User login

From the Moffitt Cancer Center, Tampa, FL (Dr. Vadaparampil, Ms. Bowman, Ms. Sehovic, Dr. Quinn), Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY (Ms. Kelvin), and Edward Via College of Osteopathic Medicine, Auburn, AL (Ms. Murphy).

Abstract

- Objective: To describe a script-based approach to assist oncology nurses in fertility discussions with their adolescent and young adult (AYA) patients.

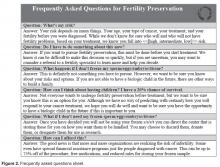

- Methods: Scripts were developed by a team that included experts in fertility and reproductive health, health education, health communication, and clinical care of AYA patients. Individual scripts for females, males, and survivors were created and accompanied by a flyer and frequently asked questions sheet. The script and supplementary materials were then vetted by oncology nurses who participated in the Educating Nurses about Reproductive Health Issues in Cancer Healthcare (ENRICH) training program.

- Results: The scripts were rated as helpful and socially appropriate with minor concerns noted about awkward wording and medical jargon.

- Conclusion: The updated scripts provide one approach for nurses to become more adept at discussing the topic of infertility and FP with AYA oncology patients and survivors.

In the United States, over 70,000 adolescents and young adults (AYAs) are diagnosed with cancer each year [1,2]. Treatments are available that are associated with improved survival for these cancers. Unfortunately, cancer treatment may significantly impact AYA survivors’ future fertility. Infertility or premature ovarian failure can occur during or after cancer treatment (eg, chemotherapy, radiation) for females, and males may be temporarily or permanently azoospermic [3]. There are a number of established methods of fertility preservation (FP) that are available; these include oocyte and embryo cryopreservation and ovarian transposition for females and sperm banking for males [3]. Experimental options for males include testicular tissue freezing and for females ovarian tissue cryopreservation.

The American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network [4,5] recommend discussing FP with patients of reproductive age, ideally before initiation of treatment. In 2013, ASCO updated guidelines extending the responsibility for discussion and referral for FP beyond the medical oncologist to explicitly include other physician specialties, nurses, and allied health care professionals in the oncology care setting [3]. However, multiple publications, including patient surveys and interviews, physician surveys, and medical record abstraction studies suggest these discussions do not consistently take place. In an analysis of 156 practice groups submitting data as part of ASCO's Quality Oncology Practice Initiative, only ~15%–20% of practices routinely discussed infertility risks and FP options [6]. A recent review of medical charts of patients aged 18–45 treated in 2011 at 1 of 4 large U.S. cancer care institutions found that documentation of discussions for infertility risk was 26%, 24% for FP option discussion, and 13% for fertility specialist referral [7].

Oncology nurses play a key role in patients’ care and, compared to other health care providers, are more likely to have multiple interactions with patients prior to the initiation of treatment [8]. They are often attuned to the medical and psychosocial needs of the patient and family and can advocate for their needs and desires [9]. However, existing research finds few oncology nurses discuss this topic with AYA patients. Studies examining barriers have identified factors that may hinder discussions about infertility and FP with AYA oncology patients. These barriers include lack of knowledge about cancer related infertility and available FP procedures; access to reproductive endocrinologists or sperm banking clinics; time constraints in busy clinics and concerns about delaying treatment; discomforts discussing reproductive health; patient’s ability to afford FP; bias about the suitability of FP for young or unpartnered or LGBT patients or those with a poor prognosis; and personal religious or moral values about the use of assisted reproductive technologies [10–15].

Equipping nurses with content-specific communication may overcome some of the barriers described. A method often used in nursing education and communication interventions is scripting [16–18]. Scripting provides precise key words that ensure consistency in the message, no matter the messenger [19]. This paper reports on the development and refinement of a series of scripts to guide discussions about FP for male and female AYA patients and survivors.

Script Development

In 2003 Studer developed the AIDET (Acknowledge, Introduce, Duration, Explanation, and Thank you) model of communication for health professionals [19]. AIDET is an effective tool in facilitating communication practices among nurses and physicians in adult and pediatric settings [20–24]. The AIDET model was adapted by our team to develop AIDED: Assess, Introduce, Decide, Explain, and Discuss, a script-based approach to assist oncology nurses in fertility discussions with their AYA patients. Our team included experts in fertility and reproductive health, health education, health communication, as well as clinical and psychosocial care of AYA patients.

Educating Nurses

Benefits of Scripts

Communication difficulties may present an obstacle for oncology nurses to address the infertility, FP information, and supportive care needs of AYA cancer patients [15]. While guidelines from leading health and professional organizations support the need to discuss these issues with patients, implementation requires providing practical tools that meet the needs of nurses’ practice setting and patient population [26].

The use of scripts has a long history in the

Conclusion

These scripts provide one approach for nurses to become more adept at discussing the topic of FP with AYA oncology patients. We will continue to update and refine these scripts and ultimately test their efficacy in improving psychosocial and behavioral outcomes for AYA patients. While scripts are effective, they must be updated to reflect relevant advances in clinical care. In addition, it is important to identify local resources to facilitate discussion and referral for those who seek additional information and or services related to FP. Such resources include psychosocial support, reproductive endocrinologists with expertise in the unique needs of AYA oncology patients, providers who accept pediatric patients (if needed), and financial assistance.

Corresponding author: Susan T. Vadaparampil, PhD, MPH, 12902 Magnolia Dr., MRC CANCONT, Tampa, FL 33612, susan.vadaparampil@moffitt.org.

Funding/support: ENRICH is funded by a National Cancer Institute R25 Training Grant: #5R25CA142519-05.

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Bleyer AOLM, O’Leary M, Barr L, Ries LAG. Cancer epidemiology in older adolescents and young adults 15 to 29 years of age, including SEER incidence and survival: 1975–2000. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2006.

2. Ward E, DeSantis C, Robbins A, et al. Childhood and adolescent cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin 2014;64: 83–103.

3. Loren AW, Mangu PB, Beck LN, et al. Fertility preservation for patients with cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol 2013;31:2500–10.

4. Lee SJ, Schover LR, Partridge AH, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology recommendations on fertility preservation in cancer patients. J Clin Oncol 2006;24:2917–31.

5. Coccia P, Altman J, Bhatia S, et al. Adolescent and young adult (AYA) oncology version 1.2012. National Comprehensive Cancer Network; 2012.

6. Neuss MN, Malin JL, Chan S, et al. Measuring the improving quality of outpatient care in medical oncology practices in the United States. J Clin Oncol 2013;31:1471–7.

7. Quinn GP, Block RG, Clayman ML, et al. If you did not document it, it did not happen: rates of documentation of discussion of infertility risk in adolescent and young adult oncology patients’ medical records. J Oncol Pract 2015;11: 137–44.

8. Cope D. Patients’ and physicians’ experinces with sperm banking and infertility issues related to cancer treatment. Clin J Oncol Nurs 2002;6:293–5.

9. Vaartio-Rajalin H, Leino-Kilpi H. Nurses as patient advocates in oncology care: activities based on literature. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2011;15:526–32.

10. King LM, Quinn GP, Vadaparampil ST, et al. Oncology nurses’ perceptions of barriers to discussion of fertility preservation with patients with cancer. Clin J Oncol Nurs 2008; 12:467–76.

11. Clayton HB, Vadaparampil ST, Quinn GP, et al. Trends in clinical practice and nurses’ attitudes about fertility preservation for pediatric patients with cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum 2008;35:449–55.

12. Vadaparampil ST, Clayton H, Quinn GP, et al. Pediatric oncology nurses’ attitudes related to discussing fertility preservation with pediatric cancer patients and their families. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs 2007;24:255–63.

13. Kotronoulas G, Papadopoulou C, Patiraki E. Nurses’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding provision of sexual health care in patients with cancer: critical review of the evidence. Support Care Cancer 2009;17:479–501.

14. Reebals JF, Brown R, Buckner EB. Nurse practice issues regarding sperm banking in adolescent male cancer patients. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs 2006;23:182–8.

15. Goossens J, Delbaere I, Beeckman D, et al. Communication difficulties and the experience of loneliness in patients with cancer dealing with fertility issues: a qualitative study. Oncol Nurs Forum 2015;42:34–43.

16. Mustard LW. Improving patient satisfaction through the consistent use of scripting by the nursing staff. JONAS Healthc Law Ethics Regul 2003;5:68–72.

17. Kuiper RA. Integration of innovative clinical reasoning pedagogies into a baccalaureate nursing curriculum. Creat Nurs 2013;19:128–39.

18. Handel DA, Fu R, Daya M, et al. The use of scripting at triage and its impact on elopements. Acad Emerg Med 2010; 17:495–500.

19. Studer Q. Hardwiring excellence: purpose, worthwhile work, making a difference. Gulf Breeze, FL: Fire Starter Publishing; 2003.

20. Katona A, Kunkel E, Arfaa J, et al. Methodology for delivering feedback to neurology house staff on communication skills using AIDET (Acknowledge, Introduce, Duration, Explanation, Thank You). Neurology 2014;82(10 Suppl):P1–328.

21. Prestia A , Dyess S. Maximizing caring relationships between nursing assistants and patients: Care partners. J Nurs Admin 2012;42:144–7.

22. Fisher MJ. A brief intervention to improve emotion-focused communication between newly licensed pediatric nurses and parents [dissertation]. Indianapolis: Indiana University; 2012.

23. Baker SJ. Key words: a prescriptive approach to reducing patient anxiety and improving safety. J Emerg Nurs 2011; 37:571–4.

24. Shupe R. Using skills validation and verification techniques to hardwire staff behaviors. J Emerg Nurs 2013;39:364–8.

25. Vadaparampil ST, Hutchins NM, Quinn GP. Reproductive health in the adolescent and young adult cancer patient: an innovative training program for oncology nurses. J Cancer Educ 2013;28:197–208.

26. Shekelle P, Woolf S, Grimshaw JM, et al. Developing clinical practice guidelines: reviewing, reporting, and publishing guidelines; updating guidelines; and the emerging issues of enhancing guideline implementability and accounting for comorbid conditions in guideline development. Implement Sci 2012;7:62.

27. Clayton JM, Adler JL, O’Callaghan A, et al. Intensive communication skills teaching for specialist training in palliative medicine: development and evaluation of an experiential workshop. J Palliat Med 2012;15:585–91.

28. Hymes DH. On communicative competence. In: Pride JB, Holmes J, editors. Sociolinguistics: selected readings. Harmondsworth: Penguin; 1972:269–93.

29. Asnani MR. Patient-physician communication. West Indian Med J 2009;58:357–61.

30. Clark PA. Medical practices’ sensitivity to patients’ needs: Opportunities and practices for improvement. J Ambulat Care Manage 2003;26:110–23.

31. Wanzer MB, Booth-Butterfield M, Gruber K. Perceptions of health care providers’ communication: Relationships between patient-centered communication and satisfaction. Health Care Commun 2004;16:363–84.

From the Moffitt Cancer Center, Tampa, FL (Dr. Vadaparampil, Ms. Bowman, Ms. Sehovic, Dr. Quinn), Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY (Ms. Kelvin), and Edward Via College of Osteopathic Medicine, Auburn, AL (Ms. Murphy).

Abstract

- Objective: To describe a script-based approach to assist oncology nurses in fertility discussions with their adolescent and young adult (AYA) patients.

- Methods: Scripts were developed by a team that included experts in fertility and reproductive health, health education, health communication, and clinical care of AYA patients. Individual scripts for females, males, and survivors were created and accompanied by a flyer and frequently asked questions sheet. The script and supplementary materials were then vetted by oncology nurses who participated in the Educating Nurses about Reproductive Health Issues in Cancer Healthcare (ENRICH) training program.

- Results: The scripts were rated as helpful and socially appropriate with minor concerns noted about awkward wording and medical jargon.

- Conclusion: The updated scripts provide one approach for nurses to become more adept at discussing the topic of infertility and FP with AYA oncology patients and survivors.

In the United States, over 70,000 adolescents and young adults (AYAs) are diagnosed with cancer each year [1,2]. Treatments are available that are associated with improved survival for these cancers. Unfortunately, cancer treatment may significantly impact AYA survivors’ future fertility. Infertility or premature ovarian failure can occur during or after cancer treatment (eg, chemotherapy, radiation) for females, and males may be temporarily or permanently azoospermic [3]. There are a number of established methods of fertility preservation (FP) that are available; these include oocyte and embryo cryopreservation and ovarian transposition for females and sperm banking for males [3]. Experimental options for males include testicular tissue freezing and for females ovarian tissue cryopreservation.

The American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network [4,5] recommend discussing FP with patients of reproductive age, ideally before initiation of treatment. In 2013, ASCO updated guidelines extending the responsibility for discussion and referral for FP beyond the medical oncologist to explicitly include other physician specialties, nurses, and allied health care professionals in the oncology care setting [3]. However, multiple publications, including patient surveys and interviews, physician surveys, and medical record abstraction studies suggest these discussions do not consistently take place. In an analysis of 156 practice groups submitting data as part of ASCO's Quality Oncology Practice Initiative, only ~15%–20% of practices routinely discussed infertility risks and FP options [6]. A recent review of medical charts of patients aged 18–45 treated in 2011 at 1 of 4 large U.S. cancer care institutions found that documentation of discussions for infertility risk was 26%, 24% for FP option discussion, and 13% for fertility specialist referral [7].

Oncology nurses play a key role in patients’ care and, compared to other health care providers, are more likely to have multiple interactions with patients prior to the initiation of treatment [8]. They are often attuned to the medical and psychosocial needs of the patient and family and can advocate for their needs and desires [9]. However, existing research finds few oncology nurses discuss this topic with AYA patients. Studies examining barriers have identified factors that may hinder discussions about infertility and FP with AYA oncology patients. These barriers include lack of knowledge about cancer related infertility and available FP procedures; access to reproductive endocrinologists or sperm banking clinics; time constraints in busy clinics and concerns about delaying treatment; discomforts discussing reproductive health; patient’s ability to afford FP; bias about the suitability of FP for young or unpartnered or LGBT patients or those with a poor prognosis; and personal religious or moral values about the use of assisted reproductive technologies [10–15].

Equipping nurses with content-specific communication may overcome some of the barriers described. A method often used in nursing education and communication interventions is scripting [16–18]. Scripting provides precise key words that ensure consistency in the message, no matter the messenger [19]. This paper reports on the development and refinement of a series of scripts to guide discussions about FP for male and female AYA patients and survivors.

Script Development

In 2003 Studer developed the AIDET (Acknowledge, Introduce, Duration, Explanation, and Thank you) model of communication for health professionals [19]. AIDET is an effective tool in facilitating communication practices among nurses and physicians in adult and pediatric settings [20–24]. The AIDET model was adapted by our team to develop AIDED: Assess, Introduce, Decide, Explain, and Discuss, a script-based approach to assist oncology nurses in fertility discussions with their AYA patients. Our team included experts in fertility and reproductive health, health education, health communication, as well as clinical and psychosocial care of AYA patients.

Educating Nurses

Benefits of Scripts

Communication difficulties may present an obstacle for oncology nurses to address the infertility, FP information, and supportive care needs of AYA cancer patients [15]. While guidelines from leading health and professional organizations support the need to discuss these issues with patients, implementation requires providing practical tools that meet the needs of nurses’ practice setting and patient population [26].

The use of scripts has a long history in the

Conclusion

These scripts provide one approach for nurses to become more adept at discussing the topic of FP with AYA oncology patients. We will continue to update and refine these scripts and ultimately test their efficacy in improving psychosocial and behavioral outcomes for AYA patients. While scripts are effective, they must be updated to reflect relevant advances in clinical care. In addition, it is important to identify local resources to facilitate discussion and referral for those who seek additional information and or services related to FP. Such resources include psychosocial support, reproductive endocrinologists with expertise in the unique needs of AYA oncology patients, providers who accept pediatric patients (if needed), and financial assistance.

Corresponding author: Susan T. Vadaparampil, PhD, MPH, 12902 Magnolia Dr., MRC CANCONT, Tampa, FL 33612, susan.vadaparampil@moffitt.org.

Funding/support: ENRICH is funded by a National Cancer Institute R25 Training Grant: #5R25CA142519-05.

Financial disclosures: None.

From the Moffitt Cancer Center, Tampa, FL (Dr. Vadaparampil, Ms. Bowman, Ms. Sehovic, Dr. Quinn), Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY (Ms. Kelvin), and Edward Via College of Osteopathic Medicine, Auburn, AL (Ms. Murphy).

Abstract

- Objective: To describe a script-based approach to assist oncology nurses in fertility discussions with their adolescent and young adult (AYA) patients.

- Methods: Scripts were developed by a team that included experts in fertility and reproductive health, health education, health communication, and clinical care of AYA patients. Individual scripts for females, males, and survivors were created and accompanied by a flyer and frequently asked questions sheet. The script and supplementary materials were then vetted by oncology nurses who participated in the Educating Nurses about Reproductive Health Issues in Cancer Healthcare (ENRICH) training program.

- Results: The scripts were rated as helpful and socially appropriate with minor concerns noted about awkward wording and medical jargon.

- Conclusion: The updated scripts provide one approach for nurses to become more adept at discussing the topic of infertility and FP with AYA oncology patients and survivors.

In the United States, over 70,000 adolescents and young adults (AYAs) are diagnosed with cancer each year [1,2]. Treatments are available that are associated with improved survival for these cancers. Unfortunately, cancer treatment may significantly impact AYA survivors’ future fertility. Infertility or premature ovarian failure can occur during or after cancer treatment (eg, chemotherapy, radiation) for females, and males may be temporarily or permanently azoospermic [3]. There are a number of established methods of fertility preservation (FP) that are available; these include oocyte and embryo cryopreservation and ovarian transposition for females and sperm banking for males [3]. Experimental options for males include testicular tissue freezing and for females ovarian tissue cryopreservation.

The American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network [4,5] recommend discussing FP with patients of reproductive age, ideally before initiation of treatment. In 2013, ASCO updated guidelines extending the responsibility for discussion and referral for FP beyond the medical oncologist to explicitly include other physician specialties, nurses, and allied health care professionals in the oncology care setting [3]. However, multiple publications, including patient surveys and interviews, physician surveys, and medical record abstraction studies suggest these discussions do not consistently take place. In an analysis of 156 practice groups submitting data as part of ASCO's Quality Oncology Practice Initiative, only ~15%–20% of practices routinely discussed infertility risks and FP options [6]. A recent review of medical charts of patients aged 18–45 treated in 2011 at 1 of 4 large U.S. cancer care institutions found that documentation of discussions for infertility risk was 26%, 24% for FP option discussion, and 13% for fertility specialist referral [7].

Oncology nurses play a key role in patients’ care and, compared to other health care providers, are more likely to have multiple interactions with patients prior to the initiation of treatment [8]. They are often attuned to the medical and psychosocial needs of the patient and family and can advocate for their needs and desires [9]. However, existing research finds few oncology nurses discuss this topic with AYA patients. Studies examining barriers have identified factors that may hinder discussions about infertility and FP with AYA oncology patients. These barriers include lack of knowledge about cancer related infertility and available FP procedures; access to reproductive endocrinologists or sperm banking clinics; time constraints in busy clinics and concerns about delaying treatment; discomforts discussing reproductive health; patient’s ability to afford FP; bias about the suitability of FP for young or unpartnered or LGBT patients or those with a poor prognosis; and personal religious or moral values about the use of assisted reproductive technologies [10–15].

Equipping nurses with content-specific communication may overcome some of the barriers described. A method often used in nursing education and communication interventions is scripting [16–18]. Scripting provides precise key words that ensure consistency in the message, no matter the messenger [19]. This paper reports on the development and refinement of a series of scripts to guide discussions about FP for male and female AYA patients and survivors.

Script Development

In 2003 Studer developed the AIDET (Acknowledge, Introduce, Duration, Explanation, and Thank you) model of communication for health professionals [19]. AIDET is an effective tool in facilitating communication practices among nurses and physicians in adult and pediatric settings [20–24]. The AIDET model was adapted by our team to develop AIDED: Assess, Introduce, Decide, Explain, and Discuss, a script-based approach to assist oncology nurses in fertility discussions with their AYA patients. Our team included experts in fertility and reproductive health, health education, health communication, as well as clinical and psychosocial care of AYA patients.

Educating Nurses

Benefits of Scripts

Communication difficulties may present an obstacle for oncology nurses to address the infertility, FP information, and supportive care needs of AYA cancer patients [15]. While guidelines from leading health and professional organizations support the need to discuss these issues with patients, implementation requires providing practical tools that meet the needs of nurses’ practice setting and patient population [26].

The use of scripts has a long history in the

Conclusion

These scripts provide one approach for nurses to become more adept at discussing the topic of FP with AYA oncology patients. We will continue to update and refine these scripts and ultimately test their efficacy in improving psychosocial and behavioral outcomes for AYA patients. While scripts are effective, they must be updated to reflect relevant advances in clinical care. In addition, it is important to identify local resources to facilitate discussion and referral for those who seek additional information and or services related to FP. Such resources include psychosocial support, reproductive endocrinologists with expertise in the unique needs of AYA oncology patients, providers who accept pediatric patients (if needed), and financial assistance.

Corresponding author: Susan T. Vadaparampil, PhD, MPH, 12902 Magnolia Dr., MRC CANCONT, Tampa, FL 33612, susan.vadaparampil@moffitt.org.

Funding/support: ENRICH is funded by a National Cancer Institute R25 Training Grant: #5R25CA142519-05.

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Bleyer AOLM, O’Leary M, Barr L, Ries LAG. Cancer epidemiology in older adolescents and young adults 15 to 29 years of age, including SEER incidence and survival: 1975–2000. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2006.

2. Ward E, DeSantis C, Robbins A, et al. Childhood and adolescent cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin 2014;64: 83–103.

3. Loren AW, Mangu PB, Beck LN, et al. Fertility preservation for patients with cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol 2013;31:2500–10.

4. Lee SJ, Schover LR, Partridge AH, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology recommendations on fertility preservation in cancer patients. J Clin Oncol 2006;24:2917–31.

5. Coccia P, Altman J, Bhatia S, et al. Adolescent and young adult (AYA) oncology version 1.2012. National Comprehensive Cancer Network; 2012.

6. Neuss MN, Malin JL, Chan S, et al. Measuring the improving quality of outpatient care in medical oncology practices in the United States. J Clin Oncol 2013;31:1471–7.

7. Quinn GP, Block RG, Clayman ML, et al. If you did not document it, it did not happen: rates of documentation of discussion of infertility risk in adolescent and young adult oncology patients’ medical records. J Oncol Pract 2015;11: 137–44.

8. Cope D. Patients’ and physicians’ experinces with sperm banking and infertility issues related to cancer treatment. Clin J Oncol Nurs 2002;6:293–5.

9. Vaartio-Rajalin H, Leino-Kilpi H. Nurses as patient advocates in oncology care: activities based on literature. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2011;15:526–32.

10. King LM, Quinn GP, Vadaparampil ST, et al. Oncology nurses’ perceptions of barriers to discussion of fertility preservation with patients with cancer. Clin J Oncol Nurs 2008; 12:467–76.

11. Clayton HB, Vadaparampil ST, Quinn GP, et al. Trends in clinical practice and nurses’ attitudes about fertility preservation for pediatric patients with cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum 2008;35:449–55.

12. Vadaparampil ST, Clayton H, Quinn GP, et al. Pediatric oncology nurses’ attitudes related to discussing fertility preservation with pediatric cancer patients and their families. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs 2007;24:255–63.

13. Kotronoulas G, Papadopoulou C, Patiraki E. Nurses’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding provision of sexual health care in patients with cancer: critical review of the evidence. Support Care Cancer 2009;17:479–501.

14. Reebals JF, Brown R, Buckner EB. Nurse practice issues regarding sperm banking in adolescent male cancer patients. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs 2006;23:182–8.

15. Goossens J, Delbaere I, Beeckman D, et al. Communication difficulties and the experience of loneliness in patients with cancer dealing with fertility issues: a qualitative study. Oncol Nurs Forum 2015;42:34–43.

16. Mustard LW. Improving patient satisfaction through the consistent use of scripting by the nursing staff. JONAS Healthc Law Ethics Regul 2003;5:68–72.

17. Kuiper RA. Integration of innovative clinical reasoning pedagogies into a baccalaureate nursing curriculum. Creat Nurs 2013;19:128–39.

18. Handel DA, Fu R, Daya M, et al. The use of scripting at triage and its impact on elopements. Acad Emerg Med 2010; 17:495–500.

19. Studer Q. Hardwiring excellence: purpose, worthwhile work, making a difference. Gulf Breeze, FL: Fire Starter Publishing; 2003.

20. Katona A, Kunkel E, Arfaa J, et al. Methodology for delivering feedback to neurology house staff on communication skills using AIDET (Acknowledge, Introduce, Duration, Explanation, Thank You). Neurology 2014;82(10 Suppl):P1–328.

21. Prestia A , Dyess S. Maximizing caring relationships between nursing assistants and patients: Care partners. J Nurs Admin 2012;42:144–7.

22. Fisher MJ. A brief intervention to improve emotion-focused communication between newly licensed pediatric nurses and parents [dissertation]. Indianapolis: Indiana University; 2012.

23. Baker SJ. Key words: a prescriptive approach to reducing patient anxiety and improving safety. J Emerg Nurs 2011; 37:571–4.

24. Shupe R. Using skills validation and verification techniques to hardwire staff behaviors. J Emerg Nurs 2013;39:364–8.

25. Vadaparampil ST, Hutchins NM, Quinn GP. Reproductive health in the adolescent and young adult cancer patient: an innovative training program for oncology nurses. J Cancer Educ 2013;28:197–208.

26. Shekelle P, Woolf S, Grimshaw JM, et al. Developing clinical practice guidelines: reviewing, reporting, and publishing guidelines; updating guidelines; and the emerging issues of enhancing guideline implementability and accounting for comorbid conditions in guideline development. Implement Sci 2012;7:62.

27. Clayton JM, Adler JL, O’Callaghan A, et al. Intensive communication skills teaching for specialist training in palliative medicine: development and evaluation of an experiential workshop. J Palliat Med 2012;15:585–91.

28. Hymes DH. On communicative competence. In: Pride JB, Holmes J, editors. Sociolinguistics: selected readings. Harmondsworth: Penguin; 1972:269–93.

29. Asnani MR. Patient-physician communication. West Indian Med J 2009;58:357–61.

30. Clark PA. Medical practices’ sensitivity to patients’ needs: Opportunities and practices for improvement. J Ambulat Care Manage 2003;26:110–23.

31. Wanzer MB, Booth-Butterfield M, Gruber K. Perceptions of health care providers’ communication: Relationships between patient-centered communication and satisfaction. Health Care Commun 2004;16:363–84.

1. Bleyer AOLM, O’Leary M, Barr L, Ries LAG. Cancer epidemiology in older adolescents and young adults 15 to 29 years of age, including SEER incidence and survival: 1975–2000. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2006.

2. Ward E, DeSantis C, Robbins A, et al. Childhood and adolescent cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin 2014;64: 83–103.

3. Loren AW, Mangu PB, Beck LN, et al. Fertility preservation for patients with cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol 2013;31:2500–10.

4. Lee SJ, Schover LR, Partridge AH, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology recommendations on fertility preservation in cancer patients. J Clin Oncol 2006;24:2917–31.

5. Coccia P, Altman J, Bhatia S, et al. Adolescent and young adult (AYA) oncology version 1.2012. National Comprehensive Cancer Network; 2012.

6. Neuss MN, Malin JL, Chan S, et al. Measuring the improving quality of outpatient care in medical oncology practices in the United States. J Clin Oncol 2013;31:1471–7.

7. Quinn GP, Block RG, Clayman ML, et al. If you did not document it, it did not happen: rates of documentation of discussion of infertility risk in adolescent and young adult oncology patients’ medical records. J Oncol Pract 2015;11: 137–44.

8. Cope D. Patients’ and physicians’ experinces with sperm banking and infertility issues related to cancer treatment. Clin J Oncol Nurs 2002;6:293–5.

9. Vaartio-Rajalin H, Leino-Kilpi H. Nurses as patient advocates in oncology care: activities based on literature. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2011;15:526–32.

10. King LM, Quinn GP, Vadaparampil ST, et al. Oncology nurses’ perceptions of barriers to discussion of fertility preservation with patients with cancer. Clin J Oncol Nurs 2008; 12:467–76.

11. Clayton HB, Vadaparampil ST, Quinn GP, et al. Trends in clinical practice and nurses’ attitudes about fertility preservation for pediatric patients with cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum 2008;35:449–55.

12. Vadaparampil ST, Clayton H, Quinn GP, et al. Pediatric oncology nurses’ attitudes related to discussing fertility preservation with pediatric cancer patients and their families. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs 2007;24:255–63.

13. Kotronoulas G, Papadopoulou C, Patiraki E. Nurses’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding provision of sexual health care in patients with cancer: critical review of the evidence. Support Care Cancer 2009;17:479–501.

14. Reebals JF, Brown R, Buckner EB. Nurse practice issues regarding sperm banking in adolescent male cancer patients. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs 2006;23:182–8.

15. Goossens J, Delbaere I, Beeckman D, et al. Communication difficulties and the experience of loneliness in patients with cancer dealing with fertility issues: a qualitative study. Oncol Nurs Forum 2015;42:34–43.

16. Mustard LW. Improving patient satisfaction through the consistent use of scripting by the nursing staff. JONAS Healthc Law Ethics Regul 2003;5:68–72.

17. Kuiper RA. Integration of innovative clinical reasoning pedagogies into a baccalaureate nursing curriculum. Creat Nurs 2013;19:128–39.

18. Handel DA, Fu R, Daya M, et al. The use of scripting at triage and its impact on elopements. Acad Emerg Med 2010; 17:495–500.

19. Studer Q. Hardwiring excellence: purpose, worthwhile work, making a difference. Gulf Breeze, FL: Fire Starter Publishing; 2003.

20. Katona A, Kunkel E, Arfaa J, et al. Methodology for delivering feedback to neurology house staff on communication skills using AIDET (Acknowledge, Introduce, Duration, Explanation, Thank You). Neurology 2014;82(10 Suppl):P1–328.

21. Prestia A , Dyess S. Maximizing caring relationships between nursing assistants and patients: Care partners. J Nurs Admin 2012;42:144–7.

22. Fisher MJ. A brief intervention to improve emotion-focused communication between newly licensed pediatric nurses and parents [dissertation]. Indianapolis: Indiana University; 2012.

23. Baker SJ. Key words: a prescriptive approach to reducing patient anxiety and improving safety. J Emerg Nurs 2011; 37:571–4.

24. Shupe R. Using skills validation and verification techniques to hardwire staff behaviors. J Emerg Nurs 2013;39:364–8.

25. Vadaparampil ST, Hutchins NM, Quinn GP. Reproductive health in the adolescent and young adult cancer patient: an innovative training program for oncology nurses. J Cancer Educ 2013;28:197–208.

26. Shekelle P, Woolf S, Grimshaw JM, et al. Developing clinical practice guidelines: reviewing, reporting, and publishing guidelines; updating guidelines; and the emerging issues of enhancing guideline implementability and accounting for comorbid conditions in guideline development. Implement Sci 2012;7:62.

27. Clayton JM, Adler JL, O’Callaghan A, et al. Intensive communication skills teaching for specialist training in palliative medicine: development and evaluation of an experiential workshop. J Palliat Med 2012;15:585–91.

28. Hymes DH. On communicative competence. In: Pride JB, Holmes J, editors. Sociolinguistics: selected readings. Harmondsworth: Penguin; 1972:269–93.

29. Asnani MR. Patient-physician communication. West Indian Med J 2009;58:357–61.

30. Clark PA. Medical practices’ sensitivity to patients’ needs: Opportunities and practices for improvement. J Ambulat Care Manage 2003;26:110–23.

31. Wanzer MB, Booth-Butterfield M, Gruber K. Perceptions of health care providers’ communication: Relationships between patient-centered communication and satisfaction. Health Care Commun 2004;16:363–84.