User login

Nevus Spilus: Is the Presence of Hair Associated With an Increased Risk for Melanoma?

The term nevus spilus (NS), also known as speckled lentiginous nevus, was first used in the 19th century to describe lesions with background café au lait–like lentiginous melanocytic hyperplasia speckled with small, 1- to 3-mm, darker foci. The dark spots reflect lentigines; junctional, compound, and intradermal nevus cell nests; and more rarely Spitz and blue nevi. Both macular and papular subtypes have been described.1 This birthmark is quite common, occurring in 1.3% to 2.3% of the adult population worldwide.2 Hypertrichosis has been described in NS.3-9 Two subsequent cases of malignant melanoma in hairy NS suggested that lesions may be particularly prone to malignant degeneration.4,8 We report an additional case of hairy NS that was not associated with melanoma and consider whether dermatologists should warn their patients about this association.

Case Report

A 26-year-old woman presented with a stable 7×8-cm, tan-brown, macular, pigmented birthmark studded with darker 1- to 2-mm, irregular, brown-black and blue, confettilike macules on the left proximal lateral thigh that had been present since birth (Figure 1). Dark terminal hairs were present, arising from both the darker and lighter pigmented areas but not the surrounding normal skin.

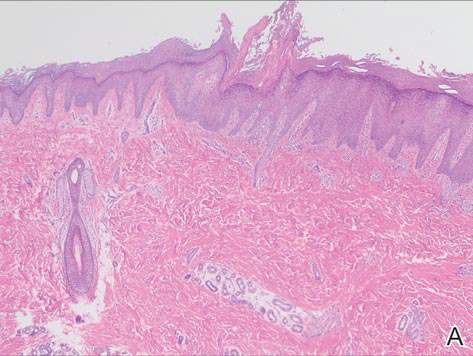

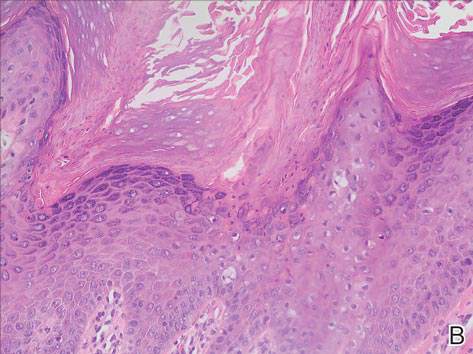

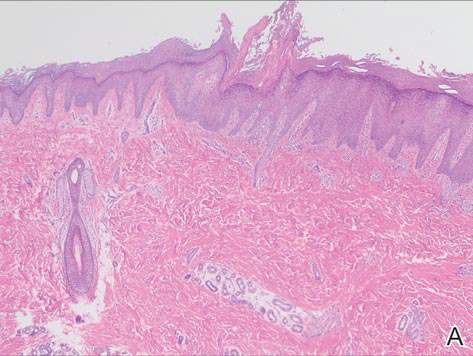

A 4-mm punch biopsy from one of the dark blue macules demonstrated uniform lentiginous melanocytic hyperplasia and nevus cell nests adjacent to the sweat glands extending into the mid dermis (Figure 2). No clinical evidence of malignant degeneration was present.

Comment

The risk for melanoma is increased in classic nonspeckled congenital nevi and the risk correlates with the size of the lesion and most probably the number of nevus cells in the lesion that increase the risk for a random mutation.8,10,11 It is likely that NS with or without hair presages a small increased risk for melanoma,6,9,12 which is not surprising because NS is a subtype of congenital melanocytic nevus (CMN), a condition that is present at birth and results from a proliferation of melanocytes.6 Nevus spilus, however, appears to have a notably lower risk for malignant degeneration than other classic CMN of the same size. The following support for this hypothesis is offered: First, CMN have nevus cells broadly filling the dermis that extend more deeply into the dermis than NS (Figure 2A).10 In our estimation, CMN have at least 100 times the number of nevus cells per square centimeter compared to NS. The potential for malignant degeneration of any one melanocyte is greater when more are present. Second, although some NS lesions evolve, classic CMN are universally more proliferative than NS.10,13 The involved skin in CMN thickens over time with increased numbers of melanocytes and marked overgrowth of adjacent tissue. Melanocytes in a proliferative phase may be more likely to undergo malignant degeneration.10

A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the search term nevus spilus and melanoma yielded 2 cases4,8 of melanoma arising among 15 cases of hairy NS in the literature, which led to the suggestion that the presence of hair could be associated with an increased risk for malignant degeneration in NS (Table). This apparent high incidence of melanoma most likely reflects referral/publication bias rather than a statistically significant association. In fact, the clinical lesion most clinically similar to hairy NS is Becker nevus, with tan macules demonstrating lentiginous melanocytic hyperplasia associated with numerous coarse terminal hairs. There is no indication that Becker nevi have a considerable premalignant potential, though one case of melanoma arising in a Becker nevus has been reported.9 There is no evidence to suggest that classic CMN with hypertrichosis has a greater premalignant potential than similar lesions without hypertrichosis.

We noticed the presence of hair in our patient’s lesion only after reports in the literature caused us to look for this phenomenon.9 This occurrence may actually be quite common. We do not recommend prophylactic excision of NS and believe the risk for malignant degeneration is low in NS with or without hair, though larger NS (>4 cm), especially giant, zosteriform, or segmental lesions, may have a greater risk.1,6,9,10 It is prudent for physicians to carefully examine NS and sample suspicious foci, especially when patients describe a lesion as changing.

- Vidaurri-de la Cruz H, Happle R. Two distinct types of speckled lentiginous nevi characterized by macular versus papular speckles. Dermatology. 2006;212:53-58.

- Ly L, Christie M, Swain S, et al. Melanoma(s) arising in large segmental speckled lentiginous nevi: a case series. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:1190-1193.

- Prose NS, Heilman E, Felman YM, et al. Multiple benign juvenile melanoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1983;9:236-242.

- Grinspan D, Casala A, Abulafia J, et al. Melanoma on dysplastic nevus spilus. Int J Dermatol. 1997;36:499-502 .

- Langenbach N, Pfau A, Landthaler M, et al. Naevi spili, café-au-lait spots and melanocytic naevi aggregated alongside Blaschko’s lines, with a review of segmental melanocytic lesions. Acta Derm Venereol. 1998;78:378-380.

- Schaffer JV, Orlow SJ, Lazova R, et al. Speckled lentiginous nevus: within the spectrum of congenital melanocytic nevi. Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:172-178.

- Saraswat A, Dogra S, Bansali A, et al. Phakomatosis pigmentokeratotica associated with hypophosphataemic vitamin D–resistant rickets: improvement in phosphate homeostasis after partial laser ablation. Br J Dermatol. 2003;148:1074-1076.

- Zeren-Bilgin

i , Gür S, Aydın O, et al. Melanoma arising in a hairy nevus spilus. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:1362-1364. - Singh S, Jain N, Khanna N, et al. Hairy nevus spilus: a case series. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:100-104.

- Price HN, Schaffer JV. Congenital melanocytic nevi—when to worry and how to treat: facts and controversies. Clin Dermatol. 2010;28:293-302.

- Alikhan Ali, Ibrahimi OA, Eisen DB. Congenital melanocytic nevi: where are we now? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:495.e1-495.e17.

- Haenssle HA, Kaune KM, Buhl T, et al. Melanoma arising in segmental nevus spilus: detection by sequential digital dermatoscopy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:337-341.

- Cohen LM. Nevus spilus: congenital or acquired? Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:215-216.

The term nevus spilus (NS), also known as speckled lentiginous nevus, was first used in the 19th century to describe lesions with background café au lait–like lentiginous melanocytic hyperplasia speckled with small, 1- to 3-mm, darker foci. The dark spots reflect lentigines; junctional, compound, and intradermal nevus cell nests; and more rarely Spitz and blue nevi. Both macular and papular subtypes have been described.1 This birthmark is quite common, occurring in 1.3% to 2.3% of the adult population worldwide.2 Hypertrichosis has been described in NS.3-9 Two subsequent cases of malignant melanoma in hairy NS suggested that lesions may be particularly prone to malignant degeneration.4,8 We report an additional case of hairy NS that was not associated with melanoma and consider whether dermatologists should warn their patients about this association.

Case Report

A 26-year-old woman presented with a stable 7×8-cm, tan-brown, macular, pigmented birthmark studded with darker 1- to 2-mm, irregular, brown-black and blue, confettilike macules on the left proximal lateral thigh that had been present since birth (Figure 1). Dark terminal hairs were present, arising from both the darker and lighter pigmented areas but not the surrounding normal skin.

A 4-mm punch biopsy from one of the dark blue macules demonstrated uniform lentiginous melanocytic hyperplasia and nevus cell nests adjacent to the sweat glands extending into the mid dermis (Figure 2). No clinical evidence of malignant degeneration was present.

Comment

The risk for melanoma is increased in classic nonspeckled congenital nevi and the risk correlates with the size of the lesion and most probably the number of nevus cells in the lesion that increase the risk for a random mutation.8,10,11 It is likely that NS with or without hair presages a small increased risk for melanoma,6,9,12 which is not surprising because NS is a subtype of congenital melanocytic nevus (CMN), a condition that is present at birth and results from a proliferation of melanocytes.6 Nevus spilus, however, appears to have a notably lower risk for malignant degeneration than other classic CMN of the same size. The following support for this hypothesis is offered: First, CMN have nevus cells broadly filling the dermis that extend more deeply into the dermis than NS (Figure 2A).10 In our estimation, CMN have at least 100 times the number of nevus cells per square centimeter compared to NS. The potential for malignant degeneration of any one melanocyte is greater when more are present. Second, although some NS lesions evolve, classic CMN are universally more proliferative than NS.10,13 The involved skin in CMN thickens over time with increased numbers of melanocytes and marked overgrowth of adjacent tissue. Melanocytes in a proliferative phase may be more likely to undergo malignant degeneration.10

A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the search term nevus spilus and melanoma yielded 2 cases4,8 of melanoma arising among 15 cases of hairy NS in the literature, which led to the suggestion that the presence of hair could be associated with an increased risk for malignant degeneration in NS (Table). This apparent high incidence of melanoma most likely reflects referral/publication bias rather than a statistically significant association. In fact, the clinical lesion most clinically similar to hairy NS is Becker nevus, with tan macules demonstrating lentiginous melanocytic hyperplasia associated with numerous coarse terminal hairs. There is no indication that Becker nevi have a considerable premalignant potential, though one case of melanoma arising in a Becker nevus has been reported.9 There is no evidence to suggest that classic CMN with hypertrichosis has a greater premalignant potential than similar lesions without hypertrichosis.

We noticed the presence of hair in our patient’s lesion only after reports in the literature caused us to look for this phenomenon.9 This occurrence may actually be quite common. We do not recommend prophylactic excision of NS and believe the risk for malignant degeneration is low in NS with or without hair, though larger NS (>4 cm), especially giant, zosteriform, or segmental lesions, may have a greater risk.1,6,9,10 It is prudent for physicians to carefully examine NS and sample suspicious foci, especially when patients describe a lesion as changing.

The term nevus spilus (NS), also known as speckled lentiginous nevus, was first used in the 19th century to describe lesions with background café au lait–like lentiginous melanocytic hyperplasia speckled with small, 1- to 3-mm, darker foci. The dark spots reflect lentigines; junctional, compound, and intradermal nevus cell nests; and more rarely Spitz and blue nevi. Both macular and papular subtypes have been described.1 This birthmark is quite common, occurring in 1.3% to 2.3% of the adult population worldwide.2 Hypertrichosis has been described in NS.3-9 Two subsequent cases of malignant melanoma in hairy NS suggested that lesions may be particularly prone to malignant degeneration.4,8 We report an additional case of hairy NS that was not associated with melanoma and consider whether dermatologists should warn their patients about this association.

Case Report

A 26-year-old woman presented with a stable 7×8-cm, tan-brown, macular, pigmented birthmark studded with darker 1- to 2-mm, irregular, brown-black and blue, confettilike macules on the left proximal lateral thigh that had been present since birth (Figure 1). Dark terminal hairs were present, arising from both the darker and lighter pigmented areas but not the surrounding normal skin.

A 4-mm punch biopsy from one of the dark blue macules demonstrated uniform lentiginous melanocytic hyperplasia and nevus cell nests adjacent to the sweat glands extending into the mid dermis (Figure 2). No clinical evidence of malignant degeneration was present.

Comment

The risk for melanoma is increased in classic nonspeckled congenital nevi and the risk correlates with the size of the lesion and most probably the number of nevus cells in the lesion that increase the risk for a random mutation.8,10,11 It is likely that NS with or without hair presages a small increased risk for melanoma,6,9,12 which is not surprising because NS is a subtype of congenital melanocytic nevus (CMN), a condition that is present at birth and results from a proliferation of melanocytes.6 Nevus spilus, however, appears to have a notably lower risk for malignant degeneration than other classic CMN of the same size. The following support for this hypothesis is offered: First, CMN have nevus cells broadly filling the dermis that extend more deeply into the dermis than NS (Figure 2A).10 In our estimation, CMN have at least 100 times the number of nevus cells per square centimeter compared to NS. The potential for malignant degeneration of any one melanocyte is greater when more are present. Second, although some NS lesions evolve, classic CMN are universally more proliferative than NS.10,13 The involved skin in CMN thickens over time with increased numbers of melanocytes and marked overgrowth of adjacent tissue. Melanocytes in a proliferative phase may be more likely to undergo malignant degeneration.10

A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the search term nevus spilus and melanoma yielded 2 cases4,8 of melanoma arising among 15 cases of hairy NS in the literature, which led to the suggestion that the presence of hair could be associated with an increased risk for malignant degeneration in NS (Table). This apparent high incidence of melanoma most likely reflects referral/publication bias rather than a statistically significant association. In fact, the clinical lesion most clinically similar to hairy NS is Becker nevus, with tan macules demonstrating lentiginous melanocytic hyperplasia associated with numerous coarse terminal hairs. There is no indication that Becker nevi have a considerable premalignant potential, though one case of melanoma arising in a Becker nevus has been reported.9 There is no evidence to suggest that classic CMN with hypertrichosis has a greater premalignant potential than similar lesions without hypertrichosis.

We noticed the presence of hair in our patient’s lesion only after reports in the literature caused us to look for this phenomenon.9 This occurrence may actually be quite common. We do not recommend prophylactic excision of NS and believe the risk for malignant degeneration is low in NS with or without hair, though larger NS (>4 cm), especially giant, zosteriform, or segmental lesions, may have a greater risk.1,6,9,10 It is prudent for physicians to carefully examine NS and sample suspicious foci, especially when patients describe a lesion as changing.

- Vidaurri-de la Cruz H, Happle R. Two distinct types of speckled lentiginous nevi characterized by macular versus papular speckles. Dermatology. 2006;212:53-58.

- Ly L, Christie M, Swain S, et al. Melanoma(s) arising in large segmental speckled lentiginous nevi: a case series. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:1190-1193.

- Prose NS, Heilman E, Felman YM, et al. Multiple benign juvenile melanoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1983;9:236-242.

- Grinspan D, Casala A, Abulafia J, et al. Melanoma on dysplastic nevus spilus. Int J Dermatol. 1997;36:499-502 .

- Langenbach N, Pfau A, Landthaler M, et al. Naevi spili, café-au-lait spots and melanocytic naevi aggregated alongside Blaschko’s lines, with a review of segmental melanocytic lesions. Acta Derm Venereol. 1998;78:378-380.

- Schaffer JV, Orlow SJ, Lazova R, et al. Speckled lentiginous nevus: within the spectrum of congenital melanocytic nevi. Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:172-178.

- Saraswat A, Dogra S, Bansali A, et al. Phakomatosis pigmentokeratotica associated with hypophosphataemic vitamin D–resistant rickets: improvement in phosphate homeostasis after partial laser ablation. Br J Dermatol. 2003;148:1074-1076.

- Zeren-Bilgin

i , Gür S, Aydın O, et al. Melanoma arising in a hairy nevus spilus. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:1362-1364. - Singh S, Jain N, Khanna N, et al. Hairy nevus spilus: a case series. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:100-104.

- Price HN, Schaffer JV. Congenital melanocytic nevi—when to worry and how to treat: facts and controversies. Clin Dermatol. 2010;28:293-302.

- Alikhan Ali, Ibrahimi OA, Eisen DB. Congenital melanocytic nevi: where are we now? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:495.e1-495.e17.

- Haenssle HA, Kaune KM, Buhl T, et al. Melanoma arising in segmental nevus spilus: detection by sequential digital dermatoscopy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:337-341.

- Cohen LM. Nevus spilus: congenital or acquired? Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:215-216.

- Vidaurri-de la Cruz H, Happle R. Two distinct types of speckled lentiginous nevi characterized by macular versus papular speckles. Dermatology. 2006;212:53-58.

- Ly L, Christie M, Swain S, et al. Melanoma(s) arising in large segmental speckled lentiginous nevi: a case series. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:1190-1193.

- Prose NS, Heilman E, Felman YM, et al. Multiple benign juvenile melanoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1983;9:236-242.

- Grinspan D, Casala A, Abulafia J, et al. Melanoma on dysplastic nevus spilus. Int J Dermatol. 1997;36:499-502 .

- Langenbach N, Pfau A, Landthaler M, et al. Naevi spili, café-au-lait spots and melanocytic naevi aggregated alongside Blaschko’s lines, with a review of segmental melanocytic lesions. Acta Derm Venereol. 1998;78:378-380.

- Schaffer JV, Orlow SJ, Lazova R, et al. Speckled lentiginous nevus: within the spectrum of congenital melanocytic nevi. Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:172-178.

- Saraswat A, Dogra S, Bansali A, et al. Phakomatosis pigmentokeratotica associated with hypophosphataemic vitamin D–resistant rickets: improvement in phosphate homeostasis after partial laser ablation. Br J Dermatol. 2003;148:1074-1076.

- Zeren-Bilgin

i , Gür S, Aydın O, et al. Melanoma arising in a hairy nevus spilus. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:1362-1364. - Singh S, Jain N, Khanna N, et al. Hairy nevus spilus: a case series. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:100-104.

- Price HN, Schaffer JV. Congenital melanocytic nevi—when to worry and how to treat: facts and controversies. Clin Dermatol. 2010;28:293-302.

- Alikhan Ali, Ibrahimi OA, Eisen DB. Congenital melanocytic nevi: where are we now? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:495.e1-495.e17.

- Haenssle HA, Kaune KM, Buhl T, et al. Melanoma arising in segmental nevus spilus: detection by sequential digital dermatoscopy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:337-341.

- Cohen LM. Nevus spilus: congenital or acquired? Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:215-216.

Practice Points

- Nevus spilus (NS) appears as a café au lait macule studded with darker brown “moles.”

- Although melanoma has been described in NS, it is rare.

- There is no evidence that hairy NS are predisposed to melanoma.

Diagnosing Porokeratosis of Mibelli Every Time: A Novel Biopsy Technique to Maximize Histopathologic Confirmation

Porokeratosis of Mibelli (PM) is a lesion characterized by a surrounding cornoid lamella with variable nonspecific findings (eg, atrophy, acanthosis, verrucous hyperplasia) in the center of the lesion that typically presents in infancy to early childhood.1 We report a case of PM in which a prior biopsy from the center of the lesion demonstrated papulosquamous dermatitis. We propose a 3-step technique to ensure proper orientation of a punch biopsy in cases of suspected PM.

Case Report

A 3-year-old girl presented with an erythematous, hypopigmented, scaling plaque on the posterior aspect of the left ankle surrounded by a hard rim. The plaque was first noted at 12 months of age and had slowly enlarged as the patient grew. Six months prior, a biopsy from the center of the lesion performed at another facility demonstrated a papulosquamous dermatitis.

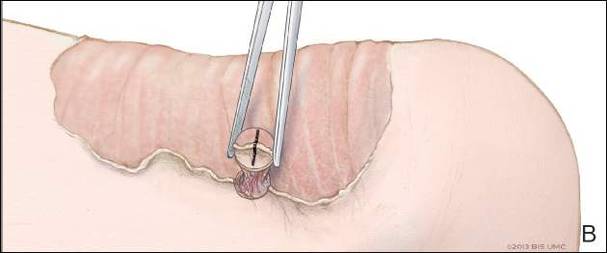

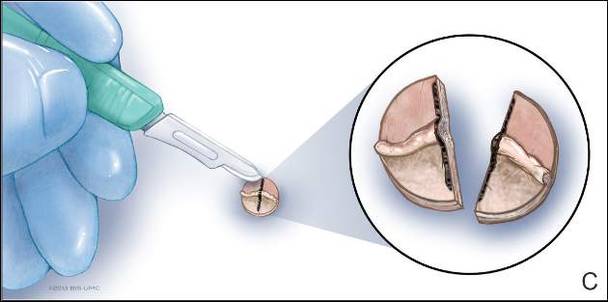

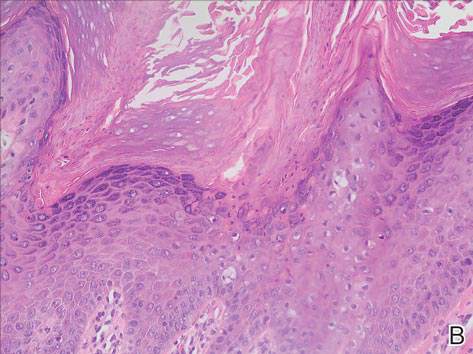

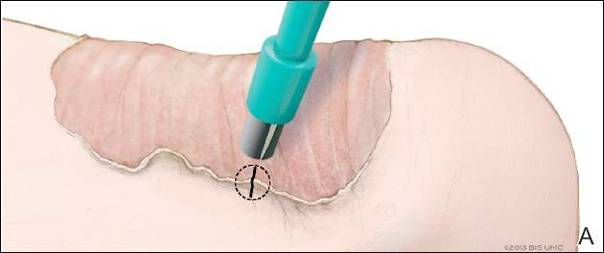

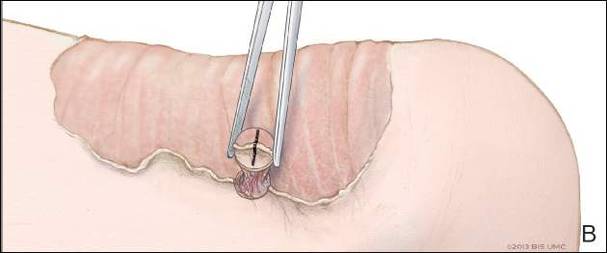

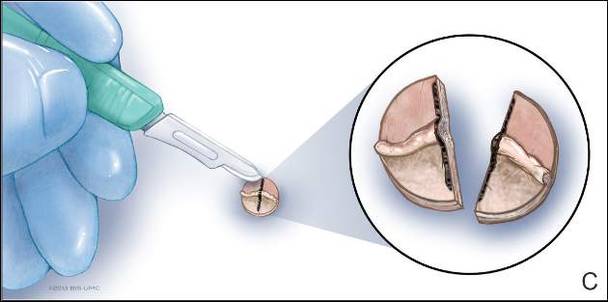

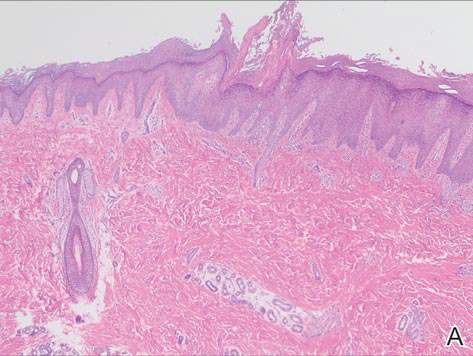

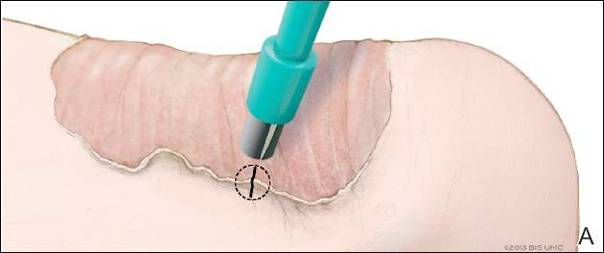

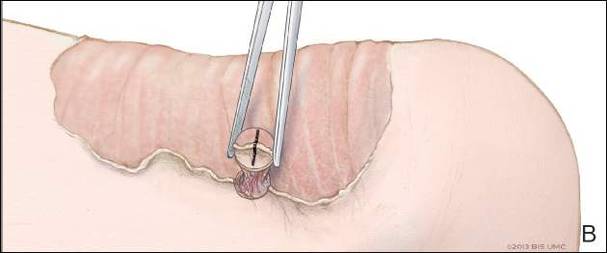

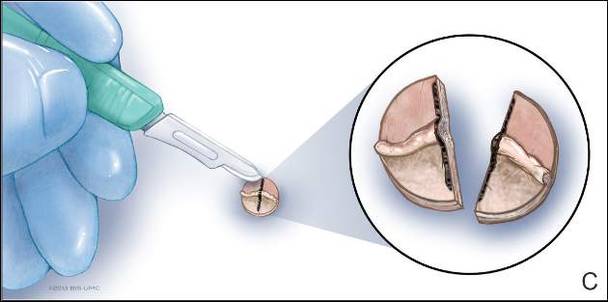

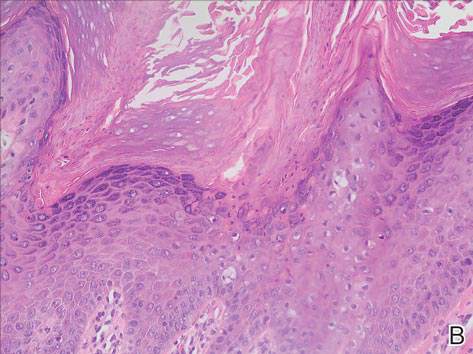

Physical examination revealed a lesion that was 4.2-cm long, 2.2-cm wide at the superior pole, and 3.5-cm wide at the inferior pole (Figure 1). A line was drawn with a skin marker perpendicular to the rim of the lesion (Figure 2A) and a 6-mm punch biopsy was performed, centered at the intersection of the drawn line and the cornoid lamella (Figure 2B). The tissue was then bisected at the bedside along the skin marker line with a #15 blade (Figure 2C) and submitted in formalin for histologic processing. Histologic examination revealed an invagination of the epidermis producing a tier of parakeratotic cells with its apex pointed away from the center of the lesion. Dyskeratotic cells were noted at the base of the parakeratosis (Figure 3). Verrucous hyperplasia was present in the central portion of the specimen adjacent to the cornoid lamella. Based on these histopathologic findings, the correct diagnosis of PM was made.

Comment

Porokeratosis of Mibelli is a rare condition that typically presents in infancy to early childhood.1 It may appear as small keratotic papules or larger plaques that reach several centimeters in diameter.2 There is a 7.5% risk for malignant transformation (eg, basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, Bowen disease).3 Variable nonspecific findings (eg, atrophy, acanthosis, verrucous hyperplasia) typically are present in the center of the lesion. In our case, a biopsy from the center of the plaque demonstrated verrucous hyperplasia. The incorrect diagnosis of PM as psoriasis also has been reported.4

We propose a 3-step technique to ensure proper orientation of a punch biopsy in cases of suspected PM. First, draw a line perpendicular to the rim of the lesion to mark the biopsy site (Figure 2A). Second, perform a punch biopsy centered at the intersection of the drawn line and the cornoid lamella (Figure 2B). Third, section the biopsied tissue with a #15 blade along the perpendicular line at the bedside (Figure 2C). The surgical pathology requisition should mention that the specimen has been transected and the cut edges should be placed down in the cassette, ensuring that the cornoid lamella will be present in cross-section on the slides.

If the punch biopsy specimen is not bisected, it can be difficult to orient it in the pathology laboratory, especially if the cornoid lamellae are not prominent. Furthermore, the technician processing the tissue may not be aware of the importance of sectioning the specimen perpendicular to the cornoid lamella. Following this procedure, diagnosis can be confirmed in virtually every case of PM.

- Richard G, Irvine A, Traupe H, et al. Ichthyosis and disorders of other conification. In: Schachner L, Hansen R, Krafchik B, et al, eds. Pediatric Dermatology. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2011:640-643.

- Pierson D, Bandel C, Ehrig, et al. Benign epidermal tumors and proliferations. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo J, Rapini R, et al, eds. Dermatology. 1st ed. Vol 2. Edinburgh, Scotland: Elsevier; 2003:1707-1709.

- Cort DF, Abdel-Aziz AH. Epithelioma arising in porokeratosis of Mibelli. Br J Plast Surg. 1972;25:318-328.

- De Simone C, Paradisi A, Massi G, et al. Giant verrucous porokeratosis of Mibelli mimicking psoriasis in a patient with psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:665-668.

Porokeratosis of Mibelli (PM) is a lesion characterized by a surrounding cornoid lamella with variable nonspecific findings (eg, atrophy, acanthosis, verrucous hyperplasia) in the center of the lesion that typically presents in infancy to early childhood.1 We report a case of PM in which a prior biopsy from the center of the lesion demonstrated papulosquamous dermatitis. We propose a 3-step technique to ensure proper orientation of a punch biopsy in cases of suspected PM.

Case Report

A 3-year-old girl presented with an erythematous, hypopigmented, scaling plaque on the posterior aspect of the left ankle surrounded by a hard rim. The plaque was first noted at 12 months of age and had slowly enlarged as the patient grew. Six months prior, a biopsy from the center of the lesion performed at another facility demonstrated a papulosquamous dermatitis.

Physical examination revealed a lesion that was 4.2-cm long, 2.2-cm wide at the superior pole, and 3.5-cm wide at the inferior pole (Figure 1). A line was drawn with a skin marker perpendicular to the rim of the lesion (Figure 2A) and a 6-mm punch biopsy was performed, centered at the intersection of the drawn line and the cornoid lamella (Figure 2B). The tissue was then bisected at the bedside along the skin marker line with a #15 blade (Figure 2C) and submitted in formalin for histologic processing. Histologic examination revealed an invagination of the epidermis producing a tier of parakeratotic cells with its apex pointed away from the center of the lesion. Dyskeratotic cells were noted at the base of the parakeratosis (Figure 3). Verrucous hyperplasia was present in the central portion of the specimen adjacent to the cornoid lamella. Based on these histopathologic findings, the correct diagnosis of PM was made.

Comment

Porokeratosis of Mibelli is a rare condition that typically presents in infancy to early childhood.1 It may appear as small keratotic papules or larger plaques that reach several centimeters in diameter.2 There is a 7.5% risk for malignant transformation (eg, basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, Bowen disease).3 Variable nonspecific findings (eg, atrophy, acanthosis, verrucous hyperplasia) typically are present in the center of the lesion. In our case, a biopsy from the center of the plaque demonstrated verrucous hyperplasia. The incorrect diagnosis of PM as psoriasis also has been reported.4

We propose a 3-step technique to ensure proper orientation of a punch biopsy in cases of suspected PM. First, draw a line perpendicular to the rim of the lesion to mark the biopsy site (Figure 2A). Second, perform a punch biopsy centered at the intersection of the drawn line and the cornoid lamella (Figure 2B). Third, section the biopsied tissue with a #15 blade along the perpendicular line at the bedside (Figure 2C). The surgical pathology requisition should mention that the specimen has been transected and the cut edges should be placed down in the cassette, ensuring that the cornoid lamella will be present in cross-section on the slides.

If the punch biopsy specimen is not bisected, it can be difficult to orient it in the pathology laboratory, especially if the cornoid lamellae are not prominent. Furthermore, the technician processing the tissue may not be aware of the importance of sectioning the specimen perpendicular to the cornoid lamella. Following this procedure, diagnosis can be confirmed in virtually every case of PM.

Porokeratosis of Mibelli (PM) is a lesion characterized by a surrounding cornoid lamella with variable nonspecific findings (eg, atrophy, acanthosis, verrucous hyperplasia) in the center of the lesion that typically presents in infancy to early childhood.1 We report a case of PM in which a prior biopsy from the center of the lesion demonstrated papulosquamous dermatitis. We propose a 3-step technique to ensure proper orientation of a punch biopsy in cases of suspected PM.

Case Report

A 3-year-old girl presented with an erythematous, hypopigmented, scaling plaque on the posterior aspect of the left ankle surrounded by a hard rim. The plaque was first noted at 12 months of age and had slowly enlarged as the patient grew. Six months prior, a biopsy from the center of the lesion performed at another facility demonstrated a papulosquamous dermatitis.

Physical examination revealed a lesion that was 4.2-cm long, 2.2-cm wide at the superior pole, and 3.5-cm wide at the inferior pole (Figure 1). A line was drawn with a skin marker perpendicular to the rim of the lesion (Figure 2A) and a 6-mm punch biopsy was performed, centered at the intersection of the drawn line and the cornoid lamella (Figure 2B). The tissue was then bisected at the bedside along the skin marker line with a #15 blade (Figure 2C) and submitted in formalin for histologic processing. Histologic examination revealed an invagination of the epidermis producing a tier of parakeratotic cells with its apex pointed away from the center of the lesion. Dyskeratotic cells were noted at the base of the parakeratosis (Figure 3). Verrucous hyperplasia was present in the central portion of the specimen adjacent to the cornoid lamella. Based on these histopathologic findings, the correct diagnosis of PM was made.

Comment

Porokeratosis of Mibelli is a rare condition that typically presents in infancy to early childhood.1 It may appear as small keratotic papules or larger plaques that reach several centimeters in diameter.2 There is a 7.5% risk for malignant transformation (eg, basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, Bowen disease).3 Variable nonspecific findings (eg, atrophy, acanthosis, verrucous hyperplasia) typically are present in the center of the lesion. In our case, a biopsy from the center of the plaque demonstrated verrucous hyperplasia. The incorrect diagnosis of PM as psoriasis also has been reported.4

We propose a 3-step technique to ensure proper orientation of a punch biopsy in cases of suspected PM. First, draw a line perpendicular to the rim of the lesion to mark the biopsy site (Figure 2A). Second, perform a punch biopsy centered at the intersection of the drawn line and the cornoid lamella (Figure 2B). Third, section the biopsied tissue with a #15 blade along the perpendicular line at the bedside (Figure 2C). The surgical pathology requisition should mention that the specimen has been transected and the cut edges should be placed down in the cassette, ensuring that the cornoid lamella will be present in cross-section on the slides.

If the punch biopsy specimen is not bisected, it can be difficult to orient it in the pathology laboratory, especially if the cornoid lamellae are not prominent. Furthermore, the technician processing the tissue may not be aware of the importance of sectioning the specimen perpendicular to the cornoid lamella. Following this procedure, diagnosis can be confirmed in virtually every case of PM.

- Richard G, Irvine A, Traupe H, et al. Ichthyosis and disorders of other conification. In: Schachner L, Hansen R, Krafchik B, et al, eds. Pediatric Dermatology. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2011:640-643.

- Pierson D, Bandel C, Ehrig, et al. Benign epidermal tumors and proliferations. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo J, Rapini R, et al, eds. Dermatology. 1st ed. Vol 2. Edinburgh, Scotland: Elsevier; 2003:1707-1709.

- Cort DF, Abdel-Aziz AH. Epithelioma arising in porokeratosis of Mibelli. Br J Plast Surg. 1972;25:318-328.

- De Simone C, Paradisi A, Massi G, et al. Giant verrucous porokeratosis of Mibelli mimicking psoriasis in a patient with psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:665-668.

- Richard G, Irvine A, Traupe H, et al. Ichthyosis and disorders of other conification. In: Schachner L, Hansen R, Krafchik B, et al, eds. Pediatric Dermatology. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2011:640-643.

- Pierson D, Bandel C, Ehrig, et al. Benign epidermal tumors and proliferations. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo J, Rapini R, et al, eds. Dermatology. 1st ed. Vol 2. Edinburgh, Scotland: Elsevier; 2003:1707-1709.

- Cort DF, Abdel-Aziz AH. Epithelioma arising in porokeratosis of Mibelli. Br J Plast Surg. 1972;25:318-328.

- De Simone C, Paradisi A, Massi G, et al. Giant verrucous porokeratosis of Mibelli mimicking psoriasis in a patient with psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:665-668.

Practice Points

- A biopsy from the center of a plaque of porokeratosis will produce nonspecific findings.

- Bisecting the punch specimen at the bedside along a line drawn perpendicular to the cornoid lamella guarantees proper orientation of the specimen.

Young girl with lower leg rash

An 8-year-old girl was brought into our clinic for evaluation of a leg rash on her right lower leg that had been bothering her for 2 months. Another physician had performed a biopsy and diagnosed subacute spongiotic dermatitis, but the rash did not respond to treatment with triamcinolone cream 0.1% twice daily.

The rash was mildly tender and markedly pruritic. The girl had no history of trauma, prior skin conditions, or other areas with a similar rash. Physical examination revealed concentric annular lesions on the right lower leg (FIGURE). The central areas demonstrated a bruised appearance that did not resolve with diascopy.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: tinea corporis

A potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation was performed. It showed septate hyphae and confirmed a diagnosis of tinea corporis. We ordered a periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) stain on the previous biopsy specimen, and it revealed septate hyphae in the stratum corneum that were not apparent on the original hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stained sections.

Dermatophyte infections of the skin are known as tinea corporis or “ringworm.” Ringworm fungi belong to 3 genera, Microsporum, Trichophyton, and Epidermophyton. These infections occur at any age and are more common in warmer climates.1 The classic lesion is an annular scaly patch, sometimes with the concentric rings, as seen in our patient (FIGURE). The bruising was almost certainly caused by rubbing and scratching.

We suspected tinea coporis based on the physical characteristics of the rash and the fact that it did not respond promptly to topical steroids. Our suspicions were confirmed by the KOH prep. Inked KOH using chlorazol black E stain turns fungal hyphae black, which makes them easier to distinguish from keratinocyte cell walls.2

Differential of a nonspecific rash should include infections

The initial misdiagnosis was based on the histopathologic diagnosis of spongiotic dermatitis. Subacute spongiotic dermatitis is associated with intracellular and intercellular edema of the keratinocytes in the epidermis. This is a nonspecific finding seen in eczematous dermatitis and can be etiologically associated with a wide variety of clinical conditions, including allergic contact dermatitis, atopic dermatitis, nummular eczema, and, in this case, dermatophytosis.3

If a biopsy is performed for a nonspecific rash, the pathologist should be advised of the possibility of superficial fungal infection. Providing a history and the physical characteristics of the rash or a differential diagnosis will prompt the performance of a PAS stain. Otherwise, the diagnosis can be missed because fungal elements are often not visible on routine H&E stains.

Proper treatment

provides speedy relief

Tinea corporis on a non-hair-bearing area is readily cleared with a topical azole antifungal agent, such as ketoconazole cream 2% twice daily for 2 weeks or a topical allylamine, such as terbinafine cream 1%, twice daily for 2 weeks. Topical allylamines may be more effective than topical azoles for tinea corporis4 (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A). Hair-bearing areas such as the scalp, fingers, and toes are unlikely to respond to topically applied medications and require an oral anti-fungal medication, such as griseofulvin 15 to 20 mg/kg/d.5

Relief for our patient

Our patient’s rash was treated with griseofulvin oral suspension 20 mg/kg/d (with milk to enhance absorption) for 6 weeks. There was complete clearing and the condition did not recur.

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

1. Shrum JP, Millikan LE, Bataineh O. Superficial fungal infections in the tropics. Dermatol Clin. 1994;12:687-693.

2. Burke WA, Jones BE. A simple stain for rapid office diagnosis of fungus infections of the skin. Arch Dermatol. 1984;120:1519-1520.

3. Alsaad KO, Ghazarian D. My approach to superficial inflammatory dermatoses. J Clin Pathol. 2005;58:1233-1241.

4. Rotta I, Otuki MF, Sanches AC, et al. Efficacy of topical antifungal drugs in different dermatomycoses: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Rev Assoc Med Bras. 2012;58:308-318.

5. Noble SL, Forbes RC, Stamm PL. Diagnosis and management of common tinea infections. Am Fam Physician. 1998;58:163-174,177-178.

An 8-year-old girl was brought into our clinic for evaluation of a leg rash on her right lower leg that had been bothering her for 2 months. Another physician had performed a biopsy and diagnosed subacute spongiotic dermatitis, but the rash did not respond to treatment with triamcinolone cream 0.1% twice daily.

The rash was mildly tender and markedly pruritic. The girl had no history of trauma, prior skin conditions, or other areas with a similar rash. Physical examination revealed concentric annular lesions on the right lower leg (FIGURE). The central areas demonstrated a bruised appearance that did not resolve with diascopy.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: tinea corporis

A potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation was performed. It showed septate hyphae and confirmed a diagnosis of tinea corporis. We ordered a periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) stain on the previous biopsy specimen, and it revealed septate hyphae in the stratum corneum that were not apparent on the original hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stained sections.

Dermatophyte infections of the skin are known as tinea corporis or “ringworm.” Ringworm fungi belong to 3 genera, Microsporum, Trichophyton, and Epidermophyton. These infections occur at any age and are more common in warmer climates.1 The classic lesion is an annular scaly patch, sometimes with the concentric rings, as seen in our patient (FIGURE). The bruising was almost certainly caused by rubbing and scratching.

We suspected tinea coporis based on the physical characteristics of the rash and the fact that it did not respond promptly to topical steroids. Our suspicions were confirmed by the KOH prep. Inked KOH using chlorazol black E stain turns fungal hyphae black, which makes them easier to distinguish from keratinocyte cell walls.2

Differential of a nonspecific rash should include infections

The initial misdiagnosis was based on the histopathologic diagnosis of spongiotic dermatitis. Subacute spongiotic dermatitis is associated with intracellular and intercellular edema of the keratinocytes in the epidermis. This is a nonspecific finding seen in eczematous dermatitis and can be etiologically associated with a wide variety of clinical conditions, including allergic contact dermatitis, atopic dermatitis, nummular eczema, and, in this case, dermatophytosis.3

If a biopsy is performed for a nonspecific rash, the pathologist should be advised of the possibility of superficial fungal infection. Providing a history and the physical characteristics of the rash or a differential diagnosis will prompt the performance of a PAS stain. Otherwise, the diagnosis can be missed because fungal elements are often not visible on routine H&E stains.

Proper treatment

provides speedy relief

Tinea corporis on a non-hair-bearing area is readily cleared with a topical azole antifungal agent, such as ketoconazole cream 2% twice daily for 2 weeks or a topical allylamine, such as terbinafine cream 1%, twice daily for 2 weeks. Topical allylamines may be more effective than topical azoles for tinea corporis4 (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A). Hair-bearing areas such as the scalp, fingers, and toes are unlikely to respond to topically applied medications and require an oral anti-fungal medication, such as griseofulvin 15 to 20 mg/kg/d.5

Relief for our patient

Our patient’s rash was treated with griseofulvin oral suspension 20 mg/kg/d (with milk to enhance absorption) for 6 weeks. There was complete clearing and the condition did not recur.

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

An 8-year-old girl was brought into our clinic for evaluation of a leg rash on her right lower leg that had been bothering her for 2 months. Another physician had performed a biopsy and diagnosed subacute spongiotic dermatitis, but the rash did not respond to treatment with triamcinolone cream 0.1% twice daily.

The rash was mildly tender and markedly pruritic. The girl had no history of trauma, prior skin conditions, or other areas with a similar rash. Physical examination revealed concentric annular lesions on the right lower leg (FIGURE). The central areas demonstrated a bruised appearance that did not resolve with diascopy.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: tinea corporis

A potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation was performed. It showed septate hyphae and confirmed a diagnosis of tinea corporis. We ordered a periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) stain on the previous biopsy specimen, and it revealed septate hyphae in the stratum corneum that were not apparent on the original hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stained sections.

Dermatophyte infections of the skin are known as tinea corporis or “ringworm.” Ringworm fungi belong to 3 genera, Microsporum, Trichophyton, and Epidermophyton. These infections occur at any age and are more common in warmer climates.1 The classic lesion is an annular scaly patch, sometimes with the concentric rings, as seen in our patient (FIGURE). The bruising was almost certainly caused by rubbing and scratching.

We suspected tinea coporis based on the physical characteristics of the rash and the fact that it did not respond promptly to topical steroids. Our suspicions were confirmed by the KOH prep. Inked KOH using chlorazol black E stain turns fungal hyphae black, which makes them easier to distinguish from keratinocyte cell walls.2

Differential of a nonspecific rash should include infections

The initial misdiagnosis was based on the histopathologic diagnosis of spongiotic dermatitis. Subacute spongiotic dermatitis is associated with intracellular and intercellular edema of the keratinocytes in the epidermis. This is a nonspecific finding seen in eczematous dermatitis and can be etiologically associated with a wide variety of clinical conditions, including allergic contact dermatitis, atopic dermatitis, nummular eczema, and, in this case, dermatophytosis.3

If a biopsy is performed for a nonspecific rash, the pathologist should be advised of the possibility of superficial fungal infection. Providing a history and the physical characteristics of the rash or a differential diagnosis will prompt the performance of a PAS stain. Otherwise, the diagnosis can be missed because fungal elements are often not visible on routine H&E stains.

Proper treatment

provides speedy relief

Tinea corporis on a non-hair-bearing area is readily cleared with a topical azole antifungal agent, such as ketoconazole cream 2% twice daily for 2 weeks or a topical allylamine, such as terbinafine cream 1%, twice daily for 2 weeks. Topical allylamines may be more effective than topical azoles for tinea corporis4 (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A). Hair-bearing areas such as the scalp, fingers, and toes are unlikely to respond to topically applied medications and require an oral anti-fungal medication, such as griseofulvin 15 to 20 mg/kg/d.5

Relief for our patient

Our patient’s rash was treated with griseofulvin oral suspension 20 mg/kg/d (with milk to enhance absorption) for 6 weeks. There was complete clearing and the condition did not recur.

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

1. Shrum JP, Millikan LE, Bataineh O. Superficial fungal infections in the tropics. Dermatol Clin. 1994;12:687-693.

2. Burke WA, Jones BE. A simple stain for rapid office diagnosis of fungus infections of the skin. Arch Dermatol. 1984;120:1519-1520.

3. Alsaad KO, Ghazarian D. My approach to superficial inflammatory dermatoses. J Clin Pathol. 2005;58:1233-1241.

4. Rotta I, Otuki MF, Sanches AC, et al. Efficacy of topical antifungal drugs in different dermatomycoses: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Rev Assoc Med Bras. 2012;58:308-318.

5. Noble SL, Forbes RC, Stamm PL. Diagnosis and management of common tinea infections. Am Fam Physician. 1998;58:163-174,177-178.

1. Shrum JP, Millikan LE, Bataineh O. Superficial fungal infections in the tropics. Dermatol Clin. 1994;12:687-693.

2. Burke WA, Jones BE. A simple stain for rapid office diagnosis of fungus infections of the skin. Arch Dermatol. 1984;120:1519-1520.

3. Alsaad KO, Ghazarian D. My approach to superficial inflammatory dermatoses. J Clin Pathol. 2005;58:1233-1241.

4. Rotta I, Otuki MF, Sanches AC, et al. Efficacy of topical antifungal drugs in different dermatomycoses: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Rev Assoc Med Bras. 2012;58:308-318.

5. Noble SL, Forbes RC, Stamm PL. Diagnosis and management of common tinea infections. Am Fam Physician. 1998;58:163-174,177-178.