User login

What is your diagnosis?

Answer: Infectious gastroparesis secondary to acute hepatitis A infection.

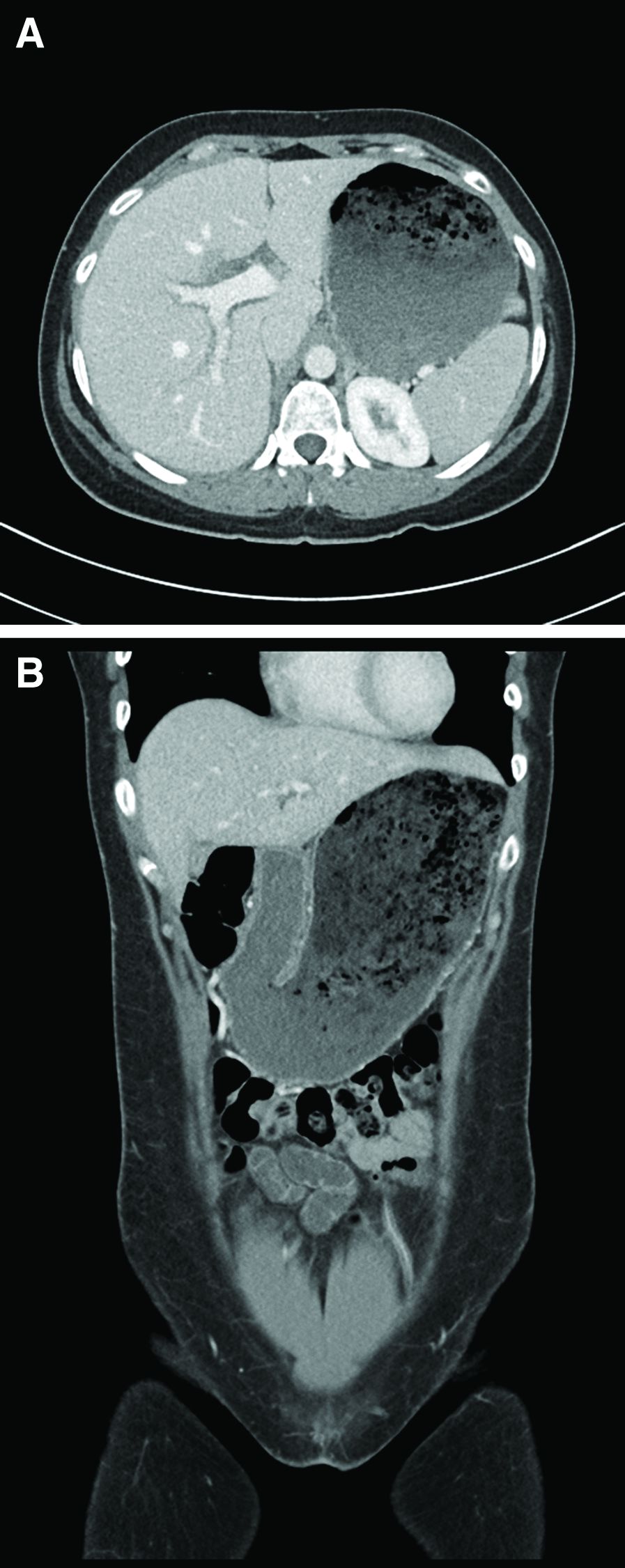

A computed tomography scan of the abdomen/pelvis demonstrated marked gastric distention without obvious obstructing mass and normal caliber small bowel and colon. Additional laboratory workup revealed a positive hepatitis A IgM antibody. Hepatitis B surface antigen and core IgM antibody were negative, as was the hepatitis C virus antibody. Human immunodeficiency virus antigen and antibody were negative. An esophagogastroduodenoscopy was performed that showed a large amount of food in a dilated and atonic stomach.

With conservative treatment, the patient’s liver enzymes trended down over the next 2 days to alanine aminotransferase 993 U/L, aspartate aminotransferase 244 U/L, and direct bilirubin 3.8 mg/dL. At the time of discharge, she was tolerating soft foods without any difficulty. She was educated on taking appropriate precautions to avoid transmitting the hepatitis A infection to others. Her risk factor for hepatitis A was recent incarceration.

Here we highlight a rare case of infectious gastroparesis secondary to hepatitis A infection. Hepatitis A virus is a small, nonenveloped, RNA-containing virus.1 It typically presents with a self-limited illness with liver failure occurring in rare cases. Common presenting symptoms including nausea, vomiting, jaundice, fever, diarrhea, and abdominal pain.Laboratory abnormalities include elevations in the serum aminotransferases, alkaline phosphatase, and total bilirubin.2 The diagnosis is confirmed with a positive hepatitis A IgM antibody. The most common route of transmission is the fecal-oral route such as through consumption of contaminated water and food or from person-to-person contact.1 Individuals can develop immunity to the virus either from prior infection or vaccination.

Gastroparesis refers to delayed emptying of gastric contents when mechanical obstruction has been ruled out. Common causes of gastroparesis include diabetes mellitus, medications, postoperative complications, and infections. Infectious gastroparesis may present acutely after a viral prodrome and symptoms may be severe and slow to resolve.3

References

1. Lemon SM. N Engl J Med. 1985 Oct 24;313(17):1059-67.

2. Tong MJ et al. J Infect Dis. 1995 Mar;171 Suppl 1:S15-8.

3. Bityutskiy LP. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997 Sep;92(9):1501-4.

Answer: Infectious gastroparesis secondary to acute hepatitis A infection.

A computed tomography scan of the abdomen/pelvis demonstrated marked gastric distention without obvious obstructing mass and normal caliber small bowel and colon. Additional laboratory workup revealed a positive hepatitis A IgM antibody. Hepatitis B surface antigen and core IgM antibody were negative, as was the hepatitis C virus antibody. Human immunodeficiency virus antigen and antibody were negative. An esophagogastroduodenoscopy was performed that showed a large amount of food in a dilated and atonic stomach.

With conservative treatment, the patient’s liver enzymes trended down over the next 2 days to alanine aminotransferase 993 U/L, aspartate aminotransferase 244 U/L, and direct bilirubin 3.8 mg/dL. At the time of discharge, she was tolerating soft foods without any difficulty. She was educated on taking appropriate precautions to avoid transmitting the hepatitis A infection to others. Her risk factor for hepatitis A was recent incarceration.

Here we highlight a rare case of infectious gastroparesis secondary to hepatitis A infection. Hepatitis A virus is a small, nonenveloped, RNA-containing virus.1 It typically presents with a self-limited illness with liver failure occurring in rare cases. Common presenting symptoms including nausea, vomiting, jaundice, fever, diarrhea, and abdominal pain.Laboratory abnormalities include elevations in the serum aminotransferases, alkaline phosphatase, and total bilirubin.2 The diagnosis is confirmed with a positive hepatitis A IgM antibody. The most common route of transmission is the fecal-oral route such as through consumption of contaminated water and food or from person-to-person contact.1 Individuals can develop immunity to the virus either from prior infection or vaccination.

Gastroparesis refers to delayed emptying of gastric contents when mechanical obstruction has been ruled out. Common causes of gastroparesis include diabetes mellitus, medications, postoperative complications, and infections. Infectious gastroparesis may present acutely after a viral prodrome and symptoms may be severe and slow to resolve.3

References

1. Lemon SM. N Engl J Med. 1985 Oct 24;313(17):1059-67.

2. Tong MJ et al. J Infect Dis. 1995 Mar;171 Suppl 1:S15-8.

3. Bityutskiy LP. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997 Sep;92(9):1501-4.

Answer: Infectious gastroparesis secondary to acute hepatitis A infection.

A computed tomography scan of the abdomen/pelvis demonstrated marked gastric distention without obvious obstructing mass and normal caliber small bowel and colon. Additional laboratory workup revealed a positive hepatitis A IgM antibody. Hepatitis B surface antigen and core IgM antibody were negative, as was the hepatitis C virus antibody. Human immunodeficiency virus antigen and antibody were negative. An esophagogastroduodenoscopy was performed that showed a large amount of food in a dilated and atonic stomach.

With conservative treatment, the patient’s liver enzymes trended down over the next 2 days to alanine aminotransferase 993 U/L, aspartate aminotransferase 244 U/L, and direct bilirubin 3.8 mg/dL. At the time of discharge, she was tolerating soft foods without any difficulty. She was educated on taking appropriate precautions to avoid transmitting the hepatitis A infection to others. Her risk factor for hepatitis A was recent incarceration.

Here we highlight a rare case of infectious gastroparesis secondary to hepatitis A infection. Hepatitis A virus is a small, nonenveloped, RNA-containing virus.1 It typically presents with a self-limited illness with liver failure occurring in rare cases. Common presenting symptoms including nausea, vomiting, jaundice, fever, diarrhea, and abdominal pain.Laboratory abnormalities include elevations in the serum aminotransferases, alkaline phosphatase, and total bilirubin.2 The diagnosis is confirmed with a positive hepatitis A IgM antibody. The most common route of transmission is the fecal-oral route such as through consumption of contaminated water and food or from person-to-person contact.1 Individuals can develop immunity to the virus either from prior infection or vaccination.

Gastroparesis refers to delayed emptying of gastric contents when mechanical obstruction has been ruled out. Common causes of gastroparesis include diabetes mellitus, medications, postoperative complications, and infections. Infectious gastroparesis may present acutely after a viral prodrome and symptoms may be severe and slow to resolve.3

References

1. Lemon SM. N Engl J Med. 1985 Oct 24;313(17):1059-67.

2. Tong MJ et al. J Infect Dis. 1995 Mar;171 Suppl 1:S15-8.

3. Bityutskiy LP. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997 Sep;92(9):1501-4.

A 33-year-old woman presented with a 10-day history of painless jaundice. During this time, she also noted decreased appetite, malaise, and pruritus. On occasion, she would have heartburn and belching that would improve with an antacid. She denied any right upper quadrant pain and weight loss. She was not currently taking any medications, including acetaminophen. She had a past medical history of methamphetamine use in recent remission. She had recently been incarcerated for about 1 month.

What is the most likely etiology of the patient's condition?