User login

Painful Psoriasiform Plaques

The Diagnosis: Acquired Acrodermatitis Enteropathica

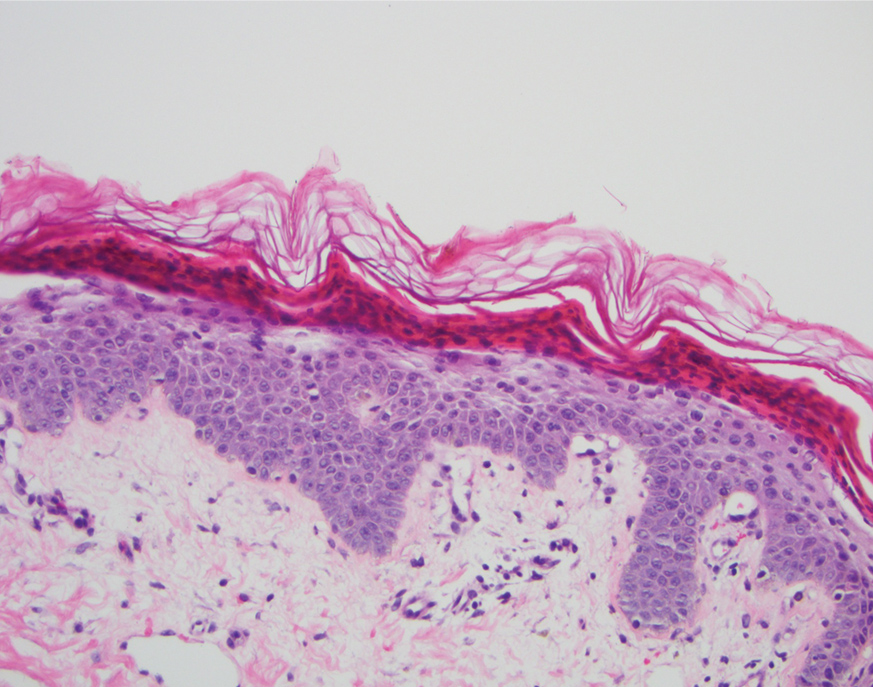

A punch biopsy of an elevated scaly border of the rash on the thigh revealed parakeratosis, absence of the granular layer, and epidermal pallor with psoriasiform and spongiotic dermatitis (Figure). Serum zinc levels were 60.1 μg/dL (reference range, 75.0–120.0 μg/dL), suggestive of a nutritional deficiency dermatitis. Laboratory and histopathologic findings were most consistent with a diagnosis of acquired acrodermatitis enteropathica (AE).

Acrodermatitis enteropathica has been associated with Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and alcohol use disorder working synergistically to cause malabsorption and malnutrition, respectively.1 Zinc functions in the structural integrity, wound healing, and anti-inflammatory properties of the skin. There is a 17.3% risk for hypozincemia worldwide; in developed nations there is an estimated 3% to 10% occurrence rate.2 Acrodermatitis enteropathica can be classified as either acquired or hereditary. Both classically present as a triad of acral dermatitis, diarrhea, and alopecia, though the complete triad is seen in 20% of cases.3,4

Hereditary AE is an autosomal-recessive disorder presenting in infancy that results in the loss of a zinc transporter. In contrast, acquired AE occurs later in life and usually is seen in patients who have decreased intake, malabsorption, or excessive loss of zinc.4 Acrodermatitis enteropathica is observed in individuals with conditions such as anorexia nervosa, pancreatic insufficiency, celiac disease, Crohn disease, or gastric bypass surgery (as in our case) and alcohol recidivism. In early disease, AE often presents with angular cheilitis and paronychia, but if left untreated, it can progress to mental status changes, hypogonadism, and depression.4 Acrodermatitis enteropathica presents as erythematous, erosive, scaly plaques or a papulosquamous psoriasiform rash with well-demarcated borders typically involving the orificial, acral, and intertriginous areas of the body.1,4

Acrodermatitis enteropathica belongs to a family of deficiency dermatoses that includes pellagra, necrolytic acral erythema (NAE), and necrolytic migratory erythema (NME).5 It is important to distinguish AE from NAE, as they can present similarly with well-defined and tender psoriasiform lesions peripherally. Histologically, NAE mimics AE with psoriasiform hyperplasia with parakeratosis.6 Necrolytic acral erythema characteristically is associated with active hepatitis C infection, which was absent in our patient.7

Similar to AE, NME affects the perineal and intertriginous surfaces.8 However, necrolytic migratory erythema has cutaneous manifestations in up to 70% of patients with glucagonoma syndrome, which classically presents as a triad of NME, weight loss, and diabetes mellitus.5 Laboratory studies show marked hyperglucagonemia, and imaging reveals enteropancreatic neoplasia. Necrolytic migratory erythema will rapidly resolve once the glucagonoma has been surgically removed.5 Bazex syndrome, or acrokeratosis paraneoplastica, is a paraneoplastic skin disease that is linked to underlying aerodigestive tract malignancies.

Bazex syndrome clinically is characterized by hyperkeratotic and psoriasiform lesions favoring the ears, nails, and nose.9

Psoriasis vulgaris is a common chronic inflammatory skin condition that usually presents as well-demarcated plaques with silvery scale and observed pinpoint bleeding when layers of scale are removed (Auspitz sign). Lesions typically are found on the extensor surfaces of the body in addition to the neck, feet, hands, and trunk. Treatment of psoriasis vulgaris ranges from topical steroids for mild cases to systemic biologics for moderate to severe circumstances.10 In our patient, topical triamcinolone offered little relief.

Acrodermatitis enteropathica displays clinical and histologic characteristics analogous to many deficiency dermatoses and may represent a spectrum of disease. Because the clinicopathologic findings are nonspecific, it is critical to obtain a comprehensive history and maintain a high index of suspicion in patients with risk factors for malnutrition. The treatment for AE is supplemental oral zinc usually initiated at 0.5 to 1 mg/kg daily in children and 30 to 45 mg daily in adults.3 Our patient initially was prescribed oral zinc supplementation; however, at 1-month follow-up, the rash had not improved. Failure of zinc monotherapy supports a multifactorial nutritional deficiency, which necessitated comprehensive nutritional appraisal and supplementation in our patient. Due to the steatorrhea, fecal pancreatic elastase levels were evaluated and were less than 15 μg/g (reference range, ≥201 μg/g), confirming pancreatic exocrine insufficiency, a known complication of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass.11 Pancrelipase 500 U/kg per meal was added in addition to zinc oxide 40% paste to apply to the rash twice daily, with more frequent applications to the anogenital regions after bowel movements. The patient had substantial clinical improvement after 2 months.

- Shahsavari D, Ahmed Z, Karikkineth A, et al. Zinc-deficiency acrodermatitis in a patient with chronic alcoholism and gastric bypass: a case report. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect. 2014. doi:10.3402/jchimp.v4.24707

- Kelly S, Stelzer JW, Esplin N, et al. Acquired acrodermatitis enteropathica: a case study. Cureus. 2017;9:E1667.

- Guliani A, Bishnoi A. Acquired acrodermatitis enteropathica. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:1305.

- Baruch D, Naga L, Driscoll M, et al. Acrodermatitis enteropathica from zinc-deficient total parenteral nutrition. Cutis. 2018;101:450-453.

- van Beek AP, de Haas ER, van Vloten WA, et al. The glucagonoma syndrome and necrolytic migratory erythema: a clinical review. Eur J Endocrinol. 2004;151:531-537.

- Botelho LF, Enokihara MM, Enokihara MY. Necrolytic acral erythema: a rare skin disease associated with hepatitis C virus infection. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;91:649-651.

- Abdallah MA, Ghozzi MY, Monib HA, et al. Necrolytic acral erythema: a cutaneous sign of hepatitis C virus infection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:247-251.

- Tolliver S, Graham J, Kaffenberger BH. A review of cutaneous manifestations within glucagonoma syndrome: necrolytic migratory erythema. Int J Dermatol. 2018;57:642-645.

- Poligone B, Christensen SR, Lazova R, et al. Bazex syndrome (acrokeratosis paraneoplastica). Lancet. 2007;369:530. 10. Kupetsky EA, Keller M. Psoriasis vulgaris: an evidencebased guide for primary care. J Am Board Fam Med. 2013; 26:787-801.

- Borbély Y, Plebani A, Kröll D, et al. Exocrine pancreatic insufficiency after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2016;12:790-794.

The Diagnosis: Acquired Acrodermatitis Enteropathica

A punch biopsy of an elevated scaly border of the rash on the thigh revealed parakeratosis, absence of the granular layer, and epidermal pallor with psoriasiform and spongiotic dermatitis (Figure). Serum zinc levels were 60.1 μg/dL (reference range, 75.0–120.0 μg/dL), suggestive of a nutritional deficiency dermatitis. Laboratory and histopathologic findings were most consistent with a diagnosis of acquired acrodermatitis enteropathica (AE).

Acrodermatitis enteropathica has been associated with Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and alcohol use disorder working synergistically to cause malabsorption and malnutrition, respectively.1 Zinc functions in the structural integrity, wound healing, and anti-inflammatory properties of the skin. There is a 17.3% risk for hypozincemia worldwide; in developed nations there is an estimated 3% to 10% occurrence rate.2 Acrodermatitis enteropathica can be classified as either acquired or hereditary. Both classically present as a triad of acral dermatitis, diarrhea, and alopecia, though the complete triad is seen in 20% of cases.3,4

Hereditary AE is an autosomal-recessive disorder presenting in infancy that results in the loss of a zinc transporter. In contrast, acquired AE occurs later in life and usually is seen in patients who have decreased intake, malabsorption, or excessive loss of zinc.4 Acrodermatitis enteropathica is observed in individuals with conditions such as anorexia nervosa, pancreatic insufficiency, celiac disease, Crohn disease, or gastric bypass surgery (as in our case) and alcohol recidivism. In early disease, AE often presents with angular cheilitis and paronychia, but if left untreated, it can progress to mental status changes, hypogonadism, and depression.4 Acrodermatitis enteropathica presents as erythematous, erosive, scaly plaques or a papulosquamous psoriasiform rash with well-demarcated borders typically involving the orificial, acral, and intertriginous areas of the body.1,4

Acrodermatitis enteropathica belongs to a family of deficiency dermatoses that includes pellagra, necrolytic acral erythema (NAE), and necrolytic migratory erythema (NME).5 It is important to distinguish AE from NAE, as they can present similarly with well-defined and tender psoriasiform lesions peripherally. Histologically, NAE mimics AE with psoriasiform hyperplasia with parakeratosis.6 Necrolytic acral erythema characteristically is associated with active hepatitis C infection, which was absent in our patient.7

Similar to AE, NME affects the perineal and intertriginous surfaces.8 However, necrolytic migratory erythema has cutaneous manifestations in up to 70% of patients with glucagonoma syndrome, which classically presents as a triad of NME, weight loss, and diabetes mellitus.5 Laboratory studies show marked hyperglucagonemia, and imaging reveals enteropancreatic neoplasia. Necrolytic migratory erythema will rapidly resolve once the glucagonoma has been surgically removed.5 Bazex syndrome, or acrokeratosis paraneoplastica, is a paraneoplastic skin disease that is linked to underlying aerodigestive tract malignancies.

Bazex syndrome clinically is characterized by hyperkeratotic and psoriasiform lesions favoring the ears, nails, and nose.9

Psoriasis vulgaris is a common chronic inflammatory skin condition that usually presents as well-demarcated plaques with silvery scale and observed pinpoint bleeding when layers of scale are removed (Auspitz sign). Lesions typically are found on the extensor surfaces of the body in addition to the neck, feet, hands, and trunk. Treatment of psoriasis vulgaris ranges from topical steroids for mild cases to systemic biologics for moderate to severe circumstances.10 In our patient, topical triamcinolone offered little relief.

Acrodermatitis enteropathica displays clinical and histologic characteristics analogous to many deficiency dermatoses and may represent a spectrum of disease. Because the clinicopathologic findings are nonspecific, it is critical to obtain a comprehensive history and maintain a high index of suspicion in patients with risk factors for malnutrition. The treatment for AE is supplemental oral zinc usually initiated at 0.5 to 1 mg/kg daily in children and 30 to 45 mg daily in adults.3 Our patient initially was prescribed oral zinc supplementation; however, at 1-month follow-up, the rash had not improved. Failure of zinc monotherapy supports a multifactorial nutritional deficiency, which necessitated comprehensive nutritional appraisal and supplementation in our patient. Due to the steatorrhea, fecal pancreatic elastase levels were evaluated and were less than 15 μg/g (reference range, ≥201 μg/g), confirming pancreatic exocrine insufficiency, a known complication of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass.11 Pancrelipase 500 U/kg per meal was added in addition to zinc oxide 40% paste to apply to the rash twice daily, with more frequent applications to the anogenital regions after bowel movements. The patient had substantial clinical improvement after 2 months.

The Diagnosis: Acquired Acrodermatitis Enteropathica

A punch biopsy of an elevated scaly border of the rash on the thigh revealed parakeratosis, absence of the granular layer, and epidermal pallor with psoriasiform and spongiotic dermatitis (Figure). Serum zinc levels were 60.1 μg/dL (reference range, 75.0–120.0 μg/dL), suggestive of a nutritional deficiency dermatitis. Laboratory and histopathologic findings were most consistent with a diagnosis of acquired acrodermatitis enteropathica (AE).

Acrodermatitis enteropathica has been associated with Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and alcohol use disorder working synergistically to cause malabsorption and malnutrition, respectively.1 Zinc functions in the structural integrity, wound healing, and anti-inflammatory properties of the skin. There is a 17.3% risk for hypozincemia worldwide; in developed nations there is an estimated 3% to 10% occurrence rate.2 Acrodermatitis enteropathica can be classified as either acquired or hereditary. Both classically present as a triad of acral dermatitis, diarrhea, and alopecia, though the complete triad is seen in 20% of cases.3,4

Hereditary AE is an autosomal-recessive disorder presenting in infancy that results in the loss of a zinc transporter. In contrast, acquired AE occurs later in life and usually is seen in patients who have decreased intake, malabsorption, or excessive loss of zinc.4 Acrodermatitis enteropathica is observed in individuals with conditions such as anorexia nervosa, pancreatic insufficiency, celiac disease, Crohn disease, or gastric bypass surgery (as in our case) and alcohol recidivism. In early disease, AE often presents with angular cheilitis and paronychia, but if left untreated, it can progress to mental status changes, hypogonadism, and depression.4 Acrodermatitis enteropathica presents as erythematous, erosive, scaly plaques or a papulosquamous psoriasiform rash with well-demarcated borders typically involving the orificial, acral, and intertriginous areas of the body.1,4

Acrodermatitis enteropathica belongs to a family of deficiency dermatoses that includes pellagra, necrolytic acral erythema (NAE), and necrolytic migratory erythema (NME).5 It is important to distinguish AE from NAE, as they can present similarly with well-defined and tender psoriasiform lesions peripherally. Histologically, NAE mimics AE with psoriasiform hyperplasia with parakeratosis.6 Necrolytic acral erythema characteristically is associated with active hepatitis C infection, which was absent in our patient.7

Similar to AE, NME affects the perineal and intertriginous surfaces.8 However, necrolytic migratory erythema has cutaneous manifestations in up to 70% of patients with glucagonoma syndrome, which classically presents as a triad of NME, weight loss, and diabetes mellitus.5 Laboratory studies show marked hyperglucagonemia, and imaging reveals enteropancreatic neoplasia. Necrolytic migratory erythema will rapidly resolve once the glucagonoma has been surgically removed.5 Bazex syndrome, or acrokeratosis paraneoplastica, is a paraneoplastic skin disease that is linked to underlying aerodigestive tract malignancies.

Bazex syndrome clinically is characterized by hyperkeratotic and psoriasiform lesions favoring the ears, nails, and nose.9

Psoriasis vulgaris is a common chronic inflammatory skin condition that usually presents as well-demarcated plaques with silvery scale and observed pinpoint bleeding when layers of scale are removed (Auspitz sign). Lesions typically are found on the extensor surfaces of the body in addition to the neck, feet, hands, and trunk. Treatment of psoriasis vulgaris ranges from topical steroids for mild cases to systemic biologics for moderate to severe circumstances.10 In our patient, topical triamcinolone offered little relief.

Acrodermatitis enteropathica displays clinical and histologic characteristics analogous to many deficiency dermatoses and may represent a spectrum of disease. Because the clinicopathologic findings are nonspecific, it is critical to obtain a comprehensive history and maintain a high index of suspicion in patients with risk factors for malnutrition. The treatment for AE is supplemental oral zinc usually initiated at 0.5 to 1 mg/kg daily in children and 30 to 45 mg daily in adults.3 Our patient initially was prescribed oral zinc supplementation; however, at 1-month follow-up, the rash had not improved. Failure of zinc monotherapy supports a multifactorial nutritional deficiency, which necessitated comprehensive nutritional appraisal and supplementation in our patient. Due to the steatorrhea, fecal pancreatic elastase levels were evaluated and were less than 15 μg/g (reference range, ≥201 μg/g), confirming pancreatic exocrine insufficiency, a known complication of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass.11 Pancrelipase 500 U/kg per meal was added in addition to zinc oxide 40% paste to apply to the rash twice daily, with more frequent applications to the anogenital regions after bowel movements. The patient had substantial clinical improvement after 2 months.

- Shahsavari D, Ahmed Z, Karikkineth A, et al. Zinc-deficiency acrodermatitis in a patient with chronic alcoholism and gastric bypass: a case report. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect. 2014. doi:10.3402/jchimp.v4.24707

- Kelly S, Stelzer JW, Esplin N, et al. Acquired acrodermatitis enteropathica: a case study. Cureus. 2017;9:E1667.

- Guliani A, Bishnoi A. Acquired acrodermatitis enteropathica. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:1305.

- Baruch D, Naga L, Driscoll M, et al. Acrodermatitis enteropathica from zinc-deficient total parenteral nutrition. Cutis. 2018;101:450-453.

- van Beek AP, de Haas ER, van Vloten WA, et al. The glucagonoma syndrome and necrolytic migratory erythema: a clinical review. Eur J Endocrinol. 2004;151:531-537.

- Botelho LF, Enokihara MM, Enokihara MY. Necrolytic acral erythema: a rare skin disease associated with hepatitis C virus infection. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;91:649-651.

- Abdallah MA, Ghozzi MY, Monib HA, et al. Necrolytic acral erythema: a cutaneous sign of hepatitis C virus infection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:247-251.

- Tolliver S, Graham J, Kaffenberger BH. A review of cutaneous manifestations within glucagonoma syndrome: necrolytic migratory erythema. Int J Dermatol. 2018;57:642-645.

- Poligone B, Christensen SR, Lazova R, et al. Bazex syndrome (acrokeratosis paraneoplastica). Lancet. 2007;369:530. 10. Kupetsky EA, Keller M. Psoriasis vulgaris: an evidencebased guide for primary care. J Am Board Fam Med. 2013; 26:787-801.

- Borbély Y, Plebani A, Kröll D, et al. Exocrine pancreatic insufficiency after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2016;12:790-794.

- Shahsavari D, Ahmed Z, Karikkineth A, et al. Zinc-deficiency acrodermatitis in a patient with chronic alcoholism and gastric bypass: a case report. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect. 2014. doi:10.3402/jchimp.v4.24707

- Kelly S, Stelzer JW, Esplin N, et al. Acquired acrodermatitis enteropathica: a case study. Cureus. 2017;9:E1667.

- Guliani A, Bishnoi A. Acquired acrodermatitis enteropathica. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:1305.

- Baruch D, Naga L, Driscoll M, et al. Acrodermatitis enteropathica from zinc-deficient total parenteral nutrition. Cutis. 2018;101:450-453.

- van Beek AP, de Haas ER, van Vloten WA, et al. The glucagonoma syndrome and necrolytic migratory erythema: a clinical review. Eur J Endocrinol. 2004;151:531-537.

- Botelho LF, Enokihara MM, Enokihara MY. Necrolytic acral erythema: a rare skin disease associated with hepatitis C virus infection. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;91:649-651.

- Abdallah MA, Ghozzi MY, Monib HA, et al. Necrolytic acral erythema: a cutaneous sign of hepatitis C virus infection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:247-251.

- Tolliver S, Graham J, Kaffenberger BH. A review of cutaneous manifestations within glucagonoma syndrome: necrolytic migratory erythema. Int J Dermatol. 2018;57:642-645.

- Poligone B, Christensen SR, Lazova R, et al. Bazex syndrome (acrokeratosis paraneoplastica). Lancet. 2007;369:530. 10. Kupetsky EA, Keller M. Psoriasis vulgaris: an evidencebased guide for primary care. J Am Board Fam Med. 2013; 26:787-801.

- Borbély Y, Plebani A, Kröll D, et al. Exocrine pancreatic insufficiency after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2016;12:790-794.

A 45-year-old woman presented to the emergency department with a painful skin eruption and malaise of 5 weeks’ duration. She had an orthotopic liver transplant 5 years prior for end-stage liver disease due to mixed nonalcoholic and alcoholic steatohepatitis and was on mycophenolate mofetil and tacrolimus for graft rejection prophylaxis. Her medical history also included Roux-en-Y gastric bypass 15 years prior, alcohol use disorder, hypothyroidism, and depression.

The exanthem began on the legs as pruritic, red, raised, exudative lesions that gradually crusted. Over the 2 weeks prior to the current presentation, the rash became tender as it spread to the feet, thighs, perianal skin, buttocks, and elbows. Triamcinolone ointment prescribed for a presumed nummular dermatitis effected marginal benefit. A review of systems was notable for a 15-pound weight loss over several weeks; lowgrade fever of 3 days’ duration; epigastric abdominal pain; and long-standing, frequent defecation of oily, foul-smelling feces.

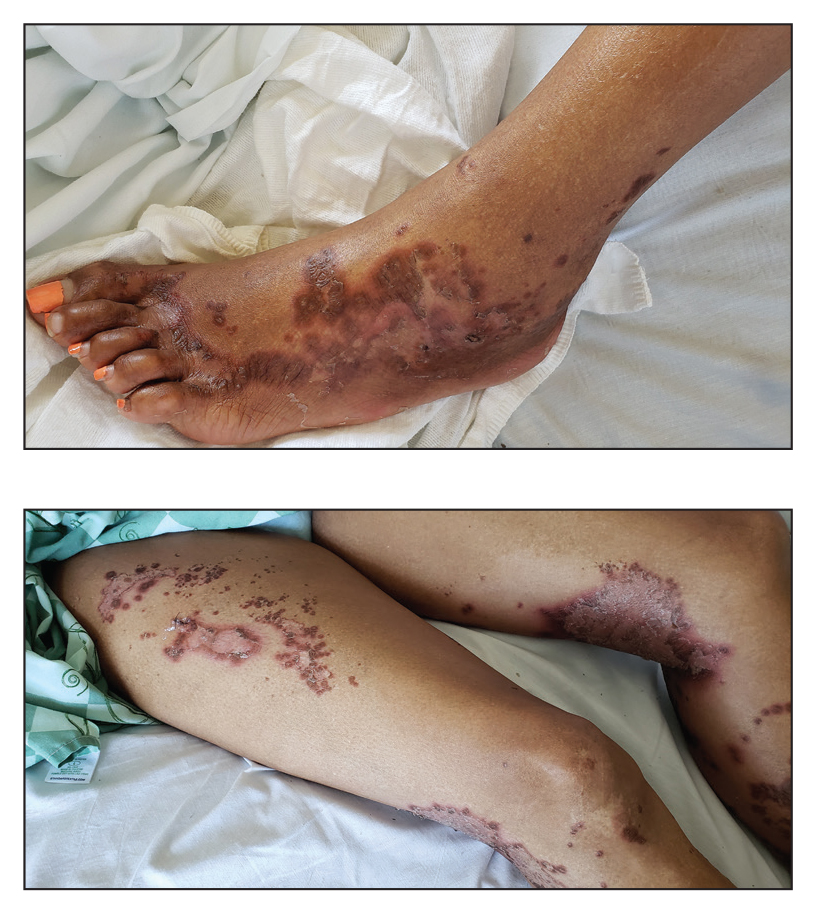

Physical examination revealed a combination of flat-topped, violaceous papules and serpiginous, polycyclic, annular plaques coalescing to form larger psoriasiform plaques with hyperkeratotic rims and dusky borders on the dorsal aspect of the feet (top), lateral ankles, legs (bottom), lateral thighs, buttocks, perianal skin, and elbows. Bilateral angular cheilitis, a smooth and fissured tongue, and pitting of all fingernails were noted.

Acute Hemorrhagic Edema of Infancy: Guide to Prevent Misdiagnosis

Acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy (AHEI) is an uncommon leukocytoclastic vasculitis affecting children aged 6 to 24 months; Henoch-Schönlein purpura (HSP) is the most common misdiagnosis. The 2 entities should be differentiated, as HSP may have renal and gastrointestinal (GI) comorbidities that need serial follow-up, whereas AHEI follows a benign course without systemic sequelae. Patient history and physical examination are the most important factors in differentiating the 2 diseases; histopathologic and direct immunofluorescence (DIF) analyses may lend further diagnostic confidence.

We report the case of a 10-month-old previously healthy boy who presented with acute rash, edema, and low-grade fever in the setting of recent diarrhea. We differentiate between AHEI and HSP to help prevent misdiagnosis by health care providers.

Case Report

A 10-month-old previously healthy boy presented to the emergency department (ED) for evaluation of a rash and swelling of 4 days’ duration. He had nonbloody diarrhea 1 week prior; soon after, he developed bilateral lower leg edema and rash. On evaluation in a different ED, he had a low-grade fever (rectal temperature, 38.0°C) but normal blood work, including complete blood cell count, basic metabolic panel, and coagulation studies. The patient was discharged to outpatient follow-up with his pediatrician who reported normal urinalysis.

Due to progression of the rash, the patient presented to our ED 3 days after his initial ED assessment. Dermatology was consulted. At the time of presentation, he was afebrile but with GI upset and fussiness. His parents denied additional symptoms or blood in urine or stool. Physical examination revealed a nontoxic-appearing infant with scattered palpable, annular, purpuric papules coalescing into plaques on both legs and feet (Figure 1), with sparse petechiae noted on the lower abdomen. The cheeks had scattered purpuric papules and plaques bilaterally, a few with a small central crust (Figure 2), and the right superior helix had a faint purpuric macule. The hands had a few pink edematous coalescing papules.

Histopathologic analyses with hematoxylin and eosin staining (Figure 3) and DIF (Figure 4) were performed from within a representative purpuric plaque on the right hip. Direct immunofluorescence was performed to evaluate for an IgA vasculitis versus an alternative type of vasculitis. The hematoxylin and eosin–stained specimen demonstrated a dermal perivascular infiltrate involving superficial and deep vessels with neutrophils, karyorrhexis, and erythrocyte extravasation. The endothelium was intact, with a mild suggestion of fibrinoid change of the blood vessel walls. Direct immunofluorescence revealed granular deposition of IgA, C3, and fibrinogen in multiple dermal blood vessels. Combined, the specimens were interpreted as evolving IgA-associated leukocytoclastic vasculitis.

The case was reviewed with our 2 department pediatric dermatologists; a diagnosis of AHEI was made based on the clinical and supportive histopathological presentations. The patient’s parents chose active treatment with a 2-week taper of oral prednisone because of the patient’s discomfort with edema. No GI or adverse renal sequelae, including findings on urinalysis, were reported at 1-month hospital follow-up with dermatology and pediatrics.

Comment

Incidence and Clinical Characteristics

Acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy is an uncommon leukocytoclastic vasculitis first described in the United States by Snow1 in 1913. Other names for the disorder include acute hemorrhagic edema of young children, cockade purpura and edema, Finkelstein disease, and Seidlmayer disease.2 Boys are affected more often than girls, with most children presenting at 6 to 24 months of age. Most affected children experience a prodrome of simple respiratory tract illness (most common), diarrhea (as in our case), or urinary tract infection.2 The exact pathophysiology behind AHEI is unknown, but it is thought to be an immune complex–mediated disease evidenced by the fact that infection, use of medication, or immunization precedes most cases.3,4

Diagnosis

Acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy is diagnosed clinically, with or without the support of skin biopsy. It should be differentiated from HSP because of renal and GI sequelae that HSP portends compared to the benign course of AHEI.2 Notably, some health care providers consider AHEI a benign variant of HSP.2,3

Characteristically, AHEI patients are nontoxic-appearing infants with a low-grade fever who develop relatively large (1–5 cm) targetoid purpuric lesions and indurated nonpitting edema of the extremities.2,5 Purpura in AHEI frequently occurs on the face, ears, and upper and lower extremities, whereas purpura in HSP most commonly presents on the buttocks and extensor legs with sparing of the face. Henoch-Schönlein purpura most often affects children aged 3 to 6 years compared to AHEI’s younger demographic (age <2 years).4,5 Clinically, HSP presents with palpable purpura and 1 or more of the following features: diffuse abdominal pain, arthritis/arthralgia, renal involvement, and skin or renal biopsy showing predominant IgA deposition.2,6

Both AHEI and HSP show leukocytoclastic vasculitis on histopathology.2-4,6,7 Positive perivascular IgA staining on DIF is strongly associated with HSP, but nearly one-quarter of AHEI cases also show this deposition pattern2,4,7; therefore, DIF alone cannot exclude a diagnosis of AHEI.

Differential Diagnosis

Alternative diagnoses to consider with AHEI include drug-induced vasculitis, erythema multiforme, HSP, Kawasaki disease, meningococcemia, nonaccidental skin bruising, Rocky Mountain spotted fever, septic vasculitis, and urticarial vasculitis (Table).2-4,6-8

Treatment

Acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy is self-limited, with only rare reports of extracutaneous involvement. Supportive treatment is indicated because spontaneous recovery without sequelae is expected within 21 days.2,3,6 If edema is symptomatic, as was the case with our patient, corticosteroids may shorten the disease course.3

Conclusion

Our case highlights the need to combine clinical history, physical examination, and histopathologic analysis to differentiate between AHEI and HSP, which is important for 2 reasons: (1) it helps with the decision to undertake active or observational treatment, and (2) it helps the clinician counsel the patient and guardians regarding potential associated renal and GI risks.

- Snow IM. Purpura, urticaria and angioneurotic edema of the hands and feet in a nursing baby. JAMA. 1913;61:18-19.

- Fiore E, Rizzi M, Ragazzi M, et al. Acute hemorrhagic edema of young children (cockade purpura and edema): a case series and systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:684-695.

- Freitas P, Bygum A. Visual impairment caused by periorbital edema in an infant with acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:e132-e135.

- Legrain V, Lejean S, Taïeb A, et al. Infantile acute hemorrhagic edema of the skin: study of ten cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;24:17-22.

- Breda L, Franchini S, Marzetti V, et al. Escherichia coli urinary infection as a cause of acute hemorrhagic edema in infancy. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015;32:e309-e311.

- Ozen S, Ruperto N, Dillon MJ, et al. EULAR/PReS endorsed consensus criteria for the classification of childhood vasculitides. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:936-941.

- Saraclar Y, Tinaztepe K, Adalioğlu G, et al. Acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy (AHEI)—a variant of Henoch-Schönlein purpura or a distinct clinical entity? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1990;86:473-483.

- Shinkai K, Fox L. Cutaneous vasculitis. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo J, Schaffer J, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. China: Elsevier Limited; 2012:385-410.

Acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy (AHEI) is an uncommon leukocytoclastic vasculitis affecting children aged 6 to 24 months; Henoch-Schönlein purpura (HSP) is the most common misdiagnosis. The 2 entities should be differentiated, as HSP may have renal and gastrointestinal (GI) comorbidities that need serial follow-up, whereas AHEI follows a benign course without systemic sequelae. Patient history and physical examination are the most important factors in differentiating the 2 diseases; histopathologic and direct immunofluorescence (DIF) analyses may lend further diagnostic confidence.

We report the case of a 10-month-old previously healthy boy who presented with acute rash, edema, and low-grade fever in the setting of recent diarrhea. We differentiate between AHEI and HSP to help prevent misdiagnosis by health care providers.

Case Report

A 10-month-old previously healthy boy presented to the emergency department (ED) for evaluation of a rash and swelling of 4 days’ duration. He had nonbloody diarrhea 1 week prior; soon after, he developed bilateral lower leg edema and rash. On evaluation in a different ED, he had a low-grade fever (rectal temperature, 38.0°C) but normal blood work, including complete blood cell count, basic metabolic panel, and coagulation studies. The patient was discharged to outpatient follow-up with his pediatrician who reported normal urinalysis.

Due to progression of the rash, the patient presented to our ED 3 days after his initial ED assessment. Dermatology was consulted. At the time of presentation, he was afebrile but with GI upset and fussiness. His parents denied additional symptoms or blood in urine or stool. Physical examination revealed a nontoxic-appearing infant with scattered palpable, annular, purpuric papules coalescing into plaques on both legs and feet (Figure 1), with sparse petechiae noted on the lower abdomen. The cheeks had scattered purpuric papules and plaques bilaterally, a few with a small central crust (Figure 2), and the right superior helix had a faint purpuric macule. The hands had a few pink edematous coalescing papules.

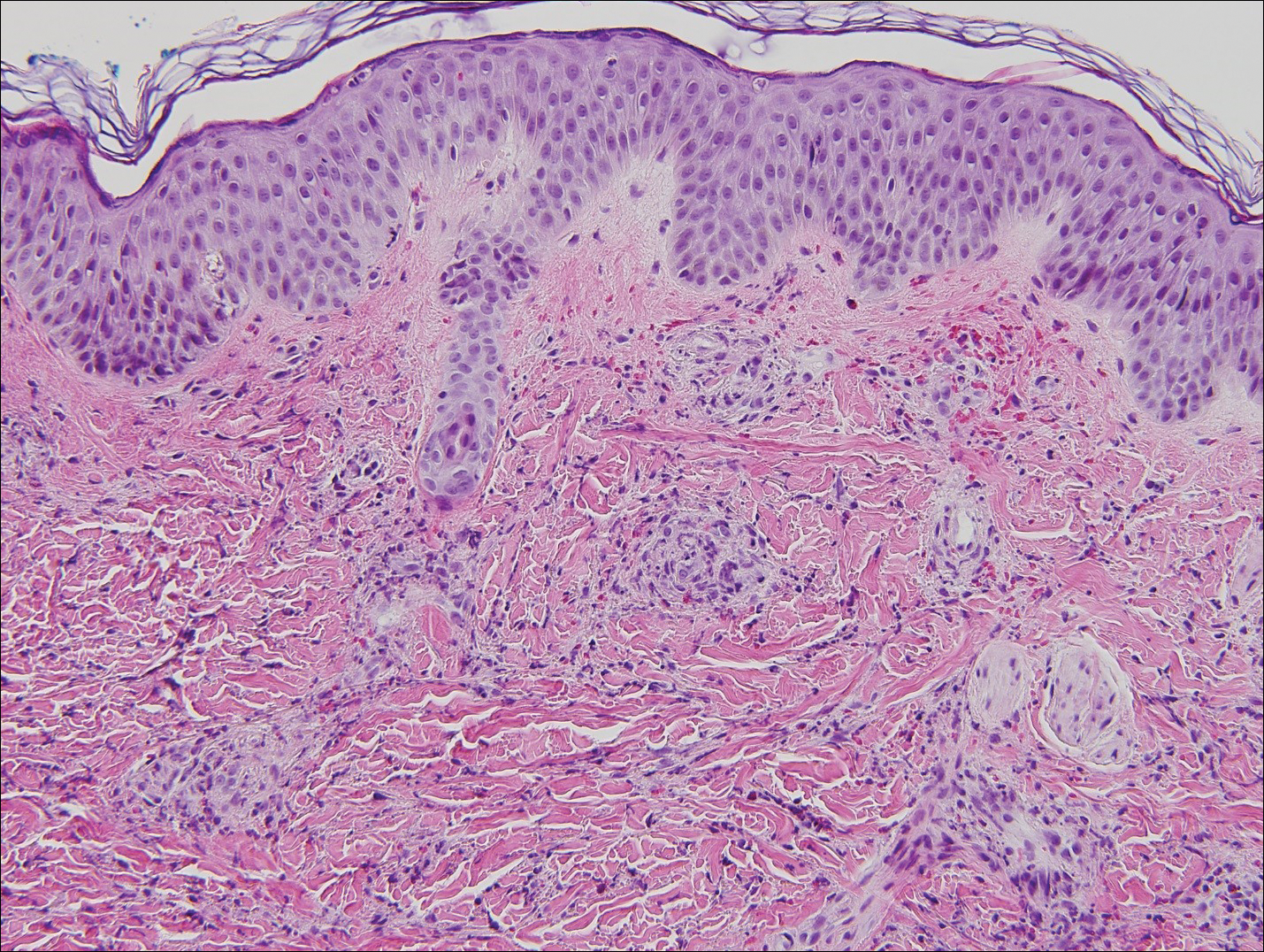

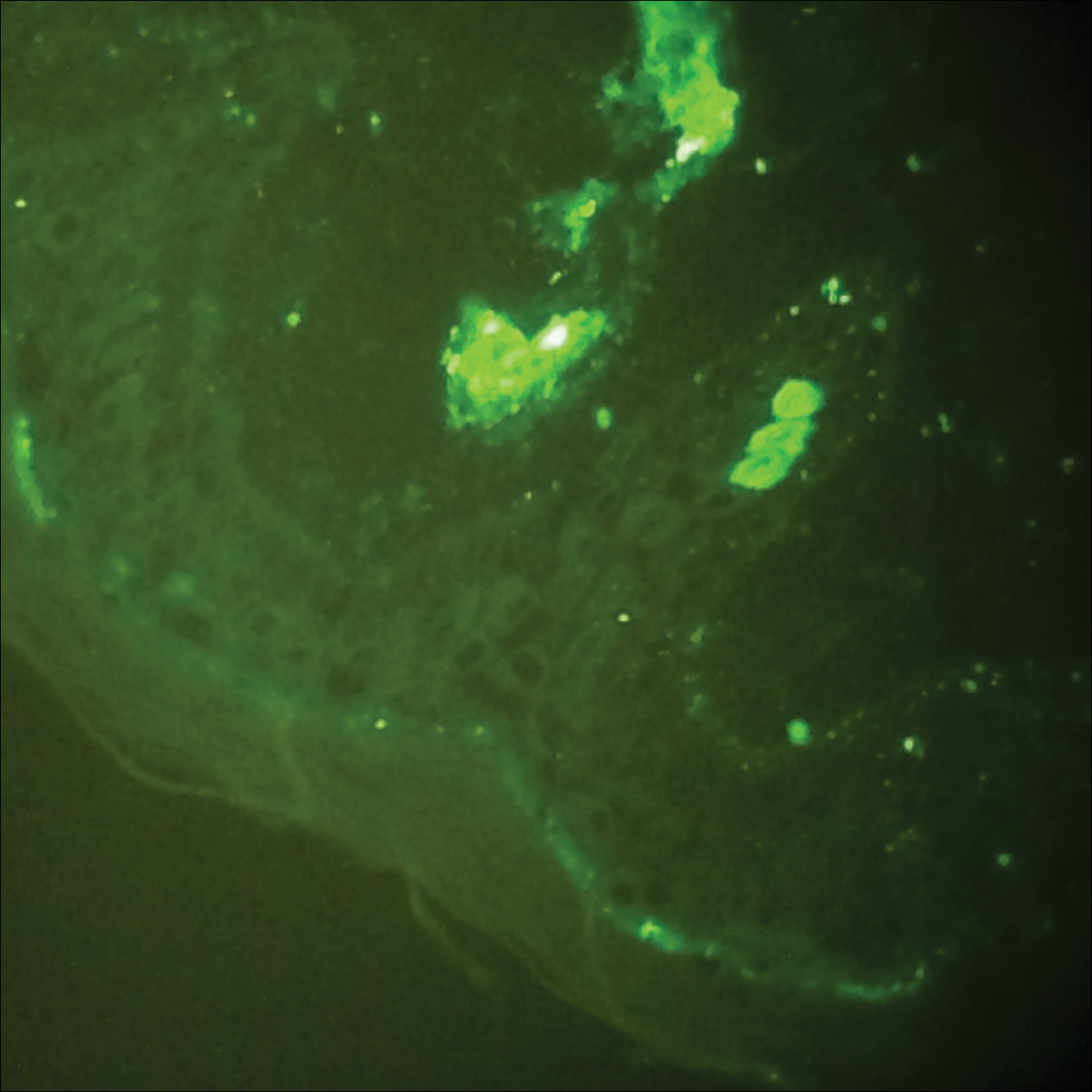

Histopathologic analyses with hematoxylin and eosin staining (Figure 3) and DIF (Figure 4) were performed from within a representative purpuric plaque on the right hip. Direct immunofluorescence was performed to evaluate for an IgA vasculitis versus an alternative type of vasculitis. The hematoxylin and eosin–stained specimen demonstrated a dermal perivascular infiltrate involving superficial and deep vessels with neutrophils, karyorrhexis, and erythrocyte extravasation. The endothelium was intact, with a mild suggestion of fibrinoid change of the blood vessel walls. Direct immunofluorescence revealed granular deposition of IgA, C3, and fibrinogen in multiple dermal blood vessels. Combined, the specimens were interpreted as evolving IgA-associated leukocytoclastic vasculitis.

The case was reviewed with our 2 department pediatric dermatologists; a diagnosis of AHEI was made based on the clinical and supportive histopathological presentations. The patient’s parents chose active treatment with a 2-week taper of oral prednisone because of the patient’s discomfort with edema. No GI or adverse renal sequelae, including findings on urinalysis, were reported at 1-month hospital follow-up with dermatology and pediatrics.

Comment

Incidence and Clinical Characteristics

Acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy is an uncommon leukocytoclastic vasculitis first described in the United States by Snow1 in 1913. Other names for the disorder include acute hemorrhagic edema of young children, cockade purpura and edema, Finkelstein disease, and Seidlmayer disease.2 Boys are affected more often than girls, with most children presenting at 6 to 24 months of age. Most affected children experience a prodrome of simple respiratory tract illness (most common), diarrhea (as in our case), or urinary tract infection.2 The exact pathophysiology behind AHEI is unknown, but it is thought to be an immune complex–mediated disease evidenced by the fact that infection, use of medication, or immunization precedes most cases.3,4

Diagnosis

Acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy is diagnosed clinically, with or without the support of skin biopsy. It should be differentiated from HSP because of renal and GI sequelae that HSP portends compared to the benign course of AHEI.2 Notably, some health care providers consider AHEI a benign variant of HSP.2,3

Characteristically, AHEI patients are nontoxic-appearing infants with a low-grade fever who develop relatively large (1–5 cm) targetoid purpuric lesions and indurated nonpitting edema of the extremities.2,5 Purpura in AHEI frequently occurs on the face, ears, and upper and lower extremities, whereas purpura in HSP most commonly presents on the buttocks and extensor legs with sparing of the face. Henoch-Schönlein purpura most often affects children aged 3 to 6 years compared to AHEI’s younger demographic (age <2 years).4,5 Clinically, HSP presents with palpable purpura and 1 or more of the following features: diffuse abdominal pain, arthritis/arthralgia, renal involvement, and skin or renal biopsy showing predominant IgA deposition.2,6

Both AHEI and HSP show leukocytoclastic vasculitis on histopathology.2-4,6,7 Positive perivascular IgA staining on DIF is strongly associated with HSP, but nearly one-quarter of AHEI cases also show this deposition pattern2,4,7; therefore, DIF alone cannot exclude a diagnosis of AHEI.

Differential Diagnosis

Alternative diagnoses to consider with AHEI include drug-induced vasculitis, erythema multiforme, HSP, Kawasaki disease, meningococcemia, nonaccidental skin bruising, Rocky Mountain spotted fever, septic vasculitis, and urticarial vasculitis (Table).2-4,6-8

Treatment

Acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy is self-limited, with only rare reports of extracutaneous involvement. Supportive treatment is indicated because spontaneous recovery without sequelae is expected within 21 days.2,3,6 If edema is symptomatic, as was the case with our patient, corticosteroids may shorten the disease course.3

Conclusion

Our case highlights the need to combine clinical history, physical examination, and histopathologic analysis to differentiate between AHEI and HSP, which is important for 2 reasons: (1) it helps with the decision to undertake active or observational treatment, and (2) it helps the clinician counsel the patient and guardians regarding potential associated renal and GI risks.

Acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy (AHEI) is an uncommon leukocytoclastic vasculitis affecting children aged 6 to 24 months; Henoch-Schönlein purpura (HSP) is the most common misdiagnosis. The 2 entities should be differentiated, as HSP may have renal and gastrointestinal (GI) comorbidities that need serial follow-up, whereas AHEI follows a benign course without systemic sequelae. Patient history and physical examination are the most important factors in differentiating the 2 diseases; histopathologic and direct immunofluorescence (DIF) analyses may lend further diagnostic confidence.

We report the case of a 10-month-old previously healthy boy who presented with acute rash, edema, and low-grade fever in the setting of recent diarrhea. We differentiate between AHEI and HSP to help prevent misdiagnosis by health care providers.

Case Report

A 10-month-old previously healthy boy presented to the emergency department (ED) for evaluation of a rash and swelling of 4 days’ duration. He had nonbloody diarrhea 1 week prior; soon after, he developed bilateral lower leg edema and rash. On evaluation in a different ED, he had a low-grade fever (rectal temperature, 38.0°C) but normal blood work, including complete blood cell count, basic metabolic panel, and coagulation studies. The patient was discharged to outpatient follow-up with his pediatrician who reported normal urinalysis.

Due to progression of the rash, the patient presented to our ED 3 days after his initial ED assessment. Dermatology was consulted. At the time of presentation, he was afebrile but with GI upset and fussiness. His parents denied additional symptoms or blood in urine or stool. Physical examination revealed a nontoxic-appearing infant with scattered palpable, annular, purpuric papules coalescing into plaques on both legs and feet (Figure 1), with sparse petechiae noted on the lower abdomen. The cheeks had scattered purpuric papules and plaques bilaterally, a few with a small central crust (Figure 2), and the right superior helix had a faint purpuric macule. The hands had a few pink edematous coalescing papules.

Histopathologic analyses with hematoxylin and eosin staining (Figure 3) and DIF (Figure 4) were performed from within a representative purpuric plaque on the right hip. Direct immunofluorescence was performed to evaluate for an IgA vasculitis versus an alternative type of vasculitis. The hematoxylin and eosin–stained specimen demonstrated a dermal perivascular infiltrate involving superficial and deep vessels with neutrophils, karyorrhexis, and erythrocyte extravasation. The endothelium was intact, with a mild suggestion of fibrinoid change of the blood vessel walls. Direct immunofluorescence revealed granular deposition of IgA, C3, and fibrinogen in multiple dermal blood vessels. Combined, the specimens were interpreted as evolving IgA-associated leukocytoclastic vasculitis.

The case was reviewed with our 2 department pediatric dermatologists; a diagnosis of AHEI was made based on the clinical and supportive histopathological presentations. The patient’s parents chose active treatment with a 2-week taper of oral prednisone because of the patient’s discomfort with edema. No GI or adverse renal sequelae, including findings on urinalysis, were reported at 1-month hospital follow-up with dermatology and pediatrics.

Comment

Incidence and Clinical Characteristics

Acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy is an uncommon leukocytoclastic vasculitis first described in the United States by Snow1 in 1913. Other names for the disorder include acute hemorrhagic edema of young children, cockade purpura and edema, Finkelstein disease, and Seidlmayer disease.2 Boys are affected more often than girls, with most children presenting at 6 to 24 months of age. Most affected children experience a prodrome of simple respiratory tract illness (most common), diarrhea (as in our case), or urinary tract infection.2 The exact pathophysiology behind AHEI is unknown, but it is thought to be an immune complex–mediated disease evidenced by the fact that infection, use of medication, or immunization precedes most cases.3,4

Diagnosis

Acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy is diagnosed clinically, with or without the support of skin biopsy. It should be differentiated from HSP because of renal and GI sequelae that HSP portends compared to the benign course of AHEI.2 Notably, some health care providers consider AHEI a benign variant of HSP.2,3

Characteristically, AHEI patients are nontoxic-appearing infants with a low-grade fever who develop relatively large (1–5 cm) targetoid purpuric lesions and indurated nonpitting edema of the extremities.2,5 Purpura in AHEI frequently occurs on the face, ears, and upper and lower extremities, whereas purpura in HSP most commonly presents on the buttocks and extensor legs with sparing of the face. Henoch-Schönlein purpura most often affects children aged 3 to 6 years compared to AHEI’s younger demographic (age <2 years).4,5 Clinically, HSP presents with palpable purpura and 1 or more of the following features: diffuse abdominal pain, arthritis/arthralgia, renal involvement, and skin or renal biopsy showing predominant IgA deposition.2,6

Both AHEI and HSP show leukocytoclastic vasculitis on histopathology.2-4,6,7 Positive perivascular IgA staining on DIF is strongly associated with HSP, but nearly one-quarter of AHEI cases also show this deposition pattern2,4,7; therefore, DIF alone cannot exclude a diagnosis of AHEI.

Differential Diagnosis

Alternative diagnoses to consider with AHEI include drug-induced vasculitis, erythema multiforme, HSP, Kawasaki disease, meningococcemia, nonaccidental skin bruising, Rocky Mountain spotted fever, septic vasculitis, and urticarial vasculitis (Table).2-4,6-8

Treatment

Acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy is self-limited, with only rare reports of extracutaneous involvement. Supportive treatment is indicated because spontaneous recovery without sequelae is expected within 21 days.2,3,6 If edema is symptomatic, as was the case with our patient, corticosteroids may shorten the disease course.3

Conclusion

Our case highlights the need to combine clinical history, physical examination, and histopathologic analysis to differentiate between AHEI and HSP, which is important for 2 reasons: (1) it helps with the decision to undertake active or observational treatment, and (2) it helps the clinician counsel the patient and guardians regarding potential associated renal and GI risks.

- Snow IM. Purpura, urticaria and angioneurotic edema of the hands and feet in a nursing baby. JAMA. 1913;61:18-19.

- Fiore E, Rizzi M, Ragazzi M, et al. Acute hemorrhagic edema of young children (cockade purpura and edema): a case series and systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:684-695.

- Freitas P, Bygum A. Visual impairment caused by periorbital edema in an infant with acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:e132-e135.

- Legrain V, Lejean S, Taïeb A, et al. Infantile acute hemorrhagic edema of the skin: study of ten cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;24:17-22.

- Breda L, Franchini S, Marzetti V, et al. Escherichia coli urinary infection as a cause of acute hemorrhagic edema in infancy. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015;32:e309-e311.

- Ozen S, Ruperto N, Dillon MJ, et al. EULAR/PReS endorsed consensus criteria for the classification of childhood vasculitides. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:936-941.

- Saraclar Y, Tinaztepe K, Adalioğlu G, et al. Acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy (AHEI)—a variant of Henoch-Schönlein purpura or a distinct clinical entity? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1990;86:473-483.

- Shinkai K, Fox L. Cutaneous vasculitis. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo J, Schaffer J, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. China: Elsevier Limited; 2012:385-410.

- Snow IM. Purpura, urticaria and angioneurotic edema of the hands and feet in a nursing baby. JAMA. 1913;61:18-19.

- Fiore E, Rizzi M, Ragazzi M, et al. Acute hemorrhagic edema of young children (cockade purpura and edema): a case series and systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:684-695.

- Freitas P, Bygum A. Visual impairment caused by periorbital edema in an infant with acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:e132-e135.

- Legrain V, Lejean S, Taïeb A, et al. Infantile acute hemorrhagic edema of the skin: study of ten cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;24:17-22.

- Breda L, Franchini S, Marzetti V, et al. Escherichia coli urinary infection as a cause of acute hemorrhagic edema in infancy. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015;32:e309-e311.

- Ozen S, Ruperto N, Dillon MJ, et al. EULAR/PReS endorsed consensus criteria for the classification of childhood vasculitides. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:936-941.

- Saraclar Y, Tinaztepe K, Adalioğlu G, et al. Acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy (AHEI)—a variant of Henoch-Schönlein purpura or a distinct clinical entity? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1990;86:473-483.

- Shinkai K, Fox L. Cutaneous vasculitis. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo J, Schaffer J, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. China: Elsevier Limited; 2012:385-410.

Practice Points

- Acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy (AHEI) is an uncommon benign leukocytoclastic vasculitis of unknown precise pathophysiology that is thought be immune complex mediated.

- Clinical history, physical examination, and histopathologic analysis combine to allow the important differentiation between AHEI and Henoch-Schönlein purpura (HSP).

- Differentiation between AHEI and HSP determines treatment decisions and indicates the need for counseling on potential associated renal and gastrointestinal risks of HSP.