User login

School avoidance: How to help when a child refuses to go

THE CASE

Juana*, a 10-year-old who identifies as a cisgender, Hispanic female, was referred to our integrated behavioral health program by her primary care physician. Her mother was concerned because Juana had been refusing to attend school due to complaints of gastrointestinal upset. This concern began when Juana was in first grade but had increased in severity over the past few months.

Upon further questioning, the patient reported that she initially did not want to attend school due to academic difficulties and bullying. However, since COVID-19, her fears of attending school had significantly worsened. Juana’s mother’s primary language was Spanish and she had limited English proficiency; she reported difficulty communicating with school personnel about Juana’s poor attendance.

Juana had recently had a complete medical work-up for her gastrointestinal concerns, with negative results. Since the negative work-up, Juana’s mother had told her daughter that she would be punished if she didn’t go to school.

●

* The patient’s name has been changed to protect her identity.

School avoidance, also referred to as school refusal, is a symptom of an emotional condition that manifests as a child refusing to go to school or having difficulty going to school or remaining in the classroom for the entire day. School avoidance is not a clinical diagnosis but often is related to an underlying disorder.1

School avoidance is common, affecting 5% to 28% of youth sometime in their school career.2 Available data are not specific to school avoidance but focus on chronic absenteeism (missing ≥ 15 days per school year). Rates of chronic absenteeism are high in elementary and middle school (about 14% each) and tend to increase in high school (about 21%).3 Students with disabilities are 1.5 times more likely to be chronically absent than students without disabilities.3 Compared to White students, American Indian and Pacific Islander students are > 50% more likely, Black students 40% more likely, and Hispanic students 17% more likely to miss ≥ 3 weeks of school.3 Rates of chronic absenteeism are similar (about 16%) for males and females.3

Absenteeism can have immediate and long-term negative effects.4 School attendance issues are correlated to negative life outcomes, such as delinquency, teen pregnancy, substance use, and poor academic achievement.5 According to the US Department of Education, individuals who chronically miss school are less likely to achieve educational milestones (particularly in younger years) and may be more likely to drop out of school.3

What school avoidance is (and what it isn’t)

It is important to distinguish school avoidance from truancy. Truancy often is associated with antisocial behavior such as lying and stealing, while school avoidance occurs in the absence of significant antisocial disorders.6 With truancy, the absence usually is hidden from the parent. In contrast, with school avoidance, the parents usually know where their child is; the child often spends the day secluded in their bedroom. Students who engage in truancy do not demonstrate excessive anxiety about attending school but may have decreased interest in schoolwork and academic performance.6 With school avoidance, the child exhibits severe emotional distress about attending school but is willing to complete schoolwork at home.

Why children may avoid school

School avoidance is a biopsychosocial condition with a multitude of underlying causes.4 It is associated most commonly with anxiety disorders and neurodevelopmental disorders, including but not limited to learning disabilities and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.1 Depressive disorders also have been associated with school avoidance.7 Social concerns related to changes with school personnel or classes, academic challenges, bullying, health emergencies, and family stressors also can result in symptoms of school avoidance.1

Continue to: A child seeking to avoid...

A child seeking to avoid school may be motivated by potential negative and/or positive effects of doing so. Kearney and Silverman8 identified 4 primary functions of school refusal behaviors:

- avoiding stimuli at school that lend to negative affect (depression, anxiety)

- escaping the social interactions and/or situations for evaluation that occur at school

- gaining more attention from caregivers, and

- obtaining tangible rewards or benefits outside the school environment.

How school avoidance manifests

School avoidance has attributes of internalizing (depression, anxiety, somatic complaints) and externalizing (aggression, tantrums, running away, clinginess) behaviors. It can cause distress for the student, parents and caregivers, and school personnel.

The avoidance may manifest with behaviors such as crying, hiding, emotional outbursts, and refusing to move prior to the start of the school day. Additionally, the child may beg their parents not to make them go to school or, when at school, they may leave the classroom to go to a safe place such as the nurse’s or counselor’s office.

The avoidance may occur abruptly, such as after a break in the school schedule or a change of school. Or it may be the final result of the student’s gradual inability to cope with the underlying issue.

How to assess for school avoidance

Due to the multifactorial nature of this presenting concern, a comprehensive evaluation is recommended when school avoidance is reported.4 Often the child will present with physical symptoms, such as abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, headaches, shortness of breath, dizziness, chest pain, and palpitations. A thorough medical examination should be performed to rule out a physiological cause. The medical visit should include clinical interviews with the patient and family members or guardians.

Continue to: To identify school avoidance...

To identify school avoidance in pediatric and adolescent populations, medical history and physical examination—along with social history to better understand familial, social, and academic concerns—should be a regular part of the medical encounter. The School Refusal Assessment Scale-Revised (SRAS-R) for both parents and their children was developed to assess for school avoidance and can be utilized within the primary care setting. Additional psychiatric history for both the family and patient may be beneficial, due to associations between parental mental health concerns and school avoidance in their children.9,10

Assessment for an underlying mental health condition, such as an anxiety or depressive disorder, should be completed when a patient presents with school avoidance.4 More than one-third of children with behavioral problems, such as school avoidance, have been diagnosed with anxiety.11 The 2020 National Survey of Children’s Health found that 7.8% of children and adolescents ages 3 to 17 years had a current anxiety disorder, leading the US Preventive Services Task Force to recommend screening for anxiety in children and adolescents ages 8 to 18 years.12,13 Furthermore, if academic achievement is of concern, then consideration of further assessment for neurodevelopmental disorders is warranted.1

Treatment is multimodal and multidisciplinary

Treatment for school avoidance is often multimodal and may involve interdisciplinary, team-based care including the medical provider, school system (eg, Child Study Team), family, and mental health care provider.1,4

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is the most-studied intervention for school avoidance, with behavioral, exposure-based interventions often central to therapeutic gains in treatment.1,14,15 The goals of treatment are to increase school attendance while decreasing emotional distress through various strategies, including exposure-based interventions, contingency management with parents and school staff, relaxation training, and/or social skills training.14,16 Collaborative involvement between the medical provider and the school system is key to successful treatment.

Medication may be considered alone or in combination with CBT when comorbid mental health conditions have been identified. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs)—including fluoxetine, sertraline, and escitalopram—are considered first-line treatment for anxiety in children and adolescents.17 Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), such as duloxetine and venlafaxine, also have been shown to be effective. Duloxetine is the only medication approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for treatment of generalized anxiety disorder in children ages 7 years and older.17

Continue to: SSRIs and SNRIs have a boxed warning...

SSRIs and SNRIs have a boxed warning from the FDA for increased suicidal thoughts and behaviors in children and adolescents. Although this risk is rare, it should be discussed with the patient and parent/guardian in order to obtain informed consent prior to treatment initiation.

Medication should be started at the lowest possible dose and increased gradually. Patients should remain on the medication for 6 to 12 months after symptom resolution and should be tapered during a nonstressful time, such as the summer break.

THE CASE

Based on the concerns of continued school refusal after negative gastrointestinal work-up, Juana’s physician screened her for anxiety and conducted a clinical interview to better understand any psychosocial concerns. Juana’s score of 10 on the General Anxiety Disorder-7 scale indicated moderate anxiety. She reported symptoms consistent with social anxiety disorder contributing to school avoidance.

The physician consulted with the clinic’s behavioral health consultant (BHC) to confirm the multimodal treatment plan, which was then discussed with Juana and her mother. The physician discussed medication options (SSRIs) and provided documentation (in both English and Spanish) from the visit to Juana’s mother so she could initiate a school-based intervention with the Child Study Team at Juana’s school. A plan for CBT—including a collaborative contingency management plan between the patient and her parent (eg, a reward chart for attending school) and exposure interventions (eg, a graduated plan to participate in school-based activities with the end goal to resume full school attendance)—was developed with the BHC. Biweekly follow-up appointments were scheduled with the BHC and monthly appointments were scheduled with the physician to reinforce the interventions.

CORRESPONDENCE

Meredith L. C. Williamson, PhD, 2900 East 29th Street, Suite 100, Bryan, TX 77840; meredith.williamson@tamu.edu

1. School Avoidance Alliance. School avoidance facts. Published September 16, 2021. Accessed July 27, 2023. https://schoolavoidance.org/school-avoidance-facts/

2. Kearney CA. School Refusal Behavior in Youth: A Functional Approach to Assessment and Treatment. American Psychological Association; 2001.

3. US Department of Education. Chronic absenteeism in the nation’s schools: a hidden educational crisis. Updated January 2019. Accessed August 3, 2023. www2.ed.gov/datastory/chronicabsenteeism.html

4. Allen CW, Diamond-Myrsten S, Rollins LK. School absenteeism in children and adolescents. Am Fam Physician. 2018;98:738-744.

5. Gonzálvez C, Díaz-Herrero Á, Vicent M, et al. School refusal behavior: latent class analysis approach and its relationship with psychopathological symptoms. Curr Psychology. 2022;41:2078-2088. doi: 10.1007/s12144-020-00711-6

6. Fremont WP. School refusal in children and adolescents. Am Fam Physician. 2003;68:1555-1560.

7. McShane G, Walter G, Rey JM. Characteristics of adolescents with school refusal. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2001;35:822-826. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1614.2001.00955.x

8. Kearney CA, Silverman WK. The evolution and reconciliation of taxonomic strategies for school refusal behavior. Clin Psychology Sci Pract. 1996;3:339-354. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2850.1996.tb00087.x

9. Kearney CA, Albano AM. School Refusal Assessment Scale-Revised C. Oxford University Press; 2007.

10. Heyne D. School refusal. In: Fisher JE, O’Donohue WT (eds). Practitioner’s Guide to Evidence-based Psychotherapy. Springer Science + Business Media. 2006;600-619. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-28370-8_60

11. Ghandour RM, Sherman LJ, Vladutiu CJ, et al. Prevalence and treatment of depression, anxiety, and conduct problems in US children. J Pediatrics. 2019;206:256-267.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.09.021

12. US Census Bureau. 2020 National Survey of Children’s Health: Topical Frequencies. Published June 2, 2021. Accessed August 4, 2023. www2.census.gov/programs-surveys/nsch/technical-documentation/codebook/NSCH_2020_Topical_Frequencies.pdf

13. USPSTF. Anxiety in children and adolescents: screening. Final Recommendation Statement. Published October 11, 2022. Accessed August 4, 2023. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/screening-anxiety-children-adolescents

14. Maynard BR, Brendel KE, Bulanda JJ, et al. Psychosocial interventions for school refusal with primary and secondary school students: a systematic review. Campbell Systematic Rev. 2015;11:1-76. doi: 10.4073/csr.2015.12

15. Kearney CA, Albano AM. When Children Refuse School: Parent Workbook. 3rd ed. Oxford University Press; 2018. doi: 10.1093/med-psych/9780190604080.001.0001

16. Heyne DA, Sauter FM. School refusal. In: Essau CA, Ollendick TH. The Wiley-Blackwell Handbook of the Treatment of Childhood and Adolescent Anxiety. Wiley Blackwell; 2013:471-517.

17. Kowalchuk A, Gonzalez SJ, Zoorob RJ. Anxiety disorders in children and adolescents. Am Fam Physician. 2022;106:657-664.

THE CASE

Juana*, a 10-year-old who identifies as a cisgender, Hispanic female, was referred to our integrated behavioral health program by her primary care physician. Her mother was concerned because Juana had been refusing to attend school due to complaints of gastrointestinal upset. This concern began when Juana was in first grade but had increased in severity over the past few months.

Upon further questioning, the patient reported that she initially did not want to attend school due to academic difficulties and bullying. However, since COVID-19, her fears of attending school had significantly worsened. Juana’s mother’s primary language was Spanish and she had limited English proficiency; she reported difficulty communicating with school personnel about Juana’s poor attendance.

Juana had recently had a complete medical work-up for her gastrointestinal concerns, with negative results. Since the negative work-up, Juana’s mother had told her daughter that she would be punished if she didn’t go to school.

●

* The patient’s name has been changed to protect her identity.

School avoidance, also referred to as school refusal, is a symptom of an emotional condition that manifests as a child refusing to go to school or having difficulty going to school or remaining in the classroom for the entire day. School avoidance is not a clinical diagnosis but often is related to an underlying disorder.1

School avoidance is common, affecting 5% to 28% of youth sometime in their school career.2 Available data are not specific to school avoidance but focus on chronic absenteeism (missing ≥ 15 days per school year). Rates of chronic absenteeism are high in elementary and middle school (about 14% each) and tend to increase in high school (about 21%).3 Students with disabilities are 1.5 times more likely to be chronically absent than students without disabilities.3 Compared to White students, American Indian and Pacific Islander students are > 50% more likely, Black students 40% more likely, and Hispanic students 17% more likely to miss ≥ 3 weeks of school.3 Rates of chronic absenteeism are similar (about 16%) for males and females.3

Absenteeism can have immediate and long-term negative effects.4 School attendance issues are correlated to negative life outcomes, such as delinquency, teen pregnancy, substance use, and poor academic achievement.5 According to the US Department of Education, individuals who chronically miss school are less likely to achieve educational milestones (particularly in younger years) and may be more likely to drop out of school.3

What school avoidance is (and what it isn’t)

It is important to distinguish school avoidance from truancy. Truancy often is associated with antisocial behavior such as lying and stealing, while school avoidance occurs in the absence of significant antisocial disorders.6 With truancy, the absence usually is hidden from the parent. In contrast, with school avoidance, the parents usually know where their child is; the child often spends the day secluded in their bedroom. Students who engage in truancy do not demonstrate excessive anxiety about attending school but may have decreased interest in schoolwork and academic performance.6 With school avoidance, the child exhibits severe emotional distress about attending school but is willing to complete schoolwork at home.

Why children may avoid school

School avoidance is a biopsychosocial condition with a multitude of underlying causes.4 It is associated most commonly with anxiety disorders and neurodevelopmental disorders, including but not limited to learning disabilities and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.1 Depressive disorders also have been associated with school avoidance.7 Social concerns related to changes with school personnel or classes, academic challenges, bullying, health emergencies, and family stressors also can result in symptoms of school avoidance.1

Continue to: A child seeking to avoid...

A child seeking to avoid school may be motivated by potential negative and/or positive effects of doing so. Kearney and Silverman8 identified 4 primary functions of school refusal behaviors:

- avoiding stimuli at school that lend to negative affect (depression, anxiety)

- escaping the social interactions and/or situations for evaluation that occur at school

- gaining more attention from caregivers, and

- obtaining tangible rewards or benefits outside the school environment.

How school avoidance manifests

School avoidance has attributes of internalizing (depression, anxiety, somatic complaints) and externalizing (aggression, tantrums, running away, clinginess) behaviors. It can cause distress for the student, parents and caregivers, and school personnel.

The avoidance may manifest with behaviors such as crying, hiding, emotional outbursts, and refusing to move prior to the start of the school day. Additionally, the child may beg their parents not to make them go to school or, when at school, they may leave the classroom to go to a safe place such as the nurse’s or counselor’s office.

The avoidance may occur abruptly, such as after a break in the school schedule or a change of school. Or it may be the final result of the student’s gradual inability to cope with the underlying issue.

How to assess for school avoidance

Due to the multifactorial nature of this presenting concern, a comprehensive evaluation is recommended when school avoidance is reported.4 Often the child will present with physical symptoms, such as abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, headaches, shortness of breath, dizziness, chest pain, and palpitations. A thorough medical examination should be performed to rule out a physiological cause. The medical visit should include clinical interviews with the patient and family members or guardians.

Continue to: To identify school avoidance...

To identify school avoidance in pediatric and adolescent populations, medical history and physical examination—along with social history to better understand familial, social, and academic concerns—should be a regular part of the medical encounter. The School Refusal Assessment Scale-Revised (SRAS-R) for both parents and their children was developed to assess for school avoidance and can be utilized within the primary care setting. Additional psychiatric history for both the family and patient may be beneficial, due to associations between parental mental health concerns and school avoidance in their children.9,10

Assessment for an underlying mental health condition, such as an anxiety or depressive disorder, should be completed when a patient presents with school avoidance.4 More than one-third of children with behavioral problems, such as school avoidance, have been diagnosed with anxiety.11 The 2020 National Survey of Children’s Health found that 7.8% of children and adolescents ages 3 to 17 years had a current anxiety disorder, leading the US Preventive Services Task Force to recommend screening for anxiety in children and adolescents ages 8 to 18 years.12,13 Furthermore, if academic achievement is of concern, then consideration of further assessment for neurodevelopmental disorders is warranted.1

Treatment is multimodal and multidisciplinary

Treatment for school avoidance is often multimodal and may involve interdisciplinary, team-based care including the medical provider, school system (eg, Child Study Team), family, and mental health care provider.1,4

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is the most-studied intervention for school avoidance, with behavioral, exposure-based interventions often central to therapeutic gains in treatment.1,14,15 The goals of treatment are to increase school attendance while decreasing emotional distress through various strategies, including exposure-based interventions, contingency management with parents and school staff, relaxation training, and/or social skills training.14,16 Collaborative involvement between the medical provider and the school system is key to successful treatment.

Medication may be considered alone or in combination with CBT when comorbid mental health conditions have been identified. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs)—including fluoxetine, sertraline, and escitalopram—are considered first-line treatment for anxiety in children and adolescents.17 Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), such as duloxetine and venlafaxine, also have been shown to be effective. Duloxetine is the only medication approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for treatment of generalized anxiety disorder in children ages 7 years and older.17

Continue to: SSRIs and SNRIs have a boxed warning...

SSRIs and SNRIs have a boxed warning from the FDA for increased suicidal thoughts and behaviors in children and adolescents. Although this risk is rare, it should be discussed with the patient and parent/guardian in order to obtain informed consent prior to treatment initiation.

Medication should be started at the lowest possible dose and increased gradually. Patients should remain on the medication for 6 to 12 months after symptom resolution and should be tapered during a nonstressful time, such as the summer break.

THE CASE

Based on the concerns of continued school refusal after negative gastrointestinal work-up, Juana’s physician screened her for anxiety and conducted a clinical interview to better understand any psychosocial concerns. Juana’s score of 10 on the General Anxiety Disorder-7 scale indicated moderate anxiety. She reported symptoms consistent with social anxiety disorder contributing to school avoidance.

The physician consulted with the clinic’s behavioral health consultant (BHC) to confirm the multimodal treatment plan, which was then discussed with Juana and her mother. The physician discussed medication options (SSRIs) and provided documentation (in both English and Spanish) from the visit to Juana’s mother so she could initiate a school-based intervention with the Child Study Team at Juana’s school. A plan for CBT—including a collaborative contingency management plan between the patient and her parent (eg, a reward chart for attending school) and exposure interventions (eg, a graduated plan to participate in school-based activities with the end goal to resume full school attendance)—was developed with the BHC. Biweekly follow-up appointments were scheduled with the BHC and monthly appointments were scheduled with the physician to reinforce the interventions.

CORRESPONDENCE

Meredith L. C. Williamson, PhD, 2900 East 29th Street, Suite 100, Bryan, TX 77840; meredith.williamson@tamu.edu

THE CASE

Juana*, a 10-year-old who identifies as a cisgender, Hispanic female, was referred to our integrated behavioral health program by her primary care physician. Her mother was concerned because Juana had been refusing to attend school due to complaints of gastrointestinal upset. This concern began when Juana was in first grade but had increased in severity over the past few months.

Upon further questioning, the patient reported that she initially did not want to attend school due to academic difficulties and bullying. However, since COVID-19, her fears of attending school had significantly worsened. Juana’s mother’s primary language was Spanish and she had limited English proficiency; she reported difficulty communicating with school personnel about Juana’s poor attendance.

Juana had recently had a complete medical work-up for her gastrointestinal concerns, with negative results. Since the negative work-up, Juana’s mother had told her daughter that she would be punished if she didn’t go to school.

●

* The patient’s name has been changed to protect her identity.

School avoidance, also referred to as school refusal, is a symptom of an emotional condition that manifests as a child refusing to go to school or having difficulty going to school or remaining in the classroom for the entire day. School avoidance is not a clinical diagnosis but often is related to an underlying disorder.1

School avoidance is common, affecting 5% to 28% of youth sometime in their school career.2 Available data are not specific to school avoidance but focus on chronic absenteeism (missing ≥ 15 days per school year). Rates of chronic absenteeism are high in elementary and middle school (about 14% each) and tend to increase in high school (about 21%).3 Students with disabilities are 1.5 times more likely to be chronically absent than students without disabilities.3 Compared to White students, American Indian and Pacific Islander students are > 50% more likely, Black students 40% more likely, and Hispanic students 17% more likely to miss ≥ 3 weeks of school.3 Rates of chronic absenteeism are similar (about 16%) for males and females.3

Absenteeism can have immediate and long-term negative effects.4 School attendance issues are correlated to negative life outcomes, such as delinquency, teen pregnancy, substance use, and poor academic achievement.5 According to the US Department of Education, individuals who chronically miss school are less likely to achieve educational milestones (particularly in younger years) and may be more likely to drop out of school.3

What school avoidance is (and what it isn’t)

It is important to distinguish school avoidance from truancy. Truancy often is associated with antisocial behavior such as lying and stealing, while school avoidance occurs in the absence of significant antisocial disorders.6 With truancy, the absence usually is hidden from the parent. In contrast, with school avoidance, the parents usually know where their child is; the child often spends the day secluded in their bedroom. Students who engage in truancy do not demonstrate excessive anxiety about attending school but may have decreased interest in schoolwork and academic performance.6 With school avoidance, the child exhibits severe emotional distress about attending school but is willing to complete schoolwork at home.

Why children may avoid school

School avoidance is a biopsychosocial condition with a multitude of underlying causes.4 It is associated most commonly with anxiety disorders and neurodevelopmental disorders, including but not limited to learning disabilities and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.1 Depressive disorders also have been associated with school avoidance.7 Social concerns related to changes with school personnel or classes, academic challenges, bullying, health emergencies, and family stressors also can result in symptoms of school avoidance.1

Continue to: A child seeking to avoid...

A child seeking to avoid school may be motivated by potential negative and/or positive effects of doing so. Kearney and Silverman8 identified 4 primary functions of school refusal behaviors:

- avoiding stimuli at school that lend to negative affect (depression, anxiety)

- escaping the social interactions and/or situations for evaluation that occur at school

- gaining more attention from caregivers, and

- obtaining tangible rewards or benefits outside the school environment.

How school avoidance manifests

School avoidance has attributes of internalizing (depression, anxiety, somatic complaints) and externalizing (aggression, tantrums, running away, clinginess) behaviors. It can cause distress for the student, parents and caregivers, and school personnel.

The avoidance may manifest with behaviors such as crying, hiding, emotional outbursts, and refusing to move prior to the start of the school day. Additionally, the child may beg their parents not to make them go to school or, when at school, they may leave the classroom to go to a safe place such as the nurse’s or counselor’s office.

The avoidance may occur abruptly, such as after a break in the school schedule or a change of school. Or it may be the final result of the student’s gradual inability to cope with the underlying issue.

How to assess for school avoidance

Due to the multifactorial nature of this presenting concern, a comprehensive evaluation is recommended when school avoidance is reported.4 Often the child will present with physical symptoms, such as abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, headaches, shortness of breath, dizziness, chest pain, and palpitations. A thorough medical examination should be performed to rule out a physiological cause. The medical visit should include clinical interviews with the patient and family members or guardians.

Continue to: To identify school avoidance...

To identify school avoidance in pediatric and adolescent populations, medical history and physical examination—along with social history to better understand familial, social, and academic concerns—should be a regular part of the medical encounter. The School Refusal Assessment Scale-Revised (SRAS-R) for both parents and their children was developed to assess for school avoidance and can be utilized within the primary care setting. Additional psychiatric history for both the family and patient may be beneficial, due to associations between parental mental health concerns and school avoidance in their children.9,10

Assessment for an underlying mental health condition, such as an anxiety or depressive disorder, should be completed when a patient presents with school avoidance.4 More than one-third of children with behavioral problems, such as school avoidance, have been diagnosed with anxiety.11 The 2020 National Survey of Children’s Health found that 7.8% of children and adolescents ages 3 to 17 years had a current anxiety disorder, leading the US Preventive Services Task Force to recommend screening for anxiety in children and adolescents ages 8 to 18 years.12,13 Furthermore, if academic achievement is of concern, then consideration of further assessment for neurodevelopmental disorders is warranted.1

Treatment is multimodal and multidisciplinary

Treatment for school avoidance is often multimodal and may involve interdisciplinary, team-based care including the medical provider, school system (eg, Child Study Team), family, and mental health care provider.1,4

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is the most-studied intervention for school avoidance, with behavioral, exposure-based interventions often central to therapeutic gains in treatment.1,14,15 The goals of treatment are to increase school attendance while decreasing emotional distress through various strategies, including exposure-based interventions, contingency management with parents and school staff, relaxation training, and/or social skills training.14,16 Collaborative involvement between the medical provider and the school system is key to successful treatment.

Medication may be considered alone or in combination with CBT when comorbid mental health conditions have been identified. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs)—including fluoxetine, sertraline, and escitalopram—are considered first-line treatment for anxiety in children and adolescents.17 Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), such as duloxetine and venlafaxine, also have been shown to be effective. Duloxetine is the only medication approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for treatment of generalized anxiety disorder in children ages 7 years and older.17

Continue to: SSRIs and SNRIs have a boxed warning...

SSRIs and SNRIs have a boxed warning from the FDA for increased suicidal thoughts and behaviors in children and adolescents. Although this risk is rare, it should be discussed with the patient and parent/guardian in order to obtain informed consent prior to treatment initiation.

Medication should be started at the lowest possible dose and increased gradually. Patients should remain on the medication for 6 to 12 months after symptom resolution and should be tapered during a nonstressful time, such as the summer break.

THE CASE

Based on the concerns of continued school refusal after negative gastrointestinal work-up, Juana’s physician screened her for anxiety and conducted a clinical interview to better understand any psychosocial concerns. Juana’s score of 10 on the General Anxiety Disorder-7 scale indicated moderate anxiety. She reported symptoms consistent with social anxiety disorder contributing to school avoidance.

The physician consulted with the clinic’s behavioral health consultant (BHC) to confirm the multimodal treatment plan, which was then discussed with Juana and her mother. The physician discussed medication options (SSRIs) and provided documentation (in both English and Spanish) from the visit to Juana’s mother so she could initiate a school-based intervention with the Child Study Team at Juana’s school. A plan for CBT—including a collaborative contingency management plan between the patient and her parent (eg, a reward chart for attending school) and exposure interventions (eg, a graduated plan to participate in school-based activities with the end goal to resume full school attendance)—was developed with the BHC. Biweekly follow-up appointments were scheduled with the BHC and monthly appointments were scheduled with the physician to reinforce the interventions.

CORRESPONDENCE

Meredith L. C. Williamson, PhD, 2900 East 29th Street, Suite 100, Bryan, TX 77840; meredith.williamson@tamu.edu

1. School Avoidance Alliance. School avoidance facts. Published September 16, 2021. Accessed July 27, 2023. https://schoolavoidance.org/school-avoidance-facts/

2. Kearney CA. School Refusal Behavior in Youth: A Functional Approach to Assessment and Treatment. American Psychological Association; 2001.

3. US Department of Education. Chronic absenteeism in the nation’s schools: a hidden educational crisis. Updated January 2019. Accessed August 3, 2023. www2.ed.gov/datastory/chronicabsenteeism.html

4. Allen CW, Diamond-Myrsten S, Rollins LK. School absenteeism in children and adolescents. Am Fam Physician. 2018;98:738-744.

5. Gonzálvez C, Díaz-Herrero Á, Vicent M, et al. School refusal behavior: latent class analysis approach and its relationship with psychopathological symptoms. Curr Psychology. 2022;41:2078-2088. doi: 10.1007/s12144-020-00711-6

6. Fremont WP. School refusal in children and adolescents. Am Fam Physician. 2003;68:1555-1560.

7. McShane G, Walter G, Rey JM. Characteristics of adolescents with school refusal. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2001;35:822-826. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1614.2001.00955.x

8. Kearney CA, Silverman WK. The evolution and reconciliation of taxonomic strategies for school refusal behavior. Clin Psychology Sci Pract. 1996;3:339-354. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2850.1996.tb00087.x

9. Kearney CA, Albano AM. School Refusal Assessment Scale-Revised C. Oxford University Press; 2007.

10. Heyne D. School refusal. In: Fisher JE, O’Donohue WT (eds). Practitioner’s Guide to Evidence-based Psychotherapy. Springer Science + Business Media. 2006;600-619. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-28370-8_60

11. Ghandour RM, Sherman LJ, Vladutiu CJ, et al. Prevalence and treatment of depression, anxiety, and conduct problems in US children. J Pediatrics. 2019;206:256-267.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.09.021

12. US Census Bureau. 2020 National Survey of Children’s Health: Topical Frequencies. Published June 2, 2021. Accessed August 4, 2023. www2.census.gov/programs-surveys/nsch/technical-documentation/codebook/NSCH_2020_Topical_Frequencies.pdf

13. USPSTF. Anxiety in children and adolescents: screening. Final Recommendation Statement. Published October 11, 2022. Accessed August 4, 2023. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/screening-anxiety-children-adolescents

14. Maynard BR, Brendel KE, Bulanda JJ, et al. Psychosocial interventions for school refusal with primary and secondary school students: a systematic review. Campbell Systematic Rev. 2015;11:1-76. doi: 10.4073/csr.2015.12

15. Kearney CA, Albano AM. When Children Refuse School: Parent Workbook. 3rd ed. Oxford University Press; 2018. doi: 10.1093/med-psych/9780190604080.001.0001

16. Heyne DA, Sauter FM. School refusal. In: Essau CA, Ollendick TH. The Wiley-Blackwell Handbook of the Treatment of Childhood and Adolescent Anxiety. Wiley Blackwell; 2013:471-517.

17. Kowalchuk A, Gonzalez SJ, Zoorob RJ. Anxiety disorders in children and adolescents. Am Fam Physician. 2022;106:657-664.

1. School Avoidance Alliance. School avoidance facts. Published September 16, 2021. Accessed July 27, 2023. https://schoolavoidance.org/school-avoidance-facts/

2. Kearney CA. School Refusal Behavior in Youth: A Functional Approach to Assessment and Treatment. American Psychological Association; 2001.

3. US Department of Education. Chronic absenteeism in the nation’s schools: a hidden educational crisis. Updated January 2019. Accessed August 3, 2023. www2.ed.gov/datastory/chronicabsenteeism.html

4. Allen CW, Diamond-Myrsten S, Rollins LK. School absenteeism in children and adolescents. Am Fam Physician. 2018;98:738-744.

5. Gonzálvez C, Díaz-Herrero Á, Vicent M, et al. School refusal behavior: latent class analysis approach and its relationship with psychopathological symptoms. Curr Psychology. 2022;41:2078-2088. doi: 10.1007/s12144-020-00711-6

6. Fremont WP. School refusal in children and adolescents. Am Fam Physician. 2003;68:1555-1560.

7. McShane G, Walter G, Rey JM. Characteristics of adolescents with school refusal. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2001;35:822-826. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1614.2001.00955.x

8. Kearney CA, Silverman WK. The evolution and reconciliation of taxonomic strategies for school refusal behavior. Clin Psychology Sci Pract. 1996;3:339-354. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2850.1996.tb00087.x

9. Kearney CA, Albano AM. School Refusal Assessment Scale-Revised C. Oxford University Press; 2007.

10. Heyne D. School refusal. In: Fisher JE, O’Donohue WT (eds). Practitioner’s Guide to Evidence-based Psychotherapy. Springer Science + Business Media. 2006;600-619. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-28370-8_60

11. Ghandour RM, Sherman LJ, Vladutiu CJ, et al. Prevalence and treatment of depression, anxiety, and conduct problems in US children. J Pediatrics. 2019;206:256-267.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.09.021

12. US Census Bureau. 2020 National Survey of Children’s Health: Topical Frequencies. Published June 2, 2021. Accessed August 4, 2023. www2.census.gov/programs-surveys/nsch/technical-documentation/codebook/NSCH_2020_Topical_Frequencies.pdf

13. USPSTF. Anxiety in children and adolescents: screening. Final Recommendation Statement. Published October 11, 2022. Accessed August 4, 2023. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/screening-anxiety-children-adolescents

14. Maynard BR, Brendel KE, Bulanda JJ, et al. Psychosocial interventions for school refusal with primary and secondary school students: a systematic review. Campbell Systematic Rev. 2015;11:1-76. doi: 10.4073/csr.2015.12

15. Kearney CA, Albano AM. When Children Refuse School: Parent Workbook. 3rd ed. Oxford University Press; 2018. doi: 10.1093/med-psych/9780190604080.001.0001

16. Heyne DA, Sauter FM. School refusal. In: Essau CA, Ollendick TH. The Wiley-Blackwell Handbook of the Treatment of Childhood and Adolescent Anxiety. Wiley Blackwell; 2013:471-517.

17. Kowalchuk A, Gonzalez SJ, Zoorob RJ. Anxiety disorders in children and adolescents. Am Fam Physician. 2022;106:657-664.

Suicide screening: How to recognize and treat at-risk adults

THE CASE

Emily T,* a 30-year-old woman, visited her primary care physician as follow-up to reassess her grief over the loss of her father a year earlier. Emily was her father’s primary caretaker and still lived alone in his home. Emily had a history of chronic pain and major depressive disorder and had expressed feelings of worthlessness and hopelessness about her future since her father’s passing. In addition to her continuing grief response, she reported feeling worse on most days. She completed the Patient Health Questionnaire-9, and results indicated anhedonia, depressed mood, psychomotor retardation, hypersomnia, decreased appetite, decreased concentration, and thoughts that she would be better off dead.

- HOW WOULD YOU PROCEED WITH THIS PATIENT?

* The patient’s name has been changed to protect her identity.

In the United States, 1 suicide occurs on average every 12 minutes; lifetime prevalence of suicide attempts ranges from 1.9% to 8.7%.1 Suicide is the 10th overall cause of death in the United States, and it is the second leading cause of death for adults 18 to 34 years of age.2 In one study, nearly half of suicide victims had contact with primary care providers within 1 month of their suicide.3 Unfortunately, additional research suggests that primary care physicians appropriately screen for suicide in fewer than 40% of patient encounters.4,5

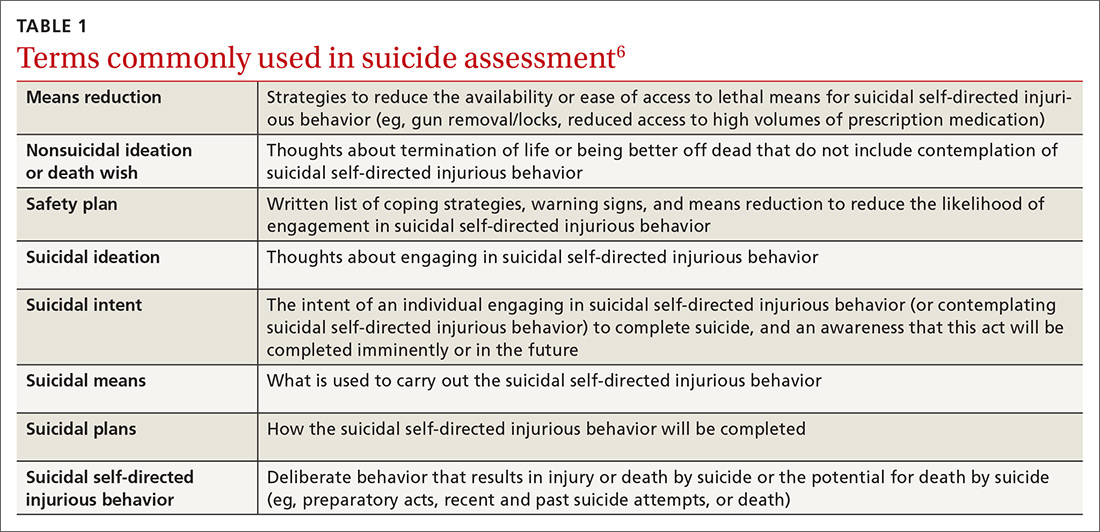

Suicide is defined as “death caused by self-directed injurious behavior with any intent to die as a result of the behavior.”6 When screening for suicide, be aware of the many terms related to suicide evaluation (TABLE 16). Be mindful, too, of the differences between suicidal and nonsuicidal ideation (death wish); the continuum of such thoughts ranges from those that lead to suicide to those that do not.

SUICIDE SCREENING RECOMMENDATIONS VARY

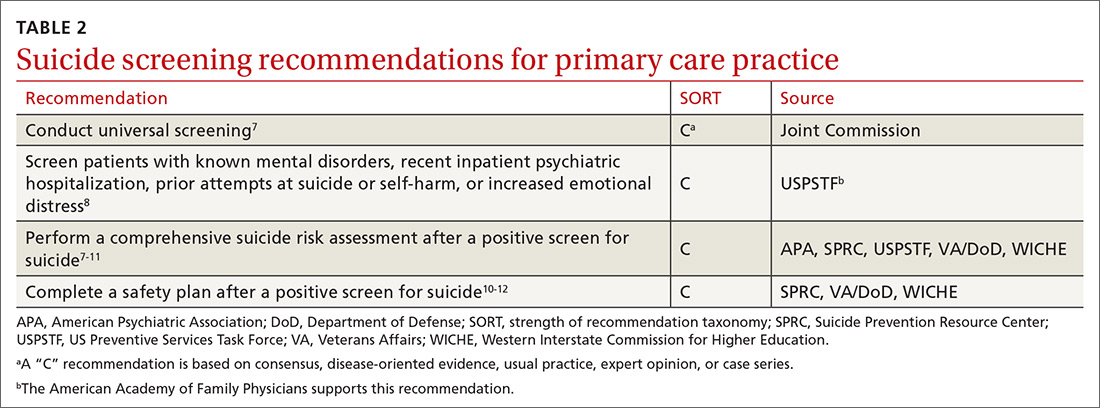

Although most health care providers would agree that intervening with a suicidal patient first requires competence in assessing suicide risk, regulating bodies differ on the use of routine screening and on appropriate screening tools for primary care. The Joint Commission recommends assessing suicide risk with all primary care patients,7 while the US Preventive Services Tasks Force (USPSTF) advises against universal suicide screening in primary care8 due to insufficient evidence that its benefit outweighs potential harm (TABLE 27-12). Instead, the USPSTF recommends screening primary care patients with known mental health disorders, recent inpatient psychiatric hospitalization, prior suicide or self-harm attempts, or increased emotional distress.8 USPSTF does support screening for depression with routine mental health measures that include items assessing suicidality.8,13,14 The American Academy of Family Physicians supports the recommendations by USPSTF.13

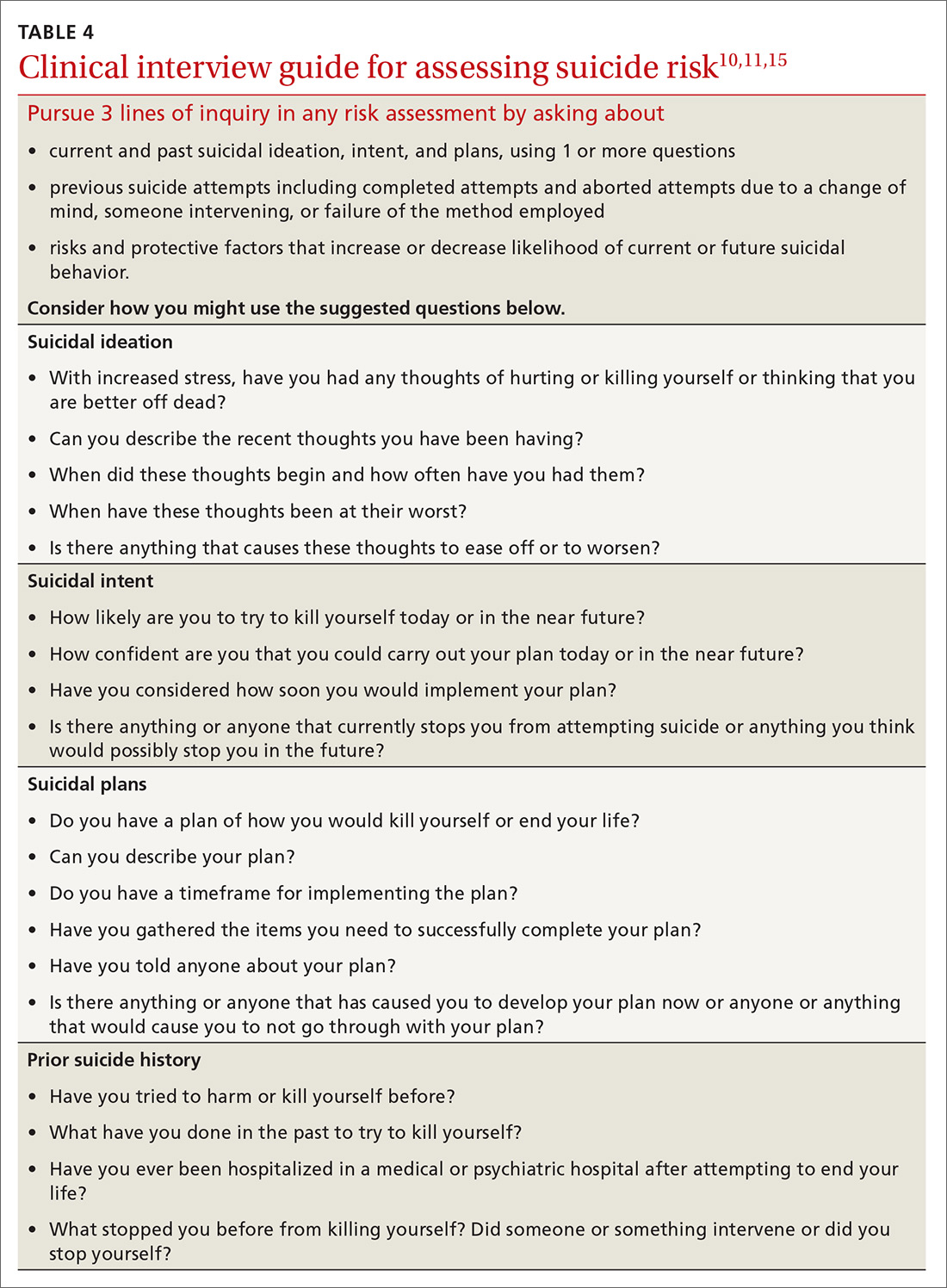

When screening for suicide, a comprehensive suicide risk assessment is recommended by both the Joint Commission and USPSTF.7,8 A comprehensive suicide risk assessment has 4 components: (1) identification of current suicide risk factors, (2) identification of protective factors, (3) inquiry about suicidal ideation, intent, and plan, and (4) primary care practitioner judgment of risk level and plan for clinical intervention.9-11

Take into account both risks and protective factors

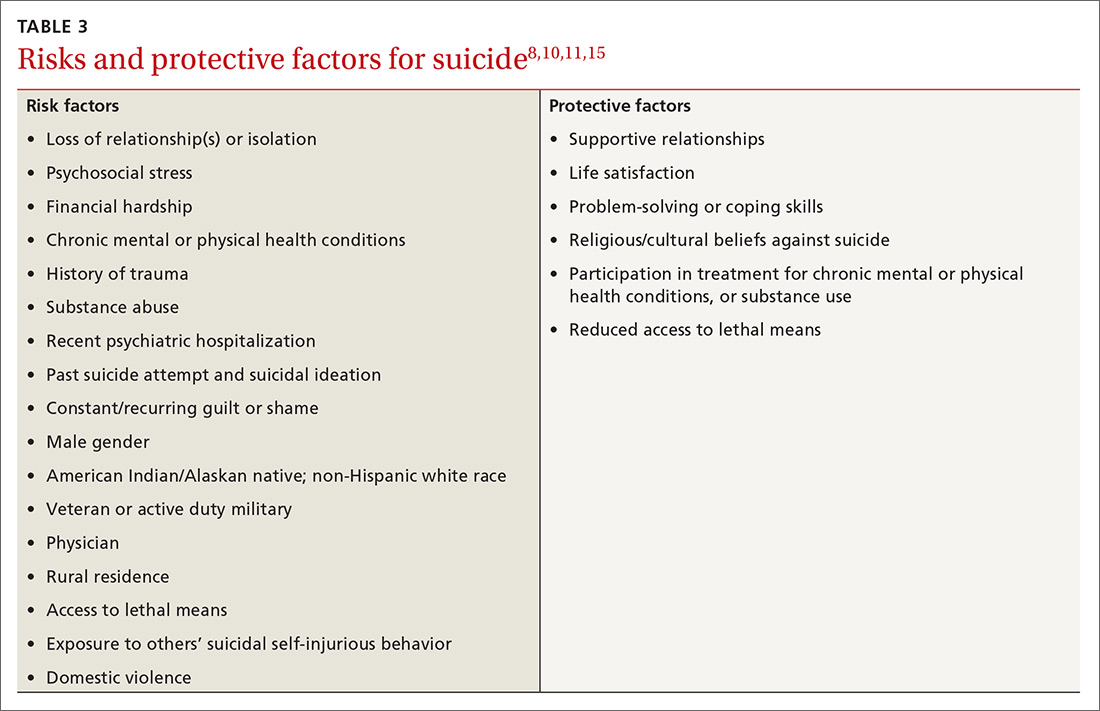

Unfortunately, there is no “typical” description of a patient at risk for suicide and no validated models to predict suicide risk.8,10 A multitude of factors, both individual and societal, can increase or reduce risk of suicide.11,15 Each patient’s unique history includes risk factors for suicide including precipitating events (eg, job loss, termination of a relationship, death of a loved one) and protective factors that may be evaluated to determine overall risk for suicide (TABLE 38,10,11,15). According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), there are several warning signs for patients who may be at greater risk for suicide: isolation, increased anxiety or anger, obtaining lethal means (eg, guns, knives, ropes), frequent mood swings, sleep changes, feeling trapped or in pain, increased substance use, discussing plans for death or wishes of death, and feeling like a burden.16

CHOOSING FROM AMONG SUICIDE SCREENING TOOLS

Brief mental health screening tools such as the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) are commonly used as primary screening tools for suicidal ideation.17 However, to attain a fuller understanding of a patient’s suicidality, select a screening tool that specifically

Continue to: Several screening tools...

Several screening tools are available for exploring a patient’s suicidality. Unfortunately, most of them are supported by limited evidence of effectiveness in identifying suicide risk.8-10 An exception is the well-researched and commonly used Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS).18,19 In a comparative study conducted at 2 primary care clinics, researchers found that the suicide item included in the PHQ-9 provided poor sensitivity but moderate specificity (60% and 84%, respectively),20 while the C-SSRS showed high sensitivity (100%) and specificity (96%-100%) in accurately identifying various suicidal self-injurious behaviors above and beyond what was identified through a structured clinical interview.20 Free copies of the C-SSRS, training materials, and follow-up assessments in multiple languages can be obtained on The Columbia Lighthouse Project Web site (http://cssrs.columbia.edu/).19

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR INTERVENTION

While there is debate regarding whom to screen for suicide, the importance of intervention when a patient is revealed to be at risk is clear. After completing a

When a patient is at high risk for suicide and reports an imminent plan or intent, ensure their safety through inpatient psychiatric hospitalization and then close follow-up upon hospital discharge. First encourage voluntary hospitalization in a collaborative discussion with the patient; resort to involuntary hospitalization only if the patient resists.

What not to do. When the patient does not require immediate hospitalization, evidence recommends against contracting for patient safety via a written contract or requiring patients to verbally guarantee that they will not commit suicide upon leaving a provider’s office.21 Concerns about such contracts include a lack of evidence supporting their use, decreased vigilance by health care workers when such contracts are in place, and questions regarding informed consent and competence.21 Instead, engage a patient who is at moderate or low risk in safety planning, and meet with the patient frequently to discuss continued safety planning through close follow-up (or with a behavioral health provider if available).10-12,22 With patients previously identified as at high risk for suicide who return from inpatient psychiatric hospitalization, continue to screen them for suicide at subsequent visits and engage them in collaborative safety planning.

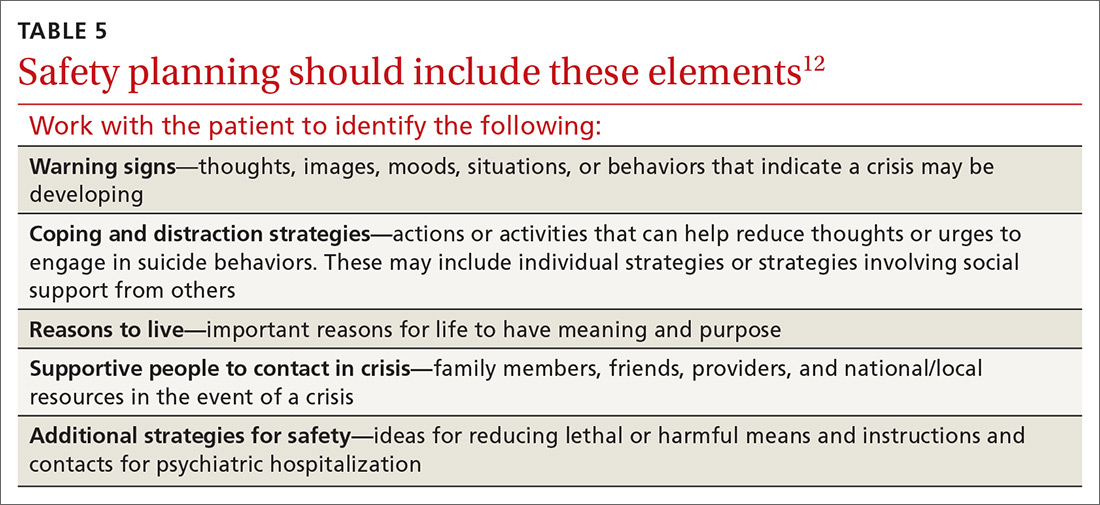

Safety planning (TABLE 512), also known as crisis response planning, is considered a best practice and effective suicide prevention intervention by the Suicide Prevention Resource Center and the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention Best Practices Registry for Suicide Prevention.23 Safety planning involves a collaboration between patient and physician to identify risk factors and protective factors along with crisis resources and strategies to reduce

Continue to: THE CASE

THE CASE

Based on the concerning results from the PHQ-9 suicide item, Emily’s physician conducted a comprehensive suicide risk assessment using both clinical interview and the C-SSRS. Emily reported that she was experiencing daily suicidal ideations due to a lack of social support and longing to be with her deceased father. She had not previously attempted suicide and had no imminent intent to commit suicide. Emily did, however, have a plan to overdose on opioid medications she had been collecting for many months. Her physician determined that Emily was at moderate risk for suicide and consulted with the clinic’s behavioral health consultant, a psychologist, to confirm a treatment plan.

Emily and her physician collaboratively developed a safety plan including means reduction. Emily agreed to have her physician contact a friend to assist with safety planning, and she brought her opioid medications to the primary care clinic for disposal. Follow-up appointments were scheduled with the physician for every other week. The psychologist was available at the time of the first biweekly appointment to consult with the physician if needed. This initial appointment was focused on Emily’s suicide risk and her ability to engage in safety planning. In addition, the physician recommended that Emily schedule time with the psychologist so that she could work on her grief and depressive symptoms.

After several weeks of the biweekly appointments with both the primary care provider and the psychologist, Emily was no longer reporting suicidal ideation and she was ready to engage in coping strategies to deal with her grief and depressive symptoms.

CORRESPONDENCE

Meredith L.C. Williamson, PhD, 2900 E. 29th Street, Suite 100, Bryan, TX 77802; meredith.williamson@tamu.edu.

1. Nock MK, Borges G, Bromet EJ, et al. Suicide and suicidal behavior. Epidemiol Rev. 2008;30:133-154.

2. National Institute of Mental Health. Suicide. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/suicide.shtml#part_154968. Accessed October 18, 2019.

3. Luoma JB, Martin CE, Pearson JL. Contact with mental health and primary care providers before suicide: a review of the evidence. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:909-916.

4. Vannoy SD, Robins LS. Suicide-related discussions with depressed primary care patients in the USA: gender and quality gaps. A mixed methods analysis. BMJ Open. 2011;1:e000198.

5. Feldman MD, Franks P, Duberstein PR, et al. Let’s not talk about it: suicide inquiry in primary care. Ann Fam Med. 2007;5:412-418.

6. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Office of the Surgeon General and National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention. 2012 National strategy for suicide prevention: goals and objectives for action. https://mnprc.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/2012-National-Strategy-for-suicide-prevention-goals-and-objectives-for-action.pdf. Accessed October 18, 2019.

7. The Joint Commission. Detecting and treating suicide ideation in all settings. Sentinel Event Alert. 2016;(56):1-7.

8. LeFevre ML, U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for suicide risk in adolescents, adults, and older adults in primary care: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160:719-726.

9. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guidelines for the assessment and treatment of patients with suicidal behaviors. 2010. http://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/suicide.pdf. Accessed October 18, 2019.

10. Department of Veterans Affairs & Department of Defense. VA/DoD clinical practice guideline for assessment and management of patients at risk for suicide. 2013. https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/MH/srb/VADODCP_SuicideRisk_Full.pdf. Accessed October 18, 2019.

11. Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education. Suicide prevention toolkit for primary care practices. 2017. https://www.sprc.org/sites/default/files/Final%20National%20Suicide%20Prevention%20Toolkit%202.15.18%20FINAL.pdf. Accessed October 18, 2019.

12. Stanley B, Brown GK. Safety planning intervention: a brief intervention to mitigate suicide risk. Cogn Behav Pract. 2012;19:256-264.

13. Screening for suicide risk in adolescents, adults, and older adults in primary care: recommendation statement. Am Fam Physician. 2015;91:190F-190I.

14. O’Connor E, Gaynes B, Burda BU, et al. Screening for suicide risk in primary care: a systematic evidence review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Evidence synthesis no. 103. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK137737/. Accessed October 25, 2019.

15. Suicide Prevention Resource Center. Risk and protective factors. https://www.sprc.org/about-suicide/risk-protective-factors. Accessed October 18, 2019.

16. CDC. Suicide rising across the US: more than a mental health concern. https://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/suicide/index.html. Accessed October 18, 2019.

17. Martin A, Rief W, Klaiberg A, et al. Validity of the Brief Patient Health Questionnaire Mood Scale (PHQ-9) in the general population. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2006;28:71-77.

18. Posner K, Brown GK, Stanley B, et al. The Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale: initial validity and internal consistency findings from three multisite studies with adolescents and adults. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168:1266-1277.

19. The Columbia Lighthouse Project. Identify risk. Prevent suicide. http://cssrs.columbia.edu. Accessed October 25, 2019.

20. Uebelacker LA, German NM, Gaudiano BA, et al. Patient health questionnaire depression scale as a suicide screening instrument in depressed primary care patients: a cross-sectional study. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2011;13:pii: PCC.10m01027.

21. Hoffman RM. Contracting for safety: a misused tool. Pa Patient Saf Advis. 2013;10:82-84.

22. Stanley B, Brown GK, Brenner LA, et al. Comparison of the safety planning intervention with follow-up vs usual care of suicidal patients treated in the emergency department. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75:894-900.

23. Suicide Prevention Resource Center. Safety planning in emergency settings. http://www.sprc.org/news/safety-planning-emergency-settings. Accessed October 25, 2019.

THE CASE

Emily T,* a 30-year-old woman, visited her primary care physician as follow-up to reassess her grief over the loss of her father a year earlier. Emily was her father’s primary caretaker and still lived alone in his home. Emily had a history of chronic pain and major depressive disorder and had expressed feelings of worthlessness and hopelessness about her future since her father’s passing. In addition to her continuing grief response, she reported feeling worse on most days. She completed the Patient Health Questionnaire-9, and results indicated anhedonia, depressed mood, psychomotor retardation, hypersomnia, decreased appetite, decreased concentration, and thoughts that she would be better off dead.

- HOW WOULD YOU PROCEED WITH THIS PATIENT?

* The patient’s name has been changed to protect her identity.

In the United States, 1 suicide occurs on average every 12 minutes; lifetime prevalence of suicide attempts ranges from 1.9% to 8.7%.1 Suicide is the 10th overall cause of death in the United States, and it is the second leading cause of death for adults 18 to 34 years of age.2 In one study, nearly half of suicide victims had contact with primary care providers within 1 month of their suicide.3 Unfortunately, additional research suggests that primary care physicians appropriately screen for suicide in fewer than 40% of patient encounters.4,5

Suicide is defined as “death caused by self-directed injurious behavior with any intent to die as a result of the behavior.”6 When screening for suicide, be aware of the many terms related to suicide evaluation (TABLE 16). Be mindful, too, of the differences between suicidal and nonsuicidal ideation (death wish); the continuum of such thoughts ranges from those that lead to suicide to those that do not.

SUICIDE SCREENING RECOMMENDATIONS VARY

Although most health care providers would agree that intervening with a suicidal patient first requires competence in assessing suicide risk, regulating bodies differ on the use of routine screening and on appropriate screening tools for primary care. The Joint Commission recommends assessing suicide risk with all primary care patients,7 while the US Preventive Services Tasks Force (USPSTF) advises against universal suicide screening in primary care8 due to insufficient evidence that its benefit outweighs potential harm (TABLE 27-12). Instead, the USPSTF recommends screening primary care patients with known mental health disorders, recent inpatient psychiatric hospitalization, prior suicide or self-harm attempts, or increased emotional distress.8 USPSTF does support screening for depression with routine mental health measures that include items assessing suicidality.8,13,14 The American Academy of Family Physicians supports the recommendations by USPSTF.13

When screening for suicide, a comprehensive suicide risk assessment is recommended by both the Joint Commission and USPSTF.7,8 A comprehensive suicide risk assessment has 4 components: (1) identification of current suicide risk factors, (2) identification of protective factors, (3) inquiry about suicidal ideation, intent, and plan, and (4) primary care practitioner judgment of risk level and plan for clinical intervention.9-11

Take into account both risks and protective factors

Unfortunately, there is no “typical” description of a patient at risk for suicide and no validated models to predict suicide risk.8,10 A multitude of factors, both individual and societal, can increase or reduce risk of suicide.11,15 Each patient’s unique history includes risk factors for suicide including precipitating events (eg, job loss, termination of a relationship, death of a loved one) and protective factors that may be evaluated to determine overall risk for suicide (TABLE 38,10,11,15). According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), there are several warning signs for patients who may be at greater risk for suicide: isolation, increased anxiety or anger, obtaining lethal means (eg, guns, knives, ropes), frequent mood swings, sleep changes, feeling trapped or in pain, increased substance use, discussing plans for death or wishes of death, and feeling like a burden.16

CHOOSING FROM AMONG SUICIDE SCREENING TOOLS

Brief mental health screening tools such as the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) are commonly used as primary screening tools for suicidal ideation.17 However, to attain a fuller understanding of a patient’s suicidality, select a screening tool that specifically

Continue to: Several screening tools...

Several screening tools are available for exploring a patient’s suicidality. Unfortunately, most of them are supported by limited evidence of effectiveness in identifying suicide risk.8-10 An exception is the well-researched and commonly used Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS).18,19 In a comparative study conducted at 2 primary care clinics, researchers found that the suicide item included in the PHQ-9 provided poor sensitivity but moderate specificity (60% and 84%, respectively),20 while the C-SSRS showed high sensitivity (100%) and specificity (96%-100%) in accurately identifying various suicidal self-injurious behaviors above and beyond what was identified through a structured clinical interview.20 Free copies of the C-SSRS, training materials, and follow-up assessments in multiple languages can be obtained on The Columbia Lighthouse Project Web site (http://cssrs.columbia.edu/).19

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR INTERVENTION

While there is debate regarding whom to screen for suicide, the importance of intervention when a patient is revealed to be at risk is clear. After completing a

When a patient is at high risk for suicide and reports an imminent plan or intent, ensure their safety through inpatient psychiatric hospitalization and then close follow-up upon hospital discharge. First encourage voluntary hospitalization in a collaborative discussion with the patient; resort to involuntary hospitalization only if the patient resists.

What not to do. When the patient does not require immediate hospitalization, evidence recommends against contracting for patient safety via a written contract or requiring patients to verbally guarantee that they will not commit suicide upon leaving a provider’s office.21 Concerns about such contracts include a lack of evidence supporting their use, decreased vigilance by health care workers when such contracts are in place, and questions regarding informed consent and competence.21 Instead, engage a patient who is at moderate or low risk in safety planning, and meet with the patient frequently to discuss continued safety planning through close follow-up (or with a behavioral health provider if available).10-12,22 With patients previously identified as at high risk for suicide who return from inpatient psychiatric hospitalization, continue to screen them for suicide at subsequent visits and engage them in collaborative safety planning.

Safety planning (TABLE 512), also known as crisis response planning, is considered a best practice and effective suicide prevention intervention by the Suicide Prevention Resource Center and the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention Best Practices Registry for Suicide Prevention.23 Safety planning involves a collaboration between patient and physician to identify risk factors and protective factors along with crisis resources and strategies to reduce

Continue to: THE CASE

THE CASE

Based on the concerning results from the PHQ-9 suicide item, Emily’s physician conducted a comprehensive suicide risk assessment using both clinical interview and the C-SSRS. Emily reported that she was experiencing daily suicidal ideations due to a lack of social support and longing to be with her deceased father. She had not previously attempted suicide and had no imminent intent to commit suicide. Emily did, however, have a plan to overdose on opioid medications she had been collecting for many months. Her physician determined that Emily was at moderate risk for suicide and consulted with the clinic’s behavioral health consultant, a psychologist, to confirm a treatment plan.

Emily and her physician collaboratively developed a safety plan including means reduction. Emily agreed to have her physician contact a friend to assist with safety planning, and she brought her opioid medications to the primary care clinic for disposal. Follow-up appointments were scheduled with the physician for every other week. The psychologist was available at the time of the first biweekly appointment to consult with the physician if needed. This initial appointment was focused on Emily’s suicide risk and her ability to engage in safety planning. In addition, the physician recommended that Emily schedule time with the psychologist so that she could work on her grief and depressive symptoms.

After several weeks of the biweekly appointments with both the primary care provider and the psychologist, Emily was no longer reporting suicidal ideation and she was ready to engage in coping strategies to deal with her grief and depressive symptoms.

CORRESPONDENCE

Meredith L.C. Williamson, PhD, 2900 E. 29th Street, Suite 100, Bryan, TX 77802; meredith.williamson@tamu.edu.

THE CASE

Emily T,* a 30-year-old woman, visited her primary care physician as follow-up to reassess her grief over the loss of her father a year earlier. Emily was her father’s primary caretaker and still lived alone in his home. Emily had a history of chronic pain and major depressive disorder and had expressed feelings of worthlessness and hopelessness about her future since her father’s passing. In addition to her continuing grief response, she reported feeling worse on most days. She completed the Patient Health Questionnaire-9, and results indicated anhedonia, depressed mood, psychomotor retardation, hypersomnia, decreased appetite, decreased concentration, and thoughts that she would be better off dead.

- HOW WOULD YOU PROCEED WITH THIS PATIENT?

* The patient’s name has been changed to protect her identity.

In the United States, 1 suicide occurs on average every 12 minutes; lifetime prevalence of suicide attempts ranges from 1.9% to 8.7%.1 Suicide is the 10th overall cause of death in the United States, and it is the second leading cause of death for adults 18 to 34 years of age.2 In one study, nearly half of suicide victims had contact with primary care providers within 1 month of their suicide.3 Unfortunately, additional research suggests that primary care physicians appropriately screen for suicide in fewer than 40% of patient encounters.4,5

Suicide is defined as “death caused by self-directed injurious behavior with any intent to die as a result of the behavior.”6 When screening for suicide, be aware of the many terms related to suicide evaluation (TABLE 16). Be mindful, too, of the differences between suicidal and nonsuicidal ideation (death wish); the continuum of such thoughts ranges from those that lead to suicide to those that do not.

SUICIDE SCREENING RECOMMENDATIONS VARY

Although most health care providers would agree that intervening with a suicidal patient first requires competence in assessing suicide risk, regulating bodies differ on the use of routine screening and on appropriate screening tools for primary care. The Joint Commission recommends assessing suicide risk with all primary care patients,7 while the US Preventive Services Tasks Force (USPSTF) advises against universal suicide screening in primary care8 due to insufficient evidence that its benefit outweighs potential harm (TABLE 27-12). Instead, the USPSTF recommends screening primary care patients with known mental health disorders, recent inpatient psychiatric hospitalization, prior suicide or self-harm attempts, or increased emotional distress.8 USPSTF does support screening for depression with routine mental health measures that include items assessing suicidality.8,13,14 The American Academy of Family Physicians supports the recommendations by USPSTF.13

When screening for suicide, a comprehensive suicide risk assessment is recommended by both the Joint Commission and USPSTF.7,8 A comprehensive suicide risk assessment has 4 components: (1) identification of current suicide risk factors, (2) identification of protective factors, (3) inquiry about suicidal ideation, intent, and plan, and (4) primary care practitioner judgment of risk level and plan for clinical intervention.9-11

Take into account both risks and protective factors

Unfortunately, there is no “typical” description of a patient at risk for suicide and no validated models to predict suicide risk.8,10 A multitude of factors, both individual and societal, can increase or reduce risk of suicide.11,15 Each patient’s unique history includes risk factors for suicide including precipitating events (eg, job loss, termination of a relationship, death of a loved one) and protective factors that may be evaluated to determine overall risk for suicide (TABLE 38,10,11,15). According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), there are several warning signs for patients who may be at greater risk for suicide: isolation, increased anxiety or anger, obtaining lethal means (eg, guns, knives, ropes), frequent mood swings, sleep changes, feeling trapped or in pain, increased substance use, discussing plans for death or wishes of death, and feeling like a burden.16

CHOOSING FROM AMONG SUICIDE SCREENING TOOLS

Brief mental health screening tools such as the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) are commonly used as primary screening tools for suicidal ideation.17 However, to attain a fuller understanding of a patient’s suicidality, select a screening tool that specifically

Continue to: Several screening tools...

Several screening tools are available for exploring a patient’s suicidality. Unfortunately, most of them are supported by limited evidence of effectiveness in identifying suicide risk.8-10 An exception is the well-researched and commonly used Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS).18,19 In a comparative study conducted at 2 primary care clinics, researchers found that the suicide item included in the PHQ-9 provided poor sensitivity but moderate specificity (60% and 84%, respectively),20 while the C-SSRS showed high sensitivity (100%) and specificity (96%-100%) in accurately identifying various suicidal self-injurious behaviors above and beyond what was identified through a structured clinical interview.20 Free copies of the C-SSRS, training materials, and follow-up assessments in multiple languages can be obtained on The Columbia Lighthouse Project Web site (http://cssrs.columbia.edu/).19

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR INTERVENTION

While there is debate regarding whom to screen for suicide, the importance of intervention when a patient is revealed to be at risk is clear. After completing a

When a patient is at high risk for suicide and reports an imminent plan or intent, ensure their safety through inpatient psychiatric hospitalization and then close follow-up upon hospital discharge. First encourage voluntary hospitalization in a collaborative discussion with the patient; resort to involuntary hospitalization only if the patient resists.

What not to do. When the patient does not require immediate hospitalization, evidence recommends against contracting for patient safety via a written contract or requiring patients to verbally guarantee that they will not commit suicide upon leaving a provider’s office.21 Concerns about such contracts include a lack of evidence supporting their use, decreased vigilance by health care workers when such contracts are in place, and questions regarding informed consent and competence.21 Instead, engage a patient who is at moderate or low risk in safety planning, and meet with the patient frequently to discuss continued safety planning through close follow-up (or with a behavioral health provider if available).10-12,22 With patients previously identified as at high risk for suicide who return from inpatient psychiatric hospitalization, continue to screen them for suicide at subsequent visits and engage them in collaborative safety planning.

Safety planning (TABLE 512), also known as crisis response planning, is considered a best practice and effective suicide prevention intervention by the Suicide Prevention Resource Center and the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention Best Practices Registry for Suicide Prevention.23 Safety planning involves a collaboration between patient and physician to identify risk factors and protective factors along with crisis resources and strategies to reduce

Continue to: THE CASE

THE CASE

Based on the concerning results from the PHQ-9 suicide item, Emily’s physician conducted a comprehensive suicide risk assessment using both clinical interview and the C-SSRS. Emily reported that she was experiencing daily suicidal ideations due to a lack of social support and longing to be with her deceased father. She had not previously attempted suicide and had no imminent intent to commit suicide. Emily did, however, have a plan to overdose on opioid medications she had been collecting for many months. Her physician determined that Emily was at moderate risk for suicide and consulted with the clinic’s behavioral health consultant, a psychologist, to confirm a treatment plan.

Emily and her physician collaboratively developed a safety plan including means reduction. Emily agreed to have her physician contact a friend to assist with safety planning, and she brought her opioid medications to the primary care clinic for disposal. Follow-up appointments were scheduled with the physician for every other week. The psychologist was available at the time of the first biweekly appointment to consult with the physician if needed. This initial appointment was focused on Emily’s suicide risk and her ability to engage in safety planning. In addition, the physician recommended that Emily schedule time with the psychologist so that she could work on her grief and depressive symptoms.

After several weeks of the biweekly appointments with both the primary care provider and the psychologist, Emily was no longer reporting suicidal ideation and she was ready to engage in coping strategies to deal with her grief and depressive symptoms.

CORRESPONDENCE

Meredith L.C. Williamson, PhD, 2900 E. 29th Street, Suite 100, Bryan, TX 77802; meredith.williamson@tamu.edu.

1. Nock MK, Borges G, Bromet EJ, et al. Suicide and suicidal behavior. Epidemiol Rev. 2008;30:133-154.

2. National Institute of Mental Health. Suicide. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/suicide.shtml#part_154968. Accessed October 18, 2019.

3. Luoma JB, Martin CE, Pearson JL. Contact with mental health and primary care providers before suicide: a review of the evidence. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:909-916.

4. Vannoy SD, Robins LS. Suicide-related discussions with depressed primary care patients in the USA: gender and quality gaps. A mixed methods analysis. BMJ Open. 2011;1:e000198.

5. Feldman MD, Franks P, Duberstein PR, et al. Let’s not talk about it: suicide inquiry in primary care. Ann Fam Med. 2007;5:412-418.

6. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Office of the Surgeon General and National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention. 2012 National strategy for suicide prevention: goals and objectives for action. https://mnprc.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/2012-National-Strategy-for-suicide-prevention-goals-and-objectives-for-action.pdf. Accessed October 18, 2019.

7. The Joint Commission. Detecting and treating suicide ideation in all settings. Sentinel Event Alert. 2016;(56):1-7.

8. LeFevre ML, U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for suicide risk in adolescents, adults, and older adults in primary care: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160:719-726.

9. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guidelines for the assessment and treatment of patients with suicidal behaviors. 2010. http://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/suicide.pdf. Accessed October 18, 2019.

10. Department of Veterans Affairs & Department of Defense. VA/DoD clinical practice guideline for assessment and management of patients at risk for suicide. 2013. https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/MH/srb/VADODCP_SuicideRisk_Full.pdf. Accessed October 18, 2019.

11. Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education. Suicide prevention toolkit for primary care practices. 2017. https://www.sprc.org/sites/default/files/Final%20National%20Suicide%20Prevention%20Toolkit%202.15.18%20FINAL.pdf. Accessed October 18, 2019.

12. Stanley B, Brown GK. Safety planning intervention: a brief intervention to mitigate suicide risk. Cogn Behav Pract. 2012;19:256-264.

13. Screening for suicide risk in adolescents, adults, and older adults in primary care: recommendation statement. Am Fam Physician. 2015;91:190F-190I.

14. O’Connor E, Gaynes B, Burda BU, et al. Screening for suicide risk in primary care: a systematic evidence review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Evidence synthesis no. 103. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK137737/. Accessed October 25, 2019.

15. Suicide Prevention Resource Center. Risk and protective factors. https://www.sprc.org/about-suicide/risk-protective-factors. Accessed October 18, 2019.

16. CDC. Suicide rising across the US: more than a mental health concern. https://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/suicide/index.html. Accessed October 18, 2019.

17. Martin A, Rief W, Klaiberg A, et al. Validity of the Brief Patient Health Questionnaire Mood Scale (PHQ-9) in the general population. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2006;28:71-77.

18. Posner K, Brown GK, Stanley B, et al. The Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale: initial validity and internal consistency findings from three multisite studies with adolescents and adults. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168:1266-1277.

19. The Columbia Lighthouse Project. Identify risk. Prevent suicide. http://cssrs.columbia.edu. Accessed October 25, 2019.

20. Uebelacker LA, German NM, Gaudiano BA, et al. Patient health questionnaire depression scale as a suicide screening instrument in depressed primary care patients: a cross-sectional study. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2011;13:pii: PCC.10m01027.

21. Hoffman RM. Contracting for safety: a misused tool. Pa Patient Saf Advis. 2013;10:82-84.

22. Stanley B, Brown GK, Brenner LA, et al. Comparison of the safety planning intervention with follow-up vs usual care of suicidal patients treated in the emergency department. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75:894-900.

23. Suicide Prevention Resource Center. Safety planning in emergency settings. http://www.sprc.org/news/safety-planning-emergency-settings. Accessed October 25, 2019.

1. Nock MK, Borges G, Bromet EJ, et al. Suicide and suicidal behavior. Epidemiol Rev. 2008;30:133-154.

2. National Institute of Mental Health. Suicide. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/suicide.shtml#part_154968. Accessed October 18, 2019.

3. Luoma JB, Martin CE, Pearson JL. Contact with mental health and primary care providers before suicide: a review of the evidence. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:909-916.

4. Vannoy SD, Robins LS. Suicide-related discussions with depressed primary care patients in the USA: gender and quality gaps. A mixed methods analysis. BMJ Open. 2011;1:e000198.

5. Feldman MD, Franks P, Duberstein PR, et al. Let’s not talk about it: suicide inquiry in primary care. Ann Fam Med. 2007;5:412-418.