User login

Collision Course of a Basal Cell Carcinoma and Apocrine Hidrocystoma on the Scalp

To the Editor:

A collision tumor is the coexistence of 2 discrete tumors in the same neoplasm, possibly comprising a malignant tumor and a benign tumor, and thereby complicating appropriate diagnosis and treatment. We present a case of a basal cell carcinoma (BCC) of the scalp that was later found to be in collision with an apocrine hidrocystoma that might have arisen from a nevus sebaceus. Although rare, BCC can coexist with apocrine hidrocystoma. Jayaprakasam and Rene1 reported a case of a collision tumor containing BCC and hidrocystoma on the eyelid.1 We present a case of a BCC on the scalp that was later found to be in collision with an apocrine hidrocystoma that possibly arose from a nevus sebaceus.

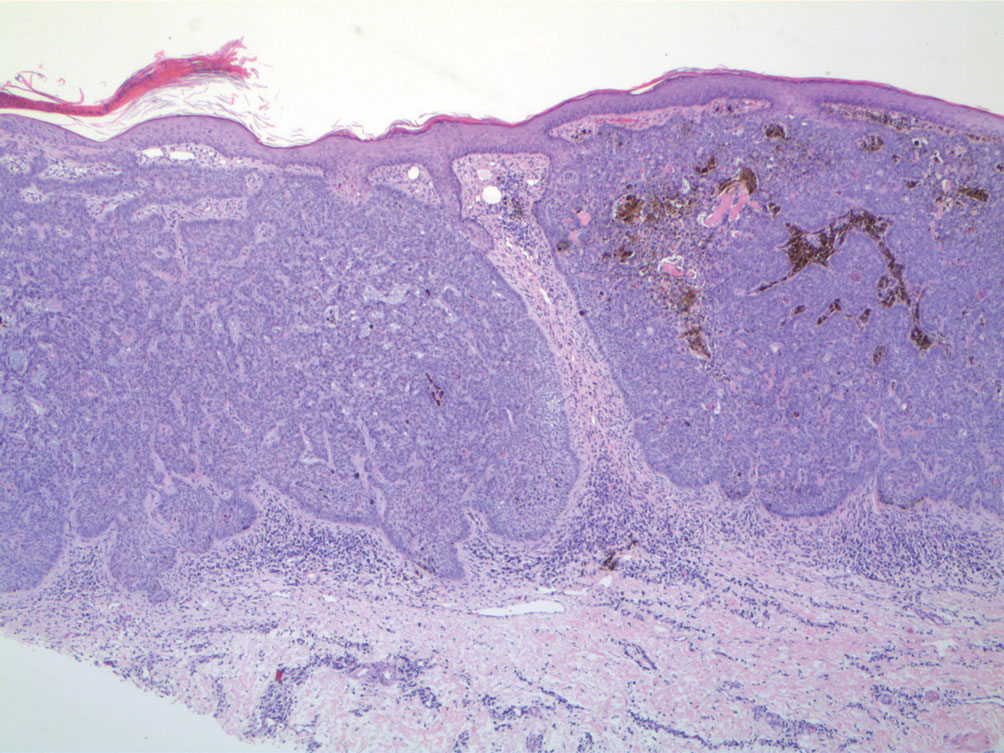

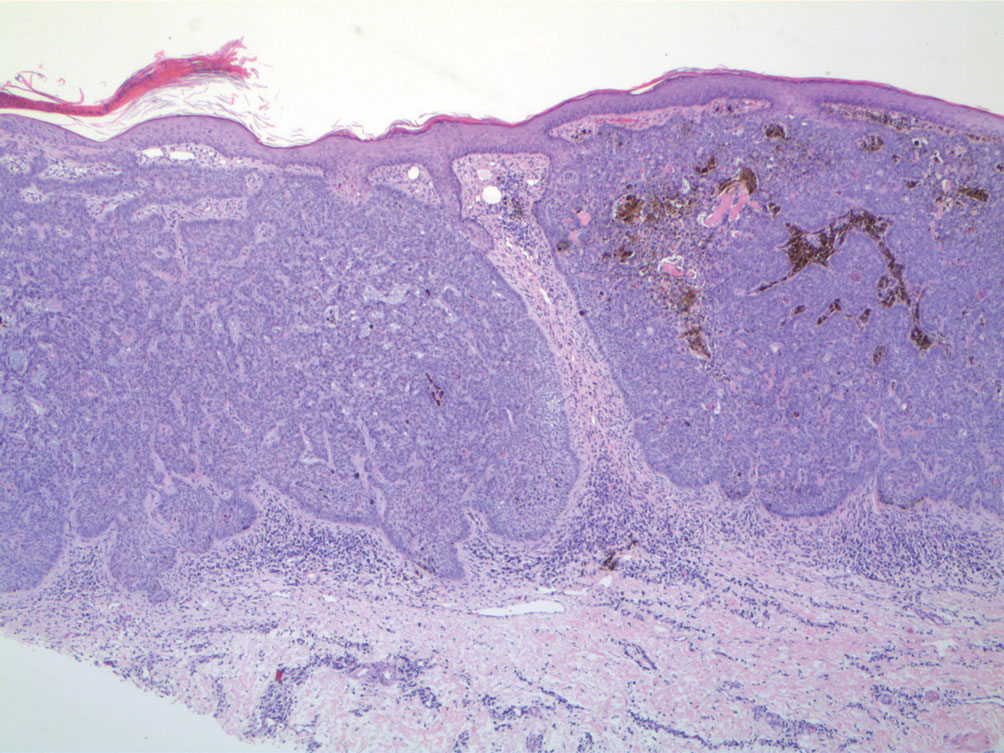

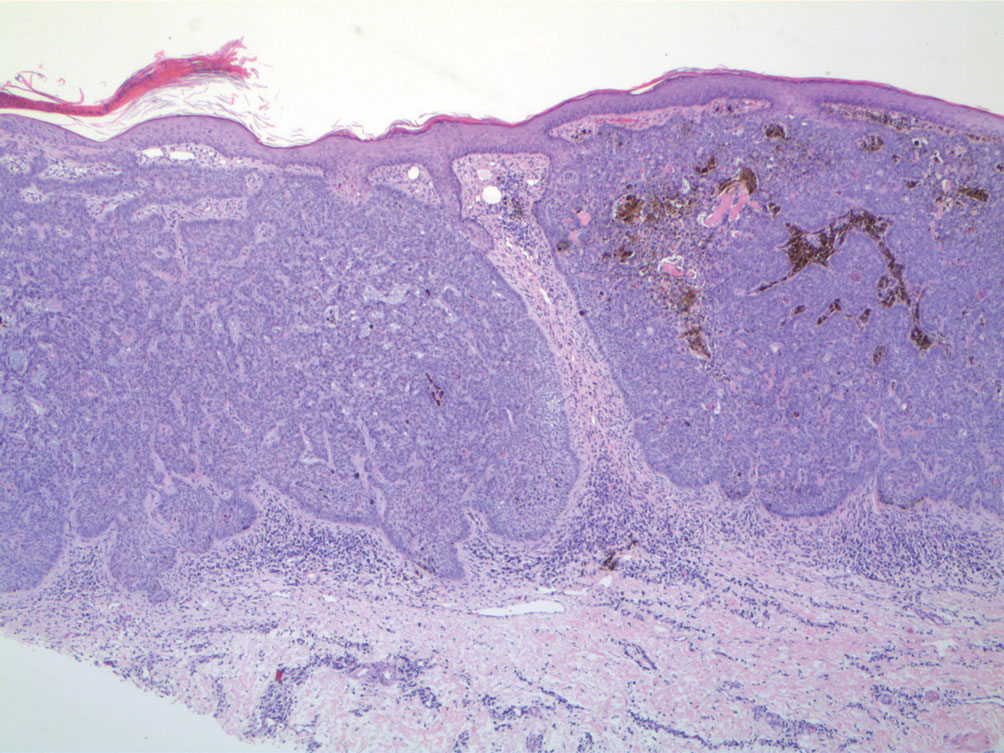

A 92-year-old Black woman with a biopsy-confirmed primary BCC of the left parietal scalp presented for Mohs micrographic surgery. The pathology report from an outside facility was reviewed. The initial diagnosis had been made with 2 punch biopsies from separate areas of the large nodule—one consistent with nodular and pigmented BCC (Figure 1), and the other revealed nodular ulcerated BCC. Physical examination prior to Mohs surgery revealed a mobile, flesh-colored, 6.2×6.0-cm nodule with minimal overlying hair on the left parietal scalp (Figure 2). During stage-I processing by the histopathology laboratory, large cystic structures were encountered; en face frozen sections showed a cystic tumor. Excised tissue was submitted for permanent processing to aid in diagnosis; the initial diagnostic biopsy slides were requested from the outside facility for review.

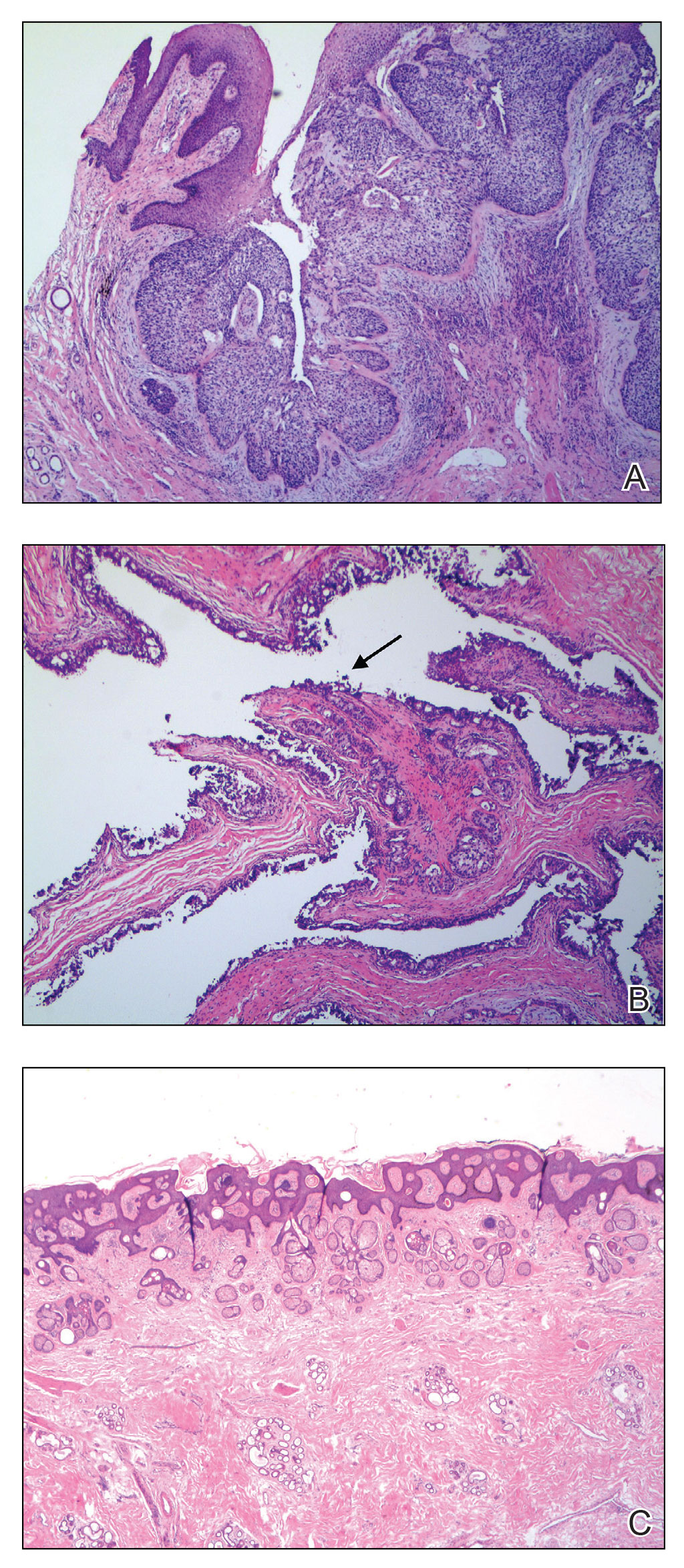

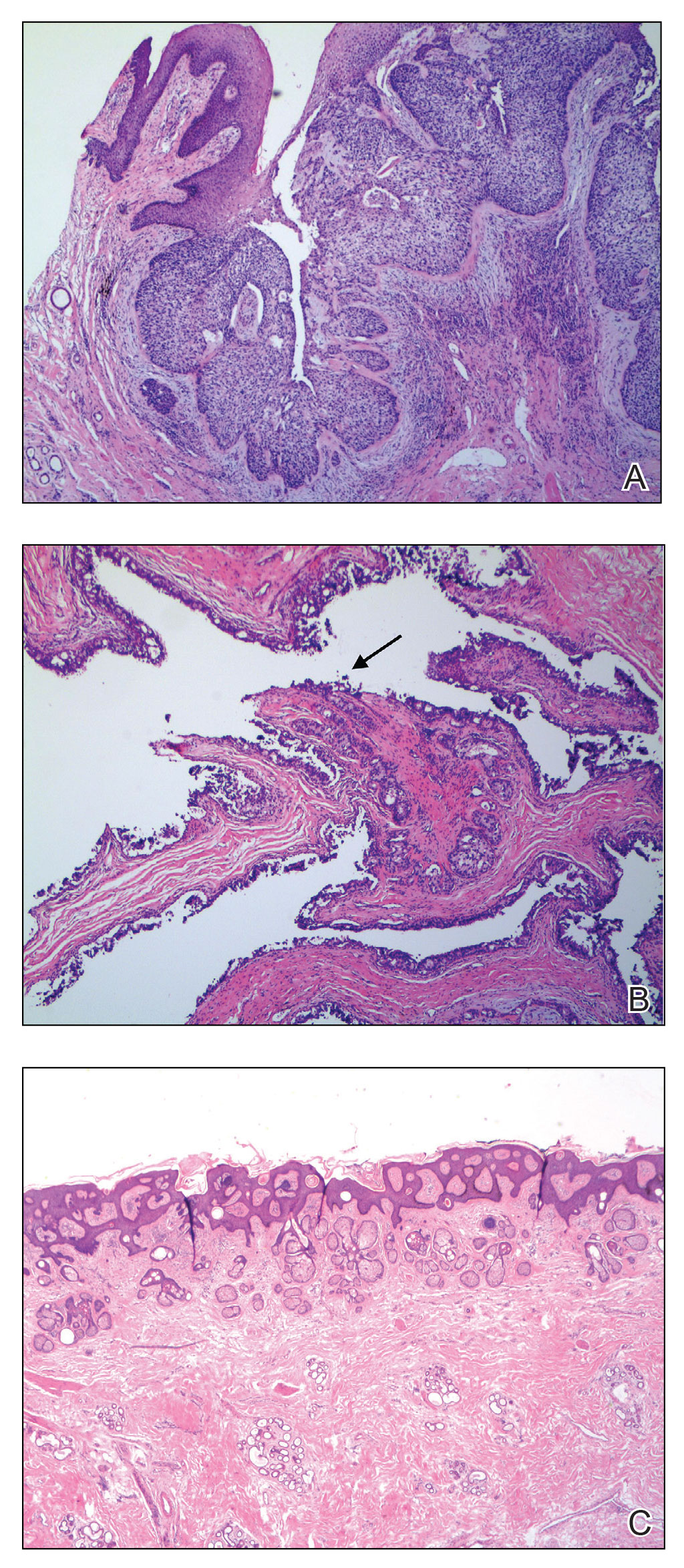

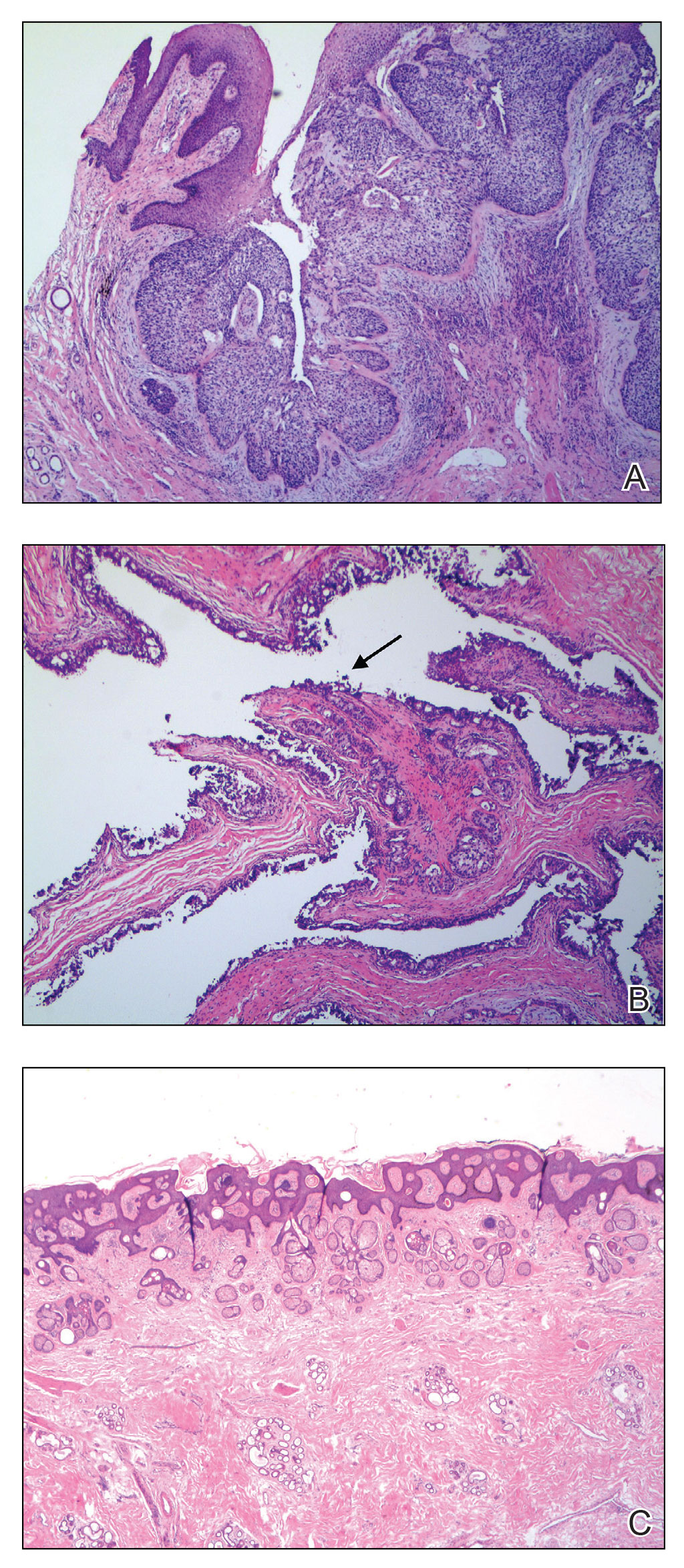

The initial diagnostic biopsy slides were reviewed and found to be consistent with nodular and pigmented BCC, as previously reported. Findings from hematoxylin and eosin staining of tissue obtained from Mohs sections were consistent with a combined neoplasm comprising BCC (Figure 3A) and apocrine hidrocystoma (Figure 3B). In addition, one section was characterized by acanthosis, papillomatosis, and sebaceous glands—similar to findings that are seen in a nevus sebaceus (Figure 3C).

The BCC was cleared after stage I; the final wound size was 7×6.6 cm. Although benign apocrine hidrocystoma was still evident at the margin, further excision was not performed at the request of the patient and her family. Partial primary wound closure was performed with pulley sutures. A xenograft was placed over the unclosed central portion. The wound was permitted to heal by second intention.

The clinical differential diagnosis of a scalp nodule includes a pilar cyst, BCC, squamous cell carcinoma, melanoma, cutaneous metastasis, adnexal tumor, atypical fibroxanthoma, and collision tumor. A collision tumor—the association of 2 or more benign or malignant neoplasms—represents a well-known pitfall in making a correct clinical and pathologic diagnosis.2 Many theories have been proposed to explain the pathophysiology of collision tumors. Some authors have speculated that they arise from involvement of related cell types.1 Other theories include induction by cytokines and growth factors secreted from one tumor that provides an ideal environment for proliferation of other cell types, a field cancerization effect of sun-damaged skin, or a coincidence.2

In our case, it is possible that the 2 tumors arose from a nevus sebaceus. One retrospective study of 706 cases of nevus sebaceus (707 specimens) found that 22.5% of cases developed secondary proliferation; of those cases, 18.9% were benign.3 Additionally, in 4.2% of cases of nevus sebaceus, proliferation of 2 or more tumors developed. The most common malignant neoplasm to develop from nevus sebaceus was BCC, followed by squamous cell carcinoma and sebaceous carcinoma. The most common benign neoplasm to develop from nevus sebaceus was trichoblastoma, followed by syringocystadenoma papilliferum.3

Our case highlights the possibility of a sampling error when performing a biopsy of any large neoplasm. Additionally, Mohs surgeons should maintain high clinical suspicion for collision tumors when encountering a large tumor with pathology inconsistent with the original biopsy. Apocrine hidrocystoma should be considered in the differential diagnosis of a large cystic mass of the scalp. Also, it is important to recognize that malignant lesions, such as BCC, can coexist with another benign tumor. Basal cell carcinoma is rare in Black patients, supporting our belief that our patient’s tumors arose from a nevus sebaceus.

It also is important for Mohs surgeons to consider any potential discrepancy between the initial pathology report and Mohs intraoperative pathology that can impact diagnosis, the aggressiveness of the tumors identified, and how such aggressiveness may affect management options.4,5 Some dermatology practices request biopsy slides from patients who are referred for Mohs micrographic surgery for internal review by a dermatopathologist before surgery is performed; however, this protocol requires additional time and adds costs for the overall health care system.4 One study found that internal review of outside biopsy slides resulted in a change in diagnosis in 2.2% of patients (N=3345)—affecting management in 61% of cases in which the diagnosis was changed.4 Another study (N=163) found that the reported aggressiveness of 50.5% of nonmelanoma cases in an initial biopsy report was changed during Mohs micrographic surgery.5 Mohs surgeons should be aware that discrepancies can occur, and if a discrepancy is discovered, the procedure may be paused until the initial biopsy slide is reviewed and further information is collected.

- Jayaprakasam A, Rene C. A benign or malignant eyelid lump—can you tell? an unusual collision tumour highlighting the difficulty differentiating a hidrocystoma from a basal cell carcinoma. BMJ Case Reports. 2012;2012:bcr1220115307. doi:10.1136/bcr.12.2011.5307

- Miteva M, Herschthal D, Ricotti C, et al. A rare case of a cutaneous squamomelanocytic tumor: revisiting the histogenesis of combined neoplasms. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:599-603. doi:10.1097/DAD.0b013e3181a88116

- Idriss MH, Elston DM. Secondary neoplasms associated with nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn: a study of 707 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:332-337. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2013.10.004

- Butler ST, Youker SR, Mandrell J, et al. The importance of reviewing pathology specimens before Mohs surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:407-412. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2008.01056.x

- Stiegel E, Lam C, Schowalter M, et al. Correlation between original biopsy pathology and Mohs intraoperative pathology. Dermatol Surg. 2018;44:193-197. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000001276

To the Editor:

A collision tumor is the coexistence of 2 discrete tumors in the same neoplasm, possibly comprising a malignant tumor and a benign tumor, and thereby complicating appropriate diagnosis and treatment. We present a case of a basal cell carcinoma (BCC) of the scalp that was later found to be in collision with an apocrine hidrocystoma that might have arisen from a nevus sebaceus. Although rare, BCC can coexist with apocrine hidrocystoma. Jayaprakasam and Rene1 reported a case of a collision tumor containing BCC and hidrocystoma on the eyelid.1 We present a case of a BCC on the scalp that was later found to be in collision with an apocrine hidrocystoma that possibly arose from a nevus sebaceus.

A 92-year-old Black woman with a biopsy-confirmed primary BCC of the left parietal scalp presented for Mohs micrographic surgery. The pathology report from an outside facility was reviewed. The initial diagnosis had been made with 2 punch biopsies from separate areas of the large nodule—one consistent with nodular and pigmented BCC (Figure 1), and the other revealed nodular ulcerated BCC. Physical examination prior to Mohs surgery revealed a mobile, flesh-colored, 6.2×6.0-cm nodule with minimal overlying hair on the left parietal scalp (Figure 2). During stage-I processing by the histopathology laboratory, large cystic structures were encountered; en face frozen sections showed a cystic tumor. Excised tissue was submitted for permanent processing to aid in diagnosis; the initial diagnostic biopsy slides were requested from the outside facility for review.

The initial diagnostic biopsy slides were reviewed and found to be consistent with nodular and pigmented BCC, as previously reported. Findings from hematoxylin and eosin staining of tissue obtained from Mohs sections were consistent with a combined neoplasm comprising BCC (Figure 3A) and apocrine hidrocystoma (Figure 3B). In addition, one section was characterized by acanthosis, papillomatosis, and sebaceous glands—similar to findings that are seen in a nevus sebaceus (Figure 3C).

The BCC was cleared after stage I; the final wound size was 7×6.6 cm. Although benign apocrine hidrocystoma was still evident at the margin, further excision was not performed at the request of the patient and her family. Partial primary wound closure was performed with pulley sutures. A xenograft was placed over the unclosed central portion. The wound was permitted to heal by second intention.

The clinical differential diagnosis of a scalp nodule includes a pilar cyst, BCC, squamous cell carcinoma, melanoma, cutaneous metastasis, adnexal tumor, atypical fibroxanthoma, and collision tumor. A collision tumor—the association of 2 or more benign or malignant neoplasms—represents a well-known pitfall in making a correct clinical and pathologic diagnosis.2 Many theories have been proposed to explain the pathophysiology of collision tumors. Some authors have speculated that they arise from involvement of related cell types.1 Other theories include induction by cytokines and growth factors secreted from one tumor that provides an ideal environment for proliferation of other cell types, a field cancerization effect of sun-damaged skin, or a coincidence.2

In our case, it is possible that the 2 tumors arose from a nevus sebaceus. One retrospective study of 706 cases of nevus sebaceus (707 specimens) found that 22.5% of cases developed secondary proliferation; of those cases, 18.9% were benign.3 Additionally, in 4.2% of cases of nevus sebaceus, proliferation of 2 or more tumors developed. The most common malignant neoplasm to develop from nevus sebaceus was BCC, followed by squamous cell carcinoma and sebaceous carcinoma. The most common benign neoplasm to develop from nevus sebaceus was trichoblastoma, followed by syringocystadenoma papilliferum.3

Our case highlights the possibility of a sampling error when performing a biopsy of any large neoplasm. Additionally, Mohs surgeons should maintain high clinical suspicion for collision tumors when encountering a large tumor with pathology inconsistent with the original biopsy. Apocrine hidrocystoma should be considered in the differential diagnosis of a large cystic mass of the scalp. Also, it is important to recognize that malignant lesions, such as BCC, can coexist with another benign tumor. Basal cell carcinoma is rare in Black patients, supporting our belief that our patient’s tumors arose from a nevus sebaceus.

It also is important for Mohs surgeons to consider any potential discrepancy between the initial pathology report and Mohs intraoperative pathology that can impact diagnosis, the aggressiveness of the tumors identified, and how such aggressiveness may affect management options.4,5 Some dermatology practices request biopsy slides from patients who are referred for Mohs micrographic surgery for internal review by a dermatopathologist before surgery is performed; however, this protocol requires additional time and adds costs for the overall health care system.4 One study found that internal review of outside biopsy slides resulted in a change in diagnosis in 2.2% of patients (N=3345)—affecting management in 61% of cases in which the diagnosis was changed.4 Another study (N=163) found that the reported aggressiveness of 50.5% of nonmelanoma cases in an initial biopsy report was changed during Mohs micrographic surgery.5 Mohs surgeons should be aware that discrepancies can occur, and if a discrepancy is discovered, the procedure may be paused until the initial biopsy slide is reviewed and further information is collected.

To the Editor:

A collision tumor is the coexistence of 2 discrete tumors in the same neoplasm, possibly comprising a malignant tumor and a benign tumor, and thereby complicating appropriate diagnosis and treatment. We present a case of a basal cell carcinoma (BCC) of the scalp that was later found to be in collision with an apocrine hidrocystoma that might have arisen from a nevus sebaceus. Although rare, BCC can coexist with apocrine hidrocystoma. Jayaprakasam and Rene1 reported a case of a collision tumor containing BCC and hidrocystoma on the eyelid.1 We present a case of a BCC on the scalp that was later found to be in collision with an apocrine hidrocystoma that possibly arose from a nevus sebaceus.

A 92-year-old Black woman with a biopsy-confirmed primary BCC of the left parietal scalp presented for Mohs micrographic surgery. The pathology report from an outside facility was reviewed. The initial diagnosis had been made with 2 punch biopsies from separate areas of the large nodule—one consistent with nodular and pigmented BCC (Figure 1), and the other revealed nodular ulcerated BCC. Physical examination prior to Mohs surgery revealed a mobile, flesh-colored, 6.2×6.0-cm nodule with minimal overlying hair on the left parietal scalp (Figure 2). During stage-I processing by the histopathology laboratory, large cystic structures were encountered; en face frozen sections showed a cystic tumor. Excised tissue was submitted for permanent processing to aid in diagnosis; the initial diagnostic biopsy slides were requested from the outside facility for review.

The initial diagnostic biopsy slides were reviewed and found to be consistent with nodular and pigmented BCC, as previously reported. Findings from hematoxylin and eosin staining of tissue obtained from Mohs sections were consistent with a combined neoplasm comprising BCC (Figure 3A) and apocrine hidrocystoma (Figure 3B). In addition, one section was characterized by acanthosis, papillomatosis, and sebaceous glands—similar to findings that are seen in a nevus sebaceus (Figure 3C).

The BCC was cleared after stage I; the final wound size was 7×6.6 cm. Although benign apocrine hidrocystoma was still evident at the margin, further excision was not performed at the request of the patient and her family. Partial primary wound closure was performed with pulley sutures. A xenograft was placed over the unclosed central portion. The wound was permitted to heal by second intention.

The clinical differential diagnosis of a scalp nodule includes a pilar cyst, BCC, squamous cell carcinoma, melanoma, cutaneous metastasis, adnexal tumor, atypical fibroxanthoma, and collision tumor. A collision tumor—the association of 2 or more benign or malignant neoplasms—represents a well-known pitfall in making a correct clinical and pathologic diagnosis.2 Many theories have been proposed to explain the pathophysiology of collision tumors. Some authors have speculated that they arise from involvement of related cell types.1 Other theories include induction by cytokines and growth factors secreted from one tumor that provides an ideal environment for proliferation of other cell types, a field cancerization effect of sun-damaged skin, or a coincidence.2

In our case, it is possible that the 2 tumors arose from a nevus sebaceus. One retrospective study of 706 cases of nevus sebaceus (707 specimens) found that 22.5% of cases developed secondary proliferation; of those cases, 18.9% were benign.3 Additionally, in 4.2% of cases of nevus sebaceus, proliferation of 2 or more tumors developed. The most common malignant neoplasm to develop from nevus sebaceus was BCC, followed by squamous cell carcinoma and sebaceous carcinoma. The most common benign neoplasm to develop from nevus sebaceus was trichoblastoma, followed by syringocystadenoma papilliferum.3

Our case highlights the possibility of a sampling error when performing a biopsy of any large neoplasm. Additionally, Mohs surgeons should maintain high clinical suspicion for collision tumors when encountering a large tumor with pathology inconsistent with the original biopsy. Apocrine hidrocystoma should be considered in the differential diagnosis of a large cystic mass of the scalp. Also, it is important to recognize that malignant lesions, such as BCC, can coexist with another benign tumor. Basal cell carcinoma is rare in Black patients, supporting our belief that our patient’s tumors arose from a nevus sebaceus.

It also is important for Mohs surgeons to consider any potential discrepancy between the initial pathology report and Mohs intraoperative pathology that can impact diagnosis, the aggressiveness of the tumors identified, and how such aggressiveness may affect management options.4,5 Some dermatology practices request biopsy slides from patients who are referred for Mohs micrographic surgery for internal review by a dermatopathologist before surgery is performed; however, this protocol requires additional time and adds costs for the overall health care system.4 One study found that internal review of outside biopsy slides resulted in a change in diagnosis in 2.2% of patients (N=3345)—affecting management in 61% of cases in which the diagnosis was changed.4 Another study (N=163) found that the reported aggressiveness of 50.5% of nonmelanoma cases in an initial biopsy report was changed during Mohs micrographic surgery.5 Mohs surgeons should be aware that discrepancies can occur, and if a discrepancy is discovered, the procedure may be paused until the initial biopsy slide is reviewed and further information is collected.

- Jayaprakasam A, Rene C. A benign or malignant eyelid lump—can you tell? an unusual collision tumour highlighting the difficulty differentiating a hidrocystoma from a basal cell carcinoma. BMJ Case Reports. 2012;2012:bcr1220115307. doi:10.1136/bcr.12.2011.5307

- Miteva M, Herschthal D, Ricotti C, et al. A rare case of a cutaneous squamomelanocytic tumor: revisiting the histogenesis of combined neoplasms. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:599-603. doi:10.1097/DAD.0b013e3181a88116

- Idriss MH, Elston DM. Secondary neoplasms associated with nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn: a study of 707 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:332-337. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2013.10.004

- Butler ST, Youker SR, Mandrell J, et al. The importance of reviewing pathology specimens before Mohs surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:407-412. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2008.01056.x

- Stiegel E, Lam C, Schowalter M, et al. Correlation between original biopsy pathology and Mohs intraoperative pathology. Dermatol Surg. 2018;44:193-197. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000001276

- Jayaprakasam A, Rene C. A benign or malignant eyelid lump—can you tell? an unusual collision tumour highlighting the difficulty differentiating a hidrocystoma from a basal cell carcinoma. BMJ Case Reports. 2012;2012:bcr1220115307. doi:10.1136/bcr.12.2011.5307

- Miteva M, Herschthal D, Ricotti C, et al. A rare case of a cutaneous squamomelanocytic tumor: revisiting the histogenesis of combined neoplasms. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:599-603. doi:10.1097/DAD.0b013e3181a88116

- Idriss MH, Elston DM. Secondary neoplasms associated with nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn: a study of 707 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:332-337. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2013.10.004

- Butler ST, Youker SR, Mandrell J, et al. The importance of reviewing pathology specimens before Mohs surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:407-412. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2008.01056.x

- Stiegel E, Lam C, Schowalter M, et al. Correlation between original biopsy pathology and Mohs intraoperative pathology. Dermatol Surg. 2018;44:193-197. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000001276

PRACTICE POINTS

- When collision tumors are encountered during Mohs micrographic surgery, review of the initial diagnostic material is recommended.

- Permanent processing of Mohs excisions may be helpful in determining the diagnosis of the occult second tumor diagnosis.

Basal Cell Carcinoma Masquerading as a Dermoid Cyst and Bursitis of the Knee

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most frequently diagnosed skin cancer in the United States. It develops most often on sun-exposed skin, including the face and neck. Although BCCs are slow-growing tumors that rarely metastasize, they can cause notable local destruction with disfigurement if neglected or inadequately treated. Basal cell carcinoma arising on the legs is relatively uncommon.1,2 We present an interesting case of delayed diagnosis of BCC on the left knee due to earlier misdiagnoses of a dermoid cyst and bursitis.

Case Report

A 67-year-old man with no history of skin cancer presented with a painful growing tumor on the left knee of approximately 2 years’ duration. The patient’s primary care physician as well as a general surgeon initially diagnosed it as a dermoid cyst and bursitis. The nodule failed to respond to conservative therapy with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and continued to grow until it began to ulcerate. Concerned about the possibility of septic arthritis, the patient’s primary care physician referred him to the emergency department. He was subsequently sent to the dermatology clinic.

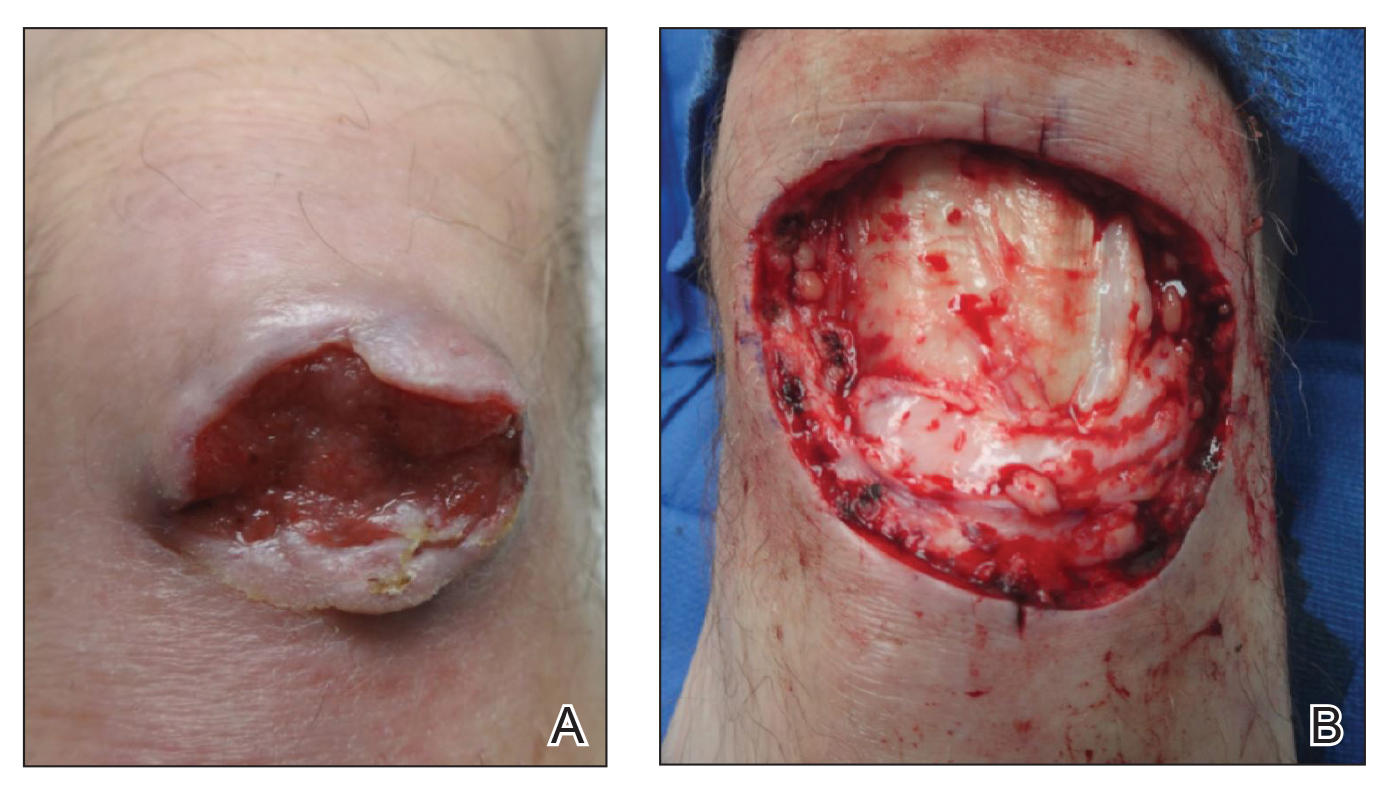

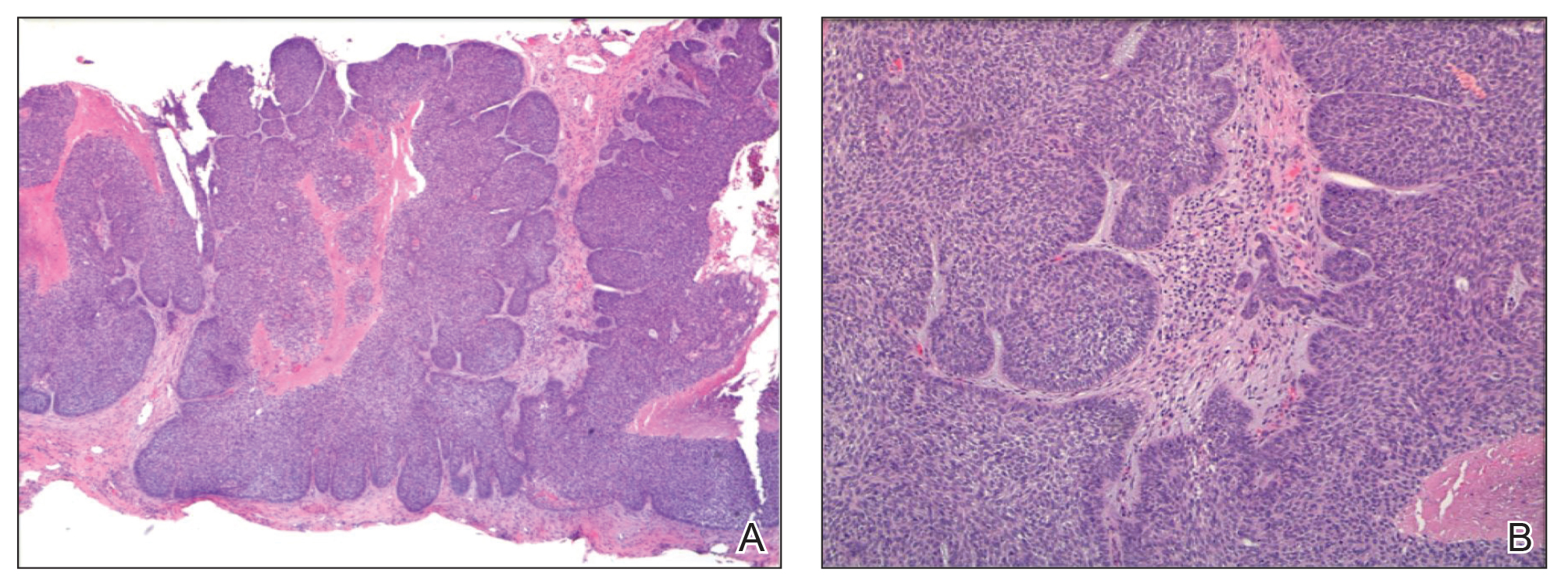

On examination by dermatology, a 6.3×4.4-cm, tender, mobile, ulcerated nodule was noted on the left knee (Figure 1A). No popliteal or inguinal lymph nodes were palpable. Basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, or atypical infection (eg, Leishmania, deep fungal, mycobacterial) was suspected clinically. The patient underwent a diagnostic skin biopsy; hematoxylin and eosin–stained sections revealed lobular proliferation of basaloid cells with peripheral palisading and central tumoral necrosis, consistent with primary BCC (Figure 2).

Given the size of the tumor, the patient was referred for Mohs micrographic surgery and eventual reconstruction by a plastic surgeon. The tumor was cleared after 2 stages of Mohs surgery, with a final wound size of 7.7×5.4 cm (Figure 1B). Plastic surgery later performed a gastrocnemius muscle flap with a split-thickness skin graft (175 cm2) to repair the wound.

Comment

Exposure to UV radiation is the primary causative agent of most BCCs, accounting for the preferential distribution of these tumors on sun-exposed areas of the body. Approximately 80% of BCCs are located on the head and neck, 10% occur on the trunk, and only 8% are found on the lower extremities.1

Giant BCC, the finding in this case, is defined by the American Joint Committee on Cancer as a tumor larger than 5 cm in diameter. Fewer than 1% of all BCCs achieve this size; they appear more commonly on the back where they can go unnoticed.2 Neglect and inadequate treatment of the primary tumor are the most important contributing factors to the size of giant BCCs. Giant BCCs also have more aggressive biologic behavior, with an increased risk for local invasion and metastasis.3 In this case, the lesion was larger than 5 cm in diameter and occurred on the lower extremity rather than on the trunk.

This case is unusual because delayed diagnosis of BCC was the result of misdiagnoses of a dermoid cyst and bursitis, with a diagnostic skin biopsy demonstrating BCC almost 2 years later. It should be emphasized that early diagnosis and treatment could prevent tumor expansion. Physicians should have a high degree of suspicion for BCC, especially when a dermoid cyst and knee bursitis fail to respond to conservative management.

- Pearson G, King LE, Boyd AS. Basal cell carcinoma of the lower extremities. Int J Dermatol. 1999;38:852-854.

- Arnaiz J, Gallardo E, Piedra T, et al. Giant basal cell carcinoma on the lower leg: MRI findings. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2007;60:1167-1168.

- Randle HW. Giant basal cell carcinoma [letter]. Int J Dermatol. 1996;35:222-223.

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most frequently diagnosed skin cancer in the United States. It develops most often on sun-exposed skin, including the face and neck. Although BCCs are slow-growing tumors that rarely metastasize, they can cause notable local destruction with disfigurement if neglected or inadequately treated. Basal cell carcinoma arising on the legs is relatively uncommon.1,2 We present an interesting case of delayed diagnosis of BCC on the left knee due to earlier misdiagnoses of a dermoid cyst and bursitis.

Case Report

A 67-year-old man with no history of skin cancer presented with a painful growing tumor on the left knee of approximately 2 years’ duration. The patient’s primary care physician as well as a general surgeon initially diagnosed it as a dermoid cyst and bursitis. The nodule failed to respond to conservative therapy with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and continued to grow until it began to ulcerate. Concerned about the possibility of septic arthritis, the patient’s primary care physician referred him to the emergency department. He was subsequently sent to the dermatology clinic.

On examination by dermatology, a 6.3×4.4-cm, tender, mobile, ulcerated nodule was noted on the left knee (Figure 1A). No popliteal or inguinal lymph nodes were palpable. Basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, or atypical infection (eg, Leishmania, deep fungal, mycobacterial) was suspected clinically. The patient underwent a diagnostic skin biopsy; hematoxylin and eosin–stained sections revealed lobular proliferation of basaloid cells with peripheral palisading and central tumoral necrosis, consistent with primary BCC (Figure 2).

Given the size of the tumor, the patient was referred for Mohs micrographic surgery and eventual reconstruction by a plastic surgeon. The tumor was cleared after 2 stages of Mohs surgery, with a final wound size of 7.7×5.4 cm (Figure 1B). Plastic surgery later performed a gastrocnemius muscle flap with a split-thickness skin graft (175 cm2) to repair the wound.

Comment

Exposure to UV radiation is the primary causative agent of most BCCs, accounting for the preferential distribution of these tumors on sun-exposed areas of the body. Approximately 80% of BCCs are located on the head and neck, 10% occur on the trunk, and only 8% are found on the lower extremities.1

Giant BCC, the finding in this case, is defined by the American Joint Committee on Cancer as a tumor larger than 5 cm in diameter. Fewer than 1% of all BCCs achieve this size; they appear more commonly on the back where they can go unnoticed.2 Neglect and inadequate treatment of the primary tumor are the most important contributing factors to the size of giant BCCs. Giant BCCs also have more aggressive biologic behavior, with an increased risk for local invasion and metastasis.3 In this case, the lesion was larger than 5 cm in diameter and occurred on the lower extremity rather than on the trunk.

This case is unusual because delayed diagnosis of BCC was the result of misdiagnoses of a dermoid cyst and bursitis, with a diagnostic skin biopsy demonstrating BCC almost 2 years later. It should be emphasized that early diagnosis and treatment could prevent tumor expansion. Physicians should have a high degree of suspicion for BCC, especially when a dermoid cyst and knee bursitis fail to respond to conservative management.

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most frequently diagnosed skin cancer in the United States. It develops most often on sun-exposed skin, including the face and neck. Although BCCs are slow-growing tumors that rarely metastasize, they can cause notable local destruction with disfigurement if neglected or inadequately treated. Basal cell carcinoma arising on the legs is relatively uncommon.1,2 We present an interesting case of delayed diagnosis of BCC on the left knee due to earlier misdiagnoses of a dermoid cyst and bursitis.

Case Report

A 67-year-old man with no history of skin cancer presented with a painful growing tumor on the left knee of approximately 2 years’ duration. The patient’s primary care physician as well as a general surgeon initially diagnosed it as a dermoid cyst and bursitis. The nodule failed to respond to conservative therapy with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and continued to grow until it began to ulcerate. Concerned about the possibility of septic arthritis, the patient’s primary care physician referred him to the emergency department. He was subsequently sent to the dermatology clinic.

On examination by dermatology, a 6.3×4.4-cm, tender, mobile, ulcerated nodule was noted on the left knee (Figure 1A). No popliteal or inguinal lymph nodes were palpable. Basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, or atypical infection (eg, Leishmania, deep fungal, mycobacterial) was suspected clinically. The patient underwent a diagnostic skin biopsy; hematoxylin and eosin–stained sections revealed lobular proliferation of basaloid cells with peripheral palisading and central tumoral necrosis, consistent with primary BCC (Figure 2).

Given the size of the tumor, the patient was referred for Mohs micrographic surgery and eventual reconstruction by a plastic surgeon. The tumor was cleared after 2 stages of Mohs surgery, with a final wound size of 7.7×5.4 cm (Figure 1B). Plastic surgery later performed a gastrocnemius muscle flap with a split-thickness skin graft (175 cm2) to repair the wound.

Comment

Exposure to UV radiation is the primary causative agent of most BCCs, accounting for the preferential distribution of these tumors on sun-exposed areas of the body. Approximately 80% of BCCs are located on the head and neck, 10% occur on the trunk, and only 8% are found on the lower extremities.1

Giant BCC, the finding in this case, is defined by the American Joint Committee on Cancer as a tumor larger than 5 cm in diameter. Fewer than 1% of all BCCs achieve this size; they appear more commonly on the back where they can go unnoticed.2 Neglect and inadequate treatment of the primary tumor are the most important contributing factors to the size of giant BCCs. Giant BCCs also have more aggressive biologic behavior, with an increased risk for local invasion and metastasis.3 In this case, the lesion was larger than 5 cm in diameter and occurred on the lower extremity rather than on the trunk.

This case is unusual because delayed diagnosis of BCC was the result of misdiagnoses of a dermoid cyst and bursitis, with a diagnostic skin biopsy demonstrating BCC almost 2 years later. It should be emphasized that early diagnosis and treatment could prevent tumor expansion. Physicians should have a high degree of suspicion for BCC, especially when a dermoid cyst and knee bursitis fail to respond to conservative management.

- Pearson G, King LE, Boyd AS. Basal cell carcinoma of the lower extremities. Int J Dermatol. 1999;38:852-854.

- Arnaiz J, Gallardo E, Piedra T, et al. Giant basal cell carcinoma on the lower leg: MRI findings. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2007;60:1167-1168.

- Randle HW. Giant basal cell carcinoma [letter]. Int J Dermatol. 1996;35:222-223.

- Pearson G, King LE, Boyd AS. Basal cell carcinoma of the lower extremities. Int J Dermatol. 1999;38:852-854.

- Arnaiz J, Gallardo E, Piedra T, et al. Giant basal cell carcinoma on the lower leg: MRI findings. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2007;60:1167-1168.

- Randle HW. Giant basal cell carcinoma [letter]. Int J Dermatol. 1996;35:222-223.

Practice Points

- This case highlights an unusual presentation of basal cell carcinoma masquerading as bursitis.

- Clinicians should be aware of confirmation bias, especially when multiple physicians and specialists are involved in a case.

- When the initial clinical impression is not corroborated by objective data or the condition is not responding to conventional therapy, it is important for clinicians to revisit the possibility of an inaccurate diagnosis.