User login

Simplify Postoperative Self-removal of Bandages for Isolated Patients With Limited Range of Motion Using Pull Tabs

Practice Gap

A male patient presented with 2 concerning lesions, which histopathology revealed were invasive squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) on the right medial chest and SCC in situ on the right upper scapular region. Both were treated with wide local excision; margins were clear in our office the same day.

This case highlighted a practice gap in postoperative care. Two factors posed a challenge to proper postoperative wound care for our patient:

• Because of the high risk of transmission of SARS-CoV-2, the patient hoped to limit exposure by avoiding an office visit to remove the bandage.

• The patient did not have someone at home to serve as an immediate support system, which made it impossible for him to rely on others for postoperative wound care.

Previously, the patient had to ask a friend to remove a bandage for melanoma in situ on the inner aspect of the left upper arm. Therefore, after this procedure, the patient asked if the bandage could be fashioned in a manner that would allow him to remove it without assistance (Figure 1).

Technique

In constructing a bandage that is easier to remove, some necessary pressure that is provided by the bandage often is sacrificed by making it looser. Considering that our patient had moderate bleeding during the procedure—in part because he took low-dose aspirin (81 mg/d)—it was important to maintain firm pressure under the bandage postoperatively to help prevent untoward bleeding. Furthermore, because of the location of the treated site and the patient’s limited range of motion, it was not feasible for him to reach the area on the scapula and remove the bandage.1

For easy self-removal, we designed a bandage with a pull tab that was within the patient’s reach. Suitable materials for the pull tab bandage included surgical tape, bandaging tape with adequate stretch, sterile nonadhesive gauze, fenestrated surgical gauze, and a topical emollient such as petroleum jelly or antibacterial ointment.

To clean the site and decrease the amount of oil that would reduce the effectiveness of the adhesive, the wound was prepared with 70% alcohol. The site was then treated with petroleum jelly.

Next, we designed 2 pull tab bandage prototypes that allowed easy self-removal. For both prototypes, sterile nonadhesive gauze was applied to the wound along with folded and fenestrated gauze, which provided pressure. We used prototype #1 in our patient, and prototype #2 was demonstrated as an option.

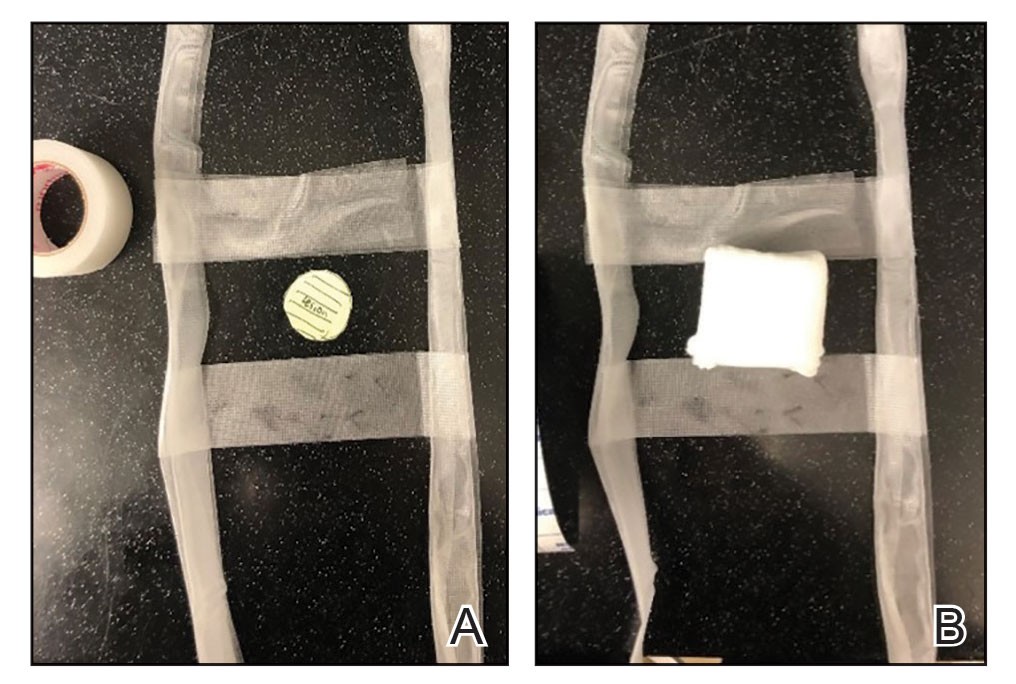

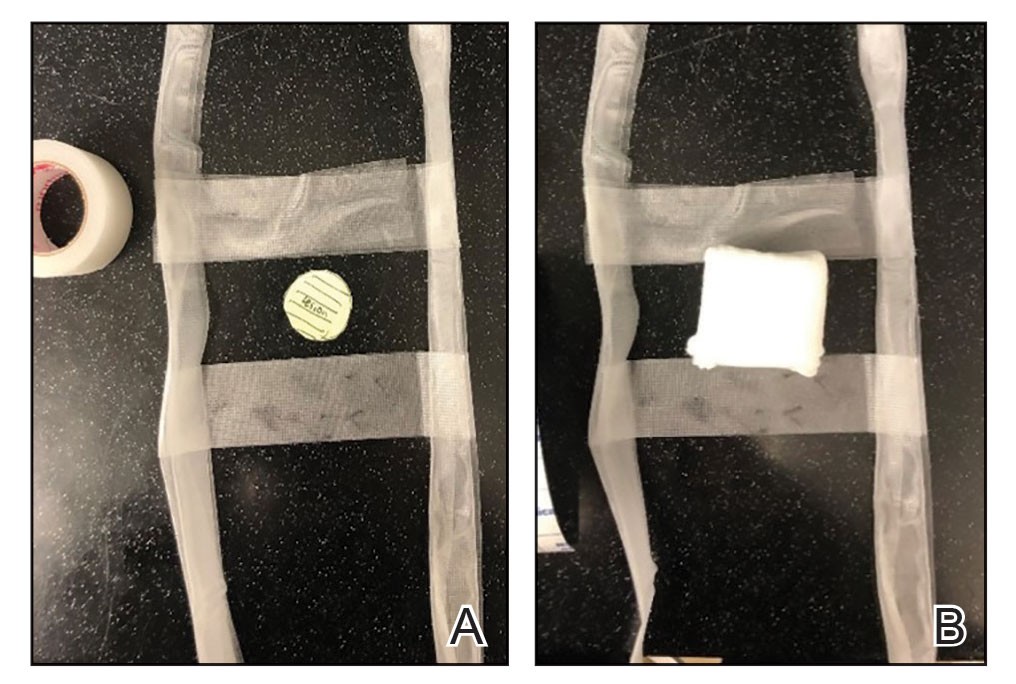

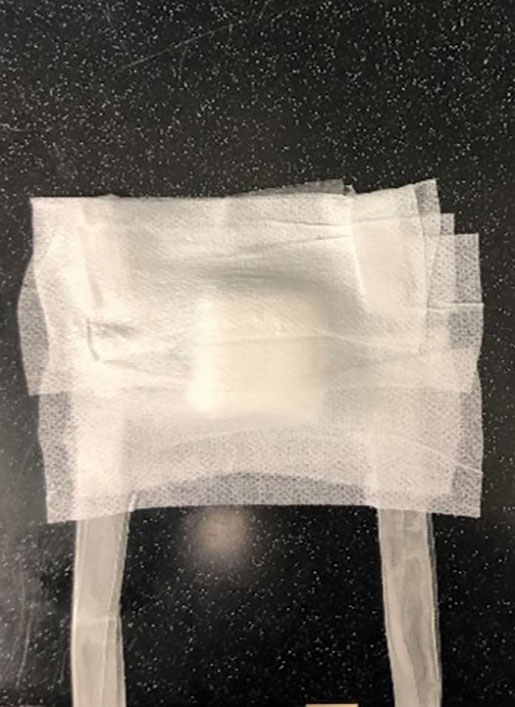

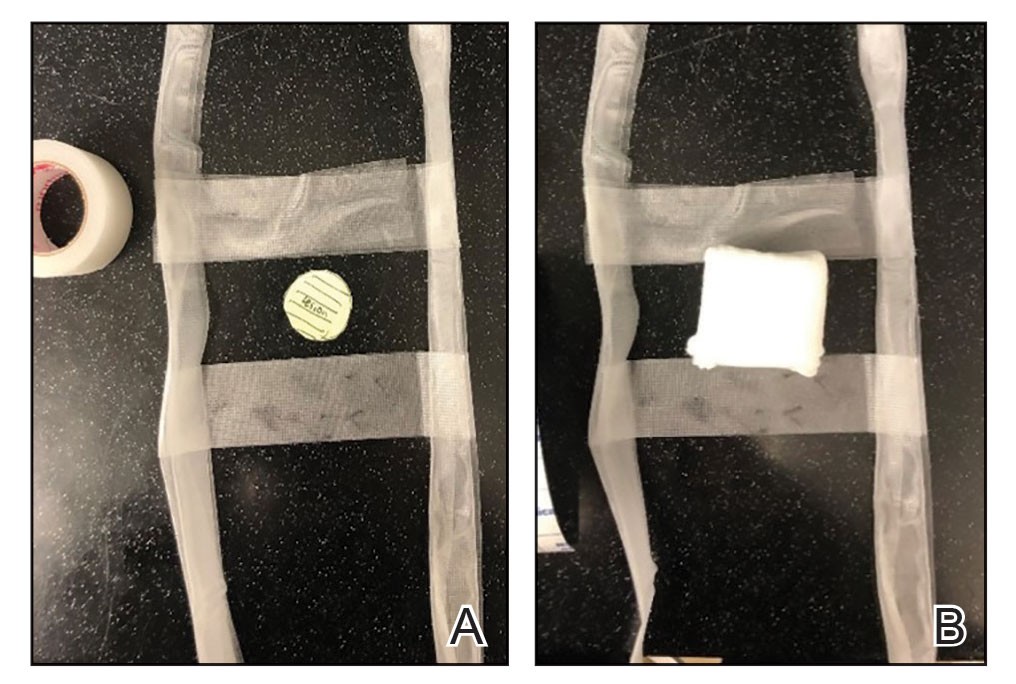

Prototype #1—We created 2 tabs—each 2-feet long—using bandaging tape that was folded on itself once horizontally (Figure 2). The tabs were aligned on either side of the wound, the tops of which sat approximately 2 inches above the top of the first layer of adhesive bandage. An initial layer of adhesive surgical dressing was applied to cover the wound; 1 inch of the dressing was left exposed on the top of each tab. In addition, there were 2 “feet” running on the bottom.

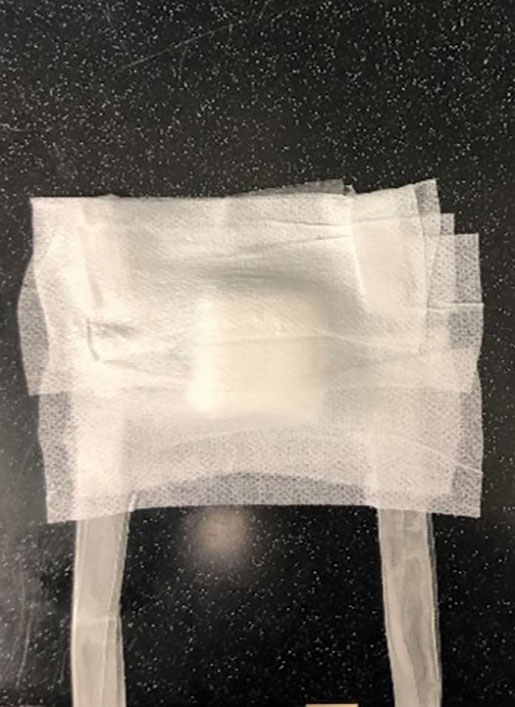

The tops of the tabs were folded back over the adhesive tape, creating a type of “hook.” An additional final layer of adhesive tape was applied to ensure adequate pressure on the surgical site.

The patient was instructed to remove the bandage 2 days after the procedure. The outcome was qualified through a 3-day postoperative telephone call. The patient was asked about postoperative pain and his level of satisfaction with treatment. He was asked if he had any changes such as bleeding, swelling, signs of infection, or increased pain in the days after surgery or perceived postoperative complications, such as irritation. We asked the patient about the relative ease of removing the bandage and if removal was painful. He reported that the bandage was easy to remove, and that doing so was not painful; furthermore, he did not have problems with the bandage or healing and did not experience any medical changes. He found the bandage to be comfortable. The patient stated that the hanging feet of the prototype #1 bandage were not bothersome and were sturdy for the time that the bandage was on.

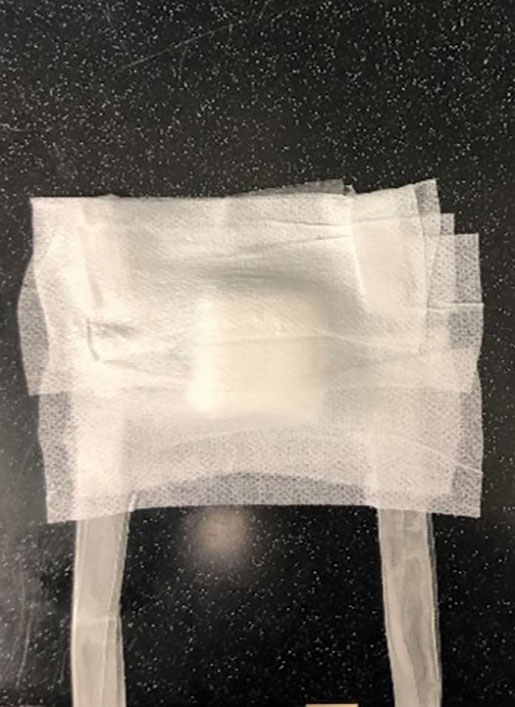

Prototype #2—We prepared a bandage using surgical packing as the tab (Figure 3). The packing was slowly placed around the site, which was already covered with nonadhesive gauze and fenestrated surgical gauze, with adequate spacing between each loop (for a total of 3 loops), 1 of which crossed over the third loop so that the adhesive bandaging tape could be removed easily. This allowed for a single tab that could be removed by a single pull. A final layer of adhesive tape was applied to ensure adequate pressure, similar to prototype #1. The same postoperative protocol was employed to provide a consistent standard of care. We recommend use of this prototype when surgical tape is not available, and surgical packing can be used as a substitute.

Practice Implications

Patients have a better appreciation for avoiding excess visits to medical offices due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The risk for exposure to SARS-CoV-2 infection is greater when patients who lack a support system must return to the office for aftercare or to have a bandage removed. Although protection offered by the COVID-19 vaccine alleviates concern, many patients have realized the benefits of only visiting medical offices in person when necessary.

The concept of pull tab bandages that can be removed by the patient at home has other applications. For example, patients who travel a long distance to see their physician will benefit from easier aftercare and avoid additional follow-up visits when provided with a self-removable bandage.

- Stathokostas, L, McDonald MW, Little RMD, et al. Flexibility of older adults aged 55-86 years and the influence of physical activity. J Aging Res. 2013;2013:1-8. doi:10.1155/2013/743843

Practice Gap

A male patient presented with 2 concerning lesions, which histopathology revealed were invasive squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) on the right medial chest and SCC in situ on the right upper scapular region. Both were treated with wide local excision; margins were clear in our office the same day.

This case highlighted a practice gap in postoperative care. Two factors posed a challenge to proper postoperative wound care for our patient:

• Because of the high risk of transmission of SARS-CoV-2, the patient hoped to limit exposure by avoiding an office visit to remove the bandage.

• The patient did not have someone at home to serve as an immediate support system, which made it impossible for him to rely on others for postoperative wound care.

Previously, the patient had to ask a friend to remove a bandage for melanoma in situ on the inner aspect of the left upper arm. Therefore, after this procedure, the patient asked if the bandage could be fashioned in a manner that would allow him to remove it without assistance (Figure 1).

Technique

In constructing a bandage that is easier to remove, some necessary pressure that is provided by the bandage often is sacrificed by making it looser. Considering that our patient had moderate bleeding during the procedure—in part because he took low-dose aspirin (81 mg/d)—it was important to maintain firm pressure under the bandage postoperatively to help prevent untoward bleeding. Furthermore, because of the location of the treated site and the patient’s limited range of motion, it was not feasible for him to reach the area on the scapula and remove the bandage.1

For easy self-removal, we designed a bandage with a pull tab that was within the patient’s reach. Suitable materials for the pull tab bandage included surgical tape, bandaging tape with adequate stretch, sterile nonadhesive gauze, fenestrated surgical gauze, and a topical emollient such as petroleum jelly or antibacterial ointment.

To clean the site and decrease the amount of oil that would reduce the effectiveness of the adhesive, the wound was prepared with 70% alcohol. The site was then treated with petroleum jelly.

Next, we designed 2 pull tab bandage prototypes that allowed easy self-removal. For both prototypes, sterile nonadhesive gauze was applied to the wound along with folded and fenestrated gauze, which provided pressure. We used prototype #1 in our patient, and prototype #2 was demonstrated as an option.

Prototype #1—We created 2 tabs—each 2-feet long—using bandaging tape that was folded on itself once horizontally (Figure 2). The tabs were aligned on either side of the wound, the tops of which sat approximately 2 inches above the top of the first layer of adhesive bandage. An initial layer of adhesive surgical dressing was applied to cover the wound; 1 inch of the dressing was left exposed on the top of each tab. In addition, there were 2 “feet” running on the bottom.

The tops of the tabs were folded back over the adhesive tape, creating a type of “hook.” An additional final layer of adhesive tape was applied to ensure adequate pressure on the surgical site.

The patient was instructed to remove the bandage 2 days after the procedure. The outcome was qualified through a 3-day postoperative telephone call. The patient was asked about postoperative pain and his level of satisfaction with treatment. He was asked if he had any changes such as bleeding, swelling, signs of infection, or increased pain in the days after surgery or perceived postoperative complications, such as irritation. We asked the patient about the relative ease of removing the bandage and if removal was painful. He reported that the bandage was easy to remove, and that doing so was not painful; furthermore, he did not have problems with the bandage or healing and did not experience any medical changes. He found the bandage to be comfortable. The patient stated that the hanging feet of the prototype #1 bandage were not bothersome and were sturdy for the time that the bandage was on.

Prototype #2—We prepared a bandage using surgical packing as the tab (Figure 3). The packing was slowly placed around the site, which was already covered with nonadhesive gauze and fenestrated surgical gauze, with adequate spacing between each loop (for a total of 3 loops), 1 of which crossed over the third loop so that the adhesive bandaging tape could be removed easily. This allowed for a single tab that could be removed by a single pull. A final layer of adhesive tape was applied to ensure adequate pressure, similar to prototype #1. The same postoperative protocol was employed to provide a consistent standard of care. We recommend use of this prototype when surgical tape is not available, and surgical packing can be used as a substitute.

Practice Implications

Patients have a better appreciation for avoiding excess visits to medical offices due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The risk for exposure to SARS-CoV-2 infection is greater when patients who lack a support system must return to the office for aftercare or to have a bandage removed. Although protection offered by the COVID-19 vaccine alleviates concern, many patients have realized the benefits of only visiting medical offices in person when necessary.

The concept of pull tab bandages that can be removed by the patient at home has other applications. For example, patients who travel a long distance to see their physician will benefit from easier aftercare and avoid additional follow-up visits when provided with a self-removable bandage.

Practice Gap

A male patient presented with 2 concerning lesions, which histopathology revealed were invasive squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) on the right medial chest and SCC in situ on the right upper scapular region. Both were treated with wide local excision; margins were clear in our office the same day.

This case highlighted a practice gap in postoperative care. Two factors posed a challenge to proper postoperative wound care for our patient:

• Because of the high risk of transmission of SARS-CoV-2, the patient hoped to limit exposure by avoiding an office visit to remove the bandage.

• The patient did not have someone at home to serve as an immediate support system, which made it impossible for him to rely on others for postoperative wound care.

Previously, the patient had to ask a friend to remove a bandage for melanoma in situ on the inner aspect of the left upper arm. Therefore, after this procedure, the patient asked if the bandage could be fashioned in a manner that would allow him to remove it without assistance (Figure 1).

Technique

In constructing a bandage that is easier to remove, some necessary pressure that is provided by the bandage often is sacrificed by making it looser. Considering that our patient had moderate bleeding during the procedure—in part because he took low-dose aspirin (81 mg/d)—it was important to maintain firm pressure under the bandage postoperatively to help prevent untoward bleeding. Furthermore, because of the location of the treated site and the patient’s limited range of motion, it was not feasible for him to reach the area on the scapula and remove the bandage.1

For easy self-removal, we designed a bandage with a pull tab that was within the patient’s reach. Suitable materials for the pull tab bandage included surgical tape, bandaging tape with adequate stretch, sterile nonadhesive gauze, fenestrated surgical gauze, and a topical emollient such as petroleum jelly or antibacterial ointment.

To clean the site and decrease the amount of oil that would reduce the effectiveness of the adhesive, the wound was prepared with 70% alcohol. The site was then treated with petroleum jelly.

Next, we designed 2 pull tab bandage prototypes that allowed easy self-removal. For both prototypes, sterile nonadhesive gauze was applied to the wound along with folded and fenestrated gauze, which provided pressure. We used prototype #1 in our patient, and prototype #2 was demonstrated as an option.

Prototype #1—We created 2 tabs—each 2-feet long—using bandaging tape that was folded on itself once horizontally (Figure 2). The tabs were aligned on either side of the wound, the tops of which sat approximately 2 inches above the top of the first layer of adhesive bandage. An initial layer of adhesive surgical dressing was applied to cover the wound; 1 inch of the dressing was left exposed on the top of each tab. In addition, there were 2 “feet” running on the bottom.

The tops of the tabs were folded back over the adhesive tape, creating a type of “hook.” An additional final layer of adhesive tape was applied to ensure adequate pressure on the surgical site.

The patient was instructed to remove the bandage 2 days after the procedure. The outcome was qualified through a 3-day postoperative telephone call. The patient was asked about postoperative pain and his level of satisfaction with treatment. He was asked if he had any changes such as bleeding, swelling, signs of infection, or increased pain in the days after surgery or perceived postoperative complications, such as irritation. We asked the patient about the relative ease of removing the bandage and if removal was painful. He reported that the bandage was easy to remove, and that doing so was not painful; furthermore, he did not have problems with the bandage or healing and did not experience any medical changes. He found the bandage to be comfortable. The patient stated that the hanging feet of the prototype #1 bandage were not bothersome and were sturdy for the time that the bandage was on.

Prototype #2—We prepared a bandage using surgical packing as the tab (Figure 3). The packing was slowly placed around the site, which was already covered with nonadhesive gauze and fenestrated surgical gauze, with adequate spacing between each loop (for a total of 3 loops), 1 of which crossed over the third loop so that the adhesive bandaging tape could be removed easily. This allowed for a single tab that could be removed by a single pull. A final layer of adhesive tape was applied to ensure adequate pressure, similar to prototype #1. The same postoperative protocol was employed to provide a consistent standard of care. We recommend use of this prototype when surgical tape is not available, and surgical packing can be used as a substitute.

Practice Implications

Patients have a better appreciation for avoiding excess visits to medical offices due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The risk for exposure to SARS-CoV-2 infection is greater when patients who lack a support system must return to the office for aftercare or to have a bandage removed. Although protection offered by the COVID-19 vaccine alleviates concern, many patients have realized the benefits of only visiting medical offices in person when necessary.

The concept of pull tab bandages that can be removed by the patient at home has other applications. For example, patients who travel a long distance to see their physician will benefit from easier aftercare and avoid additional follow-up visits when provided with a self-removable bandage.

- Stathokostas, L, McDonald MW, Little RMD, et al. Flexibility of older adults aged 55-86 years and the influence of physical activity. J Aging Res. 2013;2013:1-8. doi:10.1155/2013/743843

- Stathokostas, L, McDonald MW, Little RMD, et al. Flexibility of older adults aged 55-86 years and the influence of physical activity. J Aging Res. 2013;2013:1-8. doi:10.1155/2013/743843