User login

Exophytic Tumor on the Buttock

The Diagnosis: Hidradenocarcinoma

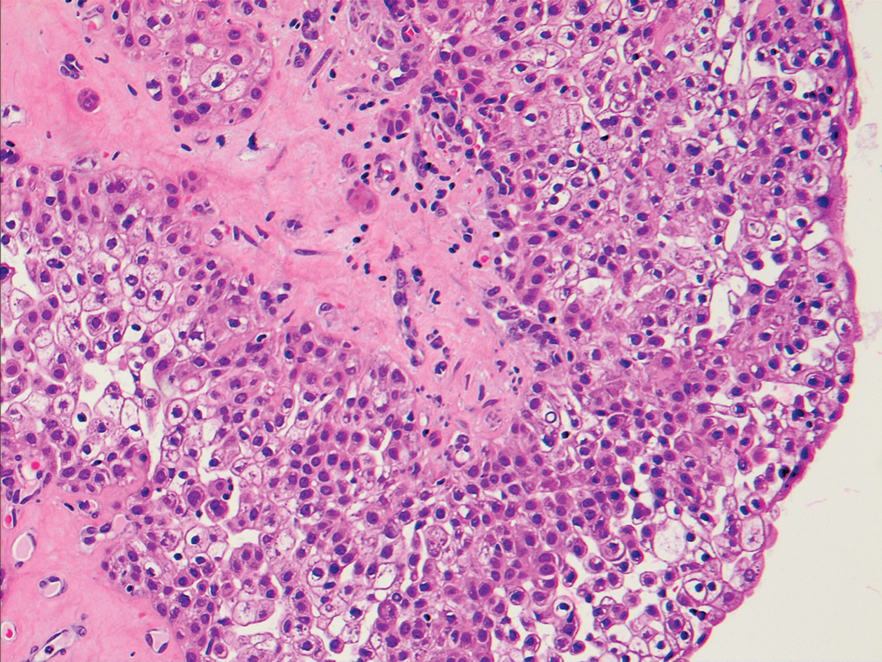

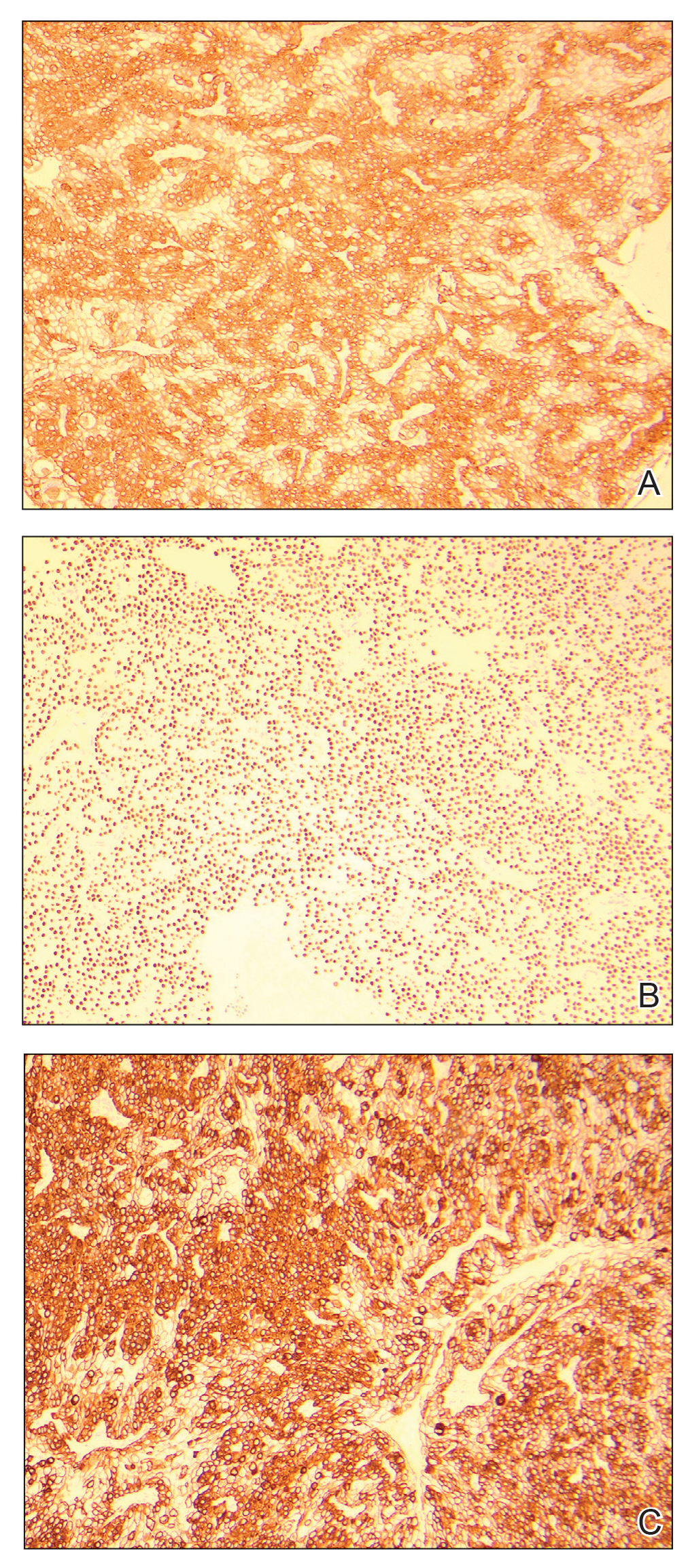

An excisional biopsy revealed a neoplasm in the dermis with focal invasion into the adjacent soft tissue (Figure 1). The tumor consisted of sheets of cells with cytoplasmic vacuoles and ductal differentiation (Figure 2), as well as cells with mild atypia, mild pleomorphism, rare mitotic figures, and abundant pale cytoplasm. Immunohistochemical staining was positive for cytokeratin (CK) 5, CK7, CK20, CK AE1/AE3, and p63 (Figure 3). The culmination of features including the large tumor size, immunohistochemical staining pattern, and mild pleomorphism with focal invasion into the soft tissue supported the diagnosis of hidradenocarcinoma.

Hidradenocarcinoma is an exceedingly rare malignant tumor of eccrine and/or apocrine origin.1 It accounts for less than 0.001% of all tumors and 1 of 13,000 skin biopsies.2 It usually arises in the head and neck region and most commonly affects older adults aged 50 to 70 years.3 The size of hidradenocarcinomas can vary; however, they typically are large, often growing to be greater than 5 cm in diameter.2 It tends to be an aggressive tumor that generally spreads to regional lymph nodes and distant viscera.4 Although it most commonly arises de novo, it may occasionally derive from a benign hidradenoma.1 The diagnosis of hidradenocarcinoma is made based on the tumor’s morphologic and pathologic characteristics. Histologically, it is characterized by an infiltrative and invasive proliferation of lobules made of large clear cells with atypical mitotic figures and nuclear pleomorphism as well as immunohistochemical features displaying various positive markers, such as carcinoembryonic antigen, epithelial membrane antigen, S-100 protein, and CKs AE1/AE3 and 5/6.2 Invasion of the adjacent soft tissue can be present and helps to confirm the diagnosis.

The differential diagnosis for hidradenocarcinoma primarily is the benign hidradenoma, which is similar both clinically and histologically with a few important differences. Hidradenocarcinomas often are larger and ulcerated. Histologically, they usually are more pleomorphic with the presence of mitotic figures in clear cells and tend to invade locally into the surrounding soft tissue. Other similar lesions such as spiradenoma, Merkel cell carcinoma, lymphangioma, cutaneous Crohn disease, tumors metastatic to the skin, and metastatic clear cell carcinomas originating from other organs also are included in the differential diagnosis.2

Spiradenomas are dermal tumors originating from the sweat glands. They typically present as bluish, painful, solitary nodules on the ventral surfaces of the upper body, though multiple nodules also are reported.5 Spiradenomas manifest as a central constellation of pale large cells surrounded by small, dark, basaloid cells containing hyperchromatic nuclei. The microscopic appearance of the blue basaloid cells contrasts with the clear cells seen in hidradenoma.5

Merkel cell carcinoma is a cutaneous neuroendocrine tumor affecting elderly or immunosuppressed individuals. It arises in sun-exposed areas and often is associated with Merkel cell polyomavirus infection. The histologic features display small and round cells that stain positive for CK8, CK18, CK19, and CK20 but stain negative for CK7, a marker that often is positive in hidradenocarcinoma.6

Lymphangioma, particularly cavernous lymphangioma, may resemble the gross appearance of hidradenoma/ hidradenocarcinoma. It usually presents as irregular clear blue papules and nodules in the skin and subcutaneous tissue.7 The key histopathologic finding in this tumor is the endothelium-lined channels that stain positive for D2-40, a lymphatic endothelium marker.7,8

Cutaneous Crohn disease is classified as noncaseating granulomatous skin lesions that are noncontinuous with the gastrointestinal tract.9 Clinical presentations in addition to skin edema include erythematous plaques, ulcerations, and erosions. Histopathology reveals sterile noncaseating granulomas made of Langerhans giant cells, epithelioid histocytes, and plasma cells.9

Metastatic clear cell carcinomas, such as renal cell carcinoma, can be differentiated by a history of primary carcinoma, demonstration of histologic vascular stroma, and other features related to metastatic clear cell carcinoma.2

There are no well-established therapeutic guidelines for hidradenocarcinoma. Wide local excision with margins greater than 2 cm is the preferred initial treatment and often is performed in conjunction with sentinel lymph node biopsy. External beam radiotherapy and adjunctive chemotherapy have been used for tumors that could not be surgically cleared. However, the efficacy of these treatments has not been well established.2 Targeted therapies recently have emerged as an alternative treatment choice for hidradenocarcinoma due to the utilization of immunohistochemical and genomic testing. The discovery of specific gene mutations or the expression of hormonal receptors in this tumor have paved the way for targeting HER2-expressing hidradenocarcinomas with trastuzumab and those expressing estrogen receptor with the estrogen receptor inhibitor tamoxifen.1 Epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors and PI3K/Akt/mTOR (phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase/AKT/mammalian target of rapamycin) pathway inhibitors also have been used to target various signal transduction pathways.2

Wide excision with 2.5-cm margins was performed on our patient, and a positron emission tomography– computed tomography scan revealed no metastatic disease. She declined sentinel lymph node biopsy and additional treatment. Due to the risk for recurrence, she was monitored closely with skin examinations and positron emission tomography–computed tomography every 3 months for the first year and every 6 months thereafter. Thus far, she has had no evidence of local or regional recurrence.

- Miller DH, Peterson JL, Buskirk SJ, et al. Management of metastatic apocrine hidradenocarcinoma with chemotherapy and radiation. Rare Tumors. 2015;7:6082.

- Soni A, Bansal N, Kaushal V, et al. Current management approach to hidradenocarcinoma: a comprehensive review of the literature. Ecancermedicalscience. 2015;9:517.

- Jinnah AH, Emory CL, Mai NH, et al. Hidradenocarcinoma presenting as soft tissue mass: case report with cytomorphologic description, histologic correlation, and differential diagnosis. Diagn Cytopathol. 2016;44:438-441.

- Khan BM, Mansha MA, Ali N, et al. Hidradenocarcinoma: five years of local and systemic control of a rare sweat gland neoplasm with nodal metastasis. Cureus. 2018;10:E2884.

- Miceli A, Ferrer-Bruker SJ. Spiradenoma. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2019.

- Banks PD, Sandhu S, Gyorki DE, et al. Recent insights and advances in the management of Merkel cell carcinoma. J Oncol Pract. 2016; 12:637-646.

- Flanagan BP, Helwig EB. Cutaneous lymphangioma. Arch Dermatol. 1977;113:24-30.

- Kalof AN, Cooper K. D2-40 immunohistochemistry—so far! Adv Anat Pathol. 2009;16:62-64.

- Schneider SL, Foster K, Patel D, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of metastatic Crohn’s disease. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35:566-574.

The Diagnosis: Hidradenocarcinoma

An excisional biopsy revealed a neoplasm in the dermis with focal invasion into the adjacent soft tissue (Figure 1). The tumor consisted of sheets of cells with cytoplasmic vacuoles and ductal differentiation (Figure 2), as well as cells with mild atypia, mild pleomorphism, rare mitotic figures, and abundant pale cytoplasm. Immunohistochemical staining was positive for cytokeratin (CK) 5, CK7, CK20, CK AE1/AE3, and p63 (Figure 3). The culmination of features including the large tumor size, immunohistochemical staining pattern, and mild pleomorphism with focal invasion into the soft tissue supported the diagnosis of hidradenocarcinoma.

Hidradenocarcinoma is an exceedingly rare malignant tumor of eccrine and/or apocrine origin.1 It accounts for less than 0.001% of all tumors and 1 of 13,000 skin biopsies.2 It usually arises in the head and neck region and most commonly affects older adults aged 50 to 70 years.3 The size of hidradenocarcinomas can vary; however, they typically are large, often growing to be greater than 5 cm in diameter.2 It tends to be an aggressive tumor that generally spreads to regional lymph nodes and distant viscera.4 Although it most commonly arises de novo, it may occasionally derive from a benign hidradenoma.1 The diagnosis of hidradenocarcinoma is made based on the tumor’s morphologic and pathologic characteristics. Histologically, it is characterized by an infiltrative and invasive proliferation of lobules made of large clear cells with atypical mitotic figures and nuclear pleomorphism as well as immunohistochemical features displaying various positive markers, such as carcinoembryonic antigen, epithelial membrane antigen, S-100 protein, and CKs AE1/AE3 and 5/6.2 Invasion of the adjacent soft tissue can be present and helps to confirm the diagnosis.

The differential diagnosis for hidradenocarcinoma primarily is the benign hidradenoma, which is similar both clinically and histologically with a few important differences. Hidradenocarcinomas often are larger and ulcerated. Histologically, they usually are more pleomorphic with the presence of mitotic figures in clear cells and tend to invade locally into the surrounding soft tissue. Other similar lesions such as spiradenoma, Merkel cell carcinoma, lymphangioma, cutaneous Crohn disease, tumors metastatic to the skin, and metastatic clear cell carcinomas originating from other organs also are included in the differential diagnosis.2

Spiradenomas are dermal tumors originating from the sweat glands. They typically present as bluish, painful, solitary nodules on the ventral surfaces of the upper body, though multiple nodules also are reported.5 Spiradenomas manifest as a central constellation of pale large cells surrounded by small, dark, basaloid cells containing hyperchromatic nuclei. The microscopic appearance of the blue basaloid cells contrasts with the clear cells seen in hidradenoma.5

Merkel cell carcinoma is a cutaneous neuroendocrine tumor affecting elderly or immunosuppressed individuals. It arises in sun-exposed areas and often is associated with Merkel cell polyomavirus infection. The histologic features display small and round cells that stain positive for CK8, CK18, CK19, and CK20 but stain negative for CK7, a marker that often is positive in hidradenocarcinoma.6

Lymphangioma, particularly cavernous lymphangioma, may resemble the gross appearance of hidradenoma/ hidradenocarcinoma. It usually presents as irregular clear blue papules and nodules in the skin and subcutaneous tissue.7 The key histopathologic finding in this tumor is the endothelium-lined channels that stain positive for D2-40, a lymphatic endothelium marker.7,8

Cutaneous Crohn disease is classified as noncaseating granulomatous skin lesions that are noncontinuous with the gastrointestinal tract.9 Clinical presentations in addition to skin edema include erythematous plaques, ulcerations, and erosions. Histopathology reveals sterile noncaseating granulomas made of Langerhans giant cells, epithelioid histocytes, and plasma cells.9

Metastatic clear cell carcinomas, such as renal cell carcinoma, can be differentiated by a history of primary carcinoma, demonstration of histologic vascular stroma, and other features related to metastatic clear cell carcinoma.2

There are no well-established therapeutic guidelines for hidradenocarcinoma. Wide local excision with margins greater than 2 cm is the preferred initial treatment and often is performed in conjunction with sentinel lymph node biopsy. External beam radiotherapy and adjunctive chemotherapy have been used for tumors that could not be surgically cleared. However, the efficacy of these treatments has not been well established.2 Targeted therapies recently have emerged as an alternative treatment choice for hidradenocarcinoma due to the utilization of immunohistochemical and genomic testing. The discovery of specific gene mutations or the expression of hormonal receptors in this tumor have paved the way for targeting HER2-expressing hidradenocarcinomas with trastuzumab and those expressing estrogen receptor with the estrogen receptor inhibitor tamoxifen.1 Epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors and PI3K/Akt/mTOR (phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase/AKT/mammalian target of rapamycin) pathway inhibitors also have been used to target various signal transduction pathways.2

Wide excision with 2.5-cm margins was performed on our patient, and a positron emission tomography– computed tomography scan revealed no metastatic disease. She declined sentinel lymph node biopsy and additional treatment. Due to the risk for recurrence, she was monitored closely with skin examinations and positron emission tomography–computed tomography every 3 months for the first year and every 6 months thereafter. Thus far, she has had no evidence of local or regional recurrence.

The Diagnosis: Hidradenocarcinoma

An excisional biopsy revealed a neoplasm in the dermis with focal invasion into the adjacent soft tissue (Figure 1). The tumor consisted of sheets of cells with cytoplasmic vacuoles and ductal differentiation (Figure 2), as well as cells with mild atypia, mild pleomorphism, rare mitotic figures, and abundant pale cytoplasm. Immunohistochemical staining was positive for cytokeratin (CK) 5, CK7, CK20, CK AE1/AE3, and p63 (Figure 3). The culmination of features including the large tumor size, immunohistochemical staining pattern, and mild pleomorphism with focal invasion into the soft tissue supported the diagnosis of hidradenocarcinoma.

Hidradenocarcinoma is an exceedingly rare malignant tumor of eccrine and/or apocrine origin.1 It accounts for less than 0.001% of all tumors and 1 of 13,000 skin biopsies.2 It usually arises in the head and neck region and most commonly affects older adults aged 50 to 70 years.3 The size of hidradenocarcinomas can vary; however, they typically are large, often growing to be greater than 5 cm in diameter.2 It tends to be an aggressive tumor that generally spreads to regional lymph nodes and distant viscera.4 Although it most commonly arises de novo, it may occasionally derive from a benign hidradenoma.1 The diagnosis of hidradenocarcinoma is made based on the tumor’s morphologic and pathologic characteristics. Histologically, it is characterized by an infiltrative and invasive proliferation of lobules made of large clear cells with atypical mitotic figures and nuclear pleomorphism as well as immunohistochemical features displaying various positive markers, such as carcinoembryonic antigen, epithelial membrane antigen, S-100 protein, and CKs AE1/AE3 and 5/6.2 Invasion of the adjacent soft tissue can be present and helps to confirm the diagnosis.

The differential diagnosis for hidradenocarcinoma primarily is the benign hidradenoma, which is similar both clinically and histologically with a few important differences. Hidradenocarcinomas often are larger and ulcerated. Histologically, they usually are more pleomorphic with the presence of mitotic figures in clear cells and tend to invade locally into the surrounding soft tissue. Other similar lesions such as spiradenoma, Merkel cell carcinoma, lymphangioma, cutaneous Crohn disease, tumors metastatic to the skin, and metastatic clear cell carcinomas originating from other organs also are included in the differential diagnosis.2

Spiradenomas are dermal tumors originating from the sweat glands. They typically present as bluish, painful, solitary nodules on the ventral surfaces of the upper body, though multiple nodules also are reported.5 Spiradenomas manifest as a central constellation of pale large cells surrounded by small, dark, basaloid cells containing hyperchromatic nuclei. The microscopic appearance of the blue basaloid cells contrasts with the clear cells seen in hidradenoma.5

Merkel cell carcinoma is a cutaneous neuroendocrine tumor affecting elderly or immunosuppressed individuals. It arises in sun-exposed areas and often is associated with Merkel cell polyomavirus infection. The histologic features display small and round cells that stain positive for CK8, CK18, CK19, and CK20 but stain negative for CK7, a marker that often is positive in hidradenocarcinoma.6

Lymphangioma, particularly cavernous lymphangioma, may resemble the gross appearance of hidradenoma/ hidradenocarcinoma. It usually presents as irregular clear blue papules and nodules in the skin and subcutaneous tissue.7 The key histopathologic finding in this tumor is the endothelium-lined channels that stain positive for D2-40, a lymphatic endothelium marker.7,8

Cutaneous Crohn disease is classified as noncaseating granulomatous skin lesions that are noncontinuous with the gastrointestinal tract.9 Clinical presentations in addition to skin edema include erythematous plaques, ulcerations, and erosions. Histopathology reveals sterile noncaseating granulomas made of Langerhans giant cells, epithelioid histocytes, and plasma cells.9

Metastatic clear cell carcinomas, such as renal cell carcinoma, can be differentiated by a history of primary carcinoma, demonstration of histologic vascular stroma, and other features related to metastatic clear cell carcinoma.2

There are no well-established therapeutic guidelines for hidradenocarcinoma. Wide local excision with margins greater than 2 cm is the preferred initial treatment and often is performed in conjunction with sentinel lymph node biopsy. External beam radiotherapy and adjunctive chemotherapy have been used for tumors that could not be surgically cleared. However, the efficacy of these treatments has not been well established.2 Targeted therapies recently have emerged as an alternative treatment choice for hidradenocarcinoma due to the utilization of immunohistochemical and genomic testing. The discovery of specific gene mutations or the expression of hormonal receptors in this tumor have paved the way for targeting HER2-expressing hidradenocarcinomas with trastuzumab and those expressing estrogen receptor with the estrogen receptor inhibitor tamoxifen.1 Epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors and PI3K/Akt/mTOR (phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase/AKT/mammalian target of rapamycin) pathway inhibitors also have been used to target various signal transduction pathways.2

Wide excision with 2.5-cm margins was performed on our patient, and a positron emission tomography– computed tomography scan revealed no metastatic disease. She declined sentinel lymph node biopsy and additional treatment. Due to the risk for recurrence, she was monitored closely with skin examinations and positron emission tomography–computed tomography every 3 months for the first year and every 6 months thereafter. Thus far, she has had no evidence of local or regional recurrence.

- Miller DH, Peterson JL, Buskirk SJ, et al. Management of metastatic apocrine hidradenocarcinoma with chemotherapy and radiation. Rare Tumors. 2015;7:6082.

- Soni A, Bansal N, Kaushal V, et al. Current management approach to hidradenocarcinoma: a comprehensive review of the literature. Ecancermedicalscience. 2015;9:517.

- Jinnah AH, Emory CL, Mai NH, et al. Hidradenocarcinoma presenting as soft tissue mass: case report with cytomorphologic description, histologic correlation, and differential diagnosis. Diagn Cytopathol. 2016;44:438-441.

- Khan BM, Mansha MA, Ali N, et al. Hidradenocarcinoma: five years of local and systemic control of a rare sweat gland neoplasm with nodal metastasis. Cureus. 2018;10:E2884.

- Miceli A, Ferrer-Bruker SJ. Spiradenoma. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2019.

- Banks PD, Sandhu S, Gyorki DE, et al. Recent insights and advances in the management of Merkel cell carcinoma. J Oncol Pract. 2016; 12:637-646.

- Flanagan BP, Helwig EB. Cutaneous lymphangioma. Arch Dermatol. 1977;113:24-30.

- Kalof AN, Cooper K. D2-40 immunohistochemistry—so far! Adv Anat Pathol. 2009;16:62-64.

- Schneider SL, Foster K, Patel D, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of metastatic Crohn’s disease. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35:566-574.

- Miller DH, Peterson JL, Buskirk SJ, et al. Management of metastatic apocrine hidradenocarcinoma with chemotherapy and radiation. Rare Tumors. 2015;7:6082.

- Soni A, Bansal N, Kaushal V, et al. Current management approach to hidradenocarcinoma: a comprehensive review of the literature. Ecancermedicalscience. 2015;9:517.

- Jinnah AH, Emory CL, Mai NH, et al. Hidradenocarcinoma presenting as soft tissue mass: case report with cytomorphologic description, histologic correlation, and differential diagnosis. Diagn Cytopathol. 2016;44:438-441.

- Khan BM, Mansha MA, Ali N, et al. Hidradenocarcinoma: five years of local and systemic control of a rare sweat gland neoplasm with nodal metastasis. Cureus. 2018;10:E2884.

- Miceli A, Ferrer-Bruker SJ. Spiradenoma. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2019.

- Banks PD, Sandhu S, Gyorki DE, et al. Recent insights and advances in the management of Merkel cell carcinoma. J Oncol Pract. 2016; 12:637-646.

- Flanagan BP, Helwig EB. Cutaneous lymphangioma. Arch Dermatol. 1977;113:24-30.

- Kalof AN, Cooper K. D2-40 immunohistochemistry—so far! Adv Anat Pathol. 2009;16:62-64.

- Schneider SL, Foster K, Patel D, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of metastatic Crohn’s disease. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35:566-574.

A 20-year-old woman with no notable medical history presented to the dermatology clinic with an enlarging mass on the right buttock that had been growing over the course of several years. The mass progressed from a small, mildly tender nodule to a 10×10-cm, hyperpigmented, exophytic tumor. There were no other abnormal findings on physical examination, and the patient denied any systemic symptoms.

Erythematous Edematous Plaques on the Dorsal Aspects of the Hands

The Diagnosis: Phytophotodermatitis

Initially, there was concern for autoimmune or connective tissue disease because of the edematous plaques localized over sun-exposed regions of the hands with marked sparing of the knuckles. Lupus erythematosus (LE), mixed connective tissue disease, CREST (calcinosis, Raynaud phenomenon, esophageal motility disorders, sclerodactyly, telangiectasia) syndrome, dermatomyositis (DM), and erythromelalgia all were considered. Common disorders such as contact dermatitis and phytophotodermatitis remained in the differential diagnosis, though the patient adamantly denied any recent exposures. As part of the initial workup, laboratory studies including a complete blood cell count, comprehensive metabolic panel, serum lactate dehydrogenase, serum creatinine kinase, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and an antinuclear antibody panel were performed. Additionally, a punch biopsy at the border of the lesion was performed.

Lupus erythematosus was considered given the patient’s age and sex and the photoexposed location of the plaques. The photosensitive rash of LE classically affects the dorsal aspects of the hands while sparing the interphalangeal joints.1,2 However, the patient had no nail fold findings consistent with systemic LE with no evidence of erythema or dilated tortuous vessels.3 Furthermore, there were no other cutaneous symptoms, and there was a negative review of systems, including malar/discoid rash, oral ulcers, photosensitivity, history of hematologic abnormalities, and end organ damage.4,5 A negative antinuclear antibody serologic panel combined with a negative review of systems made the diagnosis of LE less likely.

Given the presenting clinical appearance, DM also was considered. Dermatomyositis traditionally displays ragged cuticular dystrophy with nail fold telangiectasia, mechanic hands, and involvement of the dorsal aspects of the hands with violaceous accentuation of the knuckles.6 The patient reported pruritus, which is common among DM patients; however, the nail folds were unaffected.7 Finally, she demonstrated sparing rather than involvement of the knuckles, which would be an unlikely presentation for DM.6

CREST syndrome, systemic sclerosis, and syndromes with overlapping features such as mixed connective tissue disease also were considered. The cutaneous features of CREST syndrome are characterized by initial edema of the digits with a subsequent taut and shiny indurated phase. Flexion contractures, ulceration, tapering of the digits, and loss of cutaneous fat pads can progressively occur.8,9 Raynaud phenomenon is a common early finding in CREST syndrome or systemic sclerosis, and patients may develop ice pick digital infarcts and calcinosis in progressed disease.8 Common nail fold findings include periungual telangiectasia with dropout areas.10,11 The marked edema and white discoloration of the knuckles in this patient could be mistaken for Raynaud phenomenon; however, she lacked pain or cold sensitivity and her discoloration was static.12 Without sclerodermoid changes, nail fold findings, matted telangiectasia, taut skin, or systemic findings, a diagnosis of CREST syndrome, scleroderma, or other mixed connective tissue disease would be unlikely.8

Erythromelalgia is a clinical syndrome characterized by burning pain, erythema, and increased skin temperature that intermittently affects both the arms and legs. This rare disorder can be further classified into type 1 (associated with thrombocytopenia), type 2 (primary or idiopathic), and type 3 (associated with other medical cause excluding thrombocytopenia).1,13 The patient endorsed some discomfort from the lesions but denied any subjective feeling of burning pain or increased skin temperature. Additionally, she had no family history of inheritable skin disorders and no personal history of polycythemia. Consequently, erythromelalgia remained less likely on the differential diagnosis.

The histology of the acral skin revealed mild focal spongiosis with no increase in dermal mucin on colloidal iron or mucopolysaccharide stains (Figure). After receiving the biopsy results and additional questioning of the patient, it was discovered that 2 days prior to her initial presentation she had juiced numerous limes by hand and subsequently spent a long period of time outside with sunlight exposure. Upon discovery of this additional historical information, the diagnosis of phytophotodermatitis was made.

Phytophotodermatitis is an erythematous inflammatory reaction that occurs on the skin after exposure to a plant-derived photosensitizer followed by UVA light radiation.14 This phenomenon was first described by the ancient Egyptians as a treatment for vitiligo.1 The most common plant families that can cause this nonimmune cutaneous reaction include Apiaceae eg, hogweed, celery, dill, fennel) and Rutaceae (eg, citrus plants, rue).14 The psoralens or furocoumarins found in these plants bind loosely to DNA at their ground state but covalently bond to pyrimidine bases during photoexcitation with UVA, resulting in DNA damage and subsequent local inflammation.14 Given the patient’s clinical examination, pathology findings, and history, phytophotodermatitis secondary to lime juice exposure was confirmed. Two weeks after applying clobetasol ointment twice daily, the patient’s hands had returned to baseline with complete resolution of the erythematous lesions.

Although lime phytophotodermatitis is a routine diagnosis, this clinical case stands as an important reminder to demonstrate how common diseases can masquerade as more exotic cutaneous disorders. There often is a clinical desire to seek out more complicated diagnoses, particularly during residency training; however, this case reinforces the invaluable importance of collecting a thorough patient history, as it can ultimately minimize excessive testing and in some cases prevent unnecessary therapy.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. China:Elsevier Saunders; 2012.

- Uva L, Miguel D, Pinheiro C, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of systemiclupus erythematosus. Autoimmune Dis. 2012;2012:834291.

- Furtado R, Pucinelli M, Cristo V, et al. Scleroderma-like nailfold capillaroscopicabnormalities are associated with anti-U1-RNP antibodies and Raynaud’s phenomenon in SLE patients. Lupus. 2002;11:35-41.

- Wenzel J, Zahn S, Tuting T. Pathogenesis of cutaneous lupus erythematosus:common and different features in distinct subsets. Lupus. 2010;19:1020-1028.

- Avilés Izquierdo JA, Cano Martínez N, Lázaro Ochaita P. Epidemiologicalcharacteristics of patients with cutaneous lupus erythematosus.Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2014;105:69-73.

- Marvi U, Chung L, Fiorentino DF. Clinical presentation and evaluation of dermatomyositis. Indian J Dermatol. 2012;57:375-381.

- Shirani Z, Kucenic MJ, Carroll CL, et al. Pruritus in adult dermatomyositis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2004;29:273-276.

- Krieg T, Takehara K. Skin disease: a cardinal feature of systemic sclerosis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2009;48(suppl 3):14-18.

- Mizutani H, Mizutani T, Okada H, et al. Round fingerpad sign: an early sign of scleroderma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;24:67-69.

- Baran R, Dawber RP, Haneke E, et al, eds. A Text Atlas of Nail Disorders Techniques in Investigation and Diagnosis. 3rd ed. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2005.

- Ghali FE, Stein LD, Fine J, et al. Gingival telangiectases: an underappreciated physical sign of juvenile dermatomyositis. Arch Dermatol. 1999;135:1370-1374.

- Grader-Beck T, Wigley FM. Raynaud’s phenomenon in mixed connective tissue disease. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2005;31:465-481.

- Davis MD, Weenig RH, Genebriera J, et al. Histopathologic findings in primary erythromelalgia are nonspecific: special studies show a decrease in small nerve fiber density. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:519-522.

- Sasseville D. Clinical patterns of phytophotodermatitis. Dermatol Clin. 2009;27:299-308.

The Diagnosis: Phytophotodermatitis

Initially, there was concern for autoimmune or connective tissue disease because of the edematous plaques localized over sun-exposed regions of the hands with marked sparing of the knuckles. Lupus erythematosus (LE), mixed connective tissue disease, CREST (calcinosis, Raynaud phenomenon, esophageal motility disorders, sclerodactyly, telangiectasia) syndrome, dermatomyositis (DM), and erythromelalgia all were considered. Common disorders such as contact dermatitis and phytophotodermatitis remained in the differential diagnosis, though the patient adamantly denied any recent exposures. As part of the initial workup, laboratory studies including a complete blood cell count, comprehensive metabolic panel, serum lactate dehydrogenase, serum creatinine kinase, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and an antinuclear antibody panel were performed. Additionally, a punch biopsy at the border of the lesion was performed.

Lupus erythematosus was considered given the patient’s age and sex and the photoexposed location of the plaques. The photosensitive rash of LE classically affects the dorsal aspects of the hands while sparing the interphalangeal joints.1,2 However, the patient had no nail fold findings consistent with systemic LE with no evidence of erythema or dilated tortuous vessels.3 Furthermore, there were no other cutaneous symptoms, and there was a negative review of systems, including malar/discoid rash, oral ulcers, photosensitivity, history of hematologic abnormalities, and end organ damage.4,5 A negative antinuclear antibody serologic panel combined with a negative review of systems made the diagnosis of LE less likely.

Given the presenting clinical appearance, DM also was considered. Dermatomyositis traditionally displays ragged cuticular dystrophy with nail fold telangiectasia, mechanic hands, and involvement of the dorsal aspects of the hands with violaceous accentuation of the knuckles.6 The patient reported pruritus, which is common among DM patients; however, the nail folds were unaffected.7 Finally, she demonstrated sparing rather than involvement of the knuckles, which would be an unlikely presentation for DM.6

CREST syndrome, systemic sclerosis, and syndromes with overlapping features such as mixed connective tissue disease also were considered. The cutaneous features of CREST syndrome are characterized by initial edema of the digits with a subsequent taut and shiny indurated phase. Flexion contractures, ulceration, tapering of the digits, and loss of cutaneous fat pads can progressively occur.8,9 Raynaud phenomenon is a common early finding in CREST syndrome or systemic sclerosis, and patients may develop ice pick digital infarcts and calcinosis in progressed disease.8 Common nail fold findings include periungual telangiectasia with dropout areas.10,11 The marked edema and white discoloration of the knuckles in this patient could be mistaken for Raynaud phenomenon; however, she lacked pain or cold sensitivity and her discoloration was static.12 Without sclerodermoid changes, nail fold findings, matted telangiectasia, taut skin, or systemic findings, a diagnosis of CREST syndrome, scleroderma, or other mixed connective tissue disease would be unlikely.8

Erythromelalgia is a clinical syndrome characterized by burning pain, erythema, and increased skin temperature that intermittently affects both the arms and legs. This rare disorder can be further classified into type 1 (associated with thrombocytopenia), type 2 (primary or idiopathic), and type 3 (associated with other medical cause excluding thrombocytopenia).1,13 The patient endorsed some discomfort from the lesions but denied any subjective feeling of burning pain or increased skin temperature. Additionally, she had no family history of inheritable skin disorders and no personal history of polycythemia. Consequently, erythromelalgia remained less likely on the differential diagnosis.

The histology of the acral skin revealed mild focal spongiosis with no increase in dermal mucin on colloidal iron or mucopolysaccharide stains (Figure). After receiving the biopsy results and additional questioning of the patient, it was discovered that 2 days prior to her initial presentation she had juiced numerous limes by hand and subsequently spent a long period of time outside with sunlight exposure. Upon discovery of this additional historical information, the diagnosis of phytophotodermatitis was made.

Phytophotodermatitis is an erythematous inflammatory reaction that occurs on the skin after exposure to a plant-derived photosensitizer followed by UVA light radiation.14 This phenomenon was first described by the ancient Egyptians as a treatment for vitiligo.1 The most common plant families that can cause this nonimmune cutaneous reaction include Apiaceae eg, hogweed, celery, dill, fennel) and Rutaceae (eg, citrus plants, rue).14 The psoralens or furocoumarins found in these plants bind loosely to DNA at their ground state but covalently bond to pyrimidine bases during photoexcitation with UVA, resulting in DNA damage and subsequent local inflammation.14 Given the patient’s clinical examination, pathology findings, and history, phytophotodermatitis secondary to lime juice exposure was confirmed. Two weeks after applying clobetasol ointment twice daily, the patient’s hands had returned to baseline with complete resolution of the erythematous lesions.

Although lime phytophotodermatitis is a routine diagnosis, this clinical case stands as an important reminder to demonstrate how common diseases can masquerade as more exotic cutaneous disorders. There often is a clinical desire to seek out more complicated diagnoses, particularly during residency training; however, this case reinforces the invaluable importance of collecting a thorough patient history, as it can ultimately minimize excessive testing and in some cases prevent unnecessary therapy.

The Diagnosis: Phytophotodermatitis

Initially, there was concern for autoimmune or connective tissue disease because of the edematous plaques localized over sun-exposed regions of the hands with marked sparing of the knuckles. Lupus erythematosus (LE), mixed connective tissue disease, CREST (calcinosis, Raynaud phenomenon, esophageal motility disorders, sclerodactyly, telangiectasia) syndrome, dermatomyositis (DM), and erythromelalgia all were considered. Common disorders such as contact dermatitis and phytophotodermatitis remained in the differential diagnosis, though the patient adamantly denied any recent exposures. As part of the initial workup, laboratory studies including a complete blood cell count, comprehensive metabolic panel, serum lactate dehydrogenase, serum creatinine kinase, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and an antinuclear antibody panel were performed. Additionally, a punch biopsy at the border of the lesion was performed.

Lupus erythematosus was considered given the patient’s age and sex and the photoexposed location of the plaques. The photosensitive rash of LE classically affects the dorsal aspects of the hands while sparing the interphalangeal joints.1,2 However, the patient had no nail fold findings consistent with systemic LE with no evidence of erythema or dilated tortuous vessels.3 Furthermore, there were no other cutaneous symptoms, and there was a negative review of systems, including malar/discoid rash, oral ulcers, photosensitivity, history of hematologic abnormalities, and end organ damage.4,5 A negative antinuclear antibody serologic panel combined with a negative review of systems made the diagnosis of LE less likely.

Given the presenting clinical appearance, DM also was considered. Dermatomyositis traditionally displays ragged cuticular dystrophy with nail fold telangiectasia, mechanic hands, and involvement of the dorsal aspects of the hands with violaceous accentuation of the knuckles.6 The patient reported pruritus, which is common among DM patients; however, the nail folds were unaffected.7 Finally, she demonstrated sparing rather than involvement of the knuckles, which would be an unlikely presentation for DM.6

CREST syndrome, systemic sclerosis, and syndromes with overlapping features such as mixed connective tissue disease also were considered. The cutaneous features of CREST syndrome are characterized by initial edema of the digits with a subsequent taut and shiny indurated phase. Flexion contractures, ulceration, tapering of the digits, and loss of cutaneous fat pads can progressively occur.8,9 Raynaud phenomenon is a common early finding in CREST syndrome or systemic sclerosis, and patients may develop ice pick digital infarcts and calcinosis in progressed disease.8 Common nail fold findings include periungual telangiectasia with dropout areas.10,11 The marked edema and white discoloration of the knuckles in this patient could be mistaken for Raynaud phenomenon; however, she lacked pain or cold sensitivity and her discoloration was static.12 Without sclerodermoid changes, nail fold findings, matted telangiectasia, taut skin, or systemic findings, a diagnosis of CREST syndrome, scleroderma, or other mixed connective tissue disease would be unlikely.8

Erythromelalgia is a clinical syndrome characterized by burning pain, erythema, and increased skin temperature that intermittently affects both the arms and legs. This rare disorder can be further classified into type 1 (associated with thrombocytopenia), type 2 (primary or idiopathic), and type 3 (associated with other medical cause excluding thrombocytopenia).1,13 The patient endorsed some discomfort from the lesions but denied any subjective feeling of burning pain or increased skin temperature. Additionally, she had no family history of inheritable skin disorders and no personal history of polycythemia. Consequently, erythromelalgia remained less likely on the differential diagnosis.

The histology of the acral skin revealed mild focal spongiosis with no increase in dermal mucin on colloidal iron or mucopolysaccharide stains (Figure). After receiving the biopsy results and additional questioning of the patient, it was discovered that 2 days prior to her initial presentation she had juiced numerous limes by hand and subsequently spent a long period of time outside with sunlight exposure. Upon discovery of this additional historical information, the diagnosis of phytophotodermatitis was made.

Phytophotodermatitis is an erythematous inflammatory reaction that occurs on the skin after exposure to a plant-derived photosensitizer followed by UVA light radiation.14 This phenomenon was first described by the ancient Egyptians as a treatment for vitiligo.1 The most common plant families that can cause this nonimmune cutaneous reaction include Apiaceae eg, hogweed, celery, dill, fennel) and Rutaceae (eg, citrus plants, rue).14 The psoralens or furocoumarins found in these plants bind loosely to DNA at their ground state but covalently bond to pyrimidine bases during photoexcitation with UVA, resulting in DNA damage and subsequent local inflammation.14 Given the patient’s clinical examination, pathology findings, and history, phytophotodermatitis secondary to lime juice exposure was confirmed. Two weeks after applying clobetasol ointment twice daily, the patient’s hands had returned to baseline with complete resolution of the erythematous lesions.

Although lime phytophotodermatitis is a routine diagnosis, this clinical case stands as an important reminder to demonstrate how common diseases can masquerade as more exotic cutaneous disorders. There often is a clinical desire to seek out more complicated diagnoses, particularly during residency training; however, this case reinforces the invaluable importance of collecting a thorough patient history, as it can ultimately minimize excessive testing and in some cases prevent unnecessary therapy.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. China:Elsevier Saunders; 2012.

- Uva L, Miguel D, Pinheiro C, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of systemiclupus erythematosus. Autoimmune Dis. 2012;2012:834291.

- Furtado R, Pucinelli M, Cristo V, et al. Scleroderma-like nailfold capillaroscopicabnormalities are associated with anti-U1-RNP antibodies and Raynaud’s phenomenon in SLE patients. Lupus. 2002;11:35-41.

- Wenzel J, Zahn S, Tuting T. Pathogenesis of cutaneous lupus erythematosus:common and different features in distinct subsets. Lupus. 2010;19:1020-1028.

- Avilés Izquierdo JA, Cano Martínez N, Lázaro Ochaita P. Epidemiologicalcharacteristics of patients with cutaneous lupus erythematosus.Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2014;105:69-73.

- Marvi U, Chung L, Fiorentino DF. Clinical presentation and evaluation of dermatomyositis. Indian J Dermatol. 2012;57:375-381.

- Shirani Z, Kucenic MJ, Carroll CL, et al. Pruritus in adult dermatomyositis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2004;29:273-276.

- Krieg T, Takehara K. Skin disease: a cardinal feature of systemic sclerosis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2009;48(suppl 3):14-18.

- Mizutani H, Mizutani T, Okada H, et al. Round fingerpad sign: an early sign of scleroderma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;24:67-69.

- Baran R, Dawber RP, Haneke E, et al, eds. A Text Atlas of Nail Disorders Techniques in Investigation and Diagnosis. 3rd ed. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2005.

- Ghali FE, Stein LD, Fine J, et al. Gingival telangiectases: an underappreciated physical sign of juvenile dermatomyositis. Arch Dermatol. 1999;135:1370-1374.

- Grader-Beck T, Wigley FM. Raynaud’s phenomenon in mixed connective tissue disease. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2005;31:465-481.

- Davis MD, Weenig RH, Genebriera J, et al. Histopathologic findings in primary erythromelalgia are nonspecific: special studies show a decrease in small nerve fiber density. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:519-522.

- Sasseville D. Clinical patterns of phytophotodermatitis. Dermatol Clin. 2009;27:299-308.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. China:Elsevier Saunders; 2012.

- Uva L, Miguel D, Pinheiro C, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of systemiclupus erythematosus. Autoimmune Dis. 2012;2012:834291.

- Furtado R, Pucinelli M, Cristo V, et al. Scleroderma-like nailfold capillaroscopicabnormalities are associated with anti-U1-RNP antibodies and Raynaud’s phenomenon in SLE patients. Lupus. 2002;11:35-41.

- Wenzel J, Zahn S, Tuting T. Pathogenesis of cutaneous lupus erythematosus:common and different features in distinct subsets. Lupus. 2010;19:1020-1028.

- Avilés Izquierdo JA, Cano Martínez N, Lázaro Ochaita P. Epidemiologicalcharacteristics of patients with cutaneous lupus erythematosus.Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2014;105:69-73.

- Marvi U, Chung L, Fiorentino DF. Clinical presentation and evaluation of dermatomyositis. Indian J Dermatol. 2012;57:375-381.

- Shirani Z, Kucenic MJ, Carroll CL, et al. Pruritus in adult dermatomyositis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2004;29:273-276.

- Krieg T, Takehara K. Skin disease: a cardinal feature of systemic sclerosis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2009;48(suppl 3):14-18.

- Mizutani H, Mizutani T, Okada H, et al. Round fingerpad sign: an early sign of scleroderma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;24:67-69.

- Baran R, Dawber RP, Haneke E, et al, eds. A Text Atlas of Nail Disorders Techniques in Investigation and Diagnosis. 3rd ed. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2005.

- Ghali FE, Stein LD, Fine J, et al. Gingival telangiectases: an underappreciated physical sign of juvenile dermatomyositis. Arch Dermatol. 1999;135:1370-1374.

- Grader-Beck T, Wigley FM. Raynaud’s phenomenon in mixed connective tissue disease. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2005;31:465-481.

- Davis MD, Weenig RH, Genebriera J, et al. Histopathologic findings in primary erythromelalgia are nonspecific: special studies show a decrease in small nerve fiber density. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:519-522.

- Sasseville D. Clinical patterns of phytophotodermatitis. Dermatol Clin. 2009;27:299-308.

A 48-year-old woman presented with erythematous swelling of the dorsal aspects of the bilateral hands followed by desquamation and pruritus of 2 weeks’ duration. She denied any recent contact with plants, chemicals, or topical products or use of over-the-counter medications. A 6-day course of prednisone provided by her primary care physician relieved the swelling and pruritus; however, the erythema persisted. Physical examination revealed clearly demarcated, erythematous to violaceous, edematous plaques with peripheral scaling that involved all digits. There was notable sparing of the proximal interphalangeal joints and volar aspects of the hands extending proximally to the metacarpophalangeal joints.