User login

A 69-year-old woman with double vision and lower-extremity weakness

A 69-year-old woman was admitted to the hospital with double vision, weakness in the lower extremities, sensory loss, pain, and falls. Her symptoms started with sudden onset of horizontal diplopia 6 weeks before, followed by gradually worsening lower-extremity weakness, as well as ataxia and patchy and bilateral radicular burning leg pain more pronounced on the right. Her medical history included narcolepsy, obstructive sleep apnea, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and bilateral knee replacements for osteoarthritis.

Neurologic examination showed inability to abduct the right eye, bilateral hip flexion weakness, decreased pinprick response, decreased proprioception, and diminished muscle stretch reflexes in the lower extremities. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain without contrast and magnetic resonance angiography of the brain and carotid arteries showed no evidence of acute stroke. No abnormalities were noted on electrocardiography and echocardiography.

A diagnosis of idiopathic peripheral neuropathy was made, and outpatient physical therapy was recommended. Over the subsequent 2 weeks, her condition declined to the point where she needed a walker. She continued to have worsening leg weakness with falls, prompting hospital readmission.

INITIAL EVALUATION

In addition to her diplopia and weakness, she said she had lost 15 pounds since the onset of symptoms and had experienced symptoms suggesting urinary retention.

Physical examination

Her temperature was 37°C (98.6°F), heart rate 79 beats per minute, blood pressure 117/86 mm Hg, respiratory rate 14 breaths per minute, and oxygen saturation 98% on room air. Examination of the head, neck, heart, lung, abdomen, lymph nodes, and extremities yielded nothing remarkable except for chronic venous changes in the lower extremities.

The neurologic examination showed incomplete lateral gaze bilaterally (cranial nerve VI dysfunction). Strength in the upper extremities was normal. In the legs, the Medical Research Council scale score for proximal muscle strength was 2 to 3 out of 5, and for distal muscles 3 to 4 out of 5, with the right side worse than the left and flexors and extensors affected equally. Muscle stretch reflexes were absent in both lower extremities and the left upper extremity, but intact in the right upper extremity. No abnormal corticospinal tract reflexes were elicited.

Sensory testing revealed diminished pin-prick perception in a length-dependent fashion in the lower extremities, reduced 50% compared with the hands. Gait could not be assessed due to weakness.

Initial laboratory testing

Results of initial laboratory tests—complete blood cell count, complete metabolic panel, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, thyroid-stimulating hormone, and hemoglobin A1c—were unremarkable.

FURTHER EVALUATION AND DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

1. Which of the following is the most likely diagnosis at this point?

- Cerebral infarction

- Guillain-Barré syndrome

- Progressive polyneuropathy

- Transverse myelitis

- Polyradiculopathy

In the absence of definitive diagnostic tests, all of the above options were considered in the differential diagnosis for this patient.

Cerebral infarction

Although acute-onset diplopia can be explained by brainstem stroke involving cranial nerve nuclei or their projections, the onset of diplopia with progressive bilateral lower-extremity weakness makes stroke unlikely. Flaccid paralysis, areflexia of the lower extremities, and sensory involvement can also be caused by acute anterior spinal artery occlusion leading to spinal cord infarction; however, the deficits are usually maximal at onset.

Guillain-Barré syndrome

The combination of acute-subacute progressive ascending weakness, sensory involvement, and diminished or absent reflexes is typical of Guillain-Barré syndrome. Cranial nerve involvement can overlap with the more typical features of the syndrome. However, most patients reach the nadir of their disease by 4 weeks after initial symptom onset, even without treatment.1 This patient’s condition continued to worsen over 8 weeks. In addition, the asymmetric lower-extremity weakness and sparing of the arms are atypical for Guillain-Barré syndrome.

Given the progression of symptoms, chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy is also a consideration, typically presenting as a relapsing or progressive neuropathy in proximal and distal muscles and worsening over at least an 8-week period.2

The initial workup for Guillain-Barré syndrome or chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy includes lumbar puncture to assess for albuminocytologic dissociation (elevated protein with normal white blood cell count) in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), and electromyography (EMG) to assess for neurophysiologic evidence of peripheral nerve demyelination. In Miller-Fisher syndrome, a rare variant of Guillain-Barré syndrome characterized by ataxia, ophthalmoparesis, and areflexia, serum ganglioside antibodies to GQ1b are found in over 90% of patients.3,4 Although MRI of the spine is not necessary to diagnose Guillain-Barré syndrome, it is often done to exclude other causes of lower-extremity weakness such as spinal cord or cauda equina compression that would require urgent neurosurgical consultation. MRI can support the diagnosis of Guillain-Barré syndrome when it reveals enhancement of the spinal nerve roots or cauda equina.

Other polyneuropathies

Polyneuropathy is caused by a variety of diseases that affect the function of peripheral motor, sensory, or autonomic nerves. The differential diagnosis is broad and involves inflammatory diseases (including autoimmune and paraneoplastic causes), hereditary disorders, infection, toxicity, and ischemic and nutritional deficiencies.5 Polyneuropathy can present in a distal-predominant, generalized, or asymmetric pattern involving individual nerve trunks termed “mononeuropathy multiplex,” as in our patient’s presentation. The initial workup includes EMG and a battery of serologic tests. In cases of severe and progressive polyneuropathy, nerve biopsy can assess for the presence of vasculitis, amyloidosis, and paraprotein deposition.

Transverse myelitis

Transverse myelitis is an inflammatory myelopathy that usually presents with acute or subacute weakness of the upper extremities or lower extremities, or both, corresponding to the level of the lesion, hyperreflexia, bladder and bowel dysfunction, spinal level of sensory loss, and autonomic involvement.6 The differential diagnosis of acute myelopathy includes:

- Infection (eg, herpes simplex virus, West Nile virus, Lyme disease, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, human immunodeficiency virus)

- Systemic inflammatory disease (systemic lupus erythematosus, sarcoidosis, Sjögren syndrome, scleroderma, paraneoplastic syndrome)

- Central nervous system demyelinating disease (acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, multiple sclerosis, neuromyelitis optica)

- Vascular malformation (dural arteriovenous fistula)

- Compression due to tumor, bleeding, disc herniation, infection, or abscess.

The workup involves laboratory tests to exclude systemic inflammatory and infectious causes, as well as MRI of the spine with and without contrast to identify a causative lesion. Lumbar puncture and CSF analysis may show pleocytosis, elevated protein concentration, and increased intrathecal immunoglobulin G (IgG) index.7

Although our patient’s presentation with subacute lower-extremity weakness, sensory changes, and bladder dysfunction were consistent with transverse myelitis, her cranial nerve abnormalities would be atypical for it.

Polyradiculopathy

Polyradiculopathy has many possible causes. In the United States, the most common causes are lumbar spondylosis, lumbar canal stenosis, and diabetic polyradiculoneuropathy.

When multiple spinal segments are affected, leptomeningeal disease involving the arachnoid and pia mater should be considered. Causes include malignant invasion, inflammatory cell accumulation, and protein deposition, leading to patchy but widespread dysfunction of spinal nerve roots and cranial nerves. Specific causes are myriad and include carcinomatous meningitis,8 syphilis, tuberculosis, sarcoidosis, and paraproteinemias. CSF and MRI changes are often nonspecific, leading to the need for meningeal biopsy for diagnosis.

CASE CONTINUED

During her hospitalization, our patient developed acute right upper and lower facial weakness consistent with peripheral facial mononeuropathy. Bilateral lower-extremity weakness progressed to disabling paraparesis.

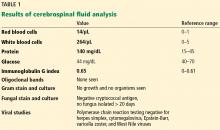

She underwent lumbar puncture and CSF analysis (Table 1). The most notable findings were significant pleocytosis (72% lymphocytic predominance), protein elevation, and elevated IgG index (indicative of elevated intrathecal immunoglobulin synthesis in the central nervous system). Viral, bacterial, and fungal studies were negative. Guillain-Barré syndrome, other polyneuropathies, and spinal cord infarction would not be expected with these CSF features.

Surface EMG demonstrated normal sensory responses, and needle EMG showed chronic and active motor axon loss in the L3 and S1 root distributions, suggesting polyradiculopathy without polyneuropathy. These findings would not be expected in typical acute transverse myelitis but could be seen with spinal cord infarction.

MRI of the entire spine with and without contrast showed cauda equina nerve root thickening and enhancement, especially involving the L5 and S1 roots (Figure 1). The spinal cord appeared normal. These findings further supported polyradiculopathy and a leptomeningeal process.

Further evaluation included chest radiography, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, hemoglobin A1c, human immunodeficiency virus testing, antinuclear antibody, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, extractable nuclear antibody, GQ1b antibody, serum and CSF paraneoplastic panels, levels of vitamin B1, B12, and B6, copper, and ceruloplasmin, and a screen for heavy metals. All results were within normal ranges.

ESTABLISHING THE DIAGNOSIS

Serum monoclonal protein analysis with immunofixation revealed IgM kappa monoclonal gammopathy with an IgM level of 1,570 (reference range 53–334 mg/dL) and M-spike 0.75 (0.00 mg/dL), serum free kappa light chains 61.1 (3.30–19.40 mg/L), lambda 9.3 (5.7–26.3 mg/L), and kappa-lambda ratio 6.57 (0.26–1.65).

2. Which is the best next step in this patient’s neurologic evaluation?

- Test CSF angiotensin-converting enzyme level

- CSF cytology

- Meningeal biopsy

- Peripheral nerve biopsy

Given the high suspicion for malignancy, CSF cytology was performed and showed increased numbers of mononuclear chronic inflammatory cells, including a mixture of lymphocytes and monocytes, favoring a reactive lymphoid pleocytosis. Flow cytometry indicated the presence of a monoclonal, CD5- and CD10- negative, B-cell lymphoproliferative disorder. The immunophenotypic findings were not specific for a single diagnosis. The differential diagnosis included marginal zone lymphoma and lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma.

3. Given the presence of serum IgM monoclonal gammopathy in this patient, which is the most likely diagnosis?

- Neurosarcoidosis

- Multiple myeloma

- Waldenström macroglobulinemia

- Carcinomatous meningitis

Study of bone marrow biopsy demonstrated limited bone marrow involvement (1%) by a lymphoproliferative disorder with plasmacytoid features, and DNA testing detected an MYD88 L265P mutation, reported to be present in 90% of patients with Waldenström macroglobulinemia.9 This finding confirmed the diagnosis of Waldenström macroglobulinemia with central nervous system involvement. Our patient began therapy with rituximab and methotrexate, which resulted in some improvement in strength, gait, and vision.

WALDENSTRÖM MACROGLOBULINEMIA AND BING-NEEL SYNDROME

Waldenström macroglobulinemia is a lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma associated with a monoclonal IgM protein.10 It is considered a paraproteinemic disorder, similar to multiple myeloma. The presenting symptoms and complications are related to direct tumor infiltration, hyperviscosity syndrome, and deposition of IgM in various tissues.11,12

Waldenström macroglobulinemia is usually indolent, and treatment is reserved for patients with symptoms.13,14 It includes rituximab, usually in combination with chemotherapy or other targeted agents.15,16

Paraneoplastic antibody-mediated polyneuropathy may occur in these patients. However, the pattern is usually symmetrical clinically, with demyelination on EMG, and is not associated with cranial nerve or meningeal involvement. Management with plasmapheresis, corticosteroids, and intravenous immunoglobulin has not been shown to be effective.17

Involvement of the central nervous system as a complication of Waldenström macroglobulinemia has been described as Bing-Neel syndrome. It can present as diffuse malignant cell infiltration of the leptomeningeal space, white matter, or spinal cord, or in a tumoral form presenting as intraparenchymal masses or nodular lesions. The distinction between the tumoral and diffuse forms is based primarily on imaging findings.18

In a report of 44 patients with Bing-Neel syndrome, 36% presented with the disorder as the initial manifestation of Waldenström macroglobulinemia.18 The primary presenting symptoms were imbalance and gait difficulty (48%) and cranial nerve involvement (36%), which presented as predominantly facial or oculomotor nerve palsy. Cauda equina syndrome with motor involvement (seen in our patient) occurred in 14% of patients. Other presenting symptoms included cognitive impairment, sensory deficits, headache, dysarthria, aphasia, and seizures.

LEARNING POINTS

The differential diagnosis for patients presenting with multifocal neurologic symptoms can be broad, and a systematic approach to the diagnosis is necessary. Localizing the lesion is important in determining the diagnosis for patients presenting with neurologic symptoms. The process of localization begins with taking the history, is further refined during the examination, and is confirmed with diagnostic studies. Atypical presentations of relatively common neurologic diseases such as Guillain-Barré syndrome, transverse myelitis, and peripheral polyneuropathy do occur, but uncommon diagnoses need to be considered when support for the initial diagnosis is lacking.

- Fokke C, van den Berg B, Drenthen J, Walgaard C, van Doorn PA, Jacobs BC. Diagnosis of Guillain-Barre syndrome and validation of Brighton criteria. Brain 2014; 137(Pt 1):33–43. doi:10.1093/brain/awt285

- Mathey EK, Park SB, Hughes RA, et al. Chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy: from pathology to phenotype. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2015; 86(9):973–985. doi:10.1136/jnnp-2014-309697

- Chiba A, Kusunoki S, Obata H, Machinami R, Kanazawa I. Serum anti-GQ1b IgG antibody is associated with ophthalmoplegia in Miller Fisher syndrome and Guillain-Barré syndrome: clinical and immunohistochemical studies. Neurology 1993; 43(10):1911–1917. pmid:8413947

- Teener J. Miller Fisher’s syndrome. Semin Neurol 2012; 32(5):512–516. doi:10.1055/s-0033-1334470

- Watson JC, Dyck PJ. Peripheral neuropathy: a practical approach to diagnosis and symptom management. Mayo Clin Proc 2015; 90(7):940–951. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.05.004

- Greenberg BM. Treatment of acute transverse myelitis and its early complications. Continuum (Minneap Minn) 2011; 17(4):733–743. doi:10.1212/01.CON.0000403792.36161.f5

- West TW. Transverse myelitis—a review of the presentation, diagnosis, and initial management. Discov Med 2013; 16(88):167–177. pmid:24099672

- Le Rhun E, Taillibert S, Chamberlain MC. Carcinomatous meningitis: leptomeningeal metastases in solid tumors. Surg Neurol Int 2013; 4(suppl 4):S265–S288. doi:10.4103/2152-7806.111304

- Treon SP, Xu L, Yang G, et al. MYD88 L265P somatic mutation in Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia. N Engl J Med 2012; 367(9):826–833. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1200710

- Owen RG, Treon SP, Al-Katib A, et al. Clinicopathological definition of Waldenstrom’s macroglobulinemia: consensus panel recommendations from the Second International Workshop on Waldenstrom’s Macroglobulinemia. Semin Oncol 2003; 30(2):110–115. doi:10.1053/sonc.2003.50082

- Björkholm M, Johansson E, Papamichael D, et al. Patterns of clinical presentation, treatment, and outcome in patients with Waldenstrom’s macroglobulinemia: a two-institution study. Semin Oncol 2003; 30(2):226–230. doi:10.1053/sonc.2003.50054

- Rison RA, Beydoun SR. Paraproteinemic neuropathy: a practical review. BMC Neurol 2016; 16:13. doi:10.1186/s12883-016-0532-4

- Kyle RA, Benson J, Larson D, et al. IgM monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance and smoldering Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma 2009; 9(1):17–18. doi:10.3816/CLM.2009.n.002

- Kyle RA, Benson JT, Larson DR, et al. Progression in smoldering Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia: long-term results. Blood 2012; 119(19):4462–4466. doi:10.1182/blood-2011-10-384768

- Leblond V, Kastritis E, Advani R, et al. Treatment recommendations from the Eighth International Workshop on Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia. Blood 2016; 128(10):1321–1328. doi:10.1182/blood-2016-04-711234

- Kapoor P, Ansell SM, Fonseca R, et al. Diagnosis and management of Waldenström macroglobulinemia: Mayo stratification of macroglobulinemia and risk-adapted therapy (mSMART) guidelines 2016. JAMA Oncol 2017; 3(9):1257–1265. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.5763

- D’Sa S, Kersten MJ, Castillo JJ, et al. Investigation and management of IgM and Waldenström-associated peripheral neuropathies: recommendations from the IWWM-8 consensus panel. Br J Haematol 2017; 176(5):728–742. doi:10.1111/bjh.14492

- Simon L, Fitsiori A, Lemal R, et al. Bing-Neel syndrome, a rare complication of Waldenström macroglobulinemia: analysis of 44 cases and review of the literature. A study on behalf of the French Innovative Leukemia Organization (FILO). Haematologica 2015; 100(12):1587–1594. doi:10.3324/haematol.2015.133744

A 69-year-old woman was admitted to the hospital with double vision, weakness in the lower extremities, sensory loss, pain, and falls. Her symptoms started with sudden onset of horizontal diplopia 6 weeks before, followed by gradually worsening lower-extremity weakness, as well as ataxia and patchy and bilateral radicular burning leg pain more pronounced on the right. Her medical history included narcolepsy, obstructive sleep apnea, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and bilateral knee replacements for osteoarthritis.

Neurologic examination showed inability to abduct the right eye, bilateral hip flexion weakness, decreased pinprick response, decreased proprioception, and diminished muscle stretch reflexes in the lower extremities. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain without contrast and magnetic resonance angiography of the brain and carotid arteries showed no evidence of acute stroke. No abnormalities were noted on electrocardiography and echocardiography.

A diagnosis of idiopathic peripheral neuropathy was made, and outpatient physical therapy was recommended. Over the subsequent 2 weeks, her condition declined to the point where she needed a walker. She continued to have worsening leg weakness with falls, prompting hospital readmission.

INITIAL EVALUATION

In addition to her diplopia and weakness, she said she had lost 15 pounds since the onset of symptoms and had experienced symptoms suggesting urinary retention.

Physical examination

Her temperature was 37°C (98.6°F), heart rate 79 beats per minute, blood pressure 117/86 mm Hg, respiratory rate 14 breaths per minute, and oxygen saturation 98% on room air. Examination of the head, neck, heart, lung, abdomen, lymph nodes, and extremities yielded nothing remarkable except for chronic venous changes in the lower extremities.

The neurologic examination showed incomplete lateral gaze bilaterally (cranial nerve VI dysfunction). Strength in the upper extremities was normal. In the legs, the Medical Research Council scale score for proximal muscle strength was 2 to 3 out of 5, and for distal muscles 3 to 4 out of 5, with the right side worse than the left and flexors and extensors affected equally. Muscle stretch reflexes were absent in both lower extremities and the left upper extremity, but intact in the right upper extremity. No abnormal corticospinal tract reflexes were elicited.

Sensory testing revealed diminished pin-prick perception in a length-dependent fashion in the lower extremities, reduced 50% compared with the hands. Gait could not be assessed due to weakness.

Initial laboratory testing

Results of initial laboratory tests—complete blood cell count, complete metabolic panel, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, thyroid-stimulating hormone, and hemoglobin A1c—were unremarkable.

FURTHER EVALUATION AND DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

1. Which of the following is the most likely diagnosis at this point?

- Cerebral infarction

- Guillain-Barré syndrome

- Progressive polyneuropathy

- Transverse myelitis

- Polyradiculopathy

In the absence of definitive diagnostic tests, all of the above options were considered in the differential diagnosis for this patient.

Cerebral infarction

Although acute-onset diplopia can be explained by brainstem stroke involving cranial nerve nuclei or their projections, the onset of diplopia with progressive bilateral lower-extremity weakness makes stroke unlikely. Flaccid paralysis, areflexia of the lower extremities, and sensory involvement can also be caused by acute anterior spinal artery occlusion leading to spinal cord infarction; however, the deficits are usually maximal at onset.

Guillain-Barré syndrome

The combination of acute-subacute progressive ascending weakness, sensory involvement, and diminished or absent reflexes is typical of Guillain-Barré syndrome. Cranial nerve involvement can overlap with the more typical features of the syndrome. However, most patients reach the nadir of their disease by 4 weeks after initial symptom onset, even without treatment.1 This patient’s condition continued to worsen over 8 weeks. In addition, the asymmetric lower-extremity weakness and sparing of the arms are atypical for Guillain-Barré syndrome.

Given the progression of symptoms, chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy is also a consideration, typically presenting as a relapsing or progressive neuropathy in proximal and distal muscles and worsening over at least an 8-week period.2

The initial workup for Guillain-Barré syndrome or chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy includes lumbar puncture to assess for albuminocytologic dissociation (elevated protein with normal white blood cell count) in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), and electromyography (EMG) to assess for neurophysiologic evidence of peripheral nerve demyelination. In Miller-Fisher syndrome, a rare variant of Guillain-Barré syndrome characterized by ataxia, ophthalmoparesis, and areflexia, serum ganglioside antibodies to GQ1b are found in over 90% of patients.3,4 Although MRI of the spine is not necessary to diagnose Guillain-Barré syndrome, it is often done to exclude other causes of lower-extremity weakness such as spinal cord or cauda equina compression that would require urgent neurosurgical consultation. MRI can support the diagnosis of Guillain-Barré syndrome when it reveals enhancement of the spinal nerve roots or cauda equina.

Other polyneuropathies

Polyneuropathy is caused by a variety of diseases that affect the function of peripheral motor, sensory, or autonomic nerves. The differential diagnosis is broad and involves inflammatory diseases (including autoimmune and paraneoplastic causes), hereditary disorders, infection, toxicity, and ischemic and nutritional deficiencies.5 Polyneuropathy can present in a distal-predominant, generalized, or asymmetric pattern involving individual nerve trunks termed “mononeuropathy multiplex,” as in our patient’s presentation. The initial workup includes EMG and a battery of serologic tests. In cases of severe and progressive polyneuropathy, nerve biopsy can assess for the presence of vasculitis, amyloidosis, and paraprotein deposition.

Transverse myelitis

Transverse myelitis is an inflammatory myelopathy that usually presents with acute or subacute weakness of the upper extremities or lower extremities, or both, corresponding to the level of the lesion, hyperreflexia, bladder and bowel dysfunction, spinal level of sensory loss, and autonomic involvement.6 The differential diagnosis of acute myelopathy includes:

- Infection (eg, herpes simplex virus, West Nile virus, Lyme disease, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, human immunodeficiency virus)

- Systemic inflammatory disease (systemic lupus erythematosus, sarcoidosis, Sjögren syndrome, scleroderma, paraneoplastic syndrome)

- Central nervous system demyelinating disease (acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, multiple sclerosis, neuromyelitis optica)

- Vascular malformation (dural arteriovenous fistula)

- Compression due to tumor, bleeding, disc herniation, infection, or abscess.

The workup involves laboratory tests to exclude systemic inflammatory and infectious causes, as well as MRI of the spine with and without contrast to identify a causative lesion. Lumbar puncture and CSF analysis may show pleocytosis, elevated protein concentration, and increased intrathecal immunoglobulin G (IgG) index.7

Although our patient’s presentation with subacute lower-extremity weakness, sensory changes, and bladder dysfunction were consistent with transverse myelitis, her cranial nerve abnormalities would be atypical for it.

Polyradiculopathy

Polyradiculopathy has many possible causes. In the United States, the most common causes are lumbar spondylosis, lumbar canal stenosis, and diabetic polyradiculoneuropathy.

When multiple spinal segments are affected, leptomeningeal disease involving the arachnoid and pia mater should be considered. Causes include malignant invasion, inflammatory cell accumulation, and protein deposition, leading to patchy but widespread dysfunction of spinal nerve roots and cranial nerves. Specific causes are myriad and include carcinomatous meningitis,8 syphilis, tuberculosis, sarcoidosis, and paraproteinemias. CSF and MRI changes are often nonspecific, leading to the need for meningeal biopsy for diagnosis.

CASE CONTINUED

During her hospitalization, our patient developed acute right upper and lower facial weakness consistent with peripheral facial mononeuropathy. Bilateral lower-extremity weakness progressed to disabling paraparesis.

She underwent lumbar puncture and CSF analysis (Table 1). The most notable findings were significant pleocytosis (72% lymphocytic predominance), protein elevation, and elevated IgG index (indicative of elevated intrathecal immunoglobulin synthesis in the central nervous system). Viral, bacterial, and fungal studies were negative. Guillain-Barré syndrome, other polyneuropathies, and spinal cord infarction would not be expected with these CSF features.

Surface EMG demonstrated normal sensory responses, and needle EMG showed chronic and active motor axon loss in the L3 and S1 root distributions, suggesting polyradiculopathy without polyneuropathy. These findings would not be expected in typical acute transverse myelitis but could be seen with spinal cord infarction.

MRI of the entire spine with and without contrast showed cauda equina nerve root thickening and enhancement, especially involving the L5 and S1 roots (Figure 1). The spinal cord appeared normal. These findings further supported polyradiculopathy and a leptomeningeal process.

Further evaluation included chest radiography, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, hemoglobin A1c, human immunodeficiency virus testing, antinuclear antibody, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, extractable nuclear antibody, GQ1b antibody, serum and CSF paraneoplastic panels, levels of vitamin B1, B12, and B6, copper, and ceruloplasmin, and a screen for heavy metals. All results were within normal ranges.

ESTABLISHING THE DIAGNOSIS

Serum monoclonal protein analysis with immunofixation revealed IgM kappa monoclonal gammopathy with an IgM level of 1,570 (reference range 53–334 mg/dL) and M-spike 0.75 (0.00 mg/dL), serum free kappa light chains 61.1 (3.30–19.40 mg/L), lambda 9.3 (5.7–26.3 mg/L), and kappa-lambda ratio 6.57 (0.26–1.65).

2. Which is the best next step in this patient’s neurologic evaluation?

- Test CSF angiotensin-converting enzyme level

- CSF cytology

- Meningeal biopsy

- Peripheral nerve biopsy

Given the high suspicion for malignancy, CSF cytology was performed and showed increased numbers of mononuclear chronic inflammatory cells, including a mixture of lymphocytes and monocytes, favoring a reactive lymphoid pleocytosis. Flow cytometry indicated the presence of a monoclonal, CD5- and CD10- negative, B-cell lymphoproliferative disorder. The immunophenotypic findings were not specific for a single diagnosis. The differential diagnosis included marginal zone lymphoma and lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma.

3. Given the presence of serum IgM monoclonal gammopathy in this patient, which is the most likely diagnosis?

- Neurosarcoidosis

- Multiple myeloma

- Waldenström macroglobulinemia

- Carcinomatous meningitis

Study of bone marrow biopsy demonstrated limited bone marrow involvement (1%) by a lymphoproliferative disorder with plasmacytoid features, and DNA testing detected an MYD88 L265P mutation, reported to be present in 90% of patients with Waldenström macroglobulinemia.9 This finding confirmed the diagnosis of Waldenström macroglobulinemia with central nervous system involvement. Our patient began therapy with rituximab and methotrexate, which resulted in some improvement in strength, gait, and vision.

WALDENSTRÖM MACROGLOBULINEMIA AND BING-NEEL SYNDROME

Waldenström macroglobulinemia is a lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma associated with a monoclonal IgM protein.10 It is considered a paraproteinemic disorder, similar to multiple myeloma. The presenting symptoms and complications are related to direct tumor infiltration, hyperviscosity syndrome, and deposition of IgM in various tissues.11,12

Waldenström macroglobulinemia is usually indolent, and treatment is reserved for patients with symptoms.13,14 It includes rituximab, usually in combination with chemotherapy or other targeted agents.15,16

Paraneoplastic antibody-mediated polyneuropathy may occur in these patients. However, the pattern is usually symmetrical clinically, with demyelination on EMG, and is not associated with cranial nerve or meningeal involvement. Management with plasmapheresis, corticosteroids, and intravenous immunoglobulin has not been shown to be effective.17

Involvement of the central nervous system as a complication of Waldenström macroglobulinemia has been described as Bing-Neel syndrome. It can present as diffuse malignant cell infiltration of the leptomeningeal space, white matter, or spinal cord, or in a tumoral form presenting as intraparenchymal masses or nodular lesions. The distinction between the tumoral and diffuse forms is based primarily on imaging findings.18

In a report of 44 patients with Bing-Neel syndrome, 36% presented with the disorder as the initial manifestation of Waldenström macroglobulinemia.18 The primary presenting symptoms were imbalance and gait difficulty (48%) and cranial nerve involvement (36%), which presented as predominantly facial or oculomotor nerve palsy. Cauda equina syndrome with motor involvement (seen in our patient) occurred in 14% of patients. Other presenting symptoms included cognitive impairment, sensory deficits, headache, dysarthria, aphasia, and seizures.

LEARNING POINTS

The differential diagnosis for patients presenting with multifocal neurologic symptoms can be broad, and a systematic approach to the diagnosis is necessary. Localizing the lesion is important in determining the diagnosis for patients presenting with neurologic symptoms. The process of localization begins with taking the history, is further refined during the examination, and is confirmed with diagnostic studies. Atypical presentations of relatively common neurologic diseases such as Guillain-Barré syndrome, transverse myelitis, and peripheral polyneuropathy do occur, but uncommon diagnoses need to be considered when support for the initial diagnosis is lacking.

A 69-year-old woman was admitted to the hospital with double vision, weakness in the lower extremities, sensory loss, pain, and falls. Her symptoms started with sudden onset of horizontal diplopia 6 weeks before, followed by gradually worsening lower-extremity weakness, as well as ataxia and patchy and bilateral radicular burning leg pain more pronounced on the right. Her medical history included narcolepsy, obstructive sleep apnea, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and bilateral knee replacements for osteoarthritis.

Neurologic examination showed inability to abduct the right eye, bilateral hip flexion weakness, decreased pinprick response, decreased proprioception, and diminished muscle stretch reflexes in the lower extremities. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain without contrast and magnetic resonance angiography of the brain and carotid arteries showed no evidence of acute stroke. No abnormalities were noted on electrocardiography and echocardiography.

A diagnosis of idiopathic peripheral neuropathy was made, and outpatient physical therapy was recommended. Over the subsequent 2 weeks, her condition declined to the point where she needed a walker. She continued to have worsening leg weakness with falls, prompting hospital readmission.

INITIAL EVALUATION

In addition to her diplopia and weakness, she said she had lost 15 pounds since the onset of symptoms and had experienced symptoms suggesting urinary retention.

Physical examination

Her temperature was 37°C (98.6°F), heart rate 79 beats per minute, blood pressure 117/86 mm Hg, respiratory rate 14 breaths per minute, and oxygen saturation 98% on room air. Examination of the head, neck, heart, lung, abdomen, lymph nodes, and extremities yielded nothing remarkable except for chronic venous changes in the lower extremities.

The neurologic examination showed incomplete lateral gaze bilaterally (cranial nerve VI dysfunction). Strength in the upper extremities was normal. In the legs, the Medical Research Council scale score for proximal muscle strength was 2 to 3 out of 5, and for distal muscles 3 to 4 out of 5, with the right side worse than the left and flexors and extensors affected equally. Muscle stretch reflexes were absent in both lower extremities and the left upper extremity, but intact in the right upper extremity. No abnormal corticospinal tract reflexes were elicited.

Sensory testing revealed diminished pin-prick perception in a length-dependent fashion in the lower extremities, reduced 50% compared with the hands. Gait could not be assessed due to weakness.

Initial laboratory testing

Results of initial laboratory tests—complete blood cell count, complete metabolic panel, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, thyroid-stimulating hormone, and hemoglobin A1c—were unremarkable.

FURTHER EVALUATION AND DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

1. Which of the following is the most likely diagnosis at this point?

- Cerebral infarction

- Guillain-Barré syndrome

- Progressive polyneuropathy

- Transverse myelitis

- Polyradiculopathy

In the absence of definitive diagnostic tests, all of the above options were considered in the differential diagnosis for this patient.

Cerebral infarction

Although acute-onset diplopia can be explained by brainstem stroke involving cranial nerve nuclei or their projections, the onset of diplopia with progressive bilateral lower-extremity weakness makes stroke unlikely. Flaccid paralysis, areflexia of the lower extremities, and sensory involvement can also be caused by acute anterior spinal artery occlusion leading to spinal cord infarction; however, the deficits are usually maximal at onset.

Guillain-Barré syndrome

The combination of acute-subacute progressive ascending weakness, sensory involvement, and diminished or absent reflexes is typical of Guillain-Barré syndrome. Cranial nerve involvement can overlap with the more typical features of the syndrome. However, most patients reach the nadir of their disease by 4 weeks after initial symptom onset, even without treatment.1 This patient’s condition continued to worsen over 8 weeks. In addition, the asymmetric lower-extremity weakness and sparing of the arms are atypical for Guillain-Barré syndrome.

Given the progression of symptoms, chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy is also a consideration, typically presenting as a relapsing or progressive neuropathy in proximal and distal muscles and worsening over at least an 8-week period.2

The initial workup for Guillain-Barré syndrome or chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy includes lumbar puncture to assess for albuminocytologic dissociation (elevated protein with normal white blood cell count) in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), and electromyography (EMG) to assess for neurophysiologic evidence of peripheral nerve demyelination. In Miller-Fisher syndrome, a rare variant of Guillain-Barré syndrome characterized by ataxia, ophthalmoparesis, and areflexia, serum ganglioside antibodies to GQ1b are found in over 90% of patients.3,4 Although MRI of the spine is not necessary to diagnose Guillain-Barré syndrome, it is often done to exclude other causes of lower-extremity weakness such as spinal cord or cauda equina compression that would require urgent neurosurgical consultation. MRI can support the diagnosis of Guillain-Barré syndrome when it reveals enhancement of the spinal nerve roots or cauda equina.

Other polyneuropathies

Polyneuropathy is caused by a variety of diseases that affect the function of peripheral motor, sensory, or autonomic nerves. The differential diagnosis is broad and involves inflammatory diseases (including autoimmune and paraneoplastic causes), hereditary disorders, infection, toxicity, and ischemic and nutritional deficiencies.5 Polyneuropathy can present in a distal-predominant, generalized, or asymmetric pattern involving individual nerve trunks termed “mononeuropathy multiplex,” as in our patient’s presentation. The initial workup includes EMG and a battery of serologic tests. In cases of severe and progressive polyneuropathy, nerve biopsy can assess for the presence of vasculitis, amyloidosis, and paraprotein deposition.

Transverse myelitis

Transverse myelitis is an inflammatory myelopathy that usually presents with acute or subacute weakness of the upper extremities or lower extremities, or both, corresponding to the level of the lesion, hyperreflexia, bladder and bowel dysfunction, spinal level of sensory loss, and autonomic involvement.6 The differential diagnosis of acute myelopathy includes:

- Infection (eg, herpes simplex virus, West Nile virus, Lyme disease, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, human immunodeficiency virus)

- Systemic inflammatory disease (systemic lupus erythematosus, sarcoidosis, Sjögren syndrome, scleroderma, paraneoplastic syndrome)

- Central nervous system demyelinating disease (acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, multiple sclerosis, neuromyelitis optica)

- Vascular malformation (dural arteriovenous fistula)

- Compression due to tumor, bleeding, disc herniation, infection, or abscess.

The workup involves laboratory tests to exclude systemic inflammatory and infectious causes, as well as MRI of the spine with and without contrast to identify a causative lesion. Lumbar puncture and CSF analysis may show pleocytosis, elevated protein concentration, and increased intrathecal immunoglobulin G (IgG) index.7

Although our patient’s presentation with subacute lower-extremity weakness, sensory changes, and bladder dysfunction were consistent with transverse myelitis, her cranial nerve abnormalities would be atypical for it.

Polyradiculopathy

Polyradiculopathy has many possible causes. In the United States, the most common causes are lumbar spondylosis, lumbar canal stenosis, and diabetic polyradiculoneuropathy.

When multiple spinal segments are affected, leptomeningeal disease involving the arachnoid and pia mater should be considered. Causes include malignant invasion, inflammatory cell accumulation, and protein deposition, leading to patchy but widespread dysfunction of spinal nerve roots and cranial nerves. Specific causes are myriad and include carcinomatous meningitis,8 syphilis, tuberculosis, sarcoidosis, and paraproteinemias. CSF and MRI changes are often nonspecific, leading to the need for meningeal biopsy for diagnosis.

CASE CONTINUED

During her hospitalization, our patient developed acute right upper and lower facial weakness consistent with peripheral facial mononeuropathy. Bilateral lower-extremity weakness progressed to disabling paraparesis.

She underwent lumbar puncture and CSF analysis (Table 1). The most notable findings were significant pleocytosis (72% lymphocytic predominance), protein elevation, and elevated IgG index (indicative of elevated intrathecal immunoglobulin synthesis in the central nervous system). Viral, bacterial, and fungal studies were negative. Guillain-Barré syndrome, other polyneuropathies, and spinal cord infarction would not be expected with these CSF features.

Surface EMG demonstrated normal sensory responses, and needle EMG showed chronic and active motor axon loss in the L3 and S1 root distributions, suggesting polyradiculopathy without polyneuropathy. These findings would not be expected in typical acute transverse myelitis but could be seen with spinal cord infarction.

MRI of the entire spine with and without contrast showed cauda equina nerve root thickening and enhancement, especially involving the L5 and S1 roots (Figure 1). The spinal cord appeared normal. These findings further supported polyradiculopathy and a leptomeningeal process.

Further evaluation included chest radiography, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, hemoglobin A1c, human immunodeficiency virus testing, antinuclear antibody, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, extractable nuclear antibody, GQ1b antibody, serum and CSF paraneoplastic panels, levels of vitamin B1, B12, and B6, copper, and ceruloplasmin, and a screen for heavy metals. All results were within normal ranges.

ESTABLISHING THE DIAGNOSIS

Serum monoclonal protein analysis with immunofixation revealed IgM kappa monoclonal gammopathy with an IgM level of 1,570 (reference range 53–334 mg/dL) and M-spike 0.75 (0.00 mg/dL), serum free kappa light chains 61.1 (3.30–19.40 mg/L), lambda 9.3 (5.7–26.3 mg/L), and kappa-lambda ratio 6.57 (0.26–1.65).

2. Which is the best next step in this patient’s neurologic evaluation?

- Test CSF angiotensin-converting enzyme level

- CSF cytology

- Meningeal biopsy

- Peripheral nerve biopsy

Given the high suspicion for malignancy, CSF cytology was performed and showed increased numbers of mononuclear chronic inflammatory cells, including a mixture of lymphocytes and monocytes, favoring a reactive lymphoid pleocytosis. Flow cytometry indicated the presence of a monoclonal, CD5- and CD10- negative, B-cell lymphoproliferative disorder. The immunophenotypic findings were not specific for a single diagnosis. The differential diagnosis included marginal zone lymphoma and lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma.

3. Given the presence of serum IgM monoclonal gammopathy in this patient, which is the most likely diagnosis?

- Neurosarcoidosis

- Multiple myeloma

- Waldenström macroglobulinemia

- Carcinomatous meningitis

Study of bone marrow biopsy demonstrated limited bone marrow involvement (1%) by a lymphoproliferative disorder with plasmacytoid features, and DNA testing detected an MYD88 L265P mutation, reported to be present in 90% of patients with Waldenström macroglobulinemia.9 This finding confirmed the diagnosis of Waldenström macroglobulinemia with central nervous system involvement. Our patient began therapy with rituximab and methotrexate, which resulted in some improvement in strength, gait, and vision.

WALDENSTRÖM MACROGLOBULINEMIA AND BING-NEEL SYNDROME

Waldenström macroglobulinemia is a lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma associated with a monoclonal IgM protein.10 It is considered a paraproteinemic disorder, similar to multiple myeloma. The presenting symptoms and complications are related to direct tumor infiltration, hyperviscosity syndrome, and deposition of IgM in various tissues.11,12

Waldenström macroglobulinemia is usually indolent, and treatment is reserved for patients with symptoms.13,14 It includes rituximab, usually in combination with chemotherapy or other targeted agents.15,16

Paraneoplastic antibody-mediated polyneuropathy may occur in these patients. However, the pattern is usually symmetrical clinically, with demyelination on EMG, and is not associated with cranial nerve or meningeal involvement. Management with plasmapheresis, corticosteroids, and intravenous immunoglobulin has not been shown to be effective.17

Involvement of the central nervous system as a complication of Waldenström macroglobulinemia has been described as Bing-Neel syndrome. It can present as diffuse malignant cell infiltration of the leptomeningeal space, white matter, or spinal cord, or in a tumoral form presenting as intraparenchymal masses or nodular lesions. The distinction between the tumoral and diffuse forms is based primarily on imaging findings.18

In a report of 44 patients with Bing-Neel syndrome, 36% presented with the disorder as the initial manifestation of Waldenström macroglobulinemia.18 The primary presenting symptoms were imbalance and gait difficulty (48%) and cranial nerve involvement (36%), which presented as predominantly facial or oculomotor nerve palsy. Cauda equina syndrome with motor involvement (seen in our patient) occurred in 14% of patients. Other presenting symptoms included cognitive impairment, sensory deficits, headache, dysarthria, aphasia, and seizures.

LEARNING POINTS

The differential diagnosis for patients presenting with multifocal neurologic symptoms can be broad, and a systematic approach to the diagnosis is necessary. Localizing the lesion is important in determining the diagnosis for patients presenting with neurologic symptoms. The process of localization begins with taking the history, is further refined during the examination, and is confirmed with diagnostic studies. Atypical presentations of relatively common neurologic diseases such as Guillain-Barré syndrome, transverse myelitis, and peripheral polyneuropathy do occur, but uncommon diagnoses need to be considered when support for the initial diagnosis is lacking.

- Fokke C, van den Berg B, Drenthen J, Walgaard C, van Doorn PA, Jacobs BC. Diagnosis of Guillain-Barre syndrome and validation of Brighton criteria. Brain 2014; 137(Pt 1):33–43. doi:10.1093/brain/awt285

- Mathey EK, Park SB, Hughes RA, et al. Chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy: from pathology to phenotype. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2015; 86(9):973–985. doi:10.1136/jnnp-2014-309697

- Chiba A, Kusunoki S, Obata H, Machinami R, Kanazawa I. Serum anti-GQ1b IgG antibody is associated with ophthalmoplegia in Miller Fisher syndrome and Guillain-Barré syndrome: clinical and immunohistochemical studies. Neurology 1993; 43(10):1911–1917. pmid:8413947

- Teener J. Miller Fisher’s syndrome. Semin Neurol 2012; 32(5):512–516. doi:10.1055/s-0033-1334470

- Watson JC, Dyck PJ. Peripheral neuropathy: a practical approach to diagnosis and symptom management. Mayo Clin Proc 2015; 90(7):940–951. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.05.004

- Greenberg BM. Treatment of acute transverse myelitis and its early complications. Continuum (Minneap Minn) 2011; 17(4):733–743. doi:10.1212/01.CON.0000403792.36161.f5

- West TW. Transverse myelitis—a review of the presentation, diagnosis, and initial management. Discov Med 2013; 16(88):167–177. pmid:24099672

- Le Rhun E, Taillibert S, Chamberlain MC. Carcinomatous meningitis: leptomeningeal metastases in solid tumors. Surg Neurol Int 2013; 4(suppl 4):S265–S288. doi:10.4103/2152-7806.111304

- Treon SP, Xu L, Yang G, et al. MYD88 L265P somatic mutation in Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia. N Engl J Med 2012; 367(9):826–833. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1200710

- Owen RG, Treon SP, Al-Katib A, et al. Clinicopathological definition of Waldenstrom’s macroglobulinemia: consensus panel recommendations from the Second International Workshop on Waldenstrom’s Macroglobulinemia. Semin Oncol 2003; 30(2):110–115. doi:10.1053/sonc.2003.50082

- Björkholm M, Johansson E, Papamichael D, et al. Patterns of clinical presentation, treatment, and outcome in patients with Waldenstrom’s macroglobulinemia: a two-institution study. Semin Oncol 2003; 30(2):226–230. doi:10.1053/sonc.2003.50054

- Rison RA, Beydoun SR. Paraproteinemic neuropathy: a practical review. BMC Neurol 2016; 16:13. doi:10.1186/s12883-016-0532-4

- Kyle RA, Benson J, Larson D, et al. IgM monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance and smoldering Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma 2009; 9(1):17–18. doi:10.3816/CLM.2009.n.002

- Kyle RA, Benson JT, Larson DR, et al. Progression in smoldering Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia: long-term results. Blood 2012; 119(19):4462–4466. doi:10.1182/blood-2011-10-384768

- Leblond V, Kastritis E, Advani R, et al. Treatment recommendations from the Eighth International Workshop on Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia. Blood 2016; 128(10):1321–1328. doi:10.1182/blood-2016-04-711234

- Kapoor P, Ansell SM, Fonseca R, et al. Diagnosis and management of Waldenström macroglobulinemia: Mayo stratification of macroglobulinemia and risk-adapted therapy (mSMART) guidelines 2016. JAMA Oncol 2017; 3(9):1257–1265. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.5763

- D’Sa S, Kersten MJ, Castillo JJ, et al. Investigation and management of IgM and Waldenström-associated peripheral neuropathies: recommendations from the IWWM-8 consensus panel. Br J Haematol 2017; 176(5):728–742. doi:10.1111/bjh.14492

- Simon L, Fitsiori A, Lemal R, et al. Bing-Neel syndrome, a rare complication of Waldenström macroglobulinemia: analysis of 44 cases and review of the literature. A study on behalf of the French Innovative Leukemia Organization (FILO). Haematologica 2015; 100(12):1587–1594. doi:10.3324/haematol.2015.133744

- Fokke C, van den Berg B, Drenthen J, Walgaard C, van Doorn PA, Jacobs BC. Diagnosis of Guillain-Barre syndrome and validation of Brighton criteria. Brain 2014; 137(Pt 1):33–43. doi:10.1093/brain/awt285

- Mathey EK, Park SB, Hughes RA, et al. Chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy: from pathology to phenotype. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2015; 86(9):973–985. doi:10.1136/jnnp-2014-309697

- Chiba A, Kusunoki S, Obata H, Machinami R, Kanazawa I. Serum anti-GQ1b IgG antibody is associated with ophthalmoplegia in Miller Fisher syndrome and Guillain-Barré syndrome: clinical and immunohistochemical studies. Neurology 1993; 43(10):1911–1917. pmid:8413947

- Teener J. Miller Fisher’s syndrome. Semin Neurol 2012; 32(5):512–516. doi:10.1055/s-0033-1334470

- Watson JC, Dyck PJ. Peripheral neuropathy: a practical approach to diagnosis and symptom management. Mayo Clin Proc 2015; 90(7):940–951. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.05.004

- Greenberg BM. Treatment of acute transverse myelitis and its early complications. Continuum (Minneap Minn) 2011; 17(4):733–743. doi:10.1212/01.CON.0000403792.36161.f5

- West TW. Transverse myelitis—a review of the presentation, diagnosis, and initial management. Discov Med 2013; 16(88):167–177. pmid:24099672

- Le Rhun E, Taillibert S, Chamberlain MC. Carcinomatous meningitis: leptomeningeal metastases in solid tumors. Surg Neurol Int 2013; 4(suppl 4):S265–S288. doi:10.4103/2152-7806.111304

- Treon SP, Xu L, Yang G, et al. MYD88 L265P somatic mutation in Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia. N Engl J Med 2012; 367(9):826–833. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1200710

- Owen RG, Treon SP, Al-Katib A, et al. Clinicopathological definition of Waldenstrom’s macroglobulinemia: consensus panel recommendations from the Second International Workshop on Waldenstrom’s Macroglobulinemia. Semin Oncol 2003; 30(2):110–115. doi:10.1053/sonc.2003.50082

- Björkholm M, Johansson E, Papamichael D, et al. Patterns of clinical presentation, treatment, and outcome in patients with Waldenstrom’s macroglobulinemia: a two-institution study. Semin Oncol 2003; 30(2):226–230. doi:10.1053/sonc.2003.50054

- Rison RA, Beydoun SR. Paraproteinemic neuropathy: a practical review. BMC Neurol 2016; 16:13. doi:10.1186/s12883-016-0532-4

- Kyle RA, Benson J, Larson D, et al. IgM monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance and smoldering Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma 2009; 9(1):17–18. doi:10.3816/CLM.2009.n.002

- Kyle RA, Benson JT, Larson DR, et al. Progression in smoldering Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia: long-term results. Blood 2012; 119(19):4462–4466. doi:10.1182/blood-2011-10-384768

- Leblond V, Kastritis E, Advani R, et al. Treatment recommendations from the Eighth International Workshop on Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia. Blood 2016; 128(10):1321–1328. doi:10.1182/blood-2016-04-711234

- Kapoor P, Ansell SM, Fonseca R, et al. Diagnosis and management of Waldenström macroglobulinemia: Mayo stratification of macroglobulinemia and risk-adapted therapy (mSMART) guidelines 2016. JAMA Oncol 2017; 3(9):1257–1265. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.5763

- D’Sa S, Kersten MJ, Castillo JJ, et al. Investigation and management of IgM and Waldenström-associated peripheral neuropathies: recommendations from the IWWM-8 consensus panel. Br J Haematol 2017; 176(5):728–742. doi:10.1111/bjh.14492

- Simon L, Fitsiori A, Lemal R, et al. Bing-Neel syndrome, a rare complication of Waldenström macroglobulinemia: analysis of 44 cases and review of the literature. A study on behalf of the French Innovative Leukemia Organization (FILO). Haematologica 2015; 100(12):1587–1594. doi:10.3324/haematol.2015.133744

Bell palsy: Clinical examination and management

Bell palsy is an idiopathic peripheral nerve disorder involving the facial nerve (ie, cranial nerve VII) and manifesting as acute, ipsilateral facial muscle weakness. It is named after Sir Charles Bell, who in 1821 first described the anatomy of the facial nerve.1 Although the disorder is clinically benign, patients can be devastated by its disfigurement.

The annual incidence of Bell palsy is 20 per 100,000, with no predilection for sex or ethnicity. It can affect people at any age, but the incidence is slightly higher after age 40.2,3 Risk factors include diabetes, pregnancy, severe preeclampsia, obesity, and hypertension.4–7

THE FACIAL NERVE IS VULNERABLE TO TRAUMA AND COMPRESSION

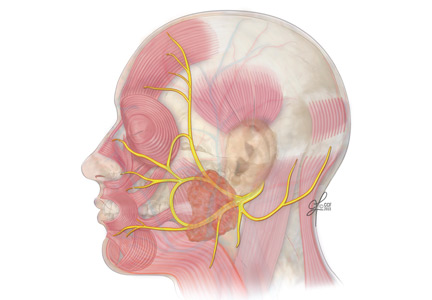

A basic understanding of the neuroanatomy of the facial nerve provides clues for distinguishing a central lesion from a peripheral lesion. This differentiation is important because the causes and management differ.

The facial nerve is a mixed sensory and motor nerve, carrying fibers involved in facial expression, taste, lacrimation, salivation, and sensation of the ear. It originates in the lower pons and exits the brainstem ventrally at the pontomedullary junction. After entering the internal acoustic meatus, it travels 20 to 30 mm in the facial canal, the longest bony course of any cranial nerve, making it highly susceptible to trauma and compression by edema.8

In the facial canal, it makes a posterior and inferior turn, forming a bend (ie, the genu of the facial nerve). The genu is proximal to the geniculate ganglion, which contains the facial nerve’s primary sensory neurons for taste and sensation. The motor branch of the facial nerve then exits the cranium via the stylomastoid foramen and passes through the parotid gland, where it divides into temporofacial and cervicofacial trunks.9

The facial nerve has five terminal branches that innervate the muscles of facial expression:

- The temporal branch (muscles of the forehead and superior part of the orbicularis oculi)

- The zygomatic branch (muscles of the nasolabial fold and cheek, eg, nasalis and zygomaticus).

- The buccal branch (the buccinators and inferior part of the orbicularis oculi)

- The marginal mandibular branch (the depressors of the mouth, eg, depressor anguli and mentalis)

- The cervical branch (the platysma muscle).

INFLAMMATION IS BELIEVED TO BE RESPONSIBLE

Although the precise cause of Bell palsy is not known, one theory is that inflammation of the nerve causes focal edema, demyelination, and ischemia. Several studies have suggested that herpes virus simplex type 1 infection may be involved.10

FACIAL DROOPING, EYELID WEAKNESS, OTHER SYMPTOMS

Symptoms of Bell palsy include ipsilateral sagging of the eyebrow, drooping of the face, flattening of the nasolabial fold, and inability to fully close the eye, pucker the lips, or raise the corner of the mouth (Figure 1). Symptoms develop within hours and are maximal by 3 days.

About 70% of patients have associated ipsilateral pain around the ear. If facial pain is present with sensory and hearing loss, a tumor of the parotid gland or viral otitis must be considered.11 Other complaints may include hyperacusis due to disruption of nerve fibers to the stapedius muscle, changes in taste, and dry eye from parasympathetic dysfunction. Some patients report paresthesias over the face, which most often represent motor symptoms misconstrued as sensory changes.

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

The clinical examination should include a complete neurologic and general examination, including otoscopy and attention to the skin and parotid gland. Vesicles or scabbing around the ear should prompt testing for herpes zoster. Careful observation during the interview while the patient is talking may reveal subtle signs of weakness and provide additional clues.

A systematic approach to the assessment of a patient with suspected Bell palsy is recommended (Table 1) and outlined below:

Does the patient have peripheral facial palsy?

In Bell palsy, wrinkling of the forehead on the affected side when raising the eyebrows is either asymmetrical or absent.

If the forehead muscles are spared and the lower face is weak, this signifies a central lesion such as a stroke or other structural abnormality and not a peripheral lesion of the facial nerve (eg, Bell palsy).

Can the patient close the eyes tightly?

Normally, the patient should be able to close both eyes tightly, and the eyelashes should be buried between the eyelids. In Bell palsy, when the patient attempts to close the eyes, the affected side shows incomplete closure and the eye may remain partly open.

Assess the strength of the orbicularis oculi by trying to open the eyes. The patient who is attempting to close the eyelids tightly but cannot will demonstrate the Bell phenomenon, ie, the examiner is able to force open the eyelids, and the eyes are deviated upward and laterally.

Closely observe the blink pattern, as the involved side in Bell palsy may slightly lag behind the normal eye, and the patient may be unable to close the eye completely.

Is the smile symmetric?

Note flattening of the nasolabial fold on one side, which indicates facial weakness.

Can the patient puff out the cheeks?

Ask the patient to hold air in the mouth against resistance. This assesses the strength of the buccinator muscle.

Can the patient purse the lips?

Ask the patient to pucker or purse the lips and observe for asymmetry or weakness on the affected side.

Test the orbicularis oris muscle by trying to spread the lips apart while the patient resists, and observe for weakness on one side.

Is there a symmetric grimace?

This will test the muscles involved in depressing the angles of the mouth and platysma.

Are taste, sensation, and hearing intact?

Other testable functions of the facial nerve, including taste, sensation, and hearing, do not always need to be assessed but can be in patients with specific sensory deficits.

Abnormalities in taste can support localization of the problem either proximal or distal to the branch point of fibers mediating taste. The facial nerve supplies taste fibers to the anterior two-thirds of the tongue. Sweet and salty taste can be screened with sugar and salt. Tell the patient to close the eyes, and using a tongue blade, apply a small amount of sugar or salt on the side of the tongue. Ask the patient to identify the taste and repeat with the other sample after he or she has rinsed the mouth.

Somatic sensory fibers supplied by the facial nerve innervate the inner ear and a small area behind the ear, but these may be difficult to assess objectively. Formal audiologic testing may be needed if hearing is impaired.

Facial nerve reflexes

A number of facial reflexes can be tested, including the orbicularis oculi, palpebral-oculogyric, and corneal reflexes.12

The orbicularis oculi reflex is tested by gentle finger percussion of the glabella while observing for involuntary blinking with each stimulus. The afferent branch of this reflex is carried by the trigeminal nerve, while the efferent response is carried by the facial nerve. In peripheral facial nerve palsy, this reflex is weakened or absent on the affected side.

The palpebral-oculogyric reflex, or Bell phenomenon, produces upward and lateral deviation of the eyes when attempting forceful eyelid closure. In this reflex, the afferent fibers are carried by the facial nerve and the efferent fibers travel in the oculomotor nerve to the superior rectus muscle. In Bell palsy, this reflex is visible because of failure of adequate eyelid closure.

The corneal reflex is elicited by stimulating the cornea with a wisp of cotton, causing reflexive closure of the both eyes. The affected side may show slowed or absent lid closure when tested on either side. The sensory afferent fibers are carried by the trigeminal nerve, and the motor efferent fibers are carried by the facial nerve.

Grading of facial paralysis

The House-Brackmann scale is the most widely used tool for grading the degree of facial paralysis and for predicting recovery. Grades are I to VI, with grade I indicating normal function, and grade VI, complete paralysis.

Patients with some preserved motor function generally have good recovery, but those with complete paralysis may have long-term residual deficits.13

A DIAGNOSIS OF EXCLUSION

The diagnosis of Bell palsy is made by excluding other causes of unilateral facial paralysis, and 30% to 60% of cases of facial palsy are caused by an underlying disorder that mimics Bell palsy, including central nervous system lesion (eg, stroke, demyelinating disease), parotid gland tumor, Lyme disease, Ramsay Hunt syndrome, granulomatous disease, otitis media, cholesteatoma, diabetes, trauma, and Guillain-Barré syndrome (Table 2).14,15 Many of these conditions have associated features that help distinguish them from Bell palsy. Facial palsy that does not improve after 3 weeks should prompt referral to a neurologist.

Brain lesions

It is uncommon to have isolated facial palsy with a cortical or subcortical brain lesion, since the corticobulbar and corticospinal tracts travel in close proximity. Cortical signs such as hemiparesis, hemisensory loss, neglect, and dysarthria suggest a lesion of the cerebral cortex. Additionally, forehead muscle sparing is expected in supranuclear lesions.

Brainstem lesions can manifest with multiple ipsilateral cranial nerve palsies and contralateral limb weakness. Sarcoidosis and leptomeningeal carcinomatosis tend to involve the skull base and present with multiple cranial neuropathies.

Tumors of the brain or parotid gland have an insidious onset and may cause systemic signs such as fevers, chills, and weight loss. Headache, seizures, and hearing loss indicate an intracranial lesion. A palpable mass near the ear, neck, or parotid gland requires imaging of the face to look for a parotid gland tumor.

Infection

A number of infections can cause acute facial paralysis. The most common is herpes simplex virus, and the next most common is varicella zoster.14 Herpes simplex virus, Ramsay Hunt syndrome, and Lyme disease may have associated pain and skin changes. Erythema of the tympanic membrane suggests otitis media, especially in the setting of ear pain and hearing loss.

Ramsay Hunt syndrome is caused by reactivation of the herpes zoster virus from the geniculate ganglion, affecting the facial nerve. Careful examination of the ear canal and the oropharynx may show vesicles.

In Lyme disease, facial palsy is the most common cranial neuropathy, seen in 50% to 63% of patients with Borrelia burgdorferi meningitis.16,17 In people with a history of rash, arthralgia, tick bite, or travel to an endemic region, Lyme titers should be checked before starting the patient on corticosteroids.

Bilateral facial palsy is rare and occurs in fewer than 1% of patients. It has been reported in patients with Lyme disease, Guillain-Barré syndrome, sarcoidosis, diabetes mellitus, viral infection, and pontine glioma.18

DIAGNOSTIC EVALUATION

Serologic testing, electrodiagnostic studies, and imaging are not routinely necessary to diagnose Bell palsy. However, referral to the appropriate specialist (neurologist, otolaryngologist, optometrist, ophthalmologist) is advised if the patient has sparing of the forehead muscle, multiple cranial neuropathies, signs of infection, or persistent weakness without significant improvement at 3 weeks.

Laboratory testing

A complete blood cell count with differential may point to infection or a lymphoproliferative disorder. When indicated, screening for diabetes mellitus with fasting blood glucose or hemoglobin A1c may be helpful. In Lyme-endemic regions, patients should undergo an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay or an indirect fluorescent antibody test to screen for the disease. If positive, the diagnosis of Lyme disease should be confirmed by Western blot. If vesicles are present on examination, check serum antibodies for herpes zoster. In the appropriate clinical setting, angiotensin-converting enzyme, human immunodeficiency virus, and inflammatory markers can be tested.

Cerebrospinal fluid analysis is generally not helpful in diagnosing Bell palsy but can differentiate it from Guillain-Barré syndrome, leptomeningeal carcinomatosis, and infection involving the central nervous system.

Imaging

Imaging is not recommended in the initial evaluation of Bell palsy unless symptoms and the examination are atypical. From 5% to 7% of cases of facial palsy are caused by a tumor (eg, facial neuroma, cholesteatoma, hemangioma, meningioma), whether benign or malignant.14,15 Therefore, in patients with insidious onset of symptoms that do not improve in about 3 weeks, contrast-enhanced computed tomography or gadolinium-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging of the internal auditory canal and face is warranted.

Electrodiagnostic studies

Electrodiagnostic testing is typically not part of the evaluation of acute Bell palsy, but in patients with complete paralysis, it may help assess the degree of nerve injury and the chances of recovery, especially since patients with complete paralysis have a higher risk of incomplete recovery.19 Electrodiagnostic studies should be performed at least 1 week after symptom onset to avoid false-negative results.

TREATMENT

The treatment of Bell palsy focuses on maximizing recovery and minimizing associated complications.

Protect the eyes

Patients who cannot completely close their eyes should be given instructions on ocular protective care to prevent exposure keratopathy. Frequent application of lubricant eyedrops with artificial tears during the day or ophthalmic ointment at bedtime is recommended. The physician should also recommend protective eyewear such as sunglasses during the day. Eye patching or taping at night may be useful but could be harmful if applied too loosely or too tightly. Patients with vision loss or eye irritation should be referred to an ophthalmologist.19

Corticosteroids are recommended in the first 72 hours

In two randomized clinical trials (conducted by Sullivan et al20 in 511 patients and Engström et al21 in 829 patients), prednisolone was found to be beneficial if started within 72 hours of symptom onset.

In a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study of prednisone in 58 patients, those who received the drug recovered faster, although long-term outcomes in these patients were not significantly different than those in the control group.22 The American Academy of Neurology23 rated this study as class II, ie, not meeting all of its criteria for the highest level of evidence, class I. Nevertheless, although prednisone lacks class I evidence, its use is recommended because it is a precursor to its active metabolite, prednisolone, which has been studied extensively.

The current guidelines of the American Academy of Neurology, updated in 2012, state, “For patients with new-onset Bell palsy, steroids are highly likely to be effective and should be offered to increase the probability of recovery of facial nerve function”23 (level A evidence, ie, established as effective). They also concluded that adverse effects of corticosteroids were generally minor and temporary.

Similarly, the guidelines of the American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery, published in 2013, recommend oral corticosteroids within 72 hours of onset of symptoms of Bell palsy for patients age 16 and older.19 The recommendation is for a 10-day course of corticosteroids with at least 5 days at a high dose (prednisolone 50 mg orally daily for 10 days, or prednisone 60 mg orally daily for 5 days, followed by a 5-day taper). The benefit of corticosteroids after 72 hours is unclear (Table 3).19

Even though the guidelines recommend corticosteroids, the decision to use them in diabetic patients and pregnant women should be individualized. Discretion is advised, as not all patients with Bell palsy need to be treated. Most recover spontaneously, especially those with mild symptoms.

Antiviral therapy may offer modest benefit

Antiviral therapy has not been shown to be beneficial in Bell palsy, and current guidelines do not recommend oral antiviral therapy alone.19 However, an antiviral combined with a corticosteroid may offer modest benefit if started within 72 hours of symptom onset (level C evidence, ie, possibly effective).23 Patients starting antiviral therapy should understand that its benefit has not been established.

Surgical decompression remains controversial

A Cochrane systematic review in 2011 found insufficient evidence regarding the safety and efficacy of surgical intervention in Bell palsy.24 Surgery should be considered only for patients with complete paralysis with a greater than 90% reduction in motor amplitude on a nerve conduction study compared with the unaffected side, and absent volitional activity on needle examination.19,25

Acupuncture: No recommendation

Currently, there is no recommendation for acupuncture in the treatment of Bell palsy.19 A recent randomized clinical trial suggests benefit from acupuncture combined with corticosteroids,26 but high-quality studies to support its use are lacking.26

Physical therapy: Insufficient evidence

There is insufficient evidence to show that physical therapy has benefit—or harm—in Bell palsy. However, some low-quality studies indicated that facial exercises and mime therapy may improve function in patients with moderate paralysis.27

Follow-up

Patients should be instructed to call at 2 weeks to report progress of symptoms and to be reevaluated within or at 1 month, with close attention to facial weakness and eye irritation. Further evaluation is needed if there has been no improvement, if symptoms have worsened, or if new symptoms have appeared.

The psychosocial impact of Bell palsy cannot be discounted, as the disfigurement can have negative implications for self-esteem and social relationships. Appropriate referral to an ophthalmologist, neurologist, otolaryngologist, social worker, or a plastic surgeon may be necessary.

COMPLICATIONS AND PROGNOSIS

Most patients with Bell palsy recover completely, but up to 30% have residual symptoms at 6 months.14,20 Furthermore, although Bell palsy usually has a monophasic course, 7% to 12% of patients have a recurrence.3,15

Long-term complications can include residual facial weakness, facial synkinesis, facial contracture, and facial spasm.14,28 Incomplete eye closure may benefit from surgery (tarsorrhaphy or gold-weight implantation) to prevent corneal ulceration. Facial synkinesis is due to aberrant nerve regeneration and occurs in 15% to 20% of patients after recovery from Bell palsy.29 Patients may describe tearing while chewing (“crocodile tears”), involuntary movement of the corners of the mouth with blinking, or ipsilateral eye-closing when the jaw opens (“jaw-winking”). Facial contracture, facial synkinesis, and facial spasm can be treated with botulinum toxin injection.30

- Grzybowski A, Kaufman MH. Sir Charles Bell (1774-1842): contributions to neuro-ophthalmology. Acta Ophthalmol Scand 2007; 85:897–901.

- De Diego-Sastre JI, Prim-Espada MP, Fernández-García F. The epidemiology of Bell’s palsy. Rev Neurol 2005; 41:287–290. In Spanish.

- Morris AM, Deeks SL, Hill MD, et al. Annualized incidence and spectrum of illness from an outbreak investigation of Bell’s palsy. Neuroepidemiology 2002; 21:255–261.

- Bosco D, Plastino M, Bosco F, et al. Bell’s palsy: a manifestation of prediabetes? Acta Neurol Scand 2011; 123:68–72.

- Riga M, Kefalidis G, Danielides V. The role of diabetes mellitus in the clinical presentation and prognosis of Bell palsy. J Am Board Fam Med 2012; 25:819–826.

- Hilsinger RL Jr, Adour KK, Doty HE. Idiopathic facial paralysis, pregnancy, and the menstrual cycle. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 1975; 84:433–442.

- Savadi-Oskouei D, Abedi A, Sadeghi-Bazargani H. Independent role of hypertension in Bell’s palsy: a case-control study. Eur Neurol 2008; 60:253–257.

- Murai A, Kariya S, Tamura K, et al. The facial nerve canal in patients with Bell’s palsy: an investigation by high-resolution computed tomography with multiplanar reconstruction. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2013; 270:2035–2038.

- Blumenfeld H. Neuroanatomy Through Clinical Cases. 1st ed. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer; 2002:479–484.

- Murakami S, Mizobuchi M, Nakashiro Y, Doi T, Hato N, Yanagihara N. Bell palsy and herpes simplex virus: identification of viral DNA in endoneurial fluid and muscle. Ann Intern Med 1996; 124:27–30.

- Boahene DO, Olsen KD, Driscoll C, Lewis JE, McDonald TJ. Facial nerve paralysis secondary to occult malignant neoplasms. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2004; 130:459–465.

- DeJong RN. The Neurologic Examination: Incorporating the fundamentals of neuroanatomy and neurophysiology. 4th ed. New York, NY: Harper & Row; 1979:178–198.

- House JW, Brackmann DE. Facial nerve grading system. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1985; 93:146–147.

- Peitersen E. Bell’s palsy: the spontaneous course of 2,500 peripheral facial nerve palsies of different etiologies. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl 2002; 549:4–30.

- Hohman MH, Hadlock TA. Etiology, diagnosis, and management of facial palsy: 2000 patients at a facial nerve center. Laryngoscope 2014; 124:E283–E293.

- Ackermann R, Hörstrup P, Schmidt R. Tick-borne meningopolyneuritis (Garin-Bujadoux, Bannwarth). Yale J Biol Med 1984; 57:485–490.

- Pachner AR, Steere AC. The triad of neurologic manifestations of Lyme disease: meningitis, cranial neuritis, and radiculoneuritis. Neurology 1985; 35:47–53.

- Keane JR. Bilateral seventh nerve palsy: analysis of 43 cases and review of the literature. Neurology 1994; 44:1198–1202.

- Baugh RF, Basura GJ, Ishii LE, et al. Clinical practice guideline: Bell’s palsy. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2013; 149(suppl 3):S1–S27.

- Sullivan FM, Swan IR, Donnan PT, et al. Early treatment with prednisolone or acyclovir in Bell’s palsy. N Engl J Med 2007; 357:1598–1607.

- Engström M, Berg T, Stjernquist-Desatnik A, et al. Prednisolone and valaciclovir in Bell’s palsy: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial. Lancet Neurol 2008; 7:993–1000.

- Lagalla G, Logullo F, Di Bella P, Provinciali L, Ceravolo MG. Influence of early high-dose steroid treatment on Bell’s palsy evolution. Neurol Sci 2002; 23:107–112.

- Gronseth GS, Paduga R; American Academy of Neurology. Evidence-based guideline update: steroids and antivirals for Bell palsy: report of the Guideline Development Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology 2012; 79:2209–2213.

- McAllister K, Walker D, Donnan PT, Swan I. Surgical interventions for the early management of Bell’s palsy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011; 2:CD007468.

- Gantz BJ, Rubinstein JT, Gidley P, Woodworth GG. Surgical management of Bell’s palsy. Laryngoscope 1999; 109:1177–1188.

- Xu SB, Huang B, Zhang CY, et al. Effectiveness of strengthened stimulation during acupuncture for the treatment of Bell palsy: a randomized controlled trial. CMAJ 2013; 185:473–479.

- Teixeira LJ, Valbuza JS, Prado GF. Physical therapy for Bell’s palsy (idiopathic facial paralysis). Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011; 12:CD006283.

- Yaltho TC, Jankovic J. The many faces of hemifacial spasm: differential diagnosis of unilateral facial spasms. Mov Disord 2011; 26:1582–1592.

- Celik M, Forta H, Vural C. The development of synkinesis after facial nerve paralysis. Eur Neurol 2000; 43:147–151.

- Chua CN, Quhill F, Jones E, Voon LW, Ahad M, Rowson N. Treatment of aberrant facial nerve regeneration with botulinum toxin A. Orbit 2004; 23:213–218.