User login

An Electronic Health Record Tool Designed to Improve Pediatric Hospital Discharge has Low Predictive Utility for Readmissions

As hospitalized children become more medically complex, hospital-to-home care transitions will become increasingly challenging. During a quality improvement (QI) initiative, we developed an electronic tool to improve the quality of our hospital discharge process.

METHODS

Setting

This work was conducted at the Children’s Hospital Colorado as part of a national QI collaborative. The hospital’s EHR is Epic (Verona, Wisconsin). The project was approved as QI by the Children’s Hospital Organizational Research Risk and Quality Improvement Review Panel, precluding review from the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board.

Tool Design, Implementation, and Use

A team of clinicians, nurse–family educators, case managers, social workers, and informatics experts helped design the instrument between 2014 and 2015. In addition to the selected features (number of discharge medications, presence of home health, and language preference), we considered adding the number of consulting specialists but had previously improved our process for scheduling follow-up appointments. Diagnoses were not systematically or discretely documented to be reliably extracted in real time. We excluded known readmission predictor variables (such as length of stay [LOS] and prior hospitalizations) from the initial model to maintain emphasis on the modifiable discharge processes. Additional considerations, such as health literacy and social determinants, were not systematically measured to be operationally usable.

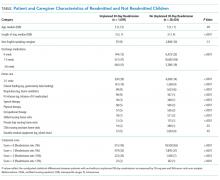

To generate the score, the clinical documentation of home-health orders categorizes children with home care. Each home-care equipment or service category is documented in separate flowsheet rows, allowing for identification of distinct categories (Table). Total parenteral nutrition, intravenous medications, and durable medical equipment and supplies are counted as home care. The number of discharge medications is approximated by inpatient medication orders and finalized as the number of discharge medication orders. The medications include new, historic, and as-needed medications (if included among discharge medication orders).

The electronic score is displayed within the EHR’s Discharge Readiness Report8 and updates automatically as relevant data are entered. The tool displays the individual components and as a composite of 0-3 points. To register a point in each category, a patient needs to exceed (1) the dichotomous discharge medications criterion (ie, ≥6 medications), (2) the dichotomous home-health order criterion (ie, ≥1 home-care order), and (3) to possess documentation of a non-English speaking caregiver. The tool serves as a visual reminder of discharge planning needs during daily coordination rounds attended by clinicians, nursing managers, case managers, and social workers. Case managers use the home-care alert to verify the accuracy of home-care orders.

Evaluation of Predictive Utility for Readmission

We performed a retrospective cohort study on patients aged 0-21 years who were discharged between January 1, 2014 and December 30, 2015. This study was performed to determine the optimal cut points for the continuous variables (discharge medications and home-care orders) and to evaluate the predictive value of the composite score.

Unplanned readmission within 30 days was used as the primary outcome. The index hospitalization was randomly selected for patients with >1 admissions to avoid biasing the results with multiple hospitalizations from individual patients.

Patient characteristics were summarized using percentages for categorical variables and the median and interquartile range (IQR) for continuous variables. We examined bivariate associations for each of the tool’s predictor elements with readmission using Chi-square and Wilcoxon tests

The area under the ROC curve (AUC) was estimated to evaluate the performance of the composite score

RESULTS

Cohort Characteristics

Analysis was restricted to

ROC analysis indicated that dichotomizing number of medications at ≥6 vs. <6 and home health at 0 vs. ≥1 categories maximized the sensitivity and specificity for predicting 30-day unplanned readmissions. In predictive logistic regression analysis, the odds of readmission was significantly higher in children with a composite score of 1 vs. 0 (odds ratio [OR], 1.7; 95% CI 1.5-2) and a score of ≥2 vs. 0 (OR, 4.2; 95% CI, 3.6-4.9). The c statistic for this model was 0.62, and the Brier score was 0.037. Internal validation of the predictive logistic regression model yielded identical results.

DISCUSSION

The instrument’s framework is relatively simple and should reduce barriers to implementation elsewhere. However, this tool was developed for one setting, and the design may require adjustment for other environments. Regional or institutional variation in home-health eligibility or clinical documentation may impact home-care and medication scores. The score may change at discharge if home-health or medication orders are modified late. The tool performs none of the following: measurement of regimen complexity, identification of high-risk medications, distinguishing of new versus preexisting medications/home care, nor measurement of health literacy, parent education, or psychosocial risk. Adding these features might enhance the model. Finally, readmission rates did not rise linearly with each added point. A more sophisticated scoring system (eg, differentially weighting each risk factor) may also improve the performance of the tool.

Despite these limitations, we have implemented a real-time electronic tool with practical potential to improve the discharge process but with low utility for distinguishing readmissions. Additional validation and research is needed to evaluate its impact on hospital discharge quality metrics and family reported outcome measures.

Disclosures

The authors have no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

Funding

This study was supported by an institutional Clinical and Operational Effectiveness and Patient Safety Small Grants Program

1. Holland DE, Conlon PM, Rohlik GM, Gillard KL, Messner PK, Mundy LM. Identifying hospitalized pediatric patients for early discharge planning: a feasibility study. J Pediatr Nurs. 2015;30(3):454-462. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2014.12.011. PubMed

2. Brittan M, Albright K, Cifuentes M, Jimenez-Zambrano A, Kempe A. Parent and provider perspectives on pediatric readmissions: what can we learn about readiness for discharge? Hosp Pediatr. 2015;5(11):559-565. doi: 10.1542/hpeds.2015-0034. PubMed

3. Brittan M FV, Martin S, Moss A, Keller D. Provider feedback: a potential method to reduce readmissions. Hosp Pediatr. 2016;6(11):684-688. PubMed

4. Berry JG, Hall DE, Kuo DZ, et al. Hospital utilization and characteristics of patients experiencing recurrent readmissions within children’s hospitals. JAMA 2011;305(7):682-690. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.122. PubMed

5. Feudtner C, Levin JE, Srivastava R, et al. How well can hospital readmission be predicted in a cohort of hospitalized children? A retrospective, multicenter study. Pediatrics 2009;123(1):286-293. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-3395. PubMed

6. Jurgens V, Spaeder MC, Pavuluri P, Waldman Z. Hospital readmission in children with complex chronic conditions discharged from subacute care. Hosp Pediatr. 2014;4(3):153-158. doi: 10.1542/hpeds.2013-0094. PubMed

7. Karliner LS, Kim SE, Meltzer DO, Auerbach AD. Influence of language barriers on outcomes of hospital care for general medicine inpatients. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(5):276-282. doi: 10.1002/jhm.658. PubMed

8. Tyler A, Boyer A, Martin S, Neiman J, Bakel LA, Brittan M. Development of a discharge readiness report within the electronic health record-A discharge planning tool. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(8):533-539. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2212. PubMed

9. Youden WJ. Index for rating diagnostic tests. Cancer 1950;3(1):32-35. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(1950)3:1<32::AID-CNCR2820030106>3.0.CO;2-3. PubMed

10. Steyerberg EW, Harrell FE, Jr., Borsboom GJ, Eijkemans MJ, Vergouwe Y, Habbema JD. Internal validation of predictive models: efficiency of some procedures for logistic regression analysis. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54(8):774-781. doi: 10.1016/S0895-4356(01)00341-9. PubMed

11. Kansagara D, Englander H, Salanitro A, et al. Risk prediction models for hospital readmission: a systematic review. JAMA 2011;306(15):1688-1698. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1515. PubMed

12. Pepe MS, Janes H, Longton G, Leisenring W, Newcomb P. Limitations of the odds ratio in gauging the performance of a diagnostic, prognostic, or screening marker. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159(9):882-890. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh101. PubMed

13. Coller RJ, Klitzner TS, Lerner CF, Chung PJ. Predictors of 30-day readmission and association with primary care follow-up plans. J Pediatr. 2013;163(4):1027-1033. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.04.013. PubMed

14. Jovanovic M, Radovanovic S, Vukicevic M, Van Poucke S, Delibasic B. Building interpretable predictive models for pediatric hospital readmission using Tree-Lasso logistic regression. Artif Intell Med. 2016;72:12-21. doi: 10.1016/j.artmed.2016.07.003. PubMed

15. Naessens JM, Knoebel E, Johnson M, Branda M. ISQUA16-1722 predicting pediatric readmissions. Int J Qual Health Care. 2016;28(suppl_1):24-25. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzw104.34.

As hospitalized children become more medically complex, hospital-to-home care transitions will become increasingly challenging. During a quality improvement (QI) initiative, we developed an electronic tool to improve the quality of our hospital discharge process.

METHODS

Setting

This work was conducted at the Children’s Hospital Colorado as part of a national QI collaborative. The hospital’s EHR is Epic (Verona, Wisconsin). The project was approved as QI by the Children’s Hospital Organizational Research Risk and Quality Improvement Review Panel, precluding review from the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board.

Tool Design, Implementation, and Use

A team of clinicians, nurse–family educators, case managers, social workers, and informatics experts helped design the instrument between 2014 and 2015. In addition to the selected features (number of discharge medications, presence of home health, and language preference), we considered adding the number of consulting specialists but had previously improved our process for scheduling follow-up appointments. Diagnoses were not systematically or discretely documented to be reliably extracted in real time. We excluded known readmission predictor variables (such as length of stay [LOS] and prior hospitalizations) from the initial model to maintain emphasis on the modifiable discharge processes. Additional considerations, such as health literacy and social determinants, were not systematically measured to be operationally usable.

To generate the score, the clinical documentation of home-health orders categorizes children with home care. Each home-care equipment or service category is documented in separate flowsheet rows, allowing for identification of distinct categories (Table). Total parenteral nutrition, intravenous medications, and durable medical equipment and supplies are counted as home care. The number of discharge medications is approximated by inpatient medication orders and finalized as the number of discharge medication orders. The medications include new, historic, and as-needed medications (if included among discharge medication orders).

The electronic score is displayed within the EHR’s Discharge Readiness Report8 and updates automatically as relevant data are entered. The tool displays the individual components and as a composite of 0-3 points. To register a point in each category, a patient needs to exceed (1) the dichotomous discharge medications criterion (ie, ≥6 medications), (2) the dichotomous home-health order criterion (ie, ≥1 home-care order), and (3) to possess documentation of a non-English speaking caregiver. The tool serves as a visual reminder of discharge planning needs during daily coordination rounds attended by clinicians, nursing managers, case managers, and social workers. Case managers use the home-care alert to verify the accuracy of home-care orders.

Evaluation of Predictive Utility for Readmission

We performed a retrospective cohort study on patients aged 0-21 years who were discharged between January 1, 2014 and December 30, 2015. This study was performed to determine the optimal cut points for the continuous variables (discharge medications and home-care orders) and to evaluate the predictive value of the composite score.

Unplanned readmission within 30 days was used as the primary outcome. The index hospitalization was randomly selected for patients with >1 admissions to avoid biasing the results with multiple hospitalizations from individual patients.

Patient characteristics were summarized using percentages for categorical variables and the median and interquartile range (IQR) for continuous variables. We examined bivariate associations for each of the tool’s predictor elements with readmission using Chi-square and Wilcoxon tests

The area under the ROC curve (AUC) was estimated to evaluate the performance of the composite score

RESULTS

Cohort Characteristics

Analysis was restricted to

ROC analysis indicated that dichotomizing number of medications at ≥6 vs. <6 and home health at 0 vs. ≥1 categories maximized the sensitivity and specificity for predicting 30-day unplanned readmissions. In predictive logistic regression analysis, the odds of readmission was significantly higher in children with a composite score of 1 vs. 0 (odds ratio [OR], 1.7; 95% CI 1.5-2) and a score of ≥2 vs. 0 (OR, 4.2; 95% CI, 3.6-4.9). The c statistic for this model was 0.62, and the Brier score was 0.037. Internal validation of the predictive logistic regression model yielded identical results.

DISCUSSION

The instrument’s framework is relatively simple and should reduce barriers to implementation elsewhere. However, this tool was developed for one setting, and the design may require adjustment for other environments. Regional or institutional variation in home-health eligibility or clinical documentation may impact home-care and medication scores. The score may change at discharge if home-health or medication orders are modified late. The tool performs none of the following: measurement of regimen complexity, identification of high-risk medications, distinguishing of new versus preexisting medications/home care, nor measurement of health literacy, parent education, or psychosocial risk. Adding these features might enhance the model. Finally, readmission rates did not rise linearly with each added point. A more sophisticated scoring system (eg, differentially weighting each risk factor) may also improve the performance of the tool.

Despite these limitations, we have implemented a real-time electronic tool with practical potential to improve the discharge process but with low utility for distinguishing readmissions. Additional validation and research is needed to evaluate its impact on hospital discharge quality metrics and family reported outcome measures.

Disclosures

The authors have no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

Funding

This study was supported by an institutional Clinical and Operational Effectiveness and Patient Safety Small Grants Program

As hospitalized children become more medically complex, hospital-to-home care transitions will become increasingly challenging. During a quality improvement (QI) initiative, we developed an electronic tool to improve the quality of our hospital discharge process.

METHODS

Setting

This work was conducted at the Children’s Hospital Colorado as part of a national QI collaborative. The hospital’s EHR is Epic (Verona, Wisconsin). The project was approved as QI by the Children’s Hospital Organizational Research Risk and Quality Improvement Review Panel, precluding review from the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board.

Tool Design, Implementation, and Use

A team of clinicians, nurse–family educators, case managers, social workers, and informatics experts helped design the instrument between 2014 and 2015. In addition to the selected features (number of discharge medications, presence of home health, and language preference), we considered adding the number of consulting specialists but had previously improved our process for scheduling follow-up appointments. Diagnoses were not systematically or discretely documented to be reliably extracted in real time. We excluded known readmission predictor variables (such as length of stay [LOS] and prior hospitalizations) from the initial model to maintain emphasis on the modifiable discharge processes. Additional considerations, such as health literacy and social determinants, were not systematically measured to be operationally usable.

To generate the score, the clinical documentation of home-health orders categorizes children with home care. Each home-care equipment or service category is documented in separate flowsheet rows, allowing for identification of distinct categories (Table). Total parenteral nutrition, intravenous medications, and durable medical equipment and supplies are counted as home care. The number of discharge medications is approximated by inpatient medication orders and finalized as the number of discharge medication orders. The medications include new, historic, and as-needed medications (if included among discharge medication orders).

The electronic score is displayed within the EHR’s Discharge Readiness Report8 and updates automatically as relevant data are entered. The tool displays the individual components and as a composite of 0-3 points. To register a point in each category, a patient needs to exceed (1) the dichotomous discharge medications criterion (ie, ≥6 medications), (2) the dichotomous home-health order criterion (ie, ≥1 home-care order), and (3) to possess documentation of a non-English speaking caregiver. The tool serves as a visual reminder of discharge planning needs during daily coordination rounds attended by clinicians, nursing managers, case managers, and social workers. Case managers use the home-care alert to verify the accuracy of home-care orders.

Evaluation of Predictive Utility for Readmission

We performed a retrospective cohort study on patients aged 0-21 years who were discharged between January 1, 2014 and December 30, 2015. This study was performed to determine the optimal cut points for the continuous variables (discharge medications and home-care orders) and to evaluate the predictive value of the composite score.

Unplanned readmission within 30 days was used as the primary outcome. The index hospitalization was randomly selected for patients with >1 admissions to avoid biasing the results with multiple hospitalizations from individual patients.

Patient characteristics were summarized using percentages for categorical variables and the median and interquartile range (IQR) for continuous variables. We examined bivariate associations for each of the tool’s predictor elements with readmission using Chi-square and Wilcoxon tests

The area under the ROC curve (AUC) was estimated to evaluate the performance of the composite score

RESULTS

Cohort Characteristics

Analysis was restricted to

ROC analysis indicated that dichotomizing number of medications at ≥6 vs. <6 and home health at 0 vs. ≥1 categories maximized the sensitivity and specificity for predicting 30-day unplanned readmissions. In predictive logistic regression analysis, the odds of readmission was significantly higher in children with a composite score of 1 vs. 0 (odds ratio [OR], 1.7; 95% CI 1.5-2) and a score of ≥2 vs. 0 (OR, 4.2; 95% CI, 3.6-4.9). The c statistic for this model was 0.62, and the Brier score was 0.037. Internal validation of the predictive logistic regression model yielded identical results.

DISCUSSION

The instrument’s framework is relatively simple and should reduce barriers to implementation elsewhere. However, this tool was developed for one setting, and the design may require adjustment for other environments. Regional or institutional variation in home-health eligibility or clinical documentation may impact home-care and medication scores. The score may change at discharge if home-health or medication orders are modified late. The tool performs none of the following: measurement of regimen complexity, identification of high-risk medications, distinguishing of new versus preexisting medications/home care, nor measurement of health literacy, parent education, or psychosocial risk. Adding these features might enhance the model. Finally, readmission rates did not rise linearly with each added point. A more sophisticated scoring system (eg, differentially weighting each risk factor) may also improve the performance of the tool.

Despite these limitations, we have implemented a real-time electronic tool with practical potential to improve the discharge process but with low utility for distinguishing readmissions. Additional validation and research is needed to evaluate its impact on hospital discharge quality metrics and family reported outcome measures.

Disclosures

The authors have no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

Funding

This study was supported by an institutional Clinical and Operational Effectiveness and Patient Safety Small Grants Program

1. Holland DE, Conlon PM, Rohlik GM, Gillard KL, Messner PK, Mundy LM. Identifying hospitalized pediatric patients for early discharge planning: a feasibility study. J Pediatr Nurs. 2015;30(3):454-462. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2014.12.011. PubMed

2. Brittan M, Albright K, Cifuentes M, Jimenez-Zambrano A, Kempe A. Parent and provider perspectives on pediatric readmissions: what can we learn about readiness for discharge? Hosp Pediatr. 2015;5(11):559-565. doi: 10.1542/hpeds.2015-0034. PubMed

3. Brittan M FV, Martin S, Moss A, Keller D. Provider feedback: a potential method to reduce readmissions. Hosp Pediatr. 2016;6(11):684-688. PubMed

4. Berry JG, Hall DE, Kuo DZ, et al. Hospital utilization and characteristics of patients experiencing recurrent readmissions within children’s hospitals. JAMA 2011;305(7):682-690. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.122. PubMed

5. Feudtner C, Levin JE, Srivastava R, et al. How well can hospital readmission be predicted in a cohort of hospitalized children? A retrospective, multicenter study. Pediatrics 2009;123(1):286-293. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-3395. PubMed

6. Jurgens V, Spaeder MC, Pavuluri P, Waldman Z. Hospital readmission in children with complex chronic conditions discharged from subacute care. Hosp Pediatr. 2014;4(3):153-158. doi: 10.1542/hpeds.2013-0094. PubMed

7. Karliner LS, Kim SE, Meltzer DO, Auerbach AD. Influence of language barriers on outcomes of hospital care for general medicine inpatients. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(5):276-282. doi: 10.1002/jhm.658. PubMed

8. Tyler A, Boyer A, Martin S, Neiman J, Bakel LA, Brittan M. Development of a discharge readiness report within the electronic health record-A discharge planning tool. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(8):533-539. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2212. PubMed

9. Youden WJ. Index for rating diagnostic tests. Cancer 1950;3(1):32-35. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(1950)3:1<32::AID-CNCR2820030106>3.0.CO;2-3. PubMed

10. Steyerberg EW, Harrell FE, Jr., Borsboom GJ, Eijkemans MJ, Vergouwe Y, Habbema JD. Internal validation of predictive models: efficiency of some procedures for logistic regression analysis. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54(8):774-781. doi: 10.1016/S0895-4356(01)00341-9. PubMed

11. Kansagara D, Englander H, Salanitro A, et al. Risk prediction models for hospital readmission: a systematic review. JAMA 2011;306(15):1688-1698. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1515. PubMed

12. Pepe MS, Janes H, Longton G, Leisenring W, Newcomb P. Limitations of the odds ratio in gauging the performance of a diagnostic, prognostic, or screening marker. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159(9):882-890. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh101. PubMed

13. Coller RJ, Klitzner TS, Lerner CF, Chung PJ. Predictors of 30-day readmission and association with primary care follow-up plans. J Pediatr. 2013;163(4):1027-1033. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.04.013. PubMed

14. Jovanovic M, Radovanovic S, Vukicevic M, Van Poucke S, Delibasic B. Building interpretable predictive models for pediatric hospital readmission using Tree-Lasso logistic regression. Artif Intell Med. 2016;72:12-21. doi: 10.1016/j.artmed.2016.07.003. PubMed

15. Naessens JM, Knoebel E, Johnson M, Branda M. ISQUA16-1722 predicting pediatric readmissions. Int J Qual Health Care. 2016;28(suppl_1):24-25. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzw104.34.

1. Holland DE, Conlon PM, Rohlik GM, Gillard KL, Messner PK, Mundy LM. Identifying hospitalized pediatric patients for early discharge planning: a feasibility study. J Pediatr Nurs. 2015;30(3):454-462. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2014.12.011. PubMed

2. Brittan M, Albright K, Cifuentes M, Jimenez-Zambrano A, Kempe A. Parent and provider perspectives on pediatric readmissions: what can we learn about readiness for discharge? Hosp Pediatr. 2015;5(11):559-565. doi: 10.1542/hpeds.2015-0034. PubMed

3. Brittan M FV, Martin S, Moss A, Keller D. Provider feedback: a potential method to reduce readmissions. Hosp Pediatr. 2016;6(11):684-688. PubMed

4. Berry JG, Hall DE, Kuo DZ, et al. Hospital utilization and characteristics of patients experiencing recurrent readmissions within children’s hospitals. JAMA 2011;305(7):682-690. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.122. PubMed

5. Feudtner C, Levin JE, Srivastava R, et al. How well can hospital readmission be predicted in a cohort of hospitalized children? A retrospective, multicenter study. Pediatrics 2009;123(1):286-293. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-3395. PubMed

6. Jurgens V, Spaeder MC, Pavuluri P, Waldman Z. Hospital readmission in children with complex chronic conditions discharged from subacute care. Hosp Pediatr. 2014;4(3):153-158. doi: 10.1542/hpeds.2013-0094. PubMed

7. Karliner LS, Kim SE, Meltzer DO, Auerbach AD. Influence of language barriers on outcomes of hospital care for general medicine inpatients. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(5):276-282. doi: 10.1002/jhm.658. PubMed

8. Tyler A, Boyer A, Martin S, Neiman J, Bakel LA, Brittan M. Development of a discharge readiness report within the electronic health record-A discharge planning tool. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(8):533-539. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2212. PubMed

9. Youden WJ. Index for rating diagnostic tests. Cancer 1950;3(1):32-35. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(1950)3:1<32::AID-CNCR2820030106>3.0.CO;2-3. PubMed

10. Steyerberg EW, Harrell FE, Jr., Borsboom GJ, Eijkemans MJ, Vergouwe Y, Habbema JD. Internal validation of predictive models: efficiency of some procedures for logistic regression analysis. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54(8):774-781. doi: 10.1016/S0895-4356(01)00341-9. PubMed

11. Kansagara D, Englander H, Salanitro A, et al. Risk prediction models for hospital readmission: a systematic review. JAMA 2011;306(15):1688-1698. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1515. PubMed

12. Pepe MS, Janes H, Longton G, Leisenring W, Newcomb P. Limitations of the odds ratio in gauging the performance of a diagnostic, prognostic, or screening marker. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159(9):882-890. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh101. PubMed

13. Coller RJ, Klitzner TS, Lerner CF, Chung PJ. Predictors of 30-day readmission and association with primary care follow-up plans. J Pediatr. 2013;163(4):1027-1033. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.04.013. PubMed

14. Jovanovic M, Radovanovic S, Vukicevic M, Van Poucke S, Delibasic B. Building interpretable predictive models for pediatric hospital readmission using Tree-Lasso logistic regression. Artif Intell Med. 2016;72:12-21. doi: 10.1016/j.artmed.2016.07.003. PubMed

15. Naessens JM, Knoebel E, Johnson M, Branda M. ISQUA16-1722 predicting pediatric readmissions. Int J Qual Health Care. 2016;28(suppl_1):24-25. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzw104.34.

© 2018 Society of Hospital Medicine

Discharge Planning Tool in the EHR

According to the American Academy of Pediatrics clinical report on physicians' roles in coordinating care of hospitalized children, there are several important components of hospital discharge planning.[1] Foremost is that discharge planning should begin, and discharge criteria should be set, at the time of hospital admission. This allows for optimal engagement of parents and providers in the effort to adequately prepare patients for the transition to home.

As pediatric inpatients become increasingly complex,[2] adequately preparing families for the transition to home becomes more challenging.[3] There are a myriad of issues to address and the burden of this preparation effort falls on multiple individuals other than the bedside nurse and physician. Large multidisciplinary teams often play a significant role in the discharge of medically complex children.[4] Several challenges may hinder the team's ability to effectively navigate the discharge process such as financial or insurance‐related issues, language differences, or geographic barriers. Patient and family anxieties may also complicate the transition to home.[5]

The challenges of a multidisciplinary approach to discharge planning are further magnified by the limitations of the electronic health record (EHR). The EHR is well designed to record individual encounters, but poorly designed to coordinate longitudinal care across settings.[6] Although multidisciplinary providers may spend significant and well‐intentioned energy to facilitate hospital discharge, their efforts may go unseen or be duplicative.

We developed a discharge readiness report (DRR) for the EHR, an integrated summary of discharge‐related issues, organized into a highly visible and easily accessible report. The development of the discharge planning tool was the first step in a larger quality improvement (QI) initiative aimed at improving the efficiency, effectiveness, and safety of hospital discharge. Our team recognized that improving the flow and visibility of information between disciplines was the first step toward accomplishing this larger aim. Health information technology offers an important opportunity for the improvement of patient safety and care transitions7; therefore, we leveraged the EHR to create an integrated discharge report. We used QI methods to understand our hospital's discharge processes, examined potential pitfalls in interdisciplinary communication, determined relevant information to include in the report, and optimized ways to display the data. To our knowledge, this use of the EHR is novel. The objectives of this article were to describe our team's development and implementation strategies, as well as challenges encountered, in the design of this electronic discharge planning tool.

METHODS

Setting

Children's Hospital Colorado is a 413‐bed freestanding tertiary care teaching hospital with over 13,000 inpatient admissions annually and an average patient length of stay of 5.7 days. We were the first children's hospital to fully implement a single EHR (Epic Systems, Madison, WI) in 2006. This discharge improvement initiative emerged from our hospital's involvement in the Children's Hospital Association Discharge Collaborative between October 2011 and October 2012. We were 1 of 12 participating hospitals and developed several different projects within the framework of the initiative.

Improvement Team

Our multidisciplinary project team included hospitalist physicians, case managers, social workers, respiratory therapists, pharmacists, medical interpreters, process improvement specialists, clinical application specialists whose daily role is management of our hospital's EHR software, and resident liaisons whose daily role is working with residents to facilitate care coordination.

Ethics

The project was determined to be QI work by the Children's Hospital Colorado Organizational Research Risk and Quality Improvement Review Panel.

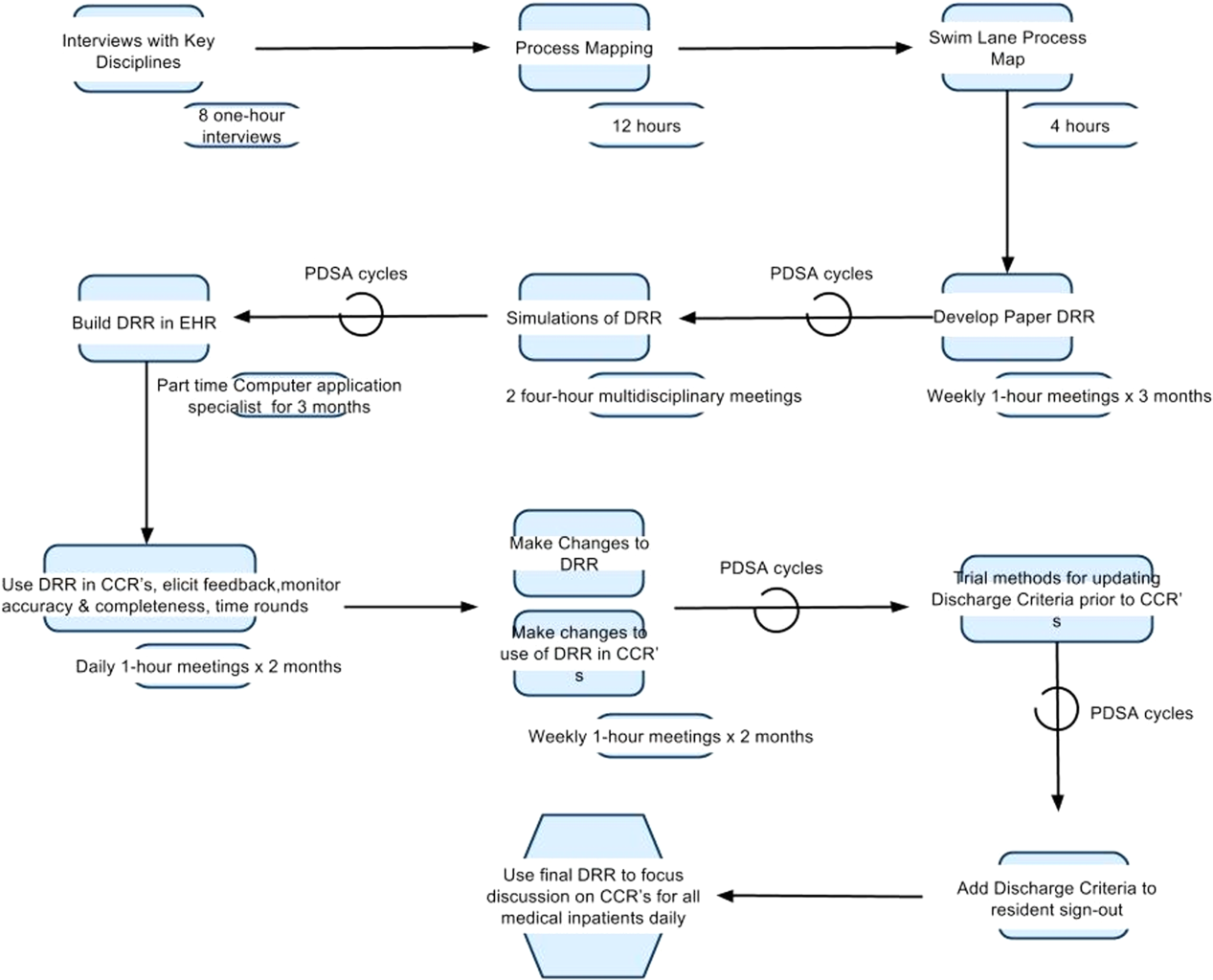

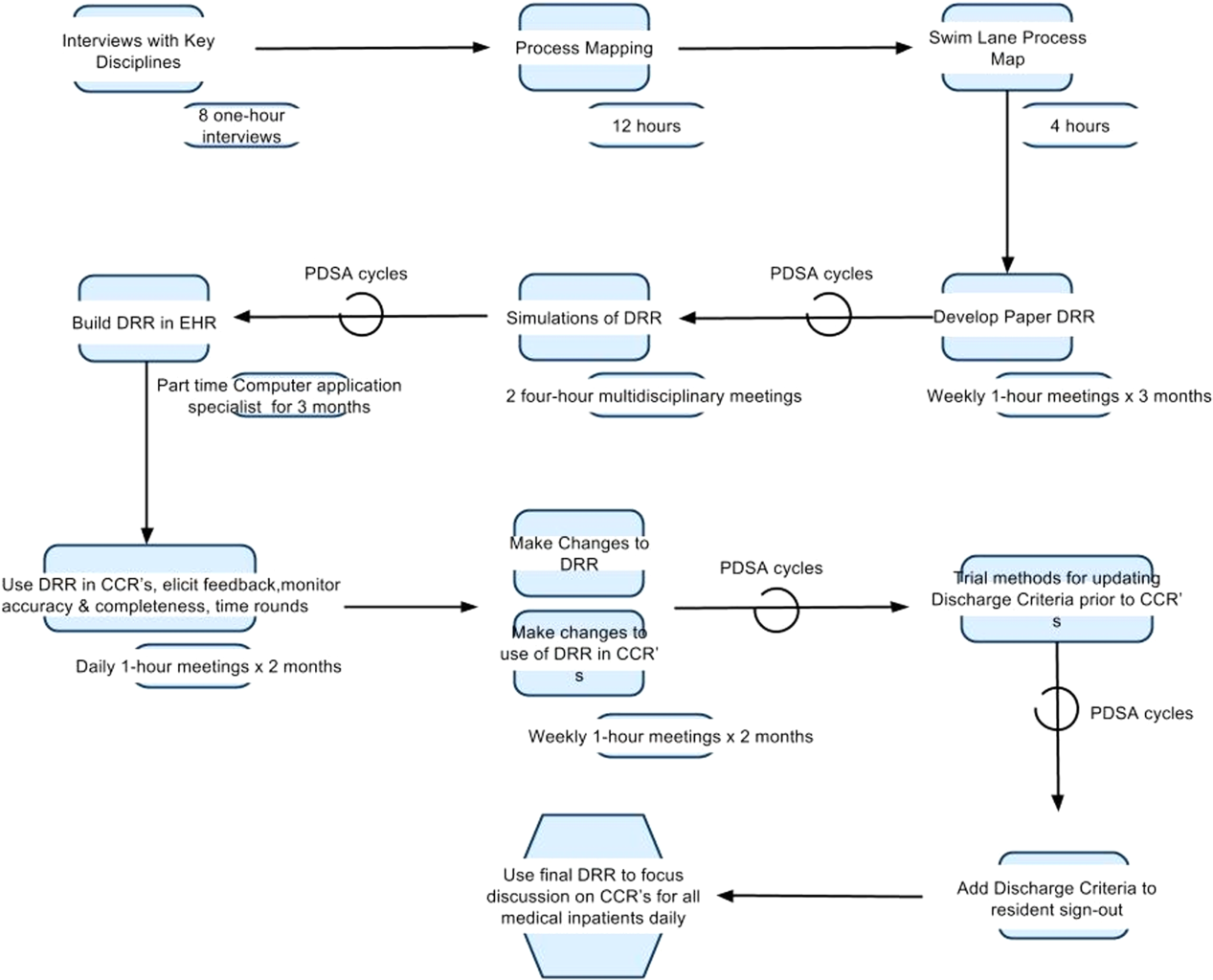

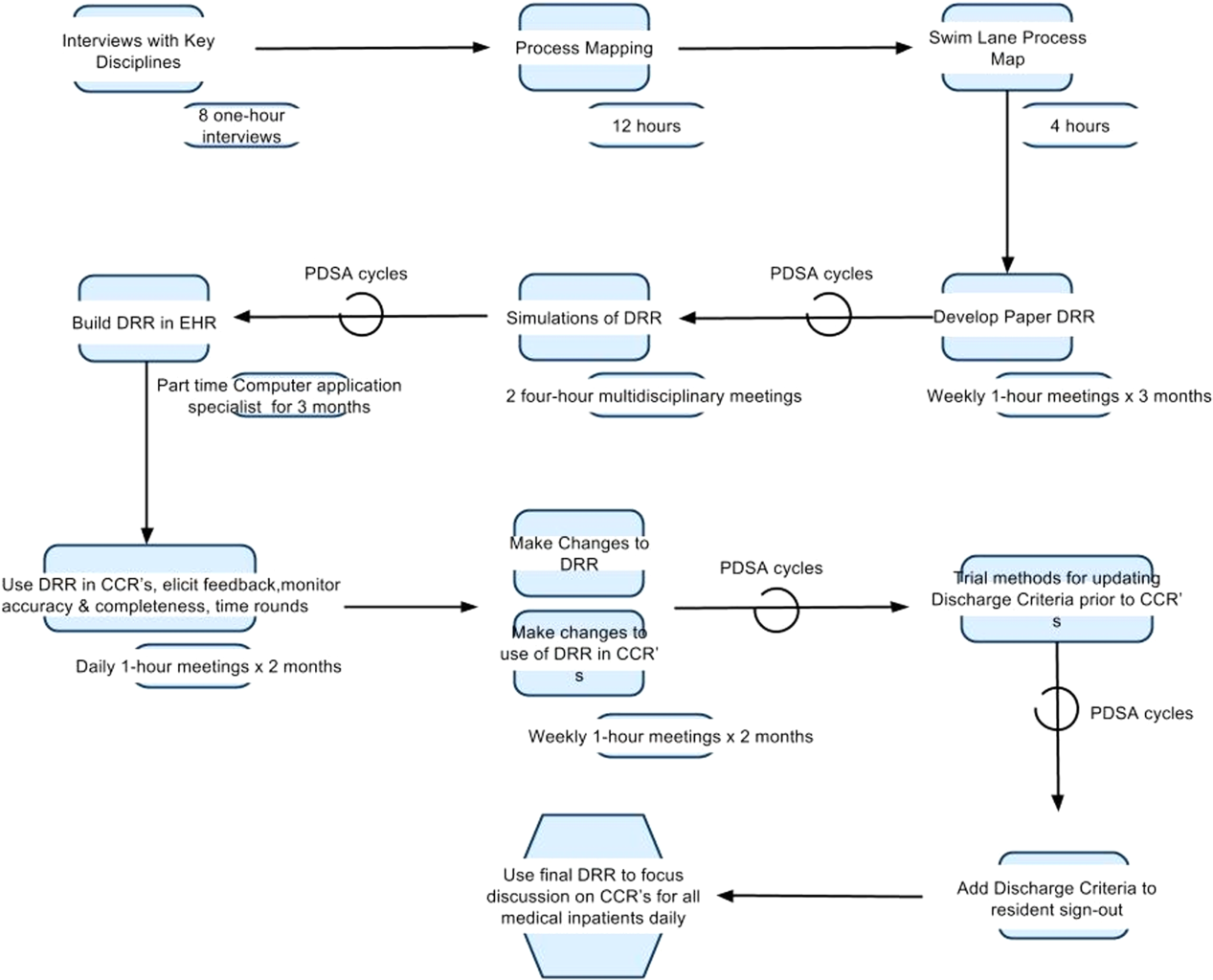

Understanding the Problem

To understand the perspectives of each discipline involved in discharge planning, the lead hospitalist physician and a process improvement specialist interviewed key representatives from each group. Key informant interviews were conducted with hospitalist physicians, case managers, nurses, social workers, resident liaisons, respiratory therapists, pharmacists, medical interpreters, and residents. We inquired about their informational needs, their methods for obtaining relevant information, and whether the information was currently documented in the EHR. We then used process mapping to learn each disciplines' workflow related to discharge planning. Finally, we gathered key stakeholders together for a group session where discharge planning was mapped using the example of a patient admitted with asthma. From this session, we created a detailed multidisciplinary swim lane process map, a flowchart displaying the sequence of events in the overall discharge process grouped visually by placing the events in lanes. Each lane represented a discipline involved in patient discharge, and the arrows between lanes showed how information is passed between the various disciplines. Using this diagram, the team was able to fully understand provider interdependence in discharge planning and longitudinal timing of discharge‐related tasks during the patient's hospitalization.

We learned that: (1) discharge planning is complex, and there were often multiple provider types involved in the discharge of a single patient; (2) communication and coordination between the multitude of providers was often suboptimal; and (3) many of the tasks related to discharge were left to the last minute, resulting in unnecessary delays. Underlying these problems was a clear lack of organized and visible discharge planning information within the EHR.

There were many examples of obscure and siloed discharge processes. Physicians were aware of discharge criteria, but did not document these criteria for others to see. Case management assessments of home health needs were conveyed verbally to other team members, creating the potential for omissions, mistakes, or delays in appropriate home health planning. Social workers helped families to navigate financial hurdles (eg, assistance with payments for prescription medications). However, the presence of financial or insurance problems was not readily apparent to front‐line clinicians making discharge decisions. Other factors with potential significance for discharge planning, such as English‐language proficiency or a family's geographic distance from the hospital, were buried in disparate flow sheets or reports and not available or apparent to all health team members. There were also clear examples of discharge‐related tasks occurring at the end of hospitalization that could easily have been completed earlier in the admission such as identifying a primary care provider (PCP), scheduling follow‐up appointments, and completing work/subhool excuses because of lack of care team awareness that these items were needed.

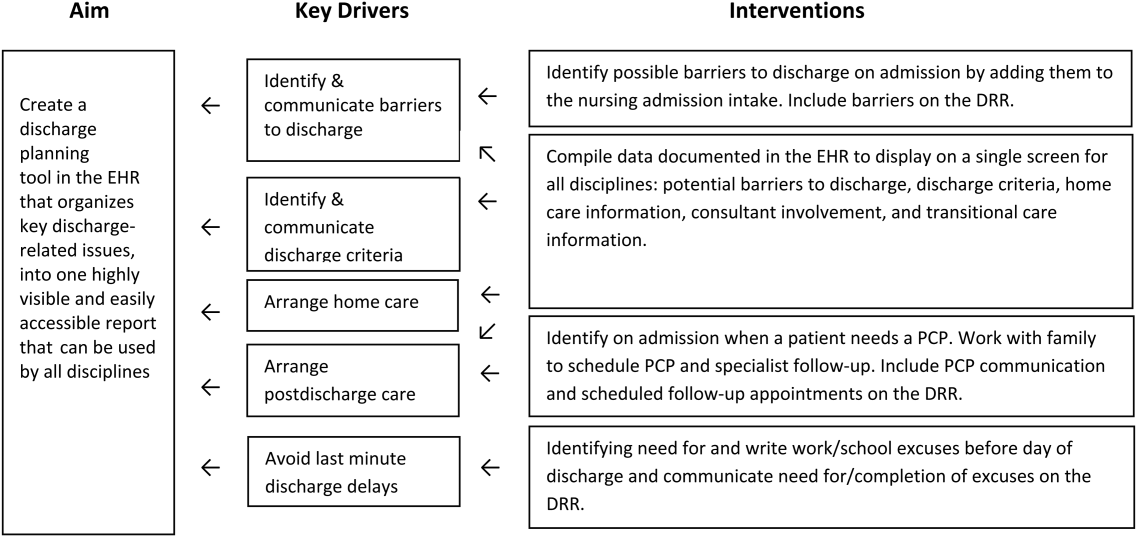

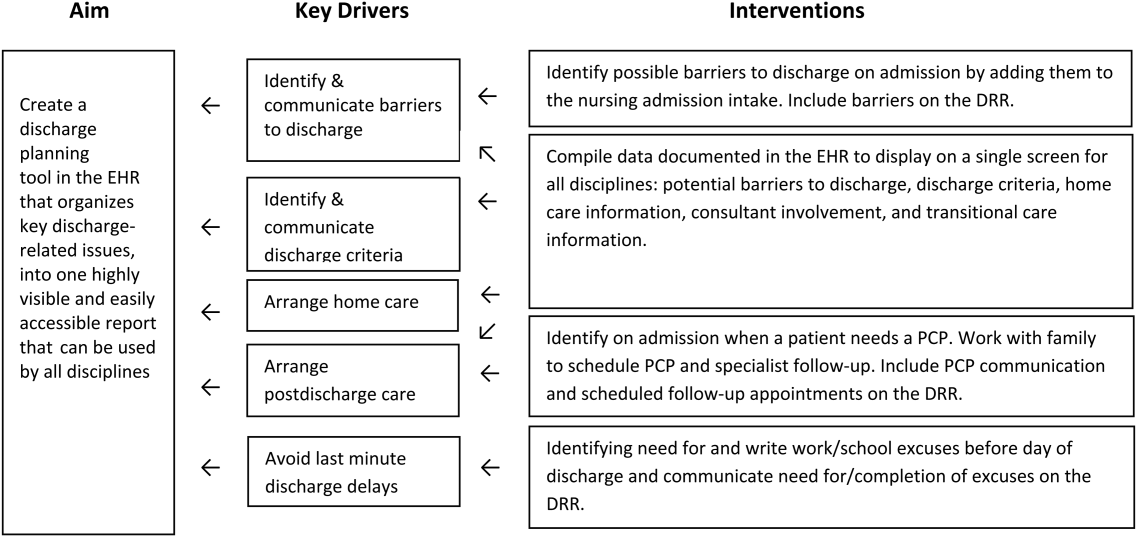

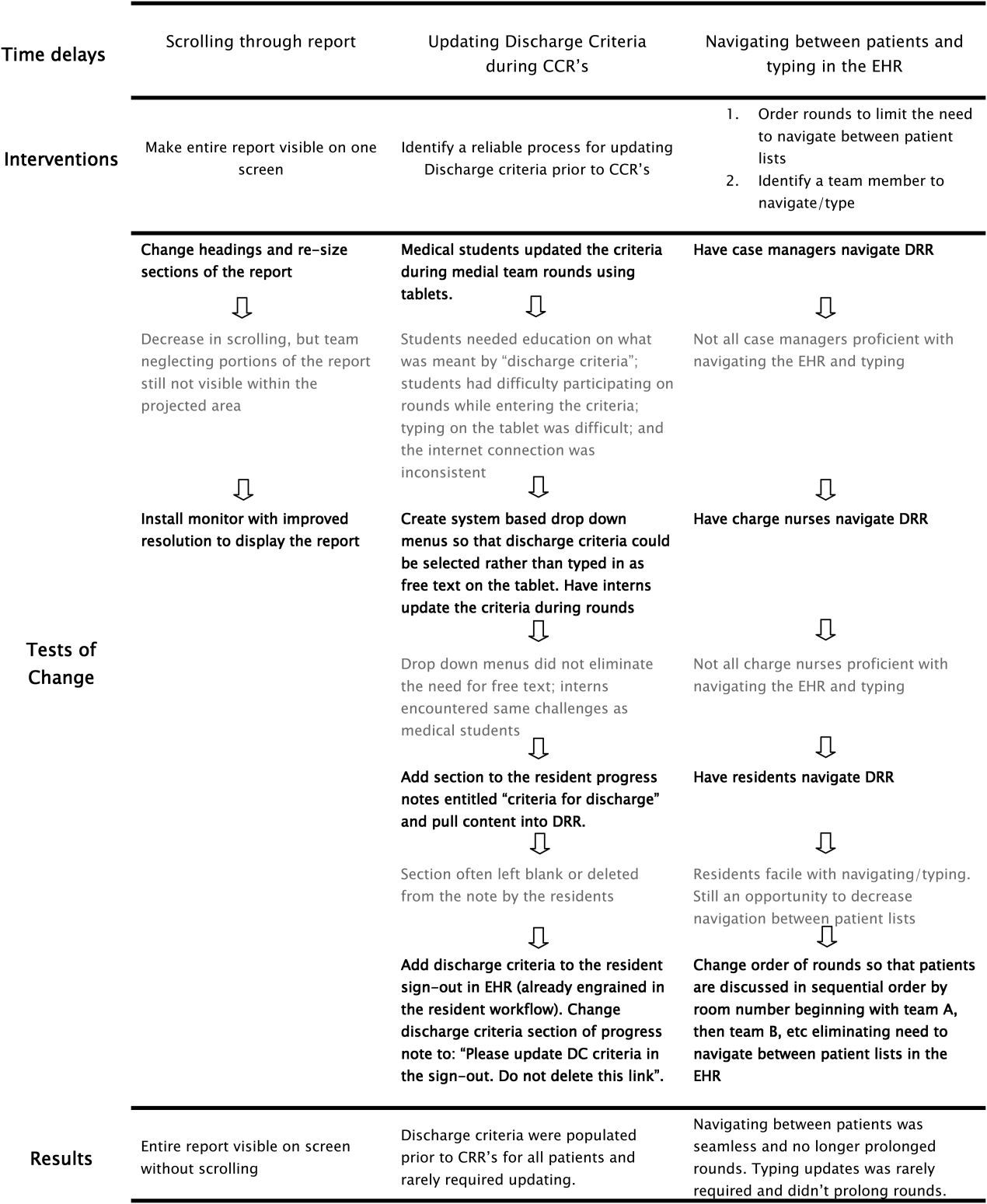

Planning the Intervention

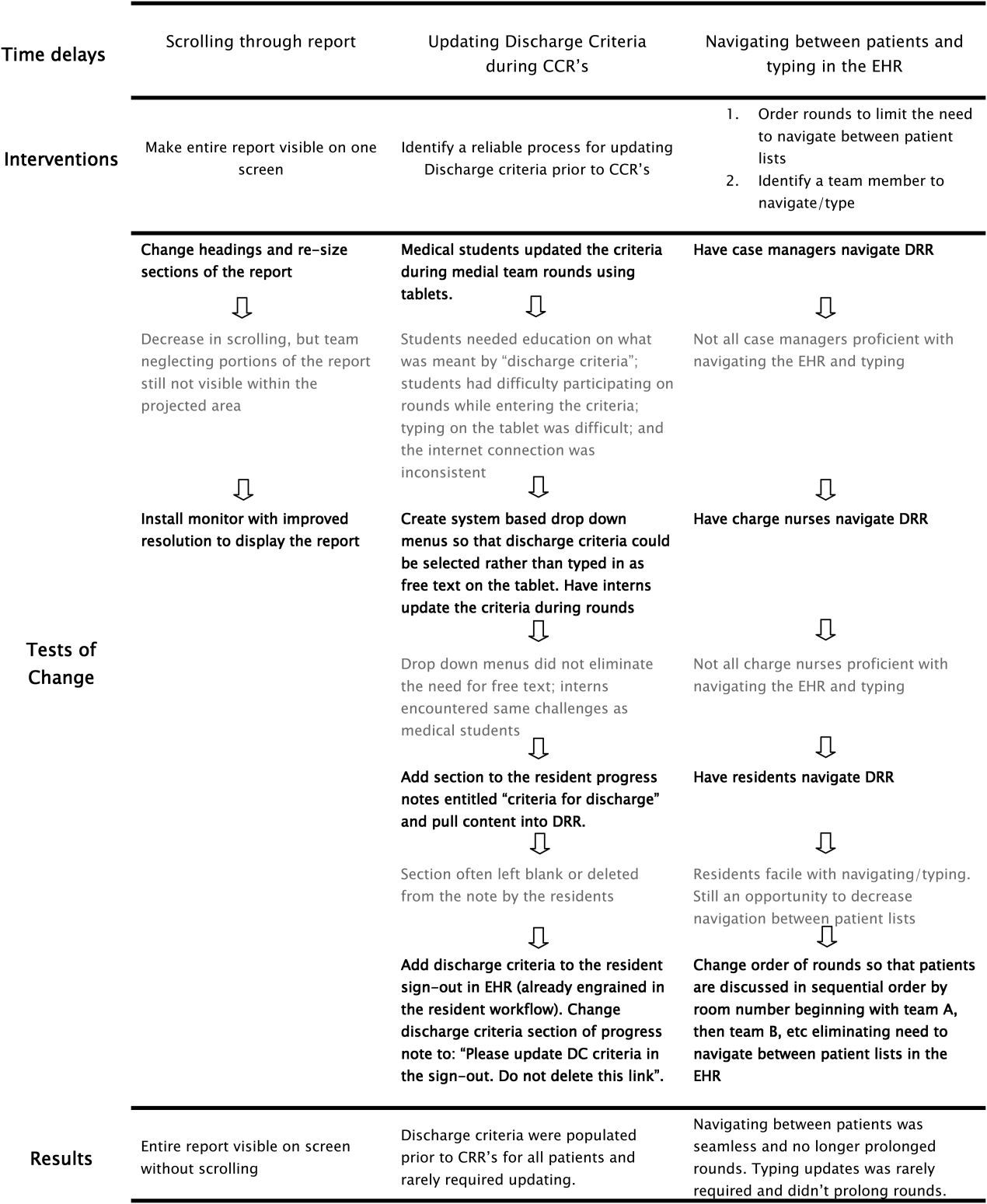

Based on our learning, we developed a key driver diagram (Figure 1). Our aim was to create a DRR that organized important discharge‐related information into 1 easily accessible report. Key drivers that were identified as relevant to the content of the DRR included: barriers to discharge, discharge criteria, home care, postdischarge care, and last minute delays. We also identified secondary drivers related to the design of the DRR. We hypothesized that addressing the secondary drivers would be essential to end user adoption of the tool. The secondary drivers included: accessibility, relevance, ease of updating, automation, and readability.

With the swim lane diagram as well as our primary and secondary drivers in mind, we created a mock DRR on paper. We conducted multiple patient discharge simulations with representatives from all disciplines, walking through each step of a patient hospitalization from registration to discharge. This allowed us to map out how preexisting, yet disparate, EHR data could be channeled into 1 report. A few changes were made to processes involving data collection and documentation to facilitate timely transfer of information to the report. For example, questions addressing potential barriers to discharge and whether a school/work excuse was needed were added to the admission nursing assessment.

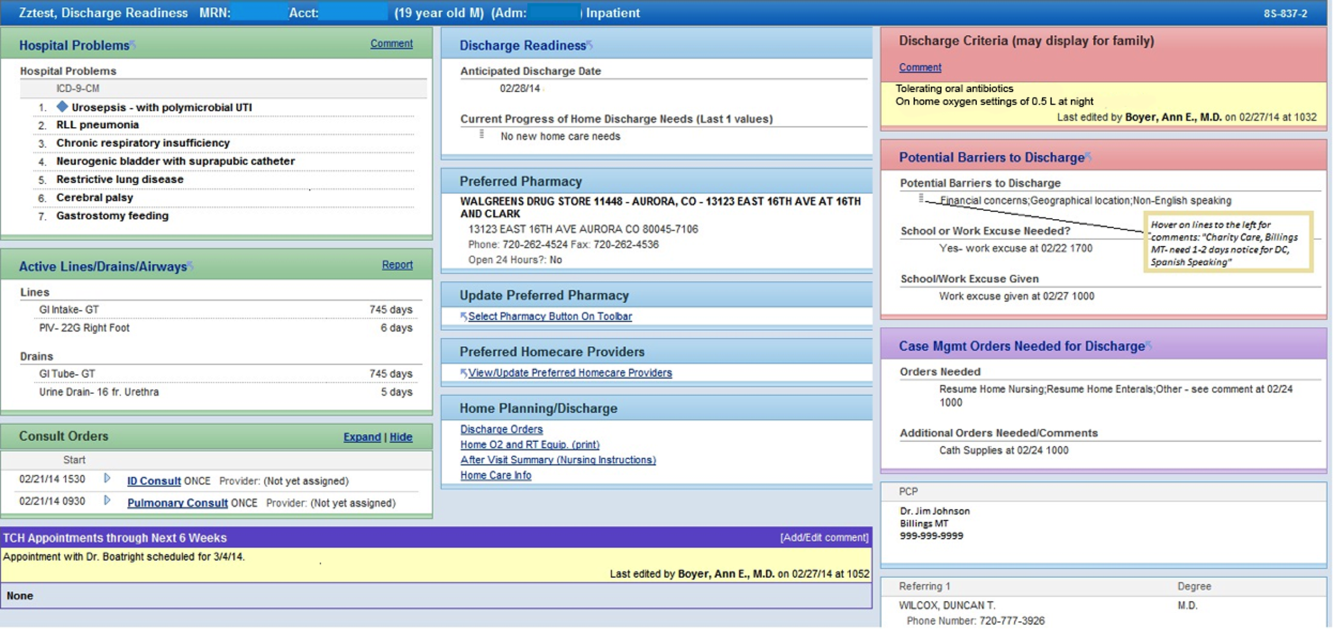

We then moved the paper DRR to the electronic environment. Data elements that were pulled automatically into the report included: potential barriers to discharge collected during nursing intake, case management information on home care needs, discharge criteria entered by resident and attending physicians, PCP, home pharmacy, follow‐up appointments, school/work excuse information gathered by resident liaisons, and active patient problems drawn from the problem list section. These data were organized into 4 distinct domains within the final DRR: potential barriers, transitional care, home care, and discharge criteria (Table 1).

| Discharge Readiness Report Domain | Example Content |

|---|---|

| |

| Potential barriers to discharge | Geographic location of the family, whether patient lives in more than 1 household, primary spoken language, financial or insurance concern, and need for work/subhool excuses |

| Transitional care | PCP and home pharmacy information, follow‐up ambulatory and imaging appointments, and care team communications with the PCP |

| Home care | Planned discharge date/time and home care needs assessments such as needs for special equipment or skilled home nursing |

| Discharge criteria | Clinical, social, or other care coordination conditions for discharge |

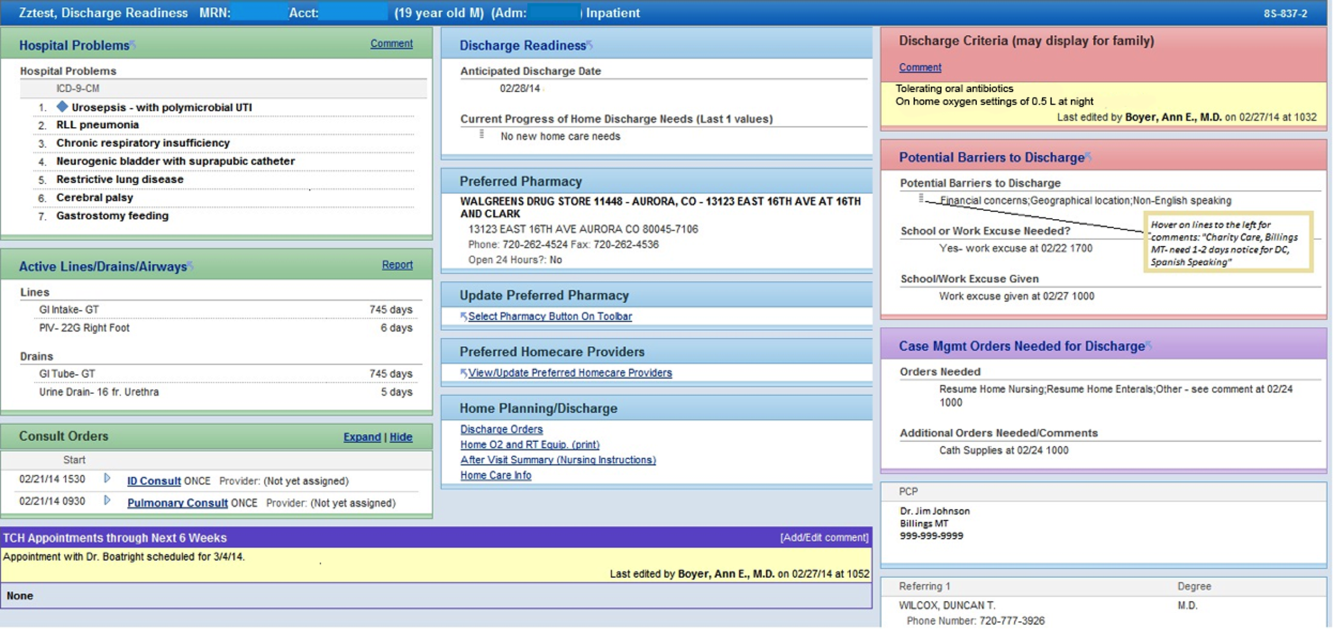

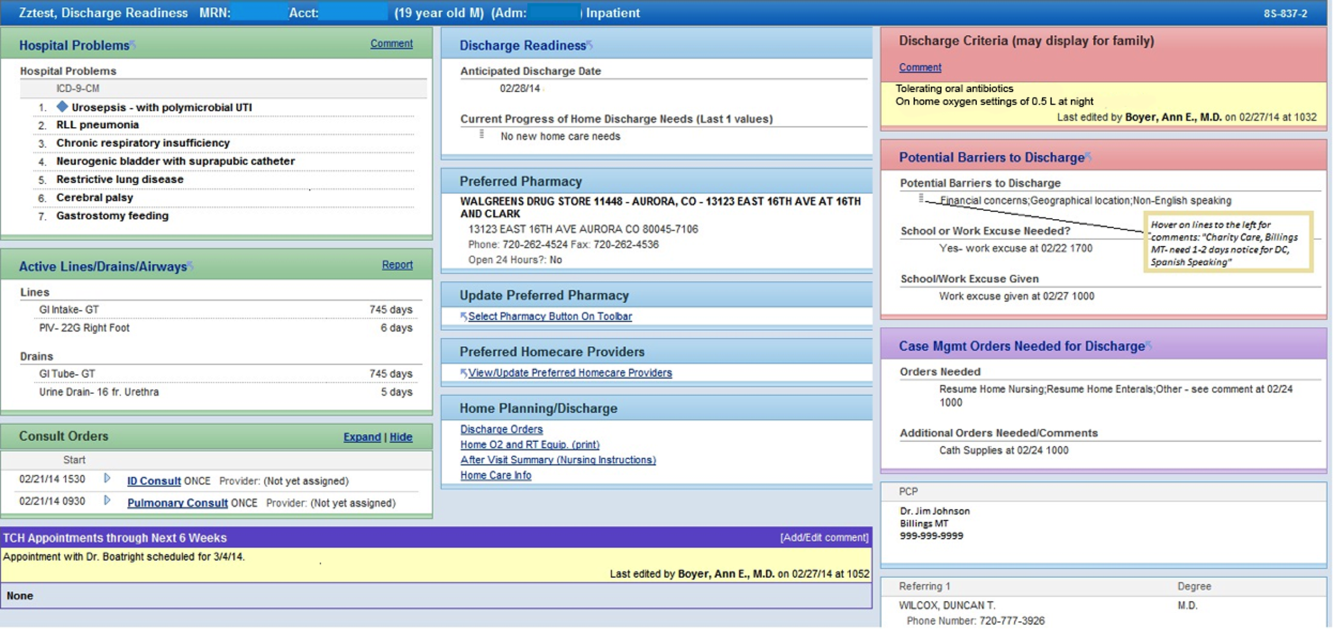

Additional features potentially important to discharge planning were also incorporated into the report based on end user feedback. These included hyperlinks to discharge orders, home oxygen prescriptions, and the after‐visit summary for families, and the patient's home care company (if present). To facilitate discharge and transitional care related communication between the primary team and subspecialty teams, consults involved during the hospitalization were included on the report. As home care arrangements often involve care for active lines and drains, they were added to the report (Figure 2).

Implementation

The report was activated within the EHR in June 2012. The team focused initial promotion and education efforts on medical floors. Education was widely disseminated via email and in‐person presentations.

The DRR was incorporated into daily CCRs for medical patients in July 2012. These multidisciplinary rounds occurred after medical‐team bedside rounds, focusing on care coordination and discharge planning. For each patient discussed, the DRR was projected onto a large screen, allowing all team members to view and discuss relevant discharge information. A process improvement (PI) specialist attended CCRs daily for several months, educating participants and monitoring use of the DRR. The PI specialist solicited feedback on ways to improve the DRR, and timed rounds to measure whether use of the DRR prolonged CCRs.

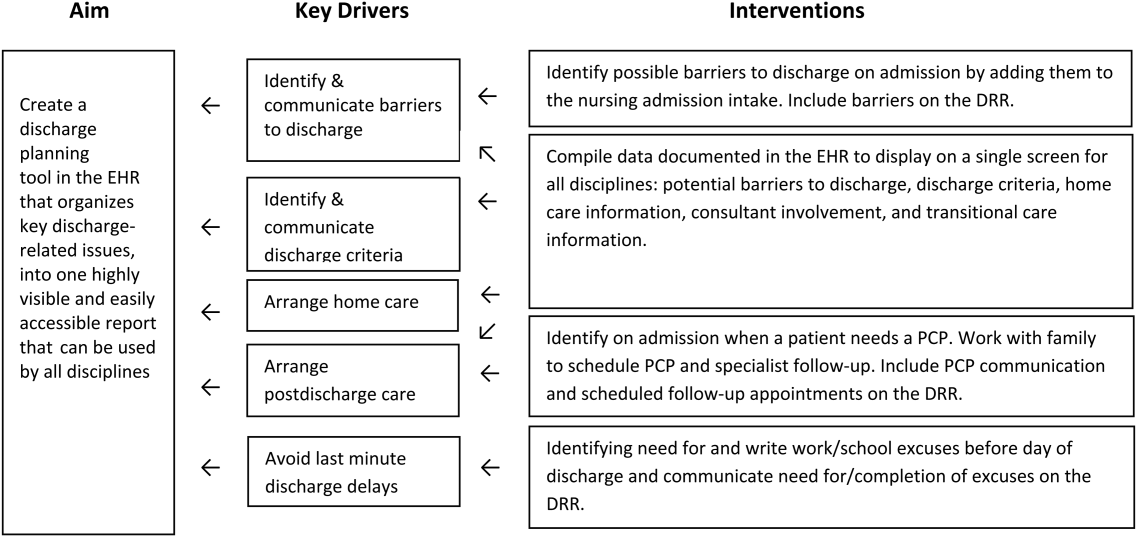

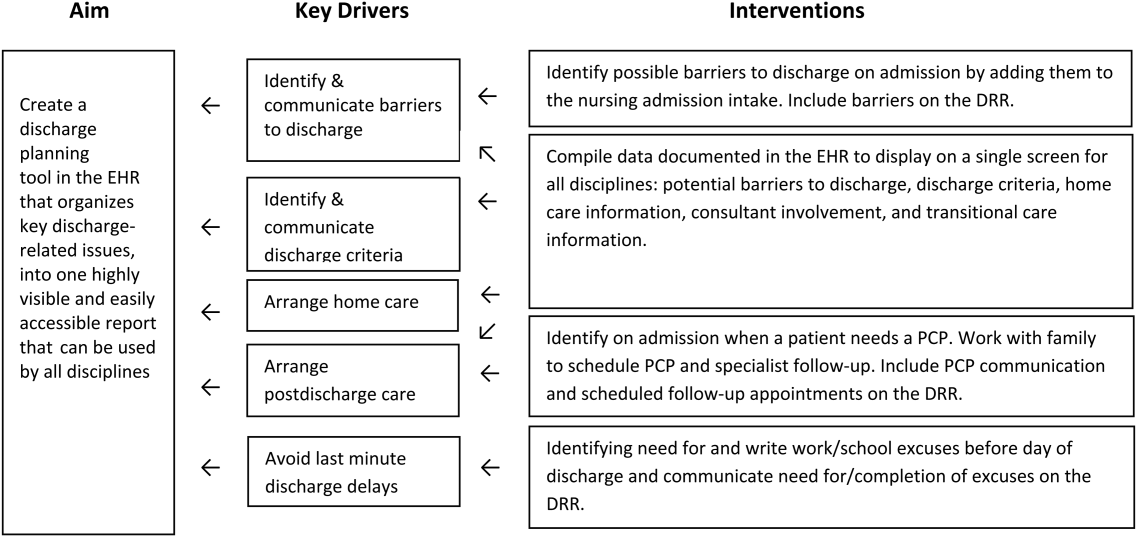

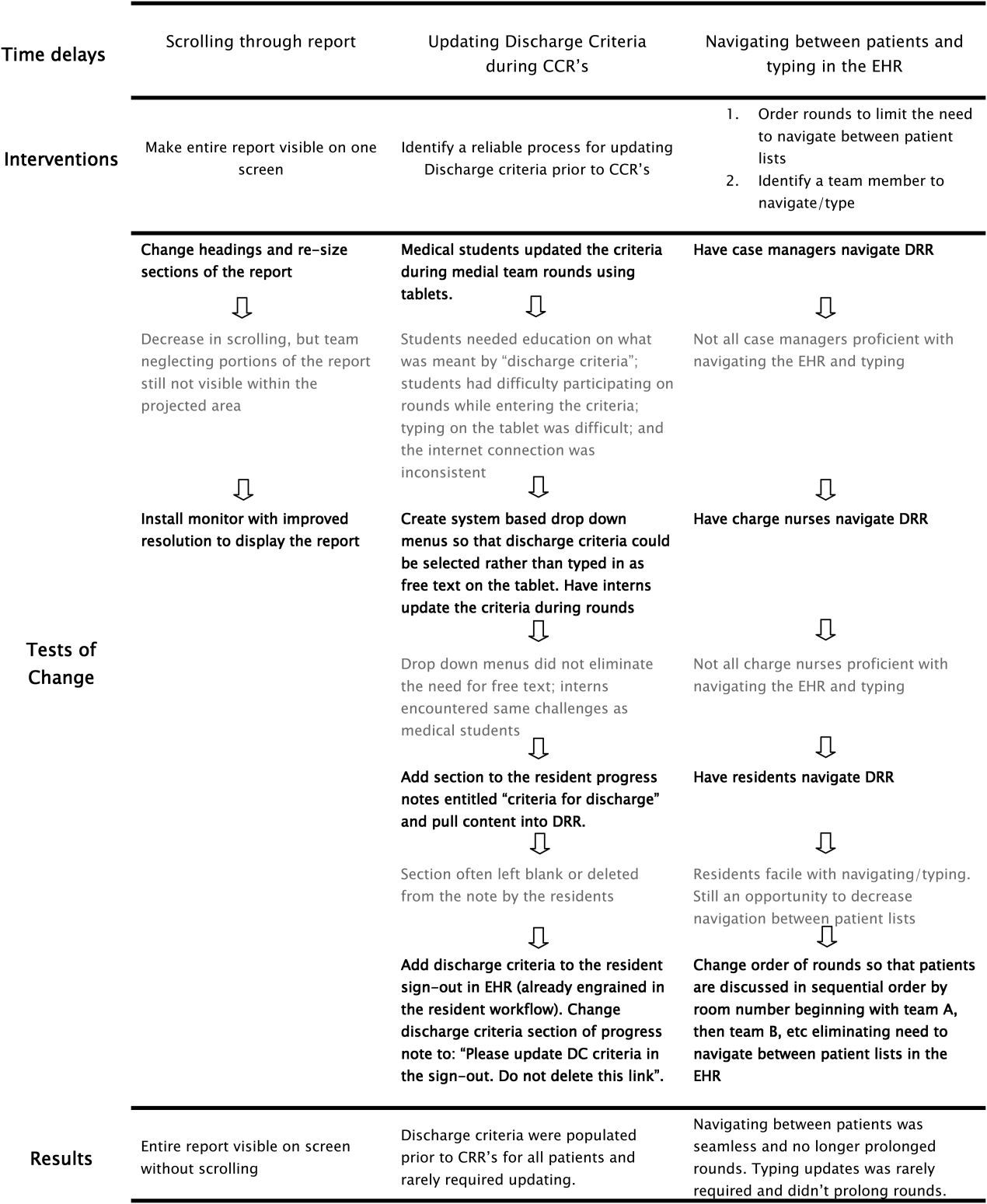

In the first weeks postimplementation, the use of the DRR prolonged rounds by as much as 1 minute per patient. Based on direct observation, the team focused interventions on barriers to the efficient use of the report during CCRs including: the need to scroll through the report, which was not visible on 1 screen; the need to navigate between patients; the need to quickly update the report based on discussion; and the need to update discharge criteria (Figure 3).

RESULTS

Creation of the final DRR required significant time and effort and was the culmination of a uniquely collaborative effort between clinicians, ancillary staff, and information technology specialists (Figure 4). The report is used consistently for all general medical and medical subspecialty patients during CCRs. After interventions were implemented to improve the efficiency of using the DRR during CCRs, the use of the DRR did not prolong CCRs. Members of the care team acknowledge that all sections of the report are populated and accurate. Though end users have commented on their use of the report outside of CCRs, we have not been able to formally measure this.

We have noticed a shift in the focus of discussion since implementation of the DRR. Prior to this initiative, care teams at our institution did not regularly discuss discharge criteria during bedside or CCRs. The phrase discharge criteria has now become part of our shared language.

Informally, the DRR appears to have reduced inefficiency and the potential for communication error. The practice of writing notes on printed patient lists to be used to sign‐out or communicate to other team members not in attendance at CCRs has largely disappeared.

The DRR has proven to be adaptable across patient units, and can be tailored to the specific transitional care needs of a given patient population. At discharge institution, the DRR has been modified for, and has taken on a prominent role in, the discharge planning of highly complex populations such as rehabilitation and ventilated patients.

DISCUSSION

Discharge planning is a multifaceted, multidisciplinary process that should begin at the time of hospital admission. Safe patient transition depends on efficient discharge processes and effective communication across settings.[8] Although not well studied in the inpatient setting, care process variability can result in inefficient patient flow and increased stress among staff.[9] Patients and families may experience confusion, coping difficulties, and increased readmission due to ineffective discharge planning.[10] These potential pitfalls highlight the need for healthcare providers to develop patient‐centered, systematic approaches to improving the discharge process.[11]

To our knowledge, this is the first description of a discharge planning tool for the EHR in the pediatric setting. Our discharge report is centralized, easily accessible by all members of the care team, and includes important patient‐specific discharge‐related information that be used to focus discussion and streamline multidisciplinary discharge planning rounds.

We anticipate that the report will allow the entire healthcare team to function more efficiently, decrease discharge‐related delays and failures based on communication roadblocks, and improve family and caregiver satisfaction with the discharge process. We are currently testing these hypotheses and evaluating several implementation strategies in an ongoing research study. Assuming positive impact, we plan to spread the use of the DRR to all inpatient care areas at our hospital, and potentially to other hospitals.

The limitations of this QI project are consistent with other initiatives to improve care. The challenges we encounter at our freestanding tertiary care teaching hospital with regard to effective discharge planning and multidisciplinary communication may not be generalizable to other nonteaching or community hospitals, and the DRR may not be useful in other settings. Though the report is now a part of our EHR, the most impactful implementation strategies remain to be determined. The report and related changes represent significant diversion from years of deeply ingrained workflows for some providers, and we encountered some resistance from staff during the early stages of implementation. The most important of which was that some team members are uncomfortable with technology and prefer to use paper. Most of this initial resistance was overcome by implementing changes to improve the ease of use of the report (Figure 3). Though input from end users and key stakeholders has been incorporated throughout this initiative, more work is needed to measure end user adoption and satisfaction with the report.

CONCLUSION

High‐quality hospital discharge planning requires an increasingly multidisciplinary approach. The EHR can be leveraged to improve transparency and interdisciplinary communication around the discharge process. An integrated summary of discharge‐related issues, organized into 1 highly visible and easily accessible report in the EHR has the potential to improve care transitions.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

- . Clinical report—physicians' roles in coordinating care of hospitalized children. Pediatrics. 2010;126:829–832.

- , , , , , . Increasing prevalence of medically complex children in US hospitals. Pediatrics. 2010;126:638–646.

- , , . Hospitalist care of the medically complex child. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2005;52:1165–1187, x.

- , . Discharge planning and home care of the technology‐dependent infant. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 1995;24:77–83.

- , , , . Pediatric discharge planning: complications, efficiency, and adequacy. Soc Work Health Care. 1995;22:1–18.

- , , , et al. The current capabilities of health information technology to support care transitions. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2013;2013:1231.

- , , , et al. Provider‐to‐provider electronic communication in the era of meaningful use: a review of the evidence. J Hosp Med. 2013;8:589–597.

- , , , . Promoting effective transitions of care at hospital discharge: a review of key issues for hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2007;2:314–323.

- , , , , . A 5‐year time study analysis of emergency department patient care efficiency. Ann Emerg Med. 1999;34:326–335.

- , , , et al. Quality of discharge practices and patient understanding at an academic medical center. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(18):1715–1722.

- , . Addressing postdischarge adverse events: a neglected area. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2008;34:85–97.

According to the American Academy of Pediatrics clinical report on physicians' roles in coordinating care of hospitalized children, there are several important components of hospital discharge planning.[1] Foremost is that discharge planning should begin, and discharge criteria should be set, at the time of hospital admission. This allows for optimal engagement of parents and providers in the effort to adequately prepare patients for the transition to home.

As pediatric inpatients become increasingly complex,[2] adequately preparing families for the transition to home becomes more challenging.[3] There are a myriad of issues to address and the burden of this preparation effort falls on multiple individuals other than the bedside nurse and physician. Large multidisciplinary teams often play a significant role in the discharge of medically complex children.[4] Several challenges may hinder the team's ability to effectively navigate the discharge process such as financial or insurance‐related issues, language differences, or geographic barriers. Patient and family anxieties may also complicate the transition to home.[5]

The challenges of a multidisciplinary approach to discharge planning are further magnified by the limitations of the electronic health record (EHR). The EHR is well designed to record individual encounters, but poorly designed to coordinate longitudinal care across settings.[6] Although multidisciplinary providers may spend significant and well‐intentioned energy to facilitate hospital discharge, their efforts may go unseen or be duplicative.

We developed a discharge readiness report (DRR) for the EHR, an integrated summary of discharge‐related issues, organized into a highly visible and easily accessible report. The development of the discharge planning tool was the first step in a larger quality improvement (QI) initiative aimed at improving the efficiency, effectiveness, and safety of hospital discharge. Our team recognized that improving the flow and visibility of information between disciplines was the first step toward accomplishing this larger aim. Health information technology offers an important opportunity for the improvement of patient safety and care transitions7; therefore, we leveraged the EHR to create an integrated discharge report. We used QI methods to understand our hospital's discharge processes, examined potential pitfalls in interdisciplinary communication, determined relevant information to include in the report, and optimized ways to display the data. To our knowledge, this use of the EHR is novel. The objectives of this article were to describe our team's development and implementation strategies, as well as challenges encountered, in the design of this electronic discharge planning tool.

METHODS

Setting

Children's Hospital Colorado is a 413‐bed freestanding tertiary care teaching hospital with over 13,000 inpatient admissions annually and an average patient length of stay of 5.7 days. We were the first children's hospital to fully implement a single EHR (Epic Systems, Madison, WI) in 2006. This discharge improvement initiative emerged from our hospital's involvement in the Children's Hospital Association Discharge Collaborative between October 2011 and October 2012. We were 1 of 12 participating hospitals and developed several different projects within the framework of the initiative.

Improvement Team

Our multidisciplinary project team included hospitalist physicians, case managers, social workers, respiratory therapists, pharmacists, medical interpreters, process improvement specialists, clinical application specialists whose daily role is management of our hospital's EHR software, and resident liaisons whose daily role is working with residents to facilitate care coordination.

Ethics

The project was determined to be QI work by the Children's Hospital Colorado Organizational Research Risk and Quality Improvement Review Panel.

Understanding the Problem

To understand the perspectives of each discipline involved in discharge planning, the lead hospitalist physician and a process improvement specialist interviewed key representatives from each group. Key informant interviews were conducted with hospitalist physicians, case managers, nurses, social workers, resident liaisons, respiratory therapists, pharmacists, medical interpreters, and residents. We inquired about their informational needs, their methods for obtaining relevant information, and whether the information was currently documented in the EHR. We then used process mapping to learn each disciplines' workflow related to discharge planning. Finally, we gathered key stakeholders together for a group session where discharge planning was mapped using the example of a patient admitted with asthma. From this session, we created a detailed multidisciplinary swim lane process map, a flowchart displaying the sequence of events in the overall discharge process grouped visually by placing the events in lanes. Each lane represented a discipline involved in patient discharge, and the arrows between lanes showed how information is passed between the various disciplines. Using this diagram, the team was able to fully understand provider interdependence in discharge planning and longitudinal timing of discharge‐related tasks during the patient's hospitalization.

We learned that: (1) discharge planning is complex, and there were often multiple provider types involved in the discharge of a single patient; (2) communication and coordination between the multitude of providers was often suboptimal; and (3) many of the tasks related to discharge were left to the last minute, resulting in unnecessary delays. Underlying these problems was a clear lack of organized and visible discharge planning information within the EHR.

There were many examples of obscure and siloed discharge processes. Physicians were aware of discharge criteria, but did not document these criteria for others to see. Case management assessments of home health needs were conveyed verbally to other team members, creating the potential for omissions, mistakes, or delays in appropriate home health planning. Social workers helped families to navigate financial hurdles (eg, assistance with payments for prescription medications). However, the presence of financial or insurance problems was not readily apparent to front‐line clinicians making discharge decisions. Other factors with potential significance for discharge planning, such as English‐language proficiency or a family's geographic distance from the hospital, were buried in disparate flow sheets or reports and not available or apparent to all health team members. There were also clear examples of discharge‐related tasks occurring at the end of hospitalization that could easily have been completed earlier in the admission such as identifying a primary care provider (PCP), scheduling follow‐up appointments, and completing work/subhool excuses because of lack of care team awareness that these items were needed.

Planning the Intervention

Based on our learning, we developed a key driver diagram (Figure 1). Our aim was to create a DRR that organized important discharge‐related information into 1 easily accessible report. Key drivers that were identified as relevant to the content of the DRR included: barriers to discharge, discharge criteria, home care, postdischarge care, and last minute delays. We also identified secondary drivers related to the design of the DRR. We hypothesized that addressing the secondary drivers would be essential to end user adoption of the tool. The secondary drivers included: accessibility, relevance, ease of updating, automation, and readability.

With the swim lane diagram as well as our primary and secondary drivers in mind, we created a mock DRR on paper. We conducted multiple patient discharge simulations with representatives from all disciplines, walking through each step of a patient hospitalization from registration to discharge. This allowed us to map out how preexisting, yet disparate, EHR data could be channeled into 1 report. A few changes were made to processes involving data collection and documentation to facilitate timely transfer of information to the report. For example, questions addressing potential barriers to discharge and whether a school/work excuse was needed were added to the admission nursing assessment.

We then moved the paper DRR to the electronic environment. Data elements that were pulled automatically into the report included: potential barriers to discharge collected during nursing intake, case management information on home care needs, discharge criteria entered by resident and attending physicians, PCP, home pharmacy, follow‐up appointments, school/work excuse information gathered by resident liaisons, and active patient problems drawn from the problem list section. These data were organized into 4 distinct domains within the final DRR: potential barriers, transitional care, home care, and discharge criteria (Table 1).

| Discharge Readiness Report Domain | Example Content |

|---|---|

| |

| Potential barriers to discharge | Geographic location of the family, whether patient lives in more than 1 household, primary spoken language, financial or insurance concern, and need for work/subhool excuses |

| Transitional care | PCP and home pharmacy information, follow‐up ambulatory and imaging appointments, and care team communications with the PCP |

| Home care | Planned discharge date/time and home care needs assessments such as needs for special equipment or skilled home nursing |

| Discharge criteria | Clinical, social, or other care coordination conditions for discharge |

Additional features potentially important to discharge planning were also incorporated into the report based on end user feedback. These included hyperlinks to discharge orders, home oxygen prescriptions, and the after‐visit summary for families, and the patient's home care company (if present). To facilitate discharge and transitional care related communication between the primary team and subspecialty teams, consults involved during the hospitalization were included on the report. As home care arrangements often involve care for active lines and drains, they were added to the report (Figure 2).

Implementation

The report was activated within the EHR in June 2012. The team focused initial promotion and education efforts on medical floors. Education was widely disseminated via email and in‐person presentations.

The DRR was incorporated into daily CCRs for medical patients in July 2012. These multidisciplinary rounds occurred after medical‐team bedside rounds, focusing on care coordination and discharge planning. For each patient discussed, the DRR was projected onto a large screen, allowing all team members to view and discuss relevant discharge information. A process improvement (PI) specialist attended CCRs daily for several months, educating participants and monitoring use of the DRR. The PI specialist solicited feedback on ways to improve the DRR, and timed rounds to measure whether use of the DRR prolonged CCRs.

In the first weeks postimplementation, the use of the DRR prolonged rounds by as much as 1 minute per patient. Based on direct observation, the team focused interventions on barriers to the efficient use of the report during CCRs including: the need to scroll through the report, which was not visible on 1 screen; the need to navigate between patients; the need to quickly update the report based on discussion; and the need to update discharge criteria (Figure 3).

RESULTS

Creation of the final DRR required significant time and effort and was the culmination of a uniquely collaborative effort between clinicians, ancillary staff, and information technology specialists (Figure 4). The report is used consistently for all general medical and medical subspecialty patients during CCRs. After interventions were implemented to improve the efficiency of using the DRR during CCRs, the use of the DRR did not prolong CCRs. Members of the care team acknowledge that all sections of the report are populated and accurate. Though end users have commented on their use of the report outside of CCRs, we have not been able to formally measure this.

We have noticed a shift in the focus of discussion since implementation of the DRR. Prior to this initiative, care teams at our institution did not regularly discuss discharge criteria during bedside or CCRs. The phrase discharge criteria has now become part of our shared language.

Informally, the DRR appears to have reduced inefficiency and the potential for communication error. The practice of writing notes on printed patient lists to be used to sign‐out or communicate to other team members not in attendance at CCRs has largely disappeared.

The DRR has proven to be adaptable across patient units, and can be tailored to the specific transitional care needs of a given patient population. At discharge institution, the DRR has been modified for, and has taken on a prominent role in, the discharge planning of highly complex populations such as rehabilitation and ventilated patients.

DISCUSSION

Discharge planning is a multifaceted, multidisciplinary process that should begin at the time of hospital admission. Safe patient transition depends on efficient discharge processes and effective communication across settings.[8] Although not well studied in the inpatient setting, care process variability can result in inefficient patient flow and increased stress among staff.[9] Patients and families may experience confusion, coping difficulties, and increased readmission due to ineffective discharge planning.[10] These potential pitfalls highlight the need for healthcare providers to develop patient‐centered, systematic approaches to improving the discharge process.[11]

To our knowledge, this is the first description of a discharge planning tool for the EHR in the pediatric setting. Our discharge report is centralized, easily accessible by all members of the care team, and includes important patient‐specific discharge‐related information that be used to focus discussion and streamline multidisciplinary discharge planning rounds.

We anticipate that the report will allow the entire healthcare team to function more efficiently, decrease discharge‐related delays and failures based on communication roadblocks, and improve family and caregiver satisfaction with the discharge process. We are currently testing these hypotheses and evaluating several implementation strategies in an ongoing research study. Assuming positive impact, we plan to spread the use of the DRR to all inpatient care areas at our hospital, and potentially to other hospitals.

The limitations of this QI project are consistent with other initiatives to improve care. The challenges we encounter at our freestanding tertiary care teaching hospital with regard to effective discharge planning and multidisciplinary communication may not be generalizable to other nonteaching or community hospitals, and the DRR may not be useful in other settings. Though the report is now a part of our EHR, the most impactful implementation strategies remain to be determined. The report and related changes represent significant diversion from years of deeply ingrained workflows for some providers, and we encountered some resistance from staff during the early stages of implementation. The most important of which was that some team members are uncomfortable with technology and prefer to use paper. Most of this initial resistance was overcome by implementing changes to improve the ease of use of the report (Figure 3). Though input from end users and key stakeholders has been incorporated throughout this initiative, more work is needed to measure end user adoption and satisfaction with the report.

CONCLUSION

High‐quality hospital discharge planning requires an increasingly multidisciplinary approach. The EHR can be leveraged to improve transparency and interdisciplinary communication around the discharge process. An integrated summary of discharge‐related issues, organized into 1 highly visible and easily accessible report in the EHR has the potential to improve care transitions.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

According to the American Academy of Pediatrics clinical report on physicians' roles in coordinating care of hospitalized children, there are several important components of hospital discharge planning.[1] Foremost is that discharge planning should begin, and discharge criteria should be set, at the time of hospital admission. This allows for optimal engagement of parents and providers in the effort to adequately prepare patients for the transition to home.

As pediatric inpatients become increasingly complex,[2] adequately preparing families for the transition to home becomes more challenging.[3] There are a myriad of issues to address and the burden of this preparation effort falls on multiple individuals other than the bedside nurse and physician. Large multidisciplinary teams often play a significant role in the discharge of medically complex children.[4] Several challenges may hinder the team's ability to effectively navigate the discharge process such as financial or insurance‐related issues, language differences, or geographic barriers. Patient and family anxieties may also complicate the transition to home.[5]

The challenges of a multidisciplinary approach to discharge planning are further magnified by the limitations of the electronic health record (EHR). The EHR is well designed to record individual encounters, but poorly designed to coordinate longitudinal care across settings.[6] Although multidisciplinary providers may spend significant and well‐intentioned energy to facilitate hospital discharge, their efforts may go unseen or be duplicative.

We developed a discharge readiness report (DRR) for the EHR, an integrated summary of discharge‐related issues, organized into a highly visible and easily accessible report. The development of the discharge planning tool was the first step in a larger quality improvement (QI) initiative aimed at improving the efficiency, effectiveness, and safety of hospital discharge. Our team recognized that improving the flow and visibility of information between disciplines was the first step toward accomplishing this larger aim. Health information technology offers an important opportunity for the improvement of patient safety and care transitions7; therefore, we leveraged the EHR to create an integrated discharge report. We used QI methods to understand our hospital's discharge processes, examined potential pitfalls in interdisciplinary communication, determined relevant information to include in the report, and optimized ways to display the data. To our knowledge, this use of the EHR is novel. The objectives of this article were to describe our team's development and implementation strategies, as well as challenges encountered, in the design of this electronic discharge planning tool.

METHODS

Setting

Children's Hospital Colorado is a 413‐bed freestanding tertiary care teaching hospital with over 13,000 inpatient admissions annually and an average patient length of stay of 5.7 days. We were the first children's hospital to fully implement a single EHR (Epic Systems, Madison, WI) in 2006. This discharge improvement initiative emerged from our hospital's involvement in the Children's Hospital Association Discharge Collaborative between October 2011 and October 2012. We were 1 of 12 participating hospitals and developed several different projects within the framework of the initiative.

Improvement Team

Our multidisciplinary project team included hospitalist physicians, case managers, social workers, respiratory therapists, pharmacists, medical interpreters, process improvement specialists, clinical application specialists whose daily role is management of our hospital's EHR software, and resident liaisons whose daily role is working with residents to facilitate care coordination.

Ethics

The project was determined to be QI work by the Children's Hospital Colorado Organizational Research Risk and Quality Improvement Review Panel.

Understanding the Problem

To understand the perspectives of each discipline involved in discharge planning, the lead hospitalist physician and a process improvement specialist interviewed key representatives from each group. Key informant interviews were conducted with hospitalist physicians, case managers, nurses, social workers, resident liaisons, respiratory therapists, pharmacists, medical interpreters, and residents. We inquired about their informational needs, their methods for obtaining relevant information, and whether the information was currently documented in the EHR. We then used process mapping to learn each disciplines' workflow related to discharge planning. Finally, we gathered key stakeholders together for a group session where discharge planning was mapped using the example of a patient admitted with asthma. From this session, we created a detailed multidisciplinary swim lane process map, a flowchart displaying the sequence of events in the overall discharge process grouped visually by placing the events in lanes. Each lane represented a discipline involved in patient discharge, and the arrows between lanes showed how information is passed between the various disciplines. Using this diagram, the team was able to fully understand provider interdependence in discharge planning and longitudinal timing of discharge‐related tasks during the patient's hospitalization.

We learned that: (1) discharge planning is complex, and there were often multiple provider types involved in the discharge of a single patient; (2) communication and coordination between the multitude of providers was often suboptimal; and (3) many of the tasks related to discharge were left to the last minute, resulting in unnecessary delays. Underlying these problems was a clear lack of organized and visible discharge planning information within the EHR.

There were many examples of obscure and siloed discharge processes. Physicians were aware of discharge criteria, but did not document these criteria for others to see. Case management assessments of home health needs were conveyed verbally to other team members, creating the potential for omissions, mistakes, or delays in appropriate home health planning. Social workers helped families to navigate financial hurdles (eg, assistance with payments for prescription medications). However, the presence of financial or insurance problems was not readily apparent to front‐line clinicians making discharge decisions. Other factors with potential significance for discharge planning, such as English‐language proficiency or a family's geographic distance from the hospital, were buried in disparate flow sheets or reports and not available or apparent to all health team members. There were also clear examples of discharge‐related tasks occurring at the end of hospitalization that could easily have been completed earlier in the admission such as identifying a primary care provider (PCP), scheduling follow‐up appointments, and completing work/subhool excuses because of lack of care team awareness that these items were needed.

Planning the Intervention

Based on our learning, we developed a key driver diagram (Figure 1). Our aim was to create a DRR that organized important discharge‐related information into 1 easily accessible report. Key drivers that were identified as relevant to the content of the DRR included: barriers to discharge, discharge criteria, home care, postdischarge care, and last minute delays. We also identified secondary drivers related to the design of the DRR. We hypothesized that addressing the secondary drivers would be essential to end user adoption of the tool. The secondary drivers included: accessibility, relevance, ease of updating, automation, and readability.

With the swim lane diagram as well as our primary and secondary drivers in mind, we created a mock DRR on paper. We conducted multiple patient discharge simulations with representatives from all disciplines, walking through each step of a patient hospitalization from registration to discharge. This allowed us to map out how preexisting, yet disparate, EHR data could be channeled into 1 report. A few changes were made to processes involving data collection and documentation to facilitate timely transfer of information to the report. For example, questions addressing potential barriers to discharge and whether a school/work excuse was needed were added to the admission nursing assessment.

We then moved the paper DRR to the electronic environment. Data elements that were pulled automatically into the report included: potential barriers to discharge collected during nursing intake, case management information on home care needs, discharge criteria entered by resident and attending physicians, PCP, home pharmacy, follow‐up appointments, school/work excuse information gathered by resident liaisons, and active patient problems drawn from the problem list section. These data were organized into 4 distinct domains within the final DRR: potential barriers, transitional care, home care, and discharge criteria (Table 1).

| Discharge Readiness Report Domain | Example Content |

|---|---|

| |

| Potential barriers to discharge | Geographic location of the family, whether patient lives in more than 1 household, primary spoken language, financial or insurance concern, and need for work/subhool excuses |

| Transitional care | PCP and home pharmacy information, follow‐up ambulatory and imaging appointments, and care team communications with the PCP |

| Home care | Planned discharge date/time and home care needs assessments such as needs for special equipment or skilled home nursing |

| Discharge criteria | Clinical, social, or other care coordination conditions for discharge |

Additional features potentially important to discharge planning were also incorporated into the report based on end user feedback. These included hyperlinks to discharge orders, home oxygen prescriptions, and the after‐visit summary for families, and the patient's home care company (if present). To facilitate discharge and transitional care related communication between the primary team and subspecialty teams, consults involved during the hospitalization were included on the report. As home care arrangements often involve care for active lines and drains, they were added to the report (Figure 2).

Implementation

The report was activated within the EHR in June 2012. The team focused initial promotion and education efforts on medical floors. Education was widely disseminated via email and in‐person presentations.

The DRR was incorporated into daily CCRs for medical patients in July 2012. These multidisciplinary rounds occurred after medical‐team bedside rounds, focusing on care coordination and discharge planning. For each patient discussed, the DRR was projected onto a large screen, allowing all team members to view and discuss relevant discharge information. A process improvement (PI) specialist attended CCRs daily for several months, educating participants and monitoring use of the DRR. The PI specialist solicited feedback on ways to improve the DRR, and timed rounds to measure whether use of the DRR prolonged CCRs.

In the first weeks postimplementation, the use of the DRR prolonged rounds by as much as 1 minute per patient. Based on direct observation, the team focused interventions on barriers to the efficient use of the report during CCRs including: the need to scroll through the report, which was not visible on 1 screen; the need to navigate between patients; the need to quickly update the report based on discussion; and the need to update discharge criteria (Figure 3).

RESULTS

Creation of the final DRR required significant time and effort and was the culmination of a uniquely collaborative effort between clinicians, ancillary staff, and information technology specialists (Figure 4). The report is used consistently for all general medical and medical subspecialty patients during CCRs. After interventions were implemented to improve the efficiency of using the DRR during CCRs, the use of the DRR did not prolong CCRs. Members of the care team acknowledge that all sections of the report are populated and accurate. Though end users have commented on their use of the report outside of CCRs, we have not been able to formally measure this.

We have noticed a shift in the focus of discussion since implementation of the DRR. Prior to this initiative, care teams at our institution did not regularly discuss discharge criteria during bedside or CCRs. The phrase discharge criteria has now become part of our shared language.

Informally, the DRR appears to have reduced inefficiency and the potential for communication error. The practice of writing notes on printed patient lists to be used to sign‐out or communicate to other team members not in attendance at CCRs has largely disappeared.

The DRR has proven to be adaptable across patient units, and can be tailored to the specific transitional care needs of a given patient population. At discharge institution, the DRR has been modified for, and has taken on a prominent role in, the discharge planning of highly complex populations such as rehabilitation and ventilated patients.

DISCUSSION

Discharge planning is a multifaceted, multidisciplinary process that should begin at the time of hospital admission. Safe patient transition depends on efficient discharge processes and effective communication across settings.[8] Although not well studied in the inpatient setting, care process variability can result in inefficient patient flow and increased stress among staff.[9] Patients and families may experience confusion, coping difficulties, and increased readmission due to ineffective discharge planning.[10] These potential pitfalls highlight the need for healthcare providers to develop patient‐centered, systematic approaches to improving the discharge process.[11]

To our knowledge, this is the first description of a discharge planning tool for the EHR in the pediatric setting. Our discharge report is centralized, easily accessible by all members of the care team, and includes important patient‐specific discharge‐related information that be used to focus discussion and streamline multidisciplinary discharge planning rounds.

We anticipate that the report will allow the entire healthcare team to function more efficiently, decrease discharge‐related delays and failures based on communication roadblocks, and improve family and caregiver satisfaction with the discharge process. We are currently testing these hypotheses and evaluating several implementation strategies in an ongoing research study. Assuming positive impact, we plan to spread the use of the DRR to all inpatient care areas at our hospital, and potentially to other hospitals.

The limitations of this QI project are consistent with other initiatives to improve care. The challenges we encounter at our freestanding tertiary care teaching hospital with regard to effective discharge planning and multidisciplinary communication may not be generalizable to other nonteaching or community hospitals, and the DRR may not be useful in other settings. Though the report is now a part of our EHR, the most impactful implementation strategies remain to be determined. The report and related changes represent significant diversion from years of deeply ingrained workflows for some providers, and we encountered some resistance from staff during the early stages of implementation. The most important of which was that some team members are uncomfortable with technology and prefer to use paper. Most of this initial resistance was overcome by implementing changes to improve the ease of use of the report (Figure 3). Though input from end users and key stakeholders has been incorporated throughout this initiative, more work is needed to measure end user adoption and satisfaction with the report.

CONCLUSION

High‐quality hospital discharge planning requires an increasingly multidisciplinary approach. The EHR can be leveraged to improve transparency and interdisciplinary communication around the discharge process. An integrated summary of discharge‐related issues, organized into 1 highly visible and easily accessible report in the EHR has the potential to improve care transitions.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

- . Clinical report—physicians' roles in coordinating care of hospitalized children. Pediatrics. 2010;126:829–832.

- , , , , , . Increasing prevalence of medically complex children in US hospitals. Pediatrics. 2010;126:638–646.