User login

Inpatient Communication Barriers and Drivers When Caring for Limited English Proficiency Children

Immigrant children make up the fastest growing segment of the population in the United States.1 While most immigrant children are fluent in English, approximately 40% live with a parent who has limited English proficiency (LEP; ie, speaks English less than “very well”).2,3 In pediatrics, LEP status has been associated with longer hospitalizations,4 higher hospitalization costs,5 increased risk for serious adverse medical events,4,6 and more frequent emergency department reutilization.7 In the inpatient setting, multiple aspects of care present a variety of communication challenges,8 which are amplified by shift work and workflow complexity that result in patients and families interacting with numerous providers over the course of an inpatient stay.

Increasing access to trained professional interpreters when caring for LEP patients improves communication, patient satisfaction, adherence, and mortality.9-12 However, even when access to interpreter services is established, effective use is not guaranteed.13 Up to 57% of pediatricians report relying on family members to communicate with LEP patients and their caregivers;9 23% of pediatric residents categorized LEP encounters as frustrating while 78% perceived care of LEP patients to be “misdirected” (eg, delay in diagnosis or discharge) because of associated language barriers.14

Understanding experiences of frontline inpatient medical providers and interpreters is crucial in identifying challenges and ways to optimize communication for hospitalized LEP patients and families. However, there is a paucity of literature exploring the perspectives of medical providers and interpreters as it relates to communication with hospitalized LEP children and families. In this study, we sought to identify barriers and drivers of effective communication with pediatric patients and families with LEP in the inpatient setting from the perspective of frontline medical providers and interpreters.

METHODS

Study Design

This qualitative study used Group Level Assessment (GLA), a structured participatory methodology that allows diverse groups of stakeholders to generate and evaluate data in interactive sessions.15-18 GLA structure promotes active participation, group problem-solving, and development of actionable plans, distinguishing it from focus groups and in-depth semistructured interviews.15,19 This study received a human subject research exemption by the institutional review board.

Study Setting

Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center (CCHMC) is a large quaternary care center with ~200 patient encounters each day who require the use of interpreter services. Interpreters (in-person, video, and phone) are utilized during admission, formal family-centered rounds, hospital discharge, and other encounters with physicians, nurses, and other healthcare professionals. In-person interpreters are available in-house for Spanish and Arabic, with 18 additional languages available through regional vendors. Despite available resources, there is no standard way in which medical providers and interpreters work with one another.

Study Participants and Recruitment

Medical providers who care for hospitalized general pediatric patients were eligible to participate, including attending physicians, resident physicians, bedside nurses, and inpatient ancillary staff (eg, respiratory therapists, physical therapists). Interpreters employed by CCHMC with experience in the inpatient setting were also eligible. Individuals were recruited based on published recommendations to optimize discussion and group-thinking.15 Each participant was asked to take part in one GLA session. Participants were assigned to specific sessions based on roles (ie, physicians, nurses, and interpreters) to maximize engagement and minimize the impact of hierarchy.

Study Procedure

GLA involves a seven-step structured process (Appendix 1): climate setting, generating, appreciating, reflecting, understanding, selecting, and action.15,18 Qualitative data were generated individually and anonymously by participants on flip charts in response to prompts such as: “I worry that LEP families___,” “The biggest challenge when using interpreter services is___,” and “I find___ works well in providing care for LEP families.” Prompts were developed by study investigators, modified based on input from nursing and interpreter services leadership, and finalized by GLA facilitators. Fifty-one unique prompts were utilized (Appendix 2); the number of prompts used (ranging from 15 to 32 prompts) per session was based on published recommendations.15 During sessions, study investigators took detailed notes, including verbatim transcription of participant quotes. Upon conclusion of the session, each participant completed a demographic survey, including years of experience, languages spoken and perceived fluency,20 and ethnicity.

Data Analysis

Within each session, under the guidance of trained and experienced GLA facilitators (WB, HV), participants distilled and summarized qualitative data into themes, discussed and prioritized themes, and generated action items. Following completion of all sessions, analyzed data was compiled by the research team to determine similarities and differences across groups based on participant roles, consolidate themes into barriers and drivers of communication with LEP families, and determine any overlap of priorities for action. Findings were shared back with each group to ensure accuracy and relevance.

RESULTS

Participants

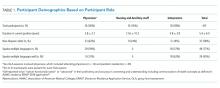

A total of 64 individuals participated (Table 1): hospital medicine physicians and residents (56%), inpatient nurses and ancillary staff (16%), and interpreters (28%). While 81% of physicians spoke multiple languages, only 25% reported speaking them well; two physicians were certified to communicate medical information without an interpreter present.

Themes Resulting from GLA Sessions

A total of four barriers (Table 2) and four drivers (Table 3) of effective communication with pediatric LEP patients and their families in the inpatient setting were identified by participants. Participants across all groups, despite enthusiasm around improving communication, were concerned about quality of care LEP families received, noting that the system is “designed to deliver less-good care” and that “we really haven’t figured out how to care for [LEP patients and families] in a [high-]quality and reliable way.” Variation in theme discussion was noted between groups based on participant role: physicians voiced concern about rapport with LEP families, nurses emphasized actionable tasks, and interpreters focused on heightened challenges in times of stress.

Barrier 1: Difficulties Accessing Interpreter Services

Medical providers (physicians and nurses) identified the “opaque process to access [interpreter] services” as one of their biggest challenges when communicating with LEP families. In particular, the process of scheduling interpreters was described as a “black box,” with physicians and nurses expressing difficulty determining if and when in-person interpreters were scheduled and uncertainty about when to use modalities other than in-person interpretation. Participants across groups highlighted the lack of systems knowledge from medical providers and limitations within the system that make predictable, timely, and reliable access to interpreters challenging, especially for uncommon languages. Medical providers desired more in-person interpreters who can “stay as long as clinically indicated,” citing frustration associated with using phone- and video-interpretation (eg, challenges locating technology, unfamiliarity with use, unreliable functionality of equipment). Interpreters voiced wanting to take time to finish each encounter fully without “being in a hurry because the next appointment is coming soon” or “rushing… in [to the next] session sweating.”

Barrier 2: Uncertainty in Communication with LEP Families

Participants across all groups described three areas of uncertainty as detailed in Table 2: (1) what to share and how to prioritize information during encounters with LEP patients and families, (2) what is communicated during interpretation, and (3) what LEP patients and families understand.

Barrier 3: Unclear and Inconsistent Expectations and Roles of Team Members

Given the complexity involved in communication between medical providers, interpreters, and families, participants across all groups reported feeling ill-prepared when navigating hospital encounters with LEP patients and families. Interpreters reported having little to no clinical context, medical providers reported having no knowledge of the assigned interpreter’s style, and both interpreters and medical providers reported that families have little idea of what to expect or how to engage. All groups voiced frustration about the lack of clarity regarding specific roles and scope of practice for each team member during an encounter, where multiple people end up “talking [or] using the interpreter at once.” Interpreters shared their expectations of medical providers to set the pace and lead conversations with LEP families. On the other hand, medical providers expressed a desire for interpreters to provide cultural context to the team without prompting and to interrupt during encounters when necessary to voice concerns or redirect conversations.

Barrier 4: Unmet Family Engagement Expectations

Participants across all groups articulated challenges with establishing rapport with LEP patients and families, sharing concerns that “inadequate communication” due to “cultural or language barriers” ultimately impacts quality of care. Participants reported decreased bidirectional engagement with and from LEP families. Medical providers not only noted difficulty in connecting with LEP families “on a more personal level” and providing frequent medical updates, but also felt that LEP families do not ask questions even when uncertain. Interpreters expressed concerns about medical providers “not [having] enough patience to answer families’ questions” while LEP families “shy away from asking questions.”

Driver 1: Utilizing a Team-Based Approach between Medical Providers and Interpreters

Participants from all groups emphasized that a mutual understanding of roles and shared expectations regarding communication and interpretation style, clinical context, and time constraints would establish a foundation for respect between medical providers and interpreters. They reported that a team-based approach to LEP patient and family encounters were crucial to achieving effective communication.

Driver 2: Understanding the Role of Cultural Context in Providing Culturally Effective Care.

Participants across all groups highlighted three different aspects of cultural context that drive effective communication: (1) medical providers’ perception of the family’s culture; (2) LEP families’ knowledge about the culture and healthcare system in the US, and (3) medical providers insight into their own preconceived ideas about LEP families.

Driver 3: Practicing Empathy for Patients and Families

All participants reported that respect for diversity and consideration of the backgrounds and perspectives of LEP patients and families are necessary. Furthermore, both medical providers and interpreters articulated a need to remain patient and mindful when interacting with LEP families despite challenges, especially since, as noted by interpreters, encounters may “take longer, but it’s for a reason.”

Driver 4: Using Effective Family-Centered Communication Strategies

Participants identified the use of effective family-centered communication principles as a driver to optimal communication. Many of the principles identified by medical providers and interpreters are generally applicable to all hospitalized patients and families regardless of English proficiency: optimizing verbal communication (eg, using shorter sentences, pausing to allow for interpretation), optimizing nonverbal communication (eg, setting, position, and body language), and assessment of family understanding and engagement (eg, use of teach back).

DISCUSSION

Frontline medical providers and interpreters identified barriers and drivers that impact communication with LEP patients and families during hospitalization. To our knowledge, this is the first study that uses a participatory method to explore the perspectives of medical providers and interpreters who care for LEP children and families in the inpatient setting. Despite existing difficulties and concerns regarding language barriers and its impact on quality of care for hospitalized LEP patients and families, participants were enthusiastic about how identified barriers and drivers may inform future improvement efforts. Notable action steps for future improvement discussed by our participants included: increased use and functionality of technology for timely and predictable access to interpreters, deliberate training for providers focused on delivery of culturally-effective care, consistent use of family-centered communication strategies including teach-back, and implementing interdisciplinary expectation setting through “presessions” before encounters with LEP families.

Participants elaborated on several barriers previously described in the literature including time constraints and technical problems.14,21,22 Such barriers may serve as deterrents to consistent and appropriate use of interpreters in healthcare settings.9 A heavy reliance on off-site interpreters (including phone- or video-interpreters) and lack of knowledge regarding resource availability likely amplified frustration for medical providers. Communication with LEP families can be daunting, especially when medical providers do not care for LEP families or work with interpreters on a regular basis.14 Standardizing the education of medical providers regarding available resources, as well as the logistics, process, and parameters for scheduling interpreters and using technology, was an action step identified by our GLA participants. Targeted education about the logistics of accessing interpreter services and having standardized ways to make technology use easier (ie, one-touch dialing in hospital rooms) has been associated with increased interpreter use and decreased interpreter-related delays in care.23

Our frontline medical providers expressed added concern about not spending as much time with LEP families. In fact, LEP families in the literature have perceived medical providers to spend less time with their children compared to their English-proficient counterparts.24 Language and cultural barriers, both perceived and real, may limit medical provider rapport with LEP patients and families14 and likely contribute to medical providers relying on their preconceived assumptions instead.25 Cultural competency education for medical providers, as highlighted by our GLA participants as an action item, can be used to provide more comprehensive and effective care.26,27

In addition to enhancing cultural humility through education, our participants emphasized the use of family-centered communication strategies as a driver of optimal family engagement and understanding. Actively inviting questions from families and utilizing teach-back, an established evidence-based strategy28-30 discussed by our participants, can be particularly powerful in assessing family understanding and engagement. While information should be presented in plain language for families in all encounters,31 these evidence-based practices are of particular importance when communicating with LEP families. They promote effective communication, empower families to share concerns in a structured manner, and allow medical providers to address matters in real-time with interpreters present.

Finally, our participants highlighted the need for partnerships between providers and interpreter services, noting unclear roles and expectations among interpreters and medical providers as a major barrier. Specifically, physicians noted confusion regarding the scope of an interpreter’s practice. Participants from GLA sessions discussed the importance of a team-based approach and suggested implementing a “presession” prior to encounters with LEP patients and families. Presessions—a concept well accepted among interpreters and recommended by consensus-based practice guidelines—enable medical providers and interpreters to establish shared expectations about scope of practice, communication, interpretation style, time constraints, and medical context prior to patient encounters.32,33

There are several limitations to our study. First, individuals who chose to participate were likely highly motivated by their clinical experiences with LEP patients and invested in improving communication with LEP families. Second, the study is limited in generalizability, as it was conducted at a single academic institution in a Midwestern city. Despite regional variations in available resources as well as patient and workforce demographics, our findings regarding major themes are in agreement with previously published literature and further add to our understanding of ways to improve communication with this vulnerable population across the care spectrum. Lastly, we were logistically limited in our ability to elicit the perspectives of LEP families due to the participatory nature of GLA; the need for multiple interpreters to simultaneously interact with LEP individuals would have not only hindered active LEP family participation but may have also biased the data generated by patients and families, as the services interpreters provide during their inpatient stay was the focus of our study. Engaging LEP families in their preferred language using participatory methods should be considered for future studies.

In conclusion, frontline providers of medical and language services identified barriers and drivers impacting the effective use of interpreter services when communicating with LEP families during hospitalization. Our enhanced understanding of barriers and drivers, as well as identified actionable interventions, will inform future improvement of communication and interactions with LEP families that contributes to effective and efficient family centered care. A framework for the development and implementation of organizational strategies aimed at improving communication with LEP families must include a thorough assessment of impact, feasibility, stakeholder involvement, and sustainability of specific interventions. While there is no simple formula to improve language services, health systems should establish and adopt language access policies, standardize communication practices, and develop processes to optimize the use of language services in the hospital. Furthermore, engagement with LEP families to better understand their perceptions and experiences with the healthcare system is crucial to improve communication between medical providers and LEP families in the inpatient setting and should be the subject of future studies.

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding

No external funding was secured for this study. Dr. Joanna Thomson is supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (Grant #K08 HS025138). Dr. Raglin Bignall was supported through a Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award (T32HP10027) when the study was conducted. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding organizations. The funding organizations had no role in the design, preparation, review, or approval of this paper.

1. The American Academy of Pediatrics Council on Community Pediatrics. Providing care for immigrant, migrant, and border children. Pediatrics. 2013;131(6):e2028-e2034. PubMed

2. Meneses C, Chilton L, Duffee J, et al. Council on Community Pediatrics Immigrant Health Tool Kit. The American Academy of Pediatrics. https://www.aap.org/en-us/Documents/cocp_toolkit_full.pdf. Accessed May 13, 2019.

3. Office for Civil Rights. Guidance to Federal Financial Assistance Recipients Regarding Title VI and the Prohibition Against National Origin Discrimination Affecting Limited English Proficient Persons. https://www.hhs.gov/civil-rights/for-individuals/special-topics/limited-english-proficiency/guidance-federal-financial-assistance-recipients-title-vi/index.html. Accessed May 13, 2019.

4. Lion KC, Rafton SA, Shafii J, et al. Association between language, serious adverse events, and length of stay Among hospitalized children. Hosp Pediatr. 2013;3(3):219-225. https://doi.org/10.1542/hpeds.2012-0091.

5. Lion KC, Wright DR, Desai AD, Mangione-Smith R. Costs of care for hospitalized children associated With preferred language and insurance type. Hosp Pediatr. 2017;7(2):70-78. https://doi.org/10.1542/hpeds.2016-0051.

6. Cohen AL, Rivara F, Marcuse EK, McPhillips H, Davis R. Are language barriers associated with serious medical events in hospitalized pediatric patients? Pediatrics. 2005;116(3):575-579. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2005-0521.

7. Samuels-Kalow ME, Stack AM, Amico K, Porter SC. Parental language and return visits to the Emergency Department After discharge. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2017;33(6):402-404. https://doi.org/10.1097/PEC.0000000000000592.

8. Unaka NI, Statile AM, Choe A, Shonna Yin H. Addressing health literacy in the inpatient setting. Curr Treat Options Pediatr. 2018;4(2):283-299. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40746-018-0122-3.

9. DeCamp LR, Kuo DZ, Flores G, O’Connor K, Minkovitz CS. Changes in language services use by US pediatricians. Pediatrics. 2013;132(2):e396-e406. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2012-2909.

10. Flores G. The impact of medical interpreter services on the quality of health care: A systematic review. Med Care Res Rev. 2005;62(3):255-299. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077558705275416.

11. Flores G, Abreu M, Barone CP, Bachur R, Lin H. Errors of medical interpretation and their potential clinical consequences: A comparison of professional versus hoc versus no interpreters. Ann Emerg Med. 2012;60(5):545-553. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2012.01.025.

12. Anand KJ, Sepanski RJ, Giles K, Shah SH, Juarez PD. Pediatric intensive care unit mortality among Latino children before and after a multilevel health care delivery intervention. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169(4):383-390. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.3789.

13. The Joint Commission. Advancing Effective Communication, Cultural Competence, and Patient- and Family-Centered Care: A Roadmap for Hospitals. Oakbrook Terrace, IL: The Joint Commission; 2010.

14. Hernandez RG, Cowden JD, Moon M et al. Predictors of resident satisfaction in caring for limited English proficient families: a multisite study. Acad Pediatr. 2014;14(2):173-180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2013.12.002.

15. Vaughn LM, Lohmueller M. Calling all stakeholders: group-level assessment (GLA)-a qualitative and participatory method for large groups. Eval Rev. 2014;38(4):336-355. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193841X14544903.

16. Vaughn LM, Jacquez F, Zhao J, Lang M. Partnering with students to explore the health needs of an ethnically diverse, low-resource school: an innovative large group assessment approach. Fam Commun Health. 2011;34(1):72-84. https://doi.org/10.1097/FCH.0b013e3181fded12.

17. Gosdin CH, Vaughn L. Perceptions of physician bedside handoff with nurse and family involvement. Hosp Pediatr. 2012;2(1):34-38. https://doi.org/10.1542/hpeds.2011-0008-2.

18. Graham KE, Schellinger AR, Vaughn LM. Developing strategies for positive change: transitioning foster youth to adulthood. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2015;54:71-79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2015.04.014.

19. Vaughn LM. Group level assessment: A Large Group Method for Identifying Primary Issues and Needs within a community. London2014. http://methods.sagepub.com/case/group-level-assessment-large-group-primary-issues-needs-community. Accessed 2017/07/26.

20. Association of American Medical Colleges Electronic Residency Application Service. ERAS 2018 MyERAS Application Worksheet: Language Fluency. Washington, DC:: Association of American Medical Colleges; 2018:5.

21. Brisset C, Leanza Y, Laforest K. Working with interpreters in health care: A systematic review and meta-ethnography of qualitative studies. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;91(2):131-140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2012.11.008.

22. Wiking E, Saleh-Stattin N, Johansson SE, Sundquist J. A description of some aspects of the triangular meeting between immigrant patients, their interpreters and GPs in primary health care in Stockholm, Sweden. Fam Pract. 2009;26(5):377-383. https://doi.org/10.1093/fampra/cmp052.

23. Lion KC, Ebel BE, Rafton S et al. Evaluation of a quality improvement intervention to increase use of telephonic interpretation. Pediatrics. 2015;135(3):e709-e716. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2014-2024.

24. Zurca AD, Fisher KR, Flor RJ, et al. Communication with limited English-proficient families in the PICU. Hosp Pediatr. 2017;7(1):9-15. https://doi.org/10.1542/hpeds.2016-0071.

25. Kodjo C. Cultural competence in clinician communication. Pediatr Rev. 2009;30(2):57-64. https://doi.org/10.1542/pir.30-2-57.

26. Britton CV, American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Pediatric Workforce. Ensuring culturally effective pediatric care: implications for education and health policy. Pediatrics. 2004;114(6):1677-1685. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2004-2091.

27. The American Academy of Pediatrics. Culturally Effective Care Toolkit: Providing Cuturally Effective Pediatric Care; 2018. https://www.aap.org/en-us/professional-resources/practice-transformation/managing-patients/Pages/effective-care.aspx. Accessed May 13, 2019.

28. Starmer AJ, Spector ND, Srivastava R, et al. Changes in medical errors after implementation of a handoff program. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(19):1803-1812. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa1405556.

29. Jager AJ, Wynia MK. Who gets a teach-back? Patient-reported incidence of experiencing a teach-back. J Health Commun. 2012;17 Supplement 3:294-302. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2012.712624.

30. Kornburger C, Gibson C, Sadowski S, Maletta K, Klingbeil C. Using “teach-back” to promote a safe transition from hospital to home: an evidence-based approach to improving the discharge process. J Pediatr Nurs. 2013;28(3):282-291. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedn.2012.10.007.

31. Abrams MA, Klass P, Dreyer BP. Health literacy and children: recommendations for action. Pediatrics. 2009;124 Supplement 3:S327-S331. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2009-1162I.

32. Betancourt JR, Renfrew MR, Green AR, Lopez L, Wasserman M. Improving Patient Safety Systems for Patients with Limited English Proficiency: a Guide for Hospitals. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2012. 33. The National Council on Interpreting in Health Care. Best Practices for Communicating Through an Interpreter . https://refugeehealthta.org/access-to-care/language-access/best-practices-communicating-through-an-interpreter/. Accessed May 19, 2019.

33. The National Council on Interpreting in Health Care. Best Practices for Communicating Through an Interpreter . https://refugeehealthta.org/access-to-care/language-access/best-practices-communicating-through-an-interpreter/. Accessed May 19, 2019.

Immigrant children make up the fastest growing segment of the population in the United States.1 While most immigrant children are fluent in English, approximately 40% live with a parent who has limited English proficiency (LEP; ie, speaks English less than “very well”).2,3 In pediatrics, LEP status has been associated with longer hospitalizations,4 higher hospitalization costs,5 increased risk for serious adverse medical events,4,6 and more frequent emergency department reutilization.7 In the inpatient setting, multiple aspects of care present a variety of communication challenges,8 which are amplified by shift work and workflow complexity that result in patients and families interacting with numerous providers over the course of an inpatient stay.

Increasing access to trained professional interpreters when caring for LEP patients improves communication, patient satisfaction, adherence, and mortality.9-12 However, even when access to interpreter services is established, effective use is not guaranteed.13 Up to 57% of pediatricians report relying on family members to communicate with LEP patients and their caregivers;9 23% of pediatric residents categorized LEP encounters as frustrating while 78% perceived care of LEP patients to be “misdirected” (eg, delay in diagnosis or discharge) because of associated language barriers.14

Understanding experiences of frontline inpatient medical providers and interpreters is crucial in identifying challenges and ways to optimize communication for hospitalized LEP patients and families. However, there is a paucity of literature exploring the perspectives of medical providers and interpreters as it relates to communication with hospitalized LEP children and families. In this study, we sought to identify barriers and drivers of effective communication with pediatric patients and families with LEP in the inpatient setting from the perspective of frontline medical providers and interpreters.

METHODS

Study Design

This qualitative study used Group Level Assessment (GLA), a structured participatory methodology that allows diverse groups of stakeholders to generate and evaluate data in interactive sessions.15-18 GLA structure promotes active participation, group problem-solving, and development of actionable plans, distinguishing it from focus groups and in-depth semistructured interviews.15,19 This study received a human subject research exemption by the institutional review board.

Study Setting

Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center (CCHMC) is a large quaternary care center with ~200 patient encounters each day who require the use of interpreter services. Interpreters (in-person, video, and phone) are utilized during admission, formal family-centered rounds, hospital discharge, and other encounters with physicians, nurses, and other healthcare professionals. In-person interpreters are available in-house for Spanish and Arabic, with 18 additional languages available through regional vendors. Despite available resources, there is no standard way in which medical providers and interpreters work with one another.

Study Participants and Recruitment

Medical providers who care for hospitalized general pediatric patients were eligible to participate, including attending physicians, resident physicians, bedside nurses, and inpatient ancillary staff (eg, respiratory therapists, physical therapists). Interpreters employed by CCHMC with experience in the inpatient setting were also eligible. Individuals were recruited based on published recommendations to optimize discussion and group-thinking.15 Each participant was asked to take part in one GLA session. Participants were assigned to specific sessions based on roles (ie, physicians, nurses, and interpreters) to maximize engagement and minimize the impact of hierarchy.

Study Procedure

GLA involves a seven-step structured process (Appendix 1): climate setting, generating, appreciating, reflecting, understanding, selecting, and action.15,18 Qualitative data were generated individually and anonymously by participants on flip charts in response to prompts such as: “I worry that LEP families___,” “The biggest challenge when using interpreter services is___,” and “I find___ works well in providing care for LEP families.” Prompts were developed by study investigators, modified based on input from nursing and interpreter services leadership, and finalized by GLA facilitators. Fifty-one unique prompts were utilized (Appendix 2); the number of prompts used (ranging from 15 to 32 prompts) per session was based on published recommendations.15 During sessions, study investigators took detailed notes, including verbatim transcription of participant quotes. Upon conclusion of the session, each participant completed a demographic survey, including years of experience, languages spoken and perceived fluency,20 and ethnicity.

Data Analysis

Within each session, under the guidance of trained and experienced GLA facilitators (WB, HV), participants distilled and summarized qualitative data into themes, discussed and prioritized themes, and generated action items. Following completion of all sessions, analyzed data was compiled by the research team to determine similarities and differences across groups based on participant roles, consolidate themes into barriers and drivers of communication with LEP families, and determine any overlap of priorities for action. Findings were shared back with each group to ensure accuracy and relevance.

RESULTS

Participants

A total of 64 individuals participated (Table 1): hospital medicine physicians and residents (56%), inpatient nurses and ancillary staff (16%), and interpreters (28%). While 81% of physicians spoke multiple languages, only 25% reported speaking them well; two physicians were certified to communicate medical information without an interpreter present.

Themes Resulting from GLA Sessions

A total of four barriers (Table 2) and four drivers (Table 3) of effective communication with pediatric LEP patients and their families in the inpatient setting were identified by participants. Participants across all groups, despite enthusiasm around improving communication, were concerned about quality of care LEP families received, noting that the system is “designed to deliver less-good care” and that “we really haven’t figured out how to care for [LEP patients and families] in a [high-]quality and reliable way.” Variation in theme discussion was noted between groups based on participant role: physicians voiced concern about rapport with LEP families, nurses emphasized actionable tasks, and interpreters focused on heightened challenges in times of stress.

Barrier 1: Difficulties Accessing Interpreter Services

Medical providers (physicians and nurses) identified the “opaque process to access [interpreter] services” as one of their biggest challenges when communicating with LEP families. In particular, the process of scheduling interpreters was described as a “black box,” with physicians and nurses expressing difficulty determining if and when in-person interpreters were scheduled and uncertainty about when to use modalities other than in-person interpretation. Participants across groups highlighted the lack of systems knowledge from medical providers and limitations within the system that make predictable, timely, and reliable access to interpreters challenging, especially for uncommon languages. Medical providers desired more in-person interpreters who can “stay as long as clinically indicated,” citing frustration associated with using phone- and video-interpretation (eg, challenges locating technology, unfamiliarity with use, unreliable functionality of equipment). Interpreters voiced wanting to take time to finish each encounter fully without “being in a hurry because the next appointment is coming soon” or “rushing… in [to the next] session sweating.”

Barrier 2: Uncertainty in Communication with LEP Families

Participants across all groups described three areas of uncertainty as detailed in Table 2: (1) what to share and how to prioritize information during encounters with LEP patients and families, (2) what is communicated during interpretation, and (3) what LEP patients and families understand.

Barrier 3: Unclear and Inconsistent Expectations and Roles of Team Members

Given the complexity involved in communication between medical providers, interpreters, and families, participants across all groups reported feeling ill-prepared when navigating hospital encounters with LEP patients and families. Interpreters reported having little to no clinical context, medical providers reported having no knowledge of the assigned interpreter’s style, and both interpreters and medical providers reported that families have little idea of what to expect or how to engage. All groups voiced frustration about the lack of clarity regarding specific roles and scope of practice for each team member during an encounter, where multiple people end up “talking [or] using the interpreter at once.” Interpreters shared their expectations of medical providers to set the pace and lead conversations with LEP families. On the other hand, medical providers expressed a desire for interpreters to provide cultural context to the team without prompting and to interrupt during encounters when necessary to voice concerns or redirect conversations.

Barrier 4: Unmet Family Engagement Expectations

Participants across all groups articulated challenges with establishing rapport with LEP patients and families, sharing concerns that “inadequate communication” due to “cultural or language barriers” ultimately impacts quality of care. Participants reported decreased bidirectional engagement with and from LEP families. Medical providers not only noted difficulty in connecting with LEP families “on a more personal level” and providing frequent medical updates, but also felt that LEP families do not ask questions even when uncertain. Interpreters expressed concerns about medical providers “not [having] enough patience to answer families’ questions” while LEP families “shy away from asking questions.”

Driver 1: Utilizing a Team-Based Approach between Medical Providers and Interpreters

Participants from all groups emphasized that a mutual understanding of roles and shared expectations regarding communication and interpretation style, clinical context, and time constraints would establish a foundation for respect between medical providers and interpreters. They reported that a team-based approach to LEP patient and family encounters were crucial to achieving effective communication.

Driver 2: Understanding the Role of Cultural Context in Providing Culturally Effective Care.

Participants across all groups highlighted three different aspects of cultural context that drive effective communication: (1) medical providers’ perception of the family’s culture; (2) LEP families’ knowledge about the culture and healthcare system in the US, and (3) medical providers insight into their own preconceived ideas about LEP families.

Driver 3: Practicing Empathy for Patients and Families

All participants reported that respect for diversity and consideration of the backgrounds and perspectives of LEP patients and families are necessary. Furthermore, both medical providers and interpreters articulated a need to remain patient and mindful when interacting with LEP families despite challenges, especially since, as noted by interpreters, encounters may “take longer, but it’s for a reason.”

Driver 4: Using Effective Family-Centered Communication Strategies

Participants identified the use of effective family-centered communication principles as a driver to optimal communication. Many of the principles identified by medical providers and interpreters are generally applicable to all hospitalized patients and families regardless of English proficiency: optimizing verbal communication (eg, using shorter sentences, pausing to allow for interpretation), optimizing nonverbal communication (eg, setting, position, and body language), and assessment of family understanding and engagement (eg, use of teach back).

DISCUSSION

Frontline medical providers and interpreters identified barriers and drivers that impact communication with LEP patients and families during hospitalization. To our knowledge, this is the first study that uses a participatory method to explore the perspectives of medical providers and interpreters who care for LEP children and families in the inpatient setting. Despite existing difficulties and concerns regarding language barriers and its impact on quality of care for hospitalized LEP patients and families, participants were enthusiastic about how identified barriers and drivers may inform future improvement efforts. Notable action steps for future improvement discussed by our participants included: increased use and functionality of technology for timely and predictable access to interpreters, deliberate training for providers focused on delivery of culturally-effective care, consistent use of family-centered communication strategies including teach-back, and implementing interdisciplinary expectation setting through “presessions” before encounters with LEP families.

Participants elaborated on several barriers previously described in the literature including time constraints and technical problems.14,21,22 Such barriers may serve as deterrents to consistent and appropriate use of interpreters in healthcare settings.9 A heavy reliance on off-site interpreters (including phone- or video-interpreters) and lack of knowledge regarding resource availability likely amplified frustration for medical providers. Communication with LEP families can be daunting, especially when medical providers do not care for LEP families or work with interpreters on a regular basis.14 Standardizing the education of medical providers regarding available resources, as well as the logistics, process, and parameters for scheduling interpreters and using technology, was an action step identified by our GLA participants. Targeted education about the logistics of accessing interpreter services and having standardized ways to make technology use easier (ie, one-touch dialing in hospital rooms) has been associated with increased interpreter use and decreased interpreter-related delays in care.23

Our frontline medical providers expressed added concern about not spending as much time with LEP families. In fact, LEP families in the literature have perceived medical providers to spend less time with their children compared to their English-proficient counterparts.24 Language and cultural barriers, both perceived and real, may limit medical provider rapport with LEP patients and families14 and likely contribute to medical providers relying on their preconceived assumptions instead.25 Cultural competency education for medical providers, as highlighted by our GLA participants as an action item, can be used to provide more comprehensive and effective care.26,27

In addition to enhancing cultural humility through education, our participants emphasized the use of family-centered communication strategies as a driver of optimal family engagement and understanding. Actively inviting questions from families and utilizing teach-back, an established evidence-based strategy28-30 discussed by our participants, can be particularly powerful in assessing family understanding and engagement. While information should be presented in plain language for families in all encounters,31 these evidence-based practices are of particular importance when communicating with LEP families. They promote effective communication, empower families to share concerns in a structured manner, and allow medical providers to address matters in real-time with interpreters present.

Finally, our participants highlighted the need for partnerships between providers and interpreter services, noting unclear roles and expectations among interpreters and medical providers as a major barrier. Specifically, physicians noted confusion regarding the scope of an interpreter’s practice. Participants from GLA sessions discussed the importance of a team-based approach and suggested implementing a “presession” prior to encounters with LEP patients and families. Presessions—a concept well accepted among interpreters and recommended by consensus-based practice guidelines—enable medical providers and interpreters to establish shared expectations about scope of practice, communication, interpretation style, time constraints, and medical context prior to patient encounters.32,33

There are several limitations to our study. First, individuals who chose to participate were likely highly motivated by their clinical experiences with LEP patients and invested in improving communication with LEP families. Second, the study is limited in generalizability, as it was conducted at a single academic institution in a Midwestern city. Despite regional variations in available resources as well as patient and workforce demographics, our findings regarding major themes are in agreement with previously published literature and further add to our understanding of ways to improve communication with this vulnerable population across the care spectrum. Lastly, we were logistically limited in our ability to elicit the perspectives of LEP families due to the participatory nature of GLA; the need for multiple interpreters to simultaneously interact with LEP individuals would have not only hindered active LEP family participation but may have also biased the data generated by patients and families, as the services interpreters provide during their inpatient stay was the focus of our study. Engaging LEP families in their preferred language using participatory methods should be considered for future studies.

In conclusion, frontline providers of medical and language services identified barriers and drivers impacting the effective use of interpreter services when communicating with LEP families during hospitalization. Our enhanced understanding of barriers and drivers, as well as identified actionable interventions, will inform future improvement of communication and interactions with LEP families that contributes to effective and efficient family centered care. A framework for the development and implementation of organizational strategies aimed at improving communication with LEP families must include a thorough assessment of impact, feasibility, stakeholder involvement, and sustainability of specific interventions. While there is no simple formula to improve language services, health systems should establish and adopt language access policies, standardize communication practices, and develop processes to optimize the use of language services in the hospital. Furthermore, engagement with LEP families to better understand their perceptions and experiences with the healthcare system is crucial to improve communication between medical providers and LEP families in the inpatient setting and should be the subject of future studies.

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding

No external funding was secured for this study. Dr. Joanna Thomson is supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (Grant #K08 HS025138). Dr. Raglin Bignall was supported through a Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award (T32HP10027) when the study was conducted. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding organizations. The funding organizations had no role in the design, preparation, review, or approval of this paper.

Immigrant children make up the fastest growing segment of the population in the United States.1 While most immigrant children are fluent in English, approximately 40% live with a parent who has limited English proficiency (LEP; ie, speaks English less than “very well”).2,3 In pediatrics, LEP status has been associated with longer hospitalizations,4 higher hospitalization costs,5 increased risk for serious adverse medical events,4,6 and more frequent emergency department reutilization.7 In the inpatient setting, multiple aspects of care present a variety of communication challenges,8 which are amplified by shift work and workflow complexity that result in patients and families interacting with numerous providers over the course of an inpatient stay.

Increasing access to trained professional interpreters when caring for LEP patients improves communication, patient satisfaction, adherence, and mortality.9-12 However, even when access to interpreter services is established, effective use is not guaranteed.13 Up to 57% of pediatricians report relying on family members to communicate with LEP patients and their caregivers;9 23% of pediatric residents categorized LEP encounters as frustrating while 78% perceived care of LEP patients to be “misdirected” (eg, delay in diagnosis or discharge) because of associated language barriers.14

Understanding experiences of frontline inpatient medical providers and interpreters is crucial in identifying challenges and ways to optimize communication for hospitalized LEP patients and families. However, there is a paucity of literature exploring the perspectives of medical providers and interpreters as it relates to communication with hospitalized LEP children and families. In this study, we sought to identify barriers and drivers of effective communication with pediatric patients and families with LEP in the inpatient setting from the perspective of frontline medical providers and interpreters.

METHODS

Study Design

This qualitative study used Group Level Assessment (GLA), a structured participatory methodology that allows diverse groups of stakeholders to generate and evaluate data in interactive sessions.15-18 GLA structure promotes active participation, group problem-solving, and development of actionable plans, distinguishing it from focus groups and in-depth semistructured interviews.15,19 This study received a human subject research exemption by the institutional review board.

Study Setting

Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center (CCHMC) is a large quaternary care center with ~200 patient encounters each day who require the use of interpreter services. Interpreters (in-person, video, and phone) are utilized during admission, formal family-centered rounds, hospital discharge, and other encounters with physicians, nurses, and other healthcare professionals. In-person interpreters are available in-house for Spanish and Arabic, with 18 additional languages available through regional vendors. Despite available resources, there is no standard way in which medical providers and interpreters work with one another.

Study Participants and Recruitment

Medical providers who care for hospitalized general pediatric patients were eligible to participate, including attending physicians, resident physicians, bedside nurses, and inpatient ancillary staff (eg, respiratory therapists, physical therapists). Interpreters employed by CCHMC with experience in the inpatient setting were also eligible. Individuals were recruited based on published recommendations to optimize discussion and group-thinking.15 Each participant was asked to take part in one GLA session. Participants were assigned to specific sessions based on roles (ie, physicians, nurses, and interpreters) to maximize engagement and minimize the impact of hierarchy.

Study Procedure

GLA involves a seven-step structured process (Appendix 1): climate setting, generating, appreciating, reflecting, understanding, selecting, and action.15,18 Qualitative data were generated individually and anonymously by participants on flip charts in response to prompts such as: “I worry that LEP families___,” “The biggest challenge when using interpreter services is___,” and “I find___ works well in providing care for LEP families.” Prompts were developed by study investigators, modified based on input from nursing and interpreter services leadership, and finalized by GLA facilitators. Fifty-one unique prompts were utilized (Appendix 2); the number of prompts used (ranging from 15 to 32 prompts) per session was based on published recommendations.15 During sessions, study investigators took detailed notes, including verbatim transcription of participant quotes. Upon conclusion of the session, each participant completed a demographic survey, including years of experience, languages spoken and perceived fluency,20 and ethnicity.

Data Analysis

Within each session, under the guidance of trained and experienced GLA facilitators (WB, HV), participants distilled and summarized qualitative data into themes, discussed and prioritized themes, and generated action items. Following completion of all sessions, analyzed data was compiled by the research team to determine similarities and differences across groups based on participant roles, consolidate themes into barriers and drivers of communication with LEP families, and determine any overlap of priorities for action. Findings were shared back with each group to ensure accuracy and relevance.

RESULTS

Participants

A total of 64 individuals participated (Table 1): hospital medicine physicians and residents (56%), inpatient nurses and ancillary staff (16%), and interpreters (28%). While 81% of physicians spoke multiple languages, only 25% reported speaking them well; two physicians were certified to communicate medical information without an interpreter present.

Themes Resulting from GLA Sessions

A total of four barriers (Table 2) and four drivers (Table 3) of effective communication with pediatric LEP patients and their families in the inpatient setting were identified by participants. Participants across all groups, despite enthusiasm around improving communication, were concerned about quality of care LEP families received, noting that the system is “designed to deliver less-good care” and that “we really haven’t figured out how to care for [LEP patients and families] in a [high-]quality and reliable way.” Variation in theme discussion was noted between groups based on participant role: physicians voiced concern about rapport with LEP families, nurses emphasized actionable tasks, and interpreters focused on heightened challenges in times of stress.

Barrier 1: Difficulties Accessing Interpreter Services

Medical providers (physicians and nurses) identified the “opaque process to access [interpreter] services” as one of their biggest challenges when communicating with LEP families. In particular, the process of scheduling interpreters was described as a “black box,” with physicians and nurses expressing difficulty determining if and when in-person interpreters were scheduled and uncertainty about when to use modalities other than in-person interpretation. Participants across groups highlighted the lack of systems knowledge from medical providers and limitations within the system that make predictable, timely, and reliable access to interpreters challenging, especially for uncommon languages. Medical providers desired more in-person interpreters who can “stay as long as clinically indicated,” citing frustration associated with using phone- and video-interpretation (eg, challenges locating technology, unfamiliarity with use, unreliable functionality of equipment). Interpreters voiced wanting to take time to finish each encounter fully without “being in a hurry because the next appointment is coming soon” or “rushing… in [to the next] session sweating.”

Barrier 2: Uncertainty in Communication with LEP Families

Participants across all groups described three areas of uncertainty as detailed in Table 2: (1) what to share and how to prioritize information during encounters with LEP patients and families, (2) what is communicated during interpretation, and (3) what LEP patients and families understand.

Barrier 3: Unclear and Inconsistent Expectations and Roles of Team Members

Given the complexity involved in communication between medical providers, interpreters, and families, participants across all groups reported feeling ill-prepared when navigating hospital encounters with LEP patients and families. Interpreters reported having little to no clinical context, medical providers reported having no knowledge of the assigned interpreter’s style, and both interpreters and medical providers reported that families have little idea of what to expect or how to engage. All groups voiced frustration about the lack of clarity regarding specific roles and scope of practice for each team member during an encounter, where multiple people end up “talking [or] using the interpreter at once.” Interpreters shared their expectations of medical providers to set the pace and lead conversations with LEP families. On the other hand, medical providers expressed a desire for interpreters to provide cultural context to the team without prompting and to interrupt during encounters when necessary to voice concerns or redirect conversations.

Barrier 4: Unmet Family Engagement Expectations

Participants across all groups articulated challenges with establishing rapport with LEP patients and families, sharing concerns that “inadequate communication” due to “cultural or language barriers” ultimately impacts quality of care. Participants reported decreased bidirectional engagement with and from LEP families. Medical providers not only noted difficulty in connecting with LEP families “on a more personal level” and providing frequent medical updates, but also felt that LEP families do not ask questions even when uncertain. Interpreters expressed concerns about medical providers “not [having] enough patience to answer families’ questions” while LEP families “shy away from asking questions.”

Driver 1: Utilizing a Team-Based Approach between Medical Providers and Interpreters

Participants from all groups emphasized that a mutual understanding of roles and shared expectations regarding communication and interpretation style, clinical context, and time constraints would establish a foundation for respect between medical providers and interpreters. They reported that a team-based approach to LEP patient and family encounters were crucial to achieving effective communication.

Driver 2: Understanding the Role of Cultural Context in Providing Culturally Effective Care.

Participants across all groups highlighted three different aspects of cultural context that drive effective communication: (1) medical providers’ perception of the family’s culture; (2) LEP families’ knowledge about the culture and healthcare system in the US, and (3) medical providers insight into their own preconceived ideas about LEP families.

Driver 3: Practicing Empathy for Patients and Families

All participants reported that respect for diversity and consideration of the backgrounds and perspectives of LEP patients and families are necessary. Furthermore, both medical providers and interpreters articulated a need to remain patient and mindful when interacting with LEP families despite challenges, especially since, as noted by interpreters, encounters may “take longer, but it’s for a reason.”

Driver 4: Using Effective Family-Centered Communication Strategies

Participants identified the use of effective family-centered communication principles as a driver to optimal communication. Many of the principles identified by medical providers and interpreters are generally applicable to all hospitalized patients and families regardless of English proficiency: optimizing verbal communication (eg, using shorter sentences, pausing to allow for interpretation), optimizing nonverbal communication (eg, setting, position, and body language), and assessment of family understanding and engagement (eg, use of teach back).

DISCUSSION

Frontline medical providers and interpreters identified barriers and drivers that impact communication with LEP patients and families during hospitalization. To our knowledge, this is the first study that uses a participatory method to explore the perspectives of medical providers and interpreters who care for LEP children and families in the inpatient setting. Despite existing difficulties and concerns regarding language barriers and its impact on quality of care for hospitalized LEP patients and families, participants were enthusiastic about how identified barriers and drivers may inform future improvement efforts. Notable action steps for future improvement discussed by our participants included: increased use and functionality of technology for timely and predictable access to interpreters, deliberate training for providers focused on delivery of culturally-effective care, consistent use of family-centered communication strategies including teach-back, and implementing interdisciplinary expectation setting through “presessions” before encounters with LEP families.

Participants elaborated on several barriers previously described in the literature including time constraints and technical problems.14,21,22 Such barriers may serve as deterrents to consistent and appropriate use of interpreters in healthcare settings.9 A heavy reliance on off-site interpreters (including phone- or video-interpreters) and lack of knowledge regarding resource availability likely amplified frustration for medical providers. Communication with LEP families can be daunting, especially when medical providers do not care for LEP families or work with interpreters on a regular basis.14 Standardizing the education of medical providers regarding available resources, as well as the logistics, process, and parameters for scheduling interpreters and using technology, was an action step identified by our GLA participants. Targeted education about the logistics of accessing interpreter services and having standardized ways to make technology use easier (ie, one-touch dialing in hospital rooms) has been associated with increased interpreter use and decreased interpreter-related delays in care.23

Our frontline medical providers expressed added concern about not spending as much time with LEP families. In fact, LEP families in the literature have perceived medical providers to spend less time with their children compared to their English-proficient counterparts.24 Language and cultural barriers, both perceived and real, may limit medical provider rapport with LEP patients and families14 and likely contribute to medical providers relying on their preconceived assumptions instead.25 Cultural competency education for medical providers, as highlighted by our GLA participants as an action item, can be used to provide more comprehensive and effective care.26,27

In addition to enhancing cultural humility through education, our participants emphasized the use of family-centered communication strategies as a driver of optimal family engagement and understanding. Actively inviting questions from families and utilizing teach-back, an established evidence-based strategy28-30 discussed by our participants, can be particularly powerful in assessing family understanding and engagement. While information should be presented in plain language for families in all encounters,31 these evidence-based practices are of particular importance when communicating with LEP families. They promote effective communication, empower families to share concerns in a structured manner, and allow medical providers to address matters in real-time with interpreters present.

Finally, our participants highlighted the need for partnerships between providers and interpreter services, noting unclear roles and expectations among interpreters and medical providers as a major barrier. Specifically, physicians noted confusion regarding the scope of an interpreter’s practice. Participants from GLA sessions discussed the importance of a team-based approach and suggested implementing a “presession” prior to encounters with LEP patients and families. Presessions—a concept well accepted among interpreters and recommended by consensus-based practice guidelines—enable medical providers and interpreters to establish shared expectations about scope of practice, communication, interpretation style, time constraints, and medical context prior to patient encounters.32,33

There are several limitations to our study. First, individuals who chose to participate were likely highly motivated by their clinical experiences with LEP patients and invested in improving communication with LEP families. Second, the study is limited in generalizability, as it was conducted at a single academic institution in a Midwestern city. Despite regional variations in available resources as well as patient and workforce demographics, our findings regarding major themes are in agreement with previously published literature and further add to our understanding of ways to improve communication with this vulnerable population across the care spectrum. Lastly, we were logistically limited in our ability to elicit the perspectives of LEP families due to the participatory nature of GLA; the need for multiple interpreters to simultaneously interact with LEP individuals would have not only hindered active LEP family participation but may have also biased the data generated by patients and families, as the services interpreters provide during their inpatient stay was the focus of our study. Engaging LEP families in their preferred language using participatory methods should be considered for future studies.

In conclusion, frontline providers of medical and language services identified barriers and drivers impacting the effective use of interpreter services when communicating with LEP families during hospitalization. Our enhanced understanding of barriers and drivers, as well as identified actionable interventions, will inform future improvement of communication and interactions with LEP families that contributes to effective and efficient family centered care. A framework for the development and implementation of organizational strategies aimed at improving communication with LEP families must include a thorough assessment of impact, feasibility, stakeholder involvement, and sustainability of specific interventions. While there is no simple formula to improve language services, health systems should establish and adopt language access policies, standardize communication practices, and develop processes to optimize the use of language services in the hospital. Furthermore, engagement with LEP families to better understand their perceptions and experiences with the healthcare system is crucial to improve communication between medical providers and LEP families in the inpatient setting and should be the subject of future studies.

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding

No external funding was secured for this study. Dr. Joanna Thomson is supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (Grant #K08 HS025138). Dr. Raglin Bignall was supported through a Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award (T32HP10027) when the study was conducted. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding organizations. The funding organizations had no role in the design, preparation, review, or approval of this paper.

1. The American Academy of Pediatrics Council on Community Pediatrics. Providing care for immigrant, migrant, and border children. Pediatrics. 2013;131(6):e2028-e2034. PubMed

2. Meneses C, Chilton L, Duffee J, et al. Council on Community Pediatrics Immigrant Health Tool Kit. The American Academy of Pediatrics. https://www.aap.org/en-us/Documents/cocp_toolkit_full.pdf. Accessed May 13, 2019.

3. Office for Civil Rights. Guidance to Federal Financial Assistance Recipients Regarding Title VI and the Prohibition Against National Origin Discrimination Affecting Limited English Proficient Persons. https://www.hhs.gov/civil-rights/for-individuals/special-topics/limited-english-proficiency/guidance-federal-financial-assistance-recipients-title-vi/index.html. Accessed May 13, 2019.

4. Lion KC, Rafton SA, Shafii J, et al. Association between language, serious adverse events, and length of stay Among hospitalized children. Hosp Pediatr. 2013;3(3):219-225. https://doi.org/10.1542/hpeds.2012-0091.

5. Lion KC, Wright DR, Desai AD, Mangione-Smith R. Costs of care for hospitalized children associated With preferred language and insurance type. Hosp Pediatr. 2017;7(2):70-78. https://doi.org/10.1542/hpeds.2016-0051.

6. Cohen AL, Rivara F, Marcuse EK, McPhillips H, Davis R. Are language barriers associated with serious medical events in hospitalized pediatric patients? Pediatrics. 2005;116(3):575-579. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2005-0521.

7. Samuels-Kalow ME, Stack AM, Amico K, Porter SC. Parental language and return visits to the Emergency Department After discharge. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2017;33(6):402-404. https://doi.org/10.1097/PEC.0000000000000592.

8. Unaka NI, Statile AM, Choe A, Shonna Yin H. Addressing health literacy in the inpatient setting. Curr Treat Options Pediatr. 2018;4(2):283-299. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40746-018-0122-3.

9. DeCamp LR, Kuo DZ, Flores G, O’Connor K, Minkovitz CS. Changes in language services use by US pediatricians. Pediatrics. 2013;132(2):e396-e406. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2012-2909.

10. Flores G. The impact of medical interpreter services on the quality of health care: A systematic review. Med Care Res Rev. 2005;62(3):255-299. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077558705275416.

11. Flores G, Abreu M, Barone CP, Bachur R, Lin H. Errors of medical interpretation and their potential clinical consequences: A comparison of professional versus hoc versus no interpreters. Ann Emerg Med. 2012;60(5):545-553. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2012.01.025.

12. Anand KJ, Sepanski RJ, Giles K, Shah SH, Juarez PD. Pediatric intensive care unit mortality among Latino children before and after a multilevel health care delivery intervention. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169(4):383-390. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.3789.

13. The Joint Commission. Advancing Effective Communication, Cultural Competence, and Patient- and Family-Centered Care: A Roadmap for Hospitals. Oakbrook Terrace, IL: The Joint Commission; 2010.

14. Hernandez RG, Cowden JD, Moon M et al. Predictors of resident satisfaction in caring for limited English proficient families: a multisite study. Acad Pediatr. 2014;14(2):173-180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2013.12.002.

15. Vaughn LM, Lohmueller M. Calling all stakeholders: group-level assessment (GLA)-a qualitative and participatory method for large groups. Eval Rev. 2014;38(4):336-355. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193841X14544903.

16. Vaughn LM, Jacquez F, Zhao J, Lang M. Partnering with students to explore the health needs of an ethnically diverse, low-resource school: an innovative large group assessment approach. Fam Commun Health. 2011;34(1):72-84. https://doi.org/10.1097/FCH.0b013e3181fded12.

17. Gosdin CH, Vaughn L. Perceptions of physician bedside handoff with nurse and family involvement. Hosp Pediatr. 2012;2(1):34-38. https://doi.org/10.1542/hpeds.2011-0008-2.

18. Graham KE, Schellinger AR, Vaughn LM. Developing strategies for positive change: transitioning foster youth to adulthood. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2015;54:71-79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2015.04.014.

19. Vaughn LM. Group level assessment: A Large Group Method for Identifying Primary Issues and Needs within a community. London2014. http://methods.sagepub.com/case/group-level-assessment-large-group-primary-issues-needs-community. Accessed 2017/07/26.

20. Association of American Medical Colleges Electronic Residency Application Service. ERAS 2018 MyERAS Application Worksheet: Language Fluency. Washington, DC:: Association of American Medical Colleges; 2018:5.

21. Brisset C, Leanza Y, Laforest K. Working with interpreters in health care: A systematic review and meta-ethnography of qualitative studies. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;91(2):131-140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2012.11.008.

22. Wiking E, Saleh-Stattin N, Johansson SE, Sundquist J. A description of some aspects of the triangular meeting between immigrant patients, their interpreters and GPs in primary health care in Stockholm, Sweden. Fam Pract. 2009;26(5):377-383. https://doi.org/10.1093/fampra/cmp052.

23. Lion KC, Ebel BE, Rafton S et al. Evaluation of a quality improvement intervention to increase use of telephonic interpretation. Pediatrics. 2015;135(3):e709-e716. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2014-2024.

24. Zurca AD, Fisher KR, Flor RJ, et al. Communication with limited English-proficient families in the PICU. Hosp Pediatr. 2017;7(1):9-15. https://doi.org/10.1542/hpeds.2016-0071.

25. Kodjo C. Cultural competence in clinician communication. Pediatr Rev. 2009;30(2):57-64. https://doi.org/10.1542/pir.30-2-57.

26. Britton CV, American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Pediatric Workforce. Ensuring culturally effective pediatric care: implications for education and health policy. Pediatrics. 2004;114(6):1677-1685. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2004-2091.

27. The American Academy of Pediatrics. Culturally Effective Care Toolkit: Providing Cuturally Effective Pediatric Care; 2018. https://www.aap.org/en-us/professional-resources/practice-transformation/managing-patients/Pages/effective-care.aspx. Accessed May 13, 2019.

28. Starmer AJ, Spector ND, Srivastava R, et al. Changes in medical errors after implementation of a handoff program. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(19):1803-1812. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa1405556.

29. Jager AJ, Wynia MK. Who gets a teach-back? Patient-reported incidence of experiencing a teach-back. J Health Commun. 2012;17 Supplement 3:294-302. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2012.712624.

30. Kornburger C, Gibson C, Sadowski S, Maletta K, Klingbeil C. Using “teach-back” to promote a safe transition from hospital to home: an evidence-based approach to improving the discharge process. J Pediatr Nurs. 2013;28(3):282-291. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedn.2012.10.007.

31. Abrams MA, Klass P, Dreyer BP. Health literacy and children: recommendations for action. Pediatrics. 2009;124 Supplement 3:S327-S331. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2009-1162I.

32. Betancourt JR, Renfrew MR, Green AR, Lopez L, Wasserman M. Improving Patient Safety Systems for Patients with Limited English Proficiency: a Guide for Hospitals. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2012. 33. The National Council on Interpreting in Health Care. Best Practices for Communicating Through an Interpreter . https://refugeehealthta.org/access-to-care/language-access/best-practices-communicating-through-an-interpreter/. Accessed May 19, 2019.

33. The National Council on Interpreting in Health Care. Best Practices for Communicating Through an Interpreter . https://refugeehealthta.org/access-to-care/language-access/best-practices-communicating-through-an-interpreter/. Accessed May 19, 2019.

1. The American Academy of Pediatrics Council on Community Pediatrics. Providing care for immigrant, migrant, and border children. Pediatrics. 2013;131(6):e2028-e2034. PubMed

2. Meneses C, Chilton L, Duffee J, et al. Council on Community Pediatrics Immigrant Health Tool Kit. The American Academy of Pediatrics. https://www.aap.org/en-us/Documents/cocp_toolkit_full.pdf. Accessed May 13, 2019.

3. Office for Civil Rights. Guidance to Federal Financial Assistance Recipients Regarding Title VI and the Prohibition Against National Origin Discrimination Affecting Limited English Proficient Persons. https://www.hhs.gov/civil-rights/for-individuals/special-topics/limited-english-proficiency/guidance-federal-financial-assistance-recipients-title-vi/index.html. Accessed May 13, 2019.

4. Lion KC, Rafton SA, Shafii J, et al. Association between language, serious adverse events, and length of stay Among hospitalized children. Hosp Pediatr. 2013;3(3):219-225. https://doi.org/10.1542/hpeds.2012-0091.

5. Lion KC, Wright DR, Desai AD, Mangione-Smith R. Costs of care for hospitalized children associated With preferred language and insurance type. Hosp Pediatr. 2017;7(2):70-78. https://doi.org/10.1542/hpeds.2016-0051.

6. Cohen AL, Rivara F, Marcuse EK, McPhillips H, Davis R. Are language barriers associated with serious medical events in hospitalized pediatric patients? Pediatrics. 2005;116(3):575-579. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2005-0521.

7. Samuels-Kalow ME, Stack AM, Amico K, Porter SC. Parental language and return visits to the Emergency Department After discharge. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2017;33(6):402-404. https://doi.org/10.1097/PEC.0000000000000592.

8. Unaka NI, Statile AM, Choe A, Shonna Yin H. Addressing health literacy in the inpatient setting. Curr Treat Options Pediatr. 2018;4(2):283-299. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40746-018-0122-3.

9. DeCamp LR, Kuo DZ, Flores G, O’Connor K, Minkovitz CS. Changes in language services use by US pediatricians. Pediatrics. 2013;132(2):e396-e406. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2012-2909.

10. Flores G. The impact of medical interpreter services on the quality of health care: A systematic review. Med Care Res Rev. 2005;62(3):255-299. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077558705275416.

11. Flores G, Abreu M, Barone CP, Bachur R, Lin H. Errors of medical interpretation and their potential clinical consequences: A comparison of professional versus hoc versus no interpreters. Ann Emerg Med. 2012;60(5):545-553. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2012.01.025.

12. Anand KJ, Sepanski RJ, Giles K, Shah SH, Juarez PD. Pediatric intensive care unit mortality among Latino children before and after a multilevel health care delivery intervention. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169(4):383-390. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.3789.

13. The Joint Commission. Advancing Effective Communication, Cultural Competence, and Patient- and Family-Centered Care: A Roadmap for Hospitals. Oakbrook Terrace, IL: The Joint Commission; 2010.

14. Hernandez RG, Cowden JD, Moon M et al. Predictors of resident satisfaction in caring for limited English proficient families: a multisite study. Acad Pediatr. 2014;14(2):173-180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2013.12.002.

15. Vaughn LM, Lohmueller M. Calling all stakeholders: group-level assessment (GLA)-a qualitative and participatory method for large groups. Eval Rev. 2014;38(4):336-355. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193841X14544903.

16. Vaughn LM, Jacquez F, Zhao J, Lang M. Partnering with students to explore the health needs of an ethnically diverse, low-resource school: an innovative large group assessment approach. Fam Commun Health. 2011;34(1):72-84. https://doi.org/10.1097/FCH.0b013e3181fded12.

17. Gosdin CH, Vaughn L. Perceptions of physician bedside handoff with nurse and family involvement. Hosp Pediatr. 2012;2(1):34-38. https://doi.org/10.1542/hpeds.2011-0008-2.

18. Graham KE, Schellinger AR, Vaughn LM. Developing strategies for positive change: transitioning foster youth to adulthood. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2015;54:71-79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2015.04.014.