User login

Integrating Germline Genetics Into Precision Oncology Practice in the Veterans Health Administration: Challenges and Opportunities (FULL)

The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) oversees the largest integrated health care system in the nation, administering care to 9 million veterans annually throughout its distributed network of 1,255 medical centers and outpatient facilities. Every year, about 50,000 veterans are diagnosed with and treated for cancer in the VA, representing about 3% of all cancer cases in the US.1 After skin cancer, prostate, colon, and lung cancers are the most common among veterans.1 One way that VA has sought to improve the care of its large cancer patient population is through the adoption of precision oncology, an ever-evolving practice of analyzing an individual patient’s cancer to inform clinical decision making. Most often, the analysis includes conducting genetic testing of the tumor itself. Here, we describe the opportunities and challenges of integrating germline genetics into precision oncology practice.

The Intersection of Precision Oncology and Germline Genetics

Precision oncology typically refers to genetic testing of tumor DNA to identify genetic variants with potential diagnostic, prognostic, or predictive therapeutic implications. It is enabled by a growing body of knowledge that identifies key drivers of cancer development, coupled with advances in tumor analysis by next-generation sequencing and other technologies and by the availability of new and repurposed therapeutic agents.2 Precision oncology has transformed cancer care by targeting both common and rare malignancies with specific therapies that improve clinical outcomes in patients.3

Testing of tumor DNA can reveal both somatic (acquired) and germline (inherited) gene variants. Precision oncology testing strategies can include tumor-only testing with or without subtraction of suspected germline variants, or paired tumor-normal testing with explicit analysis and reporting of genes associated with germline predisposition.2 With tumor-only testing, the germline status of variants may be inferred and follow-up germline testing in normal tissue such as blood or saliva can be considered. Paired tumor-normal testing provides distinct advantages over tumor-only testing, including improvement of the mutation detection rate in tumors and streamlining interpretation of results for both the tumor and germline tests.

Regardless of the strategy used, tumor testing has the potential to uncover clinically relevant germline variation associated with heritable cancer susceptibility and other conditions, as well as carrier status for autosomal recessive disorders (eAppendix

Germline genetic information, independent of somatic variation, can influence the choice of targeted cancer therapies. For example, Mandelker and colleagues identified germline variants that would impact the treatment of 38 (3.7%) of 1,040 patients with cancer.4 Individuals with a germline pathogenic variant in a DNA repair gene (eg, BRCA1, BRCA2, ATM, CHEK2) are candidates for platinum chemotherapy and poly-(adenosine diphosphate-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors that target the inability of a tumor to repair double-stranded DNA breaks.5,6 Individuals with a germline pathogenic variant in the MSH2, MLH1, MSH6, PMS2 or EPCAM genes (ie, Lynch syndrome) have tumors that are deficient in mismatch repair, and these tumors are responsive to inhibitors of the programmed death 1 (PD1) pathway.7,8

In addition to changing treatment decisions, identifying pathogenic germline variants can have health, reproductive, and psychosocial implications for the patient and the patient’s family members.9,10 A pathogenic germline variant can imply disease risk for both the patient and his or her relatives. In these cases, it is important to ascertain family history, understand the mode of inheritance, identify at-risk relatives, review the associated phenotype, and discuss management and prevention options for the patient and for family members. For example, a germline pathogenic variant in the BRCA2 gene is associated with increased risk for breast, ovarian, pancreatic, gastric, bile duct, and laryngeal cancer, and melanoma.11 Knowledge of these increased cancer risks could inform cancer prevention and early detection options, such as more frequent and intensive surveillance starting at younger ages compared with that of average-risk individuals, use of chemoprevention treatments, and for those at highest risk, risk-reducing surgical procedures. Therefore, reporting germline test results requires the clinician to take on additional responsibilities beyond those required when reporting only somatic variants.

Because of the complexities inherent in germline genetic testing, it traditionally is offered in the context of a genetic consultation, comprised of genetic evaluation and genetic counseling (Figure). Clinical geneticists are physicians certified by the American Board of Medical Genetics and Genomics (a member board of the American Board of Medical Specialties) who received special training in the diagnosis and management of medical genetic conditions; they are trained to perform all aspects of a genetic consultation across the clinical spectrum and lifespan of a patient.12 In contrast, genetic counselors have a master’s degree in genetic counseling, a communication process that facilitates patient decision making surrounding the genetic evaluation.13 Most work as members of a team to ensure provision of comprehensive clinical genetic services. Genetic counselors are licensed in most states, and licensure in some states sanctions the ordering of genetic tests by genetic counselors. Genetics nurses are licensed professional nurses with special education and training in genetics who function in diverse roles in industry, education, research, and clinical care.14 Genetics nurses in clinical care perform risk assessment based on personal and family history, recognize and identify genetic conditions and predispositions, and discuss the implications of this with patients and their families. Advanced practice nurses (APRNs) have additional training that allows for diagnosis, interpretation of results, and surveillance and management recommendations.15

Germline Genetic Testing Challenges

Integrating germline genetic testing in precision oncology practice presents challenges at the patient, family, health care provider, and health system levels. Due to these challenges, implementation planning is obligatory, as germline testing has become a standard-of-care for certain tumor types and patients.2

On learning of a germline pathogenic variant or variant of uncertain significance, patients may experience distress and anxiety, especially in the short term.16-18 In addition, it can be difficult for patients to share germline genetic test results with their family; parents may feel guilty about the possibility of passing on a predisposition to children, and unaffected siblings may experience survivor guilt. For some veterans, there can be concerns about losing service-connected benefits if a genetic factor is found to contribute to their cancer history. In addition, patients may have concerns about discrimination by employers or insurers, including commercial health insurance or long-term care, disability, and life insurance. Yet there are many state and federal laws that ensure some protection from employment and health insurance discrimination based on genetic information.

For cancer care clinicians, incorporating germline testing requires additional responsibilities that can complicate care. Prior to germline genetic testing, genetic counseling with patients is recommended to review the potential benefits, harms, and limitations of genetic testing. Further, posttest genetic counseling is recommended to help the patient understand how the results may influence future cancer risks, provide recommendations for cancer management and prevention, and discuss implications for family members.9,10 While patients trust their health care providers to help them access and understand their genetic information, most health care providers are unprepared to integrate genetics into their practice; they lack adequate knowledge, skills, and confidence about genetics to effectively deliver genetic services.19-26 This leads to failure to recognize patients with indications for genetic testing, which often is due to insufficient family history collection. Other errors can include offering germline genetic testing to patients without appropriate indications and with inadequate informed consent procedures. When genetic testing is pursued, lack of knowledge about genetic principles and testing methods can lead to misinterpretation and miscommunication of results, contributing to inappropriate management recommendations. These errors can contribute to under-use, overuse, or misuse of genetic testing that can compromise the quality of patient care.27,28 With this in mind, thought must be given at the health care system level to develop effective strategies to deliver genetic services to patients. These strategies must address workforce capacity, organizational structure, and education.

Workforce Capacity

The VA clinical genetics workforce needs to expand to keep pace with increasing demand, which will be accelerated by the precision oncology programs for prostate and lung cancers and the VA Teleoncology initiative. In the US there are 10 to 15 genetics professionals per 1,000,000 residents.29-31 Most genetics professionals work in academic and metropolitan settings, leaving suburban and rural areas underserved. For example, in California, some patients travel up to 386 miles for genetics care (mean, 76.6 miles).32 In the VA, there are only 1 to 2 genetics professionals per 1 million enrollees, about 10-fold fewer than in community care. Meeting clinical needs of patients at the VA is particularly challenging because more than one-third of veterans live in rural areas.33

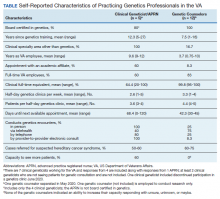

We recently surveyed genetics professionals in the VA about their practices and capacity to increase patient throughput (Table). Currently in the VA, there are 8 clinical geneticists, not all of whom practice clinical genetics, and 13 genetic counselors. Five VA programs provide clinical genetic services to local and nearby VA facilities near Boston, Massachusetts; Houston, Texas; Los Angeles and San Francisco, California; and Salt Lake City, Utah. These programs, first developed in 2008, typically are staffed by 1 or 2 genetics professionals. Most patients who are referred to the VA genetics programs are evaluated for hereditary cancer syndromes. Multiple modes of delivery may be used, including in-person, telehealth, telephone, and provider-to-provider e-consults in the EHR.

In 2010, in response to increased demand for clinical genetics services, the VA launched the Genomic Medicine Service (GMS), a national program with a centralized team of 9 genetic counselors based in Salt Lake City. GMS provides telehealth genetic counseling services exclusively to veterans onsite and at about 90 VA facilities across the country. More recently, the addition of a clinical geneticist and APRN with genetics expertise has allowed GMS to provide more comprehensive genetic consultative services.

All VA genetics programs are currently at full capacity with long waits for an appointment. To expand clinical genetic services, the VA genetics professionals responding to our survey reported a need for additional support (eg, administrative, care coordination, clinical), resources (eg, clinical space, salary support), and organizational change (eg, division of Medical Genetics at facility level, services provided at the level of the Veterans Integrated Service Network). Given the dearth of genetic care providers in the community, referral to non-VA care is not a viable option in many markets. In addition, avoiding referral outside of the VA could help to ensure continuity of care, more efficient care, and reduce the risk of duplication of testing, and polypharmacy.34-37

As part of its precision oncology initiative, VA is focusing on building clinical genetics services capacity. To increase access to clinical genetic services and appropriate genetic testing, the VA needs more genetics professionals, including clinical geneticists, genetic counselors, and genetic nurses–ideally a workforce study could be performed to inform the right staffing mix needed. To grow the genetics workforce in the long term, the VA could leverage its academic affiliations to train the next generation of genetics professionals. The VA has an important role in training medical professionals. By forming affiliations with medical schools and universities, the VA has become the largest provider of health care training in the US.38

Genetic Health Care Organization in the VA

Understanding a patient’s genetic background increasingly has become more and more important in the clinic, which necessitates a major shift in health care. Unfortunately, on a national scale, the number of clinical genetics professionals has not kept pace with the need-limiting the ability to grow the traditional genetics workforce in the VA in the near term.29-31 Thus, we must look to alternative genetic health care models in which other members of the health care team assume some of the genetic evaluation and counseling activities while caring for their cancer patients with referral to a clinical genetics team, as needed.39

Two genetic health care models have been described.40 Traditionally, clinical genetic services are coordinated between genetics professionals and other clinicians, organized as a regional genetics center and usually affiliated with an academic medical center. By contrast, the nontraditional genetic health care model integrates genetic services within primary and specialty care. Under the new approach, nongeneticists can be assisted by decision support tools in the EHR that help with assessing family history risk, identifying indications for genetic testing, and suggesting management options based on genetic test results.41-43

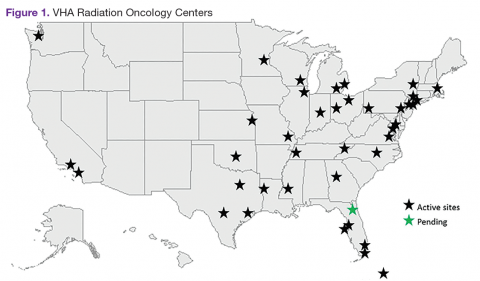

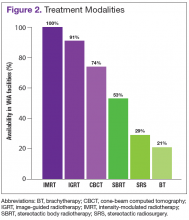

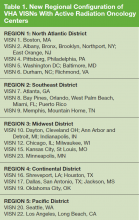

The VA National Precision Oncology Program (NPOP) is shaped by a commitment to be a high reliability organization (HRO). As such, the goal is to create a system of excellence that integrates precision medicine, implementation science, and the learning health care system to improve the health and health care of veterans with cancer. This initiative is establishing the foundations for best-in-class cancer care to enable veterans access to life-saving therapies through a concerted effort that began with the Cancer Moonshot, development of the NPOP, and collaborations with the VA Office of Research and Development. One of the fundamental objectives of this initiative is to implement strategies that ensure clinical genetic services are available to veterans receiving cancer care at all VA facilities and to extend these services to veterans in remote geographic locations nationwide. The initiative aims to synergize VA Teleoncology services that seek to deliver best-in-class oncology care across the VA enterprise using cutting-edge technologies.

Conclusions

To accomplish the goal of delivering world-class clinical genetic services to veterans and meet the increasing needs of precision oncology and support quality genetic health care, the VA must develop an integrated system of genetic health care that will have a network of clinical genetics that interfaces with other clinical and operational programs, genomics researchers, and educational programs to support quality genetic health care. The VA has highly qualified and dedicated genetics professionals at many sites across the country. Connecting them could create powerful synergies that would benefit patients and strengthen the genetics workforce. The clinical genetics network will enable development and dissemination of evidence-based policies, protocols, and clinical pathways for genomic medicine. This will help to identify, benchmark, and promote best practices for clinical genetic services, and increase access, increase efficiencies, and reduce variability in the care delivered.

The VA is well positioned to achieve successful implementation of genetic services given its investment in genomic medicine and the commitment of the VA NPOP. However, there is a need for structured and targeted implementation strategies for genetic services in the VA, as uptake of this innovation will not occur by passive diffusion.44,45 To keep pace with the demand for germline testing in veterans, VA may want to consider an outsized focus on training genetics professionals, given the high demand for this expertise. Perhaps most importantly, the VA will need to better prepare its frontline clinical workforce to integrate genetics into their practice. This could be facilitated by identifying implementation strategies and educational programs for genomic medicine that help clinicians to think genetically while caring for their patients, performing aspects of family history risk assessment and pre- and posttest genetic counseling as they are able, and referring complex cases to the clinical genetics network when needed.

Much is already known on how best to accomplish this through studies conducted by many talented VA health services researchers.46 Crucially, clinical tools embedded within the VA EHR will be fundamental to these efforts by facilitating identification of patients who can benefit from genetic services and genetic testing at the point of care. Through integration of VA research with clinical genetic services, the VA will become more prepared to realize the promise of genomic medicine for veterans.

Acknowledgments

We thank the members of the Genomic Medicine Program Advisory Committee, Clinical Genetics Subcommittee for providing input and guidance on the topics included in this article.

1. Zullig LL, Sims KJ, McNeil R, et al. Cancer incidence among patients of the U.S. Veterans Affairs Health Care System: 2010 update. Mil Med. 2017;182(7):e1883-e1891. doi:10.7205/MILMED-D-16-00371

2. Li MM, Chao E, Esplin ED, et al. Points to consider for reporting of germline variation in patients undergoing tumor testing: a statement of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG). Genet Med. 2020;22(7):1142-1148. doi:10.1038/s41436-020-0783-8

3. Malone ER, Oliva M, Sabatini PJB, Stockley TL, Siu LL. Molecular profiling for precision cancer therapies. Genome Med. 2020;12(1):8. Published 2020 Jan 14. doi:10.1186/s13073-019-0703-1

4. Mandelker D, Zhang L, Kemel Y, et al. Mutation detection in patients with advanced cancer by universal sequencing of cancer-related genes in tumor and normal DNA vs guideline-based germline testing [published correction appears in JAMA. 2018 Dec 11;320(22):2381]. JAMA. 2017;318(9):825-835. doi:10.1001/jama.2017.11137

5. Mateo J, Carreira S, Sandhu S, et al. DNA-repair defects and olaparib in metastatic prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(18):1697-1708. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1506859

6. Ratta R, Guida A, Scotté F, et al. PARP inhibitors as a new therapeutic option in metastatic prostate cancer: a systematic review [published online ahead of print, 2020 May 4]. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2020;10.1038/s41391-020-0233-3. doi:10.1038/s41391-020-0233-3

7. Le DT, Uram JN, Wang H, et al. PD-1 Blockade in tumors with mismatch-repair deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(26):2509-2520. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1500596

8. Graham LS, Montgomery B, Cheng HH, et al. Mismatch repair deficiency in metastatic prostate cancer: Response to PD-1 blockade and standard therapies. PLoS One. 2020;15(5):e0233260. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0233260

9. Robson ME, Storm CD, Weitzel J, Wollins DS, Offit K; American Society of Clinical Oncology. American Society of Clinical Oncology policy statement update: genetic and genomic testing for cancer susceptibility. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(5):893-901. doi:10.1200/JCO.2009.27.0660

10. Riley BD, Culver JO, Skrzynia C, et al. Essential elements of genetic cancer risk assessment, counseling, and testing: updated recommendations of the National Society of Genetic Counselors. J Genet Couns. 2012;21(2):151-161. doi:10.1007/s10897-011-9462-x

11. Petrucelli N, Daly MB, Pal T. BRCA1- and BRCA2-associated hereditary breast and ovarian cancer. In: Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Pagon RA, et al, eds. GeneReviews. Seattle, WA: University of Washington, Seattle; 1993.

12. ACMG Board of Directors. Scope of practice: a statement of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG). Genet Med. 2015;17(9):e3. doi:10.1038/gim.2015.94

13. National Society of Genetic Counselors’ Definition Task Force, Resta R, Biesecker BB, et al. A new definition of Genetic Counseling: National Society of Genetic Counselors’ Task Force report. J Genet Couns. 2006;15(2):77-83. doi:10.1007/s10897-005-9014-3

14. Calzone KA, Cashion A, Feetham S, et al. Nurses transforming health care using genetics and genomics [published correction appears in Nurs Outlook. 2010;58(3):163]. Nurs Outlook. 2010;58(1):26-35. doi:10.1016/j.outlook.2009.05.001

15. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Nursing Services. 2018 Office of Nursing Services (ONS) Annual Brief. https://www.va.gov/nursing/docs/about/2018_ONS_Annual_Report_Brief.pdf. Accessed July 21, 2020.

16. Lerman C, Croyle RT. Emotional and behavioral responses to genetic testing for susceptibility to cancer. Oncology (Williston Park). 1996;10(2):191-202.

17. Bonadona V, Saltel P, Desseigne F, et al. Cancer patients who experienced diagnostic genetic testing for cancer susceptibility: reactions and behavior after the disclosure of a positive test result. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2002;11(1):97-104.

18. Murakami Y, Okamura H, Sugano K, et al. Psychologic distress after disclosure of genetic test results regarding hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal carcinoma. Cancer. 2004;101(2):395-403. doi:10.1002/cncr.20363

19. Brierley KL, Campfield D, Ducaine W, et al. Errors in delivery of cancer genetics services: implications for practice. Conn Med. 2010;74(7):413-423.

20. Dhar SU, Cooper HP, Wang T, et al. Significant differences among physician specialties in management recommendations of BRCA1 mutation carriers. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;129(1):221-227. doi:10.1007/s10549-011-1449-7

21. Plon SE, Cooper HP, Parks B, et al. Genetic testing and cancer risk management recommendations by physicians for at-risk relatives. Genet Med. 2011;13(2):148-154. doi:10.1097/GIM.0b013e318207f564

22. Bellcross CA, Kolor K, Goddard KA, Coates RJ, Reyes M, Khoury MJ. Awareness and utilization of BRCA1/2 testing among U.S. primary care physicians. Am J Prev Med. 2011;40(1):61-66. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2010.09.027

23. Pal T, Cragun D, Lewis C, et al. A statewide survey of practitioners to assess knowledge and clinical practices regarding hereditary breast and ovarian cancer. Genet Test Mol Biomarkers. 2013;17(5):367-375. doi:10.1089/gtmb.2012.0381

24. Bensend TA, Veach PM, Niendorf KB. What’s the harm? Genetic counselor perceptions of adverse effects of genetics service provision by non-genetics professionals. J Genet Couns. 2014;23(1):48-63. doi:10.1007/s10897-013-9605-3

25. Teng I, Spigelman A. Attitudes and knowledge of medical practitioners to hereditary cancer clinics and cancer genetic testing. Fam Cancer. 2014;13(2):311-324. doi:10.1007/s10689-013-9695-y

26. Mikat-Stevens NA, Larson IA, Tarini BA. Primary-care providers’ perceived barriers to integration of genetics services: a systematic review of the literature. Genet Med. 2015;17(3):169-176. doi:10.1038/gim.2014.101

27. Scheuner MT, Hilborne L, Brown J, Lubin IM; members of the RAND Molecular Genetic Test Report Advisory Board. A report template for molecular genetic tests designed to improve communication between the clinician and laboratory. Genet Test Mol Biomarkers. 2012;16(7):761-769. doi:10.1089/gtmb.2011.0328

28. Scheuner MT, Peredo J, Tangney K, et al. Electronic health record interventions at the point of care improve documentation of care processes and decrease orders for genetic tests commonly ordered by nongeneticists. Genet Med. 2017;19(1):112-120. doi:10.1038/gim.2016.73

29. Cooksey JA, Forte G, Benkendorf J, Blitzer MG. The state of the medical geneticist workforce: findings of the 2003 survey of American Board of Medical Genetics certified geneticists. Genet Med. 2005;7(6):439-443. doi:10.1097/01.gim.0000172416.35285.9f

30. Institute of Medicine. Roundtable on Translating Genomic-Based Research for Health. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2009. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK26394. Accessed July 22, 2020.

31. Hoskovec JM, Bennett RL, Carey ME, et al. Projecting the supply and demand for certified genetic counselors: a workforce study. J Genet Couns. 2018;27(1):16-20. doi:10.1007/s10897-017-0158-8

32. Penon-Portmann M, Chang J, Cheng M, Shieh JT. Genetics workforce: distribution of genetics services and challenges to health care in California. Genet Med. 2020;22(1):227-231. doi:10.1038/s41436-019-0628-5

33. Spoont M, Greer N, Su J, Fitzgerald P, Rutks I, Wilt TJ. Rural vs. Urban Ambulatory Health Care: A Systematic Review. Washington, DC: US Department of Veterans Affairs; 2011. https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/publications/esp/ambulatory.cfm. Accessed July 21, 2020.

34. Mehrotra A, Forrest CB, Lin CY. Dropping the baton: specialty referrals in the United States. Milbank Q. 2011;89(1):39-68. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0009.2011.00619.x

35. Walsh J, Harrison JD, Young JM, Butow PN, Solomon MJ, Masya L. What are the current barriers to effective cancer care coordination? A qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10:132. Published 2010 May 20. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-10-132

36. McDonald KM, Schultz E, Albin L, et al. Care Coordination Measures Atlas. Version 4. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Publication No. 14-0037. https://www.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/publications/files/ccm_atlas.pdf. Updated June 2014. Accessed July 22, 2020.

37. Greenwood-Lee J, Jewett L, Woodhouse L, Marshall DA. A categorisation of problems and solutions to improve patient referrals from primary to specialty care. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):986. Published 2018 Dec 20. doi:10.1186/s12913-018-3745-y

38. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Academic Affiliations. Our medical and dental training program. https://www.va.gov/oaa/gme_default.asp. Updated January 7, 2020. Accessed July 21, 2020.

39. Scheuner MT, Marshall N, Lanto A, et al. Delivery of clinical genetic consultative services in the Veterans Health Administration. Genet Med. 2014;16(8):609-619. doi:10.1038/gim.2013.202.

40. Battista RN, Blancquaert I, Laberge AM, van Schendel N, Leduc N. Genetics in health care: an overview of current and emerging models. Public Health Genomics. 2012;15(1):34-45. doi:10.1159/000328846

41. Emery J. The GRAIDS Trial: the development and evaluation of computer decision support for cancer genetic risk assessment in primary care. Ann Hum Biol. 2005;32(2):218-227. doi:10.1080/03014460500074921

42. Scheuner MT, Hamilton AB, Peredo J, et al. A cancer genetics toolkit improves access to genetic services through documentation and use of the family history by primary-care clinicians. Genet Med. 2014;16(1):60-69. doi:10.1038/gim.2013.75

43. Scheuner MT, Peredo J, Tangney K, et al. Electronic health record interventions at the point of care improve documentation of care processes and decrease orders for genetic tests commonly ordered by nongeneticists. Genet Med. 2017;19(1):112-120. doi:10.1038/gim.2016.73

44. Hamilton AB, Oishi S, Yano EM, Gammage CE, Marshall NJ, Scheuner MT. Factors influencing organizational adoption and implementation of clinical genetic services. Genet Med. 2014;16(3):238-245. doi:10.1038/gim.2013.101

45. Sperber NR, Andrews SM, Voils CI, Green GL, Provenzale D, Knight S. Barriers and facilitators to adoption of genomic services for colorectal care within the Veterans Health Administration. J Pers Med. 2016;6(2):16. Published 2016 Apr 28. doi:10.3390/jpm6020016

46. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Health Services Research and Development. Genomics. https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/research/portfolio_description.cfm?Sulu=17. Updated July 21, 2020. Accessed June 22, 2020.

The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) oversees the largest integrated health care system in the nation, administering care to 9 million veterans annually throughout its distributed network of 1,255 medical centers and outpatient facilities. Every year, about 50,000 veterans are diagnosed with and treated for cancer in the VA, representing about 3% of all cancer cases in the US.1 After skin cancer, prostate, colon, and lung cancers are the most common among veterans.1 One way that VA has sought to improve the care of its large cancer patient population is through the adoption of precision oncology, an ever-evolving practice of analyzing an individual patient’s cancer to inform clinical decision making. Most often, the analysis includes conducting genetic testing of the tumor itself. Here, we describe the opportunities and challenges of integrating germline genetics into precision oncology practice.

The Intersection of Precision Oncology and Germline Genetics

Precision oncology typically refers to genetic testing of tumor DNA to identify genetic variants with potential diagnostic, prognostic, or predictive therapeutic implications. It is enabled by a growing body of knowledge that identifies key drivers of cancer development, coupled with advances in tumor analysis by next-generation sequencing and other technologies and by the availability of new and repurposed therapeutic agents.2 Precision oncology has transformed cancer care by targeting both common and rare malignancies with specific therapies that improve clinical outcomes in patients.3

Testing of tumor DNA can reveal both somatic (acquired) and germline (inherited) gene variants. Precision oncology testing strategies can include tumor-only testing with or without subtraction of suspected germline variants, or paired tumor-normal testing with explicit analysis and reporting of genes associated with germline predisposition.2 With tumor-only testing, the germline status of variants may be inferred and follow-up germline testing in normal tissue such as blood or saliva can be considered. Paired tumor-normal testing provides distinct advantages over tumor-only testing, including improvement of the mutation detection rate in tumors and streamlining interpretation of results for both the tumor and germline tests.

Regardless of the strategy used, tumor testing has the potential to uncover clinically relevant germline variation associated with heritable cancer susceptibility and other conditions, as well as carrier status for autosomal recessive disorders (eAppendix

Germline genetic information, independent of somatic variation, can influence the choice of targeted cancer therapies. For example, Mandelker and colleagues identified germline variants that would impact the treatment of 38 (3.7%) of 1,040 patients with cancer.4 Individuals with a germline pathogenic variant in a DNA repair gene (eg, BRCA1, BRCA2, ATM, CHEK2) are candidates for platinum chemotherapy and poly-(adenosine diphosphate-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors that target the inability of a tumor to repair double-stranded DNA breaks.5,6 Individuals with a germline pathogenic variant in the MSH2, MLH1, MSH6, PMS2 or EPCAM genes (ie, Lynch syndrome) have tumors that are deficient in mismatch repair, and these tumors are responsive to inhibitors of the programmed death 1 (PD1) pathway.7,8

In addition to changing treatment decisions, identifying pathogenic germline variants can have health, reproductive, and psychosocial implications for the patient and the patient’s family members.9,10 A pathogenic germline variant can imply disease risk for both the patient and his or her relatives. In these cases, it is important to ascertain family history, understand the mode of inheritance, identify at-risk relatives, review the associated phenotype, and discuss management and prevention options for the patient and for family members. For example, a germline pathogenic variant in the BRCA2 gene is associated with increased risk for breast, ovarian, pancreatic, gastric, bile duct, and laryngeal cancer, and melanoma.11 Knowledge of these increased cancer risks could inform cancer prevention and early detection options, such as more frequent and intensive surveillance starting at younger ages compared with that of average-risk individuals, use of chemoprevention treatments, and for those at highest risk, risk-reducing surgical procedures. Therefore, reporting germline test results requires the clinician to take on additional responsibilities beyond those required when reporting only somatic variants.

Because of the complexities inherent in germline genetic testing, it traditionally is offered in the context of a genetic consultation, comprised of genetic evaluation and genetic counseling (Figure). Clinical geneticists are physicians certified by the American Board of Medical Genetics and Genomics (a member board of the American Board of Medical Specialties) who received special training in the diagnosis and management of medical genetic conditions; they are trained to perform all aspects of a genetic consultation across the clinical spectrum and lifespan of a patient.12 In contrast, genetic counselors have a master’s degree in genetic counseling, a communication process that facilitates patient decision making surrounding the genetic evaluation.13 Most work as members of a team to ensure provision of comprehensive clinical genetic services. Genetic counselors are licensed in most states, and licensure in some states sanctions the ordering of genetic tests by genetic counselors. Genetics nurses are licensed professional nurses with special education and training in genetics who function in diverse roles in industry, education, research, and clinical care.14 Genetics nurses in clinical care perform risk assessment based on personal and family history, recognize and identify genetic conditions and predispositions, and discuss the implications of this with patients and their families. Advanced practice nurses (APRNs) have additional training that allows for diagnosis, interpretation of results, and surveillance and management recommendations.15

Germline Genetic Testing Challenges

Integrating germline genetic testing in precision oncology practice presents challenges at the patient, family, health care provider, and health system levels. Due to these challenges, implementation planning is obligatory, as germline testing has become a standard-of-care for certain tumor types and patients.2

On learning of a germline pathogenic variant or variant of uncertain significance, patients may experience distress and anxiety, especially in the short term.16-18 In addition, it can be difficult for patients to share germline genetic test results with their family; parents may feel guilty about the possibility of passing on a predisposition to children, and unaffected siblings may experience survivor guilt. For some veterans, there can be concerns about losing service-connected benefits if a genetic factor is found to contribute to their cancer history. In addition, patients may have concerns about discrimination by employers or insurers, including commercial health insurance or long-term care, disability, and life insurance. Yet there are many state and federal laws that ensure some protection from employment and health insurance discrimination based on genetic information.

For cancer care clinicians, incorporating germline testing requires additional responsibilities that can complicate care. Prior to germline genetic testing, genetic counseling with patients is recommended to review the potential benefits, harms, and limitations of genetic testing. Further, posttest genetic counseling is recommended to help the patient understand how the results may influence future cancer risks, provide recommendations for cancer management and prevention, and discuss implications for family members.9,10 While patients trust their health care providers to help them access and understand their genetic information, most health care providers are unprepared to integrate genetics into their practice; they lack adequate knowledge, skills, and confidence about genetics to effectively deliver genetic services.19-26 This leads to failure to recognize patients with indications for genetic testing, which often is due to insufficient family history collection. Other errors can include offering germline genetic testing to patients without appropriate indications and with inadequate informed consent procedures. When genetic testing is pursued, lack of knowledge about genetic principles and testing methods can lead to misinterpretation and miscommunication of results, contributing to inappropriate management recommendations. These errors can contribute to under-use, overuse, or misuse of genetic testing that can compromise the quality of patient care.27,28 With this in mind, thought must be given at the health care system level to develop effective strategies to deliver genetic services to patients. These strategies must address workforce capacity, organizational structure, and education.

Workforce Capacity

The VA clinical genetics workforce needs to expand to keep pace with increasing demand, which will be accelerated by the precision oncology programs for prostate and lung cancers and the VA Teleoncology initiative. In the US there are 10 to 15 genetics professionals per 1,000,000 residents.29-31 Most genetics professionals work in academic and metropolitan settings, leaving suburban and rural areas underserved. For example, in California, some patients travel up to 386 miles for genetics care (mean, 76.6 miles).32 In the VA, there are only 1 to 2 genetics professionals per 1 million enrollees, about 10-fold fewer than in community care. Meeting clinical needs of patients at the VA is particularly challenging because more than one-third of veterans live in rural areas.33

We recently surveyed genetics professionals in the VA about their practices and capacity to increase patient throughput (Table). Currently in the VA, there are 8 clinical geneticists, not all of whom practice clinical genetics, and 13 genetic counselors. Five VA programs provide clinical genetic services to local and nearby VA facilities near Boston, Massachusetts; Houston, Texas; Los Angeles and San Francisco, California; and Salt Lake City, Utah. These programs, first developed in 2008, typically are staffed by 1 or 2 genetics professionals. Most patients who are referred to the VA genetics programs are evaluated for hereditary cancer syndromes. Multiple modes of delivery may be used, including in-person, telehealth, telephone, and provider-to-provider e-consults in the EHR.

In 2010, in response to increased demand for clinical genetics services, the VA launched the Genomic Medicine Service (GMS), a national program with a centralized team of 9 genetic counselors based in Salt Lake City. GMS provides telehealth genetic counseling services exclusively to veterans onsite and at about 90 VA facilities across the country. More recently, the addition of a clinical geneticist and APRN with genetics expertise has allowed GMS to provide more comprehensive genetic consultative services.

All VA genetics programs are currently at full capacity with long waits for an appointment. To expand clinical genetic services, the VA genetics professionals responding to our survey reported a need for additional support (eg, administrative, care coordination, clinical), resources (eg, clinical space, salary support), and organizational change (eg, division of Medical Genetics at facility level, services provided at the level of the Veterans Integrated Service Network). Given the dearth of genetic care providers in the community, referral to non-VA care is not a viable option in many markets. In addition, avoiding referral outside of the VA could help to ensure continuity of care, more efficient care, and reduce the risk of duplication of testing, and polypharmacy.34-37

As part of its precision oncology initiative, VA is focusing on building clinical genetics services capacity. To increase access to clinical genetic services and appropriate genetic testing, the VA needs more genetics professionals, including clinical geneticists, genetic counselors, and genetic nurses–ideally a workforce study could be performed to inform the right staffing mix needed. To grow the genetics workforce in the long term, the VA could leverage its academic affiliations to train the next generation of genetics professionals. The VA has an important role in training medical professionals. By forming affiliations with medical schools and universities, the VA has become the largest provider of health care training in the US.38

Genetic Health Care Organization in the VA

Understanding a patient’s genetic background increasingly has become more and more important in the clinic, which necessitates a major shift in health care. Unfortunately, on a national scale, the number of clinical genetics professionals has not kept pace with the need-limiting the ability to grow the traditional genetics workforce in the VA in the near term.29-31 Thus, we must look to alternative genetic health care models in which other members of the health care team assume some of the genetic evaluation and counseling activities while caring for their cancer patients with referral to a clinical genetics team, as needed.39

Two genetic health care models have been described.40 Traditionally, clinical genetic services are coordinated between genetics professionals and other clinicians, organized as a regional genetics center and usually affiliated with an academic medical center. By contrast, the nontraditional genetic health care model integrates genetic services within primary and specialty care. Under the new approach, nongeneticists can be assisted by decision support tools in the EHR that help with assessing family history risk, identifying indications for genetic testing, and suggesting management options based on genetic test results.41-43

The VA National Precision Oncology Program (NPOP) is shaped by a commitment to be a high reliability organization (HRO). As such, the goal is to create a system of excellence that integrates precision medicine, implementation science, and the learning health care system to improve the health and health care of veterans with cancer. This initiative is establishing the foundations for best-in-class cancer care to enable veterans access to life-saving therapies through a concerted effort that began with the Cancer Moonshot, development of the NPOP, and collaborations with the VA Office of Research and Development. One of the fundamental objectives of this initiative is to implement strategies that ensure clinical genetic services are available to veterans receiving cancer care at all VA facilities and to extend these services to veterans in remote geographic locations nationwide. The initiative aims to synergize VA Teleoncology services that seek to deliver best-in-class oncology care across the VA enterprise using cutting-edge technologies.

Conclusions

To accomplish the goal of delivering world-class clinical genetic services to veterans and meet the increasing needs of precision oncology and support quality genetic health care, the VA must develop an integrated system of genetic health care that will have a network of clinical genetics that interfaces with other clinical and operational programs, genomics researchers, and educational programs to support quality genetic health care. The VA has highly qualified and dedicated genetics professionals at many sites across the country. Connecting them could create powerful synergies that would benefit patients and strengthen the genetics workforce. The clinical genetics network will enable development and dissemination of evidence-based policies, protocols, and clinical pathways for genomic medicine. This will help to identify, benchmark, and promote best practices for clinical genetic services, and increase access, increase efficiencies, and reduce variability in the care delivered.

The VA is well positioned to achieve successful implementation of genetic services given its investment in genomic medicine and the commitment of the VA NPOP. However, there is a need for structured and targeted implementation strategies for genetic services in the VA, as uptake of this innovation will not occur by passive diffusion.44,45 To keep pace with the demand for germline testing in veterans, VA may want to consider an outsized focus on training genetics professionals, given the high demand for this expertise. Perhaps most importantly, the VA will need to better prepare its frontline clinical workforce to integrate genetics into their practice. This could be facilitated by identifying implementation strategies and educational programs for genomic medicine that help clinicians to think genetically while caring for their patients, performing aspects of family history risk assessment and pre- and posttest genetic counseling as they are able, and referring complex cases to the clinical genetics network when needed.

Much is already known on how best to accomplish this through studies conducted by many talented VA health services researchers.46 Crucially, clinical tools embedded within the VA EHR will be fundamental to these efforts by facilitating identification of patients who can benefit from genetic services and genetic testing at the point of care. Through integration of VA research with clinical genetic services, the VA will become more prepared to realize the promise of genomic medicine for veterans.

Acknowledgments

We thank the members of the Genomic Medicine Program Advisory Committee, Clinical Genetics Subcommittee for providing input and guidance on the topics included in this article.

The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) oversees the largest integrated health care system in the nation, administering care to 9 million veterans annually throughout its distributed network of 1,255 medical centers and outpatient facilities. Every year, about 50,000 veterans are diagnosed with and treated for cancer in the VA, representing about 3% of all cancer cases in the US.1 After skin cancer, prostate, colon, and lung cancers are the most common among veterans.1 One way that VA has sought to improve the care of its large cancer patient population is through the adoption of precision oncology, an ever-evolving practice of analyzing an individual patient’s cancer to inform clinical decision making. Most often, the analysis includes conducting genetic testing of the tumor itself. Here, we describe the opportunities and challenges of integrating germline genetics into precision oncology practice.

The Intersection of Precision Oncology and Germline Genetics

Precision oncology typically refers to genetic testing of tumor DNA to identify genetic variants with potential diagnostic, prognostic, or predictive therapeutic implications. It is enabled by a growing body of knowledge that identifies key drivers of cancer development, coupled with advances in tumor analysis by next-generation sequencing and other technologies and by the availability of new and repurposed therapeutic agents.2 Precision oncology has transformed cancer care by targeting both common and rare malignancies with specific therapies that improve clinical outcomes in patients.3

Testing of tumor DNA can reveal both somatic (acquired) and germline (inherited) gene variants. Precision oncology testing strategies can include tumor-only testing with or without subtraction of suspected germline variants, or paired tumor-normal testing with explicit analysis and reporting of genes associated with germline predisposition.2 With tumor-only testing, the germline status of variants may be inferred and follow-up germline testing in normal tissue such as blood or saliva can be considered. Paired tumor-normal testing provides distinct advantages over tumor-only testing, including improvement of the mutation detection rate in tumors and streamlining interpretation of results for both the tumor and germline tests.

Regardless of the strategy used, tumor testing has the potential to uncover clinically relevant germline variation associated with heritable cancer susceptibility and other conditions, as well as carrier status for autosomal recessive disorders (eAppendix

Germline genetic information, independent of somatic variation, can influence the choice of targeted cancer therapies. For example, Mandelker and colleagues identified germline variants that would impact the treatment of 38 (3.7%) of 1,040 patients with cancer.4 Individuals with a germline pathogenic variant in a DNA repair gene (eg, BRCA1, BRCA2, ATM, CHEK2) are candidates for platinum chemotherapy and poly-(adenosine diphosphate-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors that target the inability of a tumor to repair double-stranded DNA breaks.5,6 Individuals with a germline pathogenic variant in the MSH2, MLH1, MSH6, PMS2 or EPCAM genes (ie, Lynch syndrome) have tumors that are deficient in mismatch repair, and these tumors are responsive to inhibitors of the programmed death 1 (PD1) pathway.7,8

In addition to changing treatment decisions, identifying pathogenic germline variants can have health, reproductive, and psychosocial implications for the patient and the patient’s family members.9,10 A pathogenic germline variant can imply disease risk for both the patient and his or her relatives. In these cases, it is important to ascertain family history, understand the mode of inheritance, identify at-risk relatives, review the associated phenotype, and discuss management and prevention options for the patient and for family members. For example, a germline pathogenic variant in the BRCA2 gene is associated with increased risk for breast, ovarian, pancreatic, gastric, bile duct, and laryngeal cancer, and melanoma.11 Knowledge of these increased cancer risks could inform cancer prevention and early detection options, such as more frequent and intensive surveillance starting at younger ages compared with that of average-risk individuals, use of chemoprevention treatments, and for those at highest risk, risk-reducing surgical procedures. Therefore, reporting germline test results requires the clinician to take on additional responsibilities beyond those required when reporting only somatic variants.

Because of the complexities inherent in germline genetic testing, it traditionally is offered in the context of a genetic consultation, comprised of genetic evaluation and genetic counseling (Figure). Clinical geneticists are physicians certified by the American Board of Medical Genetics and Genomics (a member board of the American Board of Medical Specialties) who received special training in the diagnosis and management of medical genetic conditions; they are trained to perform all aspects of a genetic consultation across the clinical spectrum and lifespan of a patient.12 In contrast, genetic counselors have a master’s degree in genetic counseling, a communication process that facilitates patient decision making surrounding the genetic evaluation.13 Most work as members of a team to ensure provision of comprehensive clinical genetic services. Genetic counselors are licensed in most states, and licensure in some states sanctions the ordering of genetic tests by genetic counselors. Genetics nurses are licensed professional nurses with special education and training in genetics who function in diverse roles in industry, education, research, and clinical care.14 Genetics nurses in clinical care perform risk assessment based on personal and family history, recognize and identify genetic conditions and predispositions, and discuss the implications of this with patients and their families. Advanced practice nurses (APRNs) have additional training that allows for diagnosis, interpretation of results, and surveillance and management recommendations.15

Germline Genetic Testing Challenges

Integrating germline genetic testing in precision oncology practice presents challenges at the patient, family, health care provider, and health system levels. Due to these challenges, implementation planning is obligatory, as germline testing has become a standard-of-care for certain tumor types and patients.2

On learning of a germline pathogenic variant or variant of uncertain significance, patients may experience distress and anxiety, especially in the short term.16-18 In addition, it can be difficult for patients to share germline genetic test results with their family; parents may feel guilty about the possibility of passing on a predisposition to children, and unaffected siblings may experience survivor guilt. For some veterans, there can be concerns about losing service-connected benefits if a genetic factor is found to contribute to their cancer history. In addition, patients may have concerns about discrimination by employers or insurers, including commercial health insurance or long-term care, disability, and life insurance. Yet there are many state and federal laws that ensure some protection from employment and health insurance discrimination based on genetic information.

For cancer care clinicians, incorporating germline testing requires additional responsibilities that can complicate care. Prior to germline genetic testing, genetic counseling with patients is recommended to review the potential benefits, harms, and limitations of genetic testing. Further, posttest genetic counseling is recommended to help the patient understand how the results may influence future cancer risks, provide recommendations for cancer management and prevention, and discuss implications for family members.9,10 While patients trust their health care providers to help them access and understand their genetic information, most health care providers are unprepared to integrate genetics into their practice; they lack adequate knowledge, skills, and confidence about genetics to effectively deliver genetic services.19-26 This leads to failure to recognize patients with indications for genetic testing, which often is due to insufficient family history collection. Other errors can include offering germline genetic testing to patients without appropriate indications and with inadequate informed consent procedures. When genetic testing is pursued, lack of knowledge about genetic principles and testing methods can lead to misinterpretation and miscommunication of results, contributing to inappropriate management recommendations. These errors can contribute to under-use, overuse, or misuse of genetic testing that can compromise the quality of patient care.27,28 With this in mind, thought must be given at the health care system level to develop effective strategies to deliver genetic services to patients. These strategies must address workforce capacity, organizational structure, and education.

Workforce Capacity

The VA clinical genetics workforce needs to expand to keep pace with increasing demand, which will be accelerated by the precision oncology programs for prostate and lung cancers and the VA Teleoncology initiative. In the US there are 10 to 15 genetics professionals per 1,000,000 residents.29-31 Most genetics professionals work in academic and metropolitan settings, leaving suburban and rural areas underserved. For example, in California, some patients travel up to 386 miles for genetics care (mean, 76.6 miles).32 In the VA, there are only 1 to 2 genetics professionals per 1 million enrollees, about 10-fold fewer than in community care. Meeting clinical needs of patients at the VA is particularly challenging because more than one-third of veterans live in rural areas.33

We recently surveyed genetics professionals in the VA about their practices and capacity to increase patient throughput (Table). Currently in the VA, there are 8 clinical geneticists, not all of whom practice clinical genetics, and 13 genetic counselors. Five VA programs provide clinical genetic services to local and nearby VA facilities near Boston, Massachusetts; Houston, Texas; Los Angeles and San Francisco, California; and Salt Lake City, Utah. These programs, first developed in 2008, typically are staffed by 1 or 2 genetics professionals. Most patients who are referred to the VA genetics programs are evaluated for hereditary cancer syndromes. Multiple modes of delivery may be used, including in-person, telehealth, telephone, and provider-to-provider e-consults in the EHR.

In 2010, in response to increased demand for clinical genetics services, the VA launched the Genomic Medicine Service (GMS), a national program with a centralized team of 9 genetic counselors based in Salt Lake City. GMS provides telehealth genetic counseling services exclusively to veterans onsite and at about 90 VA facilities across the country. More recently, the addition of a clinical geneticist and APRN with genetics expertise has allowed GMS to provide more comprehensive genetic consultative services.

All VA genetics programs are currently at full capacity with long waits for an appointment. To expand clinical genetic services, the VA genetics professionals responding to our survey reported a need for additional support (eg, administrative, care coordination, clinical), resources (eg, clinical space, salary support), and organizational change (eg, division of Medical Genetics at facility level, services provided at the level of the Veterans Integrated Service Network). Given the dearth of genetic care providers in the community, referral to non-VA care is not a viable option in many markets. In addition, avoiding referral outside of the VA could help to ensure continuity of care, more efficient care, and reduce the risk of duplication of testing, and polypharmacy.34-37

As part of its precision oncology initiative, VA is focusing on building clinical genetics services capacity. To increase access to clinical genetic services and appropriate genetic testing, the VA needs more genetics professionals, including clinical geneticists, genetic counselors, and genetic nurses–ideally a workforce study could be performed to inform the right staffing mix needed. To grow the genetics workforce in the long term, the VA could leverage its academic affiliations to train the next generation of genetics professionals. The VA has an important role in training medical professionals. By forming affiliations with medical schools and universities, the VA has become the largest provider of health care training in the US.38

Genetic Health Care Organization in the VA

Understanding a patient’s genetic background increasingly has become more and more important in the clinic, which necessitates a major shift in health care. Unfortunately, on a national scale, the number of clinical genetics professionals has not kept pace with the need-limiting the ability to grow the traditional genetics workforce in the VA in the near term.29-31 Thus, we must look to alternative genetic health care models in which other members of the health care team assume some of the genetic evaluation and counseling activities while caring for their cancer patients with referral to a clinical genetics team, as needed.39

Two genetic health care models have been described.40 Traditionally, clinical genetic services are coordinated between genetics professionals and other clinicians, organized as a regional genetics center and usually affiliated with an academic medical center. By contrast, the nontraditional genetic health care model integrates genetic services within primary and specialty care. Under the new approach, nongeneticists can be assisted by decision support tools in the EHR that help with assessing family history risk, identifying indications for genetic testing, and suggesting management options based on genetic test results.41-43

The VA National Precision Oncology Program (NPOP) is shaped by a commitment to be a high reliability organization (HRO). As such, the goal is to create a system of excellence that integrates precision medicine, implementation science, and the learning health care system to improve the health and health care of veterans with cancer. This initiative is establishing the foundations for best-in-class cancer care to enable veterans access to life-saving therapies through a concerted effort that began with the Cancer Moonshot, development of the NPOP, and collaborations with the VA Office of Research and Development. One of the fundamental objectives of this initiative is to implement strategies that ensure clinical genetic services are available to veterans receiving cancer care at all VA facilities and to extend these services to veterans in remote geographic locations nationwide. The initiative aims to synergize VA Teleoncology services that seek to deliver best-in-class oncology care across the VA enterprise using cutting-edge technologies.

Conclusions

To accomplish the goal of delivering world-class clinical genetic services to veterans and meet the increasing needs of precision oncology and support quality genetic health care, the VA must develop an integrated system of genetic health care that will have a network of clinical genetics that interfaces with other clinical and operational programs, genomics researchers, and educational programs to support quality genetic health care. The VA has highly qualified and dedicated genetics professionals at many sites across the country. Connecting them could create powerful synergies that would benefit patients and strengthen the genetics workforce. The clinical genetics network will enable development and dissemination of evidence-based policies, protocols, and clinical pathways for genomic medicine. This will help to identify, benchmark, and promote best practices for clinical genetic services, and increase access, increase efficiencies, and reduce variability in the care delivered.

The VA is well positioned to achieve successful implementation of genetic services given its investment in genomic medicine and the commitment of the VA NPOP. However, there is a need for structured and targeted implementation strategies for genetic services in the VA, as uptake of this innovation will not occur by passive diffusion.44,45 To keep pace with the demand for germline testing in veterans, VA may want to consider an outsized focus on training genetics professionals, given the high demand for this expertise. Perhaps most importantly, the VA will need to better prepare its frontline clinical workforce to integrate genetics into their practice. This could be facilitated by identifying implementation strategies and educational programs for genomic medicine that help clinicians to think genetically while caring for their patients, performing aspects of family history risk assessment and pre- and posttest genetic counseling as they are able, and referring complex cases to the clinical genetics network when needed.

Much is already known on how best to accomplish this through studies conducted by many talented VA health services researchers.46 Crucially, clinical tools embedded within the VA EHR will be fundamental to these efforts by facilitating identification of patients who can benefit from genetic services and genetic testing at the point of care. Through integration of VA research with clinical genetic services, the VA will become more prepared to realize the promise of genomic medicine for veterans.

Acknowledgments

We thank the members of the Genomic Medicine Program Advisory Committee, Clinical Genetics Subcommittee for providing input and guidance on the topics included in this article.

1. Zullig LL, Sims KJ, McNeil R, et al. Cancer incidence among patients of the U.S. Veterans Affairs Health Care System: 2010 update. Mil Med. 2017;182(7):e1883-e1891. doi:10.7205/MILMED-D-16-00371

2. Li MM, Chao E, Esplin ED, et al. Points to consider for reporting of germline variation in patients undergoing tumor testing: a statement of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG). Genet Med. 2020;22(7):1142-1148. doi:10.1038/s41436-020-0783-8

3. Malone ER, Oliva M, Sabatini PJB, Stockley TL, Siu LL. Molecular profiling for precision cancer therapies. Genome Med. 2020;12(1):8. Published 2020 Jan 14. doi:10.1186/s13073-019-0703-1

4. Mandelker D, Zhang L, Kemel Y, et al. Mutation detection in patients with advanced cancer by universal sequencing of cancer-related genes in tumor and normal DNA vs guideline-based germline testing [published correction appears in JAMA. 2018 Dec 11;320(22):2381]. JAMA. 2017;318(9):825-835. doi:10.1001/jama.2017.11137

5. Mateo J, Carreira S, Sandhu S, et al. DNA-repair defects and olaparib in metastatic prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(18):1697-1708. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1506859

6. Ratta R, Guida A, Scotté F, et al. PARP inhibitors as a new therapeutic option in metastatic prostate cancer: a systematic review [published online ahead of print, 2020 May 4]. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2020;10.1038/s41391-020-0233-3. doi:10.1038/s41391-020-0233-3

7. Le DT, Uram JN, Wang H, et al. PD-1 Blockade in tumors with mismatch-repair deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(26):2509-2520. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1500596

8. Graham LS, Montgomery B, Cheng HH, et al. Mismatch repair deficiency in metastatic prostate cancer: Response to PD-1 blockade and standard therapies. PLoS One. 2020;15(5):e0233260. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0233260

9. Robson ME, Storm CD, Weitzel J, Wollins DS, Offit K; American Society of Clinical Oncology. American Society of Clinical Oncology policy statement update: genetic and genomic testing for cancer susceptibility. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(5):893-901. doi:10.1200/JCO.2009.27.0660

10. Riley BD, Culver JO, Skrzynia C, et al. Essential elements of genetic cancer risk assessment, counseling, and testing: updated recommendations of the National Society of Genetic Counselors. J Genet Couns. 2012;21(2):151-161. doi:10.1007/s10897-011-9462-x

11. Petrucelli N, Daly MB, Pal T. BRCA1- and BRCA2-associated hereditary breast and ovarian cancer. In: Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Pagon RA, et al, eds. GeneReviews. Seattle, WA: University of Washington, Seattle; 1993.

12. ACMG Board of Directors. Scope of practice: a statement of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG). Genet Med. 2015;17(9):e3. doi:10.1038/gim.2015.94

13. National Society of Genetic Counselors’ Definition Task Force, Resta R, Biesecker BB, et al. A new definition of Genetic Counseling: National Society of Genetic Counselors’ Task Force report. J Genet Couns. 2006;15(2):77-83. doi:10.1007/s10897-005-9014-3

14. Calzone KA, Cashion A, Feetham S, et al. Nurses transforming health care using genetics and genomics [published correction appears in Nurs Outlook. 2010;58(3):163]. Nurs Outlook. 2010;58(1):26-35. doi:10.1016/j.outlook.2009.05.001

15. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Nursing Services. 2018 Office of Nursing Services (ONS) Annual Brief. https://www.va.gov/nursing/docs/about/2018_ONS_Annual_Report_Brief.pdf. Accessed July 21, 2020.

16. Lerman C, Croyle RT. Emotional and behavioral responses to genetic testing for susceptibility to cancer. Oncology (Williston Park). 1996;10(2):191-202.

17. Bonadona V, Saltel P, Desseigne F, et al. Cancer patients who experienced diagnostic genetic testing for cancer susceptibility: reactions and behavior after the disclosure of a positive test result. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2002;11(1):97-104.

18. Murakami Y, Okamura H, Sugano K, et al. Psychologic distress after disclosure of genetic test results regarding hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal carcinoma. Cancer. 2004;101(2):395-403. doi:10.1002/cncr.20363

19. Brierley KL, Campfield D, Ducaine W, et al. Errors in delivery of cancer genetics services: implications for practice. Conn Med. 2010;74(7):413-423.

20. Dhar SU, Cooper HP, Wang T, et al. Significant differences among physician specialties in management recommendations of BRCA1 mutation carriers. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;129(1):221-227. doi:10.1007/s10549-011-1449-7

21. Plon SE, Cooper HP, Parks B, et al. Genetic testing and cancer risk management recommendations by physicians for at-risk relatives. Genet Med. 2011;13(2):148-154. doi:10.1097/GIM.0b013e318207f564

22. Bellcross CA, Kolor K, Goddard KA, Coates RJ, Reyes M, Khoury MJ. Awareness and utilization of BRCA1/2 testing among U.S. primary care physicians. Am J Prev Med. 2011;40(1):61-66. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2010.09.027

23. Pal T, Cragun D, Lewis C, et al. A statewide survey of practitioners to assess knowledge and clinical practices regarding hereditary breast and ovarian cancer. Genet Test Mol Biomarkers. 2013;17(5):367-375. doi:10.1089/gtmb.2012.0381

24. Bensend TA, Veach PM, Niendorf KB. What’s the harm? Genetic counselor perceptions of adverse effects of genetics service provision by non-genetics professionals. J Genet Couns. 2014;23(1):48-63. doi:10.1007/s10897-013-9605-3

25. Teng I, Spigelman A. Attitudes and knowledge of medical practitioners to hereditary cancer clinics and cancer genetic testing. Fam Cancer. 2014;13(2):311-324. doi:10.1007/s10689-013-9695-y

26. Mikat-Stevens NA, Larson IA, Tarini BA. Primary-care providers’ perceived barriers to integration of genetics services: a systematic review of the literature. Genet Med. 2015;17(3):169-176. doi:10.1038/gim.2014.101

27. Scheuner MT, Hilborne L, Brown J, Lubin IM; members of the RAND Molecular Genetic Test Report Advisory Board. A report template for molecular genetic tests designed to improve communication between the clinician and laboratory. Genet Test Mol Biomarkers. 2012;16(7):761-769. doi:10.1089/gtmb.2011.0328

28. Scheuner MT, Peredo J, Tangney K, et al. Electronic health record interventions at the point of care improve documentation of care processes and decrease orders for genetic tests commonly ordered by nongeneticists. Genet Med. 2017;19(1):112-120. doi:10.1038/gim.2016.73

29. Cooksey JA, Forte G, Benkendorf J, Blitzer MG. The state of the medical geneticist workforce: findings of the 2003 survey of American Board of Medical Genetics certified geneticists. Genet Med. 2005;7(6):439-443. doi:10.1097/01.gim.0000172416.35285.9f

30. Institute of Medicine. Roundtable on Translating Genomic-Based Research for Health. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2009. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK26394. Accessed July 22, 2020.

31. Hoskovec JM, Bennett RL, Carey ME, et al. Projecting the supply and demand for certified genetic counselors: a workforce study. J Genet Couns. 2018;27(1):16-20. doi:10.1007/s10897-017-0158-8

32. Penon-Portmann M, Chang J, Cheng M, Shieh JT. Genetics workforce: distribution of genetics services and challenges to health care in California. Genet Med. 2020;22(1):227-231. doi:10.1038/s41436-019-0628-5

33. Spoont M, Greer N, Su J, Fitzgerald P, Rutks I, Wilt TJ. Rural vs. Urban Ambulatory Health Care: A Systematic Review. Washington, DC: US Department of Veterans Affairs; 2011. https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/publications/esp/ambulatory.cfm. Accessed July 21, 2020.

34. Mehrotra A, Forrest CB, Lin CY. Dropping the baton: specialty referrals in the United States. Milbank Q. 2011;89(1):39-68. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0009.2011.00619.x

35. Walsh J, Harrison JD, Young JM, Butow PN, Solomon MJ, Masya L. What are the current barriers to effective cancer care coordination? A qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10:132. Published 2010 May 20. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-10-132

36. McDonald KM, Schultz E, Albin L, et al. Care Coordination Measures Atlas. Version 4. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Publication No. 14-0037. https://www.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/publications/files/ccm_atlas.pdf. Updated June 2014. Accessed July 22, 2020.

37. Greenwood-Lee J, Jewett L, Woodhouse L, Marshall DA. A categorisation of problems and solutions to improve patient referrals from primary to specialty care. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):986. Published 2018 Dec 20. doi:10.1186/s12913-018-3745-y

38. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Academic Affiliations. Our medical and dental training program. https://www.va.gov/oaa/gme_default.asp. Updated January 7, 2020. Accessed July 21, 2020.

39. Scheuner MT, Marshall N, Lanto A, et al. Delivery of clinical genetic consultative services in the Veterans Health Administration. Genet Med. 2014;16(8):609-619. doi:10.1038/gim.2013.202.

40. Battista RN, Blancquaert I, Laberge AM, van Schendel N, Leduc N. Genetics in health care: an overview of current and emerging models. Public Health Genomics. 2012;15(1):34-45. doi:10.1159/000328846

41. Emery J. The GRAIDS Trial: the development and evaluation of computer decision support for cancer genetic risk assessment in primary care. Ann Hum Biol. 2005;32(2):218-227. doi:10.1080/03014460500074921

42. Scheuner MT, Hamilton AB, Peredo J, et al. A cancer genetics toolkit improves access to genetic services through documentation and use of the family history by primary-care clinicians. Genet Med. 2014;16(1):60-69. doi:10.1038/gim.2013.75

43. Scheuner MT, Peredo J, Tangney K, et al. Electronic health record interventions at the point of care improve documentation of care processes and decrease orders for genetic tests commonly ordered by nongeneticists. Genet Med. 2017;19(1):112-120. doi:10.1038/gim.2016.73

44. Hamilton AB, Oishi S, Yano EM, Gammage CE, Marshall NJ, Scheuner MT. Factors influencing organizational adoption and implementation of clinical genetic services. Genet Med. 2014;16(3):238-245. doi:10.1038/gim.2013.101

45. Sperber NR, Andrews SM, Voils CI, Green GL, Provenzale D, Knight S. Barriers and facilitators to adoption of genomic services for colorectal care within the Veterans Health Administration. J Pers Med. 2016;6(2):16. Published 2016 Apr 28. doi:10.3390/jpm6020016

46. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Health Services Research and Development. Genomics. https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/research/portfolio_description.cfm?Sulu=17. Updated July 21, 2020. Accessed June 22, 2020.

1. Zullig LL, Sims KJ, McNeil R, et al. Cancer incidence among patients of the U.S. Veterans Affairs Health Care System: 2010 update. Mil Med. 2017;182(7):e1883-e1891. doi:10.7205/MILMED-D-16-00371

2. Li MM, Chao E, Esplin ED, et al. Points to consider for reporting of germline variation in patients undergoing tumor testing: a statement of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG). Genet Med. 2020;22(7):1142-1148. doi:10.1038/s41436-020-0783-8

3. Malone ER, Oliva M, Sabatini PJB, Stockley TL, Siu LL. Molecular profiling for precision cancer therapies. Genome Med. 2020;12(1):8. Published 2020 Jan 14. doi:10.1186/s13073-019-0703-1

4. Mandelker D, Zhang L, Kemel Y, et al. Mutation detection in patients with advanced cancer by universal sequencing of cancer-related genes in tumor and normal DNA vs guideline-based germline testing [published correction appears in JAMA. 2018 Dec 11;320(22):2381]. JAMA. 2017;318(9):825-835. doi:10.1001/jama.2017.11137

5. Mateo J, Carreira S, Sandhu S, et al. DNA-repair defects and olaparib in metastatic prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(18):1697-1708. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1506859

6. Ratta R, Guida A, Scotté F, et al. PARP inhibitors as a new therapeutic option in metastatic prostate cancer: a systematic review [published online ahead of print, 2020 May 4]. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2020;10.1038/s41391-020-0233-3. doi:10.1038/s41391-020-0233-3

7. Le DT, Uram JN, Wang H, et al. PD-1 Blockade in tumors with mismatch-repair deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(26):2509-2520. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1500596

8. Graham LS, Montgomery B, Cheng HH, et al. Mismatch repair deficiency in metastatic prostate cancer: Response to PD-1 blockade and standard therapies. PLoS One. 2020;15(5):e0233260. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0233260

9. Robson ME, Storm CD, Weitzel J, Wollins DS, Offit K; American Society of Clinical Oncology. American Society of Clinical Oncology policy statement update: genetic and genomic testing for cancer susceptibility. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(5):893-901. doi:10.1200/JCO.2009.27.0660

10. Riley BD, Culver JO, Skrzynia C, et al. Essential elements of genetic cancer risk assessment, counseling, and testing: updated recommendations of the National Society of Genetic Counselors. J Genet Couns. 2012;21(2):151-161. doi:10.1007/s10897-011-9462-x

11. Petrucelli N, Daly MB, Pal T. BRCA1- and BRCA2-associated hereditary breast and ovarian cancer. In: Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Pagon RA, et al, eds. GeneReviews. Seattle, WA: University of Washington, Seattle; 1993.

12. ACMG Board of Directors. Scope of practice: a statement of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG). Genet Med. 2015;17(9):e3. doi:10.1038/gim.2015.94

13. National Society of Genetic Counselors’ Definition Task Force, Resta R, Biesecker BB, et al. A new definition of Genetic Counseling: National Society of Genetic Counselors’ Task Force report. J Genet Couns. 2006;15(2):77-83. doi:10.1007/s10897-005-9014-3

14. Calzone KA, Cashion A, Feetham S, et al. Nurses transforming health care using genetics and genomics [published correction appears in Nurs Outlook. 2010;58(3):163]. Nurs Outlook. 2010;58(1):26-35. doi:10.1016/j.outlook.2009.05.001

15. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Nursing Services. 2018 Office of Nursing Services (ONS) Annual Brief. https://www.va.gov/nursing/docs/about/2018_ONS_Annual_Report_Brief.pdf. Accessed July 21, 2020.

16. Lerman C, Croyle RT. Emotional and behavioral responses to genetic testing for susceptibility to cancer. Oncology (Williston Park). 1996;10(2):191-202.

17. Bonadona V, Saltel P, Desseigne F, et al. Cancer patients who experienced diagnostic genetic testing for cancer susceptibility: reactions and behavior after the disclosure of a positive test result. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2002;11(1):97-104.

18. Murakami Y, Okamura H, Sugano K, et al. Psychologic distress after disclosure of genetic test results regarding hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal carcinoma. Cancer. 2004;101(2):395-403. doi:10.1002/cncr.20363

19. Brierley KL, Campfield D, Ducaine W, et al. Errors in delivery of cancer genetics services: implications for practice. Conn Med. 2010;74(7):413-423.