User login

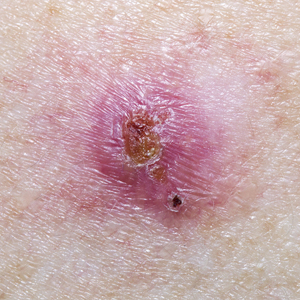

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most common type of skin cancer frequently encountered in both dermatology and primary care settings.1 When biopsies of these neoplasms are performed to confirm the diagnosis, pathology reports may indicate positive or negative margin status. No guidelines exist for reporting biopsy margin status for BCC, resulting in varied reporting practices among dermatopathologists. Furthermore, the terminology used to describe margin status can be ambiguous and differs among pathologists; language such as “approaches the margin” or “margins appear free” may be used, with nonuniform interpretation between pathologists and providers, leading to variability in patient management.2

When interpreting a negative margin status on a pathology report, one must question if the BCC extends beyond the margin in unexamined sections of the specimen, which could be the result of an irregular tumor growth pattern or tissue processing. It has been estimated that less than 2% of the peripheral surgical margin is ultimately examined when serial cross-sections are prepared histologically (the bread loaf technique). However, this estimation would depend on several variables, including the number and thickness of sections and the amount of tissue discarded during processing.3 Importantly, reports of a false-negative margin could lead both the clinician and patient to believe that the neoplasm has been completely removed, which could have serious consequences.

Our study sought to determine the reliability of negative biopsy margin status for BCC. We examined BCC biopsy specimens initially determined to have uninvolved margins on routine tissue processing and determined the proportion with truly negative margins after complete tissue block sectioning of the initial biopsy specimen. We felt this technique was a more accurate measurement of true margin status than examination of a re-excision specimen. We also identified any factors that were predictive of positive true margins.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective study evaluating tissue samples collected at Geisinger Health System (Danville, Pennsylvania) from January to December 2016. Specimens were queried via the electronic database system at our institution (CoPath). We included BCC biopsy specimens with negative histologic margins on initial assessment that subsequently had block exhaust levels routinely ordered. These levels are cut every 100 to 150 µm, generating approximately 8 glass slides. We excluded all tumors that did not fit these criteria as well as those in patients younger than 18 years. Data collection was performed utilizing specimen pathology reports in addition to the note from the corresponding clinician office visit from the institution’s electronic medical record (Epic). Appropriate statistical calculations were performed. This study was approved by an institutional review board at our institution, which is required for all research involving human participants. This served to ensure the proper review and storage of patients’ protected health information.

Results

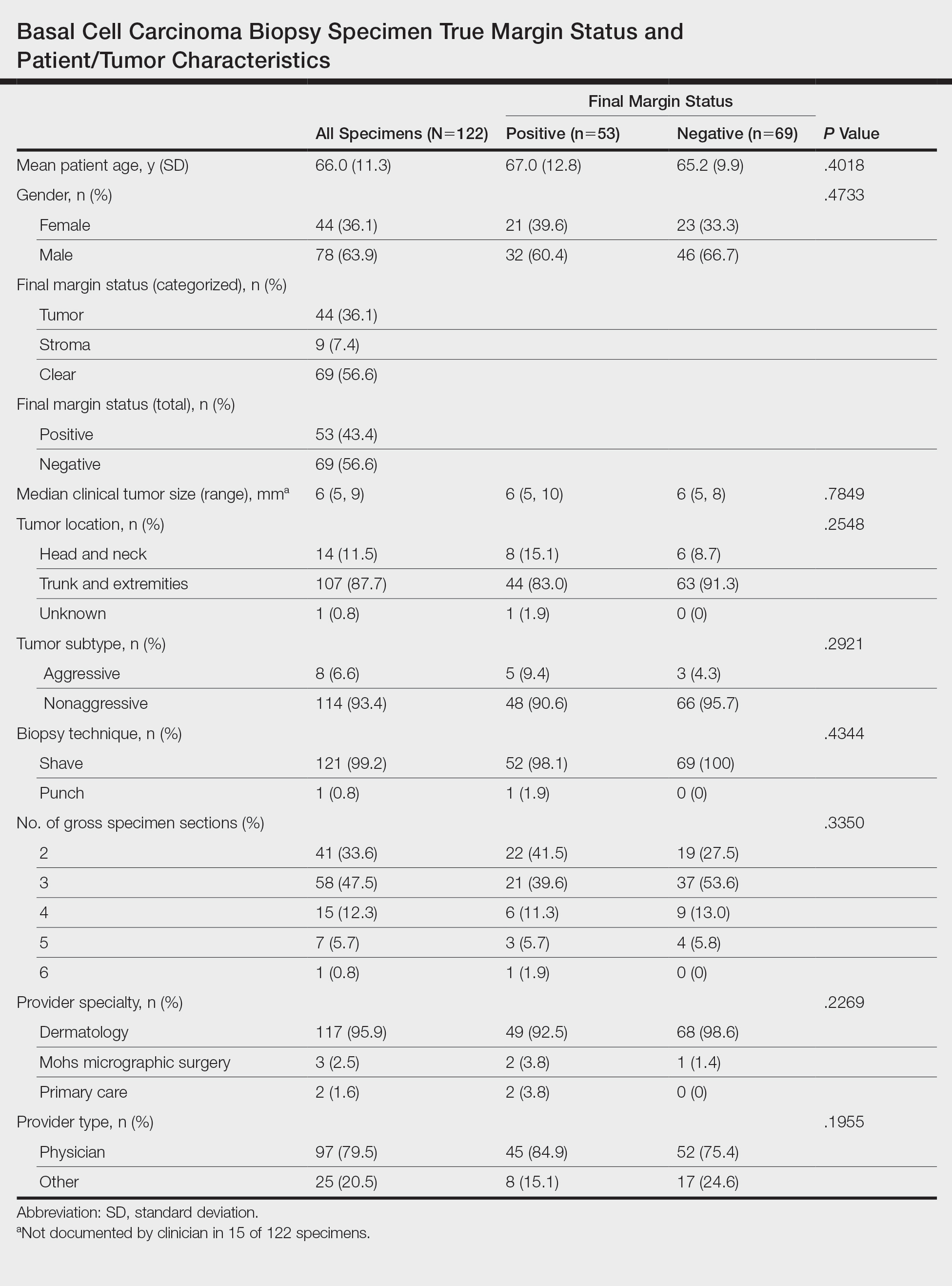

The search yielded a total of 122 specimens from 104 patients after appropriate exclusions. We examined a total of 122 BCC biopsy specimens with negative initial margins: 121 (99.2%) shave biopsies and 1 (0.8%) punch biopsy. Of 122 specimens with negative initial margins, 53 (43.4%) were found to have a truly positive margin based on the presence of either tumor or stroma at the lateral or deep tissue edge after complete tissue block sectioning. Sixty-nine (56.6%) specimens had clear margins and were categorized as truly negative after complete tissue block sectioning. Specimens with positive and negative final margin status did not differ significantly with respect to patient age; gender; biopsy technique; number of gross specimen sections; or tumor characteristics, including location, size, and subtype (Table)(P>.05).

We also examined the type of treatment performed, which varied and included curettage, electrodesiccation and curettage, excision, and Mohs micrographic surgery. Clinicians, who were not made aware of the exhaust level protocol, chose not to pursue further treatment in 6 (4.9%) of the cases because of negative biopsy margins. Four (66.7%) of the 6 providers were physicians, and 2 (33.3%) were advanced practitioners. All of the providers practiced within the Department of Dermatology.

Comment

Our findings support prior smaller studies investigating this topic. A prospective study by Schnebelen et al4 examined 27 BCC biopsy specimens and found that 8 (30%) were erroneously classified as negative on routine examination. This study similarly determined true margin status by assessing the margins at complete tissue block exhaustion.4 Willardson et al5 also demonstrated the poor predictive value of margin status based on the presence of residual BCC in subsequent excisions. They found that 34 (24%) of 143 cases with negative biopsy margins contained residual tumor in the corresponding excision.5

Our study revealed that almost half of BCC biopsy specimens that had negative histologic margins with routine sectioning had truly positive margins on complete block exhaustion. This finding was independent of multiple factors, including tumor subtype, indicating that even nonaggressive tumors are prone to false-negative margin reports. We also found that reports of negative margins persuaded some clinicians to forgo definitive treatment. This study serves to remind clinicians of the limitations of margin assessment and provides impetus for dermatopathologists to consider modifying how margin status is reported.

Limitations of this study include a small number of cases and limited generalizability. Institutions that routinely examine more levels of each biopsy specimen may be less likely to erroneously categorize a positive margin as negative. Furthermore, despite exhausting the tissue block, we still may have underestimated the number of cases with truly positive margins, as this method inherently does not allow for complete margin examination.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Geisinger Department of Dermatopathology and the Geisinger Biostatistics & Research Data Core (Danville, Pennsylvania) for their assistance with our project.

- Lukowiak TM, Aizman L, Perz A, et al. Association of age, sex, race, and geographic region with variation of the ratio of basal cell to squamous cell carcinomas in the United States. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:1149-1276.

- Abide JM, Nahai F, Bennett RG. The meaning of surgical margins. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1984;73:492-497.

- Kimyai-Asadi A, Goldberg LH, Jih MH. Accuracy of serial transverse cross-sections in detecting residual basal cell carcinoma at the surgical margins of an elliptical excision specimen. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:469-473.

- Schnebelen AM, Gardner JM, Shalin SC. Margin status in shave biopsies of nonmelanoma skin cancers: is it worth reporting? Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2016;140:678-681.

- Willardson HB, Lombardo J, Raines M, et al. Predictive value of basal cell carcinoma biopsies with negative margins: a retrospective cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:42-46.

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most common type of skin cancer frequently encountered in both dermatology and primary care settings.1 When biopsies of these neoplasms are performed to confirm the diagnosis, pathology reports may indicate positive or negative margin status. No guidelines exist for reporting biopsy margin status for BCC, resulting in varied reporting practices among dermatopathologists. Furthermore, the terminology used to describe margin status can be ambiguous and differs among pathologists; language such as “approaches the margin” or “margins appear free” may be used, with nonuniform interpretation between pathologists and providers, leading to variability in patient management.2

When interpreting a negative margin status on a pathology report, one must question if the BCC extends beyond the margin in unexamined sections of the specimen, which could be the result of an irregular tumor growth pattern or tissue processing. It has been estimated that less than 2% of the peripheral surgical margin is ultimately examined when serial cross-sections are prepared histologically (the bread loaf technique). However, this estimation would depend on several variables, including the number and thickness of sections and the amount of tissue discarded during processing.3 Importantly, reports of a false-negative margin could lead both the clinician and patient to believe that the neoplasm has been completely removed, which could have serious consequences.

Our study sought to determine the reliability of negative biopsy margin status for BCC. We examined BCC biopsy specimens initially determined to have uninvolved margins on routine tissue processing and determined the proportion with truly negative margins after complete tissue block sectioning of the initial biopsy specimen. We felt this technique was a more accurate measurement of true margin status than examination of a re-excision specimen. We also identified any factors that were predictive of positive true margins.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective study evaluating tissue samples collected at Geisinger Health System (Danville, Pennsylvania) from January to December 2016. Specimens were queried via the electronic database system at our institution (CoPath). We included BCC biopsy specimens with negative histologic margins on initial assessment that subsequently had block exhaust levels routinely ordered. These levels are cut every 100 to 150 µm, generating approximately 8 glass slides. We excluded all tumors that did not fit these criteria as well as those in patients younger than 18 years. Data collection was performed utilizing specimen pathology reports in addition to the note from the corresponding clinician office visit from the institution’s electronic medical record (Epic). Appropriate statistical calculations were performed. This study was approved by an institutional review board at our institution, which is required for all research involving human participants. This served to ensure the proper review and storage of patients’ protected health information.

Results

The search yielded a total of 122 specimens from 104 patients after appropriate exclusions. We examined a total of 122 BCC biopsy specimens with negative initial margins: 121 (99.2%) shave biopsies and 1 (0.8%) punch biopsy. Of 122 specimens with negative initial margins, 53 (43.4%) were found to have a truly positive margin based on the presence of either tumor or stroma at the lateral or deep tissue edge after complete tissue block sectioning. Sixty-nine (56.6%) specimens had clear margins and were categorized as truly negative after complete tissue block sectioning. Specimens with positive and negative final margin status did not differ significantly with respect to patient age; gender; biopsy technique; number of gross specimen sections; or tumor characteristics, including location, size, and subtype (Table)(P>.05).

We also examined the type of treatment performed, which varied and included curettage, electrodesiccation and curettage, excision, and Mohs micrographic surgery. Clinicians, who were not made aware of the exhaust level protocol, chose not to pursue further treatment in 6 (4.9%) of the cases because of negative biopsy margins. Four (66.7%) of the 6 providers were physicians, and 2 (33.3%) were advanced practitioners. All of the providers practiced within the Department of Dermatology.

Comment

Our findings support prior smaller studies investigating this topic. A prospective study by Schnebelen et al4 examined 27 BCC biopsy specimens and found that 8 (30%) were erroneously classified as negative on routine examination. This study similarly determined true margin status by assessing the margins at complete tissue block exhaustion.4 Willardson et al5 also demonstrated the poor predictive value of margin status based on the presence of residual BCC in subsequent excisions. They found that 34 (24%) of 143 cases with negative biopsy margins contained residual tumor in the corresponding excision.5

Our study revealed that almost half of BCC biopsy specimens that had negative histologic margins with routine sectioning had truly positive margins on complete block exhaustion. This finding was independent of multiple factors, including tumor subtype, indicating that even nonaggressive tumors are prone to false-negative margin reports. We also found that reports of negative margins persuaded some clinicians to forgo definitive treatment. This study serves to remind clinicians of the limitations of margin assessment and provides impetus for dermatopathologists to consider modifying how margin status is reported.

Limitations of this study include a small number of cases and limited generalizability. Institutions that routinely examine more levels of each biopsy specimen may be less likely to erroneously categorize a positive margin as negative. Furthermore, despite exhausting the tissue block, we still may have underestimated the number of cases with truly positive margins, as this method inherently does not allow for complete margin examination.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Geisinger Department of Dermatopathology and the Geisinger Biostatistics & Research Data Core (Danville, Pennsylvania) for their assistance with our project.

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most common type of skin cancer frequently encountered in both dermatology and primary care settings.1 When biopsies of these neoplasms are performed to confirm the diagnosis, pathology reports may indicate positive or negative margin status. No guidelines exist for reporting biopsy margin status for BCC, resulting in varied reporting practices among dermatopathologists. Furthermore, the terminology used to describe margin status can be ambiguous and differs among pathologists; language such as “approaches the margin” or “margins appear free” may be used, with nonuniform interpretation between pathologists and providers, leading to variability in patient management.2

When interpreting a negative margin status on a pathology report, one must question if the BCC extends beyond the margin in unexamined sections of the specimen, which could be the result of an irregular tumor growth pattern or tissue processing. It has been estimated that less than 2% of the peripheral surgical margin is ultimately examined when serial cross-sections are prepared histologically (the bread loaf technique). However, this estimation would depend on several variables, including the number and thickness of sections and the amount of tissue discarded during processing.3 Importantly, reports of a false-negative margin could lead both the clinician and patient to believe that the neoplasm has been completely removed, which could have serious consequences.

Our study sought to determine the reliability of negative biopsy margin status for BCC. We examined BCC biopsy specimens initially determined to have uninvolved margins on routine tissue processing and determined the proportion with truly negative margins after complete tissue block sectioning of the initial biopsy specimen. We felt this technique was a more accurate measurement of true margin status than examination of a re-excision specimen. We also identified any factors that were predictive of positive true margins.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective study evaluating tissue samples collected at Geisinger Health System (Danville, Pennsylvania) from January to December 2016. Specimens were queried via the electronic database system at our institution (CoPath). We included BCC biopsy specimens with negative histologic margins on initial assessment that subsequently had block exhaust levels routinely ordered. These levels are cut every 100 to 150 µm, generating approximately 8 glass slides. We excluded all tumors that did not fit these criteria as well as those in patients younger than 18 years. Data collection was performed utilizing specimen pathology reports in addition to the note from the corresponding clinician office visit from the institution’s electronic medical record (Epic). Appropriate statistical calculations were performed. This study was approved by an institutional review board at our institution, which is required for all research involving human participants. This served to ensure the proper review and storage of patients’ protected health information.

Results

The search yielded a total of 122 specimens from 104 patients after appropriate exclusions. We examined a total of 122 BCC biopsy specimens with negative initial margins: 121 (99.2%) shave biopsies and 1 (0.8%) punch biopsy. Of 122 specimens with negative initial margins, 53 (43.4%) were found to have a truly positive margin based on the presence of either tumor or stroma at the lateral or deep tissue edge after complete tissue block sectioning. Sixty-nine (56.6%) specimens had clear margins and were categorized as truly negative after complete tissue block sectioning. Specimens with positive and negative final margin status did not differ significantly with respect to patient age; gender; biopsy technique; number of gross specimen sections; or tumor characteristics, including location, size, and subtype (Table)(P>.05).

We also examined the type of treatment performed, which varied and included curettage, electrodesiccation and curettage, excision, and Mohs micrographic surgery. Clinicians, who were not made aware of the exhaust level protocol, chose not to pursue further treatment in 6 (4.9%) of the cases because of negative biopsy margins. Four (66.7%) of the 6 providers were physicians, and 2 (33.3%) were advanced practitioners. All of the providers practiced within the Department of Dermatology.

Comment

Our findings support prior smaller studies investigating this topic. A prospective study by Schnebelen et al4 examined 27 BCC biopsy specimens and found that 8 (30%) were erroneously classified as negative on routine examination. This study similarly determined true margin status by assessing the margins at complete tissue block exhaustion.4 Willardson et al5 also demonstrated the poor predictive value of margin status based on the presence of residual BCC in subsequent excisions. They found that 34 (24%) of 143 cases with negative biopsy margins contained residual tumor in the corresponding excision.5

Our study revealed that almost half of BCC biopsy specimens that had negative histologic margins with routine sectioning had truly positive margins on complete block exhaustion. This finding was independent of multiple factors, including tumor subtype, indicating that even nonaggressive tumors are prone to false-negative margin reports. We also found that reports of negative margins persuaded some clinicians to forgo definitive treatment. This study serves to remind clinicians of the limitations of margin assessment and provides impetus for dermatopathologists to consider modifying how margin status is reported.

Limitations of this study include a small number of cases and limited generalizability. Institutions that routinely examine more levels of each biopsy specimen may be less likely to erroneously categorize a positive margin as negative. Furthermore, despite exhausting the tissue block, we still may have underestimated the number of cases with truly positive margins, as this method inherently does not allow for complete margin examination.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Geisinger Department of Dermatopathology and the Geisinger Biostatistics & Research Data Core (Danville, Pennsylvania) for their assistance with our project.

- Lukowiak TM, Aizman L, Perz A, et al. Association of age, sex, race, and geographic region with variation of the ratio of basal cell to squamous cell carcinomas in the United States. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:1149-1276.

- Abide JM, Nahai F, Bennett RG. The meaning of surgical margins. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1984;73:492-497.

- Kimyai-Asadi A, Goldberg LH, Jih MH. Accuracy of serial transverse cross-sections in detecting residual basal cell carcinoma at the surgical margins of an elliptical excision specimen. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:469-473.

- Schnebelen AM, Gardner JM, Shalin SC. Margin status in shave biopsies of nonmelanoma skin cancers: is it worth reporting? Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2016;140:678-681.

- Willardson HB, Lombardo J, Raines M, et al. Predictive value of basal cell carcinoma biopsies with negative margins: a retrospective cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:42-46.

- Lukowiak TM, Aizman L, Perz A, et al. Association of age, sex, race, and geographic region with variation of the ratio of basal cell to squamous cell carcinomas in the United States. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:1149-1276.

- Abide JM, Nahai F, Bennett RG. The meaning of surgical margins. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1984;73:492-497.

- Kimyai-Asadi A, Goldberg LH, Jih MH. Accuracy of serial transverse cross-sections in detecting residual basal cell carcinoma at the surgical margins of an elliptical excision specimen. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:469-473.

- Schnebelen AM, Gardner JM, Shalin SC. Margin status in shave biopsies of nonmelanoma skin cancers: is it worth reporting? Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2016;140:678-681.

- Willardson HB, Lombardo J, Raines M, et al. Predictive value of basal cell carcinoma biopsies with negative margins: a retrospective cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:42-46.

Practice Points

- Clinicians must recognize the limitations of margin assessment of biopsy specimens and not rely on margin status to dictate treatment.

- Dermatopathologists should consider modifying how margin status is reported, either by omitting it or clarifying its limitations on the pathology report.