User login

What is your diagnosis?

Answer: Infectious gastroparesis secondary to acute hepatitis A infection.

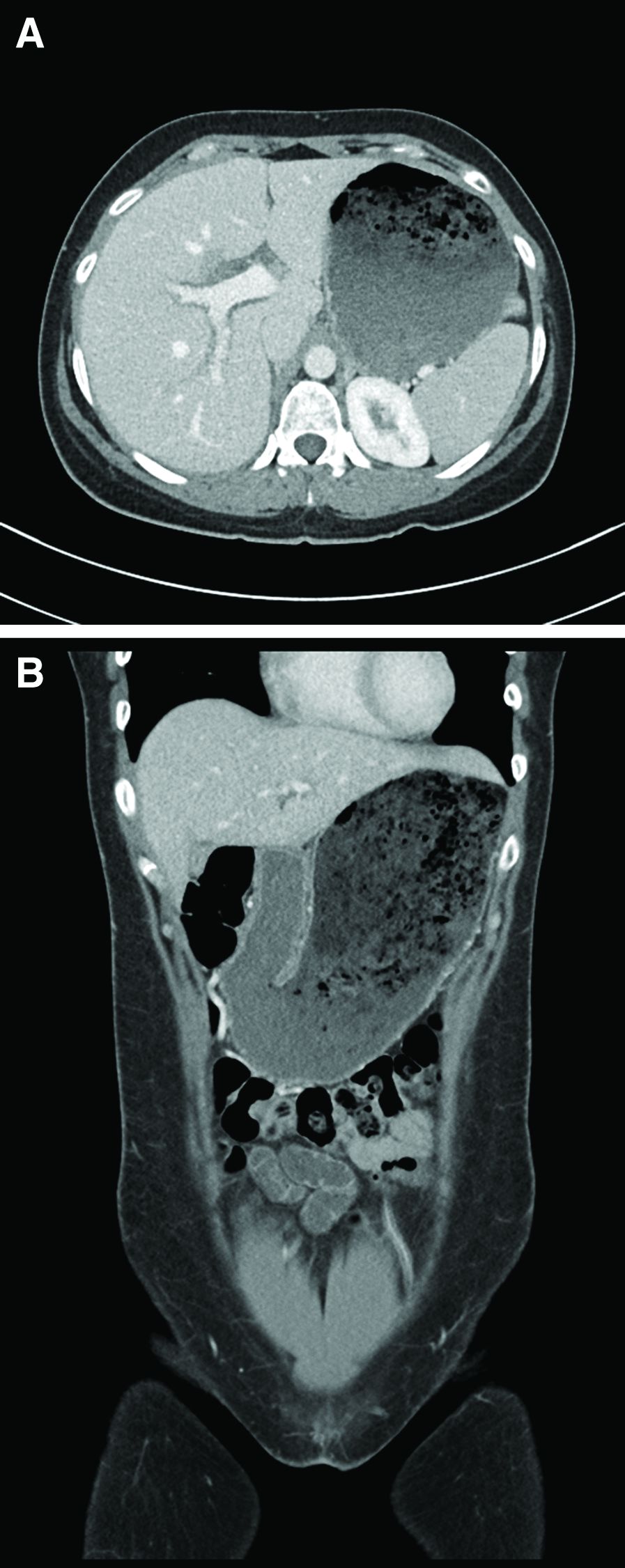

A computed tomography scan of the abdomen/pelvis demonstrated marked gastric distention without obvious obstructing mass and normal caliber small bowel and colon. Additional laboratory workup revealed a positive hepatitis A IgM antibody. Hepatitis B surface antigen and core IgM antibody were negative, as was the hepatitis C virus antibody. Human immunodeficiency virus antigen and antibody were negative. An esophagogastroduodenoscopy was performed that showed a large amount of food in a dilated and atonic stomach.

With conservative treatment, the patient’s liver enzymes trended down over the next 2 days to alanine aminotransferase 993 U/L, aspartate aminotransferase 244 U/L, and direct bilirubin 3.8 mg/dL. At the time of discharge, she was tolerating soft foods without any difficulty. She was educated on taking appropriate precautions to avoid transmitting the hepatitis A infection to others. Her risk factor for hepatitis A was recent incarceration.

Here we highlight a rare case of infectious gastroparesis secondary to hepatitis A infection. Hepatitis A virus is a small, nonenveloped, RNA-containing virus.1 It typically presents with a self-limited illness with liver failure occurring in rare cases. Common presenting symptoms including nausea, vomiting, jaundice, fever, diarrhea, and abdominal pain.Laboratory abnormalities include elevations in the serum aminotransferases, alkaline phosphatase, and total bilirubin.2 The diagnosis is confirmed with a positive hepatitis A IgM antibody. The most common route of transmission is the fecal-oral route such as through consumption of contaminated water and food or from person-to-person contact.1 Individuals can develop immunity to the virus either from prior infection or vaccination.

Gastroparesis refers to delayed emptying of gastric contents when mechanical obstruction has been ruled out. Common causes of gastroparesis include diabetes mellitus, medications, postoperative complications, and infections. Infectious gastroparesis may present acutely after a viral prodrome and symptoms may be severe and slow to resolve.3

References

1. Lemon SM. N Engl J Med. 1985 Oct 24;313(17):1059-67.

2. Tong MJ et al. J Infect Dis. 1995 Mar;171 Suppl 1:S15-8.

3. Bityutskiy LP. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997 Sep;92(9):1501-4.

Answer: Infectious gastroparesis secondary to acute hepatitis A infection.

A computed tomography scan of the abdomen/pelvis demonstrated marked gastric distention without obvious obstructing mass and normal caliber small bowel and colon. Additional laboratory workup revealed a positive hepatitis A IgM antibody. Hepatitis B surface antigen and core IgM antibody were negative, as was the hepatitis C virus antibody. Human immunodeficiency virus antigen and antibody were negative. An esophagogastroduodenoscopy was performed that showed a large amount of food in a dilated and atonic stomach.

With conservative treatment, the patient’s liver enzymes trended down over the next 2 days to alanine aminotransferase 993 U/L, aspartate aminotransferase 244 U/L, and direct bilirubin 3.8 mg/dL. At the time of discharge, she was tolerating soft foods without any difficulty. She was educated on taking appropriate precautions to avoid transmitting the hepatitis A infection to others. Her risk factor for hepatitis A was recent incarceration.

Here we highlight a rare case of infectious gastroparesis secondary to hepatitis A infection. Hepatitis A virus is a small, nonenveloped, RNA-containing virus.1 It typically presents with a self-limited illness with liver failure occurring in rare cases. Common presenting symptoms including nausea, vomiting, jaundice, fever, diarrhea, and abdominal pain.Laboratory abnormalities include elevations in the serum aminotransferases, alkaline phosphatase, and total bilirubin.2 The diagnosis is confirmed with a positive hepatitis A IgM antibody. The most common route of transmission is the fecal-oral route such as through consumption of contaminated water and food or from person-to-person contact.1 Individuals can develop immunity to the virus either from prior infection or vaccination.

Gastroparesis refers to delayed emptying of gastric contents when mechanical obstruction has been ruled out. Common causes of gastroparesis include diabetes mellitus, medications, postoperative complications, and infections. Infectious gastroparesis may present acutely after a viral prodrome and symptoms may be severe and slow to resolve.3

References

1. Lemon SM. N Engl J Med. 1985 Oct 24;313(17):1059-67.

2. Tong MJ et al. J Infect Dis. 1995 Mar;171 Suppl 1:S15-8.

3. Bityutskiy LP. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997 Sep;92(9):1501-4.

Answer: Infectious gastroparesis secondary to acute hepatitis A infection.

A computed tomography scan of the abdomen/pelvis demonstrated marked gastric distention without obvious obstructing mass and normal caliber small bowel and colon. Additional laboratory workup revealed a positive hepatitis A IgM antibody. Hepatitis B surface antigen and core IgM antibody were negative, as was the hepatitis C virus antibody. Human immunodeficiency virus antigen and antibody were negative. An esophagogastroduodenoscopy was performed that showed a large amount of food in a dilated and atonic stomach.

With conservative treatment, the patient’s liver enzymes trended down over the next 2 days to alanine aminotransferase 993 U/L, aspartate aminotransferase 244 U/L, and direct bilirubin 3.8 mg/dL. At the time of discharge, she was tolerating soft foods without any difficulty. She was educated on taking appropriate precautions to avoid transmitting the hepatitis A infection to others. Her risk factor for hepatitis A was recent incarceration.

Here we highlight a rare case of infectious gastroparesis secondary to hepatitis A infection. Hepatitis A virus is a small, nonenveloped, RNA-containing virus.1 It typically presents with a self-limited illness with liver failure occurring in rare cases. Common presenting symptoms including nausea, vomiting, jaundice, fever, diarrhea, and abdominal pain.Laboratory abnormalities include elevations in the serum aminotransferases, alkaline phosphatase, and total bilirubin.2 The diagnosis is confirmed with a positive hepatitis A IgM antibody. The most common route of transmission is the fecal-oral route such as through consumption of contaminated water and food or from person-to-person contact.1 Individuals can develop immunity to the virus either from prior infection or vaccination.

Gastroparesis refers to delayed emptying of gastric contents when mechanical obstruction has been ruled out. Common causes of gastroparesis include diabetes mellitus, medications, postoperative complications, and infections. Infectious gastroparesis may present acutely after a viral prodrome and symptoms may be severe and slow to resolve.3

References

1. Lemon SM. N Engl J Med. 1985 Oct 24;313(17):1059-67.

2. Tong MJ et al. J Infect Dis. 1995 Mar;171 Suppl 1:S15-8.

3. Bityutskiy LP. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997 Sep;92(9):1501-4.

A 33-year-old woman presented with a 10-day history of painless jaundice. During this time, she also noted decreased appetite, malaise, and pruritus. On occasion, she would have heartburn and belching that would improve with an antacid. She denied any right upper quadrant pain and weight loss. She was not currently taking any medications, including acetaminophen. She had a past medical history of methamphetamine use in recent remission. She had recently been incarcerated for about 1 month.

What is the most likely etiology of the patient's condition?

Microscopic colitis: A common, yet often overlooked, cause of chronic diarrhea

Microscopic colitis is an inflammatory disease of the colon and a frequent cause of chronic or recurrent watery diarrhea, particularly in older persons. MC consists of two subtypes, collagenous colitis (CC) and lymphocytic colitis (LC). While the primary symptom is diarrhea, other signs and symptoms such as abdominal pain, weight loss, and dehydration or electrolyte abnormalities may also be present depending on disease severity.1 In MC, the colonic mucosa usually appears normal on colonoscopy, and the diagnosis is made by histologic findings of intraepithelial lymphocytosis with (CC) or without (LC) a prominent subepithelial collagen band. The management approaches to CC and LC are similar and should be directed based on the severity of symptoms.2 We review the epidemiology, risk factors, pathophysiology, diagnosis, and clinical management for this condition, as well as novel therapeutic approaches.

Epidemiology

Although the incidence of MC increased in the late twentieth century, more recently, it has stabilized with an estimated incidence varying from 1 to 25 per 100,000 person-years.3-5 A recent meta-analysis revealed a pooled incidence of 4.85 per 100,000 persons for LC and 4.14 per 100,000 persons for CC.6 Proposed explanations for the rising incidence in the late twentieth century include improved clinical awareness of the disease, possible increased use of drugs associated with MC, and increased performance of diagnostic colonoscopies for chronic diarrhea. Since MC is now well-recognized, the recent plateau in incidence rates may reflect decreased detection bias.

The prevalence of MC ranges from 10%-20% in patients undergoing colonoscopy for chronic watery diarrhea.6,7 The prevalence of LC is approximately 63.1 cases per 100,000 person-years and, for CC, is 49.2 cases per 100,000 person-years.6-8 Recent studies have demonstrated increasing prevalence of MC likely resulting from an aging population.9,10

Risk stratification

Female gender, increasing age, concomitant autoimmune disease, and the use of certain drugs, including NSAIDs, proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), statins, and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), have been associated with an increased risk of MC.11,12 Autoimmune disorders, including celiac disease (CD), rheumatoid arthritis, hypothyroidism, and hyperthyroidism, are more common in patients with MC. The association with CD, in particular, is clinically important, as CD is associated with a 50-70 times greater risk of MC, and 2%-9% of patients with MC have CD.13,14

Several medications have been associated with MC. In a British multicenter prospective study, MC was associated with the use of NSAIDs, PPIs, and SSRIs;15 however, recent studies have questioned the association of MC with some of these medications, which might worsen diarrhea but not actually cause MC.16

An additional risk factor for MC is smoking. A recent meta-analysis demonstrated that current and former smokers had an increased risk of MC (odds ratio, 2.99; 95% confidence interval, 2.15-4.15 and OR, 1.63; 95% CI, 1.37-1.94, respectively), compared with nonsmokers.17 Smokers develop MC at a younger age, and smoking is associated with increased disease severity and decreased likelihood of attaining remission.18,19

Pathogenesis

The pathogenesis of MC remains largely unknown, although there are several hypotheses. The leading proposed mechanisms include reaction to luminal antigens, dysregulated collagen metabolism, genetic predisposition, autoimmunity, and bile acid malabsorption.

MC may be caused by abnormal epithelial barrier function, leading to increased permeability and reaction to luminal antigens, including dietary antigens, certain drugs, and bacterial products, 20,21 which themselves lead to the immune dysregulation and intestinal inflammation seen in MC. This mechanism may explain the association of several drugs with MC. Histological changes resembling LC are reported in patients with CD who consume gluten; however, large population-based studies have not found specific dietary associations with the development of MC.22

Another potential mechanism of MC is dysregulated collagen deposition. Collagen accumulation in the subepithelial layer in CC may result from increased levels of fibroblast growth factor, transforming growth factor–beta and vascular endothelial growth factor.23 Nonetheless, studies have not found an association between the severity of diarrhea in patients with CC and the thickness of the subepithelial collagen band.

Thirdly, autoimmunity and genetic predisposition have been postulated in the pathogenesis of MC. As previously discussed, MC is associated with several autoimmune diseases and predominantly occurs in women, a distinctive feature of autoimmune disorders. Several studies have demonstrated an association between MC and HLA-DQ2 and -DQ3 haplotypes,24 as well as potential polymorphisms in the serotonin transporter gene promoter.25 It is important to note, however, that only a few familial cases of MC have been reported to date.26

Lastly, bile acid malabsorption may play a role in the etiology of MC. Histologic findings of inflammation, along with villous atrophy and collagen deposition, have been reported in the ileum of patients with MC;27,28 however, because patients with MC without bile acid malabsorption may also respond to bile acid binders such as cholestyramine, these findings unlikely to be the sole mechanism explaining the development of the disease.

Despite the different proposed mechanisms for the pathogenesis of MC, no definite conclusions can be drawn because of the limited size of these studies and their often conflicting results.

Clinical features

Clinicians should suspect MC in patients with chronic or recurrent watery diarrhea, particularly in older persons. Other risk factors include female gender, use of certain culprit medications, smoking, and presence of other autoimmune diseases. The clinical manifestations of MC subtypes LC and CC are similar with no significant clinical differences.1,2 In addition to diarrhea, patients with MC may have abdominal pain, fatigue, and dehydration or electrolyte abnormalities depending on disease severity. Patients may also present with fecal urgency, incontinence, and nocturnal stools. Quality of life is often reduced in these patients, predominantly in those with severe or refractory symptoms.29,30 The natural course of MC is highly variable, with some patients achieving spontaneous resolution after one episode and others developing chronic symptoms.

Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of chronic watery diarrhea is broad and includes malabsorption/maldigestion, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), irritable bowel syndrome, and medication side effects. In addition, although gastrointestinal infections typically cause acute or subacute diarrhea, some can present with chronic diarrhea. Malabsorption/maldigestion may occur because of CD, lactose intolerance, and pancreatic insufficiency, among other conditions. A thorough history, regarding recent antibiotic and medication use, travel, and immunosuppression, should be obtained in patients with chronic diarrhea. Additionally, laboratory and endoscopic evaluation with random biopsies of the colon can further help differentiate these diseases from MC. A few studies suggest fecal calprotectin may be used to differentiate MC from other noninflammatory conditions such as irritable bowel syndrome, as well as to monitor disease activity. This test is not expected to distinguish MC from other inflammatory causes of diarrhea, such as IBD, and therefore, its role in clinical practice is uncertain.31

The diagnosis of MC is made by biopsy of the colonic mucosa demonstrating characteristic pathologic features.32 Unlike in diseases such as Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis, the colon usually appears normal in MC, although mild nonspecific changes, such as erythema or edema, may be visualized. There is no consensus on the ideal location to obtain biopsies for MC or whether biopsies from both the left and the right colon are required.2,33 The procedure of choice for the diagnosis of MC is colonoscopy with random biopsies taken throughout the colon. More limited evaluation by flexible sigmoidoscopy with biopsies may miss cases of MC as inflammation and collagen thickening are not necessarily uniform throughout the colon; however, in a patient that has undergone a recent colonoscopy for colon cancer screening without colon biopsies, a flexible sigmoidoscopy may be a reasonable next test for evaluation of MC, provided biopsies are obtained above the rectosigmoid colon.34

The MC subtypes are differentiated based on histology. The hallmark of LC is less than 20 intraepithelial lymphocytes per 100 surface epithelial cells (normal, less than 5) (Figure 1A). CC is characterized by a thickened subepithelial collagen band greater than 7-10 micrometers (normal, less than 5) (Figure 1B). For a subgroup of patients with milder abnormalities that do not meet these histological criteria, the terms “microscopic colitis, not otherwise specified” or “microscopic colitis, incomplete” may be used.35 These patients often respond to standard treatments for MC. There is an additional subset of patients with biopsy demonstrating features of both CC and LC simultaneously, as well as patients transitioning from one MC subtype to another over time.32,35

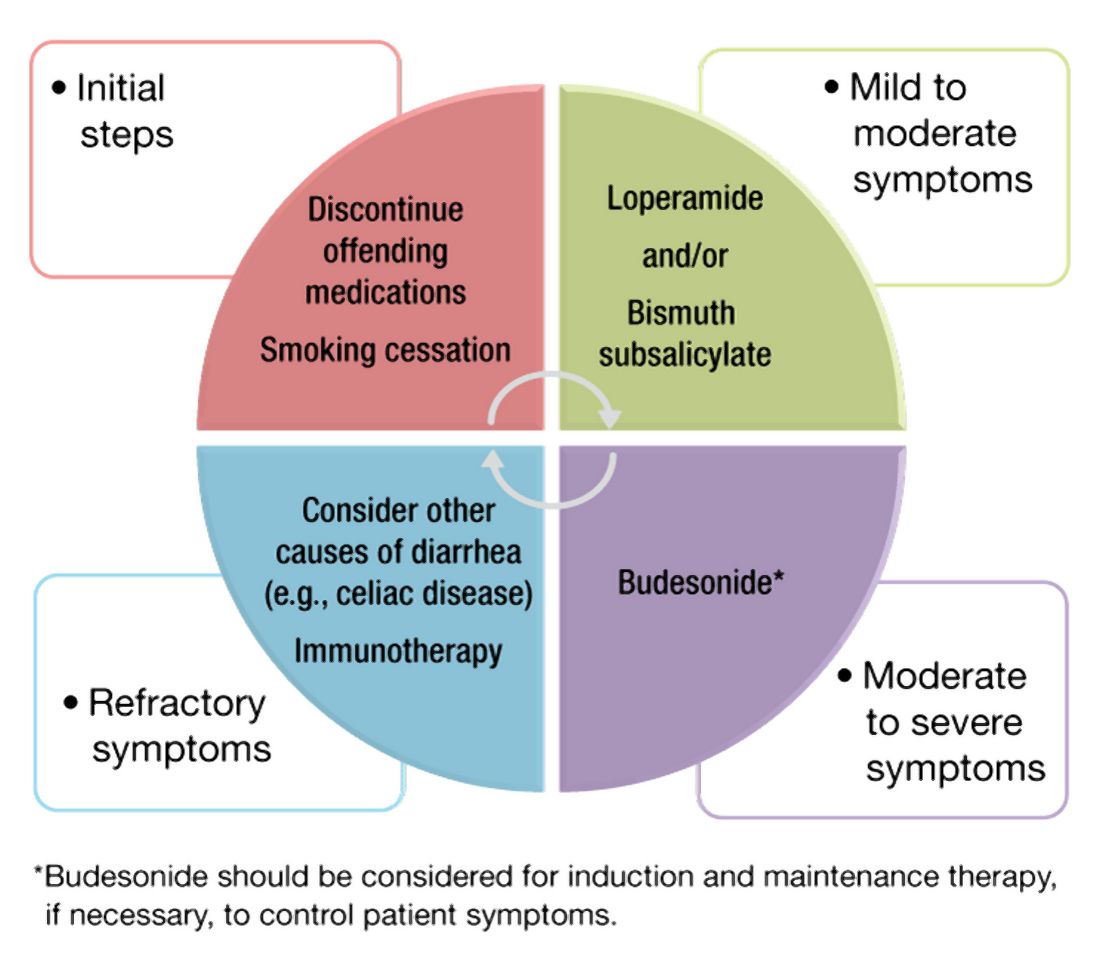

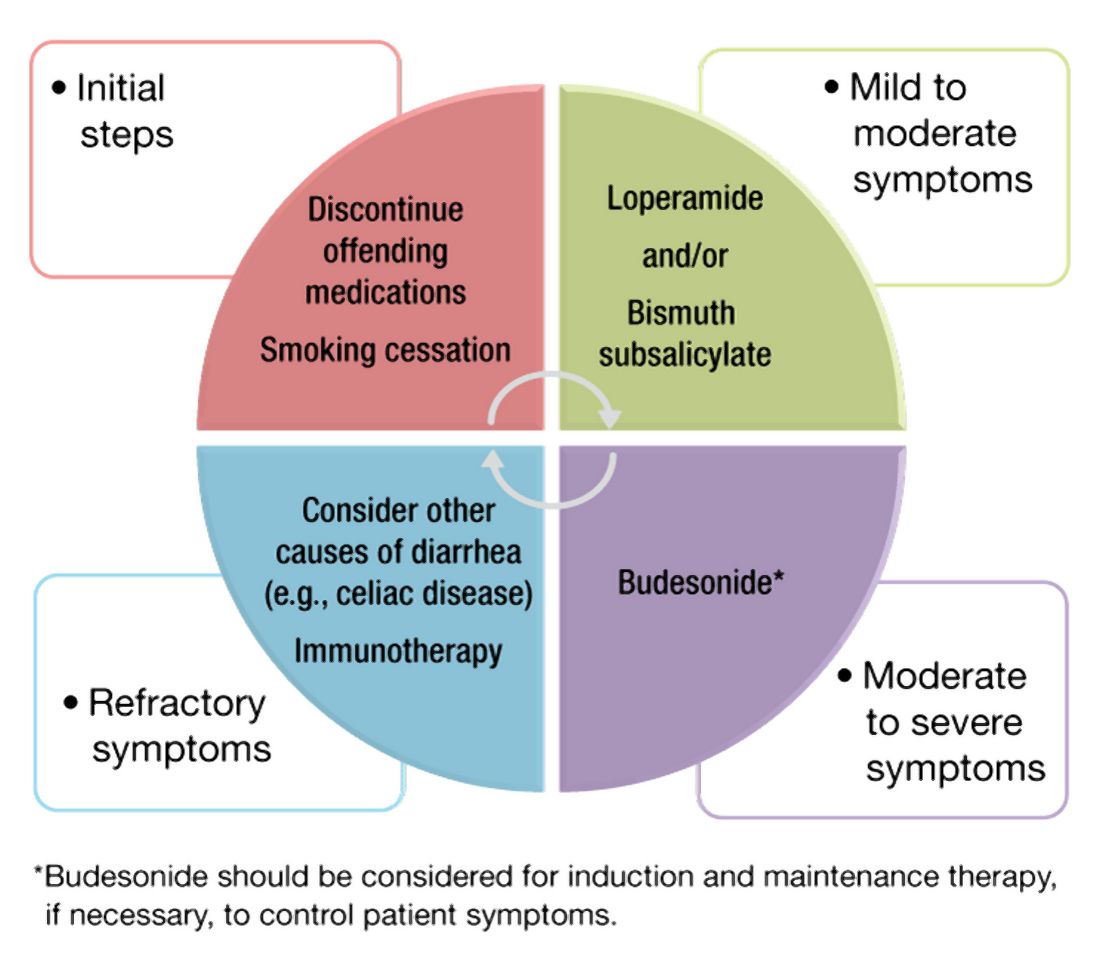

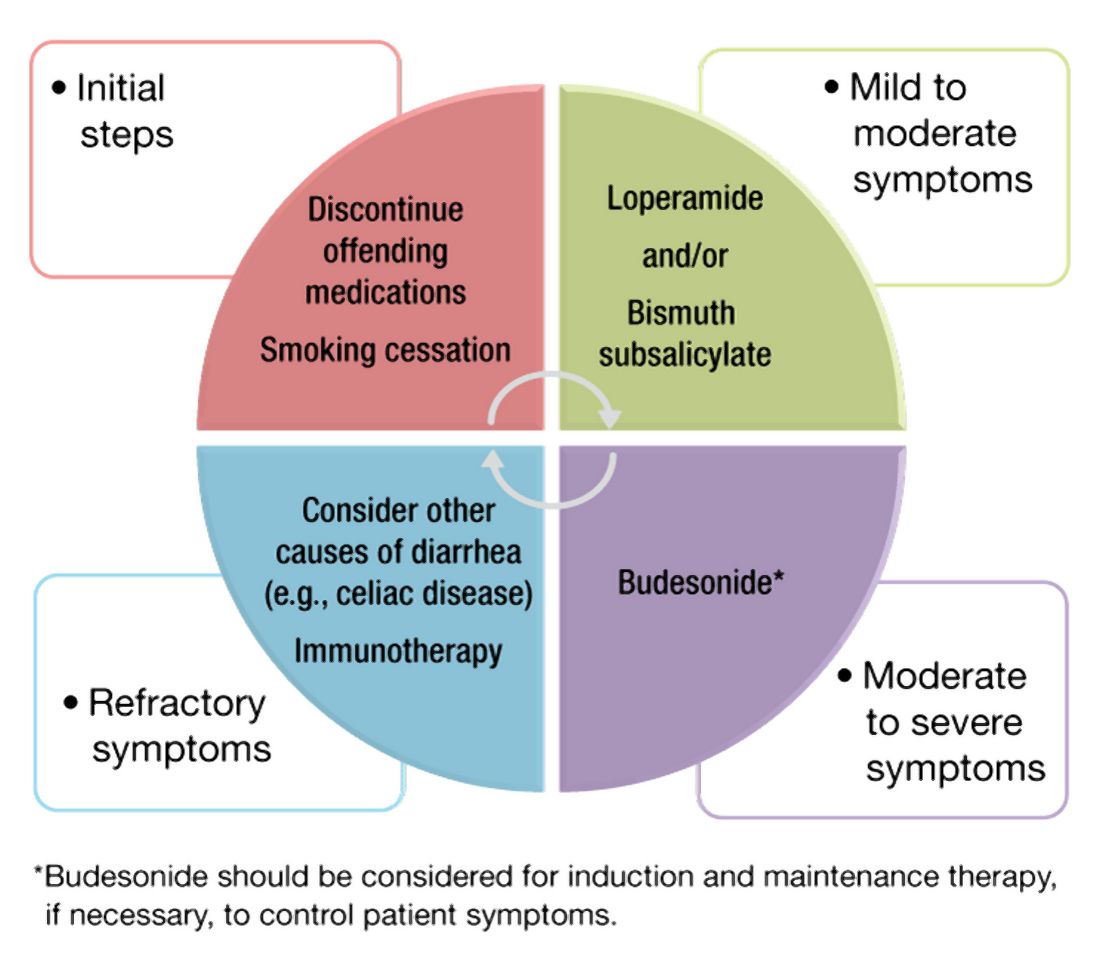

Management approach

The first step in management of patients with MC includes stopping culprit medications if there is a temporal relationship between the initiation of the medication and the onset of diarrhea, as well as encouraging smoking cessation. These steps alone, however, are unlikely to achieve clinical remission in most patients. A stepwise pharmacological approach is used in the management of MC based on disease severity (Figure 2). For patients with mild symptoms, antidiarrheal medications, such as loperamide, may be helpful.36 Long-term use of loperamide at therapeutic doses no greater than 16 mg daily appears to be safe if required to maintain symptom response. For those with persistent symptoms despite antidiarrheal medications, bismuth subsalicylate at three 262 mg tablets three times daily for 6-8 weeks can be considered. Long-term use of bismuth subsalicylate is not advised, especially at this dose, because of possible neurotoxicity.37

For patients refractory to the above treatments or those with moderate-to-severe symptoms, an 8-week course of budesonide at 9 mg daily is the first-line treatment.38 The dose was tapered before discontinuation in some studies but not in others. Both strategies appear effective. A recent meta-analysis of nine randomized trials demonstrated pooled ORs of 7.34 (95% CI, 4.08-13.19) and 8.35 (95% CI, 4.14-16.85) for response to budesonide induction and maintenance, respectively.39

Cholestyramine is another medication considered in the management of MC and warrants further investigation. To date, no randomized clinical trials have been conducted to evaluate bile acid sequestrants in MC, but they should be considered before placing patients on immunosuppressive medications. Some providers use mesalamine in this setting, although mesalamine is inferior to budesonide in the induction of clinical remission in MC.40

Despite high rates of response to budesonide, relapse after discontinuation is frequent (60%-80%), and time to relapse is variable41,42 The American Gastroenterological Association recommends budesonide for maintenance of remission in patients with recurrence following discontinuation of induction therapy. The lowest effective dose that maintains resolution of symptoms should be prescribed, ideally at 6 mg daily or lower.38 Although budesonide has a greater first-pass metabolism, compared with other glucocorticoids, patients should be monitored for possible side effects including hypertension, diabetes, and osteoporosis, as well as ophthalmologic disease, including cataracts and glaucoma.

For those who are intolerant to budesonide or have refractory symptoms, concomitant disorders such as CD that may be contributing to symptoms must be excluded. Immunosuppressive medications – such as thiopurines and biologic agents, including tumor necrosis factor–alpha inhibitors or vedolizumab – may be considered in refractory cases.43,44 Of note, there are limited studies evaluating the use of these medications for MC. Lastly, surgeries including ileostomy with or without colectomy have been performed in the most severe cases for resistant disease that has failed numerous pharmacological therapies.45

Patients should be counseled that, while symptoms from MC can be quite bothersome and disabling, there appears to be a normal life expectancy and no association between MC and colon cancer, unlike with other inflammatory conditions of the colon such as IBD.46,47

Conclusion and future outlook

As a common cause of chronic watery diarrhea, MC will be commonly encountered in primary care and gastroenterology practices. The diagnosis should be suspected in patients presenting with chronic or recurrent watery diarrhea, especially with female gender, autoimmune disease, and increasing age. The management of MC requires an algorithmic approach directed by symptom severity, with a subgroup of patients requiring maintenance therapy for relapsing symptoms. The care of patients with MC will continue to evolve in the future. Further work is needed to explore long-term safety outcomes with budesonide and the role of immunomodulators and newer biologic agents for patients with complex, refractory disease.

Dr. Tome is with the department of internal medicine at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn. Dr. Kamboj, and Dr. Pardi are with the division of gastroenterology and hepatology at the Mayo Clinic. Dr. Pardi has grant funding from Pfizer, Vedanta, Seres, Finch, Applied Molecular Transport, and Takeda and has consulted for Vedanta and Otsuka. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

References

1. Nyhlin N et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;39:963-72.

2. Miehlke S et al. United European Gastroenterol J. 2020;20-8.

3. Pardi DS et al. Gut. 2007;56:504-8.

4. Fernández-Bañares F et al. J Crohn’s Colitis.2016;10(7):805-11.

5. Gentile NM et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12(5):838-42.

6. Tong J et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:265-76.

7. Olesen M et al. Gut. 2004;53(3):346-50.

8. Bergman D et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2019;49(11):1395-400.

9. Guagnozzi D et al. Dig Liver Dis. 2012;44(5):384-8.

10. Münch A et al. J Crohns Colitis. 2012;6(9):932-45.

11. Macaigne G et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014; 09(9):1461-70.

12. Verhaegh BP et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016;43(9):1004-13.

13. Stewart M et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33(12):1340-9.

14. Green PHR et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7(11):1210-6.

15. Masclee GM et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:749-59.

16. Zylberberg H et al. Ailment Pharmacol Ther. 2021 Jun;53(11)1209-15.

17. Jaruvongvanich V et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2019;25(4):672-8.

18. Fernández-Bañares F et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013; 19(7):1470-6.

19. Yen EF et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18(10):1835-41.

20. Barmeyer C et al. J Gastroenterol. 2017;52(10):1090-100.

21. Morgan DM et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18(4):984-6.

22. Larsson JK et al. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2016;70:1309-17.

23. Madisch A et al.. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17(11):2295-8.

24. Stahl E et al. Gastroenterology. 2020;159(2):549-61.

25. Sikander A et al. Dig Dis Sci. 2015; 60:887-94.

26. Abdo AA et al. Can J Gastroenterol. 2001;15(5):341-3.

27. Fernandez-Bañares F et al. Dig Dis Sci.2001;46(10):2231-8.

28. Lyutakov I et al. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;1;33(3):380-7.

29. Hjortswang H et al. Dig Liver Dis. 2011 Feb;43(2):102-9.

30. Cotter TG= et al. Gut. 2018;67(3):441-6.

31. Von Arnim U et al. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2016;9:97-103.

32. Langner C et al. Histopathology. 2015;66:613-26.

33. ASGE Standards of Practice Committee and Sharaf RN et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;78:216-24.

34. Macaigne G et al. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2017;41(3):333-40.

35. Bjørnbak C et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;34(10):1225-34.

36. Pardi DS et al. Gastroenterology. 2016;150(1):247-74.

37. Masannat Y and Nazer E. West Virginia Med J. 2013;109(3):32-4.

38. Nguyen GC et al. Gastroenterology. 2016; 150(1):242-6.

39. Sebastian S et al. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019 Aug;31(8):919-27.

40. Miehlke S et al. Gastroenterology. 2014;146(5):1222-30.

41. Gentile NM et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:256-9.

42. Münch A et al. Gut. 2016; 65(1):47-56.

43. Cotter TG et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017; 46(2):169-74.

44. Esteve M et al. J Crohns Colitis. 2011;5(6):612-8.

45. Cottreau J et al. Clin J Gastroenterol. 2016;9:140-4.

46. Kamboj AK et al. Program No. P1876. ACG 2018 Annual Scientific Meeting Abstracts. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: American College of Gastroenterology.

47. Yen EF et al. Dig Dis Sci. 2012;57:161-9.

Microscopic colitis is an inflammatory disease of the colon and a frequent cause of chronic or recurrent watery diarrhea, particularly in older persons. MC consists of two subtypes, collagenous colitis (CC) and lymphocytic colitis (LC). While the primary symptom is diarrhea, other signs and symptoms such as abdominal pain, weight loss, and dehydration or electrolyte abnormalities may also be present depending on disease severity.1 In MC, the colonic mucosa usually appears normal on colonoscopy, and the diagnosis is made by histologic findings of intraepithelial lymphocytosis with (CC) or without (LC) a prominent subepithelial collagen band. The management approaches to CC and LC are similar and should be directed based on the severity of symptoms.2 We review the epidemiology, risk factors, pathophysiology, diagnosis, and clinical management for this condition, as well as novel therapeutic approaches.

Epidemiology

Although the incidence of MC increased in the late twentieth century, more recently, it has stabilized with an estimated incidence varying from 1 to 25 per 100,000 person-years.3-5 A recent meta-analysis revealed a pooled incidence of 4.85 per 100,000 persons for LC and 4.14 per 100,000 persons for CC.6 Proposed explanations for the rising incidence in the late twentieth century include improved clinical awareness of the disease, possible increased use of drugs associated with MC, and increased performance of diagnostic colonoscopies for chronic diarrhea. Since MC is now well-recognized, the recent plateau in incidence rates may reflect decreased detection bias.

The prevalence of MC ranges from 10%-20% in patients undergoing colonoscopy for chronic watery diarrhea.6,7 The prevalence of LC is approximately 63.1 cases per 100,000 person-years and, for CC, is 49.2 cases per 100,000 person-years.6-8 Recent studies have demonstrated increasing prevalence of MC likely resulting from an aging population.9,10

Risk stratification

Female gender, increasing age, concomitant autoimmune disease, and the use of certain drugs, including NSAIDs, proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), statins, and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), have been associated with an increased risk of MC.11,12 Autoimmune disorders, including celiac disease (CD), rheumatoid arthritis, hypothyroidism, and hyperthyroidism, are more common in patients with MC. The association with CD, in particular, is clinically important, as CD is associated with a 50-70 times greater risk of MC, and 2%-9% of patients with MC have CD.13,14

Several medications have been associated with MC. In a British multicenter prospective study, MC was associated with the use of NSAIDs, PPIs, and SSRIs;15 however, recent studies have questioned the association of MC with some of these medications, which might worsen diarrhea but not actually cause MC.16

An additional risk factor for MC is smoking. A recent meta-analysis demonstrated that current and former smokers had an increased risk of MC (odds ratio, 2.99; 95% confidence interval, 2.15-4.15 and OR, 1.63; 95% CI, 1.37-1.94, respectively), compared with nonsmokers.17 Smokers develop MC at a younger age, and smoking is associated with increased disease severity and decreased likelihood of attaining remission.18,19

Pathogenesis

The pathogenesis of MC remains largely unknown, although there are several hypotheses. The leading proposed mechanisms include reaction to luminal antigens, dysregulated collagen metabolism, genetic predisposition, autoimmunity, and bile acid malabsorption.

MC may be caused by abnormal epithelial barrier function, leading to increased permeability and reaction to luminal antigens, including dietary antigens, certain drugs, and bacterial products, 20,21 which themselves lead to the immune dysregulation and intestinal inflammation seen in MC. This mechanism may explain the association of several drugs with MC. Histological changes resembling LC are reported in patients with CD who consume gluten; however, large population-based studies have not found specific dietary associations with the development of MC.22

Another potential mechanism of MC is dysregulated collagen deposition. Collagen accumulation in the subepithelial layer in CC may result from increased levels of fibroblast growth factor, transforming growth factor–beta and vascular endothelial growth factor.23 Nonetheless, studies have not found an association between the severity of diarrhea in patients with CC and the thickness of the subepithelial collagen band.

Thirdly, autoimmunity and genetic predisposition have been postulated in the pathogenesis of MC. As previously discussed, MC is associated with several autoimmune diseases and predominantly occurs in women, a distinctive feature of autoimmune disorders. Several studies have demonstrated an association between MC and HLA-DQ2 and -DQ3 haplotypes,24 as well as potential polymorphisms in the serotonin transporter gene promoter.25 It is important to note, however, that only a few familial cases of MC have been reported to date.26

Lastly, bile acid malabsorption may play a role in the etiology of MC. Histologic findings of inflammation, along with villous atrophy and collagen deposition, have been reported in the ileum of patients with MC;27,28 however, because patients with MC without bile acid malabsorption may also respond to bile acid binders such as cholestyramine, these findings unlikely to be the sole mechanism explaining the development of the disease.

Despite the different proposed mechanisms for the pathogenesis of MC, no definite conclusions can be drawn because of the limited size of these studies and their often conflicting results.

Clinical features

Clinicians should suspect MC in patients with chronic or recurrent watery diarrhea, particularly in older persons. Other risk factors include female gender, use of certain culprit medications, smoking, and presence of other autoimmune diseases. The clinical manifestations of MC subtypes LC and CC are similar with no significant clinical differences.1,2 In addition to diarrhea, patients with MC may have abdominal pain, fatigue, and dehydration or electrolyte abnormalities depending on disease severity. Patients may also present with fecal urgency, incontinence, and nocturnal stools. Quality of life is often reduced in these patients, predominantly in those with severe or refractory symptoms.29,30 The natural course of MC is highly variable, with some patients achieving spontaneous resolution after one episode and others developing chronic symptoms.

Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of chronic watery diarrhea is broad and includes malabsorption/maldigestion, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), irritable bowel syndrome, and medication side effects. In addition, although gastrointestinal infections typically cause acute or subacute diarrhea, some can present with chronic diarrhea. Malabsorption/maldigestion may occur because of CD, lactose intolerance, and pancreatic insufficiency, among other conditions. A thorough history, regarding recent antibiotic and medication use, travel, and immunosuppression, should be obtained in patients with chronic diarrhea. Additionally, laboratory and endoscopic evaluation with random biopsies of the colon can further help differentiate these diseases from MC. A few studies suggest fecal calprotectin may be used to differentiate MC from other noninflammatory conditions such as irritable bowel syndrome, as well as to monitor disease activity. This test is not expected to distinguish MC from other inflammatory causes of diarrhea, such as IBD, and therefore, its role in clinical practice is uncertain.31

The diagnosis of MC is made by biopsy of the colonic mucosa demonstrating characteristic pathologic features.32 Unlike in diseases such as Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis, the colon usually appears normal in MC, although mild nonspecific changes, such as erythema or edema, may be visualized. There is no consensus on the ideal location to obtain biopsies for MC or whether biopsies from both the left and the right colon are required.2,33 The procedure of choice for the diagnosis of MC is colonoscopy with random biopsies taken throughout the colon. More limited evaluation by flexible sigmoidoscopy with biopsies may miss cases of MC as inflammation and collagen thickening are not necessarily uniform throughout the colon; however, in a patient that has undergone a recent colonoscopy for colon cancer screening without colon biopsies, a flexible sigmoidoscopy may be a reasonable next test for evaluation of MC, provided biopsies are obtained above the rectosigmoid colon.34

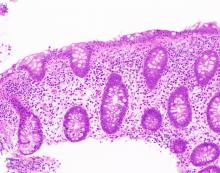

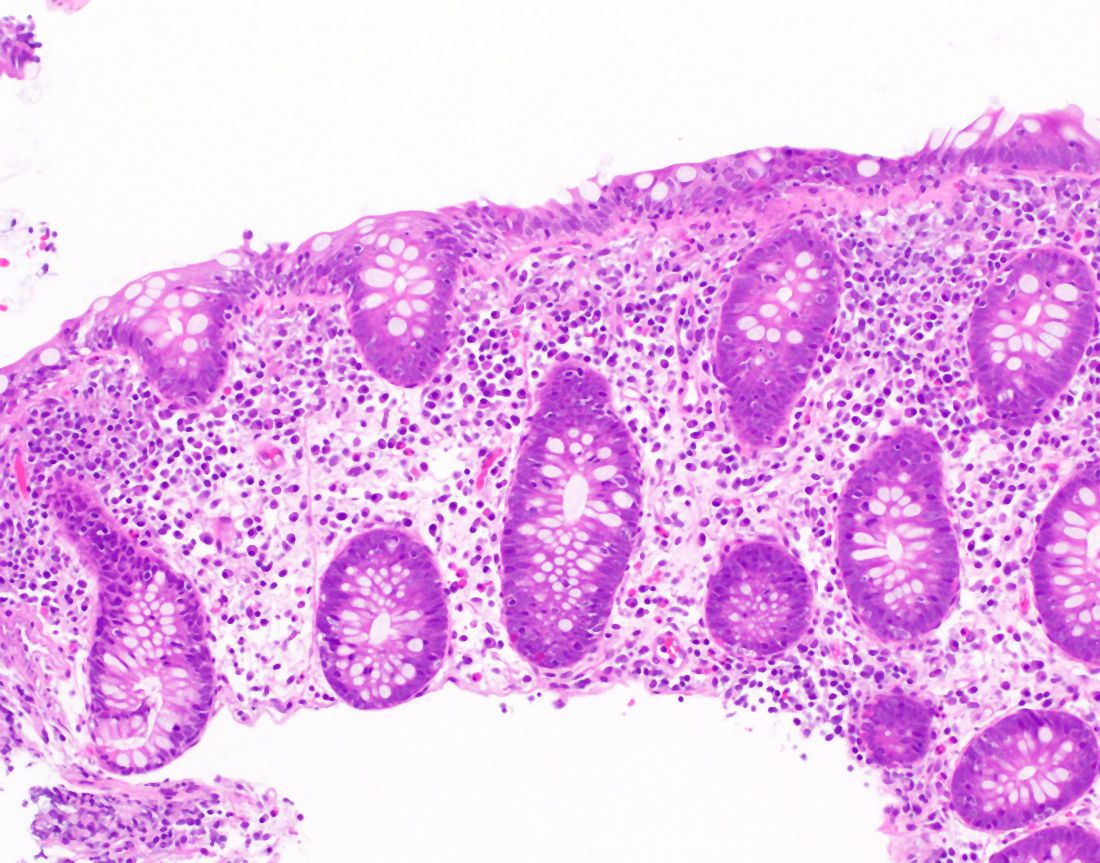

The MC subtypes are differentiated based on histology. The hallmark of LC is less than 20 intraepithelial lymphocytes per 100 surface epithelial cells (normal, less than 5) (Figure 1A). CC is characterized by a thickened subepithelial collagen band greater than 7-10 micrometers (normal, less than 5) (Figure 1B). For a subgroup of patients with milder abnormalities that do not meet these histological criteria, the terms “microscopic colitis, not otherwise specified” or “microscopic colitis, incomplete” may be used.35 These patients often respond to standard treatments for MC. There is an additional subset of patients with biopsy demonstrating features of both CC and LC simultaneously, as well as patients transitioning from one MC subtype to another over time.32,35

Management approach

The first step in management of patients with MC includes stopping culprit medications if there is a temporal relationship between the initiation of the medication and the onset of diarrhea, as well as encouraging smoking cessation. These steps alone, however, are unlikely to achieve clinical remission in most patients. A stepwise pharmacological approach is used in the management of MC based on disease severity (Figure 2). For patients with mild symptoms, antidiarrheal medications, such as loperamide, may be helpful.36 Long-term use of loperamide at therapeutic doses no greater than 16 mg daily appears to be safe if required to maintain symptom response. For those with persistent symptoms despite antidiarrheal medications, bismuth subsalicylate at three 262 mg tablets three times daily for 6-8 weeks can be considered. Long-term use of bismuth subsalicylate is not advised, especially at this dose, because of possible neurotoxicity.37

For patients refractory to the above treatments or those with moderate-to-severe symptoms, an 8-week course of budesonide at 9 mg daily is the first-line treatment.38 The dose was tapered before discontinuation in some studies but not in others. Both strategies appear effective. A recent meta-analysis of nine randomized trials demonstrated pooled ORs of 7.34 (95% CI, 4.08-13.19) and 8.35 (95% CI, 4.14-16.85) for response to budesonide induction and maintenance, respectively.39

Cholestyramine is another medication considered in the management of MC and warrants further investigation. To date, no randomized clinical trials have been conducted to evaluate bile acid sequestrants in MC, but they should be considered before placing patients on immunosuppressive medications. Some providers use mesalamine in this setting, although mesalamine is inferior to budesonide in the induction of clinical remission in MC.40

Despite high rates of response to budesonide, relapse after discontinuation is frequent (60%-80%), and time to relapse is variable41,42 The American Gastroenterological Association recommends budesonide for maintenance of remission in patients with recurrence following discontinuation of induction therapy. The lowest effective dose that maintains resolution of symptoms should be prescribed, ideally at 6 mg daily or lower.38 Although budesonide has a greater first-pass metabolism, compared with other glucocorticoids, patients should be monitored for possible side effects including hypertension, diabetes, and osteoporosis, as well as ophthalmologic disease, including cataracts and glaucoma.

For those who are intolerant to budesonide or have refractory symptoms, concomitant disorders such as CD that may be contributing to symptoms must be excluded. Immunosuppressive medications – such as thiopurines and biologic agents, including tumor necrosis factor–alpha inhibitors or vedolizumab – may be considered in refractory cases.43,44 Of note, there are limited studies evaluating the use of these medications for MC. Lastly, surgeries including ileostomy with or without colectomy have been performed in the most severe cases for resistant disease that has failed numerous pharmacological therapies.45

Patients should be counseled that, while symptoms from MC can be quite bothersome and disabling, there appears to be a normal life expectancy and no association between MC and colon cancer, unlike with other inflammatory conditions of the colon such as IBD.46,47

Conclusion and future outlook

As a common cause of chronic watery diarrhea, MC will be commonly encountered in primary care and gastroenterology practices. The diagnosis should be suspected in patients presenting with chronic or recurrent watery diarrhea, especially with female gender, autoimmune disease, and increasing age. The management of MC requires an algorithmic approach directed by symptom severity, with a subgroup of patients requiring maintenance therapy for relapsing symptoms. The care of patients with MC will continue to evolve in the future. Further work is needed to explore long-term safety outcomes with budesonide and the role of immunomodulators and newer biologic agents for patients with complex, refractory disease.

Dr. Tome is with the department of internal medicine at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn. Dr. Kamboj, and Dr. Pardi are with the division of gastroenterology and hepatology at the Mayo Clinic. Dr. Pardi has grant funding from Pfizer, Vedanta, Seres, Finch, Applied Molecular Transport, and Takeda and has consulted for Vedanta and Otsuka. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

References

1. Nyhlin N et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;39:963-72.

2. Miehlke S et al. United European Gastroenterol J. 2020;20-8.

3. Pardi DS et al. Gut. 2007;56:504-8.

4. Fernández-Bañares F et al. J Crohn’s Colitis.2016;10(7):805-11.

5. Gentile NM et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12(5):838-42.

6. Tong J et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:265-76.

7. Olesen M et al. Gut. 2004;53(3):346-50.

8. Bergman D et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2019;49(11):1395-400.

9. Guagnozzi D et al. Dig Liver Dis. 2012;44(5):384-8.

10. Münch A et al. J Crohns Colitis. 2012;6(9):932-45.

11. Macaigne G et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014; 09(9):1461-70.

12. Verhaegh BP et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016;43(9):1004-13.

13. Stewart M et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33(12):1340-9.

14. Green PHR et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7(11):1210-6.

15. Masclee GM et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:749-59.

16. Zylberberg H et al. Ailment Pharmacol Ther. 2021 Jun;53(11)1209-15.

17. Jaruvongvanich V et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2019;25(4):672-8.

18. Fernández-Bañares F et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013; 19(7):1470-6.

19. Yen EF et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18(10):1835-41.

20. Barmeyer C et al. J Gastroenterol. 2017;52(10):1090-100.

21. Morgan DM et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18(4):984-6.

22. Larsson JK et al. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2016;70:1309-17.

23. Madisch A et al.. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17(11):2295-8.

24. Stahl E et al. Gastroenterology. 2020;159(2):549-61.

25. Sikander A et al. Dig Dis Sci. 2015; 60:887-94.

26. Abdo AA et al. Can J Gastroenterol. 2001;15(5):341-3.

27. Fernandez-Bañares F et al. Dig Dis Sci.2001;46(10):2231-8.

28. Lyutakov I et al. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;1;33(3):380-7.

29. Hjortswang H et al. Dig Liver Dis. 2011 Feb;43(2):102-9.

30. Cotter TG= et al. Gut. 2018;67(3):441-6.

31. Von Arnim U et al. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2016;9:97-103.

32. Langner C et al. Histopathology. 2015;66:613-26.

33. ASGE Standards of Practice Committee and Sharaf RN et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;78:216-24.

34. Macaigne G et al. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2017;41(3):333-40.

35. Bjørnbak C et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;34(10):1225-34.

36. Pardi DS et al. Gastroenterology. 2016;150(1):247-74.

37. Masannat Y and Nazer E. West Virginia Med J. 2013;109(3):32-4.

38. Nguyen GC et al. Gastroenterology. 2016; 150(1):242-6.

39. Sebastian S et al. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019 Aug;31(8):919-27.

40. Miehlke S et al. Gastroenterology. 2014;146(5):1222-30.

41. Gentile NM et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:256-9.

42. Münch A et al. Gut. 2016; 65(1):47-56.

43. Cotter TG et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017; 46(2):169-74.

44. Esteve M et al. J Crohns Colitis. 2011;5(6):612-8.

45. Cottreau J et al. Clin J Gastroenterol. 2016;9:140-4.

46. Kamboj AK et al. Program No. P1876. ACG 2018 Annual Scientific Meeting Abstracts. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: American College of Gastroenterology.

47. Yen EF et al. Dig Dis Sci. 2012;57:161-9.

Microscopic colitis is an inflammatory disease of the colon and a frequent cause of chronic or recurrent watery diarrhea, particularly in older persons. MC consists of two subtypes, collagenous colitis (CC) and lymphocytic colitis (LC). While the primary symptom is diarrhea, other signs and symptoms such as abdominal pain, weight loss, and dehydration or electrolyte abnormalities may also be present depending on disease severity.1 In MC, the colonic mucosa usually appears normal on colonoscopy, and the diagnosis is made by histologic findings of intraepithelial lymphocytosis with (CC) or without (LC) a prominent subepithelial collagen band. The management approaches to CC and LC are similar and should be directed based on the severity of symptoms.2 We review the epidemiology, risk factors, pathophysiology, diagnosis, and clinical management for this condition, as well as novel therapeutic approaches.

Epidemiology

Although the incidence of MC increased in the late twentieth century, more recently, it has stabilized with an estimated incidence varying from 1 to 25 per 100,000 person-years.3-5 A recent meta-analysis revealed a pooled incidence of 4.85 per 100,000 persons for LC and 4.14 per 100,000 persons for CC.6 Proposed explanations for the rising incidence in the late twentieth century include improved clinical awareness of the disease, possible increased use of drugs associated with MC, and increased performance of diagnostic colonoscopies for chronic diarrhea. Since MC is now well-recognized, the recent plateau in incidence rates may reflect decreased detection bias.

The prevalence of MC ranges from 10%-20% in patients undergoing colonoscopy for chronic watery diarrhea.6,7 The prevalence of LC is approximately 63.1 cases per 100,000 person-years and, for CC, is 49.2 cases per 100,000 person-years.6-8 Recent studies have demonstrated increasing prevalence of MC likely resulting from an aging population.9,10

Risk stratification

Female gender, increasing age, concomitant autoimmune disease, and the use of certain drugs, including NSAIDs, proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), statins, and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), have been associated with an increased risk of MC.11,12 Autoimmune disorders, including celiac disease (CD), rheumatoid arthritis, hypothyroidism, and hyperthyroidism, are more common in patients with MC. The association with CD, in particular, is clinically important, as CD is associated with a 50-70 times greater risk of MC, and 2%-9% of patients with MC have CD.13,14

Several medications have been associated with MC. In a British multicenter prospective study, MC was associated with the use of NSAIDs, PPIs, and SSRIs;15 however, recent studies have questioned the association of MC with some of these medications, which might worsen diarrhea but not actually cause MC.16

An additional risk factor for MC is smoking. A recent meta-analysis demonstrated that current and former smokers had an increased risk of MC (odds ratio, 2.99; 95% confidence interval, 2.15-4.15 and OR, 1.63; 95% CI, 1.37-1.94, respectively), compared with nonsmokers.17 Smokers develop MC at a younger age, and smoking is associated with increased disease severity and decreased likelihood of attaining remission.18,19

Pathogenesis

The pathogenesis of MC remains largely unknown, although there are several hypotheses. The leading proposed mechanisms include reaction to luminal antigens, dysregulated collagen metabolism, genetic predisposition, autoimmunity, and bile acid malabsorption.

MC may be caused by abnormal epithelial barrier function, leading to increased permeability and reaction to luminal antigens, including dietary antigens, certain drugs, and bacterial products, 20,21 which themselves lead to the immune dysregulation and intestinal inflammation seen in MC. This mechanism may explain the association of several drugs with MC. Histological changes resembling LC are reported in patients with CD who consume gluten; however, large population-based studies have not found specific dietary associations with the development of MC.22

Another potential mechanism of MC is dysregulated collagen deposition. Collagen accumulation in the subepithelial layer in CC may result from increased levels of fibroblast growth factor, transforming growth factor–beta and vascular endothelial growth factor.23 Nonetheless, studies have not found an association between the severity of diarrhea in patients with CC and the thickness of the subepithelial collagen band.

Thirdly, autoimmunity and genetic predisposition have been postulated in the pathogenesis of MC. As previously discussed, MC is associated with several autoimmune diseases and predominantly occurs in women, a distinctive feature of autoimmune disorders. Several studies have demonstrated an association between MC and HLA-DQ2 and -DQ3 haplotypes,24 as well as potential polymorphisms in the serotonin transporter gene promoter.25 It is important to note, however, that only a few familial cases of MC have been reported to date.26

Lastly, bile acid malabsorption may play a role in the etiology of MC. Histologic findings of inflammation, along with villous atrophy and collagen deposition, have been reported in the ileum of patients with MC;27,28 however, because patients with MC without bile acid malabsorption may also respond to bile acid binders such as cholestyramine, these findings unlikely to be the sole mechanism explaining the development of the disease.

Despite the different proposed mechanisms for the pathogenesis of MC, no definite conclusions can be drawn because of the limited size of these studies and their often conflicting results.

Clinical features

Clinicians should suspect MC in patients with chronic or recurrent watery diarrhea, particularly in older persons. Other risk factors include female gender, use of certain culprit medications, smoking, and presence of other autoimmune diseases. The clinical manifestations of MC subtypes LC and CC are similar with no significant clinical differences.1,2 In addition to diarrhea, patients with MC may have abdominal pain, fatigue, and dehydration or electrolyte abnormalities depending on disease severity. Patients may also present with fecal urgency, incontinence, and nocturnal stools. Quality of life is often reduced in these patients, predominantly in those with severe or refractory symptoms.29,30 The natural course of MC is highly variable, with some patients achieving spontaneous resolution after one episode and others developing chronic symptoms.

Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of chronic watery diarrhea is broad and includes malabsorption/maldigestion, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), irritable bowel syndrome, and medication side effects. In addition, although gastrointestinal infections typically cause acute or subacute diarrhea, some can present with chronic diarrhea. Malabsorption/maldigestion may occur because of CD, lactose intolerance, and pancreatic insufficiency, among other conditions. A thorough history, regarding recent antibiotic and medication use, travel, and immunosuppression, should be obtained in patients with chronic diarrhea. Additionally, laboratory and endoscopic evaluation with random biopsies of the colon can further help differentiate these diseases from MC. A few studies suggest fecal calprotectin may be used to differentiate MC from other noninflammatory conditions such as irritable bowel syndrome, as well as to monitor disease activity. This test is not expected to distinguish MC from other inflammatory causes of diarrhea, such as IBD, and therefore, its role in clinical practice is uncertain.31

The diagnosis of MC is made by biopsy of the colonic mucosa demonstrating characteristic pathologic features.32 Unlike in diseases such as Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis, the colon usually appears normal in MC, although mild nonspecific changes, such as erythema or edema, may be visualized. There is no consensus on the ideal location to obtain biopsies for MC or whether biopsies from both the left and the right colon are required.2,33 The procedure of choice for the diagnosis of MC is colonoscopy with random biopsies taken throughout the colon. More limited evaluation by flexible sigmoidoscopy with biopsies may miss cases of MC as inflammation and collagen thickening are not necessarily uniform throughout the colon; however, in a patient that has undergone a recent colonoscopy for colon cancer screening without colon biopsies, a flexible sigmoidoscopy may be a reasonable next test for evaluation of MC, provided biopsies are obtained above the rectosigmoid colon.34

The MC subtypes are differentiated based on histology. The hallmark of LC is less than 20 intraepithelial lymphocytes per 100 surface epithelial cells (normal, less than 5) (Figure 1A). CC is characterized by a thickened subepithelial collagen band greater than 7-10 micrometers (normal, less than 5) (Figure 1B). For a subgroup of patients with milder abnormalities that do not meet these histological criteria, the terms “microscopic colitis, not otherwise specified” or “microscopic colitis, incomplete” may be used.35 These patients often respond to standard treatments for MC. There is an additional subset of patients with biopsy demonstrating features of both CC and LC simultaneously, as well as patients transitioning from one MC subtype to another over time.32,35

Management approach

The first step in management of patients with MC includes stopping culprit medications if there is a temporal relationship between the initiation of the medication and the onset of diarrhea, as well as encouraging smoking cessation. These steps alone, however, are unlikely to achieve clinical remission in most patients. A stepwise pharmacological approach is used in the management of MC based on disease severity (Figure 2). For patients with mild symptoms, antidiarrheal medications, such as loperamide, may be helpful.36 Long-term use of loperamide at therapeutic doses no greater than 16 mg daily appears to be safe if required to maintain symptom response. For those with persistent symptoms despite antidiarrheal medications, bismuth subsalicylate at three 262 mg tablets three times daily for 6-8 weeks can be considered. Long-term use of bismuth subsalicylate is not advised, especially at this dose, because of possible neurotoxicity.37

For patients refractory to the above treatments or those with moderate-to-severe symptoms, an 8-week course of budesonide at 9 mg daily is the first-line treatment.38 The dose was tapered before discontinuation in some studies but not in others. Both strategies appear effective. A recent meta-analysis of nine randomized trials demonstrated pooled ORs of 7.34 (95% CI, 4.08-13.19) and 8.35 (95% CI, 4.14-16.85) for response to budesonide induction and maintenance, respectively.39

Cholestyramine is another medication considered in the management of MC and warrants further investigation. To date, no randomized clinical trials have been conducted to evaluate bile acid sequestrants in MC, but they should be considered before placing patients on immunosuppressive medications. Some providers use mesalamine in this setting, although mesalamine is inferior to budesonide in the induction of clinical remission in MC.40

Despite high rates of response to budesonide, relapse after discontinuation is frequent (60%-80%), and time to relapse is variable41,42 The American Gastroenterological Association recommends budesonide for maintenance of remission in patients with recurrence following discontinuation of induction therapy. The lowest effective dose that maintains resolution of symptoms should be prescribed, ideally at 6 mg daily or lower.38 Although budesonide has a greater first-pass metabolism, compared with other glucocorticoids, patients should be monitored for possible side effects including hypertension, diabetes, and osteoporosis, as well as ophthalmologic disease, including cataracts and glaucoma.

For those who are intolerant to budesonide or have refractory symptoms, concomitant disorders such as CD that may be contributing to symptoms must be excluded. Immunosuppressive medications – such as thiopurines and biologic agents, including tumor necrosis factor–alpha inhibitors or vedolizumab – may be considered in refractory cases.43,44 Of note, there are limited studies evaluating the use of these medications for MC. Lastly, surgeries including ileostomy with or without colectomy have been performed in the most severe cases for resistant disease that has failed numerous pharmacological therapies.45

Patients should be counseled that, while symptoms from MC can be quite bothersome and disabling, there appears to be a normal life expectancy and no association between MC and colon cancer, unlike with other inflammatory conditions of the colon such as IBD.46,47

Conclusion and future outlook

As a common cause of chronic watery diarrhea, MC will be commonly encountered in primary care and gastroenterology practices. The diagnosis should be suspected in patients presenting with chronic or recurrent watery diarrhea, especially with female gender, autoimmune disease, and increasing age. The management of MC requires an algorithmic approach directed by symptom severity, with a subgroup of patients requiring maintenance therapy for relapsing symptoms. The care of patients with MC will continue to evolve in the future. Further work is needed to explore long-term safety outcomes with budesonide and the role of immunomodulators and newer biologic agents for patients with complex, refractory disease.

Dr. Tome is with the department of internal medicine at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn. Dr. Kamboj, and Dr. Pardi are with the division of gastroenterology and hepatology at the Mayo Clinic. Dr. Pardi has grant funding from Pfizer, Vedanta, Seres, Finch, Applied Molecular Transport, and Takeda and has consulted for Vedanta and Otsuka. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

References

1. Nyhlin N et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;39:963-72.

2. Miehlke S et al. United European Gastroenterol J. 2020;20-8.

3. Pardi DS et al. Gut. 2007;56:504-8.

4. Fernández-Bañares F et al. J Crohn’s Colitis.2016;10(7):805-11.

5. Gentile NM et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12(5):838-42.

6. Tong J et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:265-76.

7. Olesen M et al. Gut. 2004;53(3):346-50.

8. Bergman D et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2019;49(11):1395-400.

9. Guagnozzi D et al. Dig Liver Dis. 2012;44(5):384-8.

10. Münch A et al. J Crohns Colitis. 2012;6(9):932-45.

11. Macaigne G et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014; 09(9):1461-70.

12. Verhaegh BP et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016;43(9):1004-13.

13. Stewart M et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33(12):1340-9.

14. Green PHR et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7(11):1210-6.

15. Masclee GM et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:749-59.

16. Zylberberg H et al. Ailment Pharmacol Ther. 2021 Jun;53(11)1209-15.

17. Jaruvongvanich V et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2019;25(4):672-8.

18. Fernández-Bañares F et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013; 19(7):1470-6.

19. Yen EF et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18(10):1835-41.

20. Barmeyer C et al. J Gastroenterol. 2017;52(10):1090-100.

21. Morgan DM et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18(4):984-6.

22. Larsson JK et al. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2016;70:1309-17.

23. Madisch A et al.. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17(11):2295-8.

24. Stahl E et al. Gastroenterology. 2020;159(2):549-61.

25. Sikander A et al. Dig Dis Sci. 2015; 60:887-94.

26. Abdo AA et al. Can J Gastroenterol. 2001;15(5):341-3.

27. Fernandez-Bañares F et al. Dig Dis Sci.2001;46(10):2231-8.

28. Lyutakov I et al. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;1;33(3):380-7.

29. Hjortswang H et al. Dig Liver Dis. 2011 Feb;43(2):102-9.

30. Cotter TG= et al. Gut. 2018;67(3):441-6.

31. Von Arnim U et al. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2016;9:97-103.

32. Langner C et al. Histopathology. 2015;66:613-26.

33. ASGE Standards of Practice Committee and Sharaf RN et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;78:216-24.

34. Macaigne G et al. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2017;41(3):333-40.

35. Bjørnbak C et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;34(10):1225-34.

36. Pardi DS et al. Gastroenterology. 2016;150(1):247-74.

37. Masannat Y and Nazer E. West Virginia Med J. 2013;109(3):32-4.

38. Nguyen GC et al. Gastroenterology. 2016; 150(1):242-6.

39. Sebastian S et al. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019 Aug;31(8):919-27.

40. Miehlke S et al. Gastroenterology. 2014;146(5):1222-30.

41. Gentile NM et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:256-9.

42. Münch A et al. Gut. 2016; 65(1):47-56.

43. Cotter TG et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017; 46(2):169-74.

44. Esteve M et al. J Crohns Colitis. 2011;5(6):612-8.

45. Cottreau J et al. Clin J Gastroenterol. 2016;9:140-4.

46. Kamboj AK et al. Program No. P1876. ACG 2018 Annual Scientific Meeting Abstracts. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: American College of Gastroenterology.

47. Yen EF et al. Dig Dis Sci. 2012;57:161-9.

What is your diagnosis? - July 2020

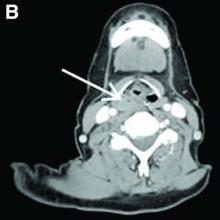

Fibroepithelial polyp of the hypopharynx

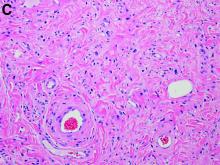

Our patient underwent an upper endoscopy to evaluate symptoms of refractory gastroesophageal reflux disease and was found to have a large hiatal hernia. Upon careful endoscopic withdrawal, the polyp was briefly visualized as it was pulled back into the oropharynx. The patient was referred for flexible laryngoscopy that confirmed a polypoid mass involving the right lateral piriform wall. She subsequently underwent direct laryngoscopy with harmonic scalpel-assisted excision of the lesion leading to resolution of her symptom of oropharyngeal dysphagia. The surgical specimen measured 3 × 1.4 × 0.4 cm. Pathology demonstrated benign overlying squamous mucosa with submucosa composed of bland spindle cells and fat, consistent with a benign fibroepithelial polyp (Figure C, original magnification × 100; stain: hematoxylin and eosin).

Fibroepithelial polyps are rare benign lesions of the hypopharynx and proximal esophagus that can lead to oropharyngeal dysphagia.1 Larger hypopharyngeal polyps have been associated with aspiration and airway compromise.1 Owing to their proximal location, these lesions are more readily identified under flexible laryngoscopy, but can also be observed with esophagogastroduodenoscopy. Cross-sectional imaging of the neck can be considered for patients with oropharyngeal dysphagia and a normal video-swallow study. Although the underlying pathogenesis remains unclear, inflammation or infection may play a role, especially in smokers.2 The rate of recurrence after resection is low.1

Further evaluation for her symptomatic hiatal hernia was performed and the patient ultimately underwent a laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication with wedge gastroplasty, leading to improvement in her symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease. This case illustrates that, although esophagogastroduodenoscopy is not considered the first step in the evaluation of patients with oropharyngeal dysphagia, a careful examination can sometimes reveal the diagnosis.

References

1. Caceres M, et al. Large pedunculated polyps originating in the esophagus and hypopharynx. Ann Thorac Surg. 2006;81:393-6.

2. Maskey AP, et al. Endobronchial fibroepithelial polyp. J Bronchology Interv Pulmonol. 2012;19:313-4.

ginews@gastro.org

Fibroepithelial polyp of the hypopharynx

Our patient underwent an upper endoscopy to evaluate symptoms of refractory gastroesophageal reflux disease and was found to have a large hiatal hernia. Upon careful endoscopic withdrawal, the polyp was briefly visualized as it was pulled back into the oropharynx. The patient was referred for flexible laryngoscopy that confirmed a polypoid mass involving the right lateral piriform wall. She subsequently underwent direct laryngoscopy with harmonic scalpel-assisted excision of the lesion leading to resolution of her symptom of oropharyngeal dysphagia. The surgical specimen measured 3 × 1.4 × 0.4 cm. Pathology demonstrated benign overlying squamous mucosa with submucosa composed of bland spindle cells and fat, consistent with a benign fibroepithelial polyp (Figure C, original magnification × 100; stain: hematoxylin and eosin).

Fibroepithelial polyps are rare benign lesions of the hypopharynx and proximal esophagus that can lead to oropharyngeal dysphagia.1 Larger hypopharyngeal polyps have been associated with aspiration and airway compromise.1 Owing to their proximal location, these lesions are more readily identified under flexible laryngoscopy, but can also be observed with esophagogastroduodenoscopy. Cross-sectional imaging of the neck can be considered for patients with oropharyngeal dysphagia and a normal video-swallow study. Although the underlying pathogenesis remains unclear, inflammation or infection may play a role, especially in smokers.2 The rate of recurrence after resection is low.1

Further evaluation for her symptomatic hiatal hernia was performed and the patient ultimately underwent a laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication with wedge gastroplasty, leading to improvement in her symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease. This case illustrates that, although esophagogastroduodenoscopy is not considered the first step in the evaluation of patients with oropharyngeal dysphagia, a careful examination can sometimes reveal the diagnosis.

References

1. Caceres M, et al. Large pedunculated polyps originating in the esophagus and hypopharynx. Ann Thorac Surg. 2006;81:393-6.

2. Maskey AP, et al. Endobronchial fibroepithelial polyp. J Bronchology Interv Pulmonol. 2012;19:313-4.

ginews@gastro.org

Fibroepithelial polyp of the hypopharynx

Our patient underwent an upper endoscopy to evaluate symptoms of refractory gastroesophageal reflux disease and was found to have a large hiatal hernia. Upon careful endoscopic withdrawal, the polyp was briefly visualized as it was pulled back into the oropharynx. The patient was referred for flexible laryngoscopy that confirmed a polypoid mass involving the right lateral piriform wall. She subsequently underwent direct laryngoscopy with harmonic scalpel-assisted excision of the lesion leading to resolution of her symptom of oropharyngeal dysphagia. The surgical specimen measured 3 × 1.4 × 0.4 cm. Pathology demonstrated benign overlying squamous mucosa with submucosa composed of bland spindle cells and fat, consistent with a benign fibroepithelial polyp (Figure C, original magnification × 100; stain: hematoxylin and eosin).

Fibroepithelial polyps are rare benign lesions of the hypopharynx and proximal esophagus that can lead to oropharyngeal dysphagia.1 Larger hypopharyngeal polyps have been associated with aspiration and airway compromise.1 Owing to their proximal location, these lesions are more readily identified under flexible laryngoscopy, but can also be observed with esophagogastroduodenoscopy. Cross-sectional imaging of the neck can be considered for patients with oropharyngeal dysphagia and a normal video-swallow study. Although the underlying pathogenesis remains unclear, inflammation or infection may play a role, especially in smokers.2 The rate of recurrence after resection is low.1

Further evaluation for her symptomatic hiatal hernia was performed and the patient ultimately underwent a laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication with wedge gastroplasty, leading to improvement in her symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease. This case illustrates that, although esophagogastroduodenoscopy is not considered the first step in the evaluation of patients with oropharyngeal dysphagia, a careful examination can sometimes reveal the diagnosis.

References

1. Caceres M, et al. Large pedunculated polyps originating in the esophagus and hypopharynx. Ann Thorac Surg. 2006;81:393-6.

2. Maskey AP, et al. Endobronchial fibroepithelial polyp. J Bronchology Interv Pulmonol. 2012;19:313-4.

ginews@gastro.org