User login

Diffusely Scattered Macules Following Radiation Therapy

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Mastocytosis

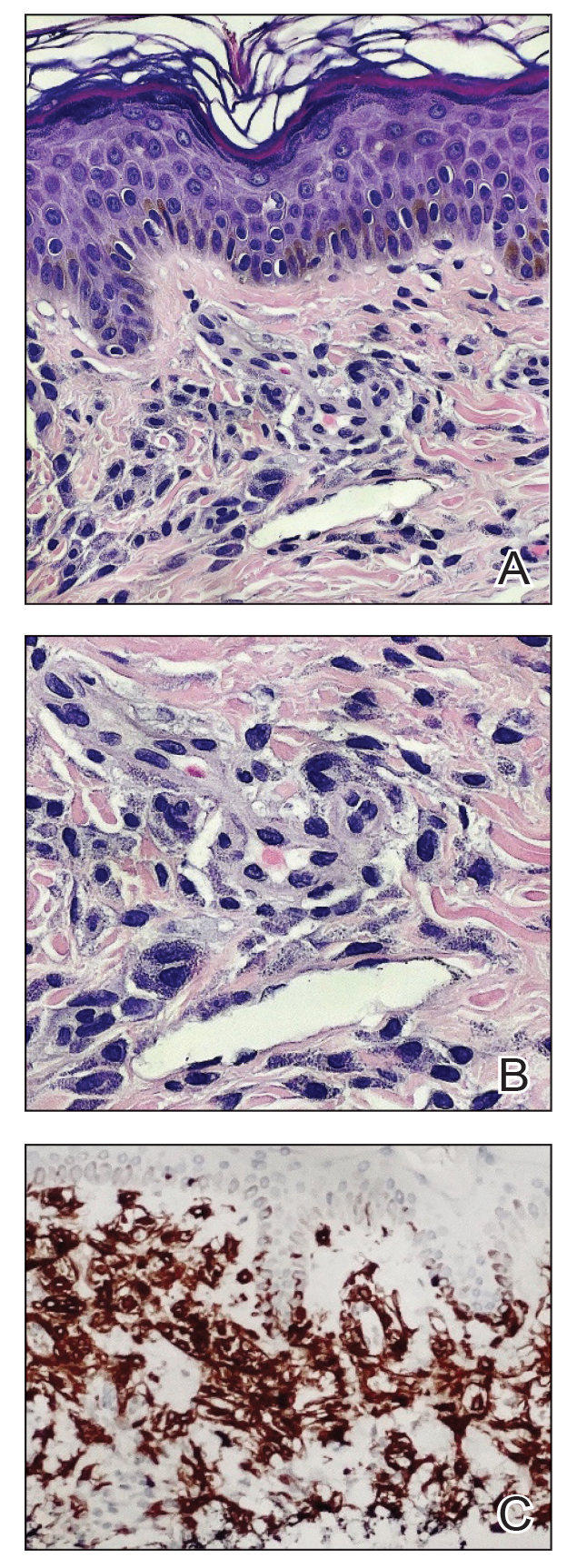

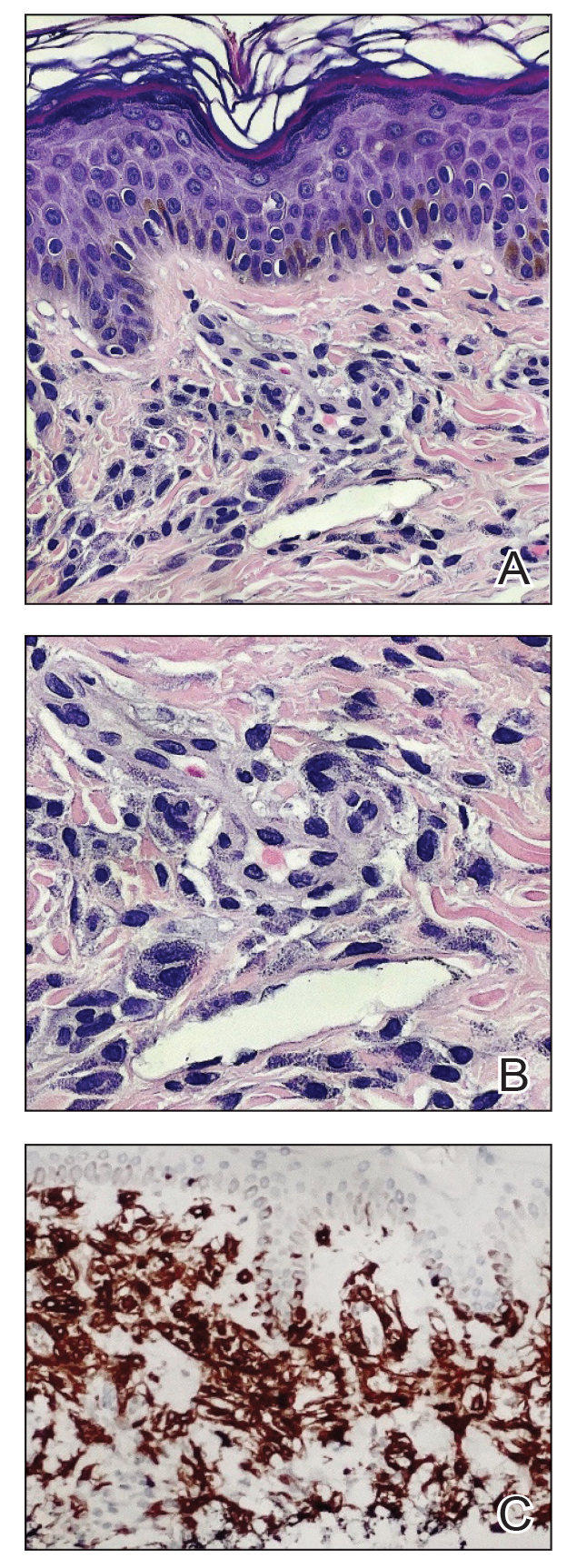

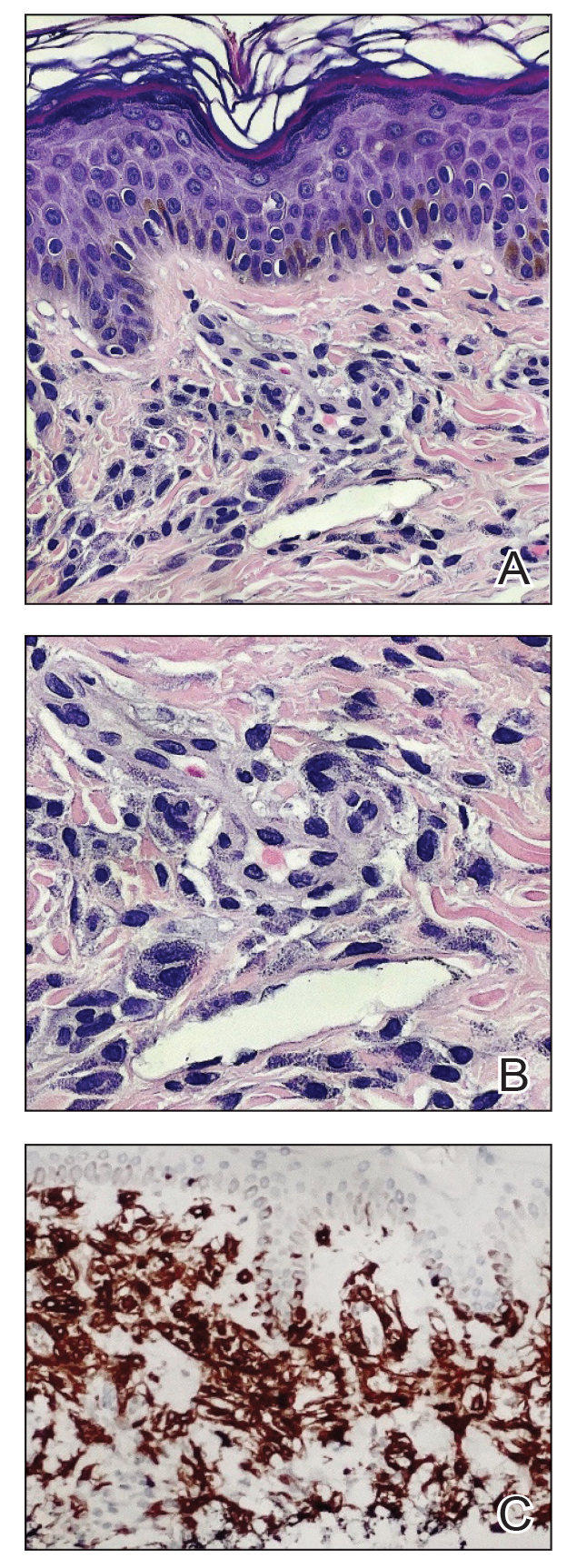

A shave skin biopsy from the right lateral breast and a punch skin biopsy from the right thigh showed similar histopathology. There were dermal predominantly perivascular aggregates of cells demonstrating basophilic granular cytoplasm and round to oval nuclei (Figure, A and B). These cells were highlighted by CD117 immunohistochemical stain (Figure, C), consistent with mastocytes. Additionally, occasional lymphocytes and rare eosinophils were noted. These histopathologic findings confirmed the diagnosis of cutaneous mastocytosis (CM). The patient’s complete blood cell count was within reference range, but serum tryptase was elevated at 15.7 μg/L (reference range, <11.0 μg/L), which prompted a bone marrow biopsy to rule out systemic mastocytosis (SM). The result showed normocellular bone marrow with no evidence of dysplasia or increased blasts, granuloma, lymphoproliferative disorder, or malignancy. Fluorescence in situ hybridization for PDGFRA (platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha) and KIT mutation was negative. Because CM developed predominantly on the right breast where the patient previously had received radiation therapy, we concluded that this reaction was triggered by exposure to ionizing radiation.

Mastocytosis can be divided into 2 groups: CM and SM.1 The histologic differential diagnosis of CM includes solitary mastocytoma, urticaria pigmentosa, telangiectasia macularis eruptiva perstans, and diffuse mastocytosis.2 Clinicopathologic correlation is of crucial importance to render the final diagnosis in these disorders. Immunohistochemically, mast cells express CD177, CD5, CD68, tryptase, and chymase. Unlike normal mast cells, neoplastic cells express CD2 and/or CD25; CD25 is commonly expressed in cutaneous involvement by SM.2

Macdonald and Feiwel3 reported the first case of CM following ionizing radiation. Cutaneous mastocytosis is most common in female patients and presents with redbrown macules originating at the site of radiation therapy. Prior literature suggests that radiation-associated CM has a predilection for White patients4; however, our patient was Hispanic. It also is important to note that the presentation of this rash may differ in individuals with skin of color. In one case it spread beyond the radiation site.2 Systemic mast call–mediated symptoms can occur in both CM and SM. The macules manifest as blanching with pressure.5 Typically these macules also are asymptomatic, though a positive Darier sign has been reported.6,7 The interval between radiotherapy and CM has ranged from 3 to 24 months.2

Patients with CM should have a serum tryptase evaluation along with a complete blood cell count, serum biochemistry, and liver function tests. Elevated serum tryptase has a high positive predictive value for SM and should prompt a bone marrow biopsy. Our patient’s bone marrow biopsy results failed to establish SM; however, her serum tryptase levels will be carefully monitored going forward. At the time of publication, the skin macules were still persistent but not worsening or symptomatic.

Treatment is focused on symptomatic relief of cutaneous symptoms, if present; avoiding triggers of mast cell degranulation; and implementing the use of oral antihistamines and leukotriene antagonists as needed. Because our patient was completely asymptomatic, we did not recommend any topical or oral treatment. However, we do counsel patients on avoiding triggers of mast cell degranulation including nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, morphine and codeine derivatives, alcohol, certain anesthetics, and anticholinergic medications.8

Additional diagnoses were ruled out for the following reasons: Although lichen planus pigmentosus presents with ill-defined, oval, gray-brown macules, histopathology shows a bandlike lymphocytic infiltrate at the dermoepidermal junction. Solar lentiginosis is characterized by grouped tan macules in a sun-exposed distribution. A fixed drug eruption is a delayed hypersensitivity reaction, usually to an ingested medication, characterized by violaceous or hyperpigmented patches, with histopathology showing interface dermatitis with a lymphoeosinophilic infiltrate. Eruptive seborrheic keratoses can result from sunburn or dermatitis but does not show mastocytes on histopathology.8

In conclusion, dermatologists should be reminded of the rare possibility of CM when evaluating an atypical eruption in a prior radiation field.

- Landy RE, Stross WC, May JM, et al. Idiopathic mast cell activation syndrome and radiation therapy: a case study, literature review, and discussion of mast cell disorders and radiotherapy [published online December 9, 2019]. Radiat Oncol. 2019;14:222. doi:10.1186 /s13014-019-1434-6

- Easwaralingam N, Wu Y, Cheung D, et al. Radiotherapy for breast cancer associated with a cutaneous presentation of systemic mastocytosis—a case report and literature review. J Surg Case Rep. 2018;2018:1-3. doi:10.1093/jscr/rjy317

- Macdonald A, Feiwel M. Cutaneous mastocytosis: an unusual radiation dermatitis. Proc R Soc Med. 1971;64:29-30.

- Kirshenbaum AS, Abuhay H, Bolan H, et al. Maculopapular cutaneous mastocytosis in a diverse population. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019;7:2845-2847. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2019.04.003

- Soilleux EJ, Brown VL, Bowling J. Cutaneous mastocytosis localized to a radiotherapy field. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2008;34:111-112. doi:10.1111 /j.1365-2230.2008.02931.x

- Comte C, Bessis D, Dereure O, et al. Urticaria pigmentosa localized on radiation field. Eur J Dermatol. 2003;13:408-409.

- Davidson SJ, Coates D. Cutaneous mastocytosis extending beyond a radiotherapy site: a form of radiodermatitis or a neoplastic phenomenon? Australas J Dermatol. 2012;54:E85-E87. doi:10.1111 /j.1440-0960.2012.00961.x

- Bolognia J, Schaffer JV, Duncan KO, et al, eds. Dermatology Essentials. 2nd ed. Elsevier; 2022.

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Mastocytosis

A shave skin biopsy from the right lateral breast and a punch skin biopsy from the right thigh showed similar histopathology. There were dermal predominantly perivascular aggregates of cells demonstrating basophilic granular cytoplasm and round to oval nuclei (Figure, A and B). These cells were highlighted by CD117 immunohistochemical stain (Figure, C), consistent with mastocytes. Additionally, occasional lymphocytes and rare eosinophils were noted. These histopathologic findings confirmed the diagnosis of cutaneous mastocytosis (CM). The patient’s complete blood cell count was within reference range, but serum tryptase was elevated at 15.7 μg/L (reference range, <11.0 μg/L), which prompted a bone marrow biopsy to rule out systemic mastocytosis (SM). The result showed normocellular bone marrow with no evidence of dysplasia or increased blasts, granuloma, lymphoproliferative disorder, or malignancy. Fluorescence in situ hybridization for PDGFRA (platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha) and KIT mutation was negative. Because CM developed predominantly on the right breast where the patient previously had received radiation therapy, we concluded that this reaction was triggered by exposure to ionizing radiation.

Mastocytosis can be divided into 2 groups: CM and SM.1 The histologic differential diagnosis of CM includes solitary mastocytoma, urticaria pigmentosa, telangiectasia macularis eruptiva perstans, and diffuse mastocytosis.2 Clinicopathologic correlation is of crucial importance to render the final diagnosis in these disorders. Immunohistochemically, mast cells express CD177, CD5, CD68, tryptase, and chymase. Unlike normal mast cells, neoplastic cells express CD2 and/or CD25; CD25 is commonly expressed in cutaneous involvement by SM.2

Macdonald and Feiwel3 reported the first case of CM following ionizing radiation. Cutaneous mastocytosis is most common in female patients and presents with redbrown macules originating at the site of radiation therapy. Prior literature suggests that radiation-associated CM has a predilection for White patients4; however, our patient was Hispanic. It also is important to note that the presentation of this rash may differ in individuals with skin of color. In one case it spread beyond the radiation site.2 Systemic mast call–mediated symptoms can occur in both CM and SM. The macules manifest as blanching with pressure.5 Typically these macules also are asymptomatic, though a positive Darier sign has been reported.6,7 The interval between radiotherapy and CM has ranged from 3 to 24 months.2

Patients with CM should have a serum tryptase evaluation along with a complete blood cell count, serum biochemistry, and liver function tests. Elevated serum tryptase has a high positive predictive value for SM and should prompt a bone marrow biopsy. Our patient’s bone marrow biopsy results failed to establish SM; however, her serum tryptase levels will be carefully monitored going forward. At the time of publication, the skin macules were still persistent but not worsening or symptomatic.

Treatment is focused on symptomatic relief of cutaneous symptoms, if present; avoiding triggers of mast cell degranulation; and implementing the use of oral antihistamines and leukotriene antagonists as needed. Because our patient was completely asymptomatic, we did not recommend any topical or oral treatment. However, we do counsel patients on avoiding triggers of mast cell degranulation including nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, morphine and codeine derivatives, alcohol, certain anesthetics, and anticholinergic medications.8

Additional diagnoses were ruled out for the following reasons: Although lichen planus pigmentosus presents with ill-defined, oval, gray-brown macules, histopathology shows a bandlike lymphocytic infiltrate at the dermoepidermal junction. Solar lentiginosis is characterized by grouped tan macules in a sun-exposed distribution. A fixed drug eruption is a delayed hypersensitivity reaction, usually to an ingested medication, characterized by violaceous or hyperpigmented patches, with histopathology showing interface dermatitis with a lymphoeosinophilic infiltrate. Eruptive seborrheic keratoses can result from sunburn or dermatitis but does not show mastocytes on histopathology.8

In conclusion, dermatologists should be reminded of the rare possibility of CM when evaluating an atypical eruption in a prior radiation field.

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Mastocytosis

A shave skin biopsy from the right lateral breast and a punch skin biopsy from the right thigh showed similar histopathology. There were dermal predominantly perivascular aggregates of cells demonstrating basophilic granular cytoplasm and round to oval nuclei (Figure, A and B). These cells were highlighted by CD117 immunohistochemical stain (Figure, C), consistent with mastocytes. Additionally, occasional lymphocytes and rare eosinophils were noted. These histopathologic findings confirmed the diagnosis of cutaneous mastocytosis (CM). The patient’s complete blood cell count was within reference range, but serum tryptase was elevated at 15.7 μg/L (reference range, <11.0 μg/L), which prompted a bone marrow biopsy to rule out systemic mastocytosis (SM). The result showed normocellular bone marrow with no evidence of dysplasia or increased blasts, granuloma, lymphoproliferative disorder, or malignancy. Fluorescence in situ hybridization for PDGFRA (platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha) and KIT mutation was negative. Because CM developed predominantly on the right breast where the patient previously had received radiation therapy, we concluded that this reaction was triggered by exposure to ionizing radiation.

Mastocytosis can be divided into 2 groups: CM and SM.1 The histologic differential diagnosis of CM includes solitary mastocytoma, urticaria pigmentosa, telangiectasia macularis eruptiva perstans, and diffuse mastocytosis.2 Clinicopathologic correlation is of crucial importance to render the final diagnosis in these disorders. Immunohistochemically, mast cells express CD177, CD5, CD68, tryptase, and chymase. Unlike normal mast cells, neoplastic cells express CD2 and/or CD25; CD25 is commonly expressed in cutaneous involvement by SM.2

Macdonald and Feiwel3 reported the first case of CM following ionizing radiation. Cutaneous mastocytosis is most common in female patients and presents with redbrown macules originating at the site of radiation therapy. Prior literature suggests that radiation-associated CM has a predilection for White patients4; however, our patient was Hispanic. It also is important to note that the presentation of this rash may differ in individuals with skin of color. In one case it spread beyond the radiation site.2 Systemic mast call–mediated symptoms can occur in both CM and SM. The macules manifest as blanching with pressure.5 Typically these macules also are asymptomatic, though a positive Darier sign has been reported.6,7 The interval between radiotherapy and CM has ranged from 3 to 24 months.2

Patients with CM should have a serum tryptase evaluation along with a complete blood cell count, serum biochemistry, and liver function tests. Elevated serum tryptase has a high positive predictive value for SM and should prompt a bone marrow biopsy. Our patient’s bone marrow biopsy results failed to establish SM; however, her serum tryptase levels will be carefully monitored going forward. At the time of publication, the skin macules were still persistent but not worsening or symptomatic.

Treatment is focused on symptomatic relief of cutaneous symptoms, if present; avoiding triggers of mast cell degranulation; and implementing the use of oral antihistamines and leukotriene antagonists as needed. Because our patient was completely asymptomatic, we did not recommend any topical or oral treatment. However, we do counsel patients on avoiding triggers of mast cell degranulation including nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, morphine and codeine derivatives, alcohol, certain anesthetics, and anticholinergic medications.8

Additional diagnoses were ruled out for the following reasons: Although lichen planus pigmentosus presents with ill-defined, oval, gray-brown macules, histopathology shows a bandlike lymphocytic infiltrate at the dermoepidermal junction. Solar lentiginosis is characterized by grouped tan macules in a sun-exposed distribution. A fixed drug eruption is a delayed hypersensitivity reaction, usually to an ingested medication, characterized by violaceous or hyperpigmented patches, with histopathology showing interface dermatitis with a lymphoeosinophilic infiltrate. Eruptive seborrheic keratoses can result from sunburn or dermatitis but does not show mastocytes on histopathology.8

In conclusion, dermatologists should be reminded of the rare possibility of CM when evaluating an atypical eruption in a prior radiation field.

- Landy RE, Stross WC, May JM, et al. Idiopathic mast cell activation syndrome and radiation therapy: a case study, literature review, and discussion of mast cell disorders and radiotherapy [published online December 9, 2019]. Radiat Oncol. 2019;14:222. doi:10.1186 /s13014-019-1434-6

- Easwaralingam N, Wu Y, Cheung D, et al. Radiotherapy for breast cancer associated with a cutaneous presentation of systemic mastocytosis—a case report and literature review. J Surg Case Rep. 2018;2018:1-3. doi:10.1093/jscr/rjy317

- Macdonald A, Feiwel M. Cutaneous mastocytosis: an unusual radiation dermatitis. Proc R Soc Med. 1971;64:29-30.

- Kirshenbaum AS, Abuhay H, Bolan H, et al. Maculopapular cutaneous mastocytosis in a diverse population. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019;7:2845-2847. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2019.04.003

- Soilleux EJ, Brown VL, Bowling J. Cutaneous mastocytosis localized to a radiotherapy field. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2008;34:111-112. doi:10.1111 /j.1365-2230.2008.02931.x

- Comte C, Bessis D, Dereure O, et al. Urticaria pigmentosa localized on radiation field. Eur J Dermatol. 2003;13:408-409.

- Davidson SJ, Coates D. Cutaneous mastocytosis extending beyond a radiotherapy site: a form of radiodermatitis or a neoplastic phenomenon? Australas J Dermatol. 2012;54:E85-E87. doi:10.1111 /j.1440-0960.2012.00961.x

- Bolognia J, Schaffer JV, Duncan KO, et al, eds. Dermatology Essentials. 2nd ed. Elsevier; 2022.

- Landy RE, Stross WC, May JM, et al. Idiopathic mast cell activation syndrome and radiation therapy: a case study, literature review, and discussion of mast cell disorders and radiotherapy [published online December 9, 2019]. Radiat Oncol. 2019;14:222. doi:10.1186 /s13014-019-1434-6

- Easwaralingam N, Wu Y, Cheung D, et al. Radiotherapy for breast cancer associated with a cutaneous presentation of systemic mastocytosis—a case report and literature review. J Surg Case Rep. 2018;2018:1-3. doi:10.1093/jscr/rjy317

- Macdonald A, Feiwel M. Cutaneous mastocytosis: an unusual radiation dermatitis. Proc R Soc Med. 1971;64:29-30.

- Kirshenbaum AS, Abuhay H, Bolan H, et al. Maculopapular cutaneous mastocytosis in a diverse population. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019;7:2845-2847. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2019.04.003

- Soilleux EJ, Brown VL, Bowling J. Cutaneous mastocytosis localized to a radiotherapy field. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2008;34:111-112. doi:10.1111 /j.1365-2230.2008.02931.x

- Comte C, Bessis D, Dereure O, et al. Urticaria pigmentosa localized on radiation field. Eur J Dermatol. 2003;13:408-409.

- Davidson SJ, Coates D. Cutaneous mastocytosis extending beyond a radiotherapy site: a form of radiodermatitis or a neoplastic phenomenon? Australas J Dermatol. 2012;54:E85-E87. doi:10.1111 /j.1440-0960.2012.00961.x

- Bolognia J, Schaffer JV, Duncan KO, et al, eds. Dermatology Essentials. 2nd ed. Elsevier; 2022.

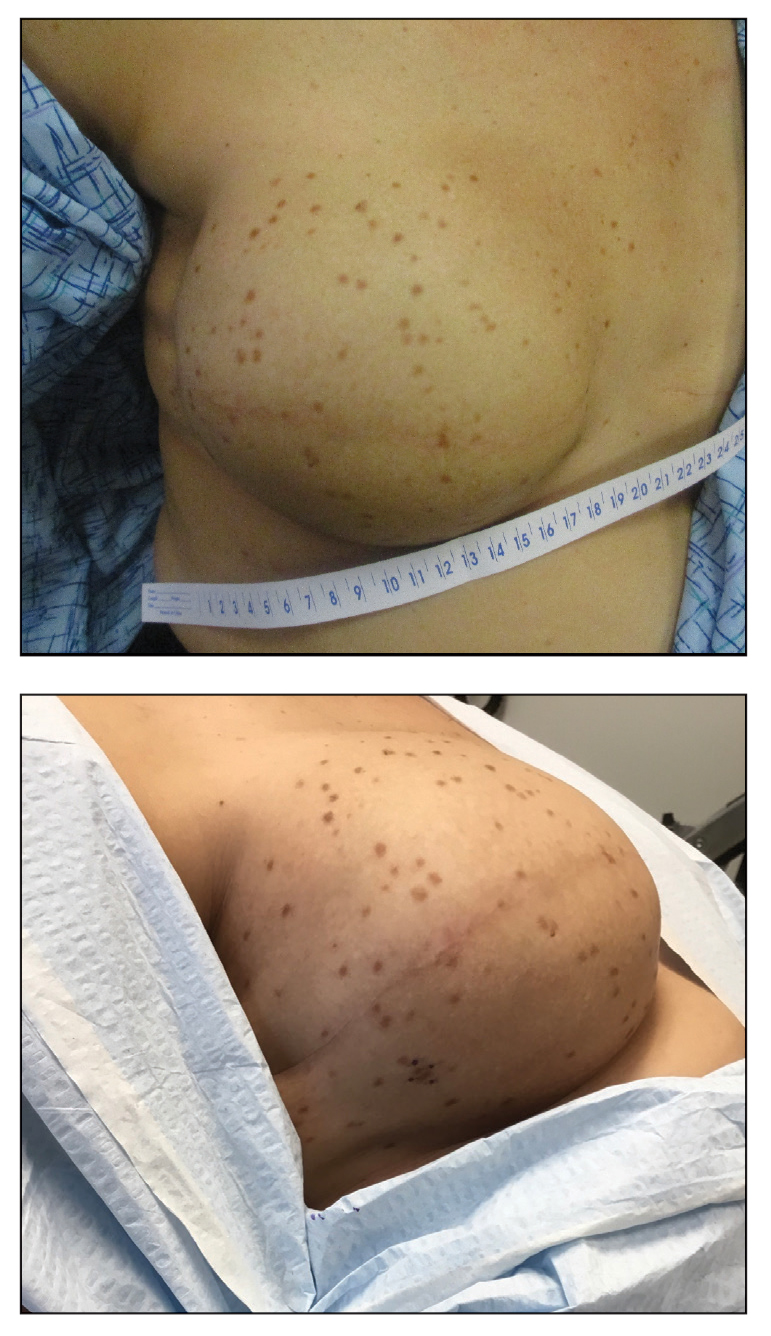

A 41-year-old woman was referred to dermatology by her radiation oncologist for evaluation of a rash on the right breast at the site of prior radiation therapy of 4 to 6 weeks’ duration. Approximately 2 years prior, the patient was diagnosed with triple-negative invasive ductal carcinoma of the right breast. She was treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy, bilateral simple mastectomies, and 28 doses of adjuvant radiation therapy. Thirteen months after completing radiation therapy, the patient noted the onset of asymptomatic freckles on the right breast that had appeared over weeks and seemed to be multiplying. Physical examination at the time of dermatology consultation revealed multiple diffusely scattered, brownishred, 3- to 5-mm macules concentrated on the right breast but also involving the right supraclavicular and right axillary areas, abdomen, and thighs.

Erythematous Seropurulent Ulcerations

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Leishmaniasis

On examination, the patient had multiple punched-out ulcers with indurated borders and surrounding erythema arranged in a sporotrichoid pattern from the left forearm to the left lateral chest (Figure 1).

Bacterial culture of a tissue specimen was negative, and tissue fungal culture failed to grow any organisms. Serological studies included a complete blood cell count with differential, a chemistry panel, and liver function tests, which were all unremarkable. Coccidioidomycosis and human immunodefi-ciency virus antibodies were negative. A 4-mm punch biopsy was obtained and sent to the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology for review. Histopathologic examination revealed marked inflammation with ill-formed noncaseating granulomas and focal ulceration, necrosis in the deep dermis, and both intra-cellular and extracellular amastigotes within areas of necrosis (Figures 2 and 3).

The rise in the number of cases of cutaneous leishmaniasis in the United States, particularly in the veteran population, can be attributed to the recent conflicts in the Middle East and Afghanistan. Infection with Leishmania species can result in a variety of clinical presentations, ranging from localized, self-limited cutaneous lesions to a life-threatening infection with visceral involvement.1 Additionally, the host immune response is variable. This variation in clinical presentation and disease progression explains why there is no single best treatment identified for leishmaniasis to date.

The clinical pattern of spread along the lymphatics in this patient is unique. The differential diagnosis of lesions with sporotrichoid spread includes Mycobacterium marinum and other atypical mycobacterial infections, Sporothrix schenckii, nocardiosis, leishmaniasis, coccidioidomycosis, tularemia, cat scratch disease, anthrax, chromoblastomycosis, pyogenic bacteria, and other fungal or bacterial infections. With such a broad differential diagnosis, histologic confirmation is paramount.

The most widely used pharmacotherapy for leishmaniasis is with pentavalent antimony compounds, which have been studied in randomized controlled trials for leishmaniasis more than any other drug.2 These antimony compounds are associated with a large spectrum of clinical adverse events, and there is increasing evidence for emerging parasite resistance to the antimonies.3-5 Historically, amphotericin B was considered a second-line treatment of leishmaniasis due to its systemic toxicity.6 However, this treatment has come back into favor due to its newer, more tolerable, lipid-associated formulation.

Our patient was treated with intravenous liposomal amphotericin B at a dosage of 3 mg/kg daily for days 1 to 5, then again on days 14 and 21. He tolerated the therapeutic regimen without difficulty or adverse effects. The ulcers eventually became smaller and ceased to weep, fully healing over a course of several months.

1. Martin-Ezquerra G, Fisa R, Riera C, et al. Role of Leishmania spp. infestation in nondiagnostic cutaneous granulomatous lesions: report of a series of patients from a Western Mediterranean area. Br J Dermatol. 2009;161:320-325.

2. Khatami A, Firooz A, Gorouhi F, et al. Treatment of acute old world cutaneous leishmaniasis: a systemic review of the randomized controlled trials. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:335.e1-335.e29.

3. Rojas R, Valderrama L, Valderrama M, et al. Resistance to antimony and treatment failure in human Leishmania (Viannia) infection. J Infect Dis. 2006;193:1375-1383.

4. Hadighi R, Mohebali M, Boucher P, et al. Unresponsiveness to glucantime treatment in Iranian cutaneous leishmaniasis due to drug-resistant Leishmania tropica parasites. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e162.

5. Croft SL, Sundar S, Fairlamb AH. Drug resistance in leishmaniasis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2006;19:111-126.

6. Croft S, Seifert K, Yardley V. Current scenario of drug development for leishmaniasis. Indian J Med Res. 2006;123:399-410.

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Leishmaniasis

On examination, the patient had multiple punched-out ulcers with indurated borders and surrounding erythema arranged in a sporotrichoid pattern from the left forearm to the left lateral chest (Figure 1).

Bacterial culture of a tissue specimen was negative, and tissue fungal culture failed to grow any organisms. Serological studies included a complete blood cell count with differential, a chemistry panel, and liver function tests, which were all unremarkable. Coccidioidomycosis and human immunodefi-ciency virus antibodies were negative. A 4-mm punch biopsy was obtained and sent to the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology for review. Histopathologic examination revealed marked inflammation with ill-formed noncaseating granulomas and focal ulceration, necrosis in the deep dermis, and both intra-cellular and extracellular amastigotes within areas of necrosis (Figures 2 and 3).

The rise in the number of cases of cutaneous leishmaniasis in the United States, particularly in the veteran population, can be attributed to the recent conflicts in the Middle East and Afghanistan. Infection with Leishmania species can result in a variety of clinical presentations, ranging from localized, self-limited cutaneous lesions to a life-threatening infection with visceral involvement.1 Additionally, the host immune response is variable. This variation in clinical presentation and disease progression explains why there is no single best treatment identified for leishmaniasis to date.

The clinical pattern of spread along the lymphatics in this patient is unique. The differential diagnosis of lesions with sporotrichoid spread includes Mycobacterium marinum and other atypical mycobacterial infections, Sporothrix schenckii, nocardiosis, leishmaniasis, coccidioidomycosis, tularemia, cat scratch disease, anthrax, chromoblastomycosis, pyogenic bacteria, and other fungal or bacterial infections. With such a broad differential diagnosis, histologic confirmation is paramount.

The most widely used pharmacotherapy for leishmaniasis is with pentavalent antimony compounds, which have been studied in randomized controlled trials for leishmaniasis more than any other drug.2 These antimony compounds are associated with a large spectrum of clinical adverse events, and there is increasing evidence for emerging parasite resistance to the antimonies.3-5 Historically, amphotericin B was considered a second-line treatment of leishmaniasis due to its systemic toxicity.6 However, this treatment has come back into favor due to its newer, more tolerable, lipid-associated formulation.

Our patient was treated with intravenous liposomal amphotericin B at a dosage of 3 mg/kg daily for days 1 to 5, then again on days 14 and 21. He tolerated the therapeutic regimen without difficulty or adverse effects. The ulcers eventually became smaller and ceased to weep, fully healing over a course of several months.

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Leishmaniasis

On examination, the patient had multiple punched-out ulcers with indurated borders and surrounding erythema arranged in a sporotrichoid pattern from the left forearm to the left lateral chest (Figure 1).

Bacterial culture of a tissue specimen was negative, and tissue fungal culture failed to grow any organisms. Serological studies included a complete blood cell count with differential, a chemistry panel, and liver function tests, which were all unremarkable. Coccidioidomycosis and human immunodefi-ciency virus antibodies were negative. A 4-mm punch biopsy was obtained and sent to the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology for review. Histopathologic examination revealed marked inflammation with ill-formed noncaseating granulomas and focal ulceration, necrosis in the deep dermis, and both intra-cellular and extracellular amastigotes within areas of necrosis (Figures 2 and 3).

The rise in the number of cases of cutaneous leishmaniasis in the United States, particularly in the veteran population, can be attributed to the recent conflicts in the Middle East and Afghanistan. Infection with Leishmania species can result in a variety of clinical presentations, ranging from localized, self-limited cutaneous lesions to a life-threatening infection with visceral involvement.1 Additionally, the host immune response is variable. This variation in clinical presentation and disease progression explains why there is no single best treatment identified for leishmaniasis to date.

The clinical pattern of spread along the lymphatics in this patient is unique. The differential diagnosis of lesions with sporotrichoid spread includes Mycobacterium marinum and other atypical mycobacterial infections, Sporothrix schenckii, nocardiosis, leishmaniasis, coccidioidomycosis, tularemia, cat scratch disease, anthrax, chromoblastomycosis, pyogenic bacteria, and other fungal or bacterial infections. With such a broad differential diagnosis, histologic confirmation is paramount.

The most widely used pharmacotherapy for leishmaniasis is with pentavalent antimony compounds, which have been studied in randomized controlled trials for leishmaniasis more than any other drug.2 These antimony compounds are associated with a large spectrum of clinical adverse events, and there is increasing evidence for emerging parasite resistance to the antimonies.3-5 Historically, amphotericin B was considered a second-line treatment of leishmaniasis due to its systemic toxicity.6 However, this treatment has come back into favor due to its newer, more tolerable, lipid-associated formulation.

Our patient was treated with intravenous liposomal amphotericin B at a dosage of 3 mg/kg daily for days 1 to 5, then again on days 14 and 21. He tolerated the therapeutic regimen without difficulty or adverse effects. The ulcers eventually became smaller and ceased to weep, fully healing over a course of several months.

1. Martin-Ezquerra G, Fisa R, Riera C, et al. Role of Leishmania spp. infestation in nondiagnostic cutaneous granulomatous lesions: report of a series of patients from a Western Mediterranean area. Br J Dermatol. 2009;161:320-325.

2. Khatami A, Firooz A, Gorouhi F, et al. Treatment of acute old world cutaneous leishmaniasis: a systemic review of the randomized controlled trials. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:335.e1-335.e29.

3. Rojas R, Valderrama L, Valderrama M, et al. Resistance to antimony and treatment failure in human Leishmania (Viannia) infection. J Infect Dis. 2006;193:1375-1383.

4. Hadighi R, Mohebali M, Boucher P, et al. Unresponsiveness to glucantime treatment in Iranian cutaneous leishmaniasis due to drug-resistant Leishmania tropica parasites. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e162.

5. Croft SL, Sundar S, Fairlamb AH. Drug resistance in leishmaniasis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2006;19:111-126.

6. Croft S, Seifert K, Yardley V. Current scenario of drug development for leishmaniasis. Indian J Med Res. 2006;123:399-410.

1. Martin-Ezquerra G, Fisa R, Riera C, et al. Role of Leishmania spp. infestation in nondiagnostic cutaneous granulomatous lesions: report of a series of patients from a Western Mediterranean area. Br J Dermatol. 2009;161:320-325.

2. Khatami A, Firooz A, Gorouhi F, et al. Treatment of acute old world cutaneous leishmaniasis: a systemic review of the randomized controlled trials. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:335.e1-335.e29.

3. Rojas R, Valderrama L, Valderrama M, et al. Resistance to antimony and treatment failure in human Leishmania (Viannia) infection. J Infect Dis. 2006;193:1375-1383.

4. Hadighi R, Mohebali M, Boucher P, et al. Unresponsiveness to glucantime treatment in Iranian cutaneous leishmaniasis due to drug-resistant Leishmania tropica parasites. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e162.

5. Croft SL, Sundar S, Fairlamb AH. Drug resistance in leishmaniasis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2006;19:111-126.

6. Croft S, Seifert K, Yardley V. Current scenario of drug development for leishmaniasis. Indian J Med Res. 2006;123:399-410.

A 34-year-old male veteran who was otherwise healthy presented with multiple ulcerated skin lesions on the left arm and forearm as well as the chest. After returning to the United States from being stationed in Qatar and Saudi Arabia, he noticed multiple “bug bites” on the left arm that eventually progressed to larger crusted ulcerations. He denied fever, chills, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, tenderness, or any other symptoms. He had been given doxycycline for a possible bacterial infection, but the lesions did not improve.