User login

Defending access to reproductive health care

The 1973 Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) decision in Roe v Wade was a landmark ruling,1 establishing that the United States Constitution provides a fundamental “right to privacy,” protecting pregnant people’s freedom to access all available reproductive health care options. Recognizing that the right to abortion was not absolute, the majority of justices supported a trimester system. In the first trimester, decisions about abortion care are fully controlled by patients and clinicians, and no government could place restrictions on access to abortion. In the second trimester, SCOTUS ruled that states may choose to regulate abortion to protect maternal health. (As an example of such state restrictions, in Massachusetts, for many years, but no longer, the state required that abortions occur in a hospital when the patient was between 18 and 24 weeks’ gestation in order to facilitate comprehensive emergency care for complications.) Beginning in the third trimester, a point at which a fetus could be viable, the Court ruled that a government could prohibit abortion except when an abortion was necessary to protect the life or health of the pregnant person. In 1992, the SCOTUS decision in Planned Parenthood v Casey2 rejected the trimester system, reaffirming the right to an abortion before fetal viability, and adopting a new standard that states may not create an undue burden on a person seeking an abortion b

If, as anticipated, the 2022 SCOTUS decision in Dobbs v Jackson Women’s Health Organization3 overturns the precedents set in Roe v Wade and Planned Parenthood v Casey, decisions on abortion law will be relegated to elected legislators and state courts.4 It is expected that at least 26 state legislatures and governors will enact stringent new restrictions on access to abortion. This cataclysmic reversal of judicial opinion creates a historic challenge to obstetrician-gynecologists and their patients and could threaten access to other vital reproductive services beyond abortion, like contraception. We will be fighting, state by state, for people’s right to access all available reproductive health procedures. This will also significantly affect the ability for providers in women’s reproductive health to obtain appropriate and necessary education and training in a critical skills. If access to safe abortion is restricted, we fear patients may be forced to consider unsafe abortion, raising the specter of a return to the 1960s, when an epidemic of unsafe abortion caused countless injuries and deaths.5,6

How do we best prepare for these challenges?

- We will need to be flexible and continually evolve our clinical practices to be adherent with state and local legislation and regulation.

- To reduce unintended pregnancies, we need to strengthen our efforts to ensure that every patient has ready access to all available contraceptive options with no out-of-pocket cost.

- When a contraceptive is desired, we will focus on educating people about effectiveness, and offering them highly reliable contraception, such as the implant or intrauterine devices.

- We need to ensure timely access to abortion if state-based laws permit abortion before 6 or 7 weeks’ gestation. Providing medication abortion without an in-person visit using a telehealth option would be one option to expand rapid access to early first trimester abortion.

- Clinicians in states with access to abortion services will need to collaborate with colleagues in states with restrictions on abortion services to improve patient access across state borders.

On a national level, advancing our effective advocacy in Congress may lead to national legislation passed and signed by the President. This could supersede most state laws prohibiting access to comprehensive women’s reproductive health and create a unified, national approach to abortion care, allowing for the appropriate training of all obstetrician-gynecologists. We will also need to develop teams in every state capable of advocating for laws that ensure access to all reproductive health care options. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists has leaders trained and tasked with legislative advocacy in every state.7 This network will be a foundation upon which to build additional advocacy efforts.

As women’s health care professionals, our responsibility to our patients, is to work to ensure universal access to safe and effective comprehensive reproductive options, and to ensure that our workforce is prepared to meet the needs of our patients by defending the patient-clinician relationship. Abortion care saves lives of pregnant patients and reduces maternal morbidity.8 Access to safe abortion care as part of comprehensive reproductive services is an important component of health care. ●

- Roe v Wade, 410 U.S. 113 (1973).

- Planned Parenthood v Casey, 505 U.S. 833 (1992).

- Dobbs v Jackson Women’s Health Organization, 19-1392. https://www.supremecourt.gov/search .aspx?filename=/docket/docketfiles/html /public/19-1392.html. Accessed May 18, 2022.

- Gerstein J, Ward A. Supreme Court has voted to overturn abortion rights, draft opinion shows. Politico. May 5, 2022. Updated May 3, 2022.

- Gold RB. Lessons from before Roe: will past be prologue? Guttmacher Institute. March 1, 2003. https://www.guttmacher.org/gpr/2003/03 /lessons-roe-will-past-be-prologue. Accessed May 18, 2022.

- Edelin KC. Broken Justice: A True Story of Race, Sex and Revenge in a Boston Courtroom. Pond View Press; 2007.

- The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Get involved in your state. ACOG web site. https://www.acog.org/advocacy /get-involved/get-involved-in-your-state. Accessed May 18, 2022.

- Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Improving Birth Outcomes. Bale JR, Stoll BJ, Lucas AO, eds. Reducing maternal mortality and morbidity. In: Improving Birth Outcomes: Meeting the Challenge in the Developing World. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (US); 2003.

The 1973 Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) decision in Roe v Wade was a landmark ruling,1 establishing that the United States Constitution provides a fundamental “right to privacy,” protecting pregnant people’s freedom to access all available reproductive health care options. Recognizing that the right to abortion was not absolute, the majority of justices supported a trimester system. In the first trimester, decisions about abortion care are fully controlled by patients and clinicians, and no government could place restrictions on access to abortion. In the second trimester, SCOTUS ruled that states may choose to regulate abortion to protect maternal health. (As an example of such state restrictions, in Massachusetts, for many years, but no longer, the state required that abortions occur in a hospital when the patient was between 18 and 24 weeks’ gestation in order to facilitate comprehensive emergency care for complications.) Beginning in the third trimester, a point at which a fetus could be viable, the Court ruled that a government could prohibit abortion except when an abortion was necessary to protect the life or health of the pregnant person. In 1992, the SCOTUS decision in Planned Parenthood v Casey2 rejected the trimester system, reaffirming the right to an abortion before fetal viability, and adopting a new standard that states may not create an undue burden on a person seeking an abortion b

If, as anticipated, the 2022 SCOTUS decision in Dobbs v Jackson Women’s Health Organization3 overturns the precedents set in Roe v Wade and Planned Parenthood v Casey, decisions on abortion law will be relegated to elected legislators and state courts.4 It is expected that at least 26 state legislatures and governors will enact stringent new restrictions on access to abortion. This cataclysmic reversal of judicial opinion creates a historic challenge to obstetrician-gynecologists and their patients and could threaten access to other vital reproductive services beyond abortion, like contraception. We will be fighting, state by state, for people’s right to access all available reproductive health procedures. This will also significantly affect the ability for providers in women’s reproductive health to obtain appropriate and necessary education and training in a critical skills. If access to safe abortion is restricted, we fear patients may be forced to consider unsafe abortion, raising the specter of a return to the 1960s, when an epidemic of unsafe abortion caused countless injuries and deaths.5,6

How do we best prepare for these challenges?

- We will need to be flexible and continually evolve our clinical practices to be adherent with state and local legislation and regulation.

- To reduce unintended pregnancies, we need to strengthen our efforts to ensure that every patient has ready access to all available contraceptive options with no out-of-pocket cost.

- When a contraceptive is desired, we will focus on educating people about effectiveness, and offering them highly reliable contraception, such as the implant or intrauterine devices.

- We need to ensure timely access to abortion if state-based laws permit abortion before 6 or 7 weeks’ gestation. Providing medication abortion without an in-person visit using a telehealth option would be one option to expand rapid access to early first trimester abortion.

- Clinicians in states with access to abortion services will need to collaborate with colleagues in states with restrictions on abortion services to improve patient access across state borders.

On a national level, advancing our effective advocacy in Congress may lead to national legislation passed and signed by the President. This could supersede most state laws prohibiting access to comprehensive women’s reproductive health and create a unified, national approach to abortion care, allowing for the appropriate training of all obstetrician-gynecologists. We will also need to develop teams in every state capable of advocating for laws that ensure access to all reproductive health care options. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists has leaders trained and tasked with legislative advocacy in every state.7 This network will be a foundation upon which to build additional advocacy efforts.

As women’s health care professionals, our responsibility to our patients, is to work to ensure universal access to safe and effective comprehensive reproductive options, and to ensure that our workforce is prepared to meet the needs of our patients by defending the patient-clinician relationship. Abortion care saves lives of pregnant patients and reduces maternal morbidity.8 Access to safe abortion care as part of comprehensive reproductive services is an important component of health care. ●

The 1973 Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) decision in Roe v Wade was a landmark ruling,1 establishing that the United States Constitution provides a fundamental “right to privacy,” protecting pregnant people’s freedom to access all available reproductive health care options. Recognizing that the right to abortion was not absolute, the majority of justices supported a trimester system. In the first trimester, decisions about abortion care are fully controlled by patients and clinicians, and no government could place restrictions on access to abortion. In the second trimester, SCOTUS ruled that states may choose to regulate abortion to protect maternal health. (As an example of such state restrictions, in Massachusetts, for many years, but no longer, the state required that abortions occur in a hospital when the patient was between 18 and 24 weeks’ gestation in order to facilitate comprehensive emergency care for complications.) Beginning in the third trimester, a point at which a fetus could be viable, the Court ruled that a government could prohibit abortion except when an abortion was necessary to protect the life or health of the pregnant person. In 1992, the SCOTUS decision in Planned Parenthood v Casey2 rejected the trimester system, reaffirming the right to an abortion before fetal viability, and adopting a new standard that states may not create an undue burden on a person seeking an abortion b

If, as anticipated, the 2022 SCOTUS decision in Dobbs v Jackson Women’s Health Organization3 overturns the precedents set in Roe v Wade and Planned Parenthood v Casey, decisions on abortion law will be relegated to elected legislators and state courts.4 It is expected that at least 26 state legislatures and governors will enact stringent new restrictions on access to abortion. This cataclysmic reversal of judicial opinion creates a historic challenge to obstetrician-gynecologists and their patients and could threaten access to other vital reproductive services beyond abortion, like contraception. We will be fighting, state by state, for people’s right to access all available reproductive health procedures. This will also significantly affect the ability for providers in women’s reproductive health to obtain appropriate and necessary education and training in a critical skills. If access to safe abortion is restricted, we fear patients may be forced to consider unsafe abortion, raising the specter of a return to the 1960s, when an epidemic of unsafe abortion caused countless injuries and deaths.5,6

How do we best prepare for these challenges?

- We will need to be flexible and continually evolve our clinical practices to be adherent with state and local legislation and regulation.

- To reduce unintended pregnancies, we need to strengthen our efforts to ensure that every patient has ready access to all available contraceptive options with no out-of-pocket cost.

- When a contraceptive is desired, we will focus on educating people about effectiveness, and offering them highly reliable contraception, such as the implant or intrauterine devices.

- We need to ensure timely access to abortion if state-based laws permit abortion before 6 or 7 weeks’ gestation. Providing medication abortion without an in-person visit using a telehealth option would be one option to expand rapid access to early first trimester abortion.

- Clinicians in states with access to abortion services will need to collaborate with colleagues in states with restrictions on abortion services to improve patient access across state borders.

On a national level, advancing our effective advocacy in Congress may lead to national legislation passed and signed by the President. This could supersede most state laws prohibiting access to comprehensive women’s reproductive health and create a unified, national approach to abortion care, allowing for the appropriate training of all obstetrician-gynecologists. We will also need to develop teams in every state capable of advocating for laws that ensure access to all reproductive health care options. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists has leaders trained and tasked with legislative advocacy in every state.7 This network will be a foundation upon which to build additional advocacy efforts.

As women’s health care professionals, our responsibility to our patients, is to work to ensure universal access to safe and effective comprehensive reproductive options, and to ensure that our workforce is prepared to meet the needs of our patients by defending the patient-clinician relationship. Abortion care saves lives of pregnant patients and reduces maternal morbidity.8 Access to safe abortion care as part of comprehensive reproductive services is an important component of health care. ●

- Roe v Wade, 410 U.S. 113 (1973).

- Planned Parenthood v Casey, 505 U.S. 833 (1992).

- Dobbs v Jackson Women’s Health Organization, 19-1392. https://www.supremecourt.gov/search .aspx?filename=/docket/docketfiles/html /public/19-1392.html. Accessed May 18, 2022.

- Gerstein J, Ward A. Supreme Court has voted to overturn abortion rights, draft opinion shows. Politico. May 5, 2022. Updated May 3, 2022.

- Gold RB. Lessons from before Roe: will past be prologue? Guttmacher Institute. March 1, 2003. https://www.guttmacher.org/gpr/2003/03 /lessons-roe-will-past-be-prologue. Accessed May 18, 2022.

- Edelin KC. Broken Justice: A True Story of Race, Sex and Revenge in a Boston Courtroom. Pond View Press; 2007.

- The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Get involved in your state. ACOG web site. https://www.acog.org/advocacy /get-involved/get-involved-in-your-state. Accessed May 18, 2022.

- Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Improving Birth Outcomes. Bale JR, Stoll BJ, Lucas AO, eds. Reducing maternal mortality and morbidity. In: Improving Birth Outcomes: Meeting the Challenge in the Developing World. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (US); 2003.

- Roe v Wade, 410 U.S. 113 (1973).

- Planned Parenthood v Casey, 505 U.S. 833 (1992).

- Dobbs v Jackson Women’s Health Organization, 19-1392. https://www.supremecourt.gov/search .aspx?filename=/docket/docketfiles/html /public/19-1392.html. Accessed May 18, 2022.

- Gerstein J, Ward A. Supreme Court has voted to overturn abortion rights, draft opinion shows. Politico. May 5, 2022. Updated May 3, 2022.

- Gold RB. Lessons from before Roe: will past be prologue? Guttmacher Institute. March 1, 2003. https://www.guttmacher.org/gpr/2003/03 /lessons-roe-will-past-be-prologue. Accessed May 18, 2022.

- Edelin KC. Broken Justice: A True Story of Race, Sex and Revenge in a Boston Courtroom. Pond View Press; 2007.

- The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Get involved in your state. ACOG web site. https://www.acog.org/advocacy /get-involved/get-involved-in-your-state. Accessed May 18, 2022.

- Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Improving Birth Outcomes. Bale JR, Stoll BJ, Lucas AO, eds. Reducing maternal mortality and morbidity. In: Improving Birth Outcomes: Meeting the Challenge in the Developing World. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (US); 2003.

Office hysteroscopic evaluation of postmenopausal bleeding

Postmenopausal bleeding (PMB) is the presenting sign in most cases of endometrial carcinoma. Prompt evaluation of PMB can exclude, or diagnose, endometrial carcinoma.1 Although no general consensus exists for PMB evaluation, it involves endometrial assessment with transvaginal ultrasonography (TVUS) and subsequent endometrial biopsy when a thickened endometrium is found. When biopsy results reveal insufficient or scant tissue, further investigation into the etiology of PMB should include office hysteroscopy with possible directed biopsy. In this article I discuss the prevalence of PMB and steps for evaluation, providing clinical takeaways.

Postmenopausal bleeding: Its risk for cancer

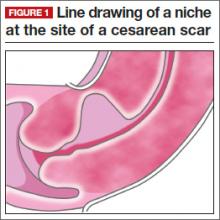

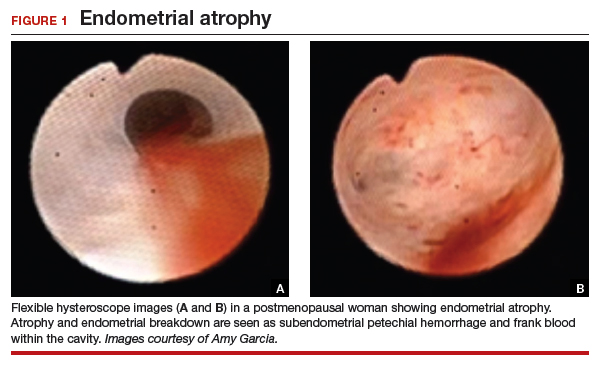

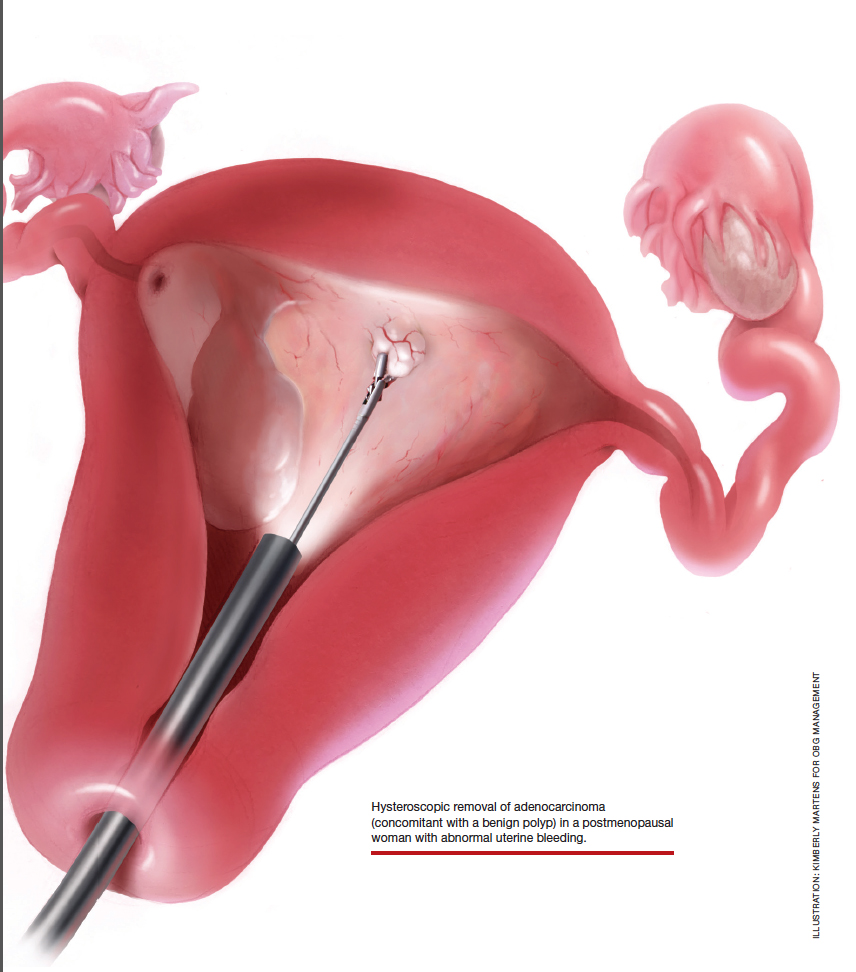

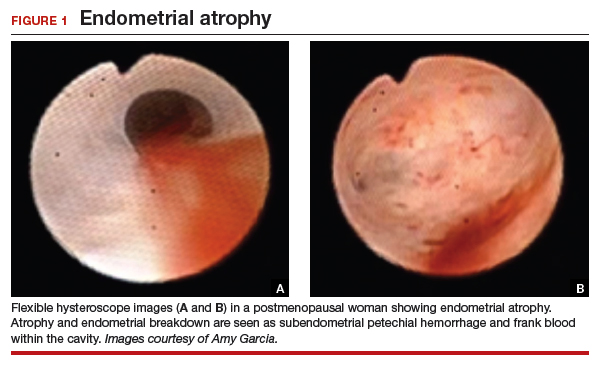

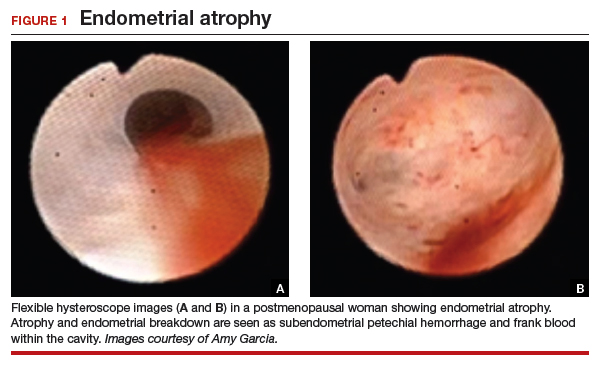

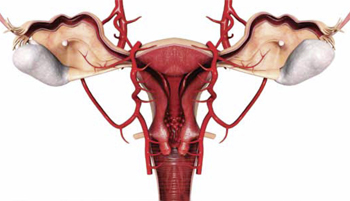

Abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB) in a postmenopausal woman is of particular concern to the gynecologist and the patient because of the increased possibility of endometrial carcinoma in this age group. AUB is present in more than 90% of postmenopausal women with endometrial carcinoma, which leads to diagnosis in the early stages of the disease. Approximately 3% to 7% of postmenopausal women with PMB will have endometrial carcinoma.2 Most women with PMB, however, experience bleeding secondary to atrophic changes of the vagina or endometrium and not to endometrial carcinoma. (FIGURE 1, VIDEO 1) In addition, women who take gonadal steroids for hormone replacement therapy (HRT) may experience breakthrough bleeding that leads to initial investigation with TVUS.

Video 1

The risk of malignancy in polyps in postmenopausal women over the age of 59 who present with PMB is approximately 12%, and hysteroscopic resection should routinely be performed. For asymptomatic patients, the risk of a malignant lesion is low—approximately 3%—and for these women intervention should be assessed individually for the risks of carcinoma and benefits of hysteroscopic removal.3

Clinical takeaway. The high possibility of endometrial carcinoma in postmenopausal women warrants that any patient who is symptomatic with PMB should be presumed to have endometrial cancer until the diagnostic evaluation process proves she does not.

Evaluation of postmenopausal bleeding

Transvaginal ultrasound

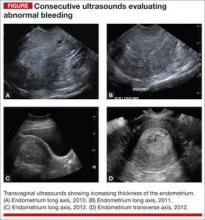

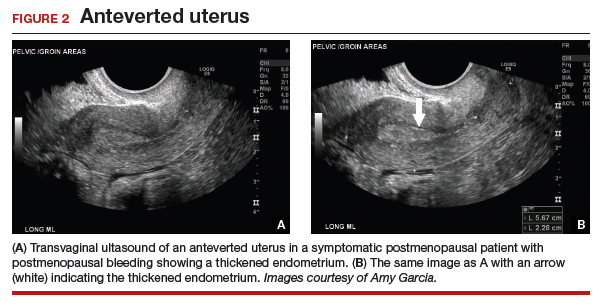

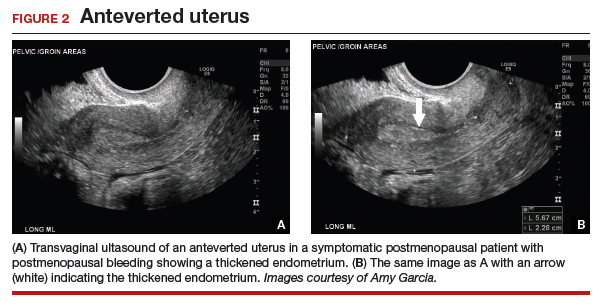

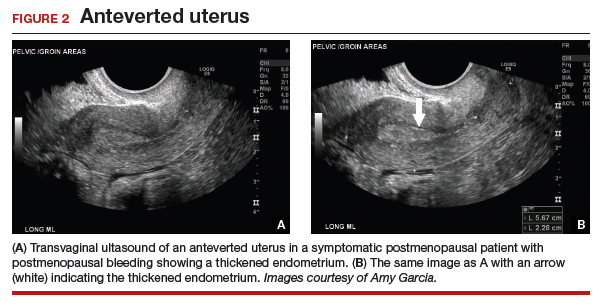

As mentioned, no general consensus exists for the evaluation of PMB; however, initial evaluation by TVUS is recommended. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) concluded that when the endometrium measures ≤4 mm with TVUS, the likelihood that bleeding is secondary to endometrial carcinoma is less than 1% (negative predictive value 99%), and endometrial biopsy is not recommended.3 Endometrial sampling in this clinical scenario likely will result in insufficient tissue for evaluation, and it is reasonable to consider initial management for atrophy. A thickened endometrium on TVUS (>4 mm in a postmenopausal woman with PMB) warrants additional evaluation with endometrial sampling (FIGURE 2).

Clinical takeaway. A thickened endometrium on TVUS ≥4 mm in a postmenopausal woman with PMB warrants additional evaluation with endometrial sampling.

Endometrial biopsy

An endometrial biopsy is performed to determine whether endometrial cancer or precancer is present in women with AUB. ACOG recommends that endometrial biopsy be performed for women older than age 45. It is also appropriate in women younger than 45 years if they have risk factors for developing endometrial cancer, including unopposed estrogen exposure (obesity, ovulatory dysfunction), failed medical management of AUB, or persistence of AUB.4

Continue to: Endometrial biopsy has some...

Endometrial biopsy has some diagnostic shortcomings, however. In 2016 a systematic review and meta-analysis found that, in women with PMB, the specificity of endometrial biopsy was 98% to 100% (accurate diagnosis with a positive result). The sensitivity (ability to make an accurate diagnosis) of endometrial biopsy to identify endometrial pathology (carcinoma, atypical hyperplasia, and polyps) is lower than typically thought. These investigators found an endometrial biopsy failure rate of 11% (range, 1% to 53%) and rate of insufficient samples of 31% (range, 7% to 76%). In women with insufficient or failed samples, endometrial cancer or precancer was found in 7% (range, 0% to 18%).5 Therefore, a negative tissue biopsy result in women with PMB is not considered to be an endpoint, and further evaluation with hysteroscopy to evaluate for focal disease is imperative. The results of endometrial biopsy are only an endpoint to the evaluation of PMB when atypical hyperplasia or endometrial cancer is identified.

Clinical takeaway. A negative tissue biopsy result in women with PMB is not considered to be an endpoint, and further evaluation with hysteroscopy to evaluate for focal disease is imperative.

Hysteroscopy

Hysteroscopy is the gold standard for evaluating the uterine cavity, diagnosing intrauterine pathology, and operative intervention for some causes of AUB. It also is easily performed in the office. This makes the hysteroscope an essential instrument for the gynecologist. Dr. Linda Bradley, a preeminent leader in hysteroscopic surgical education, has coined the phrase, “My hysteroscope is my stethoscope.”6 As gynecologists, we should be as adept at using a hysteroscope in the office as the cardiologist is at using a stethoscope.

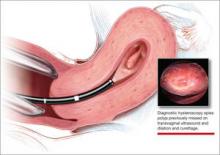

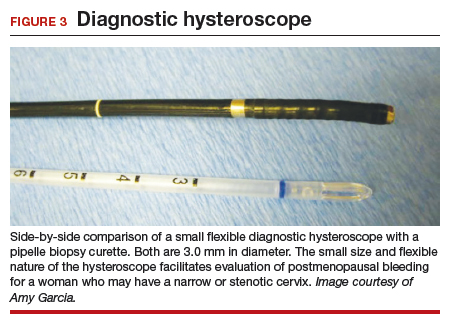

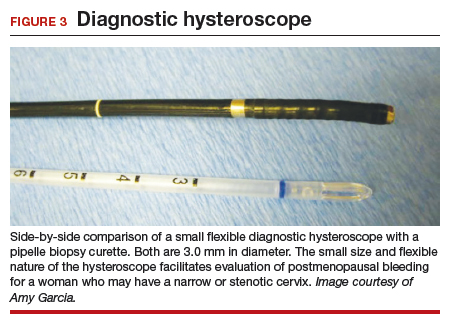

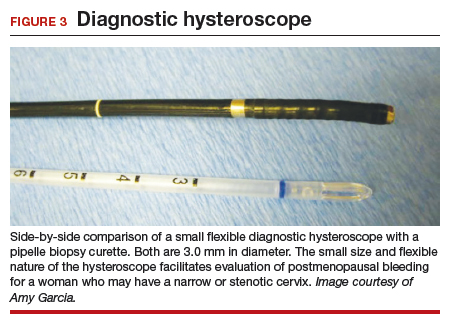

It has been known for some time that hysteroscopy improves our diagnostic capabilities over blinded procedures such as endometrial biopsy and dilation and curettage (D&C). As far back as 1989, Dr. Frank Loffer reported the increased sensitivity (ability to make an accurate diagnosis) of hysteroscopy with directed biopsy over blinded D&C (98% vs 65%) in the evaluation of AUB.7 Evaluation of the endometrium with D&C is no longer recommended; yet today, few gynecologists perform hysteroscopic-directed biopsy for AUB evaluation instead of blinded tissue sampling despite the clinical superiority and in-office capabilities (FIGURE 3).

Continue to: Hysteroscopy and endometrial carcinoma...

Hysteroscopy and endometrial carcinoma

The most common type of gynecologic cancer in the United States is endometrial adenocarcinoma (type 1 endometrial cancer). There is some concern about the effect of hysteroscopy on endometrial cancer prognosis and the spread of cells to the peritoneum at the time of hysteroscopy. A large meta-analysis found that hysteroscopy performed in the presence of type 1 endometrial cancer statistically significantly increased the likelihood of positive intraperitoneal cytology; however, it did not alter the clinical outcome. It was recommended that hysteroscopy not be avoided for this reason and is helpful in the diagnosis of endometrial cancer, especially in the early stages of disease.8

For endometrial cancer type 2 (serous carcinoma, clear cell carcinoma, and carcinosarcoma), Chen and colleagues reported a statistically significant increase in positive peritoneal cytology for cancers evaluated by hysteroscopy versus D&C. The disease-specific survival for the hysteroscopy group was 60 months, compared with 71 months for the D&C group. While this finding was not statistically significant, it was clinically relevant, and the effect of hysteroscopy on prognosis with type 2 endometrial cancer is unclear.9

A common occurrence in the evaluation of postmenopausal bleeding (PMB) is an initial TVUS finding of an enlarged endometrium and an endometrial biopsy that is negative or reveals scant or insufficient tissue. Unfortunately, the diagnostic evaluation process often stops here, and a diagnosis for the PMB is never actually identified. Here are several clinical scenarios that highlight the need for hysteroscopy in the initial evaluation of PMB, especially when there is a discordance between transvaginal ultrasonography (TVUS) and endometrial biopsy findings.

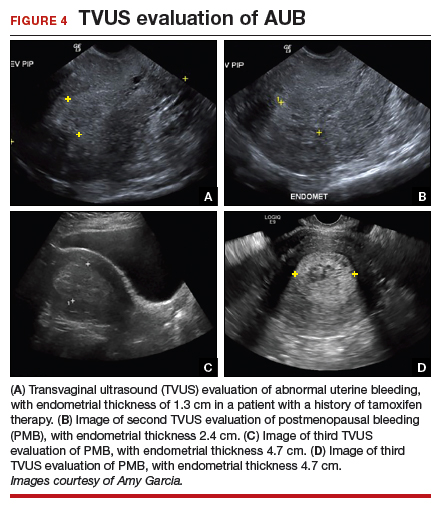

Patient 1: Discordant TVUS and biopsy, with benign findings

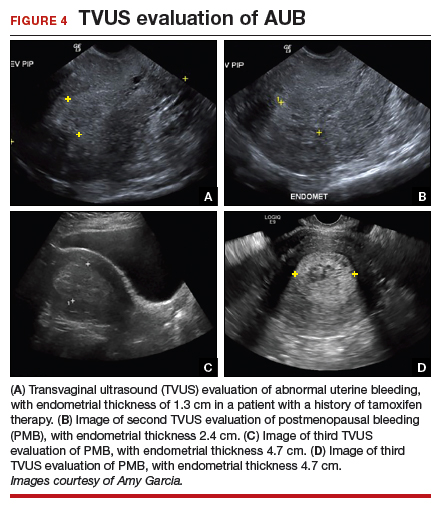

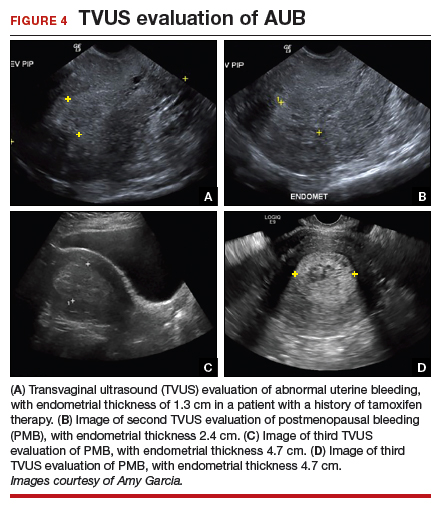

The patient is a 52-year-old woman who presented to her gynecologist reporting abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB). She has a history of breast cancer, and she completed tamoxifen treatment. Pelvic ultrasonography was performed; an enlarged endometrial stripe of 1.3 cm was found (FIGURE 4A). Endometrial biopsy was performed, showing adequate tissue but with a negative result. The patient is told that she is likely perimenopausal, which is the reason for her bleeding.

At the time of referral, the patient is evaluated with in-office hysteroscopy. Diagnosis of a 5 cm x 7 cm benign endometrial polyp is made. An uneventful hysteroscopic polypectomy is performed (VIDEO 2).

Video 2

This scenario illustrates the shortcoming of initial evaluation by not performing a hysteroscopy, especially in a woman with a thickened endometrium with previous tamoxifen therapy. Subsequent visits failed to correlate bleeding etiology with discordant TVUS and endometrial biopsy results with hysteroscopy, and no hysteroscopy was performed in the operating room at the time of D&C.

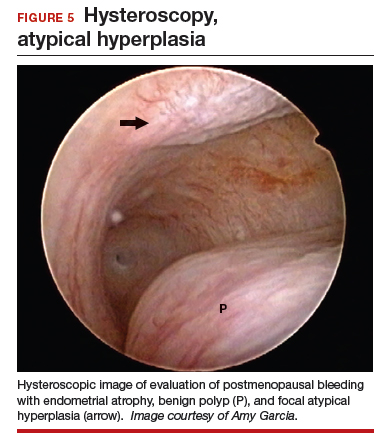

Patient 2: Discordant TVUS and biopsy, with premalignant findings

The patient is a 62-year-old woman who had incidental findings of a thickened endometrium on computed tomography scan of the pelvis. TVUS confirmed a thickened endometrium measuring 17 mm, and an endometrial biopsy showed scant tissue.

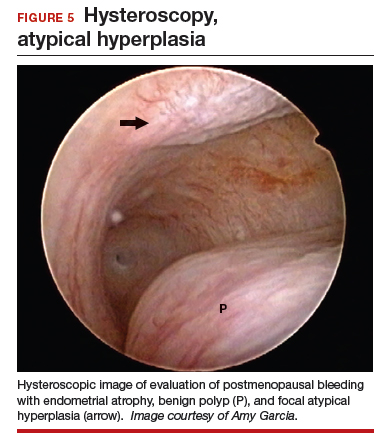

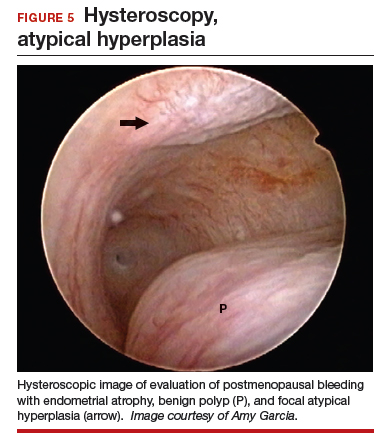

At the time of referral, a diagnostic hysteroscopy was performed in the office. Endometrial atrophy, a large benign appearing polyp, and focal abnormal appearing tissue were seen (FIGURE 5). A decision for polypectomy and directed biopsy was made. Histology findings confirmed benign polyp and atypical hyperplasia (VIDEO 3).

Video 3

This scenario illustrates that while the patient was asymptomatic, there was discordance between the TVUS and endometrial biopsy. Hysteroscopy identified a benign endometrial polyp, which is common in asymptomatic postmenopausal patients with a thickened endometrium and endometrial biopsy showing scant tissue. However, addition of the diagnostic hysteroscopy identified focal precancerous tissue, removed under directed biopsy.

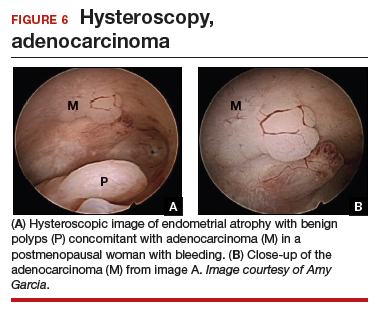

Patient 3: Discordant TVUS and biopsy, with malignant findings

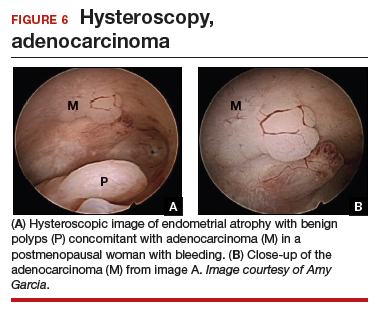

The patient is a 68-year-old woman with PMB. TVUS showed a thickened endometrium measuring 14 mm. An endometrial biopsy was negative, showing scant tissue. No additional diagnostic evaluation or management was offered.

Video 4A

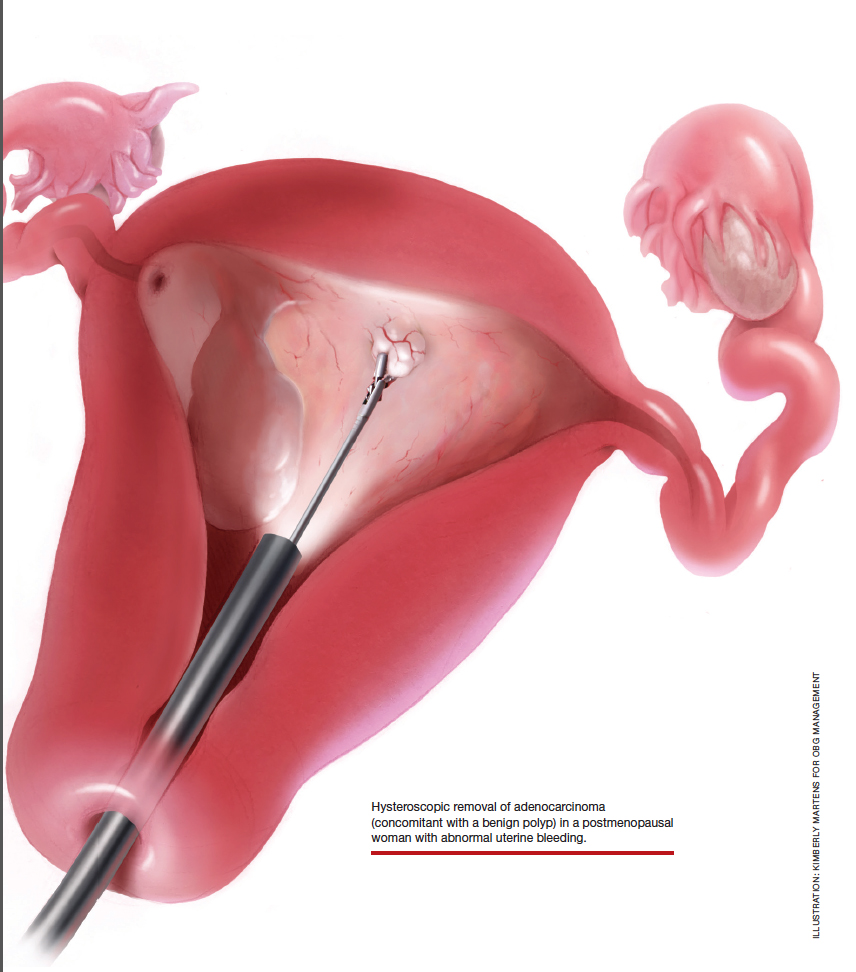

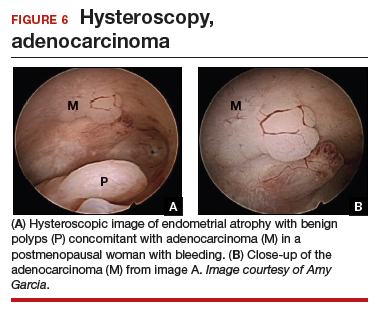

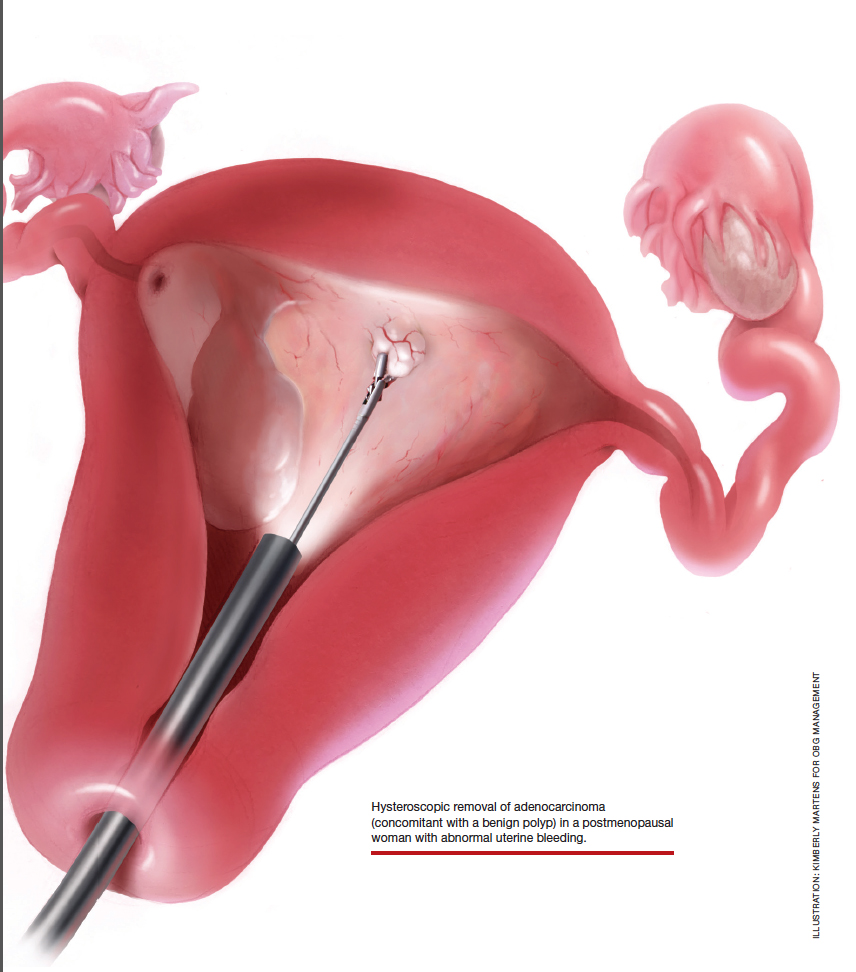

At the time of referral, the patient was evaluated with in-office diagnostic hysteroscopy, and the patient was found to have endometrial atrophy, benign appearing polyps, and focal abnormal tissue (FIGURE 6). A decision for polypectomy and directed biopsy was made. Histology confirmed benign polyps and grade 1 adenocarcinoma (VIDEOS 4A, 4B, 4C).

Video 4B

This scenario illustrates the possibility of having multiple endometrial pathologies present at the time of discordant TVUS and endometrial biopsy. Hysteroscopy plays a critical role in additional evaluation and diagnosis of endometrial carcinoma with directed biopsy, especially in a symptomatic woman with PMB.

Video 4C

Conclusion

Evaluation of PMB begins with a screening TVUS. Findings of an endometrium of ≤4 mm indicate a very low likelihood of the presence of endometrial cancer, and treatment for atrophy or changes to hormone replacement therapy regimen is reasonable first-line management; endometrial biopsy is not recommended. For patients with persistent PMB or thickened endometrium ≥4 mm on TVUS, biopsy sampling of the endometrium should be performed. If the endometrial biopsy does not explain the etiology of the PMB with atypical hyperplasia or endometrial cancer, then hysteroscopy should be performed to evaluate for focal endometrial disease and possible directed biopsy.

- ACOG Committee Opinion no. 734: the role of transvaginal ultrasonography in evaluating the endometrium of women with postmenopausal bleeding. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131:e124-e129.

- Goldstein SR. Appropriate evaluation of postmenopausal bleeding. Menopause. 2018;25:1476-1478.

- Bel S, Billard C, Godet J, et al. Risk of malignancy on suspicion of polyps in menopausal women. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2017;216:138-142.

- Practice bulletin no. 128: diagnosis of abnormal uterine bleeding in reproductive-aged women. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120:197-206.

- van Hanegem N, Prins MM, Bongers MY. The accuracy of endometrial sampling in women with postmenopausal bleeding: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2016;197:147-155.

- Embracing hysteroscopy. September 6, 2017. https://consultqd.clevelandclinic.org/embracing-hysteroscopy/. Accessed July 22, 2019.

- Loffer FD. Hysteroscopy with selective endometrial sampling compared with D&C for abnormal uterine bleeding: the value of a negative hysteroscopic view. Obstet Gynecol. 1989;73:16-20.

- Chang YN, Zhang Y, Wang LP, et al. Effect of hysteroscopy on the peritoneal dissemination of endometrial cancer cells: a meta-analysis. Fertil Steril. 2011;96:957-961.

- Chen J, Clark LH, Kong WM, et al. Does hysteroscopy worsen prognosis in women with type II endometrial carcinoma? PLoS One. 2017;12:e0174226.

Postmenopausal bleeding (PMB) is the presenting sign in most cases of endometrial carcinoma. Prompt evaluation of PMB can exclude, or diagnose, endometrial carcinoma.1 Although no general consensus exists for PMB evaluation, it involves endometrial assessment with transvaginal ultrasonography (TVUS) and subsequent endometrial biopsy when a thickened endometrium is found. When biopsy results reveal insufficient or scant tissue, further investigation into the etiology of PMB should include office hysteroscopy with possible directed biopsy. In this article I discuss the prevalence of PMB and steps for evaluation, providing clinical takeaways.

Postmenopausal bleeding: Its risk for cancer

Abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB) in a postmenopausal woman is of particular concern to the gynecologist and the patient because of the increased possibility of endometrial carcinoma in this age group. AUB is present in more than 90% of postmenopausal women with endometrial carcinoma, which leads to diagnosis in the early stages of the disease. Approximately 3% to 7% of postmenopausal women with PMB will have endometrial carcinoma.2 Most women with PMB, however, experience bleeding secondary to atrophic changes of the vagina or endometrium and not to endometrial carcinoma. (FIGURE 1, VIDEO 1) In addition, women who take gonadal steroids for hormone replacement therapy (HRT) may experience breakthrough bleeding that leads to initial investigation with TVUS.

Video 1

The risk of malignancy in polyps in postmenopausal women over the age of 59 who present with PMB is approximately 12%, and hysteroscopic resection should routinely be performed. For asymptomatic patients, the risk of a malignant lesion is low—approximately 3%—and for these women intervention should be assessed individually for the risks of carcinoma and benefits of hysteroscopic removal.3

Clinical takeaway. The high possibility of endometrial carcinoma in postmenopausal women warrants that any patient who is symptomatic with PMB should be presumed to have endometrial cancer until the diagnostic evaluation process proves she does not.

Evaluation of postmenopausal bleeding

Transvaginal ultrasound

As mentioned, no general consensus exists for the evaluation of PMB; however, initial evaluation by TVUS is recommended. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) concluded that when the endometrium measures ≤4 mm with TVUS, the likelihood that bleeding is secondary to endometrial carcinoma is less than 1% (negative predictive value 99%), and endometrial biopsy is not recommended.3 Endometrial sampling in this clinical scenario likely will result in insufficient tissue for evaluation, and it is reasonable to consider initial management for atrophy. A thickened endometrium on TVUS (>4 mm in a postmenopausal woman with PMB) warrants additional evaluation with endometrial sampling (FIGURE 2).

Clinical takeaway. A thickened endometrium on TVUS ≥4 mm in a postmenopausal woman with PMB warrants additional evaluation with endometrial sampling.

Endometrial biopsy

An endometrial biopsy is performed to determine whether endometrial cancer or precancer is present in women with AUB. ACOG recommends that endometrial biopsy be performed for women older than age 45. It is also appropriate in women younger than 45 years if they have risk factors for developing endometrial cancer, including unopposed estrogen exposure (obesity, ovulatory dysfunction), failed medical management of AUB, or persistence of AUB.4

Continue to: Endometrial biopsy has some...

Endometrial biopsy has some diagnostic shortcomings, however. In 2016 a systematic review and meta-analysis found that, in women with PMB, the specificity of endometrial biopsy was 98% to 100% (accurate diagnosis with a positive result). The sensitivity (ability to make an accurate diagnosis) of endometrial biopsy to identify endometrial pathology (carcinoma, atypical hyperplasia, and polyps) is lower than typically thought. These investigators found an endometrial biopsy failure rate of 11% (range, 1% to 53%) and rate of insufficient samples of 31% (range, 7% to 76%). In women with insufficient or failed samples, endometrial cancer or precancer was found in 7% (range, 0% to 18%).5 Therefore, a negative tissue biopsy result in women with PMB is not considered to be an endpoint, and further evaluation with hysteroscopy to evaluate for focal disease is imperative. The results of endometrial biopsy are only an endpoint to the evaluation of PMB when atypical hyperplasia or endometrial cancer is identified.

Clinical takeaway. A negative tissue biopsy result in women with PMB is not considered to be an endpoint, and further evaluation with hysteroscopy to evaluate for focal disease is imperative.

Hysteroscopy

Hysteroscopy is the gold standard for evaluating the uterine cavity, diagnosing intrauterine pathology, and operative intervention for some causes of AUB. It also is easily performed in the office. This makes the hysteroscope an essential instrument for the gynecologist. Dr. Linda Bradley, a preeminent leader in hysteroscopic surgical education, has coined the phrase, “My hysteroscope is my stethoscope.”6 As gynecologists, we should be as adept at using a hysteroscope in the office as the cardiologist is at using a stethoscope.

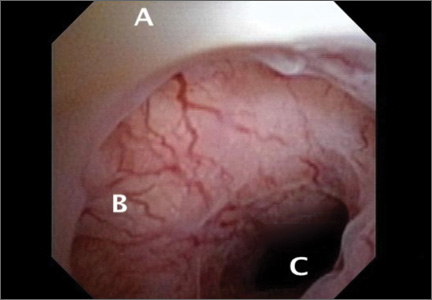

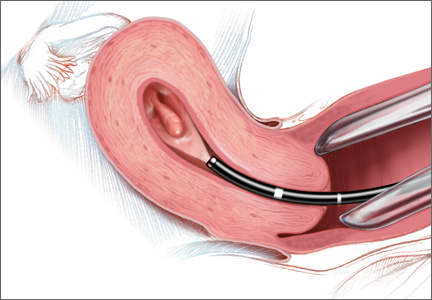

It has been known for some time that hysteroscopy improves our diagnostic capabilities over blinded procedures such as endometrial biopsy and dilation and curettage (D&C). As far back as 1989, Dr. Frank Loffer reported the increased sensitivity (ability to make an accurate diagnosis) of hysteroscopy with directed biopsy over blinded D&C (98% vs 65%) in the evaluation of AUB.7 Evaluation of the endometrium with D&C is no longer recommended; yet today, few gynecologists perform hysteroscopic-directed biopsy for AUB evaluation instead of blinded tissue sampling despite the clinical superiority and in-office capabilities (FIGURE 3).

Continue to: Hysteroscopy and endometrial carcinoma...

Hysteroscopy and endometrial carcinoma

The most common type of gynecologic cancer in the United States is endometrial adenocarcinoma (type 1 endometrial cancer). There is some concern about the effect of hysteroscopy on endometrial cancer prognosis and the spread of cells to the peritoneum at the time of hysteroscopy. A large meta-analysis found that hysteroscopy performed in the presence of type 1 endometrial cancer statistically significantly increased the likelihood of positive intraperitoneal cytology; however, it did not alter the clinical outcome. It was recommended that hysteroscopy not be avoided for this reason and is helpful in the diagnosis of endometrial cancer, especially in the early stages of disease.8

For endometrial cancer type 2 (serous carcinoma, clear cell carcinoma, and carcinosarcoma), Chen and colleagues reported a statistically significant increase in positive peritoneal cytology for cancers evaluated by hysteroscopy versus D&C. The disease-specific survival for the hysteroscopy group was 60 months, compared with 71 months for the D&C group. While this finding was not statistically significant, it was clinically relevant, and the effect of hysteroscopy on prognosis with type 2 endometrial cancer is unclear.9

A common occurrence in the evaluation of postmenopausal bleeding (PMB) is an initial TVUS finding of an enlarged endometrium and an endometrial biopsy that is negative or reveals scant or insufficient tissue. Unfortunately, the diagnostic evaluation process often stops here, and a diagnosis for the PMB is never actually identified. Here are several clinical scenarios that highlight the need for hysteroscopy in the initial evaluation of PMB, especially when there is a discordance between transvaginal ultrasonography (TVUS) and endometrial biopsy findings.

Patient 1: Discordant TVUS and biopsy, with benign findings

The patient is a 52-year-old woman who presented to her gynecologist reporting abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB). She has a history of breast cancer, and she completed tamoxifen treatment. Pelvic ultrasonography was performed; an enlarged endometrial stripe of 1.3 cm was found (FIGURE 4A). Endometrial biopsy was performed, showing adequate tissue but with a negative result. The patient is told that she is likely perimenopausal, which is the reason for her bleeding.

At the time of referral, the patient is evaluated with in-office hysteroscopy. Diagnosis of a 5 cm x 7 cm benign endometrial polyp is made. An uneventful hysteroscopic polypectomy is performed (VIDEO 2).

Video 2

This scenario illustrates the shortcoming of initial evaluation by not performing a hysteroscopy, especially in a woman with a thickened endometrium with previous tamoxifen therapy. Subsequent visits failed to correlate bleeding etiology with discordant TVUS and endometrial biopsy results with hysteroscopy, and no hysteroscopy was performed in the operating room at the time of D&C.

Patient 2: Discordant TVUS and biopsy, with premalignant findings

The patient is a 62-year-old woman who had incidental findings of a thickened endometrium on computed tomography scan of the pelvis. TVUS confirmed a thickened endometrium measuring 17 mm, and an endometrial biopsy showed scant tissue.

At the time of referral, a diagnostic hysteroscopy was performed in the office. Endometrial atrophy, a large benign appearing polyp, and focal abnormal appearing tissue were seen (FIGURE 5). A decision for polypectomy and directed biopsy was made. Histology findings confirmed benign polyp and atypical hyperplasia (VIDEO 3).

Video 3

This scenario illustrates that while the patient was asymptomatic, there was discordance between the TVUS and endometrial biopsy. Hysteroscopy identified a benign endometrial polyp, which is common in asymptomatic postmenopausal patients with a thickened endometrium and endometrial biopsy showing scant tissue. However, addition of the diagnostic hysteroscopy identified focal precancerous tissue, removed under directed biopsy.

Patient 3: Discordant TVUS and biopsy, with malignant findings

The patient is a 68-year-old woman with PMB. TVUS showed a thickened endometrium measuring 14 mm. An endometrial biopsy was negative, showing scant tissue. No additional diagnostic evaluation or management was offered.

Video 4A

At the time of referral, the patient was evaluated with in-office diagnostic hysteroscopy, and the patient was found to have endometrial atrophy, benign appearing polyps, and focal abnormal tissue (FIGURE 6). A decision for polypectomy and directed biopsy was made. Histology confirmed benign polyps and grade 1 adenocarcinoma (VIDEOS 4A, 4B, 4C).

Video 4B

This scenario illustrates the possibility of having multiple endometrial pathologies present at the time of discordant TVUS and endometrial biopsy. Hysteroscopy plays a critical role in additional evaluation and diagnosis of endometrial carcinoma with directed biopsy, especially in a symptomatic woman with PMB.

Video 4C

Conclusion

Evaluation of PMB begins with a screening TVUS. Findings of an endometrium of ≤4 mm indicate a very low likelihood of the presence of endometrial cancer, and treatment for atrophy or changes to hormone replacement therapy regimen is reasonable first-line management; endometrial biopsy is not recommended. For patients with persistent PMB or thickened endometrium ≥4 mm on TVUS, biopsy sampling of the endometrium should be performed. If the endometrial biopsy does not explain the etiology of the PMB with atypical hyperplasia or endometrial cancer, then hysteroscopy should be performed to evaluate for focal endometrial disease and possible directed biopsy.

Postmenopausal bleeding (PMB) is the presenting sign in most cases of endometrial carcinoma. Prompt evaluation of PMB can exclude, or diagnose, endometrial carcinoma.1 Although no general consensus exists for PMB evaluation, it involves endometrial assessment with transvaginal ultrasonography (TVUS) and subsequent endometrial biopsy when a thickened endometrium is found. When biopsy results reveal insufficient or scant tissue, further investigation into the etiology of PMB should include office hysteroscopy with possible directed biopsy. In this article I discuss the prevalence of PMB and steps for evaluation, providing clinical takeaways.

Postmenopausal bleeding: Its risk for cancer

Abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB) in a postmenopausal woman is of particular concern to the gynecologist and the patient because of the increased possibility of endometrial carcinoma in this age group. AUB is present in more than 90% of postmenopausal women with endometrial carcinoma, which leads to diagnosis in the early stages of the disease. Approximately 3% to 7% of postmenopausal women with PMB will have endometrial carcinoma.2 Most women with PMB, however, experience bleeding secondary to atrophic changes of the vagina or endometrium and not to endometrial carcinoma. (FIGURE 1, VIDEO 1) In addition, women who take gonadal steroids for hormone replacement therapy (HRT) may experience breakthrough bleeding that leads to initial investigation with TVUS.

Video 1

The risk of malignancy in polyps in postmenopausal women over the age of 59 who present with PMB is approximately 12%, and hysteroscopic resection should routinely be performed. For asymptomatic patients, the risk of a malignant lesion is low—approximately 3%—and for these women intervention should be assessed individually for the risks of carcinoma and benefits of hysteroscopic removal.3

Clinical takeaway. The high possibility of endometrial carcinoma in postmenopausal women warrants that any patient who is symptomatic with PMB should be presumed to have endometrial cancer until the diagnostic evaluation process proves she does not.

Evaluation of postmenopausal bleeding

Transvaginal ultrasound

As mentioned, no general consensus exists for the evaluation of PMB; however, initial evaluation by TVUS is recommended. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) concluded that when the endometrium measures ≤4 mm with TVUS, the likelihood that bleeding is secondary to endometrial carcinoma is less than 1% (negative predictive value 99%), and endometrial biopsy is not recommended.3 Endometrial sampling in this clinical scenario likely will result in insufficient tissue for evaluation, and it is reasonable to consider initial management for atrophy. A thickened endometrium on TVUS (>4 mm in a postmenopausal woman with PMB) warrants additional evaluation with endometrial sampling (FIGURE 2).

Clinical takeaway. A thickened endometrium on TVUS ≥4 mm in a postmenopausal woman with PMB warrants additional evaluation with endometrial sampling.

Endometrial biopsy

An endometrial biopsy is performed to determine whether endometrial cancer or precancer is present in women with AUB. ACOG recommends that endometrial biopsy be performed for women older than age 45. It is also appropriate in women younger than 45 years if they have risk factors for developing endometrial cancer, including unopposed estrogen exposure (obesity, ovulatory dysfunction), failed medical management of AUB, or persistence of AUB.4

Continue to: Endometrial biopsy has some...

Endometrial biopsy has some diagnostic shortcomings, however. In 2016 a systematic review and meta-analysis found that, in women with PMB, the specificity of endometrial biopsy was 98% to 100% (accurate diagnosis with a positive result). The sensitivity (ability to make an accurate diagnosis) of endometrial biopsy to identify endometrial pathology (carcinoma, atypical hyperplasia, and polyps) is lower than typically thought. These investigators found an endometrial biopsy failure rate of 11% (range, 1% to 53%) and rate of insufficient samples of 31% (range, 7% to 76%). In women with insufficient or failed samples, endometrial cancer or precancer was found in 7% (range, 0% to 18%).5 Therefore, a negative tissue biopsy result in women with PMB is not considered to be an endpoint, and further evaluation with hysteroscopy to evaluate for focal disease is imperative. The results of endometrial biopsy are only an endpoint to the evaluation of PMB when atypical hyperplasia or endometrial cancer is identified.

Clinical takeaway. A negative tissue biopsy result in women with PMB is not considered to be an endpoint, and further evaluation with hysteroscopy to evaluate for focal disease is imperative.

Hysteroscopy

Hysteroscopy is the gold standard for evaluating the uterine cavity, diagnosing intrauterine pathology, and operative intervention for some causes of AUB. It also is easily performed in the office. This makes the hysteroscope an essential instrument for the gynecologist. Dr. Linda Bradley, a preeminent leader in hysteroscopic surgical education, has coined the phrase, “My hysteroscope is my stethoscope.”6 As gynecologists, we should be as adept at using a hysteroscope in the office as the cardiologist is at using a stethoscope.

It has been known for some time that hysteroscopy improves our diagnostic capabilities over blinded procedures such as endometrial biopsy and dilation and curettage (D&C). As far back as 1989, Dr. Frank Loffer reported the increased sensitivity (ability to make an accurate diagnosis) of hysteroscopy with directed biopsy over blinded D&C (98% vs 65%) in the evaluation of AUB.7 Evaluation of the endometrium with D&C is no longer recommended; yet today, few gynecologists perform hysteroscopic-directed biopsy for AUB evaluation instead of blinded tissue sampling despite the clinical superiority and in-office capabilities (FIGURE 3).

Continue to: Hysteroscopy and endometrial carcinoma...

Hysteroscopy and endometrial carcinoma

The most common type of gynecologic cancer in the United States is endometrial adenocarcinoma (type 1 endometrial cancer). There is some concern about the effect of hysteroscopy on endometrial cancer prognosis and the spread of cells to the peritoneum at the time of hysteroscopy. A large meta-analysis found that hysteroscopy performed in the presence of type 1 endometrial cancer statistically significantly increased the likelihood of positive intraperitoneal cytology; however, it did not alter the clinical outcome. It was recommended that hysteroscopy not be avoided for this reason and is helpful in the diagnosis of endometrial cancer, especially in the early stages of disease.8

For endometrial cancer type 2 (serous carcinoma, clear cell carcinoma, and carcinosarcoma), Chen and colleagues reported a statistically significant increase in positive peritoneal cytology for cancers evaluated by hysteroscopy versus D&C. The disease-specific survival for the hysteroscopy group was 60 months, compared with 71 months for the D&C group. While this finding was not statistically significant, it was clinically relevant, and the effect of hysteroscopy on prognosis with type 2 endometrial cancer is unclear.9

A common occurrence in the evaluation of postmenopausal bleeding (PMB) is an initial TVUS finding of an enlarged endometrium and an endometrial biopsy that is negative or reveals scant or insufficient tissue. Unfortunately, the diagnostic evaluation process often stops here, and a diagnosis for the PMB is never actually identified. Here are several clinical scenarios that highlight the need for hysteroscopy in the initial evaluation of PMB, especially when there is a discordance between transvaginal ultrasonography (TVUS) and endometrial biopsy findings.

Patient 1: Discordant TVUS and biopsy, with benign findings

The patient is a 52-year-old woman who presented to her gynecologist reporting abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB). She has a history of breast cancer, and she completed tamoxifen treatment. Pelvic ultrasonography was performed; an enlarged endometrial stripe of 1.3 cm was found (FIGURE 4A). Endometrial biopsy was performed, showing adequate tissue but with a negative result. The patient is told that she is likely perimenopausal, which is the reason for her bleeding.

At the time of referral, the patient is evaluated with in-office hysteroscopy. Diagnosis of a 5 cm x 7 cm benign endometrial polyp is made. An uneventful hysteroscopic polypectomy is performed (VIDEO 2).

Video 2

This scenario illustrates the shortcoming of initial evaluation by not performing a hysteroscopy, especially in a woman with a thickened endometrium with previous tamoxifen therapy. Subsequent visits failed to correlate bleeding etiology with discordant TVUS and endometrial biopsy results with hysteroscopy, and no hysteroscopy was performed in the operating room at the time of D&C.

Patient 2: Discordant TVUS and biopsy, with premalignant findings

The patient is a 62-year-old woman who had incidental findings of a thickened endometrium on computed tomography scan of the pelvis. TVUS confirmed a thickened endometrium measuring 17 mm, and an endometrial biopsy showed scant tissue.

At the time of referral, a diagnostic hysteroscopy was performed in the office. Endometrial atrophy, a large benign appearing polyp, and focal abnormal appearing tissue were seen (FIGURE 5). A decision for polypectomy and directed biopsy was made. Histology findings confirmed benign polyp and atypical hyperplasia (VIDEO 3).

Video 3

This scenario illustrates that while the patient was asymptomatic, there was discordance between the TVUS and endometrial biopsy. Hysteroscopy identified a benign endometrial polyp, which is common in asymptomatic postmenopausal patients with a thickened endometrium and endometrial biopsy showing scant tissue. However, addition of the diagnostic hysteroscopy identified focal precancerous tissue, removed under directed biopsy.

Patient 3: Discordant TVUS and biopsy, with malignant findings

The patient is a 68-year-old woman with PMB. TVUS showed a thickened endometrium measuring 14 mm. An endometrial biopsy was negative, showing scant tissue. No additional diagnostic evaluation or management was offered.

Video 4A

At the time of referral, the patient was evaluated with in-office diagnostic hysteroscopy, and the patient was found to have endometrial atrophy, benign appearing polyps, and focal abnormal tissue (FIGURE 6). A decision for polypectomy and directed biopsy was made. Histology confirmed benign polyps and grade 1 adenocarcinoma (VIDEOS 4A, 4B, 4C).

Video 4B

This scenario illustrates the possibility of having multiple endometrial pathologies present at the time of discordant TVUS and endometrial biopsy. Hysteroscopy plays a critical role in additional evaluation and diagnosis of endometrial carcinoma with directed biopsy, especially in a symptomatic woman with PMB.

Video 4C

Conclusion

Evaluation of PMB begins with a screening TVUS. Findings of an endometrium of ≤4 mm indicate a very low likelihood of the presence of endometrial cancer, and treatment for atrophy or changes to hormone replacement therapy regimen is reasonable first-line management; endometrial biopsy is not recommended. For patients with persistent PMB or thickened endometrium ≥4 mm on TVUS, biopsy sampling of the endometrium should be performed. If the endometrial biopsy does not explain the etiology of the PMB with atypical hyperplasia or endometrial cancer, then hysteroscopy should be performed to evaluate for focal endometrial disease and possible directed biopsy.

- ACOG Committee Opinion no. 734: the role of transvaginal ultrasonography in evaluating the endometrium of women with postmenopausal bleeding. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131:e124-e129.

- Goldstein SR. Appropriate evaluation of postmenopausal bleeding. Menopause. 2018;25:1476-1478.

- Bel S, Billard C, Godet J, et al. Risk of malignancy on suspicion of polyps in menopausal women. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2017;216:138-142.

- Practice bulletin no. 128: diagnosis of abnormal uterine bleeding in reproductive-aged women. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120:197-206.

- van Hanegem N, Prins MM, Bongers MY. The accuracy of endometrial sampling in women with postmenopausal bleeding: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2016;197:147-155.

- Embracing hysteroscopy. September 6, 2017. https://consultqd.clevelandclinic.org/embracing-hysteroscopy/. Accessed July 22, 2019.

- Loffer FD. Hysteroscopy with selective endometrial sampling compared with D&C for abnormal uterine bleeding: the value of a negative hysteroscopic view. Obstet Gynecol. 1989;73:16-20.

- Chang YN, Zhang Y, Wang LP, et al. Effect of hysteroscopy on the peritoneal dissemination of endometrial cancer cells: a meta-analysis. Fertil Steril. 2011;96:957-961.

- Chen J, Clark LH, Kong WM, et al. Does hysteroscopy worsen prognosis in women with type II endometrial carcinoma? PLoS One. 2017;12:e0174226.

- ACOG Committee Opinion no. 734: the role of transvaginal ultrasonography in evaluating the endometrium of women with postmenopausal bleeding. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131:e124-e129.

- Goldstein SR. Appropriate evaluation of postmenopausal bleeding. Menopause. 2018;25:1476-1478.

- Bel S, Billard C, Godet J, et al. Risk of malignancy on suspicion of polyps in menopausal women. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2017;216:138-142.

- Practice bulletin no. 128: diagnosis of abnormal uterine bleeding in reproductive-aged women. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120:197-206.

- van Hanegem N, Prins MM, Bongers MY. The accuracy of endometrial sampling in women with postmenopausal bleeding: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2016;197:147-155.

- Embracing hysteroscopy. September 6, 2017. https://consultqd.clevelandclinic.org/embracing-hysteroscopy/. Accessed July 22, 2019.

- Loffer FD. Hysteroscopy with selective endometrial sampling compared with D&C for abnormal uterine bleeding: the value of a negative hysteroscopic view. Obstet Gynecol. 1989;73:16-20.

- Chang YN, Zhang Y, Wang LP, et al. Effect of hysteroscopy on the peritoneal dissemination of endometrial cancer cells: a meta-analysis. Fertil Steril. 2011;96:957-961.

- Chen J, Clark LH, Kong WM, et al. Does hysteroscopy worsen prognosis in women with type II endometrial carcinoma? PLoS One. 2017;12:e0174226.

2014 Update on minimally invasive gynecology

CASE: POSTMENSTRUAL BLEEDING, HISTORY OF CESAREAN DELIVERIES

A 36-year-old woman (G3P3) reports prolonged and postmenstrual bleeding. Her cycles are regular, every 28 to 30 days, and are associated with ovulatory symptoms. She bleeds for 8 to 10 days with each cycle, having heavy bleeding on cycle day 2 requiring use of super tampons every 3 hours. Beginning on day 5 of the cycle, the blood becomes much darker and scant requiring a small pad, which she changes twice daily. Often, she experiences dark bleeding with physical activity—specifically, running—usually several days after her cycle has ended. She is otherwise healthy and uses no medications. She uses condoms for contraception. She has had a prior vaginal delivery followed by two cesarean sections. Physical examination is normal.

What is causing this patient’s abnormal bleeding pattern?

From 1996 to 2009, the total US cesarean delivery rate increased steadily from 20.7% to 32.9% and has remained stable at 32.8% through 2012.1 With 3,952,841 registered births in 2012, the number of operative procedures performed annually approximates 1.3 million.2 This means, potentially, that one-third of pregnant American women will undergo cesarean delivery annually, translating into an increasing prevalence of long-term sequelae of this surgery.

An increasingly recognized etiology of AUB

One long-term complication of cesarean delivery, not often discussed, is the presence of a defect within the uterine scar that is directly associated with a type of abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB) referred to as postmenstrual bleeding. Stewart first reported this post–cesarean delivery phenomenon in 1975.3 It is postulated that the cesarean scar defect (CSD)4 forms a pocket, which holds the menstrual effluent, allowing bleeding to occur after regular menstrual cycle bleeding has concluded. Often, remnant menstrual blood is extruded slowly over several days, and is generally dark brown, indicating old blood. Physical activity sometimes can initiate expulsion of the old blood even after the regular cycle has ceased (FIGURE 1).

As early as 1995, Morris reported the histopathologic changes within the cesarean scar in a series of 51 hysterectomy specimens with scar present for 2 to 15 years. His findings included distortion and widening of the lower uterine segment (75%), congested endometrium above the scar recess (61%), marked lymphocytic infiltration (65%), capillary dilation (65%), residual suture material with foreign body giant cell reaction (92%), fragmentation and breakdown of the endometrium of the scar (37%), and iatrogenic adenomyosis confined to the scar (28%). Morris concluded that in addition to AUB, these scar abnormalities could give rise to clinical symptoms such as pelvic pain, dyspareunia, and dysmenorrhea.5 It also has been suggested that otherwise unexplained infertility is associated with anatomic and physiologic changes seen with CSD.6 A recent review article published by Tower summarized additional clinical outcomes of CSD, such as ectopic pregnancy and increased surgical risks for such gynecologic procedures as uterine evacuation in the nonpregnant or postpartum state, hysterectomy, endometrial ablation, and intrauterine device placement.4

The CSD generally is described as a triangular or circular sonographically anechoic area in the myometrium of the anterior lower uterine segment or cervix at the site of a previous cesarean section. In nonpregnant patients, the defect is best evaluated with contrast infusion sonography (CIS), such as saline infusion or gel infusion, versus transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS) alone (FIGURE 2).4,7,8 However, the precise dimensions and definition of the scar defect vary among investigators.4,6,7,8,10

The reported prevalence of CSD has varied in the literature and appears to depend on the modality of diagnosis and the population studied. For instance, van der Voet and colleagues reported that in random populations of women who had undergone cesarean delivery, the defect was evident in 24% to 69% of women evaluated with transvaginal noncontrast ultrasound; the defect was evident in 56% to 78% of women evaluated with transvaginal contrast sonography.8

The scar defect also has been identified with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and found to be equal in sensitivity to TVUS.9,10 When identified hysteroscopically, a definitive out-pouching is visualized in the lower uterine segment, where the defect has been termed an “isthmocele.”6 Hysteroscopically, the defect also is visualized commonly within the cervical canal, indicating that cesarean incisions often are made through cervical tissue at the time of delivery (FIGURE 3, VIDEO 1, VIDEO 2 [see below]). Not all women with CSD report bleeding abnormalities, but it appears that the deeper and wider the defect, the more likely a woman is to present with postmenstrual AUB.7 According to the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) Classification of AUB, CSD-associated postmenstrual bleeding falls into the “iatrogenic” category in the PALM-COIEN pneumonic.11

Related article: Dr. Garcia discusses the FIGO classification and the PALM-COEIN pneumonic in Update: Minimally invasive gynecology (April 2013)

![]()

![]()

A pair of studies shed light on CSD

Two recent European publications by van der Voet and colleagues addressed CSD and its association with AUB. These studies refer to CSD as the “niche” within the cesarean scar, but for the purpose of this article, I will use the term CSD. The first is a prospective cohort study, in which the authors addressed the definition, diagnosis, and prevalence of a defect within the cesarean scar and reported the incidence of associated AUB.7 The second publication is a systematic review which includes a critical investigation of minimally invasive therapy for CSD-related AUB.8 Both publications provide current clinical insight into the evaluation and management of AUB associated with CSD.

Related articles:

• Update on abnormal uterine bleeding Malcolm G. Munro, MD (March 2014)

• Update on Technology Barbara S. Levy, MD (September 2013)

• STOP performing dilation and curettage for the evaluation of abnormal uterine bleeding Amy Garcia, MD (Stop/Start, June 2013)

THE NICHE IN THE SCAR

van der Voet LF, Bij de Vaate AM, Veersema S, Brolmann HAM, Huirne JAF. Long-term complications of caesarean section. The niche in the scar: A prospective cohort study on niche prevalence and its relation to abnormal uterine bleeding. BJOG. 2014;121(2):236–244.

Most studies reporting the prevalence of cesarean delivery–associated postmenstrual bleeding are based on populations of women who were symptomatic with AUB, thus infusing a potential referral bias into these prevalence estimates. In contrast, this study by van der Voet and colleagues utilizes a prospective cohort design, making it the only study to date to enroll a random cohort of patients immediately after having undergone cesarean delivery.

Details of the study

The purpose of the study was to evaluate the prevalence of CSD formation in the cesarean scar at 6 to 12 weeks after cesarean delivery with TVUS and gel infusion study (GIS) in 197 women. The uterus was closed in two layers for four women and in one layer for all others.

The cohort was followed with menstruation questionnaires at 6 to 12 weeks, 6 months, and 12 months after surgery. The questionnaire response rate at 12 months for those women who had both TVUS and GIS evaluation of the scar was 73%. Data analysis accounted for confounding factors such as breastfeeding and amenorrhea, use of hormonal contraception, use of a levonorgestrel intrauterine system (LNG-IUS) as well as a body mass index (BMI) of at least 25 kg/m2.

Consistent with previous studies showing the superiority of saline-infused studies over TVUS for CSD identification,4 van der Voet and colleagues found that GIS was more sensitive than TVUS in diagnosing CSD (64.5% vs 49.6%, respectively). The percentage of women with CSD who had undergone two cesarean deliveries was 68.2%, while the percentage with CSD who had undergone three cesarean deliveries was 77.8%.

Data analysis correlated postmenstrual bleeding with the following CSD characteristics:

- depth and width of the defect

- residual myometrial thickness to the serosal surface of the uterus

- ratio of residual myometrium divided by the adjacent normal myometrial thickness.

Those women who had a ratio of residual myometrium to adjacent normal myometrium of less than 0.5 were more likely to report postmenstrual bleeding than those with a ratio greater than 0.5 (odds ratio, 6.1; 95% confidence interval, 1.74–21.63). The investigators stated that 1 out of 3 women with CSD identified by GIS reported postmenstrual bleeding, compared with 1 out of 10 women without identifiable CSD.

Study takeaways have merit

In summary, despite the small cohort of 197 women and the relatively short observation period of 1 year, these data collected by van der Voet and colleagues enable the gynecologist to begin to more fully understand the potential impact of cesarean section and the probability of AUB following an abdominal delivery. Applying these study statistics to the number of cesarean sections performed annually in the United States translates to nearly 280,000 women yearly who may experience postmenstrual bleeding related to a defect in the cesarean section scar.

Prospective cohort studies with longer follow-up periods are needed to assess the longer-term risks of CSD-related bleeding. As the authors suggest, perhaps the possibility of post–cesarean section AUB should be considered as part of the informed consent process for cesarean delivery.

WHAT THIS EVIDENCE MEANS FOR PRACTICE

• Contrast infusion sonography has better sensitivity than TVUS at identification of the scar defect.

• About 64.5% of women are predicted to have scar defects after one cesarean delivery.

• The incidence of scar defects increases with increasing number of cesarean deliveries.

• One of three women with CSD is predicted to experience postmenstrual bleeding.

• Women with deeper and wider defects are more likely to experience postmenstrual bleeding.

• Post–cesarean section AUB is a probable occurrence in approximately 20% of all cesarean deliveries. Perhaps this information should be considered part of the informed consent process for cesarean delivery.

MINIMALLY INVASIVE THERAPY FOR GYNECOLOGIC SYMPTOMS

van der Voet LF, Vervoort AJ, Veersema S, Bij de Vatte AJ, Brolmann HAM, Huirne JAF. Minimally invasive therapy for gynaecological symptoms related to a niche in the caesarean scar: A systematic review. BJOG. 2014;121(2):145-156.

CSD-related bleeding issues may not respond to hormonal management and are frequently underdiagnosed. This scenario often leads to hysterectomy. Because there are women who desire uterine preservation, van der Voet and colleagues sought to evaluate the results of nonhysterectomy treatments of CSD-related AUB. They limited this systematic review to include only published studies that were randomized controlled trials, cohort studies, case-control studies, and case series of at least five patients.

Additionally, they included only studies that reported on conservative therapies (hysteroscopic resection, laparoscopic repair, abdominal repair, vaginal repair, endometrial ablation, LNG-IUS, or medical management) as well as at least one of the following outcomes: AUB, pain relief, sexual function, quality of life, surgical outcome, anatomic reconstruction, fertility or pregnancy outcome. Of 1,629 publications that were screened, 12 ultimately met inclusion criteria for the review. The studies, 11 of which were peer reviewed and 1 abstract, were published between 1996 and 2013 and reported on a total of 455 women with postcesarean AUB.

Weaknesses of the study

The most poignant statements made by the investigators pertain to the methodologic quality of the included articles. No study met requisite quality criteria. A clear definition of outcomes, including standardized measurements, was lacking in most studies. Most of the studies reviewed did not report CSD measurements, and only one study provided an objective reproducible method of CSD measurement. Few studies reported AUB symptom evaluation methodology, and no study used validated questionnaires. In the majority of studies, methods of posttreatment outcome measurements either were not reported or differed from pretreatment evaluation methods, potentiating verification bias. Because their literature review yielded primarily small case series publications that reported positive effects of interventions, and because of a lack of large RCT and prospective cohort trials, little could be gleaned regarding the viability of treatment interventions for CSD-related AUB.

Only three studies provided sufficient data to be included in a meta-analysis. The number of days of bleeding was reduced with hysteroscopic defect resection by 2 to 4 days in two studies, and in one study, vaginal repair decreased days of bleeding by 4 to 7 days. Only one study with laparoscopic repair compared CSD characteristics before and after surgery. Residual myometrial thickness increased for laparoscopic repair to greater than 8.3 mm; however, it is not known if this will make a clinical difference in the risk of scar dehiscence or improved functionality of the lower uterine segment.

Two studies reported on the laparoscopic repair of scar defects in asymptomatic patients, which is not recommended by these investigators. It is not known what ramifications hysteroscopic resection of the scar will have for the risk of uterine rupture, malplacentation or cervical incompetence for women who conceive after hysteroscopic repair.

Meaningful conclusions are lacking

Despite the high success rates reported by investigators of various surgical intervention case series involving hysteroscopic resection, vaginal repair, or laparoscopic repair, van der Voet and colleagues ultimately state that the methodologies of these studies do not allow meaningful conclusions to be drawn regarding the effectiveness of any of these interventions. Consequently, the authors recommend that the outcomes of their meta-analysis be scrutinized. They also point out that the LNG-IUS has proven benefit for AUB and yet has not been studied in the treatment of AUB associated with a CSD.

They finally propose that women who are symptomatic be treated with oral contraceptives unless immediate fertility is desired, or by expectant management without intervention. While their primary focus was to assess AUB, given the stated shortcomings of the included studies and lack of long-term follow-up, the authors also warn against hysteroscopic, laparoscopic, or vaginal repair for fertility, as the risk to pregnancy or delivery after these therapies is unknown.

CASE RESOLVED

Suspecting a cesarean scar defect, you perform a saline infusion sonography and diagnose a 14 mm x 19 mm anechoic region within the scar, with no other intracavitary abnormalities found. You first reassure the patient that this is a benign finding and inform her why she likely is experiencing this type of bleeding pattern. After an informed discussion with you regarding the risks and benefits of possible surgical or nonsurgical options for management, she chooses to use oral contraceptive pills in a continuous fashion.

CONCLUSION

Consider a history of cesarean section in the evaluation of AUB, and be cognizant of the prevalence of CSD with cesarean delivery and the association of postmenstrual bleeding with CSD.

WHAT THIS EVIDENCE MEANS FOR PRACTICE

• A critical systematic review of available data suggests that there is not enough clinical evidence to support surgical intervention for the treatment of CSD for women symptomatic with AUB.

• Recommended nonhysterectomy treatments for AUB associated with CSD include oral contraceptives or expectant management.

• Surgical treatment should be limited to the research environment in the form of RCT to assess the long-term outcomes of intervention.

• An RCT of the LNG-IUS for the treatment of AUB associated with CSD is needed.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Andrew Brill, MD, Lee Sloan-Garcia, MD, and William Parker, MD, for their thoughtful review of this manuscript.

We want to hear from you!

Share your thoughts on this article or on any topic relevant to ObGyns and women’s health practitioners. Tell us which topics you’d like to see covered in future issues, and what challenges you face in daily practice. We will consider publishing your letter and in a future issue. Send your letter to: obg@frontlinemedcom.com Please include the city and state in which you practice. Stay in touch! Your feedback is important to us!

- Osterman MJK, Martin JA. Primary cesarean delivery rates, by state: Results from the revised birth certificate, 2006-2012. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2014;63(1):1–11.

- Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Osterman MJK, Curtin SC, Mathews TJ. Births: Final data for 2012. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2013;62(9). Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr62/nvsr62_09.pdf. Accessed March 19, 2014.

- Stewart KS, Evans TW. Recurrent bleeding from the lower segment scar – a late complication of Caesarean section. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1975;82(8):682–686.

- Tower AM, Frishman GN. Cesarean scar defects: An underrecognized cause of abnormal uterine bleeding and other gynecologic complications. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2013;20(5):562–572.

- Morris H. Surgical pathology of the lower uterine segment cesarean section scar: Is the scar a source of clinical symptoms? Intl J Gynecol Pathol. 1995;14(1):16–20.

- Gubbini G, Centini G, Nascetti D, et al. Surgical hysteroscopic treatment of cesarean-induced isthmocele in restoring fertility: Prospective study. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2011;18(2):234–237.

- van der Voet LF, Bijde Vaate AM, Veersema S, Brolmann HA, Huirne JA. Long-term complications of caesarean section. The niche in the scar: A prospective cohort study on niche prevalence and its relation to abnormal uterine bleeding. BJOG. 2014;121(2):236–244.

- van der Voet LF, Vervoort AJ, Veersema S, Bijde Vatte AJ, Brolmann HA, Huirne JA. Minimally invasive therapy for gynaecological symptoms related to a niche in the caesarean scar: A systematic review. BJOG. 2014;121(2):145–156.

- Maldjian C, Adam R, Maldjian J, Smith R. MRI appearance of the pelvis in the post cesarean-section patient. Magn Reson Imaging. 1999;17(2):223–227.

- Marotta ML, Donnez J, Squifflet J, Jadoul P, Darii N, Donnez O. Laparoscopic repair of post-Cesarean section uterine scar defects diagnosed in nonpregnant women. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2013;20(3):386–391.

- Munro MG, Critchley HO, Broder MS, Fraser IS; FIGO Working Group on Menstrual Disorders. FIGO classification system (PALM-COIEN) for causes of abnormal uterine bleeding in nongravid women of reproductive age. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2011;113(1):3–13.

CASE: POSTMENSTRUAL BLEEDING, HISTORY OF CESAREAN DELIVERIES

A 36-year-old woman (G3P3) reports prolonged and postmenstrual bleeding. Her cycles are regular, every 28 to 30 days, and are associated with ovulatory symptoms. She bleeds for 8 to 10 days with each cycle, having heavy bleeding on cycle day 2 requiring use of super tampons every 3 hours. Beginning on day 5 of the cycle, the blood becomes much darker and scant requiring a small pad, which she changes twice daily. Often, she experiences dark bleeding with physical activity—specifically, running—usually several days after her cycle has ended. She is otherwise healthy and uses no medications. She uses condoms for contraception. She has had a prior vaginal delivery followed by two cesarean sections. Physical examination is normal.

What is causing this patient’s abnormal bleeding pattern?

From 1996 to 2009, the total US cesarean delivery rate increased steadily from 20.7% to 32.9% and has remained stable at 32.8% through 2012.1 With 3,952,841 registered births in 2012, the number of operative procedures performed annually approximates 1.3 million.2 This means, potentially, that one-third of pregnant American women will undergo cesarean delivery annually, translating into an increasing prevalence of long-term sequelae of this surgery.

An increasingly recognized etiology of AUB

One long-term complication of cesarean delivery, not often discussed, is the presence of a defect within the uterine scar that is directly associated with a type of abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB) referred to as postmenstrual bleeding. Stewart first reported this post–cesarean delivery phenomenon in 1975.3 It is postulated that the cesarean scar defect (CSD)4 forms a pocket, which holds the menstrual effluent, allowing bleeding to occur after regular menstrual cycle bleeding has concluded. Often, remnant menstrual blood is extruded slowly over several days, and is generally dark brown, indicating old blood. Physical activity sometimes can initiate expulsion of the old blood even after the regular cycle has ceased (FIGURE 1).