User login

Technique of Open Reduction and Internal Fixation of Comminuted Proximal Humerus Fractures With Allograft Femoral Head Metaphyseal Reconstruction

Proximal humerus fractures are exceedingly common and account for almost 5% of all fractures. As osteoporosis is a risk factor for these fractures, their incidence rises with patient age.1

In 1970, Neer2 described these type of fractures and classified them as having 2, 3, or 4 parts based on the amount of angulation and displacement of the humeral head and the greater and lesser tuberosities with respect to the shaft.

Three- and 4-part proximal humerus fractures can be treated either nonoperatively, or surgically with closed reduction and percutaneous fixation, intramedullary fixation, open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF), or arthroplasty. There remains controversy over the best treatment, but a key component of any surgical treatment is anatomical reduction, stable fixation, and then healing of the tuberosities. A current common form of treatment is augmentation with an allograft fibula placed in the medullary canal. Although not formally reported, anecdotal evidence demonstrates that revision to arthroplasty is very difficult in the setting of an ingrown graft in the medullary canal of the humerus.

In this article, we present a novel technique of using allograft femoral head to reconstruct the metaphysis in ORIF of comminuted proximal humerus fractures.

Technique

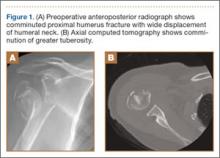

Presented in Figure 1 are preoperative images of a representative displaced 4-part proximal humerus fracture treated surgically using the technique described here. General anesthesia is used. After intubation on the operating table, the patient is placed in the beach-chair position with about 75° of hip flexion. All bony prominences are padded, and the head and trunk are well secured. A pneumatic arm positioner is used to alleviate the need for an assistant to manipulate the arm. An image intensifier is used before preparing to verify that appropriate images of the proximal humerus can be obtained. Once adequate images are confirmed, the floor can be marked at the position of the fluoroscopic unit’s wheels to allow easy reproduction of images once the arm is prepared and draped. The intensifier is then removed from the field, the shoulder is prepared and draped in usual fashion, and prophylactic antibiotics are administered.

A deltopectoral incision is used, and sharp dissection is made through the subcutaneous tissue to raise full-thickness subcutaneous flaps on each side. The deltopectoral interval is sharply dissected while protecting the cephalic vein. Subdeltoid adhesions are then released. Palpation of the axillary nerve in the quadrilateral space to identify its location is helpful to avoid injury during the procedure.

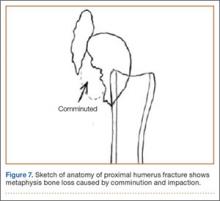

The fracture is then identified, and No. 5 permanent suture is placed through the posterior and superior rotator cuff and through the subscapularis insertion (Figure 2). The tuberosities are freed from the humeral head sharply. A blunt elevator is then used to gently elevate the humeral head upward, with care taken to avoid comminuting the metaphyseal bone while levering. Reduction is achieved by manipulating the sutures and levering the head with the elevator while placing the arm in extension and posterior translation. Fluoroscopic images are used to verify correct anatomical alignment. Generally, the metaphysis demonstrates comminution and impaction, with poor bone quality necessitating use of bone graft.

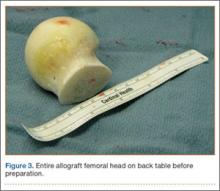

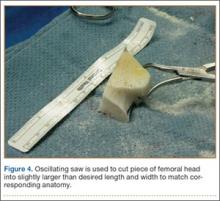

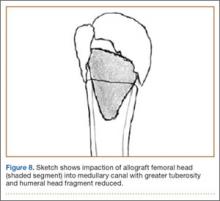

A frozen allograft femoral head is then obtained and split into 2 equal pieces using a saw (Figures 3–5). One piece is fashioned with a saw and a burr into a trapezoid such that the proximal portion is wider, and the distal, tapered portion is sized to fit the canal. The broad, proximal portion of the graft will serve as a pedestal to reduce the head to the shaft. Measuring the internal diameter of the humeral canal can be useful in estimating the necessary dimensions of the distal portion of the allograft. The graft often needs several small adjustments that necessitate attempting to place it in the intramedullary canal and then trimming as necessary to ensure proper fit distally within the shaft. For this reason, it is beneficial to perform the graft preparation near the surgical field. Once completed, the distal portion is then impacted into the humeral canal (Figure 6). Because of this impaction, there is no possibility for subsidence or pistoning of the graft within the canal, which can occur with a fibular graft. The humeral head is reduced onto the shaft with the already placed sutures; this is achieved by abducting the shoulder. The image intensifier is then used to confirm appropriate alignment and positioning of the fragments, making sure that both neck–shaft angle and medial calcar alignment have been restored (Figures 7, 8).

An appropriately sized proximal humerus plate is then selected based on the location of the fracture line. We have used standard lateral proximal humerus locking plates as well as laterality-specific anterolateral proximal humerus plates and found that both are suitable for incorporation of the screws through the graft and into the head. The plate is positioned on the humerus, and a guide pin is placed by hand through the proximal-most hole so that the appropriate height of the plate can be verified on fluoroscopy. The first screw is then a nonlocking bicortical screw placed through the oval hole in the shaft of the plate to allow further fine manipulation of the plate more proximally or distally as needed. The final height is confirmed, and the screw is firmly tightened (Figure 9). The locking-screw guide is fixed to the proximal portion of the plate, and 2 locking screws are then placed into the head. The arm is then rotated to an anteroposterior view by placing the arm in external rotation and neutral flexion and is then abducted and internally rotated to recreate a lateral view to perform final verification of the position of the plate on orthogonal images. If the surgeon is satisfied with the position of the plate, another nonlocking screw is placed distally, and then the proximal holes are used to place locking screws as needed. If the surgeon is not satisfied, the 2 proximal screws can be removed and the plate repositioned.

After each screw is placed, fluoroscopy is used to ensure there has been no breach of the articular surface. The number of proximal screws placed depends on fracture configuration and surgeon preference.

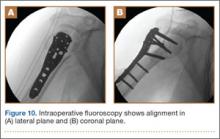

The sutures through the rotator cuff are then fixed to the plate, securing the tuberosities. Final intraoperative radiographs are used to confirm reduction, alignment, and final position of hardware (Figure 10). After copious irrigation, a surgical drain is placed as needed, and the wound is closed in layered fashion. Three years after surgery, follow-up examination revealed no radiographic change in alignment, no necrosis, and no varus collapse (Figure 11), and the patient was pain-free during activities.

Discussion

Surgical treatment of comminuted proximal humerus fractures usually consists of some type of plate fixation with screw fixation of the shaft, screws or smooth pegs to support the chondral surfaces, and screw fixation or suture cerclage of the tuberosities.

Fixed-angle locking-plate-and-screw constructs increased the biomechanical stability and pullout strength of proximal humerus plates.3,4 Nevertheless, avascular necrosis, malunion, and nonunion are still known complications of proximal humerus fractures, especially those with comminution, with up to 14% of patients still experiencing loss of fixation.5

For this reason, several authors have proposed using allograft bone and/or augmentation with calcium-containing cement to supplement fixation and provide an endosteal form of support for the head and tuberosities to decrease the risk for varus collapse. Osteobiologics (eg, calcium phosphate or sulfate cement) have been shown to decrease the risk for loss of reduction of proximal humerus fractures and decrease the risk for intra-articular screw penetration.6,7 Many calcium phosphate cements are commercially available. Cost and availability are 2 reasons that these supplements are not more widely used. Cancellous chips have also been used to aid in the reduction of proximal humerus fractures.8 No randomized study has been conducted to show a clinical advantage of this technique, though retrospective studies have shown that it is not as advantageous as using calcium phosphate cement with respect to loss of reduction or screw penetration.6 Certainly, cancellous chips are easily available in most hospitals and are less expensive than some alternatives. A recent review of these techniques in osteoporotic proximal humerus fractures found no clear indication for using one of these supplements over another.9

However, some fracture patterns require a structural graft to reduce the tuberosities and head component. Although described more than 30 years ago as a treatment for nonunions with an intramedullary “peg” of iliac crest graft,10 the graft most commonly reported today is allograft fibula.11-15 This technique consists of preparing the humeral shaft and often the fractured head segment with reaming to create a channel to receive the graft. Even with use of a small fibula, it is often time-consuming to use a saw, rasp, or burr to size the fibular segment to fit the medullary canal of the humerus. Once in place, the graft provides a strut on which the head fragment can be reduced and around which the tuberosities can be reduced. Although this technique is successful clinically and is biomechanically superior to plate-only constructs,16,17 concerns remain.

One such concern is keeping this graft in routine supply at most hospitals. Supply and pricing from vendors can differ significantly between hospitals, and a surgeon may need to request grafts in advance, which makes their use nonviable in a trauma case. Certain grafts are often kept in routine supply based on their overall utilization. At our institution, allograft femoral heads meet this criterion and are routinely stocked.

Of more importance are the ramifications of these procedures for future revision surgeries. The need for arthroplasty revision is common after ORIF of a proximal humerus fracture.18

Arthroplasty revision is an already challenging procedure that becomes more complex with the need to remove 6 to 8 cm of ingrown endosteal bone from a shell of outer osteoporotic cortical bone. Our experience with these complex revisions provided the impetus to search for an alternate graft type that still provides a strut for reducing the head and tuberosities but limits the amount of endosteal bone that would need to be removed in arthroplasty revision in order to place a stemmed component into the humeral canal.

Some currently available arthroplasty fracture systems modify the previous anatomy of the stem to provide a more anatomical platform to reduce the tuberosities to a broader metaphyseal construct that incorporates bone grafting to assist with healing.

Because of these concerns and factors, we adapted our technique to create an individual-specific pedestal with allograft femoral head that can be anatomically matched to each patient. This provides a strut to reduce the head and tuberosity fragments but still limits the amount of allograft bone needed to seat into the existing canal. The geometry of the allograft can also be customized to the fracture, with most 3- and 4-part fractures needing a trapezoidal strut that resembles the metaphyseal portion of a fracture-specific shoulder arthroplasty implant.

We have used this technique for comminuted 3- and 4-part fractures of the proximal humerus in 14 cases with at least 2-year follow-up and in several more cases that have not reached 2-year follow-up. All cases have gone on to radiographic union; none have had to be revised either with revision ORIF or to an arthroplasty. Formal measurements of final postoperative range of motion have not been tabulated in all cases, as some cases have been lost to follow-up after radiographic union was achieved. Medium- and long-term results are not yet available, but no short-term complications have been noted.

Disadvantages of this technique are that, while an individualized graft is created, proper shaping still takes time, and a moderate amount of the femoral head is not used. However, we have found that, if a graft is inadvertently undersized, there is still ample femoral head remaining to create another sized graft. Other disadvantages are the added cost and the (rare) risk of disease transmission, which come with use of any allograft, but the technique is used instead of another type of allograft, so these disadvantages are largely equivalent. At our hospital, differences in cost and availability between femoral head or fibular allografts are negligible.

This procedure, which is easily performed in a short amount of time, allows a stable base of bone graft to be used as an aid in the anatomical reduction of proximal humerus fractures, without the need for reaming and preparation of the medullary canal and without further increasing the difficulty associated with a future revision procedure.

1. Barrett JA, Baron JA, Karagas MR, Beach ML. Fracture risk in the U.S. Medicare population. J Clin Epidemiol. 1999;52(3):243-249.

2. Neer CS 2nd. Displaced proximal humeral fractures. I. Classification and evaluation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1970;52(6):1077-1089.

3. Liew AS, Johnson JA, Patterson SD, King GJ, Chess DG. Effect of screw placement on fixation in the humeral head. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2000;9(5):423-426.

4. Weinstein DM, Bratton DR, Ciccone WJ 2nd, Elias JJ. Locking plates improve torsional resistance in the stabilization of three-part proximal humeral fractures. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2006;15(2):239-243.

5. Agudelo J, Schurmann M, Stahel P, et al. Analysis of efficacy and failure in proximal humerus fractures treated with locking plates. J Orthop Trauma. 2007;21(10):676-681.

6. Egol KA, Sugi MT, Ong CC, Montero N, Davidovitch R, Zuckerman JD. Fracture site augmentation with calcium phosphate cement reduces screw penetration after open reduction-internal fixation of proximal humeral fractures. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(6):741-748.

7. Gradl G, Knobe M, Stoffel M, Prescher A, Dirrichs T, Pape HC. Biomechanical evaluation of locking plate fixation of proximal humeral fractures augmented with calcium phosphate cement. J Orthop Trauma. 2013;27(7):399-404.

8. Ong CC, Kwon YW, Walsh M, Davidovitch R, Zuckerman JD, Egol KA. Outcomes of open reduction and internal fixation of proximal humerus fractures managed with locking plates. Am J Orthop. 2012;41(9):407-412.

9. Namdari S, Voleti PB, Mehta S. Evaluation of the osteoporotic proximal humeral fracture and strategies for structural augmentation during surgical treatment. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(12):1787-1795.

10. Scheck M. Surgical treatment of nonunions of the surgical neck of the humerus. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1982;(167):255-259.

11. Hettrich CM, Neviaser A, Beamer BS, Paul O, Helfet DL, Lorich DG. Locked plating of the proximal humerus using an endosteal implant. J Orthop Trauma. 2012;26(4):212-215.

12. Neviaser AS, Hettrich CM, Beamer BS, Dines JS, Lorich DG. Endosteal strut augment reduces complications associated with proximal humeral locking plates. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469(12):3300-3306.

13. Gardner MJ, Boraiah S, Helfet DL, Lorich DG. Indirect medial reduction and strut support of proximal humerus fractures using an endosteal implant. J Orthop Trauma. 2008;22(3):195-200.

14. Matassi F, Angeloni R, Carulli C, et al. Locking plate and fibular allograft augmentation in unstable fractures of proximal humerus. Injury. 2012;43(11):1939-1942.

15. Little MT, Berkes MB, Schottel PC, et al. The impact of preoperative coronal plane deformity on proximal humerus fixation with endosteal augmentation. J Orthop Trauma. 2014;28(6):338-347.

16. Mathison C, Chaudhary R, Beaupre L, Reynolds M, Adeeb S, Bouliane M. Biomechanical analysis of proximal humeral fixation using locking plate fixation with an intramedullary fibular allograft. Clin Biomech. 2010;25(7):642-646.

17. Chow RM, Begum F, Beaupre LA, Carey JP, Adeeb S, Bouliane MJ. Proximal humeral fracture fixation: locking plate construct +/- intramedullary fibular allograft. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(7):894-901.

18. Jost B, Spross C, Grehn H, Gerber C. Locking plate fixation of fractures of the proximal humerus: analysis of complications, revision strategies and outcome. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22(4):542-549.

Proximal humerus fractures are exceedingly common and account for almost 5% of all fractures. As osteoporosis is a risk factor for these fractures, their incidence rises with patient age.1

In 1970, Neer2 described these type of fractures and classified them as having 2, 3, or 4 parts based on the amount of angulation and displacement of the humeral head and the greater and lesser tuberosities with respect to the shaft.

Three- and 4-part proximal humerus fractures can be treated either nonoperatively, or surgically with closed reduction and percutaneous fixation, intramedullary fixation, open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF), or arthroplasty. There remains controversy over the best treatment, but a key component of any surgical treatment is anatomical reduction, stable fixation, and then healing of the tuberosities. A current common form of treatment is augmentation with an allograft fibula placed in the medullary canal. Although not formally reported, anecdotal evidence demonstrates that revision to arthroplasty is very difficult in the setting of an ingrown graft in the medullary canal of the humerus.

In this article, we present a novel technique of using allograft femoral head to reconstruct the metaphysis in ORIF of comminuted proximal humerus fractures.

Technique

Presented in Figure 1 are preoperative images of a representative displaced 4-part proximal humerus fracture treated surgically using the technique described here. General anesthesia is used. After intubation on the operating table, the patient is placed in the beach-chair position with about 75° of hip flexion. All bony prominences are padded, and the head and trunk are well secured. A pneumatic arm positioner is used to alleviate the need for an assistant to manipulate the arm. An image intensifier is used before preparing to verify that appropriate images of the proximal humerus can be obtained. Once adequate images are confirmed, the floor can be marked at the position of the fluoroscopic unit’s wheels to allow easy reproduction of images once the arm is prepared and draped. The intensifier is then removed from the field, the shoulder is prepared and draped in usual fashion, and prophylactic antibiotics are administered.

A deltopectoral incision is used, and sharp dissection is made through the subcutaneous tissue to raise full-thickness subcutaneous flaps on each side. The deltopectoral interval is sharply dissected while protecting the cephalic vein. Subdeltoid adhesions are then released. Palpation of the axillary nerve in the quadrilateral space to identify its location is helpful to avoid injury during the procedure.

The fracture is then identified, and No. 5 permanent suture is placed through the posterior and superior rotator cuff and through the subscapularis insertion (Figure 2). The tuberosities are freed from the humeral head sharply. A blunt elevator is then used to gently elevate the humeral head upward, with care taken to avoid comminuting the metaphyseal bone while levering. Reduction is achieved by manipulating the sutures and levering the head with the elevator while placing the arm in extension and posterior translation. Fluoroscopic images are used to verify correct anatomical alignment. Generally, the metaphysis demonstrates comminution and impaction, with poor bone quality necessitating use of bone graft.

A frozen allograft femoral head is then obtained and split into 2 equal pieces using a saw (Figures 3–5). One piece is fashioned with a saw and a burr into a trapezoid such that the proximal portion is wider, and the distal, tapered portion is sized to fit the canal. The broad, proximal portion of the graft will serve as a pedestal to reduce the head to the shaft. Measuring the internal diameter of the humeral canal can be useful in estimating the necessary dimensions of the distal portion of the allograft. The graft often needs several small adjustments that necessitate attempting to place it in the intramedullary canal and then trimming as necessary to ensure proper fit distally within the shaft. For this reason, it is beneficial to perform the graft preparation near the surgical field. Once completed, the distal portion is then impacted into the humeral canal (Figure 6). Because of this impaction, there is no possibility for subsidence or pistoning of the graft within the canal, which can occur with a fibular graft. The humeral head is reduced onto the shaft with the already placed sutures; this is achieved by abducting the shoulder. The image intensifier is then used to confirm appropriate alignment and positioning of the fragments, making sure that both neck–shaft angle and medial calcar alignment have been restored (Figures 7, 8).

An appropriately sized proximal humerus plate is then selected based on the location of the fracture line. We have used standard lateral proximal humerus locking plates as well as laterality-specific anterolateral proximal humerus plates and found that both are suitable for incorporation of the screws through the graft and into the head. The plate is positioned on the humerus, and a guide pin is placed by hand through the proximal-most hole so that the appropriate height of the plate can be verified on fluoroscopy. The first screw is then a nonlocking bicortical screw placed through the oval hole in the shaft of the plate to allow further fine manipulation of the plate more proximally or distally as needed. The final height is confirmed, and the screw is firmly tightened (Figure 9). The locking-screw guide is fixed to the proximal portion of the plate, and 2 locking screws are then placed into the head. The arm is then rotated to an anteroposterior view by placing the arm in external rotation and neutral flexion and is then abducted and internally rotated to recreate a lateral view to perform final verification of the position of the plate on orthogonal images. If the surgeon is satisfied with the position of the plate, another nonlocking screw is placed distally, and then the proximal holes are used to place locking screws as needed. If the surgeon is not satisfied, the 2 proximal screws can be removed and the plate repositioned.

After each screw is placed, fluoroscopy is used to ensure there has been no breach of the articular surface. The number of proximal screws placed depends on fracture configuration and surgeon preference.

The sutures through the rotator cuff are then fixed to the plate, securing the tuberosities. Final intraoperative radiographs are used to confirm reduction, alignment, and final position of hardware (Figure 10). After copious irrigation, a surgical drain is placed as needed, and the wound is closed in layered fashion. Three years after surgery, follow-up examination revealed no radiographic change in alignment, no necrosis, and no varus collapse (Figure 11), and the patient was pain-free during activities.

Discussion

Surgical treatment of comminuted proximal humerus fractures usually consists of some type of plate fixation with screw fixation of the shaft, screws or smooth pegs to support the chondral surfaces, and screw fixation or suture cerclage of the tuberosities.

Fixed-angle locking-plate-and-screw constructs increased the biomechanical stability and pullout strength of proximal humerus plates.3,4 Nevertheless, avascular necrosis, malunion, and nonunion are still known complications of proximal humerus fractures, especially those with comminution, with up to 14% of patients still experiencing loss of fixation.5

For this reason, several authors have proposed using allograft bone and/or augmentation with calcium-containing cement to supplement fixation and provide an endosteal form of support for the head and tuberosities to decrease the risk for varus collapse. Osteobiologics (eg, calcium phosphate or sulfate cement) have been shown to decrease the risk for loss of reduction of proximal humerus fractures and decrease the risk for intra-articular screw penetration.6,7 Many calcium phosphate cements are commercially available. Cost and availability are 2 reasons that these supplements are not more widely used. Cancellous chips have also been used to aid in the reduction of proximal humerus fractures.8 No randomized study has been conducted to show a clinical advantage of this technique, though retrospective studies have shown that it is not as advantageous as using calcium phosphate cement with respect to loss of reduction or screw penetration.6 Certainly, cancellous chips are easily available in most hospitals and are less expensive than some alternatives. A recent review of these techniques in osteoporotic proximal humerus fractures found no clear indication for using one of these supplements over another.9

However, some fracture patterns require a structural graft to reduce the tuberosities and head component. Although described more than 30 years ago as a treatment for nonunions with an intramedullary “peg” of iliac crest graft,10 the graft most commonly reported today is allograft fibula.11-15 This technique consists of preparing the humeral shaft and often the fractured head segment with reaming to create a channel to receive the graft. Even with use of a small fibula, it is often time-consuming to use a saw, rasp, or burr to size the fibular segment to fit the medullary canal of the humerus. Once in place, the graft provides a strut on which the head fragment can be reduced and around which the tuberosities can be reduced. Although this technique is successful clinically and is biomechanically superior to plate-only constructs,16,17 concerns remain.

One such concern is keeping this graft in routine supply at most hospitals. Supply and pricing from vendors can differ significantly between hospitals, and a surgeon may need to request grafts in advance, which makes their use nonviable in a trauma case. Certain grafts are often kept in routine supply based on their overall utilization. At our institution, allograft femoral heads meet this criterion and are routinely stocked.

Of more importance are the ramifications of these procedures for future revision surgeries. The need for arthroplasty revision is common after ORIF of a proximal humerus fracture.18

Arthroplasty revision is an already challenging procedure that becomes more complex with the need to remove 6 to 8 cm of ingrown endosteal bone from a shell of outer osteoporotic cortical bone. Our experience with these complex revisions provided the impetus to search for an alternate graft type that still provides a strut for reducing the head and tuberosities but limits the amount of endosteal bone that would need to be removed in arthroplasty revision in order to place a stemmed component into the humeral canal.

Some currently available arthroplasty fracture systems modify the previous anatomy of the stem to provide a more anatomical platform to reduce the tuberosities to a broader metaphyseal construct that incorporates bone grafting to assist with healing.

Because of these concerns and factors, we adapted our technique to create an individual-specific pedestal with allograft femoral head that can be anatomically matched to each patient. This provides a strut to reduce the head and tuberosity fragments but still limits the amount of allograft bone needed to seat into the existing canal. The geometry of the allograft can also be customized to the fracture, with most 3- and 4-part fractures needing a trapezoidal strut that resembles the metaphyseal portion of a fracture-specific shoulder arthroplasty implant.

We have used this technique for comminuted 3- and 4-part fractures of the proximal humerus in 14 cases with at least 2-year follow-up and in several more cases that have not reached 2-year follow-up. All cases have gone on to radiographic union; none have had to be revised either with revision ORIF or to an arthroplasty. Formal measurements of final postoperative range of motion have not been tabulated in all cases, as some cases have been lost to follow-up after radiographic union was achieved. Medium- and long-term results are not yet available, but no short-term complications have been noted.

Disadvantages of this technique are that, while an individualized graft is created, proper shaping still takes time, and a moderate amount of the femoral head is not used. However, we have found that, if a graft is inadvertently undersized, there is still ample femoral head remaining to create another sized graft. Other disadvantages are the added cost and the (rare) risk of disease transmission, which come with use of any allograft, but the technique is used instead of another type of allograft, so these disadvantages are largely equivalent. At our hospital, differences in cost and availability between femoral head or fibular allografts are negligible.

This procedure, which is easily performed in a short amount of time, allows a stable base of bone graft to be used as an aid in the anatomical reduction of proximal humerus fractures, without the need for reaming and preparation of the medullary canal and without further increasing the difficulty associated with a future revision procedure.

Proximal humerus fractures are exceedingly common and account for almost 5% of all fractures. As osteoporosis is a risk factor for these fractures, their incidence rises with patient age.1

In 1970, Neer2 described these type of fractures and classified them as having 2, 3, or 4 parts based on the amount of angulation and displacement of the humeral head and the greater and lesser tuberosities with respect to the shaft.

Three- and 4-part proximal humerus fractures can be treated either nonoperatively, or surgically with closed reduction and percutaneous fixation, intramedullary fixation, open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF), or arthroplasty. There remains controversy over the best treatment, but a key component of any surgical treatment is anatomical reduction, stable fixation, and then healing of the tuberosities. A current common form of treatment is augmentation with an allograft fibula placed in the medullary canal. Although not formally reported, anecdotal evidence demonstrates that revision to arthroplasty is very difficult in the setting of an ingrown graft in the medullary canal of the humerus.

In this article, we present a novel technique of using allograft femoral head to reconstruct the metaphysis in ORIF of comminuted proximal humerus fractures.

Technique

Presented in Figure 1 are preoperative images of a representative displaced 4-part proximal humerus fracture treated surgically using the technique described here. General anesthesia is used. After intubation on the operating table, the patient is placed in the beach-chair position with about 75° of hip flexion. All bony prominences are padded, and the head and trunk are well secured. A pneumatic arm positioner is used to alleviate the need for an assistant to manipulate the arm. An image intensifier is used before preparing to verify that appropriate images of the proximal humerus can be obtained. Once adequate images are confirmed, the floor can be marked at the position of the fluoroscopic unit’s wheels to allow easy reproduction of images once the arm is prepared and draped. The intensifier is then removed from the field, the shoulder is prepared and draped in usual fashion, and prophylactic antibiotics are administered.

A deltopectoral incision is used, and sharp dissection is made through the subcutaneous tissue to raise full-thickness subcutaneous flaps on each side. The deltopectoral interval is sharply dissected while protecting the cephalic vein. Subdeltoid adhesions are then released. Palpation of the axillary nerve in the quadrilateral space to identify its location is helpful to avoid injury during the procedure.

The fracture is then identified, and No. 5 permanent suture is placed through the posterior and superior rotator cuff and through the subscapularis insertion (Figure 2). The tuberosities are freed from the humeral head sharply. A blunt elevator is then used to gently elevate the humeral head upward, with care taken to avoid comminuting the metaphyseal bone while levering. Reduction is achieved by manipulating the sutures and levering the head with the elevator while placing the arm in extension and posterior translation. Fluoroscopic images are used to verify correct anatomical alignment. Generally, the metaphysis demonstrates comminution and impaction, with poor bone quality necessitating use of bone graft.

A frozen allograft femoral head is then obtained and split into 2 equal pieces using a saw (Figures 3–5). One piece is fashioned with a saw and a burr into a trapezoid such that the proximal portion is wider, and the distal, tapered portion is sized to fit the canal. The broad, proximal portion of the graft will serve as a pedestal to reduce the head to the shaft. Measuring the internal diameter of the humeral canal can be useful in estimating the necessary dimensions of the distal portion of the allograft. The graft often needs several small adjustments that necessitate attempting to place it in the intramedullary canal and then trimming as necessary to ensure proper fit distally within the shaft. For this reason, it is beneficial to perform the graft preparation near the surgical field. Once completed, the distal portion is then impacted into the humeral canal (Figure 6). Because of this impaction, there is no possibility for subsidence or pistoning of the graft within the canal, which can occur with a fibular graft. The humeral head is reduced onto the shaft with the already placed sutures; this is achieved by abducting the shoulder. The image intensifier is then used to confirm appropriate alignment and positioning of the fragments, making sure that both neck–shaft angle and medial calcar alignment have been restored (Figures 7, 8).

An appropriately sized proximal humerus plate is then selected based on the location of the fracture line. We have used standard lateral proximal humerus locking plates as well as laterality-specific anterolateral proximal humerus plates and found that both are suitable for incorporation of the screws through the graft and into the head. The plate is positioned on the humerus, and a guide pin is placed by hand through the proximal-most hole so that the appropriate height of the plate can be verified on fluoroscopy. The first screw is then a nonlocking bicortical screw placed through the oval hole in the shaft of the plate to allow further fine manipulation of the plate more proximally or distally as needed. The final height is confirmed, and the screw is firmly tightened (Figure 9). The locking-screw guide is fixed to the proximal portion of the plate, and 2 locking screws are then placed into the head. The arm is then rotated to an anteroposterior view by placing the arm in external rotation and neutral flexion and is then abducted and internally rotated to recreate a lateral view to perform final verification of the position of the plate on orthogonal images. If the surgeon is satisfied with the position of the plate, another nonlocking screw is placed distally, and then the proximal holes are used to place locking screws as needed. If the surgeon is not satisfied, the 2 proximal screws can be removed and the plate repositioned.

After each screw is placed, fluoroscopy is used to ensure there has been no breach of the articular surface. The number of proximal screws placed depends on fracture configuration and surgeon preference.

The sutures through the rotator cuff are then fixed to the plate, securing the tuberosities. Final intraoperative radiographs are used to confirm reduction, alignment, and final position of hardware (Figure 10). After copious irrigation, a surgical drain is placed as needed, and the wound is closed in layered fashion. Three years after surgery, follow-up examination revealed no radiographic change in alignment, no necrosis, and no varus collapse (Figure 11), and the patient was pain-free during activities.

Discussion

Surgical treatment of comminuted proximal humerus fractures usually consists of some type of plate fixation with screw fixation of the shaft, screws or smooth pegs to support the chondral surfaces, and screw fixation or suture cerclage of the tuberosities.

Fixed-angle locking-plate-and-screw constructs increased the biomechanical stability and pullout strength of proximal humerus plates.3,4 Nevertheless, avascular necrosis, malunion, and nonunion are still known complications of proximal humerus fractures, especially those with comminution, with up to 14% of patients still experiencing loss of fixation.5

For this reason, several authors have proposed using allograft bone and/or augmentation with calcium-containing cement to supplement fixation and provide an endosteal form of support for the head and tuberosities to decrease the risk for varus collapse. Osteobiologics (eg, calcium phosphate or sulfate cement) have been shown to decrease the risk for loss of reduction of proximal humerus fractures and decrease the risk for intra-articular screw penetration.6,7 Many calcium phosphate cements are commercially available. Cost and availability are 2 reasons that these supplements are not more widely used. Cancellous chips have also been used to aid in the reduction of proximal humerus fractures.8 No randomized study has been conducted to show a clinical advantage of this technique, though retrospective studies have shown that it is not as advantageous as using calcium phosphate cement with respect to loss of reduction or screw penetration.6 Certainly, cancellous chips are easily available in most hospitals and are less expensive than some alternatives. A recent review of these techniques in osteoporotic proximal humerus fractures found no clear indication for using one of these supplements over another.9

However, some fracture patterns require a structural graft to reduce the tuberosities and head component. Although described more than 30 years ago as a treatment for nonunions with an intramedullary “peg” of iliac crest graft,10 the graft most commonly reported today is allograft fibula.11-15 This technique consists of preparing the humeral shaft and often the fractured head segment with reaming to create a channel to receive the graft. Even with use of a small fibula, it is often time-consuming to use a saw, rasp, or burr to size the fibular segment to fit the medullary canal of the humerus. Once in place, the graft provides a strut on which the head fragment can be reduced and around which the tuberosities can be reduced. Although this technique is successful clinically and is biomechanically superior to plate-only constructs,16,17 concerns remain.

One such concern is keeping this graft in routine supply at most hospitals. Supply and pricing from vendors can differ significantly between hospitals, and a surgeon may need to request grafts in advance, which makes their use nonviable in a trauma case. Certain grafts are often kept in routine supply based on their overall utilization. At our institution, allograft femoral heads meet this criterion and are routinely stocked.

Of more importance are the ramifications of these procedures for future revision surgeries. The need for arthroplasty revision is common after ORIF of a proximal humerus fracture.18

Arthroplasty revision is an already challenging procedure that becomes more complex with the need to remove 6 to 8 cm of ingrown endosteal bone from a shell of outer osteoporotic cortical bone. Our experience with these complex revisions provided the impetus to search for an alternate graft type that still provides a strut for reducing the head and tuberosities but limits the amount of endosteal bone that would need to be removed in arthroplasty revision in order to place a stemmed component into the humeral canal.

Some currently available arthroplasty fracture systems modify the previous anatomy of the stem to provide a more anatomical platform to reduce the tuberosities to a broader metaphyseal construct that incorporates bone grafting to assist with healing.

Because of these concerns and factors, we adapted our technique to create an individual-specific pedestal with allograft femoral head that can be anatomically matched to each patient. This provides a strut to reduce the head and tuberosity fragments but still limits the amount of allograft bone needed to seat into the existing canal. The geometry of the allograft can also be customized to the fracture, with most 3- and 4-part fractures needing a trapezoidal strut that resembles the metaphyseal portion of a fracture-specific shoulder arthroplasty implant.

We have used this technique for comminuted 3- and 4-part fractures of the proximal humerus in 14 cases with at least 2-year follow-up and in several more cases that have not reached 2-year follow-up. All cases have gone on to radiographic union; none have had to be revised either with revision ORIF or to an arthroplasty. Formal measurements of final postoperative range of motion have not been tabulated in all cases, as some cases have been lost to follow-up after radiographic union was achieved. Medium- and long-term results are not yet available, but no short-term complications have been noted.

Disadvantages of this technique are that, while an individualized graft is created, proper shaping still takes time, and a moderate amount of the femoral head is not used. However, we have found that, if a graft is inadvertently undersized, there is still ample femoral head remaining to create another sized graft. Other disadvantages are the added cost and the (rare) risk of disease transmission, which come with use of any allograft, but the technique is used instead of another type of allograft, so these disadvantages are largely equivalent. At our hospital, differences in cost and availability between femoral head or fibular allografts are negligible.

This procedure, which is easily performed in a short amount of time, allows a stable base of bone graft to be used as an aid in the anatomical reduction of proximal humerus fractures, without the need for reaming and preparation of the medullary canal and without further increasing the difficulty associated with a future revision procedure.

1. Barrett JA, Baron JA, Karagas MR, Beach ML. Fracture risk in the U.S. Medicare population. J Clin Epidemiol. 1999;52(3):243-249.

2. Neer CS 2nd. Displaced proximal humeral fractures. I. Classification and evaluation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1970;52(6):1077-1089.

3. Liew AS, Johnson JA, Patterson SD, King GJ, Chess DG. Effect of screw placement on fixation in the humeral head. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2000;9(5):423-426.

4. Weinstein DM, Bratton DR, Ciccone WJ 2nd, Elias JJ. Locking plates improve torsional resistance in the stabilization of three-part proximal humeral fractures. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2006;15(2):239-243.

5. Agudelo J, Schurmann M, Stahel P, et al. Analysis of efficacy and failure in proximal humerus fractures treated with locking plates. J Orthop Trauma. 2007;21(10):676-681.

6. Egol KA, Sugi MT, Ong CC, Montero N, Davidovitch R, Zuckerman JD. Fracture site augmentation with calcium phosphate cement reduces screw penetration after open reduction-internal fixation of proximal humeral fractures. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(6):741-748.

7. Gradl G, Knobe M, Stoffel M, Prescher A, Dirrichs T, Pape HC. Biomechanical evaluation of locking plate fixation of proximal humeral fractures augmented with calcium phosphate cement. J Orthop Trauma. 2013;27(7):399-404.

8. Ong CC, Kwon YW, Walsh M, Davidovitch R, Zuckerman JD, Egol KA. Outcomes of open reduction and internal fixation of proximal humerus fractures managed with locking plates. Am J Orthop. 2012;41(9):407-412.

9. Namdari S, Voleti PB, Mehta S. Evaluation of the osteoporotic proximal humeral fracture and strategies for structural augmentation during surgical treatment. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(12):1787-1795.

10. Scheck M. Surgical treatment of nonunions of the surgical neck of the humerus. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1982;(167):255-259.

11. Hettrich CM, Neviaser A, Beamer BS, Paul O, Helfet DL, Lorich DG. Locked plating of the proximal humerus using an endosteal implant. J Orthop Trauma. 2012;26(4):212-215.

12. Neviaser AS, Hettrich CM, Beamer BS, Dines JS, Lorich DG. Endosteal strut augment reduces complications associated with proximal humeral locking plates. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469(12):3300-3306.

13. Gardner MJ, Boraiah S, Helfet DL, Lorich DG. Indirect medial reduction and strut support of proximal humerus fractures using an endosteal implant. J Orthop Trauma. 2008;22(3):195-200.

14. Matassi F, Angeloni R, Carulli C, et al. Locking plate and fibular allograft augmentation in unstable fractures of proximal humerus. Injury. 2012;43(11):1939-1942.

15. Little MT, Berkes MB, Schottel PC, et al. The impact of preoperative coronal plane deformity on proximal humerus fixation with endosteal augmentation. J Orthop Trauma. 2014;28(6):338-347.

16. Mathison C, Chaudhary R, Beaupre L, Reynolds M, Adeeb S, Bouliane M. Biomechanical analysis of proximal humeral fixation using locking plate fixation with an intramedullary fibular allograft. Clin Biomech. 2010;25(7):642-646.

17. Chow RM, Begum F, Beaupre LA, Carey JP, Adeeb S, Bouliane MJ. Proximal humeral fracture fixation: locking plate construct +/- intramedullary fibular allograft. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(7):894-901.

18. Jost B, Spross C, Grehn H, Gerber C. Locking plate fixation of fractures of the proximal humerus: analysis of complications, revision strategies and outcome. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22(4):542-549.

1. Barrett JA, Baron JA, Karagas MR, Beach ML. Fracture risk in the U.S. Medicare population. J Clin Epidemiol. 1999;52(3):243-249.

2. Neer CS 2nd. Displaced proximal humeral fractures. I. Classification and evaluation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1970;52(6):1077-1089.

3. Liew AS, Johnson JA, Patterson SD, King GJ, Chess DG. Effect of screw placement on fixation in the humeral head. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2000;9(5):423-426.

4. Weinstein DM, Bratton DR, Ciccone WJ 2nd, Elias JJ. Locking plates improve torsional resistance in the stabilization of three-part proximal humeral fractures. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2006;15(2):239-243.

5. Agudelo J, Schurmann M, Stahel P, et al. Analysis of efficacy and failure in proximal humerus fractures treated with locking plates. J Orthop Trauma. 2007;21(10):676-681.

6. Egol KA, Sugi MT, Ong CC, Montero N, Davidovitch R, Zuckerman JD. Fracture site augmentation with calcium phosphate cement reduces screw penetration after open reduction-internal fixation of proximal humeral fractures. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(6):741-748.

7. Gradl G, Knobe M, Stoffel M, Prescher A, Dirrichs T, Pape HC. Biomechanical evaluation of locking plate fixation of proximal humeral fractures augmented with calcium phosphate cement. J Orthop Trauma. 2013;27(7):399-404.

8. Ong CC, Kwon YW, Walsh M, Davidovitch R, Zuckerman JD, Egol KA. Outcomes of open reduction and internal fixation of proximal humerus fractures managed with locking plates. Am J Orthop. 2012;41(9):407-412.

9. Namdari S, Voleti PB, Mehta S. Evaluation of the osteoporotic proximal humeral fracture and strategies for structural augmentation during surgical treatment. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(12):1787-1795.

10. Scheck M. Surgical treatment of nonunions of the surgical neck of the humerus. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1982;(167):255-259.

11. Hettrich CM, Neviaser A, Beamer BS, Paul O, Helfet DL, Lorich DG. Locked plating of the proximal humerus using an endosteal implant. J Orthop Trauma. 2012;26(4):212-215.

12. Neviaser AS, Hettrich CM, Beamer BS, Dines JS, Lorich DG. Endosteal strut augment reduces complications associated with proximal humeral locking plates. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469(12):3300-3306.

13. Gardner MJ, Boraiah S, Helfet DL, Lorich DG. Indirect medial reduction and strut support of proximal humerus fractures using an endosteal implant. J Orthop Trauma. 2008;22(3):195-200.

14. Matassi F, Angeloni R, Carulli C, et al. Locking plate and fibular allograft augmentation in unstable fractures of proximal humerus. Injury. 2012;43(11):1939-1942.

15. Little MT, Berkes MB, Schottel PC, et al. The impact of preoperative coronal plane deformity on proximal humerus fixation with endosteal augmentation. J Orthop Trauma. 2014;28(6):338-347.

16. Mathison C, Chaudhary R, Beaupre L, Reynolds M, Adeeb S, Bouliane M. Biomechanical analysis of proximal humeral fixation using locking plate fixation with an intramedullary fibular allograft. Clin Biomech. 2010;25(7):642-646.

17. Chow RM, Begum F, Beaupre LA, Carey JP, Adeeb S, Bouliane MJ. Proximal humeral fracture fixation: locking plate construct +/- intramedullary fibular allograft. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(7):894-901.

18. Jost B, Spross C, Grehn H, Gerber C. Locking plate fixation of fractures of the proximal humerus: analysis of complications, revision strategies and outcome. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22(4):542-549.

Treatment of Proximal Humerus Fractures: Comparison of Shoulder and Trauma Surgeons

Proximal humerus fractures (PHFs), AO/OTA (Ar beitsgemeinschaft für Osteosynthesefragen/Orthopaedic Trauma Association) type 11,1 are common, representing 4% to 5% of all fractures in adults.2 However, there is no consensus as to optimal management of these injuries, with some reports supporting and others rejecting the various fixation methods,3 and there are no evidence-based practice guidelines informing treatment decisions.4 Not surprisingly, orthopedic surgeons do not agree on ideal treatment for PHFs5,6 and differ by region in their rates of surgical management.2 In addition, analyses of national databases have found variation in choice of surgical treatment for PHFs between surgeons and between hospitals of different patient volumes.4 Few studies have assessed surgeon agreement on treatment decisions. Findings from these limited investigations indicate there is little agreement on treatment choices, but training may have some impact.5-7 In 3 studies,5-7 shoulder and trauma fellowship–trained surgeons differed in their management of PHFs both in terms of rates of operative treatment5,7 and specific operative management choices.5,6 No study has assessed surgeon agreement on radiographic outcomes.

We conducted a study to compare expert shoulder and trauma surgeons’ treatment decision-making and agreement on final radiographic outcomes of surgically treated PHFs. We hypothesized there would be poor agreement on treatment decisions and better agreement on radiographic outcomes, with a difference between shoulder and trauma fellowship–trained surgeons.

Materials and Methods

After receiving institutional review board approval for this study, we collected data on 100 consecutive PHFs (AO/OTA type 111) surgically treated at 2 affiliated level I trauma centers between January 2004 and July 2008. None of the cases in the series was managed by any of the surgeons participating in this study.

We created a PowerPoint (Microsoft, Redmond, Washington) survey that included radiographs (preoperative, immediate postoperative, final postoperative) and, if available, a computed tomography image. This survey was sent to 4 orthopedic surgeons: Drs. Gardner, Gerber, Lorich, and Walch. Two of these authors are fellowship-trained in shoulder surgery, the other 2 in orthopedic traumatology with specialization in treating PHFs. All are internationally renowned in PHF management. Using the survey images and a 4-point Likert scale ranging from disagree strongly to agree strongly, the examiners rated their agreement with treatment decisions (arthroplasty vs fixation). They also rated (very poor to very good) immediate postoperative reduction or arthroplasty placement, immediate postoperative fixation methods for fractures treated with open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF), and final radiographic outcomes.

Interobserver agreement was calculated using the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC),8,9 with scores of <0.2 (poor), 0.21 to 0.4 (fair), 0.41 to 0.6 (moderate), 0.61 to 0.8 (good), and >0.8 (excellent) used to indicate agreement among observers. ICC scores were determined by treating the 4 examiners as independent entities. Subgroup analyses were also performed to determine ICC scores comparing the 2 shoulder surgeons, comparing the 2 trauma surgeons, and comparing the shoulder surgeons and trauma surgeons as 2 separate groups. ICC scores were used instead of κ coefficients to assess agreement because ICC scores treat ratings as continuous variables, allow for comparison of 2 or more raters, and allow for assessment of correlation among raters, whereas κ coefficients treat data as categorical variables and assume the ratings have no natural ordering. ICC scores were generated by SAS 9.1.3 software (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina).

Results

The 4 surgeons’ overall ICC scores for agreement with the rating of immediate reduction or arthroplasty placement and the rating of final radiographic outcome indicated moderate levels of agreement (Table 1). Regarding treatment decision-making and ratings of fixation, the surgeons demonstrated poor and fair levels of agreement, respectively.

The ICC scores comparing the shoulder and trauma surgeons revealed similar levels of agreement (Table 2): moderate levels of agreement for ratings of both immediate postoperative reduction or arthroplasty placement and final radiographic outcomes, but poor and fair levels of agreement regarding treatment decision-making and the rating of immediate postoperative fixation methods for fractures treated with ORIF, respectively.

Subgroup analysis revealed that the 2 shoulder surgeons had poor and fair levels of agreement for treatment decisions and rating of immediate postoperative fixation, respectively, though they moderately agreed on rating of immediate postoperative reduction or arthroplasty placement and rating of final radiographic outcome (Table 3). When the 2 trauma surgeons were compared with each other, ICC scores revealed higher levels of agreement overall (Table 4). In other words, the 2 trauma surgeons agreed with each other more than the 2 shoulder surgeons agreed with each other.

Discussion

This study had 3 major findings: (1) Surgeons do not agree on treatment decisions, including fixation methods, regarding PHFs; (2) regardless of their opinions on ideal treatment, they moderately agree on reductions and final radiographic outcomes; (3) expert trauma surgeons may agree more on treatment decisions than expert shoulder surgeons do. In other words, surgeons do not agree on the best treatment, but they radiographically recognize when a procedure has been performed technically well or poorly. These results support our hypothesis and the limited current literature.

An analysis of Medicare databases showed marked regional variation in rates of operative treatment of PHFs.2 Similarly, a Nationwide Inpatient Sample analysis revealed nationwide variation in operative management of PHFs.4 Both findings are consistent with our results of poor agreement about treatment decisions and ratings of postoperative fixation of PHFs. In 2010, Petit and colleagues6 reported that surgeons do not agree on PHF management. In 2011, Foroohar and colleagues10 similarly reported low interobserver agreement for treatment recommendations made by 4 upper extremity orthopedic specialists, 4 general orthopedic surgeons, 4 senior residents, and 4 junior residents, for a series of 16 PHFs—also consistent with our findings.

The lack of agreement about PHF treatment may reflect a difference in training, particularly in light of the recent expansion of shoulder and elbow fellowships.2 Three separate studies performed at 2 affiliated level I trauma centers demonstrated significant differences in treatment decision-making between shoulder and trauma fellowship–trained surgeons.5-7 Our results are consistent with the hypothesis that training affects treatment decision-making, as we found poor agreement between shoulder and trauma fellowship–trained surgeons regarding treatment decision for PHFs. Subanalyses revealed that expert trauma surgeons agreed with each other on treatment decisions more than expert shoulder surgeons agreed with each other, further suggesting that training may affect how surgeons manage PHFs. Differences in fellowship training even within the same specialty may account for the observed lesser levels of agreement between the shoulder surgeons, even among experts in the field.

The evidence for optimal treatment historically has been poor,4,6 with few high-quality prospective, randomized controlled studies on the topic up until the past few years. The most recent Cochrane Review on optimal PHF treatment concluded that there is insufficient evidence to make an evidence-based recommendation and that the long-term benefit of surgery is unclear.11 However, at least 5 controlled trials on the topic have been published within the past 5 years.12-16 The evidence is striking and generally supports nonoperative treatment for most PHFs, including some displaced fractures—contrary to general orthopedic practice in many parts of the United States,2 which hitherto had been based mainly on individual surgeon experience and the limited literature. Without strong evidence to support one treatment option over another, surgeons are left with no objective, scientific way of coming to agreement.

Related to the poor status quo of evidence for PHF treatments is new technology (eg, locking plates, reverse total shoulder arthroplasty) that has expanded surgical indications.2,17 Although such developments have the potential to improve surgical treatments, they may also exacerbate the disagreement between surgeons regarding optimal operative treatment of PHFs. This potential consequence of new technology may be reflected in our finding of disagreement among surgeons on immediate postoperative fixation methods. Precisely because they are new, such technological innovations have limited evidence supporting their use. This leaves surgeons with little to nothing to inform their decisions to use these devices, other than familiarity with and impressions of the new technology.

Our study had several limitations. First is the small sample size, of surgeons who are leaders in the field. Our sample therefore may not be generalizable to the general population of shoulder and trauma surgeons. Second, we did not calculate intraobserver variability. Third, inherent to studies of interobserver agreement is the uncertainty of their clinical relevance. In the clinical setting, a surgeon has much more information at hand (eg, patient history, physical examination findings, colleague consultations), thus raising the possibility of underestimations of interobserver agreements.18 Fourth, our comparison of surgeons’ ratings of outcomes was purely radiographic, which may or may not represent or be indicative of clinical outcomes (eg, pain relief, function, range of motion, patient satisfaction). The conclusions we may draw are accordingly limited, as we did not directly evaluate clinical outcome parameters.

Our study had several strengths as well. First, to our knowledge this is the first study to assess interobserver variability in surgeons’ ratings of radiographic outcomes. Its findings may provide further insight into the reasons for poor agreement among orthopedic surgeons on both classification and treatment of PHFs. Second, our surveying of internationally renowned expert surgeons from 4 different institutions may have helped reduce single-institution bias, and it presents the highest level of expertise in the treatment of PHFs.

Although the surgeons in our study moderately agreed on final radiographic outcomes of PHFs, such levels of agreement may still be clinically unacceptable.19 The overall disagreement on treatment decisions highlights the need for better evidence for optimal treatment of PHFs in order to improve consensus, particularly with anticipated increases in age and comorbidities in the population in coming years.4 Subgroup analysis suggested trauma fellowships may contribute to better treatment agreement, though this idea requires further study, perhaps by surveying shoulder and trauma fellowship directors and their curricula for variability in teaching treatment decision-making. The surgeons in our study agreed more on what they consider acceptable final radiographic outcomes, which is encouraging. However, treatment consensus is the primary goal. The recent publication of prospective, randomized studies is helping with this issue, but more studies are needed. It is encouraging that several are planned or under way.20-22

Conclusion

The surgeons surveyed in this study did not agree on ideal treatment for PHFs but moderately agreed on quality of radiographic outcomes. These differences may reflect a difference in training. We conducted this study to compare experienced shoulder and trauma fellowship–trained surgeons’ treatment decision-making and ratings of radiographic outcomes of PHFs when presented with the same group of patients managed at 2 level I trauma centers. We hypothesized there would be little agreement on treatment decisions, better agreement on final radiographic outcome, and a difference between decision-making and ratings of radiographic outcomes between expert shoulder and trauma surgeons. Our results showed that surgeons do not agree on the best treatment for PHFs but radiographically recognize when an operative treatment has been performed well or poorly. Regarding treatment decisions, our results also showed that expert trauma surgeons may agree more with each other than shoulder surgeons agree with each other. These results support our hypothesis and the limited current literature. The overall disagreement among the surgeons in our study and an aging population that grows sicker each year highlight the need for better evidence for the optimal treatment of PHFs in order to improve consensus.

1. Marsh JL, Slongo TF, Agel J, et al. Fracture and dislocation classification compendium – 2007: Orthopaedic Trauma Association classification, database and outcomes committee. J Orthop Trauma. 2007;21(10 suppl):S1-S133.

2. Bell JE, Leung BC, Spratt KF, et al. Trends and variation in incidence, surgical treatment, and repeat surgery of proximal humeral fractures in the elderly. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93(2):121-131.

3. McLaurin TM. Proximal humerus fractures in the elderly are we operating on too many? Bull Hosp Jt Dis. 2004;62(1-2):24-32.

4. Jain NB, Kuye I, Higgins LD, Warner JJP. Surgeon volume is associated with cost and variation in surgical treatment of proximal humeral fractures. Clin Orthop. 2012;471(2):655-664.

5. Boykin RE, Jawa A, O’Brien T, Higgins LD, Warner JJP. Variability in operative management of proximal humerus fractures. Shoulder Elbow. 2011;3(4):197-201.

6. Petit CJ, Millett PJ, Endres NK, Diller D, Harris MB, Warner JJP. Management of proximal humeral fractures: surgeons don’t agree. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2010;19(3):446-451.

7. Okike K, Lee OC, Makanji H, Harris MB, Vrahas MS. Factors associated with the decision for operative versus non-operative treatment of displaced proximal humerus fractures in the elderly. Injury. 2013;44(4):448-455.

8. Kodali P, Jones MH, Polster J, Miniaci A, Fening SD. Accuracy of measurement of Hill-Sachs lesions with computed tomography. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20(8):1328-1334.

9. Shrout PE, Fleiss JL. Intraclass correlations: uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychol Bull. 1979;86(2):420-428.

10. Foroohar A, Tosti R, Richmond JM, Gaughan JP, Ilyas AM. Classification and treatment of proximal humerus fractures: inter-observer reliability and agreement across imaging modalities and experience. J Orthop Surg Res. 2011;6:38.

11. Handoll HH, Ollivere BJ. Interventions for treating proximal humeral fractures in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(12):CD000434.

12. Boons HW, Goosen JH, van Grinsven S, van Susante JL, van Loon CJ. Hemiarthroplasty for humeral four-part fractures for patients 65 years and older: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Orthop. 2012;470(12):3483-3491.

13. Fjalestad T, Hole MØ, Hovden IAH, Blücher J, Strømsøe K. Surgical treatment with an angular stable plate for complex displaced proximal humeral fractures in elderly patients: a randomized controlled trial. J Orthop Trauma. 2012;26(2):98-106.

14. Fjalestad T, Hole MØ, Jørgensen JJ, Strømsøe K, Kristiansen IS. Health and cost consequences of surgical versus conservative treatment for a comminuted proximal humeral fracture in elderly patients. Injury. 2010;41(6):599-605.

15. Olerud P, Ahrengart L, Ponzer S, Saving J, Tidermark J. Internal fixation versus nonoperative treatment of displaced 3-part proximal humeral fractures in elderly patients: a randomized controlled trial. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20(5):747-755.

16. Olerud P, Ahrengart L, Ponzer S, Saving J, Tidermark J. Hemiarthroplasty versus nonoperative treatment of displaced 4-part proximal humeral fractures in elderly patients: a randomized controlled trial. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20(7):1025-1033.

17. Agudelo J, Schürmann M, Stahel P, et al. Analysis of efficacy and failure in proximal humerus fractures treated with locking plates. J Orthop Trauma. 2007;21(10):676-681.

18. Brorson S, Hróbjartsson A. Training improves agreement among doctors using the Neer system for proximal humeral fractures in a systematic review. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61(1):7-16.

19. Brorson S, Olsen BS, Frich LH, et al. Surgeons agree more on treatment recommendations than on classification of proximal humeral fractures. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2012;13:114.

20. Handoll H, Brealey S, Rangan A, et al. Protocol for the ProFHER (PROximal Fracture of the Humerus: Evaluation by Randomisation) trial: a pragmatic multi-centre randomised controlled trial of surgical versus non-surgical treatment for proximal fracture of the humerus in adults. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2009;10:140.

21. Den Hartog D, Van Lieshout EMM, Tuinebreijer WE, et al. Primary hemiarthroplasty versus conservative treatment for comminuted fractures of the proximal humerus in the elderly (ProCon): a multicenter randomized controlled trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2010;11:97.

22. Verbeek PA, van den Akker-Scheek I, Wendt KW, Diercks RL. Hemiarthroplasty versus angle-stable locking compression plate osteosynthesis in the treatment of three- and four-part fractures of the proximal humerus in the elderly: design of a randomized controlled trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2012;13:16.

Proximal humerus fractures (PHFs), AO/OTA (Ar beitsgemeinschaft für Osteosynthesefragen/Orthopaedic Trauma Association) type 11,1 are common, representing 4% to 5% of all fractures in adults.2 However, there is no consensus as to optimal management of these injuries, with some reports supporting and others rejecting the various fixation methods,3 and there are no evidence-based practice guidelines informing treatment decisions.4 Not surprisingly, orthopedic surgeons do not agree on ideal treatment for PHFs5,6 and differ by region in their rates of surgical management.2 In addition, analyses of national databases have found variation in choice of surgical treatment for PHFs between surgeons and between hospitals of different patient volumes.4 Few studies have assessed surgeon agreement on treatment decisions. Findings from these limited investigations indicate there is little agreement on treatment choices, but training may have some impact.5-7 In 3 studies,5-7 shoulder and trauma fellowship–trained surgeons differed in their management of PHFs both in terms of rates of operative treatment5,7 and specific operative management choices.5,6 No study has assessed surgeon agreement on radiographic outcomes.

We conducted a study to compare expert shoulder and trauma surgeons’ treatment decision-making and agreement on final radiographic outcomes of surgically treated PHFs. We hypothesized there would be poor agreement on treatment decisions and better agreement on radiographic outcomes, with a difference between shoulder and trauma fellowship–trained surgeons.

Materials and Methods

After receiving institutional review board approval for this study, we collected data on 100 consecutive PHFs (AO/OTA type 111) surgically treated at 2 affiliated level I trauma centers between January 2004 and July 2008. None of the cases in the series was managed by any of the surgeons participating in this study.

We created a PowerPoint (Microsoft, Redmond, Washington) survey that included radiographs (preoperative, immediate postoperative, final postoperative) and, if available, a computed tomography image. This survey was sent to 4 orthopedic surgeons: Drs. Gardner, Gerber, Lorich, and Walch. Two of these authors are fellowship-trained in shoulder surgery, the other 2 in orthopedic traumatology with specialization in treating PHFs. All are internationally renowned in PHF management. Using the survey images and a 4-point Likert scale ranging from disagree strongly to agree strongly, the examiners rated their agreement with treatment decisions (arthroplasty vs fixation). They also rated (very poor to very good) immediate postoperative reduction or arthroplasty placement, immediate postoperative fixation methods for fractures treated with open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF), and final radiographic outcomes.

Interobserver agreement was calculated using the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC),8,9 with scores of <0.2 (poor), 0.21 to 0.4 (fair), 0.41 to 0.6 (moderate), 0.61 to 0.8 (good), and >0.8 (excellent) used to indicate agreement among observers. ICC scores were determined by treating the 4 examiners as independent entities. Subgroup analyses were also performed to determine ICC scores comparing the 2 shoulder surgeons, comparing the 2 trauma surgeons, and comparing the shoulder surgeons and trauma surgeons as 2 separate groups. ICC scores were used instead of κ coefficients to assess agreement because ICC scores treat ratings as continuous variables, allow for comparison of 2 or more raters, and allow for assessment of correlation among raters, whereas κ coefficients treat data as categorical variables and assume the ratings have no natural ordering. ICC scores were generated by SAS 9.1.3 software (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina).

Results

The 4 surgeons’ overall ICC scores for agreement with the rating of immediate reduction or arthroplasty placement and the rating of final radiographic outcome indicated moderate levels of agreement (Table 1). Regarding treatment decision-making and ratings of fixation, the surgeons demonstrated poor and fair levels of agreement, respectively.

The ICC scores comparing the shoulder and trauma surgeons revealed similar levels of agreement (Table 2): moderate levels of agreement for ratings of both immediate postoperative reduction or arthroplasty placement and final radiographic outcomes, but poor and fair levels of agreement regarding treatment decision-making and the rating of immediate postoperative fixation methods for fractures treated with ORIF, respectively.

Subgroup analysis revealed that the 2 shoulder surgeons had poor and fair levels of agreement for treatment decisions and rating of immediate postoperative fixation, respectively, though they moderately agreed on rating of immediate postoperative reduction or arthroplasty placement and rating of final radiographic outcome (Table 3). When the 2 trauma surgeons were compared with each other, ICC scores revealed higher levels of agreement overall (Table 4). In other words, the 2 trauma surgeons agreed with each other more than the 2 shoulder surgeons agreed with each other.

Discussion

This study had 3 major findings: (1) Surgeons do not agree on treatment decisions, including fixation methods, regarding PHFs; (2) regardless of their opinions on ideal treatment, they moderately agree on reductions and final radiographic outcomes; (3) expert trauma surgeons may agree more on treatment decisions than expert shoulder surgeons do. In other words, surgeons do not agree on the best treatment, but they radiographically recognize when a procedure has been performed technically well or poorly. These results support our hypothesis and the limited current literature.

An analysis of Medicare databases showed marked regional variation in rates of operative treatment of PHFs.2 Similarly, a Nationwide Inpatient Sample analysis revealed nationwide variation in operative management of PHFs.4 Both findings are consistent with our results of poor agreement about treatment decisions and ratings of postoperative fixation of PHFs. In 2010, Petit and colleagues6 reported that surgeons do not agree on PHF management. In 2011, Foroohar and colleagues10 similarly reported low interobserver agreement for treatment recommendations made by 4 upper extremity orthopedic specialists, 4 general orthopedic surgeons, 4 senior residents, and 4 junior residents, for a series of 16 PHFs—also consistent with our findings.

The lack of agreement about PHF treatment may reflect a difference in training, particularly in light of the recent expansion of shoulder and elbow fellowships.2 Three separate studies performed at 2 affiliated level I trauma centers demonstrated significant differences in treatment decision-making between shoulder and trauma fellowship–trained surgeons.5-7 Our results are consistent with the hypothesis that training affects treatment decision-making, as we found poor agreement between shoulder and trauma fellowship–trained surgeons regarding treatment decision for PHFs. Subanalyses revealed that expert trauma surgeons agreed with each other on treatment decisions more than expert shoulder surgeons agreed with each other, further suggesting that training may affect how surgeons manage PHFs. Differences in fellowship training even within the same specialty may account for the observed lesser levels of agreement between the shoulder surgeons, even among experts in the field.

The evidence for optimal treatment historically has been poor,4,6 with few high-quality prospective, randomized controlled studies on the topic up until the past few years. The most recent Cochrane Review on optimal PHF treatment concluded that there is insufficient evidence to make an evidence-based recommendation and that the long-term benefit of surgery is unclear.11 However, at least 5 controlled trials on the topic have been published within the past 5 years.12-16 The evidence is striking and generally supports nonoperative treatment for most PHFs, including some displaced fractures—contrary to general orthopedic practice in many parts of the United States,2 which hitherto had been based mainly on individual surgeon experience and the limited literature. Without strong evidence to support one treatment option over another, surgeons are left with no objective, scientific way of coming to agreement.

Related to the poor status quo of evidence for PHF treatments is new technology (eg, locking plates, reverse total shoulder arthroplasty) that has expanded surgical indications.2,17 Although such developments have the potential to improve surgical treatments, they may also exacerbate the disagreement between surgeons regarding optimal operative treatment of PHFs. This potential consequence of new technology may be reflected in our finding of disagreement among surgeons on immediate postoperative fixation methods. Precisely because they are new, such technological innovations have limited evidence supporting their use. This leaves surgeons with little to nothing to inform their decisions to use these devices, other than familiarity with and impressions of the new technology.

Our study had several limitations. First is the small sample size, of surgeons who are leaders in the field. Our sample therefore may not be generalizable to the general population of shoulder and trauma surgeons. Second, we did not calculate intraobserver variability. Third, inherent to studies of interobserver agreement is the uncertainty of their clinical relevance. In the clinical setting, a surgeon has much more information at hand (eg, patient history, physical examination findings, colleague consultations), thus raising the possibility of underestimations of interobserver agreements.18 Fourth, our comparison of surgeons’ ratings of outcomes was purely radiographic, which may or may not represent or be indicative of clinical outcomes (eg, pain relief, function, range of motion, patient satisfaction). The conclusions we may draw are accordingly limited, as we did not directly evaluate clinical outcome parameters.

Our study had several strengths as well. First, to our knowledge this is the first study to assess interobserver variability in surgeons’ ratings of radiographic outcomes. Its findings may provide further insight into the reasons for poor agreement among orthopedic surgeons on both classification and treatment of PHFs. Second, our surveying of internationally renowned expert surgeons from 4 different institutions may have helped reduce single-institution bias, and it presents the highest level of expertise in the treatment of PHFs.