User login

Revisiting our approach to behavioral health referrals

Approximately 1 in 4 people ages 18 years and older and 1 in 3 people ages 18 to 25 years had a mental illness in the past year, according to the 2021 National Survey of Drug Use and Health.1 The survey also found that adults ages 18 to 25 years had the highest rate of serious mental illness but the lowest treatment rate compared to other adult age groups.1 Unfortunately, more than 60% of patients receiving mental health treatment fail to benefit to a clinically meaningful degree.2

However, there is growing evidence that referring patients to behavioral health practitioners (BHPs) with outcome-measured skills that meet the patient’s specific needs can have a dramatic and positive impact. There are 2 main steps to pairing patients with an appropriate BHP: (1) use of measurement-based care data that can be analyzed at the patient and therapist level, and (2) data-driven referrals that pair patients with BHPs based on such routine outcome monitoring data (paired-on outcome data).

Psychotherapy’s slow road toward measurement-based care

Routine outcome monitoring is the systematic measurement of symptoms and functioning during treatment. It serves multiple functions, including program evaluation and benchmarking of patient improvement rates. Moreover, routine outcome monitoring–derived feedback (based on repeated patient outcome measurements) can inform personalized and responsive care decisions throughout treatment.

For all intents and purposes,

- routinely administered symptom/functioning measure, ideally before each clinical encounter,

- practitioner review of these patient-level data,

- patient review of these data with their practitioner, and

- collaborative reevaluation of the person-specific treatment plan informed by these data.

CASE SCENARIO

Violeta W is a 33-year-old woman who presented to her family physician for her annual wellness exam. Prior to the exam, the medical assistant administered a Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) to screen for depressive symptoms. Ms. W’s score was 20 out of 27, suggestive of depression. To further assess the severity of depressive symptoms and their effect on daily function, the physician reviewed responses to the questionnaire with her and discussed treatment options. Ms. W was most interested in trying a low-dose selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI).

At her follow-up visit 4 weeks later, the medical assistant re-administered the PHQ-9. The physician then reviewed Ms. W’s responses with her and, based on Ms. W’s subjective report and objective symptoms (still a score of 20 out of 27 on the PHQ-9), increased her SSRI dose. At each subsequent visit, Ms. W completed a PHQ-9 and reviewed responses and depressive symptoms with her physician.

The value of measurement-based care in mental health care

A narrative review by Lewis et al3 of 21 randomized controlled clinical trials (RCTs) across a range of age groups (eg, adolescents, young adults, adults), disorders (eg, anxiety, mood), and settings (eg, outpatient, inpatient) found that in at least 9 review articles, measurement-based care was associated with significantly improved outcomes vs usual care (ie, treatment without routine outcome monitoring plus feedback). The average increase in treatment effect size was about 30% when treatment was accompanied by measurement-based care.3

Continue to: Moreover, a recent within-patient meta-analysis...

Moreover, a recent within-patient meta-analysis by de Jong et al4 shows that measurement-based care yields a small but significant increase in therapeutic outcomes (d = .15). Use of measurement-based care also is associated with improved communication between the patient and therapist.5 In pharmacotherapy practice, measurement-based care has been shown to predict rapid dose increases and changes in medication, when necessary; faster recovery rates; higher response rates to treatment3; and fewer dropouts.4

Perhaps one of the best-studied benefits of measurement-based mental health care is the ability to predict deterioration in care (ie, patients who are off-track in a way that practitioners often miss without the help of routine outcome monitoring data).6,7 Studies show that without a data-informed approach to care, some forms of psychotherapy or therapy with BHPs who are not sufficiently skilled in treating a given diagnosis increase symptoms or create significant harmful and iatrogenic effects.8-10 Conversely, the meta-analysis by de Jong et al4 found a lower percentage of deterioration in patients receiving measurement-based care. The difference in deterioration was significant: An average of 5.4% of patients in control conditions deteriorated compared to an average of 4.6% in feedback (measurement-based care) groups. There were even larger effect sizes when therapists received training in the feedback system.4

Routine outcome monitoring without a dialogue between patient and practitioner about the assessments (eg, ignoring complete measurement-based care requirements) may be inadequate. A recent review by Muir et al6 found no differences in patient outcomes when data were used solely for aggregate quality improvement activities, suggesting the need for practitioners to review results of routine outcome monitoring assessments with patients and use data to alter care when necessary.

Measurement-based care is believed to deliver benefits and reduce harm by enhancing and encouraging active patient involvement, improving patient understanding of symptoms, promoting better communication, and facilitating better care coordination.3 The benefits of measurement-based care can be enhanced with a comprehensive core routine outcome monitoring tool and the level of monitoring-generated information delivered for multiple stakeholders (eg, patient, therapist, clinic).11

A look at multidimensional assessment

The features of routine outcome monitoring tools vary significantly.12 Some measures assess single-symptom or problem domains (eg, PHQ-9 for depression or Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 [GAD-7] scale for anxiety) or multiple dimensions (multidimensional routine outcome monitoring).Multidimensional routine outcome monitoring may have benefits over single-domain measures. Single-domain measures and the subscales or factors of more comprehensive multidimensional routine outcome monitoring assessments should possess adequate specificity and sensitivity.

Continue to: Some recent research findings...

Some recent research findings question the construct validity of brief single-domain measures of common presenting problems, such as depression and anxiety. For example, results from a factor analysis of the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 scale in patients with traumatic brain injury suggest these tools measure 1 psychological construct that includes depression and the cognitive components of anxiety (eg, worry)13—a finding consistent with those of other tools.14 Similarly, a larger study of 7763 BH patients found that a single factor accounted for most of the variance of the 2 combined measures, with no set of factors meeting the exacting standards used to develop multidimensional routine outcome monitoring.15 These findings suggest that the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 largely overlap and are not measuring different aspects of health as most practitioners believe (eg, depression and anxiety).

In commonly used assessments, multiple-factor analytic studies with high standards have supported the construct validity of domain-specific subscales, indicating that the various questions tap into different constructs of psychological health.14,16,17

Beyond multiple domain–specific indicators, multidimensional routine outcome measurements provide a global total score that minimizes Type I (false-positive conclusion) and Type II (false-negative conclusion) errors in tracking patient improvement or deterioration.18 As one would expect, multidimensional routine outcome monitoring generally includes more items than single-domain measures; however, this comes with a trade-off. If there are specificity and sensitivity concerns with an ultra-brief single-domain measure, an alternative to a core multidimensional routine outcome measurement is to aggregate a series of single-domain measures into a battery of patient self-reports. However, this approach may take longer for patients to complete since they would have to shift among the varying response sets and wording across the unique single-domain measures.

In addition, the standardization/normalization of multidimensional routine outcome monitoring likely makes interpretation easier than referring to norms and clinical severity cutoffs for many distinct measures. Furthermore, increased specificity enhances predictive power and allows BHPs to screen and track other conditions besides depression and anxiety. (It is worth noting that there are no known studies that have looked at the difference in time to administer or ease of interpretation of multidimensional routine outcome monitoring tools vs multiple single-domain measures.)

Two multidimensional routine outcome monitoring tools that cover a comprehensive series of discrete symptom and functional domains are the Treatment Outcome Package12 and Counseling Center Assessment of Psychological Symptoms.16 These tools, which include subscales beyond general depression and anxiety (eg, sleep, substance misuse, social conflict), take 7 to 10 minutes to complete and provide outcome results across 12 symptom and 8 functional dimensions. As an example, the Treatment Outcome Package has good psychometric qualities (eg, reliability, construct and concurrent validity) for adults,12 children,14,19 and adolescents,19 and can be administered through a secure online data collection portal. The Counseling Center Assessment of Psychological Symptoms has demonstrated high construct validity and good convergent validity.16 These assessments can be administered in paper or digital (eg, electronic medical record portal, smartphone) format.20

Continue to: CASE SCENARIO

CASE SCENARIO

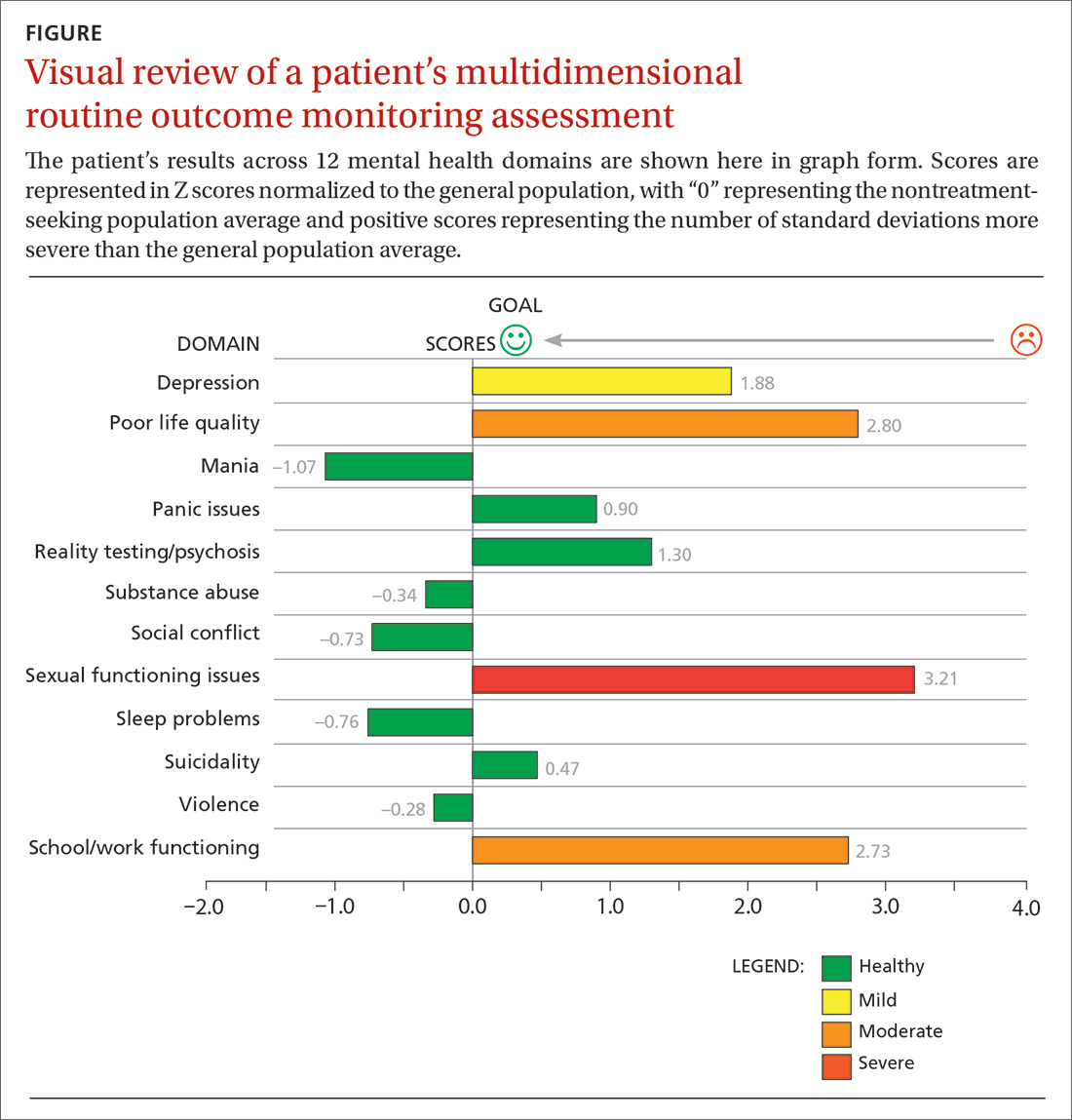

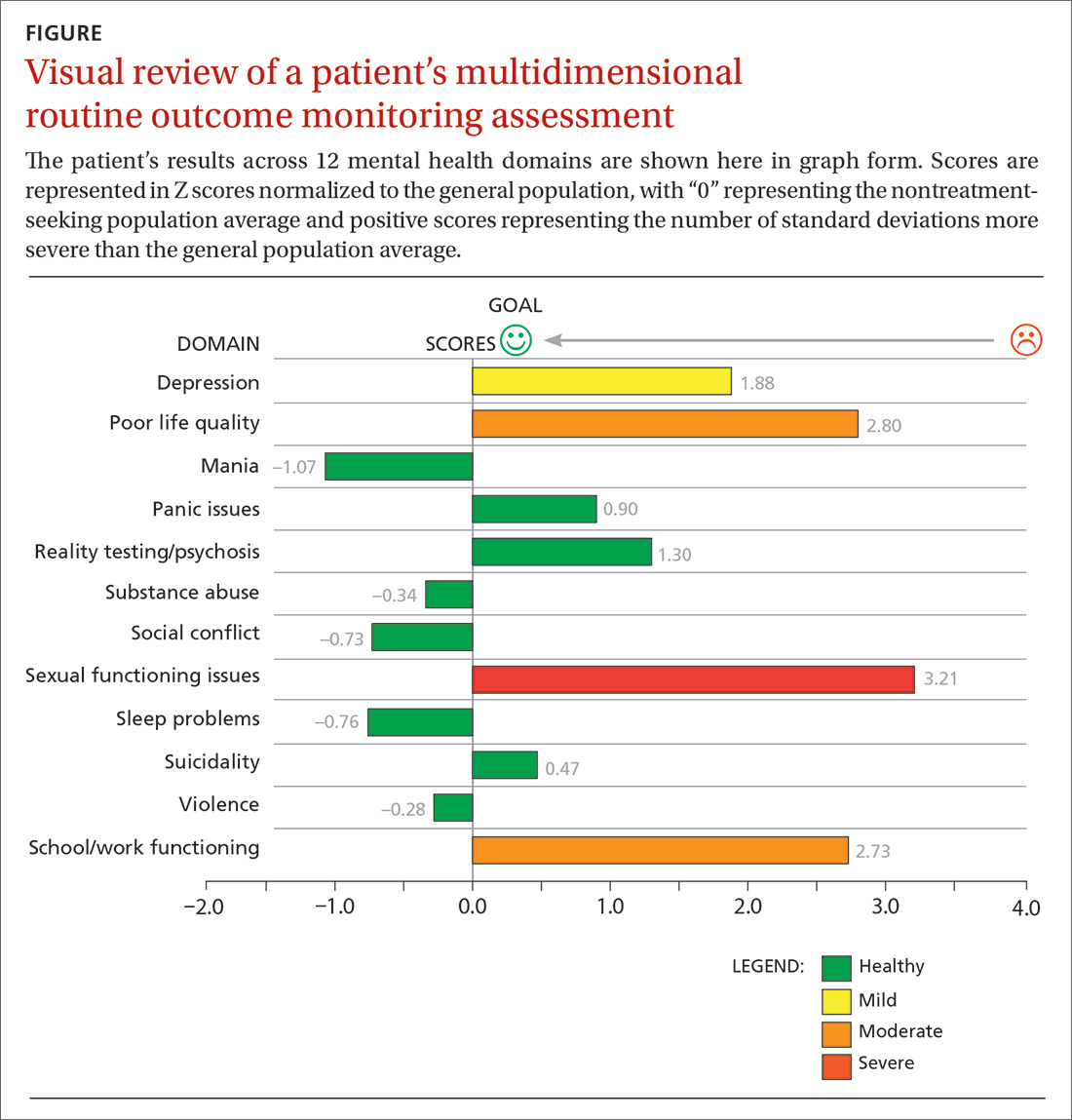

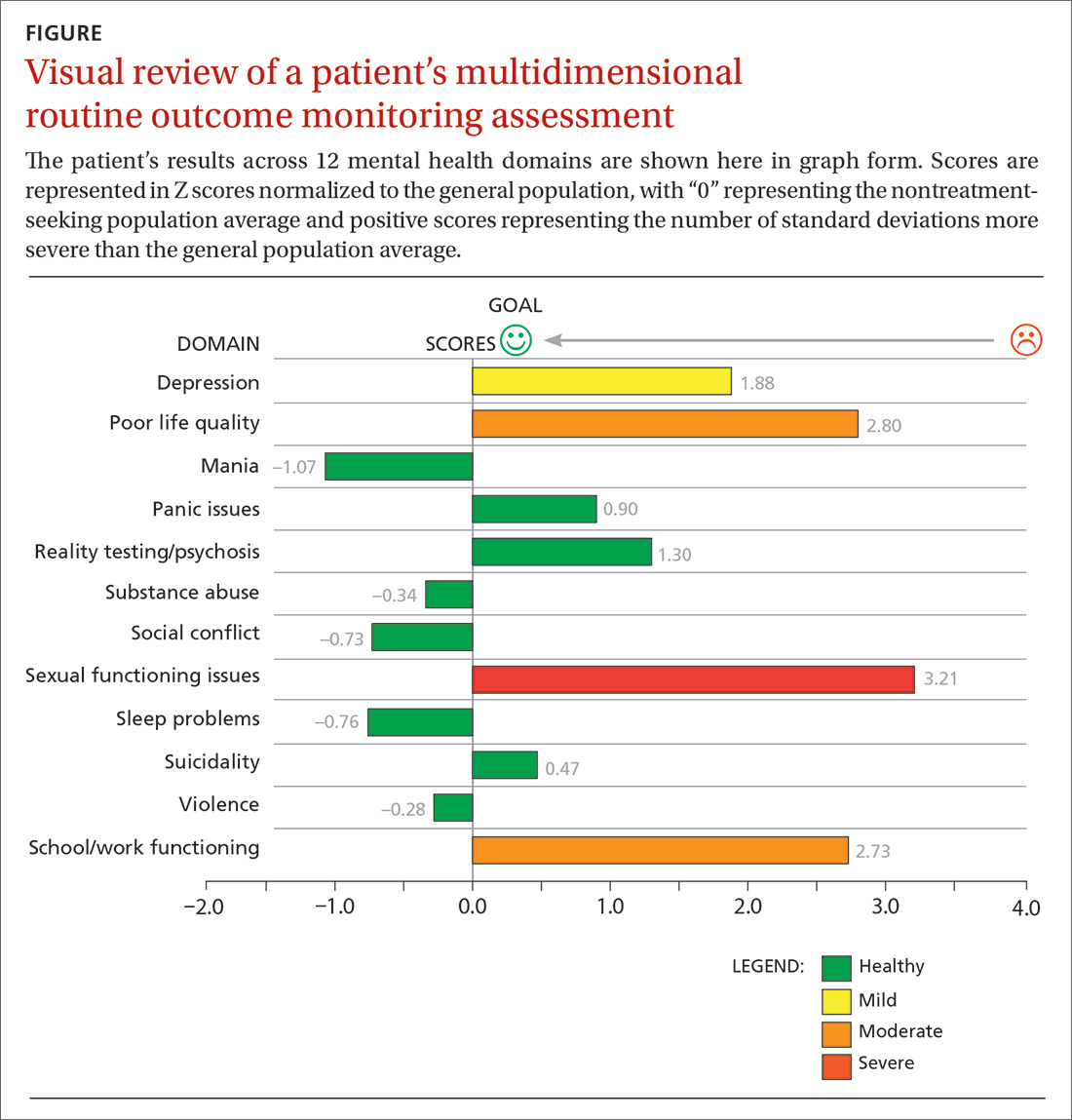

Ms. W’s physician asked her to go online using her phone and answer the questions in the Treatment Outcome Package. Her results, which she viewed with her physician, were displayed in graph form (FIGURE). Her scores were represented in Z scores normalized to the general population, with “0” representing the general, nontreatment-seeking population average and positive scores representing the number of standard deviations (SDs) more severe than the general population average.

Although this assessment scored Ms. W’s clinically elevated depression as mild, it revealed abnormalities in 3 other domains. Sexual functioning issues represented the most abnormal domain at greater than 3 SDs (more severe than the general population), followed by poor life quality and school/work functioning.

After reviewing Ms. W’s report, her physician decided that pharmacologic management alone (for depression) was not the most appropriate treatment course. Therefore, her physician recommended psychotherapy in addition to the SSRI she was taking. Ms. W agreed to a customized referral for psychotherapy.

Data-driven referrals

When psychotherapy is chosen as a treatment, the individual BHP is an active component of that treatment. Consequently, it is essential to customize referrals to match a patient’s most elevated mental health concerns with a therapist who will most effectively treat those domains. It is rare for a BHP to be skilled in treating every mental health domain.9 Multiple studies have shown that BHPs have identifiable treatment skills in specific domains, which physicians should consider when making referrals.9,21,22 These studies demonstrate the utility of aggregating patient-level routine outcome monitoring data to better understand therapist-level (and ultimately clinic- and system-level) outcomes.

Additionally, recent research has tested this idea prospectively. An RCT funded by the Patient-Centered Outcome Research Institute and published in JAMA Psychiatry showed a significant and positive effect on patient outcomes (ie, reductions in general impairment, impairment involving a patient’s most elevated domain, and global distress) using paired-on outcome data matching vs as-usual matching protocols (eg, therapist self-defined areas of specialty).22 In the RCT, the most effective matching protocol was a combination of eliminating harm and matching the patient on their 3 most problematic domains (the highest match level). These patients ended care as healthy as the general population after 16 weeks of treatment. A random 1-year follow-up assessment from the original RCT showed that most patients who had been matched had maintained their improvement.23

Continue to: Therefore, a multidimensional routine outcome...

Therefore, a multidimensional routine outcome monitoring tool can be used to identify a BHP’s relative strengths and weaknesses across multiple outcome domains. Within a system of care, a sample of BHPs will possess varying outcome-domain profiles. When a new patient is seeking a referral to a BHP, these profiles (or domain-specific outcome track records) can be used to support paired-on outcome data matching. Specifically, a new patient completes the multidimensional routine outcome monitoring tool at pretreatment, and the results reveal the outcome domains on which the patient is most clinically severe. This pattern of domain-specific severity then can be used to pair the new patient with a BHP who has demonstrated success in addressing the same outcome domain(s). This approach matches a new patient to a BHP with established expertise based on routine outcome monitoring.

Retrospective and prospective studies have found that most BHPs have stable performance in their strengths and weaknesses.11,21 One study found that assessing BHP performance with their most recent 30 patients can reliably predict future performance with their next 30 patients.24 This predictability in a practitioner’s outcomes suggests report cards that are updated frequently can be utilized to make case assignments within BH or referrals to a specific BHP from primary care.

Making a paired-on outcome data–matched referral

Making customized BH referrals requires access to information about a practitioner’s previous routine outcome monitoring data per clinical domain (eg, suicidality, violence, quality of life) from their most recent patients. Previous research suggests that follow-up data from a minimum of 15 patients is necessary to make a reliable evaluation of a practitioner’s strengths and weaknesses (ie, effectiveness “report card”) per clinical domain.24

Few, if any, physicians have access to this level of updated outcome data from their referral network. To facilitate widespread use of paired-on outcome data matching, a new Web system (MatchedTherapists.com) will allow the general public and PCPs to access these grades. As a public service option, this site currently allows for a self-assessment using the Treatment Outcome Package. Pending versions will generate paired-on outcome data grades, and users will receive a list of local therapists available for in-person appointments as well as therapists available for virtual appointments. The paired-on outcome data grades are delivered in school-based letter grades. An “A+,” for example, represents the best matching grade. Users also will be able to sort and filter results for other criteria such as telemedicine, insurance, age, gender, and appointment availability. Currently, there are more than 77,000 therapists listed on the site nationwide. A basic listing is free.

CASE SCENARIO

After Ms. W took the multidimensional routine outcome assessment online, she received a list of therapists rank-ordered by paired-on outcome data grade, with the “A+” matches listed first. Three of the best-matched referrals accepted her insurance and were willing to see her through telemedicine. Therapists with available in-person appointments had a “B” grade. After discussing the options with her physician, Ms. W opted for telehealth counseling with the therapist whose profile she liked best. The therapist and PCP tracked her progress through routine outcome monitoring reporting until all her symptoms became subclinical.

Continue to: The future of a "referral bridge"

The future of a “referral bridge”

In this article, we present a solution to a common issue faced by mental health care patients: failure to benefit meaningfully from mental health treatment. Matching patients to specific BHPs based on effectiveness data regarding the therapist’s strengths and skills can improve patient outcomes and reduce harm. In addition, patients appear to value this approach. A Robert Wood Johnson Foundation–funded study demonstrated that patients value seeing practitioners who have a track record of successfully treating previous patients with similar issues.25,26 In many cases, patients indicated they would prioritize this matching process over other factors such as practitioners with a higher number of years of experience or the same demographic characteristics as the patient.25,26

These findings may represent a new area in the science of health care. Over the past century, major advances in diagnosis and treatment—the 2 primary pillars of health care—have turned the art of medicine into a science. However, the art of making referrals has not advanced commensurately, as there has been little attention focused on the “referral bridge” between these 2 pillars. As the studies reviewed in this paper demonstrate, a referral bridge deserves exploration in all fields of medicine.

CORRESPONDENCE

David R. Kraus, PhD, 1 Speen Street, Framingham, MA 01701; dkraus@outcomereferrals.com

1. HHS. 2021 National Survey of Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) Releases. Accessed March 29, 2023. www.samhsa.gov/data/release/2021-national-survey-drug-use-and-health-nsduh-releases

2. Barkham M, Lambert, MJ. The efficacy and effectiveness of psychological therapies. In: Barkham M, Lutz W, Castonguay LG, eds. Bergin and Garfield’s Handbook of Psychotherapy and Behavior Change: 50th Anniversary Edition. 7th ed. John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2021:135-189.

3. Lewis CC, Boyd M, Puspitasari A, et al. Implementing measurement-based care in behavioral health: a review. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;76:324-335. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.3329

4. de Jong K, Conijn JM, Gallagher RAV, et al. Using progress feedback to improve outcomes and reduce drop-out, treatment duration, and deterioration: a multilevel meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2021;85:102002. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2021.102002

5. Carlier IVE, Meuldijk D, Van Vliet IM, et al. Routine outcome monitoring and feedback on physical or mental health status: evidence and theory. J Eval Clin Pract. 2012;18:104-110. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2010.01543.x

6. Muir HJ, Coyne AE, Morrison NR, et al. Ethical implications of routine outcomes monitoring for patients, psychotherapists, and mental health care systems. Psychotherapy (Chic). 2019;56:459-469. doi: 10.1037/pst0000246

7. Hannan C, Lambert MJ, Harmon C, et al. A lab test and algorithms for identifying clients at risk for treatment failure. J Clin Psychol. 2005;61:155-163. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20108

8. Castonguay LG, Boswell JF, Constantino MJ, et al. Training implications of harmful effects of psychological treatments. Am Psychol. 2010;65:34-49. doi: 10.1037/a0017330

9. Kraus DR, Castonguay LG, Boswell JF, et al. Therapist effectiveness: implications for accountability and patient care. Psychother Res. 2011;21:267-276. doi: 10.1080/10503307.2011.563249

10. Lilienfeld SO. Psychological treatments that cause harm. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2007;2:53-70. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6916.2007.00029.x

11. Boswell JF, Constantino MJ, Kraus DR, et al. The expanding relevance of routinely collected outcome data for mental health care decision making. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2016;43:482-491. doi: 10.1007/s10488-015-0649-6

12. Lyon AR, Lewis CC, Boyd MR, et al. Capabilities and characteristics of digital measurement feedback systems: results from a comprehensive review. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2016;43:441-466. doi: 10.1007/s10488-016-0719-4

13. Teymoori A, Gorbunova A, Haghish FE, et al. Factorial structure and validity of depression (PHQ-9) and anxiety (GAD-7) scales after traumatic brain injury. J Clin Med. 2020;9:873. doi: 10.3390/jcm9030873

14. Kraus DR, Seligman DA, Jordan JR. Validation of a behavioral health treatment outcome and assessment tool designed for naturalistic settings: the Treatment Outcome Package. J Clin Psychol. 2005;61:285‐314. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20084

15. Boothroyd L, Dagnan D, Muncer S. Psychometric analysis of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale and the Patient Health Questionnaire using Mokken scaling and confirmatory factor analysis. Health Prim Care. 2018;2:1-4. doi: 10.15761/HPC.1000145

16. Locke BD, Buzolitz JS, Lei PW, et al. Development of the Counseling Center Assessment of Psychological Symptoms-62 (CCAPS-62). J Couns Psychol. 2011;58:97-109. doi: 10.1037/a0021282

17. Kraus DR, Boswell JF, Wright AGC, et al. Factor structure of the treatment outcome package for children. J Clin Psychol. 2010;66:627-640. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20675

18. McAleavey AA, Nordberg SS, Kraus D, et al. Errors in treatment outcome monitoring: implications for real-world psychotherapy. Can Psychol. 2010;53:105-114. doi: 10.1037/a0027833

19. Baxter EE, Alexander PC, Kraus DR, et al. Concurrent validation of the Treatment Outcome Package (TOP) for children and adolescents. J Child Fam Stud. 2016;25:2415-2422. doi: 10.1007/s10826-016-0419-4

20. Gual-Montolio P, Martínez-Borba V, Bretón-López JM, et al. How are information and communication technologies supporting routine outcome monitoring and measurement-based care in psychotherapy? A systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:3170. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17093170

21. Kraus DR, Bentley JH, Alexander PC, et al. Predicting therapist effectiveness from their own practice-based evidence. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2016;84:473‐483. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000083

22. Constantino MJ, Boswell JF, Coyne AE, et al. Effect of matching therapists to patients vs assignment as usual on adult psychotherapy outcomes. A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2021;78:960-969. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2021.1221

23. Constantino MJ, Boswell JF, Kraus DR, et al. Matching patients with therapists to improve mental health care. Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI). 2021. Accessed March 1, 2023. www.pcori.org/research-results/2015/matching-patients-therapists-improve-mental-health-care

24. Institute of Medicine. Committee on Crossing the Quality Chasm: Adaptation to Mental Health and Addictive Disorders. Improving the Quality of Health Care for Mental and Substance-Use Conditions. National Academies Press; 2006. Accessed February 21, 2023. https://nap.nationalacademies.org/read/11470/chapter/1

25. Boswell JF, Constantino MJ, Oswald JM, et al. A multimethod study of mental health care patients’ attitudes toward clinician-level performance information. Psychiatr Serv. 2021;72:452-456. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.202000366

26. Boswell JF, Constantino MJ, Oswald JM, et al. Mental health care consumers’ relative valuing of clinician performance information. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2018;86:301‐308. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000264

Approximately 1 in 4 people ages 18 years and older and 1 in 3 people ages 18 to 25 years had a mental illness in the past year, according to the 2021 National Survey of Drug Use and Health.1 The survey also found that adults ages 18 to 25 years had the highest rate of serious mental illness but the lowest treatment rate compared to other adult age groups.1 Unfortunately, more than 60% of patients receiving mental health treatment fail to benefit to a clinically meaningful degree.2

However, there is growing evidence that referring patients to behavioral health practitioners (BHPs) with outcome-measured skills that meet the patient’s specific needs can have a dramatic and positive impact. There are 2 main steps to pairing patients with an appropriate BHP: (1) use of measurement-based care data that can be analyzed at the patient and therapist level, and (2) data-driven referrals that pair patients with BHPs based on such routine outcome monitoring data (paired-on outcome data).

Psychotherapy’s slow road toward measurement-based care

Routine outcome monitoring is the systematic measurement of symptoms and functioning during treatment. It serves multiple functions, including program evaluation and benchmarking of patient improvement rates. Moreover, routine outcome monitoring–derived feedback (based on repeated patient outcome measurements) can inform personalized and responsive care decisions throughout treatment.

For all intents and purposes,

- routinely administered symptom/functioning measure, ideally before each clinical encounter,

- practitioner review of these patient-level data,

- patient review of these data with their practitioner, and

- collaborative reevaluation of the person-specific treatment plan informed by these data.

CASE SCENARIO

Violeta W is a 33-year-old woman who presented to her family physician for her annual wellness exam. Prior to the exam, the medical assistant administered a Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) to screen for depressive symptoms. Ms. W’s score was 20 out of 27, suggestive of depression. To further assess the severity of depressive symptoms and their effect on daily function, the physician reviewed responses to the questionnaire with her and discussed treatment options. Ms. W was most interested in trying a low-dose selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI).

At her follow-up visit 4 weeks later, the medical assistant re-administered the PHQ-9. The physician then reviewed Ms. W’s responses with her and, based on Ms. W’s subjective report and objective symptoms (still a score of 20 out of 27 on the PHQ-9), increased her SSRI dose. At each subsequent visit, Ms. W completed a PHQ-9 and reviewed responses and depressive symptoms with her physician.

The value of measurement-based care in mental health care

A narrative review by Lewis et al3 of 21 randomized controlled clinical trials (RCTs) across a range of age groups (eg, adolescents, young adults, adults), disorders (eg, anxiety, mood), and settings (eg, outpatient, inpatient) found that in at least 9 review articles, measurement-based care was associated with significantly improved outcomes vs usual care (ie, treatment without routine outcome monitoring plus feedback). The average increase in treatment effect size was about 30% when treatment was accompanied by measurement-based care.3

Continue to: Moreover, a recent within-patient meta-analysis...

Moreover, a recent within-patient meta-analysis by de Jong et al4 shows that measurement-based care yields a small but significant increase in therapeutic outcomes (d = .15). Use of measurement-based care also is associated with improved communication between the patient and therapist.5 In pharmacotherapy practice, measurement-based care has been shown to predict rapid dose increases and changes in medication, when necessary; faster recovery rates; higher response rates to treatment3; and fewer dropouts.4

Perhaps one of the best-studied benefits of measurement-based mental health care is the ability to predict deterioration in care (ie, patients who are off-track in a way that practitioners often miss without the help of routine outcome monitoring data).6,7 Studies show that without a data-informed approach to care, some forms of psychotherapy or therapy with BHPs who are not sufficiently skilled in treating a given diagnosis increase symptoms or create significant harmful and iatrogenic effects.8-10 Conversely, the meta-analysis by de Jong et al4 found a lower percentage of deterioration in patients receiving measurement-based care. The difference in deterioration was significant: An average of 5.4% of patients in control conditions deteriorated compared to an average of 4.6% in feedback (measurement-based care) groups. There were even larger effect sizes when therapists received training in the feedback system.4

Routine outcome monitoring without a dialogue between patient and practitioner about the assessments (eg, ignoring complete measurement-based care requirements) may be inadequate. A recent review by Muir et al6 found no differences in patient outcomes when data were used solely for aggregate quality improvement activities, suggesting the need for practitioners to review results of routine outcome monitoring assessments with patients and use data to alter care when necessary.

Measurement-based care is believed to deliver benefits and reduce harm by enhancing and encouraging active patient involvement, improving patient understanding of symptoms, promoting better communication, and facilitating better care coordination.3 The benefits of measurement-based care can be enhanced with a comprehensive core routine outcome monitoring tool and the level of monitoring-generated information delivered for multiple stakeholders (eg, patient, therapist, clinic).11

A look at multidimensional assessment

The features of routine outcome monitoring tools vary significantly.12 Some measures assess single-symptom or problem domains (eg, PHQ-9 for depression or Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 [GAD-7] scale for anxiety) or multiple dimensions (multidimensional routine outcome monitoring).Multidimensional routine outcome monitoring may have benefits over single-domain measures. Single-domain measures and the subscales or factors of more comprehensive multidimensional routine outcome monitoring assessments should possess adequate specificity and sensitivity.

Continue to: Some recent research findings...

Some recent research findings question the construct validity of brief single-domain measures of common presenting problems, such as depression and anxiety. For example, results from a factor analysis of the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 scale in patients with traumatic brain injury suggest these tools measure 1 psychological construct that includes depression and the cognitive components of anxiety (eg, worry)13—a finding consistent with those of other tools.14 Similarly, a larger study of 7763 BH patients found that a single factor accounted for most of the variance of the 2 combined measures, with no set of factors meeting the exacting standards used to develop multidimensional routine outcome monitoring.15 These findings suggest that the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 largely overlap and are not measuring different aspects of health as most practitioners believe (eg, depression and anxiety).

In commonly used assessments, multiple-factor analytic studies with high standards have supported the construct validity of domain-specific subscales, indicating that the various questions tap into different constructs of psychological health.14,16,17

Beyond multiple domain–specific indicators, multidimensional routine outcome measurements provide a global total score that minimizes Type I (false-positive conclusion) and Type II (false-negative conclusion) errors in tracking patient improvement or deterioration.18 As one would expect, multidimensional routine outcome monitoring generally includes more items than single-domain measures; however, this comes with a trade-off. If there are specificity and sensitivity concerns with an ultra-brief single-domain measure, an alternative to a core multidimensional routine outcome measurement is to aggregate a series of single-domain measures into a battery of patient self-reports. However, this approach may take longer for patients to complete since they would have to shift among the varying response sets and wording across the unique single-domain measures.

In addition, the standardization/normalization of multidimensional routine outcome monitoring likely makes interpretation easier than referring to norms and clinical severity cutoffs for many distinct measures. Furthermore, increased specificity enhances predictive power and allows BHPs to screen and track other conditions besides depression and anxiety. (It is worth noting that there are no known studies that have looked at the difference in time to administer or ease of interpretation of multidimensional routine outcome monitoring tools vs multiple single-domain measures.)

Two multidimensional routine outcome monitoring tools that cover a comprehensive series of discrete symptom and functional domains are the Treatment Outcome Package12 and Counseling Center Assessment of Psychological Symptoms.16 These tools, which include subscales beyond general depression and anxiety (eg, sleep, substance misuse, social conflict), take 7 to 10 minutes to complete and provide outcome results across 12 symptom and 8 functional dimensions. As an example, the Treatment Outcome Package has good psychometric qualities (eg, reliability, construct and concurrent validity) for adults,12 children,14,19 and adolescents,19 and can be administered through a secure online data collection portal. The Counseling Center Assessment of Psychological Symptoms has demonstrated high construct validity and good convergent validity.16 These assessments can be administered in paper or digital (eg, electronic medical record portal, smartphone) format.20

Continue to: CASE SCENARIO

CASE SCENARIO

Ms. W’s physician asked her to go online using her phone and answer the questions in the Treatment Outcome Package. Her results, which she viewed with her physician, were displayed in graph form (FIGURE). Her scores were represented in Z scores normalized to the general population, with “0” representing the general, nontreatment-seeking population average and positive scores representing the number of standard deviations (SDs) more severe than the general population average.

Although this assessment scored Ms. W’s clinically elevated depression as mild, it revealed abnormalities in 3 other domains. Sexual functioning issues represented the most abnormal domain at greater than 3 SDs (more severe than the general population), followed by poor life quality and school/work functioning.

After reviewing Ms. W’s report, her physician decided that pharmacologic management alone (for depression) was not the most appropriate treatment course. Therefore, her physician recommended psychotherapy in addition to the SSRI she was taking. Ms. W agreed to a customized referral for psychotherapy.

Data-driven referrals

When psychotherapy is chosen as a treatment, the individual BHP is an active component of that treatment. Consequently, it is essential to customize referrals to match a patient’s most elevated mental health concerns with a therapist who will most effectively treat those domains. It is rare for a BHP to be skilled in treating every mental health domain.9 Multiple studies have shown that BHPs have identifiable treatment skills in specific domains, which physicians should consider when making referrals.9,21,22 These studies demonstrate the utility of aggregating patient-level routine outcome monitoring data to better understand therapist-level (and ultimately clinic- and system-level) outcomes.

Additionally, recent research has tested this idea prospectively. An RCT funded by the Patient-Centered Outcome Research Institute and published in JAMA Psychiatry showed a significant and positive effect on patient outcomes (ie, reductions in general impairment, impairment involving a patient’s most elevated domain, and global distress) using paired-on outcome data matching vs as-usual matching protocols (eg, therapist self-defined areas of specialty).22 In the RCT, the most effective matching protocol was a combination of eliminating harm and matching the patient on their 3 most problematic domains (the highest match level). These patients ended care as healthy as the general population after 16 weeks of treatment. A random 1-year follow-up assessment from the original RCT showed that most patients who had been matched had maintained their improvement.23

Continue to: Therefore, a multidimensional routine outcome...

Therefore, a multidimensional routine outcome monitoring tool can be used to identify a BHP’s relative strengths and weaknesses across multiple outcome domains. Within a system of care, a sample of BHPs will possess varying outcome-domain profiles. When a new patient is seeking a referral to a BHP, these profiles (or domain-specific outcome track records) can be used to support paired-on outcome data matching. Specifically, a new patient completes the multidimensional routine outcome monitoring tool at pretreatment, and the results reveal the outcome domains on which the patient is most clinically severe. This pattern of domain-specific severity then can be used to pair the new patient with a BHP who has demonstrated success in addressing the same outcome domain(s). This approach matches a new patient to a BHP with established expertise based on routine outcome monitoring.

Retrospective and prospective studies have found that most BHPs have stable performance in their strengths and weaknesses.11,21 One study found that assessing BHP performance with their most recent 30 patients can reliably predict future performance with their next 30 patients.24 This predictability in a practitioner’s outcomes suggests report cards that are updated frequently can be utilized to make case assignments within BH or referrals to a specific BHP from primary care.

Making a paired-on outcome data–matched referral

Making customized BH referrals requires access to information about a practitioner’s previous routine outcome monitoring data per clinical domain (eg, suicidality, violence, quality of life) from their most recent patients. Previous research suggests that follow-up data from a minimum of 15 patients is necessary to make a reliable evaluation of a practitioner’s strengths and weaknesses (ie, effectiveness “report card”) per clinical domain.24

Few, if any, physicians have access to this level of updated outcome data from their referral network. To facilitate widespread use of paired-on outcome data matching, a new Web system (MatchedTherapists.com) will allow the general public and PCPs to access these grades. As a public service option, this site currently allows for a self-assessment using the Treatment Outcome Package. Pending versions will generate paired-on outcome data grades, and users will receive a list of local therapists available for in-person appointments as well as therapists available for virtual appointments. The paired-on outcome data grades are delivered in school-based letter grades. An “A+,” for example, represents the best matching grade. Users also will be able to sort and filter results for other criteria such as telemedicine, insurance, age, gender, and appointment availability. Currently, there are more than 77,000 therapists listed on the site nationwide. A basic listing is free.

CASE SCENARIO

After Ms. W took the multidimensional routine outcome assessment online, she received a list of therapists rank-ordered by paired-on outcome data grade, with the “A+” matches listed first. Three of the best-matched referrals accepted her insurance and were willing to see her through telemedicine. Therapists with available in-person appointments had a “B” grade. After discussing the options with her physician, Ms. W opted for telehealth counseling with the therapist whose profile she liked best. The therapist and PCP tracked her progress through routine outcome monitoring reporting until all her symptoms became subclinical.

Continue to: The future of a "referral bridge"

The future of a “referral bridge”

In this article, we present a solution to a common issue faced by mental health care patients: failure to benefit meaningfully from mental health treatment. Matching patients to specific BHPs based on effectiveness data regarding the therapist’s strengths and skills can improve patient outcomes and reduce harm. In addition, patients appear to value this approach. A Robert Wood Johnson Foundation–funded study demonstrated that patients value seeing practitioners who have a track record of successfully treating previous patients with similar issues.25,26 In many cases, patients indicated they would prioritize this matching process over other factors such as practitioners with a higher number of years of experience or the same demographic characteristics as the patient.25,26

These findings may represent a new area in the science of health care. Over the past century, major advances in diagnosis and treatment—the 2 primary pillars of health care—have turned the art of medicine into a science. However, the art of making referrals has not advanced commensurately, as there has been little attention focused on the “referral bridge” between these 2 pillars. As the studies reviewed in this paper demonstrate, a referral bridge deserves exploration in all fields of medicine.

CORRESPONDENCE

David R. Kraus, PhD, 1 Speen Street, Framingham, MA 01701; dkraus@outcomereferrals.com

Approximately 1 in 4 people ages 18 years and older and 1 in 3 people ages 18 to 25 years had a mental illness in the past year, according to the 2021 National Survey of Drug Use and Health.1 The survey also found that adults ages 18 to 25 years had the highest rate of serious mental illness but the lowest treatment rate compared to other adult age groups.1 Unfortunately, more than 60% of patients receiving mental health treatment fail to benefit to a clinically meaningful degree.2

However, there is growing evidence that referring patients to behavioral health practitioners (BHPs) with outcome-measured skills that meet the patient’s specific needs can have a dramatic and positive impact. There are 2 main steps to pairing patients with an appropriate BHP: (1) use of measurement-based care data that can be analyzed at the patient and therapist level, and (2) data-driven referrals that pair patients with BHPs based on such routine outcome monitoring data (paired-on outcome data).

Psychotherapy’s slow road toward measurement-based care

Routine outcome monitoring is the systematic measurement of symptoms and functioning during treatment. It serves multiple functions, including program evaluation and benchmarking of patient improvement rates. Moreover, routine outcome monitoring–derived feedback (based on repeated patient outcome measurements) can inform personalized and responsive care decisions throughout treatment.

For all intents and purposes,

- routinely administered symptom/functioning measure, ideally before each clinical encounter,

- practitioner review of these patient-level data,

- patient review of these data with their practitioner, and

- collaborative reevaluation of the person-specific treatment plan informed by these data.

CASE SCENARIO

Violeta W is a 33-year-old woman who presented to her family physician for her annual wellness exam. Prior to the exam, the medical assistant administered a Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) to screen for depressive symptoms. Ms. W’s score was 20 out of 27, suggestive of depression. To further assess the severity of depressive symptoms and their effect on daily function, the physician reviewed responses to the questionnaire with her and discussed treatment options. Ms. W was most interested in trying a low-dose selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI).

At her follow-up visit 4 weeks later, the medical assistant re-administered the PHQ-9. The physician then reviewed Ms. W’s responses with her and, based on Ms. W’s subjective report and objective symptoms (still a score of 20 out of 27 on the PHQ-9), increased her SSRI dose. At each subsequent visit, Ms. W completed a PHQ-9 and reviewed responses and depressive symptoms with her physician.

The value of measurement-based care in mental health care

A narrative review by Lewis et al3 of 21 randomized controlled clinical trials (RCTs) across a range of age groups (eg, adolescents, young adults, adults), disorders (eg, anxiety, mood), and settings (eg, outpatient, inpatient) found that in at least 9 review articles, measurement-based care was associated with significantly improved outcomes vs usual care (ie, treatment without routine outcome monitoring plus feedback). The average increase in treatment effect size was about 30% when treatment was accompanied by measurement-based care.3

Continue to: Moreover, a recent within-patient meta-analysis...

Moreover, a recent within-patient meta-analysis by de Jong et al4 shows that measurement-based care yields a small but significant increase in therapeutic outcomes (d = .15). Use of measurement-based care also is associated with improved communication between the patient and therapist.5 In pharmacotherapy practice, measurement-based care has been shown to predict rapid dose increases and changes in medication, when necessary; faster recovery rates; higher response rates to treatment3; and fewer dropouts.4

Perhaps one of the best-studied benefits of measurement-based mental health care is the ability to predict deterioration in care (ie, patients who are off-track in a way that practitioners often miss without the help of routine outcome monitoring data).6,7 Studies show that without a data-informed approach to care, some forms of psychotherapy or therapy with BHPs who are not sufficiently skilled in treating a given diagnosis increase symptoms or create significant harmful and iatrogenic effects.8-10 Conversely, the meta-analysis by de Jong et al4 found a lower percentage of deterioration in patients receiving measurement-based care. The difference in deterioration was significant: An average of 5.4% of patients in control conditions deteriorated compared to an average of 4.6% in feedback (measurement-based care) groups. There were even larger effect sizes when therapists received training in the feedback system.4

Routine outcome monitoring without a dialogue between patient and practitioner about the assessments (eg, ignoring complete measurement-based care requirements) may be inadequate. A recent review by Muir et al6 found no differences in patient outcomes when data were used solely for aggregate quality improvement activities, suggesting the need for practitioners to review results of routine outcome monitoring assessments with patients and use data to alter care when necessary.

Measurement-based care is believed to deliver benefits and reduce harm by enhancing and encouraging active patient involvement, improving patient understanding of symptoms, promoting better communication, and facilitating better care coordination.3 The benefits of measurement-based care can be enhanced with a comprehensive core routine outcome monitoring tool and the level of monitoring-generated information delivered for multiple stakeholders (eg, patient, therapist, clinic).11

A look at multidimensional assessment

The features of routine outcome monitoring tools vary significantly.12 Some measures assess single-symptom or problem domains (eg, PHQ-9 for depression or Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 [GAD-7] scale for anxiety) or multiple dimensions (multidimensional routine outcome monitoring).Multidimensional routine outcome monitoring may have benefits over single-domain measures. Single-domain measures and the subscales or factors of more comprehensive multidimensional routine outcome monitoring assessments should possess adequate specificity and sensitivity.

Continue to: Some recent research findings...

Some recent research findings question the construct validity of brief single-domain measures of common presenting problems, such as depression and anxiety. For example, results from a factor analysis of the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 scale in patients with traumatic brain injury suggest these tools measure 1 psychological construct that includes depression and the cognitive components of anxiety (eg, worry)13—a finding consistent with those of other tools.14 Similarly, a larger study of 7763 BH patients found that a single factor accounted for most of the variance of the 2 combined measures, with no set of factors meeting the exacting standards used to develop multidimensional routine outcome monitoring.15 These findings suggest that the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 largely overlap and are not measuring different aspects of health as most practitioners believe (eg, depression and anxiety).

In commonly used assessments, multiple-factor analytic studies with high standards have supported the construct validity of domain-specific subscales, indicating that the various questions tap into different constructs of psychological health.14,16,17

Beyond multiple domain–specific indicators, multidimensional routine outcome measurements provide a global total score that minimizes Type I (false-positive conclusion) and Type II (false-negative conclusion) errors in tracking patient improvement or deterioration.18 As one would expect, multidimensional routine outcome monitoring generally includes more items than single-domain measures; however, this comes with a trade-off. If there are specificity and sensitivity concerns with an ultra-brief single-domain measure, an alternative to a core multidimensional routine outcome measurement is to aggregate a series of single-domain measures into a battery of patient self-reports. However, this approach may take longer for patients to complete since they would have to shift among the varying response sets and wording across the unique single-domain measures.

In addition, the standardization/normalization of multidimensional routine outcome monitoring likely makes interpretation easier than referring to norms and clinical severity cutoffs for many distinct measures. Furthermore, increased specificity enhances predictive power and allows BHPs to screen and track other conditions besides depression and anxiety. (It is worth noting that there are no known studies that have looked at the difference in time to administer or ease of interpretation of multidimensional routine outcome monitoring tools vs multiple single-domain measures.)

Two multidimensional routine outcome monitoring tools that cover a comprehensive series of discrete symptom and functional domains are the Treatment Outcome Package12 and Counseling Center Assessment of Psychological Symptoms.16 These tools, which include subscales beyond general depression and anxiety (eg, sleep, substance misuse, social conflict), take 7 to 10 minutes to complete and provide outcome results across 12 symptom and 8 functional dimensions. As an example, the Treatment Outcome Package has good psychometric qualities (eg, reliability, construct and concurrent validity) for adults,12 children,14,19 and adolescents,19 and can be administered through a secure online data collection portal. The Counseling Center Assessment of Psychological Symptoms has demonstrated high construct validity and good convergent validity.16 These assessments can be administered in paper or digital (eg, electronic medical record portal, smartphone) format.20

Continue to: CASE SCENARIO

CASE SCENARIO

Ms. W’s physician asked her to go online using her phone and answer the questions in the Treatment Outcome Package. Her results, which she viewed with her physician, were displayed in graph form (FIGURE). Her scores were represented in Z scores normalized to the general population, with “0” representing the general, nontreatment-seeking population average and positive scores representing the number of standard deviations (SDs) more severe than the general population average.

Although this assessment scored Ms. W’s clinically elevated depression as mild, it revealed abnormalities in 3 other domains. Sexual functioning issues represented the most abnormal domain at greater than 3 SDs (more severe than the general population), followed by poor life quality and school/work functioning.

After reviewing Ms. W’s report, her physician decided that pharmacologic management alone (for depression) was not the most appropriate treatment course. Therefore, her physician recommended psychotherapy in addition to the SSRI she was taking. Ms. W agreed to a customized referral for psychotherapy.

Data-driven referrals

When psychotherapy is chosen as a treatment, the individual BHP is an active component of that treatment. Consequently, it is essential to customize referrals to match a patient’s most elevated mental health concerns with a therapist who will most effectively treat those domains. It is rare for a BHP to be skilled in treating every mental health domain.9 Multiple studies have shown that BHPs have identifiable treatment skills in specific domains, which physicians should consider when making referrals.9,21,22 These studies demonstrate the utility of aggregating patient-level routine outcome monitoring data to better understand therapist-level (and ultimately clinic- and system-level) outcomes.

Additionally, recent research has tested this idea prospectively. An RCT funded by the Patient-Centered Outcome Research Institute and published in JAMA Psychiatry showed a significant and positive effect on patient outcomes (ie, reductions in general impairment, impairment involving a patient’s most elevated domain, and global distress) using paired-on outcome data matching vs as-usual matching protocols (eg, therapist self-defined areas of specialty).22 In the RCT, the most effective matching protocol was a combination of eliminating harm and matching the patient on their 3 most problematic domains (the highest match level). These patients ended care as healthy as the general population after 16 weeks of treatment. A random 1-year follow-up assessment from the original RCT showed that most patients who had been matched had maintained their improvement.23

Continue to: Therefore, a multidimensional routine outcome...

Therefore, a multidimensional routine outcome monitoring tool can be used to identify a BHP’s relative strengths and weaknesses across multiple outcome domains. Within a system of care, a sample of BHPs will possess varying outcome-domain profiles. When a new patient is seeking a referral to a BHP, these profiles (or domain-specific outcome track records) can be used to support paired-on outcome data matching. Specifically, a new patient completes the multidimensional routine outcome monitoring tool at pretreatment, and the results reveal the outcome domains on which the patient is most clinically severe. This pattern of domain-specific severity then can be used to pair the new patient with a BHP who has demonstrated success in addressing the same outcome domain(s). This approach matches a new patient to a BHP with established expertise based on routine outcome monitoring.

Retrospective and prospective studies have found that most BHPs have stable performance in their strengths and weaknesses.11,21 One study found that assessing BHP performance with their most recent 30 patients can reliably predict future performance with their next 30 patients.24 This predictability in a practitioner’s outcomes suggests report cards that are updated frequently can be utilized to make case assignments within BH or referrals to a specific BHP from primary care.

Making a paired-on outcome data–matched referral

Making customized BH referrals requires access to information about a practitioner’s previous routine outcome monitoring data per clinical domain (eg, suicidality, violence, quality of life) from their most recent patients. Previous research suggests that follow-up data from a minimum of 15 patients is necessary to make a reliable evaluation of a practitioner’s strengths and weaknesses (ie, effectiveness “report card”) per clinical domain.24

Few, if any, physicians have access to this level of updated outcome data from their referral network. To facilitate widespread use of paired-on outcome data matching, a new Web system (MatchedTherapists.com) will allow the general public and PCPs to access these grades. As a public service option, this site currently allows for a self-assessment using the Treatment Outcome Package. Pending versions will generate paired-on outcome data grades, and users will receive a list of local therapists available for in-person appointments as well as therapists available for virtual appointments. The paired-on outcome data grades are delivered in school-based letter grades. An “A+,” for example, represents the best matching grade. Users also will be able to sort and filter results for other criteria such as telemedicine, insurance, age, gender, and appointment availability. Currently, there are more than 77,000 therapists listed on the site nationwide. A basic listing is free.

CASE SCENARIO

After Ms. W took the multidimensional routine outcome assessment online, she received a list of therapists rank-ordered by paired-on outcome data grade, with the “A+” matches listed first. Three of the best-matched referrals accepted her insurance and were willing to see her through telemedicine. Therapists with available in-person appointments had a “B” grade. After discussing the options with her physician, Ms. W opted for telehealth counseling with the therapist whose profile she liked best. The therapist and PCP tracked her progress through routine outcome monitoring reporting until all her symptoms became subclinical.

Continue to: The future of a "referral bridge"

The future of a “referral bridge”

In this article, we present a solution to a common issue faced by mental health care patients: failure to benefit meaningfully from mental health treatment. Matching patients to specific BHPs based on effectiveness data regarding the therapist’s strengths and skills can improve patient outcomes and reduce harm. In addition, patients appear to value this approach. A Robert Wood Johnson Foundation–funded study demonstrated that patients value seeing practitioners who have a track record of successfully treating previous patients with similar issues.25,26 In many cases, patients indicated they would prioritize this matching process over other factors such as practitioners with a higher number of years of experience or the same demographic characteristics as the patient.25,26

These findings may represent a new area in the science of health care. Over the past century, major advances in diagnosis and treatment—the 2 primary pillars of health care—have turned the art of medicine into a science. However, the art of making referrals has not advanced commensurately, as there has been little attention focused on the “referral bridge” between these 2 pillars. As the studies reviewed in this paper demonstrate, a referral bridge deserves exploration in all fields of medicine.

CORRESPONDENCE

David R. Kraus, PhD, 1 Speen Street, Framingham, MA 01701; dkraus@outcomereferrals.com

1. HHS. 2021 National Survey of Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) Releases. Accessed March 29, 2023. www.samhsa.gov/data/release/2021-national-survey-drug-use-and-health-nsduh-releases

2. Barkham M, Lambert, MJ. The efficacy and effectiveness of psychological therapies. In: Barkham M, Lutz W, Castonguay LG, eds. Bergin and Garfield’s Handbook of Psychotherapy and Behavior Change: 50th Anniversary Edition. 7th ed. John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2021:135-189.

3. Lewis CC, Boyd M, Puspitasari A, et al. Implementing measurement-based care in behavioral health: a review. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;76:324-335. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.3329

4. de Jong K, Conijn JM, Gallagher RAV, et al. Using progress feedback to improve outcomes and reduce drop-out, treatment duration, and deterioration: a multilevel meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2021;85:102002. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2021.102002

5. Carlier IVE, Meuldijk D, Van Vliet IM, et al. Routine outcome monitoring and feedback on physical or mental health status: evidence and theory. J Eval Clin Pract. 2012;18:104-110. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2010.01543.x

6. Muir HJ, Coyne AE, Morrison NR, et al. Ethical implications of routine outcomes monitoring for patients, psychotherapists, and mental health care systems. Psychotherapy (Chic). 2019;56:459-469. doi: 10.1037/pst0000246

7. Hannan C, Lambert MJ, Harmon C, et al. A lab test and algorithms for identifying clients at risk for treatment failure. J Clin Psychol. 2005;61:155-163. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20108

8. Castonguay LG, Boswell JF, Constantino MJ, et al. Training implications of harmful effects of psychological treatments. Am Psychol. 2010;65:34-49. doi: 10.1037/a0017330

9. Kraus DR, Castonguay LG, Boswell JF, et al. Therapist effectiveness: implications for accountability and patient care. Psychother Res. 2011;21:267-276. doi: 10.1080/10503307.2011.563249

10. Lilienfeld SO. Psychological treatments that cause harm. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2007;2:53-70. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6916.2007.00029.x

11. Boswell JF, Constantino MJ, Kraus DR, et al. The expanding relevance of routinely collected outcome data for mental health care decision making. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2016;43:482-491. doi: 10.1007/s10488-015-0649-6

12. Lyon AR, Lewis CC, Boyd MR, et al. Capabilities and characteristics of digital measurement feedback systems: results from a comprehensive review. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2016;43:441-466. doi: 10.1007/s10488-016-0719-4

13. Teymoori A, Gorbunova A, Haghish FE, et al. Factorial structure and validity of depression (PHQ-9) and anxiety (GAD-7) scales after traumatic brain injury. J Clin Med. 2020;9:873. doi: 10.3390/jcm9030873

14. Kraus DR, Seligman DA, Jordan JR. Validation of a behavioral health treatment outcome and assessment tool designed for naturalistic settings: the Treatment Outcome Package. J Clin Psychol. 2005;61:285‐314. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20084

15. Boothroyd L, Dagnan D, Muncer S. Psychometric analysis of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale and the Patient Health Questionnaire using Mokken scaling and confirmatory factor analysis. Health Prim Care. 2018;2:1-4. doi: 10.15761/HPC.1000145

16. Locke BD, Buzolitz JS, Lei PW, et al. Development of the Counseling Center Assessment of Psychological Symptoms-62 (CCAPS-62). J Couns Psychol. 2011;58:97-109. doi: 10.1037/a0021282

17. Kraus DR, Boswell JF, Wright AGC, et al. Factor structure of the treatment outcome package for children. J Clin Psychol. 2010;66:627-640. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20675

18. McAleavey AA, Nordberg SS, Kraus D, et al. Errors in treatment outcome monitoring: implications for real-world psychotherapy. Can Psychol. 2010;53:105-114. doi: 10.1037/a0027833

19. Baxter EE, Alexander PC, Kraus DR, et al. Concurrent validation of the Treatment Outcome Package (TOP) for children and adolescents. J Child Fam Stud. 2016;25:2415-2422. doi: 10.1007/s10826-016-0419-4

20. Gual-Montolio P, Martínez-Borba V, Bretón-López JM, et al. How are information and communication technologies supporting routine outcome monitoring and measurement-based care in psychotherapy? A systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:3170. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17093170

21. Kraus DR, Bentley JH, Alexander PC, et al. Predicting therapist effectiveness from their own practice-based evidence. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2016;84:473‐483. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000083

22. Constantino MJ, Boswell JF, Coyne AE, et al. Effect of matching therapists to patients vs assignment as usual on adult psychotherapy outcomes. A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2021;78:960-969. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2021.1221

23. Constantino MJ, Boswell JF, Kraus DR, et al. Matching patients with therapists to improve mental health care. Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI). 2021. Accessed March 1, 2023. www.pcori.org/research-results/2015/matching-patients-therapists-improve-mental-health-care

24. Institute of Medicine. Committee on Crossing the Quality Chasm: Adaptation to Mental Health and Addictive Disorders. Improving the Quality of Health Care for Mental and Substance-Use Conditions. National Academies Press; 2006. Accessed February 21, 2023. https://nap.nationalacademies.org/read/11470/chapter/1

25. Boswell JF, Constantino MJ, Oswald JM, et al. A multimethod study of mental health care patients’ attitudes toward clinician-level performance information. Psychiatr Serv. 2021;72:452-456. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.202000366

26. Boswell JF, Constantino MJ, Oswald JM, et al. Mental health care consumers’ relative valuing of clinician performance information. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2018;86:301‐308. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000264

1. HHS. 2021 National Survey of Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) Releases. Accessed March 29, 2023. www.samhsa.gov/data/release/2021-national-survey-drug-use-and-health-nsduh-releases

2. Barkham M, Lambert, MJ. The efficacy and effectiveness of psychological therapies. In: Barkham M, Lutz W, Castonguay LG, eds. Bergin and Garfield’s Handbook of Psychotherapy and Behavior Change: 50th Anniversary Edition. 7th ed. John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2021:135-189.

3. Lewis CC, Boyd M, Puspitasari A, et al. Implementing measurement-based care in behavioral health: a review. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;76:324-335. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.3329

4. de Jong K, Conijn JM, Gallagher RAV, et al. Using progress feedback to improve outcomes and reduce drop-out, treatment duration, and deterioration: a multilevel meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2021;85:102002. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2021.102002

5. Carlier IVE, Meuldijk D, Van Vliet IM, et al. Routine outcome monitoring and feedback on physical or mental health status: evidence and theory. J Eval Clin Pract. 2012;18:104-110. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2010.01543.x

6. Muir HJ, Coyne AE, Morrison NR, et al. Ethical implications of routine outcomes monitoring for patients, psychotherapists, and mental health care systems. Psychotherapy (Chic). 2019;56:459-469. doi: 10.1037/pst0000246

7. Hannan C, Lambert MJ, Harmon C, et al. A lab test and algorithms for identifying clients at risk for treatment failure. J Clin Psychol. 2005;61:155-163. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20108

8. Castonguay LG, Boswell JF, Constantino MJ, et al. Training implications of harmful effects of psychological treatments. Am Psychol. 2010;65:34-49. doi: 10.1037/a0017330

9. Kraus DR, Castonguay LG, Boswell JF, et al. Therapist effectiveness: implications for accountability and patient care. Psychother Res. 2011;21:267-276. doi: 10.1080/10503307.2011.563249

10. Lilienfeld SO. Psychological treatments that cause harm. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2007;2:53-70. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6916.2007.00029.x

11. Boswell JF, Constantino MJ, Kraus DR, et al. The expanding relevance of routinely collected outcome data for mental health care decision making. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2016;43:482-491. doi: 10.1007/s10488-015-0649-6

12. Lyon AR, Lewis CC, Boyd MR, et al. Capabilities and characteristics of digital measurement feedback systems: results from a comprehensive review. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2016;43:441-466. doi: 10.1007/s10488-016-0719-4

13. Teymoori A, Gorbunova A, Haghish FE, et al. Factorial structure and validity of depression (PHQ-9) and anxiety (GAD-7) scales after traumatic brain injury. J Clin Med. 2020;9:873. doi: 10.3390/jcm9030873

14. Kraus DR, Seligman DA, Jordan JR. Validation of a behavioral health treatment outcome and assessment tool designed for naturalistic settings: the Treatment Outcome Package. J Clin Psychol. 2005;61:285‐314. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20084

15. Boothroyd L, Dagnan D, Muncer S. Psychometric analysis of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale and the Patient Health Questionnaire using Mokken scaling and confirmatory factor analysis. Health Prim Care. 2018;2:1-4. doi: 10.15761/HPC.1000145

16. Locke BD, Buzolitz JS, Lei PW, et al. Development of the Counseling Center Assessment of Psychological Symptoms-62 (CCAPS-62). J Couns Psychol. 2011;58:97-109. doi: 10.1037/a0021282

17. Kraus DR, Boswell JF, Wright AGC, et al. Factor structure of the treatment outcome package for children. J Clin Psychol. 2010;66:627-640. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20675

18. McAleavey AA, Nordberg SS, Kraus D, et al. Errors in treatment outcome monitoring: implications for real-world psychotherapy. Can Psychol. 2010;53:105-114. doi: 10.1037/a0027833

19. Baxter EE, Alexander PC, Kraus DR, et al. Concurrent validation of the Treatment Outcome Package (TOP) for children and adolescents. J Child Fam Stud. 2016;25:2415-2422. doi: 10.1007/s10826-016-0419-4

20. Gual-Montolio P, Martínez-Borba V, Bretón-López JM, et al. How are information and communication technologies supporting routine outcome monitoring and measurement-based care in psychotherapy? A systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:3170. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17093170

21. Kraus DR, Bentley JH, Alexander PC, et al. Predicting therapist effectiveness from their own practice-based evidence. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2016;84:473‐483. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000083

22. Constantino MJ, Boswell JF, Coyne AE, et al. Effect of matching therapists to patients vs assignment as usual on adult psychotherapy outcomes. A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2021;78:960-969. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2021.1221

23. Constantino MJ, Boswell JF, Kraus DR, et al. Matching patients with therapists to improve mental health care. Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI). 2021. Accessed March 1, 2023. www.pcori.org/research-results/2015/matching-patients-therapists-improve-mental-health-care

24. Institute of Medicine. Committee on Crossing the Quality Chasm: Adaptation to Mental Health and Addictive Disorders. Improving the Quality of Health Care for Mental and Substance-Use Conditions. National Academies Press; 2006. Accessed February 21, 2023. https://nap.nationalacademies.org/read/11470/chapter/1

25. Boswell JF, Constantino MJ, Oswald JM, et al. A multimethod study of mental health care patients’ attitudes toward clinician-level performance information. Psychiatr Serv. 2021;72:452-456. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.202000366

26. Boswell JF, Constantino MJ, Oswald JM, et al. Mental health care consumers’ relative valuing of clinician performance information. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2018;86:301‐308. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000264

Dyspareunia: Keys to biopsychosocial evaluation and treatment planning

Dyspareunia is persistent or recurrent pain before, during, or after sexual contact and is not limited to cisgender individuals or vaginal intercourse.1-3 With a prevalence as high as 45% in the United States,2-5 it is one of the most common complaints in gynecologic practices.5,6

Causes and contributing factors

There are many possible causes of dyspareunia.2,4,6 While some patients have a single cause, most cases are complex, with multiple overlapping causes and maintaining factors.4,6 Identifying each contributing factor can help you appropriately address all components.

Physical conditions. The range of physical contributors to dyspareunia includes inflammatory processes, structural abnormalities, musculoskeletal dysfunctions, pelvic organ disorders, injuries, iatrogenic effects, infections, allergic reactions, sensitization, hormonal changes, medication effects, adhesions, autoimmune disorders, and other pain syndromes (TABLE 12-4,6-11).

Inadequate arousal. One of the primary causes of pain during vaginal penetration is inadequate arousal and lubrication.1,2,9-11 Arousal is the phase of the sexual response cycle that leads to genital tumescence and prepares the genitals for sexual contact through penile/clitoral erection, vaginal engorgement, and lubrication, which prevents pain and enhances pleasurable sensation.9-11

While some physical conditions can lead to an inability to lubricate, the most common causes of inadequate lubrication are psychosocial-behavioral, wherein patients have the same physical ability to lubricate as patients without genital pain but do not progress through the arousal phase.9-11 Behavioral factors such as inadequate or ineffective foreplay can fail to produce engorgement and lubrication, while psychosocial factors such as low attraction to partner, relationship stressors, anxiety, or low self-esteem can have an inhibitory effect on sexual arousal.1,2,9-11 Psychosocial and behavioral factors may also be maintaining factors or consequences of dyspareunia, and need to be assessed and treated.1,2,9-11

Psychological trauma. Exposure to psychological traumas and the development of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) have been linked with the development of pain disorders in general and dyspareunia specifically. Most patients seeking treatment for chronic pain disorders have a history of physical or sexual abuse.12 Changes in physiologic processes (eg, neurochemical, endocrine) that occur with PTSD interfere with the sexual response cycle, and sexual traumas specifically have been linked with pelvic floor dysfunction.13,14 Additionally, when PTSD is caused by a sexual trauma, even consensual sexual encounters can trigger flashbacks, intrusive memories, hyperarousal, and muscle tension that interfere with the sexual response cycle and contribute to genital pain.13

Vaginismus is both a physiologic and psychological contributor to dyspareunia.1,2,4 Patients experiencing pain can develop anxiety about repeated pain and involuntarily contract their pelvic muscles, thereby creating more pain, increasing anxiety, decreasing lubrication, and causing pelvic floor dysfunction.1-4,6 Consequently, all patients with dyspareunia should be assessed and continually monitored for symptoms of vaginismus.

Continue to: Anxiety

Anxiety. As with other pain disorders, anxiety develops around pain triggers.10,15 When expecting sexual activity, patients can experience extreme worry and panic attacks.10,15,16 The distress of sexual encounters can interfere with physiologic arousal and sexual desire, impacting all phases of the sexual response cycle.1,2

Relationship issues. Difficulty engaging in or avoidance of sexual activity can interfere with romantic relationships.2,10,16 Severe pain or vaginismus contractions can prevent penetration, leading to unconsummated marriages and an inability to conceive through intercourse.10 The distress surrounding sexual encounters can precipitate erectile dysfunction in male partners, or partners may continue to demand sexual encounters despite the patient’s pain, further impacting the relationship and heightening sexual distress.10 These stressors have led to relationships ending, patients reluctantly agreeing to nonmonogamy to appease their partners, and patients avoiding relationships altogether.10,16

Devalued self-image. Difficulties with sexuality and relationships impact the self-image of patients with dyspareunia. Diminished self-image may include feeling “inadequate” as a woman and as a sexual partner, or feeling like a “failure.”16 Women with dyspareunia often have more distress related to their body image, physical appearance, and genital self-image than do women without genital pain.17 Feeling resentment toward their body, or feeling “ugly,” embarrassed, shamed, “broken,” and “useless” also contribute to increased depressive symptoms found in patients with dyspareunia.16,18

Making the diagnosis

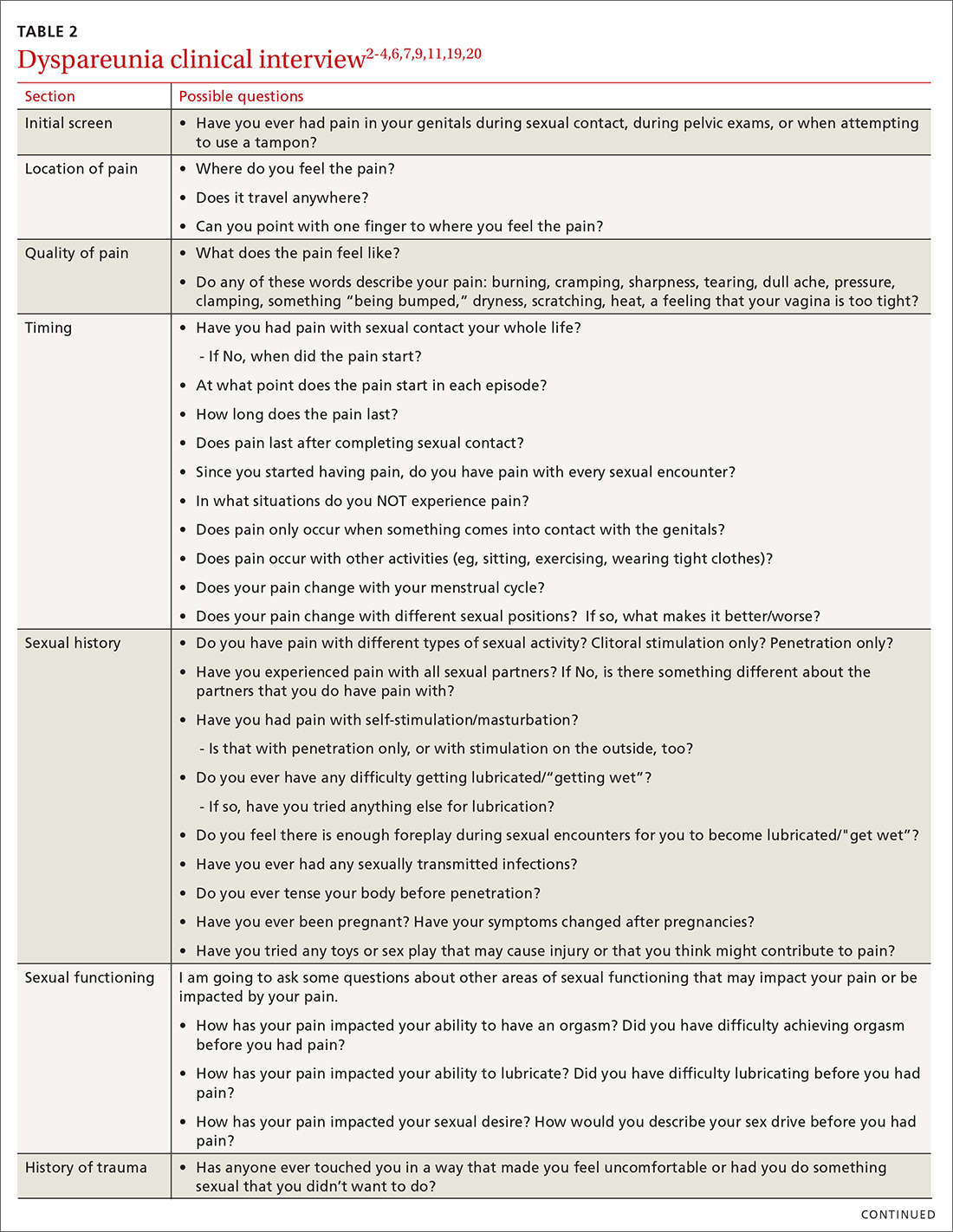

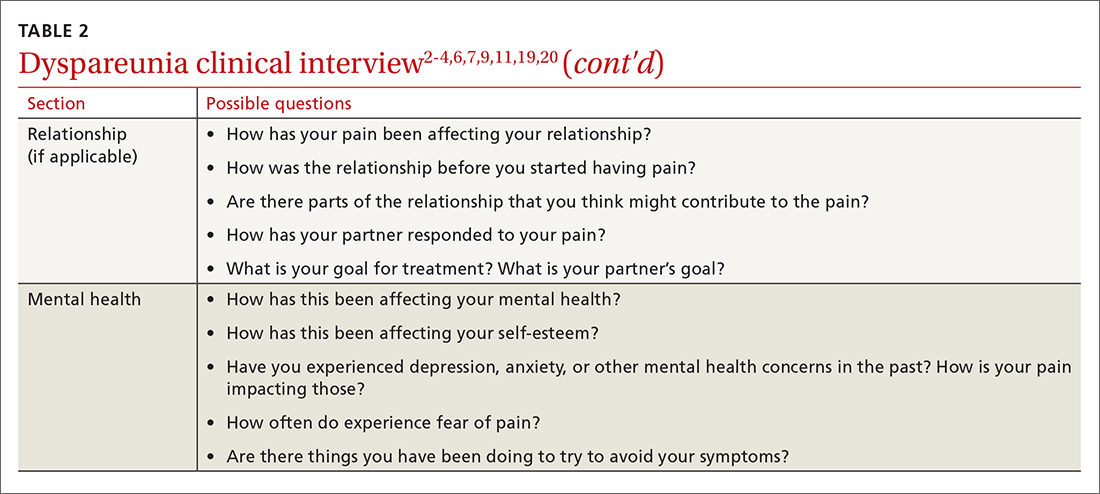

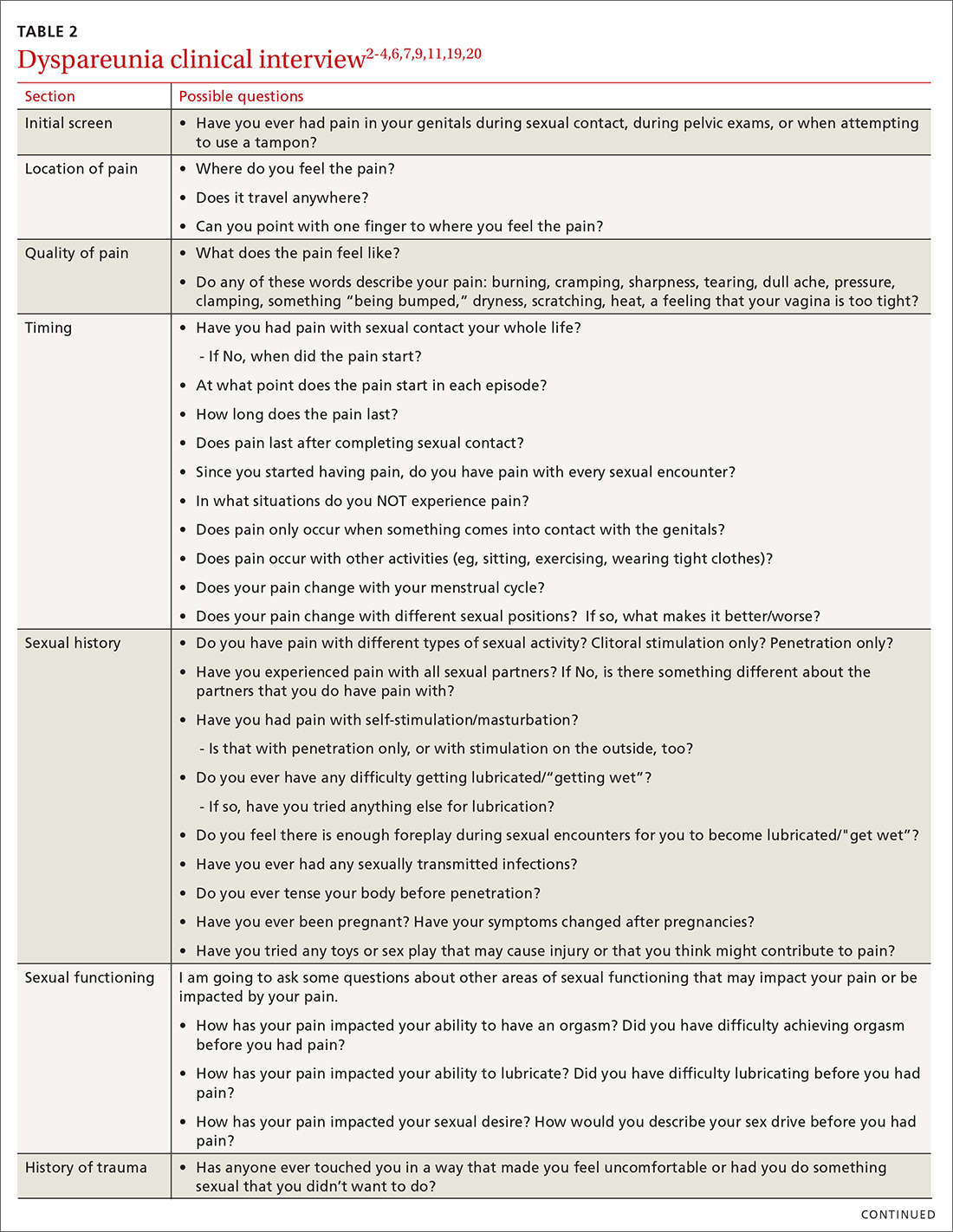

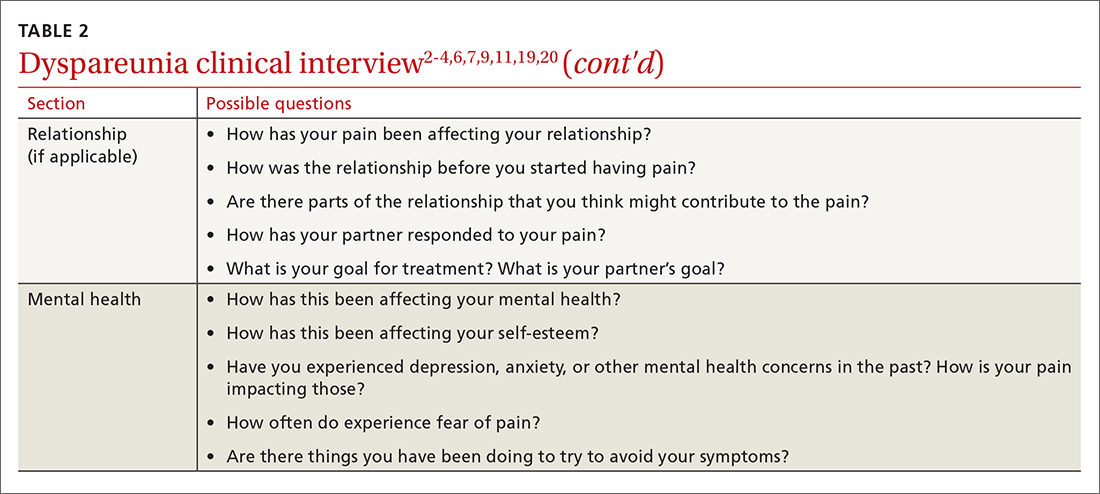

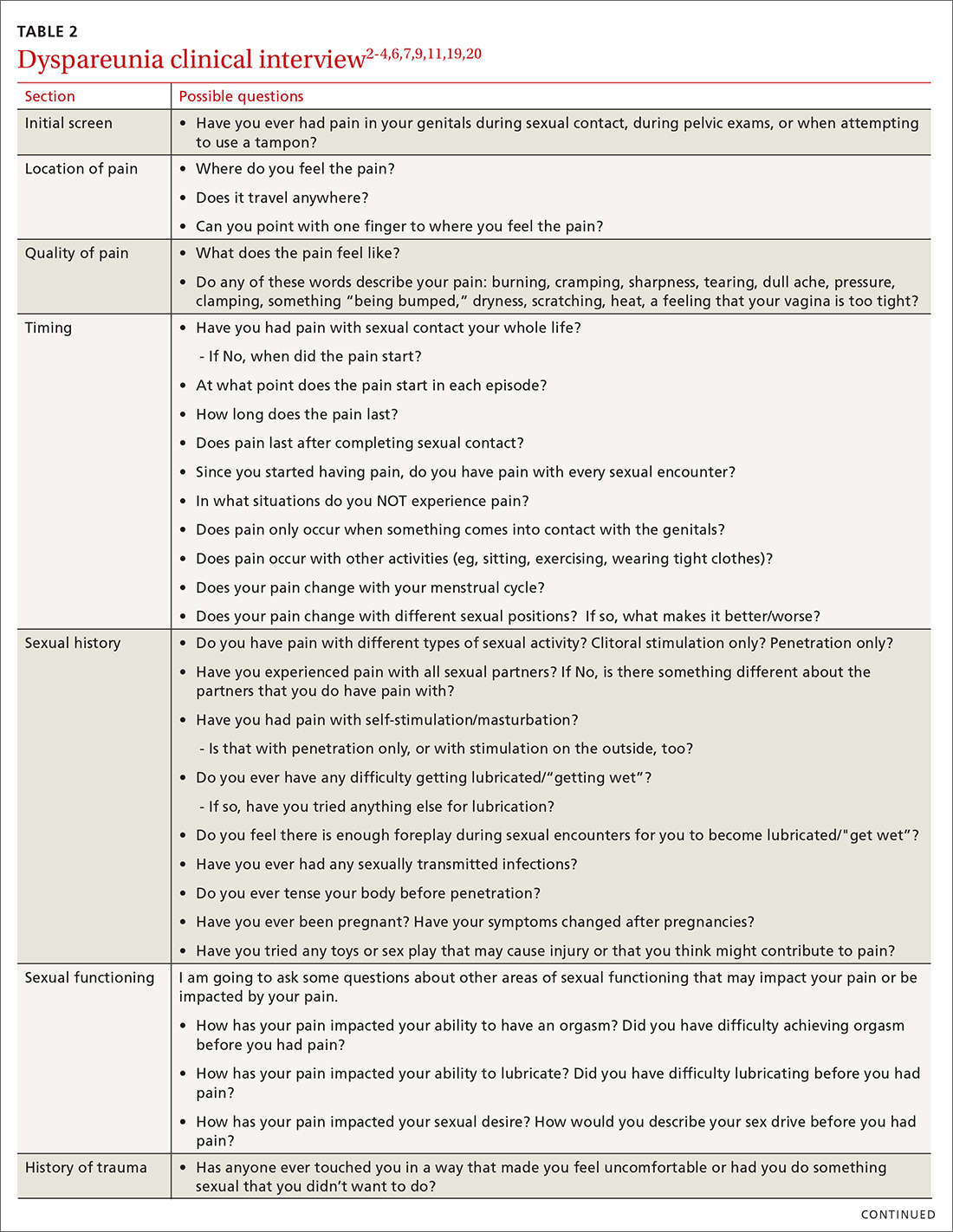

Most patients do not report symptoms unless directly asked2,7; therefore, it is recommended that all patients be screened as a part of an initial intake and before any genital exam (TABLE 22-4,6,7,9,11,19,20).4,7,21 If this screen is positive, a separate appointment may be needed for a thorough evaluation and before any attempt is made at a genital exam.4,7

Items to include in the clinical interview

Given the range of possible causes of dyspareunia and its contributing factors and symptoms, a thorough clinical interview is essential. Begin with a review of the patient’s complete medical and surgical history to identify possible known contributors to genital pain.4 Pregnancy history is of particular importance as the prevalence of postpartum dyspareunia is 35%, with risk being greater for patients who experienced dyspareunia symptoms before pregnancy.22

Knowing the location and quality of pain is important for differentiating between possible diagnoses, as is specifying dyspareunia as lifelong or acquired, superficial or deep, and primary or secondary.1-4,6 Confirm the specific location(s) of pain—eg, at the introitus, in the vestibule, on the labia, in the perineum, or near the clitoris.2,4,6 A diagram or model may be needed to help patients to localize pain.4

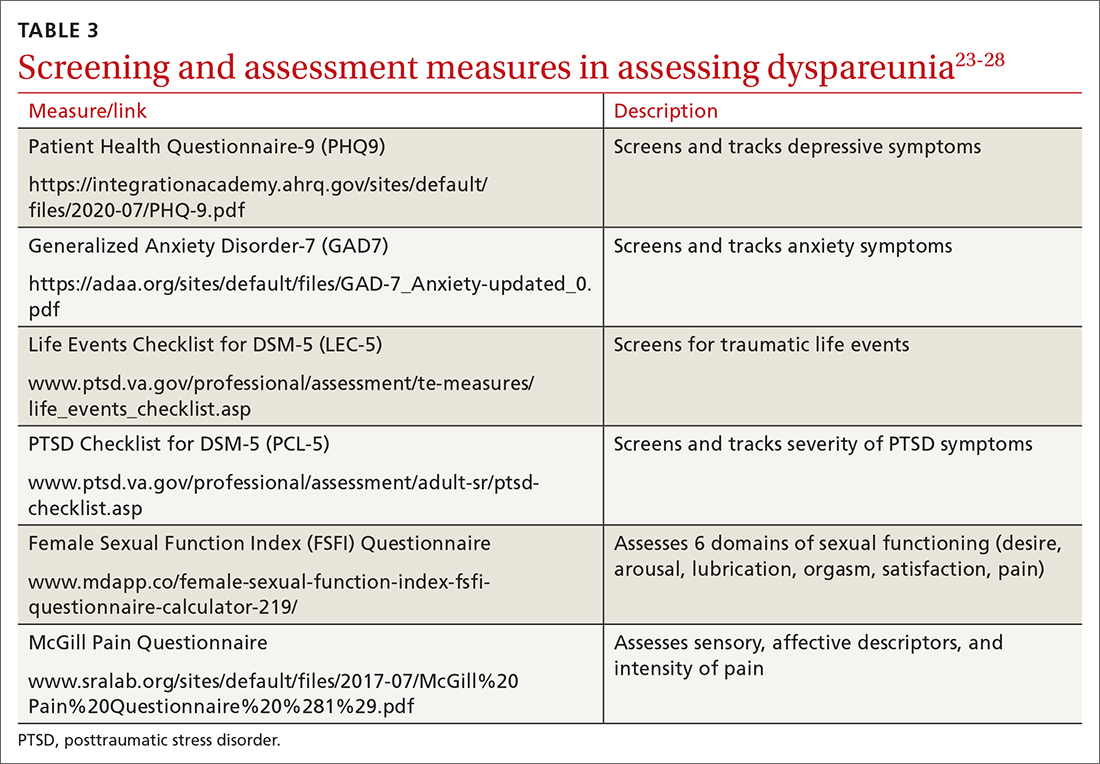

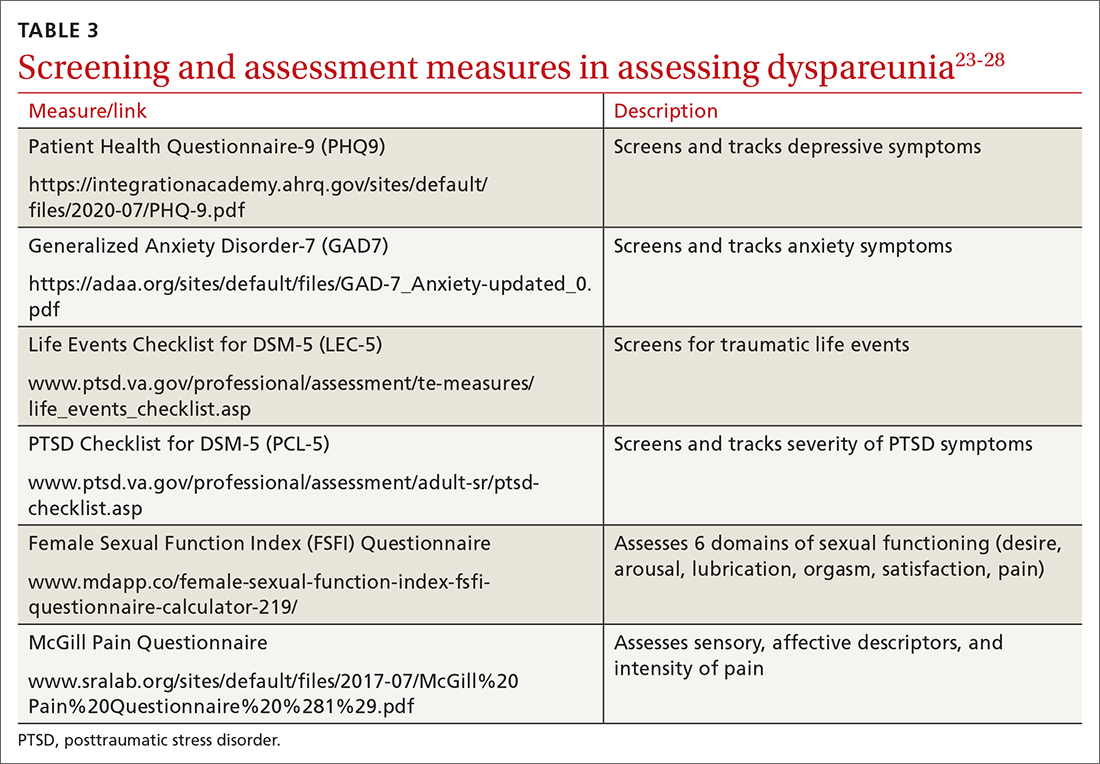

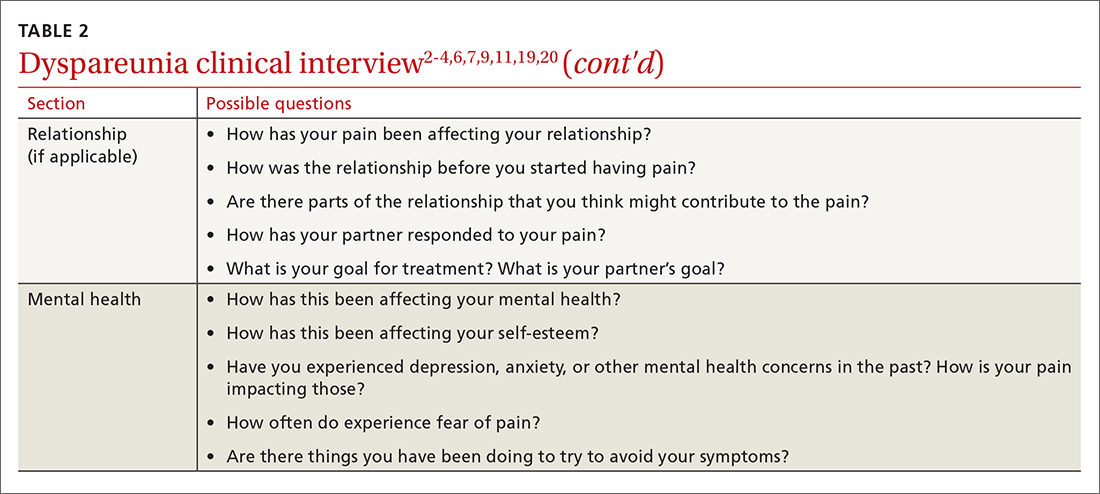

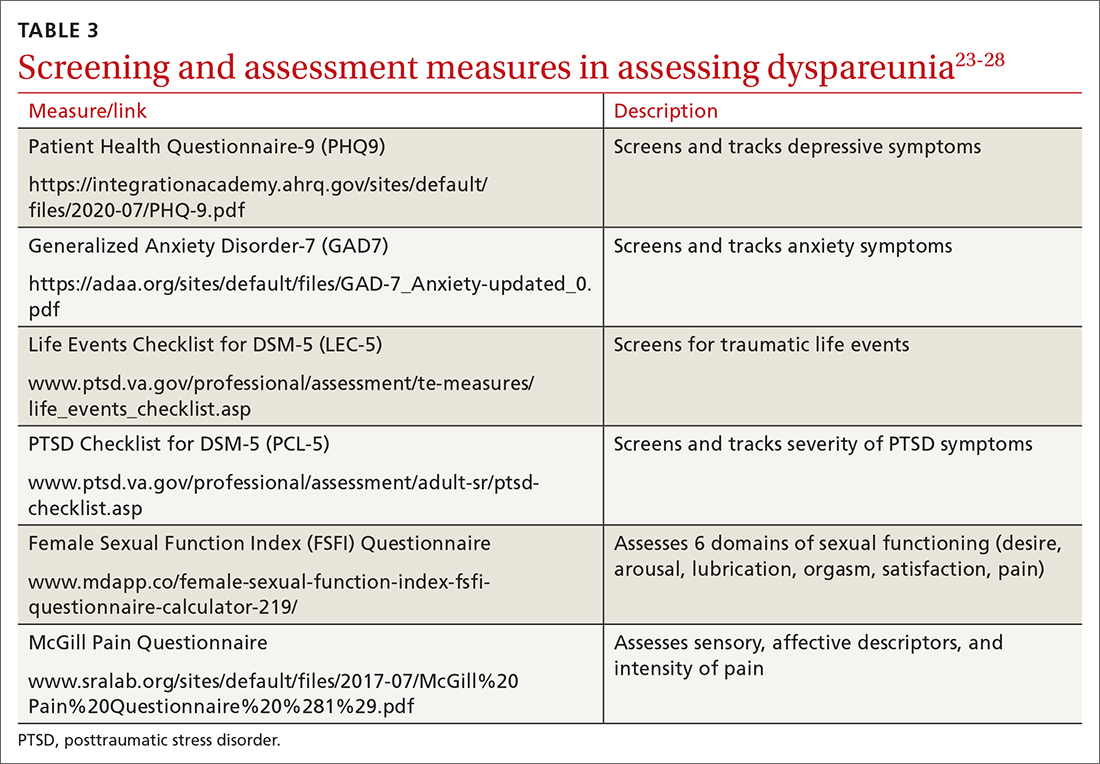

To help narrow the differential, include the following elements in your assessment: pain quality, timing (eg, initial onset, episode onset, episode duration, situational triggers), alleviating factors, symptoms in surrounding structures (eg, bladder, bowel, muscles, bones), sexual history, other areas of sexual functioning, history of psychological trauma, relationship effects, and mental health (TABLE 22-4,6,7,9,11,19,20 and Table 323-28). Screening for a history of sexual trauma is particularly important, as a recent systematic review and meta-analysis found that women with a history of sexual assault had a 42% higher risk of gynecologic problems overall, a 74% higher risk of dyspareunia, and a 71% higher risk of vaginismus than women without a history of sexual assault.29 Using measures such as the Female Sexual Function Index or the McGill Pain Questionnaire can help patients more thoroughly describe their symptoms (TABLE 323-28).3

Continue to: Guidelines for the physical exam

Guidelines for the physical exam

Before the exam, ensure the patient has not used any topical genital treatment in the past 2 weeks that may interfere with sensitivity to the exam.4 To decrease patients’ anxiety about the exam, remind them that they can stop the exam at any time.7 Also consider offering the use of a mirror to better pinpoint the location of pain, and to possibly help the patient learn more about her anatomy.2,7

Begin the exam by palpating surrounding areas that may be involved in pain, including the abdomen and musculoskeletal features.3,6,19 Next visually inspect the external genitalia for lesions, abrasions, discoloration, erythema, or other abnormal findings.2,3,6 Ask the patient for permission before contacting the genitals. Because the labia may be a site of pain, apply gentle pressure in retracting it to fully examine the vestibule.6,7 Contraction of the pelvic floor muscles during approach or initial palpation could signal possible vaginismus.4