User login

Best Practices for Clinical Image Collection and Utilization in Patients With Skin of Color

Clinical images are integral to dermatologic care, research, and education. Studies have highlighted the underrepresentation of images of skin of color (SOC) in educational materials,1 clinical trials,2 and research publications.3 Recognition of this disparity has ignited a call to action by dermatologists and dermatologic organizations to address the gap by improving the collection and use of SOC images.4 It is critical to remind dermatologists of the importance of properly obtaining informed consent and ensuring images are not used without a patient’s permission, as images in journal articles, conference presentations, and educational materials can be widely distributed and shared. Herein, we summarize current practices of clinical image storage and make general recommendations on how dermatologists can better protect patient privacy. Certain cultural and social factors in patients with SOC should be considered when obtaining informed consent and collecting images.

Clinical Image Acquisition

Consenting procedures are crucial components of proper image usage. However, current consenting practices are inconsistent across various platforms, including academic journals, websites, printed text, social media, and educational presentations.5

Current regulations for use of patient health information in the United States are governed by the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA)of 1996. Although this act explicitly prohibits use of “full face photographic images and any comparable images” without consent from the patient or the patient’s representative, there is less restriction regarding the use of deidentified images.6 Some clinicians or researchers may consider using a black bar or a masking technique over the eyes or face, but this is not always a sufficient method of anonymizing an image.

One study investigating the different requirements listed by the top 20 dermatology journals (as determined by the Google Scholar h5-index) found that while 95% (19/20) of journals stated that written or signed consent or permission was a requirement for use of patient images, only 20% (4/20) instructed authors to inform the patient or the patient’s representative that images may become available on the internet.5 Once an article is accepted for publication by a medical journal, it eventually may be accessible online; however, patients may not be aware of this factor, which is particularly concerning for those with SOC due to the increased demand for diverse dermatologic resources and images as well as the highly digitalized manner in which we access and share media.

Furthermore, cultural and social factors exist that present challenges to informed decision-making during the consenting process for certain SOC populations such as a lack of trust in the medical and scientific research community, inadequate comprehension of the consent material, health illiteracy, language barriers, or use of complex terminology in consent documentation.7,8 Studies also have shown that patients in ethnic minority groups have greater barriers to health literacy compared to other patient groups, and patients with limited health literacy are less likely to ask questions during their medical visits.9,10 Therefore, when obtaining informed consent for images, it is important that measures are taken to ensure that the patient has full knowledge and understanding of what the consent covers, including the extent to which the images will be used and/or shared and whether the patient’s confidentiality and/or anonymity are at risk.

Recommendations—We propose that dermatologists should follow these recommendations:

1. Encourage influential dermatology organizations such as the American Academy of Dermatology to establish standardized consenting procedures for image acquisition and use, including requirements to provide (a) written consent for all patient images and (b) specific details as to where and how the image may be used and/or shared.

2. Ensure that consent terminology is presented at a sixth-grade reading level or below, minimize the use of medical jargon and complex terms, and provide consent documentation in the patient’s preferred language.

3. Allow patients to take the consent document home so they can have additional time to comprehensively review the material or have it reviewed by family or friends.

4. Employ strategies such as teach-back methods and encourage questions to maximize the level of understanding during the consent process.

Clinical Image Storage

Clinical image storage procedures can have an impact on a patient’s health information remaining anonymous and confidential. In a survey evaluating medical photography use among 153 US board-certified dermatologists, 69.1% of respondents reported emailing or texting images between patients and colleagues. Additionally, 30.3% (46/152) reported having patient photographs stored on their personal phone at the time of the survey, and 39.1% (18/46) of those individuals had images that showed identifiable features, such as the patient’s face or a tattoo.11

Although most providers state that their devices are password protected, it cannot be guaranteed that the device and consequently the images remain secure and inaccessible to unauthorized individuals. As sharing and viewing images continue to play an essential role in assessing disease state, progression, treatment response, and inclusion in research, we must establish and encourage clear guidelines for the storage and retention of such images.

Recommendations—We propose that dermatologists should follow these recommendations:

1. Store clinical images exclusively on password-protected devices and in password-protected files.

2. Use work-related cameras or electronic devices rather than personal devices, unless the personal device is being used to upload directly into the patient’s medical record. In such cases, use a HIPAA-compliant electronic medical record mobile application that does not store images on the application or the device itself.

3. Avoid using text-messaging systems or unencrypted email to share identifying images without clear patient consent.

Clinical Image Use

Once a thorough consenting process has been completed, it is crucial that the use and distribution of the clinical image are in accordance with the terms specified in the original consent. With the current state of technologic advancement, widespread social media usage, and constant sharing of information, adherence to these terms can be challenging. For example, an image initially intended for use in an educational presentation at a professional conference can be shared on social media if an audience member captures a photo of it. In another example, a patient may consent to their image being shown on a dermatologic website but that image can be duplicated and shared on other unauthorized sites and locations. This situation can be particularly distressing to patients whose image may include all or most of their face, an intimate area, or other physical features that they did not wish to share widely.

Individuals identifying as Black/African American, Latino/Hispanic, or Asian have been shown to express less comfort with providing permission for images of a nonidentifiable sensitive area to be taken (or obtained) or for use for teaching irrespective of identifiability compared to their White counterparts,12 which may be due to the aforementioned lack of trust in medical providers and the health care system in general, both of which may contribute to concerns with how a clinical image is used and/or shared. Although consent from a patient or the patient’s representative can be granted, we must ensure that the use of these images adheres to the patient’s initial agreement. Ultimately, medical providers, researchers, and other parties involved in acquiring or sharing patient images have both an ethical and legal responsibility to ensure that anonymity, privacy, and confidentiality are preserved to the greatest extent possible.

Recommendations—We propose that dermatologists should follow these recommendations:

1. Display a message on websites containing patient images stating that the sharing of the images outside the established guidelines and intended use is prohibited.

2. Place a watermark on images to discourage unauthorized duplication.

3. Issue explicit instructions to audiences prohibiting the copying or reproducing of any patient images during teaching events or presentations.

Final Thoughts

The use of clinical images is an essential component of dermatologic care, education, and research. Due to the higher demand for diverse and representative images and the dearth of images in the medical literature, many SOC images have been widely disseminated and utilized by dermatologists, raising concerns of the adequacy of informed consent for the storage and use of such material. Therefore, dermatologists should implement streamlined guidelines and consent procedures to ensure a patient’s informed consent is provided with full knowledge of how and where their images might be used and shared. Additional efforts should be made to protect patients’ privacy and unauthorized use of their images. Furthermore, we encourage our leading dermatology organizations to develop expert consensus on best practices for appropriate clinical image consent, storage, and use.

- Alvarado SM, Feng H. Representation of dark skin images of common dermatologic conditions in educational resources: a cross-sectional analysis [published online June 18, 2020]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:1427-1431. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.06.041

- Charrow A, Xia FD, Joyce C, et al. Diversity in dermatology clinical trials: a systematic review. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:193-198. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.4129

- Marroquin NA, Carboni A, Zueger M, et al. Skin of color representation trends in JAAD case reports 2015-2021: content analysis. JMIR Dermatol. 2023;6:e40816. doi:10.2196/40816

- Kim Y, Miller JJ, Hollins LC. Skin of color matters: a call to action. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:E273-E274. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.11.026

- Nanda JK, Marchetti MA. Consent and deidentification of patient images in dermatology journals: observational study. JMIR Dermatol. 2022;5:E37398. doi:10.2196/37398

- US Department of Health and Human Services. Summary of the HIPAA privacy rule. Updated October 19, 2022. Accessed March 15, 2024. https://www.hhs.gov/hipaa/for-professionals/privacy/laws-regulations/index.html

- Quinn SC, Garza MA, Butler J, et al. Improving informed consent with minority participants: results from researcher and community surveys. J Empir Res Hum Res Ethics. 2012;7:44-55. doi:10.1525/jer.2012.7.5.44

- Hadden KB, Prince LY, Moore TD, et al. Improving readability of informed consents for research at an academic medical institution. J Clin Transl Sci. 2017;1:361-365. doi:10.1017/cts.2017.312

- Muvuka B, Combs RM, Ayangeakaa SD, et al. Health literacy in African-American communities: barriers and strategies. Health Lit Res Pract. 2020;4:E138-E143. doi:10.3928/24748307-20200617-01

- Menendez ME, van Hoorn BT, Mackert M, et al. Patients with limited health literacy ask fewer questions during office visits with hand surgeons. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2017;475:1291-1297. doi:10.1007/s11999-016-5140-5

- Milam EC, Leger MC. Use of medical photography among dermatologists: a nationwide online survey study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:1804-1809. doi:10.1111/jdv.14839

- Leger MC, Wu T, Haimovic A, et al. Patient perspectives on medical photography in dermatology. Dermatol Surg. 2014;40:1028-1037. doi:10.1097/01.DSS.0000452632.22081.79

Clinical images are integral to dermatologic care, research, and education. Studies have highlighted the underrepresentation of images of skin of color (SOC) in educational materials,1 clinical trials,2 and research publications.3 Recognition of this disparity has ignited a call to action by dermatologists and dermatologic organizations to address the gap by improving the collection and use of SOC images.4 It is critical to remind dermatologists of the importance of properly obtaining informed consent and ensuring images are not used without a patient’s permission, as images in journal articles, conference presentations, and educational materials can be widely distributed and shared. Herein, we summarize current practices of clinical image storage and make general recommendations on how dermatologists can better protect patient privacy. Certain cultural and social factors in patients with SOC should be considered when obtaining informed consent and collecting images.

Clinical Image Acquisition

Consenting procedures are crucial components of proper image usage. However, current consenting practices are inconsistent across various platforms, including academic journals, websites, printed text, social media, and educational presentations.5

Current regulations for use of patient health information in the United States are governed by the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA)of 1996. Although this act explicitly prohibits use of “full face photographic images and any comparable images” without consent from the patient or the patient’s representative, there is less restriction regarding the use of deidentified images.6 Some clinicians or researchers may consider using a black bar or a masking technique over the eyes or face, but this is not always a sufficient method of anonymizing an image.

One study investigating the different requirements listed by the top 20 dermatology journals (as determined by the Google Scholar h5-index) found that while 95% (19/20) of journals stated that written or signed consent or permission was a requirement for use of patient images, only 20% (4/20) instructed authors to inform the patient or the patient’s representative that images may become available on the internet.5 Once an article is accepted for publication by a medical journal, it eventually may be accessible online; however, patients may not be aware of this factor, which is particularly concerning for those with SOC due to the increased demand for diverse dermatologic resources and images as well as the highly digitalized manner in which we access and share media.

Furthermore, cultural and social factors exist that present challenges to informed decision-making during the consenting process for certain SOC populations such as a lack of trust in the medical and scientific research community, inadequate comprehension of the consent material, health illiteracy, language barriers, or use of complex terminology in consent documentation.7,8 Studies also have shown that patients in ethnic minority groups have greater barriers to health literacy compared to other patient groups, and patients with limited health literacy are less likely to ask questions during their medical visits.9,10 Therefore, when obtaining informed consent for images, it is important that measures are taken to ensure that the patient has full knowledge and understanding of what the consent covers, including the extent to which the images will be used and/or shared and whether the patient’s confidentiality and/or anonymity are at risk.

Recommendations—We propose that dermatologists should follow these recommendations:

1. Encourage influential dermatology organizations such as the American Academy of Dermatology to establish standardized consenting procedures for image acquisition and use, including requirements to provide (a) written consent for all patient images and (b) specific details as to where and how the image may be used and/or shared.

2. Ensure that consent terminology is presented at a sixth-grade reading level or below, minimize the use of medical jargon and complex terms, and provide consent documentation in the patient’s preferred language.

3. Allow patients to take the consent document home so they can have additional time to comprehensively review the material or have it reviewed by family or friends.

4. Employ strategies such as teach-back methods and encourage questions to maximize the level of understanding during the consent process.

Clinical Image Storage

Clinical image storage procedures can have an impact on a patient’s health information remaining anonymous and confidential. In a survey evaluating medical photography use among 153 US board-certified dermatologists, 69.1% of respondents reported emailing or texting images between patients and colleagues. Additionally, 30.3% (46/152) reported having patient photographs stored on their personal phone at the time of the survey, and 39.1% (18/46) of those individuals had images that showed identifiable features, such as the patient’s face or a tattoo.11

Although most providers state that their devices are password protected, it cannot be guaranteed that the device and consequently the images remain secure and inaccessible to unauthorized individuals. As sharing and viewing images continue to play an essential role in assessing disease state, progression, treatment response, and inclusion in research, we must establish and encourage clear guidelines for the storage and retention of such images.

Recommendations—We propose that dermatologists should follow these recommendations:

1. Store clinical images exclusively on password-protected devices and in password-protected files.

2. Use work-related cameras or electronic devices rather than personal devices, unless the personal device is being used to upload directly into the patient’s medical record. In such cases, use a HIPAA-compliant electronic medical record mobile application that does not store images on the application or the device itself.

3. Avoid using text-messaging systems or unencrypted email to share identifying images without clear patient consent.

Clinical Image Use

Once a thorough consenting process has been completed, it is crucial that the use and distribution of the clinical image are in accordance with the terms specified in the original consent. With the current state of technologic advancement, widespread social media usage, and constant sharing of information, adherence to these terms can be challenging. For example, an image initially intended for use in an educational presentation at a professional conference can be shared on social media if an audience member captures a photo of it. In another example, a patient may consent to their image being shown on a dermatologic website but that image can be duplicated and shared on other unauthorized sites and locations. This situation can be particularly distressing to patients whose image may include all or most of their face, an intimate area, or other physical features that they did not wish to share widely.

Individuals identifying as Black/African American, Latino/Hispanic, or Asian have been shown to express less comfort with providing permission for images of a nonidentifiable sensitive area to be taken (or obtained) or for use for teaching irrespective of identifiability compared to their White counterparts,12 which may be due to the aforementioned lack of trust in medical providers and the health care system in general, both of which may contribute to concerns with how a clinical image is used and/or shared. Although consent from a patient or the patient’s representative can be granted, we must ensure that the use of these images adheres to the patient’s initial agreement. Ultimately, medical providers, researchers, and other parties involved in acquiring or sharing patient images have both an ethical and legal responsibility to ensure that anonymity, privacy, and confidentiality are preserved to the greatest extent possible.

Recommendations—We propose that dermatologists should follow these recommendations:

1. Display a message on websites containing patient images stating that the sharing of the images outside the established guidelines and intended use is prohibited.

2. Place a watermark on images to discourage unauthorized duplication.

3. Issue explicit instructions to audiences prohibiting the copying or reproducing of any patient images during teaching events or presentations.

Final Thoughts

The use of clinical images is an essential component of dermatologic care, education, and research. Due to the higher demand for diverse and representative images and the dearth of images in the medical literature, many SOC images have been widely disseminated and utilized by dermatologists, raising concerns of the adequacy of informed consent for the storage and use of such material. Therefore, dermatologists should implement streamlined guidelines and consent procedures to ensure a patient’s informed consent is provided with full knowledge of how and where their images might be used and shared. Additional efforts should be made to protect patients’ privacy and unauthorized use of their images. Furthermore, we encourage our leading dermatology organizations to develop expert consensus on best practices for appropriate clinical image consent, storage, and use.

Clinical images are integral to dermatologic care, research, and education. Studies have highlighted the underrepresentation of images of skin of color (SOC) in educational materials,1 clinical trials,2 and research publications.3 Recognition of this disparity has ignited a call to action by dermatologists and dermatologic organizations to address the gap by improving the collection and use of SOC images.4 It is critical to remind dermatologists of the importance of properly obtaining informed consent and ensuring images are not used without a patient’s permission, as images in journal articles, conference presentations, and educational materials can be widely distributed and shared. Herein, we summarize current practices of clinical image storage and make general recommendations on how dermatologists can better protect patient privacy. Certain cultural and social factors in patients with SOC should be considered when obtaining informed consent and collecting images.

Clinical Image Acquisition

Consenting procedures are crucial components of proper image usage. However, current consenting practices are inconsistent across various platforms, including academic journals, websites, printed text, social media, and educational presentations.5

Current regulations for use of patient health information in the United States are governed by the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA)of 1996. Although this act explicitly prohibits use of “full face photographic images and any comparable images” without consent from the patient or the patient’s representative, there is less restriction regarding the use of deidentified images.6 Some clinicians or researchers may consider using a black bar or a masking technique over the eyes or face, but this is not always a sufficient method of anonymizing an image.

One study investigating the different requirements listed by the top 20 dermatology journals (as determined by the Google Scholar h5-index) found that while 95% (19/20) of journals stated that written or signed consent or permission was a requirement for use of patient images, only 20% (4/20) instructed authors to inform the patient or the patient’s representative that images may become available on the internet.5 Once an article is accepted for publication by a medical journal, it eventually may be accessible online; however, patients may not be aware of this factor, which is particularly concerning for those with SOC due to the increased demand for diverse dermatologic resources and images as well as the highly digitalized manner in which we access and share media.

Furthermore, cultural and social factors exist that present challenges to informed decision-making during the consenting process for certain SOC populations such as a lack of trust in the medical and scientific research community, inadequate comprehension of the consent material, health illiteracy, language barriers, or use of complex terminology in consent documentation.7,8 Studies also have shown that patients in ethnic minority groups have greater barriers to health literacy compared to other patient groups, and patients with limited health literacy are less likely to ask questions during their medical visits.9,10 Therefore, when obtaining informed consent for images, it is important that measures are taken to ensure that the patient has full knowledge and understanding of what the consent covers, including the extent to which the images will be used and/or shared and whether the patient’s confidentiality and/or anonymity are at risk.

Recommendations—We propose that dermatologists should follow these recommendations:

1. Encourage influential dermatology organizations such as the American Academy of Dermatology to establish standardized consenting procedures for image acquisition and use, including requirements to provide (a) written consent for all patient images and (b) specific details as to where and how the image may be used and/or shared.

2. Ensure that consent terminology is presented at a sixth-grade reading level or below, minimize the use of medical jargon and complex terms, and provide consent documentation in the patient’s preferred language.

3. Allow patients to take the consent document home so they can have additional time to comprehensively review the material or have it reviewed by family or friends.

4. Employ strategies such as teach-back methods and encourage questions to maximize the level of understanding during the consent process.

Clinical Image Storage

Clinical image storage procedures can have an impact on a patient’s health information remaining anonymous and confidential. In a survey evaluating medical photography use among 153 US board-certified dermatologists, 69.1% of respondents reported emailing or texting images between patients and colleagues. Additionally, 30.3% (46/152) reported having patient photographs stored on their personal phone at the time of the survey, and 39.1% (18/46) of those individuals had images that showed identifiable features, such as the patient’s face or a tattoo.11

Although most providers state that their devices are password protected, it cannot be guaranteed that the device and consequently the images remain secure and inaccessible to unauthorized individuals. As sharing and viewing images continue to play an essential role in assessing disease state, progression, treatment response, and inclusion in research, we must establish and encourage clear guidelines for the storage and retention of such images.

Recommendations—We propose that dermatologists should follow these recommendations:

1. Store clinical images exclusively on password-protected devices and in password-protected files.

2. Use work-related cameras or electronic devices rather than personal devices, unless the personal device is being used to upload directly into the patient’s medical record. In such cases, use a HIPAA-compliant electronic medical record mobile application that does not store images on the application or the device itself.

3. Avoid using text-messaging systems or unencrypted email to share identifying images without clear patient consent.

Clinical Image Use

Once a thorough consenting process has been completed, it is crucial that the use and distribution of the clinical image are in accordance with the terms specified in the original consent. With the current state of technologic advancement, widespread social media usage, and constant sharing of information, adherence to these terms can be challenging. For example, an image initially intended for use in an educational presentation at a professional conference can be shared on social media if an audience member captures a photo of it. In another example, a patient may consent to their image being shown on a dermatologic website but that image can be duplicated and shared on other unauthorized sites and locations. This situation can be particularly distressing to patients whose image may include all or most of their face, an intimate area, or other physical features that they did not wish to share widely.

Individuals identifying as Black/African American, Latino/Hispanic, or Asian have been shown to express less comfort with providing permission for images of a nonidentifiable sensitive area to be taken (or obtained) or for use for teaching irrespective of identifiability compared to their White counterparts,12 which may be due to the aforementioned lack of trust in medical providers and the health care system in general, both of which may contribute to concerns with how a clinical image is used and/or shared. Although consent from a patient or the patient’s representative can be granted, we must ensure that the use of these images adheres to the patient’s initial agreement. Ultimately, medical providers, researchers, and other parties involved in acquiring or sharing patient images have both an ethical and legal responsibility to ensure that anonymity, privacy, and confidentiality are preserved to the greatest extent possible.

Recommendations—We propose that dermatologists should follow these recommendations:

1. Display a message on websites containing patient images stating that the sharing of the images outside the established guidelines and intended use is prohibited.

2. Place a watermark on images to discourage unauthorized duplication.

3. Issue explicit instructions to audiences prohibiting the copying or reproducing of any patient images during teaching events or presentations.

Final Thoughts

The use of clinical images is an essential component of dermatologic care, education, and research. Due to the higher demand for diverse and representative images and the dearth of images in the medical literature, many SOC images have been widely disseminated and utilized by dermatologists, raising concerns of the adequacy of informed consent for the storage and use of such material. Therefore, dermatologists should implement streamlined guidelines and consent procedures to ensure a patient’s informed consent is provided with full knowledge of how and where their images might be used and shared. Additional efforts should be made to protect patients’ privacy and unauthorized use of their images. Furthermore, we encourage our leading dermatology organizations to develop expert consensus on best practices for appropriate clinical image consent, storage, and use.

- Alvarado SM, Feng H. Representation of dark skin images of common dermatologic conditions in educational resources: a cross-sectional analysis [published online June 18, 2020]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:1427-1431. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.06.041

- Charrow A, Xia FD, Joyce C, et al. Diversity in dermatology clinical trials: a systematic review. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:193-198. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.4129

- Marroquin NA, Carboni A, Zueger M, et al. Skin of color representation trends in JAAD case reports 2015-2021: content analysis. JMIR Dermatol. 2023;6:e40816. doi:10.2196/40816

- Kim Y, Miller JJ, Hollins LC. Skin of color matters: a call to action. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:E273-E274. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.11.026

- Nanda JK, Marchetti MA. Consent and deidentification of patient images in dermatology journals: observational study. JMIR Dermatol. 2022;5:E37398. doi:10.2196/37398

- US Department of Health and Human Services. Summary of the HIPAA privacy rule. Updated October 19, 2022. Accessed March 15, 2024. https://www.hhs.gov/hipaa/for-professionals/privacy/laws-regulations/index.html

- Quinn SC, Garza MA, Butler J, et al. Improving informed consent with minority participants: results from researcher and community surveys. J Empir Res Hum Res Ethics. 2012;7:44-55. doi:10.1525/jer.2012.7.5.44

- Hadden KB, Prince LY, Moore TD, et al. Improving readability of informed consents for research at an academic medical institution. J Clin Transl Sci. 2017;1:361-365. doi:10.1017/cts.2017.312

- Muvuka B, Combs RM, Ayangeakaa SD, et al. Health literacy in African-American communities: barriers and strategies. Health Lit Res Pract. 2020;4:E138-E143. doi:10.3928/24748307-20200617-01

- Menendez ME, van Hoorn BT, Mackert M, et al. Patients with limited health literacy ask fewer questions during office visits with hand surgeons. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2017;475:1291-1297. doi:10.1007/s11999-016-5140-5

- Milam EC, Leger MC. Use of medical photography among dermatologists: a nationwide online survey study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:1804-1809. doi:10.1111/jdv.14839

- Leger MC, Wu T, Haimovic A, et al. Patient perspectives on medical photography in dermatology. Dermatol Surg. 2014;40:1028-1037. doi:10.1097/01.DSS.0000452632.22081.79

- Alvarado SM, Feng H. Representation of dark skin images of common dermatologic conditions in educational resources: a cross-sectional analysis [published online June 18, 2020]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:1427-1431. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.06.041

- Charrow A, Xia FD, Joyce C, et al. Diversity in dermatology clinical trials: a systematic review. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:193-198. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.4129

- Marroquin NA, Carboni A, Zueger M, et al. Skin of color representation trends in JAAD case reports 2015-2021: content analysis. JMIR Dermatol. 2023;6:e40816. doi:10.2196/40816

- Kim Y, Miller JJ, Hollins LC. Skin of color matters: a call to action. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:E273-E274. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.11.026

- Nanda JK, Marchetti MA. Consent and deidentification of patient images in dermatology journals: observational study. JMIR Dermatol. 2022;5:E37398. doi:10.2196/37398

- US Department of Health and Human Services. Summary of the HIPAA privacy rule. Updated October 19, 2022. Accessed March 15, 2024. https://www.hhs.gov/hipaa/for-professionals/privacy/laws-regulations/index.html

- Quinn SC, Garza MA, Butler J, et al. Improving informed consent with minority participants: results from researcher and community surveys. J Empir Res Hum Res Ethics. 2012;7:44-55. doi:10.1525/jer.2012.7.5.44

- Hadden KB, Prince LY, Moore TD, et al. Improving readability of informed consents for research at an academic medical institution. J Clin Transl Sci. 2017;1:361-365. doi:10.1017/cts.2017.312

- Muvuka B, Combs RM, Ayangeakaa SD, et al. Health literacy in African-American communities: barriers and strategies. Health Lit Res Pract. 2020;4:E138-E143. doi:10.3928/24748307-20200617-01

- Menendez ME, van Hoorn BT, Mackert M, et al. Patients with limited health literacy ask fewer questions during office visits with hand surgeons. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2017;475:1291-1297. doi:10.1007/s11999-016-5140-5

- Milam EC, Leger MC. Use of medical photography among dermatologists: a nationwide online survey study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:1804-1809. doi:10.1111/jdv.14839

- Leger MC, Wu T, Haimovic A, et al. Patient perspectives on medical photography in dermatology. Dermatol Surg. 2014;40:1028-1037. doi:10.1097/01.DSS.0000452632.22081.79

Dupilumab-Induced Facial Flushing After Alcohol Consumption

Dupilumab is a fully humanized monoclonal antibody to the α subunit of the IL-4 receptor that inhibits the action of helper T cell (TH2)–type cytokines IL-4 and IL-13. Dupilumab was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2017 for the treatment of moderate to severe atopic dermatitis (AD). We report 2 patients with AD who were treated with dupilumab and subsequently developed facial flushing after consuming alcohol.

Case Report

Patient 1

A 24-year-old woman presented to the dermatology clinic with a lifelong history of moderate to severe AD. She had a medical history of asthma and seasonal allergies, which were treated with fexofenadine and an inhaler, as needed. The patient had an affected body surface area of approximately 70% and had achieved only partial relief with topical corticosteroids and topical calcineurin inhibitors.

Because her disease was severe, the patient was started on dupilumab at FDA-approved dosing for AD: a 600-mg subcutaneous (SC) loading dose, followed by 300 mg SC every 2 weeks. She reported rapid skin clearance within 2 weeks of the start of treatment. Her course was complicated by mild head and neck dermatitis.

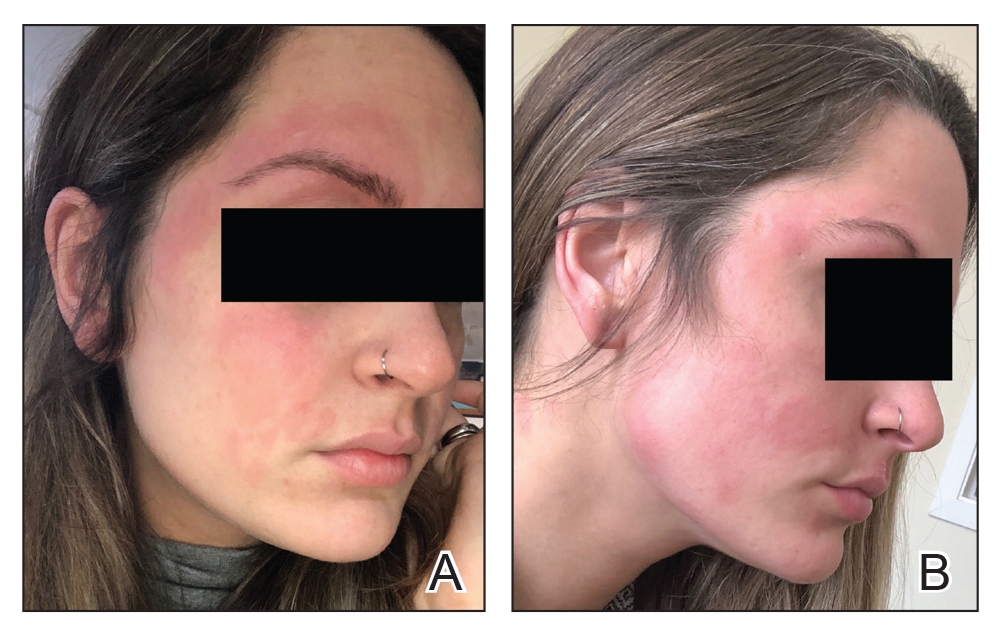

Seven months after starting treatment, the patient began to acutely experience erythema and warmth over the entire face that was triggered by drinking alcohol (Figure). Before starting dupilumab, she had consumed alcohol on multiple occasions without a flushing effect. This new finding was distinguishable from her facial dermatitis. Onset was within a few minutes after drinking alcohol; flushing self-resolved in 15 to 30 minutes. Although diffuse, erythema and warmth were concentrated around the jawline, eyebrows, and ears and occurred every time the patient drank alcohol. Moreover, she reported that consumption of hard (ie, distilled) liquor, specifically tequila, caused a more severe presentation. She denied other symptoms associated with dupilumab.

Patient 2

A 32-year-old man presented to the dermatology clinic with a 10-year history of moderate to severe AD. He had a medical history of asthma (treated with albuterol, montelukast, and fluticasone); allergic rhinitis; and severe environmental allergies, including sensitivity to dust mites, dogs, trees, and grass.

For AD, the patient had been treated with topical corticosteroids and the Goeckerman regimen (a combination of phototherapy and crude coal tar). He experienced only partial relief with topical corticosteroids; the Goeckerman regimen cleared his skin, but he had quick recurrence after approximately 1 month. Given his work schedule, the patient was unable to resume phototherapy.

Because of symptoms related to the patient’s severe allergies, his allergist prescribed dupilumab: a 600-mg SC loading dose, followed by 300 mg SC every 2 weeks. The patient reported near-complete resolution of AD symptoms approximately 2 months after initiating treatment. He reported a few episodes of mild conjunctivitis that self-resolved after the first month of treatment.

Three weeks after initiating dupilumab, the patient noticed new-onset facial flushing in response to consuming alcohol. He described flushing as sudden immediate redness and warmth concentrated around the forehead, eyes, and cheeks. He reported that flushing was worse with hard liquor than with beer. Flushing would slowly subside over approximately 30 minutes despite continued alcohol consumption.

Comment

Two other single-patient case reports have discussed similar findings of alcohol-induced flushing associated with dupilumab.1,2 Both of those patients—a 19-year-old woman and a 26-year-old woman—had not experienced flushing before beginning treatment with dupilumab for AD. Both experienced onset of facial flushing months after beginning dupilumab even though both had consumed alcohol before starting dupilumab, similar to the cases presented here. One patient had a history of asthma; the other had a history of seasonal and environmental allergies.

Possible Mechanism of Action

Acute alcohol ingestion causes dermal vasodilation of the skin (ie, flushing).3 A proposed mechanism is that flushing results from direct action on central vascular-control mechanisms. This theory results from observations that individuals with quadriplegia lack notable ethanol-induced vasodilation, suggesting that ethanol has a central neural site of action.Although some research has indicated that ethanol might induce these effects by altering the action of certain hormones (eg, angiotensin, vasopressin, and catecholamines), the precise mechanism by which ethanol alters vascular function in humans remains unexplained.3

Deficiencies in alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH), aldehyde dehydrogenase 2, and certain cytochrome P450 enzymes also might contribute to facial flushing. People of Asian, especially East Asian, descent often respond to an acute dose of ethanol with symptoms of facial flushing—predominantly the result of an elevated blood level of acetaldehyde caused by an inherited deficiency of aldehyde dehydrogenase 2,4 which is downstream from ADH in the metabolic pathway of alcohol. The major enzyme system responsible for metabolism of ethanol is ADH; however, the cytochrome P450–dependent ethanol-oxidizing system—including major CYP450 isoforms CYP3A, CYP2C19, CYP2C9, CYP1A2, and CYP2D6, as well as minor CYP450 isoforms, such as CYP2E1— also are involved, to a lesser extent.5

A Role for Dupilumab?

A recent pharmacokinetic study found that dupilumab appears to have little effect on the activity of the major CYP450 isoforms. However, the drug’s effect on ADH and minor CYP450 minor isoforms is unknown. Prior drug-drug interaction studies have shown that certain cytokines and cytokine modulators can markedly influence the expression, stability, and activity of specific CYP450 enzymes.6 For example, IL-6 causes a reduction in messenger RNA for CYP3A4 and, to a lesser extent, for other isoforms.7 Whether dupilumab influences enzymes involved in processing alcohol requires further study.

Conclusion

We describe 2 cases of dupilumab-induced facial flushing after alcohol consumption. The mechanism of this dupilumab-associated flushing is unknown and requires further research.

- Herz S, Petri M, Sondermann W. New alcohol flushing in a patient with atopic dermatitis under therapy with dupilumab. Dermatol Ther. 2019;32:e12762. doi:10.1111/dth.12762

- Igelman SJ, Na C, Simpson EL. Alcohol-induced facial flushing in a patient with atopic dermatitis treated with dupilumab. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;6:139-140. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2019.12.002

- Malpas SC, Robinson BJ, Maling TJ. Mechanism of ethanol-induced vasodilation. J Appl Physiol (1985). 1990;68:731-734. doi:10.1152/jappl.1990.68.2.731

- Brooks PJ, Enoch M-A, Goldman D, et al. The alcohol flushing response: an unrecognized risk factor for esophageal cancer from alcohol consumption. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e50. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000050

- Cederbaum AI. Alcohol metabolism. Clin Liver Dis. 2012;16:667-685. doi:10.1016/j.cld.2012.08.002

- Davis JD, Bansal A, Hassman D, et al. Evaluation of potential disease-mediated drug-drug interaction in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis receiving dupilumab. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2018;104:1146-1154. doi:10.1002/cpt.1058

- Mimura H, Kobayashi K, Xu L, et al. Effects of cytokines on CYP3A4 expression and reversal of the effects by anti-cytokine agents in the three-dimensionally cultured human hepatoma cell line FLC-4. Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 2015;30:105-110. doi:10.1016/j.dmpk.2014.09.004

Dupilumab is a fully humanized monoclonal antibody to the α subunit of the IL-4 receptor that inhibits the action of helper T cell (TH2)–type cytokines IL-4 and IL-13. Dupilumab was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2017 for the treatment of moderate to severe atopic dermatitis (AD). We report 2 patients with AD who were treated with dupilumab and subsequently developed facial flushing after consuming alcohol.

Case Report

Patient 1

A 24-year-old woman presented to the dermatology clinic with a lifelong history of moderate to severe AD. She had a medical history of asthma and seasonal allergies, which were treated with fexofenadine and an inhaler, as needed. The patient had an affected body surface area of approximately 70% and had achieved only partial relief with topical corticosteroids and topical calcineurin inhibitors.

Because her disease was severe, the patient was started on dupilumab at FDA-approved dosing for AD: a 600-mg subcutaneous (SC) loading dose, followed by 300 mg SC every 2 weeks. She reported rapid skin clearance within 2 weeks of the start of treatment. Her course was complicated by mild head and neck dermatitis.

Seven months after starting treatment, the patient began to acutely experience erythema and warmth over the entire face that was triggered by drinking alcohol (Figure). Before starting dupilumab, she had consumed alcohol on multiple occasions without a flushing effect. This new finding was distinguishable from her facial dermatitis. Onset was within a few minutes after drinking alcohol; flushing self-resolved in 15 to 30 minutes. Although diffuse, erythema and warmth were concentrated around the jawline, eyebrows, and ears and occurred every time the patient drank alcohol. Moreover, she reported that consumption of hard (ie, distilled) liquor, specifically tequila, caused a more severe presentation. She denied other symptoms associated with dupilumab.

Patient 2

A 32-year-old man presented to the dermatology clinic with a 10-year history of moderate to severe AD. He had a medical history of asthma (treated with albuterol, montelukast, and fluticasone); allergic rhinitis; and severe environmental allergies, including sensitivity to dust mites, dogs, trees, and grass.

For AD, the patient had been treated with topical corticosteroids and the Goeckerman regimen (a combination of phototherapy and crude coal tar). He experienced only partial relief with topical corticosteroids; the Goeckerman regimen cleared his skin, but he had quick recurrence after approximately 1 month. Given his work schedule, the patient was unable to resume phototherapy.

Because of symptoms related to the patient’s severe allergies, his allergist prescribed dupilumab: a 600-mg SC loading dose, followed by 300 mg SC every 2 weeks. The patient reported near-complete resolution of AD symptoms approximately 2 months after initiating treatment. He reported a few episodes of mild conjunctivitis that self-resolved after the first month of treatment.

Three weeks after initiating dupilumab, the patient noticed new-onset facial flushing in response to consuming alcohol. He described flushing as sudden immediate redness and warmth concentrated around the forehead, eyes, and cheeks. He reported that flushing was worse with hard liquor than with beer. Flushing would slowly subside over approximately 30 minutes despite continued alcohol consumption.

Comment

Two other single-patient case reports have discussed similar findings of alcohol-induced flushing associated with dupilumab.1,2 Both of those patients—a 19-year-old woman and a 26-year-old woman—had not experienced flushing before beginning treatment with dupilumab for AD. Both experienced onset of facial flushing months after beginning dupilumab even though both had consumed alcohol before starting dupilumab, similar to the cases presented here. One patient had a history of asthma; the other had a history of seasonal and environmental allergies.

Possible Mechanism of Action

Acute alcohol ingestion causes dermal vasodilation of the skin (ie, flushing).3 A proposed mechanism is that flushing results from direct action on central vascular-control mechanisms. This theory results from observations that individuals with quadriplegia lack notable ethanol-induced vasodilation, suggesting that ethanol has a central neural site of action.Although some research has indicated that ethanol might induce these effects by altering the action of certain hormones (eg, angiotensin, vasopressin, and catecholamines), the precise mechanism by which ethanol alters vascular function in humans remains unexplained.3

Deficiencies in alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH), aldehyde dehydrogenase 2, and certain cytochrome P450 enzymes also might contribute to facial flushing. People of Asian, especially East Asian, descent often respond to an acute dose of ethanol with symptoms of facial flushing—predominantly the result of an elevated blood level of acetaldehyde caused by an inherited deficiency of aldehyde dehydrogenase 2,4 which is downstream from ADH in the metabolic pathway of alcohol. The major enzyme system responsible for metabolism of ethanol is ADH; however, the cytochrome P450–dependent ethanol-oxidizing system—including major CYP450 isoforms CYP3A, CYP2C19, CYP2C9, CYP1A2, and CYP2D6, as well as minor CYP450 isoforms, such as CYP2E1— also are involved, to a lesser extent.5

A Role for Dupilumab?

A recent pharmacokinetic study found that dupilumab appears to have little effect on the activity of the major CYP450 isoforms. However, the drug’s effect on ADH and minor CYP450 minor isoforms is unknown. Prior drug-drug interaction studies have shown that certain cytokines and cytokine modulators can markedly influence the expression, stability, and activity of specific CYP450 enzymes.6 For example, IL-6 causes a reduction in messenger RNA for CYP3A4 and, to a lesser extent, for other isoforms.7 Whether dupilumab influences enzymes involved in processing alcohol requires further study.

Conclusion

We describe 2 cases of dupilumab-induced facial flushing after alcohol consumption. The mechanism of this dupilumab-associated flushing is unknown and requires further research.

Dupilumab is a fully humanized monoclonal antibody to the α subunit of the IL-4 receptor that inhibits the action of helper T cell (TH2)–type cytokines IL-4 and IL-13. Dupilumab was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2017 for the treatment of moderate to severe atopic dermatitis (AD). We report 2 patients with AD who were treated with dupilumab and subsequently developed facial flushing after consuming alcohol.

Case Report

Patient 1

A 24-year-old woman presented to the dermatology clinic with a lifelong history of moderate to severe AD. She had a medical history of asthma and seasonal allergies, which were treated with fexofenadine and an inhaler, as needed. The patient had an affected body surface area of approximately 70% and had achieved only partial relief with topical corticosteroids and topical calcineurin inhibitors.

Because her disease was severe, the patient was started on dupilumab at FDA-approved dosing for AD: a 600-mg subcutaneous (SC) loading dose, followed by 300 mg SC every 2 weeks. She reported rapid skin clearance within 2 weeks of the start of treatment. Her course was complicated by mild head and neck dermatitis.

Seven months after starting treatment, the patient began to acutely experience erythema and warmth over the entire face that was triggered by drinking alcohol (Figure). Before starting dupilumab, she had consumed alcohol on multiple occasions without a flushing effect. This new finding was distinguishable from her facial dermatitis. Onset was within a few minutes after drinking alcohol; flushing self-resolved in 15 to 30 minutes. Although diffuse, erythema and warmth were concentrated around the jawline, eyebrows, and ears and occurred every time the patient drank alcohol. Moreover, she reported that consumption of hard (ie, distilled) liquor, specifically tequila, caused a more severe presentation. She denied other symptoms associated with dupilumab.

Patient 2

A 32-year-old man presented to the dermatology clinic with a 10-year history of moderate to severe AD. He had a medical history of asthma (treated with albuterol, montelukast, and fluticasone); allergic rhinitis; and severe environmental allergies, including sensitivity to dust mites, dogs, trees, and grass.

For AD, the patient had been treated with topical corticosteroids and the Goeckerman regimen (a combination of phototherapy and crude coal tar). He experienced only partial relief with topical corticosteroids; the Goeckerman regimen cleared his skin, but he had quick recurrence after approximately 1 month. Given his work schedule, the patient was unable to resume phototherapy.

Because of symptoms related to the patient’s severe allergies, his allergist prescribed dupilumab: a 600-mg SC loading dose, followed by 300 mg SC every 2 weeks. The patient reported near-complete resolution of AD symptoms approximately 2 months after initiating treatment. He reported a few episodes of mild conjunctivitis that self-resolved after the first month of treatment.

Three weeks after initiating dupilumab, the patient noticed new-onset facial flushing in response to consuming alcohol. He described flushing as sudden immediate redness and warmth concentrated around the forehead, eyes, and cheeks. He reported that flushing was worse with hard liquor than with beer. Flushing would slowly subside over approximately 30 minutes despite continued alcohol consumption.

Comment

Two other single-patient case reports have discussed similar findings of alcohol-induced flushing associated with dupilumab.1,2 Both of those patients—a 19-year-old woman and a 26-year-old woman—had not experienced flushing before beginning treatment with dupilumab for AD. Both experienced onset of facial flushing months after beginning dupilumab even though both had consumed alcohol before starting dupilumab, similar to the cases presented here. One patient had a history of asthma; the other had a history of seasonal and environmental allergies.

Possible Mechanism of Action

Acute alcohol ingestion causes dermal vasodilation of the skin (ie, flushing).3 A proposed mechanism is that flushing results from direct action on central vascular-control mechanisms. This theory results from observations that individuals with quadriplegia lack notable ethanol-induced vasodilation, suggesting that ethanol has a central neural site of action.Although some research has indicated that ethanol might induce these effects by altering the action of certain hormones (eg, angiotensin, vasopressin, and catecholamines), the precise mechanism by which ethanol alters vascular function in humans remains unexplained.3

Deficiencies in alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH), aldehyde dehydrogenase 2, and certain cytochrome P450 enzymes also might contribute to facial flushing. People of Asian, especially East Asian, descent often respond to an acute dose of ethanol with symptoms of facial flushing—predominantly the result of an elevated blood level of acetaldehyde caused by an inherited deficiency of aldehyde dehydrogenase 2,4 which is downstream from ADH in the metabolic pathway of alcohol. The major enzyme system responsible for metabolism of ethanol is ADH; however, the cytochrome P450–dependent ethanol-oxidizing system—including major CYP450 isoforms CYP3A, CYP2C19, CYP2C9, CYP1A2, and CYP2D6, as well as minor CYP450 isoforms, such as CYP2E1— also are involved, to a lesser extent.5

A Role for Dupilumab?

A recent pharmacokinetic study found that dupilumab appears to have little effect on the activity of the major CYP450 isoforms. However, the drug’s effect on ADH and minor CYP450 minor isoforms is unknown. Prior drug-drug interaction studies have shown that certain cytokines and cytokine modulators can markedly influence the expression, stability, and activity of specific CYP450 enzymes.6 For example, IL-6 causes a reduction in messenger RNA for CYP3A4 and, to a lesser extent, for other isoforms.7 Whether dupilumab influences enzymes involved in processing alcohol requires further study.

Conclusion

We describe 2 cases of dupilumab-induced facial flushing after alcohol consumption. The mechanism of this dupilumab-associated flushing is unknown and requires further research.

- Herz S, Petri M, Sondermann W. New alcohol flushing in a patient with atopic dermatitis under therapy with dupilumab. Dermatol Ther. 2019;32:e12762. doi:10.1111/dth.12762

- Igelman SJ, Na C, Simpson EL. Alcohol-induced facial flushing in a patient with atopic dermatitis treated with dupilumab. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;6:139-140. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2019.12.002

- Malpas SC, Robinson BJ, Maling TJ. Mechanism of ethanol-induced vasodilation. J Appl Physiol (1985). 1990;68:731-734. doi:10.1152/jappl.1990.68.2.731

- Brooks PJ, Enoch M-A, Goldman D, et al. The alcohol flushing response: an unrecognized risk factor for esophageal cancer from alcohol consumption. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e50. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000050

- Cederbaum AI. Alcohol metabolism. Clin Liver Dis. 2012;16:667-685. doi:10.1016/j.cld.2012.08.002

- Davis JD, Bansal A, Hassman D, et al. Evaluation of potential disease-mediated drug-drug interaction in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis receiving dupilumab. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2018;104:1146-1154. doi:10.1002/cpt.1058

- Mimura H, Kobayashi K, Xu L, et al. Effects of cytokines on CYP3A4 expression and reversal of the effects by anti-cytokine agents in the three-dimensionally cultured human hepatoma cell line FLC-4. Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 2015;30:105-110. doi:10.1016/j.dmpk.2014.09.004

- Herz S, Petri M, Sondermann W. New alcohol flushing in a patient with atopic dermatitis under therapy with dupilumab. Dermatol Ther. 2019;32:e12762. doi:10.1111/dth.12762

- Igelman SJ, Na C, Simpson EL. Alcohol-induced facial flushing in a patient with atopic dermatitis treated with dupilumab. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;6:139-140. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2019.12.002

- Malpas SC, Robinson BJ, Maling TJ. Mechanism of ethanol-induced vasodilation. J Appl Physiol (1985). 1990;68:731-734. doi:10.1152/jappl.1990.68.2.731

- Brooks PJ, Enoch M-A, Goldman D, et al. The alcohol flushing response: an unrecognized risk factor for esophageal cancer from alcohol consumption. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e50. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000050

- Cederbaum AI. Alcohol metabolism. Clin Liver Dis. 2012;16:667-685. doi:10.1016/j.cld.2012.08.002

- Davis JD, Bansal A, Hassman D, et al. Evaluation of potential disease-mediated drug-drug interaction in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis receiving dupilumab. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2018;104:1146-1154. doi:10.1002/cpt.1058

- Mimura H, Kobayashi K, Xu L, et al. Effects of cytokines on CYP3A4 expression and reversal of the effects by anti-cytokine agents in the three-dimensionally cultured human hepatoma cell line FLC-4. Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 2015;30:105-110. doi:10.1016/j.dmpk.2014.09.004

Practice Points

- Dupilumab is a fully humanized monoclonal antibody that inhibits the action of IL-4 and IL-13. It was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in 2017 for treatment of moderate to severe atopic dermatitis.

- Facial flushing after alcohol consumption may be an emerging side effect of dupilumab.

- Whether dupilumab influences enzymes involved in processing alcohol requires further study.