User login

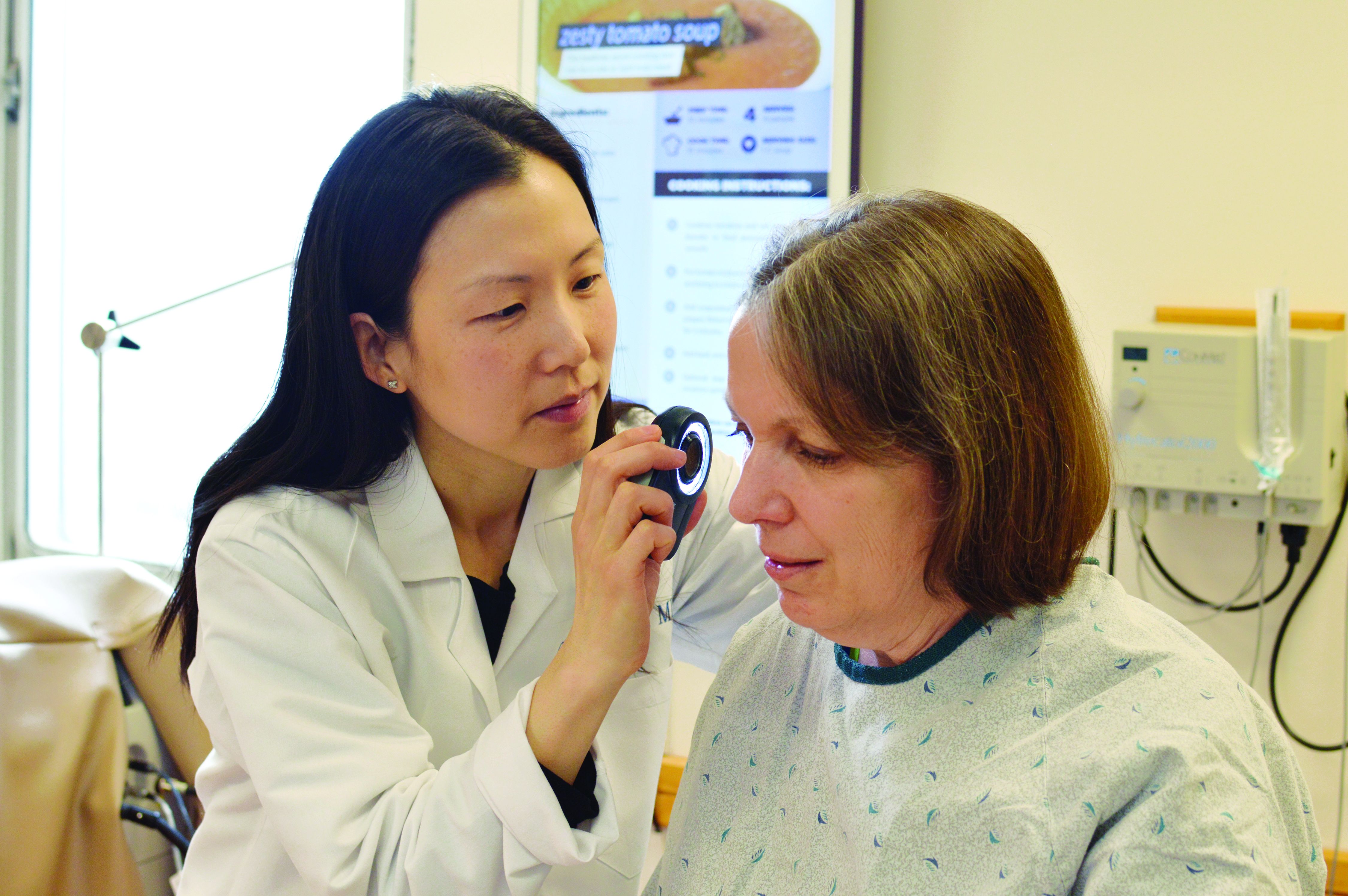

CHICAGO – Medicine, perhaps uniquely among the highly skilled professions, requires the practitioner to use his or her senses on a daily basis. Dermatologists and dermatopathologists rely on visual skills – pattern recognition, gestalt or “gut” first impressions, and step-by-step deliberations – to care for their patients.

But, like all human cognitive processes, visual assessments are error prone. The same brains that can parse a field of blue and pink dots to discern melanoma on a slide are also capable of glaring errors of omission: All too often, the brain follows a cognitive path for the wrong reasons.

Christine Ko, MD, professor of dermatology and pathology at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., became interested in the meta-cognition of her trade; that is, she sought to learn how to think about the thinking that’s needed to be a dermatologist or a dermatopathologist.

In a wide-ranging discussion at the summer meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology, Dr. Ko took attendees through The path led through lessons learned from cognitive science to the fine arts, to lessons learned from other visually oriented medical disciplines.

“Deliberate practice in dermatology is augmented by knowledge of specific cognitive principles that affect visual perception,” Dr. Ko said at the meeting. “This session will open your eyes to the world of visual intelligence that underlies expert dermatologic diagnosis.”

To begin with, what constitutes deliberate practice of dermatology or dermatopathology? Practically speaking, seeing many patients (or reading many slides) builds the base for true expertise, she noted. Physicians continue to hone their learning through independent reading, journal clubs, and meeting attendance, and seek opportunities for deliberate review of what’s still unknown, as in grand rounds – where, ideally, feedback is instantaneous.

Deliberate practice, though, should also include honing visual skills. “We find only the world we look for,” said Dr. Ko, quoting Henry David Thoreau. To sharpen the pattern recognition and keen observation that underpin dermatology and dermatopathology, she said, “We can train the brain.”

Radiology, another medical discipline that requires sustained visual attention, has a significant body of literature addressing common visually-related cognitive errors, she pointed out. In radiology, it’s been shown that deliberate observation of visual art can improve accuracy of reading films.

She observed that dermatologists and dermatopathologists need to think in color, so they may need to develop slightly different visual skills from radiologists who largely see a gray-scale world while they’re working.

Cognitive psychology also offers lessons. One seminal paper, “The invisible gorilla strikes again: Sustained inattentional blindness in expert observers,” issues a stern admonition: “[A] high level of expertise does not immunize individuals against inherent limitations of human attention imperception” (Psychol Sci. 2013 Sep;24[9]:1848-53). Inattentional blindness, Dr. Ko explained, occurs when “what we are focused on filters the world around us aggressively.” First author Trafton Drew, PhD, and his colleagues added: “Researchers should seek better understanding of these limits, so that medical and other man-made search tasks could be designed in ways that reduce the consequences of these limitations.”

How to overcome these limitations? “Concentrate on the camouflaged,” said Dr. Ko, taking a page – literally – from “Visual Intelligence: Sharpen Your Perception, Change Your Life” (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2016), a book by Amy Herman, JD. Ms. Herman devised the mnemonic “COBRA” to identify several steps that can prevent cognitive error from visual observation:

- Concentrating on the camouflaged, for dermatologists, might mean just looking again and focusing on the less-obvious. But, Dr. Ko said, it might mean turning your attention elsewhere for a while, and then looking back at the area in question. Or the patient or slide – or even the examiner – might need repositioning, for a fresh perspective.

- Taking One thing at a time. For dermatologists and dermatopathologists, this means sorting out the who, what, when, and where of the problem at hand. “ ‘Who’ is always the patient,” said Dr. Ko. “But part of ‘who’ is also us; if we’re tired, it can affect things.” There are many ‘whats’ to consider about the presenting problem or the tissue sample: What is the configuration? The architecture? What is the morphology? What’s the color, or cell type? Are there secondary changes? Does the tissue fit into the general category of a benign, or a malignant, lesion? The examination should include a methodical search for clues as to the duration of the problem – Is it acute or chronic? Finally, the ‘where’ – distribution on the body, or of a specimen on a slide, should also be noted.

- Take a Break. This means resting the eye and the mind by turning attention elsewhere, or shifting to light conversation with the patient, or just stepping away from the microscope for a time.

- Realign your expectations. What might you have missed? Is the patient telling you something in the history? Is it possible this is an uncommon presentation of a common condition, rather than a “zebra”?

- Ask someone else to look with you. Sometimes there’s no substitute for another set of eyes, and another brain working on the problem.

A congruent perspective comes from Daniel Kahneman, PhD, a Nobel Prize–winning economist. In 2011, he published a work addressing meta-cognition, called “Thinking Fast and Slow.”

From Dr. Kahneman’s work, Dr. Ko says dermatologists can learn to recognize two complementary ways of thinking. The “fast” system engages multiple cognitive processes to create a gestalt, “gut” impression. “Slow” thinking, in Dr. Kahneman’s construct, is deliberative, methodical, and traditionally thought of as “logical.” However, it would be a mistake to think of these two systems as existing in opposition, or even as completely separate from each other. “It’s sort of just a linguistic tool for us to have something to call it,” she said.

A “fast” analysis will involve some key elements of visual assessment, said Dr. Ko. Figure-ground separation is a basic element of visual assessment and is vital for the work of the dermatopathologist. “Choosing the wrong ‘figure’ may lead to cognitive error,” she explained, citing work on visual perception among dermatopathologists that found that figure-ground separation errors account for a significant number of diagnostic errors.

Other contributors to “fast” thinking include one’s own experience, seeing just a part of the image, judging which elements are close to each other and similar, and noting color contrasts and gradations.

The “slow” assessment is where deliberate practice comes in, said Dr. Ko. Here, the physician goes further, “to check for pertinent positive and negative evidence” for the initial diagnosis. “Play devil’s advocate, and ask yourself why it couldn’t be something else,” she said.

Eve Lowenstein, MD, PhD, is a dermatologist who publishes about heuristics in dermatology. She and Dr. Ko have collaborated to create a forthcoming two-part continuing medical education article in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology (JAAD) about cognitive biases and errors in dermatology.

Dr. Lowenstein’s perspective, recently elucidated in two British Journal of Dermatology articles, acknowledges that while “ubiquitous cognitive and visual heuristics can enhance diagnostic speed, they also create pitfalls and thinking traps that introduce significant variation in the diagnostic process,” she and her coauthor Richard Sidlow, MD, of Staten Island (N.Y.) University Hospital, wrote in the abstract accompanying the first article (Br J Dermatol. 2018 Dec;179[6]:1263-9). The second article was published in the same issue (Br J Dermatol. 2018 Dec;179[6]:1270-6).

Heuristics are cognitive shortcuts used to speed decision-making that build on what’s already known, as in the “fast” thinking of Dr. Kahneman’s paradigm. Though heuristics are used in all sorts of professions with high cognitive loads, there’s a risk when physicians get too comfortable with the shortcuts. Speaking frankly in an interview, Dr. Lowenstein said, “intellectual presumptiveness or overconfidence, which is a natural human tendency, can result in oversights and missing information critical to making a correct diagnosis, and premature closure on the wrong diagnosis.”

Diagnostic error, Dr. Lowenstein pointed out, can also result from an “attitudinal overconfidence,” which can come from complacency – being satisfied with the status quo or a lack of intellectual curiosity – or arrogance, she said.

“Complacency is the opposite of what is needed in medicine: an attitude where one cannot know enough. The pursuit of knowledge goes on, ever vigilantly. The world changes; practitioners must keep up and cannot fall back on their knowledge,” she said.

This kind of attitudinal and cognitive humility, she said, is essential to practicing quality care in dermatology. Having practical strategies to improve diagnosis, especially in difficult cases, can make a big difference. For Dr. Lowenstein, one of these tactics is to keep an error diary. “It has been said that ‘the only way to safeguard against error is to embrace it,’ ” she said, quoting Kathryn Schulz in “Being Wrong.” “Unfortunately, we learn some of our most profound lessons from our errors.”

By recording and tracking her own errors, not only is she able to see her own cognitive blind spots through meta-cognition – thinking about how we think – but she’s also able to share these lessons in her teaching. “Some of my best teaching tools for residents are from everything I have screwed up,” said Dr. Lowenstein, director of medical dermatology at the State University of New York Downstate Medical Center and Kings County Hospital, Brooklyn, N.Y.

Another useful tip is simply “to put what you see into words,” when the presentation is confusing or the diagnosis doesn’t quite fit, she added.

“Transforming signs and findings into semantics triggers a differential diagnosis, which is especially useful when we are diagnostically stumped. Studies have found that successful diagnosticians use twice as many semantic qualifiers as the physicians who were diagnostically incorrect.” This is especially significant in visual fields like dermatology, where a single word can paint a picture and rapidly focus a diagnostic search. “We often undervalue this function and relegate it to students starting out in the field,” Dr. Lowenstein said.

Cognitive shortcuts such as diagnostic heuristics all have blind spots, and diagnostic errors tend to fall in these blind spots, she added. “We tend to ignore them. In driving, we adapt to the use of rear and side view mirrors in order to drive safely. Similarly, in diagnostics, alternative views on the data can be very helpful. For example, when faced with difficult cases, take a time out to reanalyze the information without framing or context. Use systematic approaches, such as running down a papulosquamous differential diagnosis. Ask yourself: What can’t be explained in the picture? What doesn’t fit? Think in terms of probabilities – a rare presentation of a common disease is more likely than a rare disease,” she said.

Finally, asking for advice or second opinions from peers, whether by face-to-face discussion or via an online chat site, within the department or appealing to broader groups such as hospitalist dermatologist chat groups, can be helpful with difficult cases. Another strategy is simply to email an expert. Dr. Lowenstein said she’s had great success reaching out to authors of relevant papers by email. Most of her peers, she said, are interested in unusual cases and happy to help.

Dr. Ko has authored or coauthored books on the topics of visual recognition in dermatology and dermatopathology. They are “Dermatology: Visual Recognition and Case Reviews,” and “Dermatopathology: Diagnosis by First Impression.” Dr. Lowenstein reported that she has no conflicts of interest.

CHICAGO – Medicine, perhaps uniquely among the highly skilled professions, requires the practitioner to use his or her senses on a daily basis. Dermatologists and dermatopathologists rely on visual skills – pattern recognition, gestalt or “gut” first impressions, and step-by-step deliberations – to care for their patients.

But, like all human cognitive processes, visual assessments are error prone. The same brains that can parse a field of blue and pink dots to discern melanoma on a slide are also capable of glaring errors of omission: All too often, the brain follows a cognitive path for the wrong reasons.

Christine Ko, MD, professor of dermatology and pathology at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., became interested in the meta-cognition of her trade; that is, she sought to learn how to think about the thinking that’s needed to be a dermatologist or a dermatopathologist.

In a wide-ranging discussion at the summer meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology, Dr. Ko took attendees through The path led through lessons learned from cognitive science to the fine arts, to lessons learned from other visually oriented medical disciplines.

“Deliberate practice in dermatology is augmented by knowledge of specific cognitive principles that affect visual perception,” Dr. Ko said at the meeting. “This session will open your eyes to the world of visual intelligence that underlies expert dermatologic diagnosis.”

To begin with, what constitutes deliberate practice of dermatology or dermatopathology? Practically speaking, seeing many patients (or reading many slides) builds the base for true expertise, she noted. Physicians continue to hone their learning through independent reading, journal clubs, and meeting attendance, and seek opportunities for deliberate review of what’s still unknown, as in grand rounds – where, ideally, feedback is instantaneous.

Deliberate practice, though, should also include honing visual skills. “We find only the world we look for,” said Dr. Ko, quoting Henry David Thoreau. To sharpen the pattern recognition and keen observation that underpin dermatology and dermatopathology, she said, “We can train the brain.”

Radiology, another medical discipline that requires sustained visual attention, has a significant body of literature addressing common visually-related cognitive errors, she pointed out. In radiology, it’s been shown that deliberate observation of visual art can improve accuracy of reading films.

She observed that dermatologists and dermatopathologists need to think in color, so they may need to develop slightly different visual skills from radiologists who largely see a gray-scale world while they’re working.

Cognitive psychology also offers lessons. One seminal paper, “The invisible gorilla strikes again: Sustained inattentional blindness in expert observers,” issues a stern admonition: “[A] high level of expertise does not immunize individuals against inherent limitations of human attention imperception” (Psychol Sci. 2013 Sep;24[9]:1848-53). Inattentional blindness, Dr. Ko explained, occurs when “what we are focused on filters the world around us aggressively.” First author Trafton Drew, PhD, and his colleagues added: “Researchers should seek better understanding of these limits, so that medical and other man-made search tasks could be designed in ways that reduce the consequences of these limitations.”

How to overcome these limitations? “Concentrate on the camouflaged,” said Dr. Ko, taking a page – literally – from “Visual Intelligence: Sharpen Your Perception, Change Your Life” (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2016), a book by Amy Herman, JD. Ms. Herman devised the mnemonic “COBRA” to identify several steps that can prevent cognitive error from visual observation:

- Concentrating on the camouflaged, for dermatologists, might mean just looking again and focusing on the less-obvious. But, Dr. Ko said, it might mean turning your attention elsewhere for a while, and then looking back at the area in question. Or the patient or slide – or even the examiner – might need repositioning, for a fresh perspective.

- Taking One thing at a time. For dermatologists and dermatopathologists, this means sorting out the who, what, when, and where of the problem at hand. “ ‘Who’ is always the patient,” said Dr. Ko. “But part of ‘who’ is also us; if we’re tired, it can affect things.” There are many ‘whats’ to consider about the presenting problem or the tissue sample: What is the configuration? The architecture? What is the morphology? What’s the color, or cell type? Are there secondary changes? Does the tissue fit into the general category of a benign, or a malignant, lesion? The examination should include a methodical search for clues as to the duration of the problem – Is it acute or chronic? Finally, the ‘where’ – distribution on the body, or of a specimen on a slide, should also be noted.

- Take a Break. This means resting the eye and the mind by turning attention elsewhere, or shifting to light conversation with the patient, or just stepping away from the microscope for a time.

- Realign your expectations. What might you have missed? Is the patient telling you something in the history? Is it possible this is an uncommon presentation of a common condition, rather than a “zebra”?

- Ask someone else to look with you. Sometimes there’s no substitute for another set of eyes, and another brain working on the problem.

A congruent perspective comes from Daniel Kahneman, PhD, a Nobel Prize–winning economist. In 2011, he published a work addressing meta-cognition, called “Thinking Fast and Slow.”

From Dr. Kahneman’s work, Dr. Ko says dermatologists can learn to recognize two complementary ways of thinking. The “fast” system engages multiple cognitive processes to create a gestalt, “gut” impression. “Slow” thinking, in Dr. Kahneman’s construct, is deliberative, methodical, and traditionally thought of as “logical.” However, it would be a mistake to think of these two systems as existing in opposition, or even as completely separate from each other. “It’s sort of just a linguistic tool for us to have something to call it,” she said.

A “fast” analysis will involve some key elements of visual assessment, said Dr. Ko. Figure-ground separation is a basic element of visual assessment and is vital for the work of the dermatopathologist. “Choosing the wrong ‘figure’ may lead to cognitive error,” she explained, citing work on visual perception among dermatopathologists that found that figure-ground separation errors account for a significant number of diagnostic errors.

Other contributors to “fast” thinking include one’s own experience, seeing just a part of the image, judging which elements are close to each other and similar, and noting color contrasts and gradations.

The “slow” assessment is where deliberate practice comes in, said Dr. Ko. Here, the physician goes further, “to check for pertinent positive and negative evidence” for the initial diagnosis. “Play devil’s advocate, and ask yourself why it couldn’t be something else,” she said.

Eve Lowenstein, MD, PhD, is a dermatologist who publishes about heuristics in dermatology. She and Dr. Ko have collaborated to create a forthcoming two-part continuing medical education article in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology (JAAD) about cognitive biases and errors in dermatology.

Dr. Lowenstein’s perspective, recently elucidated in two British Journal of Dermatology articles, acknowledges that while “ubiquitous cognitive and visual heuristics can enhance diagnostic speed, they also create pitfalls and thinking traps that introduce significant variation in the diagnostic process,” she and her coauthor Richard Sidlow, MD, of Staten Island (N.Y.) University Hospital, wrote in the abstract accompanying the first article (Br J Dermatol. 2018 Dec;179[6]:1263-9). The second article was published in the same issue (Br J Dermatol. 2018 Dec;179[6]:1270-6).

Heuristics are cognitive shortcuts used to speed decision-making that build on what’s already known, as in the “fast” thinking of Dr. Kahneman’s paradigm. Though heuristics are used in all sorts of professions with high cognitive loads, there’s a risk when physicians get too comfortable with the shortcuts. Speaking frankly in an interview, Dr. Lowenstein said, “intellectual presumptiveness or overconfidence, which is a natural human tendency, can result in oversights and missing information critical to making a correct diagnosis, and premature closure on the wrong diagnosis.”

Diagnostic error, Dr. Lowenstein pointed out, can also result from an “attitudinal overconfidence,” which can come from complacency – being satisfied with the status quo or a lack of intellectual curiosity – or arrogance, she said.

“Complacency is the opposite of what is needed in medicine: an attitude where one cannot know enough. The pursuit of knowledge goes on, ever vigilantly. The world changes; practitioners must keep up and cannot fall back on their knowledge,” she said.

This kind of attitudinal and cognitive humility, she said, is essential to practicing quality care in dermatology. Having practical strategies to improve diagnosis, especially in difficult cases, can make a big difference. For Dr. Lowenstein, one of these tactics is to keep an error diary. “It has been said that ‘the only way to safeguard against error is to embrace it,’ ” she said, quoting Kathryn Schulz in “Being Wrong.” “Unfortunately, we learn some of our most profound lessons from our errors.”

By recording and tracking her own errors, not only is she able to see her own cognitive blind spots through meta-cognition – thinking about how we think – but she’s also able to share these lessons in her teaching. “Some of my best teaching tools for residents are from everything I have screwed up,” said Dr. Lowenstein, director of medical dermatology at the State University of New York Downstate Medical Center and Kings County Hospital, Brooklyn, N.Y.

Another useful tip is simply “to put what you see into words,” when the presentation is confusing or the diagnosis doesn’t quite fit, she added.

“Transforming signs and findings into semantics triggers a differential diagnosis, which is especially useful when we are diagnostically stumped. Studies have found that successful diagnosticians use twice as many semantic qualifiers as the physicians who were diagnostically incorrect.” This is especially significant in visual fields like dermatology, where a single word can paint a picture and rapidly focus a diagnostic search. “We often undervalue this function and relegate it to students starting out in the field,” Dr. Lowenstein said.

Cognitive shortcuts such as diagnostic heuristics all have blind spots, and diagnostic errors tend to fall in these blind spots, she added. “We tend to ignore them. In driving, we adapt to the use of rear and side view mirrors in order to drive safely. Similarly, in diagnostics, alternative views on the data can be very helpful. For example, when faced with difficult cases, take a time out to reanalyze the information without framing or context. Use systematic approaches, such as running down a papulosquamous differential diagnosis. Ask yourself: What can’t be explained in the picture? What doesn’t fit? Think in terms of probabilities – a rare presentation of a common disease is more likely than a rare disease,” she said.

Finally, asking for advice or second opinions from peers, whether by face-to-face discussion or via an online chat site, within the department or appealing to broader groups such as hospitalist dermatologist chat groups, can be helpful with difficult cases. Another strategy is simply to email an expert. Dr. Lowenstein said she’s had great success reaching out to authors of relevant papers by email. Most of her peers, she said, are interested in unusual cases and happy to help.

Dr. Ko has authored or coauthored books on the topics of visual recognition in dermatology and dermatopathology. They are “Dermatology: Visual Recognition and Case Reviews,” and “Dermatopathology: Diagnosis by First Impression.” Dr. Lowenstein reported that she has no conflicts of interest.

CHICAGO – Medicine, perhaps uniquely among the highly skilled professions, requires the practitioner to use his or her senses on a daily basis. Dermatologists and dermatopathologists rely on visual skills – pattern recognition, gestalt or “gut” first impressions, and step-by-step deliberations – to care for their patients.

But, like all human cognitive processes, visual assessments are error prone. The same brains that can parse a field of blue and pink dots to discern melanoma on a slide are also capable of glaring errors of omission: All too often, the brain follows a cognitive path for the wrong reasons.

Christine Ko, MD, professor of dermatology and pathology at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., became interested in the meta-cognition of her trade; that is, she sought to learn how to think about the thinking that’s needed to be a dermatologist or a dermatopathologist.

In a wide-ranging discussion at the summer meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology, Dr. Ko took attendees through The path led through lessons learned from cognitive science to the fine arts, to lessons learned from other visually oriented medical disciplines.

“Deliberate practice in dermatology is augmented by knowledge of specific cognitive principles that affect visual perception,” Dr. Ko said at the meeting. “This session will open your eyes to the world of visual intelligence that underlies expert dermatologic diagnosis.”

To begin with, what constitutes deliberate practice of dermatology or dermatopathology? Practically speaking, seeing many patients (or reading many slides) builds the base for true expertise, she noted. Physicians continue to hone their learning through independent reading, journal clubs, and meeting attendance, and seek opportunities for deliberate review of what’s still unknown, as in grand rounds – where, ideally, feedback is instantaneous.

Deliberate practice, though, should also include honing visual skills. “We find only the world we look for,” said Dr. Ko, quoting Henry David Thoreau. To sharpen the pattern recognition and keen observation that underpin dermatology and dermatopathology, she said, “We can train the brain.”

Radiology, another medical discipline that requires sustained visual attention, has a significant body of literature addressing common visually-related cognitive errors, she pointed out. In radiology, it’s been shown that deliberate observation of visual art can improve accuracy of reading films.

She observed that dermatologists and dermatopathologists need to think in color, so they may need to develop slightly different visual skills from radiologists who largely see a gray-scale world while they’re working.

Cognitive psychology also offers lessons. One seminal paper, “The invisible gorilla strikes again: Sustained inattentional blindness in expert observers,” issues a stern admonition: “[A] high level of expertise does not immunize individuals against inherent limitations of human attention imperception” (Psychol Sci. 2013 Sep;24[9]:1848-53). Inattentional blindness, Dr. Ko explained, occurs when “what we are focused on filters the world around us aggressively.” First author Trafton Drew, PhD, and his colleagues added: “Researchers should seek better understanding of these limits, so that medical and other man-made search tasks could be designed in ways that reduce the consequences of these limitations.”

How to overcome these limitations? “Concentrate on the camouflaged,” said Dr. Ko, taking a page – literally – from “Visual Intelligence: Sharpen Your Perception, Change Your Life” (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2016), a book by Amy Herman, JD. Ms. Herman devised the mnemonic “COBRA” to identify several steps that can prevent cognitive error from visual observation:

- Concentrating on the camouflaged, for dermatologists, might mean just looking again and focusing on the less-obvious. But, Dr. Ko said, it might mean turning your attention elsewhere for a while, and then looking back at the area in question. Or the patient or slide – or even the examiner – might need repositioning, for a fresh perspective.

- Taking One thing at a time. For dermatologists and dermatopathologists, this means sorting out the who, what, when, and where of the problem at hand. “ ‘Who’ is always the patient,” said Dr. Ko. “But part of ‘who’ is also us; if we’re tired, it can affect things.” There are many ‘whats’ to consider about the presenting problem or the tissue sample: What is the configuration? The architecture? What is the morphology? What’s the color, or cell type? Are there secondary changes? Does the tissue fit into the general category of a benign, or a malignant, lesion? The examination should include a methodical search for clues as to the duration of the problem – Is it acute or chronic? Finally, the ‘where’ – distribution on the body, or of a specimen on a slide, should also be noted.

- Take a Break. This means resting the eye and the mind by turning attention elsewhere, or shifting to light conversation with the patient, or just stepping away from the microscope for a time.

- Realign your expectations. What might you have missed? Is the patient telling you something in the history? Is it possible this is an uncommon presentation of a common condition, rather than a “zebra”?

- Ask someone else to look with you. Sometimes there’s no substitute for another set of eyes, and another brain working on the problem.

A congruent perspective comes from Daniel Kahneman, PhD, a Nobel Prize–winning economist. In 2011, he published a work addressing meta-cognition, called “Thinking Fast and Slow.”

From Dr. Kahneman’s work, Dr. Ko says dermatologists can learn to recognize two complementary ways of thinking. The “fast” system engages multiple cognitive processes to create a gestalt, “gut” impression. “Slow” thinking, in Dr. Kahneman’s construct, is deliberative, methodical, and traditionally thought of as “logical.” However, it would be a mistake to think of these two systems as existing in opposition, or even as completely separate from each other. “It’s sort of just a linguistic tool for us to have something to call it,” she said.

A “fast” analysis will involve some key elements of visual assessment, said Dr. Ko. Figure-ground separation is a basic element of visual assessment and is vital for the work of the dermatopathologist. “Choosing the wrong ‘figure’ may lead to cognitive error,” she explained, citing work on visual perception among dermatopathologists that found that figure-ground separation errors account for a significant number of diagnostic errors.

Other contributors to “fast” thinking include one’s own experience, seeing just a part of the image, judging which elements are close to each other and similar, and noting color contrasts and gradations.

The “slow” assessment is where deliberate practice comes in, said Dr. Ko. Here, the physician goes further, “to check for pertinent positive and negative evidence” for the initial diagnosis. “Play devil’s advocate, and ask yourself why it couldn’t be something else,” she said.

Eve Lowenstein, MD, PhD, is a dermatologist who publishes about heuristics in dermatology. She and Dr. Ko have collaborated to create a forthcoming two-part continuing medical education article in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology (JAAD) about cognitive biases and errors in dermatology.

Dr. Lowenstein’s perspective, recently elucidated in two British Journal of Dermatology articles, acknowledges that while “ubiquitous cognitive and visual heuristics can enhance diagnostic speed, they also create pitfalls and thinking traps that introduce significant variation in the diagnostic process,” she and her coauthor Richard Sidlow, MD, of Staten Island (N.Y.) University Hospital, wrote in the abstract accompanying the first article (Br J Dermatol. 2018 Dec;179[6]:1263-9). The second article was published in the same issue (Br J Dermatol. 2018 Dec;179[6]:1270-6).

Heuristics are cognitive shortcuts used to speed decision-making that build on what’s already known, as in the “fast” thinking of Dr. Kahneman’s paradigm. Though heuristics are used in all sorts of professions with high cognitive loads, there’s a risk when physicians get too comfortable with the shortcuts. Speaking frankly in an interview, Dr. Lowenstein said, “intellectual presumptiveness or overconfidence, which is a natural human tendency, can result in oversights and missing information critical to making a correct diagnosis, and premature closure on the wrong diagnosis.”

Diagnostic error, Dr. Lowenstein pointed out, can also result from an “attitudinal overconfidence,” which can come from complacency – being satisfied with the status quo or a lack of intellectual curiosity – or arrogance, she said.

“Complacency is the opposite of what is needed in medicine: an attitude where one cannot know enough. The pursuit of knowledge goes on, ever vigilantly. The world changes; practitioners must keep up and cannot fall back on their knowledge,” she said.

This kind of attitudinal and cognitive humility, she said, is essential to practicing quality care in dermatology. Having practical strategies to improve diagnosis, especially in difficult cases, can make a big difference. For Dr. Lowenstein, one of these tactics is to keep an error diary. “It has been said that ‘the only way to safeguard against error is to embrace it,’ ” she said, quoting Kathryn Schulz in “Being Wrong.” “Unfortunately, we learn some of our most profound lessons from our errors.”

By recording and tracking her own errors, not only is she able to see her own cognitive blind spots through meta-cognition – thinking about how we think – but she’s also able to share these lessons in her teaching. “Some of my best teaching tools for residents are from everything I have screwed up,” said Dr. Lowenstein, director of medical dermatology at the State University of New York Downstate Medical Center and Kings County Hospital, Brooklyn, N.Y.

Another useful tip is simply “to put what you see into words,” when the presentation is confusing or the diagnosis doesn’t quite fit, she added.

“Transforming signs and findings into semantics triggers a differential diagnosis, which is especially useful when we are diagnostically stumped. Studies have found that successful diagnosticians use twice as many semantic qualifiers as the physicians who were diagnostically incorrect.” This is especially significant in visual fields like dermatology, where a single word can paint a picture and rapidly focus a diagnostic search. “We often undervalue this function and relegate it to students starting out in the field,” Dr. Lowenstein said.

Cognitive shortcuts such as diagnostic heuristics all have blind spots, and diagnostic errors tend to fall in these blind spots, she added. “We tend to ignore them. In driving, we adapt to the use of rear and side view mirrors in order to drive safely. Similarly, in diagnostics, alternative views on the data can be very helpful. For example, when faced with difficult cases, take a time out to reanalyze the information without framing or context. Use systematic approaches, such as running down a papulosquamous differential diagnosis. Ask yourself: What can’t be explained in the picture? What doesn’t fit? Think in terms of probabilities – a rare presentation of a common disease is more likely than a rare disease,” she said.

Finally, asking for advice or second opinions from peers, whether by face-to-face discussion or via an online chat site, within the department or appealing to broader groups such as hospitalist dermatologist chat groups, can be helpful with difficult cases. Another strategy is simply to email an expert. Dr. Lowenstein said she’s had great success reaching out to authors of relevant papers by email. Most of her peers, she said, are interested in unusual cases and happy to help.

Dr. Ko has authored or coauthored books on the topics of visual recognition in dermatology and dermatopathology. They are “Dermatology: Visual Recognition and Case Reviews,” and “Dermatopathology: Diagnosis by First Impression.” Dr. Lowenstein reported that she has no conflicts of interest.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM SUMMER AAD 2018