User login

Top pregnancy apps for your patients

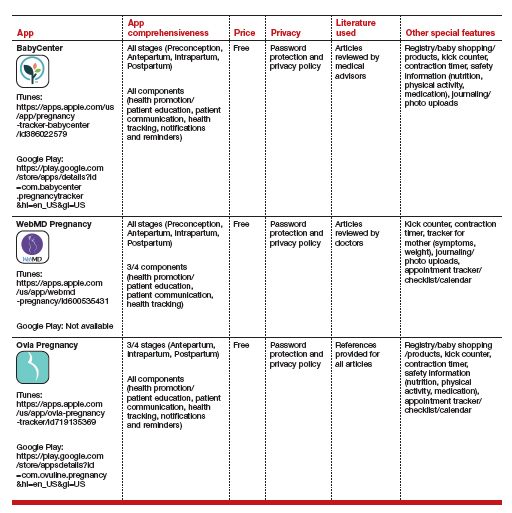

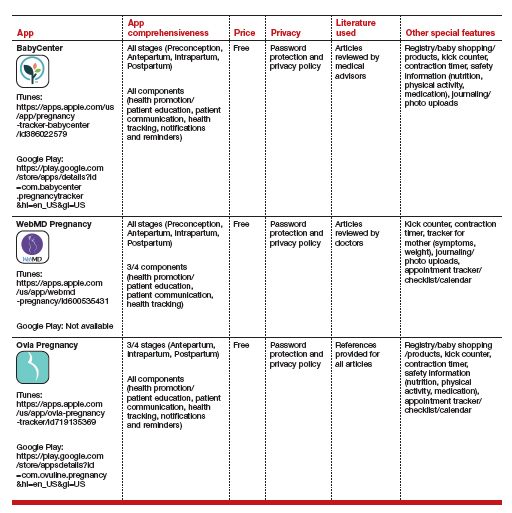

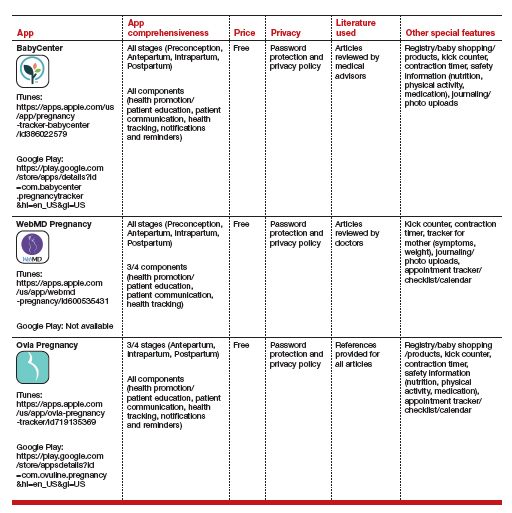

Pregnancy apps are more popular as patients use the internet to seek information about pregnancy and childbirth.1 Research has shown that over 50% of pregnant patients download apps focused on pregnancy, with an average of 3 being tried.2 This is especially true during the COVID-19 pandemic, when patients seek information but may want to minimize clinical exposures. Other research has shown that women primarily use apps to monitor fetal development and to obtain information on nutrition and antenatal care.3

We identified apps and rated their contents and features.4 To identify the apps, we performed a Google search to mimic what a patient may do. We scored the identified apps based on what has been shown to make apps successful, as well as desired functions of the most commonly used apps. The quality of the applications was relatively varied, with many of the apps (60%) not having comprehensive information for every stage of pregnancy and no app attaining a perfect score. However, the top 3 apps had near perfect scores of 15/16 and 14/16, missing points only for having advertisements and requiring an internet connection.

The table details these top 3 recommended pregnancy apps, along with a detailed shortened version of the APPLICATIONS scoring system, APPLI (App comprehensiveness, Price, Platform, Literature Used, Other special features). We hope this column will help you feel comfortable in helping patients use pregnancy apps, should they ask for recommendations.

1. Romano AM. A changing landscape: implications of pregnant women’s internet use for childbirth educators. J Perinat Educ. 2007;16:18-24. doi: 10.1624/105812407X244903.

2. Jayaseelan R, Pichandy C, Rushandramani D. Usage of smartphone apps by women on their maternal life. J Mass Communicat Journalism. 2015;29:05:158-164. doi: 10.4172/2165-7912.1000267.

3. Wang N, Deng Z, Wen LM, et al. Understanding the use of smartphone apps for health information among pregnant Chinese women: mixed methods study. JMIR mHealth uHealth. 2019;18:7:e12631. doi: 10.2196/12631.

4. Frid G, Bogaert K, Chen KT. Mobile health apps for pregnant women: systematic search, evaluation, and analysis of features. J Med Internet Res. 2021;18:23:e25667. doi: 10.2196/25667.

Pregnancy apps are more popular as patients use the internet to seek information about pregnancy and childbirth.1 Research has shown that over 50% of pregnant patients download apps focused on pregnancy, with an average of 3 being tried.2 This is especially true during the COVID-19 pandemic, when patients seek information but may want to minimize clinical exposures. Other research has shown that women primarily use apps to monitor fetal development and to obtain information on nutrition and antenatal care.3

We identified apps and rated their contents and features.4 To identify the apps, we performed a Google search to mimic what a patient may do. We scored the identified apps based on what has been shown to make apps successful, as well as desired functions of the most commonly used apps. The quality of the applications was relatively varied, with many of the apps (60%) not having comprehensive information for every stage of pregnancy and no app attaining a perfect score. However, the top 3 apps had near perfect scores of 15/16 and 14/16, missing points only for having advertisements and requiring an internet connection.

The table details these top 3 recommended pregnancy apps, along with a detailed shortened version of the APPLICATIONS scoring system, APPLI (App comprehensiveness, Price, Platform, Literature Used, Other special features). We hope this column will help you feel comfortable in helping patients use pregnancy apps, should they ask for recommendations.

Pregnancy apps are more popular as patients use the internet to seek information about pregnancy and childbirth.1 Research has shown that over 50% of pregnant patients download apps focused on pregnancy, with an average of 3 being tried.2 This is especially true during the COVID-19 pandemic, when patients seek information but may want to minimize clinical exposures. Other research has shown that women primarily use apps to monitor fetal development and to obtain information on nutrition and antenatal care.3

We identified apps and rated their contents and features.4 To identify the apps, we performed a Google search to mimic what a patient may do. We scored the identified apps based on what has been shown to make apps successful, as well as desired functions of the most commonly used apps. The quality of the applications was relatively varied, with many of the apps (60%) not having comprehensive information for every stage of pregnancy and no app attaining a perfect score. However, the top 3 apps had near perfect scores of 15/16 and 14/16, missing points only for having advertisements and requiring an internet connection.

The table details these top 3 recommended pregnancy apps, along with a detailed shortened version of the APPLICATIONS scoring system, APPLI (App comprehensiveness, Price, Platform, Literature Used, Other special features). We hope this column will help you feel comfortable in helping patients use pregnancy apps, should they ask for recommendations.

1. Romano AM. A changing landscape: implications of pregnant women’s internet use for childbirth educators. J Perinat Educ. 2007;16:18-24. doi: 10.1624/105812407X244903.

2. Jayaseelan R, Pichandy C, Rushandramani D. Usage of smartphone apps by women on their maternal life. J Mass Communicat Journalism. 2015;29:05:158-164. doi: 10.4172/2165-7912.1000267.

3. Wang N, Deng Z, Wen LM, et al. Understanding the use of smartphone apps for health information among pregnant Chinese women: mixed methods study. JMIR mHealth uHealth. 2019;18:7:e12631. doi: 10.2196/12631.

4. Frid G, Bogaert K, Chen KT. Mobile health apps for pregnant women: systematic search, evaluation, and analysis of features. J Med Internet Res. 2021;18:23:e25667. doi: 10.2196/25667.

1. Romano AM. A changing landscape: implications of pregnant women’s internet use for childbirth educators. J Perinat Educ. 2007;16:18-24. doi: 10.1624/105812407X244903.

2. Jayaseelan R, Pichandy C, Rushandramani D. Usage of smartphone apps by women on their maternal life. J Mass Communicat Journalism. 2015;29:05:158-164. doi: 10.4172/2165-7912.1000267.

3. Wang N, Deng Z, Wen LM, et al. Understanding the use of smartphone apps for health information among pregnant Chinese women: mixed methods study. JMIR mHealth uHealth. 2019;18:7:e12631. doi: 10.2196/12631.

4. Frid G, Bogaert K, Chen KT. Mobile health apps for pregnant women: systematic search, evaluation, and analysis of features. J Med Internet Res. 2021;18:23:e25667. doi: 10.2196/25667.

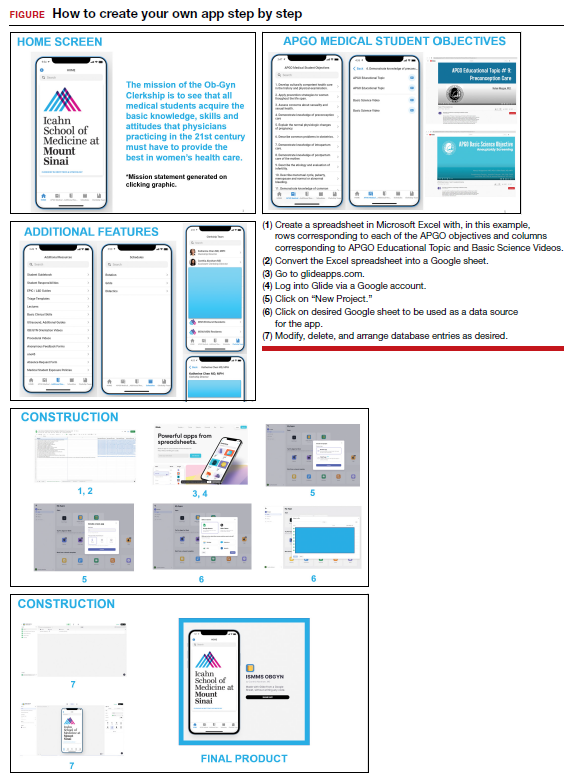

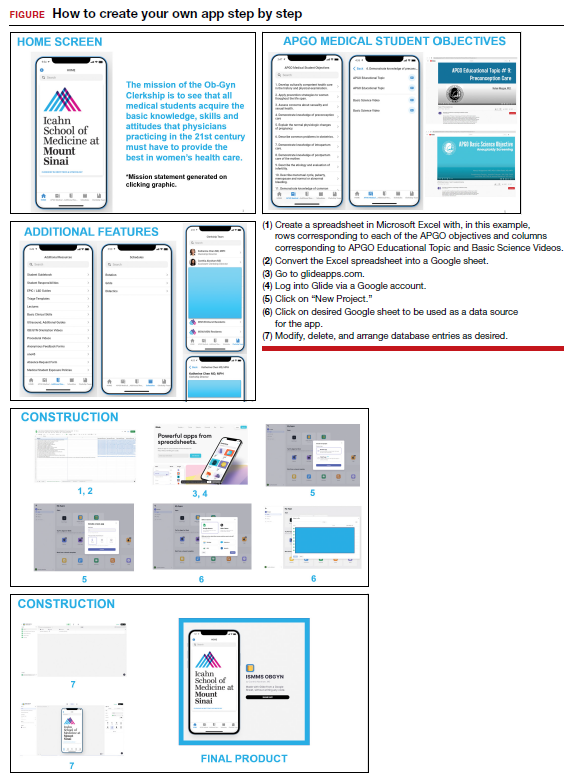

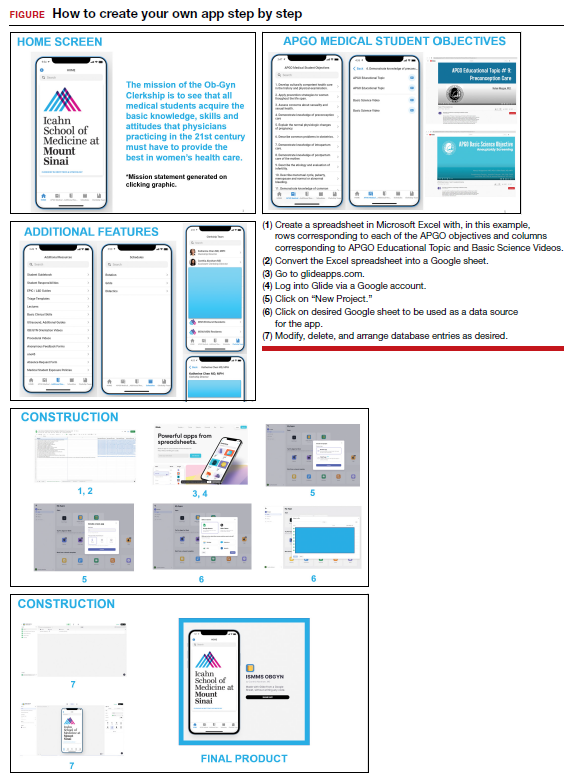

Home-grown apps for ObGyn clerkship students

Technology has revolutionized how we access information. One example is the increased use of mobile applications (apps). On the surface, building a new app may seem a daunting and intimidating task. However, new software—such as Glide (glideapps.com)—make it easy for anyone to design, build, and launch a custom web app within hours. This software is free for basic apps but does offer an upgrade for those wanting more professional services (glide-apps.com/pro). Here, by way of example, we identify an area of need and walk the reader

through the process of making an app.

Although there are many apps aimed at educating users on different aspects of obstetrics and gynecology, few are focused on undergraduate medical education (UME). With the assistance of Glide app building software, we created an app focused on providing rapid access to resources aimed at fulfilling medical student objectives from the Association of Professors of Gynecology and Obstetrics (APGO).1 We included 16 of the APGO objectives. On clicking an objective, the user is taken to a screen with links to associated APGO Educational Topic Video and Basic Science Videos. Basic Science Video links were included in order to provide longitudinal learning between the pre-clinical and clinical years of UME. We also created a tab for additional educational resources (including excerpts from the APGO Basic Clinical Skills Curriculum).2 We eventually added two other tabs: one for clerkship schedules that allows students to organize their daily schedule and another that facilitates quick contact with members of the clerkship team. As expected, the app was well-received by our students.

The steps needed for you to make your own app are listed in the FIGURE along with accompanying images for easy navigation. ●

- Association of Professors of Gynecology and Obstetrics (APGO) Medical Student Educational Objectives, 11th ed;2019.

- Association of Professors of Gynecology and Obstetrics (APGO) Basic Clinical Skills Curriculum. Updated 2017.

Technology has revolutionized how we access information. One example is the increased use of mobile applications (apps). On the surface, building a new app may seem a daunting and intimidating task. However, new software—such as Glide (glideapps.com)—make it easy for anyone to design, build, and launch a custom web app within hours. This software is free for basic apps but does offer an upgrade for those wanting more professional services (glide-apps.com/pro). Here, by way of example, we identify an area of need and walk the reader

through the process of making an app.

Although there are many apps aimed at educating users on different aspects of obstetrics and gynecology, few are focused on undergraduate medical education (UME). With the assistance of Glide app building software, we created an app focused on providing rapid access to resources aimed at fulfilling medical student objectives from the Association of Professors of Gynecology and Obstetrics (APGO).1 We included 16 of the APGO objectives. On clicking an objective, the user is taken to a screen with links to associated APGO Educational Topic Video and Basic Science Videos. Basic Science Video links were included in order to provide longitudinal learning between the pre-clinical and clinical years of UME. We also created a tab for additional educational resources (including excerpts from the APGO Basic Clinical Skills Curriculum).2 We eventually added two other tabs: one for clerkship schedules that allows students to organize their daily schedule and another that facilitates quick contact with members of the clerkship team. As expected, the app was well-received by our students.

The steps needed for you to make your own app are listed in the FIGURE along with accompanying images for easy navigation. ●

Technology has revolutionized how we access information. One example is the increased use of mobile applications (apps). On the surface, building a new app may seem a daunting and intimidating task. However, new software—such as Glide (glideapps.com)—make it easy for anyone to design, build, and launch a custom web app within hours. This software is free for basic apps but does offer an upgrade for those wanting more professional services (glide-apps.com/pro). Here, by way of example, we identify an area of need and walk the reader

through the process of making an app.

Although there are many apps aimed at educating users on different aspects of obstetrics and gynecology, few are focused on undergraduate medical education (UME). With the assistance of Glide app building software, we created an app focused on providing rapid access to resources aimed at fulfilling medical student objectives from the Association of Professors of Gynecology and Obstetrics (APGO).1 We included 16 of the APGO objectives. On clicking an objective, the user is taken to a screen with links to associated APGO Educational Topic Video and Basic Science Videos. Basic Science Video links were included in order to provide longitudinal learning between the pre-clinical and clinical years of UME. We also created a tab for additional educational resources (including excerpts from the APGO Basic Clinical Skills Curriculum).2 We eventually added two other tabs: one for clerkship schedules that allows students to organize their daily schedule and another that facilitates quick contact with members of the clerkship team. As expected, the app was well-received by our students.

The steps needed for you to make your own app are listed in the FIGURE along with accompanying images for easy navigation. ●

- Association of Professors of Gynecology and Obstetrics (APGO) Medical Student Educational Objectives, 11th ed;2019.

- Association of Professors of Gynecology and Obstetrics (APGO) Basic Clinical Skills Curriculum. Updated 2017.

- Association of Professors of Gynecology and Obstetrics (APGO) Medical Student Educational Objectives, 11th ed;2019.

- Association of Professors of Gynecology and Obstetrics (APGO) Basic Clinical Skills Curriculum. Updated 2017.

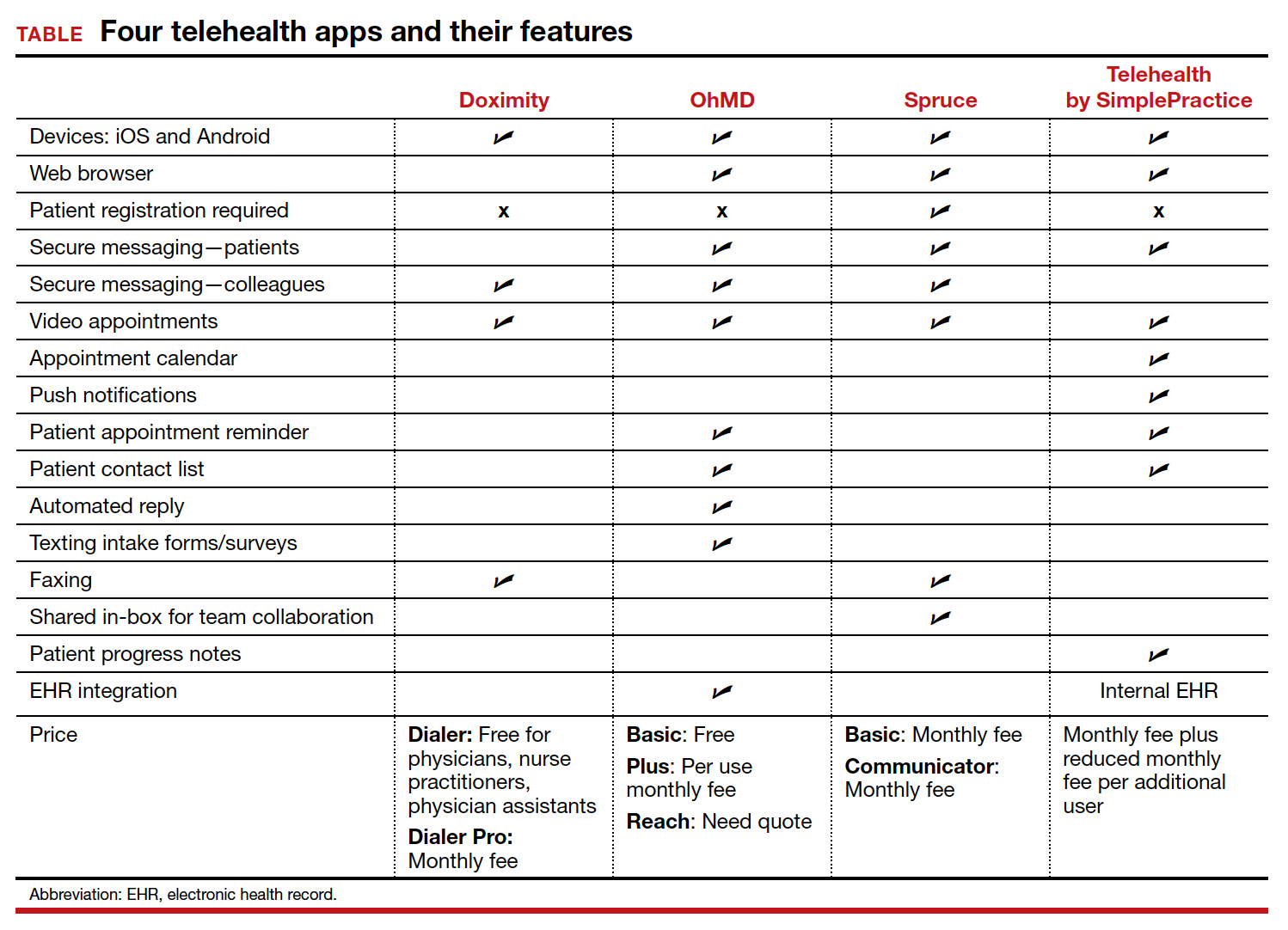

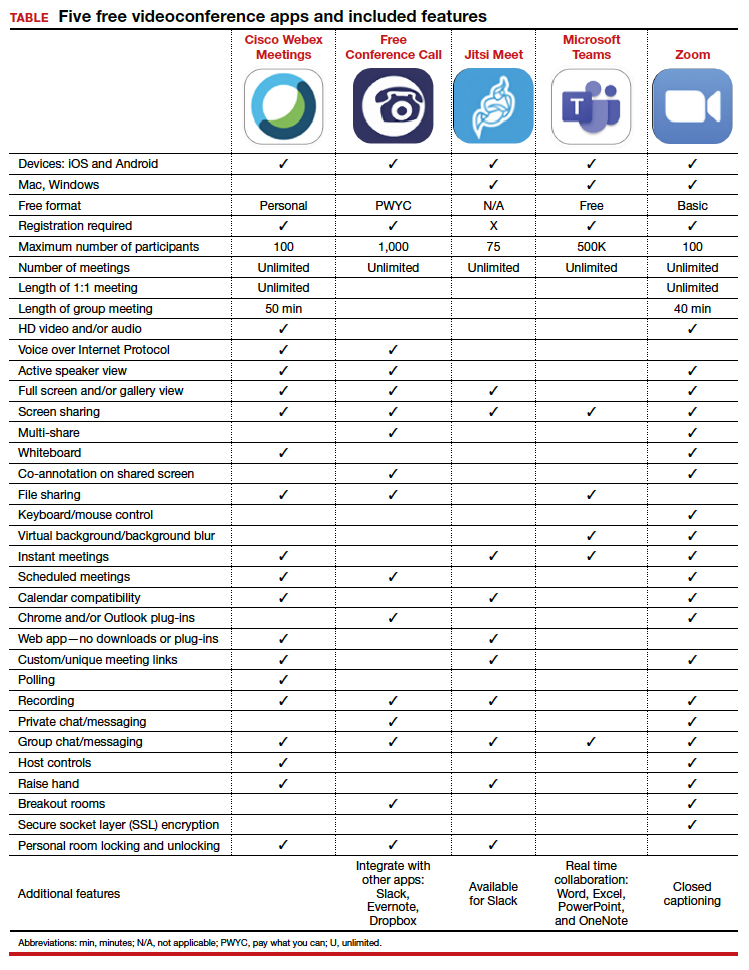

Telehealth apps in ObGyn practice

The COVID-19 pandemic has presented increasing demands on health care systems internationally. In addition to redistribution of inpatient health care resources, outpatient care practices evolved, with health care providers offering streamlined access to care to patients via telehealth.

Due to updated insurance practices, physicians now can receive reimbursement via private insurers, Medicare, and Medicaid (as determined by states) for telehealth visits both related and unrelated to COVID-19 care. Increased telehealth use has advantages, including increased health care access, reduced in-clinic wait times, and reduced patient and physician travel time. Within the field of obstetrics and gynecology, clinicians have used telehealth to maintain access to prenatal maternity care while redirecting resources and minimizing the risk of COVID-19 transmission. Additional advantages include provision of care during expanded hours, including evenings and weekends, to increase patient access without increasing the demand on office support staff and the ability to bill for 5- to 10-minute phone counseling encounters.1 Research shows that patients express satisfaction regarding the quality of telehealth care in the setting of prenatal care.2

In February 2020, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) released a Committee Opinion regarding telehealth use in ObGyn, a sign of telehealth’s likely long-standing role within the field.3 Within the statement, ACOG commented on the increasing application of telemedicine in all aspects of obstetrics and gynecology and recommended that physicians become acquainted with new technologies and consider using them in their practice.

There is a large opportunity for development of mobile applications (apps) to further streamline telehealth-based medical care. During the pandemic, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services instituted waivers for telemedicine use on non-HIPAA (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act) compliant video communications products, such as Google+ Hangout and Skype. However, HIPAA-compliant video services are preferred, and many virtual apps have released methods for patient communication that meet HIPAA guidelines.1,4 These apps offer services such as phone- and video-based patient visits, appointment scheduling, secure physician-patient messaging, and electronic health record (EHR) documentation.

App recommendations

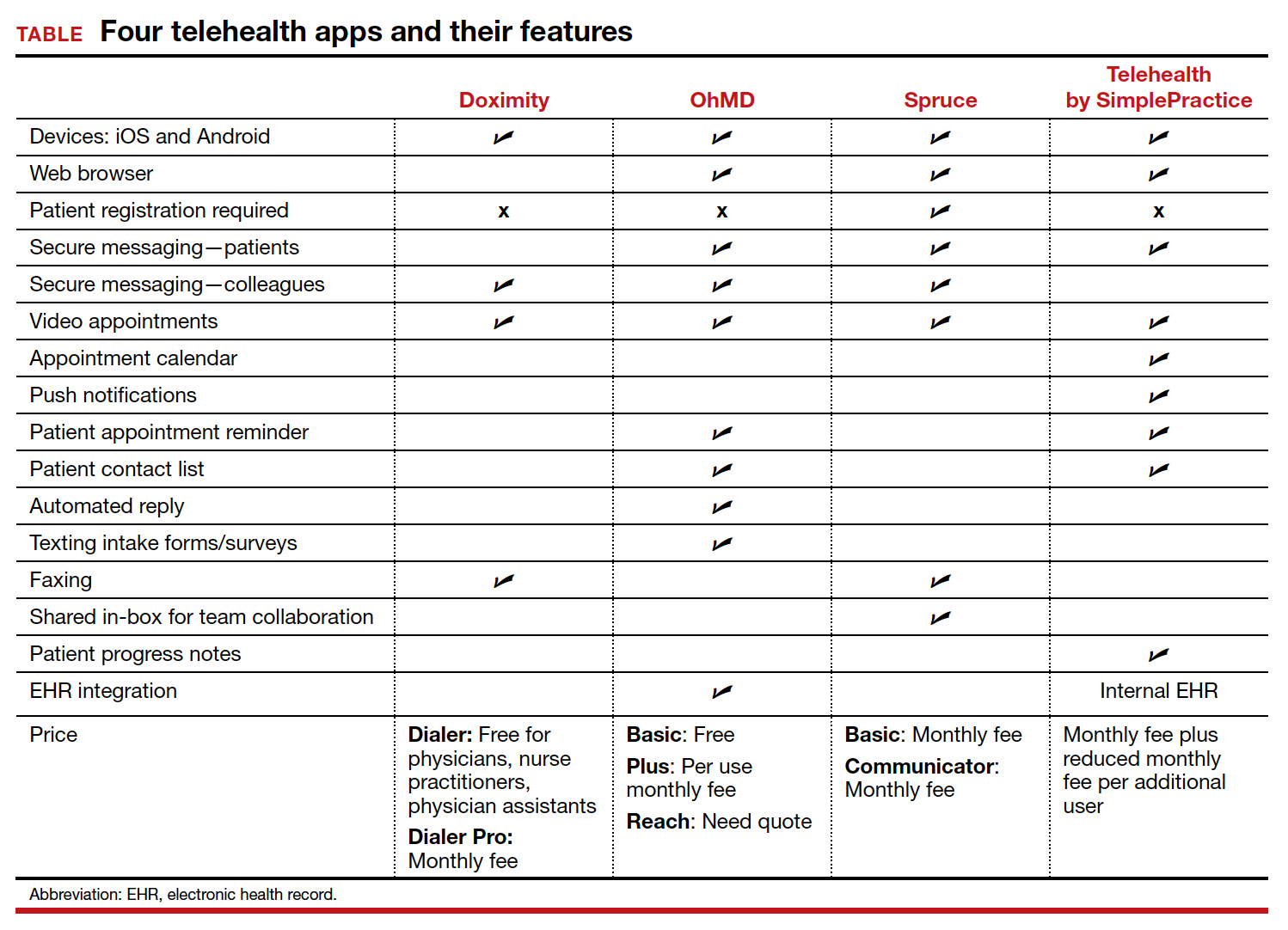

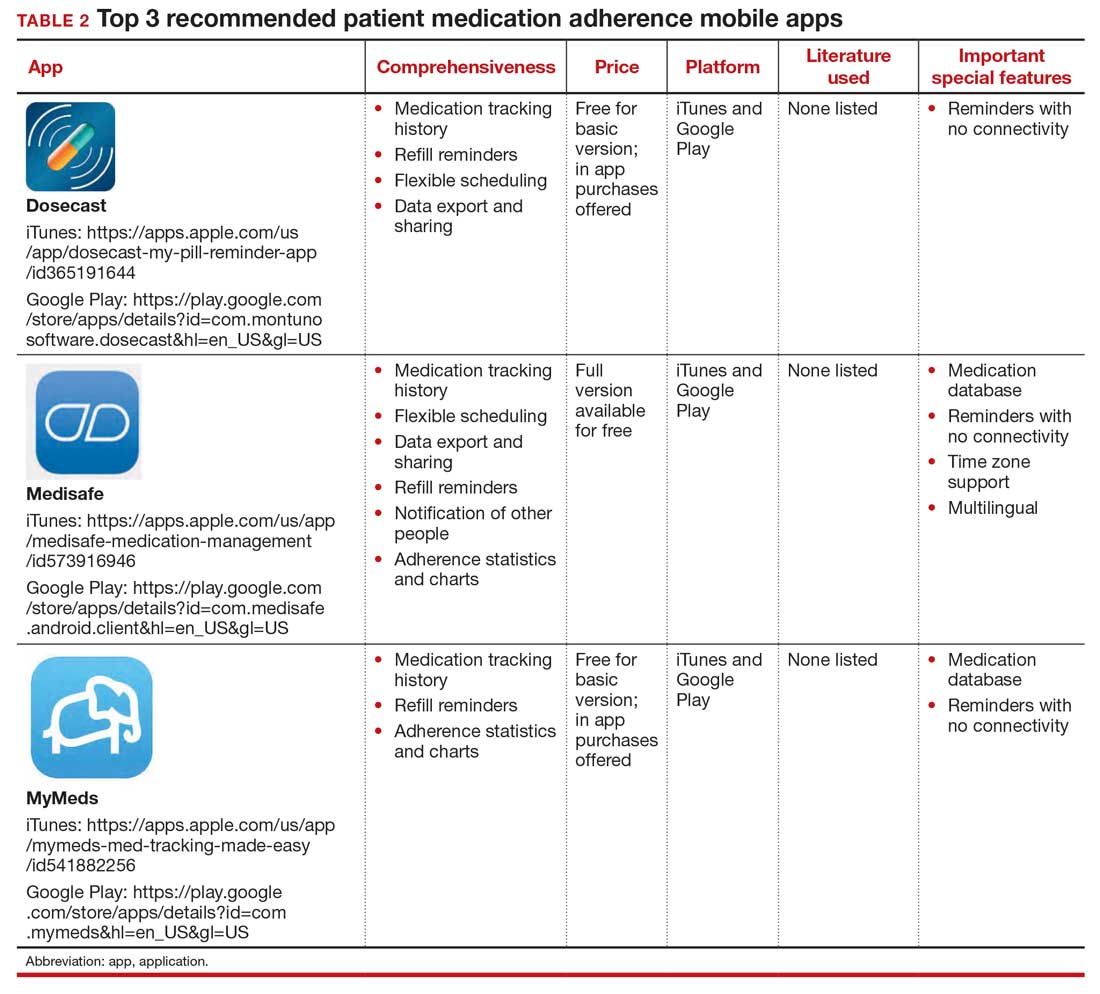

To identify current mobile apps with clinical use for the ObGyn, we conducted a search of the Apple App Store using the term “telehealth” between December 1, 2021 and January 1, 2022. We limited search results to apps that had at least 1,000 user ratings and to HIPAA-compliant user communication apps. Based on our review, we selected 4 apps to highlight here: Doximity, OhMD, Spruce, and Telehealth by SimplePractice (TABLE). We excluded apps that were advertised as having internal medical clinicians with first patient encounter on-demand through the app or that were associated with a singular insurance company or hospital system.

These apps are largely enabled for iOS and Android mobile devices and are offered at a range of price points for individual physician and practice-scale clinical implementation. Most apps offer secure messaging services between health care practitioners in addition to HIPAA-compliant patient messaging. Some apps offer additional features with the aim to increase patient attendance; these include push notifications, appointment reminders, and an option for automated replies with clinic information. For an additional fee, several apps offer integration to established EHR systems.

An additional tool

The COVID-19 pandemic caused health care systems and individual clinicians to rapidly evolve their practices to maintain patient access to essential health care. Notably, the pandemic led to accelerated implementation of virtual health care services. Telehealth apps likely will become another tool that ObGyns can use to improve the efficiency of their clinical practice and expand patient access to care. ●

- Karram M, Baum N. Telemedicine: a primer for today’s ObGyn. OBG Manag. 2020;32:28-32.

- Marko KI, Ganju N, Krapf JM, et al. A mobile prenatal care app to reduce in-person visits: prospective controlled trial. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2019;7:e10520.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Implementing telehealth in practice: committee opinion no. 798. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;135:e73-e79.

- Karram M, Dooley A, de la Houssaye N, et al. Telemedicine: navigating legal issues. OBG Manag. 2020;32:18-24.

The COVID-19 pandemic has presented increasing demands on health care systems internationally. In addition to redistribution of inpatient health care resources, outpatient care practices evolved, with health care providers offering streamlined access to care to patients via telehealth.

Due to updated insurance practices, physicians now can receive reimbursement via private insurers, Medicare, and Medicaid (as determined by states) for telehealth visits both related and unrelated to COVID-19 care. Increased telehealth use has advantages, including increased health care access, reduced in-clinic wait times, and reduced patient and physician travel time. Within the field of obstetrics and gynecology, clinicians have used telehealth to maintain access to prenatal maternity care while redirecting resources and minimizing the risk of COVID-19 transmission. Additional advantages include provision of care during expanded hours, including evenings and weekends, to increase patient access without increasing the demand on office support staff and the ability to bill for 5- to 10-minute phone counseling encounters.1 Research shows that patients express satisfaction regarding the quality of telehealth care in the setting of prenatal care.2

In February 2020, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) released a Committee Opinion regarding telehealth use in ObGyn, a sign of telehealth’s likely long-standing role within the field.3 Within the statement, ACOG commented on the increasing application of telemedicine in all aspects of obstetrics and gynecology and recommended that physicians become acquainted with new technologies and consider using them in their practice.

There is a large opportunity for development of mobile applications (apps) to further streamline telehealth-based medical care. During the pandemic, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services instituted waivers for telemedicine use on non-HIPAA (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act) compliant video communications products, such as Google+ Hangout and Skype. However, HIPAA-compliant video services are preferred, and many virtual apps have released methods for patient communication that meet HIPAA guidelines.1,4 These apps offer services such as phone- and video-based patient visits, appointment scheduling, secure physician-patient messaging, and electronic health record (EHR) documentation.

App recommendations

To identify current mobile apps with clinical use for the ObGyn, we conducted a search of the Apple App Store using the term “telehealth” between December 1, 2021 and January 1, 2022. We limited search results to apps that had at least 1,000 user ratings and to HIPAA-compliant user communication apps. Based on our review, we selected 4 apps to highlight here: Doximity, OhMD, Spruce, and Telehealth by SimplePractice (TABLE). We excluded apps that were advertised as having internal medical clinicians with first patient encounter on-demand through the app or that were associated with a singular insurance company or hospital system.

These apps are largely enabled for iOS and Android mobile devices and are offered at a range of price points for individual physician and practice-scale clinical implementation. Most apps offer secure messaging services between health care practitioners in addition to HIPAA-compliant patient messaging. Some apps offer additional features with the aim to increase patient attendance; these include push notifications, appointment reminders, and an option for automated replies with clinic information. For an additional fee, several apps offer integration to established EHR systems.

An additional tool

The COVID-19 pandemic caused health care systems and individual clinicians to rapidly evolve their practices to maintain patient access to essential health care. Notably, the pandemic led to accelerated implementation of virtual health care services. Telehealth apps likely will become another tool that ObGyns can use to improve the efficiency of their clinical practice and expand patient access to care. ●

The COVID-19 pandemic has presented increasing demands on health care systems internationally. In addition to redistribution of inpatient health care resources, outpatient care practices evolved, with health care providers offering streamlined access to care to patients via telehealth.

Due to updated insurance practices, physicians now can receive reimbursement via private insurers, Medicare, and Medicaid (as determined by states) for telehealth visits both related and unrelated to COVID-19 care. Increased telehealth use has advantages, including increased health care access, reduced in-clinic wait times, and reduced patient and physician travel time. Within the field of obstetrics and gynecology, clinicians have used telehealth to maintain access to prenatal maternity care while redirecting resources and minimizing the risk of COVID-19 transmission. Additional advantages include provision of care during expanded hours, including evenings and weekends, to increase patient access without increasing the demand on office support staff and the ability to bill for 5- to 10-minute phone counseling encounters.1 Research shows that patients express satisfaction regarding the quality of telehealth care in the setting of prenatal care.2

In February 2020, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) released a Committee Opinion regarding telehealth use in ObGyn, a sign of telehealth’s likely long-standing role within the field.3 Within the statement, ACOG commented on the increasing application of telemedicine in all aspects of obstetrics and gynecology and recommended that physicians become acquainted with new technologies and consider using them in their practice.

There is a large opportunity for development of mobile applications (apps) to further streamline telehealth-based medical care. During the pandemic, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services instituted waivers for telemedicine use on non-HIPAA (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act) compliant video communications products, such as Google+ Hangout and Skype. However, HIPAA-compliant video services are preferred, and many virtual apps have released methods for patient communication that meet HIPAA guidelines.1,4 These apps offer services such as phone- and video-based patient visits, appointment scheduling, secure physician-patient messaging, and electronic health record (EHR) documentation.

App recommendations

To identify current mobile apps with clinical use for the ObGyn, we conducted a search of the Apple App Store using the term “telehealth” between December 1, 2021 and January 1, 2022. We limited search results to apps that had at least 1,000 user ratings and to HIPAA-compliant user communication apps. Based on our review, we selected 4 apps to highlight here: Doximity, OhMD, Spruce, and Telehealth by SimplePractice (TABLE). We excluded apps that were advertised as having internal medical clinicians with first patient encounter on-demand through the app or that were associated with a singular insurance company or hospital system.

These apps are largely enabled for iOS and Android mobile devices and are offered at a range of price points for individual physician and practice-scale clinical implementation. Most apps offer secure messaging services between health care practitioners in addition to HIPAA-compliant patient messaging. Some apps offer additional features with the aim to increase patient attendance; these include push notifications, appointment reminders, and an option for automated replies with clinic information. For an additional fee, several apps offer integration to established EHR systems.

An additional tool

The COVID-19 pandemic caused health care systems and individual clinicians to rapidly evolve their practices to maintain patient access to essential health care. Notably, the pandemic led to accelerated implementation of virtual health care services. Telehealth apps likely will become another tool that ObGyns can use to improve the efficiency of their clinical practice and expand patient access to care. ●

- Karram M, Baum N. Telemedicine: a primer for today’s ObGyn. OBG Manag. 2020;32:28-32.

- Marko KI, Ganju N, Krapf JM, et al. A mobile prenatal care app to reduce in-person visits: prospective controlled trial. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2019;7:e10520.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Implementing telehealth in practice: committee opinion no. 798. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;135:e73-e79.

- Karram M, Dooley A, de la Houssaye N, et al. Telemedicine: navigating legal issues. OBG Manag. 2020;32:18-24.

- Karram M, Baum N. Telemedicine: a primer for today’s ObGyn. OBG Manag. 2020;32:28-32.

- Marko KI, Ganju N, Krapf JM, et al. A mobile prenatal care app to reduce in-person visits: prospective controlled trial. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2019;7:e10520.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Implementing telehealth in practice: committee opinion no. 798. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;135:e73-e79.

- Karram M, Dooley A, de la Houssaye N, et al. Telemedicine: navigating legal issues. OBG Manag. 2020;32:18-24.

Patient-facing mobile apps: Are ObGyns uniquely positioned to integrate them into practice?

Incorporating mobile apps into patient care programs can add immense value. Mobile apps enable data collection when a patient is beyond the walls of a doctor’s office and equip clinicians with new and relevant patient data. Patient engagement apps also provide a mechanism to “nudge” patients to encourage adherence to their care programs. These additional data and increased patient adherence can enable more personalized care,1 and ultimately can lead to improved outcomes. For example, a meta-analysis of 1,657 patients with diabetes showed a 5% reduction in hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) values for those who used a diabetes-related app.2 The literature also shows positive results for heart failure, weight management, smoking reduction, and lifestyle improvement.3-5 Given their value, why aren’t patient engagement apps more routinely integrated into patient care programs?

From a software development perspective, mobile apps are fairly easy to create. However, from a user retention standpoint, creating an app with a large, sustainable userbase is challenging.5 User retention is measured in monthly active users. We are familiar with unused apps collecting digital dust on our smartphone home screens. A 2019 study showed that 25% of people typically use an application only once,6 and health care apps are not an exception. There are hundreds of thousands of mobile health apps on the market, but only 7% of these applications have more than 50,000 monthly active users. Further, 62% of digital health apps have less than 1,000 monthly active users.7

Using a new app daily or several times weekly requires new habit formation. Anyone who has tried to incorporate a new routine into their daily life knows how difficult habit formation can be. However, ObGyn patients may be particularly well suited to incorporate ObGyn-related apps into their care, given how many women already use mobile applications to track their menstrual cycles. A recent survey found that across all age groups, 47% of women use a mobile phone app to track their menstrual cycle,8 compared with 8% of US adults who regularly use an app to measure general health metrics.7 This removes one of the largest obstacles of market penetration since the habit of using an app for ObGyn purposes has already been established. As such, it presents an exciting opportunity to capitalize on the userbase already leveraging mobile apps to track their cycles and expand the patient engagement footprint into additional features that can broaden care to create a seamless, holistic patient application for ObGyn patient care.

One can envision a future in which a patient is “prescribed” an ObGyn app during their ObGyn appointment. Within the app, the patient can track their health data, engage with health providers, and gain access to educational materials. The clinician would be able to access data captured in the patient app at an aggregate level to analyze trends over time.

Current, patient-facing ObGyn mobile apps available for download on smartphones are for targeted aspects of ObGyn health. For example, there are separate apps for menstrual cycle tracking, contraception education, and medication adherence tracking. In the future, it would be ideal for clinicians and patients to have access to a single, holistic ObGyn mobile app that supports the end-to-end ObGyn patient journey, one in which clinicians could turn modules on or off given specific patient concerns. The technology for this type of holistic patient engagement platform exists, but unfortunately it is not as simple as downloading a mobile app. Standing up an end-to-end patient engagement platform requires enterprise-wide buy-in, tailoring user workflows, and building out integrations (eg, integrating provider dashboards into the existing electronic health record system). Full-scale solutions are powerful, but they can be expensive and time consuming to stand up. Until there is a more streamlined, outside-the-box ObGyn-tailored solution, there are patientfacing mobile apps available to support your patients for specific concerns.

Continue to: The top 3 recommended menstrual cycle tracking apps...

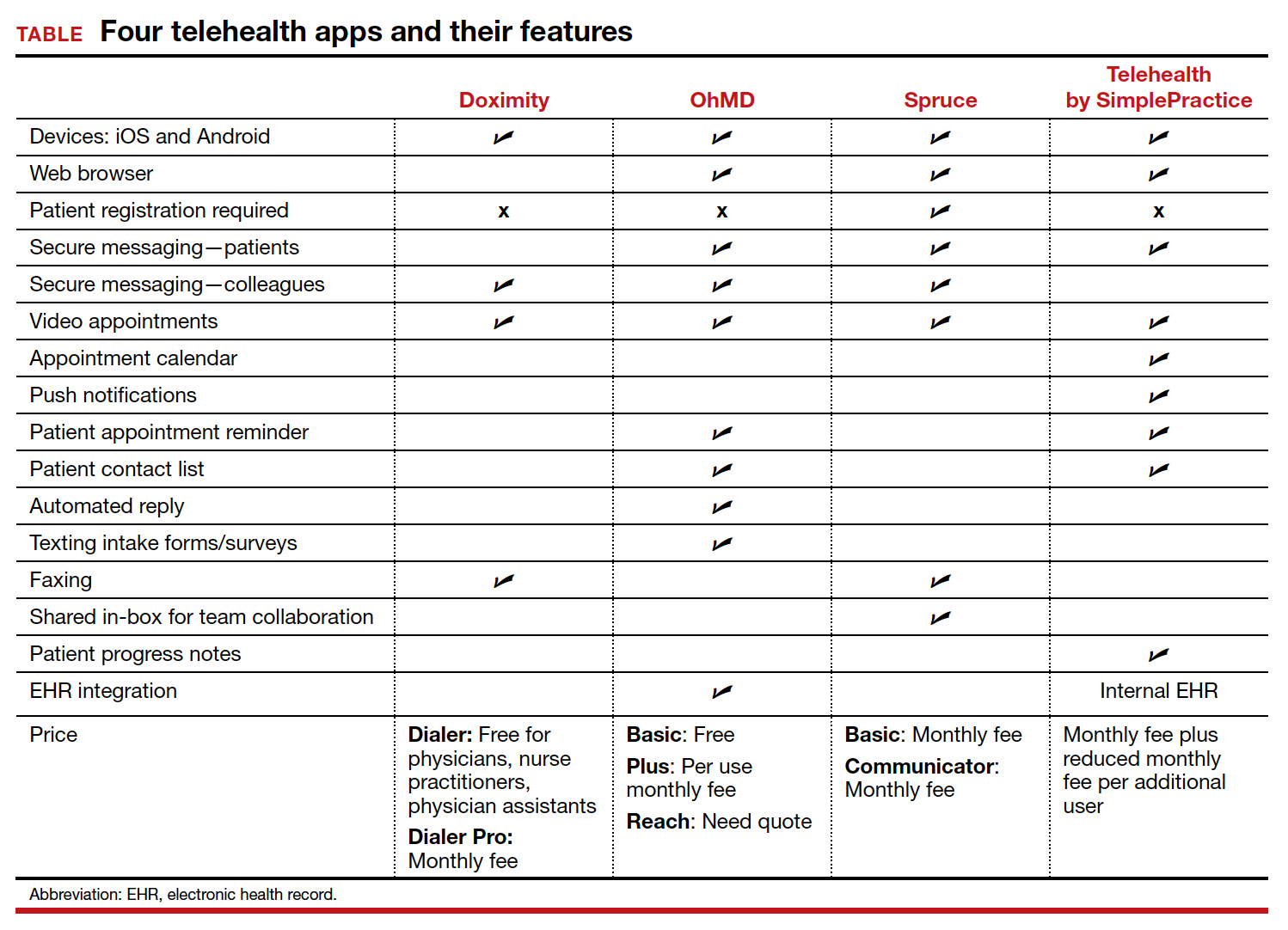

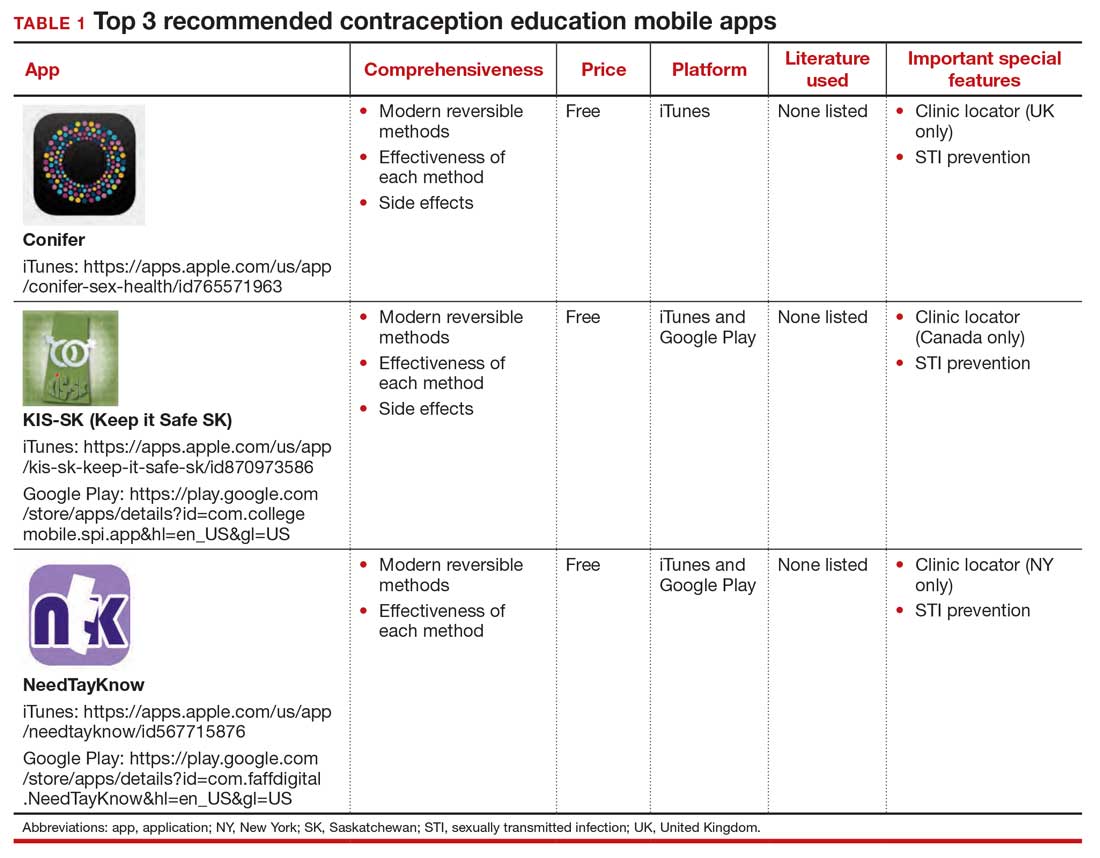

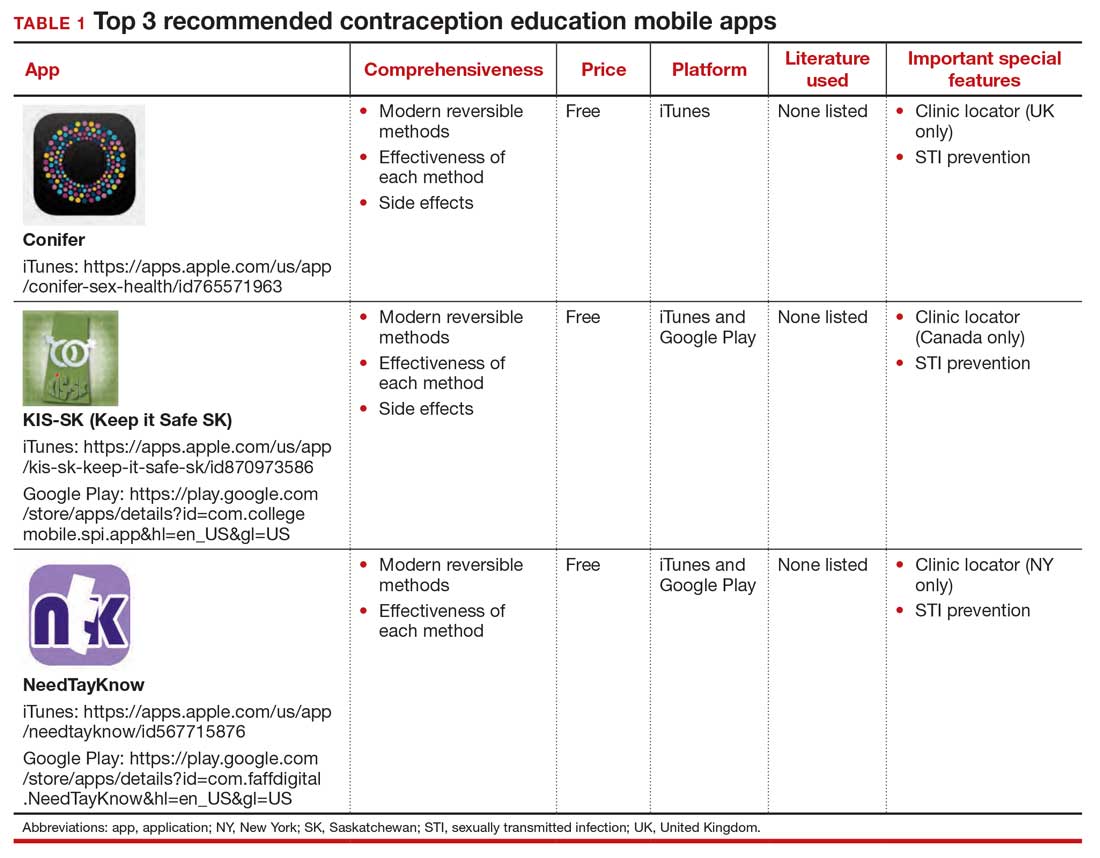

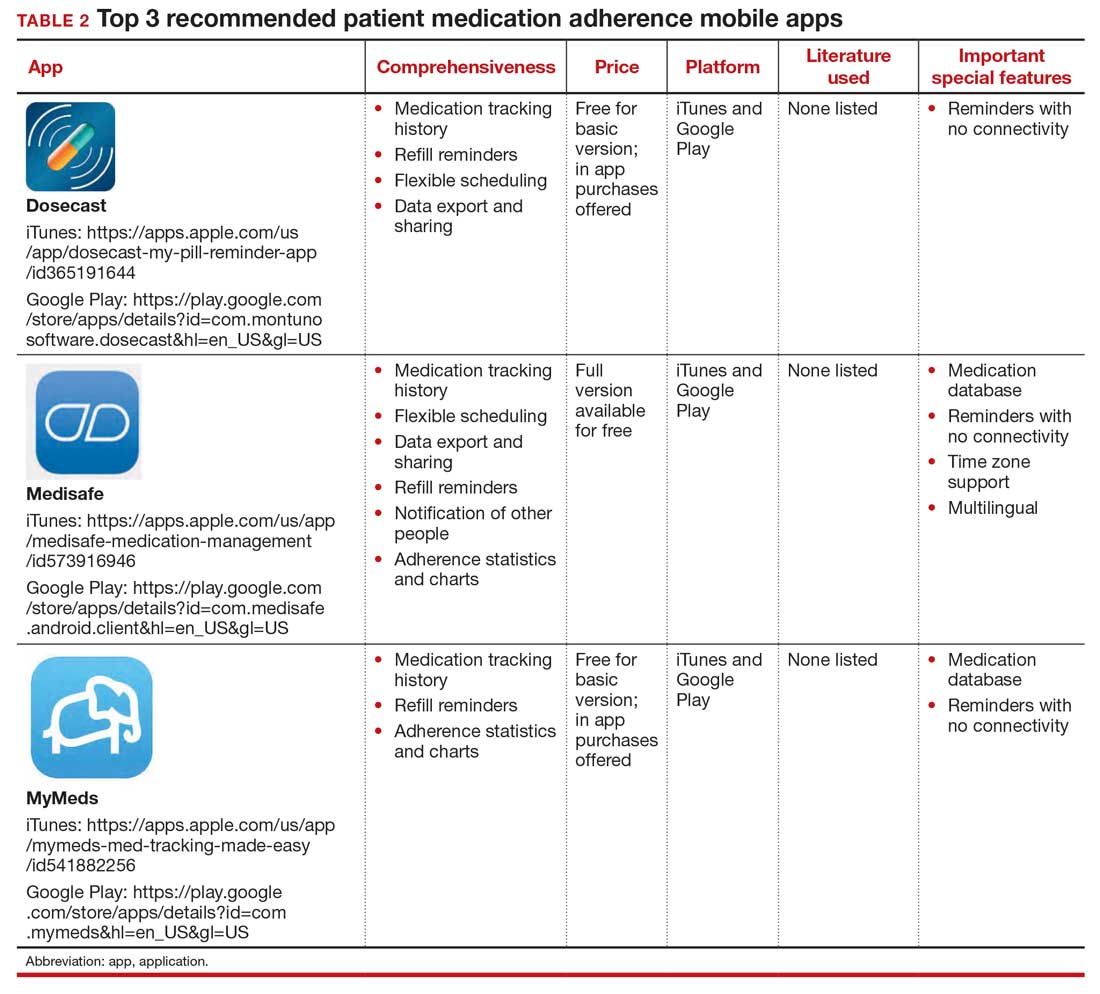

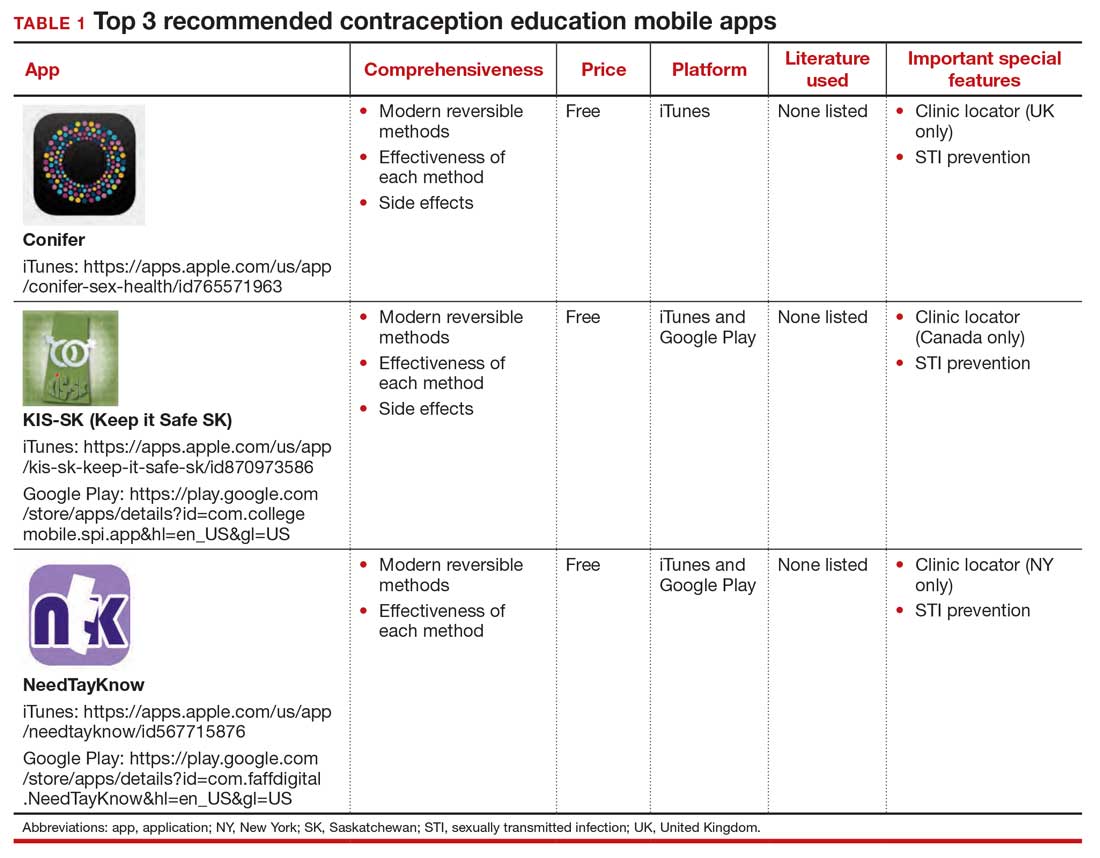

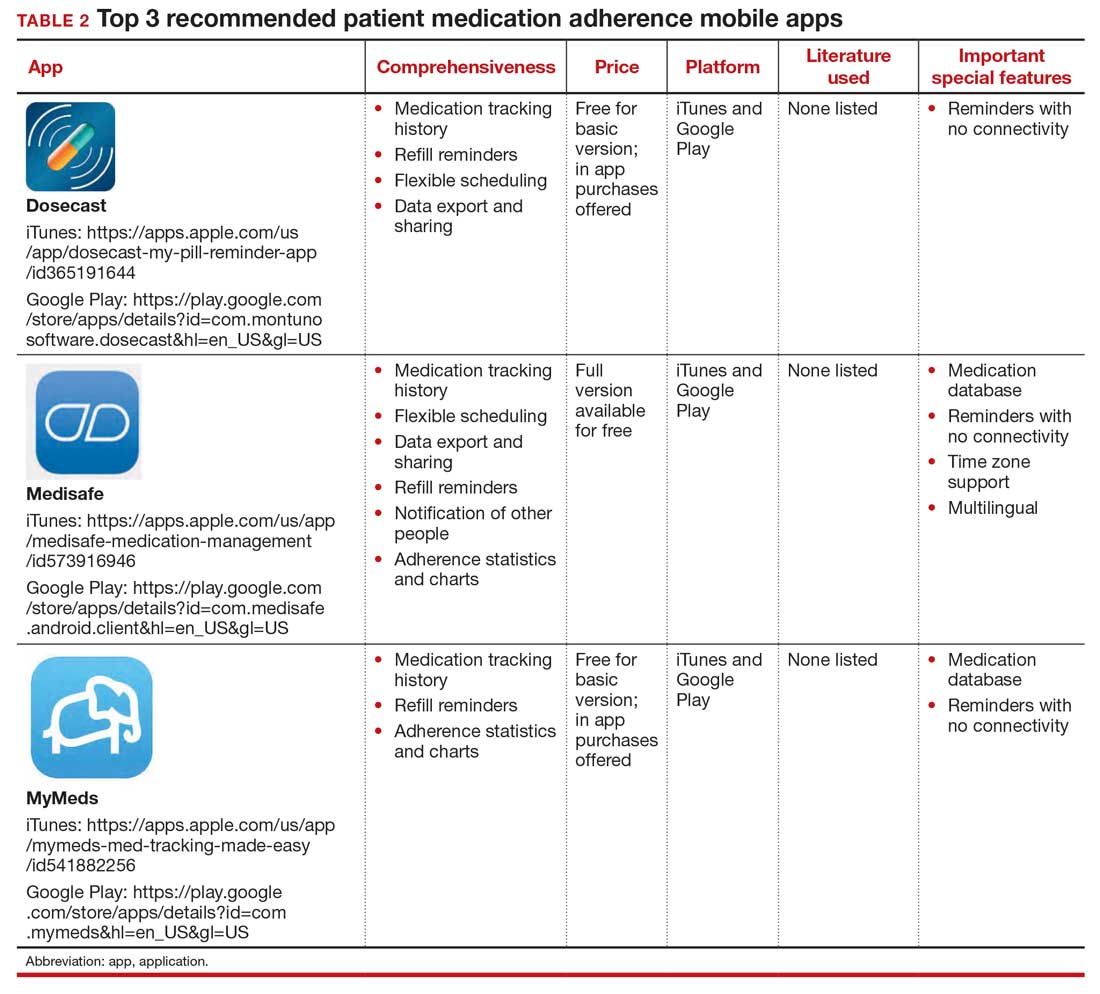

The top 3 recommended menstrual cycle tracking apps from Moglia and colleagues9 are listed in Dr. Chen’s article, “Top free menstrual cycle tracking apps for your patients.”10 The top 3 recommended contraception education mobile apps from Lunde and colleagues11 are listed in TABLE 1 and are detailed with a shortened version of the APPLICATIONS scoring system, APPLI (app comprehensiveness, price, platform, literature use, important special features).12 The top 3 recommended patient medication adherence mobile apps from the study by Santo and colleagues13 are listed in TABLE 2. The apps in the Stoyanov et al14 study were evaluated using the 23-item Mobile App Rating System scale. ●

- van Dijk MR, Koster MPH, et al. Healthy preconception nutrition and lifestyle using personalized mobile health coaching is associated with enhanced pregnancy chance. Reprod BioMed Online. 2017;35:453-460. doi:10.1016/j. rbmo.2017.06.014.

- Liang X, Wang Q, Yang X, et al. Effect of mobile phone intervention for diabetes on glycaemic control: a metaanalysis. Diabet Med. 2011;28:455-463. doi:10.1111/j.1464- 5491.2010.03180.x.

- Laing BY, Mangione CM, Tseng C-H, et al. Effectiveness of a smartphone application for weight loss compared with usual care in overweight primary care patients. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161(10 suppl):S5-S12. doi:10.7326/m13-3005.

- Dennison L, Morrison L, Conway G, et al. Opportunities and challenges for smartphone applications in supporting health behavior change: qualitative study. J Med Internet Res. 2013;15:E86. doi:10.2196/jmir.2583.

- Schoeppe S, Alley S, Van Lippevelde W, et al. Efficacy of interventions that use apps to improve diet, physical activity and sedentary behaviour: a systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2016;13:127. doi:10.1186/s12966- 016-0454-y.

- 25% of users abandon apps after one use. Upland Software website. Accessed May 6, 2021. https://uplandsoftware.com /localytics/resources/blog/25-of-users-abandon-apps-afterone-use/.

- mHealth economics 2017/2018 – connectivity in digital health. Published March 5, 2019. Accessed May 6, 2021. https:// research2guidance.com/product/connectivity-in-digitalhealth/.

- Epstein DA, Lee NB, Kang JH, et al. Examining menstrual tracking to inform the design of personal informatics tools. Proc SIGCHI Conf Hum Factor Comput Syst. 2017;2017:6876- 6888. doi:10.1145/3025453.3025635.

- Moglia M, Nguyen H, Chyjek K, et al. Evaluation of smartphone menstrual cycle tracking applications using an adapted APPLICATIONS scoring system. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127:1153-1160. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000001444.

- Chen KT. Top free menstrual cycle tracking apps for your patients. OBG Manag. 2017;27:44-45.

- Lunde B, Perry R, Sridhar A, et al. An evaluation of contraception education and health promotion applications for patients. Womens Health Issues. 2017;27:29-35. doi:10.1016/j.whi.2016.09.012.

- Chyjek K, Farag S, Chen KT. Rating pregnancy wheel applications using the APPLICATIONS scoring system. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:1478-1483. doi:10.1097 /AOG.0000000000000842.

- Santo K, Richtering SS, Chalmers J, et al. Mobile phone apps to improve medication adherence: a systematic stepwise process to identify high-quality apps. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2016;4:E132. doi:10.2196/mhealth.6742.

- Stoyanov SR, Hides L, Kavanagh DJ, et al. Mobile app rating scale: a new tool for assessing the quality of health mobile apps. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2015;3:E27. doi:10.2196 /mhealth.3422.

Incorporating mobile apps into patient care programs can add immense value. Mobile apps enable data collection when a patient is beyond the walls of a doctor’s office and equip clinicians with new and relevant patient data. Patient engagement apps also provide a mechanism to “nudge” patients to encourage adherence to their care programs. These additional data and increased patient adherence can enable more personalized care,1 and ultimately can lead to improved outcomes. For example, a meta-analysis of 1,657 patients with diabetes showed a 5% reduction in hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) values for those who used a diabetes-related app.2 The literature also shows positive results for heart failure, weight management, smoking reduction, and lifestyle improvement.3-5 Given their value, why aren’t patient engagement apps more routinely integrated into patient care programs?

From a software development perspective, mobile apps are fairly easy to create. However, from a user retention standpoint, creating an app with a large, sustainable userbase is challenging.5 User retention is measured in monthly active users. We are familiar with unused apps collecting digital dust on our smartphone home screens. A 2019 study showed that 25% of people typically use an application only once,6 and health care apps are not an exception. There are hundreds of thousands of mobile health apps on the market, but only 7% of these applications have more than 50,000 monthly active users. Further, 62% of digital health apps have less than 1,000 monthly active users.7

Using a new app daily or several times weekly requires new habit formation. Anyone who has tried to incorporate a new routine into their daily life knows how difficult habit formation can be. However, ObGyn patients may be particularly well suited to incorporate ObGyn-related apps into their care, given how many women already use mobile applications to track their menstrual cycles. A recent survey found that across all age groups, 47% of women use a mobile phone app to track their menstrual cycle,8 compared with 8% of US adults who regularly use an app to measure general health metrics.7 This removes one of the largest obstacles of market penetration since the habit of using an app for ObGyn purposes has already been established. As such, it presents an exciting opportunity to capitalize on the userbase already leveraging mobile apps to track their cycles and expand the patient engagement footprint into additional features that can broaden care to create a seamless, holistic patient application for ObGyn patient care.

One can envision a future in which a patient is “prescribed” an ObGyn app during their ObGyn appointment. Within the app, the patient can track their health data, engage with health providers, and gain access to educational materials. The clinician would be able to access data captured in the patient app at an aggregate level to analyze trends over time.

Current, patient-facing ObGyn mobile apps available for download on smartphones are for targeted aspects of ObGyn health. For example, there are separate apps for menstrual cycle tracking, contraception education, and medication adherence tracking. In the future, it would be ideal for clinicians and patients to have access to a single, holistic ObGyn mobile app that supports the end-to-end ObGyn patient journey, one in which clinicians could turn modules on or off given specific patient concerns. The technology for this type of holistic patient engagement platform exists, but unfortunately it is not as simple as downloading a mobile app. Standing up an end-to-end patient engagement platform requires enterprise-wide buy-in, tailoring user workflows, and building out integrations (eg, integrating provider dashboards into the existing electronic health record system). Full-scale solutions are powerful, but they can be expensive and time consuming to stand up. Until there is a more streamlined, outside-the-box ObGyn-tailored solution, there are patientfacing mobile apps available to support your patients for specific concerns.

Continue to: The top 3 recommended menstrual cycle tracking apps...

The top 3 recommended menstrual cycle tracking apps from Moglia and colleagues9 are listed in Dr. Chen’s article, “Top free menstrual cycle tracking apps for your patients.”10 The top 3 recommended contraception education mobile apps from Lunde and colleagues11 are listed in TABLE 1 and are detailed with a shortened version of the APPLICATIONS scoring system, APPLI (app comprehensiveness, price, platform, literature use, important special features).12 The top 3 recommended patient medication adherence mobile apps from the study by Santo and colleagues13 are listed in TABLE 2. The apps in the Stoyanov et al14 study were evaluated using the 23-item Mobile App Rating System scale. ●

Incorporating mobile apps into patient care programs can add immense value. Mobile apps enable data collection when a patient is beyond the walls of a doctor’s office and equip clinicians with new and relevant patient data. Patient engagement apps also provide a mechanism to “nudge” patients to encourage adherence to their care programs. These additional data and increased patient adherence can enable more personalized care,1 and ultimately can lead to improved outcomes. For example, a meta-analysis of 1,657 patients with diabetes showed a 5% reduction in hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) values for those who used a diabetes-related app.2 The literature also shows positive results for heart failure, weight management, smoking reduction, and lifestyle improvement.3-5 Given their value, why aren’t patient engagement apps more routinely integrated into patient care programs?

From a software development perspective, mobile apps are fairly easy to create. However, from a user retention standpoint, creating an app with a large, sustainable userbase is challenging.5 User retention is measured in monthly active users. We are familiar with unused apps collecting digital dust on our smartphone home screens. A 2019 study showed that 25% of people typically use an application only once,6 and health care apps are not an exception. There are hundreds of thousands of mobile health apps on the market, but only 7% of these applications have more than 50,000 monthly active users. Further, 62% of digital health apps have less than 1,000 monthly active users.7

Using a new app daily or several times weekly requires new habit formation. Anyone who has tried to incorporate a new routine into their daily life knows how difficult habit formation can be. However, ObGyn patients may be particularly well suited to incorporate ObGyn-related apps into their care, given how many women already use mobile applications to track their menstrual cycles. A recent survey found that across all age groups, 47% of women use a mobile phone app to track their menstrual cycle,8 compared with 8% of US adults who regularly use an app to measure general health metrics.7 This removes one of the largest obstacles of market penetration since the habit of using an app for ObGyn purposes has already been established. As such, it presents an exciting opportunity to capitalize on the userbase already leveraging mobile apps to track their cycles and expand the patient engagement footprint into additional features that can broaden care to create a seamless, holistic patient application for ObGyn patient care.

One can envision a future in which a patient is “prescribed” an ObGyn app during their ObGyn appointment. Within the app, the patient can track their health data, engage with health providers, and gain access to educational materials. The clinician would be able to access data captured in the patient app at an aggregate level to analyze trends over time.

Current, patient-facing ObGyn mobile apps available for download on smartphones are for targeted aspects of ObGyn health. For example, there are separate apps for menstrual cycle tracking, contraception education, and medication adherence tracking. In the future, it would be ideal for clinicians and patients to have access to a single, holistic ObGyn mobile app that supports the end-to-end ObGyn patient journey, one in which clinicians could turn modules on or off given specific patient concerns. The technology for this type of holistic patient engagement platform exists, but unfortunately it is not as simple as downloading a mobile app. Standing up an end-to-end patient engagement platform requires enterprise-wide buy-in, tailoring user workflows, and building out integrations (eg, integrating provider dashboards into the existing electronic health record system). Full-scale solutions are powerful, but they can be expensive and time consuming to stand up. Until there is a more streamlined, outside-the-box ObGyn-tailored solution, there are patientfacing mobile apps available to support your patients for specific concerns.

Continue to: The top 3 recommended menstrual cycle tracking apps...

The top 3 recommended menstrual cycle tracking apps from Moglia and colleagues9 are listed in Dr. Chen’s article, “Top free menstrual cycle tracking apps for your patients.”10 The top 3 recommended contraception education mobile apps from Lunde and colleagues11 are listed in TABLE 1 and are detailed with a shortened version of the APPLICATIONS scoring system, APPLI (app comprehensiveness, price, platform, literature use, important special features).12 The top 3 recommended patient medication adherence mobile apps from the study by Santo and colleagues13 are listed in TABLE 2. The apps in the Stoyanov et al14 study were evaluated using the 23-item Mobile App Rating System scale. ●

- van Dijk MR, Koster MPH, et al. Healthy preconception nutrition and lifestyle using personalized mobile health coaching is associated with enhanced pregnancy chance. Reprod BioMed Online. 2017;35:453-460. doi:10.1016/j. rbmo.2017.06.014.

- Liang X, Wang Q, Yang X, et al. Effect of mobile phone intervention for diabetes on glycaemic control: a metaanalysis. Diabet Med. 2011;28:455-463. doi:10.1111/j.1464- 5491.2010.03180.x.

- Laing BY, Mangione CM, Tseng C-H, et al. Effectiveness of a smartphone application for weight loss compared with usual care in overweight primary care patients. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161(10 suppl):S5-S12. doi:10.7326/m13-3005.

- Dennison L, Morrison L, Conway G, et al. Opportunities and challenges for smartphone applications in supporting health behavior change: qualitative study. J Med Internet Res. 2013;15:E86. doi:10.2196/jmir.2583.

- Schoeppe S, Alley S, Van Lippevelde W, et al. Efficacy of interventions that use apps to improve diet, physical activity and sedentary behaviour: a systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2016;13:127. doi:10.1186/s12966- 016-0454-y.

- 25% of users abandon apps after one use. Upland Software website. Accessed May 6, 2021. https://uplandsoftware.com /localytics/resources/blog/25-of-users-abandon-apps-afterone-use/.

- mHealth economics 2017/2018 – connectivity in digital health. Published March 5, 2019. Accessed May 6, 2021. https:// research2guidance.com/product/connectivity-in-digitalhealth/.

- Epstein DA, Lee NB, Kang JH, et al. Examining menstrual tracking to inform the design of personal informatics tools. Proc SIGCHI Conf Hum Factor Comput Syst. 2017;2017:6876- 6888. doi:10.1145/3025453.3025635.

- Moglia M, Nguyen H, Chyjek K, et al. Evaluation of smartphone menstrual cycle tracking applications using an adapted APPLICATIONS scoring system. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127:1153-1160. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000001444.

- Chen KT. Top free menstrual cycle tracking apps for your patients. OBG Manag. 2017;27:44-45.

- Lunde B, Perry R, Sridhar A, et al. An evaluation of contraception education and health promotion applications for patients. Womens Health Issues. 2017;27:29-35. doi:10.1016/j.whi.2016.09.012.

- Chyjek K, Farag S, Chen KT. Rating pregnancy wheel applications using the APPLICATIONS scoring system. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:1478-1483. doi:10.1097 /AOG.0000000000000842.

- Santo K, Richtering SS, Chalmers J, et al. Mobile phone apps to improve medication adherence: a systematic stepwise process to identify high-quality apps. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2016;4:E132. doi:10.2196/mhealth.6742.

- Stoyanov SR, Hides L, Kavanagh DJ, et al. Mobile app rating scale: a new tool for assessing the quality of health mobile apps. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2015;3:E27. doi:10.2196 /mhealth.3422.

- van Dijk MR, Koster MPH, et al. Healthy preconception nutrition and lifestyle using personalized mobile health coaching is associated with enhanced pregnancy chance. Reprod BioMed Online. 2017;35:453-460. doi:10.1016/j. rbmo.2017.06.014.

- Liang X, Wang Q, Yang X, et al. Effect of mobile phone intervention for diabetes on glycaemic control: a metaanalysis. Diabet Med. 2011;28:455-463. doi:10.1111/j.1464- 5491.2010.03180.x.

- Laing BY, Mangione CM, Tseng C-H, et al. Effectiveness of a smartphone application for weight loss compared with usual care in overweight primary care patients. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161(10 suppl):S5-S12. doi:10.7326/m13-3005.

- Dennison L, Morrison L, Conway G, et al. Opportunities and challenges for smartphone applications in supporting health behavior change: qualitative study. J Med Internet Res. 2013;15:E86. doi:10.2196/jmir.2583.

- Schoeppe S, Alley S, Van Lippevelde W, et al. Efficacy of interventions that use apps to improve diet, physical activity and sedentary behaviour: a systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2016;13:127. doi:10.1186/s12966- 016-0454-y.

- 25% of users abandon apps after one use. Upland Software website. Accessed May 6, 2021. https://uplandsoftware.com /localytics/resources/blog/25-of-users-abandon-apps-afterone-use/.

- mHealth economics 2017/2018 – connectivity in digital health. Published March 5, 2019. Accessed May 6, 2021. https:// research2guidance.com/product/connectivity-in-digitalhealth/.

- Epstein DA, Lee NB, Kang JH, et al. Examining menstrual tracking to inform the design of personal informatics tools. Proc SIGCHI Conf Hum Factor Comput Syst. 2017;2017:6876- 6888. doi:10.1145/3025453.3025635.

- Moglia M, Nguyen H, Chyjek K, et al. Evaluation of smartphone menstrual cycle tracking applications using an adapted APPLICATIONS scoring system. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127:1153-1160. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000001444.

- Chen KT. Top free menstrual cycle tracking apps for your patients. OBG Manag. 2017;27:44-45.

- Lunde B, Perry R, Sridhar A, et al. An evaluation of contraception education and health promotion applications for patients. Womens Health Issues. 2017;27:29-35. doi:10.1016/j.whi.2016.09.012.

- Chyjek K, Farag S, Chen KT. Rating pregnancy wheel applications using the APPLICATIONS scoring system. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:1478-1483. doi:10.1097 /AOG.0000000000000842.

- Santo K, Richtering SS, Chalmers J, et al. Mobile phone apps to improve medication adherence: a systematic stepwise process to identify high-quality apps. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2016;4:E132. doi:10.2196/mhealth.6742.

- Stoyanov SR, Hides L, Kavanagh DJ, et al. Mobile app rating scale: a new tool for assessing the quality of health mobile apps. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2015;3:E27. doi:10.2196 /mhealth.3422.

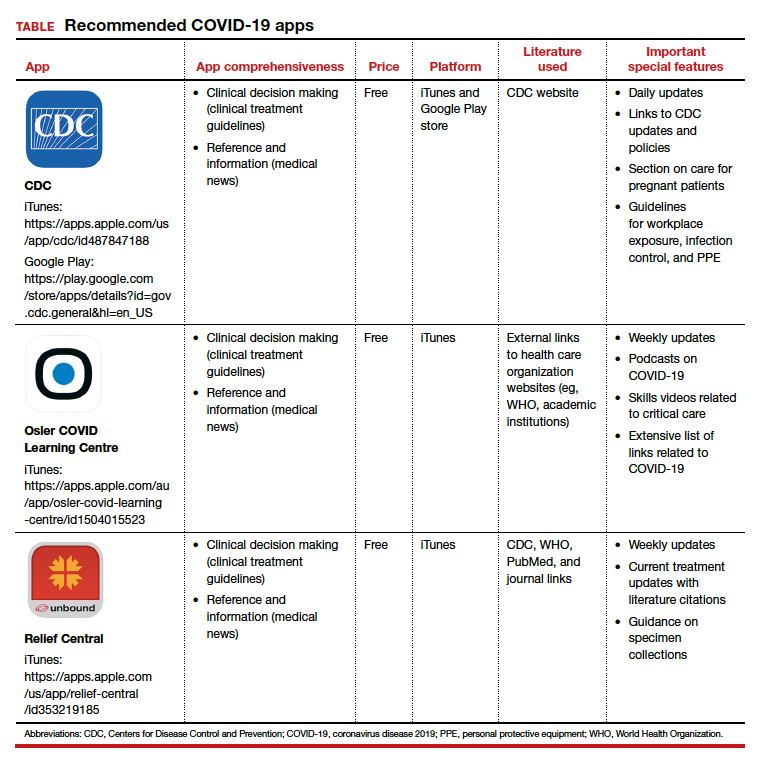

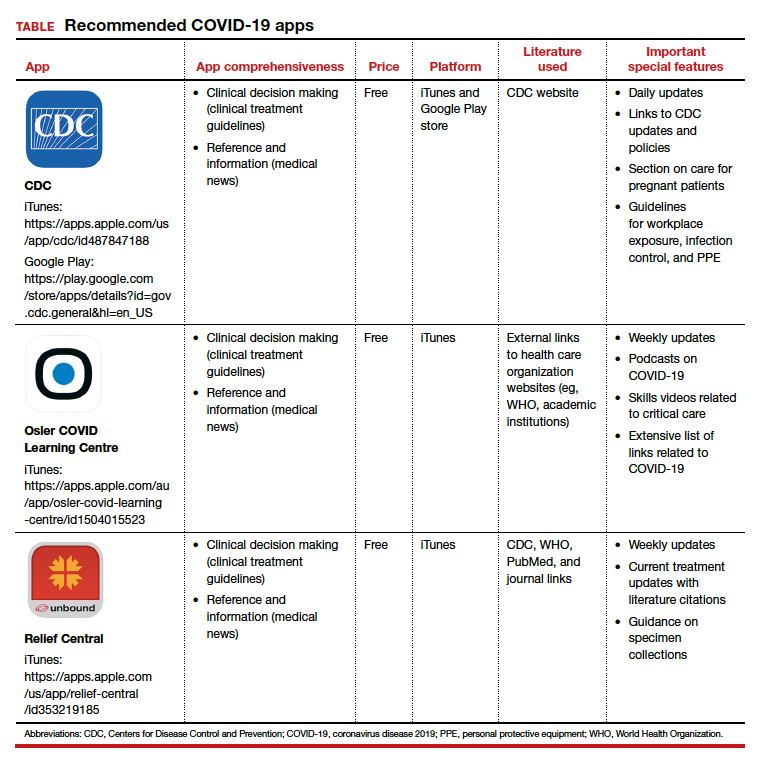

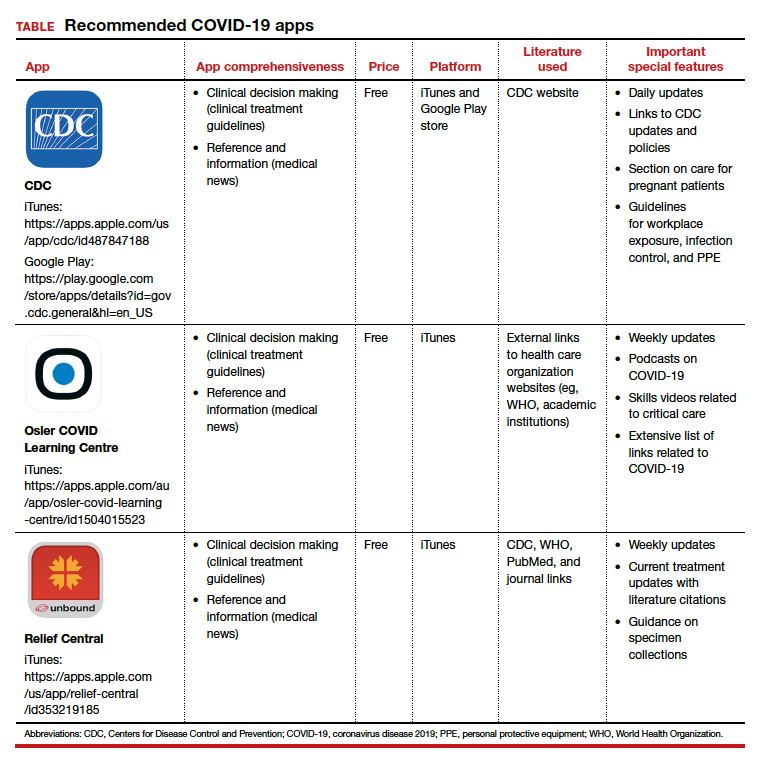

COVID-19 apps for the ObGyn health care provider: An update

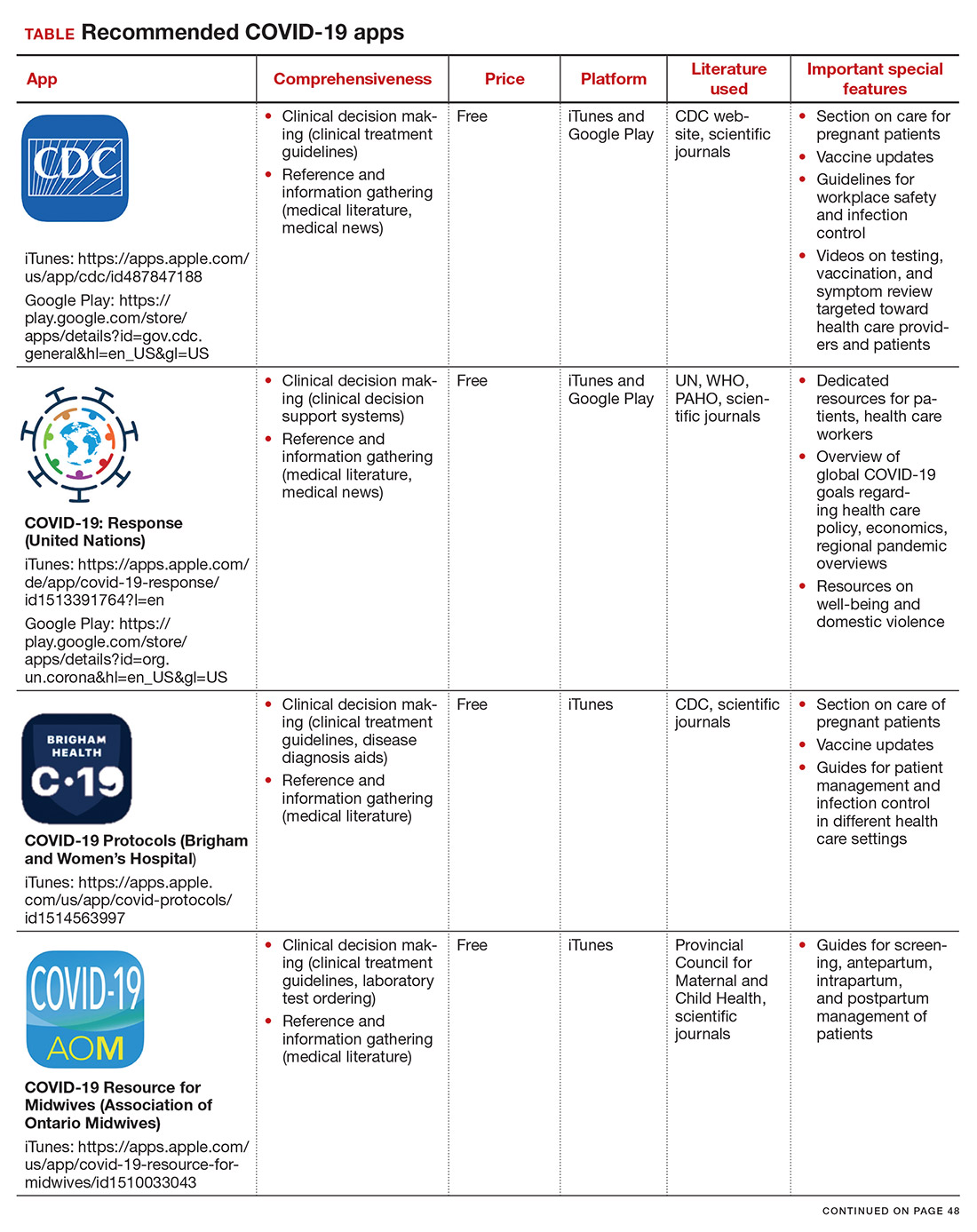

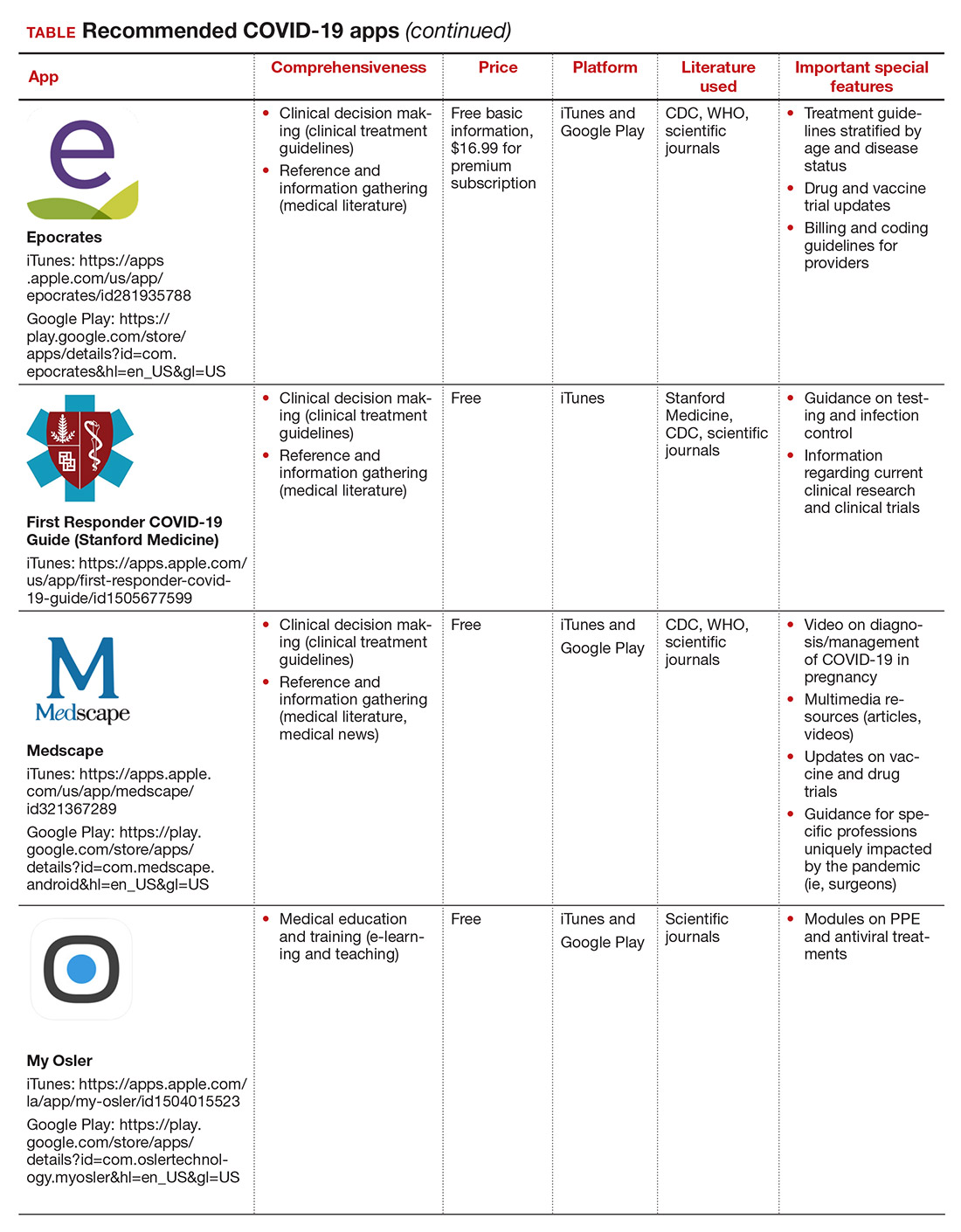

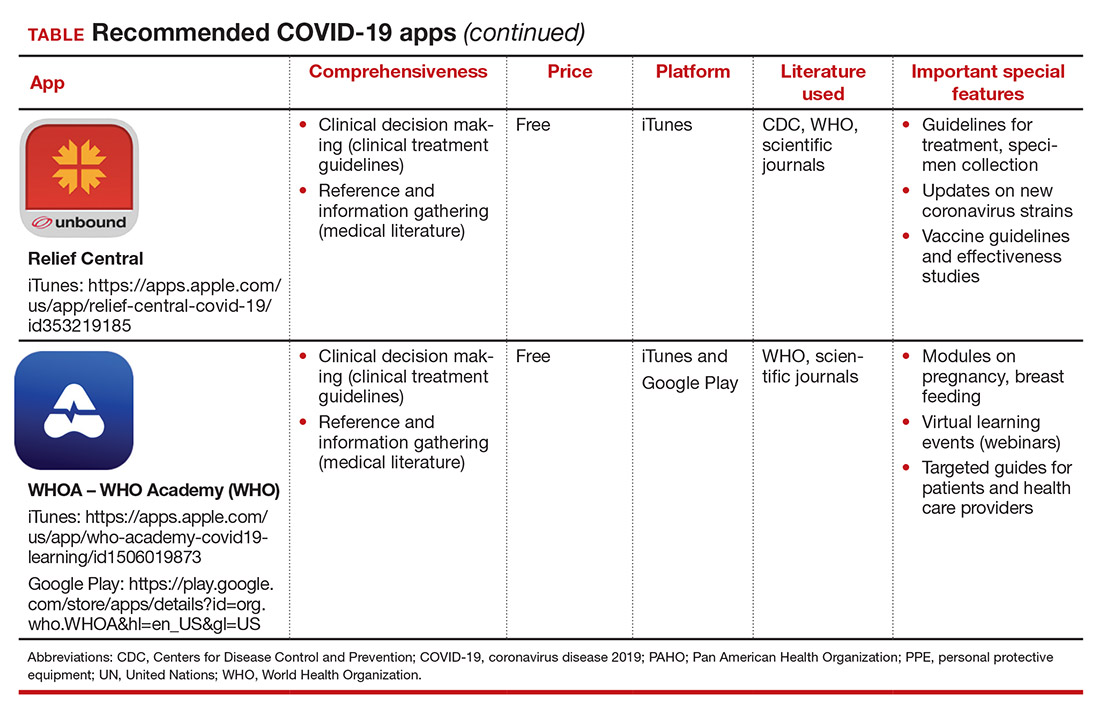

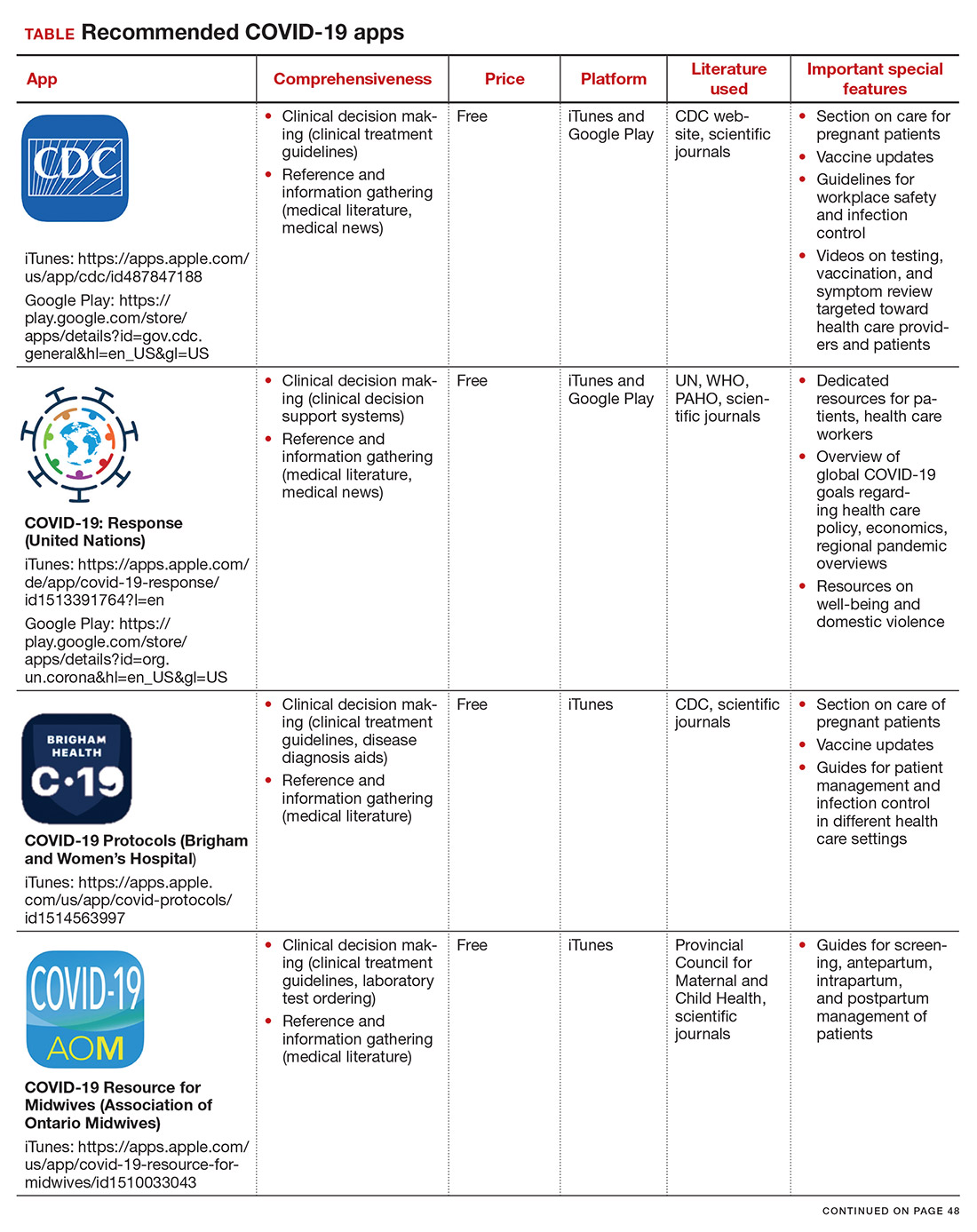

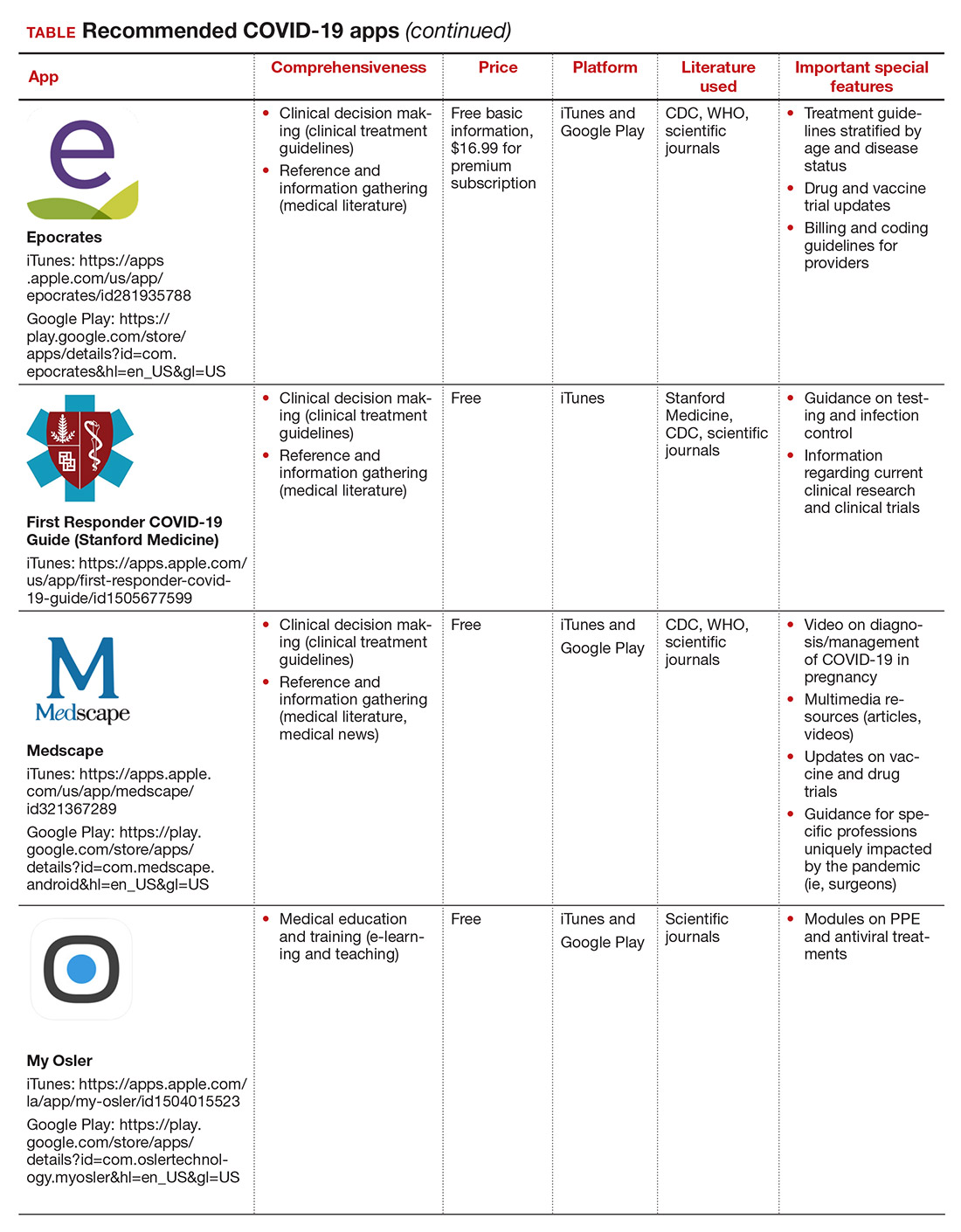

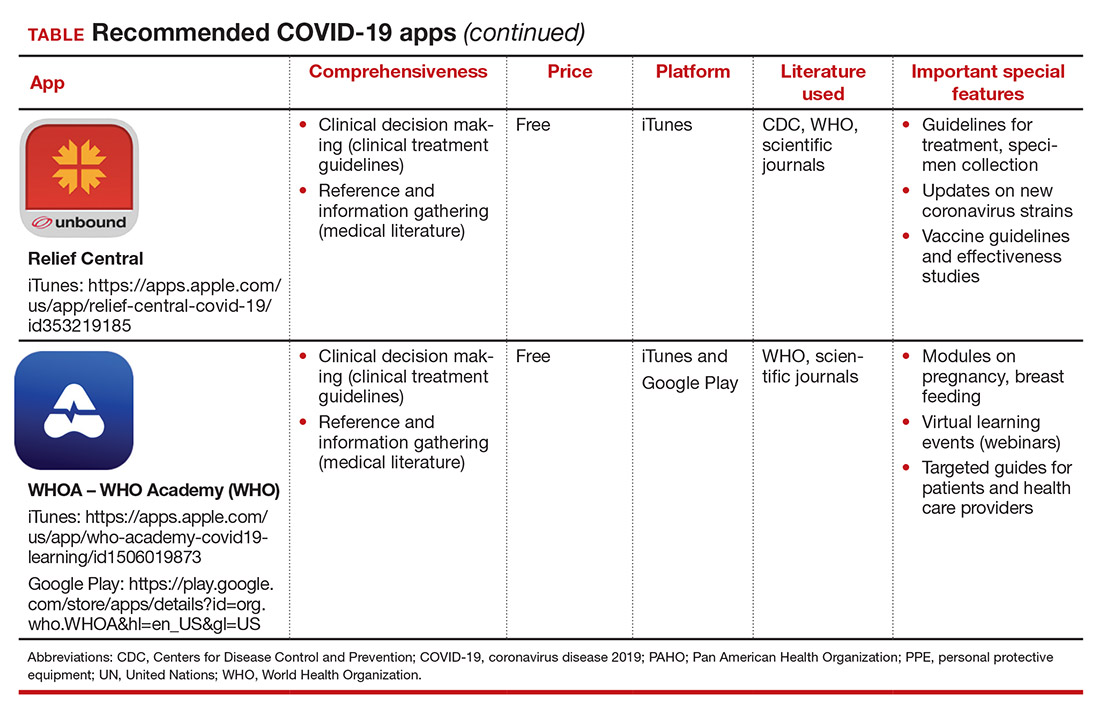

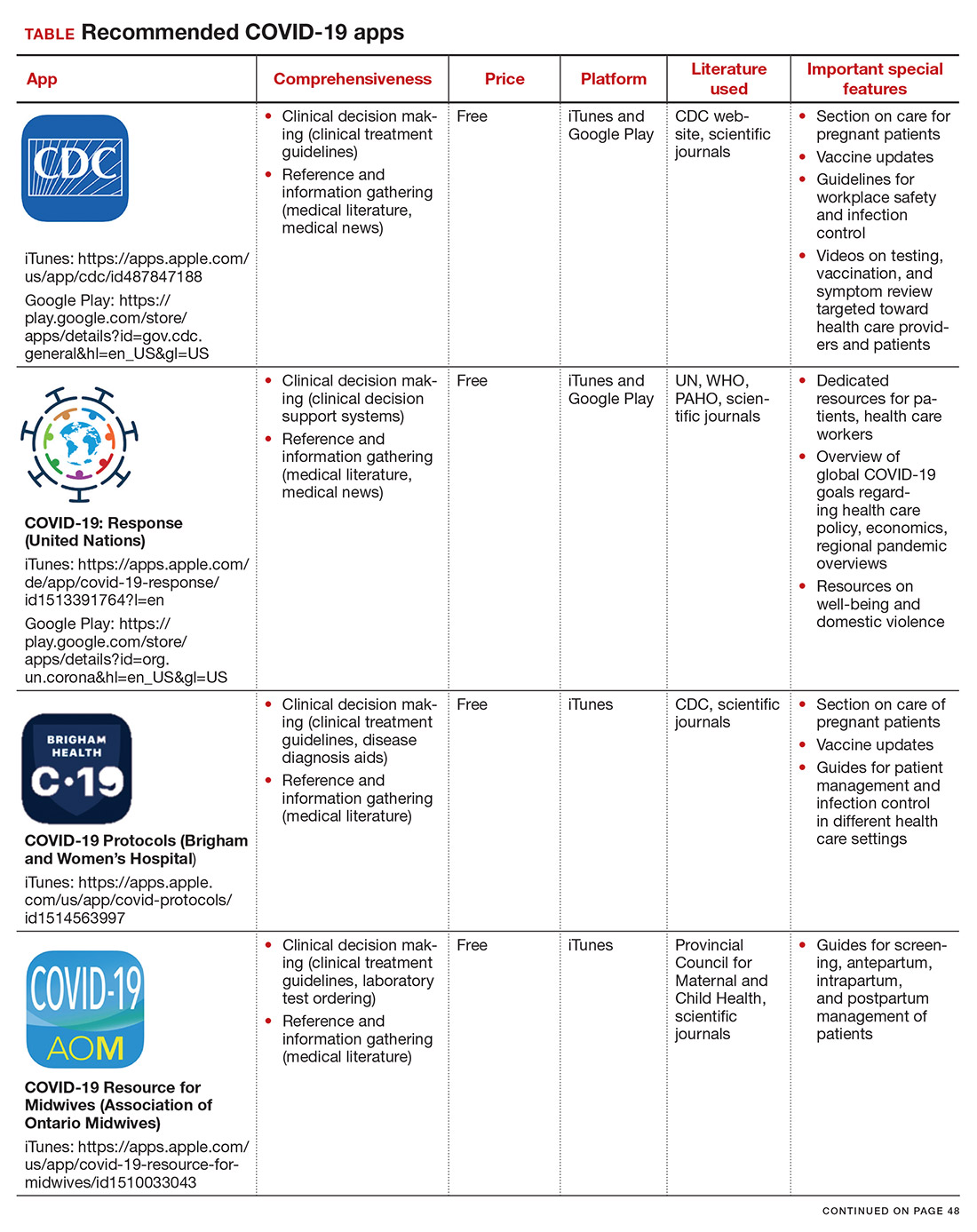

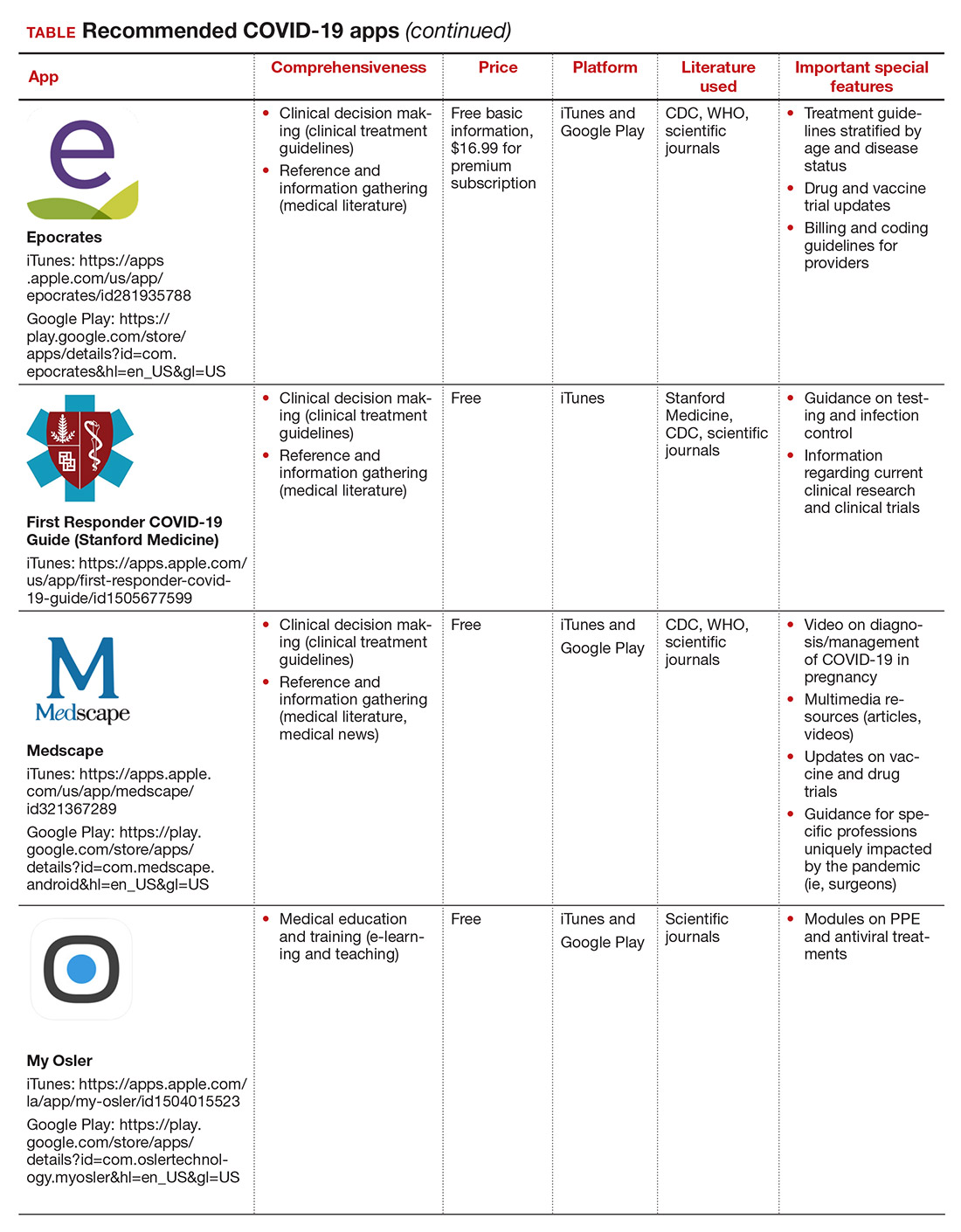

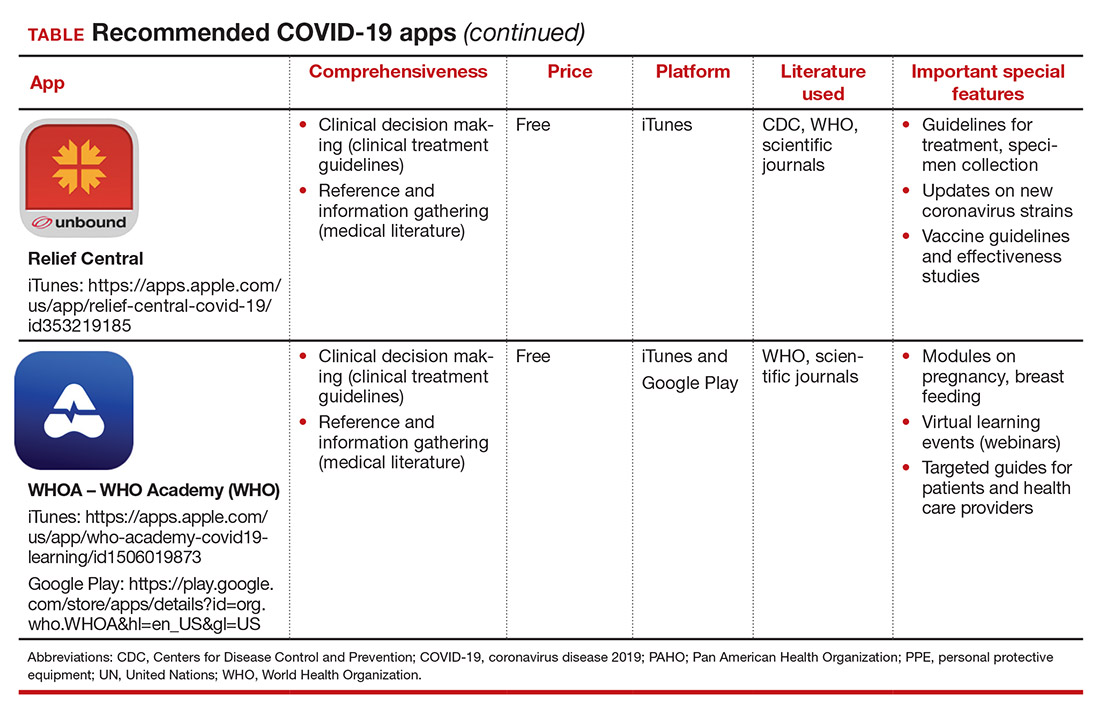

More than one year after COVID-19 was declared a worldwide pandemic by the World Health Organization on March 11, 2020, the disease continues to persist, infecting more than 110 million individuals to date globally.1 As new information emerges about the coronavirus, the literature on diagnosis and management also has grown exponentially over the last year, including specific guidance for obstetric populations. With abundant information available to health care providers, COVID-19 mobile apps have the advantage of summarizing and presenting information in an organized and easily accessible manner.2

This updated review expands on a previous article by Bogaert and Chen at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic.3 Using the same methodology, in March 2021 we searched the Apple iTunes and Google Play stores using the term “COVID.” The search yielded 230 unique applications available for download. We excluded apps that were primarily developed as geographic area-specific case trackers or personal symptom trackers (193), those that provide telemedicine services (7), and nonmedical apps or ones published in a language other than English (20).

Here, we focus on the 3 mobile apps previously discussed (CDC, My Osler, and Relief Central) and 7 additional apps (TABLE). Most summarize information on the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of coronavirus, and several also provide information on the COVID-19 vaccine. One app (COVID-19 Resource for Midwives) is specifically designed for obstetric providers, and 4 others (CDC, COVID-19 Protocols, Medscape, and WHO Academy) contain information on specific guidance for obstetric and gynecologic patient populations.

Each app was evaluated based on a condensed version of the APPLICATIONS scoring system, APPLI (comprehensiveness, price, platform, literature used, and special features).4

We hope that these mobile apps will assist the ObGyn health care provider in continuing to care for patients during this pandemic.

- World Health Organization. WHO coronavirus (COVID-19) dashboard. https://covid19.who.int/. Accessed March 12, 2021.

2. Kondylakis H, Katehakis DG, Kouroubali A, et al. COVID-19 mobile apps: a systematic review of the literature. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22:e23170.

3. Bogaert K, Chen KT. COVID-19 apps for the ObGyn health care provider. OBG Manag. 2020; 32(5):44, 46.

4. Chyjek K, Farag S, Chen KT. Rating pregnancy wheel applications using the APPLICATIONS scoring system. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:1478-1483.

More than one year after COVID-19 was declared a worldwide pandemic by the World Health Organization on March 11, 2020, the disease continues to persist, infecting more than 110 million individuals to date globally.1 As new information emerges about the coronavirus, the literature on diagnosis and management also has grown exponentially over the last year, including specific guidance for obstetric populations. With abundant information available to health care providers, COVID-19 mobile apps have the advantage of summarizing and presenting information in an organized and easily accessible manner.2

This updated review expands on a previous article by Bogaert and Chen at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic.3 Using the same methodology, in March 2021 we searched the Apple iTunes and Google Play stores using the term “COVID.” The search yielded 230 unique applications available for download. We excluded apps that were primarily developed as geographic area-specific case trackers or personal symptom trackers (193), those that provide telemedicine services (7), and nonmedical apps or ones published in a language other than English (20).

Here, we focus on the 3 mobile apps previously discussed (CDC, My Osler, and Relief Central) and 7 additional apps (TABLE). Most summarize information on the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of coronavirus, and several also provide information on the COVID-19 vaccine. One app (COVID-19 Resource for Midwives) is specifically designed for obstetric providers, and 4 others (CDC, COVID-19 Protocols, Medscape, and WHO Academy) contain information on specific guidance for obstetric and gynecologic patient populations.

Each app was evaluated based on a condensed version of the APPLICATIONS scoring system, APPLI (comprehensiveness, price, platform, literature used, and special features).4

We hope that these mobile apps will assist the ObGyn health care provider in continuing to care for patients during this pandemic.

More than one year after COVID-19 was declared a worldwide pandemic by the World Health Organization on March 11, 2020, the disease continues to persist, infecting more than 110 million individuals to date globally.1 As new information emerges about the coronavirus, the literature on diagnosis and management also has grown exponentially over the last year, including specific guidance for obstetric populations. With abundant information available to health care providers, COVID-19 mobile apps have the advantage of summarizing and presenting information in an organized and easily accessible manner.2

This updated review expands on a previous article by Bogaert and Chen at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic.3 Using the same methodology, in March 2021 we searched the Apple iTunes and Google Play stores using the term “COVID.” The search yielded 230 unique applications available for download. We excluded apps that were primarily developed as geographic area-specific case trackers or personal symptom trackers (193), those that provide telemedicine services (7), and nonmedical apps or ones published in a language other than English (20).

Here, we focus on the 3 mobile apps previously discussed (CDC, My Osler, and Relief Central) and 7 additional apps (TABLE). Most summarize information on the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of coronavirus, and several also provide information on the COVID-19 vaccine. One app (COVID-19 Resource for Midwives) is specifically designed for obstetric providers, and 4 others (CDC, COVID-19 Protocols, Medscape, and WHO Academy) contain information on specific guidance for obstetric and gynecologic patient populations.

Each app was evaluated based on a condensed version of the APPLICATIONS scoring system, APPLI (comprehensiveness, price, platform, literature used, and special features).4

We hope that these mobile apps will assist the ObGyn health care provider in continuing to care for patients during this pandemic.

- World Health Organization. WHO coronavirus (COVID-19) dashboard. https://covid19.who.int/. Accessed March 12, 2021.

2. Kondylakis H, Katehakis DG, Kouroubali A, et al. COVID-19 mobile apps: a systematic review of the literature. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22:e23170.

3. Bogaert K, Chen KT. COVID-19 apps for the ObGyn health care provider. OBG Manag. 2020; 32(5):44, 46.

4. Chyjek K, Farag S, Chen KT. Rating pregnancy wheel applications using the APPLICATIONS scoring system. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:1478-1483.

- World Health Organization. WHO coronavirus (COVID-19) dashboard. https://covid19.who.int/. Accessed March 12, 2021.

2. Kondylakis H, Katehakis DG, Kouroubali A, et al. COVID-19 mobile apps: a systematic review of the literature. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22:e23170.

3. Bogaert K, Chen KT. COVID-19 apps for the ObGyn health care provider. OBG Manag. 2020; 32(5):44, 46.

4. Chyjek K, Farag S, Chen KT. Rating pregnancy wheel applications using the APPLICATIONS scoring system. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:1478-1483.

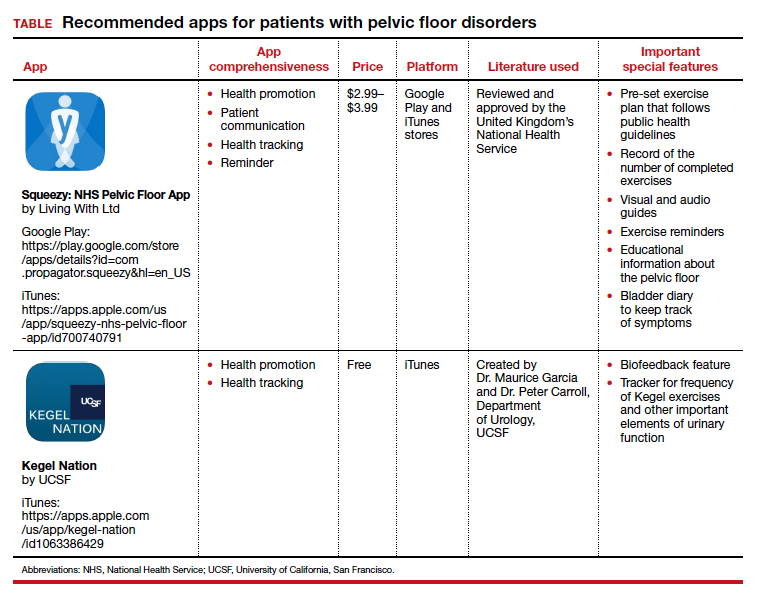

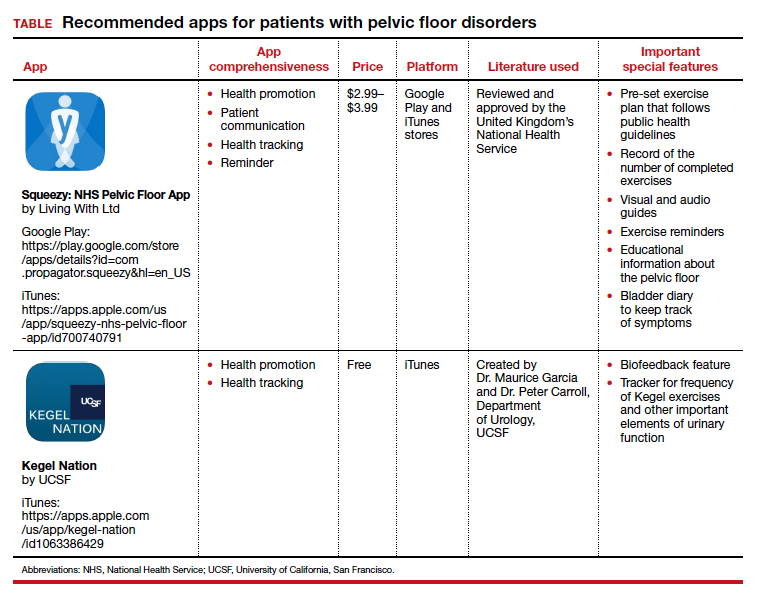

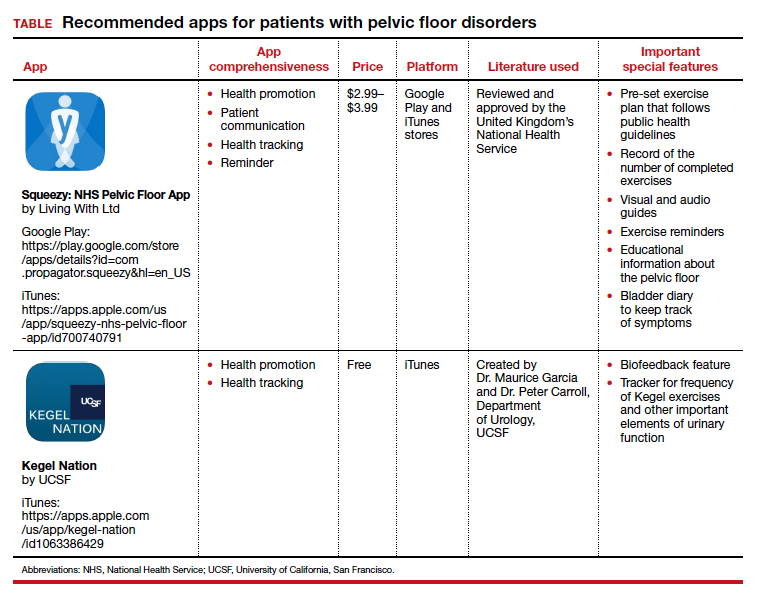

Two at-home apps for patients with pelvic floor disorders

In the “You asked, Dr. Jen Gunter answered” series in The New York Times, Dr. Gunter writes that “pelvic floor exercises (also known as Kegel exercises) can be very helpful for urinary incontinence, pelvic organ prolapse, and fecal incontinence.” She continues to say that “pelvic floor exercises can be hard to master correctly, so it is important to make sure [one has] the correct technique. Many women can learn to do them after reading instructions like the ones found at the National Association for Continence, but some women may need their technique checked by their doctor, or help from a specialized pelvic floor physical therapist.”1

Similarly, Sudol and colleagues write that “guidelines from multiple medical societies emphasize the importance of patient education, behavioral therapy, and/or exercise regimens in the initial treatment and management of women with pelvic floor disorders. However, even with well-established recommendations, engaging patients and maintaining adherence to treatment plans and unmonitored programs at home are often difficult.”2 To help patients, those authors identified and evaluated patient-centered apps on topics in female pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgery.2

Two apps that assist patients in Kegel exercises are presented here. The Squeezy app includes guided pelvic floor muscle exercises with reminders, and the Kegel Nation app has a biofeedback feature.

The TABLE details the features of the 2 apps based on a shortened version of the APPLICATIONS scoring system, APPLI (app comprehensiveness, price, platform, literature used, and important special features).3

I hope clinicians find these apps helpful to their patients with pelvic floor disorders.

- Gunter J. You asked, Dr. Jen Gunter answered. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/ask/answers/kegels-pelvic-floor-exercises-yoni-eggs. Accessed December 22, 2020.

- Sudol NT, Adams-Piper E, Perry R, et al. In search of mobile applications for patients with pelvic floor disorders. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2019;25:252-256.

- Chyjek K, Farag S, Chen KT. Rating pregnancy wheel applications using the APPLICATIONS scoring system. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:1478-1483.

In the “You asked, Dr. Jen Gunter answered” series in The New York Times, Dr. Gunter writes that “pelvic floor exercises (also known as Kegel exercises) can be very helpful for urinary incontinence, pelvic organ prolapse, and fecal incontinence.” She continues to say that “pelvic floor exercises can be hard to master correctly, so it is important to make sure [one has] the correct technique. Many women can learn to do them after reading instructions like the ones found at the National Association for Continence, but some women may need their technique checked by their doctor, or help from a specialized pelvic floor physical therapist.”1

Similarly, Sudol and colleagues write that “guidelines from multiple medical societies emphasize the importance of patient education, behavioral therapy, and/or exercise regimens in the initial treatment and management of women with pelvic floor disorders. However, even with well-established recommendations, engaging patients and maintaining adherence to treatment plans and unmonitored programs at home are often difficult.”2 To help patients, those authors identified and evaluated patient-centered apps on topics in female pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgery.2

Two apps that assist patients in Kegel exercises are presented here. The Squeezy app includes guided pelvic floor muscle exercises with reminders, and the Kegel Nation app has a biofeedback feature.

The TABLE details the features of the 2 apps based on a shortened version of the APPLICATIONS scoring system, APPLI (app comprehensiveness, price, platform, literature used, and important special features).3

I hope clinicians find these apps helpful to their patients with pelvic floor disorders.

In the “You asked, Dr. Jen Gunter answered” series in The New York Times, Dr. Gunter writes that “pelvic floor exercises (also known as Kegel exercises) can be very helpful for urinary incontinence, pelvic organ prolapse, and fecal incontinence.” She continues to say that “pelvic floor exercises can be hard to master correctly, so it is important to make sure [one has] the correct technique. Many women can learn to do them after reading instructions like the ones found at the National Association for Continence, but some women may need their technique checked by their doctor, or help from a specialized pelvic floor physical therapist.”1

Similarly, Sudol and colleagues write that “guidelines from multiple medical societies emphasize the importance of patient education, behavioral therapy, and/or exercise regimens in the initial treatment and management of women with pelvic floor disorders. However, even with well-established recommendations, engaging patients and maintaining adherence to treatment plans and unmonitored programs at home are often difficult.”2 To help patients, those authors identified and evaluated patient-centered apps on topics in female pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgery.2

Two apps that assist patients in Kegel exercises are presented here. The Squeezy app includes guided pelvic floor muscle exercises with reminders, and the Kegel Nation app has a biofeedback feature.

The TABLE details the features of the 2 apps based on a shortened version of the APPLICATIONS scoring system, APPLI (app comprehensiveness, price, platform, literature used, and important special features).3

I hope clinicians find these apps helpful to their patients with pelvic floor disorders.

- Gunter J. You asked, Dr. Jen Gunter answered. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/ask/answers/kegels-pelvic-floor-exercises-yoni-eggs. Accessed December 22, 2020.

- Sudol NT, Adams-Piper E, Perry R, et al. In search of mobile applications for patients with pelvic floor disorders. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2019;25:252-256.

- Chyjek K, Farag S, Chen KT. Rating pregnancy wheel applications using the APPLICATIONS scoring system. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:1478-1483.

- Gunter J. You asked, Dr. Jen Gunter answered. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/ask/answers/kegels-pelvic-floor-exercises-yoni-eggs. Accessed December 22, 2020.

- Sudol NT, Adams-Piper E, Perry R, et al. In search of mobile applications for patients with pelvic floor disorders. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2019;25:252-256.

- Chyjek K, Farag S, Chen KT. Rating pregnancy wheel applications using the APPLICATIONS scoring system. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:1478-1483.

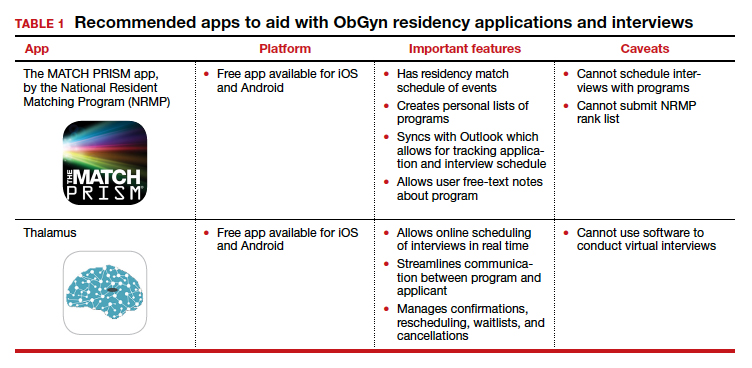

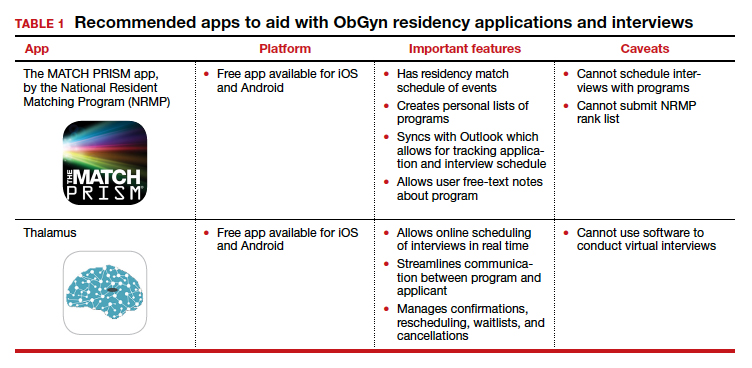

Apps for applying to ObGyn residency programs in the era of virtual interviews

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has upended the traditional 2020–2021 application season for ObGyn residency programs. In May 2020, the 2 national ObGyn education organizations, the Association of Professors of Gynecology and Obstetrics (APGO) and Council on Resident Education in ObGyn (CREOG), issued guidelines to ensure a fair and equitable application process.1 These guidelines are consistent with recommendations from the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) and the Coalition for Physician Accountability. Important recommendations include:

- limiting away rotations

- being flexible in the number of specialty-specific letters of recommendation required

- encouraging residency programs to develop alternate means of conveying information about their curriculum.

In addition, these statements provide timing on when programs should release interview offers and when to begin interviews. Finally, programs are required to commit to online interviews and virtual visits for all applicants, including local students, rather than in-person interviews.

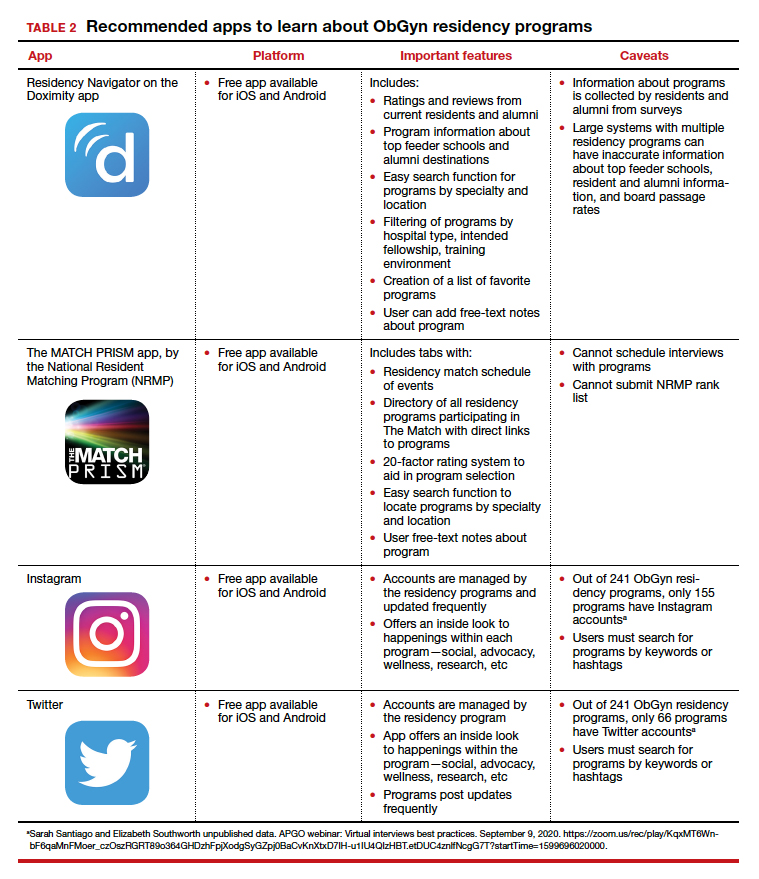

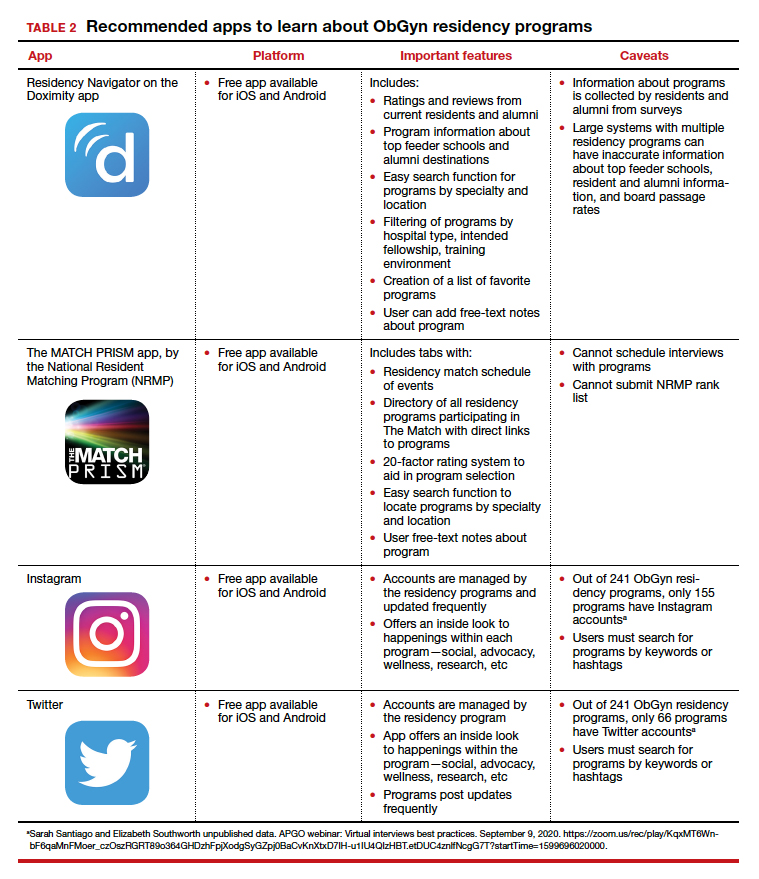

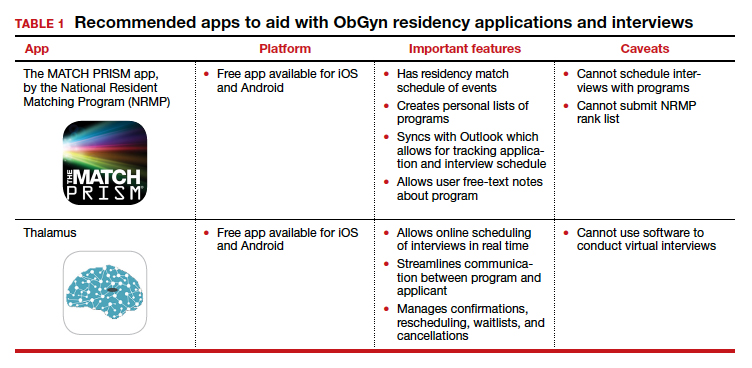

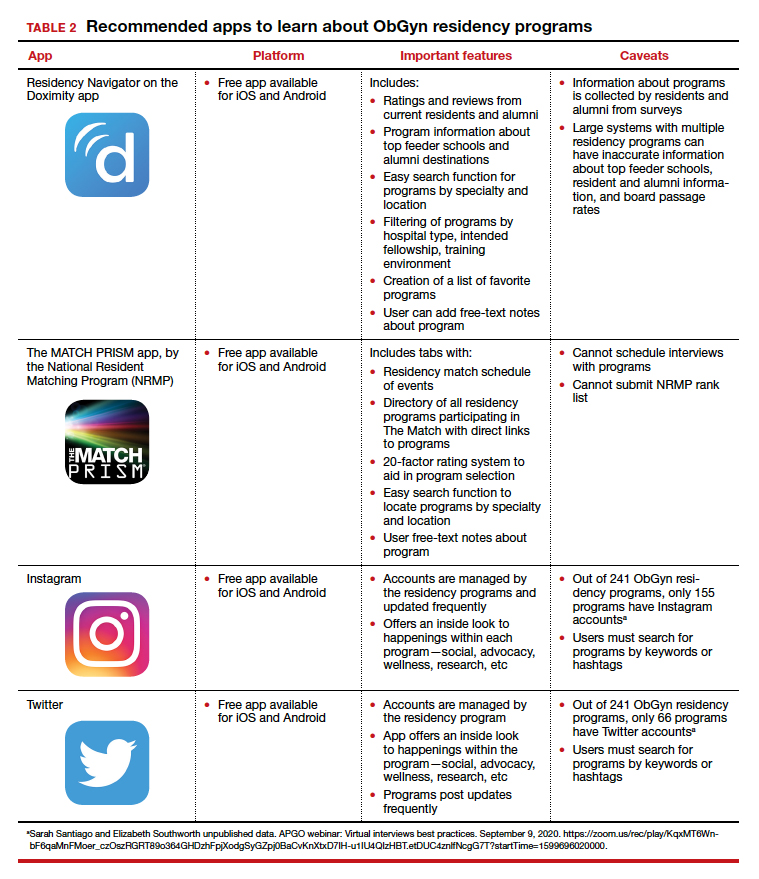

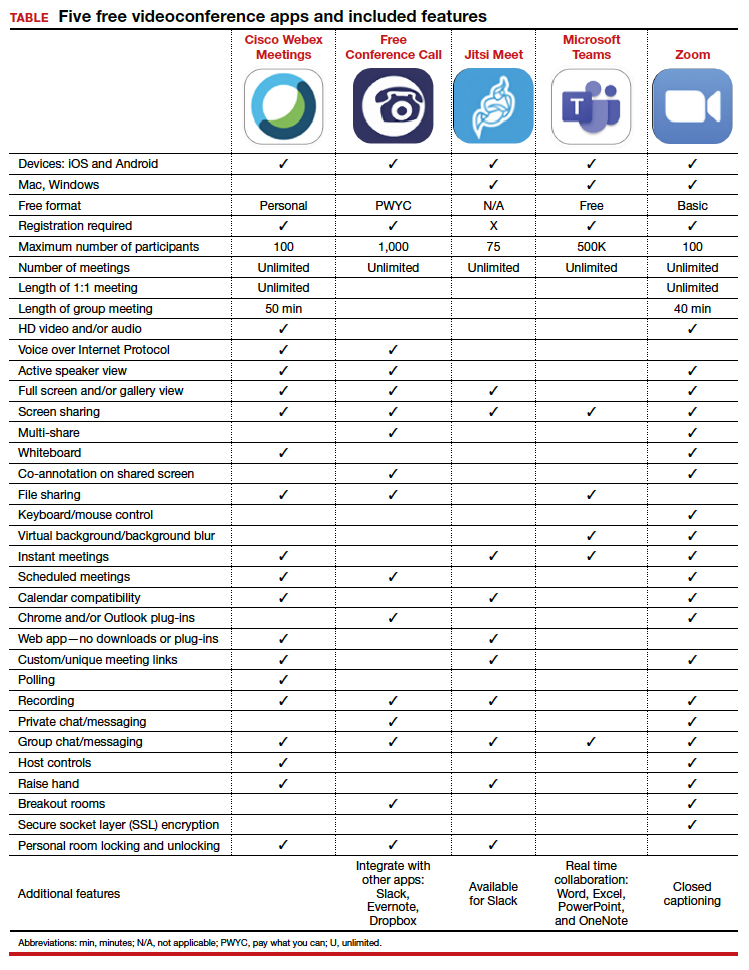

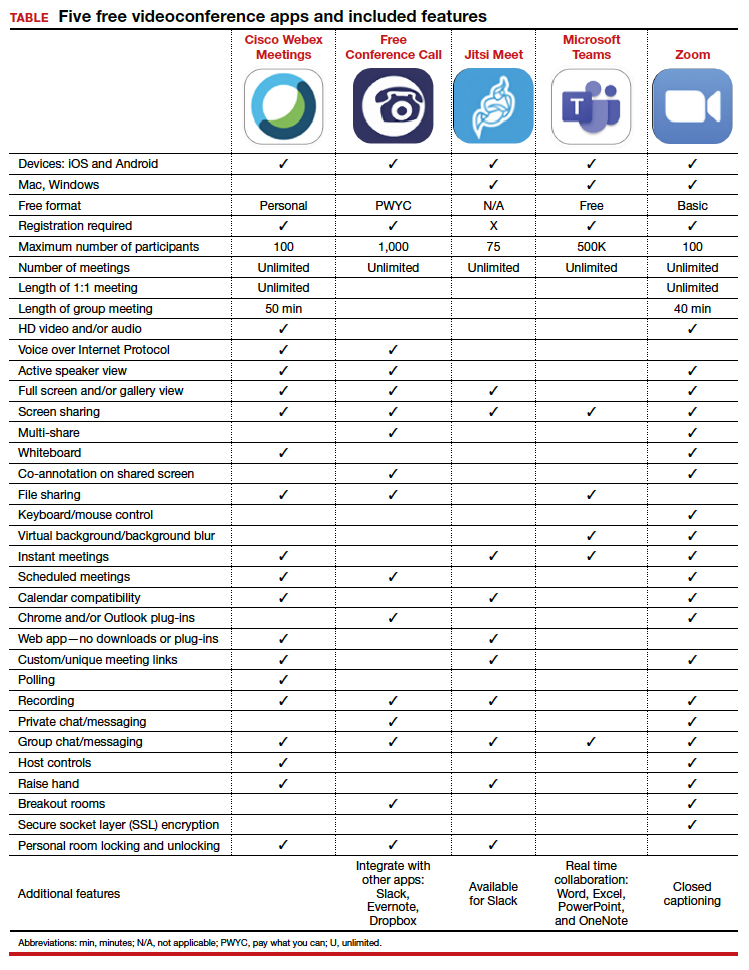

Here, we focus on identifying apps that students can use to help them with the application process—apps for the nuts and bolts of applying and interviewing and apps to learn more about individual programs.

Students must use the Electronic Residency Application Service (ERAS) platform from AAMC to enter their information and register with the National Resident Matching Program (NRMP). Students also must use the ERAS to submit their applications to their selected residency programs. The ERAS platform does not include an app to aid in the completion or submission of an application. The NRMP has developed the MATCH PRISM app, but this does not allow students to register for the match or submit their rank list. To learn about how to schedule interviews, residency programs may use one of the following sources: ERAS, Interview Broker, or Thalamus. Moreover, APGO/CREOG has partnered with Thalamus for the upcoming application cycle, which provides residency programs and applicants tools for application management, interview scheduling, and itinerary building. Thalamus offers a free app.

This year offers some unique challenges. The application process for ObGyn residencies is likely to be more competitive, and students face the added stress of having to navigate the interview season:

- without away rotations (audition interviews)

- without in-person visits of the city/hospital/program or social events before or after interview day

- with an all-virtual interview day.

Continue to: To find information on individual residency programs...

To find information on individual residency programs, the APGO website lists the FREIDA and APGO Residency Directories, which are not apps. Students are also aware of the Doximity Residency Navigator, which does include an app. The NRMP MATCH PRISM app is another resource, as it provides students with a directory of residency programs and information about each program.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recognizes that residency program websites and social media will be crucial in helping applicants learn about individual programs, faculty, and residents. As such, ACOG hosted a Virtual Residency Showcase in September 2020 in which programs posted content on Instagram and Twitter using the hashtag #ACOG-ResWeek20.2 Similarly, APGO and CREOG produced a report containing a social media directory, which lists individual residency programs and whether or not they have a social media handle/account.3 In a recent webinar,4 Drs. Sarah Santiago and Elizabeth Southworth noted that the number of residency programs that have an Instagram account more than doubled (from 60 to 128) between May and September 2020.

We present 2 tables describing the important features and caveats of apps available to students to assist them with residency applications this year—TABLE 1 summarizes apps to aid with applications and interviews; TABLE 2 lists apps designed for students to learn more about individual residency programs. We wish all of this year’s students every success in their search for the right program. ●

- Association of Professors of Gynecology and Obstetrics, Council on Resident Education in ObGyn. Updated APGO and CREOG Residency Application Response to COVID-19. https://www.apgo.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05 /Updated-APGO-CREOG-Residency-Response-to -COVID-19-.pdf. Accessed October 27, 2020.

- https://www.acog.org/education-and-events/webinars /virtual-residency-showcase. Accessed October 4, 2020.

- Social media directory-ObGyn. https://docs.google.com /spreadsheets/d/e/2PACX-1vQ6boyn7FWV9tEhfQp1o3 XJgNIPNBQ3qCYf4IpV-rOPcd212J-HNR84p0r85nXrAz MvOmcNlgjywDP/pubhtml?gid=1472916499&single =true. Accessed October 27, 2020.

- APGO webinar: Virtual interviews best practices. September 9, 2020. https://zoom.us/rec/play/KqxMT6Wnb F6qaMnFMoer_czOszRGRT89o364GHDzhFpjXodgSyGZpj 0BaCvKnXtxD7IH-u1IU4QIzHBT.etDUC4znlfNcgG7T?start Time=1599696020000. Accessed October 4, 2020.

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has upended the traditional 2020–2021 application season for ObGyn residency programs. In May 2020, the 2 national ObGyn education organizations, the Association of Professors of Gynecology and Obstetrics (APGO) and Council on Resident Education in ObGyn (CREOG), issued guidelines to ensure a fair and equitable application process.1 These guidelines are consistent with recommendations from the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) and the Coalition for Physician Accountability. Important recommendations include:

- limiting away rotations

- being flexible in the number of specialty-specific letters of recommendation required

- encouraging residency programs to develop alternate means of conveying information about their curriculum.

In addition, these statements provide timing on when programs should release interview offers and when to begin interviews. Finally, programs are required to commit to online interviews and virtual visits for all applicants, including local students, rather than in-person interviews.

Here, we focus on identifying apps that students can use to help them with the application process—apps for the nuts and bolts of applying and interviewing and apps to learn more about individual programs.

Students must use the Electronic Residency Application Service (ERAS) platform from AAMC to enter their information and register with the National Resident Matching Program (NRMP). Students also must use the ERAS to submit their applications to their selected residency programs. The ERAS platform does not include an app to aid in the completion or submission of an application. The NRMP has developed the MATCH PRISM app, but this does not allow students to register for the match or submit their rank list. To learn about how to schedule interviews, residency programs may use one of the following sources: ERAS, Interview Broker, or Thalamus. Moreover, APGO/CREOG has partnered with Thalamus for the upcoming application cycle, which provides residency programs and applicants tools for application management, interview scheduling, and itinerary building. Thalamus offers a free app.

This year offers some unique challenges. The application process for ObGyn residencies is likely to be more competitive, and students face the added stress of having to navigate the interview season:

- without away rotations (audition interviews)

- without in-person visits of the city/hospital/program or social events before or after interview day

- with an all-virtual interview day.

Continue to: To find information on individual residency programs...

To find information on individual residency programs, the APGO website lists the FREIDA and APGO Residency Directories, which are not apps. Students are also aware of the Doximity Residency Navigator, which does include an app. The NRMP MATCH PRISM app is another resource, as it provides students with a directory of residency programs and information about each program.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recognizes that residency program websites and social media will be crucial in helping applicants learn about individual programs, faculty, and residents. As such, ACOG hosted a Virtual Residency Showcase in September 2020 in which programs posted content on Instagram and Twitter using the hashtag #ACOG-ResWeek20.2 Similarly, APGO and CREOG produced a report containing a social media directory, which lists individual residency programs and whether or not they have a social media handle/account.3 In a recent webinar,4 Drs. Sarah Santiago and Elizabeth Southworth noted that the number of residency programs that have an Instagram account more than doubled (from 60 to 128) between May and September 2020.

We present 2 tables describing the important features and caveats of apps available to students to assist them with residency applications this year—TABLE 1 summarizes apps to aid with applications and interviews; TABLE 2 lists apps designed for students to learn more about individual residency programs. We wish all of this year’s students every success in their search for the right program. ●

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has upended the traditional 2020–2021 application season for ObGyn residency programs. In May 2020, the 2 national ObGyn education organizations, the Association of Professors of Gynecology and Obstetrics (APGO) and Council on Resident Education in ObGyn (CREOG), issued guidelines to ensure a fair and equitable application process.1 These guidelines are consistent with recommendations from the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) and the Coalition for Physician Accountability. Important recommendations include:

- limiting away rotations

- being flexible in the number of specialty-specific letters of recommendation required

- encouraging residency programs to develop alternate means of conveying information about their curriculum.

In addition, these statements provide timing on when programs should release interview offers and when to begin interviews. Finally, programs are required to commit to online interviews and virtual visits for all applicants, including local students, rather than in-person interviews.

Here, we focus on identifying apps that students can use to help them with the application process—apps for the nuts and bolts of applying and interviewing and apps to learn more about individual programs.

Students must use the Electronic Residency Application Service (ERAS) platform from AAMC to enter their information and register with the National Resident Matching Program (NRMP). Students also must use the ERAS to submit their applications to their selected residency programs. The ERAS platform does not include an app to aid in the completion or submission of an application. The NRMP has developed the MATCH PRISM app, but this does not allow students to register for the match or submit their rank list. To learn about how to schedule interviews, residency programs may use one of the following sources: ERAS, Interview Broker, or Thalamus. Moreover, APGO/CREOG has partnered with Thalamus for the upcoming application cycle, which provides residency programs and applicants tools for application management, interview scheduling, and itinerary building. Thalamus offers a free app.

This year offers some unique challenges. The application process for ObGyn residencies is likely to be more competitive, and students face the added stress of having to navigate the interview season:

- without away rotations (audition interviews)

- without in-person visits of the city/hospital/program or social events before or after interview day

- with an all-virtual interview day.

Continue to: To find information on individual residency programs...

To find information on individual residency programs, the APGO website lists the FREIDA and APGO Residency Directories, which are not apps. Students are also aware of the Doximity Residency Navigator, which does include an app. The NRMP MATCH PRISM app is another resource, as it provides students with a directory of residency programs and information about each program.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recognizes that residency program websites and social media will be crucial in helping applicants learn about individual programs, faculty, and residents. As such, ACOG hosted a Virtual Residency Showcase in September 2020 in which programs posted content on Instagram and Twitter using the hashtag #ACOG-ResWeek20.2 Similarly, APGO and CREOG produced a report containing a social media directory, which lists individual residency programs and whether or not they have a social media handle/account.3 In a recent webinar,4 Drs. Sarah Santiago and Elizabeth Southworth noted that the number of residency programs that have an Instagram account more than doubled (from 60 to 128) between May and September 2020.

We present 2 tables describing the important features and caveats of apps available to students to assist them with residency applications this year—TABLE 1 summarizes apps to aid with applications and interviews; TABLE 2 lists apps designed for students to learn more about individual residency programs. We wish all of this year’s students every success in their search for the right program. ●

- Association of Professors of Gynecology and Obstetrics, Council on Resident Education in ObGyn. Updated APGO and CREOG Residency Application Response to COVID-19. https://www.apgo.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05 /Updated-APGO-CREOG-Residency-Response-to -COVID-19-.pdf. Accessed October 27, 2020.

- https://www.acog.org/education-and-events/webinars /virtual-residency-showcase. Accessed October 4, 2020.

- Social media directory-ObGyn. https://docs.google.com /spreadsheets/d/e/2PACX-1vQ6boyn7FWV9tEhfQp1o3 XJgNIPNBQ3qCYf4IpV-rOPcd212J-HNR84p0r85nXrAz MvOmcNlgjywDP/pubhtml?gid=1472916499&single =true. Accessed October 27, 2020.

- APGO webinar: Virtual interviews best practices. September 9, 2020. https://zoom.us/rec/play/KqxMT6Wnb F6qaMnFMoer_czOszRGRT89o364GHDzhFpjXodgSyGZpj 0BaCvKnXtxD7IH-u1IU4QIzHBT.etDUC4znlfNcgG7T?start Time=1599696020000. Accessed October 4, 2020.

- Association of Professors of Gynecology and Obstetrics, Council on Resident Education in ObGyn. Updated APGO and CREOG Residency Application Response to COVID-19. https://www.apgo.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05 /Updated-APGO-CREOG-Residency-Response-to -COVID-19-.pdf. Accessed October 27, 2020.