User login

Since the COVID-19 pandemic began, many significant changes have occurred that have made the implementation of telemedicine easier and more attractive for gynecologic practices. In the first article in this series, we discussed the benefits of telemedicine to physicians and patients, how to get started using telemedicine, and implementing a workflow. This article will discuss the common hurdles in the process and the proper coding to use to insure reimbursement for services rendered.

Barriers to implementing telemedicine

Incorrect assumptions

Latecomers to telemedicine often assume that patients prefer face-to-face visits when, in fact, many may prefer the convenience of virtual visits. More than 50% of patients who are surveyed about their experience with telemedicine say that online tools have helped improve their relationship with their providers.1 Telemedicine has grown astronomically during the COVID-19 pandemic to the point where many patients now expect their health care providers to be able to conduct virtual visits. Practices that do not offer telemedicine may find their patients seeking services elsewhere. Nearly two-thirds of health care professionals expect their commitment to telemedicine to increase significantly in the next 3 years.2 Of those providers who have not yet adopted the practice, nearly 85% expect to implement telemedicine in the near future.3 COVID-19 has motivated the increased use of telemedicine to enhance the communication with patients, making it possible for patients to have enhanced access to health care during this pandemic while minimizing infectious transmission of COVID-19 to physicians and their staff.4

Admittedly, telemedicine is not appropriate for all patients. In general, situations that do not lend themselves to telemedicine are those for which an in-person visit is required to evaluate the patient via a physical examination, to perform a protocol-driven procedure, or provide an aggressive intervention. Additional patients for whom telemedicine may be inappropriate include those with cognitive disorders, those with language barriers, those with emergency situations that warrant an office visit or a visit to the emergency department, and patients who do not have access to the technology to conduct a virtual visit.

Cost and complexity

The process of implementing electronic health records (EHRs) left a bitter taste in the mouths of many health care professionals. But EHRs are complicated and expensive. Implementation often resulted in lost productivity. Because the learning curve was so steep, many physicians had to decrease the number of patients they saw before becoming comfortable with the conversion from paper charts to an EHR.

Telemedicine implementation is much less onerous and expensive. Telemedicine is available as a cloud-based platform, which requires less information technology (IT) support and less hardware and software. The technology required for patients to participate in telemedicine is nearly ubiquitous. According to the Pew Research Center, 96% of Americans own a cell phone (81% have a smart phone), and more than half (52%) own a tablet, so the basic equipment to connect patients to providers is already in place.5

On the provider side, the basic equipment required for a telemedicine program is a computer with video and audio capabilities and a broadband connection that is fast enough to show video in real time and to provide high-quality viewing of any images to be reviewed.

The growth in telemedicine means that telemedicine options are now more diverse, with many more affordable solutions. However, most telemedicine programs do require the purchase and set-up of new technology and equipment and the training of staff—some of which may be outside the budgets of health care providers in smaller independent practices. Many gynecologists have technology budgets that are already stretched thin. And for patients who do not have access to a smartphone or computer with Internet access, real-time telemedicine may be out of reach.

But with new guidelines put forth by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) in March 2020, connectivity can take place inexpensively using free platforms such as Google Hangouts, Skype, Facetime, and Facebook Messenger. If a non‒HIPAA-compliant platform is used initially, conversion to a HIPAA-compliant platform is recommended.6 These platforms do not require the purchase of, or subscription to, any expensive hardware or software. The disadvantages of these programs are the lack of documentation, the failure to be Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA)-compliant, and the lack of encryption; however, these disadvantages are no longer an issue after the new CMS guidelines.

Depending on the magnitude of the program, IT assistance may be needed to get started. It is imperative that the telemedicine program is interoperable with the EHR and the billing program. Otherwise, double and triple entry will erase the efficiency provided by conducting a virtual visit.

Continue to: Licensing...

Licensing

Another concern or barrier is a license to participate in telemedicine. The March 15, 2020, approval of telemedicine states that physicians who are licensed in the state where the patient is located do not require any additional license or permission to conduct virtual visits.7 CMS has temporarily waived the requirement that out-of-state providers be licensed in the state where they are providing services when they are licensed in another state. For questions regarding licensure, contact your State Board of Medicine or Department of Health for information on requirements for licenses across state lines (see “Resources,” at the end of the article).

Informed consent

Just like with any other aspect of providing care for patients, obtaining informed consent is paramount. Not only is getting informed patient consent a recommended best practice of the American Telemedicine Association (ATA), but it is actually a legal requirement in many states and could be a condition of getting paid, depending on the payer. To check the requirements regarding patient consent in your state, look at The National Telehealth Policy Resource Center’s state map (see “Resources.")

Some states do not have any requirements regarding consent for a virtual visit. Others require verbal consent. Even if it is not a legal requirement in your state, consider making it a part of your practice’s policy to obtain written or verbal consent and to document in the patient’s record that consent was obtained prior to the virtual visit so that you are protected when using this new technology.

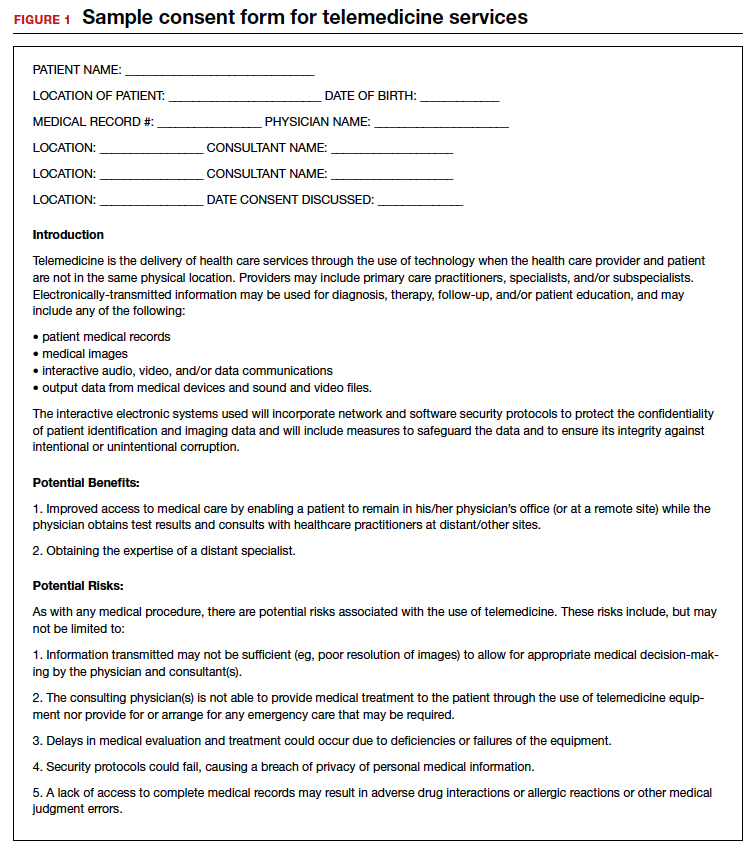

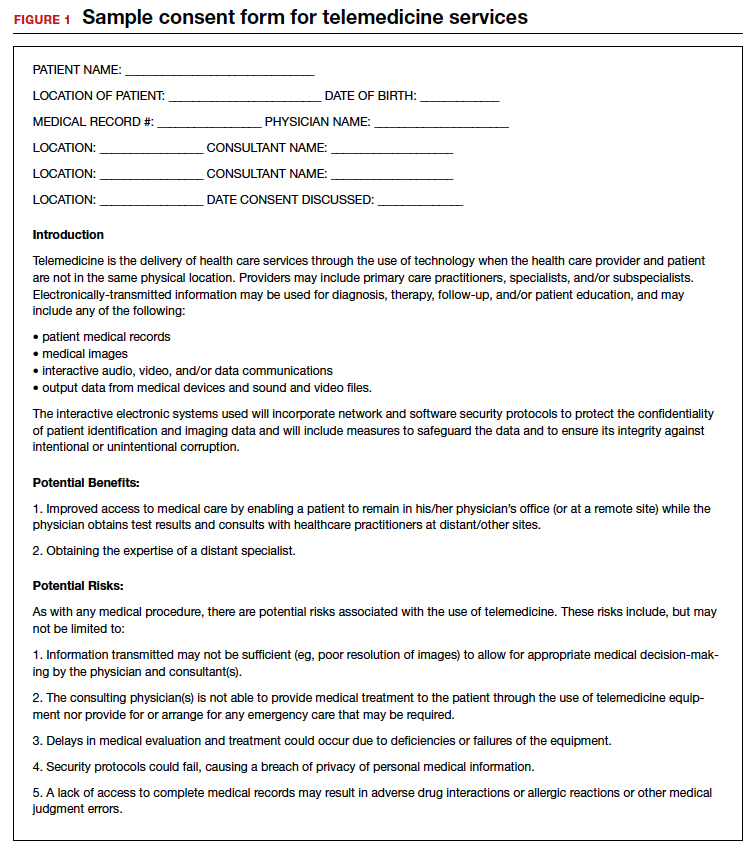

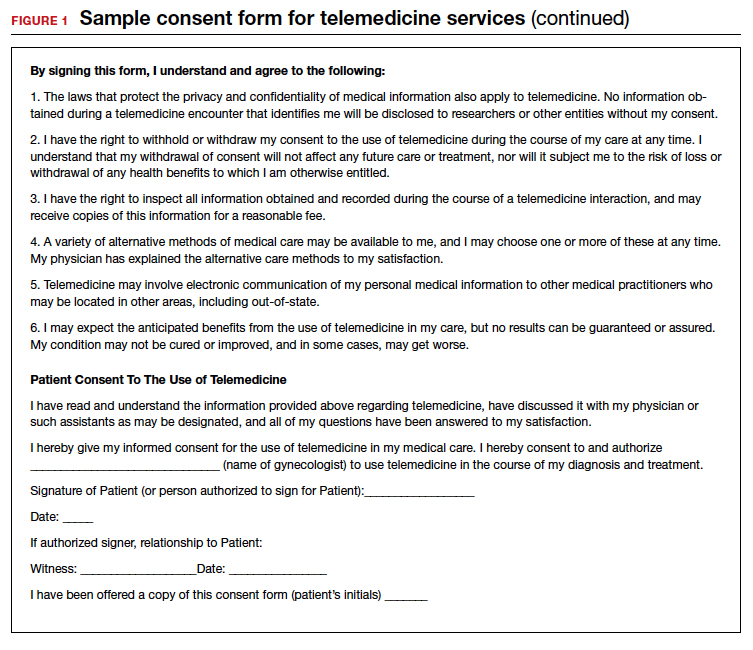

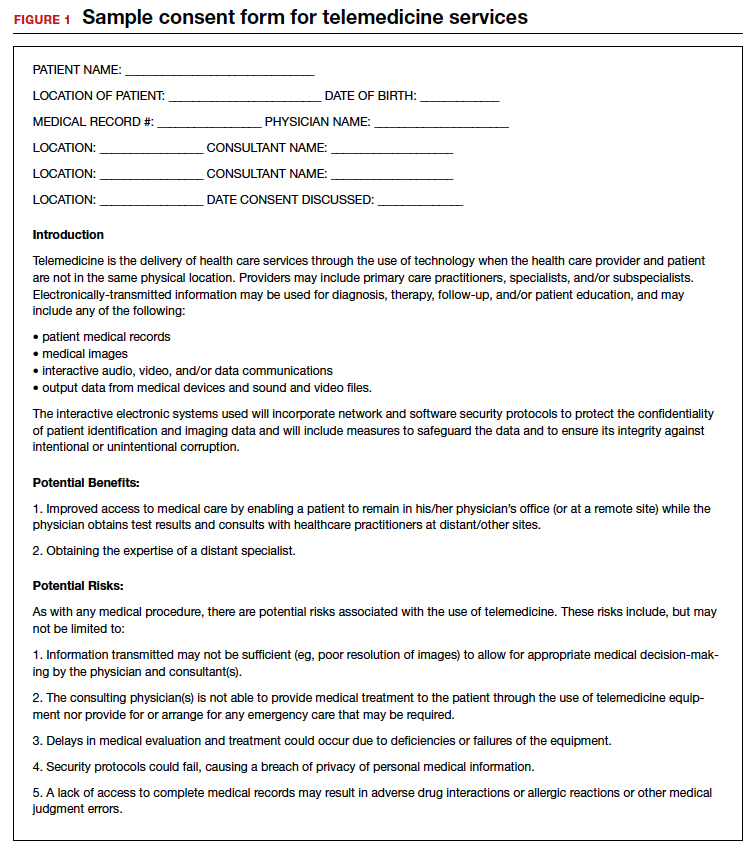

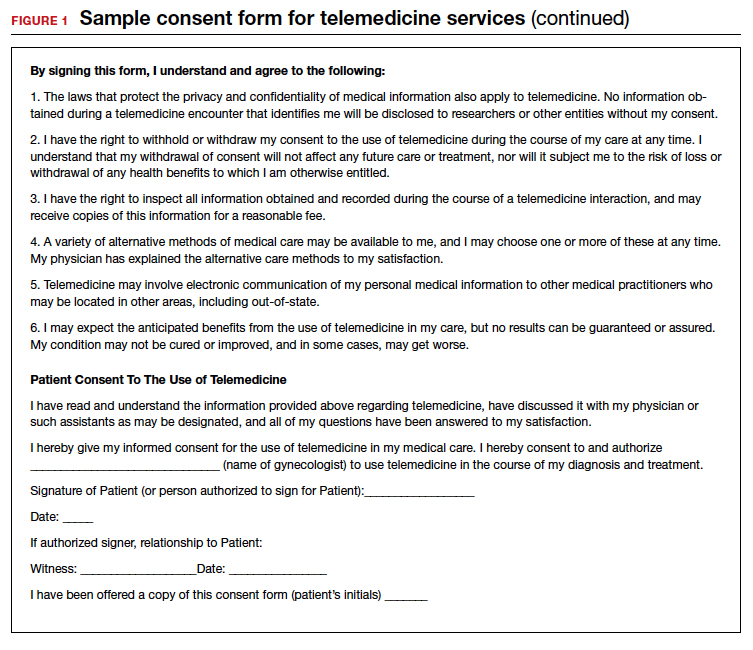

Because telemedicine is a new way of receiving care for many patients, it is important to let them know how it works including how patient confidentiality and privacy are handled, what technical equipment is required, and what they should expect in terms of scheduling, cancellations, and billing policies. A sample consent form for telemedicine use is shown in FIGURE 1.

Liability insurance

Another hurdle that must be considered is liability insurance for conducting virtual visits with patients. Gynecologists who are going to offer telemedicine care to patients should request proof in writing that their liability insurance policy covers telemedicine malpractice and that the coverage extends to other states should the patient be in another state from the state in which the gynecologist holds a license. Additionally, gynecologists who provide telemedicine care should check with liability insurers regarding any requirements or limitations to conducting a virtual visit with their patients and should document them. For example, the policy may require that the physician keep a written or recorded record of the visit in the EHR. If that is the case, then using Skype, Facebook, or Google for the virtual visit, which do not include documentation, would be less desirable.

Privacy

Certainly, there is concern about privacy, and HIPAA compliance is critical to telemedicine success. Because of the COVID-19 emergency, as of March 1, 2020, physicians may now communicate with patients, and provide telehealth services, through remote communications without penalties.8 With these changes in the HIPAA requirements, physicians may use applications that allow for video chats, including Apple FaceTime, Facebook Messenger video chat, Google Hangouts video, and Skype, to provide telehealth without risk that the Office for Civil Rights will impose a penalty for noncompliance with HIPAA rules. The consent for patients should mention that these “public” applications potentially introduce privacy risks. This is a motivation for gynecologists to consider one of the programs that promises encryption, privacy, and HIPAA compliance, such as Updox, Doxy.me, and Amazon Chime. It is also important to recognize that a virtual visit could result in colleagues (if the patient is in an office setting) or family members (if the patient is in the home environment) overhearing conversations between the health care professional and the patient. Therefore, we suggest that patients conduct virtual visits in locations in which they feel assured of some semblance of privacy.

Continue to: Compensation for telemedicine...

Compensation for telemedicine

Perhaps the biggest barrier to virtual health adoption has been compensation for telemedicine visits. Both commercial payers and CMS have been slow to enact formal policies for telemedicine reimbursement. Because of this, the common misconceptions (that providers cannot be reimbursed for telemedicine appointments or that compensation occurs at a reduced rate) have persisted, making telemedicine economically unappealing.

The good news is that this is changing; legislation in most states is quickly embracing virtual health visits as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic.9 In fact, as of January 1, 2020, telemedicine services are no longer considered “optional” coverage in Medicare Advantage plans.10 Nor are they required to have an additional fee. Instead, CMS now allows telemedicine as a standard, covered benefit in all plans, enabling beneficiaries to seek care from their homes rather than requiring them to go to a health care facility.11 In the past, telemedicine was restricted for use in rural areas or when patients resided a great distance from their health care providers. Starting March 6, 2020, and for the duration of the COVID-19 public health emergency, Medicare will make payment for professional services furnished to beneficiaries in all areas of the country in all settings regardless of location or distance between the patient and the health care provider.12

In addition, since March 15, 2020, CMS has expanded access to telemedicine services for all Medicare beneficiaries—not just those who have been diagnosed with COVID-19.13 The expanded access also applies to pre-COVID-19 coverage from physician offices, skilled nursing facilities, and hospitals. This means that Medicare will now make payments to physicians for telemedicine services provided in any health care facility or in a patient’s home, so that patients do not need to go to the physician’s office.

The facts are that there are parity laws and that commercial payers and CMS are required by state law to reimburse for telemedicine—often at the same rate as that for a comparable in-person visit. On the commercial side, there has been an increase in commercial parity legislation that requires health plans to cover virtual visits in the same way they cover face-to-face services. With the new guidelines for reimbursement, every state and Washington DC has parity laws in place. (To stay abreast of state-by-state changes in virtual health reimbursement, the Center for Connected Health Policy and the Advisory Board Primer are valuable resources. See “Resources.”) As long as the provider performs and documents the elements of history and decision-making, including the time spent counseling, and documents the visit as if a face-to-face visit occurred, then clinicians have a billable evaluation and management (E&M) visit.

Continue to: Virtual services for Medicare patients...

Virtual services for Medicare patients

There are 3 main types of virtual services gynecologists can provide to Medicare patients: Medicare telehealth visits, virtual check-ins, and e-visits.

Medicare telehealth visits. Largely because of the COVID-19 pandemic, Medicare patients may now use telecommunication technology for any services that previously occurred in an in-person communication. The gynecologist must use an interactive audio and video telecommunications system that permits real-time communication between the physician and the patient, and the patient should have a prior established relationship with the gynecologist with whom the telemedicine visit is taking place. The new guidelines indicate that the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) will not conduct audits to ensure that such a prior relationship exists for claims submitted during this public health emergency.14

The Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes for virtual visits using synchronous audio/visual communication are:

- 99201-99295, Office visit for a new patient

- 99211-99215, Office visit for an established patient.

Important modifiers for telemedicine visits include:

- modifier 02 for POS (place of service) for telehealth Medicare

- modifier 95 for commercial payers.

(A list of all available CPT codes for telehealth services from CMS can be found in “Resources.”)

Virtual check-ins. Established Medicare patients may have a brief communication with gynecologists the traditional way using a telephone or via live video. These brief virtual services, usually 5 to 10 minutes in duration, are initiated by the patient. The purpose of the virtual check-in is to determine if an office visit or a test or procedure is indicated.

Medicare pays for these “virtual check-ins” (or brief communication technology-based services) for patients to communicate with their physicians and avoid unnecessary trips to the office. These brief virtual check-ins are only for established patients. If an existing patient contacts the gynecologist’s office to ask a question or determine if an office visit is necessary, the gynecologist may bill for it using code G2012.

E-visits. Established Medicare patients may have non–face-to-face patient-initiated communications with their gynecologists without going to the physician’s office. These services can be billed only when the physician has an established relationship with the patient. The services may be billed using CPT codes 99421 to 99423. Coding for these visits is determined by the length of time the gynecologist spends online with the patient:

- 99421: Online digital evaluation and management service, for an established patient 5 to 10 minutes spent on the virtual visit

- 99422: 11 to 20 minutes

- 99423: ≥ 21 minutes.

Many clinicians want to immediately start the communication process with their patients. Many will avail themselves of the free video communication offered by Google Hangouts, Skype, Facetime, and Facebook Messenger. Since the March 15, 2020, relaxation of the HIPAA restrictions for telemedicine, it is now possible to have a virtual visit with a patient using one of the free, non–HIPAA-compliant connections. This type of visit is no different than a telephone call but with an added video component. Using these free technologies, a gynecologist can have an asynchronous visit with a patient (referred to as the store and forward method of sending information or medical images), which means that the service takes place in one direction with no opportunity for interaction with the patient. Asynchronous visits are akin to video text messages left for the patient. By contrast, a synchronous or real-time video visit with a patient is a 2-way communication that provides medical care without examining the patient.

Using triangulation

There are some downsides to telemedicine visits. First, virtual visits on Skype, FaceTime, and other non–HIPAA-compliant methods are not conducted on an encrypted website. Second, no documentation is created for the doctor-patient encounter. Finally, unless the physician keeps a record of these virtual visits and submits the interactions to the practice coders, there will be no billing and no reimbursement for the visits. In this scenario, physicians are legally responsible for their decision-making, prescription writing, and medical advice, but do not receive compensation for their efforts.

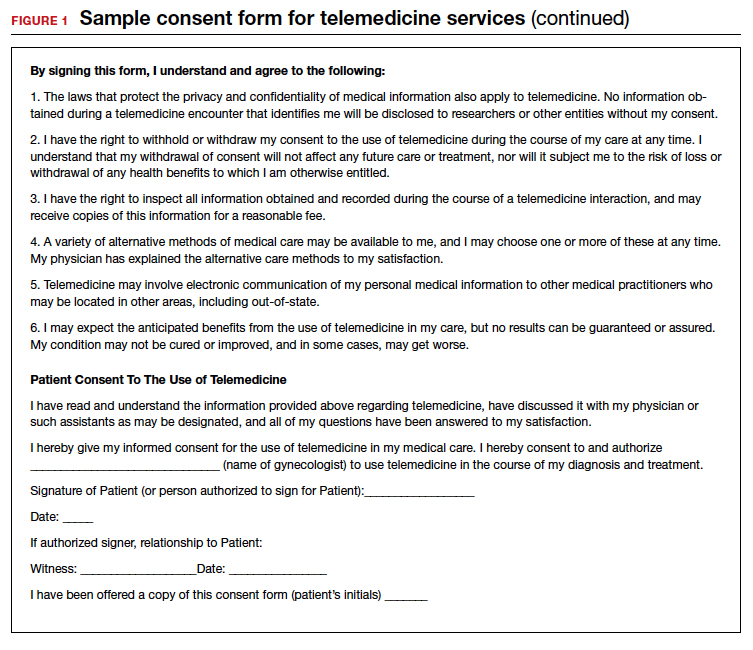

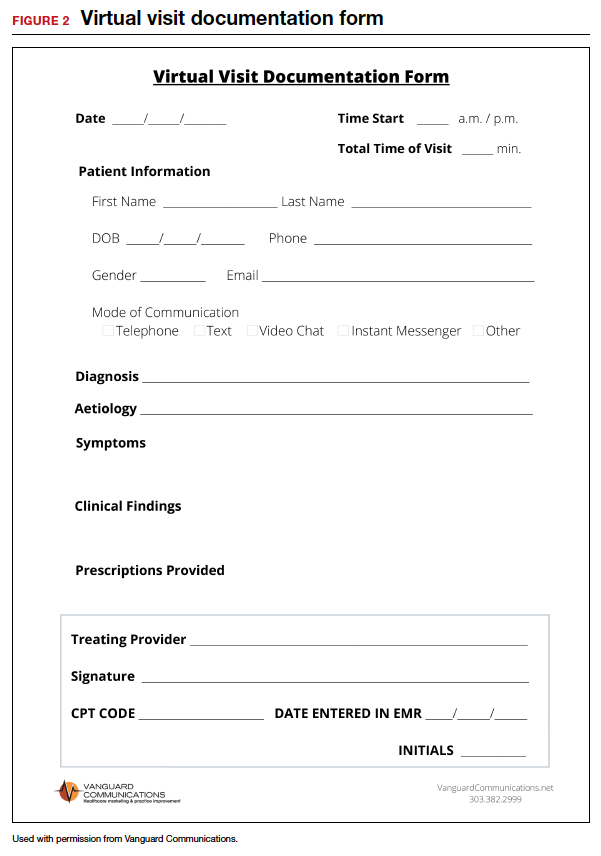

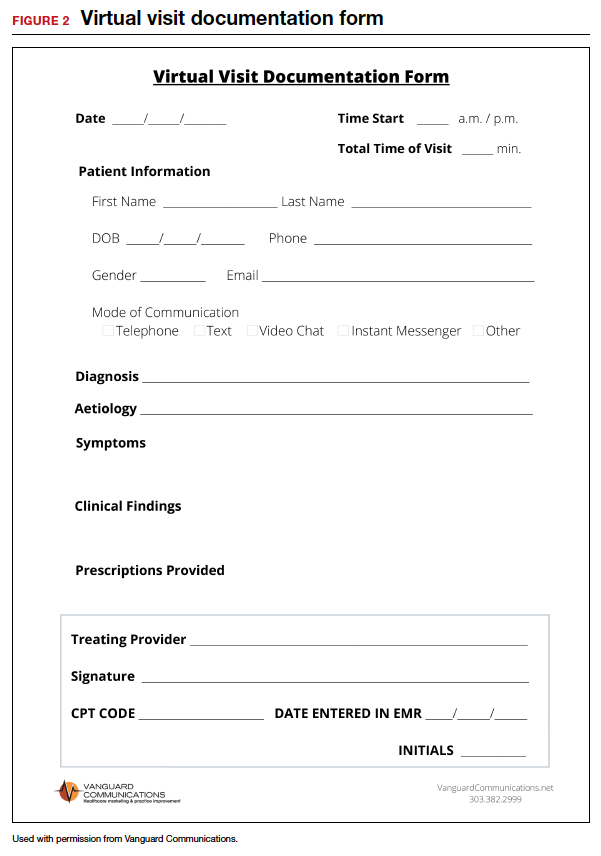

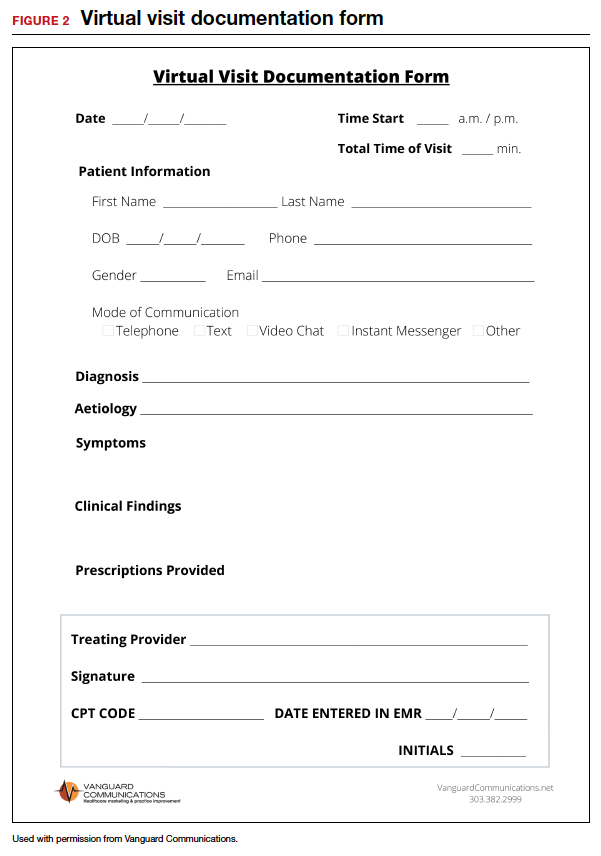

This can be remedied by using “triangulation,” which involves: 1. the physician, 2. the patient, and 3. a scribe or medical assistant who will record the visit. Before initiating the virtual visit using triangulation, it is imperative to ask the patient for permission if your medical assistant (or any other person in the office who functions as a scribe) will be listening to the conversation. It is important to explain that the person is there to take accurate notes and ascertain that the notes are entered into the EHR. Also, the scribe or assistant will record the time, date, and duration of the visit, which is a requirement for billing purposes. The scribe may also ascertain that the visit is properly coded and entered into the practice management system, and that a bill is submitted to the insurance company. By using triangulation, you have documentation that consent was obtained, that the visit took place, that notes were taken, and that the patient’s insurance company will be billed for the visit (see FIGURE 2 for a sample documentation form).

Continue to: Which CPT codes should I use?...

Which CPT codes should I use?

The answer depends on a number of factors, but a good rule of thumb is to use the same codes that you would use for an in-person appointment (CPT codes 99211-99215 for an established patient visit and 99201-99205 for a new patient visit). These are the most common CPT codes for outpatient gynecologic office visits whether they take place face-to-face or as a synchronous virtual visit (via a real-time interactive audio and video telecommunications system).

For example, the reimbursement for code 99213 has a range from $73 to $100. You may wonder how you can achieve the complexity requirements for a level-3 office visit without a physical examination. Whether as a face-to-face or virtual visit, documentation for these encounters requires 2 of 3 of the following components:

- expanded problem-focused history

- expanded problem-focused exam (not accomplished with telemedicine)

- low-complexity medical decision-making OR

- at least 15 minutes spent face to face with the patient if coding is based on time.

If a gynecologist reviews the results of a recent lab test for an estrogen-deficient patient and adjusts the estrogen dosage, writes a prescription, and spends 15 minutes communicating with the patient, he/she has met the complexity requirements for a code 99213. Because Level 3 and 4 visits (99214 and 99215) require a comprehensive physical examination, it is necessary to document the time spent with the patient (code 99214 requires 25 to 39 minutes of consultation and code 99215 requires ≥ 40 minutes).

Some final billing and coding advice

Always confirm telemedicine billing guidelines before beginning to conduct telemedicine visits. Consider starting a phone call to a payer armed with the fact that the payer is required by law to offer parity between telemedicine and face-to-face visits. Then ask which specific billing codes should be used.

Until you and your practice become comfortable with the process of, and the coding and billing for, telemedicine, consider using a telemedicine platform that has a built-in rules engine that offers recommendations for each telemedicine visit based on past claims data. These systems help gynecologists determine which CPT code to use and which modifiers are appropriate for the various insurance companies. In other words, the rules engine helps you submit a clean claim that is less likely to be denied and very likely to be paid. There are some vendors who are so confident that their rules engine will match the service with the proper CPT code and modifier that they guarantee full private payer reimbursement for telemedicine visits, or the vendor will reimburse the claim.

Watch for the third and final installment in this series, which was written with the assistance of 2 attorneys. It will review the legal guidelines for implementing telemedicine in a gynecologic practice and discuss the future of the technology. ●

- COVID-19 and Telehealth Coding Options as of March 20, 2020. https://www.ismanet.org/pdf/COVID-19andTelehealthcodes3-20-2020Updates.pdf.

- Federation of State Medical Boards. US States and Territories Modifying Licensure Requirements for Physicians in Response to COVID-19. Last updated May 26, 2020. https://www.fsmb.org/siteassets/advocacy/pdf/state-emergency-declarations-licensures-requirementscovid-19.pdf.

- Center for Connected Health Policy. Current State Laws and Reimbursement Policies https://www.cchpca.org/telehealth-policy/current-state-laws-and-reimbursement-policies.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. List of Telehealth Services. Updated April 30, 2020. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-General-Information/Telehealth/Telehealth-Codes.

- American Medical Association. AMA quick guide to telemedicinein practice. Updated May 22, 2020. https://www.ama-assn.org/practice-management/digital/ama-quick-guide-telemedicine-practice.

- Eddy N. Patients increasingly trusting of remote care technology. Healthcare IT News. October 22, 2019. https://www.healthcareitnews.com/news/patients-increasingly-trusting-remote-care-technology-says-new-report. Accessed May 26, 2020.

- Welch BM, Harvey J, O’Connell NS, et al. Patient preferences for direct-to-consumer telemedicine services: a nationwide survey. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17:784.

- Tsai JM, Cheng MJ, Tsai HH, et al. Acceptance and resistance of telehealth: the perspective of dual-factor concepts in technology adoption. Int J Inform Manag. 2019;49:34-44.

- Hollander J, Carr BG. Virtually perfect? Telemedicine for COVID-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1679-1681.

- Pew Research Center. Internet and Technology. Mobile Fact Sheet. June 12, 2019. https://www.pewresearch.org /internet/fact-sheet/mobile/. Accessed May 18, 2020.

- American Medical Association. AMA quick guide to telemedicine in practice. https://www.ama-assn.org/ practice-management/digital/ama-quick-guide-telemedicine- practice. Accessed March 20, 2020.

- Center for Connected Health Policy. Federal and state regulation updates. https://www.cchpca.org. Accessed March 20, 2020.

- The White House. Proclamation on declaring a national emergency concerning the novel coronavirus disease (Covid-19) outbreak. March 13, 2020. https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/proclamation-declaring-national-emergency-concerning-novel-coronavirus-disease-covid-19-outbreak/. Accessed May 18, 2020.

- Center for Connected Health Policy. Quick glance state telehealth actions in response to COVID-19. https://www.cchpca.org/sites/default/files/2020-05/STATE%20TELEHEALTH%20ACTIONS%20IN%20RESPONSE%20TO%20COVID%20

OVERVIEW%205.5.2020_0.pdf. AccessedMay 13, 2020. - Medicare.gov. https://www.medicare.gov/sign-up-change -plans/types-of-medicare-health-plans/medicare-advantage-plans/how-do-medicare-advantage-plans-work. Accessed May 13, 2020.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. CMS finalizes policies to bring innovative telehealth benefit to Medicare Advantage. April 5, 2019. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom /press-releases/cms-finalizes-policies-bring-innovative-telehealth-benefit-medicare-advantage. Accessed May 18,2020.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare telemedicine health care provider fact sheet. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/medicare-telemedicine-health-care-provider-fact-sheet. Accessed May 30, 2020.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare telehealth frequently asked questions. https://www.cms.gov/files/document/medicare-telehealth-frequently-asked-questions-faqs-31720.pdf.

- American Hospital Association. Coronavirus update: CMS broadens access to telehealth during Covid-19 public health emergency. https://www.aha.org/advisory/2020-03-17-coronavirus-update-cms-broadens-access-telehealth-during-covid-19-public-health. Accessed May 18, 2020.

Since the COVID-19 pandemic began, many significant changes have occurred that have made the implementation of telemedicine easier and more attractive for gynecologic practices. In the first article in this series, we discussed the benefits of telemedicine to physicians and patients, how to get started using telemedicine, and implementing a workflow. This article will discuss the common hurdles in the process and the proper coding to use to insure reimbursement for services rendered.

Barriers to implementing telemedicine

Incorrect assumptions

Latecomers to telemedicine often assume that patients prefer face-to-face visits when, in fact, many may prefer the convenience of virtual visits. More than 50% of patients who are surveyed about their experience with telemedicine say that online tools have helped improve their relationship with their providers.1 Telemedicine has grown astronomically during the COVID-19 pandemic to the point where many patients now expect their health care providers to be able to conduct virtual visits. Practices that do not offer telemedicine may find their patients seeking services elsewhere. Nearly two-thirds of health care professionals expect their commitment to telemedicine to increase significantly in the next 3 years.2 Of those providers who have not yet adopted the practice, nearly 85% expect to implement telemedicine in the near future.3 COVID-19 has motivated the increased use of telemedicine to enhance the communication with patients, making it possible for patients to have enhanced access to health care during this pandemic while minimizing infectious transmission of COVID-19 to physicians and their staff.4

Admittedly, telemedicine is not appropriate for all patients. In general, situations that do not lend themselves to telemedicine are those for which an in-person visit is required to evaluate the patient via a physical examination, to perform a protocol-driven procedure, or provide an aggressive intervention. Additional patients for whom telemedicine may be inappropriate include those with cognitive disorders, those with language barriers, those with emergency situations that warrant an office visit or a visit to the emergency department, and patients who do not have access to the technology to conduct a virtual visit.

Cost and complexity

The process of implementing electronic health records (EHRs) left a bitter taste in the mouths of many health care professionals. But EHRs are complicated and expensive. Implementation often resulted in lost productivity. Because the learning curve was so steep, many physicians had to decrease the number of patients they saw before becoming comfortable with the conversion from paper charts to an EHR.

Telemedicine implementation is much less onerous and expensive. Telemedicine is available as a cloud-based platform, which requires less information technology (IT) support and less hardware and software. The technology required for patients to participate in telemedicine is nearly ubiquitous. According to the Pew Research Center, 96% of Americans own a cell phone (81% have a smart phone), and more than half (52%) own a tablet, so the basic equipment to connect patients to providers is already in place.5

On the provider side, the basic equipment required for a telemedicine program is a computer with video and audio capabilities and a broadband connection that is fast enough to show video in real time and to provide high-quality viewing of any images to be reviewed.

The growth in telemedicine means that telemedicine options are now more diverse, with many more affordable solutions. However, most telemedicine programs do require the purchase and set-up of new technology and equipment and the training of staff—some of which may be outside the budgets of health care providers in smaller independent practices. Many gynecologists have technology budgets that are already stretched thin. And for patients who do not have access to a smartphone or computer with Internet access, real-time telemedicine may be out of reach.

But with new guidelines put forth by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) in March 2020, connectivity can take place inexpensively using free platforms such as Google Hangouts, Skype, Facetime, and Facebook Messenger. If a non‒HIPAA-compliant platform is used initially, conversion to a HIPAA-compliant platform is recommended.6 These platforms do not require the purchase of, or subscription to, any expensive hardware or software. The disadvantages of these programs are the lack of documentation, the failure to be Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA)-compliant, and the lack of encryption; however, these disadvantages are no longer an issue after the new CMS guidelines.

Depending on the magnitude of the program, IT assistance may be needed to get started. It is imperative that the telemedicine program is interoperable with the EHR and the billing program. Otherwise, double and triple entry will erase the efficiency provided by conducting a virtual visit.

Continue to: Licensing...

Licensing

Another concern or barrier is a license to participate in telemedicine. The March 15, 2020, approval of telemedicine states that physicians who are licensed in the state where the patient is located do not require any additional license or permission to conduct virtual visits.7 CMS has temporarily waived the requirement that out-of-state providers be licensed in the state where they are providing services when they are licensed in another state. For questions regarding licensure, contact your State Board of Medicine or Department of Health for information on requirements for licenses across state lines (see “Resources,” at the end of the article).

Informed consent

Just like with any other aspect of providing care for patients, obtaining informed consent is paramount. Not only is getting informed patient consent a recommended best practice of the American Telemedicine Association (ATA), but it is actually a legal requirement in many states and could be a condition of getting paid, depending on the payer. To check the requirements regarding patient consent in your state, look at The National Telehealth Policy Resource Center’s state map (see “Resources.")

Some states do not have any requirements regarding consent for a virtual visit. Others require verbal consent. Even if it is not a legal requirement in your state, consider making it a part of your practice’s policy to obtain written or verbal consent and to document in the patient’s record that consent was obtained prior to the virtual visit so that you are protected when using this new technology.

Because telemedicine is a new way of receiving care for many patients, it is important to let them know how it works including how patient confidentiality and privacy are handled, what technical equipment is required, and what they should expect in terms of scheduling, cancellations, and billing policies. A sample consent form for telemedicine use is shown in FIGURE 1.

Liability insurance

Another hurdle that must be considered is liability insurance for conducting virtual visits with patients. Gynecologists who are going to offer telemedicine care to patients should request proof in writing that their liability insurance policy covers telemedicine malpractice and that the coverage extends to other states should the patient be in another state from the state in which the gynecologist holds a license. Additionally, gynecologists who provide telemedicine care should check with liability insurers regarding any requirements or limitations to conducting a virtual visit with their patients and should document them. For example, the policy may require that the physician keep a written or recorded record of the visit in the EHR. If that is the case, then using Skype, Facebook, or Google for the virtual visit, which do not include documentation, would be less desirable.

Privacy

Certainly, there is concern about privacy, and HIPAA compliance is critical to telemedicine success. Because of the COVID-19 emergency, as of March 1, 2020, physicians may now communicate with patients, and provide telehealth services, through remote communications without penalties.8 With these changes in the HIPAA requirements, physicians may use applications that allow for video chats, including Apple FaceTime, Facebook Messenger video chat, Google Hangouts video, and Skype, to provide telehealth without risk that the Office for Civil Rights will impose a penalty for noncompliance with HIPAA rules. The consent for patients should mention that these “public” applications potentially introduce privacy risks. This is a motivation for gynecologists to consider one of the programs that promises encryption, privacy, and HIPAA compliance, such as Updox, Doxy.me, and Amazon Chime. It is also important to recognize that a virtual visit could result in colleagues (if the patient is in an office setting) or family members (if the patient is in the home environment) overhearing conversations between the health care professional and the patient. Therefore, we suggest that patients conduct virtual visits in locations in which they feel assured of some semblance of privacy.

Continue to: Compensation for telemedicine...

Compensation for telemedicine

Perhaps the biggest barrier to virtual health adoption has been compensation for telemedicine visits. Both commercial payers and CMS have been slow to enact formal policies for telemedicine reimbursement. Because of this, the common misconceptions (that providers cannot be reimbursed for telemedicine appointments or that compensation occurs at a reduced rate) have persisted, making telemedicine economically unappealing.

The good news is that this is changing; legislation in most states is quickly embracing virtual health visits as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic.9 In fact, as of January 1, 2020, telemedicine services are no longer considered “optional” coverage in Medicare Advantage plans.10 Nor are they required to have an additional fee. Instead, CMS now allows telemedicine as a standard, covered benefit in all plans, enabling beneficiaries to seek care from their homes rather than requiring them to go to a health care facility.11 In the past, telemedicine was restricted for use in rural areas or when patients resided a great distance from their health care providers. Starting March 6, 2020, and for the duration of the COVID-19 public health emergency, Medicare will make payment for professional services furnished to beneficiaries in all areas of the country in all settings regardless of location or distance between the patient and the health care provider.12

In addition, since March 15, 2020, CMS has expanded access to telemedicine services for all Medicare beneficiaries—not just those who have been diagnosed with COVID-19.13 The expanded access also applies to pre-COVID-19 coverage from physician offices, skilled nursing facilities, and hospitals. This means that Medicare will now make payments to physicians for telemedicine services provided in any health care facility or in a patient’s home, so that patients do not need to go to the physician’s office.

The facts are that there are parity laws and that commercial payers and CMS are required by state law to reimburse for telemedicine—often at the same rate as that for a comparable in-person visit. On the commercial side, there has been an increase in commercial parity legislation that requires health plans to cover virtual visits in the same way they cover face-to-face services. With the new guidelines for reimbursement, every state and Washington DC has parity laws in place. (To stay abreast of state-by-state changes in virtual health reimbursement, the Center for Connected Health Policy and the Advisory Board Primer are valuable resources. See “Resources.”) As long as the provider performs and documents the elements of history and decision-making, including the time spent counseling, and documents the visit as if a face-to-face visit occurred, then clinicians have a billable evaluation and management (E&M) visit.

Continue to: Virtual services for Medicare patients...

Virtual services for Medicare patients

There are 3 main types of virtual services gynecologists can provide to Medicare patients: Medicare telehealth visits, virtual check-ins, and e-visits.

Medicare telehealth visits. Largely because of the COVID-19 pandemic, Medicare patients may now use telecommunication technology for any services that previously occurred in an in-person communication. The gynecologist must use an interactive audio and video telecommunications system that permits real-time communication between the physician and the patient, and the patient should have a prior established relationship with the gynecologist with whom the telemedicine visit is taking place. The new guidelines indicate that the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) will not conduct audits to ensure that such a prior relationship exists for claims submitted during this public health emergency.14

The Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes for virtual visits using synchronous audio/visual communication are:

- 99201-99295, Office visit for a new patient

- 99211-99215, Office visit for an established patient.

Important modifiers for telemedicine visits include:

- modifier 02 for POS (place of service) for telehealth Medicare

- modifier 95 for commercial payers.

(A list of all available CPT codes for telehealth services from CMS can be found in “Resources.”)

Virtual check-ins. Established Medicare patients may have a brief communication with gynecologists the traditional way using a telephone or via live video. These brief virtual services, usually 5 to 10 minutes in duration, are initiated by the patient. The purpose of the virtual check-in is to determine if an office visit or a test or procedure is indicated.

Medicare pays for these “virtual check-ins” (or brief communication technology-based services) for patients to communicate with their physicians and avoid unnecessary trips to the office. These brief virtual check-ins are only for established patients. If an existing patient contacts the gynecologist’s office to ask a question or determine if an office visit is necessary, the gynecologist may bill for it using code G2012.

E-visits. Established Medicare patients may have non–face-to-face patient-initiated communications with their gynecologists without going to the physician’s office. These services can be billed only when the physician has an established relationship with the patient. The services may be billed using CPT codes 99421 to 99423. Coding for these visits is determined by the length of time the gynecologist spends online with the patient:

- 99421: Online digital evaluation and management service, for an established patient 5 to 10 minutes spent on the virtual visit

- 99422: 11 to 20 minutes

- 99423: ≥ 21 minutes.

Many clinicians want to immediately start the communication process with their patients. Many will avail themselves of the free video communication offered by Google Hangouts, Skype, Facetime, and Facebook Messenger. Since the March 15, 2020, relaxation of the HIPAA restrictions for telemedicine, it is now possible to have a virtual visit with a patient using one of the free, non–HIPAA-compliant connections. This type of visit is no different than a telephone call but with an added video component. Using these free technologies, a gynecologist can have an asynchronous visit with a patient (referred to as the store and forward method of sending information or medical images), which means that the service takes place in one direction with no opportunity for interaction with the patient. Asynchronous visits are akin to video text messages left for the patient. By contrast, a synchronous or real-time video visit with a patient is a 2-way communication that provides medical care without examining the patient.

Using triangulation

There are some downsides to telemedicine visits. First, virtual visits on Skype, FaceTime, and other non–HIPAA-compliant methods are not conducted on an encrypted website. Second, no documentation is created for the doctor-patient encounter. Finally, unless the physician keeps a record of these virtual visits and submits the interactions to the practice coders, there will be no billing and no reimbursement for the visits. In this scenario, physicians are legally responsible for their decision-making, prescription writing, and medical advice, but do not receive compensation for their efforts.

This can be remedied by using “triangulation,” which involves: 1. the physician, 2. the patient, and 3. a scribe or medical assistant who will record the visit. Before initiating the virtual visit using triangulation, it is imperative to ask the patient for permission if your medical assistant (or any other person in the office who functions as a scribe) will be listening to the conversation. It is important to explain that the person is there to take accurate notes and ascertain that the notes are entered into the EHR. Also, the scribe or assistant will record the time, date, and duration of the visit, which is a requirement for billing purposes. The scribe may also ascertain that the visit is properly coded and entered into the practice management system, and that a bill is submitted to the insurance company. By using triangulation, you have documentation that consent was obtained, that the visit took place, that notes were taken, and that the patient’s insurance company will be billed for the visit (see FIGURE 2 for a sample documentation form).

Continue to: Which CPT codes should I use?...

Which CPT codes should I use?

The answer depends on a number of factors, but a good rule of thumb is to use the same codes that you would use for an in-person appointment (CPT codes 99211-99215 for an established patient visit and 99201-99205 for a new patient visit). These are the most common CPT codes for outpatient gynecologic office visits whether they take place face-to-face or as a synchronous virtual visit (via a real-time interactive audio and video telecommunications system).

For example, the reimbursement for code 99213 has a range from $73 to $100. You may wonder how you can achieve the complexity requirements for a level-3 office visit without a physical examination. Whether as a face-to-face or virtual visit, documentation for these encounters requires 2 of 3 of the following components:

- expanded problem-focused history

- expanded problem-focused exam (not accomplished with telemedicine)

- low-complexity medical decision-making OR

- at least 15 minutes spent face to face with the patient if coding is based on time.

If a gynecologist reviews the results of a recent lab test for an estrogen-deficient patient and adjusts the estrogen dosage, writes a prescription, and spends 15 minutes communicating with the patient, he/she has met the complexity requirements for a code 99213. Because Level 3 and 4 visits (99214 and 99215) require a comprehensive physical examination, it is necessary to document the time spent with the patient (code 99214 requires 25 to 39 minutes of consultation and code 99215 requires ≥ 40 minutes).

Some final billing and coding advice

Always confirm telemedicine billing guidelines before beginning to conduct telemedicine visits. Consider starting a phone call to a payer armed with the fact that the payer is required by law to offer parity between telemedicine and face-to-face visits. Then ask which specific billing codes should be used.

Until you and your practice become comfortable with the process of, and the coding and billing for, telemedicine, consider using a telemedicine platform that has a built-in rules engine that offers recommendations for each telemedicine visit based on past claims data. These systems help gynecologists determine which CPT code to use and which modifiers are appropriate for the various insurance companies. In other words, the rules engine helps you submit a clean claim that is less likely to be denied and very likely to be paid. There are some vendors who are so confident that their rules engine will match the service with the proper CPT code and modifier that they guarantee full private payer reimbursement for telemedicine visits, or the vendor will reimburse the claim.

Watch for the third and final installment in this series, which was written with the assistance of 2 attorneys. It will review the legal guidelines for implementing telemedicine in a gynecologic practice and discuss the future of the technology. ●

- COVID-19 and Telehealth Coding Options as of March 20, 2020. https://www.ismanet.org/pdf/COVID-19andTelehealthcodes3-20-2020Updates.pdf.

- Federation of State Medical Boards. US States and Territories Modifying Licensure Requirements for Physicians in Response to COVID-19. Last updated May 26, 2020. https://www.fsmb.org/siteassets/advocacy/pdf/state-emergency-declarations-licensures-requirementscovid-19.pdf.

- Center for Connected Health Policy. Current State Laws and Reimbursement Policies https://www.cchpca.org/telehealth-policy/current-state-laws-and-reimbursement-policies.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. List of Telehealth Services. Updated April 30, 2020. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-General-Information/Telehealth/Telehealth-Codes.

- American Medical Association. AMA quick guide to telemedicinein practice. Updated May 22, 2020. https://www.ama-assn.org/practice-management/digital/ama-quick-guide-telemedicine-practice.

Since the COVID-19 pandemic began, many significant changes have occurred that have made the implementation of telemedicine easier and more attractive for gynecologic practices. In the first article in this series, we discussed the benefits of telemedicine to physicians and patients, how to get started using telemedicine, and implementing a workflow. This article will discuss the common hurdles in the process and the proper coding to use to insure reimbursement for services rendered.

Barriers to implementing telemedicine

Incorrect assumptions

Latecomers to telemedicine often assume that patients prefer face-to-face visits when, in fact, many may prefer the convenience of virtual visits. More than 50% of patients who are surveyed about their experience with telemedicine say that online tools have helped improve their relationship with their providers.1 Telemedicine has grown astronomically during the COVID-19 pandemic to the point where many patients now expect their health care providers to be able to conduct virtual visits. Practices that do not offer telemedicine may find their patients seeking services elsewhere. Nearly two-thirds of health care professionals expect their commitment to telemedicine to increase significantly in the next 3 years.2 Of those providers who have not yet adopted the practice, nearly 85% expect to implement telemedicine in the near future.3 COVID-19 has motivated the increased use of telemedicine to enhance the communication with patients, making it possible for patients to have enhanced access to health care during this pandemic while minimizing infectious transmission of COVID-19 to physicians and their staff.4

Admittedly, telemedicine is not appropriate for all patients. In general, situations that do not lend themselves to telemedicine are those for which an in-person visit is required to evaluate the patient via a physical examination, to perform a protocol-driven procedure, or provide an aggressive intervention. Additional patients for whom telemedicine may be inappropriate include those with cognitive disorders, those with language barriers, those with emergency situations that warrant an office visit or a visit to the emergency department, and patients who do not have access to the technology to conduct a virtual visit.

Cost and complexity

The process of implementing electronic health records (EHRs) left a bitter taste in the mouths of many health care professionals. But EHRs are complicated and expensive. Implementation often resulted in lost productivity. Because the learning curve was so steep, many physicians had to decrease the number of patients they saw before becoming comfortable with the conversion from paper charts to an EHR.

Telemedicine implementation is much less onerous and expensive. Telemedicine is available as a cloud-based platform, which requires less information technology (IT) support and less hardware and software. The technology required for patients to participate in telemedicine is nearly ubiquitous. According to the Pew Research Center, 96% of Americans own a cell phone (81% have a smart phone), and more than half (52%) own a tablet, so the basic equipment to connect patients to providers is already in place.5

On the provider side, the basic equipment required for a telemedicine program is a computer with video and audio capabilities and a broadband connection that is fast enough to show video in real time and to provide high-quality viewing of any images to be reviewed.

The growth in telemedicine means that telemedicine options are now more diverse, with many more affordable solutions. However, most telemedicine programs do require the purchase and set-up of new technology and equipment and the training of staff—some of which may be outside the budgets of health care providers in smaller independent practices. Many gynecologists have technology budgets that are already stretched thin. And for patients who do not have access to a smartphone or computer with Internet access, real-time telemedicine may be out of reach.

But with new guidelines put forth by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) in March 2020, connectivity can take place inexpensively using free platforms such as Google Hangouts, Skype, Facetime, and Facebook Messenger. If a non‒HIPAA-compliant platform is used initially, conversion to a HIPAA-compliant platform is recommended.6 These platforms do not require the purchase of, or subscription to, any expensive hardware or software. The disadvantages of these programs are the lack of documentation, the failure to be Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA)-compliant, and the lack of encryption; however, these disadvantages are no longer an issue after the new CMS guidelines.

Depending on the magnitude of the program, IT assistance may be needed to get started. It is imperative that the telemedicine program is interoperable with the EHR and the billing program. Otherwise, double and triple entry will erase the efficiency provided by conducting a virtual visit.

Continue to: Licensing...

Licensing

Another concern or barrier is a license to participate in telemedicine. The March 15, 2020, approval of telemedicine states that physicians who are licensed in the state where the patient is located do not require any additional license or permission to conduct virtual visits.7 CMS has temporarily waived the requirement that out-of-state providers be licensed in the state where they are providing services when they are licensed in another state. For questions regarding licensure, contact your State Board of Medicine or Department of Health for information on requirements for licenses across state lines (see “Resources,” at the end of the article).

Informed consent

Just like with any other aspect of providing care for patients, obtaining informed consent is paramount. Not only is getting informed patient consent a recommended best practice of the American Telemedicine Association (ATA), but it is actually a legal requirement in many states and could be a condition of getting paid, depending on the payer. To check the requirements regarding patient consent in your state, look at The National Telehealth Policy Resource Center’s state map (see “Resources.")

Some states do not have any requirements regarding consent for a virtual visit. Others require verbal consent. Even if it is not a legal requirement in your state, consider making it a part of your practice’s policy to obtain written or verbal consent and to document in the patient’s record that consent was obtained prior to the virtual visit so that you are protected when using this new technology.

Because telemedicine is a new way of receiving care for many patients, it is important to let them know how it works including how patient confidentiality and privacy are handled, what technical equipment is required, and what they should expect in terms of scheduling, cancellations, and billing policies. A sample consent form for telemedicine use is shown in FIGURE 1.

Liability insurance

Another hurdle that must be considered is liability insurance for conducting virtual visits with patients. Gynecologists who are going to offer telemedicine care to patients should request proof in writing that their liability insurance policy covers telemedicine malpractice and that the coverage extends to other states should the patient be in another state from the state in which the gynecologist holds a license. Additionally, gynecologists who provide telemedicine care should check with liability insurers regarding any requirements or limitations to conducting a virtual visit with their patients and should document them. For example, the policy may require that the physician keep a written or recorded record of the visit in the EHR. If that is the case, then using Skype, Facebook, or Google for the virtual visit, which do not include documentation, would be less desirable.

Privacy

Certainly, there is concern about privacy, and HIPAA compliance is critical to telemedicine success. Because of the COVID-19 emergency, as of March 1, 2020, physicians may now communicate with patients, and provide telehealth services, through remote communications without penalties.8 With these changes in the HIPAA requirements, physicians may use applications that allow for video chats, including Apple FaceTime, Facebook Messenger video chat, Google Hangouts video, and Skype, to provide telehealth without risk that the Office for Civil Rights will impose a penalty for noncompliance with HIPAA rules. The consent for patients should mention that these “public” applications potentially introduce privacy risks. This is a motivation for gynecologists to consider one of the programs that promises encryption, privacy, and HIPAA compliance, such as Updox, Doxy.me, and Amazon Chime. It is also important to recognize that a virtual visit could result in colleagues (if the patient is in an office setting) or family members (if the patient is in the home environment) overhearing conversations between the health care professional and the patient. Therefore, we suggest that patients conduct virtual visits in locations in which they feel assured of some semblance of privacy.

Continue to: Compensation for telemedicine...

Compensation for telemedicine

Perhaps the biggest barrier to virtual health adoption has been compensation for telemedicine visits. Both commercial payers and CMS have been slow to enact formal policies for telemedicine reimbursement. Because of this, the common misconceptions (that providers cannot be reimbursed for telemedicine appointments or that compensation occurs at a reduced rate) have persisted, making telemedicine economically unappealing.

The good news is that this is changing; legislation in most states is quickly embracing virtual health visits as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic.9 In fact, as of January 1, 2020, telemedicine services are no longer considered “optional” coverage in Medicare Advantage plans.10 Nor are they required to have an additional fee. Instead, CMS now allows telemedicine as a standard, covered benefit in all plans, enabling beneficiaries to seek care from their homes rather than requiring them to go to a health care facility.11 In the past, telemedicine was restricted for use in rural areas or when patients resided a great distance from their health care providers. Starting March 6, 2020, and for the duration of the COVID-19 public health emergency, Medicare will make payment for professional services furnished to beneficiaries in all areas of the country in all settings regardless of location or distance between the patient and the health care provider.12

In addition, since March 15, 2020, CMS has expanded access to telemedicine services for all Medicare beneficiaries—not just those who have been diagnosed with COVID-19.13 The expanded access also applies to pre-COVID-19 coverage from physician offices, skilled nursing facilities, and hospitals. This means that Medicare will now make payments to physicians for telemedicine services provided in any health care facility or in a patient’s home, so that patients do not need to go to the physician’s office.

The facts are that there are parity laws and that commercial payers and CMS are required by state law to reimburse for telemedicine—often at the same rate as that for a comparable in-person visit. On the commercial side, there has been an increase in commercial parity legislation that requires health plans to cover virtual visits in the same way they cover face-to-face services. With the new guidelines for reimbursement, every state and Washington DC has parity laws in place. (To stay abreast of state-by-state changes in virtual health reimbursement, the Center for Connected Health Policy and the Advisory Board Primer are valuable resources. See “Resources.”) As long as the provider performs and documents the elements of history and decision-making, including the time spent counseling, and documents the visit as if a face-to-face visit occurred, then clinicians have a billable evaluation and management (E&M) visit.

Continue to: Virtual services for Medicare patients...

Virtual services for Medicare patients

There are 3 main types of virtual services gynecologists can provide to Medicare patients: Medicare telehealth visits, virtual check-ins, and e-visits.

Medicare telehealth visits. Largely because of the COVID-19 pandemic, Medicare patients may now use telecommunication technology for any services that previously occurred in an in-person communication. The gynecologist must use an interactive audio and video telecommunications system that permits real-time communication between the physician and the patient, and the patient should have a prior established relationship with the gynecologist with whom the telemedicine visit is taking place. The new guidelines indicate that the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) will not conduct audits to ensure that such a prior relationship exists for claims submitted during this public health emergency.14

The Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes for virtual visits using synchronous audio/visual communication are:

- 99201-99295, Office visit for a new patient

- 99211-99215, Office visit for an established patient.

Important modifiers for telemedicine visits include:

- modifier 02 for POS (place of service) for telehealth Medicare

- modifier 95 for commercial payers.

(A list of all available CPT codes for telehealth services from CMS can be found in “Resources.”)

Virtual check-ins. Established Medicare patients may have a brief communication with gynecologists the traditional way using a telephone or via live video. These brief virtual services, usually 5 to 10 minutes in duration, are initiated by the patient. The purpose of the virtual check-in is to determine if an office visit or a test or procedure is indicated.

Medicare pays for these “virtual check-ins” (or brief communication technology-based services) for patients to communicate with their physicians and avoid unnecessary trips to the office. These brief virtual check-ins are only for established patients. If an existing patient contacts the gynecologist’s office to ask a question or determine if an office visit is necessary, the gynecologist may bill for it using code G2012.

E-visits. Established Medicare patients may have non–face-to-face patient-initiated communications with their gynecologists without going to the physician’s office. These services can be billed only when the physician has an established relationship with the patient. The services may be billed using CPT codes 99421 to 99423. Coding for these visits is determined by the length of time the gynecologist spends online with the patient:

- 99421: Online digital evaluation and management service, for an established patient 5 to 10 minutes spent on the virtual visit

- 99422: 11 to 20 minutes

- 99423: ≥ 21 minutes.

Many clinicians want to immediately start the communication process with their patients. Many will avail themselves of the free video communication offered by Google Hangouts, Skype, Facetime, and Facebook Messenger. Since the March 15, 2020, relaxation of the HIPAA restrictions for telemedicine, it is now possible to have a virtual visit with a patient using one of the free, non–HIPAA-compliant connections. This type of visit is no different than a telephone call but with an added video component. Using these free technologies, a gynecologist can have an asynchronous visit with a patient (referred to as the store and forward method of sending information or medical images), which means that the service takes place in one direction with no opportunity for interaction with the patient. Asynchronous visits are akin to video text messages left for the patient. By contrast, a synchronous or real-time video visit with a patient is a 2-way communication that provides medical care without examining the patient.

Using triangulation

There are some downsides to telemedicine visits. First, virtual visits on Skype, FaceTime, and other non–HIPAA-compliant methods are not conducted on an encrypted website. Second, no documentation is created for the doctor-patient encounter. Finally, unless the physician keeps a record of these virtual visits and submits the interactions to the practice coders, there will be no billing and no reimbursement for the visits. In this scenario, physicians are legally responsible for their decision-making, prescription writing, and medical advice, but do not receive compensation for their efforts.

This can be remedied by using “triangulation,” which involves: 1. the physician, 2. the patient, and 3. a scribe or medical assistant who will record the visit. Before initiating the virtual visit using triangulation, it is imperative to ask the patient for permission if your medical assistant (or any other person in the office who functions as a scribe) will be listening to the conversation. It is important to explain that the person is there to take accurate notes and ascertain that the notes are entered into the EHR. Also, the scribe or assistant will record the time, date, and duration of the visit, which is a requirement for billing purposes. The scribe may also ascertain that the visit is properly coded and entered into the practice management system, and that a bill is submitted to the insurance company. By using triangulation, you have documentation that consent was obtained, that the visit took place, that notes were taken, and that the patient’s insurance company will be billed for the visit (see FIGURE 2 for a sample documentation form).

Continue to: Which CPT codes should I use?...

Which CPT codes should I use?

The answer depends on a number of factors, but a good rule of thumb is to use the same codes that you would use for an in-person appointment (CPT codes 99211-99215 for an established patient visit and 99201-99205 for a new patient visit). These are the most common CPT codes for outpatient gynecologic office visits whether they take place face-to-face or as a synchronous virtual visit (via a real-time interactive audio and video telecommunications system).

For example, the reimbursement for code 99213 has a range from $73 to $100. You may wonder how you can achieve the complexity requirements for a level-3 office visit without a physical examination. Whether as a face-to-face or virtual visit, documentation for these encounters requires 2 of 3 of the following components:

- expanded problem-focused history

- expanded problem-focused exam (not accomplished with telemedicine)

- low-complexity medical decision-making OR

- at least 15 minutes spent face to face with the patient if coding is based on time.

If a gynecologist reviews the results of a recent lab test for an estrogen-deficient patient and adjusts the estrogen dosage, writes a prescription, and spends 15 minutes communicating with the patient, he/she has met the complexity requirements for a code 99213. Because Level 3 and 4 visits (99214 and 99215) require a comprehensive physical examination, it is necessary to document the time spent with the patient (code 99214 requires 25 to 39 minutes of consultation and code 99215 requires ≥ 40 minutes).

Some final billing and coding advice

Always confirm telemedicine billing guidelines before beginning to conduct telemedicine visits. Consider starting a phone call to a payer armed with the fact that the payer is required by law to offer parity between telemedicine and face-to-face visits. Then ask which specific billing codes should be used.

Until you and your practice become comfortable with the process of, and the coding and billing for, telemedicine, consider using a telemedicine platform that has a built-in rules engine that offers recommendations for each telemedicine visit based on past claims data. These systems help gynecologists determine which CPT code to use and which modifiers are appropriate for the various insurance companies. In other words, the rules engine helps you submit a clean claim that is less likely to be denied and very likely to be paid. There are some vendors who are so confident that their rules engine will match the service with the proper CPT code and modifier that they guarantee full private payer reimbursement for telemedicine visits, or the vendor will reimburse the claim.

Watch for the third and final installment in this series, which was written with the assistance of 2 attorneys. It will review the legal guidelines for implementing telemedicine in a gynecologic practice and discuss the future of the technology. ●

- COVID-19 and Telehealth Coding Options as of March 20, 2020. https://www.ismanet.org/pdf/COVID-19andTelehealthcodes3-20-2020Updates.pdf.

- Federation of State Medical Boards. US States and Territories Modifying Licensure Requirements for Physicians in Response to COVID-19. Last updated May 26, 2020. https://www.fsmb.org/siteassets/advocacy/pdf/state-emergency-declarations-licensures-requirementscovid-19.pdf.

- Center for Connected Health Policy. Current State Laws and Reimbursement Policies https://www.cchpca.org/telehealth-policy/current-state-laws-and-reimbursement-policies.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. List of Telehealth Services. Updated April 30, 2020. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-General-Information/Telehealth/Telehealth-Codes.

- American Medical Association. AMA quick guide to telemedicinein practice. Updated May 22, 2020. https://www.ama-assn.org/practice-management/digital/ama-quick-guide-telemedicine-practice.

- Eddy N. Patients increasingly trusting of remote care technology. Healthcare IT News. October 22, 2019. https://www.healthcareitnews.com/news/patients-increasingly-trusting-remote-care-technology-says-new-report. Accessed May 26, 2020.

- Welch BM, Harvey J, O’Connell NS, et al. Patient preferences for direct-to-consumer telemedicine services: a nationwide survey. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17:784.

- Tsai JM, Cheng MJ, Tsai HH, et al. Acceptance and resistance of telehealth: the perspective of dual-factor concepts in technology adoption. Int J Inform Manag. 2019;49:34-44.

- Hollander J, Carr BG. Virtually perfect? Telemedicine for COVID-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1679-1681.

- Pew Research Center. Internet and Technology. Mobile Fact Sheet. June 12, 2019. https://www.pewresearch.org /internet/fact-sheet/mobile/. Accessed May 18, 2020.

- American Medical Association. AMA quick guide to telemedicine in practice. https://www.ama-assn.org/ practice-management/digital/ama-quick-guide-telemedicine- practice. Accessed March 20, 2020.

- Center for Connected Health Policy. Federal and state regulation updates. https://www.cchpca.org. Accessed March 20, 2020.

- The White House. Proclamation on declaring a national emergency concerning the novel coronavirus disease (Covid-19) outbreak. March 13, 2020. https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/proclamation-declaring-national-emergency-concerning-novel-coronavirus-disease-covid-19-outbreak/. Accessed May 18, 2020.

- Center for Connected Health Policy. Quick glance state telehealth actions in response to COVID-19. https://www.cchpca.org/sites/default/files/2020-05/STATE%20TELEHEALTH%20ACTIONS%20IN%20RESPONSE%20TO%20COVID%20

OVERVIEW%205.5.2020_0.pdf. AccessedMay 13, 2020. - Medicare.gov. https://www.medicare.gov/sign-up-change -plans/types-of-medicare-health-plans/medicare-advantage-plans/how-do-medicare-advantage-plans-work. Accessed May 13, 2020.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. CMS finalizes policies to bring innovative telehealth benefit to Medicare Advantage. April 5, 2019. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom /press-releases/cms-finalizes-policies-bring-innovative-telehealth-benefit-medicare-advantage. Accessed May 18,2020.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare telemedicine health care provider fact sheet. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/medicare-telemedicine-health-care-provider-fact-sheet. Accessed May 30, 2020.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare telehealth frequently asked questions. https://www.cms.gov/files/document/medicare-telehealth-frequently-asked-questions-faqs-31720.pdf.

- American Hospital Association. Coronavirus update: CMS broadens access to telehealth during Covid-19 public health emergency. https://www.aha.org/advisory/2020-03-17-coronavirus-update-cms-broadens-access-telehealth-during-covid-19-public-health. Accessed May 18, 2020.

- Eddy N. Patients increasingly trusting of remote care technology. Healthcare IT News. October 22, 2019. https://www.healthcareitnews.com/news/patients-increasingly-trusting-remote-care-technology-says-new-report. Accessed May 26, 2020.

- Welch BM, Harvey J, O’Connell NS, et al. Patient preferences for direct-to-consumer telemedicine services: a nationwide survey. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17:784.

- Tsai JM, Cheng MJ, Tsai HH, et al. Acceptance and resistance of telehealth: the perspective of dual-factor concepts in technology adoption. Int J Inform Manag. 2019;49:34-44.

- Hollander J, Carr BG. Virtually perfect? Telemedicine for COVID-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1679-1681.

- Pew Research Center. Internet and Technology. Mobile Fact Sheet. June 12, 2019. https://www.pewresearch.org /internet/fact-sheet/mobile/. Accessed May 18, 2020.

- American Medical Association. AMA quick guide to telemedicine in practice. https://www.ama-assn.org/ practice-management/digital/ama-quick-guide-telemedicine- practice. Accessed March 20, 2020.

- Center for Connected Health Policy. Federal and state regulation updates. https://www.cchpca.org. Accessed March 20, 2020.

- The White House. Proclamation on declaring a national emergency concerning the novel coronavirus disease (Covid-19) outbreak. March 13, 2020. https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/proclamation-declaring-national-emergency-concerning-novel-coronavirus-disease-covid-19-outbreak/. Accessed May 18, 2020.

- Center for Connected Health Policy. Quick glance state telehealth actions in response to COVID-19. https://www.cchpca.org/sites/default/files/2020-05/STATE%20TELEHEALTH%20ACTIONS%20IN%20RESPONSE%20TO%20COVID%20

OVERVIEW%205.5.2020_0.pdf. AccessedMay 13, 2020. - Medicare.gov. https://www.medicare.gov/sign-up-change -plans/types-of-medicare-health-plans/medicare-advantage-plans/how-do-medicare-advantage-plans-work. Accessed May 13, 2020.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. CMS finalizes policies to bring innovative telehealth benefit to Medicare Advantage. April 5, 2019. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom /press-releases/cms-finalizes-policies-bring-innovative-telehealth-benefit-medicare-advantage. Accessed May 18,2020.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare telemedicine health care provider fact sheet. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/medicare-telemedicine-health-care-provider-fact-sheet. Accessed May 30, 2020.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare telehealth frequently asked questions. https://www.cms.gov/files/document/medicare-telehealth-frequently-asked-questions-faqs-31720.pdf.

- American Hospital Association. Coronavirus update: CMS broadens access to telehealth during Covid-19 public health emergency. https://www.aha.org/advisory/2020-03-17-coronavirus-update-cms-broadens-access-telehealth-during-covid-19-public-health. Accessed May 18, 2020.