User login

Fungated Eroded Plaque on the Arm

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Blastomycosis

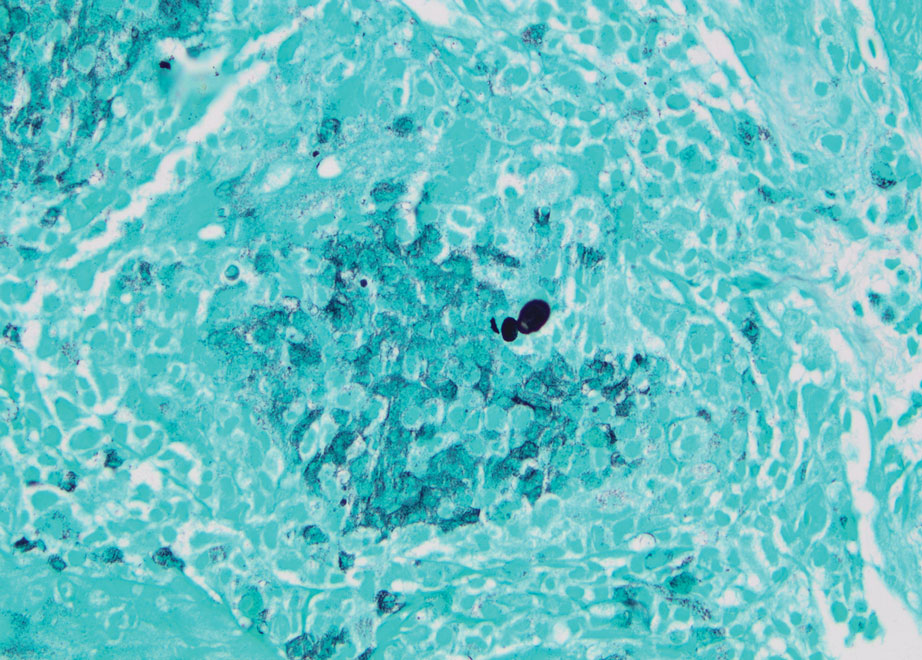

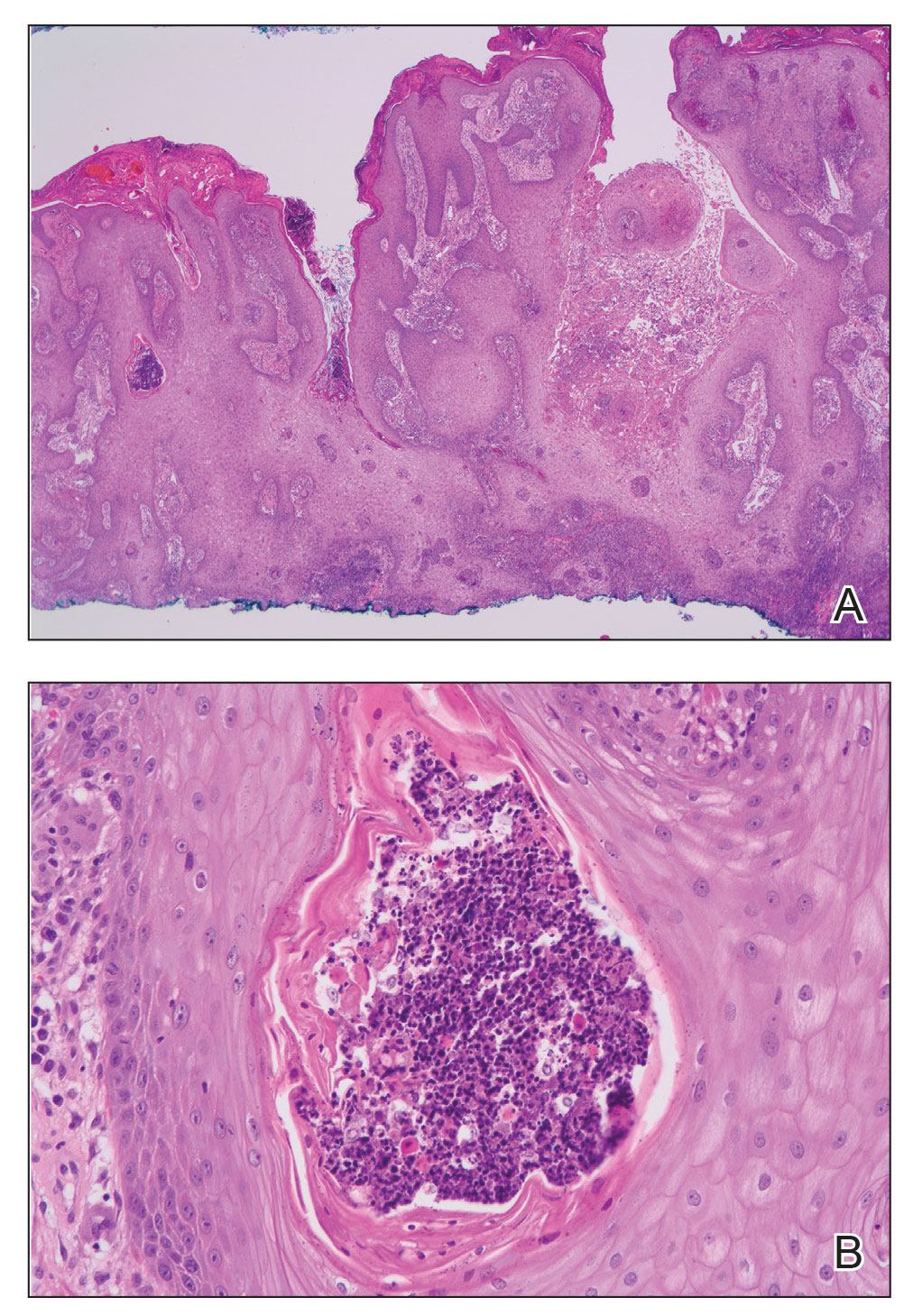

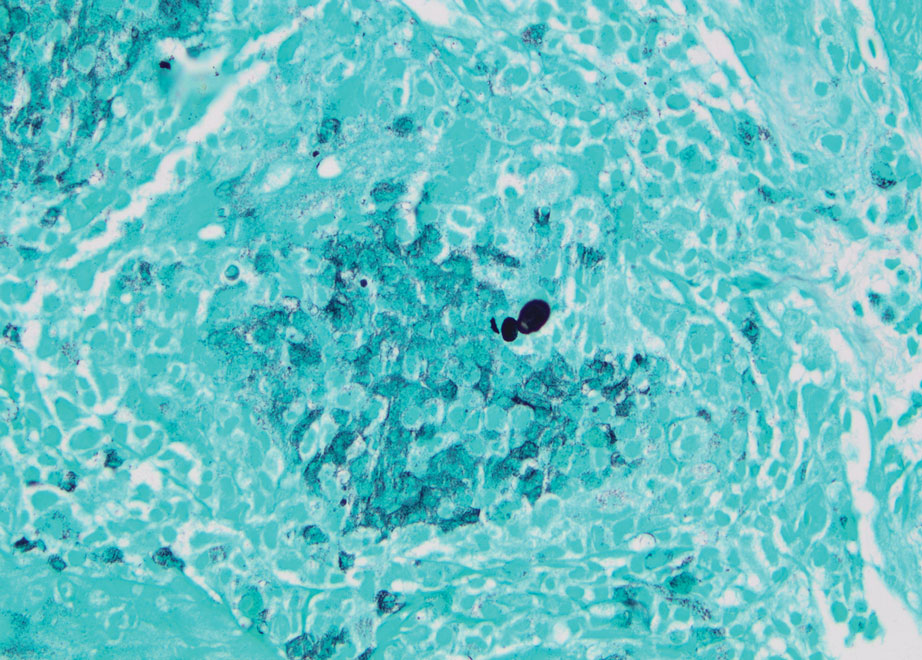

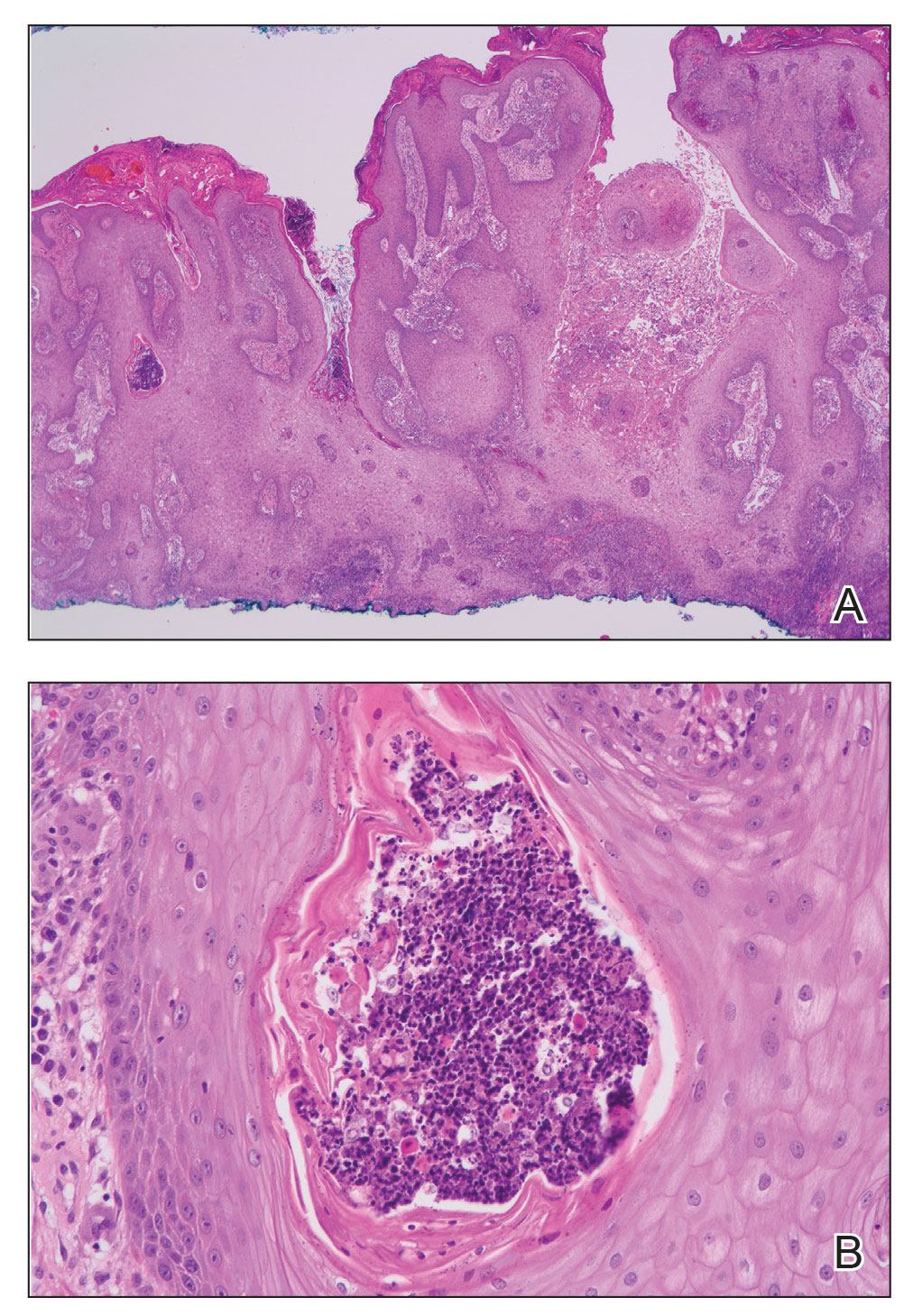

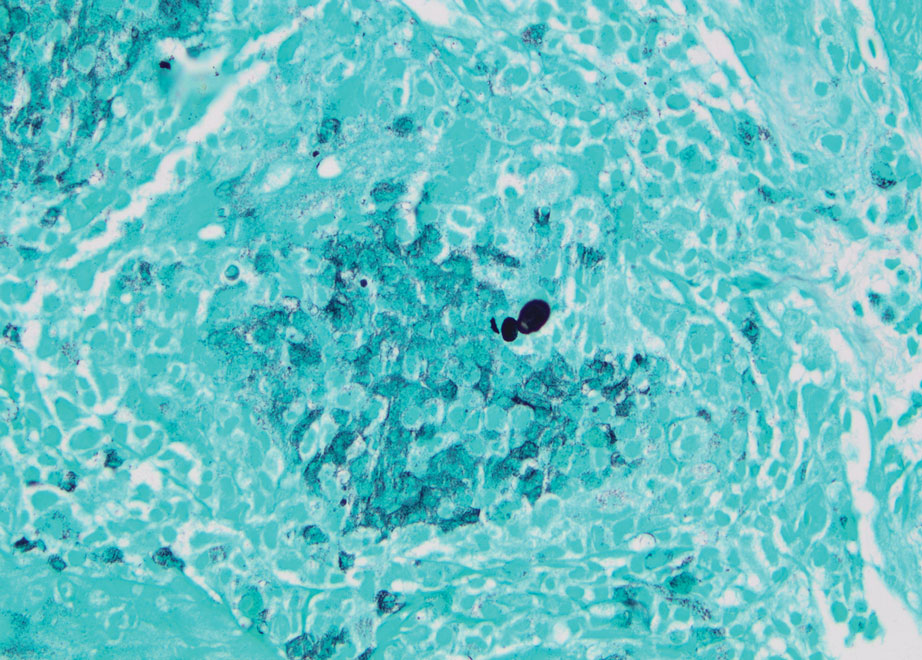

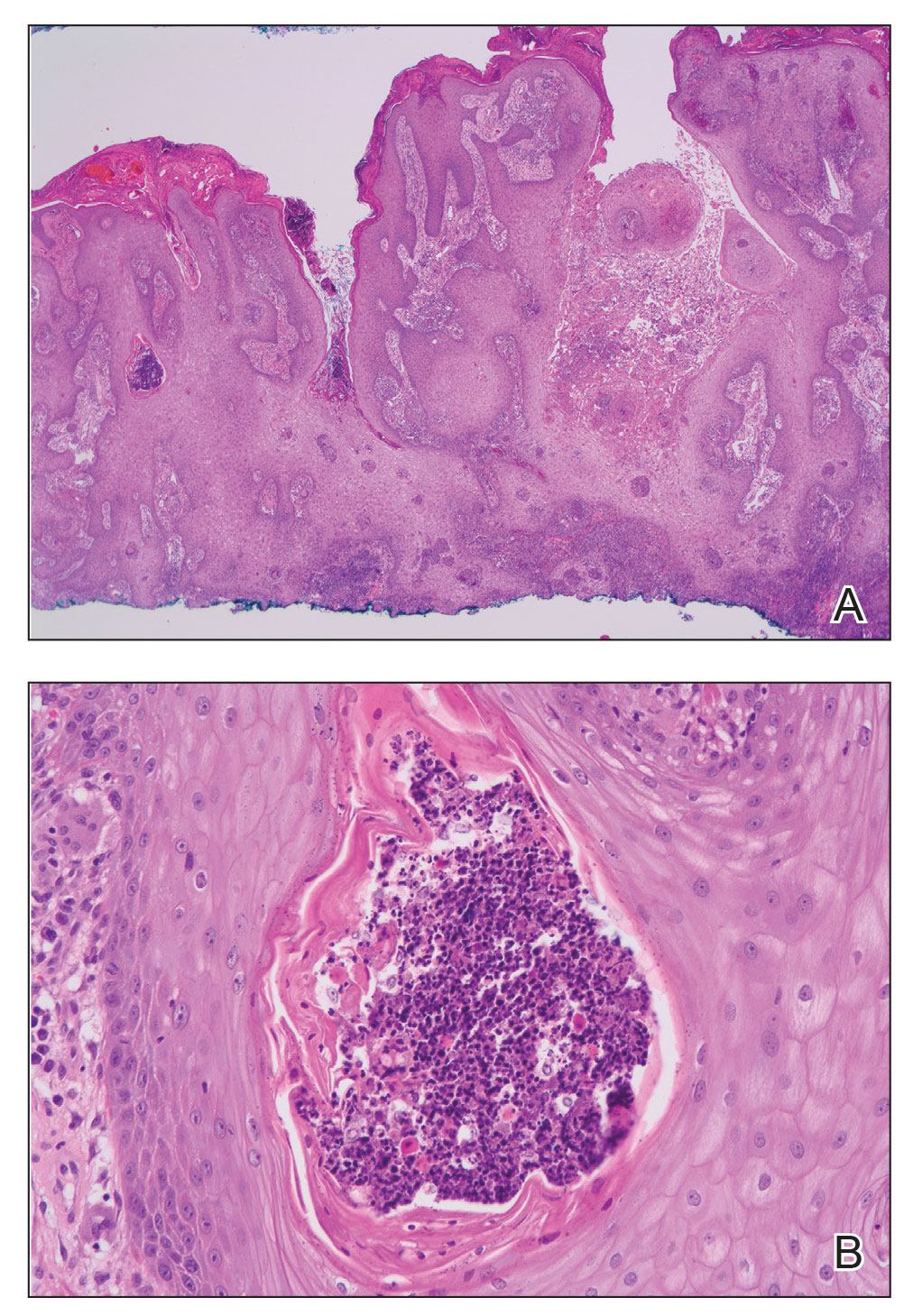

A skin biopsy and fungal cultures confirmed the diagnosis of cutaneous blastomycosis. Grocott- Gomori methenamine-silver staining highlighted fungal organisms with refractile walls and broad-based budding consistent with cutaneous blastomycosis (Figure 1). The histopathologic specimen also demonstrated marked pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia (Figure 2A) with neutrophilic microabscesses (Figure 2B). Acid-fast bacillus and Fite staining were negative for bacterial organisms. A fungal culture was positive for Blastomyces dermatitidis. Urine and serum blastomycosis antigen were positive. Although Histoplasma serum antigen also was positive, this likely was from cross-reactivity. Chest radiography was negative for lung involvement, and the patient displayed no neurologic symptoms. He was started on oral itraconazole therapy for the treatment of cutaneous blastomycosis.

Blastomyces dermatitidis, the causative organism of blastomycosis, is endemic to the Ohio and Mississippi River valleys, Great Lakes region, and southeastern United States. It is a thermally dimorphic fungus found in soils that grows as a mold at 25 °C and yeast at 37 °C. Primary infection of the lungs—blastomycosis pneumonia—often is the only clinical manifestation1; however, subsequent hematogenous dissemination to extrapulmonary sites such as the skin, bones, and genitourinary system can occur. Cutaneous blastomycosis, the most common extrapulmonary manifestation, typically follows pulmonary infection. In rare cases, it can occur from direct inoculation.2,3 Skin lesions can occur anywhere but frequently are found on exposed surfaces of the head, neck, and extremities. Lesions classically present as verrucous crusting plaques with draining microabscesses. Violaceous nodules, ulcers, and pustules also may occur.1

Diagnosis involves obtaining a thorough history of possible environmental exposures such as the patient’s geographic area of residence, occupation, and outdoor activities involving soil or decaying wood. Because blastomycosis can remain latent, remote exposures are relevant. Definitive diagnosis of cutaneous blastomycosis involves skin biopsy of the lesion with fungal culture, but the yeast’s distinctive thick wall and broad-based budding seen with periodic acid–Schiff or Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver staining provides a rapid presumptive diagnosis.3 Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia and microabscesses also are characteristic features.2 Urine antigen testing for a component of the polysaccharide cell wall has a sensitivity of 93% but a lower specificity of 79% due to cross-reactivity with histoplasmosis.4 Treatment consists of itraconazole for mild to moderate blastomycosis or amphotericin B for those with severe disease or central nervous system involvement or those who are immunosuppressed.1

The differential diagnosis for our patient’s lesion included infectious vs neoplastic etiologies. Histoplasma capsulatum, the dimorphic fungus that causes histoplasmosis, also is endemic to the Ohio and Mississippi River valleys. It is found in soil and droppings of some bats and birds such as chickens and pigeons. Similar to blastomycosis, the primary infection site most commonly is the lungs. It subsequently may disseminate to the skin or less commonly via direct inoculation of injured skin. It can present as papules, plaques, ulcers, purpura, or abscesses. Unlike blastomycosis, tissue biopsy of a cutaneous lesion reveals granuloma formation and distinctive oval, narrow-based budding yeast.5 Atypical mycobacteria are another source of infection to consider. For example, cutaneous Mycobacterium kansasii may present as papules and pustules forming verrucous or granulomatous plaques and ulceration. Histopathologic findings distinguishing mycobacterial infection from blastomycosis include granulomas and acid-fast bacilli in histiocytes.6

Noninfectious etiologies in the differential may include cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma or pemphigus vegetans. Squamous cell carcinoma may present with a broad range of clinical features—papules, plaques, or nodules with smooth, scaly, verrucous, or ulcerative secondary features all are possible presentations.7 Fairskinned individuals, such as our patient, would be at a higher risk in sun-damaged skin. Histologically, cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma is defined as an invasion of the dermis by neoplastic squamous epithelial cells in the form of cords, sheets, individual cells, nodules, or cystic structures.7 Pemphigus vegetans is the rarest variant of a group of autoimmune vesiculobullous diseases known as pemphigus. It can be differentiated from the most common variant—pemphigus vulgaris—by the presence of vegetative plaques in intertriginous areas. However, these verrucous vegetations can be misleading and make clinical diagnosis difficult. Histopathologic findings of hyperkeratosis, pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, papillomatosis, and acantholysis with a suprabasal cleft would confirm the diagnosis.8

In summary, cutaneous blastomycosis classically presents as verrucous crusting plaques, as seen in our patient. It is important to conduct a thorough history for environmental exposures, but definitive diagnosis of cutaneous blastomycosis involves skin biopsy with fungal culture. Treatment depends on the severity of disease and organ involvement. Itraconazole would be appropriate for mild to moderate blastomycosis.

- Miceli A, Krishnamurthy K. Blastomycosis. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. Accessed June 21, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441987/

- Gray NA, Baddour LM. Cutaneous inoculation blastomycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:E44-E49.

- Schwartz IS, Kauffman CA. Blastomycosis. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;41:31-41. doi:10.1055/s-0039-3400281

- Castillo CG, Kauffman CA, Miceli MH. Blastomycosis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2016;30:247-264. doi:10.1016/j.idc.2015.10.002

- Raggio B. Primary cutaneous histoplasmosis. Ear Nose Throat J. 2018;97:346-348.

- Bhambri S, Bhambri A, Del Rosso JQ. Atypical mycobacterial cutaneous infections. Dermatol Clin. 2009;27:63-73. doi:10.1016/j.det.2008.07.009

- Parekh V, Seykora JT. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Clin Lab Med. 2017;37:503-525. doi:10.1016/j.cll.2017.06.003

- Messersmith L, Krauland K. Pemphigus vegetans. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. Accessed June 21, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK545229/

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Blastomycosis

A skin biopsy and fungal cultures confirmed the diagnosis of cutaneous blastomycosis. Grocott- Gomori methenamine-silver staining highlighted fungal organisms with refractile walls and broad-based budding consistent with cutaneous blastomycosis (Figure 1). The histopathologic specimen also demonstrated marked pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia (Figure 2A) with neutrophilic microabscesses (Figure 2B). Acid-fast bacillus and Fite staining were negative for bacterial organisms. A fungal culture was positive for Blastomyces dermatitidis. Urine and serum blastomycosis antigen were positive. Although Histoplasma serum antigen also was positive, this likely was from cross-reactivity. Chest radiography was negative for lung involvement, and the patient displayed no neurologic symptoms. He was started on oral itraconazole therapy for the treatment of cutaneous blastomycosis.

Blastomyces dermatitidis, the causative organism of blastomycosis, is endemic to the Ohio and Mississippi River valleys, Great Lakes region, and southeastern United States. It is a thermally dimorphic fungus found in soils that grows as a mold at 25 °C and yeast at 37 °C. Primary infection of the lungs—blastomycosis pneumonia—often is the only clinical manifestation1; however, subsequent hematogenous dissemination to extrapulmonary sites such as the skin, bones, and genitourinary system can occur. Cutaneous blastomycosis, the most common extrapulmonary manifestation, typically follows pulmonary infection. In rare cases, it can occur from direct inoculation.2,3 Skin lesions can occur anywhere but frequently are found on exposed surfaces of the head, neck, and extremities. Lesions classically present as verrucous crusting plaques with draining microabscesses. Violaceous nodules, ulcers, and pustules also may occur.1

Diagnosis involves obtaining a thorough history of possible environmental exposures such as the patient’s geographic area of residence, occupation, and outdoor activities involving soil or decaying wood. Because blastomycosis can remain latent, remote exposures are relevant. Definitive diagnosis of cutaneous blastomycosis involves skin biopsy of the lesion with fungal culture, but the yeast’s distinctive thick wall and broad-based budding seen with periodic acid–Schiff or Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver staining provides a rapid presumptive diagnosis.3 Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia and microabscesses also are characteristic features.2 Urine antigen testing for a component of the polysaccharide cell wall has a sensitivity of 93% but a lower specificity of 79% due to cross-reactivity with histoplasmosis.4 Treatment consists of itraconazole for mild to moderate blastomycosis or amphotericin B for those with severe disease or central nervous system involvement or those who are immunosuppressed.1

The differential diagnosis for our patient’s lesion included infectious vs neoplastic etiologies. Histoplasma capsulatum, the dimorphic fungus that causes histoplasmosis, also is endemic to the Ohio and Mississippi River valleys. It is found in soil and droppings of some bats and birds such as chickens and pigeons. Similar to blastomycosis, the primary infection site most commonly is the lungs. It subsequently may disseminate to the skin or less commonly via direct inoculation of injured skin. It can present as papules, plaques, ulcers, purpura, or abscesses. Unlike blastomycosis, tissue biopsy of a cutaneous lesion reveals granuloma formation and distinctive oval, narrow-based budding yeast.5 Atypical mycobacteria are another source of infection to consider. For example, cutaneous Mycobacterium kansasii may present as papules and pustules forming verrucous or granulomatous plaques and ulceration. Histopathologic findings distinguishing mycobacterial infection from blastomycosis include granulomas and acid-fast bacilli in histiocytes.6

Noninfectious etiologies in the differential may include cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma or pemphigus vegetans. Squamous cell carcinoma may present with a broad range of clinical features—papules, plaques, or nodules with smooth, scaly, verrucous, or ulcerative secondary features all are possible presentations.7 Fairskinned individuals, such as our patient, would be at a higher risk in sun-damaged skin. Histologically, cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma is defined as an invasion of the dermis by neoplastic squamous epithelial cells in the form of cords, sheets, individual cells, nodules, or cystic structures.7 Pemphigus vegetans is the rarest variant of a group of autoimmune vesiculobullous diseases known as pemphigus. It can be differentiated from the most common variant—pemphigus vulgaris—by the presence of vegetative plaques in intertriginous areas. However, these verrucous vegetations can be misleading and make clinical diagnosis difficult. Histopathologic findings of hyperkeratosis, pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, papillomatosis, and acantholysis with a suprabasal cleft would confirm the diagnosis.8

In summary, cutaneous blastomycosis classically presents as verrucous crusting plaques, as seen in our patient. It is important to conduct a thorough history for environmental exposures, but definitive diagnosis of cutaneous blastomycosis involves skin biopsy with fungal culture. Treatment depends on the severity of disease and organ involvement. Itraconazole would be appropriate for mild to moderate blastomycosis.

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Blastomycosis

A skin biopsy and fungal cultures confirmed the diagnosis of cutaneous blastomycosis. Grocott- Gomori methenamine-silver staining highlighted fungal organisms with refractile walls and broad-based budding consistent with cutaneous blastomycosis (Figure 1). The histopathologic specimen also demonstrated marked pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia (Figure 2A) with neutrophilic microabscesses (Figure 2B). Acid-fast bacillus and Fite staining were negative for bacterial organisms. A fungal culture was positive for Blastomyces dermatitidis. Urine and serum blastomycosis antigen were positive. Although Histoplasma serum antigen also was positive, this likely was from cross-reactivity. Chest radiography was negative for lung involvement, and the patient displayed no neurologic symptoms. He was started on oral itraconazole therapy for the treatment of cutaneous blastomycosis.

Blastomyces dermatitidis, the causative organism of blastomycosis, is endemic to the Ohio and Mississippi River valleys, Great Lakes region, and southeastern United States. It is a thermally dimorphic fungus found in soils that grows as a mold at 25 °C and yeast at 37 °C. Primary infection of the lungs—blastomycosis pneumonia—often is the only clinical manifestation1; however, subsequent hematogenous dissemination to extrapulmonary sites such as the skin, bones, and genitourinary system can occur. Cutaneous blastomycosis, the most common extrapulmonary manifestation, typically follows pulmonary infection. In rare cases, it can occur from direct inoculation.2,3 Skin lesions can occur anywhere but frequently are found on exposed surfaces of the head, neck, and extremities. Lesions classically present as verrucous crusting plaques with draining microabscesses. Violaceous nodules, ulcers, and pustules also may occur.1

Diagnosis involves obtaining a thorough history of possible environmental exposures such as the patient’s geographic area of residence, occupation, and outdoor activities involving soil or decaying wood. Because blastomycosis can remain latent, remote exposures are relevant. Definitive diagnosis of cutaneous blastomycosis involves skin biopsy of the lesion with fungal culture, but the yeast’s distinctive thick wall and broad-based budding seen with periodic acid–Schiff or Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver staining provides a rapid presumptive diagnosis.3 Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia and microabscesses also are characteristic features.2 Urine antigen testing for a component of the polysaccharide cell wall has a sensitivity of 93% but a lower specificity of 79% due to cross-reactivity with histoplasmosis.4 Treatment consists of itraconazole for mild to moderate blastomycosis or amphotericin B for those with severe disease or central nervous system involvement or those who are immunosuppressed.1

The differential diagnosis for our patient’s lesion included infectious vs neoplastic etiologies. Histoplasma capsulatum, the dimorphic fungus that causes histoplasmosis, also is endemic to the Ohio and Mississippi River valleys. It is found in soil and droppings of some bats and birds such as chickens and pigeons. Similar to blastomycosis, the primary infection site most commonly is the lungs. It subsequently may disseminate to the skin or less commonly via direct inoculation of injured skin. It can present as papules, plaques, ulcers, purpura, or abscesses. Unlike blastomycosis, tissue biopsy of a cutaneous lesion reveals granuloma formation and distinctive oval, narrow-based budding yeast.5 Atypical mycobacteria are another source of infection to consider. For example, cutaneous Mycobacterium kansasii may present as papules and pustules forming verrucous or granulomatous plaques and ulceration. Histopathologic findings distinguishing mycobacterial infection from blastomycosis include granulomas and acid-fast bacilli in histiocytes.6

Noninfectious etiologies in the differential may include cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma or pemphigus vegetans. Squamous cell carcinoma may present with a broad range of clinical features—papules, plaques, or nodules with smooth, scaly, verrucous, or ulcerative secondary features all are possible presentations.7 Fairskinned individuals, such as our patient, would be at a higher risk in sun-damaged skin. Histologically, cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma is defined as an invasion of the dermis by neoplastic squamous epithelial cells in the form of cords, sheets, individual cells, nodules, or cystic structures.7 Pemphigus vegetans is the rarest variant of a group of autoimmune vesiculobullous diseases known as pemphigus. It can be differentiated from the most common variant—pemphigus vulgaris—by the presence of vegetative plaques in intertriginous areas. However, these verrucous vegetations can be misleading and make clinical diagnosis difficult. Histopathologic findings of hyperkeratosis, pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, papillomatosis, and acantholysis with a suprabasal cleft would confirm the diagnosis.8

In summary, cutaneous blastomycosis classically presents as verrucous crusting plaques, as seen in our patient. It is important to conduct a thorough history for environmental exposures, but definitive diagnosis of cutaneous blastomycosis involves skin biopsy with fungal culture. Treatment depends on the severity of disease and organ involvement. Itraconazole would be appropriate for mild to moderate blastomycosis.

- Miceli A, Krishnamurthy K. Blastomycosis. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. Accessed June 21, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441987/

- Gray NA, Baddour LM. Cutaneous inoculation blastomycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:E44-E49.

- Schwartz IS, Kauffman CA. Blastomycosis. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;41:31-41. doi:10.1055/s-0039-3400281

- Castillo CG, Kauffman CA, Miceli MH. Blastomycosis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2016;30:247-264. doi:10.1016/j.idc.2015.10.002

- Raggio B. Primary cutaneous histoplasmosis. Ear Nose Throat J. 2018;97:346-348.

- Bhambri S, Bhambri A, Del Rosso JQ. Atypical mycobacterial cutaneous infections. Dermatol Clin. 2009;27:63-73. doi:10.1016/j.det.2008.07.009

- Parekh V, Seykora JT. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Clin Lab Med. 2017;37:503-525. doi:10.1016/j.cll.2017.06.003

- Messersmith L, Krauland K. Pemphigus vegetans. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. Accessed June 21, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK545229/

- Miceli A, Krishnamurthy K. Blastomycosis. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. Accessed June 21, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441987/

- Gray NA, Baddour LM. Cutaneous inoculation blastomycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:E44-E49.

- Schwartz IS, Kauffman CA. Blastomycosis. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;41:31-41. doi:10.1055/s-0039-3400281

- Castillo CG, Kauffman CA, Miceli MH. Blastomycosis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2016;30:247-264. doi:10.1016/j.idc.2015.10.002

- Raggio B. Primary cutaneous histoplasmosis. Ear Nose Throat J. 2018;97:346-348.

- Bhambri S, Bhambri A, Del Rosso JQ. Atypical mycobacterial cutaneous infections. Dermatol Clin. 2009;27:63-73. doi:10.1016/j.det.2008.07.009

- Parekh V, Seykora JT. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Clin Lab Med. 2017;37:503-525. doi:10.1016/j.cll.2017.06.003

- Messersmith L, Krauland K. Pemphigus vegetans. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. Accessed June 21, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK545229/

A 39-year-old man from Ohio presented with a tender, 10×6-cm, fungated, eroded plaque on the right medial upper arm that developed over the last 4 years. He initially noticed a firm lump under the right arm 4 years prior that was diagnosed as possible cellulitis at an outside clinic and treated with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. The lesion then began to erode and became a chronic nonhealing wound. Approximately 1 year prior to the current presentation, the patient recalled unloading a truckload of soil around the same time the wound began to enlarge in diameter and depth. He denied any prior or current respiratory or systemic symptoms including fevers, chills, or weight loss.

Large Leg Ulcers After Swimming in the Ocean

The Diagnosis: Vibrio vulnificus Infection

At the initial presentation, the differential diagnosis included infectious processes such as bacterial or angioinvasive fungal infections or an inflammatory process such as pyoderma gangrenosum. Blood cultures were found to be positive for pansensitive Vibrio vulnificus. He initially was treated with piperacillin-tazobactam and received surgical debridement of the affected tissues. Pathologic interpretation of the wound tissues revealed a diagnosis of necrotizing softtissue infection and positive Candida albicans growth. He received topical bacitracin on discharge as well as a 7-day course of amoxicillin-clavulanate and fluconazole. He continued to receive debridement procedures and skin grafts, followed by topical mupirocin treatment and silver sulfadiazine. He was seen 6 weeks after discharge with healing wounds and healthy-appearing granulation tissue at the base.

Our patient’s presentation of retiform purpura with stellate necrosis was consistent with a wide range of serious pathologies ranging from medium-vessel vasculitis to thromboembolic phenomena and angioinvasive fungal infections.1 Although Vibrio infection rarely is the first explanation that comes to mind when observing necrotic retiform purpura, the chronic nonhealing injury on the leg combined with the recent history of ocean swimming made V vulnificus stand out as a likely culprit. Although V vulnificus infection traditionally presents with cellulitis, edema, and hemorrhagic bulla,2 necrosis also has been observed.3Vibrio vulnificus produces multiple virulence factors, and it is believed that these severe cutaneous symptoms are attributable to the production of a specific metalloprotease that enhances vascular permeability, thereby inducing hemorrhage within the vascular basement membrane zone.2

Vibrio vulnificus is an opportunistic bacterial pathogen associated with consumption of contaminated seafood or swimming in ocean waters with open wounds. Infections are rare, with only approximately 100 cases reported annually in the United States.4 However, V vulnificus infections have demonstrated increasing incidence in recent years, especially infections of pre-existing wounds.4,5 Risk factors for their development include age over 40 years and underlying conditions including liver disease, diabetes mellitus, and immune dysfunction.4Vibrio vulnificus infections also demonstrate a strong male predilection, with almost 90% of infections occurring in males.4 Although the precise etiology of this sex discrepancy remains unknown, estrogen has been suggested to be a protective factor.6 Alternatively, behavioral differences also have been proposed as possible explanations for this discrepancy, with women less likely to consume seafood or go swimming. However, epidemiologic data reveal strong correlations between male sex and liver cirrhosis, a primary risk factor for V vulnificus infections, suggesting that male sex may simply be a confounding variable.7

Infections with V vulnificus are notable for their short incubation periods, with onset of symptoms occurring within 24 hours of exposure, making prompt diagnosis and treatment of high importance.8 Although rare, V vulnificus infections are associated with high mortality rates. From 1988 to 2010, nearly 600 deaths were reported secondary to V vulnificus infections.4 Wound infections carry a 17.6% fatality rate,4 while bloodborne V vulnificus infections exceed 50% fatality.8 Although sepsis secondary to V vulnificus usually is caused by ingestion of raw or undercooked shellfish, primarily oysters,4 our case highlights a rarer instance of both sepsis and localized infection stemming from ocean water exposure.

Vibrio vulnificus is an obligate halophile and therefore is found in marine environments rather than freshwater bodies. However, it rarely is isolated from bodies of water with salinities over 25 parts per thousand, such as the Mediterranean Sea; it usually is found in warmer waters, making it more common in the summer months from May to October.4 Given this proclivity for warmer environments, climate change has contributed to both a greater incidence and global distribution of V vulnificus. 9,10

Treatment of V vulnificus infections centers on antibiotic treatment, with Vibrio species generally demonstrating susceptibility to most antibiotics of human significance.11 However, some Vibrio isolates within the United States have demonstrated antibiotic resistance; 45% of a variety of clinical and environmental samples from South Carolina and Georgia demonstrated resistance to at least 3 antibiotic classes, and 17.3% resisted 8 or more classes of antibiotics.12 These included medications such as doxycycline, tetracycline, aminoglycosides, and cephalosporins—agents that normally are prescribed for V vulnificus infections. Although tetracyclines have long been touted as the preferred treatment of V vulnificus infections, the spread of antibiotic resistance may require greater reliance on alternative regimens such as combinations of cephalosporins and doxycycline or a single fluoroquinolone.13 Although rare, Vibrio infections can have rapidly fatal consequences and should be given serious consideration when evaluating patients with relevant risk factors.

The differential diagnosis included angioinvasive mucormycosis, calciphylaxis, pyoderma gangrenosum, and Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis. Mucormycosis is a fungal infection caused by Mucorales fungi that most commonly is seen in patients with diabetes mellitus, hematologic malignancies, neutropenia, and immunocompromise.14 Calciphylaxis is a condition involving microvascular occlusion due to diffuse calcium deposition in cutaneous blood vessels. It typically presents as violaceous retiform patches and plaques commonly seen on areas such as the thighs, buttocks, or abdomen and usually is associated with chronic renal failure, hemodialysis, and/or secondary hyperparathyroidism.15 Pyoderma gangrenosum is an inflammatory condition involving neutrophilic ulceration of the skin that typically presents as ulceration with a classically undermined border. It frequently is considered a diagnosis of exclusion and therefore requires that providers rule out other causes of ulceration prior to diagnosis.16 Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis is a rare drug reaction involving mucosal erosions and cutaneous detachment.17 This diagnosis is less likely given that our patient lacked mucosal involvement and did not have any notable medication exposures prior to symptom onset.

- Wysong A, Venkatesan P. An approach to the patient with retiform purpura. Dermatol Ther. 2011;24:151-172. doi:10.1111/j .1529-8019.2011.01392.x

- Miyoshi S-I. Vibrio vulnificus infection and metalloprotease. J Dermatol. 2006;33:589-595. doi:10.1111/j.1346-8138.2006.00139.x

- Patel VJ, Gardner E, Burton CS. Vibrio vulnificus septicemia and leg ulcer. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46(5 suppl):S144-S145. doi:10.1067 /mjd.2002.107778

- Baker-Austin C, Oliver JD. Vibrio vulnificus: new insights into a deadly opportunistic pathogen. Environ Microbiol. 2018;20:423-430. doi:10.1111/1462-2920.13955

- Preliminary FoodNet data on the incidence of infection with pathogens transmitted commonly through food —10 states, 2009. CDC website. Published April 16, 2010. Accessed November 3, 2021. https://www.cdc .gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5914a2.htm

- Merkel SM, Alexander S, Zufall E, et al. Essential role for estrogen in protection against Vibrio vulnificus-induced endotoxic shock. Infect Immun. 2001;69:6119-6122. doi:10.1128/IAI.69.10.6119 -6122.2001

- Scaglione S, Kliethermes S, Cao G, et al. The epidemiology of cirrhosis in the United States: a population-based study. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2015;49:690-696. doi:10.1097/MCG.0000000000000208

- Jones M, Oliver J. Vibrio vulnificus: disease and pathogenesis [published online December 20, 2020]. Infect Immun. https://doi.org/10.1128 /IAI.01046-08

- Paz S, Bisharat N, Paz E, et al. Climate change and the emergence of Vibrio vulnificus disease in Israel. Environ Res. 2007;103:390-396. doi:10.1016/j.envres.2006.07.002

- Martinez-Urtaza J, Bowers JC, Trinanes J, et al. Climate anomalies and the increasing risk of Vibrio parahaemolyticus and Vibrio vulnificus illnesses. Food Res Int. 2010;43:1780-1790. doi:10.1016/j. foodres.2010.04.001

- Oliver JD. Vibrio vulnificus. In: Thompson FL, Austin B, Swings J, eds. The Biology of Vibrios. ASM Press; 2006:349-366.

- Baker-Austin C, McArthur JV, Lindell AH, et al. Multi-site analysis reveals widespread antibiotic resistance in the marine pathogen Vibrio vulnificus. Microb Ecol. 2009;57:151-159. doi:10.1007 /s00248-008-9413-8

- Elmahdi S, DaSilva LV, Parveen S. Antibiotic resistance of Vibrio parahaemolyticus and Vibrio vulnificus in various countries: a review. Food Microbiol. 2016;57:128-134. doi:10.1016/j.fm.2016.02.008

- Prasad P, Wong V, Burgin S, et al. Mucormycosis. VisualDx website. Accessed November 13, 2021. https://www-visualdx-com.proxy.lib.ohio-state.edu/visualdx/diagnosis/mucormycosis?diagnosisId=51981 &moduleId=101

- Blum A, Song P, Tan B, et al. Calciphylaxis. VisualDx website. Accessed November 13, 2021. https://www-visualdx-com.proxy.lib.ohio-state.edu/visualdx/diagnosis/calciphylaxis?diagnosisId=51241&moduleId=101

- Cohen J, Wong V, Burgin S. Pyoderma gangrenosum. VisualDx website. Accessed November 13, 2021. https://www-visualdx-com.proxy.lib.ohio-state.edu/visualdx/diagnosis/pyoderma+gangrenosum?diagnosis Id=52242&moduleId=101

- Walls A, Burgin S. Stevens-Johnson syndrome. VisualDx website. Accessed November 13, 2021. https://www-visualdx-com.proxy.lib.ohio-state.edu/visualdx/diagnosis/stevens-johnson+syndrome?diagnosisId=52342&moduleId=101

The Diagnosis: Vibrio vulnificus Infection

At the initial presentation, the differential diagnosis included infectious processes such as bacterial or angioinvasive fungal infections or an inflammatory process such as pyoderma gangrenosum. Blood cultures were found to be positive for pansensitive Vibrio vulnificus. He initially was treated with piperacillin-tazobactam and received surgical debridement of the affected tissues. Pathologic interpretation of the wound tissues revealed a diagnosis of necrotizing softtissue infection and positive Candida albicans growth. He received topical bacitracin on discharge as well as a 7-day course of amoxicillin-clavulanate and fluconazole. He continued to receive debridement procedures and skin grafts, followed by topical mupirocin treatment and silver sulfadiazine. He was seen 6 weeks after discharge with healing wounds and healthy-appearing granulation tissue at the base.

Our patient’s presentation of retiform purpura with stellate necrosis was consistent with a wide range of serious pathologies ranging from medium-vessel vasculitis to thromboembolic phenomena and angioinvasive fungal infections.1 Although Vibrio infection rarely is the first explanation that comes to mind when observing necrotic retiform purpura, the chronic nonhealing injury on the leg combined with the recent history of ocean swimming made V vulnificus stand out as a likely culprit. Although V vulnificus infection traditionally presents with cellulitis, edema, and hemorrhagic bulla,2 necrosis also has been observed.3Vibrio vulnificus produces multiple virulence factors, and it is believed that these severe cutaneous symptoms are attributable to the production of a specific metalloprotease that enhances vascular permeability, thereby inducing hemorrhage within the vascular basement membrane zone.2

Vibrio vulnificus is an opportunistic bacterial pathogen associated with consumption of contaminated seafood or swimming in ocean waters with open wounds. Infections are rare, with only approximately 100 cases reported annually in the United States.4 However, V vulnificus infections have demonstrated increasing incidence in recent years, especially infections of pre-existing wounds.4,5 Risk factors for their development include age over 40 years and underlying conditions including liver disease, diabetes mellitus, and immune dysfunction.4Vibrio vulnificus infections also demonstrate a strong male predilection, with almost 90% of infections occurring in males.4 Although the precise etiology of this sex discrepancy remains unknown, estrogen has been suggested to be a protective factor.6 Alternatively, behavioral differences also have been proposed as possible explanations for this discrepancy, with women less likely to consume seafood or go swimming. However, epidemiologic data reveal strong correlations between male sex and liver cirrhosis, a primary risk factor for V vulnificus infections, suggesting that male sex may simply be a confounding variable.7

Infections with V vulnificus are notable for their short incubation periods, with onset of symptoms occurring within 24 hours of exposure, making prompt diagnosis and treatment of high importance.8 Although rare, V vulnificus infections are associated with high mortality rates. From 1988 to 2010, nearly 600 deaths were reported secondary to V vulnificus infections.4 Wound infections carry a 17.6% fatality rate,4 while bloodborne V vulnificus infections exceed 50% fatality.8 Although sepsis secondary to V vulnificus usually is caused by ingestion of raw or undercooked shellfish, primarily oysters,4 our case highlights a rarer instance of both sepsis and localized infection stemming from ocean water exposure.

Vibrio vulnificus is an obligate halophile and therefore is found in marine environments rather than freshwater bodies. However, it rarely is isolated from bodies of water with salinities over 25 parts per thousand, such as the Mediterranean Sea; it usually is found in warmer waters, making it more common in the summer months from May to October.4 Given this proclivity for warmer environments, climate change has contributed to both a greater incidence and global distribution of V vulnificus. 9,10

Treatment of V vulnificus infections centers on antibiotic treatment, with Vibrio species generally demonstrating susceptibility to most antibiotics of human significance.11 However, some Vibrio isolates within the United States have demonstrated antibiotic resistance; 45% of a variety of clinical and environmental samples from South Carolina and Georgia demonstrated resistance to at least 3 antibiotic classes, and 17.3% resisted 8 or more classes of antibiotics.12 These included medications such as doxycycline, tetracycline, aminoglycosides, and cephalosporins—agents that normally are prescribed for V vulnificus infections. Although tetracyclines have long been touted as the preferred treatment of V vulnificus infections, the spread of antibiotic resistance may require greater reliance on alternative regimens such as combinations of cephalosporins and doxycycline or a single fluoroquinolone.13 Although rare, Vibrio infections can have rapidly fatal consequences and should be given serious consideration when evaluating patients with relevant risk factors.

The differential diagnosis included angioinvasive mucormycosis, calciphylaxis, pyoderma gangrenosum, and Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis. Mucormycosis is a fungal infection caused by Mucorales fungi that most commonly is seen in patients with diabetes mellitus, hematologic malignancies, neutropenia, and immunocompromise.14 Calciphylaxis is a condition involving microvascular occlusion due to diffuse calcium deposition in cutaneous blood vessels. It typically presents as violaceous retiform patches and plaques commonly seen on areas such as the thighs, buttocks, or abdomen and usually is associated with chronic renal failure, hemodialysis, and/or secondary hyperparathyroidism.15 Pyoderma gangrenosum is an inflammatory condition involving neutrophilic ulceration of the skin that typically presents as ulceration with a classically undermined border. It frequently is considered a diagnosis of exclusion and therefore requires that providers rule out other causes of ulceration prior to diagnosis.16 Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis is a rare drug reaction involving mucosal erosions and cutaneous detachment.17 This diagnosis is less likely given that our patient lacked mucosal involvement and did not have any notable medication exposures prior to symptom onset.

The Diagnosis: Vibrio vulnificus Infection

At the initial presentation, the differential diagnosis included infectious processes such as bacterial or angioinvasive fungal infections or an inflammatory process such as pyoderma gangrenosum. Blood cultures were found to be positive for pansensitive Vibrio vulnificus. He initially was treated with piperacillin-tazobactam and received surgical debridement of the affected tissues. Pathologic interpretation of the wound tissues revealed a diagnosis of necrotizing softtissue infection and positive Candida albicans growth. He received topical bacitracin on discharge as well as a 7-day course of amoxicillin-clavulanate and fluconazole. He continued to receive debridement procedures and skin grafts, followed by topical mupirocin treatment and silver sulfadiazine. He was seen 6 weeks after discharge with healing wounds and healthy-appearing granulation tissue at the base.

Our patient’s presentation of retiform purpura with stellate necrosis was consistent with a wide range of serious pathologies ranging from medium-vessel vasculitis to thromboembolic phenomena and angioinvasive fungal infections.1 Although Vibrio infection rarely is the first explanation that comes to mind when observing necrotic retiform purpura, the chronic nonhealing injury on the leg combined with the recent history of ocean swimming made V vulnificus stand out as a likely culprit. Although V vulnificus infection traditionally presents with cellulitis, edema, and hemorrhagic bulla,2 necrosis also has been observed.3Vibrio vulnificus produces multiple virulence factors, and it is believed that these severe cutaneous symptoms are attributable to the production of a specific metalloprotease that enhances vascular permeability, thereby inducing hemorrhage within the vascular basement membrane zone.2

Vibrio vulnificus is an opportunistic bacterial pathogen associated with consumption of contaminated seafood or swimming in ocean waters with open wounds. Infections are rare, with only approximately 100 cases reported annually in the United States.4 However, V vulnificus infections have demonstrated increasing incidence in recent years, especially infections of pre-existing wounds.4,5 Risk factors for their development include age over 40 years and underlying conditions including liver disease, diabetes mellitus, and immune dysfunction.4Vibrio vulnificus infections also demonstrate a strong male predilection, with almost 90% of infections occurring in males.4 Although the precise etiology of this sex discrepancy remains unknown, estrogen has been suggested to be a protective factor.6 Alternatively, behavioral differences also have been proposed as possible explanations for this discrepancy, with women less likely to consume seafood or go swimming. However, epidemiologic data reveal strong correlations between male sex and liver cirrhosis, a primary risk factor for V vulnificus infections, suggesting that male sex may simply be a confounding variable.7

Infections with V vulnificus are notable for their short incubation periods, with onset of symptoms occurring within 24 hours of exposure, making prompt diagnosis and treatment of high importance.8 Although rare, V vulnificus infections are associated with high mortality rates. From 1988 to 2010, nearly 600 deaths were reported secondary to V vulnificus infections.4 Wound infections carry a 17.6% fatality rate,4 while bloodborne V vulnificus infections exceed 50% fatality.8 Although sepsis secondary to V vulnificus usually is caused by ingestion of raw or undercooked shellfish, primarily oysters,4 our case highlights a rarer instance of both sepsis and localized infection stemming from ocean water exposure.

Vibrio vulnificus is an obligate halophile and therefore is found in marine environments rather than freshwater bodies. However, it rarely is isolated from bodies of water with salinities over 25 parts per thousand, such as the Mediterranean Sea; it usually is found in warmer waters, making it more common in the summer months from May to October.4 Given this proclivity for warmer environments, climate change has contributed to both a greater incidence and global distribution of V vulnificus. 9,10

Treatment of V vulnificus infections centers on antibiotic treatment, with Vibrio species generally demonstrating susceptibility to most antibiotics of human significance.11 However, some Vibrio isolates within the United States have demonstrated antibiotic resistance; 45% of a variety of clinical and environmental samples from South Carolina and Georgia demonstrated resistance to at least 3 antibiotic classes, and 17.3% resisted 8 or more classes of antibiotics.12 These included medications such as doxycycline, tetracycline, aminoglycosides, and cephalosporins—agents that normally are prescribed for V vulnificus infections. Although tetracyclines have long been touted as the preferred treatment of V vulnificus infections, the spread of antibiotic resistance may require greater reliance on alternative regimens such as combinations of cephalosporins and doxycycline or a single fluoroquinolone.13 Although rare, Vibrio infections can have rapidly fatal consequences and should be given serious consideration when evaluating patients with relevant risk factors.

The differential diagnosis included angioinvasive mucormycosis, calciphylaxis, pyoderma gangrenosum, and Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis. Mucormycosis is a fungal infection caused by Mucorales fungi that most commonly is seen in patients with diabetes mellitus, hematologic malignancies, neutropenia, and immunocompromise.14 Calciphylaxis is a condition involving microvascular occlusion due to diffuse calcium deposition in cutaneous blood vessels. It typically presents as violaceous retiform patches and plaques commonly seen on areas such as the thighs, buttocks, or abdomen and usually is associated with chronic renal failure, hemodialysis, and/or secondary hyperparathyroidism.15 Pyoderma gangrenosum is an inflammatory condition involving neutrophilic ulceration of the skin that typically presents as ulceration with a classically undermined border. It frequently is considered a diagnosis of exclusion and therefore requires that providers rule out other causes of ulceration prior to diagnosis.16 Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis is a rare drug reaction involving mucosal erosions and cutaneous detachment.17 This diagnosis is less likely given that our patient lacked mucosal involvement and did not have any notable medication exposures prior to symptom onset.

- Wysong A, Venkatesan P. An approach to the patient with retiform purpura. Dermatol Ther. 2011;24:151-172. doi:10.1111/j .1529-8019.2011.01392.x

- Miyoshi S-I. Vibrio vulnificus infection and metalloprotease. J Dermatol. 2006;33:589-595. doi:10.1111/j.1346-8138.2006.00139.x

- Patel VJ, Gardner E, Burton CS. Vibrio vulnificus septicemia and leg ulcer. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46(5 suppl):S144-S145. doi:10.1067 /mjd.2002.107778

- Baker-Austin C, Oliver JD. Vibrio vulnificus: new insights into a deadly opportunistic pathogen. Environ Microbiol. 2018;20:423-430. doi:10.1111/1462-2920.13955

- Preliminary FoodNet data on the incidence of infection with pathogens transmitted commonly through food —10 states, 2009. CDC website. Published April 16, 2010. Accessed November 3, 2021. https://www.cdc .gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5914a2.htm

- Merkel SM, Alexander S, Zufall E, et al. Essential role for estrogen in protection against Vibrio vulnificus-induced endotoxic shock. Infect Immun. 2001;69:6119-6122. doi:10.1128/IAI.69.10.6119 -6122.2001

- Scaglione S, Kliethermes S, Cao G, et al. The epidemiology of cirrhosis in the United States: a population-based study. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2015;49:690-696. doi:10.1097/MCG.0000000000000208

- Jones M, Oliver J. Vibrio vulnificus: disease and pathogenesis [published online December 20, 2020]. Infect Immun. https://doi.org/10.1128 /IAI.01046-08

- Paz S, Bisharat N, Paz E, et al. Climate change and the emergence of Vibrio vulnificus disease in Israel. Environ Res. 2007;103:390-396. doi:10.1016/j.envres.2006.07.002

- Martinez-Urtaza J, Bowers JC, Trinanes J, et al. Climate anomalies and the increasing risk of Vibrio parahaemolyticus and Vibrio vulnificus illnesses. Food Res Int. 2010;43:1780-1790. doi:10.1016/j. foodres.2010.04.001

- Oliver JD. Vibrio vulnificus. In: Thompson FL, Austin B, Swings J, eds. The Biology of Vibrios. ASM Press; 2006:349-366.

- Baker-Austin C, McArthur JV, Lindell AH, et al. Multi-site analysis reveals widespread antibiotic resistance in the marine pathogen Vibrio vulnificus. Microb Ecol. 2009;57:151-159. doi:10.1007 /s00248-008-9413-8

- Elmahdi S, DaSilva LV, Parveen S. Antibiotic resistance of Vibrio parahaemolyticus and Vibrio vulnificus in various countries: a review. Food Microbiol. 2016;57:128-134. doi:10.1016/j.fm.2016.02.008

- Prasad P, Wong V, Burgin S, et al. Mucormycosis. VisualDx website. Accessed November 13, 2021. https://www-visualdx-com.proxy.lib.ohio-state.edu/visualdx/diagnosis/mucormycosis?diagnosisId=51981 &moduleId=101

- Blum A, Song P, Tan B, et al. Calciphylaxis. VisualDx website. Accessed November 13, 2021. https://www-visualdx-com.proxy.lib.ohio-state.edu/visualdx/diagnosis/calciphylaxis?diagnosisId=51241&moduleId=101

- Cohen J, Wong V, Burgin S. Pyoderma gangrenosum. VisualDx website. Accessed November 13, 2021. https://www-visualdx-com.proxy.lib.ohio-state.edu/visualdx/diagnosis/pyoderma+gangrenosum?diagnosis Id=52242&moduleId=101

- Walls A, Burgin S. Stevens-Johnson syndrome. VisualDx website. Accessed November 13, 2021. https://www-visualdx-com.proxy.lib.ohio-state.edu/visualdx/diagnosis/stevens-johnson+syndrome?diagnosisId=52342&moduleId=101

- Wysong A, Venkatesan P. An approach to the patient with retiform purpura. Dermatol Ther. 2011;24:151-172. doi:10.1111/j .1529-8019.2011.01392.x

- Miyoshi S-I. Vibrio vulnificus infection and metalloprotease. J Dermatol. 2006;33:589-595. doi:10.1111/j.1346-8138.2006.00139.x

- Patel VJ, Gardner E, Burton CS. Vibrio vulnificus septicemia and leg ulcer. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46(5 suppl):S144-S145. doi:10.1067 /mjd.2002.107778

- Baker-Austin C, Oliver JD. Vibrio vulnificus: new insights into a deadly opportunistic pathogen. Environ Microbiol. 2018;20:423-430. doi:10.1111/1462-2920.13955

- Preliminary FoodNet data on the incidence of infection with pathogens transmitted commonly through food —10 states, 2009. CDC website. Published April 16, 2010. Accessed November 3, 2021. https://www.cdc .gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5914a2.htm

- Merkel SM, Alexander S, Zufall E, et al. Essential role for estrogen in protection against Vibrio vulnificus-induced endotoxic shock. Infect Immun. 2001;69:6119-6122. doi:10.1128/IAI.69.10.6119 -6122.2001

- Scaglione S, Kliethermes S, Cao G, et al. The epidemiology of cirrhosis in the United States: a population-based study. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2015;49:690-696. doi:10.1097/MCG.0000000000000208

- Jones M, Oliver J. Vibrio vulnificus: disease and pathogenesis [published online December 20, 2020]. Infect Immun. https://doi.org/10.1128 /IAI.01046-08

- Paz S, Bisharat N, Paz E, et al. Climate change and the emergence of Vibrio vulnificus disease in Israel. Environ Res. 2007;103:390-396. doi:10.1016/j.envres.2006.07.002

- Martinez-Urtaza J, Bowers JC, Trinanes J, et al. Climate anomalies and the increasing risk of Vibrio parahaemolyticus and Vibrio vulnificus illnesses. Food Res Int. 2010;43:1780-1790. doi:10.1016/j. foodres.2010.04.001

- Oliver JD. Vibrio vulnificus. In: Thompson FL, Austin B, Swings J, eds. The Biology of Vibrios. ASM Press; 2006:349-366.

- Baker-Austin C, McArthur JV, Lindell AH, et al. Multi-site analysis reveals widespread antibiotic resistance in the marine pathogen Vibrio vulnificus. Microb Ecol. 2009;57:151-159. doi:10.1007 /s00248-008-9413-8

- Elmahdi S, DaSilva LV, Parveen S. Antibiotic resistance of Vibrio parahaemolyticus and Vibrio vulnificus in various countries: a review. Food Microbiol. 2016;57:128-134. doi:10.1016/j.fm.2016.02.008

- Prasad P, Wong V, Burgin S, et al. Mucormycosis. VisualDx website. Accessed November 13, 2021. https://www-visualdx-com.proxy.lib.ohio-state.edu/visualdx/diagnosis/mucormycosis?diagnosisId=51981 &moduleId=101

- Blum A, Song P, Tan B, et al. Calciphylaxis. VisualDx website. Accessed November 13, 2021. https://www-visualdx-com.proxy.lib.ohio-state.edu/visualdx/diagnosis/calciphylaxis?diagnosisId=51241&moduleId=101

- Cohen J, Wong V, Burgin S. Pyoderma gangrenosum. VisualDx website. Accessed November 13, 2021. https://www-visualdx-com.proxy.lib.ohio-state.edu/visualdx/diagnosis/pyoderma+gangrenosum?diagnosis Id=52242&moduleId=101

- Walls A, Burgin S. Stevens-Johnson syndrome. VisualDx website. Accessed November 13, 2021. https://www-visualdx-com.proxy.lib.ohio-state.edu/visualdx/diagnosis/stevens-johnson+syndrome?diagnosisId=52342&moduleId=101

A 48-year-old man presented to the emergency department with pain in both legs after swimming in the ocean surrounding Florida 1 month prior to presentation. His medical history included skin graft treatment of burns during childhood and a chronic lower extremity ulcer that developed after trauma. He received hemodialysis for acute renal failure approximately 1 month prior to the current presentation. At the current presentation he was found to be septic and quickly developed rapidly expanding regions of retiform purpura with stellate necrosis on the legs.