User login

An Intense Rash

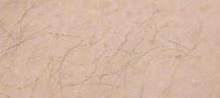

A32-year-old white male with Down syndrome was initially admitted with fever, cough, and productive sputum. He was started on appropriate antibiotics, but soon became hypoxic and developed respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation. The patient developed acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and eventually had a tracheostomy. On day 10, while in the intensive care unit, the patient developed multiple 1-2 mL clear vesicular eruptions with no surrounding erythema or edema. These were primarily distributed on the chest; the patient’s face was clear. TH

In dealing with this new eruption, the physician should have:

- Lowered the ambient room temperature and otherwise continued the current management.

- Performed a Tzanck smear, isolated the patient, and started acyclovir IV for presumed disseminated herpes zoster.

- Discontinued current antibiotics due to the drug reaction.

- Performed a skin biopsy for hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stain as well as immunofluorescence for suspected primary early bullous disease (i.e., bullous pemphigoid).

- Started amphotericin.

Discussion

The correct answer is A: The physician should have lowered the ambient room temperature and continued the current management.

This patient had developed miliaria crystallina, a transient disorder of occluded sweat glands that usually results from excessive exposure to heat and humidity. Miliaria, also known as sweat rash, defines a group of disorders exhibiting eccrine gland obstruction with leakage and retention of sweat at different levels in the skin. The clinical presentation of miliaria is related to the depth of this obstruction and occurs in three main forms: miliaria crystallina, miliaria rubra, and miliaria profunda.1

Of the three variants, eccrine obstruction in miliaria crystallina occurs most superficially, at either the distal duct or pore, and drives sweat vesiculation into the stratum corneum of the epidermis.1 It is characterized by diffuse eruptions of non-inflamed, translucent vesicles of one to two millimeters, typically forming in crops on the trunk of the body. The tiny blisters have been likened to beads of sweat and are extremely fragile, rupturing spontaneously or with light friction.

Clinically, miliaria crystallina is an asymptomatic and self-limited disorder. It often occurs during the summer months and in tropical climates after prolonged exposure to heat and humidity. It is thought that overhydration of corneocytes from excessive sweating predisposes the eccrine duct to obstruction. This may be compounded by any form of occlusion, like clothing or bedding, that traps moisture and impedes the evaporation of sweat.2 Other risk factors include persistent fevers, neonate age less than two weeks, secondary to eccrine duct immaturity, and drugs such as isotretinoin and bethanechol.3,4,5

In the case of this 32-year-old male with respiratory failure, the characteristic eruption of miliaria crystallina developed on day 10 of intensive care. After lowering the ambient temperature of the patient’s room and adding the benefit of a circulatory fan, the vesicles resolved within two to three days. As this example demonstrates, the treatment of miliaria crystallina is straightforward and consists of drying the skin and preventing sweating for several days by keeping the patient in a cool, air-conditioned environment. Eventually, the keratinous plug will be shed, and normal sweating will resume.

In the literature, there is only one published report documenting two distinct cases of miliaria crystallina in the intensive care setting. At the time of onset, these two patients had been in the ICU for slightly over two weeks, and both were receiving treatment with multiple neuroautonomic agents, including—but not limited to—clonidine, a beta blocker, and opiates for pain. The innervation of eccrine glands is under sympathetic control mostly through the postsynaptic release of acetylcholine but also via adrenergic stimulation of contractile myoepithelia. While temperature and humidity are carefully regulated in most intensive care facilities, significant sweating may result from eccrine stimulation by neuroautonomic medications with intrinsic sympathomimetic activity.6 Combined with prolonged immobility, this sweating may create the perfect environment for eccrine duct obstruction and the development of miliaria crystallina.

Incidence in the intensive care setting has not been studied, but miliaria crystallina probably occurs much more frequently than it is reported. The ability to recognize the characteristic eruptions may prevent the hospitalist who encounters it from ordering unnecessary consults or diagnostics, and knowledge of its risk factors will aid both in treatment and in prevention. TH

References

- Wenzel FG, Horn TD. Nonneoplastic disorders of the eccrine glands. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998 Jan;38(1):1–20.

- Sperling L. Chapter 3: Skin Diseases Associated with Excessive Heat, Humidity, and Sunlight. In: Textbook of Military Dermatology. Washington, D.C.: Office of The Surgeon General at TMM Publications; 1994:39-54. Available at: www.bordeninstitute.army.mil/derm/default_index.htm. Last accessed: September 8, 2006.

- Haas N, Henz BM, Weigel H. Congenital miliaria crystallina. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002 Nov;47(5 Suppl):S270–272.

- Gupta AK, Ellis CN, Madison KC, et al. Miliaria crystallina occurring in a patient treated with isotretinoin. Cutis. 1986 Oct;38(4):275–276.

- Rochmis PG, Koplon BS. Iatrogenic miliaria crystallina due to bethanechol. Arch Dermatol. 1967 May;95(9):499–500.

- Haas N, Martens F, Henz BM. Miliaria crystallina in an intensive care setting. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2004 Jan;29 (1):32-34.

A32-year-old white male with Down syndrome was initially admitted with fever, cough, and productive sputum. He was started on appropriate antibiotics, but soon became hypoxic and developed respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation. The patient developed acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and eventually had a tracheostomy. On day 10, while in the intensive care unit, the patient developed multiple 1-2 mL clear vesicular eruptions with no surrounding erythema or edema. These were primarily distributed on the chest; the patient’s face was clear. TH

In dealing with this new eruption, the physician should have:

- Lowered the ambient room temperature and otherwise continued the current management.

- Performed a Tzanck smear, isolated the patient, and started acyclovir IV for presumed disseminated herpes zoster.

- Discontinued current antibiotics due to the drug reaction.

- Performed a skin biopsy for hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stain as well as immunofluorescence for suspected primary early bullous disease (i.e., bullous pemphigoid).

- Started amphotericin.

Discussion

The correct answer is A: The physician should have lowered the ambient room temperature and continued the current management.

This patient had developed miliaria crystallina, a transient disorder of occluded sweat glands that usually results from excessive exposure to heat and humidity. Miliaria, also known as sweat rash, defines a group of disorders exhibiting eccrine gland obstruction with leakage and retention of sweat at different levels in the skin. The clinical presentation of miliaria is related to the depth of this obstruction and occurs in three main forms: miliaria crystallina, miliaria rubra, and miliaria profunda.1

Of the three variants, eccrine obstruction in miliaria crystallina occurs most superficially, at either the distal duct or pore, and drives sweat vesiculation into the stratum corneum of the epidermis.1 It is characterized by diffuse eruptions of non-inflamed, translucent vesicles of one to two millimeters, typically forming in crops on the trunk of the body. The tiny blisters have been likened to beads of sweat and are extremely fragile, rupturing spontaneously or with light friction.

Clinically, miliaria crystallina is an asymptomatic and self-limited disorder. It often occurs during the summer months and in tropical climates after prolonged exposure to heat and humidity. It is thought that overhydration of corneocytes from excessive sweating predisposes the eccrine duct to obstruction. This may be compounded by any form of occlusion, like clothing or bedding, that traps moisture and impedes the evaporation of sweat.2 Other risk factors include persistent fevers, neonate age less than two weeks, secondary to eccrine duct immaturity, and drugs such as isotretinoin and bethanechol.3,4,5

In the case of this 32-year-old male with respiratory failure, the characteristic eruption of miliaria crystallina developed on day 10 of intensive care. After lowering the ambient temperature of the patient’s room and adding the benefit of a circulatory fan, the vesicles resolved within two to three days. As this example demonstrates, the treatment of miliaria crystallina is straightforward and consists of drying the skin and preventing sweating for several days by keeping the patient in a cool, air-conditioned environment. Eventually, the keratinous plug will be shed, and normal sweating will resume.

In the literature, there is only one published report documenting two distinct cases of miliaria crystallina in the intensive care setting. At the time of onset, these two patients had been in the ICU for slightly over two weeks, and both were receiving treatment with multiple neuroautonomic agents, including—but not limited to—clonidine, a beta blocker, and opiates for pain. The innervation of eccrine glands is under sympathetic control mostly through the postsynaptic release of acetylcholine but also via adrenergic stimulation of contractile myoepithelia. While temperature and humidity are carefully regulated in most intensive care facilities, significant sweating may result from eccrine stimulation by neuroautonomic medications with intrinsic sympathomimetic activity.6 Combined with prolonged immobility, this sweating may create the perfect environment for eccrine duct obstruction and the development of miliaria crystallina.

Incidence in the intensive care setting has not been studied, but miliaria crystallina probably occurs much more frequently than it is reported. The ability to recognize the characteristic eruptions may prevent the hospitalist who encounters it from ordering unnecessary consults or diagnostics, and knowledge of its risk factors will aid both in treatment and in prevention. TH

References

- Wenzel FG, Horn TD. Nonneoplastic disorders of the eccrine glands. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998 Jan;38(1):1–20.

- Sperling L. Chapter 3: Skin Diseases Associated with Excessive Heat, Humidity, and Sunlight. In: Textbook of Military Dermatology. Washington, D.C.: Office of The Surgeon General at TMM Publications; 1994:39-54. Available at: www.bordeninstitute.army.mil/derm/default_index.htm. Last accessed: September 8, 2006.

- Haas N, Henz BM, Weigel H. Congenital miliaria crystallina. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002 Nov;47(5 Suppl):S270–272.

- Gupta AK, Ellis CN, Madison KC, et al. Miliaria crystallina occurring in a patient treated with isotretinoin. Cutis. 1986 Oct;38(4):275–276.

- Rochmis PG, Koplon BS. Iatrogenic miliaria crystallina due to bethanechol. Arch Dermatol. 1967 May;95(9):499–500.

- Haas N, Martens F, Henz BM. Miliaria crystallina in an intensive care setting. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2004 Jan;29 (1):32-34.

A32-year-old white male with Down syndrome was initially admitted with fever, cough, and productive sputum. He was started on appropriate antibiotics, but soon became hypoxic and developed respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation. The patient developed acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and eventually had a tracheostomy. On day 10, while in the intensive care unit, the patient developed multiple 1-2 mL clear vesicular eruptions with no surrounding erythema or edema. These were primarily distributed on the chest; the patient’s face was clear. TH

In dealing with this new eruption, the physician should have:

- Lowered the ambient room temperature and otherwise continued the current management.

- Performed a Tzanck smear, isolated the patient, and started acyclovir IV for presumed disseminated herpes zoster.

- Discontinued current antibiotics due to the drug reaction.

- Performed a skin biopsy for hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stain as well as immunofluorescence for suspected primary early bullous disease (i.e., bullous pemphigoid).

- Started amphotericin.

Discussion

The correct answer is A: The physician should have lowered the ambient room temperature and continued the current management.

This patient had developed miliaria crystallina, a transient disorder of occluded sweat glands that usually results from excessive exposure to heat and humidity. Miliaria, also known as sweat rash, defines a group of disorders exhibiting eccrine gland obstruction with leakage and retention of sweat at different levels in the skin. The clinical presentation of miliaria is related to the depth of this obstruction and occurs in three main forms: miliaria crystallina, miliaria rubra, and miliaria profunda.1

Of the three variants, eccrine obstruction in miliaria crystallina occurs most superficially, at either the distal duct or pore, and drives sweat vesiculation into the stratum corneum of the epidermis.1 It is characterized by diffuse eruptions of non-inflamed, translucent vesicles of one to two millimeters, typically forming in crops on the trunk of the body. The tiny blisters have been likened to beads of sweat and are extremely fragile, rupturing spontaneously or with light friction.

Clinically, miliaria crystallina is an asymptomatic and self-limited disorder. It often occurs during the summer months and in tropical climates after prolonged exposure to heat and humidity. It is thought that overhydration of corneocytes from excessive sweating predisposes the eccrine duct to obstruction. This may be compounded by any form of occlusion, like clothing or bedding, that traps moisture and impedes the evaporation of sweat.2 Other risk factors include persistent fevers, neonate age less than two weeks, secondary to eccrine duct immaturity, and drugs such as isotretinoin and bethanechol.3,4,5

In the case of this 32-year-old male with respiratory failure, the characteristic eruption of miliaria crystallina developed on day 10 of intensive care. After lowering the ambient temperature of the patient’s room and adding the benefit of a circulatory fan, the vesicles resolved within two to three days. As this example demonstrates, the treatment of miliaria crystallina is straightforward and consists of drying the skin and preventing sweating for several days by keeping the patient in a cool, air-conditioned environment. Eventually, the keratinous plug will be shed, and normal sweating will resume.

In the literature, there is only one published report documenting two distinct cases of miliaria crystallina in the intensive care setting. At the time of onset, these two patients had been in the ICU for slightly over two weeks, and both were receiving treatment with multiple neuroautonomic agents, including—but not limited to—clonidine, a beta blocker, and opiates for pain. The innervation of eccrine glands is under sympathetic control mostly through the postsynaptic release of acetylcholine but also via adrenergic stimulation of contractile myoepithelia. While temperature and humidity are carefully regulated in most intensive care facilities, significant sweating may result from eccrine stimulation by neuroautonomic medications with intrinsic sympathomimetic activity.6 Combined with prolonged immobility, this sweating may create the perfect environment for eccrine duct obstruction and the development of miliaria crystallina.

Incidence in the intensive care setting has not been studied, but miliaria crystallina probably occurs much more frequently than it is reported. The ability to recognize the characteristic eruptions may prevent the hospitalist who encounters it from ordering unnecessary consults or diagnostics, and knowledge of its risk factors will aid both in treatment and in prevention. TH

References

- Wenzel FG, Horn TD. Nonneoplastic disorders of the eccrine glands. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998 Jan;38(1):1–20.

- Sperling L. Chapter 3: Skin Diseases Associated with Excessive Heat, Humidity, and Sunlight. In: Textbook of Military Dermatology. Washington, D.C.: Office of The Surgeon General at TMM Publications; 1994:39-54. Available at: www.bordeninstitute.army.mil/derm/default_index.htm. Last accessed: September 8, 2006.

- Haas N, Henz BM, Weigel H. Congenital miliaria crystallina. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002 Nov;47(5 Suppl):S270–272.

- Gupta AK, Ellis CN, Madison KC, et al. Miliaria crystallina occurring in a patient treated with isotretinoin. Cutis. 1986 Oct;38(4):275–276.

- Rochmis PG, Koplon BS. Iatrogenic miliaria crystallina due to bethanechol. Arch Dermatol. 1967 May;95(9):499–500.

- Haas N, Martens F, Henz BM. Miliaria crystallina in an intensive care setting. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2004 Jan;29 (1):32-34.