User login

TXT2STAYQUIT: Pilot Randomized Trial of Brief Automated Smoking Cessation Texting Intervention for Inpatient Smokers Discharged from the Hospital

Hospitalization requires smokers to quit temporarily and offers healthcare professionals an opportunity to provide cessation treatment.1 However, it is important that encouragement continues after the patient has been discharged from the hospital.2 Studies have shown that text messaging interventions for smoking cessation are efficacious in increasing biochemically confirmed cessation rates at 6-month follow-up.3-5 Utilizing technology such as automated voice calls postdischarge has been shown to increase smoking cessation rates; however, text messaging has not been applied to this population.6 This randomized controlled trial of automated smoking cessation support at discharge, coupled with brief advice among hospital inpatients, aimed to assess whether text messaging is a feasible method for providing smoking cessation support and monitoring smoking status postdischarge.

METHODS

Six hundred fifty-five inpatients accepted cessation counseling, 248 were eligible for study participation (including smoking ≥20 cigarettes in 30 days prior to admission and being willing to make a quit attempt and send and/or receive texts), 158 consented to the study, and 140 were included in the analysis (participant removal from analysis was due to technical difficulties prohibiting the participants from receiving the intervention). Participants received texts via an automated system maintained through the College of Information Sciences and Technology at Pennsylvania State University starting at discharge and continuing for 1 month. Control participants received weekly text message smoking status questions. Intervention participants received weekly smoking status questions in addition to daily smoking cessation tips and had the option to interact with the system for additional support. Quit status was based on self-reported, past-week abstinence 28 days after discharge with subsample biochemical verification via carbon monoxide (CO) reading. Intent-to-treat analysis was utilized, and those who did not complete the follow-up phone call were classified as smokers.7 Power was calculated based on the magnitude of change found in the largest published randomized controlled trial of texts for smoking cessation that reported results using a similar 28-day definition.4 This study had 63% power to detect a difference in 28-day abstinence (measured using past 7-day abstinence) of 28.7% in the intervention group compared with 12.1% in the control group.

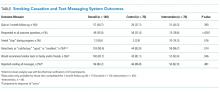

RESULTS

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrates that texting may be a feasible method for following up with hospitalized smokers postdischarge. A majority of participants responded to at least 4 of the 5 outcome questions. Additionally, participants in the intervention group who completed the 1-month follow-up were more likely than those in the control group to rate the texts favorably and to say that they would recommend similar texts to family or friends, indicating that those in the intervention group found the program helpful. However, a majority of participants in the control group also rated the texts favorably and reported they would recommend similar texts to friends or family. This implies that the limited texts provided to the control group may have provided more benefit than researchers previously anticipated.

This study also illustrates the importance of biochemical verification of quit status. Of participants who completed CO verification, 14% did not meet the requirement to be classified as nonsmokers. Other studies of text messaging interventions, including Abroms et al.3 and Free et al.,4 utilized biochemical verification via salivary cotinine and found that of participants who self-reported having quit at follow-up, 24.4% and 28% failed the verification, respectively. In the current study, 10 participants refused verification. It is possible that those who were unwilling to comply may not truly have quit.

While researchers have found that text messaging interventions are efficacious, they have not applied them to an inpatient setting. A limitation is that 62% (n = 407) of the patients counseled were ineligible, and 36% (n = 90) of those who were eligible were not interested in participating. This may indicate that the intervention format is of interest to a limited audience that is already familiar with text messaging. Another limitation is that this was a pilot study conducted with limited power. However, it does provide useful preliminary data for consideration in the development of future text-based smoking cessation interventions.

In conclusion, this study shows that automated text messaging may be a feasible way to monitor smoking status as well as provide smoking cessation support after smokers are discharged from the hospital.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge those in the respiratory care department at Penn State Health Milton S. Hershey Medical Center for their assistance in the recruitment for this study and providing inpatient smoking cessation counseling.

Disclosure

Dr. Foulds has done paid consulting for pharmaceutical companies that are involved in producing smoking cessation medications, including GlaxoSmithKline, Pfizer, Novartis, Johnson and Johnson, and Cypress Bioscience Inc. All other authors declare that they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding

The project described was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through an internal pilot grant (PI: JF) as part of parent grant to Penn State CTSI: Grant UL1 TR000127 and TR002014. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

1. Fiore MC, Jaén CR, Baker TB, et al. Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence: 2008 Update. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2008. PubMed

2. Rigotti NA, Munafo MR, Stead LF. Smoking cessation interventions for hospitalized smokers: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(18):1950-1960. PubMed

3. Abroms LC, Boal AL, Simmens SJ, Mendel JA, Windsor RA. A randomized trial of Text2Quit: a text messaging program for smoking cessation. Am J Prev Med. 2014;47(3):242-250. PubMed

4. Free C, Knight R, Robertson S, et al. Smoking cessation support delivered via mobile phone text messaging (txt2stop): a single-blind, randomised trial. Lancet. 2011;378(9785):49-55. PubMed

5. Spohr SA, Nandy R, Gandhiraj D, Vemulapalli A, Anne S, Walters ST. Efficacy of SMS text message interventions for smoking cessation: a meta-analysis. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2015;56:1-10. PubMed

6. Rigotti NA, Regan S, Levy DE, et al. Sustained care intervention and postdischarge smoking cessation among hospitalized adults: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;312(7):719-728. PubMed

7. Gupta SK. Intention-to-treat concept: a review. Perspect Clin Res. 2011;2(3):109-112. PubMed

Hospitalization requires smokers to quit temporarily and offers healthcare professionals an opportunity to provide cessation treatment.1 However, it is important that encouragement continues after the patient has been discharged from the hospital.2 Studies have shown that text messaging interventions for smoking cessation are efficacious in increasing biochemically confirmed cessation rates at 6-month follow-up.3-5 Utilizing technology such as automated voice calls postdischarge has been shown to increase smoking cessation rates; however, text messaging has not been applied to this population.6 This randomized controlled trial of automated smoking cessation support at discharge, coupled with brief advice among hospital inpatients, aimed to assess whether text messaging is a feasible method for providing smoking cessation support and monitoring smoking status postdischarge.

METHODS

Six hundred fifty-five inpatients accepted cessation counseling, 248 were eligible for study participation (including smoking ≥20 cigarettes in 30 days prior to admission and being willing to make a quit attempt and send and/or receive texts), 158 consented to the study, and 140 were included in the analysis (participant removal from analysis was due to technical difficulties prohibiting the participants from receiving the intervention). Participants received texts via an automated system maintained through the College of Information Sciences and Technology at Pennsylvania State University starting at discharge and continuing for 1 month. Control participants received weekly text message smoking status questions. Intervention participants received weekly smoking status questions in addition to daily smoking cessation tips and had the option to interact with the system for additional support. Quit status was based on self-reported, past-week abstinence 28 days after discharge with subsample biochemical verification via carbon monoxide (CO) reading. Intent-to-treat analysis was utilized, and those who did not complete the follow-up phone call were classified as smokers.7 Power was calculated based on the magnitude of change found in the largest published randomized controlled trial of texts for smoking cessation that reported results using a similar 28-day definition.4 This study had 63% power to detect a difference in 28-day abstinence (measured using past 7-day abstinence) of 28.7% in the intervention group compared with 12.1% in the control group.

RESULTS

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrates that texting may be a feasible method for following up with hospitalized smokers postdischarge. A majority of participants responded to at least 4 of the 5 outcome questions. Additionally, participants in the intervention group who completed the 1-month follow-up were more likely than those in the control group to rate the texts favorably and to say that they would recommend similar texts to family or friends, indicating that those in the intervention group found the program helpful. However, a majority of participants in the control group also rated the texts favorably and reported they would recommend similar texts to friends or family. This implies that the limited texts provided to the control group may have provided more benefit than researchers previously anticipated.

This study also illustrates the importance of biochemical verification of quit status. Of participants who completed CO verification, 14% did not meet the requirement to be classified as nonsmokers. Other studies of text messaging interventions, including Abroms et al.3 and Free et al.,4 utilized biochemical verification via salivary cotinine and found that of participants who self-reported having quit at follow-up, 24.4% and 28% failed the verification, respectively. In the current study, 10 participants refused verification. It is possible that those who were unwilling to comply may not truly have quit.

While researchers have found that text messaging interventions are efficacious, they have not applied them to an inpatient setting. A limitation is that 62% (n = 407) of the patients counseled were ineligible, and 36% (n = 90) of those who were eligible were not interested in participating. This may indicate that the intervention format is of interest to a limited audience that is already familiar with text messaging. Another limitation is that this was a pilot study conducted with limited power. However, it does provide useful preliminary data for consideration in the development of future text-based smoking cessation interventions.

In conclusion, this study shows that automated text messaging may be a feasible way to monitor smoking status as well as provide smoking cessation support after smokers are discharged from the hospital.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge those in the respiratory care department at Penn State Health Milton S. Hershey Medical Center for their assistance in the recruitment for this study and providing inpatient smoking cessation counseling.

Disclosure

Dr. Foulds has done paid consulting for pharmaceutical companies that are involved in producing smoking cessation medications, including GlaxoSmithKline, Pfizer, Novartis, Johnson and Johnson, and Cypress Bioscience Inc. All other authors declare that they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding

The project described was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through an internal pilot grant (PI: JF) as part of parent grant to Penn State CTSI: Grant UL1 TR000127 and TR002014. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Hospitalization requires smokers to quit temporarily and offers healthcare professionals an opportunity to provide cessation treatment.1 However, it is important that encouragement continues after the patient has been discharged from the hospital.2 Studies have shown that text messaging interventions for smoking cessation are efficacious in increasing biochemically confirmed cessation rates at 6-month follow-up.3-5 Utilizing technology such as automated voice calls postdischarge has been shown to increase smoking cessation rates; however, text messaging has not been applied to this population.6 This randomized controlled trial of automated smoking cessation support at discharge, coupled with brief advice among hospital inpatients, aimed to assess whether text messaging is a feasible method for providing smoking cessation support and monitoring smoking status postdischarge.

METHODS

Six hundred fifty-five inpatients accepted cessation counseling, 248 were eligible for study participation (including smoking ≥20 cigarettes in 30 days prior to admission and being willing to make a quit attempt and send and/or receive texts), 158 consented to the study, and 140 were included in the analysis (participant removal from analysis was due to technical difficulties prohibiting the participants from receiving the intervention). Participants received texts via an automated system maintained through the College of Information Sciences and Technology at Pennsylvania State University starting at discharge and continuing for 1 month. Control participants received weekly text message smoking status questions. Intervention participants received weekly smoking status questions in addition to daily smoking cessation tips and had the option to interact with the system for additional support. Quit status was based on self-reported, past-week abstinence 28 days after discharge with subsample biochemical verification via carbon monoxide (CO) reading. Intent-to-treat analysis was utilized, and those who did not complete the follow-up phone call were classified as smokers.7 Power was calculated based on the magnitude of change found in the largest published randomized controlled trial of texts for smoking cessation that reported results using a similar 28-day definition.4 This study had 63% power to detect a difference in 28-day abstinence (measured using past 7-day abstinence) of 28.7% in the intervention group compared with 12.1% in the control group.

RESULTS

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrates that texting may be a feasible method for following up with hospitalized smokers postdischarge. A majority of participants responded to at least 4 of the 5 outcome questions. Additionally, participants in the intervention group who completed the 1-month follow-up were more likely than those in the control group to rate the texts favorably and to say that they would recommend similar texts to family or friends, indicating that those in the intervention group found the program helpful. However, a majority of participants in the control group also rated the texts favorably and reported they would recommend similar texts to friends or family. This implies that the limited texts provided to the control group may have provided more benefit than researchers previously anticipated.

This study also illustrates the importance of biochemical verification of quit status. Of participants who completed CO verification, 14% did not meet the requirement to be classified as nonsmokers. Other studies of text messaging interventions, including Abroms et al.3 and Free et al.,4 utilized biochemical verification via salivary cotinine and found that of participants who self-reported having quit at follow-up, 24.4% and 28% failed the verification, respectively. In the current study, 10 participants refused verification. It is possible that those who were unwilling to comply may not truly have quit.

While researchers have found that text messaging interventions are efficacious, they have not applied them to an inpatient setting. A limitation is that 62% (n = 407) of the patients counseled were ineligible, and 36% (n = 90) of those who were eligible were not interested in participating. This may indicate that the intervention format is of interest to a limited audience that is already familiar with text messaging. Another limitation is that this was a pilot study conducted with limited power. However, it does provide useful preliminary data for consideration in the development of future text-based smoking cessation interventions.

In conclusion, this study shows that automated text messaging may be a feasible way to monitor smoking status as well as provide smoking cessation support after smokers are discharged from the hospital.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge those in the respiratory care department at Penn State Health Milton S. Hershey Medical Center for their assistance in the recruitment for this study and providing inpatient smoking cessation counseling.

Disclosure

Dr. Foulds has done paid consulting for pharmaceutical companies that are involved in producing smoking cessation medications, including GlaxoSmithKline, Pfizer, Novartis, Johnson and Johnson, and Cypress Bioscience Inc. All other authors declare that they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding

The project described was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through an internal pilot grant (PI: JF) as part of parent grant to Penn State CTSI: Grant UL1 TR000127 and TR002014. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

1. Fiore MC, Jaén CR, Baker TB, et al. Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence: 2008 Update. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2008. PubMed

2. Rigotti NA, Munafo MR, Stead LF. Smoking cessation interventions for hospitalized smokers: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(18):1950-1960. PubMed

3. Abroms LC, Boal AL, Simmens SJ, Mendel JA, Windsor RA. A randomized trial of Text2Quit: a text messaging program for smoking cessation. Am J Prev Med. 2014;47(3):242-250. PubMed

4. Free C, Knight R, Robertson S, et al. Smoking cessation support delivered via mobile phone text messaging (txt2stop): a single-blind, randomised trial. Lancet. 2011;378(9785):49-55. PubMed

5. Spohr SA, Nandy R, Gandhiraj D, Vemulapalli A, Anne S, Walters ST. Efficacy of SMS text message interventions for smoking cessation: a meta-analysis. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2015;56:1-10. PubMed

6. Rigotti NA, Regan S, Levy DE, et al. Sustained care intervention and postdischarge smoking cessation among hospitalized adults: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;312(7):719-728. PubMed

7. Gupta SK. Intention-to-treat concept: a review. Perspect Clin Res. 2011;2(3):109-112. PubMed

1. Fiore MC, Jaén CR, Baker TB, et al. Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence: 2008 Update. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2008. PubMed

2. Rigotti NA, Munafo MR, Stead LF. Smoking cessation interventions for hospitalized smokers: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(18):1950-1960. PubMed

3. Abroms LC, Boal AL, Simmens SJ, Mendel JA, Windsor RA. A randomized trial of Text2Quit: a text messaging program for smoking cessation. Am J Prev Med. 2014;47(3):242-250. PubMed

4. Free C, Knight R, Robertson S, et al. Smoking cessation support delivered via mobile phone text messaging (txt2stop): a single-blind, randomised trial. Lancet. 2011;378(9785):49-55. PubMed

5. Spohr SA, Nandy R, Gandhiraj D, Vemulapalli A, Anne S, Walters ST. Efficacy of SMS text message interventions for smoking cessation: a meta-analysis. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2015;56:1-10. PubMed

6. Rigotti NA, Regan S, Levy DE, et al. Sustained care intervention and postdischarge smoking cessation among hospitalized adults: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;312(7):719-728. PubMed

7. Gupta SK. Intention-to-treat concept: a review. Perspect Clin Res. 2011;2(3):109-112. PubMed

© 2018 Society of Hospital Medicine