrophils, extravasation of red blood cells, and fibrinoid necrosis.5 In most cases, immunofluorescence is negative for perivascular IgA deposition. Treatment is symptomatic as the disease resolves spontaneously. Recurrence is uncommon but may occur, and usually occurs early.

What is on the differential?

Kawasaki disease. Similar to AHEI, patients with Kawasaki disease also may present with facial and extremity edema. However, patients with Kawasaki disease appear sicker, have associated lymphadenopathy, conjunctivitis, and fever longer than 5 days. The lack of elevated inflammatory markers, acute-onset, classic dermatologic lesions, and nontoxic appearance in our patient rule out Kawasaki disease and make AHEI more likely.

IgA vasculitis/Henoch-Schönlein purpura. The distinction between AHEI and Henoch-Schönlein purpura is among the most challenging. AHEI commonly afflicts younger children ranging from 4 months to 2 years, whereas Henoch-Schönlein purpura occurs in older children from 3 to 6 years of age. Visceral involvement is rare in AHEI, but frequently presents in Henoch-Schönlein purpura with gastrointestinal and renal complications. Although our patient had both mild renal involvement and a distribution primarily on the buttocks and lower limbs, similar to the classic distribution of Henoch-Schönlein purpura, the younger age and lack of gastrointestinal and arthritic manifestations make AHEI more likely.

Gianotti-Crosti syndrome. Gianotti-Crosti syndrome, also known as papulovesicular acrodermatitis of childhood, mainly affects children between the ages of 6 months and 12 years. Like AHEI, Gianotti-Crosti is a self-limiting condition likely triggered by viral infection or immunization. However, Gianotti-Crosti is characterized by a papular rash that may last for several weeks. Neither AHEI nor Gianotti-Crosti are pruritic, but patients with Gianotti-Crosti tend to have either inguinal or axillary lymphadenopathy. Our patient’s large, coalescing dusky red patches and edematous plaques without lymphadenopathy are more consistent with AHEI.

Erythema multiforme. Erythema multiforme is an acute, immune-mediated condition characterized by distinctive target-like lesions on the skin often accompanied by erosions or bullae. Unlike AHEI, erythema multiforme can involve the oral, genital, and/or ocular mucosae. Erythema multiforme is rare before the age of 4 years. Although the targetoid or annular purpuric configuration of erythema multiforme may present similarly to AHEI in some cases, the young age of our patient and the lack of mucosal involvement make AHEI more likely.

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego. Ms. Kleinman is a pediatric dermatology research associate at the University of California, San Diego, and Rady Children’s Hospital, San Diego. Neither Dr. Matiz nor Ms. Kleinman has any relevant financial disclosures.

References

1. Savino F et al. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30(6):e149-e152.

2. Carboni E et al. F1000Res. 2019;8:1771. 2019 Oct 17.

3. Fiore E et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59(4):684-95.

4. Watanabe T and Sato Y. Pediatr Nephrol. 2007;22(11):1979-81.

5. Cunha DF et al. Autops Case Rep. 2015;5(3):37-41.

Acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy (AHEI) is a leukocytoclastic vasculitis that typically affects children between 4 months and 2 years of age.1 Etiology is unknown but the majority of cases are preceded by infections, vaccinations, or certain medications.2

AHEI is a self-limited disease that runs a benign course with spontaneous resolution within days to 3 weeks.3 Classic presentation involves acute onset of fever, purpura, ecchymosis, and inflammatory edema. Edema is often the first sign, and may involve the face, ears, scrotum, or extremities. Hemorrhagic lesions may vary in size but often coalesce and present in a distinctive “cockade” or rosette pattern with scalloped borders. Systemic manifestations are rare, but renal and joint involvement may occur.4 Despite the dramatic and sometimes extensive appearance of the dermatologic manifestations, patients with AHEI are usually not in significant distress.

Diagnosis is clinical, but skin biopsy may show leukocytoclastic vasculitis of the superficial small vessels with infiltrations of neutrophils, extravasation of red blood cells, and fibrinoid necrosis.5 In most cases, immunofluorescence is negative for perivascular IgA deposition. Treatment is symptomatic as the disease resolves spontaneously. Recurrence is uncommon but may occur, and usually occurs early.

What is on the differential?

Kawasaki disease. Similar to AHEI, patients with Kawasaki disease also may present with facial and extremity edema. However, patients with Kawasaki disease appear sicker, have associated lymphadenopathy, conjunctivitis, and fever longer than 5 days. The lack of elevated inflammatory markers, acute-onset, classic dermatologic lesions, and nontoxic appearance in our patient rule out Kawasaki disease and make AHEI more likely.

IgA vasculitis/Henoch-Schönlein purpura. The distinction between AHEI and Henoch-Schönlein purpura is among the most challenging. AHEI commonly afflicts younger children ranging from 4 months to 2 years, whereas Henoch-Schönlein purpura occurs in older children from 3 to 6 years of age. Visceral involvement is rare in AHEI, but frequently presents in Henoch-Schönlein purpura with gastrointestinal and renal complications. Although our patient had both mild renal involvement and a distribution primarily on the buttocks and lower limbs, similar to the classic distribution of Henoch-Schönlein purpura, the younger age and lack of gastrointestinal and arthritic manifestations make AHEI more likely.

Gianotti-Crosti syndrome. Gianotti-Crosti syndrome, also known as papulovesicular acrodermatitis of childhood, mainly affects children between the ages of 6 months and 12 years. Like AHEI, Gianotti-Crosti is a self-limiting condition likely triggered by viral infection or immunization. However, Gianotti-Crosti is characterized by a papular rash that may last for several weeks. Neither AHEI nor Gianotti-Crosti are pruritic, but patients with Gianotti-Crosti tend to have either inguinal or axillary lymphadenopathy. Our patient’s large, coalescing dusky red patches and edematous plaques without lymphadenopathy are more consistent with AHEI.

Erythema multiforme. Erythema multiforme is an acute, immune-mediated condition characterized by distinctive target-like lesions on the skin often accompanied by erosions or bullae. Unlike AHEI, erythema multiforme can involve the oral, genital, and/or ocular mucosae. Erythema multiforme is rare before the age of 4 years. Although the targetoid or annular purpuric configuration of erythema multiforme may present similarly to AHEI in some cases, the young age of our patient and the lack of mucosal involvement make AHEI more likely.

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego. Ms. Kleinman is a pediatric dermatology research associate at the University of California, San Diego, and Rady Children’s Hospital, San Diego. Neither Dr. Matiz nor Ms. Kleinman has any relevant financial disclosures.

References

1. Savino F et al. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30(6):e149-e152.

2. Carboni E et al. F1000Res. 2019;8:1771. 2019 Oct 17.

3. Fiore E et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59(4):684-95.

4. Watanabe T and Sato Y. Pediatr Nephrol. 2007;22(11):1979-81.

5. Cunha DF et al. Autops Case Rep. 2015;5(3):37-41.

Acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy (AHEI) is a leukocytoclastic vasculitis that typically affects children between 4 months and 2 years of age.1 Etiology is unknown but the majority of cases are preceded by infections, vaccinations, or certain medications.2

AHEI is a self-limited disease that runs a benign course with spontaneous resolution within days to 3 weeks.3 Classic presentation involves acute onset of fever, purpura, ecchymosis, and inflammatory edema. Edema is often the first sign, and may involve the face, ears, scrotum, or extremities. Hemorrhagic lesions may vary in size but often coalesce and present in a distinctive “cockade” or rosette pattern with scalloped borders. Systemic manifestations are rare, but renal and joint involvement may occur.4 Despite the dramatic and sometimes extensive appearance of the dermatologic manifestations, patients with AHEI are usually not in significant distress.

Diagnosis is clinical, but skin biopsy may show leukocytoclastic vasculitis of the superficial small vessels with infiltrations of neutrophils, extravasation of red blood cells, and fibrinoid necrosis.5 In most cases, immunofluorescence is negative for perivascular IgA deposition. Treatment is symptomatic as the disease resolves spontaneously. Recurrence is uncommon but may occur, and usually occurs early.

What is on the differential?

Kawasaki disease. Similar to AHEI, patients with Kawasaki disease also may present with facial and extremity edema. However, patients with Kawasaki disease appear sicker, have associated lymphadenopathy, conjunctivitis, and fever longer than 5 days. The lack of elevated inflammatory markers, acute-onset, classic dermatologic lesions, and nontoxic appearance in our patient rule out Kawasaki disease and make AHEI more likely.

IgA vasculitis/Henoch-Schönlein purpura. The distinction between AHEI and Henoch-Schönlein purpura is among the most challenging. AHEI commonly afflicts younger children ranging from 4 months to 2 years, whereas Henoch-Schönlein purpura occurs in older children from 3 to 6 years of age. Visceral involvement is rare in AHEI, but frequently presents in Henoch-Schönlein purpura with gastrointestinal and renal complications. Although our patient had both mild renal involvement and a distribution primarily on the buttocks and lower limbs, similar to the classic distribution of Henoch-Schönlein purpura, the younger age and lack of gastrointestinal and arthritic manifestations make AHEI more likely.

Gianotti-Crosti syndrome. Gianotti-Crosti syndrome, also known as papulovesicular acrodermatitis of childhood, mainly affects children between the ages of 6 months and 12 years. Like AHEI, Gianotti-Crosti is a self-limiting condition likely triggered by viral infection or immunization. However, Gianotti-Crosti is characterized by a papular rash that may last for several weeks. Neither AHEI nor Gianotti-Crosti are pruritic, but patients with Gianotti-Crosti tend to have either inguinal or axillary lymphadenopathy. Our patient’s large, coalescing dusky red patches and edematous plaques without lymphadenopathy are more consistent with AHEI.

Erythema multiforme. Erythema multiforme is an acute, immune-mediated condition characterized by distinctive target-like lesions on the skin often accompanied by erosions or bullae. Unlike AHEI, erythema multiforme can involve the oral, genital, and/or ocular mucosae. Erythema multiforme is rare before the age of 4 years. Although the targetoid or annular purpuric configuration of erythema multiforme may present similarly to AHEI in some cases, the young age of our patient and the lack of mucosal involvement make AHEI more likely.

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego. Ms. Kleinman is a pediatric dermatology research associate at the University of California, San Diego, and Rady Children’s Hospital, San Diego. Neither Dr. Matiz nor Ms. Kleinman has any relevant financial disclosures.

References

1. Savino F et al. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30(6):e149-e152.

2. Carboni E et al. F1000Res. 2019;8:1771. 2019 Oct 17.

3. Fiore E et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59(4):684-95.

4. Watanabe T and Sato Y. Pediatr Nephrol. 2007;22(11):1979-81.

5. Cunha DF et al. Autops Case Rep. 2015;5(3):37-41.

What is the diagnosis?

As the lesion was growing, getting more violaceous and indurated, a biopsy was performed. The biopsy showed multiple discrete lobules of dermal capillaries with slight extension into the superficial subcutis. Capillary lobules demonstrate the “cannonball-like” architecture often associated with tufted angioma, and some lobules showed bulging into adjacent thin-walled vessels. Spindled endothelial cells lining slit-like vessels were present in the mid dermis, although this comprises a minority of the lesion. The majority of the subcutis was uninvolved. The findings are overall most consistent with a tufted angioma.

Kaposiform hemangioendothelioma (KHE) has been considered given the presence of occasional slit-like vascular spaces; however, the lesion is predominantly superficial and therefore the lesion is best classified as tufted angioma. GLUT–1 staining was negative.

At the time of biopsy, blood work was ordered, which showed a normal complete blood count with normal number of platelets, slightly elevated D-dimer, and slightly low fibrinogen. Several repeat blood counts and coagulation tests once a week for a few weeks revealed no changes.

The patient was started on aspirin at a dose of 5 mg/kg per day. After a week on the medication the lesion was starting to get smaller and less red.