User login

Sorting through the recent controversies in breast cancer screening

Editor’s Note: This commentary, written by members of the Cleveland Clinic Breast Cancer Screening Task Force, was not independently peer-reviewed.

In November 2009, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) announced its new guidelines for breast cancer screening—and created an instant controversy by suggesting that fewer screening tests be done.1

The November 2009 update recommended that most women wait until age 50 to get their first screening mammogram instead of getting it at age 40, that they get a mammogram every other year instead of every year, and that physicians not teach their patients breast self-examination anymore. However, on December 4, 2009, the USPSTF members voted to modify the recommendation for women under age 50, stating that the decision to start screening mammography every 2 years should be individualized, taking into account the patient’s preferences after being apprised of the possible benefits and harms.2

Various professional and advocacy groups have reacted differently to the new guidelines, and as a result, women are unsure about the optimal screening for breast cancer.

NEW GUIDELINES ARE BASED ON TWO STUDIES

The USPSTF commissioned two studies, which it used to formulate the new recommendations.3,4 Its goal was to evaluate the current evidence for the efficacy of several screening tests and schedules in reducing breast cancer mortality rates.

An updated systematic review

Nelson et al3 performed a systematic review of studies of the benefit and harm of screening with mammography, clinical breast examination, and breast self-examination.

Screening mammography continued to demonstrate a reduction in deaths due to breast cancer. The risk reduction ranged from 14% to 32% in women age 50 to 69. Similarly, it was calculated to reduce the incidence of deaths due to breast cancer by 15% in women age 39 to 49. However, this younger age group has a relatively low incidence of breast cancer, and therefore, according to this analysis, 556 women need to undergo one round of screening to detect one case of invasive breast cancer, and 1,904 women need to be offered screening (over several rounds, which varied by trial) to prevent one breast cancer death.3

Most of the harm of screening in the 39-to-49-year age category was due to false-positive results, which were more common in this group than in older women. The authors calculated that after every round of screening mammography, about 84 of every 1,000 women in the younger age category need additional imaging and about 9 need a biopsy. The issue of overdiagnosis (detection of cancers that would have never been a problem in one’s lifetime) was not specifically addressed for this age category, and in different studies, estimates of overdiagnosis rates for all age groups varied widely, from less than 1% to 30%.

Beyond age 70, the authors reported the data insufficient for evaluating the benefit and harm of screening mammography.

Breast self-examination was found to offer no benefit, based largely on two randomized studies, one in St. Petersburg, Russia,5 and the other in Shanghai, China,6 both places where screening mammography was not routinely offered. These studies and one observational study in the United States7 failed to show a reduction in breast cancer mortality rates with breast self-examination.

Clinical breast examination (ie, by a health care provider) lacked sufficient data to draw conclusions.

A study based on statistical models of mammography

Mandelblatt et al4 used statistical modeling to estimate the effect of mammographic screening at various ages and at different intervals.

The authors used six statistical models previously shown to give similar qualitative estimates of the contribution of screening in reducing breast cancer mortality rates. They estimated the number of mammograms required relative to the number of cancers detected, the number of breast cancer deaths prevented, and the harms (false-positive mammograms, unnecessary biopsies, and overdiagnosis) incurred with 20 different screening strategies, ie, screening with different starting and stopping ages and at intervals of either 1 or 2 years.

They estimated that screening every other year would achieve most of the benefit of screening every year, with less harm. Looking at the different strategies and models, on average, biennial screening would, by their calculations, achieve about 81% of the mortality reduction achieved with annual screening. Compared with screening women ages 50 to 69 only, extending screening to women age 40 to 49 would reduce the cancer mortality rate by 3% more, while extending it up to age 79 would reduce it by another 7% to 8%.

In terms of harm, the models predicted more false-positive studies if screening were started before age 50 and if it were done annually rather than biennially. They also predicted that more unnecessary biopsies would be done with annual screening than with screening every 2 years. The models suggested that the risk for overdiagnosis was higher in older age groups because of higher rates of death from causes other than breast cancer, and that the overdiagnosis rate was also somewhat higher with annual than with 2-year screening.

WHAT WOULD LESS SCREENING MEAN?

Our practice has been to initiate annual screening with mammography at age 40 and to continue as long as the patient’s life expectancy is at least 10 years.

According to the models used by Mandelblatt et al,4 screening 1,000 women every year, starting at age 40 and continuing until age 84, would result in 177 to 227 life-years gained compared with no screening. In contrast, screening only women age 50 to 74 and only every other year (as advocated in the new guidelines) would entail about one-third the number of mammograms but would result in fewer life-years gained per 1,000 women screened: between 96 and 128. If we take the mean of the estimates from the six models, adherence to the new screening guidelines would be estimated to result in about 79 fewer life-years gained for every 1,000 women screened. On the other hand, each woman screened would need to undergo about 25 fewer screening mammograms in her lifetime.4

KEY POINTS ABOUT BREAST CANCER SCREENING

Together, these studies demonstrate several points about breast cancer screening.

Importantly, randomized controlled trials and model analyses continue to show that screening mammography reduces the breast cancer mortality rate.

The studies and models also reinforce the concept that those at greatest risk get the most benefit from screening. Because the incidence of breast cancer rises with age, the probability of a true-positive result is higher in women over age 50 than it is in younger women, and, therefore, the screening test performs better.

On the other hand, women at high risk of dying of other causes, such as those over age 75, achieve less benefit from screening, as some of the cancers detected in this manner may not contribute to their death even if they are not detected early.

Screening is therefore best targeted at people who are healthy but who are at sufficient risk for the disease in question to justify the screening.

CLEVELAND CLINIC’S POSITION

In December 2009, the Cleveland Clinic Breast Cancer Screening Task Force, a multidisciplinary panel of breast cancer experts, breast radiologists, and primary care providers, convened to review the literature and set forth institutional recommendations for breast cancer screening for healthy women. The authors of this paper are members of this task force. Our consensus recommendations:

- We continue to recommend annual mammography for most healthy women over age 40.

- Screening every other year is an option for older postmenopausal women, as they are likely to achieve most of the benefit of annual screening with this schedule.

- We agree with the USPSTF finding that there are insufficient data to provide evidenced-based recommendations regarding the benefits and harms of clinical breast examination. However, breast examination was done as part of the screening in many of the randomized trials of mammography and cannot easily be separated from mammography. Therefore, we believe that careful examination of the breasts remains an important consideration in the general physical examination.

- The USPSTF recommendation not to teach breast self-examination was based on studies that probably do not apply to the US population. Therefore, we continue to recommend that women be familiar with their breasts and report any changes to their physicians.

How we reached these conclusions

The task force discussions focused heavily on at what age mammography should be started and how often it should be done. In addition to an in-depth review of the studies on which the USPSTF recommendations were based, we considered a review posted on the Society of Breast Imaging (SBI) Web site.8

A key point from the SBI’s review is that although breast cancer occurs less often in women under age 50, approximately 1 in 69 women are diagnosed with invasive cancer when in their 40s. Some—probably a minority— have a family history of breast cancer and thus warrant earlier screening on that basis.

Breast cancer is, therefore, an important public health concern for women ages 40 to 49. While mammography is an imperfect test, it has a demonstrated ability to find cancers at an earlier stage in this age group. The SBI statement also summarized data suggesting that the 40-to-49-year age group would experience significantly fewer lives saved by screening if the mammography interval were increased from once a year to every other year (ie, by approximately one-half—from 36% of deaths prevented with annual screening to 18% deaths prevented with screening every other year).

Screening every other year is also expected to result in fewer lives saved in women ages 50 to 69 (39% of deaths prevented by biennial screening instead of 44% to 46% with annual screening). However, this proportion of deaths prevented with more frequent (ie, annual) screening is smaller than in the younger age group. Breast cancers that arise before menopause are considered biologically more aggressive, so the longer the interval between screening tests, the lower the likelihood of detecting some of these potentially more lethal cancers.

We believe, for several reasons, that the randomized trials may have underestimated the benefit of mammography. The trials included in the USPSTF studies did not use modern mammographic techniques such as digital mammography. Some of the trials used single-view mammography, which may be less sensitive. Also, the rate of compliance with screening in these randomized trials was only about 70%, which would lead to an underestimation of the number of lives saved with mammography screening. Yet in spite of these limitations, the data continue to show a reduction in breast cancer deaths in all age categories studied.

Other issues the task force considered

Harms of screening are acceptable. We agree that the need for additional imaging or possibly breast biopsy is an acceptable consequence of screening for most women, especially when weighed against the potential benefit of improving survival. Nelson et al3 briefly discussed the risk of inducing other cancers through radiation exposure, and any such risk appears to be low enough that it is overshadowed by the reduction in the breast cancer mortality rate achieved from screening.

The USPSTF studies did not address the issue of cost, which is another potential harm of screening. However, screening mammography is relatively inexpensive compared with other potentially life-saving screening tests.

Our position differs from that of the American College of Physicians (ACP), which has endorsed the USPSTF recommendation for reduced breast cancer screening. The USPSTF has been a leading group in providing practice recommendations based on high-level evidence predominantly from randomized controlled clinical trials, and its recommendations have been consistently followed by the ACP and many of its members, including Cleveland Clinic physicians. It is, therefore, not without considerable discussion that we have come to our consensus.

Evidence for less screening was not compelling. One of our concerns about the new USPSTF recommendations is that the changes are based largely on a model analysis of the efficiency of different screening strategies rather than on randomized controlled trials comparing different strategies. We did not find this level of present evidence to be sufficiently compelling to make a change in our practice that may result in loss of lives from breast cancer.

Screening guidelines will continue to change over time as technology improves and new data are introduced. In the future, risk-assessment strategies such as incorporating genetic profiles may allow us to use factors more predictive than age to target our screening population.

While we continue to strive for better means of early detection and cancer prevention, the Cleveland Clinic task force is currently recommending yearly screening with mammography and breast examination for most women, starting at age 40.

- US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for breast cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med 2009; 151:716–726.

- US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF). Recommendation statement from USPSTF: screening for breast cancer. Medscape. http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/714016. Accessed 12/28/2009.

- Nelson HD, Tyne K, Naik A, et al. Screening for breast cancer: an update for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med 2009; 151:727–737.

- Mandelblatt JS, Cronin KA, Bailey S, et al. Effects of mammography screening under different screening schedules: model estimates of potential benefits and harms. Ann Intern Med 2009; 151:738–747.

- Semiglazov VF, Manikhas AG, Moiseenko VM, et al. Results of a prospective randomized investigation [Russia (St. Petersburg)/WHO] to evaluate the significance of self-examination for the early detection of breast cancer [in Russian]. Vopr Onkol 2003; 49:434–441. Cited by Nelson et al (see reference 3, above).

- Thomas DB, Gao DL, Ray RM, et al. Randomized trial of breast self-examination in Shanghai: final results. J Natl Cancer Inst 2002; 94:1445–1457. Cited by Nelson et al (see reference 3, above).

- Tu SP, Reisch LM, Taplin SH, Kreuter W, Elmore JG. Breast self-examination: self-reported frequency, quality, and associated outcomes. J Cancer Educ 2006; 21:175–181. Cited by Nelson et al (see reference 3, above).

- Berg WA, Hendrick E, Kopans DB, Smith RA. Frequently asked questions about mammography and the USPSTF recommendations: a guide for practitioners. Society of Breast Imaging. http://www.sbi-online.org/associations/8199/files/Detailed_Response_to_USPSTF_Guidelines-12-11-09-Berg.pdf. Accessed 12/28/2009.

Editor’s Note: This commentary, written by members of the Cleveland Clinic Breast Cancer Screening Task Force, was not independently peer-reviewed.

In November 2009, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) announced its new guidelines for breast cancer screening—and created an instant controversy by suggesting that fewer screening tests be done.1

The November 2009 update recommended that most women wait until age 50 to get their first screening mammogram instead of getting it at age 40, that they get a mammogram every other year instead of every year, and that physicians not teach their patients breast self-examination anymore. However, on December 4, 2009, the USPSTF members voted to modify the recommendation for women under age 50, stating that the decision to start screening mammography every 2 years should be individualized, taking into account the patient’s preferences after being apprised of the possible benefits and harms.2

Various professional and advocacy groups have reacted differently to the new guidelines, and as a result, women are unsure about the optimal screening for breast cancer.

NEW GUIDELINES ARE BASED ON TWO STUDIES

The USPSTF commissioned two studies, which it used to formulate the new recommendations.3,4 Its goal was to evaluate the current evidence for the efficacy of several screening tests and schedules in reducing breast cancer mortality rates.

An updated systematic review

Nelson et al3 performed a systematic review of studies of the benefit and harm of screening with mammography, clinical breast examination, and breast self-examination.

Screening mammography continued to demonstrate a reduction in deaths due to breast cancer. The risk reduction ranged from 14% to 32% in women age 50 to 69. Similarly, it was calculated to reduce the incidence of deaths due to breast cancer by 15% in women age 39 to 49. However, this younger age group has a relatively low incidence of breast cancer, and therefore, according to this analysis, 556 women need to undergo one round of screening to detect one case of invasive breast cancer, and 1,904 women need to be offered screening (over several rounds, which varied by trial) to prevent one breast cancer death.3

Most of the harm of screening in the 39-to-49-year age category was due to false-positive results, which were more common in this group than in older women. The authors calculated that after every round of screening mammography, about 84 of every 1,000 women in the younger age category need additional imaging and about 9 need a biopsy. The issue of overdiagnosis (detection of cancers that would have never been a problem in one’s lifetime) was not specifically addressed for this age category, and in different studies, estimates of overdiagnosis rates for all age groups varied widely, from less than 1% to 30%.

Beyond age 70, the authors reported the data insufficient for evaluating the benefit and harm of screening mammography.

Breast self-examination was found to offer no benefit, based largely on two randomized studies, one in St. Petersburg, Russia,5 and the other in Shanghai, China,6 both places where screening mammography was not routinely offered. These studies and one observational study in the United States7 failed to show a reduction in breast cancer mortality rates with breast self-examination.

Clinical breast examination (ie, by a health care provider) lacked sufficient data to draw conclusions.

A study based on statistical models of mammography

Mandelblatt et al4 used statistical modeling to estimate the effect of mammographic screening at various ages and at different intervals.

The authors used six statistical models previously shown to give similar qualitative estimates of the contribution of screening in reducing breast cancer mortality rates. They estimated the number of mammograms required relative to the number of cancers detected, the number of breast cancer deaths prevented, and the harms (false-positive mammograms, unnecessary biopsies, and overdiagnosis) incurred with 20 different screening strategies, ie, screening with different starting and stopping ages and at intervals of either 1 or 2 years.

They estimated that screening every other year would achieve most of the benefit of screening every year, with less harm. Looking at the different strategies and models, on average, biennial screening would, by their calculations, achieve about 81% of the mortality reduction achieved with annual screening. Compared with screening women ages 50 to 69 only, extending screening to women age 40 to 49 would reduce the cancer mortality rate by 3% more, while extending it up to age 79 would reduce it by another 7% to 8%.

In terms of harm, the models predicted more false-positive studies if screening were started before age 50 and if it were done annually rather than biennially. They also predicted that more unnecessary biopsies would be done with annual screening than with screening every 2 years. The models suggested that the risk for overdiagnosis was higher in older age groups because of higher rates of death from causes other than breast cancer, and that the overdiagnosis rate was also somewhat higher with annual than with 2-year screening.

WHAT WOULD LESS SCREENING MEAN?

Our practice has been to initiate annual screening with mammography at age 40 and to continue as long as the patient’s life expectancy is at least 10 years.

According to the models used by Mandelblatt et al,4 screening 1,000 women every year, starting at age 40 and continuing until age 84, would result in 177 to 227 life-years gained compared with no screening. In contrast, screening only women age 50 to 74 and only every other year (as advocated in the new guidelines) would entail about one-third the number of mammograms but would result in fewer life-years gained per 1,000 women screened: between 96 and 128. If we take the mean of the estimates from the six models, adherence to the new screening guidelines would be estimated to result in about 79 fewer life-years gained for every 1,000 women screened. On the other hand, each woman screened would need to undergo about 25 fewer screening mammograms in her lifetime.4

KEY POINTS ABOUT BREAST CANCER SCREENING

Together, these studies demonstrate several points about breast cancer screening.

Importantly, randomized controlled trials and model analyses continue to show that screening mammography reduces the breast cancer mortality rate.

The studies and models also reinforce the concept that those at greatest risk get the most benefit from screening. Because the incidence of breast cancer rises with age, the probability of a true-positive result is higher in women over age 50 than it is in younger women, and, therefore, the screening test performs better.

On the other hand, women at high risk of dying of other causes, such as those over age 75, achieve less benefit from screening, as some of the cancers detected in this manner may not contribute to their death even if they are not detected early.

Screening is therefore best targeted at people who are healthy but who are at sufficient risk for the disease in question to justify the screening.

CLEVELAND CLINIC’S POSITION

In December 2009, the Cleveland Clinic Breast Cancer Screening Task Force, a multidisciplinary panel of breast cancer experts, breast radiologists, and primary care providers, convened to review the literature and set forth institutional recommendations for breast cancer screening for healthy women. The authors of this paper are members of this task force. Our consensus recommendations:

- We continue to recommend annual mammography for most healthy women over age 40.

- Screening every other year is an option for older postmenopausal women, as they are likely to achieve most of the benefit of annual screening with this schedule.

- We agree with the USPSTF finding that there are insufficient data to provide evidenced-based recommendations regarding the benefits and harms of clinical breast examination. However, breast examination was done as part of the screening in many of the randomized trials of mammography and cannot easily be separated from mammography. Therefore, we believe that careful examination of the breasts remains an important consideration in the general physical examination.

- The USPSTF recommendation not to teach breast self-examination was based on studies that probably do not apply to the US population. Therefore, we continue to recommend that women be familiar with their breasts and report any changes to their physicians.

How we reached these conclusions

The task force discussions focused heavily on at what age mammography should be started and how often it should be done. In addition to an in-depth review of the studies on which the USPSTF recommendations were based, we considered a review posted on the Society of Breast Imaging (SBI) Web site.8

A key point from the SBI’s review is that although breast cancer occurs less often in women under age 50, approximately 1 in 69 women are diagnosed with invasive cancer when in their 40s. Some—probably a minority— have a family history of breast cancer and thus warrant earlier screening on that basis.

Breast cancer is, therefore, an important public health concern for women ages 40 to 49. While mammography is an imperfect test, it has a demonstrated ability to find cancers at an earlier stage in this age group. The SBI statement also summarized data suggesting that the 40-to-49-year age group would experience significantly fewer lives saved by screening if the mammography interval were increased from once a year to every other year (ie, by approximately one-half—from 36% of deaths prevented with annual screening to 18% deaths prevented with screening every other year).

Screening every other year is also expected to result in fewer lives saved in women ages 50 to 69 (39% of deaths prevented by biennial screening instead of 44% to 46% with annual screening). However, this proportion of deaths prevented with more frequent (ie, annual) screening is smaller than in the younger age group. Breast cancers that arise before menopause are considered biologically more aggressive, so the longer the interval between screening tests, the lower the likelihood of detecting some of these potentially more lethal cancers.

We believe, for several reasons, that the randomized trials may have underestimated the benefit of mammography. The trials included in the USPSTF studies did not use modern mammographic techniques such as digital mammography. Some of the trials used single-view mammography, which may be less sensitive. Also, the rate of compliance with screening in these randomized trials was only about 70%, which would lead to an underestimation of the number of lives saved with mammography screening. Yet in spite of these limitations, the data continue to show a reduction in breast cancer deaths in all age categories studied.

Other issues the task force considered

Harms of screening are acceptable. We agree that the need for additional imaging or possibly breast biopsy is an acceptable consequence of screening for most women, especially when weighed against the potential benefit of improving survival. Nelson et al3 briefly discussed the risk of inducing other cancers through radiation exposure, and any such risk appears to be low enough that it is overshadowed by the reduction in the breast cancer mortality rate achieved from screening.

The USPSTF studies did not address the issue of cost, which is another potential harm of screening. However, screening mammography is relatively inexpensive compared with other potentially life-saving screening tests.

Our position differs from that of the American College of Physicians (ACP), which has endorsed the USPSTF recommendation for reduced breast cancer screening. The USPSTF has been a leading group in providing practice recommendations based on high-level evidence predominantly from randomized controlled clinical trials, and its recommendations have been consistently followed by the ACP and many of its members, including Cleveland Clinic physicians. It is, therefore, not without considerable discussion that we have come to our consensus.

Evidence for less screening was not compelling. One of our concerns about the new USPSTF recommendations is that the changes are based largely on a model analysis of the efficiency of different screening strategies rather than on randomized controlled trials comparing different strategies. We did not find this level of present evidence to be sufficiently compelling to make a change in our practice that may result in loss of lives from breast cancer.

Screening guidelines will continue to change over time as technology improves and new data are introduced. In the future, risk-assessment strategies such as incorporating genetic profiles may allow us to use factors more predictive than age to target our screening population.

While we continue to strive for better means of early detection and cancer prevention, the Cleveland Clinic task force is currently recommending yearly screening with mammography and breast examination for most women, starting at age 40.

Editor’s Note: This commentary, written by members of the Cleveland Clinic Breast Cancer Screening Task Force, was not independently peer-reviewed.

In November 2009, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) announced its new guidelines for breast cancer screening—and created an instant controversy by suggesting that fewer screening tests be done.1

The November 2009 update recommended that most women wait until age 50 to get their first screening mammogram instead of getting it at age 40, that they get a mammogram every other year instead of every year, and that physicians not teach their patients breast self-examination anymore. However, on December 4, 2009, the USPSTF members voted to modify the recommendation for women under age 50, stating that the decision to start screening mammography every 2 years should be individualized, taking into account the patient’s preferences after being apprised of the possible benefits and harms.2

Various professional and advocacy groups have reacted differently to the new guidelines, and as a result, women are unsure about the optimal screening for breast cancer.

NEW GUIDELINES ARE BASED ON TWO STUDIES

The USPSTF commissioned two studies, which it used to formulate the new recommendations.3,4 Its goal was to evaluate the current evidence for the efficacy of several screening tests and schedules in reducing breast cancer mortality rates.

An updated systematic review

Nelson et al3 performed a systematic review of studies of the benefit and harm of screening with mammography, clinical breast examination, and breast self-examination.

Screening mammography continued to demonstrate a reduction in deaths due to breast cancer. The risk reduction ranged from 14% to 32% in women age 50 to 69. Similarly, it was calculated to reduce the incidence of deaths due to breast cancer by 15% in women age 39 to 49. However, this younger age group has a relatively low incidence of breast cancer, and therefore, according to this analysis, 556 women need to undergo one round of screening to detect one case of invasive breast cancer, and 1,904 women need to be offered screening (over several rounds, which varied by trial) to prevent one breast cancer death.3

Most of the harm of screening in the 39-to-49-year age category was due to false-positive results, which were more common in this group than in older women. The authors calculated that after every round of screening mammography, about 84 of every 1,000 women in the younger age category need additional imaging and about 9 need a biopsy. The issue of overdiagnosis (detection of cancers that would have never been a problem in one’s lifetime) was not specifically addressed for this age category, and in different studies, estimates of overdiagnosis rates for all age groups varied widely, from less than 1% to 30%.

Beyond age 70, the authors reported the data insufficient for evaluating the benefit and harm of screening mammography.

Breast self-examination was found to offer no benefit, based largely on two randomized studies, one in St. Petersburg, Russia,5 and the other in Shanghai, China,6 both places where screening mammography was not routinely offered. These studies and one observational study in the United States7 failed to show a reduction in breast cancer mortality rates with breast self-examination.

Clinical breast examination (ie, by a health care provider) lacked sufficient data to draw conclusions.

A study based on statistical models of mammography

Mandelblatt et al4 used statistical modeling to estimate the effect of mammographic screening at various ages and at different intervals.

The authors used six statistical models previously shown to give similar qualitative estimates of the contribution of screening in reducing breast cancer mortality rates. They estimated the number of mammograms required relative to the number of cancers detected, the number of breast cancer deaths prevented, and the harms (false-positive mammograms, unnecessary biopsies, and overdiagnosis) incurred with 20 different screening strategies, ie, screening with different starting and stopping ages and at intervals of either 1 or 2 years.

They estimated that screening every other year would achieve most of the benefit of screening every year, with less harm. Looking at the different strategies and models, on average, biennial screening would, by their calculations, achieve about 81% of the mortality reduction achieved with annual screening. Compared with screening women ages 50 to 69 only, extending screening to women age 40 to 49 would reduce the cancer mortality rate by 3% more, while extending it up to age 79 would reduce it by another 7% to 8%.

In terms of harm, the models predicted more false-positive studies if screening were started before age 50 and if it were done annually rather than biennially. They also predicted that more unnecessary biopsies would be done with annual screening than with screening every 2 years. The models suggested that the risk for overdiagnosis was higher in older age groups because of higher rates of death from causes other than breast cancer, and that the overdiagnosis rate was also somewhat higher with annual than with 2-year screening.

WHAT WOULD LESS SCREENING MEAN?

Our practice has been to initiate annual screening with mammography at age 40 and to continue as long as the patient’s life expectancy is at least 10 years.

According to the models used by Mandelblatt et al,4 screening 1,000 women every year, starting at age 40 and continuing until age 84, would result in 177 to 227 life-years gained compared with no screening. In contrast, screening only women age 50 to 74 and only every other year (as advocated in the new guidelines) would entail about one-third the number of mammograms but would result in fewer life-years gained per 1,000 women screened: between 96 and 128. If we take the mean of the estimates from the six models, adherence to the new screening guidelines would be estimated to result in about 79 fewer life-years gained for every 1,000 women screened. On the other hand, each woman screened would need to undergo about 25 fewer screening mammograms in her lifetime.4

KEY POINTS ABOUT BREAST CANCER SCREENING

Together, these studies demonstrate several points about breast cancer screening.

Importantly, randomized controlled trials and model analyses continue to show that screening mammography reduces the breast cancer mortality rate.

The studies and models also reinforce the concept that those at greatest risk get the most benefit from screening. Because the incidence of breast cancer rises with age, the probability of a true-positive result is higher in women over age 50 than it is in younger women, and, therefore, the screening test performs better.

On the other hand, women at high risk of dying of other causes, such as those over age 75, achieve less benefit from screening, as some of the cancers detected in this manner may not contribute to their death even if they are not detected early.

Screening is therefore best targeted at people who are healthy but who are at sufficient risk for the disease in question to justify the screening.

CLEVELAND CLINIC’S POSITION

In December 2009, the Cleveland Clinic Breast Cancer Screening Task Force, a multidisciplinary panel of breast cancer experts, breast radiologists, and primary care providers, convened to review the literature and set forth institutional recommendations for breast cancer screening for healthy women. The authors of this paper are members of this task force. Our consensus recommendations:

- We continue to recommend annual mammography for most healthy women over age 40.

- Screening every other year is an option for older postmenopausal women, as they are likely to achieve most of the benefit of annual screening with this schedule.

- We agree with the USPSTF finding that there are insufficient data to provide evidenced-based recommendations regarding the benefits and harms of clinical breast examination. However, breast examination was done as part of the screening in many of the randomized trials of mammography and cannot easily be separated from mammography. Therefore, we believe that careful examination of the breasts remains an important consideration in the general physical examination.

- The USPSTF recommendation not to teach breast self-examination was based on studies that probably do not apply to the US population. Therefore, we continue to recommend that women be familiar with their breasts and report any changes to their physicians.

How we reached these conclusions

The task force discussions focused heavily on at what age mammography should be started and how often it should be done. In addition to an in-depth review of the studies on which the USPSTF recommendations were based, we considered a review posted on the Society of Breast Imaging (SBI) Web site.8

A key point from the SBI’s review is that although breast cancer occurs less often in women under age 50, approximately 1 in 69 women are diagnosed with invasive cancer when in their 40s. Some—probably a minority— have a family history of breast cancer and thus warrant earlier screening on that basis.

Breast cancer is, therefore, an important public health concern for women ages 40 to 49. While mammography is an imperfect test, it has a demonstrated ability to find cancers at an earlier stage in this age group. The SBI statement also summarized data suggesting that the 40-to-49-year age group would experience significantly fewer lives saved by screening if the mammography interval were increased from once a year to every other year (ie, by approximately one-half—from 36% of deaths prevented with annual screening to 18% deaths prevented with screening every other year).

Screening every other year is also expected to result in fewer lives saved in women ages 50 to 69 (39% of deaths prevented by biennial screening instead of 44% to 46% with annual screening). However, this proportion of deaths prevented with more frequent (ie, annual) screening is smaller than in the younger age group. Breast cancers that arise before menopause are considered biologically more aggressive, so the longer the interval between screening tests, the lower the likelihood of detecting some of these potentially more lethal cancers.

We believe, for several reasons, that the randomized trials may have underestimated the benefit of mammography. The trials included in the USPSTF studies did not use modern mammographic techniques such as digital mammography. Some of the trials used single-view mammography, which may be less sensitive. Also, the rate of compliance with screening in these randomized trials was only about 70%, which would lead to an underestimation of the number of lives saved with mammography screening. Yet in spite of these limitations, the data continue to show a reduction in breast cancer deaths in all age categories studied.

Other issues the task force considered

Harms of screening are acceptable. We agree that the need for additional imaging or possibly breast biopsy is an acceptable consequence of screening for most women, especially when weighed against the potential benefit of improving survival. Nelson et al3 briefly discussed the risk of inducing other cancers through radiation exposure, and any such risk appears to be low enough that it is overshadowed by the reduction in the breast cancer mortality rate achieved from screening.

The USPSTF studies did not address the issue of cost, which is another potential harm of screening. However, screening mammography is relatively inexpensive compared with other potentially life-saving screening tests.

Our position differs from that of the American College of Physicians (ACP), which has endorsed the USPSTF recommendation for reduced breast cancer screening. The USPSTF has been a leading group in providing practice recommendations based on high-level evidence predominantly from randomized controlled clinical trials, and its recommendations have been consistently followed by the ACP and many of its members, including Cleveland Clinic physicians. It is, therefore, not without considerable discussion that we have come to our consensus.

Evidence for less screening was not compelling. One of our concerns about the new USPSTF recommendations is that the changes are based largely on a model analysis of the efficiency of different screening strategies rather than on randomized controlled trials comparing different strategies. We did not find this level of present evidence to be sufficiently compelling to make a change in our practice that may result in loss of lives from breast cancer.

Screening guidelines will continue to change over time as technology improves and new data are introduced. In the future, risk-assessment strategies such as incorporating genetic profiles may allow us to use factors more predictive than age to target our screening population.

While we continue to strive for better means of early detection and cancer prevention, the Cleveland Clinic task force is currently recommending yearly screening with mammography and breast examination for most women, starting at age 40.

- US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for breast cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med 2009; 151:716–726.

- US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF). Recommendation statement from USPSTF: screening for breast cancer. Medscape. http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/714016. Accessed 12/28/2009.

- Nelson HD, Tyne K, Naik A, et al. Screening for breast cancer: an update for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med 2009; 151:727–737.

- Mandelblatt JS, Cronin KA, Bailey S, et al. Effects of mammography screening under different screening schedules: model estimates of potential benefits and harms. Ann Intern Med 2009; 151:738–747.

- Semiglazov VF, Manikhas AG, Moiseenko VM, et al. Results of a prospective randomized investigation [Russia (St. Petersburg)/WHO] to evaluate the significance of self-examination for the early detection of breast cancer [in Russian]. Vopr Onkol 2003; 49:434–441. Cited by Nelson et al (see reference 3, above).

- Thomas DB, Gao DL, Ray RM, et al. Randomized trial of breast self-examination in Shanghai: final results. J Natl Cancer Inst 2002; 94:1445–1457. Cited by Nelson et al (see reference 3, above).

- Tu SP, Reisch LM, Taplin SH, Kreuter W, Elmore JG. Breast self-examination: self-reported frequency, quality, and associated outcomes. J Cancer Educ 2006; 21:175–181. Cited by Nelson et al (see reference 3, above).

- Berg WA, Hendrick E, Kopans DB, Smith RA. Frequently asked questions about mammography and the USPSTF recommendations: a guide for practitioners. Society of Breast Imaging. http://www.sbi-online.org/associations/8199/files/Detailed_Response_to_USPSTF_Guidelines-12-11-09-Berg.pdf. Accessed 12/28/2009.

- US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for breast cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med 2009; 151:716–726.

- US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF). Recommendation statement from USPSTF: screening for breast cancer. Medscape. http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/714016. Accessed 12/28/2009.

- Nelson HD, Tyne K, Naik A, et al. Screening for breast cancer: an update for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med 2009; 151:727–737.

- Mandelblatt JS, Cronin KA, Bailey S, et al. Effects of mammography screening under different screening schedules: model estimates of potential benefits and harms. Ann Intern Med 2009; 151:738–747.

- Semiglazov VF, Manikhas AG, Moiseenko VM, et al. Results of a prospective randomized investigation [Russia (St. Petersburg)/WHO] to evaluate the significance of self-examination for the early detection of breast cancer [in Russian]. Vopr Onkol 2003; 49:434–441. Cited by Nelson et al (see reference 3, above).

- Thomas DB, Gao DL, Ray RM, et al. Randomized trial of breast self-examination in Shanghai: final results. J Natl Cancer Inst 2002; 94:1445–1457. Cited by Nelson et al (see reference 3, above).

- Tu SP, Reisch LM, Taplin SH, Kreuter W, Elmore JG. Breast self-examination: self-reported frequency, quality, and associated outcomes. J Cancer Educ 2006; 21:175–181. Cited by Nelson et al (see reference 3, above).

- Berg WA, Hendrick E, Kopans DB, Smith RA. Frequently asked questions about mammography and the USPSTF recommendations: a guide for practitioners. Society of Breast Imaging. http://www.sbi-online.org/associations/8199/files/Detailed_Response_to_USPSTF_Guidelines-12-11-09-Berg.pdf. Accessed 12/28/2009.

Overview of breast cancer staging and surgical treatment options

In the late 19th century, breast cancer was considered a fatal disease. That began to change in the 1880s when W.S. Halsted described the radical mastectomy as the way to treat patients with breast cancer.1 This aggressive surgical treatment—in which the breast, axillary lymph nodes, and chest muscles are all removed—remained the standard of care throughout much of the 20th century; as late as the early 1970s, nearly half (48%) of breast cancer patients were treated with radical mastectomy. During the 1970s, however, the Halsted radical mastectomy was largely abandoned for a less-disfiguring muscle-sparing technique called the modified radical mastectomy; by 1981, only 3% of patients underwent the Halsted mastectomy.2

The 1980s heralded even more minimally invasive techniques with the advent of breast conservation therapy, in which an incision is made over the tumor and the tumor is completely removed with negative margins, leaving behind normal breast tissue. (This procedure has been referred to by many different names, including definitive excision, lumpectomy, quadrantectomy, and partial mastectomy; since they all mean the same thing, for clarity and consistency this article will use “breast conservation therapy” throughout.) During the 1990s, surgical invasiveness was further minimized with the emergence of sentinel lymph node excision.

An important contributor to this evolution in the standard of breast cancer therapy since the 1970s has been the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (NSABP), a National Cancer Institute–funded clinical trials cooperative group. NSABP studies have been the driving force to show that the extent of surgery could be reduced without compromising outcome.3 These studies, along with several other trials, have resulted in a marked reduction in surgical aggressiveness and a multitude of adjuvant therapies for women with breast cancer. This article will briefly explore where this evolution has brought us in terms of the surgical options available for treatment of breast cancer today. We also discuss other key components in the management of women with newly diagnosed breast cancer, including cancer staging, patient counseling, and assessment of axillary lymph nodes.

BREAST CANCER CLASSIFICATION AND STAGING

Pathologic classification

Cancer staging

A simpler method relies on the National Cancer Institute’s SEER (Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results) summary staging system.5 This system classifies tumors as “localized” (contained in the breast, either in situ or invasive), “regional” (identified in regional lymph nodes), or “metastatic” (spread to distant organ systems).

Of course, patients cannot be told their stage until after surgery, when a final pathologic report detailing tumor size and nodal status is available. Some patients will never be definitively staged—for instance, those who undergo neoadjuvant chemotherapy for locally advanced disease prior to lymph node dissection, or those who do not have a metastatic work-up. The metastatic work-up involves ordering of additional tests to assess for metastasis, but only when prompted by specific patient symptoms. Thus, if the patient has shortness of breath, a chest radiograph or a chest computed tomograph (CT) needs to be ordered; for elevated liver enzymes, CTs of the abdomen and pelvis are ordered; for central nervous system symptoms, brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is ordered; and for back pain or bone pain, a bone scan is ordered to rule out metastatic disease to bone.

INITIAL PATIENT ASSESSMENT AND COUNSELING

Relationship-building is fundamental

Following an initial diagnosis of breast cancer, the patient must undergo an assessment for local and systemic disease. The surgeon, as a member of a multi-disciplinary breast cancer treatment team, often spearheads this initial assessment. This first visit must go beyond mere clinical evaluation, however, and include thorough discussion and relationship-building with the patient, as this early meeting establishes a relationship with the patient that will carry through her entire process of cancer care. For a true understanding between patient and surgeon to occur, it is critical for patients to be comfortable in sharing their fears, expectations, and lifestyle needs. Following a diagnosis of breast cancer, the initial reactions women go through include both fear and realization of one’s own mortality. Although these responses may no longer be justified by the reality of patient outcomes in most cases, they are normal and fully understandable reactions. For this reason, clinicians must be sensitive to these reactions while being supportive about the efficacy of the treatment options available.

History, breast exam, and review of imaging studies

In addition to the establishment of communication and understanding, the vital components of this first meeting include a detailed medical history, a clinical breast examination, a review of imaging studies, and a discussion of treatment options.

The history should include all aspects of the patient’s reproductive history, her family history of breast cancer, and any comorbidities and medications being taken.

The clinical breast examination should give special attention to the shape (asymmetry), appearance (eg, dimpling, erythema, nipple inversion), and overall feel of the breasts. A palpable mass must be recorded in terms of its location in relation to the skin, the nipple-areola complex, and the chest wall, as well as the quadrant of the breast in which it lies. The regional lymph node basins need to be examined closely, including the axilla and supraclavicular nodes.

Imaging studies also need to be reviewed closely. Patients today frequently present with multiple types of imaging studies, including mammography, ultrasonography, and MRI. Occasionally patients also may present with nuclear medicine exam results, CTs, thermographic images, positron emission tomography studies, and bone scans. All radiology studies need to be reviewed closely and examined in the context of what they were ordered for and what utility they potentially provide.

Treatment options: Surgery is first step in most cases

Once the above components are addressed, the patient should be engaged in a discussion of treatment options. Most women with breast cancer will undergo some type of surgery in conjunction with radiation therapy, chemotherapy, or both. Generally, surgery takes place as the first part of a multiple-component therapy plan. The main goal of surgery is to remove the cancer and accurately define the stage of the disease.

Consider plastic surgery consultation

When indicated and available, consultation with a plastic surgery team may be appropriate at this stage to provide support and comfort to the patient so that she better understands her options for breast reconstruction along with those for breast cancer surgery. Recent data show that most general surgeons do not discuss reconstruction with their breast cancer patients before surgical breast cancer therapy, but that when such discussions do occur, they significantly influence patients’ treatment choices.6 Giving patients the chance to learn about reconstructive options through discussion with a plastic surgeon represents a good opportunity to provide complete patient care in a multidisciplinary way.

OVERVIEW OF SURGICAL OPTIONS

Two general approaches, no difference in survival

The two mainstays of surgical treatment today are (1) breast conservation therapy, generally followed by total or partial breast irradiation, and (2) mastectomy.

The prospective randomized trial data obtained from the NSABP trials have demonstrated no survival differences between patients with early-stage breast cancer based on whether they were treated with breast conservation therapy or mastectomy.2 Beyond this fundamental issue of survival, there are a number of nuances, many of them logistical, related to the success of either operation that the clinician must keep in mind when presenting these surgical choices to patients. These considerations are reviewed below.

Breast conservation therapy

For breast conservation therapy, the ratio of tumor size to breast size must be small enough to ensure complete tumor removal with an acceptable cosmetic outcome. In general, it is estimated that up to 25% of the breast can be removed while still ensuring a “good” cosmetic outcome. Advances in closure techniques allowing for more tissue to be removed with even better cosmetic outcomes are known as oncoplastic closure. These techniques are mostly performed by breast oncologic surgeons, often in consultation or conjunction with plastic surgeons. (Reconstructive options following breast conservation therapy are reviewed in a subsequent article in this supplement.) Additionally, the patient must agree and be deemed a candidate for postoperative radiation therapy. The patient must be able to be followed clinically to enable early detection of a potential local recurrence.

Mastectomy

A second surgical option for patients is mastectomy. Today “mastectomy” can refer to any of several subtypes of surgical procedures, which are outlined below and should be considered on a patient-by-patient basis. Mastectomy is appropriate when breast conservation therapy is not possible (due to a large or multicentric tumor) or would result in poor cosmetic outcome, or when the patient specifically chooses a mastectomy.

Simple mastectomy involves removal of the breast only, without removal of lymph nodes. Either of the incisions depicted in the left and center panels of Figure 3 can be used. Both modified radical mastectomy and simple mastectomy involve removal of the nipple and areola (nipple-areola complex).

Skin-sparing mastectomy (Figure 3, center) is performed when a patient is undergoing immediate breast reconstruction (using either a silicone or saline implant or autologous tissue). The goal is to remove all breast tissue, along with the nipple-areola complex, while preserving as much viable skin as possible to optimize the cosmetic outcome.7,8

Nipple-areola–sparing mastectomy. There is increasing experience with attempts to preserve the nipple-areola complex. These procedures attempt to preserve either the whole complex, termed nipple-areola–sparing mastectomy (sometimes called simply nipple-sparing mastectomy) (Figure 3, right), or just the areola, with removal of the nipple (areola-sparing mastectomy). These procedures are also performed in a skin-sparing fashion.

There is some controversy surrounding these techniques to spare the nipple and/or areola, including debate over which technique.nipple-areola–sparing mastectomy or areola-sparing mastectomy.may be more oncologically safe. Currently the literature shows that both are probably safe oncologic alternatives for remote tumors that do not have an extensive intraductal component. Generally, frozen sections are performed intraoperatively on the retroareola tissue to document that there is no evidence of tumor.9

SURGICAL COMPLICATIONS

Breast procedures are fairly safe operations, but every operation has a risk of complications. Reported complications of breast surgery include the following:

- Bleeding

- Infection (including both cellulitis and abscess)

- Seroma

- Arm morbidity (including lymphedema)

- Phantom breast syndrome

- Injury to the motor nerves.

Seromas often occur in patients after mastectomy or lymph node surgery. Prolonged lymphatic drainage is usually exacerbated by extensive axillary node involvement and obesity.

Arm morbidity can present in different ways. Lymphedema is the most common manifestation, with reported incidences of approximately 15% to 20% when axillary lymph node dissection is performed versus 7% when sentinel lymph node biopsy is done.10 The risk of lymphedema can be reduced by avoiding blood pressure measurements, venipunctures, and intravenous insertions in the arm on the side of the operation, as well as by wearing a compression sleeve on the affected arm during airplane flights.

Phantom breast syndrome is rare but may manifest as pain that may also involve itching, nipple sensation, erotic sensations, or premenstrual-type soreness.

Many surgeons have historically removed the intercostobrachial nerves but are now trying to preserve these nerves, which when removed cause loss of sensation in the upper inner arm. Although rare, nerve injury during an axillary procedure has been reported. It may involve the long thoracic nerve (denervating the serratus anterior muscle and causing a winged scapula) or the thoracodorsal bundle (denervating the latissimus dorsi muscle and causing difficulty with arm/shoulder adduction).

LOCAL CANCER RECURRENCE

Among women undergoing mastectomy for breast cancer, 10% to 15% will have a recurrence of cancer in the chest wall or axillary lymph nodes within 10 years.11 Similarly, among women undergoing breast conservation therapy plus radiation therapy, 10% to 15% will have in-breast cancer recurrence or recurrence in axillary lymph nodes within 10 years, although women who undergo breast conservation therapy without radiation have a much higher recurrence rate.11Considerations for screening the surgically altered breast are discussed in the previous article in this supplement.

ASSESSMENT OF AXILLARY LYMPH NODES FOR METASTASIS

Even when patients have a known histologic diagnosis of breast cancer and have made a firm decision regarding the surgical option for removal of their cancer, the status of their axillary lymph nodes remains a great unanswered question until after the surgical procedure is completed. Lymph node status—ie, determining whether the cancer has spread to the axillary lymph nodes—still serves as the critical determinant for guiding adjuvant treatment, predicting survival, and assessing the risk of recurrence.

Axillary lymph node dissection

The standard approach for evaluating lymph node status has been a complete dissection of the axillary space, or axillary lymph node dissection. As briefly noted above, the axillary lymph nodes are anatomically classified into three levels as defined by their location relative to the pectoralis minor muscle. The extent of a nodal dissection can be defined by the number of nodes removed.

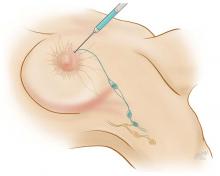

Sentinel node biopsy: A less-invasive alternative

Axillary lymph node dissection has been called into question over the last 15 years due to its invasiveness and the potential morbidity associated with it (including lymphedema and paresthesias). As a result, sentinel lymph node biopsy, a minimally invasive technique for identifying axillary metastasis, was developed to avoid the need for (and risk of complications from) axillary lymph node dissection in patients who have a low probability of axillary metastasis.

Overall, however, it is now accepted that intraoperative lymph node mapping with sentinel lymphadenectomy is an effective and minimally invasive alternative to axillary lymph node dissection for identifying nodes containing metastases.

CONCLUSIONS

Decisions surrounding the choice of breast surgery procedure must be individualized to the patient and her desires and based on comprehensive patient evaluation and thorough patient counseling. Optimal results for the patient—oncologically, psychologically, and in terms of cosmetic outcomes—require consultation and collaboration among general surgeons, medical oncologists, genetic counselors, radiation oncologists, radiologists, and plastic surgeons to clarify the risks and benefits of various intervention options. Striving for this multidisciplinary collaboration will promote optimal patient management and the most favorable clinical outcomes.

- Bland CS. The Halsted mastectomy: present illness and past history. West J Med 1981; 134:549–555.

- Frykberg ER, Bland KI. Evolution of surgical principles and techniques for the management of breast cancer. In: Bland KI, Copeland EM III, eds. The Breast: Comprehensive Management of Benign and Malignant Disorders. 3rd ed. St. Louis, MO: Saunders; 2004:759–785.

- Newman LA, Mamounas EP. Review of breast cancer clinical trials conducted by the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast Project. Surg Clin N Am 2007; 87:279–305.

- Greene FL, Page DL, Fleming ID, et al, eds. Breast. In: AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 6th ed. New York, NY: Springer; 2002:223–240.

- Young JJ, Roffers S, Gloeckler Ries L, et al. SEER Summary Staging Manual 2000: Codes and Coding Instructions. NIH Publication No. 01-4969. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health; 2000.

- Alderman AK, Hawley ST, Waljee J, Mujahid M, Morrow M, Katz SJ. Understanding the impact of breast reconstruction on the surgical decision-making process for breast cancer. Cancer 2007; 112:489–494.

- Toth BA, Lappert P. Modified skin incisions for mastectomy: the need for plastic surgical input in preoperative planning. Plast Reconstr Surg 1991; 87:1048–1053.

- Cunnick GH, Mokbel K. Skin-sparing mastectomy. Am J Surg 2004; 188:78–84.

- Crowe JP Jr, Kim JA, Yetman R, et al. Nipple-sparing mastectomy: technique and results of 54 procedures. Arch Surg 2004; 139:148–150.

- Mansel RE, Fallowfield L, Kissin M, et al. Randomized multicenter trial of sentinel node biopsy versus standard axillary treatment in operable breast cancer: the ALMANAC Trial. J Natl Cancer Inst 2006; 98:599–609.

- Jacobson JA, Danforth DN, Cowan KH, et al. Ten-year results of a comparison of conservation with mastectomy in the treatment of stage I and II breast cancer. N Engl J Med 1995; 332:907–911.

- Tanis PJ, Nieweg OE, Valdés Olmos RA, et al. History of sentinel node and validation of the technique. Breast Cancer Res 2001; 3:109–112.

- Chagpar AB, Martin RC, Scoggins CR, et al. Factors predicting failure to identify a sentinel lymph node in breast cancer. Surgery 2005; 138:56–63.

- McMasters KM, Wong SL, Chao C, et al. Defining the optimal surgeon experience for breast cancer sentinel lymph node biopsy: a model for implementation of new surgical techniques. Ann Surg 2001; 234:292–300.

In the late 19th century, breast cancer was considered a fatal disease. That began to change in the 1880s when W.S. Halsted described the radical mastectomy as the way to treat patients with breast cancer.1 This aggressive surgical treatment—in which the breast, axillary lymph nodes, and chest muscles are all removed—remained the standard of care throughout much of the 20th century; as late as the early 1970s, nearly half (48%) of breast cancer patients were treated with radical mastectomy. During the 1970s, however, the Halsted radical mastectomy was largely abandoned for a less-disfiguring muscle-sparing technique called the modified radical mastectomy; by 1981, only 3% of patients underwent the Halsted mastectomy.2

The 1980s heralded even more minimally invasive techniques with the advent of breast conservation therapy, in which an incision is made over the tumor and the tumor is completely removed with negative margins, leaving behind normal breast tissue. (This procedure has been referred to by many different names, including definitive excision, lumpectomy, quadrantectomy, and partial mastectomy; since they all mean the same thing, for clarity and consistency this article will use “breast conservation therapy” throughout.) During the 1990s, surgical invasiveness was further minimized with the emergence of sentinel lymph node excision.

An important contributor to this evolution in the standard of breast cancer therapy since the 1970s has been the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (NSABP), a National Cancer Institute–funded clinical trials cooperative group. NSABP studies have been the driving force to show that the extent of surgery could be reduced without compromising outcome.3 These studies, along with several other trials, have resulted in a marked reduction in surgical aggressiveness and a multitude of adjuvant therapies for women with breast cancer. This article will briefly explore where this evolution has brought us in terms of the surgical options available for treatment of breast cancer today. We also discuss other key components in the management of women with newly diagnosed breast cancer, including cancer staging, patient counseling, and assessment of axillary lymph nodes.

BREAST CANCER CLASSIFICATION AND STAGING

Pathologic classification

Cancer staging

A simpler method relies on the National Cancer Institute’s SEER (Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results) summary staging system.5 This system classifies tumors as “localized” (contained in the breast, either in situ or invasive), “regional” (identified in regional lymph nodes), or “metastatic” (spread to distant organ systems).

Of course, patients cannot be told their stage until after surgery, when a final pathologic report detailing tumor size and nodal status is available. Some patients will never be definitively staged—for instance, those who undergo neoadjuvant chemotherapy for locally advanced disease prior to lymph node dissection, or those who do not have a metastatic work-up. The metastatic work-up involves ordering of additional tests to assess for metastasis, but only when prompted by specific patient symptoms. Thus, if the patient has shortness of breath, a chest radiograph or a chest computed tomograph (CT) needs to be ordered; for elevated liver enzymes, CTs of the abdomen and pelvis are ordered; for central nervous system symptoms, brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is ordered; and for back pain or bone pain, a bone scan is ordered to rule out metastatic disease to bone.

INITIAL PATIENT ASSESSMENT AND COUNSELING

Relationship-building is fundamental

Following an initial diagnosis of breast cancer, the patient must undergo an assessment for local and systemic disease. The surgeon, as a member of a multi-disciplinary breast cancer treatment team, often spearheads this initial assessment. This first visit must go beyond mere clinical evaluation, however, and include thorough discussion and relationship-building with the patient, as this early meeting establishes a relationship with the patient that will carry through her entire process of cancer care. For a true understanding between patient and surgeon to occur, it is critical for patients to be comfortable in sharing their fears, expectations, and lifestyle needs. Following a diagnosis of breast cancer, the initial reactions women go through include both fear and realization of one’s own mortality. Although these responses may no longer be justified by the reality of patient outcomes in most cases, they are normal and fully understandable reactions. For this reason, clinicians must be sensitive to these reactions while being supportive about the efficacy of the treatment options available.

History, breast exam, and review of imaging studies

In addition to the establishment of communication and understanding, the vital components of this first meeting include a detailed medical history, a clinical breast examination, a review of imaging studies, and a discussion of treatment options.

The history should include all aspects of the patient’s reproductive history, her family history of breast cancer, and any comorbidities and medications being taken.

The clinical breast examination should give special attention to the shape (asymmetry), appearance (eg, dimpling, erythema, nipple inversion), and overall feel of the breasts. A palpable mass must be recorded in terms of its location in relation to the skin, the nipple-areola complex, and the chest wall, as well as the quadrant of the breast in which it lies. The regional lymph node basins need to be examined closely, including the axilla and supraclavicular nodes.

Imaging studies also need to be reviewed closely. Patients today frequently present with multiple types of imaging studies, including mammography, ultrasonography, and MRI. Occasionally patients also may present with nuclear medicine exam results, CTs, thermographic images, positron emission tomography studies, and bone scans. All radiology studies need to be reviewed closely and examined in the context of what they were ordered for and what utility they potentially provide.

Treatment options: Surgery is first step in most cases

Once the above components are addressed, the patient should be engaged in a discussion of treatment options. Most women with breast cancer will undergo some type of surgery in conjunction with radiation therapy, chemotherapy, or both. Generally, surgery takes place as the first part of a multiple-component therapy plan. The main goal of surgery is to remove the cancer and accurately define the stage of the disease.

Consider plastic surgery consultation

When indicated and available, consultation with a plastic surgery team may be appropriate at this stage to provide support and comfort to the patient so that she better understands her options for breast reconstruction along with those for breast cancer surgery. Recent data show that most general surgeons do not discuss reconstruction with their breast cancer patients before surgical breast cancer therapy, but that when such discussions do occur, they significantly influence patients’ treatment choices.6 Giving patients the chance to learn about reconstructive options through discussion with a plastic surgeon represents a good opportunity to provide complete patient care in a multidisciplinary way.

OVERVIEW OF SURGICAL OPTIONS

Two general approaches, no difference in survival

The two mainstays of surgical treatment today are (1) breast conservation therapy, generally followed by total or partial breast irradiation, and (2) mastectomy.

The prospective randomized trial data obtained from the NSABP trials have demonstrated no survival differences between patients with early-stage breast cancer based on whether they were treated with breast conservation therapy or mastectomy.2 Beyond this fundamental issue of survival, there are a number of nuances, many of them logistical, related to the success of either operation that the clinician must keep in mind when presenting these surgical choices to patients. These considerations are reviewed below.

Breast conservation therapy

For breast conservation therapy, the ratio of tumor size to breast size must be small enough to ensure complete tumor removal with an acceptable cosmetic outcome. In general, it is estimated that up to 25% of the breast can be removed while still ensuring a “good” cosmetic outcome. Advances in closure techniques allowing for more tissue to be removed with even better cosmetic outcomes are known as oncoplastic closure. These techniques are mostly performed by breast oncologic surgeons, often in consultation or conjunction with plastic surgeons. (Reconstructive options following breast conservation therapy are reviewed in a subsequent article in this supplement.) Additionally, the patient must agree and be deemed a candidate for postoperative radiation therapy. The patient must be able to be followed clinically to enable early detection of a potential local recurrence.

Mastectomy

A second surgical option for patients is mastectomy. Today “mastectomy” can refer to any of several subtypes of surgical procedures, which are outlined below and should be considered on a patient-by-patient basis. Mastectomy is appropriate when breast conservation therapy is not possible (due to a large or multicentric tumor) or would result in poor cosmetic outcome, or when the patient specifically chooses a mastectomy.

Simple mastectomy involves removal of the breast only, without removal of lymph nodes. Either of the incisions depicted in the left and center panels of Figure 3 can be used. Both modified radical mastectomy and simple mastectomy involve removal of the nipple and areola (nipple-areola complex).

Skin-sparing mastectomy (Figure 3, center) is performed when a patient is undergoing immediate breast reconstruction (using either a silicone or saline implant or autologous tissue). The goal is to remove all breast tissue, along with the nipple-areola complex, while preserving as much viable skin as possible to optimize the cosmetic outcome.7,8

Nipple-areola–sparing mastectomy. There is increasing experience with attempts to preserve the nipple-areola complex. These procedures attempt to preserve either the whole complex, termed nipple-areola–sparing mastectomy (sometimes called simply nipple-sparing mastectomy) (Figure 3, right), or just the areola, with removal of the nipple (areola-sparing mastectomy). These procedures are also performed in a skin-sparing fashion.

There is some controversy surrounding these techniques to spare the nipple and/or areola, including debate over which technique.nipple-areola–sparing mastectomy or areola-sparing mastectomy.may be more oncologically safe. Currently the literature shows that both are probably safe oncologic alternatives for remote tumors that do not have an extensive intraductal component. Generally, frozen sections are performed intraoperatively on the retroareola tissue to document that there is no evidence of tumor.9

SURGICAL COMPLICATIONS

Breast procedures are fairly safe operations, but every operation has a risk of complications. Reported complications of breast surgery include the following:

- Bleeding

- Infection (including both cellulitis and abscess)

- Seroma

- Arm morbidity (including lymphedema)

- Phantom breast syndrome

- Injury to the motor nerves.

Seromas often occur in patients after mastectomy or lymph node surgery. Prolonged lymphatic drainage is usually exacerbated by extensive axillary node involvement and obesity.

Arm morbidity can present in different ways. Lymphedema is the most common manifestation, with reported incidences of approximately 15% to 20% when axillary lymph node dissection is performed versus 7% when sentinel lymph node biopsy is done.10 The risk of lymphedema can be reduced by avoiding blood pressure measurements, venipunctures, and intravenous insertions in the arm on the side of the operation, as well as by wearing a compression sleeve on the affected arm during airplane flights.

Phantom breast syndrome is rare but may manifest as pain that may also involve itching, nipple sensation, erotic sensations, or premenstrual-type soreness.

Many surgeons have historically removed the intercostobrachial nerves but are now trying to preserve these nerves, which when removed cause loss of sensation in the upper inner arm. Although rare, nerve injury during an axillary procedure has been reported. It may involve the long thoracic nerve (denervating the serratus anterior muscle and causing a winged scapula) or the thoracodorsal bundle (denervating the latissimus dorsi muscle and causing difficulty with arm/shoulder adduction).

LOCAL CANCER RECURRENCE

Among women undergoing mastectomy for breast cancer, 10% to 15% will have a recurrence of cancer in the chest wall or axillary lymph nodes within 10 years.11 Similarly, among women undergoing breast conservation therapy plus radiation therapy, 10% to 15% will have in-breast cancer recurrence or recurrence in axillary lymph nodes within 10 years, although women who undergo breast conservation therapy without radiation have a much higher recurrence rate.11Considerations for screening the surgically altered breast are discussed in the previous article in this supplement.

ASSESSMENT OF AXILLARY LYMPH NODES FOR METASTASIS

Even when patients have a known histologic diagnosis of breast cancer and have made a firm decision regarding the surgical option for removal of their cancer, the status of their axillary lymph nodes remains a great unanswered question until after the surgical procedure is completed. Lymph node status—ie, determining whether the cancer has spread to the axillary lymph nodes—still serves as the critical determinant for guiding adjuvant treatment, predicting survival, and assessing the risk of recurrence.

Axillary lymph node dissection

The standard approach for evaluating lymph node status has been a complete dissection of the axillary space, or axillary lymph node dissection. As briefly noted above, the axillary lymph nodes are anatomically classified into three levels as defined by their location relative to the pectoralis minor muscle. The extent of a nodal dissection can be defined by the number of nodes removed.

Sentinel node biopsy: A less-invasive alternative

Axillary lymph node dissection has been called into question over the last 15 years due to its invasiveness and the potential morbidity associated with it (including lymphedema and paresthesias). As a result, sentinel lymph node biopsy, a minimally invasive technique for identifying axillary metastasis, was developed to avoid the need for (and risk of complications from) axillary lymph node dissection in patients who have a low probability of axillary metastasis.

Overall, however, it is now accepted that intraoperative lymph node mapping with sentinel lymphadenectomy is an effective and minimally invasive alternative to axillary lymph node dissection for identifying nodes containing metastases.

CONCLUSIONS