User login

Unilateral Verrucous Psoriasis

Case Report

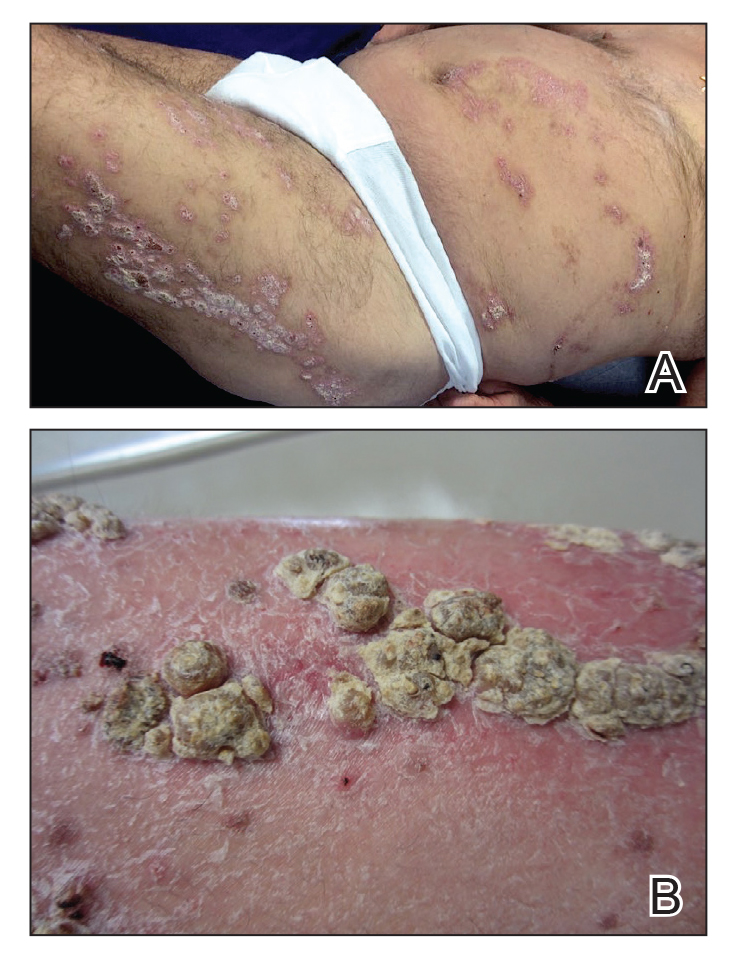

An 80-year-old man with a history of hypertension and coronary artery disease presented to the dermatology clinic with a rash characterized by multiple asymptomatic plaques with overlying verrucous nodules on the left side of the abdomen, back, and leg (Figure 1). He reported that these “growths” appeared 20 years prior to presentation, shortly after coronary artery bypass surgery with a saphenous vein graft. The patient initially was given a diagnosis of verruca vulgaris and then biopsy-proven psoriasis later that year. At that time, he refused systemic treatment and was treated instead with triamcinolone acetonide ointment, with periodic surgical removal of bothersome lesions.

At the current presentation, physical examination revealed many hyperkeratotic, yellow-gray, verrucous nodules overlying scaly, erythematous, sharply demarcated plaques, exclusively on the left side of the body, including the left side of the abdomen, back, and leg. The differential diagnosis included linear psoriasis and inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus (ILVEN).

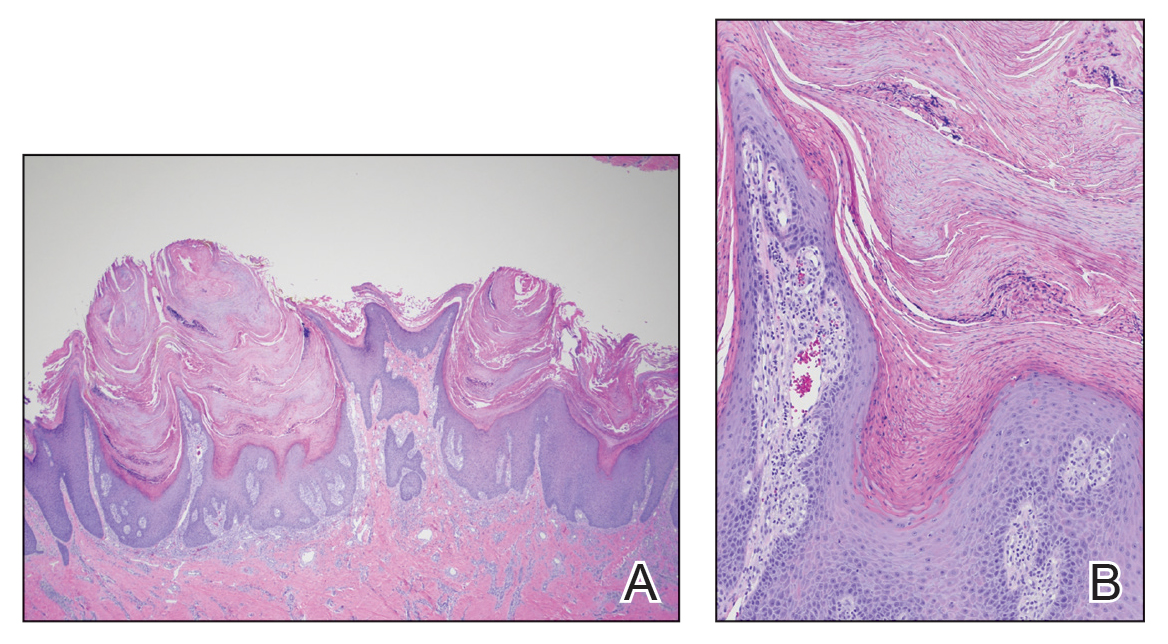

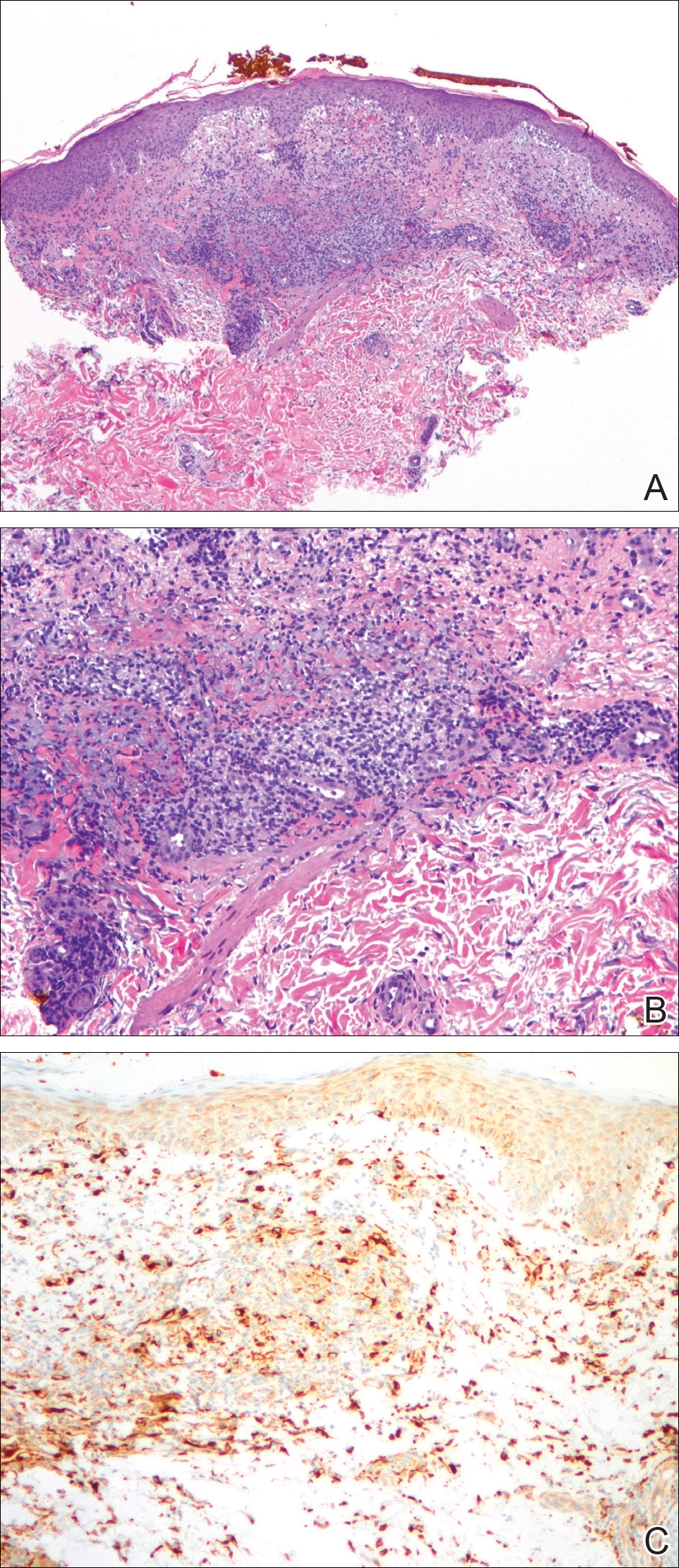

Skin biopsy showed irregular psoriasiform epidermal hyperplasia with acanthosis, hyperkeratosis, and papillomatosis, with convergence of the rete ridges, known as buttressing (Figure 2A). There were tortuous dilated blood vessels in the dermal papillae, epidermal neutrophils at the tip of the suprapapillary plates, and Munro microabscesses in the stratum corneum (Figure 2B). Koilocytes were absent, and periodic acid–Schiff staining was negative. Taken together, clinical and histologic features led to a diagnosis of unilateral verrucous psoriasis.

Comment

Presentation and Histology

Verrucous psoriasis is a variant of psoriasis that presents with wartlike clinical features and overlapping histologic features of verruca and psoriasis. It typically arises in patients with established psoriasis but can occur de novo.

Histologic features of verrucous psoriasis include epidermal hyperplasia with acanthosis, papillomatosis, and epidermal buttressing.1 It has been hypothesized that notable hyperkeratosis observed in these lesions is induced by repeat trauma to the extremities in patients with established psoriasis or by anoxia from conditions that predispose to poor circulation, such as diabetes mellitus and pulmonary disease.1,2

Pathogenesis

Most reported cases of verrucous psoriasis arose atop pre-existing psoriasis lesions.3,4 The relevance of our patient’s verrucous psoriasis to his prior coronary artery bypass surgery with saphenous vein graft is unknown; however, the distribution of lesions, timing of psoriasis onset in relation to the surgical procedure, and recent data proposing a role for neuropeptide responses to nerve injury in the development of psoriasis, taken together, provide an argument for a role for surgical trauma in the development of our patient’s condition.

Treatment

Although verrucous psoriasis presents both diagnostic and therapeutic challenges, there are some reports of improvement with topical or intralesional corticosteroids in combination with keratolytics,3 coal tar,5 and oral methotrexate.6 In addition, there are rare reports of successful treatment with biologics. A case report showed successful resolution with adalimumab,4 and a case of erythrodermic verrucous psoriasis showed moderate improvement with ustekinumab after other failed treatments.7

Differential Diagnosis

Psoriasis typically presents in a symmetric distribution, with rare reported cases of unilateral distribution. Two cases of unilateral psoriasis arising after a surgical procedure have been reported, one after mastectomy and the other after neurosurgery.8,9 Other cases of unilateral psoriasis are reported to have arisen in adolescents and young adults idiopathically.

A case of linear psoriasis arising in the distribution of the sciatic nerve in a patient with radiculopathy implicated tumor necrosis factor α, neuropeptides, and nerve growth factor released in response to compression as possible etiologic agents.10 However, none of the reported cases of linear psoriasis, or reported cases of unilateral psoriasis, exhibited verrucous features clinically or histologically. In our patient, distribution of the lesions appeared less typically blaschkoid than in linear psoriasis, and the presence of exophytic wartlike growths throughout the lesions was not characteristic of linear psoriasis.

Late-adulthood onset in this patient in addition to the absence of typical histologic features of ILVEN, including alternating orthokeratosis and parakeratosis,11 make a diagnosis of ILVEN less likely; ILVEN can be distinguished from linear psoriasis based on later age of onset and responsiveness to antipsoriatic therapy of linear psoriasis.12

Conclusion

We describe a unique presentation of an already rare variant of psoriasis that can be difficult to diagnose clinically. The unilateral distribution of lesions in this patient can create further diagnostic confusion with other entities, such as ILVEN and linear psoriasis, though it can be distinguished from those diseases based on histologic features. Our aim is that this report improves recognition of this unusual presentation of verrucous psoriasis in clinical settings and decreases delays in diagnosis and treatment.

- Khalil FK, Keehn CA, Saeed S, et al. Verrucous psoriasis: a distinctive clinicopathologic variant of psoriasis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:204-207.

- Wakamatsu K, Naniwa K, Hagiya Y, et al. Psoriasis verrucosa. J Dermatol. 2010;37:1060-1062.

- Monroe HR, Hillman JD, Chiu MW. A case of verrucous psoriasis. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:10.

- Maejima H, Katayama C, Watarai A, et al. A case of psoriasis verrucosa successfully treated with adalimumab. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:E74-E75.

- Erkek E, Bozdog˘an O. Annular verrucous psoriasis with exaggerated papillomatosis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2001;23:133-135.

- Hall L, Marks V, Tyler W. Verrucous psoriasis: a clinical and histopathologic mimicker of verruca vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68(4 suppl 1):AB218.

- Curtis AR, Yosipovitch G. Erythrodermic verrucous psoriasis. J Dermatolog Treat. 2012;23:215-218.

- Kim M, Jung JY, Na SY, et al. Unilateral psoriasis in a woman with ipsilateral post-mastectomy lymphedema. Ann Dermatol. 2011;23(suppl 3):S303-S305.

- Reyter I, Woodley D. Widespread unilateral plaques in a 68-year-old woman after neurosurgery. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:1531-1536.

- Galluzzo M, Talamonti M, Di Stefani A, et al. Linear psoriasis following the typical distribution of the sciatic nerve. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2015;9:6-11.

- Sengupta S, Das JK, Gangopadhyay A. Naevoid psoriasis and ILVEN: same coin, two faces? Indian J Dermatol. 2012;57:489-491.

- Morag C, Metzker A. Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus: report of seven new cases and review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 1985;3:15-18.

Case Report

An 80-year-old man with a history of hypertension and coronary artery disease presented to the dermatology clinic with a rash characterized by multiple asymptomatic plaques with overlying verrucous nodules on the left side of the abdomen, back, and leg (Figure 1). He reported that these “growths” appeared 20 years prior to presentation, shortly after coronary artery bypass surgery with a saphenous vein graft. The patient initially was given a diagnosis of verruca vulgaris and then biopsy-proven psoriasis later that year. At that time, he refused systemic treatment and was treated instead with triamcinolone acetonide ointment, with periodic surgical removal of bothersome lesions.

At the current presentation, physical examination revealed many hyperkeratotic, yellow-gray, verrucous nodules overlying scaly, erythematous, sharply demarcated plaques, exclusively on the left side of the body, including the left side of the abdomen, back, and leg. The differential diagnosis included linear psoriasis and inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus (ILVEN).

Skin biopsy showed irregular psoriasiform epidermal hyperplasia with acanthosis, hyperkeratosis, and papillomatosis, with convergence of the rete ridges, known as buttressing (Figure 2A). There were tortuous dilated blood vessels in the dermal papillae, epidermal neutrophils at the tip of the suprapapillary plates, and Munro microabscesses in the stratum corneum (Figure 2B). Koilocytes were absent, and periodic acid–Schiff staining was negative. Taken together, clinical and histologic features led to a diagnosis of unilateral verrucous psoriasis.

Comment

Presentation and Histology

Verrucous psoriasis is a variant of psoriasis that presents with wartlike clinical features and overlapping histologic features of verruca and psoriasis. It typically arises in patients with established psoriasis but can occur de novo.

Histologic features of verrucous psoriasis include epidermal hyperplasia with acanthosis, papillomatosis, and epidermal buttressing.1 It has been hypothesized that notable hyperkeratosis observed in these lesions is induced by repeat trauma to the extremities in patients with established psoriasis or by anoxia from conditions that predispose to poor circulation, such as diabetes mellitus and pulmonary disease.1,2

Pathogenesis

Most reported cases of verrucous psoriasis arose atop pre-existing psoriasis lesions.3,4 The relevance of our patient’s verrucous psoriasis to his prior coronary artery bypass surgery with saphenous vein graft is unknown; however, the distribution of lesions, timing of psoriasis onset in relation to the surgical procedure, and recent data proposing a role for neuropeptide responses to nerve injury in the development of psoriasis, taken together, provide an argument for a role for surgical trauma in the development of our patient’s condition.

Treatment

Although verrucous psoriasis presents both diagnostic and therapeutic challenges, there are some reports of improvement with topical or intralesional corticosteroids in combination with keratolytics,3 coal tar,5 and oral methotrexate.6 In addition, there are rare reports of successful treatment with biologics. A case report showed successful resolution with adalimumab,4 and a case of erythrodermic verrucous psoriasis showed moderate improvement with ustekinumab after other failed treatments.7

Differential Diagnosis

Psoriasis typically presents in a symmetric distribution, with rare reported cases of unilateral distribution. Two cases of unilateral psoriasis arising after a surgical procedure have been reported, one after mastectomy and the other after neurosurgery.8,9 Other cases of unilateral psoriasis are reported to have arisen in adolescents and young adults idiopathically.

A case of linear psoriasis arising in the distribution of the sciatic nerve in a patient with radiculopathy implicated tumor necrosis factor α, neuropeptides, and nerve growth factor released in response to compression as possible etiologic agents.10 However, none of the reported cases of linear psoriasis, or reported cases of unilateral psoriasis, exhibited verrucous features clinically or histologically. In our patient, distribution of the lesions appeared less typically blaschkoid than in linear psoriasis, and the presence of exophytic wartlike growths throughout the lesions was not characteristic of linear psoriasis.

Late-adulthood onset in this patient in addition to the absence of typical histologic features of ILVEN, including alternating orthokeratosis and parakeratosis,11 make a diagnosis of ILVEN less likely; ILVEN can be distinguished from linear psoriasis based on later age of onset and responsiveness to antipsoriatic therapy of linear psoriasis.12

Conclusion

We describe a unique presentation of an already rare variant of psoriasis that can be difficult to diagnose clinically. The unilateral distribution of lesions in this patient can create further diagnostic confusion with other entities, such as ILVEN and linear psoriasis, though it can be distinguished from those diseases based on histologic features. Our aim is that this report improves recognition of this unusual presentation of verrucous psoriasis in clinical settings and decreases delays in diagnosis and treatment.

Case Report

An 80-year-old man with a history of hypertension and coronary artery disease presented to the dermatology clinic with a rash characterized by multiple asymptomatic plaques with overlying verrucous nodules on the left side of the abdomen, back, and leg (Figure 1). He reported that these “growths” appeared 20 years prior to presentation, shortly after coronary artery bypass surgery with a saphenous vein graft. The patient initially was given a diagnosis of verruca vulgaris and then biopsy-proven psoriasis later that year. At that time, he refused systemic treatment and was treated instead with triamcinolone acetonide ointment, with periodic surgical removal of bothersome lesions.

At the current presentation, physical examination revealed many hyperkeratotic, yellow-gray, verrucous nodules overlying scaly, erythematous, sharply demarcated plaques, exclusively on the left side of the body, including the left side of the abdomen, back, and leg. The differential diagnosis included linear psoriasis and inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus (ILVEN).

Skin biopsy showed irregular psoriasiform epidermal hyperplasia with acanthosis, hyperkeratosis, and papillomatosis, with convergence of the rete ridges, known as buttressing (Figure 2A). There were tortuous dilated blood vessels in the dermal papillae, epidermal neutrophils at the tip of the suprapapillary plates, and Munro microabscesses in the stratum corneum (Figure 2B). Koilocytes were absent, and periodic acid–Schiff staining was negative. Taken together, clinical and histologic features led to a diagnosis of unilateral verrucous psoriasis.

Comment

Presentation and Histology

Verrucous psoriasis is a variant of psoriasis that presents with wartlike clinical features and overlapping histologic features of verruca and psoriasis. It typically arises in patients with established psoriasis but can occur de novo.

Histologic features of verrucous psoriasis include epidermal hyperplasia with acanthosis, papillomatosis, and epidermal buttressing.1 It has been hypothesized that notable hyperkeratosis observed in these lesions is induced by repeat trauma to the extremities in patients with established psoriasis or by anoxia from conditions that predispose to poor circulation, such as diabetes mellitus and pulmonary disease.1,2

Pathogenesis

Most reported cases of verrucous psoriasis arose atop pre-existing psoriasis lesions.3,4 The relevance of our patient’s verrucous psoriasis to his prior coronary artery bypass surgery with saphenous vein graft is unknown; however, the distribution of lesions, timing of psoriasis onset in relation to the surgical procedure, and recent data proposing a role for neuropeptide responses to nerve injury in the development of psoriasis, taken together, provide an argument for a role for surgical trauma in the development of our patient’s condition.

Treatment

Although verrucous psoriasis presents both diagnostic and therapeutic challenges, there are some reports of improvement with topical or intralesional corticosteroids in combination with keratolytics,3 coal tar,5 and oral methotrexate.6 In addition, there are rare reports of successful treatment with biologics. A case report showed successful resolution with adalimumab,4 and a case of erythrodermic verrucous psoriasis showed moderate improvement with ustekinumab after other failed treatments.7

Differential Diagnosis

Psoriasis typically presents in a symmetric distribution, with rare reported cases of unilateral distribution. Two cases of unilateral psoriasis arising after a surgical procedure have been reported, one after mastectomy and the other after neurosurgery.8,9 Other cases of unilateral psoriasis are reported to have arisen in adolescents and young adults idiopathically.

A case of linear psoriasis arising in the distribution of the sciatic nerve in a patient with radiculopathy implicated tumor necrosis factor α, neuropeptides, and nerve growth factor released in response to compression as possible etiologic agents.10 However, none of the reported cases of linear psoriasis, or reported cases of unilateral psoriasis, exhibited verrucous features clinically or histologically. In our patient, distribution of the lesions appeared less typically blaschkoid than in linear psoriasis, and the presence of exophytic wartlike growths throughout the lesions was not characteristic of linear psoriasis.

Late-adulthood onset in this patient in addition to the absence of typical histologic features of ILVEN, including alternating orthokeratosis and parakeratosis,11 make a diagnosis of ILVEN less likely; ILVEN can be distinguished from linear psoriasis based on later age of onset and responsiveness to antipsoriatic therapy of linear psoriasis.12

Conclusion

We describe a unique presentation of an already rare variant of psoriasis that can be difficult to diagnose clinically. The unilateral distribution of lesions in this patient can create further diagnostic confusion with other entities, such as ILVEN and linear psoriasis, though it can be distinguished from those diseases based on histologic features. Our aim is that this report improves recognition of this unusual presentation of verrucous psoriasis in clinical settings and decreases delays in diagnosis and treatment.

- Khalil FK, Keehn CA, Saeed S, et al. Verrucous psoriasis: a distinctive clinicopathologic variant of psoriasis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:204-207.

- Wakamatsu K, Naniwa K, Hagiya Y, et al. Psoriasis verrucosa. J Dermatol. 2010;37:1060-1062.

- Monroe HR, Hillman JD, Chiu MW. A case of verrucous psoriasis. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:10.

- Maejima H, Katayama C, Watarai A, et al. A case of psoriasis verrucosa successfully treated with adalimumab. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:E74-E75.

- Erkek E, Bozdog˘an O. Annular verrucous psoriasis with exaggerated papillomatosis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2001;23:133-135.

- Hall L, Marks V, Tyler W. Verrucous psoriasis: a clinical and histopathologic mimicker of verruca vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68(4 suppl 1):AB218.

- Curtis AR, Yosipovitch G. Erythrodermic verrucous psoriasis. J Dermatolog Treat. 2012;23:215-218.

- Kim M, Jung JY, Na SY, et al. Unilateral psoriasis in a woman with ipsilateral post-mastectomy lymphedema. Ann Dermatol. 2011;23(suppl 3):S303-S305.

- Reyter I, Woodley D. Widespread unilateral plaques in a 68-year-old woman after neurosurgery. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:1531-1536.

- Galluzzo M, Talamonti M, Di Stefani A, et al. Linear psoriasis following the typical distribution of the sciatic nerve. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2015;9:6-11.

- Sengupta S, Das JK, Gangopadhyay A. Naevoid psoriasis and ILVEN: same coin, two faces? Indian J Dermatol. 2012;57:489-491.

- Morag C, Metzker A. Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus: report of seven new cases and review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 1985;3:15-18.

- Khalil FK, Keehn CA, Saeed S, et al. Verrucous psoriasis: a distinctive clinicopathologic variant of psoriasis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:204-207.

- Wakamatsu K, Naniwa K, Hagiya Y, et al. Psoriasis verrucosa. J Dermatol. 2010;37:1060-1062.

- Monroe HR, Hillman JD, Chiu MW. A case of verrucous psoriasis. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:10.

- Maejima H, Katayama C, Watarai A, et al. A case of psoriasis verrucosa successfully treated with adalimumab. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:E74-E75.

- Erkek E, Bozdog˘an O. Annular verrucous psoriasis with exaggerated papillomatosis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2001;23:133-135.

- Hall L, Marks V, Tyler W. Verrucous psoriasis: a clinical and histopathologic mimicker of verruca vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68(4 suppl 1):AB218.

- Curtis AR, Yosipovitch G. Erythrodermic verrucous psoriasis. J Dermatolog Treat. 2012;23:215-218.

- Kim M, Jung JY, Na SY, et al. Unilateral psoriasis in a woman with ipsilateral post-mastectomy lymphedema. Ann Dermatol. 2011;23(suppl 3):S303-S305.

- Reyter I, Woodley D. Widespread unilateral plaques in a 68-year-old woman after neurosurgery. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:1531-1536.

- Galluzzo M, Talamonti M, Di Stefani A, et al. Linear psoriasis following the typical distribution of the sciatic nerve. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2015;9:6-11.

- Sengupta S, Das JK, Gangopadhyay A. Naevoid psoriasis and ILVEN: same coin, two faces? Indian J Dermatol. 2012;57:489-491.

- Morag C, Metzker A. Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus: report of seven new cases and review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 1985;3:15-18.

Practice Points

- Verrucous psoriasis is a rare variant of psoriasis characterized by hypertrophic verrucous papules and plaques on an erythematous base.

- Histologically, verrucous psoriasis presents with overlapping features of verruca and psoriasis.

- Although psoriasis typically presents in a symmetric distribution, unilateral psoriasis can occur either de novo in younger patients or after surgical trauma in older patients.

Xanthogranulomatous Reaction to Trametinib for Metastatic Malignant Melanoma

A decade ago, the few agents approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for treatment of metastatic melanoma demonstrated low therapeutic success rates (ie, <15%–20%).1 Since then, advances in molecular biology have identified oncogenes that contribute to melanoma progression.2 Inhibition of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway by targeting mutant BRAF and mitogen-activated extracellular signal-regulated kinase (MEK) has created promising pharmacologic treatment opportunities.3 Due to the recent US Food and Drug Administration approval of these therapies for treatment of melanoma, it is important to better characterize these adverse events (AEs) so that we can manage them. We present the development of an unusual cutaneous reaction to trametinib, a MEK inhibitor, in a man with stage IV M1b malignant melanoma.

Case Report

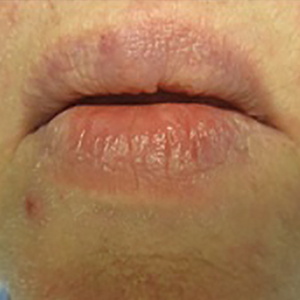

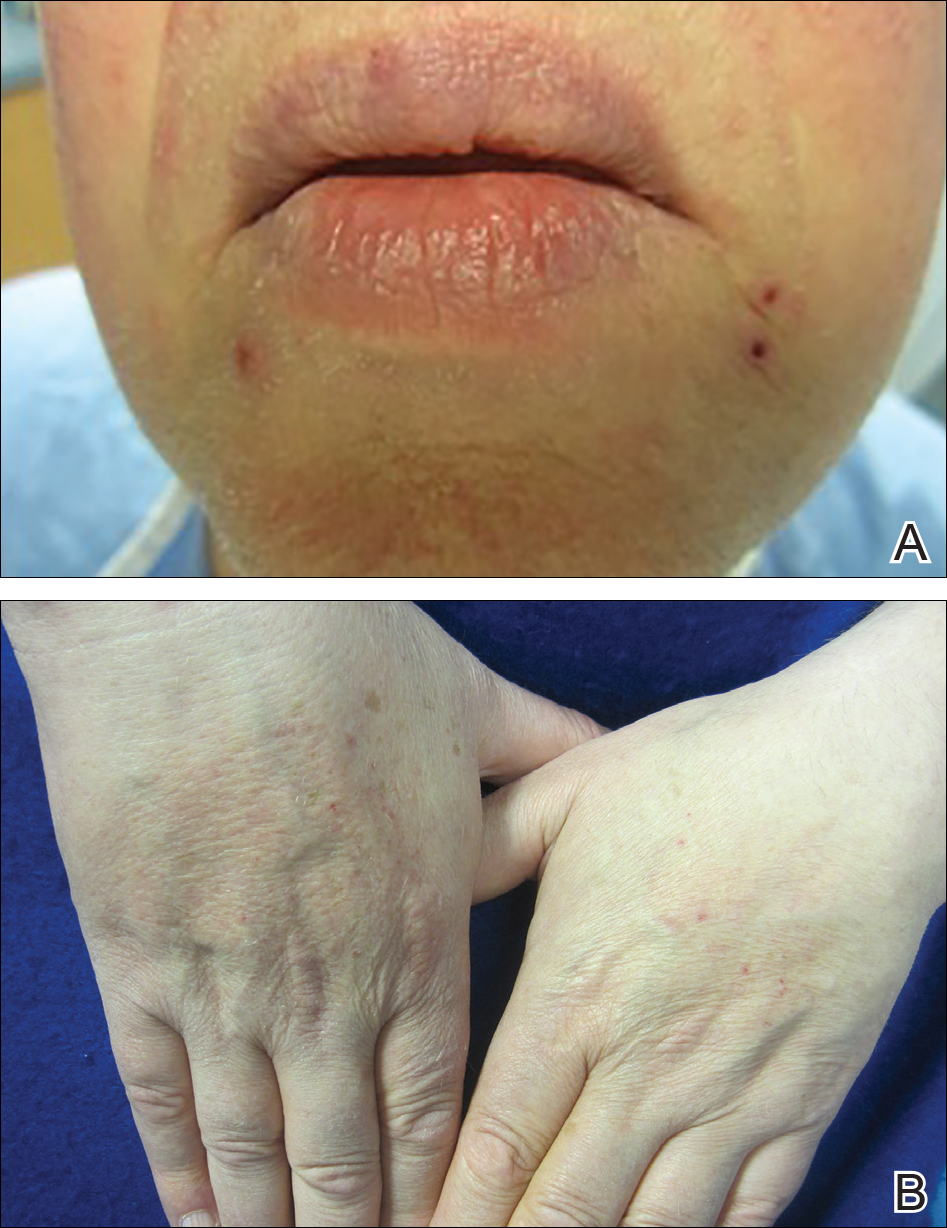

A 66-year-old man with stage IV M1b malignant melanoma with metastases to the brain and lungs presented with recurring pruritic erythematous papules on the face and bilateral forearms that began shortly after initiating therapy with trametinib. The cutaneous eruption had initially presented on the face, forearms, and dorsal hands when trametinib was used in combination with vemurafenib, a BRAF inhibitor, and ipilimumab, a human cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen 4–blocking antibody; however, lesions initially were minimal and self-resolving. When trametinib was reintroduced as monotherapy due to fever attributed to the combination treatment regimen, the cutaneous eruption recurred more severely. Physical examination revealed erythematous scaly papules limited to the face and bilateral upper extremities, including the flexural surfaces.

A biopsy from the flexural surface of the right forearm revealed a dense perivascular lymphoid and xanthomatous infiltrate in the dermis (Figure 1). Poorly formed granulomas within the mid reticular dermis demonstrated focal palisading of histiocytes with prominent giant cells at the periphery. Histiocytes and giant cells showed foamy or xanthomatous cytoplasm. Within the reaction, degenerative and swollen collagen fibers were noted with no mucin deposition, which was confirmed with negative colloidal iron staining.

Brief cessation of trametinib along with application of clobetasol propionate ointment 0.05% resulted in resolution of the cutaneous eruption. Later, trametinib was reintroduced in combination with vemurafenib, though therapy was intermittently discontinued due to various side effects. Skin lesions continued to recur (Figure 2) while the patient was on trametinib but remained minimal and continued to respond to topical clobetasol propionate. One year later, the patient continues to tolerate combination therapy with trametinib and vemurafenib.

Comment

BRAF Inhibitors

Normally, activated BRAF phosphorylates and stimulates MEK proteins, ultimately influencing cell proliferation, survival, and differentiation.3-5 BRAF mutations that constitutively activate this pathway have been detected in several malignancies, including papillary thyroid cancer, colorectal cancer, and brain tumors, but they are particularly prevalent in melanoma.4,6 The majority of BRAF-positive malignant melanomas are associated with V600E, in which valine is substituted for glutamic acid at codon 600. The next most common BRAF mutation is V600K, in which valine is substituted for lysine.2,7 Together these constitute approximately 95% of BRAF mutations in melanoma patients.5

MEK Inhibitors

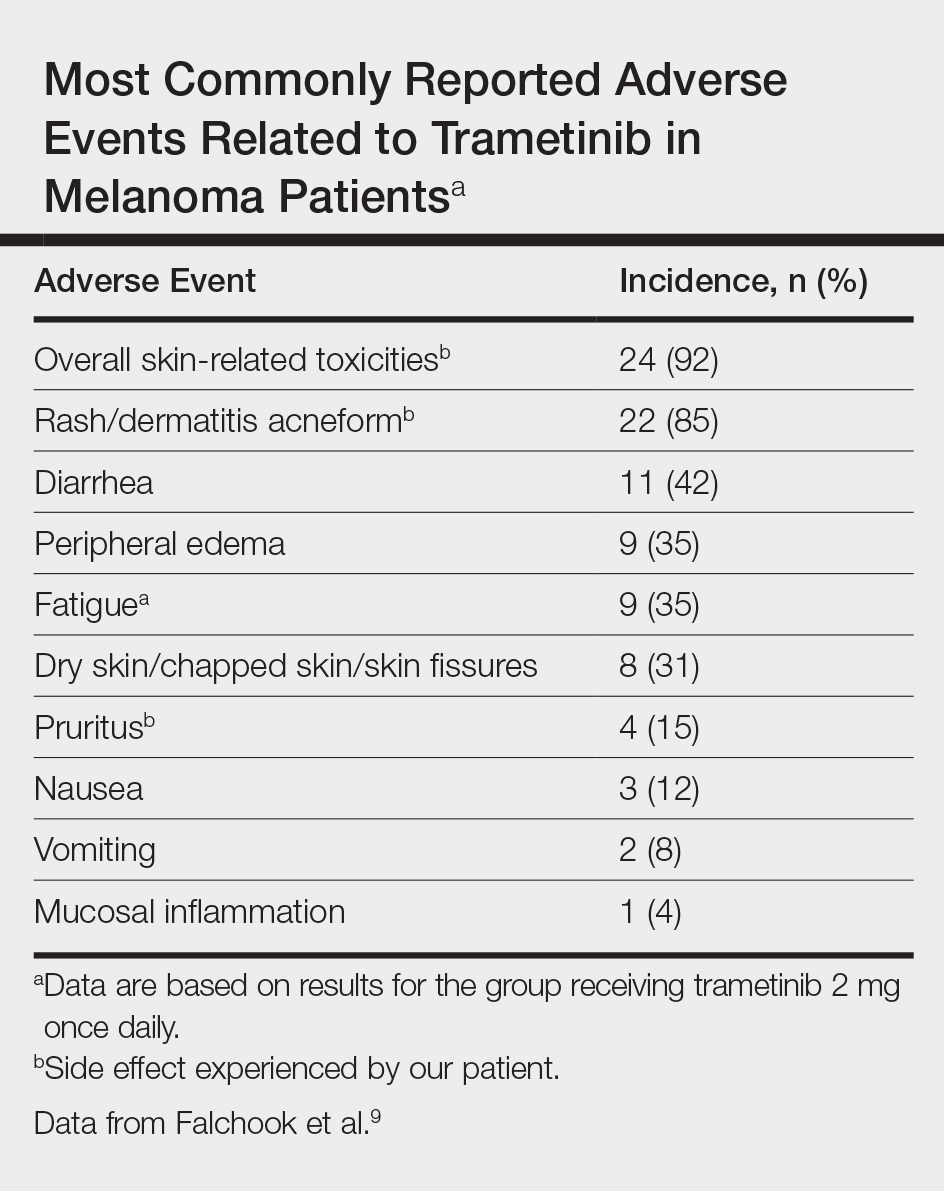

Initially, BRAF inhibitors (BRAFi) were introduced to the market for treating melanoma with great success; however, resistance to BRAFi therapy quickly was identified within months of initiating therapy, leading to investigations for combination therapy with MEK inhibitors (MEKi).2,5 MEK inhibition decreases cellular proliferation and also leads to apoptosis of melanoma cells in patients with BRAF V600E or V600K mutations.2,8 Trametinib, in particular, is a reversible, highly selective allosteric inhibitor of both MEK1 and MEK2. While on trametinib, patients with metastatic melanoma have experienced 3 times as long progression-free survival as well as 81% overall survival compared to 67% overall survival at 6 months in patients on chemotherapy, dacarbazine, or paclitaxel.5 However, AEs are quite common with trametinib, with cutaneous AEs being a leading side effect. Several large trials have reported that 57% to 92% of patients on trametinib report cutaneous AEs, with the majority of cases being described as papulopustular or acneform (Table).5,9

Combination Therapy

Fortunately, combination treatment with a BRAFi may alleviate MEKi-induced cutaneous drug reactions. In one study, acneform eruptions were identified in only 10% of those on combination therapy—trametinib with the BRAFi dabrafenib—compared to 77% of patients on trametinib monotherapy.10 Strikingly, cutaneous AEs occurred in 100% of trametinib-treated mice compared to 30% of combination-treated mice in another study, while the benefits of MEKi remained similar in both groups.11 Because BRAFi and MEKi combination therapy improves progression-free survival while minimizing AEs, we support the use of combination therapy instead of BRAFi or MEKi monotherapy.5

Histologic Evidence of AEs

Histology of trametinib-associated cutaneous reactions is not well characterized, which is in contrast to our understanding of cutaneous AEs associated with BRAFi in which transient acantholytic dermatosis (seen in 45% of patients) and verrucal keratosis (seen in 18% of patients) have been well characterized on histology.12 Interestingly, cutaneous granulomatous eruptions have been attributed to BRAFi therapy in 4 patients.13,14 One patient was on monotherapy with vemurafenib and granulomatous dermatitis with focal necrosis was seen on histology.13 The other 3 patients were on combination therapy with trametinib; 2 had histology-proven sarcoidal granulomatous inflammation, and 1 demonstrated perifollicular granulomatous inflammation and granulomatous inflammation surrounding a focus of melanoma cells.13,14 Although these granulomatous reactions were attributed to BRAFi or combination therapy, the association with trametinib remains unclear. On the other hand, our patient’s granulomatous reaction was exacerbated on trametinib monotherapy, suggesting a relationship to trametinib itself rather than BRAFi.

Conclusion

With the discovery of molecular targeting in melanoma, BRAFi and MEKi therapies provide major milestones in metastatic melanoma management. As more patients are treated with these agents, it is important that we better characterize their associated side effects. Our case of an unusual xanthogranulomatous reaction to trametinib adds to the knowledge base of possible cutaneous reactions caused by this drug. We hope that prospective studies will further investigate and differentiate the cutaneous AEs described so that we can better manage these patients.

- Eggermont AM, Schadendorf D. Melanoma and immunotherapy. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2009;23:547-564.

- Chung C, Reilly S. Trametinib: a novel signal transduction inhibitors for the treatment of metastatic cutaneous melanoma. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2015;72:101-110.

- Montagut C, Settleman J. Targeting the RAF-MEK-ERK pathway in cancer therapy [published online February 12, 2009]. Cancer Lett. 2009;283:125-134.

- Hertzman Johansson C, Egyhazi Brage S. BRAF inhibitors in cancer therapy [published online December 8, 2013]. Pharmacol Ther. 2014;142:176-182.

- Flaherty KT, Robert C, Hersey P, et al; METRIC Study Group. Improved survival with MEK inhibition in BRAF-mutated melanoma [published online June 4, 2012]. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:107-114.

- Davies H, Bignell GR, Cox C, et al. Mutations of the BRAF gene in human cancer [published online June 9, 2002]. Nature. 2002;417:949-954.

- Houben R, Becker JC, Kappel A, et al. Constitutive activation of the Ras-Raf signaling pathway in metastatic melanoma is associated with poor prognosis. J Carcinog. 2004;3:6.

- Roberts PF, Der CJ. Targeting the Raf-MEK-ERK mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade for the treatment of cancer. Oncogene. 2007;26:3291-3310.

- Falchook GS, Lewis KD, Infante JR, et al. Activity of the oral MEK inhibitor trametinib in patients with advanced melanoma: a phase 2 dose-escalation trial [published online July 16, 2012]. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:782-789.

- Anforth R, Liu M, Nguyen B, et al. Acneiform eruptions: a common cutaneous toxicity of the MEK inhibitor trametinib [published online December 9, 2013]. Australas J Dermatol. 2014;55:250-254.

- Gadiot J, Hooijkaas AI, Deken MA, et al. Synchronous BRAF(V600E) and MEK inhibition leads to superior control of murine melanoma by limiting MEK inhibitor induced skin toxicity. Onco Targets Ther. 2013;6:1649-1658.

- Anforth R, Carlos G, Clements A, et al. Cutaneous adverse events in patients treated with BRAF inhibitor-based therapies for metastatic melanoma for longer than 52 weeks [published online November 21, 2014]. Br J Dermatol. 2015;172:239-243.

- Park JJ, Hawryluk EB, Tahan SR, et al. Cutaneous granulomatous eruption and successful response to potent topical steroids in patients undergoing targeted BRAF inhibitor treatment for metastatic melanoma. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:307-311.

- Green JS, Norris DA, Wisell K. Novel cutaneous effects of combination chemotherapy with BRAF and MEK inhibitors: a report of two cases. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:172-176.

A decade ago, the few agents approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for treatment of metastatic melanoma demonstrated low therapeutic success rates (ie, <15%–20%).1 Since then, advances in molecular biology have identified oncogenes that contribute to melanoma progression.2 Inhibition of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway by targeting mutant BRAF and mitogen-activated extracellular signal-regulated kinase (MEK) has created promising pharmacologic treatment opportunities.3 Due to the recent US Food and Drug Administration approval of these therapies for treatment of melanoma, it is important to better characterize these adverse events (AEs) so that we can manage them. We present the development of an unusual cutaneous reaction to trametinib, a MEK inhibitor, in a man with stage IV M1b malignant melanoma.

Case Report

A 66-year-old man with stage IV M1b malignant melanoma with metastases to the brain and lungs presented with recurring pruritic erythematous papules on the face and bilateral forearms that began shortly after initiating therapy with trametinib. The cutaneous eruption had initially presented on the face, forearms, and dorsal hands when trametinib was used in combination with vemurafenib, a BRAF inhibitor, and ipilimumab, a human cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen 4–blocking antibody; however, lesions initially were minimal and self-resolving. When trametinib was reintroduced as monotherapy due to fever attributed to the combination treatment regimen, the cutaneous eruption recurred more severely. Physical examination revealed erythematous scaly papules limited to the face and bilateral upper extremities, including the flexural surfaces.

A biopsy from the flexural surface of the right forearm revealed a dense perivascular lymphoid and xanthomatous infiltrate in the dermis (Figure 1). Poorly formed granulomas within the mid reticular dermis demonstrated focal palisading of histiocytes with prominent giant cells at the periphery. Histiocytes and giant cells showed foamy or xanthomatous cytoplasm. Within the reaction, degenerative and swollen collagen fibers were noted with no mucin deposition, which was confirmed with negative colloidal iron staining.

Brief cessation of trametinib along with application of clobetasol propionate ointment 0.05% resulted in resolution of the cutaneous eruption. Later, trametinib was reintroduced in combination with vemurafenib, though therapy was intermittently discontinued due to various side effects. Skin lesions continued to recur (Figure 2) while the patient was on trametinib but remained minimal and continued to respond to topical clobetasol propionate. One year later, the patient continues to tolerate combination therapy with trametinib and vemurafenib.

Comment

BRAF Inhibitors

Normally, activated BRAF phosphorylates and stimulates MEK proteins, ultimately influencing cell proliferation, survival, and differentiation.3-5 BRAF mutations that constitutively activate this pathway have been detected in several malignancies, including papillary thyroid cancer, colorectal cancer, and brain tumors, but they are particularly prevalent in melanoma.4,6 The majority of BRAF-positive malignant melanomas are associated with V600E, in which valine is substituted for glutamic acid at codon 600. The next most common BRAF mutation is V600K, in which valine is substituted for lysine.2,7 Together these constitute approximately 95% of BRAF mutations in melanoma patients.5

MEK Inhibitors

Initially, BRAF inhibitors (BRAFi) were introduced to the market for treating melanoma with great success; however, resistance to BRAFi therapy quickly was identified within months of initiating therapy, leading to investigations for combination therapy with MEK inhibitors (MEKi).2,5 MEK inhibition decreases cellular proliferation and also leads to apoptosis of melanoma cells in patients with BRAF V600E or V600K mutations.2,8 Trametinib, in particular, is a reversible, highly selective allosteric inhibitor of both MEK1 and MEK2. While on trametinib, patients with metastatic melanoma have experienced 3 times as long progression-free survival as well as 81% overall survival compared to 67% overall survival at 6 months in patients on chemotherapy, dacarbazine, or paclitaxel.5 However, AEs are quite common with trametinib, with cutaneous AEs being a leading side effect. Several large trials have reported that 57% to 92% of patients on trametinib report cutaneous AEs, with the majority of cases being described as papulopustular or acneform (Table).5,9

Combination Therapy

Fortunately, combination treatment with a BRAFi may alleviate MEKi-induced cutaneous drug reactions. In one study, acneform eruptions were identified in only 10% of those on combination therapy—trametinib with the BRAFi dabrafenib—compared to 77% of patients on trametinib monotherapy.10 Strikingly, cutaneous AEs occurred in 100% of trametinib-treated mice compared to 30% of combination-treated mice in another study, while the benefits of MEKi remained similar in both groups.11 Because BRAFi and MEKi combination therapy improves progression-free survival while minimizing AEs, we support the use of combination therapy instead of BRAFi or MEKi monotherapy.5

Histologic Evidence of AEs

Histology of trametinib-associated cutaneous reactions is not well characterized, which is in contrast to our understanding of cutaneous AEs associated with BRAFi in which transient acantholytic dermatosis (seen in 45% of patients) and verrucal keratosis (seen in 18% of patients) have been well characterized on histology.12 Interestingly, cutaneous granulomatous eruptions have been attributed to BRAFi therapy in 4 patients.13,14 One patient was on monotherapy with vemurafenib and granulomatous dermatitis with focal necrosis was seen on histology.13 The other 3 patients were on combination therapy with trametinib; 2 had histology-proven sarcoidal granulomatous inflammation, and 1 demonstrated perifollicular granulomatous inflammation and granulomatous inflammation surrounding a focus of melanoma cells.13,14 Although these granulomatous reactions were attributed to BRAFi or combination therapy, the association with trametinib remains unclear. On the other hand, our patient’s granulomatous reaction was exacerbated on trametinib monotherapy, suggesting a relationship to trametinib itself rather than BRAFi.

Conclusion

With the discovery of molecular targeting in melanoma, BRAFi and MEKi therapies provide major milestones in metastatic melanoma management. As more patients are treated with these agents, it is important that we better characterize their associated side effects. Our case of an unusual xanthogranulomatous reaction to trametinib adds to the knowledge base of possible cutaneous reactions caused by this drug. We hope that prospective studies will further investigate and differentiate the cutaneous AEs described so that we can better manage these patients.

A decade ago, the few agents approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for treatment of metastatic melanoma demonstrated low therapeutic success rates (ie, <15%–20%).1 Since then, advances in molecular biology have identified oncogenes that contribute to melanoma progression.2 Inhibition of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway by targeting mutant BRAF and mitogen-activated extracellular signal-regulated kinase (MEK) has created promising pharmacologic treatment opportunities.3 Due to the recent US Food and Drug Administration approval of these therapies for treatment of melanoma, it is important to better characterize these adverse events (AEs) so that we can manage them. We present the development of an unusual cutaneous reaction to trametinib, a MEK inhibitor, in a man with stage IV M1b malignant melanoma.

Case Report

A 66-year-old man with stage IV M1b malignant melanoma with metastases to the brain and lungs presented with recurring pruritic erythematous papules on the face and bilateral forearms that began shortly after initiating therapy with trametinib. The cutaneous eruption had initially presented on the face, forearms, and dorsal hands when trametinib was used in combination with vemurafenib, a BRAF inhibitor, and ipilimumab, a human cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen 4–blocking antibody; however, lesions initially were minimal and self-resolving. When trametinib was reintroduced as monotherapy due to fever attributed to the combination treatment regimen, the cutaneous eruption recurred more severely. Physical examination revealed erythematous scaly papules limited to the face and bilateral upper extremities, including the flexural surfaces.

A biopsy from the flexural surface of the right forearm revealed a dense perivascular lymphoid and xanthomatous infiltrate in the dermis (Figure 1). Poorly formed granulomas within the mid reticular dermis demonstrated focal palisading of histiocytes with prominent giant cells at the periphery. Histiocytes and giant cells showed foamy or xanthomatous cytoplasm. Within the reaction, degenerative and swollen collagen fibers were noted with no mucin deposition, which was confirmed with negative colloidal iron staining.

Brief cessation of trametinib along with application of clobetasol propionate ointment 0.05% resulted in resolution of the cutaneous eruption. Later, trametinib was reintroduced in combination with vemurafenib, though therapy was intermittently discontinued due to various side effects. Skin lesions continued to recur (Figure 2) while the patient was on trametinib but remained minimal and continued to respond to topical clobetasol propionate. One year later, the patient continues to tolerate combination therapy with trametinib and vemurafenib.

Comment

BRAF Inhibitors

Normally, activated BRAF phosphorylates and stimulates MEK proteins, ultimately influencing cell proliferation, survival, and differentiation.3-5 BRAF mutations that constitutively activate this pathway have been detected in several malignancies, including papillary thyroid cancer, colorectal cancer, and brain tumors, but they are particularly prevalent in melanoma.4,6 The majority of BRAF-positive malignant melanomas are associated with V600E, in which valine is substituted for glutamic acid at codon 600. The next most common BRAF mutation is V600K, in which valine is substituted for lysine.2,7 Together these constitute approximately 95% of BRAF mutations in melanoma patients.5

MEK Inhibitors

Initially, BRAF inhibitors (BRAFi) were introduced to the market for treating melanoma with great success; however, resistance to BRAFi therapy quickly was identified within months of initiating therapy, leading to investigations for combination therapy with MEK inhibitors (MEKi).2,5 MEK inhibition decreases cellular proliferation and also leads to apoptosis of melanoma cells in patients with BRAF V600E or V600K mutations.2,8 Trametinib, in particular, is a reversible, highly selective allosteric inhibitor of both MEK1 and MEK2. While on trametinib, patients with metastatic melanoma have experienced 3 times as long progression-free survival as well as 81% overall survival compared to 67% overall survival at 6 months in patients on chemotherapy, dacarbazine, or paclitaxel.5 However, AEs are quite common with trametinib, with cutaneous AEs being a leading side effect. Several large trials have reported that 57% to 92% of patients on trametinib report cutaneous AEs, with the majority of cases being described as papulopustular or acneform (Table).5,9

Combination Therapy

Fortunately, combination treatment with a BRAFi may alleviate MEKi-induced cutaneous drug reactions. In one study, acneform eruptions were identified in only 10% of those on combination therapy—trametinib with the BRAFi dabrafenib—compared to 77% of patients on trametinib monotherapy.10 Strikingly, cutaneous AEs occurred in 100% of trametinib-treated mice compared to 30% of combination-treated mice in another study, while the benefits of MEKi remained similar in both groups.11 Because BRAFi and MEKi combination therapy improves progression-free survival while minimizing AEs, we support the use of combination therapy instead of BRAFi or MEKi monotherapy.5

Histologic Evidence of AEs

Histology of trametinib-associated cutaneous reactions is not well characterized, which is in contrast to our understanding of cutaneous AEs associated with BRAFi in which transient acantholytic dermatosis (seen in 45% of patients) and verrucal keratosis (seen in 18% of patients) have been well characterized on histology.12 Interestingly, cutaneous granulomatous eruptions have been attributed to BRAFi therapy in 4 patients.13,14 One patient was on monotherapy with vemurafenib and granulomatous dermatitis with focal necrosis was seen on histology.13 The other 3 patients were on combination therapy with trametinib; 2 had histology-proven sarcoidal granulomatous inflammation, and 1 demonstrated perifollicular granulomatous inflammation and granulomatous inflammation surrounding a focus of melanoma cells.13,14 Although these granulomatous reactions were attributed to BRAFi or combination therapy, the association with trametinib remains unclear. On the other hand, our patient’s granulomatous reaction was exacerbated on trametinib monotherapy, suggesting a relationship to trametinib itself rather than BRAFi.

Conclusion

With the discovery of molecular targeting in melanoma, BRAFi and MEKi therapies provide major milestones in metastatic melanoma management. As more patients are treated with these agents, it is important that we better characterize their associated side effects. Our case of an unusual xanthogranulomatous reaction to trametinib adds to the knowledge base of possible cutaneous reactions caused by this drug. We hope that prospective studies will further investigate and differentiate the cutaneous AEs described so that we can better manage these patients.

- Eggermont AM, Schadendorf D. Melanoma and immunotherapy. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2009;23:547-564.

- Chung C, Reilly S. Trametinib: a novel signal transduction inhibitors for the treatment of metastatic cutaneous melanoma. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2015;72:101-110.

- Montagut C, Settleman J. Targeting the RAF-MEK-ERK pathway in cancer therapy [published online February 12, 2009]. Cancer Lett. 2009;283:125-134.

- Hertzman Johansson C, Egyhazi Brage S. BRAF inhibitors in cancer therapy [published online December 8, 2013]. Pharmacol Ther. 2014;142:176-182.

- Flaherty KT, Robert C, Hersey P, et al; METRIC Study Group. Improved survival with MEK inhibition in BRAF-mutated melanoma [published online June 4, 2012]. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:107-114.

- Davies H, Bignell GR, Cox C, et al. Mutations of the BRAF gene in human cancer [published online June 9, 2002]. Nature. 2002;417:949-954.

- Houben R, Becker JC, Kappel A, et al. Constitutive activation of the Ras-Raf signaling pathway in metastatic melanoma is associated with poor prognosis. J Carcinog. 2004;3:6.

- Roberts PF, Der CJ. Targeting the Raf-MEK-ERK mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade for the treatment of cancer. Oncogene. 2007;26:3291-3310.

- Falchook GS, Lewis KD, Infante JR, et al. Activity of the oral MEK inhibitor trametinib in patients with advanced melanoma: a phase 2 dose-escalation trial [published online July 16, 2012]. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:782-789.

- Anforth R, Liu M, Nguyen B, et al. Acneiform eruptions: a common cutaneous toxicity of the MEK inhibitor trametinib [published online December 9, 2013]. Australas J Dermatol. 2014;55:250-254.

- Gadiot J, Hooijkaas AI, Deken MA, et al. Synchronous BRAF(V600E) and MEK inhibition leads to superior control of murine melanoma by limiting MEK inhibitor induced skin toxicity. Onco Targets Ther. 2013;6:1649-1658.

- Anforth R, Carlos G, Clements A, et al. Cutaneous adverse events in patients treated with BRAF inhibitor-based therapies for metastatic melanoma for longer than 52 weeks [published online November 21, 2014]. Br J Dermatol. 2015;172:239-243.

- Park JJ, Hawryluk EB, Tahan SR, et al. Cutaneous granulomatous eruption and successful response to potent topical steroids in patients undergoing targeted BRAF inhibitor treatment for metastatic melanoma. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:307-311.

- Green JS, Norris DA, Wisell K. Novel cutaneous effects of combination chemotherapy with BRAF and MEK inhibitors: a report of two cases. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:172-176.

- Eggermont AM, Schadendorf D. Melanoma and immunotherapy. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2009;23:547-564.

- Chung C, Reilly S. Trametinib: a novel signal transduction inhibitors for the treatment of metastatic cutaneous melanoma. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2015;72:101-110.

- Montagut C, Settleman J. Targeting the RAF-MEK-ERK pathway in cancer therapy [published online February 12, 2009]. Cancer Lett. 2009;283:125-134.

- Hertzman Johansson C, Egyhazi Brage S. BRAF inhibitors in cancer therapy [published online December 8, 2013]. Pharmacol Ther. 2014;142:176-182.

- Flaherty KT, Robert C, Hersey P, et al; METRIC Study Group. Improved survival with MEK inhibition in BRAF-mutated melanoma [published online June 4, 2012]. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:107-114.

- Davies H, Bignell GR, Cox C, et al. Mutations of the BRAF gene in human cancer [published online June 9, 2002]. Nature. 2002;417:949-954.

- Houben R, Becker JC, Kappel A, et al. Constitutive activation of the Ras-Raf signaling pathway in metastatic melanoma is associated with poor prognosis. J Carcinog. 2004;3:6.

- Roberts PF, Der CJ. Targeting the Raf-MEK-ERK mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade for the treatment of cancer. Oncogene. 2007;26:3291-3310.

- Falchook GS, Lewis KD, Infante JR, et al. Activity of the oral MEK inhibitor trametinib in patients with advanced melanoma: a phase 2 dose-escalation trial [published online July 16, 2012]. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:782-789.

- Anforth R, Liu M, Nguyen B, et al. Acneiform eruptions: a common cutaneous toxicity of the MEK inhibitor trametinib [published online December 9, 2013]. Australas J Dermatol. 2014;55:250-254.

- Gadiot J, Hooijkaas AI, Deken MA, et al. Synchronous BRAF(V600E) and MEK inhibition leads to superior control of murine melanoma by limiting MEK inhibitor induced skin toxicity. Onco Targets Ther. 2013;6:1649-1658.

- Anforth R, Carlos G, Clements A, et al. Cutaneous adverse events in patients treated with BRAF inhibitor-based therapies for metastatic melanoma for longer than 52 weeks [published online November 21, 2014]. Br J Dermatol. 2015;172:239-243.

- Park JJ, Hawryluk EB, Tahan SR, et al. Cutaneous granulomatous eruption and successful response to potent topical steroids in patients undergoing targeted BRAF inhibitor treatment for metastatic melanoma. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:307-311.

- Green JS, Norris DA, Wisell K. Novel cutaneous effects of combination chemotherapy with BRAF and MEK inhibitors: a report of two cases. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:172-176.

Practice Points

- With the discovery of molecular targeting in melanoma, BRAF and MEK inhibitors have been increasingly utilized as therapies in metastatic melanoma management.

- Trametinib, a MEK inhibitor, is commonly associated with cutaneous adverse reactions, particularly acneform eruptions.

- We report a patient on trametinib who developed an eruption with an unusual xanthogranulomatous reaction pattern noted on histology.