User login

The management of inflammatory bowel disease in pregnancy

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) incidence is rising globally.1-3 In the United States, we have seen a 123% increase in prevalence of IBD among adults and a 133% increase among children from 2007 to 2016, with an annual percentage change of 9.9%.1 The rise of IBD in young people, and the overall higher prevalence in women compared with men, make pregnancy and IBD a topic of increasing importance for gastroenterologists.1 Here, we will discuss management and expectations in women with IBD before conception, during pregnancy, and post partum.

Preconception

Disease activity

Achieving both clinical and endoscopic remission of disease prior to conception is the key to ensuring the best maternal and fetal outcomes. Patients with IBD who conceive while in remission remain in remission 80% of the time.4,5 On the other hand, those who conceive while their disease is active may continue to have active or worsening disease in nearly 70% of cases.4 Active disease has been associated with an increased incidence of preterm birth, low birth weight, and small-for-gestational-age birth.6-8 Active disease can also exacerbate malnutrition and result in poor maternal weight gain, which is associated with intrauterine growth restriction.9,7 Pregnancy outcomes in patients with IBD and quiescent disease are similar to those in the general population.10,11

Health care maintenance

Optimizing maternal health prior to conception is critical. Alcohol, tobacco, recreational drugs, and marijuana should all be avoided. Opioids should be tapered off prior to conception, as continued use may result in neonatal opioid withdrawal syndrome and long-term neurodevelopmental consequences.12,13 In addition, aiming for a healthy body mass index between 18 and 25 months prior to conception allows for better overall pregnancy outcomes.13 Appropriate cancer screening includes colon cancer screening in those with more than 8 years of colitis, regular pap smear for cervical cancer, and annual total body skin cancer examinations for patients on thiopurines and biologic therapies.14

Nutrition

Folic acid supplementation with at least 400 micrograms (mcg) daily is necessary for all women planning pregnancy. Patients with small bowel involvement or history of small bowel resection should have a folate intake of a minimum of 2 grams per day. Adequate vitamin D levels (at least 20 ng/mL) are recommended in all women with IBD. Those with malabsorption should be screened for deficiencies in vitamin B12, folate, and iron.13 These nutritional markers should be evaluated prepregnancy, during the first trimester, and thereafter as needed.15-18

Preconception counseling

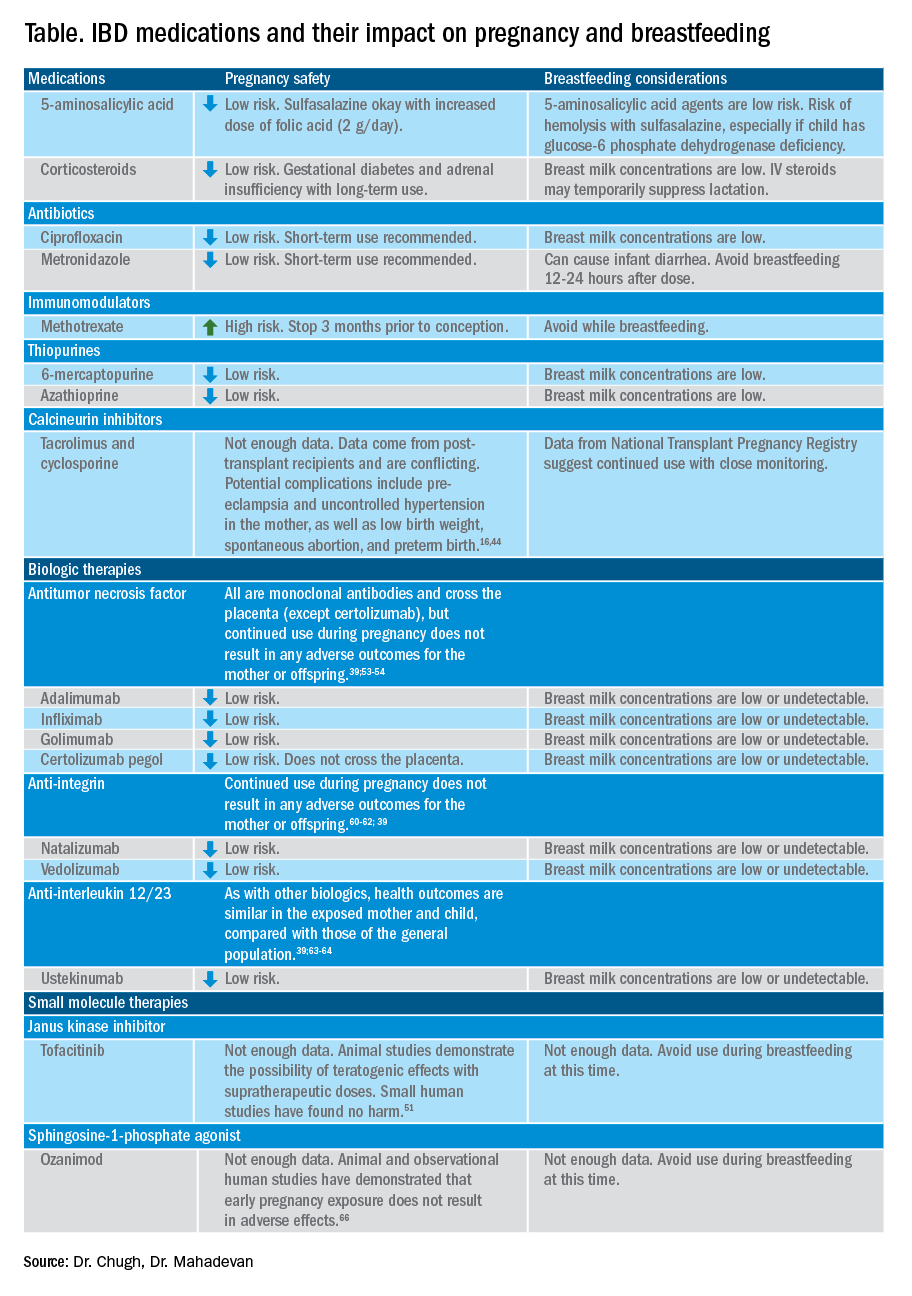

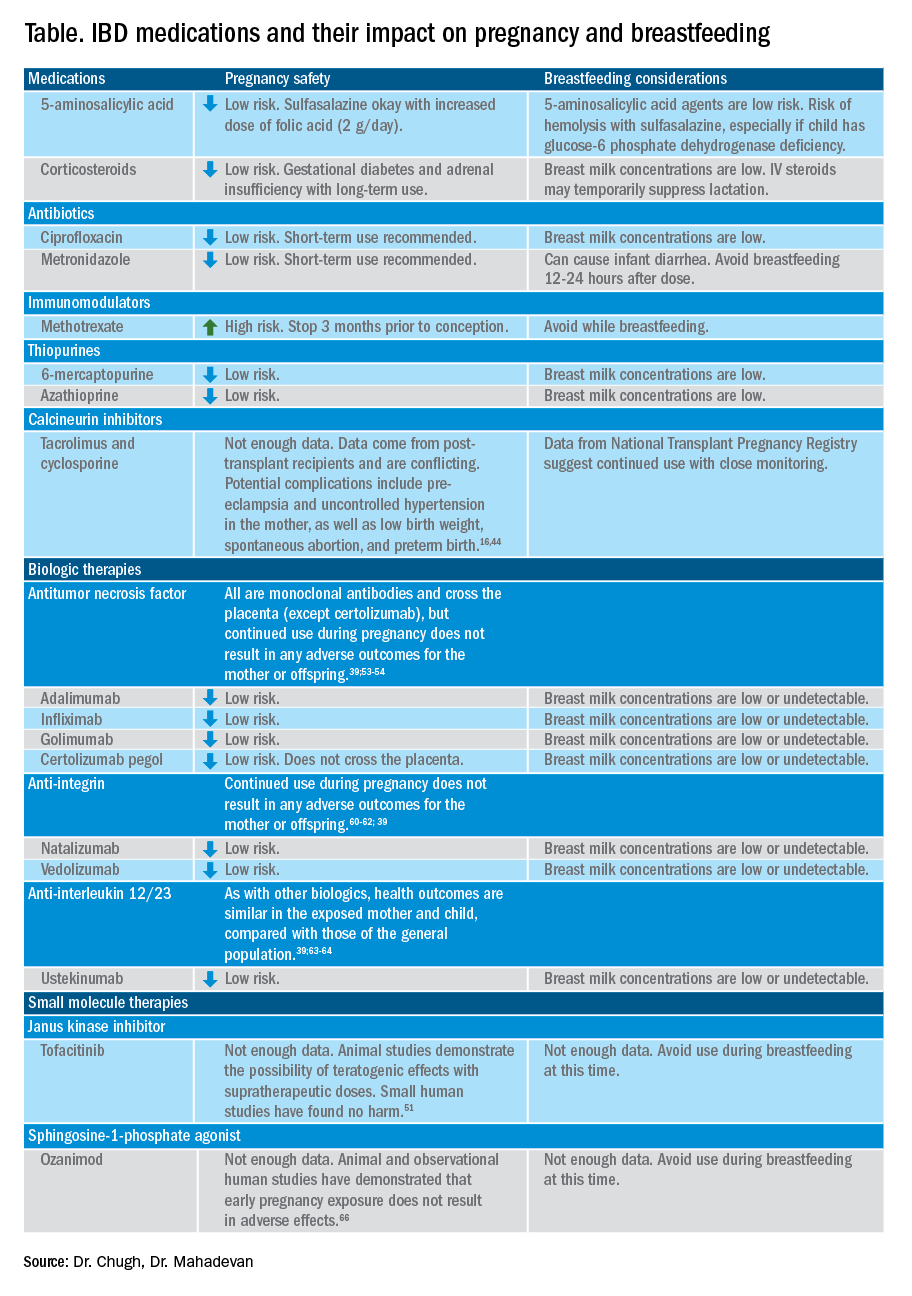

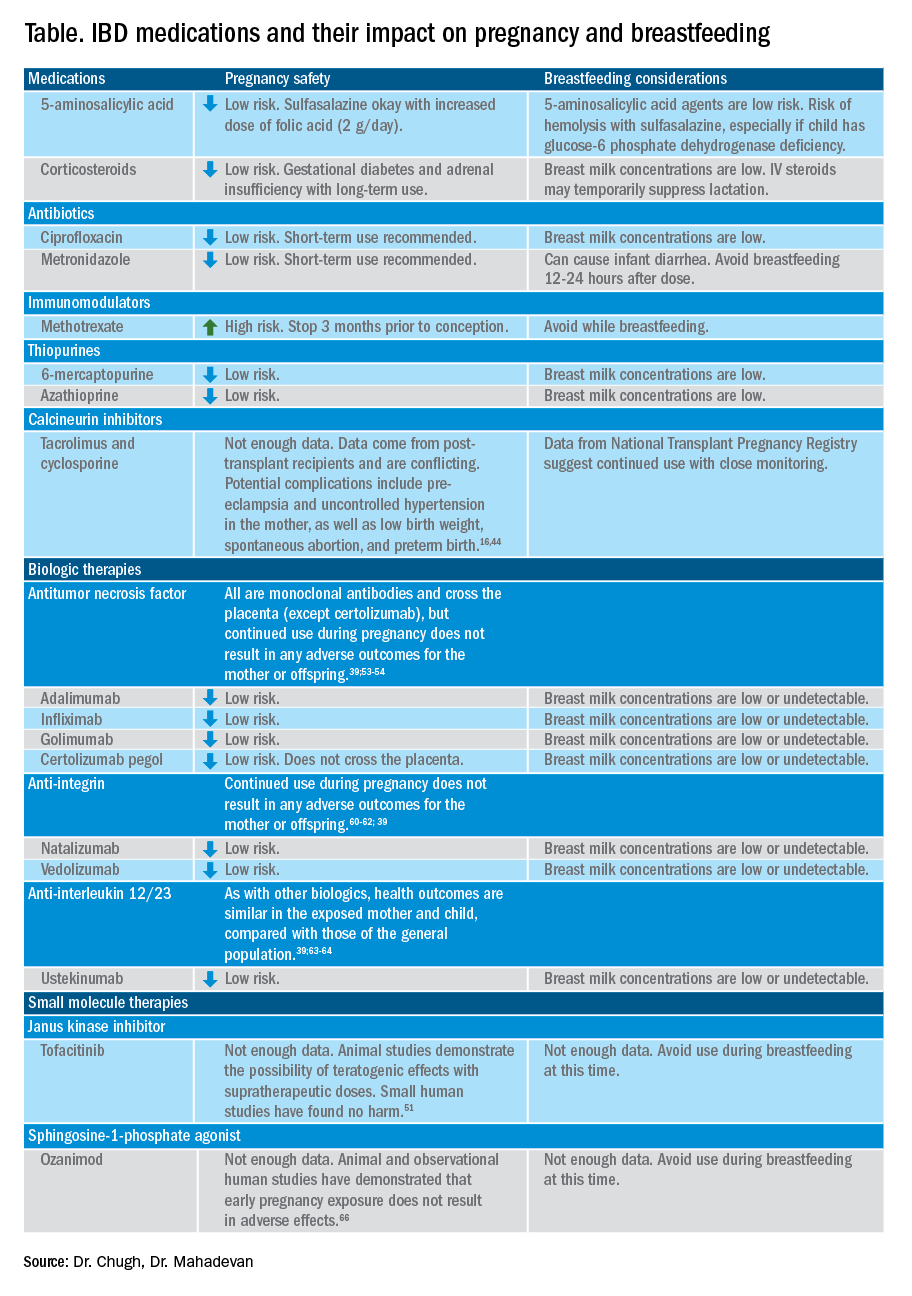

Steroid-free remission for at least 3 months prior to conception is recommended and is associated with reduced risk of flare during pregnancy.16,19 IBD medications needed to control disease activity are generally safe preconception and during pregnancy, with some exception (Table).

Misconceptions regarding heritability of IBD have sometimes discouraged men and women from having children. While genetics may increase susceptibility, environmental and other factors are involved as well. The concordance rates for monozygotic twins range from 33.3%-58.3% for Crohn’s disease and 13.4%-27.9% for ulcerative colitis (UC).20 The risk of a child developing IBD is higher in those who have multiple relatives with IBD and whose parents had IBD at the time of conception.21 While genetic testing for IBD loci is available, it is not commonly performed at this time as many genes are involved.22

Pregnancy

Coordinated care

A complete team of specialists with coordinated care among all providers is needed for optimal maternal and fetal outcomes.23,24 A gastroenterologist, ideally an IBD specialist, should follow the patient throughout pregnancy, seeing the patient at least once during the first or second trimester and as needed during pregnancy.16 A high-risk obstetrician or maternal-fetal medicine specialist should be involved early in pregnancy, as well. Open communication among all disciplines ensures that a common message is conveyed to the patient.16,24 A nutritionist, mental health provider, and lactation specialist knowledgeable about IBD drugs may be of assistance, as well.16

Disease activity

While women with IBD are at increased risk of spontaneous abortion, preterm birth, and labor complications, this risk is mitigated by controlling disease activity.25 The risk of preterm birth, small-for-gestational-age birth, and delivery via C-section is much higher in women with moderate-to-high disease activity, compared with those with low disease activity.26 The presence of active perianal disease mandates C-section over vaginal delivery. Fourth-degree lacerations following vaginal delivery are most common among those patients with perianal disease.26,27 Stillbirths were shown to be increased only in those with active IBD when compared with non-IBD comparators and inactive IBD.28-31;11

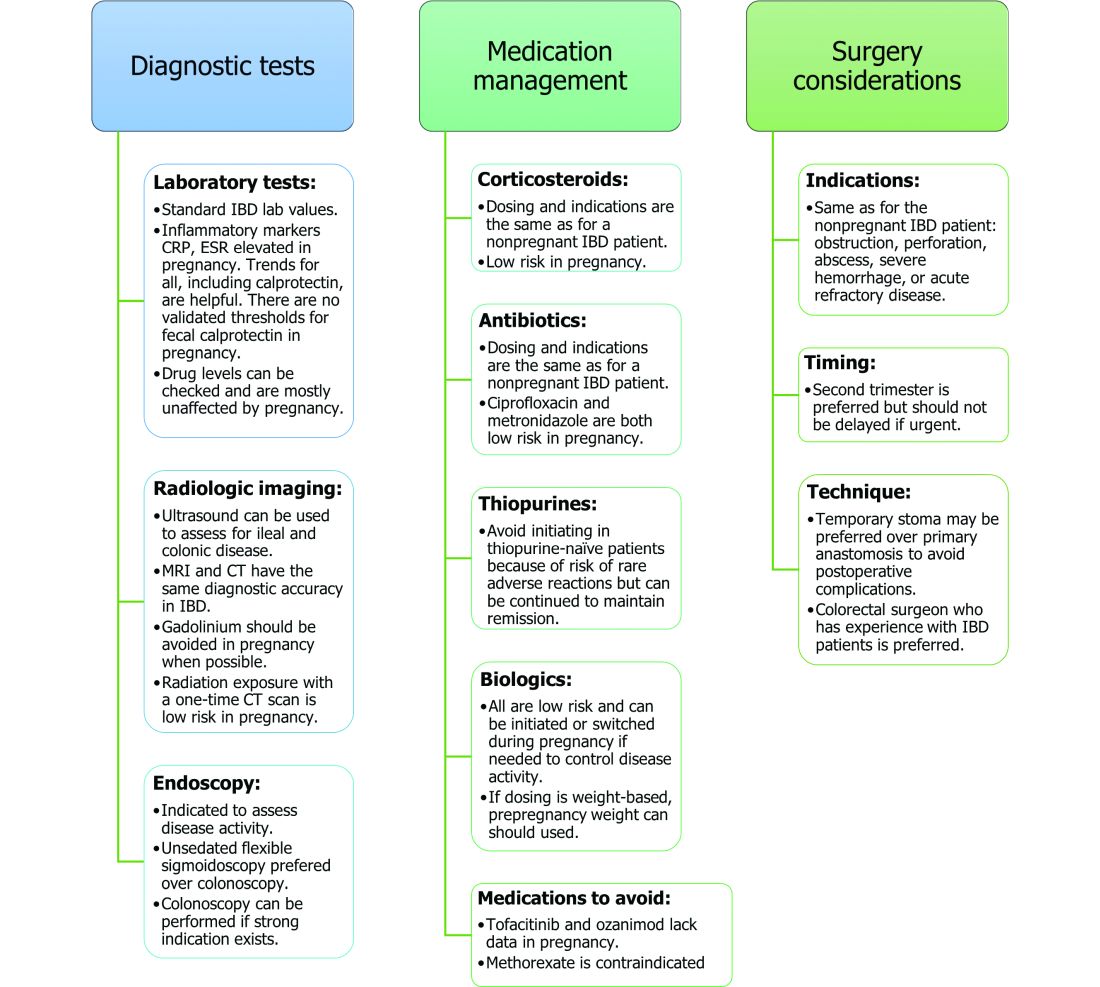

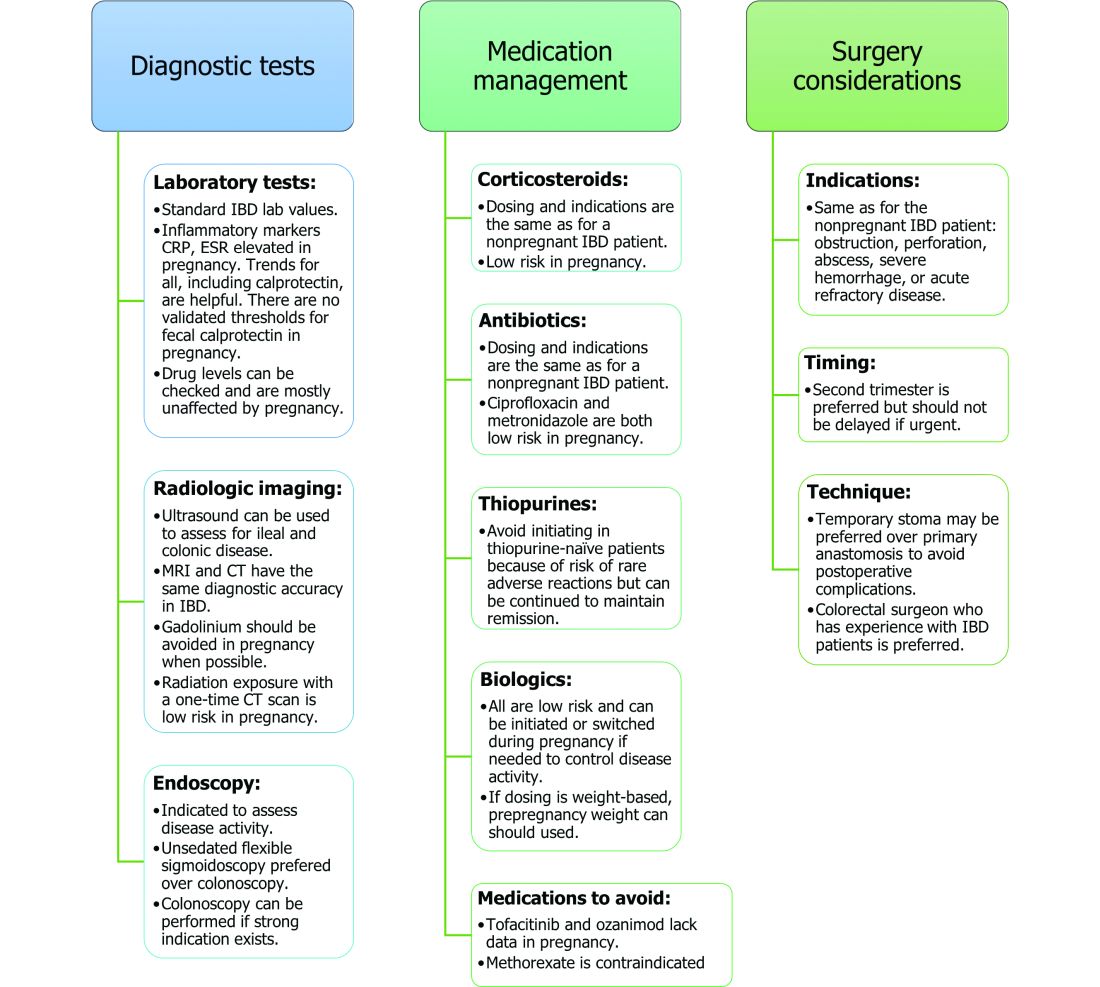

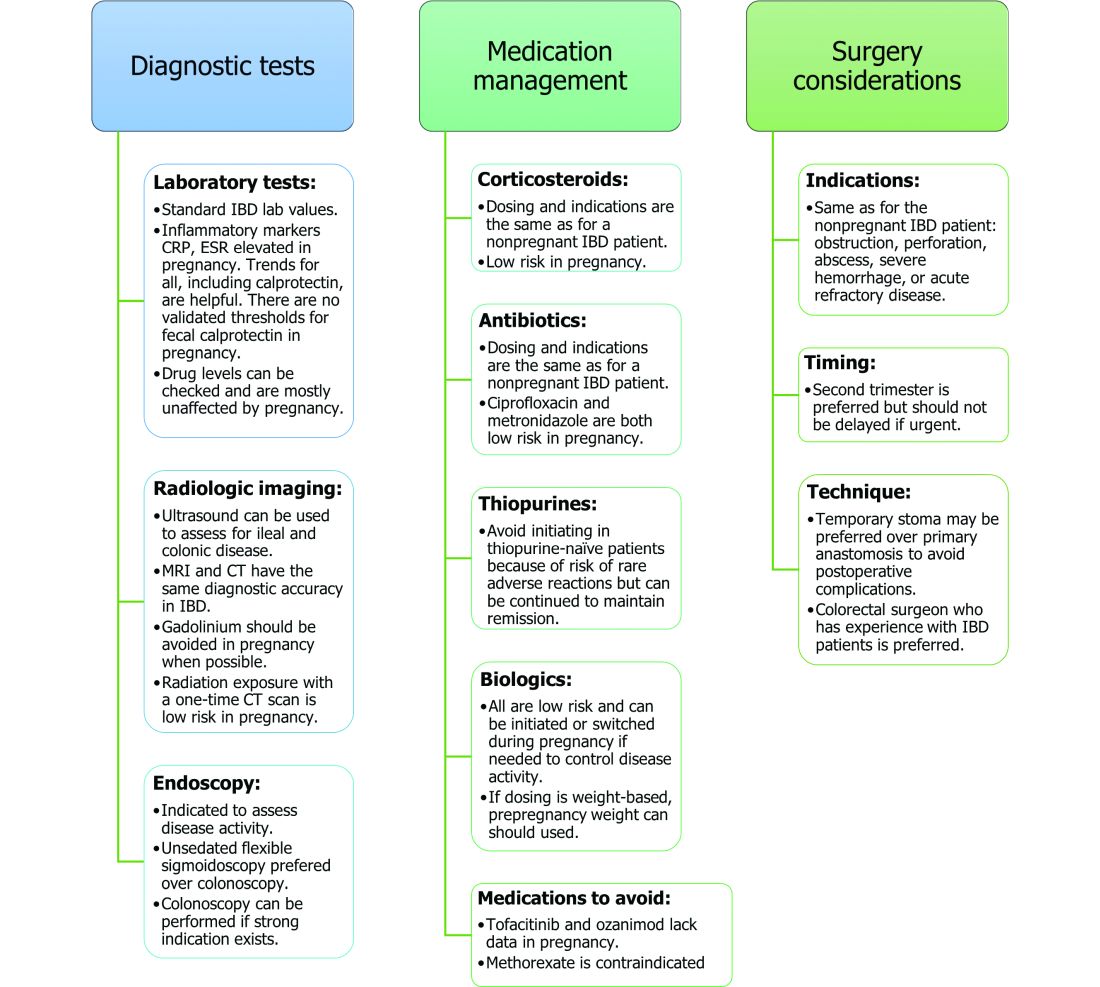

Noninvasive methods for disease monitoring are preferred in pregnancy, but serum markers such as erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein may not be reliable in the pregnant patient (Figure).32 Fecal calprotectin does rise in correlation with disease activity, but exact thresholds have not been validated in pregnancy.33,34

An unsedated, unprepped flexible sigmoidoscopy can be safely performed throughout pregnancy.35 When there is a strong indication, a complete colonoscopy can be performed in the pregnant patient as well.36 Current American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) guidelines suggest placing the patient in the left lateral tilt position to avoid decreased maternal and placental perfusion via compression of the aorta or inferior vena cava and performing endoscopy during the second trimester, although trimester-specific timing is not always feasible by indication.37

Medication use and safety

IBD medications are a priority topic of concern among pregnant patients or those considering conception.38 Comprehensive data from the PIANO (Pregnancy in Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Neonatal Outcomes) registry has shown that most IBD drugs do not result in adverse pregnancy outcomes and should be continued.39 The use of biologics and thiopurines, either in combination or alone, is not related to an increased risk of congenital malformations, spontaneous abortion, preterm birth, low birth weight, or infections during the child’s first year of life.7,39 Developmental milestones also remain unaffected.39 Here, we will discuss safety considerations during pregnancy (see Table).

5-aminosalycylic acid. 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA) agents are generally low risk during pregnancy and should be continued.40-41 Sulfasalazine does interfere with folate metabolism, but by increasing folic acid supplementation to 2 grams per day, sulfasalazine can be continued throughout pregnancy, as well.42

Corticosteroids. Intrapartum corticosteroid use is associated with an increased risk of gestational diabetes and adrenal insufficiency when used long term.43-45 Short-term use may, however, be necessary to control an acute flare. The lowest dose for the shortest duration possible is recommended. Because of its high first-pass metabolism, budesonide is considered low risk in pregnancy.

Methotrexate. Methotrexate needs to be stopped at least 3 months prior to conception and should be avoided throughout pregnancy. Use during pregnancy can result in spontaneous abortions, as well as embryotoxicity.46

Thiopurines (6-mercaptopurine and azathioprine). Patients who are taking thiopurines prior to conception to maintain remission can continue to do so. Data on thiopurines from the PIANO registry has shown no increase in spontaneous abortions, congenital malformations, low birth weight, preterm birth, rates of infection in the child, or developmental delays.47-51

Calcineurin inhibitors (cyclosporine and tacrolimus). Calcineurin inhibitors are reserved for the management of acute severe UC. Safety data on calcineurin inhibitors is conflicting, and there is not enough information at this time to identify risk during pregnancy. Cyclosporine can be used for salvage therapy if absolutely needed, and there are case reports of its successful using during pregnancy.16,52

Biologic therapies. With the exception of certolizumab, all of the currently used biologics are actively transported across the placenta.39,53,54 Intrapartum use of biologic therapies does not worsen pregnancy or neonatal outcomes, including the risk for intensive care unit admission, infections, and developmental milestones.39,47

While drug concentrations may vary slightly during pregnancy, these changes are not substantial enough to warrant more frequent monitoring or dose adjustments, and prepregnancy weight should be used for dosing.55,56

Antitumor necrosis factor agents used in IBD include infliximab, adalimumab, certolizumab, and golimumab.57 All are low risk for pregnant patients and their offspring. Dosage timings can be adjusted, but not stopped, to minimize exposure to the child; however, it cannot be adjusted for certolizumab pegol because of its lack of placental transfer.58-59

Natalizumab and vedolizumab are integrin receptor antagonists and are also low risk in pregnancy.57;60-62;39

Ustekinumab, an interleukin-12/23 antagonist, can be found in infant serum and cord blood, as well. Health outcomes are similar in the exposed mother and child, however, compared with those of the general population.39;63-64

Small molecule drugs. Unlike monoclonal antibodies, which do not cross the placenta in large amounts until early in the second trimester, small molecules can cross in the first trimester during the critical period of organogenesis.

The two small molecule agents currently approved for use in UC are tofacitinib, a janus kinase inhibitor, and ozanimod, a sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor agonist.65-66 Further data are still needed to make recommendations on the use of tofacitinib and ozanimod in pregnancy. At this time, we recommend weighing the risks (unknown risk to human pregnancy) vs. benefits (controlled disease activity with clear risk of harm to mother and baby from flare) in the individual patient before counseling on use in pregnancy.

Delivery

Mode of delivery

The mode of delivery should be determined by the obstetrician. C-section is recommended for patients with active perianal disease or, in some cases, a history of ileal pouch anal anastomosis (IPAA).67-68 Vaginal delivery in the setting of perianal disease has been shown to increase the risk of fourth-degree laceration and anal sphincter dysfunction in the future.26-27 Anorectal motility may be impacted by IPAA construction and vaginal delivery independently of each other. It is therefore suggested that vaginal delivery be avoided in patients with a history of IPAA to avoid compounding the risk. Some studies do not show clear harm from vaginal delivery in the setting of IPAA, however, and informed decision making among all stakeholders should be had.27;69-70

Anticoagulation

The incidence of venous thromboembolism (VTE) is elevated in patients with IBD during pregnancy, and up to 12 weeks postpartum, compared with pregnant patients without IBD.71-72 VTE for prophylaxis is indicated in the pregnant patient while hospitalized and potentially thereafter depending on the patient’s risk factors, which may include obesity, prior personal history of VTE, heart failure, and prolonged immobility. Unfractionated heparin, low molecular weight heparin, and warfarin are safe for breastfeeding women.16,73

Postpartum care of mother

There is a risk of postpartum flare, occurring in about one third of patients in the first 6 months postpartum.74-75 De-escalating therapy during delivery or immediately postpartum is a predictor of a postpartum flare.75 If no infection is present and the timing interval is appropriate, biologic therapies should be continued and can be resumed 24 hours after a vaginal delivery and 48 hours after a C-section.16,76

NSAIDs and opioids can be used for pain relief but should be avoided in the long-term to prevent flares (NSAIDs) and infant sedation (associated with opioids) when used while breastfeeding.77 The LactMed database is an excellent resource for clarification on risk of medication use while breastfeeding.78

In particular, contraception should be addressed postpartum. Exogenous estrogen use increases the risk of VTE, which is already increased in IBD; nonestrogen containing, long-acting reversible contraception is preferred.79-80 Progestin-only implants or intrauterine devices may be used first line. The efficacy of oral contraceptives is theoretically reduced in those with rapid bowel transit, active small bowel inflammation, and prior small bowel resection, so adding another form of contraception is recommended.16,81

Source: American Gastroenterological Association

Postdelivery care of baby

Breastfeeding

Guidelines regarding medication use during breastfeeding are similar to those in pregnancy (see Table). Breastfeeding on biologics and thiopurines can continue without interruption in the child. Thiopurine concentrations in breast milk are low or undetectable.82,78 TNF receptor antagonists, anti-integrin therapies, and ustekinumab are found in low to undetectable levels in breast milk, as well.78

On the other hand, the active metabolite of methotrexate is detectable in breast milk and most sources recommend not breastfeeding on methotrexate. At doses used in IBD (15-25 milligrams per week), some experts have suggested avoiding breastfeeding for 24 hours following a dose.57,78 It is the practice of this author to recommend not breastfeeding at all on methotrexate.

5-ASA therapies are low risk for breastfeeding, but alternatives to sulfasalazine are preferred. The sulfapyridine metabolite transfers to breast milk and may cause hemolysis in infants born with a glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency.78

With regards to calcineurin inhibitors, tacrolimus appears in breast milk in low quantities, while cyclosporine levels are variable. Data from the National Transplantation Pregnancy Registry suggest that these medications can be used at the time of breastfeeding with close monitoring.78

There is not enough data on small molecule therapies at this time to support breastfeeding safety, and it is our practice to not recommend breastfeeding in this scenario.

The transfer of steroids to the child via breast milk does occur but at subtherapeutic levels.16 Budesonide has high first pass metabolism and is low risk during breastfeeding.83-84 As far as is known, IBD maintenance medications do not suppress lactation. The use of intravenous corticosteroids can, however, temporarily decrease milk production.16,85

Vaccines

Vaccination of infants can proceed as indicated by the Center for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines, with one exception. If the child’s mother was exposed to any biologic agents (not including certolizumab) during the third trimester, any live vaccines should be withheld in the first 6 months of life. In the United States, this restriction currently only applies to the rotavirus vaccine, which is administered starting at the age of 2 months.16,86 Notably, inadvertent administration of the rotavirus vaccine in the biologic-exposed child does not appear to result in any adverse effects.87 Immunity is achieved even if the child is exposed to IBD therapies through breast milk.88

Developmental milestones

Infant exposure to biologics and thiopurines has not been shown to result in any developmental delays. The PIANO study measured developmental milestones at 48 months from birth and found no differences when compared with validated population norms.39 A separate study observing childhood development up to 7 years of age in patients born to mothers with IBD found similar cognitive scores and motor development when compared with those born to mothers without IBD.89

Conclusion

Women considering conception should be optimized prior to pregnancy and maintained on appropriate medications throughout pregnancy and lactation to achieve a healthy pregnancy for both mother and baby. To date, biologics and thiopurines are not associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes. More data are needed for small molecules.

Dr. Chugh is an advanced inflammatory bowel disease fellow in the division of gastroenterology at the University of California San Francisco. Dr. Mahadevan is professor of medicine and codirector at the Center for Colitis and Crohn’s Disease in the division of gastroenterology at the University of California San Francisco. Dr. Mahadevan has potential conflicts related to AbbVie, Janssen, BMS, Takeda, Pfizer, Lilly, Gilead, Arena, and Prometheus Biosciences.

References

1. Ye Y et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2020;26:619-25.

2. Sykora J et al. World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24:2741-63.

3. Murakami Y et al. J Gastroenterol 2019;54:1070-7.

4. Hashash JG and Kane S. Gastroenterol Hepatol. (N Y) 2015;11:96-102.

5. Miller JP. J R Soc Med. 1986;79:221-5.

6. Cornish J et al. Gut. 2007;56:830-7.

7. Leung KK et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2021;27:550-62.

8. O’Toole A et al. Dig Dis Sci. 2015;60:2750-61.

9. Nguyen GC et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;14:1105-11.

10. Lee HH et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2020;51:861-9.

11. Kim MA et al. J Crohns Colitis. 2021;15:719-32.

12. Conradt E et al. Pediatrics. 2019;144.

13. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 762: Prepregnancy Counseling. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:e78-e89.

14. Farraye FA et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112:241-58.

15. Lee S et al. J Crohns Colitis. 2018;12:702-9.

16. Mahadevan U et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2019;25:627-41.

17. Ward MG et al. Inflamm. Bowel Dis 2015;21:2839-47.

18. Battat R et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014;20:1120-8.

19. Pedersen N et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;38:501-12.

20. Annese V. Pharmacol Res. 2020;159:104892.

21. Bennett RA et al. Gastroenterology. 1991;100:1638-43.

22. Turpin W et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2018;24:1133-48.

23. de Lima A et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:1285-92 e1.

24. Selinger C et al. Frontline Gastroenterol. 2021;12:182-7.

25. Mahadevan U et al. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:1106-12.

26. Hatch Q et al. Dis Colon Rectum. 2014;57:174-8.

27. Foulon A et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23:712-20.

28. Norgard B et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1947-54.

29. Broms G et al. Scand J Gastroenterol 2016;51:1462-9.

30. Meyer A et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2020;52:1480-90.

31. Kammerlander H et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23:1011-8.

32. Tandon P et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2019;53:574-81.

33. Kammerlander H et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2018;24:839-48.

34. Julsgaard M et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23:1240-6.

35. Ko MS et al. Dig Dis Sci. 2020;65:2979-85.

36. Cappell MS et al. J Reprod Med. 2010;55:115-23.

37. Committee ASoP et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;76:18-24.

38. Aboubakr A et al. Dig Dis Sci. 2021;66:1829-35.

39. Mahadevan U et al. Gastroenterology. 2021;160:1131-9.

40. Diav-Citrin O et al. Gastroenterology. 1998;114:23-8.

41. Rahimi R et al. Reprod Toxicol. 2008;25:271-5.

42. Norgard B et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2001;15:483-6.

43. Leung YP et al. J Crohns Colitis. 2015;9:223-30.

44. Schulze H et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;40:991-1008.

45. Szymanska E et al. J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod. 2021;50:101777.

46. Weber-Schoendorfer C et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66:1101-10.

47. Nielsen OH et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 Jan;20(1):74-87.e3.

48. Coelho J et al. Gut. 2011;60:198-203.

49. Sheikh M et al. J Crohns Colitis. 2015;9:680-4.

50. Kanis SL et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15:1232-41 e1.

51. Mahadevan U et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2018;24:2494-500.

52. Rosen MH et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2020;26:971-3.

53. Porter C et al. J Reprod Immunol. 2016;116:7-12.

54. Mahadevan U et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:286-92; quiz e24.

55. Picardo S and Seow CH. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2020;44-5:101670.

56. Flanagan E et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2020;52:1551-62.

57. Singh S et al. Gastroenterology. 2021;160:2512-56 e9.

58. de Lima A et al. Gut. 2016;65:1261-8.

59. Julsgaard M et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2020;26:93-102.

60. Wils P et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2021;53:460-70.

61. Mahadevan U et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017;45:941-50.

62. Bar-Gil Shitrit A et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2019;114:1172-5.

63. Klenske E et al. J Crohns Colitis. 2019;13:267-9.

64. Matro R et al. Gastroenterology. 2018;155:696-704.

65. Feuerstein JD et al. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:1450-61.

66. Sandborn WJ et al. J Crohns Colitis. 2021 Jul 5;15(7):1120-1129.

67. Lamb CA et al. Gut. 2019;68:s1-s106.

68. Nguyen GC et al. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:734-57 e1.

69. Ravid A et al. Dis Colon Rectum. 2002;45:1283-8.

70. Seligman NS et al. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2011;24:525-30.

71. Kim YH et al. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019;98:e17309.

72. Hansen AT et al. J Thromb Haemost. 2017;15:702-8.

73. Bates SM et al. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2016;41:92-128.

74. Bennett A et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2021 May 17;izab104.

75. Yu A et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2020;26:1926-32.

76. Mahadevan U et al. Gastroenterology. 2017;152:451-62 e2.

77. Long MD et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2016;50:152-6.

78. Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed). 2006 ed. Bethesda, MD: National Library of Medicine (US), 2006-2021.

79. Khalili H et al. Gut. 2013;62:1153-9.

80. Long MD and Hutfless S. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:1518-20.

81. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. U S. Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59:1-86.

82. Angelberger S et al. J Crohns Colitis. 2011;5:95-100.

83. Vestergaard T et al. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2018;53:1459-62.

84. Beaulieu DB et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15:25-8.

85. Anderson PO. Breastfeed Med. 2017;12:199-201.

86. Wodi AP et al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:189-92.

87. Chiarella-Redfern H et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2022 Jan 5;28(1):79-86.

88. Beaulieu DB et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16:99-105.

89. Friedman S et al. J Crohns Colitis. 2020 Dec 2;14(12):1709-1716.

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) incidence is rising globally.1-3 In the United States, we have seen a 123% increase in prevalence of IBD among adults and a 133% increase among children from 2007 to 2016, with an annual percentage change of 9.9%.1 The rise of IBD in young people, and the overall higher prevalence in women compared with men, make pregnancy and IBD a topic of increasing importance for gastroenterologists.1 Here, we will discuss management and expectations in women with IBD before conception, during pregnancy, and post partum.

Preconception

Disease activity

Achieving both clinical and endoscopic remission of disease prior to conception is the key to ensuring the best maternal and fetal outcomes. Patients with IBD who conceive while in remission remain in remission 80% of the time.4,5 On the other hand, those who conceive while their disease is active may continue to have active or worsening disease in nearly 70% of cases.4 Active disease has been associated with an increased incidence of preterm birth, low birth weight, and small-for-gestational-age birth.6-8 Active disease can also exacerbate malnutrition and result in poor maternal weight gain, which is associated with intrauterine growth restriction.9,7 Pregnancy outcomes in patients with IBD and quiescent disease are similar to those in the general population.10,11

Health care maintenance

Optimizing maternal health prior to conception is critical. Alcohol, tobacco, recreational drugs, and marijuana should all be avoided. Opioids should be tapered off prior to conception, as continued use may result in neonatal opioid withdrawal syndrome and long-term neurodevelopmental consequences.12,13 In addition, aiming for a healthy body mass index between 18 and 25 months prior to conception allows for better overall pregnancy outcomes.13 Appropriate cancer screening includes colon cancer screening in those with more than 8 years of colitis, regular pap smear for cervical cancer, and annual total body skin cancer examinations for patients on thiopurines and biologic therapies.14

Nutrition

Folic acid supplementation with at least 400 micrograms (mcg) daily is necessary for all women planning pregnancy. Patients with small bowel involvement or history of small bowel resection should have a folate intake of a minimum of 2 grams per day. Adequate vitamin D levels (at least 20 ng/mL) are recommended in all women with IBD. Those with malabsorption should be screened for deficiencies in vitamin B12, folate, and iron.13 These nutritional markers should be evaluated prepregnancy, during the first trimester, and thereafter as needed.15-18

Preconception counseling

Steroid-free remission for at least 3 months prior to conception is recommended and is associated with reduced risk of flare during pregnancy.16,19 IBD medications needed to control disease activity are generally safe preconception and during pregnancy, with some exception (Table).

Misconceptions regarding heritability of IBD have sometimes discouraged men and women from having children. While genetics may increase susceptibility, environmental and other factors are involved as well. The concordance rates for monozygotic twins range from 33.3%-58.3% for Crohn’s disease and 13.4%-27.9% for ulcerative colitis (UC).20 The risk of a child developing IBD is higher in those who have multiple relatives with IBD and whose parents had IBD at the time of conception.21 While genetic testing for IBD loci is available, it is not commonly performed at this time as many genes are involved.22

Pregnancy

Coordinated care

A complete team of specialists with coordinated care among all providers is needed for optimal maternal and fetal outcomes.23,24 A gastroenterologist, ideally an IBD specialist, should follow the patient throughout pregnancy, seeing the patient at least once during the first or second trimester and as needed during pregnancy.16 A high-risk obstetrician or maternal-fetal medicine specialist should be involved early in pregnancy, as well. Open communication among all disciplines ensures that a common message is conveyed to the patient.16,24 A nutritionist, mental health provider, and lactation specialist knowledgeable about IBD drugs may be of assistance, as well.16

Disease activity

While women with IBD are at increased risk of spontaneous abortion, preterm birth, and labor complications, this risk is mitigated by controlling disease activity.25 The risk of preterm birth, small-for-gestational-age birth, and delivery via C-section is much higher in women with moderate-to-high disease activity, compared with those with low disease activity.26 The presence of active perianal disease mandates C-section over vaginal delivery. Fourth-degree lacerations following vaginal delivery are most common among those patients with perianal disease.26,27 Stillbirths were shown to be increased only in those with active IBD when compared with non-IBD comparators and inactive IBD.28-31;11

Noninvasive methods for disease monitoring are preferred in pregnancy, but serum markers such as erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein may not be reliable in the pregnant patient (Figure).32 Fecal calprotectin does rise in correlation with disease activity, but exact thresholds have not been validated in pregnancy.33,34

An unsedated, unprepped flexible sigmoidoscopy can be safely performed throughout pregnancy.35 When there is a strong indication, a complete colonoscopy can be performed in the pregnant patient as well.36 Current American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) guidelines suggest placing the patient in the left lateral tilt position to avoid decreased maternal and placental perfusion via compression of the aorta or inferior vena cava and performing endoscopy during the second trimester, although trimester-specific timing is not always feasible by indication.37

Medication use and safety

IBD medications are a priority topic of concern among pregnant patients or those considering conception.38 Comprehensive data from the PIANO (Pregnancy in Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Neonatal Outcomes) registry has shown that most IBD drugs do not result in adverse pregnancy outcomes and should be continued.39 The use of biologics and thiopurines, either in combination or alone, is not related to an increased risk of congenital malformations, spontaneous abortion, preterm birth, low birth weight, or infections during the child’s first year of life.7,39 Developmental milestones also remain unaffected.39 Here, we will discuss safety considerations during pregnancy (see Table).

5-aminosalycylic acid. 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA) agents are generally low risk during pregnancy and should be continued.40-41 Sulfasalazine does interfere with folate metabolism, but by increasing folic acid supplementation to 2 grams per day, sulfasalazine can be continued throughout pregnancy, as well.42

Corticosteroids. Intrapartum corticosteroid use is associated with an increased risk of gestational diabetes and adrenal insufficiency when used long term.43-45 Short-term use may, however, be necessary to control an acute flare. The lowest dose for the shortest duration possible is recommended. Because of its high first-pass metabolism, budesonide is considered low risk in pregnancy.

Methotrexate. Methotrexate needs to be stopped at least 3 months prior to conception and should be avoided throughout pregnancy. Use during pregnancy can result in spontaneous abortions, as well as embryotoxicity.46

Thiopurines (6-mercaptopurine and azathioprine). Patients who are taking thiopurines prior to conception to maintain remission can continue to do so. Data on thiopurines from the PIANO registry has shown no increase in spontaneous abortions, congenital malformations, low birth weight, preterm birth, rates of infection in the child, or developmental delays.47-51

Calcineurin inhibitors (cyclosporine and tacrolimus). Calcineurin inhibitors are reserved for the management of acute severe UC. Safety data on calcineurin inhibitors is conflicting, and there is not enough information at this time to identify risk during pregnancy. Cyclosporine can be used for salvage therapy if absolutely needed, and there are case reports of its successful using during pregnancy.16,52

Biologic therapies. With the exception of certolizumab, all of the currently used biologics are actively transported across the placenta.39,53,54 Intrapartum use of biologic therapies does not worsen pregnancy or neonatal outcomes, including the risk for intensive care unit admission, infections, and developmental milestones.39,47

While drug concentrations may vary slightly during pregnancy, these changes are not substantial enough to warrant more frequent monitoring or dose adjustments, and prepregnancy weight should be used for dosing.55,56

Antitumor necrosis factor agents used in IBD include infliximab, adalimumab, certolizumab, and golimumab.57 All are low risk for pregnant patients and their offspring. Dosage timings can be adjusted, but not stopped, to minimize exposure to the child; however, it cannot be adjusted for certolizumab pegol because of its lack of placental transfer.58-59

Natalizumab and vedolizumab are integrin receptor antagonists and are also low risk in pregnancy.57;60-62;39

Ustekinumab, an interleukin-12/23 antagonist, can be found in infant serum and cord blood, as well. Health outcomes are similar in the exposed mother and child, however, compared with those of the general population.39;63-64

Small molecule drugs. Unlike monoclonal antibodies, which do not cross the placenta in large amounts until early in the second trimester, small molecules can cross in the first trimester during the critical period of organogenesis.

The two small molecule agents currently approved for use in UC are tofacitinib, a janus kinase inhibitor, and ozanimod, a sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor agonist.65-66 Further data are still needed to make recommendations on the use of tofacitinib and ozanimod in pregnancy. At this time, we recommend weighing the risks (unknown risk to human pregnancy) vs. benefits (controlled disease activity with clear risk of harm to mother and baby from flare) in the individual patient before counseling on use in pregnancy.

Delivery

Mode of delivery

The mode of delivery should be determined by the obstetrician. C-section is recommended for patients with active perianal disease or, in some cases, a history of ileal pouch anal anastomosis (IPAA).67-68 Vaginal delivery in the setting of perianal disease has been shown to increase the risk of fourth-degree laceration and anal sphincter dysfunction in the future.26-27 Anorectal motility may be impacted by IPAA construction and vaginal delivery independently of each other. It is therefore suggested that vaginal delivery be avoided in patients with a history of IPAA to avoid compounding the risk. Some studies do not show clear harm from vaginal delivery in the setting of IPAA, however, and informed decision making among all stakeholders should be had.27;69-70

Anticoagulation

The incidence of venous thromboembolism (VTE) is elevated in patients with IBD during pregnancy, and up to 12 weeks postpartum, compared with pregnant patients without IBD.71-72 VTE for prophylaxis is indicated in the pregnant patient while hospitalized and potentially thereafter depending on the patient’s risk factors, which may include obesity, prior personal history of VTE, heart failure, and prolonged immobility. Unfractionated heparin, low molecular weight heparin, and warfarin are safe for breastfeeding women.16,73

Postpartum care of mother

There is a risk of postpartum flare, occurring in about one third of patients in the first 6 months postpartum.74-75 De-escalating therapy during delivery or immediately postpartum is a predictor of a postpartum flare.75 If no infection is present and the timing interval is appropriate, biologic therapies should be continued and can be resumed 24 hours after a vaginal delivery and 48 hours after a C-section.16,76

NSAIDs and opioids can be used for pain relief but should be avoided in the long-term to prevent flares (NSAIDs) and infant sedation (associated with opioids) when used while breastfeeding.77 The LactMed database is an excellent resource for clarification on risk of medication use while breastfeeding.78

In particular, contraception should be addressed postpartum. Exogenous estrogen use increases the risk of VTE, which is already increased in IBD; nonestrogen containing, long-acting reversible contraception is preferred.79-80 Progestin-only implants or intrauterine devices may be used first line. The efficacy of oral contraceptives is theoretically reduced in those with rapid bowel transit, active small bowel inflammation, and prior small bowel resection, so adding another form of contraception is recommended.16,81

Source: American Gastroenterological Association

Postdelivery care of baby

Breastfeeding

Guidelines regarding medication use during breastfeeding are similar to those in pregnancy (see Table). Breastfeeding on biologics and thiopurines can continue without interruption in the child. Thiopurine concentrations in breast milk are low or undetectable.82,78 TNF receptor antagonists, anti-integrin therapies, and ustekinumab are found in low to undetectable levels in breast milk, as well.78

On the other hand, the active metabolite of methotrexate is detectable in breast milk and most sources recommend not breastfeeding on methotrexate. At doses used in IBD (15-25 milligrams per week), some experts have suggested avoiding breastfeeding for 24 hours following a dose.57,78 It is the practice of this author to recommend not breastfeeding at all on methotrexate.

5-ASA therapies are low risk for breastfeeding, but alternatives to sulfasalazine are preferred. The sulfapyridine metabolite transfers to breast milk and may cause hemolysis in infants born with a glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency.78

With regards to calcineurin inhibitors, tacrolimus appears in breast milk in low quantities, while cyclosporine levels are variable. Data from the National Transplantation Pregnancy Registry suggest that these medications can be used at the time of breastfeeding with close monitoring.78

There is not enough data on small molecule therapies at this time to support breastfeeding safety, and it is our practice to not recommend breastfeeding in this scenario.

The transfer of steroids to the child via breast milk does occur but at subtherapeutic levels.16 Budesonide has high first pass metabolism and is low risk during breastfeeding.83-84 As far as is known, IBD maintenance medications do not suppress lactation. The use of intravenous corticosteroids can, however, temporarily decrease milk production.16,85

Vaccines

Vaccination of infants can proceed as indicated by the Center for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines, with one exception. If the child’s mother was exposed to any biologic agents (not including certolizumab) during the third trimester, any live vaccines should be withheld in the first 6 months of life. In the United States, this restriction currently only applies to the rotavirus vaccine, which is administered starting at the age of 2 months.16,86 Notably, inadvertent administration of the rotavirus vaccine in the biologic-exposed child does not appear to result in any adverse effects.87 Immunity is achieved even if the child is exposed to IBD therapies through breast milk.88

Developmental milestones

Infant exposure to biologics and thiopurines has not been shown to result in any developmental delays. The PIANO study measured developmental milestones at 48 months from birth and found no differences when compared with validated population norms.39 A separate study observing childhood development up to 7 years of age in patients born to mothers with IBD found similar cognitive scores and motor development when compared with those born to mothers without IBD.89

Conclusion

Women considering conception should be optimized prior to pregnancy and maintained on appropriate medications throughout pregnancy and lactation to achieve a healthy pregnancy for both mother and baby. To date, biologics and thiopurines are not associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes. More data are needed for small molecules.

Dr. Chugh is an advanced inflammatory bowel disease fellow in the division of gastroenterology at the University of California San Francisco. Dr. Mahadevan is professor of medicine and codirector at the Center for Colitis and Crohn’s Disease in the division of gastroenterology at the University of California San Francisco. Dr. Mahadevan has potential conflicts related to AbbVie, Janssen, BMS, Takeda, Pfizer, Lilly, Gilead, Arena, and Prometheus Biosciences.

References

1. Ye Y et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2020;26:619-25.

2. Sykora J et al. World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24:2741-63.

3. Murakami Y et al. J Gastroenterol 2019;54:1070-7.

4. Hashash JG and Kane S. Gastroenterol Hepatol. (N Y) 2015;11:96-102.

5. Miller JP. J R Soc Med. 1986;79:221-5.

6. Cornish J et al. Gut. 2007;56:830-7.

7. Leung KK et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2021;27:550-62.

8. O’Toole A et al. Dig Dis Sci. 2015;60:2750-61.

9. Nguyen GC et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;14:1105-11.

10. Lee HH et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2020;51:861-9.

11. Kim MA et al. J Crohns Colitis. 2021;15:719-32.

12. Conradt E et al. Pediatrics. 2019;144.

13. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 762: Prepregnancy Counseling. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:e78-e89.

14. Farraye FA et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112:241-58.

15. Lee S et al. J Crohns Colitis. 2018;12:702-9.

16. Mahadevan U et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2019;25:627-41.

17. Ward MG et al. Inflamm. Bowel Dis 2015;21:2839-47.

18. Battat R et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014;20:1120-8.

19. Pedersen N et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;38:501-12.

20. Annese V. Pharmacol Res. 2020;159:104892.

21. Bennett RA et al. Gastroenterology. 1991;100:1638-43.

22. Turpin W et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2018;24:1133-48.

23. de Lima A et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:1285-92 e1.

24. Selinger C et al. Frontline Gastroenterol. 2021;12:182-7.

25. Mahadevan U et al. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:1106-12.

26. Hatch Q et al. Dis Colon Rectum. 2014;57:174-8.

27. Foulon A et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23:712-20.

28. Norgard B et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1947-54.

29. Broms G et al. Scand J Gastroenterol 2016;51:1462-9.

30. Meyer A et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2020;52:1480-90.

31. Kammerlander H et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23:1011-8.

32. Tandon P et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2019;53:574-81.

33. Kammerlander H et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2018;24:839-48.

34. Julsgaard M et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23:1240-6.

35. Ko MS et al. Dig Dis Sci. 2020;65:2979-85.

36. Cappell MS et al. J Reprod Med. 2010;55:115-23.

37. Committee ASoP et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;76:18-24.

38. Aboubakr A et al. Dig Dis Sci. 2021;66:1829-35.

39. Mahadevan U et al. Gastroenterology. 2021;160:1131-9.

40. Diav-Citrin O et al. Gastroenterology. 1998;114:23-8.

41. Rahimi R et al. Reprod Toxicol. 2008;25:271-5.

42. Norgard B et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2001;15:483-6.

43. Leung YP et al. J Crohns Colitis. 2015;9:223-30.

44. Schulze H et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;40:991-1008.

45. Szymanska E et al. J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod. 2021;50:101777.

46. Weber-Schoendorfer C et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66:1101-10.

47. Nielsen OH et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 Jan;20(1):74-87.e3.

48. Coelho J et al. Gut. 2011;60:198-203.

49. Sheikh M et al. J Crohns Colitis. 2015;9:680-4.

50. Kanis SL et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15:1232-41 e1.

51. Mahadevan U et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2018;24:2494-500.

52. Rosen MH et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2020;26:971-3.

53. Porter C et al. J Reprod Immunol. 2016;116:7-12.

54. Mahadevan U et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:286-92; quiz e24.

55. Picardo S and Seow CH. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2020;44-5:101670.

56. Flanagan E et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2020;52:1551-62.

57. Singh S et al. Gastroenterology. 2021;160:2512-56 e9.

58. de Lima A et al. Gut. 2016;65:1261-8.

59. Julsgaard M et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2020;26:93-102.

60. Wils P et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2021;53:460-70.

61. Mahadevan U et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017;45:941-50.

62. Bar-Gil Shitrit A et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2019;114:1172-5.

63. Klenske E et al. J Crohns Colitis. 2019;13:267-9.

64. Matro R et al. Gastroenterology. 2018;155:696-704.

65. Feuerstein JD et al. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:1450-61.

66. Sandborn WJ et al. J Crohns Colitis. 2021 Jul 5;15(7):1120-1129.

67. Lamb CA et al. Gut. 2019;68:s1-s106.

68. Nguyen GC et al. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:734-57 e1.

69. Ravid A et al. Dis Colon Rectum. 2002;45:1283-8.

70. Seligman NS et al. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2011;24:525-30.

71. Kim YH et al. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019;98:e17309.

72. Hansen AT et al. J Thromb Haemost. 2017;15:702-8.

73. Bates SM et al. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2016;41:92-128.

74. Bennett A et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2021 May 17;izab104.

75. Yu A et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2020;26:1926-32.

76. Mahadevan U et al. Gastroenterology. 2017;152:451-62 e2.

77. Long MD et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2016;50:152-6.

78. Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed). 2006 ed. Bethesda, MD: National Library of Medicine (US), 2006-2021.

79. Khalili H et al. Gut. 2013;62:1153-9.

80. Long MD and Hutfless S. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:1518-20.

81. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. U S. Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59:1-86.

82. Angelberger S et al. J Crohns Colitis. 2011;5:95-100.

83. Vestergaard T et al. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2018;53:1459-62.

84. Beaulieu DB et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15:25-8.

85. Anderson PO. Breastfeed Med. 2017;12:199-201.

86. Wodi AP et al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:189-92.

87. Chiarella-Redfern H et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2022 Jan 5;28(1):79-86.

88. Beaulieu DB et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16:99-105.

89. Friedman S et al. J Crohns Colitis. 2020 Dec 2;14(12):1709-1716.

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) incidence is rising globally.1-3 In the United States, we have seen a 123% increase in prevalence of IBD among adults and a 133% increase among children from 2007 to 2016, with an annual percentage change of 9.9%.1 The rise of IBD in young people, and the overall higher prevalence in women compared with men, make pregnancy and IBD a topic of increasing importance for gastroenterologists.1 Here, we will discuss management and expectations in women with IBD before conception, during pregnancy, and post partum.

Preconception

Disease activity

Achieving both clinical and endoscopic remission of disease prior to conception is the key to ensuring the best maternal and fetal outcomes. Patients with IBD who conceive while in remission remain in remission 80% of the time.4,5 On the other hand, those who conceive while their disease is active may continue to have active or worsening disease in nearly 70% of cases.4 Active disease has been associated with an increased incidence of preterm birth, low birth weight, and small-for-gestational-age birth.6-8 Active disease can also exacerbate malnutrition and result in poor maternal weight gain, which is associated with intrauterine growth restriction.9,7 Pregnancy outcomes in patients with IBD and quiescent disease are similar to those in the general population.10,11

Health care maintenance

Optimizing maternal health prior to conception is critical. Alcohol, tobacco, recreational drugs, and marijuana should all be avoided. Opioids should be tapered off prior to conception, as continued use may result in neonatal opioid withdrawal syndrome and long-term neurodevelopmental consequences.12,13 In addition, aiming for a healthy body mass index between 18 and 25 months prior to conception allows for better overall pregnancy outcomes.13 Appropriate cancer screening includes colon cancer screening in those with more than 8 years of colitis, regular pap smear for cervical cancer, and annual total body skin cancer examinations for patients on thiopurines and biologic therapies.14

Nutrition

Folic acid supplementation with at least 400 micrograms (mcg) daily is necessary for all women planning pregnancy. Patients with small bowel involvement or history of small bowel resection should have a folate intake of a minimum of 2 grams per day. Adequate vitamin D levels (at least 20 ng/mL) are recommended in all women with IBD. Those with malabsorption should be screened for deficiencies in vitamin B12, folate, and iron.13 These nutritional markers should be evaluated prepregnancy, during the first trimester, and thereafter as needed.15-18

Preconception counseling

Steroid-free remission for at least 3 months prior to conception is recommended and is associated with reduced risk of flare during pregnancy.16,19 IBD medications needed to control disease activity are generally safe preconception and during pregnancy, with some exception (Table).

Misconceptions regarding heritability of IBD have sometimes discouraged men and women from having children. While genetics may increase susceptibility, environmental and other factors are involved as well. The concordance rates for monozygotic twins range from 33.3%-58.3% for Crohn’s disease and 13.4%-27.9% for ulcerative colitis (UC).20 The risk of a child developing IBD is higher in those who have multiple relatives with IBD and whose parents had IBD at the time of conception.21 While genetic testing for IBD loci is available, it is not commonly performed at this time as many genes are involved.22

Pregnancy

Coordinated care

A complete team of specialists with coordinated care among all providers is needed for optimal maternal and fetal outcomes.23,24 A gastroenterologist, ideally an IBD specialist, should follow the patient throughout pregnancy, seeing the patient at least once during the first or second trimester and as needed during pregnancy.16 A high-risk obstetrician or maternal-fetal medicine specialist should be involved early in pregnancy, as well. Open communication among all disciplines ensures that a common message is conveyed to the patient.16,24 A nutritionist, mental health provider, and lactation specialist knowledgeable about IBD drugs may be of assistance, as well.16

Disease activity

While women with IBD are at increased risk of spontaneous abortion, preterm birth, and labor complications, this risk is mitigated by controlling disease activity.25 The risk of preterm birth, small-for-gestational-age birth, and delivery via C-section is much higher in women with moderate-to-high disease activity, compared with those with low disease activity.26 The presence of active perianal disease mandates C-section over vaginal delivery. Fourth-degree lacerations following vaginal delivery are most common among those patients with perianal disease.26,27 Stillbirths were shown to be increased only in those with active IBD when compared with non-IBD comparators and inactive IBD.28-31;11

Noninvasive methods for disease monitoring are preferred in pregnancy, but serum markers such as erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein may not be reliable in the pregnant patient (Figure).32 Fecal calprotectin does rise in correlation with disease activity, but exact thresholds have not been validated in pregnancy.33,34

An unsedated, unprepped flexible sigmoidoscopy can be safely performed throughout pregnancy.35 When there is a strong indication, a complete colonoscopy can be performed in the pregnant patient as well.36 Current American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) guidelines suggest placing the patient in the left lateral tilt position to avoid decreased maternal and placental perfusion via compression of the aorta or inferior vena cava and performing endoscopy during the second trimester, although trimester-specific timing is not always feasible by indication.37

Medication use and safety

IBD medications are a priority topic of concern among pregnant patients or those considering conception.38 Comprehensive data from the PIANO (Pregnancy in Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Neonatal Outcomes) registry has shown that most IBD drugs do not result in adverse pregnancy outcomes and should be continued.39 The use of biologics and thiopurines, either in combination or alone, is not related to an increased risk of congenital malformations, spontaneous abortion, preterm birth, low birth weight, or infections during the child’s first year of life.7,39 Developmental milestones also remain unaffected.39 Here, we will discuss safety considerations during pregnancy (see Table).

5-aminosalycylic acid. 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA) agents are generally low risk during pregnancy and should be continued.40-41 Sulfasalazine does interfere with folate metabolism, but by increasing folic acid supplementation to 2 grams per day, sulfasalazine can be continued throughout pregnancy, as well.42

Corticosteroids. Intrapartum corticosteroid use is associated with an increased risk of gestational diabetes and adrenal insufficiency when used long term.43-45 Short-term use may, however, be necessary to control an acute flare. The lowest dose for the shortest duration possible is recommended. Because of its high first-pass metabolism, budesonide is considered low risk in pregnancy.

Methotrexate. Methotrexate needs to be stopped at least 3 months prior to conception and should be avoided throughout pregnancy. Use during pregnancy can result in spontaneous abortions, as well as embryotoxicity.46

Thiopurines (6-mercaptopurine and azathioprine). Patients who are taking thiopurines prior to conception to maintain remission can continue to do so. Data on thiopurines from the PIANO registry has shown no increase in spontaneous abortions, congenital malformations, low birth weight, preterm birth, rates of infection in the child, or developmental delays.47-51

Calcineurin inhibitors (cyclosporine and tacrolimus). Calcineurin inhibitors are reserved for the management of acute severe UC. Safety data on calcineurin inhibitors is conflicting, and there is not enough information at this time to identify risk during pregnancy. Cyclosporine can be used for salvage therapy if absolutely needed, and there are case reports of its successful using during pregnancy.16,52

Biologic therapies. With the exception of certolizumab, all of the currently used biologics are actively transported across the placenta.39,53,54 Intrapartum use of biologic therapies does not worsen pregnancy or neonatal outcomes, including the risk for intensive care unit admission, infections, and developmental milestones.39,47

While drug concentrations may vary slightly during pregnancy, these changes are not substantial enough to warrant more frequent monitoring or dose adjustments, and prepregnancy weight should be used for dosing.55,56

Antitumor necrosis factor agents used in IBD include infliximab, adalimumab, certolizumab, and golimumab.57 All are low risk for pregnant patients and their offspring. Dosage timings can be adjusted, but not stopped, to minimize exposure to the child; however, it cannot be adjusted for certolizumab pegol because of its lack of placental transfer.58-59

Natalizumab and vedolizumab are integrin receptor antagonists and are also low risk in pregnancy.57;60-62;39

Ustekinumab, an interleukin-12/23 antagonist, can be found in infant serum and cord blood, as well. Health outcomes are similar in the exposed mother and child, however, compared with those of the general population.39;63-64

Small molecule drugs. Unlike monoclonal antibodies, which do not cross the placenta in large amounts until early in the second trimester, small molecules can cross in the first trimester during the critical period of organogenesis.

The two small molecule agents currently approved for use in UC are tofacitinib, a janus kinase inhibitor, and ozanimod, a sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor agonist.65-66 Further data are still needed to make recommendations on the use of tofacitinib and ozanimod in pregnancy. At this time, we recommend weighing the risks (unknown risk to human pregnancy) vs. benefits (controlled disease activity with clear risk of harm to mother and baby from flare) in the individual patient before counseling on use in pregnancy.

Delivery

Mode of delivery

The mode of delivery should be determined by the obstetrician. C-section is recommended for patients with active perianal disease or, in some cases, a history of ileal pouch anal anastomosis (IPAA).67-68 Vaginal delivery in the setting of perianal disease has been shown to increase the risk of fourth-degree laceration and anal sphincter dysfunction in the future.26-27 Anorectal motility may be impacted by IPAA construction and vaginal delivery independently of each other. It is therefore suggested that vaginal delivery be avoided in patients with a history of IPAA to avoid compounding the risk. Some studies do not show clear harm from vaginal delivery in the setting of IPAA, however, and informed decision making among all stakeholders should be had.27;69-70

Anticoagulation

The incidence of venous thromboembolism (VTE) is elevated in patients with IBD during pregnancy, and up to 12 weeks postpartum, compared with pregnant patients without IBD.71-72 VTE for prophylaxis is indicated in the pregnant patient while hospitalized and potentially thereafter depending on the patient’s risk factors, which may include obesity, prior personal history of VTE, heart failure, and prolonged immobility. Unfractionated heparin, low molecular weight heparin, and warfarin are safe for breastfeeding women.16,73

Postpartum care of mother

There is a risk of postpartum flare, occurring in about one third of patients in the first 6 months postpartum.74-75 De-escalating therapy during delivery or immediately postpartum is a predictor of a postpartum flare.75 If no infection is present and the timing interval is appropriate, biologic therapies should be continued and can be resumed 24 hours after a vaginal delivery and 48 hours after a C-section.16,76

NSAIDs and opioids can be used for pain relief but should be avoided in the long-term to prevent flares (NSAIDs) and infant sedation (associated with opioids) when used while breastfeeding.77 The LactMed database is an excellent resource for clarification on risk of medication use while breastfeeding.78

In particular, contraception should be addressed postpartum. Exogenous estrogen use increases the risk of VTE, which is already increased in IBD; nonestrogen containing, long-acting reversible contraception is preferred.79-80 Progestin-only implants or intrauterine devices may be used first line. The efficacy of oral contraceptives is theoretically reduced in those with rapid bowel transit, active small bowel inflammation, and prior small bowel resection, so adding another form of contraception is recommended.16,81

Source: American Gastroenterological Association

Postdelivery care of baby

Breastfeeding

Guidelines regarding medication use during breastfeeding are similar to those in pregnancy (see Table). Breastfeeding on biologics and thiopurines can continue without interruption in the child. Thiopurine concentrations in breast milk are low or undetectable.82,78 TNF receptor antagonists, anti-integrin therapies, and ustekinumab are found in low to undetectable levels in breast milk, as well.78

On the other hand, the active metabolite of methotrexate is detectable in breast milk and most sources recommend not breastfeeding on methotrexate. At doses used in IBD (15-25 milligrams per week), some experts have suggested avoiding breastfeeding for 24 hours following a dose.57,78 It is the practice of this author to recommend not breastfeeding at all on methotrexate.

5-ASA therapies are low risk for breastfeeding, but alternatives to sulfasalazine are preferred. The sulfapyridine metabolite transfers to breast milk and may cause hemolysis in infants born with a glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency.78

With regards to calcineurin inhibitors, tacrolimus appears in breast milk in low quantities, while cyclosporine levels are variable. Data from the National Transplantation Pregnancy Registry suggest that these medications can be used at the time of breastfeeding with close monitoring.78

There is not enough data on small molecule therapies at this time to support breastfeeding safety, and it is our practice to not recommend breastfeeding in this scenario.

The transfer of steroids to the child via breast milk does occur but at subtherapeutic levels.16 Budesonide has high first pass metabolism and is low risk during breastfeeding.83-84 As far as is known, IBD maintenance medications do not suppress lactation. The use of intravenous corticosteroids can, however, temporarily decrease milk production.16,85

Vaccines

Vaccination of infants can proceed as indicated by the Center for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines, with one exception. If the child’s mother was exposed to any biologic agents (not including certolizumab) during the third trimester, any live vaccines should be withheld in the first 6 months of life. In the United States, this restriction currently only applies to the rotavirus vaccine, which is administered starting at the age of 2 months.16,86 Notably, inadvertent administration of the rotavirus vaccine in the biologic-exposed child does not appear to result in any adverse effects.87 Immunity is achieved even if the child is exposed to IBD therapies through breast milk.88

Developmental milestones

Infant exposure to biologics and thiopurines has not been shown to result in any developmental delays. The PIANO study measured developmental milestones at 48 months from birth and found no differences when compared with validated population norms.39 A separate study observing childhood development up to 7 years of age in patients born to mothers with IBD found similar cognitive scores and motor development when compared with those born to mothers without IBD.89

Conclusion

Women considering conception should be optimized prior to pregnancy and maintained on appropriate medications throughout pregnancy and lactation to achieve a healthy pregnancy for both mother and baby. To date, biologics and thiopurines are not associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes. More data are needed for small molecules.

Dr. Chugh is an advanced inflammatory bowel disease fellow in the division of gastroenterology at the University of California San Francisco. Dr. Mahadevan is professor of medicine and codirector at the Center for Colitis and Crohn’s Disease in the division of gastroenterology at the University of California San Francisco. Dr. Mahadevan has potential conflicts related to AbbVie, Janssen, BMS, Takeda, Pfizer, Lilly, Gilead, Arena, and Prometheus Biosciences.

References

1. Ye Y et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2020;26:619-25.

2. Sykora J et al. World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24:2741-63.

3. Murakami Y et al. J Gastroenterol 2019;54:1070-7.

4. Hashash JG and Kane S. Gastroenterol Hepatol. (N Y) 2015;11:96-102.

5. Miller JP. J R Soc Med. 1986;79:221-5.

6. Cornish J et al. Gut. 2007;56:830-7.

7. Leung KK et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2021;27:550-62.

8. O’Toole A et al. Dig Dis Sci. 2015;60:2750-61.

9. Nguyen GC et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;14:1105-11.

10. Lee HH et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2020;51:861-9.

11. Kim MA et al. J Crohns Colitis. 2021;15:719-32.

12. Conradt E et al. Pediatrics. 2019;144.

13. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 762: Prepregnancy Counseling. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:e78-e89.

14. Farraye FA et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112:241-58.

15. Lee S et al. J Crohns Colitis. 2018;12:702-9.

16. Mahadevan U et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2019;25:627-41.

17. Ward MG et al. Inflamm. Bowel Dis 2015;21:2839-47.

18. Battat R et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014;20:1120-8.

19. Pedersen N et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;38:501-12.

20. Annese V. Pharmacol Res. 2020;159:104892.

21. Bennett RA et al. Gastroenterology. 1991;100:1638-43.

22. Turpin W et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2018;24:1133-48.

23. de Lima A et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:1285-92 e1.

24. Selinger C et al. Frontline Gastroenterol. 2021;12:182-7.

25. Mahadevan U et al. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:1106-12.

26. Hatch Q et al. Dis Colon Rectum. 2014;57:174-8.

27. Foulon A et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23:712-20.

28. Norgard B et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1947-54.

29. Broms G et al. Scand J Gastroenterol 2016;51:1462-9.

30. Meyer A et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2020;52:1480-90.

31. Kammerlander H et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23:1011-8.

32. Tandon P et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2019;53:574-81.

33. Kammerlander H et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2018;24:839-48.

34. Julsgaard M et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23:1240-6.

35. Ko MS et al. Dig Dis Sci. 2020;65:2979-85.

36. Cappell MS et al. J Reprod Med. 2010;55:115-23.

37. Committee ASoP et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;76:18-24.

38. Aboubakr A et al. Dig Dis Sci. 2021;66:1829-35.

39. Mahadevan U et al. Gastroenterology. 2021;160:1131-9.

40. Diav-Citrin O et al. Gastroenterology. 1998;114:23-8.

41. Rahimi R et al. Reprod Toxicol. 2008;25:271-5.

42. Norgard B et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2001;15:483-6.

43. Leung YP et al. J Crohns Colitis. 2015;9:223-30.

44. Schulze H et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;40:991-1008.

45. Szymanska E et al. J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod. 2021;50:101777.

46. Weber-Schoendorfer C et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66:1101-10.

47. Nielsen OH et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 Jan;20(1):74-87.e3.

48. Coelho J et al. Gut. 2011;60:198-203.

49. Sheikh M et al. J Crohns Colitis. 2015;9:680-4.

50. Kanis SL et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15:1232-41 e1.

51. Mahadevan U et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2018;24:2494-500.

52. Rosen MH et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2020;26:971-3.

53. Porter C et al. J Reprod Immunol. 2016;116:7-12.

54. Mahadevan U et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:286-92; quiz e24.

55. Picardo S and Seow CH. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2020;44-5:101670.

56. Flanagan E et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2020;52:1551-62.

57. Singh S et al. Gastroenterology. 2021;160:2512-56 e9.

58. de Lima A et al. Gut. 2016;65:1261-8.

59. Julsgaard M et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2020;26:93-102.

60. Wils P et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2021;53:460-70.

61. Mahadevan U et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017;45:941-50.

62. Bar-Gil Shitrit A et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2019;114:1172-5.

63. Klenske E et al. J Crohns Colitis. 2019;13:267-9.

64. Matro R et al. Gastroenterology. 2018;155:696-704.

65. Feuerstein JD et al. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:1450-61.

66. Sandborn WJ et al. J Crohns Colitis. 2021 Jul 5;15(7):1120-1129.

67. Lamb CA et al. Gut. 2019;68:s1-s106.

68. Nguyen GC et al. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:734-57 e1.

69. Ravid A et al. Dis Colon Rectum. 2002;45:1283-8.

70. Seligman NS et al. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2011;24:525-30.

71. Kim YH et al. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019;98:e17309.

72. Hansen AT et al. J Thromb Haemost. 2017;15:702-8.

73. Bates SM et al. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2016;41:92-128.

74. Bennett A et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2021 May 17;izab104.

75. Yu A et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2020;26:1926-32.

76. Mahadevan U et al. Gastroenterology. 2017;152:451-62 e2.

77. Long MD et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2016;50:152-6.

78. Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed). 2006 ed. Bethesda, MD: National Library of Medicine (US), 2006-2021.

79. Khalili H et al. Gut. 2013;62:1153-9.

80. Long MD and Hutfless S. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:1518-20.

81. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. U S. Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59:1-86.

82. Angelberger S et al. J Crohns Colitis. 2011;5:95-100.

83. Vestergaard T et al. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2018;53:1459-62.

84. Beaulieu DB et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15:25-8.

85. Anderson PO. Breastfeed Med. 2017;12:199-201.

86. Wodi AP et al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:189-92.

87. Chiarella-Redfern H et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2022 Jan 5;28(1):79-86.

88. Beaulieu DB et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16:99-105.

89. Friedman S et al. J Crohns Colitis. 2020 Dec 2;14(12):1709-1716.