User login

Update on high-grade vulvar interepithelial neoplasia

Vulvar squamous cell carcinomas (VSCC) comprise approximately 90% of all vulvar malignancies. Unlike cervical SCC, which are predominantly human papilloma virus (HPV) positive, only a minority of VSCC are HPV positive – on the order of 15%-25% of cases. Most cases occur in the setting of lichen sclerosus and are HPV negative.

Lichen sclerosus is a chronic inflammatory dermatitis typically involving the anogenital area, which in some cases can become seriously distorted (e.g. atrophy of the labia minora, clitoral phimosis, and introital stenosis). Although most cases are diagnosed in postmenopausal women, LS can affect women of any age. The true prevalence of lichen sclerosus is unknown. Recent studies have shown a prevalence of 1 in 60; among older women, it can even be as high as 1 in 30. While lichen sclerosus is a pruriginous condition, it is often asymptomatic. It is not considered a premalignant condition. The diagnosis is clinical; however, suspicious lesions (erosions/ulcerations, hyperkeratosis, pigmented areas, ecchymosis, warty or papular lesions), particularly when recalcitrant to adequate first-line therapy, should be biopsied.

VSCC arises from precursor lesions or high-grade vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN). The 2015 International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease nomenclature classifies high-grade VIN into high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HSIL) and differentiated VIN (dVIN). Most patients with high-grade VIN are diagnosed with HSIL or usual type VIN. A preponderance of these lesions (75%-85%) are HPV positive, predominantly HPV 16. Vulvar HSIL (vHSIL) lesions affect younger women. The lesions tend to be multifocal and extensive. On the other hand, dVIN typically affects older women and commonly develops as a solitary lesion. While dVIN accounts for only a small subset of patients with high-grade VIN, these lesions are HPV negative and associated with lichen sclerosus.

Both disease entities, vHSIL and dVIN, are increasing in incidence. There is a higher risk and shortened period of progression to cancer in patients with dVIN compared to HSIL. The cancer risk of vHSIL is relatively low. The 10-year cumulative VSCC risk reported in the literature is 10.3%; 9.7% for vHSIL and 50% for dVIN. Patients with vHSIL could benefit from less aggressive treatment modalities.

Patients present with a constellation of signs such as itching, pain, burning, bleeding, and discharge. Chronic symptoms portend HPV-independent lesions associated with lichen sclerosus while episodic signs are suggestive of HPV-positive lesions.

The recurrence risk of high-grade VIN is 46%-70%. Risk factors for recurrence include age greater than 50, immunosuppression, metasynchronous HSIL, and multifocal lesions. Recurrences occur in up to 50% of women who have undergone surgery. For those who undergo surgical treatment for high-grade VIN, recurrence is more common in the setting of positive margins, underlying lichen sclerosis, persistent HPV infection, and immunosuppression.

Management of high-grade VIN is determined by the lesion characteristics, patient characteristics, and medical expertise. Given the risk of progression of high-grade VIN to cancer and risk of underlying cancer, surgical therapy is typically recommended. The treatment of choice is surgical excision in cases of dVIN. Surgical treatments include CO2 laser ablation, wide local excision, and vulvectomy. Women who undergo surgical treatment for vHSIL have about a 50% chance of the condition recurring 1 year later, irrespective of whether treatment is by surgical excision or laser vaporization.

Since surgery can be associated with disfigurement and sexual dysfunction, alternatives to surgery should be considered in cases of vHSIL. The potential for effect on sexual function should be part of preoperative counseling and treatment. Women treated for VIN often experience increased inhibition of sexual excitement and increased inhibition of orgasm. One study found that in women undergoing vulvar excision for VIN, the impairment was found to be psychological in nature. Overall, the studies of sexual effect from treatment of VIN have found that women do not return to their pretreatment sexual function. However, the optimal management of vHSIL has not been determined. Nonsurgical options include topical therapies (imiquimod, 5-fluorouracil, cidofovir, and interferon) and nonpharmacologic treatments, such as photodynamic therapy.

Imiquimod, a topical immune modulator, is the most studied pharmacologic treatment of vHSIL. The drug induces secretion of cytokines, creating an immune response that clears the HPV infection. Imiquimod is safe and well tolerated. The clinical response rate varies between 35% and 81%. A recent study demonstrated the efficacy of imiquimod and the treatment was found to be noninferior to surgery. Adverse events differed, with local pain following surgical treatment and local pruritus and erythema associated with imiquimod use. Some patients did not respond to imiquimod; it was thought by the authors of the study that specific immunological factors affect the clinical response.

In conclusion, high-grade VIN is a heterogeneous disease made up of two distinct disease entities with rising incidence. In contrast to dVIN, the cancer risk is low for patients with vHSIL. Treatment should be driven by the clinical characteristics of the vulvar lesions, patients’ preferences, sexual activity, and compliance. Future directions include risk stratification of patients with vHSIL who are most likely to benefit from topical treatments, thus reducing overtreatment. Molecular biomarkers that could identify dVIN at an early stage are needed.

Dr. Jackson-Moore is associate professor in gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Tucker is assistant professor of gynecologic oncology at the university.

References

Cendejas BR et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015 Mar;212(3):291-7.

Lebreton M et al. J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod. 2020 Nov;49(9):101801.

Thuijs NB et al. Int J Cancer. 2021 Jan 1;148(1):90-8. doi: 10.1002/ijc.33198. .

Trutnovsky G et al. Lancet. 2022 May 7;399(10337):1790-8. Erratum in: Lancet. 2022 Oct 8;400(10359):1194.

Vulvar squamous cell carcinomas (VSCC) comprise approximately 90% of all vulvar malignancies. Unlike cervical SCC, which are predominantly human papilloma virus (HPV) positive, only a minority of VSCC are HPV positive – on the order of 15%-25% of cases. Most cases occur in the setting of lichen sclerosus and are HPV negative.

Lichen sclerosus is a chronic inflammatory dermatitis typically involving the anogenital area, which in some cases can become seriously distorted (e.g. atrophy of the labia minora, clitoral phimosis, and introital stenosis). Although most cases are diagnosed in postmenopausal women, LS can affect women of any age. The true prevalence of lichen sclerosus is unknown. Recent studies have shown a prevalence of 1 in 60; among older women, it can even be as high as 1 in 30. While lichen sclerosus is a pruriginous condition, it is often asymptomatic. It is not considered a premalignant condition. The diagnosis is clinical; however, suspicious lesions (erosions/ulcerations, hyperkeratosis, pigmented areas, ecchymosis, warty or papular lesions), particularly when recalcitrant to adequate first-line therapy, should be biopsied.

VSCC arises from precursor lesions or high-grade vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN). The 2015 International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease nomenclature classifies high-grade VIN into high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HSIL) and differentiated VIN (dVIN). Most patients with high-grade VIN are diagnosed with HSIL or usual type VIN. A preponderance of these lesions (75%-85%) are HPV positive, predominantly HPV 16. Vulvar HSIL (vHSIL) lesions affect younger women. The lesions tend to be multifocal and extensive. On the other hand, dVIN typically affects older women and commonly develops as a solitary lesion. While dVIN accounts for only a small subset of patients with high-grade VIN, these lesions are HPV negative and associated with lichen sclerosus.

Both disease entities, vHSIL and dVIN, are increasing in incidence. There is a higher risk and shortened period of progression to cancer in patients with dVIN compared to HSIL. The cancer risk of vHSIL is relatively low. The 10-year cumulative VSCC risk reported in the literature is 10.3%; 9.7% for vHSIL and 50% for dVIN. Patients with vHSIL could benefit from less aggressive treatment modalities.

Patients present with a constellation of signs such as itching, pain, burning, bleeding, and discharge. Chronic symptoms portend HPV-independent lesions associated with lichen sclerosus while episodic signs are suggestive of HPV-positive lesions.

The recurrence risk of high-grade VIN is 46%-70%. Risk factors for recurrence include age greater than 50, immunosuppression, metasynchronous HSIL, and multifocal lesions. Recurrences occur in up to 50% of women who have undergone surgery. For those who undergo surgical treatment for high-grade VIN, recurrence is more common in the setting of positive margins, underlying lichen sclerosis, persistent HPV infection, and immunosuppression.

Management of high-grade VIN is determined by the lesion characteristics, patient characteristics, and medical expertise. Given the risk of progression of high-grade VIN to cancer and risk of underlying cancer, surgical therapy is typically recommended. The treatment of choice is surgical excision in cases of dVIN. Surgical treatments include CO2 laser ablation, wide local excision, and vulvectomy. Women who undergo surgical treatment for vHSIL have about a 50% chance of the condition recurring 1 year later, irrespective of whether treatment is by surgical excision or laser vaporization.

Since surgery can be associated with disfigurement and sexual dysfunction, alternatives to surgery should be considered in cases of vHSIL. The potential for effect on sexual function should be part of preoperative counseling and treatment. Women treated for VIN often experience increased inhibition of sexual excitement and increased inhibition of orgasm. One study found that in women undergoing vulvar excision for VIN, the impairment was found to be psychological in nature. Overall, the studies of sexual effect from treatment of VIN have found that women do not return to their pretreatment sexual function. However, the optimal management of vHSIL has not been determined. Nonsurgical options include topical therapies (imiquimod, 5-fluorouracil, cidofovir, and interferon) and nonpharmacologic treatments, such as photodynamic therapy.

Imiquimod, a topical immune modulator, is the most studied pharmacologic treatment of vHSIL. The drug induces secretion of cytokines, creating an immune response that clears the HPV infection. Imiquimod is safe and well tolerated. The clinical response rate varies between 35% and 81%. A recent study demonstrated the efficacy of imiquimod and the treatment was found to be noninferior to surgery. Adverse events differed, with local pain following surgical treatment and local pruritus and erythema associated with imiquimod use. Some patients did not respond to imiquimod; it was thought by the authors of the study that specific immunological factors affect the clinical response.

In conclusion, high-grade VIN is a heterogeneous disease made up of two distinct disease entities with rising incidence. In contrast to dVIN, the cancer risk is low for patients with vHSIL. Treatment should be driven by the clinical characteristics of the vulvar lesions, patients’ preferences, sexual activity, and compliance. Future directions include risk stratification of patients with vHSIL who are most likely to benefit from topical treatments, thus reducing overtreatment. Molecular biomarkers that could identify dVIN at an early stage are needed.

Dr. Jackson-Moore is associate professor in gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Tucker is assistant professor of gynecologic oncology at the university.

References

Cendejas BR et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015 Mar;212(3):291-7.

Lebreton M et al. J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod. 2020 Nov;49(9):101801.

Thuijs NB et al. Int J Cancer. 2021 Jan 1;148(1):90-8. doi: 10.1002/ijc.33198. .

Trutnovsky G et al. Lancet. 2022 May 7;399(10337):1790-8. Erratum in: Lancet. 2022 Oct 8;400(10359):1194.

Vulvar squamous cell carcinomas (VSCC) comprise approximately 90% of all vulvar malignancies. Unlike cervical SCC, which are predominantly human papilloma virus (HPV) positive, only a minority of VSCC are HPV positive – on the order of 15%-25% of cases. Most cases occur in the setting of lichen sclerosus and are HPV negative.

Lichen sclerosus is a chronic inflammatory dermatitis typically involving the anogenital area, which in some cases can become seriously distorted (e.g. atrophy of the labia minora, clitoral phimosis, and introital stenosis). Although most cases are diagnosed in postmenopausal women, LS can affect women of any age. The true prevalence of lichen sclerosus is unknown. Recent studies have shown a prevalence of 1 in 60; among older women, it can even be as high as 1 in 30. While lichen sclerosus is a pruriginous condition, it is often asymptomatic. It is not considered a premalignant condition. The diagnosis is clinical; however, suspicious lesions (erosions/ulcerations, hyperkeratosis, pigmented areas, ecchymosis, warty or papular lesions), particularly when recalcitrant to adequate first-line therapy, should be biopsied.

VSCC arises from precursor lesions or high-grade vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN). The 2015 International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease nomenclature classifies high-grade VIN into high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HSIL) and differentiated VIN (dVIN). Most patients with high-grade VIN are diagnosed with HSIL or usual type VIN. A preponderance of these lesions (75%-85%) are HPV positive, predominantly HPV 16. Vulvar HSIL (vHSIL) lesions affect younger women. The lesions tend to be multifocal and extensive. On the other hand, dVIN typically affects older women and commonly develops as a solitary lesion. While dVIN accounts for only a small subset of patients with high-grade VIN, these lesions are HPV negative and associated with lichen sclerosus.

Both disease entities, vHSIL and dVIN, are increasing in incidence. There is a higher risk and shortened period of progression to cancer in patients with dVIN compared to HSIL. The cancer risk of vHSIL is relatively low. The 10-year cumulative VSCC risk reported in the literature is 10.3%; 9.7% for vHSIL and 50% for dVIN. Patients with vHSIL could benefit from less aggressive treatment modalities.

Patients present with a constellation of signs such as itching, pain, burning, bleeding, and discharge. Chronic symptoms portend HPV-independent lesions associated with lichen sclerosus while episodic signs are suggestive of HPV-positive lesions.

The recurrence risk of high-grade VIN is 46%-70%. Risk factors for recurrence include age greater than 50, immunosuppression, metasynchronous HSIL, and multifocal lesions. Recurrences occur in up to 50% of women who have undergone surgery. For those who undergo surgical treatment for high-grade VIN, recurrence is more common in the setting of positive margins, underlying lichen sclerosis, persistent HPV infection, and immunosuppression.

Management of high-grade VIN is determined by the lesion characteristics, patient characteristics, and medical expertise. Given the risk of progression of high-grade VIN to cancer and risk of underlying cancer, surgical therapy is typically recommended. The treatment of choice is surgical excision in cases of dVIN. Surgical treatments include CO2 laser ablation, wide local excision, and vulvectomy. Women who undergo surgical treatment for vHSIL have about a 50% chance of the condition recurring 1 year later, irrespective of whether treatment is by surgical excision or laser vaporization.

Since surgery can be associated with disfigurement and sexual dysfunction, alternatives to surgery should be considered in cases of vHSIL. The potential for effect on sexual function should be part of preoperative counseling and treatment. Women treated for VIN often experience increased inhibition of sexual excitement and increased inhibition of orgasm. One study found that in women undergoing vulvar excision for VIN, the impairment was found to be psychological in nature. Overall, the studies of sexual effect from treatment of VIN have found that women do not return to their pretreatment sexual function. However, the optimal management of vHSIL has not been determined. Nonsurgical options include topical therapies (imiquimod, 5-fluorouracil, cidofovir, and interferon) and nonpharmacologic treatments, such as photodynamic therapy.

Imiquimod, a topical immune modulator, is the most studied pharmacologic treatment of vHSIL. The drug induces secretion of cytokines, creating an immune response that clears the HPV infection. Imiquimod is safe and well tolerated. The clinical response rate varies between 35% and 81%. A recent study demonstrated the efficacy of imiquimod and the treatment was found to be noninferior to surgery. Adverse events differed, with local pain following surgical treatment and local pruritus and erythema associated with imiquimod use. Some patients did not respond to imiquimod; it was thought by the authors of the study that specific immunological factors affect the clinical response.

In conclusion, high-grade VIN is a heterogeneous disease made up of two distinct disease entities with rising incidence. In contrast to dVIN, the cancer risk is low for patients with vHSIL. Treatment should be driven by the clinical characteristics of the vulvar lesions, patients’ preferences, sexual activity, and compliance. Future directions include risk stratification of patients with vHSIL who are most likely to benefit from topical treatments, thus reducing overtreatment. Molecular biomarkers that could identify dVIN at an early stage are needed.

Dr. Jackson-Moore is associate professor in gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Tucker is assistant professor of gynecologic oncology at the university.

References

Cendejas BR et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015 Mar;212(3):291-7.

Lebreton M et al. J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod. 2020 Nov;49(9):101801.

Thuijs NB et al. Int J Cancer. 2021 Jan 1;148(1):90-8. doi: 10.1002/ijc.33198. .

Trutnovsky G et al. Lancet. 2022 May 7;399(10337):1790-8. Erratum in: Lancet. 2022 Oct 8;400(10359):1194.

Approach to the asymptomatic adnexal mass: When to operate, refer, or observe

Adnexal masses are common findings in women. While the decision to operate on symptomatic adnexal masses is straightforward, the decision-making process for asymptomatic masses is more complicated. Here we address how to approach an asymptomatic adnexal mass, including how to decide when to operate, when to refer, or how to monitor.

It is important to minimize the number of surgeries for benign, asymptomatic adnexal masses because complications are reported in 2%-15% of surgeries for adnexal masses and these can range from minimal to devastating.1 In addition, unnecessary surgery is associated with a burden of cost to the health care system. Therefore, there is a paradigm shift in the management of asymptomatic adnexal masses trending toward surveillance of any masses that are likely to be benign. What becomes critical in this approach is the ability to accurately classify these masses preoperatively.

Determining the malignant potential of a mass

Guidance is provided by the ACOG Practice Bulletin Number 174, which was published in 2016: “Evaluation and Management of Adnexal Masses.”2 These guidelines remind clinicians that:

- Most adnexal masses are benign, even in postmenopausal patients.

- The recommended imaging modality is quality transvaginal ultrasonography with an ultrasonographer accredited through the American Registry of Diagnostic Medical Sonographers.

- Simple cysts up to 10 cm can be monitored using repeat imaging every 6 months without surgical intervention, even in postmenopausal patients. In prospective studies, no cases of malignancy were diagnosed over 6 years of surveillance and most resolved. Those that persist are likely to be serous cystadenomas.

- Many benign lesions such as endometriomas and cystic teratomas have characteristic radiologic features. Surgery for these lesions is warranted for large size, symptoms, or growth in size.

- Ultrasound characteristics of malignant masses include:

1. Cyst size greater than 10 cm

2. Papillary or solid components

3. Septations

4. Internal blood flow on color Doppler.

An alternative approach that has been proposed is an ultrasound scoring system devised by International Ovarian Tumor Analysis Group. The scoring system uses 10 ultrasound findings that are characteristic of malignant and benign and is designed to characterize masses as either benign or malignant.3 This approach is able to correctly classify 77% of masses. The remaining masses with features that do not fit the “simple rules” are considered potentially malignant and should be referred to an oncology specialist for further decision making.

Decision to operate

After referral to gynecologic oncologists, surgery is not always inevitable, particularly for women with indeterminate masses. The gynecologic oncologist uses a decision-making process that factors in the underlying surgical risks for that patient with the likelihood of malignancy based on the features of the mass. The threshold to operate is higher in women with underlying major comorbidities, such as morbid obesity, complex prior surgical history, or cardiopulmonary disease. Healthier surgical candidates are more likely to be considered for a surgery, even if the suspicion for malignancy is lower. However, low surgical risk does not equate to no surgical risk. Therefore, even in apparently “good” surgical candidates, the suspicion for underlying malignancy needs to be reasonably high in order to justify the cost and risk of surgery in an asymptomatic patient. Sometimes it is patient anxiety and a desire to avoid repeated surveillance that prompts a decision to operate.

How to monitor

The role of surveillance and monitoring is to establish a natural history of the lesion or to allow it to reveal itself to be stable or regressive. Surveillance with serial sonography has shown that most asymptomatic adnexal masses with low risk features will resolve over time. Lack of resolution in the setting of stable findings is not a worrisome feature and is not suggestive of malignancy. The mere persistence of an otherwise benign-appearing lesion is not a reason to intervene with surgery.

Unfortunately, there is no clear guidance on the surveillance intervals. Some experts recommend an initial repeat scan in 3 months. If at that point the morphologic features and size are stable or decreasing, ultrasounds can be repeated at annual intervals for 5 years. In one study, masses that became malignant demonstrated growth by 7 months. Other experts recommend limiting the period of surveillance of cystic lesions to 1 year and lesions with solid components to 2 years.

Conclusions

Many asymptomatic adnexal masses discovered on imaging can be monitored with serial sonography. Lesions with more worrisome morphology that’s suggestive of malignancy should prompt referral to a gynecologic oncologist. Surgery on benign masses can be avoided. Outcome data is needed to advise the optimal timing intervals and the limit of follow-up serial ultrasonography. A caveat of this watch-and-see approach is having to allay the patient’s fears of the malignant potential of the mass. This requires conversations with the patient informing them that the stability of the mass will be shown over time and that surgery can be safely avoided.

References

1. Glanc P et al. J Ultrasound Med. 2017;36:849-63.

2. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Committee on Practice Bulletins – Gynecology. Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Nov;128(5):e210-26.

3. Timmerman D et al. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2008 Jun;31(6):681-90.

Dr. Jackson-Moore is an associate professor in gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Rossi is an assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at UNC. They reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Adnexal masses are common findings in women. While the decision to operate on symptomatic adnexal masses is straightforward, the decision-making process for asymptomatic masses is more complicated. Here we address how to approach an asymptomatic adnexal mass, including how to decide when to operate, when to refer, or how to monitor.

It is important to minimize the number of surgeries for benign, asymptomatic adnexal masses because complications are reported in 2%-15% of surgeries for adnexal masses and these can range from minimal to devastating.1 In addition, unnecessary surgery is associated with a burden of cost to the health care system. Therefore, there is a paradigm shift in the management of asymptomatic adnexal masses trending toward surveillance of any masses that are likely to be benign. What becomes critical in this approach is the ability to accurately classify these masses preoperatively.

Determining the malignant potential of a mass

Guidance is provided by the ACOG Practice Bulletin Number 174, which was published in 2016: “Evaluation and Management of Adnexal Masses.”2 These guidelines remind clinicians that:

- Most adnexal masses are benign, even in postmenopausal patients.

- The recommended imaging modality is quality transvaginal ultrasonography with an ultrasonographer accredited through the American Registry of Diagnostic Medical Sonographers.

- Simple cysts up to 10 cm can be monitored using repeat imaging every 6 months without surgical intervention, even in postmenopausal patients. In prospective studies, no cases of malignancy were diagnosed over 6 years of surveillance and most resolved. Those that persist are likely to be serous cystadenomas.

- Many benign lesions such as endometriomas and cystic teratomas have characteristic radiologic features. Surgery for these lesions is warranted for large size, symptoms, or growth in size.

- Ultrasound characteristics of malignant masses include:

1. Cyst size greater than 10 cm

2. Papillary or solid components

3. Septations

4. Internal blood flow on color Doppler.

An alternative approach that has been proposed is an ultrasound scoring system devised by International Ovarian Tumor Analysis Group. The scoring system uses 10 ultrasound findings that are characteristic of malignant and benign and is designed to characterize masses as either benign or malignant.3 This approach is able to correctly classify 77% of masses. The remaining masses with features that do not fit the “simple rules” are considered potentially malignant and should be referred to an oncology specialist for further decision making.

Decision to operate

After referral to gynecologic oncologists, surgery is not always inevitable, particularly for women with indeterminate masses. The gynecologic oncologist uses a decision-making process that factors in the underlying surgical risks for that patient with the likelihood of malignancy based on the features of the mass. The threshold to operate is higher in women with underlying major comorbidities, such as morbid obesity, complex prior surgical history, or cardiopulmonary disease. Healthier surgical candidates are more likely to be considered for a surgery, even if the suspicion for malignancy is lower. However, low surgical risk does not equate to no surgical risk. Therefore, even in apparently “good” surgical candidates, the suspicion for underlying malignancy needs to be reasonably high in order to justify the cost and risk of surgery in an asymptomatic patient. Sometimes it is patient anxiety and a desire to avoid repeated surveillance that prompts a decision to operate.

How to monitor

The role of surveillance and monitoring is to establish a natural history of the lesion or to allow it to reveal itself to be stable or regressive. Surveillance with serial sonography has shown that most asymptomatic adnexal masses with low risk features will resolve over time. Lack of resolution in the setting of stable findings is not a worrisome feature and is not suggestive of malignancy. The mere persistence of an otherwise benign-appearing lesion is not a reason to intervene with surgery.

Unfortunately, there is no clear guidance on the surveillance intervals. Some experts recommend an initial repeat scan in 3 months. If at that point the morphologic features and size are stable or decreasing, ultrasounds can be repeated at annual intervals for 5 years. In one study, masses that became malignant demonstrated growth by 7 months. Other experts recommend limiting the period of surveillance of cystic lesions to 1 year and lesions with solid components to 2 years.

Conclusions

Many asymptomatic adnexal masses discovered on imaging can be monitored with serial sonography. Lesions with more worrisome morphology that’s suggestive of malignancy should prompt referral to a gynecologic oncologist. Surgery on benign masses can be avoided. Outcome data is needed to advise the optimal timing intervals and the limit of follow-up serial ultrasonography. A caveat of this watch-and-see approach is having to allay the patient’s fears of the malignant potential of the mass. This requires conversations with the patient informing them that the stability of the mass will be shown over time and that surgery can be safely avoided.

References

1. Glanc P et al. J Ultrasound Med. 2017;36:849-63.

2. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Committee on Practice Bulletins – Gynecology. Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Nov;128(5):e210-26.

3. Timmerman D et al. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2008 Jun;31(6):681-90.

Dr. Jackson-Moore is an associate professor in gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Rossi is an assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at UNC. They reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Adnexal masses are common findings in women. While the decision to operate on symptomatic adnexal masses is straightforward, the decision-making process for asymptomatic masses is more complicated. Here we address how to approach an asymptomatic adnexal mass, including how to decide when to operate, when to refer, or how to monitor.

It is important to minimize the number of surgeries for benign, asymptomatic adnexal masses because complications are reported in 2%-15% of surgeries for adnexal masses and these can range from minimal to devastating.1 In addition, unnecessary surgery is associated with a burden of cost to the health care system. Therefore, there is a paradigm shift in the management of asymptomatic adnexal masses trending toward surveillance of any masses that are likely to be benign. What becomes critical in this approach is the ability to accurately classify these masses preoperatively.

Determining the malignant potential of a mass

Guidance is provided by the ACOG Practice Bulletin Number 174, which was published in 2016: “Evaluation and Management of Adnexal Masses.”2 These guidelines remind clinicians that:

- Most adnexal masses are benign, even in postmenopausal patients.

- The recommended imaging modality is quality transvaginal ultrasonography with an ultrasonographer accredited through the American Registry of Diagnostic Medical Sonographers.

- Simple cysts up to 10 cm can be monitored using repeat imaging every 6 months without surgical intervention, even in postmenopausal patients. In prospective studies, no cases of malignancy were diagnosed over 6 years of surveillance and most resolved. Those that persist are likely to be serous cystadenomas.

- Many benign lesions such as endometriomas and cystic teratomas have characteristic radiologic features. Surgery for these lesions is warranted for large size, symptoms, or growth in size.

- Ultrasound characteristics of malignant masses include:

1. Cyst size greater than 10 cm

2. Papillary or solid components

3. Septations

4. Internal blood flow on color Doppler.

An alternative approach that has been proposed is an ultrasound scoring system devised by International Ovarian Tumor Analysis Group. The scoring system uses 10 ultrasound findings that are characteristic of malignant and benign and is designed to characterize masses as either benign or malignant.3 This approach is able to correctly classify 77% of masses. The remaining masses with features that do not fit the “simple rules” are considered potentially malignant and should be referred to an oncology specialist for further decision making.

Decision to operate

After referral to gynecologic oncologists, surgery is not always inevitable, particularly for women with indeterminate masses. The gynecologic oncologist uses a decision-making process that factors in the underlying surgical risks for that patient with the likelihood of malignancy based on the features of the mass. The threshold to operate is higher in women with underlying major comorbidities, such as morbid obesity, complex prior surgical history, or cardiopulmonary disease. Healthier surgical candidates are more likely to be considered for a surgery, even if the suspicion for malignancy is lower. However, low surgical risk does not equate to no surgical risk. Therefore, even in apparently “good” surgical candidates, the suspicion for underlying malignancy needs to be reasonably high in order to justify the cost and risk of surgery in an asymptomatic patient. Sometimes it is patient anxiety and a desire to avoid repeated surveillance that prompts a decision to operate.

How to monitor

The role of surveillance and monitoring is to establish a natural history of the lesion or to allow it to reveal itself to be stable or regressive. Surveillance with serial sonography has shown that most asymptomatic adnexal masses with low risk features will resolve over time. Lack of resolution in the setting of stable findings is not a worrisome feature and is not suggestive of malignancy. The mere persistence of an otherwise benign-appearing lesion is not a reason to intervene with surgery.

Unfortunately, there is no clear guidance on the surveillance intervals. Some experts recommend an initial repeat scan in 3 months. If at that point the morphologic features and size are stable or decreasing, ultrasounds can be repeated at annual intervals for 5 years. In one study, masses that became malignant demonstrated growth by 7 months. Other experts recommend limiting the period of surveillance of cystic lesions to 1 year and lesions with solid components to 2 years.

Conclusions

Many asymptomatic adnexal masses discovered on imaging can be monitored with serial sonography. Lesions with more worrisome morphology that’s suggestive of malignancy should prompt referral to a gynecologic oncologist. Surgery on benign masses can be avoided. Outcome data is needed to advise the optimal timing intervals and the limit of follow-up serial ultrasonography. A caveat of this watch-and-see approach is having to allay the patient’s fears of the malignant potential of the mass. This requires conversations with the patient informing them that the stability of the mass will be shown over time and that surgery can be safely avoided.

References

1. Glanc P et al. J Ultrasound Med. 2017;36:849-63.

2. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Committee on Practice Bulletins – Gynecology. Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Nov;128(5):e210-26.

3. Timmerman D et al. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2008 Jun;31(6):681-90.

Dr. Jackson-Moore is an associate professor in gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Rossi is an assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at UNC. They reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Preventing surgical site infections in hysterectomy

Surgical site infections are a major source of patient morbidity. They are also an important quality metric for surgeons and hospital systems, and are increasingly being linked to reimbursement.

They occur in approximately 2% of the 600,000 women undergoing hysterectomy in the United States each year. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention defines surgical site infection (SSI) as an infection that occurs within 30 days of a procedure in the part of the body where the surgery took place. Most SSIs are superficial incisional, but they also include deep incisional or organ or space infections.

Classification

The incidence of SSI varies according to the classification of the wound, as defined by the National Academy of Sciences.1 Most hysterectomies are classified as clean-contaminated wounds because they involve entry into the mucosa of the genitourinary tract. However, hysterectomy with contamination of bowel flora, or in the setting of acute infection (such as suppurative pelvic inflammatory disease) are considered a contaminated wound class, and are associated with even higher rates of SSI.

Risk factors

The risk factors associated with SSI are both modifiable and unmodifiable. Broadly speaking, they include increased risk to endogenous flora (e.g., wound classification), increased exposure to exogenous flora (e.g., inadequate protection of a wound from external pathogens), and impairment of the body’s immune mechanisms to prevent and overcome infection (e.g., hypothermia and hypoglycemia).

Unmodifiable risk factors include increasing age, a history of radiation exposure, vascular disease, and a history of prior SSIs. Modifiable risk factors include obesity, tobacco use, immunosuppressive medications, hypoalbuminemia, route of hysterectomy, hair removal, preoperative infections (such as bacterial vaginosis), surgical scrub, skin and vaginal preparation, antimicrobial prophylaxis (inappropriate choice or timing, inadequate dosing or redosing), operative time, blood transfusion, surgical skill, and operating room characteristics (ventilation, increased OR traffic, and sterilization of surgical equipment).

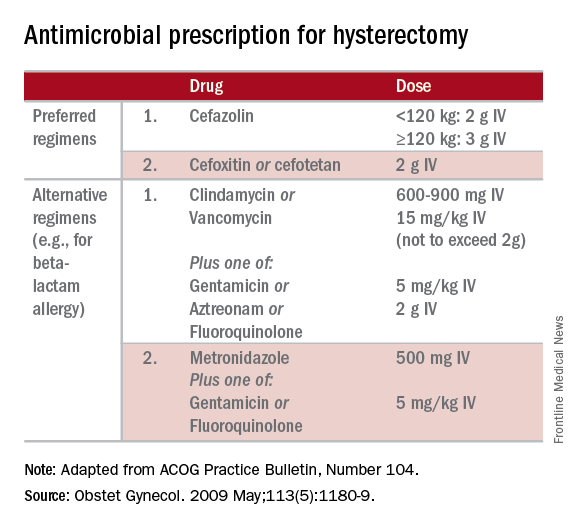

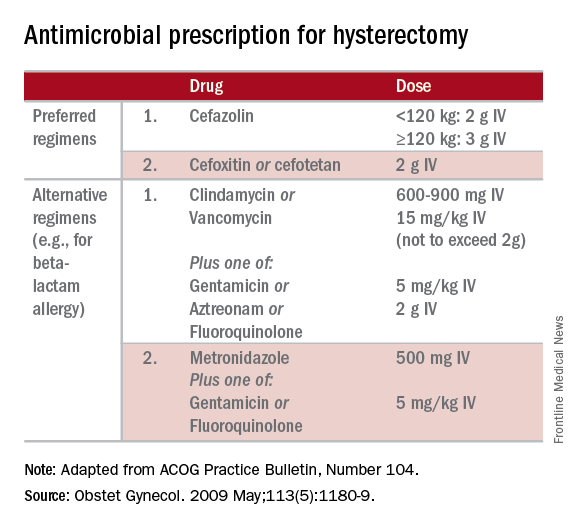

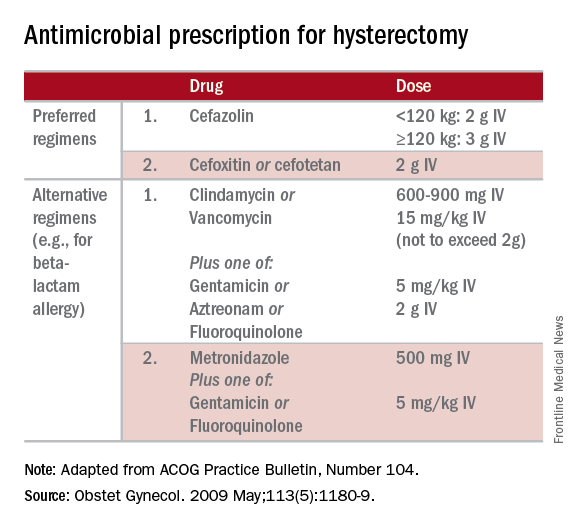

Antimicrobial prophylaxis

The CDC and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) have provided clear guidelines regarding methods to reduce SSI in hysterectomy.3,4 There is strong evidence for using antimicrobial prophylaxis for hysterectomy.

It is important that physicians confirm the validity of beta-lactam allergies with patients because there are higher rates of SSI with the use of non–beta-lactam regimens, even those endorsed by the CDC and ACOG.5

Antibiotics should be administered within 1 hour of skin incision, and ideally within 30 minutes. They should be discontinued within 24 hours. Dosing should be adjusted to weight, and antimicrobials should be redosed for long procedures (at intervals of two half-lives), and for increased blood loss.

Skin preparation

Hair removal should be avoided unless necessary for technical reasons. If it is required, it should be performed outside of the operative space using clippers, not razors. For patients colonized with methicillin-resistant S. aureus, there is supporting evidence for pretreatment with mupirocin ointment to the nares, and chlorhexidine showers for 5-10 days. Patients who have bacterial vaginosis should be treated before surgery to decrease the rate of vaginal cuff SSI.

If there is a planned or potential gastrointestinal procedure as part of the hysterectomy, the surgeon should consider using an impervious plastic wound protector in place of, or in addition to, other retractors. Preoperative oral antimicrobials with mechanical bowel preparation have been associated with decreased SSIs; however, this benefit is not observed with mechanical bowel preparation alone.

Wound closure

Surgical technique and wound closure techniques also impact SSI. Minimally invasive and vaginal hysterectomy routes are preferred, as these are associated with the lowest rates of SSI. Antimicrobial-impregnated suture materials appear to be unnecessary. Surgeons should ensure that there is delicate handling of tissues and closure of dead spaces. If the subcutaneous fat space depth measures more than 2.5 cm, it should be reapproximated with a rapidly-absorbing suture material.

Use of electrosurgery versus a scalpel when creating the incision does not appear to influence infection rates, nor does use of staples versus subcuticular suture during closure.7

Using a dilute iodine lavage in the subcutaneous space, opening a sterile closing tray, and having surgeons change gloves prior to skin closure should be considered. The CDC recommends keeping the skin dressing in place for 24 hours postoperatively.

Other strategies

Hyperglycemia is associated with impaired neutrophil response, and therefore blood glucose should be controlled before surgery (hemoglobin A1c levels of less than 7% preoperatively) and immediately postoperatively (less than 180 mg/dL within 18-24 hours after the end of anesthesia).

It is also important to minimize perioperative hypothermia (less than 35.5° F), as this also impairs the body’s immune response. Keeping operative room ambient temperatures higher, minimizing incision size, warming CO2 gas in minimally invasive procedures, warming fluids, and using extrinsic body warmers can help achieve this.

Excessive blood loss should be minimized because blood transfusion is associated with impaired macrophage function and increased risk for SSI.

In addition to teamwide (including nonsurgeon) strict adherence to hand hygiene, OR personnel should avoid unnecessary operating room traffic. Hospital officials should ensure that the facility’s ventilator systems are well maintained and that there is care and maintenance of air handlers.

Many strategies can be employed perioperatively to decrease SSI rates for hysterectomy. We advocate for a protocol-based approach (known as “bundling” strategies) to achieve consistency of practice and to maximize surgeon and institutional improvements in SSI rates. This is similar to the approach outlined in a recent consensus statement from the Council on Patient Safety in Women’s Health Care.8

A comprehensive multidisciplinary approach throughout the perioperative period is necessary. It is imperative that good communication exist with patients regarding SSIs after hysterectomy and how patients, surgeons, and hospitals can together minimize the risks of SSIs.

References

1. Altemeier WA. “Manual on Control of Infection in Surgical Patients” (Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 1984).

2. Rev Infect Dis. 1991 Sep-Oct;13(Suppl 10):S821-41.

3. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2014 Jun;35(6):605-27.

4. Obstet Gynecol. 2009 May;113(5):1180-9.

5. Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Feb;127(2):321-9.

6. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005 Feb;192(2):422-5.

7. J Gastrointest Surg. 2016 Dec;20(12):2083-92.

8. Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Dec 7. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001751.

Dr. Rossi is an assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Jackson-Moore is an associate professor in gynecologic oncology at UNC. They reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Surgical site infections are a major source of patient morbidity. They are also an important quality metric for surgeons and hospital systems, and are increasingly being linked to reimbursement.

They occur in approximately 2% of the 600,000 women undergoing hysterectomy in the United States each year. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention defines surgical site infection (SSI) as an infection that occurs within 30 days of a procedure in the part of the body where the surgery took place. Most SSIs are superficial incisional, but they also include deep incisional or organ or space infections.

Classification

The incidence of SSI varies according to the classification of the wound, as defined by the National Academy of Sciences.1 Most hysterectomies are classified as clean-contaminated wounds because they involve entry into the mucosa of the genitourinary tract. However, hysterectomy with contamination of bowel flora, or in the setting of acute infection (such as suppurative pelvic inflammatory disease) are considered a contaminated wound class, and are associated with even higher rates of SSI.

Risk factors

The risk factors associated with SSI are both modifiable and unmodifiable. Broadly speaking, they include increased risk to endogenous flora (e.g., wound classification), increased exposure to exogenous flora (e.g., inadequate protection of a wound from external pathogens), and impairment of the body’s immune mechanisms to prevent and overcome infection (e.g., hypothermia and hypoglycemia).

Unmodifiable risk factors include increasing age, a history of radiation exposure, vascular disease, and a history of prior SSIs. Modifiable risk factors include obesity, tobacco use, immunosuppressive medications, hypoalbuminemia, route of hysterectomy, hair removal, preoperative infections (such as bacterial vaginosis), surgical scrub, skin and vaginal preparation, antimicrobial prophylaxis (inappropriate choice or timing, inadequate dosing or redosing), operative time, blood transfusion, surgical skill, and operating room characteristics (ventilation, increased OR traffic, and sterilization of surgical equipment).

Antimicrobial prophylaxis

The CDC and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) have provided clear guidelines regarding methods to reduce SSI in hysterectomy.3,4 There is strong evidence for using antimicrobial prophylaxis for hysterectomy.

It is important that physicians confirm the validity of beta-lactam allergies with patients because there are higher rates of SSI with the use of non–beta-lactam regimens, even those endorsed by the CDC and ACOG.5

Antibiotics should be administered within 1 hour of skin incision, and ideally within 30 minutes. They should be discontinued within 24 hours. Dosing should be adjusted to weight, and antimicrobials should be redosed for long procedures (at intervals of two half-lives), and for increased blood loss.

Skin preparation

Hair removal should be avoided unless necessary for technical reasons. If it is required, it should be performed outside of the operative space using clippers, not razors. For patients colonized with methicillin-resistant S. aureus, there is supporting evidence for pretreatment with mupirocin ointment to the nares, and chlorhexidine showers for 5-10 days. Patients who have bacterial vaginosis should be treated before surgery to decrease the rate of vaginal cuff SSI.

If there is a planned or potential gastrointestinal procedure as part of the hysterectomy, the surgeon should consider using an impervious plastic wound protector in place of, or in addition to, other retractors. Preoperative oral antimicrobials with mechanical bowel preparation have been associated with decreased SSIs; however, this benefit is not observed with mechanical bowel preparation alone.

Wound closure

Surgical technique and wound closure techniques also impact SSI. Minimally invasive and vaginal hysterectomy routes are preferred, as these are associated with the lowest rates of SSI. Antimicrobial-impregnated suture materials appear to be unnecessary. Surgeons should ensure that there is delicate handling of tissues and closure of dead spaces. If the subcutaneous fat space depth measures more than 2.5 cm, it should be reapproximated with a rapidly-absorbing suture material.

Use of electrosurgery versus a scalpel when creating the incision does not appear to influence infection rates, nor does use of staples versus subcuticular suture during closure.7

Using a dilute iodine lavage in the subcutaneous space, opening a sterile closing tray, and having surgeons change gloves prior to skin closure should be considered. The CDC recommends keeping the skin dressing in place for 24 hours postoperatively.

Other strategies

Hyperglycemia is associated with impaired neutrophil response, and therefore blood glucose should be controlled before surgery (hemoglobin A1c levels of less than 7% preoperatively) and immediately postoperatively (less than 180 mg/dL within 18-24 hours after the end of anesthesia).

It is also important to minimize perioperative hypothermia (less than 35.5° F), as this also impairs the body’s immune response. Keeping operative room ambient temperatures higher, minimizing incision size, warming CO2 gas in minimally invasive procedures, warming fluids, and using extrinsic body warmers can help achieve this.

Excessive blood loss should be minimized because blood transfusion is associated with impaired macrophage function and increased risk for SSI.

In addition to teamwide (including nonsurgeon) strict adherence to hand hygiene, OR personnel should avoid unnecessary operating room traffic. Hospital officials should ensure that the facility’s ventilator systems are well maintained and that there is care and maintenance of air handlers.

Many strategies can be employed perioperatively to decrease SSI rates for hysterectomy. We advocate for a protocol-based approach (known as “bundling” strategies) to achieve consistency of practice and to maximize surgeon and institutional improvements in SSI rates. This is similar to the approach outlined in a recent consensus statement from the Council on Patient Safety in Women’s Health Care.8

A comprehensive multidisciplinary approach throughout the perioperative period is necessary. It is imperative that good communication exist with patients regarding SSIs after hysterectomy and how patients, surgeons, and hospitals can together minimize the risks of SSIs.

References

1. Altemeier WA. “Manual on Control of Infection in Surgical Patients” (Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 1984).

2. Rev Infect Dis. 1991 Sep-Oct;13(Suppl 10):S821-41.

3. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2014 Jun;35(6):605-27.

4. Obstet Gynecol. 2009 May;113(5):1180-9.

5. Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Feb;127(2):321-9.

6. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005 Feb;192(2):422-5.

7. J Gastrointest Surg. 2016 Dec;20(12):2083-92.

8. Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Dec 7. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001751.

Dr. Rossi is an assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Jackson-Moore is an associate professor in gynecologic oncology at UNC. They reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Surgical site infections are a major source of patient morbidity. They are also an important quality metric for surgeons and hospital systems, and are increasingly being linked to reimbursement.

They occur in approximately 2% of the 600,000 women undergoing hysterectomy in the United States each year. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention defines surgical site infection (SSI) as an infection that occurs within 30 days of a procedure in the part of the body where the surgery took place. Most SSIs are superficial incisional, but they also include deep incisional or organ or space infections.

Classification

The incidence of SSI varies according to the classification of the wound, as defined by the National Academy of Sciences.1 Most hysterectomies are classified as clean-contaminated wounds because they involve entry into the mucosa of the genitourinary tract. However, hysterectomy with contamination of bowel flora, or in the setting of acute infection (such as suppurative pelvic inflammatory disease) are considered a contaminated wound class, and are associated with even higher rates of SSI.

Risk factors

The risk factors associated with SSI are both modifiable and unmodifiable. Broadly speaking, they include increased risk to endogenous flora (e.g., wound classification), increased exposure to exogenous flora (e.g., inadequate protection of a wound from external pathogens), and impairment of the body’s immune mechanisms to prevent and overcome infection (e.g., hypothermia and hypoglycemia).

Unmodifiable risk factors include increasing age, a history of radiation exposure, vascular disease, and a history of prior SSIs. Modifiable risk factors include obesity, tobacco use, immunosuppressive medications, hypoalbuminemia, route of hysterectomy, hair removal, preoperative infections (such as bacterial vaginosis), surgical scrub, skin and vaginal preparation, antimicrobial prophylaxis (inappropriate choice or timing, inadequate dosing or redosing), operative time, blood transfusion, surgical skill, and operating room characteristics (ventilation, increased OR traffic, and sterilization of surgical equipment).

Antimicrobial prophylaxis

The CDC and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) have provided clear guidelines regarding methods to reduce SSI in hysterectomy.3,4 There is strong evidence for using antimicrobial prophylaxis for hysterectomy.

It is important that physicians confirm the validity of beta-lactam allergies with patients because there are higher rates of SSI with the use of non–beta-lactam regimens, even those endorsed by the CDC and ACOG.5

Antibiotics should be administered within 1 hour of skin incision, and ideally within 30 minutes. They should be discontinued within 24 hours. Dosing should be adjusted to weight, and antimicrobials should be redosed for long procedures (at intervals of two half-lives), and for increased blood loss.

Skin preparation

Hair removal should be avoided unless necessary for technical reasons. If it is required, it should be performed outside of the operative space using clippers, not razors. For patients colonized with methicillin-resistant S. aureus, there is supporting evidence for pretreatment with mupirocin ointment to the nares, and chlorhexidine showers for 5-10 days. Patients who have bacterial vaginosis should be treated before surgery to decrease the rate of vaginal cuff SSI.

If there is a planned or potential gastrointestinal procedure as part of the hysterectomy, the surgeon should consider using an impervious plastic wound protector in place of, or in addition to, other retractors. Preoperative oral antimicrobials with mechanical bowel preparation have been associated with decreased SSIs; however, this benefit is not observed with mechanical bowel preparation alone.

Wound closure

Surgical technique and wound closure techniques also impact SSI. Minimally invasive and vaginal hysterectomy routes are preferred, as these are associated with the lowest rates of SSI. Antimicrobial-impregnated suture materials appear to be unnecessary. Surgeons should ensure that there is delicate handling of tissues and closure of dead spaces. If the subcutaneous fat space depth measures more than 2.5 cm, it should be reapproximated with a rapidly-absorbing suture material.

Use of electrosurgery versus a scalpel when creating the incision does not appear to influence infection rates, nor does use of staples versus subcuticular suture during closure.7

Using a dilute iodine lavage in the subcutaneous space, opening a sterile closing tray, and having surgeons change gloves prior to skin closure should be considered. The CDC recommends keeping the skin dressing in place for 24 hours postoperatively.

Other strategies

Hyperglycemia is associated with impaired neutrophil response, and therefore blood glucose should be controlled before surgery (hemoglobin A1c levels of less than 7% preoperatively) and immediately postoperatively (less than 180 mg/dL within 18-24 hours after the end of anesthesia).

It is also important to minimize perioperative hypothermia (less than 35.5° F), as this also impairs the body’s immune response. Keeping operative room ambient temperatures higher, minimizing incision size, warming CO2 gas in minimally invasive procedures, warming fluids, and using extrinsic body warmers can help achieve this.

Excessive blood loss should be minimized because blood transfusion is associated with impaired macrophage function and increased risk for SSI.

In addition to teamwide (including nonsurgeon) strict adherence to hand hygiene, OR personnel should avoid unnecessary operating room traffic. Hospital officials should ensure that the facility’s ventilator systems are well maintained and that there is care and maintenance of air handlers.

Many strategies can be employed perioperatively to decrease SSI rates for hysterectomy. We advocate for a protocol-based approach (known as “bundling” strategies) to achieve consistency of practice and to maximize surgeon and institutional improvements in SSI rates. This is similar to the approach outlined in a recent consensus statement from the Council on Patient Safety in Women’s Health Care.8

A comprehensive multidisciplinary approach throughout the perioperative period is necessary. It is imperative that good communication exist with patients regarding SSIs after hysterectomy and how patients, surgeons, and hospitals can together minimize the risks of SSIs.

References

1. Altemeier WA. “Manual on Control of Infection in Surgical Patients” (Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 1984).

2. Rev Infect Dis. 1991 Sep-Oct;13(Suppl 10):S821-41.

3. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2014 Jun;35(6):605-27.

4. Obstet Gynecol. 2009 May;113(5):1180-9.

5. Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Feb;127(2):321-9.

6. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005 Feb;192(2):422-5.

7. J Gastrointest Surg. 2016 Dec;20(12):2083-92.

8. Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Dec 7. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001751.

Dr. Rossi is an assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Jackson-Moore is an associate professor in gynecologic oncology at UNC. They reported having no relevant financial disclosures.