User login

For MD-IQ only

Hepatitis C: Essential Treatment Considerations

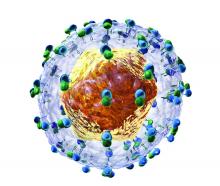

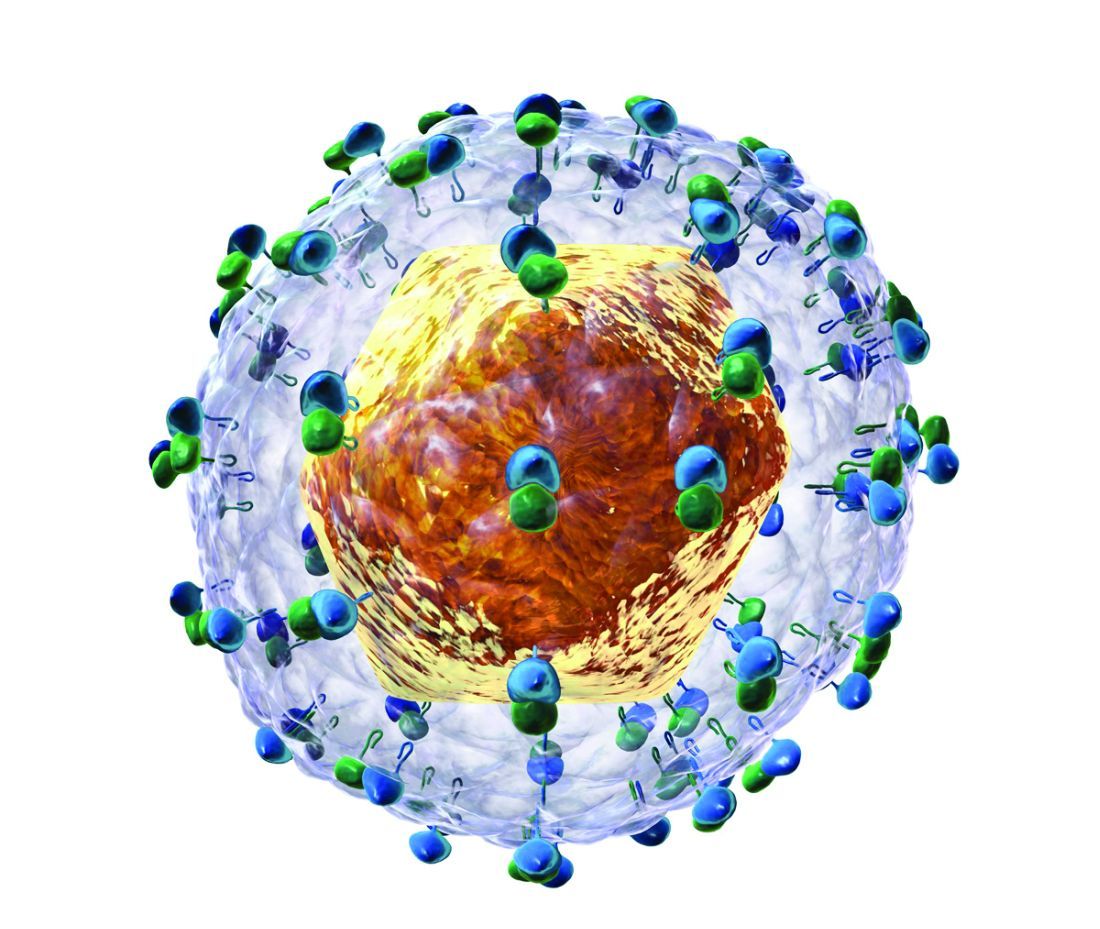

Until recently, chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) treatment had poor efficacy and was provided only by specialists such as hepatologists and gastroenterologists. However, the introduction of safe, effective direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) has revolutionized HCV treatment.

One pivotal transformation has been the expansion of treatment to nonspecialist physicians. Nevertheless, various factors must be considered when initiating treatment for HCV.

Dr Elizabeth Verna, director of hepatology research at Columbia University in New York City, examines the essential treatment considerations for chronic HCV in treatment-naive patients.

First, she outlines recommended first-line therapies and the simplified HCV treatment algorithm recently issued by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the Infectious Diseases Society of America. She then discusses patient-specific factors, such as cirrhosis, co-infections, age, and pregnancy, that can create treatment challenges and change the algorithm.

In closing, she talks about changes in HCV screening recommendations and how diagnosis and treatment of this infectious disease largely rest in the hands of general practitioners who are the first line of defense in controlling HCV spread.

--

Associate Professor of Medicine, Director of Hepatology Research, Associate Physician, Department of Medicine, Columbia University, New York, NY

Elizabeth Verna, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Received research grant from: Salix

Until recently, chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) treatment had poor efficacy and was provided only by specialists such as hepatologists and gastroenterologists. However, the introduction of safe, effective direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) has revolutionized HCV treatment.

One pivotal transformation has been the expansion of treatment to nonspecialist physicians. Nevertheless, various factors must be considered when initiating treatment for HCV.

Dr Elizabeth Verna, director of hepatology research at Columbia University in New York City, examines the essential treatment considerations for chronic HCV in treatment-naive patients.

First, she outlines recommended first-line therapies and the simplified HCV treatment algorithm recently issued by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the Infectious Diseases Society of America. She then discusses patient-specific factors, such as cirrhosis, co-infections, age, and pregnancy, that can create treatment challenges and change the algorithm.

In closing, she talks about changes in HCV screening recommendations and how diagnosis and treatment of this infectious disease largely rest in the hands of general practitioners who are the first line of defense in controlling HCV spread.

--

Associate Professor of Medicine, Director of Hepatology Research, Associate Physician, Department of Medicine, Columbia University, New York, NY

Elizabeth Verna, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Received research grant from: Salix

Until recently, chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) treatment had poor efficacy and was provided only by specialists such as hepatologists and gastroenterologists. However, the introduction of safe, effective direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) has revolutionized HCV treatment.

One pivotal transformation has been the expansion of treatment to nonspecialist physicians. Nevertheless, various factors must be considered when initiating treatment for HCV.

Dr Elizabeth Verna, director of hepatology research at Columbia University in New York City, examines the essential treatment considerations for chronic HCV in treatment-naive patients.

First, she outlines recommended first-line therapies and the simplified HCV treatment algorithm recently issued by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the Infectious Diseases Society of America. She then discusses patient-specific factors, such as cirrhosis, co-infections, age, and pregnancy, that can create treatment challenges and change the algorithm.

In closing, she talks about changes in HCV screening recommendations and how diagnosis and treatment of this infectious disease largely rest in the hands of general practitioners who are the first line of defense in controlling HCV spread.

--

Associate Professor of Medicine, Director of Hepatology Research, Associate Physician, Department of Medicine, Columbia University, New York, NY

Elizabeth Verna, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Received research grant from: Salix

Improving access to liver disease screening in at-risk and underserved communities

Dr. Ponni V. Perumalswami is an Associate Professor of Internal Medicine in the Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology at the University of Michigan; Ann Arbor VA Healthcare System. Dr. Perumalswami's areas of clinical interest include cirrhosis, acute/chronic liver diseases and liver transplantation. Her research program focuses on community outreach for hepatitis B and C screening and linking patients to care.

Q: For patients with liver disease who live in underserved and vulnerable communities, what barriers to that care are more prominent or at the primary systemic-level?

Dr. Perumalswami: I think a major barrier has been our approach to thinking about these barriers, so I'm glad you are asking this question in terms of what the systemic-level barriers are rather than, for example, patient-level barriers. I'll use viral hepatitis as an example in terms of liver-disease care. I think for a very long time we've placed an unfair, onus on patients, leaving them to find their own care and to navigate existing system-level barriers such as language proficiency, health literacy, lack of insurance, and long distances to access specialists by themselves. This “do-it-yourself” approach has created a systemic-level barrier to finding specialists, and it remains a major problem. We would do a better job of improving access to care by re-thinking all barriers to care as system-and provider-level barriers rather than patient-level barriers because it is often the case that solutions that address systems barriers can address these issues.

Many specialists, like myself, are often geographically clustered at tertiary care and urban academic centers but the reality is that patients who are at risk for living with liver disease live all over, including rural areas, where fewer specialists practice. But advancements in treatments of certain liver diseases, such as hepatitis C virus (HCV), have made it possible for frontline community providers to treat patients. Expanding these patients' treatment options, in large part, is dependent on payer policy changes to allow treatment by non-specialists, reducing the cost of treatment and giving frontline workers the support they need so that they are more confident to offer treatment while differentiating the occasional patient who may need referral to a specialist.

Cost is also a systemic-level barrier for our underserved patients with liver disease and comes in many forms. Barriers related to cost include lack or type of insurance, traveling distances which also entails a cost for time (i.e. loss of wages, caregiver support), and cost of treatments. There are certain restrictions on HCV treatments that designate who can administer them and at what point in disease progression the therapy be introduced. These restrictions have been arbitrarily set by payers for treatments like direct-acting antivirals (DAA) and unfortunately dictate "when they can be obtained" and "who can prescribe them." Instead, we should spend time and effort to determine how we can have more providers practicing in different spaces, who might be equipped and motivated to provide treatment, and do it safely and easily.

Another barrier I will mention is the lack of integrated care for patients with certain liver diseases within healthcare systems. Notable examples include integrated care for those with alcohol-associated liver disease and viral hepatitis, who often have co-occurring mental health issues and substance use, addiction, or opioid use disorders. We need to think through how we can get integrated treatment and care to these patients, instead of making them come to us as individual specialists. By integrating medical care into behavioral health practices or other treatment settings, and perhaps by considering nontraditional treatment modalities, we can overcome barriers to care that are all too often siloed.

The last thing that I will mention with regards to patient-level barriers is that liver diseases and their care by providers has been very stigmatized, particularly for patients with underlying mental health and/or addiction disorders. These patients do not always feel comfortable coming to see clinicians in their practices so we must recognize that our offices may be stigmatized places for some patients with liver disease. Because of this, it is vital to think about how we can integrate care into trusted spaces for patient populations who might be at risk or are living with liver disease.

Q: What aspects of these barriers have you focused on to improve screening and links to care in communities at risk?

Dr. Perumalswami: A lot of my work is focused on patients in populations who are at risk for viral hepatitis and on screening them, educating them, and linking them to care in their communities. The challenge in successfully treating patients with a liver disease is that most liver diseases remain silent until they've progressed to a very advanced stage. Certain populations are at a higher risk for contracting these diseases compared to others. For example, with hepatitis B virus, we know that foreign-born populations have a higher infection rate, and how and when they seek care might be very different in terms of being symptom-driven versus preventive care as a result of cultural factors around health seeking behaviors. Our team has attempted to take a more proactive approach; first, to understand who might be at risk, and second, to try to bring screening to trusted places where patients can easily access care. We have found this proactive approach to be very successful in terms of identifying people who are not yet diagnosed with liver disease and then linking them into care.

The first step is knowing which populations you want to target with respect to individual types of liver disease, then working with community partners to bring screening out into the community. Obviously, the challenging part is getting people linked into care. As stated previously, many liver diseases in their earlier stages stay silent and manifest without symptoms, thus why it is vital to offer at-risk patients testing or screening.

The next step is to raise patient awareness and provide education as to why it is important to seek care; to get a thorough evaluation in terms of the extent of the liver disease and how to best manage and treat it, long term. For example, we have found that care coordination works very well with patients living with HCV. For patients with hepatitis B, we have found that culturally informed patient navigation services are very helpful, so we work with peers in the community who speak the same language and who come from the same communities as the patients identified as at-risk. This combined strategy of testing and then linking to care has been very successful.

I will say an important part of the care-coordination piece is addressing the competing priorities that patients have in their lives. For example, if they need housing, we refer them to housing services; if they have food insecurities, we try to address the need. Once you address their basic determinants of health, you have established a basis for trust while helping patients contend with important competing priorities. This way, your team has enabled potential patients to prioritize and engage in health care.

Q: How have you integrated HCV treatment into harm reduction and opioid use disorder settings?

Dr. Perumalswami: I am fortunate to be involved with a program here in Michigan whose goal is to increase HCV treatment through an open access, HCV consultation program through the Michigan Opioid Collaborative. The premise is to find motivated, interested providers who want to learn how to offer HCV treatment to patients in their communities; the majority of these providers are in rural parts of Michigan. In this setting, we are working with frontline medical personnel in the community, many of whom are either addiction providers or are offering opioid use disorder treatment, and who are also seeing HCV patients. We have set up an open-case consulting program where providers can submit cases for review with guidance from hepatologists. Attendance is optional and we meet for an hour, every other week and we talk through cases in more detail as a group. The result is that the providers have reported that they feel less isolated doing this as a team, having a place to discuss cases and work through practical challenges that can arise with this patient base. While HCV treatment advances have made great strides, many providers want reassurance or guidance in terms how to implement these programs so as a group, we walk through a few cases, demonstrate how to check for drug-drug interactions and how to perform fibrosis assessments. After these providers go through this training, they become more comfortable giving treatment on their own.

The second project, which I have also been fortunate to be involved in, is led by my colleague Dr. Jeffrey Weiss at Mount Sinai Hospital and is located at a syringe exchange program in a Brooklyn, New York. Here, patients attend receive in-person and/or telemedicine-based HCV treatment, which is a new model of care for us. While it has produced a different set of challenges in terms of engaging and bringing treatment to patients in a new space, it has been a great way to meet our objectives of helping patients to be treated where they are comfortable accessing care and services.

Q: Has the pandemic created any new challenges in treating at risk or special populations?

Dr. Perumalswami: The pandemic presented many new challenges. The primary impact that COVID-19 has had on our patients has been with the disruption in care; particularly for those patients who already found it challenging to seek and receive care. For patients who benefitted from following a routine, other pandemic-related challenges were the restrictions placed on our practices, and the reduced hours patients had to contend with access services and treatments at places such as syringe exchange programs or methadone programs.

Many of our patients have expressed feeling isolated as they are not able to get the same type of support that they were previously receiving. The decreases in viral hepatitis outreach, in screening in the community, and in practices resulted in a decrease in diagnosis and treatment.

We have also heard numerous discussions with regards to better reimbursements for phone call and telehealth sessions, but we must recognize that those things are not accessible to all patients. Many of our most vulnerable populations, do not have working phones, stable housing, or smart devices to access telehealth, so while there have been technological advances that can provide access to care and better reimbursement procedures, there are still many limitations that our patients are facing.

(AGA applauds researchers who are working to raise our awareness of health disparities in digestive diseases. AGA is committed to addressing this important societal issue head on. Learn more about AGA’s commitment through the AGA Equity Project).

Dr. Ponni V. Perumalswami is an Associate Professor of Internal Medicine in the Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology at the University of Michigan; Ann Arbor VA Healthcare System. Dr. Perumalswami's areas of clinical interest include cirrhosis, acute/chronic liver diseases and liver transplantation. Her research program focuses on community outreach for hepatitis B and C screening and linking patients to care.

Q: For patients with liver disease who live in underserved and vulnerable communities, what barriers to that care are more prominent or at the primary systemic-level?

Dr. Perumalswami: I think a major barrier has been our approach to thinking about these barriers, so I'm glad you are asking this question in terms of what the systemic-level barriers are rather than, for example, patient-level barriers. I'll use viral hepatitis as an example in terms of liver-disease care. I think for a very long time we've placed an unfair, onus on patients, leaving them to find their own care and to navigate existing system-level barriers such as language proficiency, health literacy, lack of insurance, and long distances to access specialists by themselves. This “do-it-yourself” approach has created a systemic-level barrier to finding specialists, and it remains a major problem. We would do a better job of improving access to care by re-thinking all barriers to care as system-and provider-level barriers rather than patient-level barriers because it is often the case that solutions that address systems barriers can address these issues.

Many specialists, like myself, are often geographically clustered at tertiary care and urban academic centers but the reality is that patients who are at risk for living with liver disease live all over, including rural areas, where fewer specialists practice. But advancements in treatments of certain liver diseases, such as hepatitis C virus (HCV), have made it possible for frontline community providers to treat patients. Expanding these patients' treatment options, in large part, is dependent on payer policy changes to allow treatment by non-specialists, reducing the cost of treatment and giving frontline workers the support they need so that they are more confident to offer treatment while differentiating the occasional patient who may need referral to a specialist.

Cost is also a systemic-level barrier for our underserved patients with liver disease and comes in many forms. Barriers related to cost include lack or type of insurance, traveling distances which also entails a cost for time (i.e. loss of wages, caregiver support), and cost of treatments. There are certain restrictions on HCV treatments that designate who can administer them and at what point in disease progression the therapy be introduced. These restrictions have been arbitrarily set by payers for treatments like direct-acting antivirals (DAA) and unfortunately dictate "when they can be obtained" and "who can prescribe them." Instead, we should spend time and effort to determine how we can have more providers practicing in different spaces, who might be equipped and motivated to provide treatment, and do it safely and easily.

Another barrier I will mention is the lack of integrated care for patients with certain liver diseases within healthcare systems. Notable examples include integrated care for those with alcohol-associated liver disease and viral hepatitis, who often have co-occurring mental health issues and substance use, addiction, or opioid use disorders. We need to think through how we can get integrated treatment and care to these patients, instead of making them come to us as individual specialists. By integrating medical care into behavioral health practices or other treatment settings, and perhaps by considering nontraditional treatment modalities, we can overcome barriers to care that are all too often siloed.

The last thing that I will mention with regards to patient-level barriers is that liver diseases and their care by providers has been very stigmatized, particularly for patients with underlying mental health and/or addiction disorders. These patients do not always feel comfortable coming to see clinicians in their practices so we must recognize that our offices may be stigmatized places for some patients with liver disease. Because of this, it is vital to think about how we can integrate care into trusted spaces for patient populations who might be at risk or are living with liver disease.

Q: What aspects of these barriers have you focused on to improve screening and links to care in communities at risk?

Dr. Perumalswami: A lot of my work is focused on patients in populations who are at risk for viral hepatitis and on screening them, educating them, and linking them to care in their communities. The challenge in successfully treating patients with a liver disease is that most liver diseases remain silent until they've progressed to a very advanced stage. Certain populations are at a higher risk for contracting these diseases compared to others. For example, with hepatitis B virus, we know that foreign-born populations have a higher infection rate, and how and when they seek care might be very different in terms of being symptom-driven versus preventive care as a result of cultural factors around health seeking behaviors. Our team has attempted to take a more proactive approach; first, to understand who might be at risk, and second, to try to bring screening to trusted places where patients can easily access care. We have found this proactive approach to be very successful in terms of identifying people who are not yet diagnosed with liver disease and then linking them into care.

The first step is knowing which populations you want to target with respect to individual types of liver disease, then working with community partners to bring screening out into the community. Obviously, the challenging part is getting people linked into care. As stated previously, many liver diseases in their earlier stages stay silent and manifest without symptoms, thus why it is vital to offer at-risk patients testing or screening.

The next step is to raise patient awareness and provide education as to why it is important to seek care; to get a thorough evaluation in terms of the extent of the liver disease and how to best manage and treat it, long term. For example, we have found that care coordination works very well with patients living with HCV. For patients with hepatitis B, we have found that culturally informed patient navigation services are very helpful, so we work with peers in the community who speak the same language and who come from the same communities as the patients identified as at-risk. This combined strategy of testing and then linking to care has been very successful.

I will say an important part of the care-coordination piece is addressing the competing priorities that patients have in their lives. For example, if they need housing, we refer them to housing services; if they have food insecurities, we try to address the need. Once you address their basic determinants of health, you have established a basis for trust while helping patients contend with important competing priorities. This way, your team has enabled potential patients to prioritize and engage in health care.

Q: How have you integrated HCV treatment into harm reduction and opioid use disorder settings?

Dr. Perumalswami: I am fortunate to be involved with a program here in Michigan whose goal is to increase HCV treatment through an open access, HCV consultation program through the Michigan Opioid Collaborative. The premise is to find motivated, interested providers who want to learn how to offer HCV treatment to patients in their communities; the majority of these providers are in rural parts of Michigan. In this setting, we are working with frontline medical personnel in the community, many of whom are either addiction providers or are offering opioid use disorder treatment, and who are also seeing HCV patients. We have set up an open-case consulting program where providers can submit cases for review with guidance from hepatologists. Attendance is optional and we meet for an hour, every other week and we talk through cases in more detail as a group. The result is that the providers have reported that they feel less isolated doing this as a team, having a place to discuss cases and work through practical challenges that can arise with this patient base. While HCV treatment advances have made great strides, many providers want reassurance or guidance in terms how to implement these programs so as a group, we walk through a few cases, demonstrate how to check for drug-drug interactions and how to perform fibrosis assessments. After these providers go through this training, they become more comfortable giving treatment on their own.

The second project, which I have also been fortunate to be involved in, is led by my colleague Dr. Jeffrey Weiss at Mount Sinai Hospital and is located at a syringe exchange program in a Brooklyn, New York. Here, patients attend receive in-person and/or telemedicine-based HCV treatment, which is a new model of care for us. While it has produced a different set of challenges in terms of engaging and bringing treatment to patients in a new space, it has been a great way to meet our objectives of helping patients to be treated where they are comfortable accessing care and services.

Q: Has the pandemic created any new challenges in treating at risk or special populations?

Dr. Perumalswami: The pandemic presented many new challenges. The primary impact that COVID-19 has had on our patients has been with the disruption in care; particularly for those patients who already found it challenging to seek and receive care. For patients who benefitted from following a routine, other pandemic-related challenges were the restrictions placed on our practices, and the reduced hours patients had to contend with access services and treatments at places such as syringe exchange programs or methadone programs.

Many of our patients have expressed feeling isolated as they are not able to get the same type of support that they were previously receiving. The decreases in viral hepatitis outreach, in screening in the community, and in practices resulted in a decrease in diagnosis and treatment.

We have also heard numerous discussions with regards to better reimbursements for phone call and telehealth sessions, but we must recognize that those things are not accessible to all patients. Many of our most vulnerable populations, do not have working phones, stable housing, or smart devices to access telehealth, so while there have been technological advances that can provide access to care and better reimbursement procedures, there are still many limitations that our patients are facing.

(AGA applauds researchers who are working to raise our awareness of health disparities in digestive diseases. AGA is committed to addressing this important societal issue head on. Learn more about AGA’s commitment through the AGA Equity Project).

Dr. Ponni V. Perumalswami is an Associate Professor of Internal Medicine in the Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology at the University of Michigan; Ann Arbor VA Healthcare System. Dr. Perumalswami's areas of clinical interest include cirrhosis, acute/chronic liver diseases and liver transplantation. Her research program focuses on community outreach for hepatitis B and C screening and linking patients to care.

Q: For patients with liver disease who live in underserved and vulnerable communities, what barriers to that care are more prominent or at the primary systemic-level?

Dr. Perumalswami: I think a major barrier has been our approach to thinking about these barriers, so I'm glad you are asking this question in terms of what the systemic-level barriers are rather than, for example, patient-level barriers. I'll use viral hepatitis as an example in terms of liver-disease care. I think for a very long time we've placed an unfair, onus on patients, leaving them to find their own care and to navigate existing system-level barriers such as language proficiency, health literacy, lack of insurance, and long distances to access specialists by themselves. This “do-it-yourself” approach has created a systemic-level barrier to finding specialists, and it remains a major problem. We would do a better job of improving access to care by re-thinking all barriers to care as system-and provider-level barriers rather than patient-level barriers because it is often the case that solutions that address systems barriers can address these issues.

Many specialists, like myself, are often geographically clustered at tertiary care and urban academic centers but the reality is that patients who are at risk for living with liver disease live all over, including rural areas, where fewer specialists practice. But advancements in treatments of certain liver diseases, such as hepatitis C virus (HCV), have made it possible for frontline community providers to treat patients. Expanding these patients' treatment options, in large part, is dependent on payer policy changes to allow treatment by non-specialists, reducing the cost of treatment and giving frontline workers the support they need so that they are more confident to offer treatment while differentiating the occasional patient who may need referral to a specialist.

Cost is also a systemic-level barrier for our underserved patients with liver disease and comes in many forms. Barriers related to cost include lack or type of insurance, traveling distances which also entails a cost for time (i.e. loss of wages, caregiver support), and cost of treatments. There are certain restrictions on HCV treatments that designate who can administer them and at what point in disease progression the therapy be introduced. These restrictions have been arbitrarily set by payers for treatments like direct-acting antivirals (DAA) and unfortunately dictate "when they can be obtained" and "who can prescribe them." Instead, we should spend time and effort to determine how we can have more providers practicing in different spaces, who might be equipped and motivated to provide treatment, and do it safely and easily.

Another barrier I will mention is the lack of integrated care for patients with certain liver diseases within healthcare systems. Notable examples include integrated care for those with alcohol-associated liver disease and viral hepatitis, who often have co-occurring mental health issues and substance use, addiction, or opioid use disorders. We need to think through how we can get integrated treatment and care to these patients, instead of making them come to us as individual specialists. By integrating medical care into behavioral health practices or other treatment settings, and perhaps by considering nontraditional treatment modalities, we can overcome barriers to care that are all too often siloed.

The last thing that I will mention with regards to patient-level barriers is that liver diseases and their care by providers has been very stigmatized, particularly for patients with underlying mental health and/or addiction disorders. These patients do not always feel comfortable coming to see clinicians in their practices so we must recognize that our offices may be stigmatized places for some patients with liver disease. Because of this, it is vital to think about how we can integrate care into trusted spaces for patient populations who might be at risk or are living with liver disease.

Q: What aspects of these barriers have you focused on to improve screening and links to care in communities at risk?

Dr. Perumalswami: A lot of my work is focused on patients in populations who are at risk for viral hepatitis and on screening them, educating them, and linking them to care in their communities. The challenge in successfully treating patients with a liver disease is that most liver diseases remain silent until they've progressed to a very advanced stage. Certain populations are at a higher risk for contracting these diseases compared to others. For example, with hepatitis B virus, we know that foreign-born populations have a higher infection rate, and how and when they seek care might be very different in terms of being symptom-driven versus preventive care as a result of cultural factors around health seeking behaviors. Our team has attempted to take a more proactive approach; first, to understand who might be at risk, and second, to try to bring screening to trusted places where patients can easily access care. We have found this proactive approach to be very successful in terms of identifying people who are not yet diagnosed with liver disease and then linking them into care.

The first step is knowing which populations you want to target with respect to individual types of liver disease, then working with community partners to bring screening out into the community. Obviously, the challenging part is getting people linked into care. As stated previously, many liver diseases in their earlier stages stay silent and manifest without symptoms, thus why it is vital to offer at-risk patients testing or screening.

The next step is to raise patient awareness and provide education as to why it is important to seek care; to get a thorough evaluation in terms of the extent of the liver disease and how to best manage and treat it, long term. For example, we have found that care coordination works very well with patients living with HCV. For patients with hepatitis B, we have found that culturally informed patient navigation services are very helpful, so we work with peers in the community who speak the same language and who come from the same communities as the patients identified as at-risk. This combined strategy of testing and then linking to care has been very successful.

I will say an important part of the care-coordination piece is addressing the competing priorities that patients have in their lives. For example, if they need housing, we refer them to housing services; if they have food insecurities, we try to address the need. Once you address their basic determinants of health, you have established a basis for trust while helping patients contend with important competing priorities. This way, your team has enabled potential patients to prioritize and engage in health care.

Q: How have you integrated HCV treatment into harm reduction and opioid use disorder settings?

Dr. Perumalswami: I am fortunate to be involved with a program here in Michigan whose goal is to increase HCV treatment through an open access, HCV consultation program through the Michigan Opioid Collaborative. The premise is to find motivated, interested providers who want to learn how to offer HCV treatment to patients in their communities; the majority of these providers are in rural parts of Michigan. In this setting, we are working with frontline medical personnel in the community, many of whom are either addiction providers or are offering opioid use disorder treatment, and who are also seeing HCV patients. We have set up an open-case consulting program where providers can submit cases for review with guidance from hepatologists. Attendance is optional and we meet for an hour, every other week and we talk through cases in more detail as a group. The result is that the providers have reported that they feel less isolated doing this as a team, having a place to discuss cases and work through practical challenges that can arise with this patient base. While HCV treatment advances have made great strides, many providers want reassurance or guidance in terms how to implement these programs so as a group, we walk through a few cases, demonstrate how to check for drug-drug interactions and how to perform fibrosis assessments. After these providers go through this training, they become more comfortable giving treatment on their own.

The second project, which I have also been fortunate to be involved in, is led by my colleague Dr. Jeffrey Weiss at Mount Sinai Hospital and is located at a syringe exchange program in a Brooklyn, New York. Here, patients attend receive in-person and/or telemedicine-based HCV treatment, which is a new model of care for us. While it has produced a different set of challenges in terms of engaging and bringing treatment to patients in a new space, it has been a great way to meet our objectives of helping patients to be treated where they are comfortable accessing care and services.

Q: Has the pandemic created any new challenges in treating at risk or special populations?

Dr. Perumalswami: The pandemic presented many new challenges. The primary impact that COVID-19 has had on our patients has been with the disruption in care; particularly for those patients who already found it challenging to seek and receive care. For patients who benefitted from following a routine, other pandemic-related challenges were the restrictions placed on our practices, and the reduced hours patients had to contend with access services and treatments at places such as syringe exchange programs or methadone programs.

Many of our patients have expressed feeling isolated as they are not able to get the same type of support that they were previously receiving. The decreases in viral hepatitis outreach, in screening in the community, and in practices resulted in a decrease in diagnosis and treatment.

We have also heard numerous discussions with regards to better reimbursements for phone call and telehealth sessions, but we must recognize that those things are not accessible to all patients. Many of our most vulnerable populations, do not have working phones, stable housing, or smart devices to access telehealth, so while there have been technological advances that can provide access to care and better reimbursement procedures, there are still many limitations that our patients are facing.

(AGA applauds researchers who are working to raise our awareness of health disparities in digestive diseases. AGA is committed to addressing this important societal issue head on. Learn more about AGA’s commitment through the AGA Equity Project).

Transplanting Organs from Hepatitis C Virus Seropositive Donors to Hepatitis C Virus Seronegative Recipients

Anna Suk-Fong Lok, M.D., is assistant dean for clinical research, a post she has held since March 2016. She also is the Alice Lohrman Andrews Research Professor in Hepatology and director of clinical hepatology. Her research focuses on the natural history and treatment of hepatitis B and C, and the prevention of liver cancer.

Q: Are there any unique operative or preparation steps required for this type of transplant regarding the donor, recipient, or both? Walk us through any differences from standard transplant procedures.

Dr. Lok: There’s nothing special about the surgical operation itself other than the surgeon’s need to remember that the organs came from an HCV+ donor, so they should be a little bit more careful. This procedure should only be done within a protocol where the possibility of putting in an organ from an HCV+ to HCV- recipient is being discussed ahead of time and agreed to by both the transplant team within the institute, and with the potential recipients.

Currently, all donors in the U.S. are tested for hepatitis C antibody and also for hepatitis C RNA using what we call nucleic acid (NAT or PCR) test. It is important to differentiate between a donor who is anti-HCV+ but NAT negative, versus someone who is anti-HCV+ and NAT positive. Someone who is anti-HCV+ and NAT or PCR positive is capable of transmitting the infection, whereas someone who is anti-HCV+ but NAT or PCR negative, had a prior infection, is no longer infected, and is not going to transmit the infection.

It is important to have a discussion with the recipient ahead of time. The recipients will most likely be HCV-, so we are going to be giving them an infection, because we are transplanting an organ from an HCV-infected donor. It is best to have the discussion at the time of listing, with written consent, and rediscuss as the patients get closer to the top of the list. It can be several years before they move to the top and receive a transplant. What was discussed and agreed on with the patient 2 or 3 years ago might be forgotten, and it is important to bring it up again as the patients get closer to their transplant date. In addition, we need to reverify the consent when it is time for the actual transplant. The surgery itself is similar, whether the donor is HCV+ or HCV-, but the transplant center needs to have a protocol ahead of time. There are several ways to minimize the impact on the recipient. How do we monitor for infection in the recipient? When do we start HCV direct-acting antiviral (DAA) therapy? Who is going to pay for it? What about insurance coverage? The answers to all these questions need to be in place.

During the early post-transplant period, doctors place patients on many different medications, which can cause interference with the DAAs, so we need to be cautious about potential drug-drug interactions. Some programs start in the first few days post-transplant, others start the day before transplant and continue through the transplant period, yet others start only after the patient is stable post-transplant, which can vary from a few days to a few weeks. Some patients are not ready to take oral medications right after the transplant because they just had a major operation. Debate continues over whether we can crush these pills and put them down a feeding tube. The manufacturers of these medications have not provided the data to show how well these drugs are absorbed when crushed. Still, limited data appear to suggest that some DAAs can be crushed and are effective when put down the feeding tube.

Q: In addition to increasing the donor pool, what are other benefits of this manner of transplantation?

Dr. Lok: Some patients may be sick, going in and out of the hospital because of the underlying end-organ damage, and it is getting worse. The willingness to accept an HCV+ organ might mean that they can get transplanted sooner. There are also some data to suggest that HCV+ donors tend to be younger, with fewer comorbidities, and potentially the organ quality could be better.

Q: Do the risks and possible side effects outweigh the potential benefits of this type of transplantation?

Dr. Lok: Overall, the benefits outweigh the risk, in my opinion. There are several reasons: 1) it allows the recipient to have an earlier transplant. So, they do not have to continue to suffer from the end-organ damage; and 2) the success rate of HCV cure with the DAA drugs is very high. And we certainly know that even when we administer it post-transplant, most of the regimens have been 95% to 100% successful.

A wide range of regimens are currently in practice. Many transplant centers use the classical regimen of 8 to 12 weeks of treatment. We know that some transplant programs have shortened the duration of treatment to 4 weeks or even shorter. But some of the ultra-short regimens may be associated with a lower rate of success. And that is why it is important for people to really think through what protocols would be most cost-effective.

The key thing here is to really ensure success. We are introducing a new infection; many of us would consider even a drop from a success rate of 98% to 90% to be unacceptable. There are times when a success rate is lower because patients encounter complications after the transplant operation that results in interruption of treatment. This is one reason why, I think, that if the patients cannot take the pills by mouth, we should consider administering the medications through the feeding tube rather than stopping the treatment.

We certainly know that when we start, DAAs can affect the success rate. If we wait until the patient is truly stable post-transplant, and if the patient did have postoperative complications lasting more than a couple of weeks, the delay would be too long. There have been occasional reports of these patients suffering adverse consequences, including kidney injury related to HCV glomerulonephritis, or Fibrosing cholestatic hepatitis (FCH)—a severe and rapidly progressive form of liver damage.

Thus, it is very important to make sure that we start the treatment as soon as possible and that is why some of the programs have moved to starting one day before a patient has transplant surgery.

Another aspect that should be considered is that some of the HCV+ donors might have underlying liver disease. When HCV+ livers are being used, a liver biopsy should be performed to ensure there is no significant liver damage. This is, generally speaking, not a problem because many of the HCV+ donors are young and likely have been infected for a short period of time. The use ofHCV+ organs in HCV- recipients is relatively new. We know that the risk is short-term, but we do not know what the long-term risk is. The data we have so far extends to one-year post-transplant and shows no negative impact, but a longer follow-up is needed.

Q: How reluctant have insurance companies been to lower treatment barriers, such as cost and coverage approvals?

Dr. Lok: There were many concerns early on, but now this procedure has become more common. This is an accepted practice within the transplant community and has been endorsed by professional societies. We also know that the cost of the DAAs has been greatly reduced. And it is certainly shown to be cost-effective and cost-saving. If it allows us to get these patients transplanted sooner, if we can save one hospital admission because of cirrhosis complications prior to transplant, it is a win for the patient, who will save money as a result.

Q: This transplantation method started with kidneys. How have other organs fared such as liver, heart, and lungs?

Dr. Lok: Yes, this procedure started with the kidneys, but is now widely accepted for liver, lung, heart, pancreas, and even some of the combined transplants such as kidney and pancreas. The good news is that the success rate of the DAA is similar whether you had a kidney or heart transplant. The willingness to accept HCV+ organs in 2018 had increased by about 30% to 40% for all organs compared to 2015, except for intestines, but intestinal transplant is rare. So, the increase has occurred for all organs.

Anna Suk-Fong Lok, M.D., is assistant dean for clinical research, a post she has held since March 2016. She also is the Alice Lohrman Andrews Research Professor in Hepatology and director of clinical hepatology. Her research focuses on the natural history and treatment of hepatitis B and C, and the prevention of liver cancer.

Q: Are there any unique operative or preparation steps required for this type of transplant regarding the donor, recipient, or both? Walk us through any differences from standard transplant procedures.

Dr. Lok: There’s nothing special about the surgical operation itself other than the surgeon’s need to remember that the organs came from an HCV+ donor, so they should be a little bit more careful. This procedure should only be done within a protocol where the possibility of putting in an organ from an HCV+ to HCV- recipient is being discussed ahead of time and agreed to by both the transplant team within the institute, and with the potential recipients.

Currently, all donors in the U.S. are tested for hepatitis C antibody and also for hepatitis C RNA using what we call nucleic acid (NAT or PCR) test. It is important to differentiate between a donor who is anti-HCV+ but NAT negative, versus someone who is anti-HCV+ and NAT positive. Someone who is anti-HCV+ and NAT or PCR positive is capable of transmitting the infection, whereas someone who is anti-HCV+ but NAT or PCR negative, had a prior infection, is no longer infected, and is not going to transmit the infection.

It is important to have a discussion with the recipient ahead of time. The recipients will most likely be HCV-, so we are going to be giving them an infection, because we are transplanting an organ from an HCV-infected donor. It is best to have the discussion at the time of listing, with written consent, and rediscuss as the patients get closer to the top of the list. It can be several years before they move to the top and receive a transplant. What was discussed and agreed on with the patient 2 or 3 years ago might be forgotten, and it is important to bring it up again as the patients get closer to their transplant date. In addition, we need to reverify the consent when it is time for the actual transplant. The surgery itself is similar, whether the donor is HCV+ or HCV-, but the transplant center needs to have a protocol ahead of time. There are several ways to minimize the impact on the recipient. How do we monitor for infection in the recipient? When do we start HCV direct-acting antiviral (DAA) therapy? Who is going to pay for it? What about insurance coverage? The answers to all these questions need to be in place.

During the early post-transplant period, doctors place patients on many different medications, which can cause interference with the DAAs, so we need to be cautious about potential drug-drug interactions. Some programs start in the first few days post-transplant, others start the day before transplant and continue through the transplant period, yet others start only after the patient is stable post-transplant, which can vary from a few days to a few weeks. Some patients are not ready to take oral medications right after the transplant because they just had a major operation. Debate continues over whether we can crush these pills and put them down a feeding tube. The manufacturers of these medications have not provided the data to show how well these drugs are absorbed when crushed. Still, limited data appear to suggest that some DAAs can be crushed and are effective when put down the feeding tube.

Q: In addition to increasing the donor pool, what are other benefits of this manner of transplantation?

Dr. Lok: Some patients may be sick, going in and out of the hospital because of the underlying end-organ damage, and it is getting worse. The willingness to accept an HCV+ organ might mean that they can get transplanted sooner. There are also some data to suggest that HCV+ donors tend to be younger, with fewer comorbidities, and potentially the organ quality could be better.

Q: Do the risks and possible side effects outweigh the potential benefits of this type of transplantation?

Dr. Lok: Overall, the benefits outweigh the risk, in my opinion. There are several reasons: 1) it allows the recipient to have an earlier transplant. So, they do not have to continue to suffer from the end-organ damage; and 2) the success rate of HCV cure with the DAA drugs is very high. And we certainly know that even when we administer it post-transplant, most of the regimens have been 95% to 100% successful.

A wide range of regimens are currently in practice. Many transplant centers use the classical regimen of 8 to 12 weeks of treatment. We know that some transplant programs have shortened the duration of treatment to 4 weeks or even shorter. But some of the ultra-short regimens may be associated with a lower rate of success. And that is why it is important for people to really think through what protocols would be most cost-effective.

The key thing here is to really ensure success. We are introducing a new infection; many of us would consider even a drop from a success rate of 98% to 90% to be unacceptable. There are times when a success rate is lower because patients encounter complications after the transplant operation that results in interruption of treatment. This is one reason why, I think, that if the patients cannot take the pills by mouth, we should consider administering the medications through the feeding tube rather than stopping the treatment.

We certainly know that when we start, DAAs can affect the success rate. If we wait until the patient is truly stable post-transplant, and if the patient did have postoperative complications lasting more than a couple of weeks, the delay would be too long. There have been occasional reports of these patients suffering adverse consequences, including kidney injury related to HCV glomerulonephritis, or Fibrosing cholestatic hepatitis (FCH)—a severe and rapidly progressive form of liver damage.

Thus, it is very important to make sure that we start the treatment as soon as possible and that is why some of the programs have moved to starting one day before a patient has transplant surgery.

Another aspect that should be considered is that some of the HCV+ donors might have underlying liver disease. When HCV+ livers are being used, a liver biopsy should be performed to ensure there is no significant liver damage. This is, generally speaking, not a problem because many of the HCV+ donors are young and likely have been infected for a short period of time. The use ofHCV+ organs in HCV- recipients is relatively new. We know that the risk is short-term, but we do not know what the long-term risk is. The data we have so far extends to one-year post-transplant and shows no negative impact, but a longer follow-up is needed.

Q: How reluctant have insurance companies been to lower treatment barriers, such as cost and coverage approvals?

Dr. Lok: There were many concerns early on, but now this procedure has become more common. This is an accepted practice within the transplant community and has been endorsed by professional societies. We also know that the cost of the DAAs has been greatly reduced. And it is certainly shown to be cost-effective and cost-saving. If it allows us to get these patients transplanted sooner, if we can save one hospital admission because of cirrhosis complications prior to transplant, it is a win for the patient, who will save money as a result.

Q: This transplantation method started with kidneys. How have other organs fared such as liver, heart, and lungs?

Dr. Lok: Yes, this procedure started with the kidneys, but is now widely accepted for liver, lung, heart, pancreas, and even some of the combined transplants such as kidney and pancreas. The good news is that the success rate of the DAA is similar whether you had a kidney or heart transplant. The willingness to accept HCV+ organs in 2018 had increased by about 30% to 40% for all organs compared to 2015, except for intestines, but intestinal transplant is rare. So, the increase has occurred for all organs.

Anna Suk-Fong Lok, M.D., is assistant dean for clinical research, a post she has held since March 2016. She also is the Alice Lohrman Andrews Research Professor in Hepatology and director of clinical hepatology. Her research focuses on the natural history and treatment of hepatitis B and C, and the prevention of liver cancer.

Q: Are there any unique operative or preparation steps required for this type of transplant regarding the donor, recipient, or both? Walk us through any differences from standard transplant procedures.

Dr. Lok: There’s nothing special about the surgical operation itself other than the surgeon’s need to remember that the organs came from an HCV+ donor, so they should be a little bit more careful. This procedure should only be done within a protocol where the possibility of putting in an organ from an HCV+ to HCV- recipient is being discussed ahead of time and agreed to by both the transplant team within the institute, and with the potential recipients.

Currently, all donors in the U.S. are tested for hepatitis C antibody and also for hepatitis C RNA using what we call nucleic acid (NAT or PCR) test. It is important to differentiate between a donor who is anti-HCV+ but NAT negative, versus someone who is anti-HCV+ and NAT positive. Someone who is anti-HCV+ and NAT or PCR positive is capable of transmitting the infection, whereas someone who is anti-HCV+ but NAT or PCR negative, had a prior infection, is no longer infected, and is not going to transmit the infection.

It is important to have a discussion with the recipient ahead of time. The recipients will most likely be HCV-, so we are going to be giving them an infection, because we are transplanting an organ from an HCV-infected donor. It is best to have the discussion at the time of listing, with written consent, and rediscuss as the patients get closer to the top of the list. It can be several years before they move to the top and receive a transplant. What was discussed and agreed on with the patient 2 or 3 years ago might be forgotten, and it is important to bring it up again as the patients get closer to their transplant date. In addition, we need to reverify the consent when it is time for the actual transplant. The surgery itself is similar, whether the donor is HCV+ or HCV-, but the transplant center needs to have a protocol ahead of time. There are several ways to minimize the impact on the recipient. How do we monitor for infection in the recipient? When do we start HCV direct-acting antiviral (DAA) therapy? Who is going to pay for it? What about insurance coverage? The answers to all these questions need to be in place.

During the early post-transplant period, doctors place patients on many different medications, which can cause interference with the DAAs, so we need to be cautious about potential drug-drug interactions. Some programs start in the first few days post-transplant, others start the day before transplant and continue through the transplant period, yet others start only after the patient is stable post-transplant, which can vary from a few days to a few weeks. Some patients are not ready to take oral medications right after the transplant because they just had a major operation. Debate continues over whether we can crush these pills and put them down a feeding tube. The manufacturers of these medications have not provided the data to show how well these drugs are absorbed when crushed. Still, limited data appear to suggest that some DAAs can be crushed and are effective when put down the feeding tube.

Q: In addition to increasing the donor pool, what are other benefits of this manner of transplantation?

Dr. Lok: Some patients may be sick, going in and out of the hospital because of the underlying end-organ damage, and it is getting worse. The willingness to accept an HCV+ organ might mean that they can get transplanted sooner. There are also some data to suggest that HCV+ donors tend to be younger, with fewer comorbidities, and potentially the organ quality could be better.

Q: Do the risks and possible side effects outweigh the potential benefits of this type of transplantation?

Dr. Lok: Overall, the benefits outweigh the risk, in my opinion. There are several reasons: 1) it allows the recipient to have an earlier transplant. So, they do not have to continue to suffer from the end-organ damage; and 2) the success rate of HCV cure with the DAA drugs is very high. And we certainly know that even when we administer it post-transplant, most of the regimens have been 95% to 100% successful.

A wide range of regimens are currently in practice. Many transplant centers use the classical regimen of 8 to 12 weeks of treatment. We know that some transplant programs have shortened the duration of treatment to 4 weeks or even shorter. But some of the ultra-short regimens may be associated with a lower rate of success. And that is why it is important for people to really think through what protocols would be most cost-effective.

The key thing here is to really ensure success. We are introducing a new infection; many of us would consider even a drop from a success rate of 98% to 90% to be unacceptable. There are times when a success rate is lower because patients encounter complications after the transplant operation that results in interruption of treatment. This is one reason why, I think, that if the patients cannot take the pills by mouth, we should consider administering the medications through the feeding tube rather than stopping the treatment.

We certainly know that when we start, DAAs can affect the success rate. If we wait until the patient is truly stable post-transplant, and if the patient did have postoperative complications lasting more than a couple of weeks, the delay would be too long. There have been occasional reports of these patients suffering adverse consequences, including kidney injury related to HCV glomerulonephritis, or Fibrosing cholestatic hepatitis (FCH)—a severe and rapidly progressive form of liver damage.

Thus, it is very important to make sure that we start the treatment as soon as possible and that is why some of the programs have moved to starting one day before a patient has transplant surgery.

Another aspect that should be considered is that some of the HCV+ donors might have underlying liver disease. When HCV+ livers are being used, a liver biopsy should be performed to ensure there is no significant liver damage. This is, generally speaking, not a problem because many of the HCV+ donors are young and likely have been infected for a short period of time. The use ofHCV+ organs in HCV- recipients is relatively new. We know that the risk is short-term, but we do not know what the long-term risk is. The data we have so far extends to one-year post-transplant and shows no negative impact, but a longer follow-up is needed.

Q: How reluctant have insurance companies been to lower treatment barriers, such as cost and coverage approvals?

Dr. Lok: There were many concerns early on, but now this procedure has become more common. This is an accepted practice within the transplant community and has been endorsed by professional societies. We also know that the cost of the DAAs has been greatly reduced. And it is certainly shown to be cost-effective and cost-saving. If it allows us to get these patients transplanted sooner, if we can save one hospital admission because of cirrhosis complications prior to transplant, it is a win for the patient, who will save money as a result.

Q: This transplantation method started with kidneys. How have other organs fared such as liver, heart, and lungs?

Dr. Lok: Yes, this procedure started with the kidneys, but is now widely accepted for liver, lung, heart, pancreas, and even some of the combined transplants such as kidney and pancreas. The good news is that the success rate of the DAA is similar whether you had a kidney or heart transplant. The willingness to accept HCV+ organs in 2018 had increased by about 30% to 40% for all organs compared to 2015, except for intestines, but intestinal transplant is rare. So, the increase has occurred for all organs.

Management of patients with HCV who fail first line DAA regimens

Joseph K. Lim, MD, is the Director of Clinical Hepatology and Professor of Medicine in the Department of Medicine, Section of Digestive Diseases, Yale Liver Center, at the Yale University School of Medicine in New Haven, Connecticut. Dr. Lim's primary clinical and research interests are focused on viral hepatitis and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis.

What are some of the reasons for first line direct-acting antiviral (DAA) regimen failures in hepatitis C virus (HCV)?

Dr. Lim: In clinical practice, approximately 5% to 10% of patients will fail to achieve sustained virologic response (SVR). The most common reason is incompletion of treatment as a result of non-adherence, intolerance, adverse effects, or other medical/logistical factors that interfere with treatment. Another reason is reinfection, in which an individual who achieves viral eradication is re-exposed to HCV and develops a new infection. Each scenario warrants a careful evaluation to help identify which factors contributed to treatment failure.

Regarding incomplete treatment, it is important to identify other issues that require attention before considering retreatment. If there are other potential medications with potential drug-drug interaction (DDI) which influence the absorption of the DAA medications, that is important to identify (e.g. proton pump inhibitors).

Finally, if there are other non-medical reasons—psychosocial reasons, substance use reasons, or psychiatric reasons—that may prevent a patient from completing a full treatment course, it is important to identify and manage these before reconsidering DAA therapy.

What is the current standard of care for patients who failed a first line DAA regimen?

Dr. Lim: Fewer than 5% to 10% of patients treated with a first-line regimen fail to achieve a sustained virologic response (SVR). A significant proportion may develop resistance-associated substitutions (RASs) which may affect susceptibility to other DAA regimens, but fortunately, multiple studies have confirmed that retreatment of these patients with a contemporary DAA treatment regimen is associated with similarly high rates of SVR exceeding 90%.

The current guidelines by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) and the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) suggest retreating these patients with a triple combination regimen of sofosbuvir, velpatasvir, plus voxilaprevir (also known as SOF/VEL/VOX) or glecaprevir plus pibrentasvir (GP).

Both are viable options for those who fail first line regimens, but with important nuances: 1) for patients who are genotype 1, either of these options is considered a valid regimen strategy; 2) for patients with genotype 2 through 6, the SOF/VEL/VOX combination is recommended; 3) for patients who have signature mutations for either the protease or the nonstructural protein 5A (NS5A), an individualized approach is needed to determine which strategy will be most efficacious; 4) for patients who have cirrhosis, and particularly those with decompensated cirrhosis, protease inhibitor-based combinations are contraindicated because of the risk of liver toxicity and/or hepatic decompensation, which is associated with an FDA black box warning.

Treatment of the very small number of patients who fail the second-line regimen with either GP or SOF/VEL/VOXis an area of significant controversy, and for which the evidence-based guidance in 2021 is quite limited. However, the AASLD and the IDSA recommend 2 potential regimens, including SOF/VEL/VOX plus weight-based ribavirin for 24 weeks, or sofosbuvir plus GP plus weight-based ribavirin for 16 weeks.

Why can it be difficult to differentiate true virological failure from relapse caused by non-adherence or from reinfection?

Dr. Lim: When I speak with patients who have failed DAAs, the majority state that they took every single pill. And although that leaves us in a conundrum where we cannot chalk it up to possible non-adherence, we do wish to determine whether the timing of when they took the medications was consistent.

We ask about whether there are other medications that may interact with these medications. Before we start treatment, we work with a pharmacist and online drug interaction websites to make sure that we do our best to avoid other medications that may interact with DAAs and impact the chance of achieving sustained virologic response (SVR). Despite those efforts, on occasion, patients report that they forgot they were taking a drug or supplement that could interfere with DAA absorption.

Lastly, in patients who offered no history of taking other medications and a report of 100% adherence, we make a presumption that this is probably true virological failure with development of virologic resistance. In 2021, AASLD/IDSA guidelines do not routinely recommend resistance testing for all patients who fail a first-line regimen because it frequently does not influence our decision on retreatment and may not always impact susceptibility to SOF/VEL/VOX or GP. However, in patients who have a history of multiple lines of treatment failure, some of whom have failed 4 or more previous treatment regimens, I do perform resistance testing on an individualized basis to inform our retreatment strategy.

With regards to the question about reinfection, there is no routine way this is assessed in clinical practice. From a public health perspective, we can perform phylogenetic testing, which can help distinguish the very specific viral strains to connect individuals in terms of the root of the infection. But in clinical practice, we do not use phylogenetic testing because if a patient’s initial genotype was genotype 1 and then they get reinfected, and their genotype was genotype 3, you do not need any special testing. At that point you know it is a different virus than what you initially had, and so that is the easiest way to make a distinction. If they have a different genotype of HCV the second time around, we generally will conclude that it represents reinfection rather than virologic relapse, although conversely, the discovery of the same genotype does not exclude reinfection.

Ninety-five percent of individuals treated with DAA agents are cured of HCV infection. Of the 5% who failed first line DAA regimens, what are their options and chances for being cured?

Dr. Lim: Again, retreatment with either SOF/VEL/VOX or GP is associated with a very high rate of SVR. Specifically, for SOF/VEL/VOX, there are two phase 3 clinical trials. One is POLARIS-1 for genotypes 1 through 6 and the other is POLARIS-4 for those with genotype 1 through 4. In both of those clinical trials, they reported a 96% to 97% chance of achieving SVR.1, 2 For GP, the MAGELLAN-1 protocol looked at patients, specifically genotype 1, and found that GP was associated with a 96% chance of SVR.3 As such, there is robust prospective RCT evidence validating the safety and efficacy of both SOF/VEL/VOX and GP for patients who fail first line DAA regimens.

How do people with HIV and persons who use drugs factor into DAA failures, and how does it affect them? How can their unique needs be met, and what special considerations can be made for them going forward?

Dr. Lim: Historically, HIV was viewed within our community as a “special population.” And the reason why was that with some older regimens, including those requiring pegylated interferon, the chance of achieving SVR was about 20% lower than those who had HCV monoinfection. But with our contemporary DAA regimens, that differential has washed away. The expected sustained virologic response rates of those with HCV alone or with coinfection of HIV is identical, around 95%. However, from a reinfection perspective, the available data suggests no difference in rates of virologic relapse or virologic failure or treatment failure or the risk of reinfection in HIV coinfected individuals. However, patients with HIV are taking antiretroviral therapy (ART) regimens that are associated with potential DDIs, which require special attention. On occasion, modification of the ART is needed to permit safe administration of HCV DAAs. In contrast, persons who inject drugs (PWID) remain a special population because of unique challenges and considerations required in the decision of who to treat, when to treat, and how to treat.

In terms of who to treat, there has been a paradigm shift. In the past, we would want to delay treatment until patients were drug-free for 6 months or greater. Many of our current insurance policies still mandate that patients be confirmed to be drug-free for a required amount of time before they will authorize the drug's release from the pharmacy. But at this time, that paradigm has shifted to where we, as a liver community, view HCV treatment as prevention. The concept is that within injection drug communities, if we can treat and eradicate HCV in super users of injection drugs, not only does it benefit that individual patient, but it may also benefit their community of injection drug users and prevent spread to others.

It is a high priority in 2021 that clinicians within the GI, liver, and infectious disease communities are willing to treat patients who are actively injecting drugs or in the process of going through relapse prevention, and/or rehabilitation. We must accept that persons who inject drugs may experience relapse to substance use which may be associated with HCV reinfection rates as high as 10% to 15% of cases. While these numbers are significant in my view, from a public health perspective and a clinical perspective, this should not dissuade clinicians from considering an individualized approach to offering DAA therapy to all patients, including those who are PWID.

- Safety and Efficacy of Sofosbuvir/Velpatasvir/Voxilaprevir in Adults with Chronic HCV Infection who have Previously Received Treatment with Direct-Acting Antiviral Therapy (POLARIS-1). Accessed- https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02607735

- Safety and Efficacy of SOF/VEL/VOX FDC for 12 Weeks and SOF/VEL for 12 Weeks in DAA-Experienced Adults with Chronic HCV Infection who have not Received an NS5A Inhibitor (POLARIS-4). Accessed- https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02639247

- Glecaprevir-Pibrentasvir (Mavyret). Accessed- https://www.hepatitisc.uw.edu/page/treatment/drugs/glecaprevir-pibrentasvir/clinical-trials

Joseph K. Lim, MD, is the Director of Clinical Hepatology and Professor of Medicine in the Department of Medicine, Section of Digestive Diseases, Yale Liver Center, at the Yale University School of Medicine in New Haven, Connecticut. Dr. Lim's primary clinical and research interests are focused on viral hepatitis and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis.

What are some of the reasons for first line direct-acting antiviral (DAA) regimen failures in hepatitis C virus (HCV)?

Dr. Lim: In clinical practice, approximately 5% to 10% of patients will fail to achieve sustained virologic response (SVR). The most common reason is incompletion of treatment as a result of non-adherence, intolerance, adverse effects, or other medical/logistical factors that interfere with treatment. Another reason is reinfection, in which an individual who achieves viral eradication is re-exposed to HCV and develops a new infection. Each scenario warrants a careful evaluation to help identify which factors contributed to treatment failure.

Regarding incomplete treatment, it is important to identify other issues that require attention before considering retreatment. If there are other potential medications with potential drug-drug interaction (DDI) which influence the absorption of the DAA medications, that is important to identify (e.g. proton pump inhibitors).

Finally, if there are other non-medical reasons—psychosocial reasons, substance use reasons, or psychiatric reasons—that may prevent a patient from completing a full treatment course, it is important to identify and manage these before reconsidering DAA therapy.

What is the current standard of care for patients who failed a first line DAA regimen?

Dr. Lim: Fewer than 5% to 10% of patients treated with a first-line regimen fail to achieve a sustained virologic response (SVR). A significant proportion may develop resistance-associated substitutions (RASs) which may affect susceptibility to other DAA regimens, but fortunately, multiple studies have confirmed that retreatment of these patients with a contemporary DAA treatment regimen is associated with similarly high rates of SVR exceeding 90%.

The current guidelines by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) and the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) suggest retreating these patients with a triple combination regimen of sofosbuvir, velpatasvir, plus voxilaprevir (also known as SOF/VEL/VOX) or glecaprevir plus pibrentasvir (GP).

Both are viable options for those who fail first line regimens, but with important nuances: 1) for patients who are genotype 1, either of these options is considered a valid regimen strategy; 2) for patients with genotype 2 through 6, the SOF/VEL/VOX combination is recommended; 3) for patients who have signature mutations for either the protease or the nonstructural protein 5A (NS5A), an individualized approach is needed to determine which strategy will be most efficacious; 4) for patients who have cirrhosis, and particularly those with decompensated cirrhosis, protease inhibitor-based combinations are contraindicated because of the risk of liver toxicity and/or hepatic decompensation, which is associated with an FDA black box warning.

Treatment of the very small number of patients who fail the second-line regimen with either GP or SOF/VEL/VOXis an area of significant controversy, and for which the evidence-based guidance in 2021 is quite limited. However, the AASLD and the IDSA recommend 2 potential regimens, including SOF/VEL/VOX plus weight-based ribavirin for 24 weeks, or sofosbuvir plus GP plus weight-based ribavirin for 16 weeks.

Why can it be difficult to differentiate true virological failure from relapse caused by non-adherence or from reinfection?

Dr. Lim: When I speak with patients who have failed DAAs, the majority state that they took every single pill. And although that leaves us in a conundrum where we cannot chalk it up to possible non-adherence, we do wish to determine whether the timing of when they took the medications was consistent.

We ask about whether there are other medications that may interact with these medications. Before we start treatment, we work with a pharmacist and online drug interaction websites to make sure that we do our best to avoid other medications that may interact with DAAs and impact the chance of achieving sustained virologic response (SVR). Despite those efforts, on occasion, patients report that they forgot they were taking a drug or supplement that could interfere with DAA absorption.

Lastly, in patients who offered no history of taking other medications and a report of 100% adherence, we make a presumption that this is probably true virological failure with development of virologic resistance. In 2021, AASLD/IDSA guidelines do not routinely recommend resistance testing for all patients who fail a first-line regimen because it frequently does not influence our decision on retreatment and may not always impact susceptibility to SOF/VEL/VOX or GP. However, in patients who have a history of multiple lines of treatment failure, some of whom have failed 4 or more previous treatment regimens, I do perform resistance testing on an individualized basis to inform our retreatment strategy.