User login

A Patient With Recurrent Immune Stromal Keratitis and Adherence Challenges

Herpes simplex keratitis (HSK) is a common yet potentially blinding condition caused by a primary or reactivated herpetic infection of the cornea.1 The Herpetic Eye Disease Study established the standard of care in HSK management.2 Treatments range from oral antivirals and artificial tears to topical antibiotics, amniotic membranes, and corneal transplantation.3 Patients with immune stromal keratitis (ISK) may experience low-grade chronic keratitis for years.4 ISK is classified by a cellular and neovascularization infiltration of the cornea.5 We present a case of a patient with recurrent ISK and review its presentation, diagnosis, and management.

Case Presentation

A 52-year-old man presented to the eye clinic with a watery and itchy right eye with mildly blurred vision. His ocular history was unremarkable. His medical history was notable for hepatitis C, hypertension, alcohol and drug dependence, homelessness, and a COVID-19–induced coma. His medications included trazodone, nifedipine, clonidine HCl, and buprenorphine/naloxone.

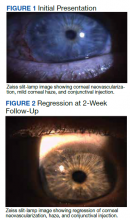

On clinical examination, the patient’s best-corrected visual acuity was 20/40 in the right eye and 20/20 in the left. Corneal sensitivity was absent in the right eye and intact in the left. Anterior segment findings in the right eye included 360-degree superficial corneal neovascularization, deep neovascularization temporally, scattered patches of corneal haze, epithelial irregularity, and 2+ diffuse bulbar conjunctival injection (Figure 1). The anterior segment of the left eye and the posterior segments of both eyes were unremarkable. The differential diagnosis included HSK, syphilis, Cogan syndrome, varicella-zoster virus keratitis, Epstein-Barr virus keratitis, and Lyme disease. With consultation from a corneal specialist, the patient was given the presumptive diagnosis of ISK in the right eye based on unilateral corneal presentation and lack of corneal sensitivity. He was treated with

The patient returned a week later having only used the prednisolone drops for 2 days before discontinuing. Examination showed no change in his corneal appearance from the previous week. The patient was counseled on the importance of adherence to the regimen of topical prednisolone and oral valacyclovir.

The patient followed up 2 weeks later. He reported good adherence to the ISK medication regimen. His symptoms had resolved, and his visual acuity returned to 20/20 in the right eye. Slit-lamp examination showed improvement in injection, and the superficial corneal neovascularization had cleared. A trace ghost vessel was seen temporally at a site of deep neovascularization (Figure 2). He was instructed to continue valacyclovir once daily and prednisolone drops once daily in the right eye and to follow up in 1 month.

At the 1-month follow-up, the patient’s signs and symptoms had reverted to his original presentation. The patient reported poor adherence to the medication regimen, having missed multiple doses of prednisolone drops as well as valacyclovir. The patient was counseled again on the ISK regimen, and the prednisolone drops and 1-g oral valacyclovir were refilled. A follow-up visit was scheduled for 2 weeks. Additional follow-up revealed a resolved corneal appearance and bimonthly follow-ups were scheduled thereafter.

Discussion

HSK is the most common infectious cause of unilateral blindness and vision impairment in the world.2 This case highlights the diagnosis and management of a patient with ISK, a type of HSK characterized by decreased corneal sensitivity and unilateral stromal opacification or neovascularization.6

ISK is caused by the herpes simplex virus (HSV), a double-stranded enveloped DNA virus that occurs worldwide with little variation, replicates in many types of cells, has rapid growth, and is cytolytic, causing necrosis of nearby cells. Transmission is via direct contact and there is a lifelong latency period in the trigeminal ganglia. Both primary and reactivation infections of HSK can affect a broad array of ocular structures, from the lids to the retina. Infectious epithelial keratitis, also known as dendritic keratitis, is the reactivation of the live virus and is the most common presentation of HSK. ISK is responsible for 20% to 48% of recurrent HSV disease and is the leading cause of vision loss. ISK is the result of an immune-mediated inflammatory response due to a retained viral antigen within the stromal tissue.7 Inflammation in the corneal stroma leads to corneal haze and eventually focal or diffuse scarring, reducing the visual potential.7 This presentation may occur days to years after the initial epithelial episode and may persist for years. Although this patient did not present with infectious epithelial keratitis, it is possible he had a previous episode not mentioned as a history was difficult to obtain, and it can be subtle or innocuous, like pink eye.

Symptoms of ISK include unilateral redness, photophobia, tearing, eye pain, and blurred vision, as described by this patient. On examination, initial manifestations of ISK include corneal haze, edema, scarring, and neovascularization.7 Again, this patient presented with edema and neovascularization. These signs may improve with prompt diagnosis and treatment. More frequent reactivated disease leads to a higher propensity of corneal scarring and irregular astigmatism, reducing the visual outcome.

The standard of care established by the Herpetic Eye Disease Study recommends that a patient with presumed ISK should be started on oral antiviral therapy and, in the absence of epithelial disease, topical steroids. Oral antivirals, such as acyclovir and valacyclovir, have good ocular penetration, a good safety profile, a low susceptibility of resistance, and are well tolerated with long-term treatment.2,8 There were no known interactions between any of the patient’s medications and valacyclovir. Oral antivirals should be used in the initial presentation and for maintenance therapy to help reduce the chance of recurrent disease. Initial treatment for ISK is 1-g valacyclovir 3 times daily. When the eye becomes quiet, that dosage can be tapered to 1 g twice daily, to 1 g once daily, and eventually to a maintenance dose of 500 mg daily. Topical steroids block the inflammatory cascade, therefore reducing the corneal inflammation and potential scarring, further reducing the risk of visual impairment.9 Initial treatment is 1 drop 3 times daily, then can be tapered at the same schedule as the oral acyclovir to help simplify adherence for the patient. After 1 drop once daily, steroids may be discontinued while the oral antiviral maintenance dosage continues. Follow-ups should be performed on a monthly to bimonthly basis to evaluate intraocular pressure, ensuring there is no steroid response.

As seen in this patient, adherence with a treatment regimen and awareness of factors, such as a complex psychosocial history that may impact this adherence, are of utmost importance.7

Conclusions

ISK presents unilaterally with decreased or absent corneal sensitivity and nonspecific symptoms. It should be at the top of the list in the differential diagnosis in any patient with unilateral corneal edema, opacification, or neovascularization, and the patient should be started on oral antiviral therapy.

1. Sibley D, Larkin DFP. Update on Herpes simplex keratitis management. Eye (Lond). 2020;34(12):2219-2226. doi:10.1038/s41433-020-01153-x

2. Chodosh J, Ung L. Adoption of innovation in herpes simplex virus keratitis. Cornea. 2020;39(1)(suppl 1):S7-S18. doi:10.1097/ICO.0000000000002425

3. Pérez-Bartolomé F, Botín DM, de Dompablo P, de Arriba P, Arnalich Montiel F, Muñoz Negrete FJ. Post-herpes neurotrophic keratopathy: pathogenesis, clinical signs and current therapies. Arch Soc Esp Oftalmol. 2019;94(4):171-183. doi:10.1016/j.oftal.2019.01.002

4. Holland EJ, Schwartz GS. Classification of herpes simplex virus keratitis. Cornea. 1999;18(2):144-154.

5. Gauthier AS, Noureddine S, Delbosc B. Interstitial keratitis diagnosis and treatment. J Fr Ophtalmol. 2019;42(6):e229-e237. doi:10.1016/j.jfo.2019.04.001

6. Farooq AV, Shukla D. Herpes simplex epithelial and stromal keratitis: an epidemiologic update. Surv Ophthalmol. 2012;5(57):448-462. doi:10.1016/jsurvophthal.2012.01.005

7. Wang L, Wang R, Xu C, Zhou H. Pathogenesis of herpes stromal keratitis: immune inflammatory response mediated by inflammatory regulators. Front Immunol. 2020;11:766. Published 2020 May 13. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2020.00766

8. Tyring SK, Baker D, Snowden W. Valacyclovir for herpes simplex virus infection: long-term safety and sustained efficacy after 20 years’ experience with acyclovir. J Infect Dis. 2002;186(suppl 1):S40-S46. doi:10.1086/342966

9. Dawson CR. The herpetic eye disease study. Arch Ophthalmol. 1990;108(2):191-192. doi:10.1001/archopht.1990.01070040043027

Herpes simplex keratitis (HSK) is a common yet potentially blinding condition caused by a primary or reactivated herpetic infection of the cornea.1 The Herpetic Eye Disease Study established the standard of care in HSK management.2 Treatments range from oral antivirals and artificial tears to topical antibiotics, amniotic membranes, and corneal transplantation.3 Patients with immune stromal keratitis (ISK) may experience low-grade chronic keratitis for years.4 ISK is classified by a cellular and neovascularization infiltration of the cornea.5 We present a case of a patient with recurrent ISK and review its presentation, diagnosis, and management.

Case Presentation

A 52-year-old man presented to the eye clinic with a watery and itchy right eye with mildly blurred vision. His ocular history was unremarkable. His medical history was notable for hepatitis C, hypertension, alcohol and drug dependence, homelessness, and a COVID-19–induced coma. His medications included trazodone, nifedipine, clonidine HCl, and buprenorphine/naloxone.

On clinical examination, the patient’s best-corrected visual acuity was 20/40 in the right eye and 20/20 in the left. Corneal sensitivity was absent in the right eye and intact in the left. Anterior segment findings in the right eye included 360-degree superficial corneal neovascularization, deep neovascularization temporally, scattered patches of corneal haze, epithelial irregularity, and 2+ diffuse bulbar conjunctival injection (Figure 1). The anterior segment of the left eye and the posterior segments of both eyes were unremarkable. The differential diagnosis included HSK, syphilis, Cogan syndrome, varicella-zoster virus keratitis, Epstein-Barr virus keratitis, and Lyme disease. With consultation from a corneal specialist, the patient was given the presumptive diagnosis of ISK in the right eye based on unilateral corneal presentation and lack of corneal sensitivity. He was treated with

The patient returned a week later having only used the prednisolone drops for 2 days before discontinuing. Examination showed no change in his corneal appearance from the previous week. The patient was counseled on the importance of adherence to the regimen of topical prednisolone and oral valacyclovir.

The patient followed up 2 weeks later. He reported good adherence to the ISK medication regimen. His symptoms had resolved, and his visual acuity returned to 20/20 in the right eye. Slit-lamp examination showed improvement in injection, and the superficial corneal neovascularization had cleared. A trace ghost vessel was seen temporally at a site of deep neovascularization (Figure 2). He was instructed to continue valacyclovir once daily and prednisolone drops once daily in the right eye and to follow up in 1 month.

At the 1-month follow-up, the patient’s signs and symptoms had reverted to his original presentation. The patient reported poor adherence to the medication regimen, having missed multiple doses of prednisolone drops as well as valacyclovir. The patient was counseled again on the ISK regimen, and the prednisolone drops and 1-g oral valacyclovir were refilled. A follow-up visit was scheduled for 2 weeks. Additional follow-up revealed a resolved corneal appearance and bimonthly follow-ups were scheduled thereafter.

Discussion

HSK is the most common infectious cause of unilateral blindness and vision impairment in the world.2 This case highlights the diagnosis and management of a patient with ISK, a type of HSK characterized by decreased corneal sensitivity and unilateral stromal opacification or neovascularization.6

ISK is caused by the herpes simplex virus (HSV), a double-stranded enveloped DNA virus that occurs worldwide with little variation, replicates in many types of cells, has rapid growth, and is cytolytic, causing necrosis of nearby cells. Transmission is via direct contact and there is a lifelong latency period in the trigeminal ganglia. Both primary and reactivation infections of HSK can affect a broad array of ocular structures, from the lids to the retina. Infectious epithelial keratitis, also known as dendritic keratitis, is the reactivation of the live virus and is the most common presentation of HSK. ISK is responsible for 20% to 48% of recurrent HSV disease and is the leading cause of vision loss. ISK is the result of an immune-mediated inflammatory response due to a retained viral antigen within the stromal tissue.7 Inflammation in the corneal stroma leads to corneal haze and eventually focal or diffuse scarring, reducing the visual potential.7 This presentation may occur days to years after the initial epithelial episode and may persist for years. Although this patient did not present with infectious epithelial keratitis, it is possible he had a previous episode not mentioned as a history was difficult to obtain, and it can be subtle or innocuous, like pink eye.

Symptoms of ISK include unilateral redness, photophobia, tearing, eye pain, and blurred vision, as described by this patient. On examination, initial manifestations of ISK include corneal haze, edema, scarring, and neovascularization.7 Again, this patient presented with edema and neovascularization. These signs may improve with prompt diagnosis and treatment. More frequent reactivated disease leads to a higher propensity of corneal scarring and irregular astigmatism, reducing the visual outcome.

The standard of care established by the Herpetic Eye Disease Study recommends that a patient with presumed ISK should be started on oral antiviral therapy and, in the absence of epithelial disease, topical steroids. Oral antivirals, such as acyclovir and valacyclovir, have good ocular penetration, a good safety profile, a low susceptibility of resistance, and are well tolerated with long-term treatment.2,8 There were no known interactions between any of the patient’s medications and valacyclovir. Oral antivirals should be used in the initial presentation and for maintenance therapy to help reduce the chance of recurrent disease. Initial treatment for ISK is 1-g valacyclovir 3 times daily. When the eye becomes quiet, that dosage can be tapered to 1 g twice daily, to 1 g once daily, and eventually to a maintenance dose of 500 mg daily. Topical steroids block the inflammatory cascade, therefore reducing the corneal inflammation and potential scarring, further reducing the risk of visual impairment.9 Initial treatment is 1 drop 3 times daily, then can be tapered at the same schedule as the oral acyclovir to help simplify adherence for the patient. After 1 drop once daily, steroids may be discontinued while the oral antiviral maintenance dosage continues. Follow-ups should be performed on a monthly to bimonthly basis to evaluate intraocular pressure, ensuring there is no steroid response.

As seen in this patient, adherence with a treatment regimen and awareness of factors, such as a complex psychosocial history that may impact this adherence, are of utmost importance.7

Conclusions

ISK presents unilaterally with decreased or absent corneal sensitivity and nonspecific symptoms. It should be at the top of the list in the differential diagnosis in any patient with unilateral corneal edema, opacification, or neovascularization, and the patient should be started on oral antiviral therapy.

Herpes simplex keratitis (HSK) is a common yet potentially blinding condition caused by a primary or reactivated herpetic infection of the cornea.1 The Herpetic Eye Disease Study established the standard of care in HSK management.2 Treatments range from oral antivirals and artificial tears to topical antibiotics, amniotic membranes, and corneal transplantation.3 Patients with immune stromal keratitis (ISK) may experience low-grade chronic keratitis for years.4 ISK is classified by a cellular and neovascularization infiltration of the cornea.5 We present a case of a patient with recurrent ISK and review its presentation, diagnosis, and management.

Case Presentation

A 52-year-old man presented to the eye clinic with a watery and itchy right eye with mildly blurred vision. His ocular history was unremarkable. His medical history was notable for hepatitis C, hypertension, alcohol and drug dependence, homelessness, and a COVID-19–induced coma. His medications included trazodone, nifedipine, clonidine HCl, and buprenorphine/naloxone.

On clinical examination, the patient’s best-corrected visual acuity was 20/40 in the right eye and 20/20 in the left. Corneal sensitivity was absent in the right eye and intact in the left. Anterior segment findings in the right eye included 360-degree superficial corneal neovascularization, deep neovascularization temporally, scattered patches of corneal haze, epithelial irregularity, and 2+ diffuse bulbar conjunctival injection (Figure 1). The anterior segment of the left eye and the posterior segments of both eyes were unremarkable. The differential diagnosis included HSK, syphilis, Cogan syndrome, varicella-zoster virus keratitis, Epstein-Barr virus keratitis, and Lyme disease. With consultation from a corneal specialist, the patient was given the presumptive diagnosis of ISK in the right eye based on unilateral corneal presentation and lack of corneal sensitivity. He was treated with

The patient returned a week later having only used the prednisolone drops for 2 days before discontinuing. Examination showed no change in his corneal appearance from the previous week. The patient was counseled on the importance of adherence to the regimen of topical prednisolone and oral valacyclovir.

The patient followed up 2 weeks later. He reported good adherence to the ISK medication regimen. His symptoms had resolved, and his visual acuity returned to 20/20 in the right eye. Slit-lamp examination showed improvement in injection, and the superficial corneal neovascularization had cleared. A trace ghost vessel was seen temporally at a site of deep neovascularization (Figure 2). He was instructed to continue valacyclovir once daily and prednisolone drops once daily in the right eye and to follow up in 1 month.

At the 1-month follow-up, the patient’s signs and symptoms had reverted to his original presentation. The patient reported poor adherence to the medication regimen, having missed multiple doses of prednisolone drops as well as valacyclovir. The patient was counseled again on the ISK regimen, and the prednisolone drops and 1-g oral valacyclovir were refilled. A follow-up visit was scheduled for 2 weeks. Additional follow-up revealed a resolved corneal appearance and bimonthly follow-ups were scheduled thereafter.

Discussion

HSK is the most common infectious cause of unilateral blindness and vision impairment in the world.2 This case highlights the diagnosis and management of a patient with ISK, a type of HSK characterized by decreased corneal sensitivity and unilateral stromal opacification or neovascularization.6

ISK is caused by the herpes simplex virus (HSV), a double-stranded enveloped DNA virus that occurs worldwide with little variation, replicates in many types of cells, has rapid growth, and is cytolytic, causing necrosis of nearby cells. Transmission is via direct contact and there is a lifelong latency period in the trigeminal ganglia. Both primary and reactivation infections of HSK can affect a broad array of ocular structures, from the lids to the retina. Infectious epithelial keratitis, also known as dendritic keratitis, is the reactivation of the live virus and is the most common presentation of HSK. ISK is responsible for 20% to 48% of recurrent HSV disease and is the leading cause of vision loss. ISK is the result of an immune-mediated inflammatory response due to a retained viral antigen within the stromal tissue.7 Inflammation in the corneal stroma leads to corneal haze and eventually focal or diffuse scarring, reducing the visual potential.7 This presentation may occur days to years after the initial epithelial episode and may persist for years. Although this patient did not present with infectious epithelial keratitis, it is possible he had a previous episode not mentioned as a history was difficult to obtain, and it can be subtle or innocuous, like pink eye.

Symptoms of ISK include unilateral redness, photophobia, tearing, eye pain, and blurred vision, as described by this patient. On examination, initial manifestations of ISK include corneal haze, edema, scarring, and neovascularization.7 Again, this patient presented with edema and neovascularization. These signs may improve with prompt diagnosis and treatment. More frequent reactivated disease leads to a higher propensity of corneal scarring and irregular astigmatism, reducing the visual outcome.

The standard of care established by the Herpetic Eye Disease Study recommends that a patient with presumed ISK should be started on oral antiviral therapy and, in the absence of epithelial disease, topical steroids. Oral antivirals, such as acyclovir and valacyclovir, have good ocular penetration, a good safety profile, a low susceptibility of resistance, and are well tolerated with long-term treatment.2,8 There were no known interactions between any of the patient’s medications and valacyclovir. Oral antivirals should be used in the initial presentation and for maintenance therapy to help reduce the chance of recurrent disease. Initial treatment for ISK is 1-g valacyclovir 3 times daily. When the eye becomes quiet, that dosage can be tapered to 1 g twice daily, to 1 g once daily, and eventually to a maintenance dose of 500 mg daily. Topical steroids block the inflammatory cascade, therefore reducing the corneal inflammation and potential scarring, further reducing the risk of visual impairment.9 Initial treatment is 1 drop 3 times daily, then can be tapered at the same schedule as the oral acyclovir to help simplify adherence for the patient. After 1 drop once daily, steroids may be discontinued while the oral antiviral maintenance dosage continues. Follow-ups should be performed on a monthly to bimonthly basis to evaluate intraocular pressure, ensuring there is no steroid response.

As seen in this patient, adherence with a treatment regimen and awareness of factors, such as a complex psychosocial history that may impact this adherence, are of utmost importance.7

Conclusions

ISK presents unilaterally with decreased or absent corneal sensitivity and nonspecific symptoms. It should be at the top of the list in the differential diagnosis in any patient with unilateral corneal edema, opacification, or neovascularization, and the patient should be started on oral antiviral therapy.

1. Sibley D, Larkin DFP. Update on Herpes simplex keratitis management. Eye (Lond). 2020;34(12):2219-2226. doi:10.1038/s41433-020-01153-x

2. Chodosh J, Ung L. Adoption of innovation in herpes simplex virus keratitis. Cornea. 2020;39(1)(suppl 1):S7-S18. doi:10.1097/ICO.0000000000002425

3. Pérez-Bartolomé F, Botín DM, de Dompablo P, de Arriba P, Arnalich Montiel F, Muñoz Negrete FJ. Post-herpes neurotrophic keratopathy: pathogenesis, clinical signs and current therapies. Arch Soc Esp Oftalmol. 2019;94(4):171-183. doi:10.1016/j.oftal.2019.01.002

4. Holland EJ, Schwartz GS. Classification of herpes simplex virus keratitis. Cornea. 1999;18(2):144-154.

5. Gauthier AS, Noureddine S, Delbosc B. Interstitial keratitis diagnosis and treatment. J Fr Ophtalmol. 2019;42(6):e229-e237. doi:10.1016/j.jfo.2019.04.001

6. Farooq AV, Shukla D. Herpes simplex epithelial and stromal keratitis: an epidemiologic update. Surv Ophthalmol. 2012;5(57):448-462. doi:10.1016/jsurvophthal.2012.01.005

7. Wang L, Wang R, Xu C, Zhou H. Pathogenesis of herpes stromal keratitis: immune inflammatory response mediated by inflammatory regulators. Front Immunol. 2020;11:766. Published 2020 May 13. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2020.00766

8. Tyring SK, Baker D, Snowden W. Valacyclovir for herpes simplex virus infection: long-term safety and sustained efficacy after 20 years’ experience with acyclovir. J Infect Dis. 2002;186(suppl 1):S40-S46. doi:10.1086/342966

9. Dawson CR. The herpetic eye disease study. Arch Ophthalmol. 1990;108(2):191-192. doi:10.1001/archopht.1990.01070040043027

1. Sibley D, Larkin DFP. Update on Herpes simplex keratitis management. Eye (Lond). 2020;34(12):2219-2226. doi:10.1038/s41433-020-01153-x

2. Chodosh J, Ung L. Adoption of innovation in herpes simplex virus keratitis. Cornea. 2020;39(1)(suppl 1):S7-S18. doi:10.1097/ICO.0000000000002425

3. Pérez-Bartolomé F, Botín DM, de Dompablo P, de Arriba P, Arnalich Montiel F, Muñoz Negrete FJ. Post-herpes neurotrophic keratopathy: pathogenesis, clinical signs and current therapies. Arch Soc Esp Oftalmol. 2019;94(4):171-183. doi:10.1016/j.oftal.2019.01.002

4. Holland EJ, Schwartz GS. Classification of herpes simplex virus keratitis. Cornea. 1999;18(2):144-154.

5. Gauthier AS, Noureddine S, Delbosc B. Interstitial keratitis diagnosis and treatment. J Fr Ophtalmol. 2019;42(6):e229-e237. doi:10.1016/j.jfo.2019.04.001

6. Farooq AV, Shukla D. Herpes simplex epithelial and stromal keratitis: an epidemiologic update. Surv Ophthalmol. 2012;5(57):448-462. doi:10.1016/jsurvophthal.2012.01.005

7. Wang L, Wang R, Xu C, Zhou H. Pathogenesis of herpes stromal keratitis: immune inflammatory response mediated by inflammatory regulators. Front Immunol. 2020;11:766. Published 2020 May 13. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2020.00766

8. Tyring SK, Baker D, Snowden W. Valacyclovir for herpes simplex virus infection: long-term safety and sustained efficacy after 20 years’ experience with acyclovir. J Infect Dis. 2002;186(suppl 1):S40-S46. doi:10.1086/342966

9. Dawson CR. The herpetic eye disease study. Arch Ophthalmol. 1990;108(2):191-192. doi:10.1001/archopht.1990.01070040043027

Peripheral Exudative Hemorrhagic Chorioretinopathy in Patients With Nonexudative Age-Related Macular Degeneration

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is a common condition that affects the elderly white population. About 6.5% of Americans have been diagnosed with AMD, and 0.8% have received an end-stage AMD diagnosis.1 Exudative AMD is typically more visually debilitating and comprises between 10% and 15% of all AMD cases, with conversion from dry to wet about 10%.1

A thorough examination of the posterior pole is of utmost importance in patients with dry AMD in order to ensure there is no conversion to the exudative form. However, it also is imperative to perform a peripheral evaluation in these patients due to the incidence of peripheral choroidal neovascular membrane (CNVM) and its potential visual significance.

Case Report 1

An 80-year-old white male with type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM) without retinopathy, dry AMD, and epiretinal membranes (ERM) in both eyes presented to the eye clinic for a 6-month follow-up. On examination, he had visual acuity (VA) of 20/25 in both eyes and reported no ocular problems. The intraocular pressures were 17 mm Hg in the right eye and 20 mm Hg in the left eye. Slit-lamp examination of the anterior segment of both eyes was significant for 2+ nuclear sclerotic cataracts.

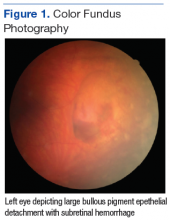

On dilated fundus exam, there were macular drusen and ERM in both eyes; peripherally in the right eye, there was cobblestone degeneration and pigmentary changes. Peripherally in the left eye, there was a large retinal pigment epithelial detachment (PED) with subretinal hemorrhage in the inferior temporal quadrant (Figure 1) along with cobblestone degeneration and pigmentary changes. Peripheral optical coherence tomography (OCT) in the left eye showed a large PED in the location of the hemorrhage (Figure 2).

Case Report 2

An 88-year-old white male presented to the eye clinic reporting blurred vision at distance and dry eyes. The patient’s medical history was remarkable for vascular and heart disease, treated with warfarin. The patient also had insulin controlled DM, with no prior history of retinopathy. His past ocular history included hard drusen in the macula, peripheral drusen, pavingstone degeneration, and a fibrotic scar temporally in the right eye.

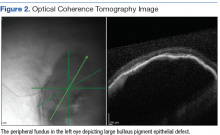

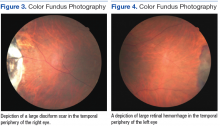

At his annual eye examination, the patient’s vision was correctable to 20/25 in both eyes. His anterior segment slit-lamp exam was remarkable for posterior chamber intraocular lenses, clear and centered in each eye. His posterior pole exam was remarkable for small hard drusen at the macula in both eyes. Peripherally in the right eye, there was a large disciform fibrotic scar temporally (Figure 3) as well as cobblestone degeneration and peripheral drusen. The left eye revealed a large disciform hemorrhage temporally (Figure 4) with cobblestone degeneration and peripheral drusen.

Both patients currently are being closely monitored for any encroachment of the peripheral lesions into the posterior poles.

Discussion

Peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy (PEHCR), also referred to in the literature as eccentric disciform CNVM, peripheral CNVM, and peripheral age-related degeneration, is a rare condition more prevalent in elderly white females.2-4 Mean age ranges from 70 to 82 years, with bilateral involvement ranging from 18% to 37%.2-4 The mid-periphery or periphery is the most common location for these lesions, more specifically, in the inferior temporal quadrant.2,3,5,6

Age-related macular degeneration is not pathognomonic for PEHCR. Mantel and colleagues reported that 68.9% of the patients in their study had AMD.3 Visual acuity ranges from 20/20 to light perception, dependent upon ocular comorbidities.2,3 As reported by Mantel and colleagues, patients with symptomatic PEHCR commonly experience visual loss, floaters, photopsias, metamorphopsia, and scotoma.3

Peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy is a hemorrhagic or exudative process that can occur either as an isolated lesion or as multiple lesions that consist of a PED along with hemorrhage, subretinal fluid and/or fibrotic scarring.2-5 Peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy is not visually significant unless a vitreous hemorrhage is evident or the blood and/or fluid extends to the macular region.2,5

The exact etiology of peripheral CNVM remains unknown; however, ischemia, mechanical forces, and defects in Bruch’s membrane all have been speculated as causative factors.2,3,6 Others have hypothesized that PEHCR is a form of polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy.3,7,8 A rupture in Bruch’s membrane with a vascular complex contributes to the pathophysiology and histology of this condition.3,6

Given the propensity for cardiovascular diseases, such as DM and hypertension, to lead to retinal ischemia, it is important to take a good case history.2,4,6 Additionally, anticoagulants have been shown to exacerbate bleeding.2,5 Due to PEHCR’s location in the periphery, as well as its appearance as an elevated dark mass, it is important to differentiate these lesions from a choroidal melanoma.2,6 Recognition of PEHCR can save the patient from unnecessary treatment with radiation or enucleation.

Peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy is a self-limiting condition that generally requires close observation only. Long-term follow-up studies show resolution, regression, or stability of the peripheral lesions.4,5,8 If a hemorrhage is present, the blood will resolve and leave a disciform scar with pigmentary changes.2-4 In cases where vision is threatened, CNVM has been treated with photocoagulation, cryopexy, and more recently, intravitreal anti-VEGF injections.4,5,9,10 Given that VEGF is more prevalent in the presence of a choroidal neovascular complex, the goal of anti-VEGF therapy is to prevent the growth of and further damage from these abnormal blood vessels.5

Conclusion

The authors have described 2 cases of asymptomatic PEHCR in elderly white males who are both currently being observed closely. Peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy is an uncommon finding; therefore, knowledge of this condition also may be rare. Through this article and these cases, the importance of routine peripheral fundus examination to detect PEHCR should be stressed. It also is important to include PEHCR as a differential diagnosis when evaluating a peripheral dark elevated lesion to distinguish from peripheral melanomas and avoid unnecessary treatments. If identified, these lesions often require close observation only, and a retina referral is warranted if there is macular involvement or a rapidly progressive lesion.5

1. Pron G. Optical coherence tomography monitoring strategies for A-VEGF–treated age-related macular degeneration: an evidence-based analysis. Ont Health Technol Assess Ser. 2014;14(10):1–64.

2. Annesley WH Jr. Peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1980;78:321-364.

3. Mantel I, Uffer S, Zografos L. Peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy: a clinical angiographic, and histologic study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2009;148(6):932-938.

4. Pinarci EY, Kilic I, Bayar SA, Sizmaz S, Akkoyun I, Yilmaz G. Clinical characteristics of peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy and its response to bevacizumab therapy. Eye (Lond). 2013;27(1):111-112.

5. Seibel I, Hager A, Duncker T, et al. Anti-VEGF therapy in symptomatic peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy (PEHCR) involving the macula. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2016;254(4):653-659.

6. Collaer N, James C. Peripheral exudative and hemorrhagic chorio-retinopathy…the peripheral form of age-related macular degeneration? Report on 2 cases. Bull Soc Belge Ophtalmol. 2007;(305):23-26.

7. Goldman DR, Freund KB, McCannel CA, Sarraf D. Peripheral polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy as a cause of peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy: A report of 10 eyes. Retina. 2013;33(1):48-55.

8. Mashayekhi A, Shields CL, Shields JA. Peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy: a variant of polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy? J Ophthalmic Vis Res. 2013;8(3):264-267.

9. Takayama K, Enoki T, Kojima T, Ishikawa S, Takeuchi M. Treatment of peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy by intravitreal injections of ranibizumab. Clin Ophthalmol. 2012;6:865-869.

10. Barkmeier AJ, Kadikoy H, Holz ER, Carvounis PE. Regression of serous macular detachment due to peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy following intravitreal bevacizumab. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2011;21(4):506-508.

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is a common condition that affects the elderly white population. About 6.5% of Americans have been diagnosed with AMD, and 0.8% have received an end-stage AMD diagnosis.1 Exudative AMD is typically more visually debilitating and comprises between 10% and 15% of all AMD cases, with conversion from dry to wet about 10%.1

A thorough examination of the posterior pole is of utmost importance in patients with dry AMD in order to ensure there is no conversion to the exudative form. However, it also is imperative to perform a peripheral evaluation in these patients due to the incidence of peripheral choroidal neovascular membrane (CNVM) and its potential visual significance.

Case Report 1

An 80-year-old white male with type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM) without retinopathy, dry AMD, and epiretinal membranes (ERM) in both eyes presented to the eye clinic for a 6-month follow-up. On examination, he had visual acuity (VA) of 20/25 in both eyes and reported no ocular problems. The intraocular pressures were 17 mm Hg in the right eye and 20 mm Hg in the left eye. Slit-lamp examination of the anterior segment of both eyes was significant for 2+ nuclear sclerotic cataracts.

On dilated fundus exam, there were macular drusen and ERM in both eyes; peripherally in the right eye, there was cobblestone degeneration and pigmentary changes. Peripherally in the left eye, there was a large retinal pigment epithelial detachment (PED) with subretinal hemorrhage in the inferior temporal quadrant (Figure 1) along with cobblestone degeneration and pigmentary changes. Peripheral optical coherence tomography (OCT) in the left eye showed a large PED in the location of the hemorrhage (Figure 2).

Case Report 2

An 88-year-old white male presented to the eye clinic reporting blurred vision at distance and dry eyes. The patient’s medical history was remarkable for vascular and heart disease, treated with warfarin. The patient also had insulin controlled DM, with no prior history of retinopathy. His past ocular history included hard drusen in the macula, peripheral drusen, pavingstone degeneration, and a fibrotic scar temporally in the right eye.

At his annual eye examination, the patient’s vision was correctable to 20/25 in both eyes. His anterior segment slit-lamp exam was remarkable for posterior chamber intraocular lenses, clear and centered in each eye. His posterior pole exam was remarkable for small hard drusen at the macula in both eyes. Peripherally in the right eye, there was a large disciform fibrotic scar temporally (Figure 3) as well as cobblestone degeneration and peripheral drusen. The left eye revealed a large disciform hemorrhage temporally (Figure 4) with cobblestone degeneration and peripheral drusen.

Both patients currently are being closely monitored for any encroachment of the peripheral lesions into the posterior poles.

Discussion

Peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy (PEHCR), also referred to in the literature as eccentric disciform CNVM, peripheral CNVM, and peripheral age-related degeneration, is a rare condition more prevalent in elderly white females.2-4 Mean age ranges from 70 to 82 years, with bilateral involvement ranging from 18% to 37%.2-4 The mid-periphery or periphery is the most common location for these lesions, more specifically, in the inferior temporal quadrant.2,3,5,6

Age-related macular degeneration is not pathognomonic for PEHCR. Mantel and colleagues reported that 68.9% of the patients in their study had AMD.3 Visual acuity ranges from 20/20 to light perception, dependent upon ocular comorbidities.2,3 As reported by Mantel and colleagues, patients with symptomatic PEHCR commonly experience visual loss, floaters, photopsias, metamorphopsia, and scotoma.3

Peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy is a hemorrhagic or exudative process that can occur either as an isolated lesion or as multiple lesions that consist of a PED along with hemorrhage, subretinal fluid and/or fibrotic scarring.2-5 Peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy is not visually significant unless a vitreous hemorrhage is evident or the blood and/or fluid extends to the macular region.2,5

The exact etiology of peripheral CNVM remains unknown; however, ischemia, mechanical forces, and defects in Bruch’s membrane all have been speculated as causative factors.2,3,6 Others have hypothesized that PEHCR is a form of polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy.3,7,8 A rupture in Bruch’s membrane with a vascular complex contributes to the pathophysiology and histology of this condition.3,6

Given the propensity for cardiovascular diseases, such as DM and hypertension, to lead to retinal ischemia, it is important to take a good case history.2,4,6 Additionally, anticoagulants have been shown to exacerbate bleeding.2,5 Due to PEHCR’s location in the periphery, as well as its appearance as an elevated dark mass, it is important to differentiate these lesions from a choroidal melanoma.2,6 Recognition of PEHCR can save the patient from unnecessary treatment with radiation or enucleation.

Peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy is a self-limiting condition that generally requires close observation only. Long-term follow-up studies show resolution, regression, or stability of the peripheral lesions.4,5,8 If a hemorrhage is present, the blood will resolve and leave a disciform scar with pigmentary changes.2-4 In cases where vision is threatened, CNVM has been treated with photocoagulation, cryopexy, and more recently, intravitreal anti-VEGF injections.4,5,9,10 Given that VEGF is more prevalent in the presence of a choroidal neovascular complex, the goal of anti-VEGF therapy is to prevent the growth of and further damage from these abnormal blood vessels.5

Conclusion

The authors have described 2 cases of asymptomatic PEHCR in elderly white males who are both currently being observed closely. Peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy is an uncommon finding; therefore, knowledge of this condition also may be rare. Through this article and these cases, the importance of routine peripheral fundus examination to detect PEHCR should be stressed. It also is important to include PEHCR as a differential diagnosis when evaluating a peripheral dark elevated lesion to distinguish from peripheral melanomas and avoid unnecessary treatments. If identified, these lesions often require close observation only, and a retina referral is warranted if there is macular involvement or a rapidly progressive lesion.5

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is a common condition that affects the elderly white population. About 6.5% of Americans have been diagnosed with AMD, and 0.8% have received an end-stage AMD diagnosis.1 Exudative AMD is typically more visually debilitating and comprises between 10% and 15% of all AMD cases, with conversion from dry to wet about 10%.1

A thorough examination of the posterior pole is of utmost importance in patients with dry AMD in order to ensure there is no conversion to the exudative form. However, it also is imperative to perform a peripheral evaluation in these patients due to the incidence of peripheral choroidal neovascular membrane (CNVM) and its potential visual significance.

Case Report 1

An 80-year-old white male with type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM) without retinopathy, dry AMD, and epiretinal membranes (ERM) in both eyes presented to the eye clinic for a 6-month follow-up. On examination, he had visual acuity (VA) of 20/25 in both eyes and reported no ocular problems. The intraocular pressures were 17 mm Hg in the right eye and 20 mm Hg in the left eye. Slit-lamp examination of the anterior segment of both eyes was significant for 2+ nuclear sclerotic cataracts.

On dilated fundus exam, there were macular drusen and ERM in both eyes; peripherally in the right eye, there was cobblestone degeneration and pigmentary changes. Peripherally in the left eye, there was a large retinal pigment epithelial detachment (PED) with subretinal hemorrhage in the inferior temporal quadrant (Figure 1) along with cobblestone degeneration and pigmentary changes. Peripheral optical coherence tomography (OCT) in the left eye showed a large PED in the location of the hemorrhage (Figure 2).

Case Report 2

An 88-year-old white male presented to the eye clinic reporting blurred vision at distance and dry eyes. The patient’s medical history was remarkable for vascular and heart disease, treated with warfarin. The patient also had insulin controlled DM, with no prior history of retinopathy. His past ocular history included hard drusen in the macula, peripheral drusen, pavingstone degeneration, and a fibrotic scar temporally in the right eye.

At his annual eye examination, the patient’s vision was correctable to 20/25 in both eyes. His anterior segment slit-lamp exam was remarkable for posterior chamber intraocular lenses, clear and centered in each eye. His posterior pole exam was remarkable for small hard drusen at the macula in both eyes. Peripherally in the right eye, there was a large disciform fibrotic scar temporally (Figure 3) as well as cobblestone degeneration and peripheral drusen. The left eye revealed a large disciform hemorrhage temporally (Figure 4) with cobblestone degeneration and peripheral drusen.

Both patients currently are being closely monitored for any encroachment of the peripheral lesions into the posterior poles.

Discussion

Peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy (PEHCR), also referred to in the literature as eccentric disciform CNVM, peripheral CNVM, and peripheral age-related degeneration, is a rare condition more prevalent in elderly white females.2-4 Mean age ranges from 70 to 82 years, with bilateral involvement ranging from 18% to 37%.2-4 The mid-periphery or periphery is the most common location for these lesions, more specifically, in the inferior temporal quadrant.2,3,5,6

Age-related macular degeneration is not pathognomonic for PEHCR. Mantel and colleagues reported that 68.9% of the patients in their study had AMD.3 Visual acuity ranges from 20/20 to light perception, dependent upon ocular comorbidities.2,3 As reported by Mantel and colleagues, patients with symptomatic PEHCR commonly experience visual loss, floaters, photopsias, metamorphopsia, and scotoma.3

Peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy is a hemorrhagic or exudative process that can occur either as an isolated lesion or as multiple lesions that consist of a PED along with hemorrhage, subretinal fluid and/or fibrotic scarring.2-5 Peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy is not visually significant unless a vitreous hemorrhage is evident or the blood and/or fluid extends to the macular region.2,5

The exact etiology of peripheral CNVM remains unknown; however, ischemia, mechanical forces, and defects in Bruch’s membrane all have been speculated as causative factors.2,3,6 Others have hypothesized that PEHCR is a form of polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy.3,7,8 A rupture in Bruch’s membrane with a vascular complex contributes to the pathophysiology and histology of this condition.3,6

Given the propensity for cardiovascular diseases, such as DM and hypertension, to lead to retinal ischemia, it is important to take a good case history.2,4,6 Additionally, anticoagulants have been shown to exacerbate bleeding.2,5 Due to PEHCR’s location in the periphery, as well as its appearance as an elevated dark mass, it is important to differentiate these lesions from a choroidal melanoma.2,6 Recognition of PEHCR can save the patient from unnecessary treatment with radiation or enucleation.

Peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy is a self-limiting condition that generally requires close observation only. Long-term follow-up studies show resolution, regression, or stability of the peripheral lesions.4,5,8 If a hemorrhage is present, the blood will resolve and leave a disciform scar with pigmentary changes.2-4 In cases where vision is threatened, CNVM has been treated with photocoagulation, cryopexy, and more recently, intravitreal anti-VEGF injections.4,5,9,10 Given that VEGF is more prevalent in the presence of a choroidal neovascular complex, the goal of anti-VEGF therapy is to prevent the growth of and further damage from these abnormal blood vessels.5

Conclusion

The authors have described 2 cases of asymptomatic PEHCR in elderly white males who are both currently being observed closely. Peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy is an uncommon finding; therefore, knowledge of this condition also may be rare. Through this article and these cases, the importance of routine peripheral fundus examination to detect PEHCR should be stressed. It also is important to include PEHCR as a differential diagnosis when evaluating a peripheral dark elevated lesion to distinguish from peripheral melanomas and avoid unnecessary treatments. If identified, these lesions often require close observation only, and a retina referral is warranted if there is macular involvement or a rapidly progressive lesion.5

1. Pron G. Optical coherence tomography monitoring strategies for A-VEGF–treated age-related macular degeneration: an evidence-based analysis. Ont Health Technol Assess Ser. 2014;14(10):1–64.

2. Annesley WH Jr. Peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1980;78:321-364.

3. Mantel I, Uffer S, Zografos L. Peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy: a clinical angiographic, and histologic study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2009;148(6):932-938.

4. Pinarci EY, Kilic I, Bayar SA, Sizmaz S, Akkoyun I, Yilmaz G. Clinical characteristics of peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy and its response to bevacizumab therapy. Eye (Lond). 2013;27(1):111-112.

5. Seibel I, Hager A, Duncker T, et al. Anti-VEGF therapy in symptomatic peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy (PEHCR) involving the macula. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2016;254(4):653-659.

6. Collaer N, James C. Peripheral exudative and hemorrhagic chorio-retinopathy…the peripheral form of age-related macular degeneration? Report on 2 cases. Bull Soc Belge Ophtalmol. 2007;(305):23-26.

7. Goldman DR, Freund KB, McCannel CA, Sarraf D. Peripheral polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy as a cause of peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy: A report of 10 eyes. Retina. 2013;33(1):48-55.

8. Mashayekhi A, Shields CL, Shields JA. Peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy: a variant of polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy? J Ophthalmic Vis Res. 2013;8(3):264-267.

9. Takayama K, Enoki T, Kojima T, Ishikawa S, Takeuchi M. Treatment of peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy by intravitreal injections of ranibizumab. Clin Ophthalmol. 2012;6:865-869.

10. Barkmeier AJ, Kadikoy H, Holz ER, Carvounis PE. Regression of serous macular detachment due to peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy following intravitreal bevacizumab. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2011;21(4):506-508.

1. Pron G. Optical coherence tomography monitoring strategies for A-VEGF–treated age-related macular degeneration: an evidence-based analysis. Ont Health Technol Assess Ser. 2014;14(10):1–64.

2. Annesley WH Jr. Peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1980;78:321-364.

3. Mantel I, Uffer S, Zografos L. Peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy: a clinical angiographic, and histologic study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2009;148(6):932-938.

4. Pinarci EY, Kilic I, Bayar SA, Sizmaz S, Akkoyun I, Yilmaz G. Clinical characteristics of peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy and its response to bevacizumab therapy. Eye (Lond). 2013;27(1):111-112.

5. Seibel I, Hager A, Duncker T, et al. Anti-VEGF therapy in symptomatic peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy (PEHCR) involving the macula. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2016;254(4):653-659.

6. Collaer N, James C. Peripheral exudative and hemorrhagic chorio-retinopathy…the peripheral form of age-related macular degeneration? Report on 2 cases. Bull Soc Belge Ophtalmol. 2007;(305):23-26.

7. Goldman DR, Freund KB, McCannel CA, Sarraf D. Peripheral polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy as a cause of peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy: A report of 10 eyes. Retina. 2013;33(1):48-55.

8. Mashayekhi A, Shields CL, Shields JA. Peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy: a variant of polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy? J Ophthalmic Vis Res. 2013;8(3):264-267.

9. Takayama K, Enoki T, Kojima T, Ishikawa S, Takeuchi M. Treatment of peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy by intravitreal injections of ranibizumab. Clin Ophthalmol. 2012;6:865-869.

10. Barkmeier AJ, Kadikoy H, Holz ER, Carvounis PE. Regression of serous macular detachment due to peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy following intravitreal bevacizumab. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2011;21(4):506-508.