User login

THE CASE

DeSean W,* a 47-year-old man, returned to his primary care clinic with a new complaint of epigastric burning that had been bothering him for the past 4 months. He had tried several over-the-counter remedies, which provided no relief. He also remained concerned—despite assurances to the contrary at previous clinic visits—that he had contracted a sexually-transmitted disease (STD) after going to a bar one night 4 to 5 months ago. At 2 other clinic visits since that time, STD test results were negative. At this current visit, symptoms and details of sexual history were unchanged since the last visit, with the exception of the epigastric pain.

When asked if he thought he had contracted an STD through a sexual encounter the night he went to the bar, he emphatically said he would not cheat on his wife. Surprisingly, given his concern, he avoided further discussion on modes of contracting an STD.

The physician prescribed ranitidine 150 mg bid for the epigastric burning and explained, once more, the significance of the STD test results. However, he also decided to further examine Mr. W’s concern about STDs and the night he may have contracted one.

HOW WOULD YOU PROCEED WITH THIS PATIENT?

*The patient’s name has been changed to protect his privacy.

SCOPE OF THE PROBLEM

Despite being as common as asthma, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) often remains undiagnosed and untreated in primary care.1 In brief, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) defines PTSD as persistent and long-term changes in thoughts or mood following actual or threatened exposure to death, serious injury, or sexual assault that leads to re-experiencing, functional impairment, physiologic stress reactions, and avoidance of thoughts or situations associated with the original trauma.2 More than one in 10 women and one in 20 men experience PTSD in their lifetime.2,3 Population-based studies have not yet determined the prevalence among children.3 Almost 40% of US adults report having experienced a trauma before age 13, and about one-third of these go on to develop PTSD.4

Individuals with PTSD have higher rates of somatic complaints, overall medical utilization, prescription use, physical and social disability, attempted suicide, and all-cause mortality.3,5-7 PTSD is associated with increased risk for cardiac, gastrointestinal, metabolic, and immunologic illnesses, other psychiatric illnesses, risky health behaviors, and decreased medical adherence.4,6 Additionally, prevention and treatment efforts for STDs and obesity are less effective among those with trauma histories.4 Thus, detection and treatment of PTSD improves the likelihood of successfully treating other health concerns.

THE ESSENTIALS OF A PTSD DIAGNOSIS

DSM-5 diagnosis of PTSD requires the experience of a trauma and resultant symptoms from each of 4 symptom-clusters:2

- one or more re-experiencing symptoms (eg, intrusive memories or recurrent distressing dreams, psychological distress or physiologic reactions to reminders of the trauma)

- one or more avoidance symptoms (eg, avoidance of trauma memories or of people and places that trigger a reminder of the trauma)

- two or more changes in thoughts or mood (eg, negative beliefs about self or others, social detachment, anhedonia)

- two or more changes in arousal activity (eg, sleep problems, hypervigilance, inability to concentrate).

Since many people experiencing traumas do not develop PTSD,5,8 symptoms must last at least one month to meet the criteria for diagnosis.2 Sexual trauma, experiencing multiple traumas, and lack of social support increase the risk that an individual will develop PTSD.9-11 Notably, symptom onset will be delayed 6 months or more in some individuals,2,8 making it more difficult for those patients and clinicians to connect symptoms to the trauma.12

Differential diagnosis

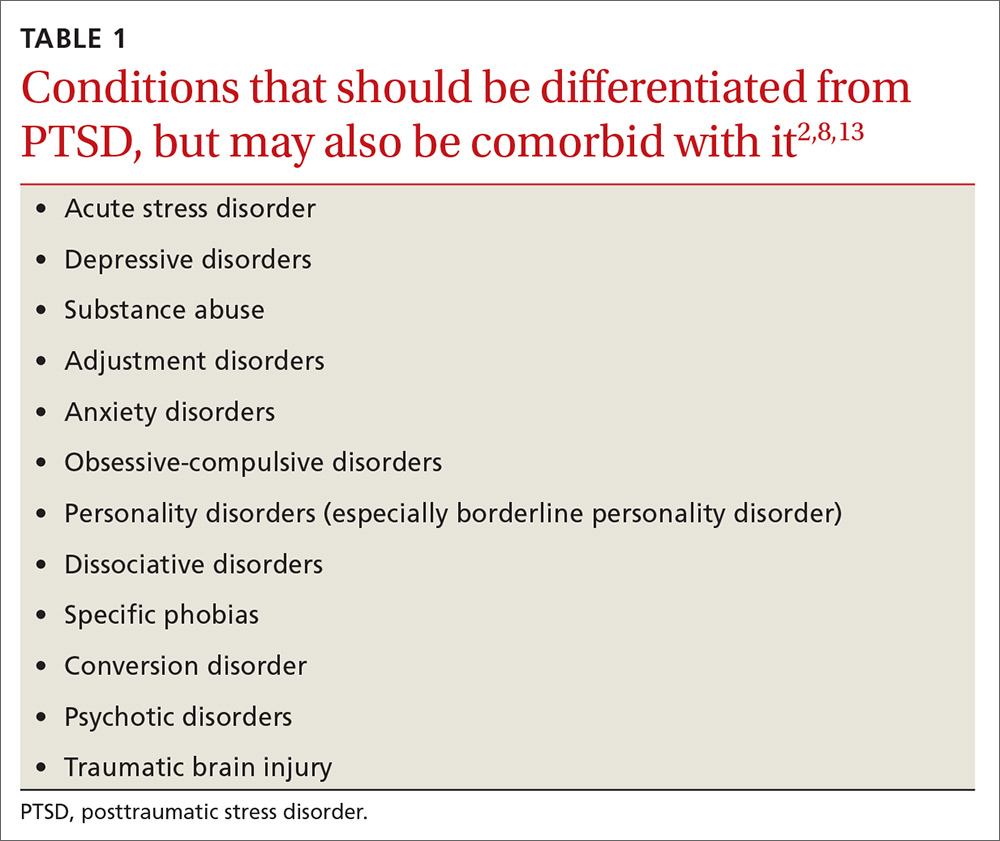

PTSD must be differentiated from other mental health conditions with overlapping symptoms (TABLE 12,8,13), but it may also be comorbid with one or more of these other conditions. When patients with PTSD do report mental health symptoms, providers often focus on the depressive symptoms that overlap with PTSD, and on substance use, which often accompanies PTSD, leaving PTSD undetected.9

Given that depressed/irritable mood, decreased participation in pleasurable activities, negative views of the world, attention difficulties, sleep difficulties, feelings of guilt, and agitation/restlessness are symptoms of both depression and PTSD,2 it is particularly important to screen patients with depressive symptoms for trauma history.

Why PTSD is often missed

Due to the impact of PTSD on overall health, the rates of PTSD in primary care clinics may be higher than in the general population.14 Thus, primary care clinicians are likely seeing PTSD more often than they realize. In fact, a systematic review showed that clinicians detected 0% to 52% of their patients with PTSD, missing at least half of all PTSD diagnoses.9

Detecting PTSD can be challenging for several reasons. Symptoms can span the emotional, social, physical, and behavioral aspects of an individual’s life, so patients and clinicians alike may regard symptoms as unrelated to PTSD.8 Primary symptom presentation may vary, with some people reporting anxiety symptoms, others mostly depressive symptoms, and others arousal, dissociative, or—as in our patient’s case—somatic symptoms.2 In affected children, parents may report emotional or behavioral problems without mentioning the trauma.2 Additionally, for traumas that were not a single event, such as long-term child abuse, patients may have difficulty identifying symptom onset.2

CASE

The physician screened Mr. W for trauma exposure as part of the differential. Mr. W revealed that he had blacked out at the bar, despite drinking only moderately, and that he awoke with anal pain. He believed he had been drugged and sexually assaulted. Further screening for PTSD symptoms related to this event confirmed multiple associated symptoms. He acknowledged that his epigastric pain had started soon after the trauma and, after further discussion, began to link his stomach pain and other new symptoms revealed by the PTSD screen (hypervigilance, avoidance, change in mood) to the trauma.

As happened in this case, most PTSD patients present with somatic complaints rather than reporting a traumatic experience and having associated effects. This in turn usually leads clinicians to consider only non-PTSD diagnoses.6,9,15 Core avoidance symptoms are a major reason for such a presentation in PTSD patients.14 Patients avoid thoughts, feelings, and conversations that remind them of the trauma.13 As a result, they are less likely to voluntarily report trauma. They avoid thinking about how their current symptoms may be associated with their trauma and are reluctant to talk about their trauma with clinicians.5,9,8,12

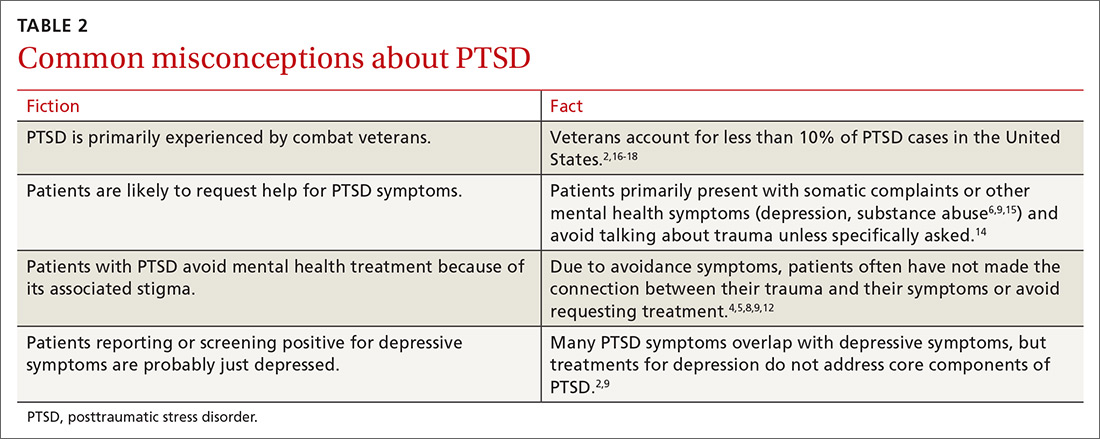

Another barrier to diagnosis is a belief that PTSD is primarily experienced by combat veterans1 (TABLE 22,4-6,8,9,12,14-18). While PTSD is detected more often among veterans due to regular screening through the Department of Veterans Affairs,14 the vast majority of PTSD cases are related to civilian traumas such as sexual assault, child abuse, and car accidents.5,9 In fact, the estimated

SCREENING: WHAT TO LOOK FOR

Since individuals with PTSD mainly seek treatment for associated physical symptoms,14 primary care is particularly important for identification of PTSD and treatment access. The US Preventative Services Task Force does not yet have any recommendations for screening for PTSD. The American Psychiatric Association recommends that a trauma history be included in all initial psychiatric evaluations of adults.19 Screens can target high-risk populations and can be repeated across the lifespan,9 as traumas can occur at any age and symptoms may not emerge until years after the trauma.2,4 Factors in a patient’s history associated with high risk of PTSD include the following:

- known trauma exposure (eg, treatment at the emergency department following motor vehicle collision, natural disaster, assault),6

- frequent medical visits or unexplained physical symptoms,5,8

- family members who are trauma victims,8

- involvement in juvenile justice system,4,12

- sensitive or invasive exams (eg, pelvic exams) that trigger symptoms or contribute to retraumatization,12,20 and

- any medical condition (eg, hypertension, chronic pain, sleep disorder), self-destructive behavior (eg, drug or alcohol abuse, low impulse control), or social/occupational issues (eg, unemployment, social isolation, fighting) with a known link to PTSD.2,4,6,8

The first step in screening. Given a patient’s reported symptoms, assess for trauma exposure to determine whether PTSD should be included in the differential diagnosis. Overlooking PTSD as a possible source of symptoms can result in misattributing them to other causes.4,8 Listing common traumas, or using a standardized list such as the Life Events Checklist, can help identify patients with trauma exposure.8,21 However, do not make the patient provide details of the traumatic event(s), as that can exacerbate symptoms if PTSD is present.6 It is sufficient to know the category of the trauma (eg, sexual assault) without making the patient describe who was involved and what happened.6

The second step in screening. If a patient reveals trauma exposure, consider using an instrument such as the Primary Care PTSD Screen (PC-PTSD) or the PTSD Checklist, both available online, to screen for PTSD symptoms related to the identified trauma.6,9,21-23 Since these measures screen for symptoms but do not ask about trauma exposure, false positives can occur if a trauma is not first identified (such as through the Life Events Checklist) due to symptom overlap with other conditions (TABLE 12,8,13).21

Treatment is effective, even decades after a traumatic event

Provide anyone who has been traumatized with information about common after effects, symptoms of PTSD, and available treatments.8 Keep in mind that initial symptom severity after trauma exposure does not correlate with long-term symptoms,8 and about half of adults will recover without treatment within 3 months.1,2,5 The first month of symptoms may be addressed with patient education and watchful waiting. But if symptoms don’t subside after a month, consider offering treatment1 with the understanding that, for some individuals, symptoms may yet resolve on their own.

Detecting and treating PTSD early can decrease its deleterious effects on health and cut down on years of functional impairment.1 Even decades after an initial traumatic event, PTSD treatments can be effective.8 Children may experience functional impairment without meeting full criteria for PTSD, and can also benefit from treatment.7

INTEGRATING EXPOSURE AND COGNITIVE THERAPIES IS KEY

Offer any patient who meets criteria for PTSD a referral for exposure therapy and trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy (TF-CBT), the first-line treatments for PTSD.1,4,8,24,25

Exposure therapies for PTSD are supported by strong evidence and help patients to become desensitized to distressful memories through gradual, repeated exposures in a relaxed or safe space.8,26

Cognitive methods, such as cognitive processing therapy, cognitive behavioral therapy, and cognitive reprocessing have moderate strength of evidence, and may be combined with exposure therapy.26 Cognitive therapies help patients change thoughts, beliefs, and behaviors that contribute to PTSD symptoms.8,26

Exposure and TF-CBT have the most empirical evidence for child, adolescent, and adult PTSD, and are effective for the range of PTSD symptoms,4,8,25 including avoidance—a fundamental component of PTSD that drives other PTSD symptoms27—comorbid depression, and other emotions associated with trauma (eg, shame, guilt, and anger).8,25 Family involvement is recommended for children and adolescents.4

For patients with comorbid substance abuse, offer integrated PTSD/substance abuse treatment, which is more effective than isolated treatment of each.4 Relaxation training can be helpful as an adjunct to TF-CBT, but is not sufficient as a stand-alone treatment.13 Other psychotherapies, such as supportive, psychodynamic, systemic, and hypnotherapy, have not proved effective.14

Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR), a much publicized but controversial treatment, integrates components of exposure and cognitive therapies with therapist-directed eye movements.28-30 Patients imagine their trauma while the therapist directs their eye movements, which is thought to provide exposure to trauma images and memories, thereby reducing symptoms. EMDR has been found to reduce PTSD symptoms with a low to moderate strength-of-evidence rating.26 However, it has not proved more effective than other exposure and cognitive therapies, and its unique component (eg, eye movements) has not added any effect to outcomes.28-31

Other newer therapies, such as Acceptance and Commitment Therapy7,24,27 and online and computer-assisted treatments, are being evaluated.14

Medications take on an adjunct role to therapy

Drug treatment of PTSD has not been effective in children or adolescents.4,8 In adults, medications have helped relieve some symptoms of PTSD. However, given their low effect sizes, medications are not recommended as first-line treatments over exposure and TF-CBT. Their usefulness lies chiefly in an adjunct role to exposure and cognitive therapies or for patients who refuse psychotherapy.4,8,25

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors such as fluoxetine, paroxetine, and sertraline, have been effective for such PTSD symptoms as intrusive thoughts, negative or irritable mood, anxiety, restlessness, attention difficulties, and hyperarousal.1,8

While benzodiazepines have been used to control anxiety, hyperarousal, and insomnia, they have not been effective for most other PTSD symptoms, including avoidance, re-experiencing, and cognitive symptoms. Furthermore, they are not recommended given their augmentative effect on other related symptoms and associated conditions (eg, dissociation, disinhibition, substance abuse) and possible interference with desensitization that occurs in exposure therapy.1,5

If a patient has significant insomnia and PTSD-related nightmares, consider starting prazosin at 1 mg/d and titrating up to an effective dose, which typically ranges from 5 to 20 mg per day.1,5 Additionally, trazodone or antihistamines may be used to enhance sleep.1

COORDINATION OF CARE

Upon identifying PTSD and offering treatment, introduce the patient to a mental health provider as part of the referral process, which strongly encourages patient engagement in treatment.14 Collaborate with the psychotherapist throughout treatment to facilitate a biopsychosocial approach to the patient’s care, and coordinate the monitoring and treatment of any comorbid physical conditions.

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration has proposed a framework for multisystem Trauma-Informed Care (TIC), in which the primary care physician has many roles, including:12,20

- recording or communicating sensitive private information to other providers through the electronic medical record in a manner that does not interfere with a patient’s development of trust or lead to exposure and retraumatization,

- performing invasive physical exams in a sensitive and patient-centered manner, and

- using support and shared decision-making in clinical encounters.

Physicians can also connect patients with PTSD to programs or groups that aid in developing resilience, such as physical exercise classes, social support networks, and community involvement opportunities.4

CASE

The physician referred Mr. W to an onsite psychologist. At a subsequent clinic visit in which he was seen by a different primary care physician, Mr. W expressed new concerns about shoulder pain and changes in a mole. During this visit, Mr. W was asked whether he had followed up on the earlier referral for counseling. He replied that he had attended an intake appointment with the psychologist, but that he had not wanted to talk about what had happened to him and therefore avoided future appointments.*

He remained concerned that he might have an STD, but declined medication for PTSD because he felt he was “moving on” with his life.

*Author’s note: Getting patients to open up about their trauma exposure can be difficult. If the patient isn’t ready, simply bringing up the experience can trigger avoidance. It’s often helpful to encourage patients to first develop a relationship with their therapist, then later discuss the details of their trauma when they are ready. This encourages patients to engage in the counseling process.

CORRESPONDENCE

Adrienne A. Williams, PhD, Department of Family Medicine, University of Illinois at Chicago College of Medicine, 1919 W Taylor Street, MC663, Chicago, IL 60612; awms@uic.edu.

1. Bobo WV, Warner CH, Warner CM. The management of post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in the primary care setting. South Med J. 2007;100:797-802.

2. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013.

3. Gradus JL. Epidemiology of PTSD. National Center for PTSD. Available at: http://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/PTSD-overview/epidemiological-facts-ptsd.asp. Updated 2017. Accessed August 16, 2017.

4. Gerson R, Rappaport N. Traumatic stress and posttraumatic stress disorder in youth: recent research findings on clinical impact, assessment, and treatment. J Adolesc Health. 2013;52:137-143.

5. Zohar J, Juven-Wetzler A, Myers V, et al. Post-traumatic stress disorder: facts and fiction. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2008;21:74-77.

6. Spoont MR, Williams JW Jr, Kehle-Forbes S, et al. Does this patient have posttraumatic stress disorder? Rational clinical examination systematic review. JAMA. 2015;314:501-510.

7. Woidneck MR, Morrison KL, Twohig MP. Acceptance and commitment therapy for the treatment of posttraumatic stress among adolescents. Behav Modif. 2014;38:451-476.

8. National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health (UK). Post-traumatic stress disorder: the management of PTSD in adults and children in primary and secondary care. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK56494. Accessed August 16, 2017.

9. Greene T, Neria Y, Gross R. Prevalence, detection and correlates of PTSD in the primary care setting: a systematic review. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2016;23:160-180.

10. Gavranidou M, Rosner R. The weaker sex? Gender and post-traumatic stress disorder. Depress Anxiety. 2003;17:130-139.

11. Brewin CR, Andrews B, Valentine JD. Meta-analysis of risk factors for posttraumatic stress disorder in trauma-exposed adults. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;68:748-766.

12. SAMHSA’s Trauma and Justice Strategic Initiative. SAMHSA’s concept of trauma and guidance for a trauma-informed approach. Available at: http://store.samhsa.gov/shin/content/SMA14-4884/SMA14-4884.pdf. Accessed September 13, 2017.

13. Mulick PS, Landes SJ, Kanter JW. Contextual behavior therapies in the treatment of PTSD: a review. Int J Behav Consult Ther. 2005;1:223-238.

14. Possemato K. The current state of intervention research for posttraumatic stress disorder within the primary care setting. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2011;18:268-280.

15. Forneris CA, Gartlehner G, Brownley KA, et al. Interventions to prevent post-traumatic stress disorder: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2013;44:635-650.

16. Trivedi RB, Post EP, Sun H, et al. Prevalence, comorbidity, and prognosis of mental health among US veterans. Am J Public Health. 2015;105:2564-2569.

17. United States Census Bureau. Facts for features: Veteran’s day 2016: Nov. 11. Available at: https://www.census.gov/newsroom/facts-for-features/2016/cb16-ff21.html. Accessed August 16, 2017.

18. United States Census Bureau. U.S. and World Population Clock. Available at: https://www.census.gov/popclock/. Accessed August 16, 2017.

19. American Psychiatric Association. Guidelines and implementation. In: Practice Guidelines for the Psychiatric Evaluation of Adults. 3rd ed. Arlington, Va: American Psychiatric Association; 2015:9-45.

20. Williams AA, Williams M. A guide to performing pelvic speculum exams: a patient-centered approach to reducing iatrogenic effects. Teach Learn Med. 2013;25:383-391.

21. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Life events checklist for DSM-5 (LEC-5). Available at: http://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/assessment/te-measures/life_events_checklist.asp. Accessed September 13, 2017.

22. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Primary care PTSD screen for DSM-5 (PC-PTSD). Available at: http://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/assessment/screens/pc-ptsd.asp. Accessed September 13, 2017.

23. Spoont M, Arbisi P, Fu S, et al. Screening for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) in Primary Care: A Systematic Review. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK126691/. Accessed Sept 13, 2017

24. Gallagher MW, Thompson-Hollands J, Bourgeois ML, et al. Cognitive behavioral treatments for adult posttraumatic stress disorder: current status and future directions. J Contemp Psychother. 2015;45:235-243.

25. Kar N. Cognitive behavioral therapy for the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder: a review. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2011;7:167-181.

26. Cusack K, Jonas DE, Forneris CA, et al. Psychological treatments for adults with posttraumatic stress disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2016;43:128-141.

27. Thompson BL, Luoma JB, LeJeune JT. Using acceptance and commitment therapy to guide exposure-based interventions for posttraumatic stress disorder. J Contemp Psychother. 2013;43:133-140.

28. Lohr JM, Hooke W, Gist R, et al. Novel and controversial treatments for trauma-related stress disorders. In: Lilienfeld SO, Lynn SJ, Lohr JM, eds. Science and Pseudoscience in Clinical Psychology. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2003:243-272.

29. Sikes C, Sikes V. EMDR: Why the controversy? Traumatol. 2003;9:169-182.

30. Davidson PR, Parker KCH. Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR): a meta-analysis. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2001;69:305-316.

31. Devilly GJ. Power therapies and possible threats to the science of psychology and psychiatry. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2005;39:437-445.

THE CASE

DeSean W,* a 47-year-old man, returned to his primary care clinic with a new complaint of epigastric burning that had been bothering him for the past 4 months. He had tried several over-the-counter remedies, which provided no relief. He also remained concerned—despite assurances to the contrary at previous clinic visits—that he had contracted a sexually-transmitted disease (STD) after going to a bar one night 4 to 5 months ago. At 2 other clinic visits since that time, STD test results were negative. At this current visit, symptoms and details of sexual history were unchanged since the last visit, with the exception of the epigastric pain.

When asked if he thought he had contracted an STD through a sexual encounter the night he went to the bar, he emphatically said he would not cheat on his wife. Surprisingly, given his concern, he avoided further discussion on modes of contracting an STD.

The physician prescribed ranitidine 150 mg bid for the epigastric burning and explained, once more, the significance of the STD test results. However, he also decided to further examine Mr. W’s concern about STDs and the night he may have contracted one.

HOW WOULD YOU PROCEED WITH THIS PATIENT?

*The patient’s name has been changed to protect his privacy.

SCOPE OF THE PROBLEM

Despite being as common as asthma, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) often remains undiagnosed and untreated in primary care.1 In brief, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) defines PTSD as persistent and long-term changes in thoughts or mood following actual or threatened exposure to death, serious injury, or sexual assault that leads to re-experiencing, functional impairment, physiologic stress reactions, and avoidance of thoughts or situations associated with the original trauma.2 More than one in 10 women and one in 20 men experience PTSD in their lifetime.2,3 Population-based studies have not yet determined the prevalence among children.3 Almost 40% of US adults report having experienced a trauma before age 13, and about one-third of these go on to develop PTSD.4

Individuals with PTSD have higher rates of somatic complaints, overall medical utilization, prescription use, physical and social disability, attempted suicide, and all-cause mortality.3,5-7 PTSD is associated with increased risk for cardiac, gastrointestinal, metabolic, and immunologic illnesses, other psychiatric illnesses, risky health behaviors, and decreased medical adherence.4,6 Additionally, prevention and treatment efforts for STDs and obesity are less effective among those with trauma histories.4 Thus, detection and treatment of PTSD improves the likelihood of successfully treating other health concerns.

THE ESSENTIALS OF A PTSD DIAGNOSIS

DSM-5 diagnosis of PTSD requires the experience of a trauma and resultant symptoms from each of 4 symptom-clusters:2

- one or more re-experiencing symptoms (eg, intrusive memories or recurrent distressing dreams, psychological distress or physiologic reactions to reminders of the trauma)

- one or more avoidance symptoms (eg, avoidance of trauma memories or of people and places that trigger a reminder of the trauma)

- two or more changes in thoughts or mood (eg, negative beliefs about self or others, social detachment, anhedonia)

- two or more changes in arousal activity (eg, sleep problems, hypervigilance, inability to concentrate).

Since many people experiencing traumas do not develop PTSD,5,8 symptoms must last at least one month to meet the criteria for diagnosis.2 Sexual trauma, experiencing multiple traumas, and lack of social support increase the risk that an individual will develop PTSD.9-11 Notably, symptom onset will be delayed 6 months or more in some individuals,2,8 making it more difficult for those patients and clinicians to connect symptoms to the trauma.12

Differential diagnosis

PTSD must be differentiated from other mental health conditions with overlapping symptoms (TABLE 12,8,13), but it may also be comorbid with one or more of these other conditions. When patients with PTSD do report mental health symptoms, providers often focus on the depressive symptoms that overlap with PTSD, and on substance use, which often accompanies PTSD, leaving PTSD undetected.9

Given that depressed/irritable mood, decreased participation in pleasurable activities, negative views of the world, attention difficulties, sleep difficulties, feelings of guilt, and agitation/restlessness are symptoms of both depression and PTSD,2 it is particularly important to screen patients with depressive symptoms for trauma history.

Why PTSD is often missed

Due to the impact of PTSD on overall health, the rates of PTSD in primary care clinics may be higher than in the general population.14 Thus, primary care clinicians are likely seeing PTSD more often than they realize. In fact, a systematic review showed that clinicians detected 0% to 52% of their patients with PTSD, missing at least half of all PTSD diagnoses.9

Detecting PTSD can be challenging for several reasons. Symptoms can span the emotional, social, physical, and behavioral aspects of an individual’s life, so patients and clinicians alike may regard symptoms as unrelated to PTSD.8 Primary symptom presentation may vary, with some people reporting anxiety symptoms, others mostly depressive symptoms, and others arousal, dissociative, or—as in our patient’s case—somatic symptoms.2 In affected children, parents may report emotional or behavioral problems without mentioning the trauma.2 Additionally, for traumas that were not a single event, such as long-term child abuse, patients may have difficulty identifying symptom onset.2

CASE

The physician screened Mr. W for trauma exposure as part of the differential. Mr. W revealed that he had blacked out at the bar, despite drinking only moderately, and that he awoke with anal pain. He believed he had been drugged and sexually assaulted. Further screening for PTSD symptoms related to this event confirmed multiple associated symptoms. He acknowledged that his epigastric pain had started soon after the trauma and, after further discussion, began to link his stomach pain and other new symptoms revealed by the PTSD screen (hypervigilance, avoidance, change in mood) to the trauma.

As happened in this case, most PTSD patients present with somatic complaints rather than reporting a traumatic experience and having associated effects. This in turn usually leads clinicians to consider only non-PTSD diagnoses.6,9,15 Core avoidance symptoms are a major reason for such a presentation in PTSD patients.14 Patients avoid thoughts, feelings, and conversations that remind them of the trauma.13 As a result, they are less likely to voluntarily report trauma. They avoid thinking about how their current symptoms may be associated with their trauma and are reluctant to talk about their trauma with clinicians.5,9,8,12

Another barrier to diagnosis is a belief that PTSD is primarily experienced by combat veterans1 (TABLE 22,4-6,8,9,12,14-18). While PTSD is detected more often among veterans due to regular screening through the Department of Veterans Affairs,14 the vast majority of PTSD cases are related to civilian traumas such as sexual assault, child abuse, and car accidents.5,9 In fact, the estimated

SCREENING: WHAT TO LOOK FOR

Since individuals with PTSD mainly seek treatment for associated physical symptoms,14 primary care is particularly important for identification of PTSD and treatment access. The US Preventative Services Task Force does not yet have any recommendations for screening for PTSD. The American Psychiatric Association recommends that a trauma history be included in all initial psychiatric evaluations of adults.19 Screens can target high-risk populations and can be repeated across the lifespan,9 as traumas can occur at any age and symptoms may not emerge until years after the trauma.2,4 Factors in a patient’s history associated with high risk of PTSD include the following:

- known trauma exposure (eg, treatment at the emergency department following motor vehicle collision, natural disaster, assault),6

- frequent medical visits or unexplained physical symptoms,5,8

- family members who are trauma victims,8

- involvement in juvenile justice system,4,12

- sensitive or invasive exams (eg, pelvic exams) that trigger symptoms or contribute to retraumatization,12,20 and

- any medical condition (eg, hypertension, chronic pain, sleep disorder), self-destructive behavior (eg, drug or alcohol abuse, low impulse control), or social/occupational issues (eg, unemployment, social isolation, fighting) with a known link to PTSD.2,4,6,8

The first step in screening. Given a patient’s reported symptoms, assess for trauma exposure to determine whether PTSD should be included in the differential diagnosis. Overlooking PTSD as a possible source of symptoms can result in misattributing them to other causes.4,8 Listing common traumas, or using a standardized list such as the Life Events Checklist, can help identify patients with trauma exposure.8,21 However, do not make the patient provide details of the traumatic event(s), as that can exacerbate symptoms if PTSD is present.6 It is sufficient to know the category of the trauma (eg, sexual assault) without making the patient describe who was involved and what happened.6

The second step in screening. If a patient reveals trauma exposure, consider using an instrument such as the Primary Care PTSD Screen (PC-PTSD) or the PTSD Checklist, both available online, to screen for PTSD symptoms related to the identified trauma.6,9,21-23 Since these measures screen for symptoms but do not ask about trauma exposure, false positives can occur if a trauma is not first identified (such as through the Life Events Checklist) due to symptom overlap with other conditions (TABLE 12,8,13).21

Treatment is effective, even decades after a traumatic event

Provide anyone who has been traumatized with information about common after effects, symptoms of PTSD, and available treatments.8 Keep in mind that initial symptom severity after trauma exposure does not correlate with long-term symptoms,8 and about half of adults will recover without treatment within 3 months.1,2,5 The first month of symptoms may be addressed with patient education and watchful waiting. But if symptoms don’t subside after a month, consider offering treatment1 with the understanding that, for some individuals, symptoms may yet resolve on their own.

Detecting and treating PTSD early can decrease its deleterious effects on health and cut down on years of functional impairment.1 Even decades after an initial traumatic event, PTSD treatments can be effective.8 Children may experience functional impairment without meeting full criteria for PTSD, and can also benefit from treatment.7

INTEGRATING EXPOSURE AND COGNITIVE THERAPIES IS KEY

Offer any patient who meets criteria for PTSD a referral for exposure therapy and trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy (TF-CBT), the first-line treatments for PTSD.1,4,8,24,25

Exposure therapies for PTSD are supported by strong evidence and help patients to become desensitized to distressful memories through gradual, repeated exposures in a relaxed or safe space.8,26

Cognitive methods, such as cognitive processing therapy, cognitive behavioral therapy, and cognitive reprocessing have moderate strength of evidence, and may be combined with exposure therapy.26 Cognitive therapies help patients change thoughts, beliefs, and behaviors that contribute to PTSD symptoms.8,26

Exposure and TF-CBT have the most empirical evidence for child, adolescent, and adult PTSD, and are effective for the range of PTSD symptoms,4,8,25 including avoidance—a fundamental component of PTSD that drives other PTSD symptoms27—comorbid depression, and other emotions associated with trauma (eg, shame, guilt, and anger).8,25 Family involvement is recommended for children and adolescents.4

For patients with comorbid substance abuse, offer integrated PTSD/substance abuse treatment, which is more effective than isolated treatment of each.4 Relaxation training can be helpful as an adjunct to TF-CBT, but is not sufficient as a stand-alone treatment.13 Other psychotherapies, such as supportive, psychodynamic, systemic, and hypnotherapy, have not proved effective.14

Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR), a much publicized but controversial treatment, integrates components of exposure and cognitive therapies with therapist-directed eye movements.28-30 Patients imagine their trauma while the therapist directs their eye movements, which is thought to provide exposure to trauma images and memories, thereby reducing symptoms. EMDR has been found to reduce PTSD symptoms with a low to moderate strength-of-evidence rating.26 However, it has not proved more effective than other exposure and cognitive therapies, and its unique component (eg, eye movements) has not added any effect to outcomes.28-31

Other newer therapies, such as Acceptance and Commitment Therapy7,24,27 and online and computer-assisted treatments, are being evaluated.14

Medications take on an adjunct role to therapy

Drug treatment of PTSD has not been effective in children or adolescents.4,8 In adults, medications have helped relieve some symptoms of PTSD. However, given their low effect sizes, medications are not recommended as first-line treatments over exposure and TF-CBT. Their usefulness lies chiefly in an adjunct role to exposure and cognitive therapies or for patients who refuse psychotherapy.4,8,25

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors such as fluoxetine, paroxetine, and sertraline, have been effective for such PTSD symptoms as intrusive thoughts, negative or irritable mood, anxiety, restlessness, attention difficulties, and hyperarousal.1,8

While benzodiazepines have been used to control anxiety, hyperarousal, and insomnia, they have not been effective for most other PTSD symptoms, including avoidance, re-experiencing, and cognitive symptoms. Furthermore, they are not recommended given their augmentative effect on other related symptoms and associated conditions (eg, dissociation, disinhibition, substance abuse) and possible interference with desensitization that occurs in exposure therapy.1,5

If a patient has significant insomnia and PTSD-related nightmares, consider starting prazosin at 1 mg/d and titrating up to an effective dose, which typically ranges from 5 to 20 mg per day.1,5 Additionally, trazodone or antihistamines may be used to enhance sleep.1

COORDINATION OF CARE

Upon identifying PTSD and offering treatment, introduce the patient to a mental health provider as part of the referral process, which strongly encourages patient engagement in treatment.14 Collaborate with the psychotherapist throughout treatment to facilitate a biopsychosocial approach to the patient’s care, and coordinate the monitoring and treatment of any comorbid physical conditions.

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration has proposed a framework for multisystem Trauma-Informed Care (TIC), in which the primary care physician has many roles, including:12,20

- recording or communicating sensitive private information to other providers through the electronic medical record in a manner that does not interfere with a patient’s development of trust or lead to exposure and retraumatization,

- performing invasive physical exams in a sensitive and patient-centered manner, and

- using support and shared decision-making in clinical encounters.

Physicians can also connect patients with PTSD to programs or groups that aid in developing resilience, such as physical exercise classes, social support networks, and community involvement opportunities.4

CASE

The physician referred Mr. W to an onsite psychologist. At a subsequent clinic visit in which he was seen by a different primary care physician, Mr. W expressed new concerns about shoulder pain and changes in a mole. During this visit, Mr. W was asked whether he had followed up on the earlier referral for counseling. He replied that he had attended an intake appointment with the psychologist, but that he had not wanted to talk about what had happened to him and therefore avoided future appointments.*

He remained concerned that he might have an STD, but declined medication for PTSD because he felt he was “moving on” with his life.

*Author’s note: Getting patients to open up about their trauma exposure can be difficult. If the patient isn’t ready, simply bringing up the experience can trigger avoidance. It’s often helpful to encourage patients to first develop a relationship with their therapist, then later discuss the details of their trauma when they are ready. This encourages patients to engage in the counseling process.

CORRESPONDENCE

Adrienne A. Williams, PhD, Department of Family Medicine, University of Illinois at Chicago College of Medicine, 1919 W Taylor Street, MC663, Chicago, IL 60612; awms@uic.edu.

THE CASE

DeSean W,* a 47-year-old man, returned to his primary care clinic with a new complaint of epigastric burning that had been bothering him for the past 4 months. He had tried several over-the-counter remedies, which provided no relief. He also remained concerned—despite assurances to the contrary at previous clinic visits—that he had contracted a sexually-transmitted disease (STD) after going to a bar one night 4 to 5 months ago. At 2 other clinic visits since that time, STD test results were negative. At this current visit, symptoms and details of sexual history were unchanged since the last visit, with the exception of the epigastric pain.

When asked if he thought he had contracted an STD through a sexual encounter the night he went to the bar, he emphatically said he would not cheat on his wife. Surprisingly, given his concern, he avoided further discussion on modes of contracting an STD.

The physician prescribed ranitidine 150 mg bid for the epigastric burning and explained, once more, the significance of the STD test results. However, he also decided to further examine Mr. W’s concern about STDs and the night he may have contracted one.

HOW WOULD YOU PROCEED WITH THIS PATIENT?

*The patient’s name has been changed to protect his privacy.

SCOPE OF THE PROBLEM

Despite being as common as asthma, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) often remains undiagnosed and untreated in primary care.1 In brief, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) defines PTSD as persistent and long-term changes in thoughts or mood following actual or threatened exposure to death, serious injury, or sexual assault that leads to re-experiencing, functional impairment, physiologic stress reactions, and avoidance of thoughts or situations associated with the original trauma.2 More than one in 10 women and one in 20 men experience PTSD in their lifetime.2,3 Population-based studies have not yet determined the prevalence among children.3 Almost 40% of US adults report having experienced a trauma before age 13, and about one-third of these go on to develop PTSD.4

Individuals with PTSD have higher rates of somatic complaints, overall medical utilization, prescription use, physical and social disability, attempted suicide, and all-cause mortality.3,5-7 PTSD is associated with increased risk for cardiac, gastrointestinal, metabolic, and immunologic illnesses, other psychiatric illnesses, risky health behaviors, and decreased medical adherence.4,6 Additionally, prevention and treatment efforts for STDs and obesity are less effective among those with trauma histories.4 Thus, detection and treatment of PTSD improves the likelihood of successfully treating other health concerns.

THE ESSENTIALS OF A PTSD DIAGNOSIS

DSM-5 diagnosis of PTSD requires the experience of a trauma and resultant symptoms from each of 4 symptom-clusters:2

- one or more re-experiencing symptoms (eg, intrusive memories or recurrent distressing dreams, psychological distress or physiologic reactions to reminders of the trauma)

- one or more avoidance symptoms (eg, avoidance of trauma memories or of people and places that trigger a reminder of the trauma)

- two or more changes in thoughts or mood (eg, negative beliefs about self or others, social detachment, anhedonia)

- two or more changes in arousal activity (eg, sleep problems, hypervigilance, inability to concentrate).

Since many people experiencing traumas do not develop PTSD,5,8 symptoms must last at least one month to meet the criteria for diagnosis.2 Sexual trauma, experiencing multiple traumas, and lack of social support increase the risk that an individual will develop PTSD.9-11 Notably, symptom onset will be delayed 6 months or more in some individuals,2,8 making it more difficult for those patients and clinicians to connect symptoms to the trauma.12

Differential diagnosis

PTSD must be differentiated from other mental health conditions with overlapping symptoms (TABLE 12,8,13), but it may also be comorbid with one or more of these other conditions. When patients with PTSD do report mental health symptoms, providers often focus on the depressive symptoms that overlap with PTSD, and on substance use, which often accompanies PTSD, leaving PTSD undetected.9

Given that depressed/irritable mood, decreased participation in pleasurable activities, negative views of the world, attention difficulties, sleep difficulties, feelings of guilt, and agitation/restlessness are symptoms of both depression and PTSD,2 it is particularly important to screen patients with depressive symptoms for trauma history.

Why PTSD is often missed

Due to the impact of PTSD on overall health, the rates of PTSD in primary care clinics may be higher than in the general population.14 Thus, primary care clinicians are likely seeing PTSD more often than they realize. In fact, a systematic review showed that clinicians detected 0% to 52% of their patients with PTSD, missing at least half of all PTSD diagnoses.9

Detecting PTSD can be challenging for several reasons. Symptoms can span the emotional, social, physical, and behavioral aspects of an individual’s life, so patients and clinicians alike may regard symptoms as unrelated to PTSD.8 Primary symptom presentation may vary, with some people reporting anxiety symptoms, others mostly depressive symptoms, and others arousal, dissociative, or—as in our patient’s case—somatic symptoms.2 In affected children, parents may report emotional or behavioral problems without mentioning the trauma.2 Additionally, for traumas that were not a single event, such as long-term child abuse, patients may have difficulty identifying symptom onset.2

CASE

The physician screened Mr. W for trauma exposure as part of the differential. Mr. W revealed that he had blacked out at the bar, despite drinking only moderately, and that he awoke with anal pain. He believed he had been drugged and sexually assaulted. Further screening for PTSD symptoms related to this event confirmed multiple associated symptoms. He acknowledged that his epigastric pain had started soon after the trauma and, after further discussion, began to link his stomach pain and other new symptoms revealed by the PTSD screen (hypervigilance, avoidance, change in mood) to the trauma.

As happened in this case, most PTSD patients present with somatic complaints rather than reporting a traumatic experience and having associated effects. This in turn usually leads clinicians to consider only non-PTSD diagnoses.6,9,15 Core avoidance symptoms are a major reason for such a presentation in PTSD patients.14 Patients avoid thoughts, feelings, and conversations that remind them of the trauma.13 As a result, they are less likely to voluntarily report trauma. They avoid thinking about how their current symptoms may be associated with their trauma and are reluctant to talk about their trauma with clinicians.5,9,8,12

Another barrier to diagnosis is a belief that PTSD is primarily experienced by combat veterans1 (TABLE 22,4-6,8,9,12,14-18). While PTSD is detected more often among veterans due to regular screening through the Department of Veterans Affairs,14 the vast majority of PTSD cases are related to civilian traumas such as sexual assault, child abuse, and car accidents.5,9 In fact, the estimated

SCREENING: WHAT TO LOOK FOR

Since individuals with PTSD mainly seek treatment for associated physical symptoms,14 primary care is particularly important for identification of PTSD and treatment access. The US Preventative Services Task Force does not yet have any recommendations for screening for PTSD. The American Psychiatric Association recommends that a trauma history be included in all initial psychiatric evaluations of adults.19 Screens can target high-risk populations and can be repeated across the lifespan,9 as traumas can occur at any age and symptoms may not emerge until years after the trauma.2,4 Factors in a patient’s history associated with high risk of PTSD include the following:

- known trauma exposure (eg, treatment at the emergency department following motor vehicle collision, natural disaster, assault),6

- frequent medical visits or unexplained physical symptoms,5,8

- family members who are trauma victims,8

- involvement in juvenile justice system,4,12

- sensitive or invasive exams (eg, pelvic exams) that trigger symptoms or contribute to retraumatization,12,20 and

- any medical condition (eg, hypertension, chronic pain, sleep disorder), self-destructive behavior (eg, drug or alcohol abuse, low impulse control), or social/occupational issues (eg, unemployment, social isolation, fighting) with a known link to PTSD.2,4,6,8

The first step in screening. Given a patient’s reported symptoms, assess for trauma exposure to determine whether PTSD should be included in the differential diagnosis. Overlooking PTSD as a possible source of symptoms can result in misattributing them to other causes.4,8 Listing common traumas, or using a standardized list such as the Life Events Checklist, can help identify patients with trauma exposure.8,21 However, do not make the patient provide details of the traumatic event(s), as that can exacerbate symptoms if PTSD is present.6 It is sufficient to know the category of the trauma (eg, sexual assault) without making the patient describe who was involved and what happened.6

The second step in screening. If a patient reveals trauma exposure, consider using an instrument such as the Primary Care PTSD Screen (PC-PTSD) or the PTSD Checklist, both available online, to screen for PTSD symptoms related to the identified trauma.6,9,21-23 Since these measures screen for symptoms but do not ask about trauma exposure, false positives can occur if a trauma is not first identified (such as through the Life Events Checklist) due to symptom overlap with other conditions (TABLE 12,8,13).21

Treatment is effective, even decades after a traumatic event

Provide anyone who has been traumatized with information about common after effects, symptoms of PTSD, and available treatments.8 Keep in mind that initial symptom severity after trauma exposure does not correlate with long-term symptoms,8 and about half of adults will recover without treatment within 3 months.1,2,5 The first month of symptoms may be addressed with patient education and watchful waiting. But if symptoms don’t subside after a month, consider offering treatment1 with the understanding that, for some individuals, symptoms may yet resolve on their own.

Detecting and treating PTSD early can decrease its deleterious effects on health and cut down on years of functional impairment.1 Even decades after an initial traumatic event, PTSD treatments can be effective.8 Children may experience functional impairment without meeting full criteria for PTSD, and can also benefit from treatment.7

INTEGRATING EXPOSURE AND COGNITIVE THERAPIES IS KEY

Offer any patient who meets criteria for PTSD a referral for exposure therapy and trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy (TF-CBT), the first-line treatments for PTSD.1,4,8,24,25

Exposure therapies for PTSD are supported by strong evidence and help patients to become desensitized to distressful memories through gradual, repeated exposures in a relaxed or safe space.8,26

Cognitive methods, such as cognitive processing therapy, cognitive behavioral therapy, and cognitive reprocessing have moderate strength of evidence, and may be combined with exposure therapy.26 Cognitive therapies help patients change thoughts, beliefs, and behaviors that contribute to PTSD symptoms.8,26

Exposure and TF-CBT have the most empirical evidence for child, adolescent, and adult PTSD, and are effective for the range of PTSD symptoms,4,8,25 including avoidance—a fundamental component of PTSD that drives other PTSD symptoms27—comorbid depression, and other emotions associated with trauma (eg, shame, guilt, and anger).8,25 Family involvement is recommended for children and adolescents.4

For patients with comorbid substance abuse, offer integrated PTSD/substance abuse treatment, which is more effective than isolated treatment of each.4 Relaxation training can be helpful as an adjunct to TF-CBT, but is not sufficient as a stand-alone treatment.13 Other psychotherapies, such as supportive, psychodynamic, systemic, and hypnotherapy, have not proved effective.14

Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR), a much publicized but controversial treatment, integrates components of exposure and cognitive therapies with therapist-directed eye movements.28-30 Patients imagine their trauma while the therapist directs their eye movements, which is thought to provide exposure to trauma images and memories, thereby reducing symptoms. EMDR has been found to reduce PTSD symptoms with a low to moderate strength-of-evidence rating.26 However, it has not proved more effective than other exposure and cognitive therapies, and its unique component (eg, eye movements) has not added any effect to outcomes.28-31

Other newer therapies, such as Acceptance and Commitment Therapy7,24,27 and online and computer-assisted treatments, are being evaluated.14

Medications take on an adjunct role to therapy

Drug treatment of PTSD has not been effective in children or adolescents.4,8 In adults, medications have helped relieve some symptoms of PTSD. However, given their low effect sizes, medications are not recommended as first-line treatments over exposure and TF-CBT. Their usefulness lies chiefly in an adjunct role to exposure and cognitive therapies or for patients who refuse psychotherapy.4,8,25

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors such as fluoxetine, paroxetine, and sertraline, have been effective for such PTSD symptoms as intrusive thoughts, negative or irritable mood, anxiety, restlessness, attention difficulties, and hyperarousal.1,8

While benzodiazepines have been used to control anxiety, hyperarousal, and insomnia, they have not been effective for most other PTSD symptoms, including avoidance, re-experiencing, and cognitive symptoms. Furthermore, they are not recommended given their augmentative effect on other related symptoms and associated conditions (eg, dissociation, disinhibition, substance abuse) and possible interference with desensitization that occurs in exposure therapy.1,5

If a patient has significant insomnia and PTSD-related nightmares, consider starting prazosin at 1 mg/d and titrating up to an effective dose, which typically ranges from 5 to 20 mg per day.1,5 Additionally, trazodone or antihistamines may be used to enhance sleep.1

COORDINATION OF CARE

Upon identifying PTSD and offering treatment, introduce the patient to a mental health provider as part of the referral process, which strongly encourages patient engagement in treatment.14 Collaborate with the psychotherapist throughout treatment to facilitate a biopsychosocial approach to the patient’s care, and coordinate the monitoring and treatment of any comorbid physical conditions.

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration has proposed a framework for multisystem Trauma-Informed Care (TIC), in which the primary care physician has many roles, including:12,20

- recording or communicating sensitive private information to other providers through the electronic medical record in a manner that does not interfere with a patient’s development of trust or lead to exposure and retraumatization,

- performing invasive physical exams in a sensitive and patient-centered manner, and

- using support and shared decision-making in clinical encounters.

Physicians can also connect patients with PTSD to programs or groups that aid in developing resilience, such as physical exercise classes, social support networks, and community involvement opportunities.4

CASE

The physician referred Mr. W to an onsite psychologist. At a subsequent clinic visit in which he was seen by a different primary care physician, Mr. W expressed new concerns about shoulder pain and changes in a mole. During this visit, Mr. W was asked whether he had followed up on the earlier referral for counseling. He replied that he had attended an intake appointment with the psychologist, but that he had not wanted to talk about what had happened to him and therefore avoided future appointments.*

He remained concerned that he might have an STD, but declined medication for PTSD because he felt he was “moving on” with his life.

*Author’s note: Getting patients to open up about their trauma exposure can be difficult. If the patient isn’t ready, simply bringing up the experience can trigger avoidance. It’s often helpful to encourage patients to first develop a relationship with their therapist, then later discuss the details of their trauma when they are ready. This encourages patients to engage in the counseling process.

CORRESPONDENCE

Adrienne A. Williams, PhD, Department of Family Medicine, University of Illinois at Chicago College of Medicine, 1919 W Taylor Street, MC663, Chicago, IL 60612; awms@uic.edu.

1. Bobo WV, Warner CH, Warner CM. The management of post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in the primary care setting. South Med J. 2007;100:797-802.

2. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013.

3. Gradus JL. Epidemiology of PTSD. National Center for PTSD. Available at: http://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/PTSD-overview/epidemiological-facts-ptsd.asp. Updated 2017. Accessed August 16, 2017.

4. Gerson R, Rappaport N. Traumatic stress and posttraumatic stress disorder in youth: recent research findings on clinical impact, assessment, and treatment. J Adolesc Health. 2013;52:137-143.

5. Zohar J, Juven-Wetzler A, Myers V, et al. Post-traumatic stress disorder: facts and fiction. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2008;21:74-77.

6. Spoont MR, Williams JW Jr, Kehle-Forbes S, et al. Does this patient have posttraumatic stress disorder? Rational clinical examination systematic review. JAMA. 2015;314:501-510.

7. Woidneck MR, Morrison KL, Twohig MP. Acceptance and commitment therapy for the treatment of posttraumatic stress among adolescents. Behav Modif. 2014;38:451-476.

8. National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health (UK). Post-traumatic stress disorder: the management of PTSD in adults and children in primary and secondary care. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK56494. Accessed August 16, 2017.

9. Greene T, Neria Y, Gross R. Prevalence, detection and correlates of PTSD in the primary care setting: a systematic review. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2016;23:160-180.

10. Gavranidou M, Rosner R. The weaker sex? Gender and post-traumatic stress disorder. Depress Anxiety. 2003;17:130-139.

11. Brewin CR, Andrews B, Valentine JD. Meta-analysis of risk factors for posttraumatic stress disorder in trauma-exposed adults. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;68:748-766.

12. SAMHSA’s Trauma and Justice Strategic Initiative. SAMHSA’s concept of trauma and guidance for a trauma-informed approach. Available at: http://store.samhsa.gov/shin/content/SMA14-4884/SMA14-4884.pdf. Accessed September 13, 2017.

13. Mulick PS, Landes SJ, Kanter JW. Contextual behavior therapies in the treatment of PTSD: a review. Int J Behav Consult Ther. 2005;1:223-238.

14. Possemato K. The current state of intervention research for posttraumatic stress disorder within the primary care setting. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2011;18:268-280.

15. Forneris CA, Gartlehner G, Brownley KA, et al. Interventions to prevent post-traumatic stress disorder: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2013;44:635-650.

16. Trivedi RB, Post EP, Sun H, et al. Prevalence, comorbidity, and prognosis of mental health among US veterans. Am J Public Health. 2015;105:2564-2569.

17. United States Census Bureau. Facts for features: Veteran’s day 2016: Nov. 11. Available at: https://www.census.gov/newsroom/facts-for-features/2016/cb16-ff21.html. Accessed August 16, 2017.

18. United States Census Bureau. U.S. and World Population Clock. Available at: https://www.census.gov/popclock/. Accessed August 16, 2017.

19. American Psychiatric Association. Guidelines and implementation. In: Practice Guidelines for the Psychiatric Evaluation of Adults. 3rd ed. Arlington, Va: American Psychiatric Association; 2015:9-45.

20. Williams AA, Williams M. A guide to performing pelvic speculum exams: a patient-centered approach to reducing iatrogenic effects. Teach Learn Med. 2013;25:383-391.

21. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Life events checklist for DSM-5 (LEC-5). Available at: http://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/assessment/te-measures/life_events_checklist.asp. Accessed September 13, 2017.

22. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Primary care PTSD screen for DSM-5 (PC-PTSD). Available at: http://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/assessment/screens/pc-ptsd.asp. Accessed September 13, 2017.

23. Spoont M, Arbisi P, Fu S, et al. Screening for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) in Primary Care: A Systematic Review. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK126691/. Accessed Sept 13, 2017

24. Gallagher MW, Thompson-Hollands J, Bourgeois ML, et al. Cognitive behavioral treatments for adult posttraumatic stress disorder: current status and future directions. J Contemp Psychother. 2015;45:235-243.

25. Kar N. Cognitive behavioral therapy for the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder: a review. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2011;7:167-181.

26. Cusack K, Jonas DE, Forneris CA, et al. Psychological treatments for adults with posttraumatic stress disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2016;43:128-141.

27. Thompson BL, Luoma JB, LeJeune JT. Using acceptance and commitment therapy to guide exposure-based interventions for posttraumatic stress disorder. J Contemp Psychother. 2013;43:133-140.

28. Lohr JM, Hooke W, Gist R, et al. Novel and controversial treatments for trauma-related stress disorders. In: Lilienfeld SO, Lynn SJ, Lohr JM, eds. Science and Pseudoscience in Clinical Psychology. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2003:243-272.

29. Sikes C, Sikes V. EMDR: Why the controversy? Traumatol. 2003;9:169-182.

30. Davidson PR, Parker KCH. Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR): a meta-analysis. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2001;69:305-316.

31. Devilly GJ. Power therapies and possible threats to the science of psychology and psychiatry. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2005;39:437-445.

1. Bobo WV, Warner CH, Warner CM. The management of post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in the primary care setting. South Med J. 2007;100:797-802.

2. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013.

3. Gradus JL. Epidemiology of PTSD. National Center for PTSD. Available at: http://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/PTSD-overview/epidemiological-facts-ptsd.asp. Updated 2017. Accessed August 16, 2017.

4. Gerson R, Rappaport N. Traumatic stress and posttraumatic stress disorder in youth: recent research findings on clinical impact, assessment, and treatment. J Adolesc Health. 2013;52:137-143.

5. Zohar J, Juven-Wetzler A, Myers V, et al. Post-traumatic stress disorder: facts and fiction. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2008;21:74-77.

6. Spoont MR, Williams JW Jr, Kehle-Forbes S, et al. Does this patient have posttraumatic stress disorder? Rational clinical examination systematic review. JAMA. 2015;314:501-510.

7. Woidneck MR, Morrison KL, Twohig MP. Acceptance and commitment therapy for the treatment of posttraumatic stress among adolescents. Behav Modif. 2014;38:451-476.

8. National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health (UK). Post-traumatic stress disorder: the management of PTSD in adults and children in primary and secondary care. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK56494. Accessed August 16, 2017.

9. Greene T, Neria Y, Gross R. Prevalence, detection and correlates of PTSD in the primary care setting: a systematic review. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2016;23:160-180.

10. Gavranidou M, Rosner R. The weaker sex? Gender and post-traumatic stress disorder. Depress Anxiety. 2003;17:130-139.

11. Brewin CR, Andrews B, Valentine JD. Meta-analysis of risk factors for posttraumatic stress disorder in trauma-exposed adults. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;68:748-766.

12. SAMHSA’s Trauma and Justice Strategic Initiative. SAMHSA’s concept of trauma and guidance for a trauma-informed approach. Available at: http://store.samhsa.gov/shin/content/SMA14-4884/SMA14-4884.pdf. Accessed September 13, 2017.

13. Mulick PS, Landes SJ, Kanter JW. Contextual behavior therapies in the treatment of PTSD: a review. Int J Behav Consult Ther. 2005;1:223-238.

14. Possemato K. The current state of intervention research for posttraumatic stress disorder within the primary care setting. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2011;18:268-280.

15. Forneris CA, Gartlehner G, Brownley KA, et al. Interventions to prevent post-traumatic stress disorder: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2013;44:635-650.

16. Trivedi RB, Post EP, Sun H, et al. Prevalence, comorbidity, and prognosis of mental health among US veterans. Am J Public Health. 2015;105:2564-2569.

17. United States Census Bureau. Facts for features: Veteran’s day 2016: Nov. 11. Available at: https://www.census.gov/newsroom/facts-for-features/2016/cb16-ff21.html. Accessed August 16, 2017.

18. United States Census Bureau. U.S. and World Population Clock. Available at: https://www.census.gov/popclock/. Accessed August 16, 2017.

19. American Psychiatric Association. Guidelines and implementation. In: Practice Guidelines for the Psychiatric Evaluation of Adults. 3rd ed. Arlington, Va: American Psychiatric Association; 2015:9-45.

20. Williams AA, Williams M. A guide to performing pelvic speculum exams: a patient-centered approach to reducing iatrogenic effects. Teach Learn Med. 2013;25:383-391.

21. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Life events checklist for DSM-5 (LEC-5). Available at: http://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/assessment/te-measures/life_events_checklist.asp. Accessed September 13, 2017.

22. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Primary care PTSD screen for DSM-5 (PC-PTSD). Available at: http://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/assessment/screens/pc-ptsd.asp. Accessed September 13, 2017.

23. Spoont M, Arbisi P, Fu S, et al. Screening for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) in Primary Care: A Systematic Review. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK126691/. Accessed Sept 13, 2017

24. Gallagher MW, Thompson-Hollands J, Bourgeois ML, et al. Cognitive behavioral treatments for adult posttraumatic stress disorder: current status and future directions. J Contemp Psychother. 2015;45:235-243.

25. Kar N. Cognitive behavioral therapy for the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder: a review. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2011;7:167-181.

26. Cusack K, Jonas DE, Forneris CA, et al. Psychological treatments for adults with posttraumatic stress disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2016;43:128-141.

27. Thompson BL, Luoma JB, LeJeune JT. Using acceptance and commitment therapy to guide exposure-based interventions for posttraumatic stress disorder. J Contemp Psychother. 2013;43:133-140.

28. Lohr JM, Hooke W, Gist R, et al. Novel and controversial treatments for trauma-related stress disorders. In: Lilienfeld SO, Lynn SJ, Lohr JM, eds. Science and Pseudoscience in Clinical Psychology. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2003:243-272.

29. Sikes C, Sikes V. EMDR: Why the controversy? Traumatol. 2003;9:169-182.

30. Davidson PR, Parker KCH. Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR): a meta-analysis. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2001;69:305-316.

31. Devilly GJ. Power therapies and possible threats to the science of psychology and psychiatry. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2005;39:437-445.