User login

Acquired Port-wine Stain With Superimposed Eczema Following Penetrating Abdominal Trauma

Port-wine stains (PWSs) are common congenital capillary vascular malformations with an incidence of 3 per 1000 neonates.1 Rarely, acquired PWSs are seen, sometimes appearing following trauma.2-5 Port-wine stains are diagnosed clinically and present as painless, partially or entirely blanchable pink patches that respect the median (midline) plane.6 Although histopathologic examination is not necessary for diagnosis of PWS, typical findings include dilated, ectatic capillaries.7,8 Since it was first reported by Traub9 in 1939, more than 60 cases of acquired PWSs have been reported.10 A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the search terms acquired port-wine stain and port-wine stain and eczema yielded no cases of acquired PWS with associated eczematous changes and only 30 cases of congenital PWS with superimposed eczema.11-18 We report the case of an acquired PWS with superimposed eczema in an 18-year-old man following penetrating abdominal trauma.

Case Report

An otherwise healthy 18-year-old man presented to our dermatology office for evaluation of an eruption that had developed at the site of an abdominal stab wound he sustained 2 to 3 years prior. One year after he was stabbed, the patient developed a nonpruritic, painless red patch located 1 cm anterior to the healed wound on the left abdomen. The patch gradually grew larger to involve the entire left abdomen, extending to the left lower back. The site of the healed stab wound also became raised and pruritic, and the patient noted another pruritic plaque that formed within the larger patch. The patient reported no other skin conditions prior to the current eruption. His medical history was notable for seasonal allergies and asthma, but no childhood eczema.

Physical examination revealed a healthy, well-nourished man with Fitzpatrick skin type IV. A red, purpuric, coalescent patch with slightly arcuate borders extending from the mid abdomen to the left posterior flank was noted. The left lateral aspect of the patch blanched with pressure and respected the median plane. Within the larger patch, a 4-cm×2-cm lichenified, slightly macerated, hyperpigmented plaque was noted at the site of the stab wound (Figure 1). Based on these clinical findings, a presumptive diagnosis of an acquired PWS with superimposed eczema was made.

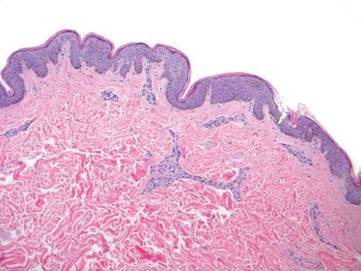

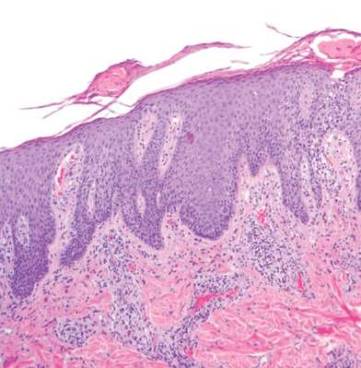

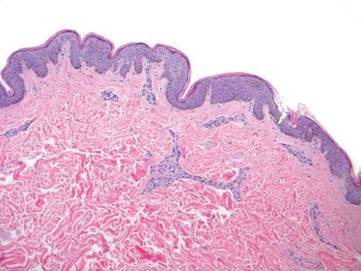

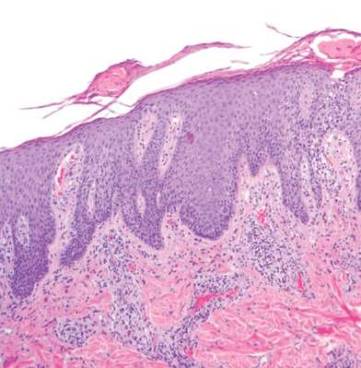

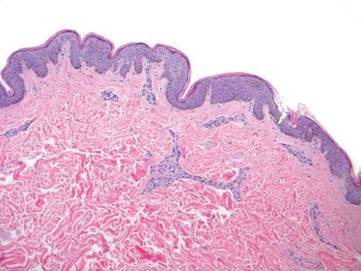

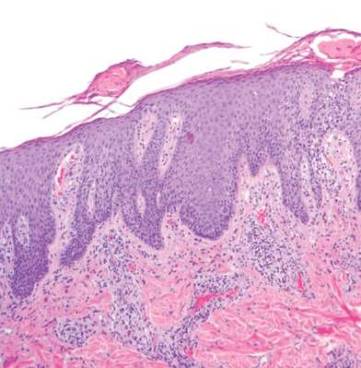

Punch biopsy specimens were taken from the large vascular patch and the smaller lichenified plaque. Histopathologic examination of the vascular patch showed an increased number of small vessels in the superficial dermis with thickened vessel walls, ectatic lumens, and no vasculopathy, consistent with a vascular malformation or a reactive vascular proliferation (Figure 2). On histopathology, the plaque showed epidermal spongiosis and hyperplasia with serum crust and a papillary dermis containing a mixed inflammatory infiltrate with occasional eosinophils, consistent with an eczematous dermatitis (Figure 3). The histologic findings confirmed the clinical diagnosis.

The pruritic, lichenified plaque improved with application of triamcinolone ointment 0.1% twice daily for 2 weeks. Magnetic resonance imaging to rule out an underlying arteriovenous malformation was recommended, but the patient declined.

Comment

The exact cause of PWS is unknown. There have been a multitude of genomic suspects for congenital lesions, including a somatic activating mutation (ie, a mutation acquired during fetal development) of the GNAQ (guanine nucleotide binding protein [G protein], q polypeptide) gene, which may contribute to abnormal cell proliferation including the regulation of blood vessels, and inactivating mutations in the RASA1 (RAS p21 protein activator [GTPase activating protein] 1) gene, which controls endothelial cell organization.19-22 Later mutations (ie, those occurring after the first trimester) may be more likely to result in isolated PWSs as opposed to syndromic PWSs.19 Whatever the source of genetic misinformation, it is thought that the diminished neuronal control of blood flow and the resulting alterations in dermal structure contribute to the pathogenesis of PWS and its associated histologic features.7,23

The clinical and histopathologic features of acquired PWSs are indistinguishable from those of congenital lesions, indicating that different processes may lead to the same presentation.4 Abnormal innervation and decreased supportive stroma have both been identified as contributing factors in the development of congenital and acquired PWSs.7,23-25 Rosen and Smoller23 found that diminished nerve density affects vascular tone and caliber in PWSs and had hypothesized in a prior report that decreased perivascular Schwann cells may indicate abnormal sympathetic innervation.7 Since then, PWS has been shown to lack both somatic and sensory innervation.24 Tsuji and Sawabe25 indicated that alterations to the perivascular stroma, whether congenital or as a result of trauma, decrease support for vessels, leading to ectasia.

In addition to an acquired PWS, our patient also had associated eczema within the PWS. Eczematous lesions were absent elsewhere, and he did not have a history of childhood eczema. Our review of the literature yielded 8 studies since 1996 that collectively described 30 cases of eczema within PWSs.11-18 Only 2 of these reports described adult patients with concomitant eczema and PWS and none described acquired PWS.13,18

Few studies have addressed the relationship between PWSs and eczema. It is unclear if concomitant PWS and localized eczema are collision dermatoses or if a PWS may predispose the affected skin to eczema.11-13 It has been hypothesized that the increased dermal vasculature in PWSs predisposes the skin to the development of eczema—more specifically, that ectasia may lead to increased inflammation.12,17 The concept of the “immunocompromised district” proposed by Ruocco et al26 is a unifying theory that may underlie the association noted between cases of trauma and later development of a PWS and superimposed eczematous dermatitis, such as in our case. Trauma is noted as one of a number of possible disruptive forces affecting both immunomodulation and neuromodulation within a local area of skin, leading to increased susceptibility of that district to various cutaneous diseases.26

Although our patient’s eczema responded to conservative treatment with a topical steroid, several case series have reported success with laser therapy in the treatment of PWS while preventing recurrence of associated eczematous dermatitis.12,17 Following the cessation of eczema treatment with topical steroid, which causes vasoconstriction, we suggest postponing laser therapy several weeks to allow resolution of vasoconstriction, thus providing enhanced therapeutic targeting with a vascular laser. Of particular relevance to our case, a recent study showed efficacy of the pulsed dye laser in treating PWSs in Fitzpatrick skin types IV and V.27

Conclusion

Although acquired PWS is rare, it can present later in life as an acquired lesion at a site of previous trauma.1-5 Congenital capillary malformations also can be associated with superimposed, localized eczema.11-18 We present a rarely reported case of an acquired PWS with superimposed, localized eczema. As in cases of congenital PWS with concomitant eczema, the associated eczema in our case was responsive to topical corticosteroid therapy. Additionally, pulsed dye laser has been shown to treat PWSs while preventing the recurrence of eczema, and it has been deemed effective for individuals with darker skin types.12,17, 27 Further studies are needed to explore the relationship between PWS and eczema.

- Jacobs AH, Walton RG. The incidence of birthmarks in the neonate. Pediatrics. 1976;58:218-222.

- Fegeler F. Naevus flammeus im trigeminusgebiet nach trauma im rahmen eines posttraumatisch-vegetativen syndroms. Arch Dermatol Syphilol. 1949;188:416-422.

- Kirkland CR, Mutasim DF. Acquired port-wine stain following repetitive trauma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:462-463.

- Adams BB, Lucky AW. Acquired port-wine stains and antecedent trauma: case report and review of the literature. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:897-899.

- Colver GB, Ryan TJ. Acquired port-wine stain. Arch Dermatol. 1986;122:1415-1416.

- Nigro J, Swerlick RA, Sepp NT, et al. Angiogenesis, vascular malformations and proliferations. In: Arndt KA, LeBoit PE, Robinson JK, Wintroub BU, eds. Cutaneous Medicine and Surgery: An Integrated Program in Dermatology. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders Co; 1996:1492-1521.

- Smoller BR, Rosen S. Port-wine stains. a disease of altered neural modulation of blood vessels? Arch Dermatol. 1986;122:177-179.

- Chang CJ, Yu JS, Nelson JS. Confocal microscopy study of neurovascular distribution in facial port wine stains(capillary malformation). J Formos Med Assoc. 2008;107:559-666.

- Traub EF. Naevus flammeus appearing at the age of twenty three. Arch Dermatol. 1939;39:752.

- Freysz M, Cribier B, Lipsker, D. Fegelers syndrome, acquired port-wine stain or acquired capillary malformation: three cases and a literature review [article in French]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2013;140:341-346.

- Tay YK, Morelli J, Weston WL. Inflammatory nuchal-occipital port-wine stains. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35:811-813.

- Sidwell RU, Syed S, Harper JI. Port-wine stains and eczema. Br J Dermatol. 2001;144:1269-1270.

- Hofer T. Meyerson phenomenon within a nevus flammeus. Dermatology. 2002;205:180-183.

- Raff K, Landthaler M, Hoheleutner U. Port-wine stains with eczema. Phlebologie. 2003;32:15-17.

- Tsuboi H, Miyata T, Katsuoka K. Eczema in a port-wine stain. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2003;28:322-323.

- Rajan N, Natarahan S. Impetiginized eczema arising within a port-wine stain of the arm. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:1009-1010.

- Fonder MA, Mamelak AJ, Kazin RA, et al. Port-wine-stain-associated dermatitis: implications for cutaneous vascular laser therapy. Pediatr Dermatol. 2007;24:376-379.

- Simon V, Wolfgan H, Katharina F. Meyerson-Phenomenon hides a nevus flammeus. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2011;9:305-307.

- Shirley MD, Tang H, Gallione CJ, et al. Sturge-Weber syndrome and port-wine stains caused by somatic mutation in GNAQ. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1971-1979.

- Hershkovitz D, Bercovich D, Sprecher E, et al. RASA1 mutations may cause hereditary capillary malformations without arteriovenous malformations. Br J Dermatol. 2008;158:1035-1040.

- Eerola I, Boon LM, Mulliken JB, et al. Capillary malformation-arteriovenous malformation, a new clinical and genetic disorder caused by RASA1 mutations. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;73:1240-1249.

- Henkemeyer M, Rossi DJ, Holmyard DP, et al. Vascular system defects and neuronal apoptosis in mice lacking ras GTPase-activating protein. Nature. 1995;377:695-701.

- Rosen S, Smoller BR. Port-wine stains: a new hypothesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;17:164-166.

- Rydh M, Malm BM, Jernmeck J, et al. Ectatic blood vessels in port-wine stains lack innervation: possible role in pathogenesis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1991;87:419-422.

- Tsuji T, Sawabe M. A new type of telangiectasia following trauma. J Cutan Pathol. 1988;15:22-26.

- Ruocco V, Ruocco E, Brunnetti G, et al. Opportunistic localization of skin lesions on vulnerable areas. Clin Dermatol. 2011;29:483-488.

- Thajudeheen CP, Jyothy K, Pryadarshi A. Treatment of port-wine stains with flash lamp pumped pulsed dye laser on Indian skin: a six year study. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2014;7:32-36.

Port-wine stains (PWSs) are common congenital capillary vascular malformations with an incidence of 3 per 1000 neonates.1 Rarely, acquired PWSs are seen, sometimes appearing following trauma.2-5 Port-wine stains are diagnosed clinically and present as painless, partially or entirely blanchable pink patches that respect the median (midline) plane.6 Although histopathologic examination is not necessary for diagnosis of PWS, typical findings include dilated, ectatic capillaries.7,8 Since it was first reported by Traub9 in 1939, more than 60 cases of acquired PWSs have been reported.10 A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the search terms acquired port-wine stain and port-wine stain and eczema yielded no cases of acquired PWS with associated eczematous changes and only 30 cases of congenital PWS with superimposed eczema.11-18 We report the case of an acquired PWS with superimposed eczema in an 18-year-old man following penetrating abdominal trauma.

Case Report

An otherwise healthy 18-year-old man presented to our dermatology office for evaluation of an eruption that had developed at the site of an abdominal stab wound he sustained 2 to 3 years prior. One year after he was stabbed, the patient developed a nonpruritic, painless red patch located 1 cm anterior to the healed wound on the left abdomen. The patch gradually grew larger to involve the entire left abdomen, extending to the left lower back. The site of the healed stab wound also became raised and pruritic, and the patient noted another pruritic plaque that formed within the larger patch. The patient reported no other skin conditions prior to the current eruption. His medical history was notable for seasonal allergies and asthma, but no childhood eczema.

Physical examination revealed a healthy, well-nourished man with Fitzpatrick skin type IV. A red, purpuric, coalescent patch with slightly arcuate borders extending from the mid abdomen to the left posterior flank was noted. The left lateral aspect of the patch blanched with pressure and respected the median plane. Within the larger patch, a 4-cm×2-cm lichenified, slightly macerated, hyperpigmented plaque was noted at the site of the stab wound (Figure 1). Based on these clinical findings, a presumptive diagnosis of an acquired PWS with superimposed eczema was made.

Punch biopsy specimens were taken from the large vascular patch and the smaller lichenified plaque. Histopathologic examination of the vascular patch showed an increased number of small vessels in the superficial dermis with thickened vessel walls, ectatic lumens, and no vasculopathy, consistent with a vascular malformation or a reactive vascular proliferation (Figure 2). On histopathology, the plaque showed epidermal spongiosis and hyperplasia with serum crust and a papillary dermis containing a mixed inflammatory infiltrate with occasional eosinophils, consistent with an eczematous dermatitis (Figure 3). The histologic findings confirmed the clinical diagnosis.

The pruritic, lichenified plaque improved with application of triamcinolone ointment 0.1% twice daily for 2 weeks. Magnetic resonance imaging to rule out an underlying arteriovenous malformation was recommended, but the patient declined.

Comment

The exact cause of PWS is unknown. There have been a multitude of genomic suspects for congenital lesions, including a somatic activating mutation (ie, a mutation acquired during fetal development) of the GNAQ (guanine nucleotide binding protein [G protein], q polypeptide) gene, which may contribute to abnormal cell proliferation including the regulation of blood vessels, and inactivating mutations in the RASA1 (RAS p21 protein activator [GTPase activating protein] 1) gene, which controls endothelial cell organization.19-22 Later mutations (ie, those occurring after the first trimester) may be more likely to result in isolated PWSs as opposed to syndromic PWSs.19 Whatever the source of genetic misinformation, it is thought that the diminished neuronal control of blood flow and the resulting alterations in dermal structure contribute to the pathogenesis of PWS and its associated histologic features.7,23

The clinical and histopathologic features of acquired PWSs are indistinguishable from those of congenital lesions, indicating that different processes may lead to the same presentation.4 Abnormal innervation and decreased supportive stroma have both been identified as contributing factors in the development of congenital and acquired PWSs.7,23-25 Rosen and Smoller23 found that diminished nerve density affects vascular tone and caliber in PWSs and had hypothesized in a prior report that decreased perivascular Schwann cells may indicate abnormal sympathetic innervation.7 Since then, PWS has been shown to lack both somatic and sensory innervation.24 Tsuji and Sawabe25 indicated that alterations to the perivascular stroma, whether congenital or as a result of trauma, decrease support for vessels, leading to ectasia.

In addition to an acquired PWS, our patient also had associated eczema within the PWS. Eczematous lesions were absent elsewhere, and he did not have a history of childhood eczema. Our review of the literature yielded 8 studies since 1996 that collectively described 30 cases of eczema within PWSs.11-18 Only 2 of these reports described adult patients with concomitant eczema and PWS and none described acquired PWS.13,18

Few studies have addressed the relationship between PWSs and eczema. It is unclear if concomitant PWS and localized eczema are collision dermatoses or if a PWS may predispose the affected skin to eczema.11-13 It has been hypothesized that the increased dermal vasculature in PWSs predisposes the skin to the development of eczema—more specifically, that ectasia may lead to increased inflammation.12,17 The concept of the “immunocompromised district” proposed by Ruocco et al26 is a unifying theory that may underlie the association noted between cases of trauma and later development of a PWS and superimposed eczematous dermatitis, such as in our case. Trauma is noted as one of a number of possible disruptive forces affecting both immunomodulation and neuromodulation within a local area of skin, leading to increased susceptibility of that district to various cutaneous diseases.26

Although our patient’s eczema responded to conservative treatment with a topical steroid, several case series have reported success with laser therapy in the treatment of PWS while preventing recurrence of associated eczematous dermatitis.12,17 Following the cessation of eczema treatment with topical steroid, which causes vasoconstriction, we suggest postponing laser therapy several weeks to allow resolution of vasoconstriction, thus providing enhanced therapeutic targeting with a vascular laser. Of particular relevance to our case, a recent study showed efficacy of the pulsed dye laser in treating PWSs in Fitzpatrick skin types IV and V.27

Conclusion

Although acquired PWS is rare, it can present later in life as an acquired lesion at a site of previous trauma.1-5 Congenital capillary malformations also can be associated with superimposed, localized eczema.11-18 We present a rarely reported case of an acquired PWS with superimposed, localized eczema. As in cases of congenital PWS with concomitant eczema, the associated eczema in our case was responsive to topical corticosteroid therapy. Additionally, pulsed dye laser has been shown to treat PWSs while preventing the recurrence of eczema, and it has been deemed effective for individuals with darker skin types.12,17, 27 Further studies are needed to explore the relationship between PWS and eczema.

Port-wine stains (PWSs) are common congenital capillary vascular malformations with an incidence of 3 per 1000 neonates.1 Rarely, acquired PWSs are seen, sometimes appearing following trauma.2-5 Port-wine stains are diagnosed clinically and present as painless, partially or entirely blanchable pink patches that respect the median (midline) plane.6 Although histopathologic examination is not necessary for diagnosis of PWS, typical findings include dilated, ectatic capillaries.7,8 Since it was first reported by Traub9 in 1939, more than 60 cases of acquired PWSs have been reported.10 A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the search terms acquired port-wine stain and port-wine stain and eczema yielded no cases of acquired PWS with associated eczematous changes and only 30 cases of congenital PWS with superimposed eczema.11-18 We report the case of an acquired PWS with superimposed eczema in an 18-year-old man following penetrating abdominal trauma.

Case Report

An otherwise healthy 18-year-old man presented to our dermatology office for evaluation of an eruption that had developed at the site of an abdominal stab wound he sustained 2 to 3 years prior. One year after he was stabbed, the patient developed a nonpruritic, painless red patch located 1 cm anterior to the healed wound on the left abdomen. The patch gradually grew larger to involve the entire left abdomen, extending to the left lower back. The site of the healed stab wound also became raised and pruritic, and the patient noted another pruritic plaque that formed within the larger patch. The patient reported no other skin conditions prior to the current eruption. His medical history was notable for seasonal allergies and asthma, but no childhood eczema.

Physical examination revealed a healthy, well-nourished man with Fitzpatrick skin type IV. A red, purpuric, coalescent patch with slightly arcuate borders extending from the mid abdomen to the left posterior flank was noted. The left lateral aspect of the patch blanched with pressure and respected the median plane. Within the larger patch, a 4-cm×2-cm lichenified, slightly macerated, hyperpigmented plaque was noted at the site of the stab wound (Figure 1). Based on these clinical findings, a presumptive diagnosis of an acquired PWS with superimposed eczema was made.

Punch biopsy specimens were taken from the large vascular patch and the smaller lichenified plaque. Histopathologic examination of the vascular patch showed an increased number of small vessels in the superficial dermis with thickened vessel walls, ectatic lumens, and no vasculopathy, consistent with a vascular malformation or a reactive vascular proliferation (Figure 2). On histopathology, the plaque showed epidermal spongiosis and hyperplasia with serum crust and a papillary dermis containing a mixed inflammatory infiltrate with occasional eosinophils, consistent with an eczematous dermatitis (Figure 3). The histologic findings confirmed the clinical diagnosis.

The pruritic, lichenified plaque improved with application of triamcinolone ointment 0.1% twice daily for 2 weeks. Magnetic resonance imaging to rule out an underlying arteriovenous malformation was recommended, but the patient declined.

Comment

The exact cause of PWS is unknown. There have been a multitude of genomic suspects for congenital lesions, including a somatic activating mutation (ie, a mutation acquired during fetal development) of the GNAQ (guanine nucleotide binding protein [G protein], q polypeptide) gene, which may contribute to abnormal cell proliferation including the regulation of blood vessels, and inactivating mutations in the RASA1 (RAS p21 protein activator [GTPase activating protein] 1) gene, which controls endothelial cell organization.19-22 Later mutations (ie, those occurring after the first trimester) may be more likely to result in isolated PWSs as opposed to syndromic PWSs.19 Whatever the source of genetic misinformation, it is thought that the diminished neuronal control of blood flow and the resulting alterations in dermal structure contribute to the pathogenesis of PWS and its associated histologic features.7,23

The clinical and histopathologic features of acquired PWSs are indistinguishable from those of congenital lesions, indicating that different processes may lead to the same presentation.4 Abnormal innervation and decreased supportive stroma have both been identified as contributing factors in the development of congenital and acquired PWSs.7,23-25 Rosen and Smoller23 found that diminished nerve density affects vascular tone and caliber in PWSs and had hypothesized in a prior report that decreased perivascular Schwann cells may indicate abnormal sympathetic innervation.7 Since then, PWS has been shown to lack both somatic and sensory innervation.24 Tsuji and Sawabe25 indicated that alterations to the perivascular stroma, whether congenital or as a result of trauma, decrease support for vessels, leading to ectasia.

In addition to an acquired PWS, our patient also had associated eczema within the PWS. Eczematous lesions were absent elsewhere, and he did not have a history of childhood eczema. Our review of the literature yielded 8 studies since 1996 that collectively described 30 cases of eczema within PWSs.11-18 Only 2 of these reports described adult patients with concomitant eczema and PWS and none described acquired PWS.13,18

Few studies have addressed the relationship between PWSs and eczema. It is unclear if concomitant PWS and localized eczema are collision dermatoses or if a PWS may predispose the affected skin to eczema.11-13 It has been hypothesized that the increased dermal vasculature in PWSs predisposes the skin to the development of eczema—more specifically, that ectasia may lead to increased inflammation.12,17 The concept of the “immunocompromised district” proposed by Ruocco et al26 is a unifying theory that may underlie the association noted between cases of trauma and later development of a PWS and superimposed eczematous dermatitis, such as in our case. Trauma is noted as one of a number of possible disruptive forces affecting both immunomodulation and neuromodulation within a local area of skin, leading to increased susceptibility of that district to various cutaneous diseases.26

Although our patient’s eczema responded to conservative treatment with a topical steroid, several case series have reported success with laser therapy in the treatment of PWS while preventing recurrence of associated eczematous dermatitis.12,17 Following the cessation of eczema treatment with topical steroid, which causes vasoconstriction, we suggest postponing laser therapy several weeks to allow resolution of vasoconstriction, thus providing enhanced therapeutic targeting with a vascular laser. Of particular relevance to our case, a recent study showed efficacy of the pulsed dye laser in treating PWSs in Fitzpatrick skin types IV and V.27

Conclusion

Although acquired PWS is rare, it can present later in life as an acquired lesion at a site of previous trauma.1-5 Congenital capillary malformations also can be associated with superimposed, localized eczema.11-18 We present a rarely reported case of an acquired PWS with superimposed, localized eczema. As in cases of congenital PWS with concomitant eczema, the associated eczema in our case was responsive to topical corticosteroid therapy. Additionally, pulsed dye laser has been shown to treat PWSs while preventing the recurrence of eczema, and it has been deemed effective for individuals with darker skin types.12,17, 27 Further studies are needed to explore the relationship between PWS and eczema.

- Jacobs AH, Walton RG. The incidence of birthmarks in the neonate. Pediatrics. 1976;58:218-222.

- Fegeler F. Naevus flammeus im trigeminusgebiet nach trauma im rahmen eines posttraumatisch-vegetativen syndroms. Arch Dermatol Syphilol. 1949;188:416-422.

- Kirkland CR, Mutasim DF. Acquired port-wine stain following repetitive trauma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:462-463.

- Adams BB, Lucky AW. Acquired port-wine stains and antecedent trauma: case report and review of the literature. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:897-899.

- Colver GB, Ryan TJ. Acquired port-wine stain. Arch Dermatol. 1986;122:1415-1416.

- Nigro J, Swerlick RA, Sepp NT, et al. Angiogenesis, vascular malformations and proliferations. In: Arndt KA, LeBoit PE, Robinson JK, Wintroub BU, eds. Cutaneous Medicine and Surgery: An Integrated Program in Dermatology. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders Co; 1996:1492-1521.

- Smoller BR, Rosen S. Port-wine stains. a disease of altered neural modulation of blood vessels? Arch Dermatol. 1986;122:177-179.

- Chang CJ, Yu JS, Nelson JS. Confocal microscopy study of neurovascular distribution in facial port wine stains(capillary malformation). J Formos Med Assoc. 2008;107:559-666.

- Traub EF. Naevus flammeus appearing at the age of twenty three. Arch Dermatol. 1939;39:752.

- Freysz M, Cribier B, Lipsker, D. Fegelers syndrome, acquired port-wine stain or acquired capillary malformation: three cases and a literature review [article in French]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2013;140:341-346.

- Tay YK, Morelli J, Weston WL. Inflammatory nuchal-occipital port-wine stains. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35:811-813.

- Sidwell RU, Syed S, Harper JI. Port-wine stains and eczema. Br J Dermatol. 2001;144:1269-1270.

- Hofer T. Meyerson phenomenon within a nevus flammeus. Dermatology. 2002;205:180-183.

- Raff K, Landthaler M, Hoheleutner U. Port-wine stains with eczema. Phlebologie. 2003;32:15-17.

- Tsuboi H, Miyata T, Katsuoka K. Eczema in a port-wine stain. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2003;28:322-323.

- Rajan N, Natarahan S. Impetiginized eczema arising within a port-wine stain of the arm. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:1009-1010.

- Fonder MA, Mamelak AJ, Kazin RA, et al. Port-wine-stain-associated dermatitis: implications for cutaneous vascular laser therapy. Pediatr Dermatol. 2007;24:376-379.

- Simon V, Wolfgan H, Katharina F. Meyerson-Phenomenon hides a nevus flammeus. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2011;9:305-307.

- Shirley MD, Tang H, Gallione CJ, et al. Sturge-Weber syndrome and port-wine stains caused by somatic mutation in GNAQ. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1971-1979.

- Hershkovitz D, Bercovich D, Sprecher E, et al. RASA1 mutations may cause hereditary capillary malformations without arteriovenous malformations. Br J Dermatol. 2008;158:1035-1040.

- Eerola I, Boon LM, Mulliken JB, et al. Capillary malformation-arteriovenous malformation, a new clinical and genetic disorder caused by RASA1 mutations. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;73:1240-1249.

- Henkemeyer M, Rossi DJ, Holmyard DP, et al. Vascular system defects and neuronal apoptosis in mice lacking ras GTPase-activating protein. Nature. 1995;377:695-701.

- Rosen S, Smoller BR. Port-wine stains: a new hypothesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;17:164-166.

- Rydh M, Malm BM, Jernmeck J, et al. Ectatic blood vessels in port-wine stains lack innervation: possible role in pathogenesis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1991;87:419-422.

- Tsuji T, Sawabe M. A new type of telangiectasia following trauma. J Cutan Pathol. 1988;15:22-26.

- Ruocco V, Ruocco E, Brunnetti G, et al. Opportunistic localization of skin lesions on vulnerable areas. Clin Dermatol. 2011;29:483-488.

- Thajudeheen CP, Jyothy K, Pryadarshi A. Treatment of port-wine stains with flash lamp pumped pulsed dye laser on Indian skin: a six year study. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2014;7:32-36.

- Jacobs AH, Walton RG. The incidence of birthmarks in the neonate. Pediatrics. 1976;58:218-222.

- Fegeler F. Naevus flammeus im trigeminusgebiet nach trauma im rahmen eines posttraumatisch-vegetativen syndroms. Arch Dermatol Syphilol. 1949;188:416-422.

- Kirkland CR, Mutasim DF. Acquired port-wine stain following repetitive trauma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:462-463.

- Adams BB, Lucky AW. Acquired port-wine stains and antecedent trauma: case report and review of the literature. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:897-899.

- Colver GB, Ryan TJ. Acquired port-wine stain. Arch Dermatol. 1986;122:1415-1416.

- Nigro J, Swerlick RA, Sepp NT, et al. Angiogenesis, vascular malformations and proliferations. In: Arndt KA, LeBoit PE, Robinson JK, Wintroub BU, eds. Cutaneous Medicine and Surgery: An Integrated Program in Dermatology. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders Co; 1996:1492-1521.

- Smoller BR, Rosen S. Port-wine stains. a disease of altered neural modulation of blood vessels? Arch Dermatol. 1986;122:177-179.

- Chang CJ, Yu JS, Nelson JS. Confocal microscopy study of neurovascular distribution in facial port wine stains(capillary malformation). J Formos Med Assoc. 2008;107:559-666.

- Traub EF. Naevus flammeus appearing at the age of twenty three. Arch Dermatol. 1939;39:752.

- Freysz M, Cribier B, Lipsker, D. Fegelers syndrome, acquired port-wine stain or acquired capillary malformation: three cases and a literature review [article in French]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2013;140:341-346.

- Tay YK, Morelli J, Weston WL. Inflammatory nuchal-occipital port-wine stains. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35:811-813.

- Sidwell RU, Syed S, Harper JI. Port-wine stains and eczema. Br J Dermatol. 2001;144:1269-1270.

- Hofer T. Meyerson phenomenon within a nevus flammeus. Dermatology. 2002;205:180-183.

- Raff K, Landthaler M, Hoheleutner U. Port-wine stains with eczema. Phlebologie. 2003;32:15-17.

- Tsuboi H, Miyata T, Katsuoka K. Eczema in a port-wine stain. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2003;28:322-323.

- Rajan N, Natarahan S. Impetiginized eczema arising within a port-wine stain of the arm. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:1009-1010.

- Fonder MA, Mamelak AJ, Kazin RA, et al. Port-wine-stain-associated dermatitis: implications for cutaneous vascular laser therapy. Pediatr Dermatol. 2007;24:376-379.

- Simon V, Wolfgan H, Katharina F. Meyerson-Phenomenon hides a nevus flammeus. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2011;9:305-307.

- Shirley MD, Tang H, Gallione CJ, et al. Sturge-Weber syndrome and port-wine stains caused by somatic mutation in GNAQ. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1971-1979.

- Hershkovitz D, Bercovich D, Sprecher E, et al. RASA1 mutations may cause hereditary capillary malformations without arteriovenous malformations. Br J Dermatol. 2008;158:1035-1040.

- Eerola I, Boon LM, Mulliken JB, et al. Capillary malformation-arteriovenous malformation, a new clinical and genetic disorder caused by RASA1 mutations. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;73:1240-1249.

- Henkemeyer M, Rossi DJ, Holmyard DP, et al. Vascular system defects and neuronal apoptosis in mice lacking ras GTPase-activating protein. Nature. 1995;377:695-701.

- Rosen S, Smoller BR. Port-wine stains: a new hypothesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;17:164-166.

- Rydh M, Malm BM, Jernmeck J, et al. Ectatic blood vessels in port-wine stains lack innervation: possible role in pathogenesis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1991;87:419-422.

- Tsuji T, Sawabe M. A new type of telangiectasia following trauma. J Cutan Pathol. 1988;15:22-26.

- Ruocco V, Ruocco E, Brunnetti G, et al. Opportunistic localization of skin lesions on vulnerable areas. Clin Dermatol. 2011;29:483-488.

- Thajudeheen CP, Jyothy K, Pryadarshi A. Treatment of port-wine stains with flash lamp pumped pulsed dye laser on Indian skin: a six year study. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2014;7:32-36.

Practice Points

- Port-wine stains (PWSs) most often are congenital lesions but can present later in life as acquired lesions with the same clinical and histologic findings.

- Magnetic resonance imaging of acquired PWSs should be considered to rule out underlying vascular anomalies (eg, deeper arteriovenous malformations).

- Pulsed dye laser therapy is safe for darker skin types and is the treatment of choice for acquired PWSs.