User login

Hydralazine-Associated Cutaneous Vasculitis Presenting With Aerodigestive Tract Involvement

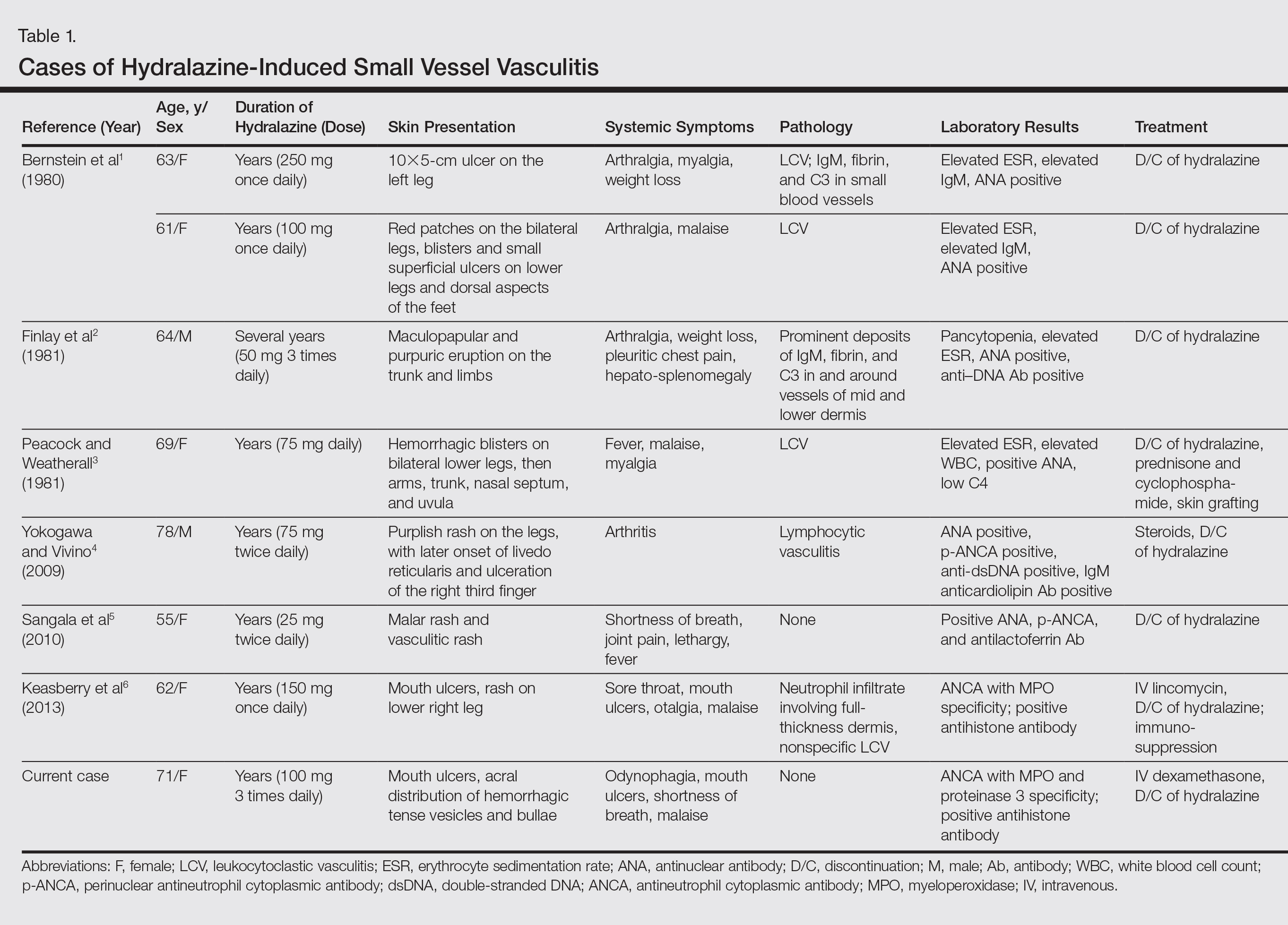

Hydralazine-induced antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)–positive vasculitis is a complex entity characterized by a distinctive clinical presentation comprising acral hemorrhagic vesiculopustules and necrotic ulcerations, at times with severe mucosal involvement. Although it is an established entity, a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms hydralazine vasculitis, ANCA positive vasculitis, and hydralazine associated vasculitis revealed a limited number of cases reported in the dermatologic literature (Table 1).1-6 We report a rare case of hydralazine-induced vasculitis associated with airway compromise and severe gastrointestinal tract bleeding.

RELATED ARTICLE: Sweet Syndrome Associated With Hydralazine-Induced Lupus Erythematosus

Case Report

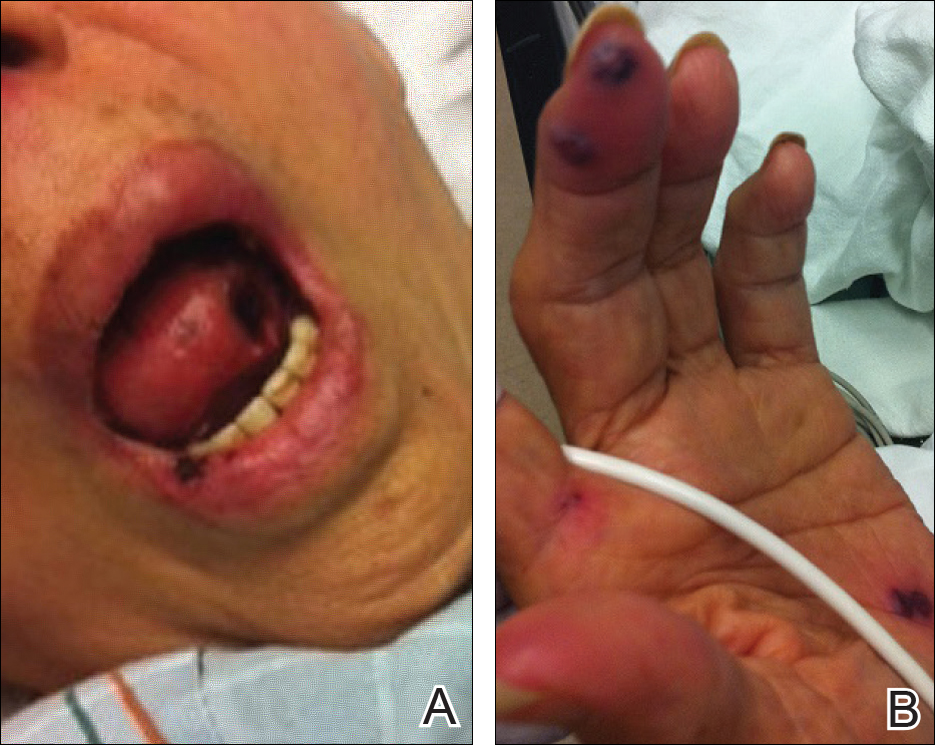

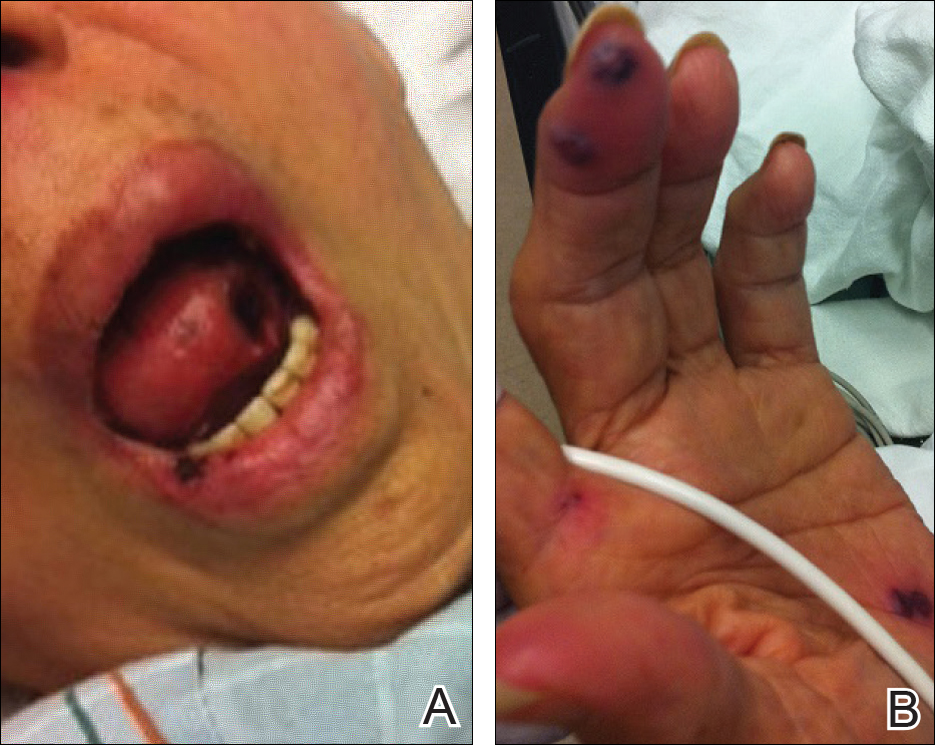

A 71-year-old woman with a history of end-stage renal disease treated with hemodialysis, as well as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and ischemic cardiomyopathy, presented to our emergency department with odynophagia, muscle weakness, shortness of breath, and a distinctive mucocutaneous eruption on the left eyelid, lips, and tongue of 2 days’ duration. Physical examination revealed an ill-appearing, afebrile, dyspneic woman with swelling of the left upper eyelid, conjunctival injection, ulcerations on the lips and tongue, and tense hemorrhagic vesicles, as well as vesiculopustules on the elbows, palms, fingers, lower legs, and toes (Figure 1). Given her dyspnea, flexible laryngoscopy was performed and revealed ulceration and edema involving the epiglottis, aryepiglottic folds, and arytenoids. The patient was intubated for airway protection and started on intravenous dexamethasone.

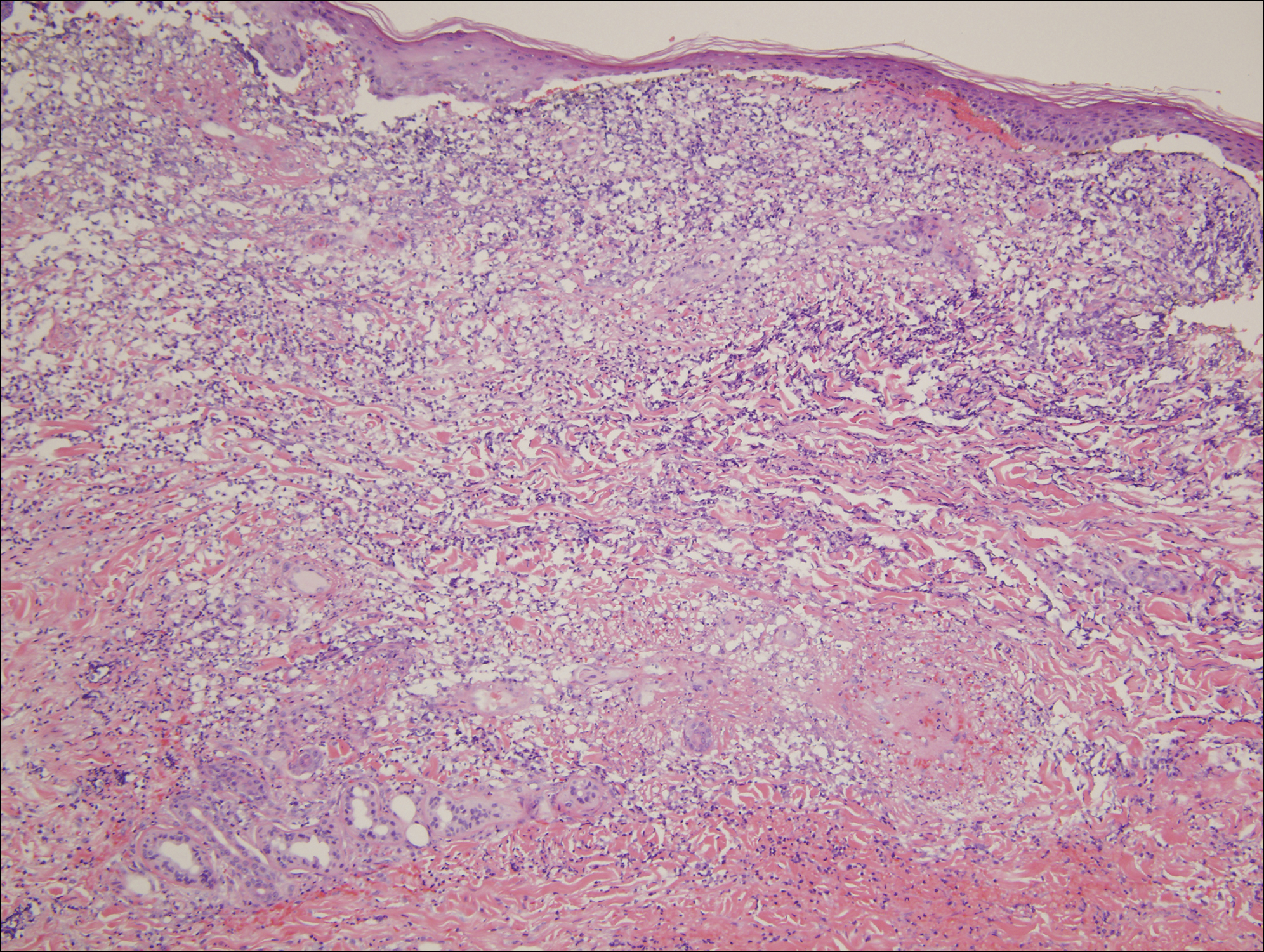

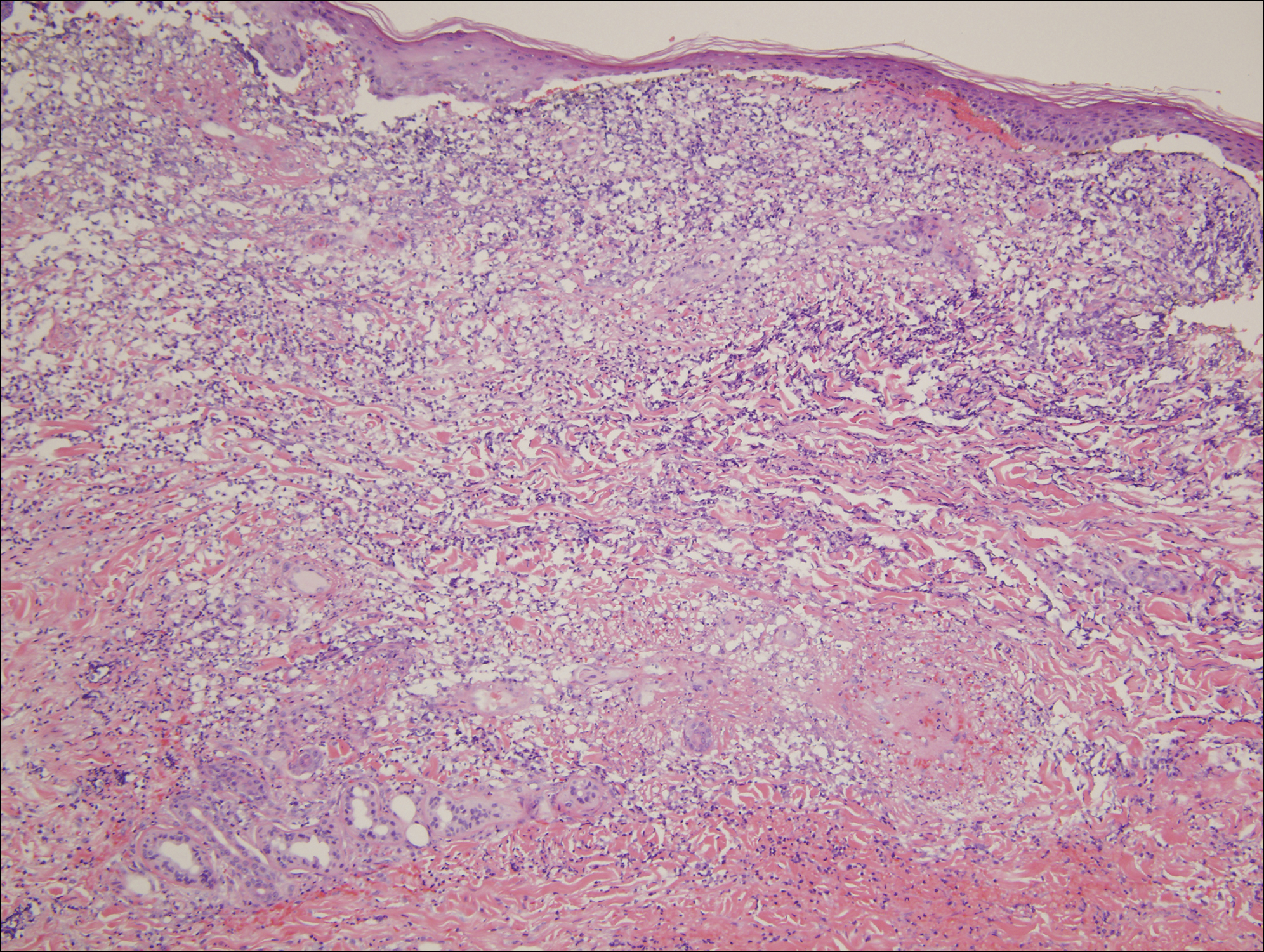

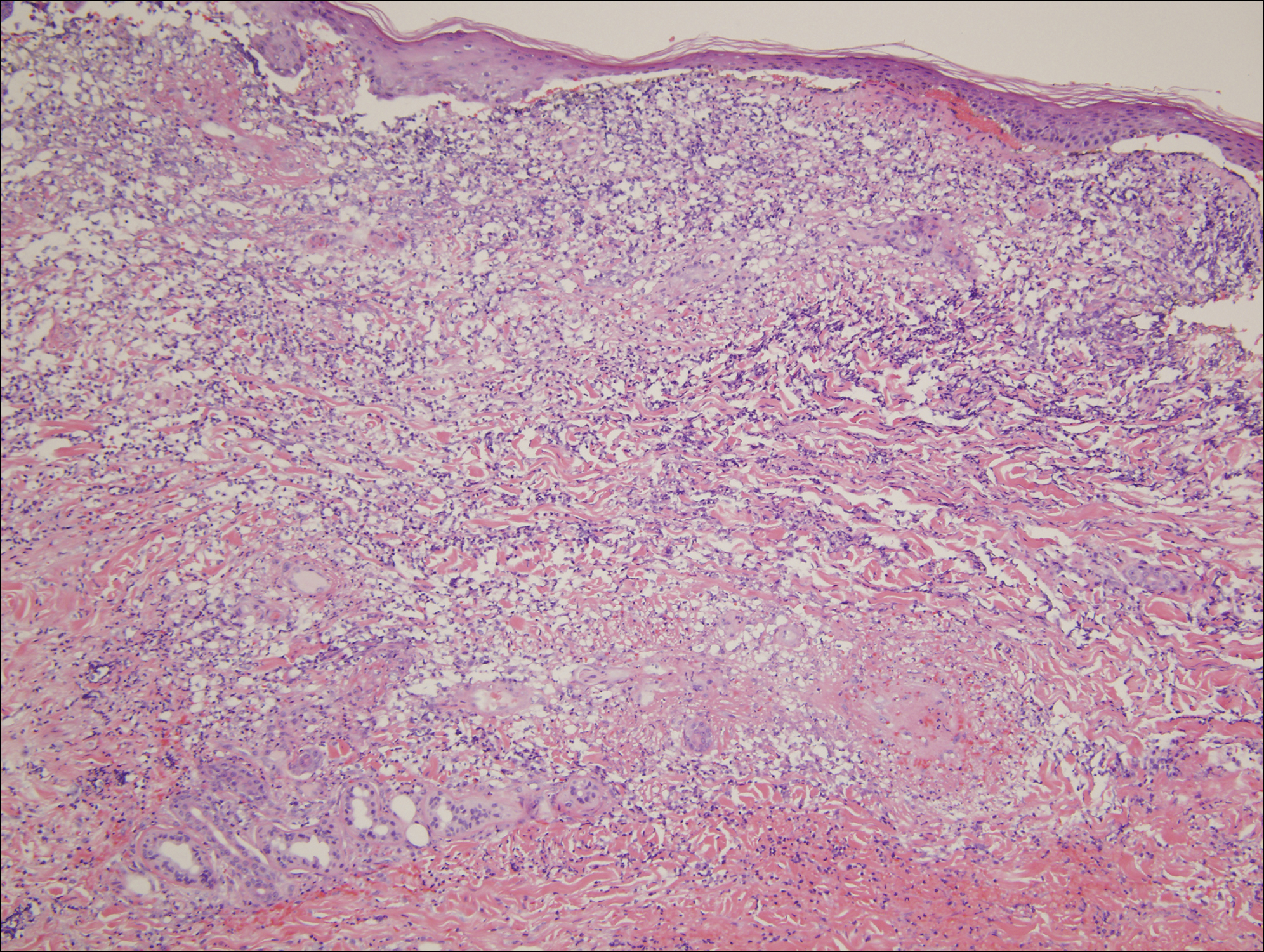

An extensive diagnostic workup commenced. Bacterial, viral, and fungal cultures of blood, skin tissue, and respiratory secretions, as well as human immunodeficiency virus screening, were all negative. Specifically, a tissue culture was performed on skin from the left thigh, viral culture and direct fluorescent antibody were performed on a vesicle on the right knee for herpes simplex virus and herpes zoster, and a superficial wound culture was taken from the left arm, all showing no growth. The patient’s home medications were reviewed and revealed she was currently taking hydralazine (100 mg 3 times daily), which was started approximately 2 years prior. Laboratory results revealed a positive antinuclear antibody titer of 1:320 (diffuse pattern), positive antihistone antibody, and positive ANCA with cytoplasmic and perinuclear accentuation (Table 2). Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays showed IgG antibodies to myeloperoxidase (MPO) and proteinase 3 (Table 2). Skin biopsies from the right lower leg and right upper arm were compatible with necrotizing leukocytoclastic vasculitis characterized by mural and luminal fibrin deposition involving capillaries and venules of the superficial and deep dermis (Figure 2). The vessel walls were infiltrated by neutrophils with concomitant leukocytoclasia. Vessels in the mid dermis were occluded by cellular fibrin thrombi. Foci of neutrophilic interface dermatitis with subepidermal bulla formation were observed. Infectious stains were negative. On direct immunofluorescence, striking homogeneous mantles of staining of IgG were present within the cutaneous vasculature.

Because the infectious workup was negative and there was no other known instigating factor of vasculitis, concern for a drug-induced process prompted thorough review of the patient’s home medications and discontinuation of hydralazine. A diagnosis of hydralazine-associated cutaneous vasculitis was made when laboratory workup confirmed no underlying infectious process or rheumatologic condition and the medication known to cause her symptoms was on her medication list. The dexamethasone dose was increased, leading to rapid improvement of her mucocutaneous findings; however, on initiation of a steroid taper, she developed substantial gastrointestinal tract bleeding. An esophageal biopsy revealed a neutrophil-rich necrotizing process that essentially mirrored the cutaneous biopsy consistent with vasculitic involvement of the gastrointestinal tract. Steroids were again increased with resolution in gastrointestinal tract bleeding.

Comment

Our case highlights a distinct clinical presentation of hydralazine-induced ANCA-positive cutaneous vasculitis associated with severe involvement of the aerodigestive tract with gastrointestinal tract bleeding and airway compromise requiring intubation. Although discontinuation of hydralazine and in certain cases the addition of immunosuppressive agents may be adequate for resolution of symptoms, some cases progress despite treatment, leading to skin grafting, amputation, and death.3,4 Therefore, early recognition of hydralazine-induced cutaneous vasculitis and discontinuation of hydralazine are of paramount importance.

Reporting hydralazine-induced vasculitis is valuable because of its unique cutaneous, extracutaneous, and serologic findings. In our case, the cutaneous vasculitis presented clinically with acral hemorrhagic vesiculopustules and necrotic ulcerations resembling septic emboli, as opposed to classic lesions of palpable purpura typical of drug-induced leukocytoclastic vasculitis. Similar cutaneous findings have been described in other cases of hydralazine-induced vasculitis, indicating that this pattern of acral pseudoembolic vesiculopustules with necrosis and ulceration is characteristic of this entity.1,3,6 In addition, involvement of the oral cavity, larynx, and gastrointestinal tract have been reported in cases of hydralazine-induced vasculitis, indicating mucosal involvement is an important feature of this disease.3,6 Although involvement of the oral mucosa, larynx, and acral sites appears to be characteristic, the exact basis for this site localization remains elusive. A precedent has been established for a similar pattern of intraoral and laryngeal involvement in other ANCA-positive vasculitic syndromes, most notably Wegener granulomatosis.7 Similarly, there are certain occlusive vasculitic syndromes that show acral localization including chronic septic vasculitis and vasculitis of collagen vascular disease.

Serologic trends can aid in diagnosing hydralazine-induced vasculitis. In theory, the nonspecific cutaneous findings, often in association with joint pain and positive antinuclear antibodies, may lead clinicians to the misdiagnosis of a connective tissue disease, such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). However, unlike SLE, hydralazine-induced vasculitis is associated with positive ANCAs, while antibodies against double-stranded DNA, a highly specific antibody for SLE, are uncommon.8,9 Our patient had both positive perinuclear ANCA with cytoplasmic ANCA as well as a positive antihistone antibodies, a combination highly suggestive of a drug-induced process.

Despite the often acute presentation of hydralazine-induced ANCA-positive vasculitis, afflicted patients have characteristically been on the drug for a long period of time. Our patient is exemplary of most reported cases, as the time from initiation of hydralazine to onset of vasculitis was 2 years.4

The mechanism by which hydralazine causes this reaction is still a matter of debate. It seems clear that there are certain at-risk populations, such as slow acetylators and patients with an underlying hypercoagulable state. There are several theories by which hydralazine induces autoantibody formation. The first involves hydralazine metabolization by MPO released from activated neutrophils to form reactive intermediate metabolites. Such metabolites can be cytotoxic and may cause abnormal degradation of chromatin in susceptible individuals, leading to an autoimmune response against histone-DNA complexes. Alternatively, hydralazine may act as a hapten and bind to MPO, inducing an immune response against the hydralazine-MPO complex, with resultant formation of anti-MPO antibodies in susceptible individuals.10

Conclusion

Hydralazine-induced ANCA-positive vasculitis is a syndromic complex characterized by a distinctive clinical presentation comprising acral hemorrhagic vesiculopustules and necrotic ulcerations, at times with severe mucosal involvement along with a characteristic ANCA-positive serologic profile. Drug withdrawal is the cornerstone of therapy, and depending on the severity of symptoms, additional immunosuppressive treatment such as corticosteroids may be necessary. Older age of onset, female gender, and underlying autoimmune diatheses likely define important risk factors. With more recognition and reporting of this disease, further trends in both clinical and serological presentation will emerge.

- Bernstein RM, Egerton-Vernon J, Webster J. Hydrallazine-induced cutaneous vasculitis. Br Med J. 1980;280:156-157.

- Finlay AY, Statham B, Knight AG. Hydrallazine-induced necrotising vasculitis. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1981;282:1703-1704.

- Peacock A, Weatherall D. Hydralazine-induced necrotising vasculitis. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1981;282:1121-1122.

- Yokogawa N, Vivino FB. Hydralazine-induced autoimmune disease: comparison to idiopathic lupus and ANCA-positive vasculitis. Mod Rheumatol. 2009;19:338-347.

- Sangala N, Lee RW, Horsfield C, et al. Combined ANCA-associated vasculitis and lupus syndrome following prolonged use of hydralazine: a timely reminder of an old foe. Int Urol Nephrol. 2010;42:503-506.

- Keasberry J, Frazier J, Isbel NM, et al. Hydralazine-induced anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-positive renal vasculitis presenting with a vasculitic syndrome, acute nephritis and a puzzling skin rash: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2013;7:20.

- Wojciechowska J, Krajewski W, Krajewski P, et al. Granulomatosis with polyangiitis in otolaryngologist practice: a review of current knowledge. Clin Exp Otorhinolaryngol. 2016;9:8-13.

- Short AK, Lockwood CM. Antigen specificity in hydralazine associated ANCA positive systemic vasculitis. QJM. 1995;88:775-783.

- Nässberger L, Hultquist R, Sturfelt G. Occurrence of anti-lactoferrin antibodies in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus, hydralazine-induced lupus, and rheumatoid arthritis. Scand J Rheumatol. 1994;23:206-210.

- Cambridge G, Wallace H, Bernstein RM, et al. Autoantibodies to myeloperoxidase in idiopathic and drug-induced systemic lupus erythematosus and vasculitis. Br J Rheumatol. 1994;33:109-114.

Hydralazine-induced antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)–positive vasculitis is a complex entity characterized by a distinctive clinical presentation comprising acral hemorrhagic vesiculopustules and necrotic ulcerations, at times with severe mucosal involvement. Although it is an established entity, a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms hydralazine vasculitis, ANCA positive vasculitis, and hydralazine associated vasculitis revealed a limited number of cases reported in the dermatologic literature (Table 1).1-6 We report a rare case of hydralazine-induced vasculitis associated with airway compromise and severe gastrointestinal tract bleeding.

RELATED ARTICLE: Sweet Syndrome Associated With Hydralazine-Induced Lupus Erythematosus

Case Report

A 71-year-old woman with a history of end-stage renal disease treated with hemodialysis, as well as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and ischemic cardiomyopathy, presented to our emergency department with odynophagia, muscle weakness, shortness of breath, and a distinctive mucocutaneous eruption on the left eyelid, lips, and tongue of 2 days’ duration. Physical examination revealed an ill-appearing, afebrile, dyspneic woman with swelling of the left upper eyelid, conjunctival injection, ulcerations on the lips and tongue, and tense hemorrhagic vesicles, as well as vesiculopustules on the elbows, palms, fingers, lower legs, and toes (Figure 1). Given her dyspnea, flexible laryngoscopy was performed and revealed ulceration and edema involving the epiglottis, aryepiglottic folds, and arytenoids. The patient was intubated for airway protection and started on intravenous dexamethasone.

An extensive diagnostic workup commenced. Bacterial, viral, and fungal cultures of blood, skin tissue, and respiratory secretions, as well as human immunodeficiency virus screening, were all negative. Specifically, a tissue culture was performed on skin from the left thigh, viral culture and direct fluorescent antibody were performed on a vesicle on the right knee for herpes simplex virus and herpes zoster, and a superficial wound culture was taken from the left arm, all showing no growth. The patient’s home medications were reviewed and revealed she was currently taking hydralazine (100 mg 3 times daily), which was started approximately 2 years prior. Laboratory results revealed a positive antinuclear antibody titer of 1:320 (diffuse pattern), positive antihistone antibody, and positive ANCA with cytoplasmic and perinuclear accentuation (Table 2). Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays showed IgG antibodies to myeloperoxidase (MPO) and proteinase 3 (Table 2). Skin biopsies from the right lower leg and right upper arm were compatible with necrotizing leukocytoclastic vasculitis characterized by mural and luminal fibrin deposition involving capillaries and venules of the superficial and deep dermis (Figure 2). The vessel walls were infiltrated by neutrophils with concomitant leukocytoclasia. Vessels in the mid dermis were occluded by cellular fibrin thrombi. Foci of neutrophilic interface dermatitis with subepidermal bulla formation were observed. Infectious stains were negative. On direct immunofluorescence, striking homogeneous mantles of staining of IgG were present within the cutaneous vasculature.

Because the infectious workup was negative and there was no other known instigating factor of vasculitis, concern for a drug-induced process prompted thorough review of the patient’s home medications and discontinuation of hydralazine. A diagnosis of hydralazine-associated cutaneous vasculitis was made when laboratory workup confirmed no underlying infectious process or rheumatologic condition and the medication known to cause her symptoms was on her medication list. The dexamethasone dose was increased, leading to rapid improvement of her mucocutaneous findings; however, on initiation of a steroid taper, she developed substantial gastrointestinal tract bleeding. An esophageal biopsy revealed a neutrophil-rich necrotizing process that essentially mirrored the cutaneous biopsy consistent with vasculitic involvement of the gastrointestinal tract. Steroids were again increased with resolution in gastrointestinal tract bleeding.

Comment

Our case highlights a distinct clinical presentation of hydralazine-induced ANCA-positive cutaneous vasculitis associated with severe involvement of the aerodigestive tract with gastrointestinal tract bleeding and airway compromise requiring intubation. Although discontinuation of hydralazine and in certain cases the addition of immunosuppressive agents may be adequate for resolution of symptoms, some cases progress despite treatment, leading to skin grafting, amputation, and death.3,4 Therefore, early recognition of hydralazine-induced cutaneous vasculitis and discontinuation of hydralazine are of paramount importance.

Reporting hydralazine-induced vasculitis is valuable because of its unique cutaneous, extracutaneous, and serologic findings. In our case, the cutaneous vasculitis presented clinically with acral hemorrhagic vesiculopustules and necrotic ulcerations resembling septic emboli, as opposed to classic lesions of palpable purpura typical of drug-induced leukocytoclastic vasculitis. Similar cutaneous findings have been described in other cases of hydralazine-induced vasculitis, indicating that this pattern of acral pseudoembolic vesiculopustules with necrosis and ulceration is characteristic of this entity.1,3,6 In addition, involvement of the oral cavity, larynx, and gastrointestinal tract have been reported in cases of hydralazine-induced vasculitis, indicating mucosal involvement is an important feature of this disease.3,6 Although involvement of the oral mucosa, larynx, and acral sites appears to be characteristic, the exact basis for this site localization remains elusive. A precedent has been established for a similar pattern of intraoral and laryngeal involvement in other ANCA-positive vasculitic syndromes, most notably Wegener granulomatosis.7 Similarly, there are certain occlusive vasculitic syndromes that show acral localization including chronic septic vasculitis and vasculitis of collagen vascular disease.

Serologic trends can aid in diagnosing hydralazine-induced vasculitis. In theory, the nonspecific cutaneous findings, often in association with joint pain and positive antinuclear antibodies, may lead clinicians to the misdiagnosis of a connective tissue disease, such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). However, unlike SLE, hydralazine-induced vasculitis is associated with positive ANCAs, while antibodies against double-stranded DNA, a highly specific antibody for SLE, are uncommon.8,9 Our patient had both positive perinuclear ANCA with cytoplasmic ANCA as well as a positive antihistone antibodies, a combination highly suggestive of a drug-induced process.

Despite the often acute presentation of hydralazine-induced ANCA-positive vasculitis, afflicted patients have characteristically been on the drug for a long period of time. Our patient is exemplary of most reported cases, as the time from initiation of hydralazine to onset of vasculitis was 2 years.4

The mechanism by which hydralazine causes this reaction is still a matter of debate. It seems clear that there are certain at-risk populations, such as slow acetylators and patients with an underlying hypercoagulable state. There are several theories by which hydralazine induces autoantibody formation. The first involves hydralazine metabolization by MPO released from activated neutrophils to form reactive intermediate metabolites. Such metabolites can be cytotoxic and may cause abnormal degradation of chromatin in susceptible individuals, leading to an autoimmune response against histone-DNA complexes. Alternatively, hydralazine may act as a hapten and bind to MPO, inducing an immune response against the hydralazine-MPO complex, with resultant formation of anti-MPO antibodies in susceptible individuals.10

Conclusion

Hydralazine-induced ANCA-positive vasculitis is a syndromic complex characterized by a distinctive clinical presentation comprising acral hemorrhagic vesiculopustules and necrotic ulcerations, at times with severe mucosal involvement along with a characteristic ANCA-positive serologic profile. Drug withdrawal is the cornerstone of therapy, and depending on the severity of symptoms, additional immunosuppressive treatment such as corticosteroids may be necessary. Older age of onset, female gender, and underlying autoimmune diatheses likely define important risk factors. With more recognition and reporting of this disease, further trends in both clinical and serological presentation will emerge.

Hydralazine-induced antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)–positive vasculitis is a complex entity characterized by a distinctive clinical presentation comprising acral hemorrhagic vesiculopustules and necrotic ulcerations, at times with severe mucosal involvement. Although it is an established entity, a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms hydralazine vasculitis, ANCA positive vasculitis, and hydralazine associated vasculitis revealed a limited number of cases reported in the dermatologic literature (Table 1).1-6 We report a rare case of hydralazine-induced vasculitis associated with airway compromise and severe gastrointestinal tract bleeding.

RELATED ARTICLE: Sweet Syndrome Associated With Hydralazine-Induced Lupus Erythematosus

Case Report

A 71-year-old woman with a history of end-stage renal disease treated with hemodialysis, as well as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and ischemic cardiomyopathy, presented to our emergency department with odynophagia, muscle weakness, shortness of breath, and a distinctive mucocutaneous eruption on the left eyelid, lips, and tongue of 2 days’ duration. Physical examination revealed an ill-appearing, afebrile, dyspneic woman with swelling of the left upper eyelid, conjunctival injection, ulcerations on the lips and tongue, and tense hemorrhagic vesicles, as well as vesiculopustules on the elbows, palms, fingers, lower legs, and toes (Figure 1). Given her dyspnea, flexible laryngoscopy was performed and revealed ulceration and edema involving the epiglottis, aryepiglottic folds, and arytenoids. The patient was intubated for airway protection and started on intravenous dexamethasone.

An extensive diagnostic workup commenced. Bacterial, viral, and fungal cultures of blood, skin tissue, and respiratory secretions, as well as human immunodeficiency virus screening, were all negative. Specifically, a tissue culture was performed on skin from the left thigh, viral culture and direct fluorescent antibody were performed on a vesicle on the right knee for herpes simplex virus and herpes zoster, and a superficial wound culture was taken from the left arm, all showing no growth. The patient’s home medications were reviewed and revealed she was currently taking hydralazine (100 mg 3 times daily), which was started approximately 2 years prior. Laboratory results revealed a positive antinuclear antibody titer of 1:320 (diffuse pattern), positive antihistone antibody, and positive ANCA with cytoplasmic and perinuclear accentuation (Table 2). Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays showed IgG antibodies to myeloperoxidase (MPO) and proteinase 3 (Table 2). Skin biopsies from the right lower leg and right upper arm were compatible with necrotizing leukocytoclastic vasculitis characterized by mural and luminal fibrin deposition involving capillaries and venules of the superficial and deep dermis (Figure 2). The vessel walls were infiltrated by neutrophils with concomitant leukocytoclasia. Vessels in the mid dermis were occluded by cellular fibrin thrombi. Foci of neutrophilic interface dermatitis with subepidermal bulla formation were observed. Infectious stains were negative. On direct immunofluorescence, striking homogeneous mantles of staining of IgG were present within the cutaneous vasculature.

Because the infectious workup was negative and there was no other known instigating factor of vasculitis, concern for a drug-induced process prompted thorough review of the patient’s home medications and discontinuation of hydralazine. A diagnosis of hydralazine-associated cutaneous vasculitis was made when laboratory workup confirmed no underlying infectious process or rheumatologic condition and the medication known to cause her symptoms was on her medication list. The dexamethasone dose was increased, leading to rapid improvement of her mucocutaneous findings; however, on initiation of a steroid taper, she developed substantial gastrointestinal tract bleeding. An esophageal biopsy revealed a neutrophil-rich necrotizing process that essentially mirrored the cutaneous biopsy consistent with vasculitic involvement of the gastrointestinal tract. Steroids were again increased with resolution in gastrointestinal tract bleeding.

Comment

Our case highlights a distinct clinical presentation of hydralazine-induced ANCA-positive cutaneous vasculitis associated with severe involvement of the aerodigestive tract with gastrointestinal tract bleeding and airway compromise requiring intubation. Although discontinuation of hydralazine and in certain cases the addition of immunosuppressive agents may be adequate for resolution of symptoms, some cases progress despite treatment, leading to skin grafting, amputation, and death.3,4 Therefore, early recognition of hydralazine-induced cutaneous vasculitis and discontinuation of hydralazine are of paramount importance.

Reporting hydralazine-induced vasculitis is valuable because of its unique cutaneous, extracutaneous, and serologic findings. In our case, the cutaneous vasculitis presented clinically with acral hemorrhagic vesiculopustules and necrotic ulcerations resembling septic emboli, as opposed to classic lesions of palpable purpura typical of drug-induced leukocytoclastic vasculitis. Similar cutaneous findings have been described in other cases of hydralazine-induced vasculitis, indicating that this pattern of acral pseudoembolic vesiculopustules with necrosis and ulceration is characteristic of this entity.1,3,6 In addition, involvement of the oral cavity, larynx, and gastrointestinal tract have been reported in cases of hydralazine-induced vasculitis, indicating mucosal involvement is an important feature of this disease.3,6 Although involvement of the oral mucosa, larynx, and acral sites appears to be characteristic, the exact basis for this site localization remains elusive. A precedent has been established for a similar pattern of intraoral and laryngeal involvement in other ANCA-positive vasculitic syndromes, most notably Wegener granulomatosis.7 Similarly, there are certain occlusive vasculitic syndromes that show acral localization including chronic septic vasculitis and vasculitis of collagen vascular disease.

Serologic trends can aid in diagnosing hydralazine-induced vasculitis. In theory, the nonspecific cutaneous findings, often in association with joint pain and positive antinuclear antibodies, may lead clinicians to the misdiagnosis of a connective tissue disease, such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). However, unlike SLE, hydralazine-induced vasculitis is associated with positive ANCAs, while antibodies against double-stranded DNA, a highly specific antibody for SLE, are uncommon.8,9 Our patient had both positive perinuclear ANCA with cytoplasmic ANCA as well as a positive antihistone antibodies, a combination highly suggestive of a drug-induced process.

Despite the often acute presentation of hydralazine-induced ANCA-positive vasculitis, afflicted patients have characteristically been on the drug for a long period of time. Our patient is exemplary of most reported cases, as the time from initiation of hydralazine to onset of vasculitis was 2 years.4

The mechanism by which hydralazine causes this reaction is still a matter of debate. It seems clear that there are certain at-risk populations, such as slow acetylators and patients with an underlying hypercoagulable state. There are several theories by which hydralazine induces autoantibody formation. The first involves hydralazine metabolization by MPO released from activated neutrophils to form reactive intermediate metabolites. Such metabolites can be cytotoxic and may cause abnormal degradation of chromatin in susceptible individuals, leading to an autoimmune response against histone-DNA complexes. Alternatively, hydralazine may act as a hapten and bind to MPO, inducing an immune response against the hydralazine-MPO complex, with resultant formation of anti-MPO antibodies in susceptible individuals.10

Conclusion

Hydralazine-induced ANCA-positive vasculitis is a syndromic complex characterized by a distinctive clinical presentation comprising acral hemorrhagic vesiculopustules and necrotic ulcerations, at times with severe mucosal involvement along with a characteristic ANCA-positive serologic profile. Drug withdrawal is the cornerstone of therapy, and depending on the severity of symptoms, additional immunosuppressive treatment such as corticosteroids may be necessary. Older age of onset, female gender, and underlying autoimmune diatheses likely define important risk factors. With more recognition and reporting of this disease, further trends in both clinical and serological presentation will emerge.

- Bernstein RM, Egerton-Vernon J, Webster J. Hydrallazine-induced cutaneous vasculitis. Br Med J. 1980;280:156-157.

- Finlay AY, Statham B, Knight AG. Hydrallazine-induced necrotising vasculitis. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1981;282:1703-1704.

- Peacock A, Weatherall D. Hydralazine-induced necrotising vasculitis. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1981;282:1121-1122.

- Yokogawa N, Vivino FB. Hydralazine-induced autoimmune disease: comparison to idiopathic lupus and ANCA-positive vasculitis. Mod Rheumatol. 2009;19:338-347.

- Sangala N, Lee RW, Horsfield C, et al. Combined ANCA-associated vasculitis and lupus syndrome following prolonged use of hydralazine: a timely reminder of an old foe. Int Urol Nephrol. 2010;42:503-506.

- Keasberry J, Frazier J, Isbel NM, et al. Hydralazine-induced anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-positive renal vasculitis presenting with a vasculitic syndrome, acute nephritis and a puzzling skin rash: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2013;7:20.

- Wojciechowska J, Krajewski W, Krajewski P, et al. Granulomatosis with polyangiitis in otolaryngologist practice: a review of current knowledge. Clin Exp Otorhinolaryngol. 2016;9:8-13.

- Short AK, Lockwood CM. Antigen specificity in hydralazine associated ANCA positive systemic vasculitis. QJM. 1995;88:775-783.

- Nässberger L, Hultquist R, Sturfelt G. Occurrence of anti-lactoferrin antibodies in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus, hydralazine-induced lupus, and rheumatoid arthritis. Scand J Rheumatol. 1994;23:206-210.

- Cambridge G, Wallace H, Bernstein RM, et al. Autoantibodies to myeloperoxidase in idiopathic and drug-induced systemic lupus erythematosus and vasculitis. Br J Rheumatol. 1994;33:109-114.

- Bernstein RM, Egerton-Vernon J, Webster J. Hydrallazine-induced cutaneous vasculitis. Br Med J. 1980;280:156-157.

- Finlay AY, Statham B, Knight AG. Hydrallazine-induced necrotising vasculitis. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1981;282:1703-1704.

- Peacock A, Weatherall D. Hydralazine-induced necrotising vasculitis. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1981;282:1121-1122.

- Yokogawa N, Vivino FB. Hydralazine-induced autoimmune disease: comparison to idiopathic lupus and ANCA-positive vasculitis. Mod Rheumatol. 2009;19:338-347.

- Sangala N, Lee RW, Horsfield C, et al. Combined ANCA-associated vasculitis and lupus syndrome following prolonged use of hydralazine: a timely reminder of an old foe. Int Urol Nephrol. 2010;42:503-506.

- Keasberry J, Frazier J, Isbel NM, et al. Hydralazine-induced anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-positive renal vasculitis presenting with a vasculitic syndrome, acute nephritis and a puzzling skin rash: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2013;7:20.

- Wojciechowska J, Krajewski W, Krajewski P, et al. Granulomatosis with polyangiitis in otolaryngologist practice: a review of current knowledge. Clin Exp Otorhinolaryngol. 2016;9:8-13.

- Short AK, Lockwood CM. Antigen specificity in hydralazine associated ANCA positive systemic vasculitis. QJM. 1995;88:775-783.

- Nässberger L, Hultquist R, Sturfelt G. Occurrence of anti-lactoferrin antibodies in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus, hydralazine-induced lupus, and rheumatoid arthritis. Scand J Rheumatol. 1994;23:206-210.

- Cambridge G, Wallace H, Bernstein RM, et al. Autoantibodies to myeloperoxidase in idiopathic and drug-induced systemic lupus erythematosus and vasculitis. Br J Rheumatol. 1994;33:109-114.

Practice Points

- Hydralazine-induced small vessel vasculitis has a characteristic pattern of acral pseudoembolic vesiculopustules with necrosis and ulceration, along with involvement of the aerodigestive tract.

- Unlike systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), hydralazine-induced vasculitis is associated with positive antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, while antibodies against double-stranded DNA, a highly specific antibody for SLE, are uncommon.

- Increased recognition of the clinical and serological features of hydralazine-induced small vessel vasculitis may lead to earlier recognition of this disease and decreased time to discontinuation of hydralazine when appropriate.