User login

Plagues that will haunt us long after the COVID-19 pandemic is gone

As we struggle to gradually emerge from the horrid coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic that has disrupted our lives and killed hundreds of thousands of people in the United States, we harbor the hope that life will return to “normal.” But while it will certainly be a great relief to put this deadly virus behind us, many other epidemics will continue to plague our society and taint our culture.

Scientific ingenuity has led to the development of several vaccines in record time (aka “warp speed”) that will help defeat the deadly scourge of COVID-19. The pandemic is likely to peter out 2 years after its onset. We will all be grateful for such a rapid resolution of the worst health crisis the world has faced in a century, which will enable medical, economic, and social recovery. But as we eventually resume our lives and rejoice in resuming the pursuit of happiness, we will quickly realize that all is not well in our society just because the viral pandemic is gone.

Perhaps the ordeal of the COVID-19 pandemic, and the agony that was universally shared, will open our collective eyes to a jarring reality: many other epidemics will continue to permeate society and cause endless grief and suffering to many of our fellow humans. And thanks to our training as psychiatric physicians, we have developed extra “receptors” to the darker side of the human condition. As we help many of our psychiatric patients rendered sicker under the unbearable stress of the pandemic, we must not overlook the plight of so many others who do not show up in our clinics for health care, yet suffer enormously but imperceptibly. And no vaccine can come to the rescue of those who continue to live in quiet desperation.

Long-standing epidemics

It is truly unfortunate that many of the epidemics I am referring to have persisted for so long that they have become “fixtures” of contemporary societies. They have become “endemic epidemics” with no urgency to squelch them, as with the COVID-19 pandemic. The benign neglect that perpetuates these serious epidemics has had a malignant effect of “grudging resignation” that nothing can be done to reverse them. Unlike the viral epidemic that engulfed everyone around the world and triggered a massive and unified push to defeat the virus, these long-standing epidemics continue to afflict subgroups who are left to fend for themselves. These individuals deserve our empathy and warrant our determination to lift them from their miserable existence.

Consider some of the widespread epidemics that preceded the pandemic and will, in all likelihood, persist after the pandemic’s burden is lifted:

- millions of people living in poverty and hunger

- widespread racism

- smoldering social injustice

- appalling human trafficking, especially targeting children and women

- child abuse and neglect that leads to psychosis, depression, and suicide in adulthood

- gun violence, which kills many innocent people

- domestic violence that inflicts both physical and mental harm on families

- suicide, both attempts and completions, which continues to increase annually

- the festering stigma of mental illness that adds insult to injury for psychiatric patients

- alcohol and drug addictions, which destroy lives and corrode the fabric of society

- lack of access to mental health care for millions of people who need it

- lack of parity for psychiatric disorders, which is so unjust for our patients

- venomous political hatred and hyperpartisanship, which permeates our culture and can lead to violence, as we recently witnessed

- physician burnout, due to many causes, even before the stresses of COVID-19

- the ongoing agony of wars and terrorism, including dangerous cyberattacks

- the deleterious effect of social media on everyone, especially children.

Most of these epidemics claim thousands of lives each year, and yet no concerted public health effort is being mounted to counteract them, as we are seeing with the COVID-19 pandemic. Much is being written about each of them, but there has been little tangible action, so they persist. They have become a perpetual underbelly of our society that is essentially ignored or simply given the usual lip service.

It will take a herculean effort by policymakers, the judicial system, the medical establishment, and faith organizations to put an end to these life-threatening epidemics. It may appear too daunting to mount a war on so many fronts, but that should not deter us all from launching a strategic plan to create meaningful tactics and solutions. And just as was done with the COVID-19 pandemic, both mitigation measures as well as effective interventions must be employed in this campaign against the epidemic “hydra.”

Continue to: It is tragic...

It is tragic that so many fellow humans are allowed to suffer or die while the rest of us watch, or worse, turn a blind eye and never get involved. A civilized society must never neglect so many of its suffering citizens. As psychiatrists, we are aware of those human travesties around us, but we are often so overwhelmed with our work and personal responsibilities that few of us are passionately advocating or setting aside some time for those victimized by one or more of these endemic pandemics. And unless we all decide to be actively, meaningfully involved, many lives will continue to be lost every day, but without the daily “casualty count” displayed on television screens, as is the case with COVID-19 causalities.

Regrettably, maybe that old saw is true: out of sight, out of mind.

As we struggle to gradually emerge from the horrid coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic that has disrupted our lives and killed hundreds of thousands of people in the United States, we harbor the hope that life will return to “normal.” But while it will certainly be a great relief to put this deadly virus behind us, many other epidemics will continue to plague our society and taint our culture.

Scientific ingenuity has led to the development of several vaccines in record time (aka “warp speed”) that will help defeat the deadly scourge of COVID-19. The pandemic is likely to peter out 2 years after its onset. We will all be grateful for such a rapid resolution of the worst health crisis the world has faced in a century, which will enable medical, economic, and social recovery. But as we eventually resume our lives and rejoice in resuming the pursuit of happiness, we will quickly realize that all is not well in our society just because the viral pandemic is gone.

Perhaps the ordeal of the COVID-19 pandemic, and the agony that was universally shared, will open our collective eyes to a jarring reality: many other epidemics will continue to permeate society and cause endless grief and suffering to many of our fellow humans. And thanks to our training as psychiatric physicians, we have developed extra “receptors” to the darker side of the human condition. As we help many of our psychiatric patients rendered sicker under the unbearable stress of the pandemic, we must not overlook the plight of so many others who do not show up in our clinics for health care, yet suffer enormously but imperceptibly. And no vaccine can come to the rescue of those who continue to live in quiet desperation.

Long-standing epidemics

It is truly unfortunate that many of the epidemics I am referring to have persisted for so long that they have become “fixtures” of contemporary societies. They have become “endemic epidemics” with no urgency to squelch them, as with the COVID-19 pandemic. The benign neglect that perpetuates these serious epidemics has had a malignant effect of “grudging resignation” that nothing can be done to reverse them. Unlike the viral epidemic that engulfed everyone around the world and triggered a massive and unified push to defeat the virus, these long-standing epidemics continue to afflict subgroups who are left to fend for themselves. These individuals deserve our empathy and warrant our determination to lift them from their miserable existence.

Consider some of the widespread epidemics that preceded the pandemic and will, in all likelihood, persist after the pandemic’s burden is lifted:

- millions of people living in poverty and hunger

- widespread racism

- smoldering social injustice

- appalling human trafficking, especially targeting children and women

- child abuse and neglect that leads to psychosis, depression, and suicide in adulthood

- gun violence, which kills many innocent people

- domestic violence that inflicts both physical and mental harm on families

- suicide, both attempts and completions, which continues to increase annually

- the festering stigma of mental illness that adds insult to injury for psychiatric patients

- alcohol and drug addictions, which destroy lives and corrode the fabric of society

- lack of access to mental health care for millions of people who need it

- lack of parity for psychiatric disorders, which is so unjust for our patients

- venomous political hatred and hyperpartisanship, which permeates our culture and can lead to violence, as we recently witnessed

- physician burnout, due to many causes, even before the stresses of COVID-19

- the ongoing agony of wars and terrorism, including dangerous cyberattacks

- the deleterious effect of social media on everyone, especially children.

Most of these epidemics claim thousands of lives each year, and yet no concerted public health effort is being mounted to counteract them, as we are seeing with the COVID-19 pandemic. Much is being written about each of them, but there has been little tangible action, so they persist. They have become a perpetual underbelly of our society that is essentially ignored or simply given the usual lip service.

It will take a herculean effort by policymakers, the judicial system, the medical establishment, and faith organizations to put an end to these life-threatening epidemics. It may appear too daunting to mount a war on so many fronts, but that should not deter us all from launching a strategic plan to create meaningful tactics and solutions. And just as was done with the COVID-19 pandemic, both mitigation measures as well as effective interventions must be employed in this campaign against the epidemic “hydra.”

Continue to: It is tragic...

It is tragic that so many fellow humans are allowed to suffer or die while the rest of us watch, or worse, turn a blind eye and never get involved. A civilized society must never neglect so many of its suffering citizens. As psychiatrists, we are aware of those human travesties around us, but we are often so overwhelmed with our work and personal responsibilities that few of us are passionately advocating or setting aside some time for those victimized by one or more of these endemic pandemics. And unless we all decide to be actively, meaningfully involved, many lives will continue to be lost every day, but without the daily “casualty count” displayed on television screens, as is the case with COVID-19 causalities.

Regrettably, maybe that old saw is true: out of sight, out of mind.

As we struggle to gradually emerge from the horrid coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic that has disrupted our lives and killed hundreds of thousands of people in the United States, we harbor the hope that life will return to “normal.” But while it will certainly be a great relief to put this deadly virus behind us, many other epidemics will continue to plague our society and taint our culture.

Scientific ingenuity has led to the development of several vaccines in record time (aka “warp speed”) that will help defeat the deadly scourge of COVID-19. The pandemic is likely to peter out 2 years after its onset. We will all be grateful for such a rapid resolution of the worst health crisis the world has faced in a century, which will enable medical, economic, and social recovery. But as we eventually resume our lives and rejoice in resuming the pursuit of happiness, we will quickly realize that all is not well in our society just because the viral pandemic is gone.

Perhaps the ordeal of the COVID-19 pandemic, and the agony that was universally shared, will open our collective eyes to a jarring reality: many other epidemics will continue to permeate society and cause endless grief and suffering to many of our fellow humans. And thanks to our training as psychiatric physicians, we have developed extra “receptors” to the darker side of the human condition. As we help many of our psychiatric patients rendered sicker under the unbearable stress of the pandemic, we must not overlook the plight of so many others who do not show up in our clinics for health care, yet suffer enormously but imperceptibly. And no vaccine can come to the rescue of those who continue to live in quiet desperation.

Long-standing epidemics

It is truly unfortunate that many of the epidemics I am referring to have persisted for so long that they have become “fixtures” of contemporary societies. They have become “endemic epidemics” with no urgency to squelch them, as with the COVID-19 pandemic. The benign neglect that perpetuates these serious epidemics has had a malignant effect of “grudging resignation” that nothing can be done to reverse them. Unlike the viral epidemic that engulfed everyone around the world and triggered a massive and unified push to defeat the virus, these long-standing epidemics continue to afflict subgroups who are left to fend for themselves. These individuals deserve our empathy and warrant our determination to lift them from their miserable existence.

Consider some of the widespread epidemics that preceded the pandemic and will, in all likelihood, persist after the pandemic’s burden is lifted:

- millions of people living in poverty and hunger

- widespread racism

- smoldering social injustice

- appalling human trafficking, especially targeting children and women

- child abuse and neglect that leads to psychosis, depression, and suicide in adulthood

- gun violence, which kills many innocent people

- domestic violence that inflicts both physical and mental harm on families

- suicide, both attempts and completions, which continues to increase annually

- the festering stigma of mental illness that adds insult to injury for psychiatric patients

- alcohol and drug addictions, which destroy lives and corrode the fabric of society

- lack of access to mental health care for millions of people who need it

- lack of parity for psychiatric disorders, which is so unjust for our patients

- venomous political hatred and hyperpartisanship, which permeates our culture and can lead to violence, as we recently witnessed

- physician burnout, due to many causes, even before the stresses of COVID-19

- the ongoing agony of wars and terrorism, including dangerous cyberattacks

- the deleterious effect of social media on everyone, especially children.

Most of these epidemics claim thousands of lives each year, and yet no concerted public health effort is being mounted to counteract them, as we are seeing with the COVID-19 pandemic. Much is being written about each of them, but there has been little tangible action, so they persist. They have become a perpetual underbelly of our society that is essentially ignored or simply given the usual lip service.

It will take a herculean effort by policymakers, the judicial system, the medical establishment, and faith organizations to put an end to these life-threatening epidemics. It may appear too daunting to mount a war on so many fronts, but that should not deter us all from launching a strategic plan to create meaningful tactics and solutions. And just as was done with the COVID-19 pandemic, both mitigation measures as well as effective interventions must be employed in this campaign against the epidemic “hydra.”

Continue to: It is tragic...

It is tragic that so many fellow humans are allowed to suffer or die while the rest of us watch, or worse, turn a blind eye and never get involved. A civilized society must never neglect so many of its suffering citizens. As psychiatrists, we are aware of those human travesties around us, but we are often so overwhelmed with our work and personal responsibilities that few of us are passionately advocating or setting aside some time for those victimized by one or more of these endemic pandemics. And unless we all decide to be actively, meaningfully involved, many lives will continue to be lost every day, but without the daily “casualty count” displayed on television screens, as is the case with COVID-19 causalities.

Regrettably, maybe that old saw is true: out of sight, out of mind.

Let’s ‘cancel’ these obsolete terms in DSM

Psychiatry has made significant scientific advances over the past century. However, it is still saddled with archaic terms, with pejorative connotations, disguised as official medical diagnoses. It is time to “cancel” those terms and replace them with ones that are neutral and have not accumulated baggage.

This process of “creative destruction” of psychiatric terminology is long overdue. It is frankly disturbing that the psychiatric jargon used around the time that the American Psychiatric Association was established 175 years ago (1844) is now considered insults and epithets. We no longer work in “lunatic asylums for the insane,” and our patients with intellectual disabilities are no longer classified as “morons,” “idiots,” or “imbeciles.” Such “diagnoses” have certainly contributed to the stigma of psychiatric brain disorders. Even the noble word “asylum” has acquired a negative valence because in the past it referred to hospitals that housed persons with serious mental illness.

Thankfully, some of the outrageous terms fabricated during the condemnable and dark era of slavery 2 centuries ago were never adopted by organized psychiatry. The absurd diagnosis of “negritude,” whose tenet was that black skin is a disease curable by whitening the skin, was “invented” by none other than Benjamin Rush, the Father of Psychiatry, whose conflicted soul was depicted by concomitantly owning a slave and positioning himself as an ardent abolitionist!

Terms that need to be replaced

Fast-forward to the modern era and consider the following:

Borderline personality disorder. It is truly tragic how this confusing and non-scientific term is used as an official diagnosis for a set of seriously ill persons. It is loaded with obloquy, indignity, and derision that completely ignore the tumult, self-harm, and disability with which patients who carry this label are burdened throughout their lives, despite being intelligent. This is a serious brain disorder that has been shown to be highly genetic and is characterized by many well-established structural brain abnormalities that have been documented in neuroimaging studies.1,2 Borderline personality should not be classified as a personality disorder but as an illness with multiple signs and symptoms, including mood lability, anger, impulsivity, self-cutting, suicidal urges, feelings of abandonment, and micro-psychotic episodes. A more clinically accurate term should be coined very soon to replace borderline personality, which should be discarded to the trash heap of obsolete psychiatric terms, and no longer inflicted on patients.

Neurosis. What is the justification for continuing to use the term “neurotic” for a person who has an anxiety disorder? Is it used because Jung and Freud propagated the term “neurosis” (after it was coined by William Cullen in 1769)? Neurosis has degenerated from a psychiatric diagnosis to a scornful snub that must never be used for any patient.

Schizophrenia. This diagnosis, coined by Eugen Bleuler to replace the narrow and pessimistic “dementia praecox” proposed by Emil Kraepelin in the 1920s, initially seemed to be a neutral description of a thought disorder (split associations, not split personality). Bleuler was perceptive enough to call his book Dementia Praecox or the Group of Schizophrenias, which is consistent with the modern scientific research that confirms schizophrenia is a very heterogeneous syndrome with hundreds of genetic and environmental biotypes with a similar phenotype but a wide range of severity, treatment response, and functional outcomes. However, in subsequent decades, schizophrenia became one of the most demeaning labels in psychiatry, casting a shadow of hopelessness and disability on the people who have this serious neurologic condition with many psychiatric symptoms. The term that should replace schizophrenia should be no more degrading than stroke, multiple sclerosis, or myocardial infarction.

Continue to: Over the past 15 years...

Over the past 15 years, an expanding group of schizophrenia experts have agreed that this term must be changed to one that reflects the core features of this syndrome, and have proposed terms such as “salience syndrome,” “psychosis-spectrum,” and “reality distortion and cognitive impairment disorder.”3 In fact, several countries have already adopted a new official diagnosis for schizophrenia.4 Japan now uses the term “integration disorder,” which has significantly reduced the stigma of this brain disorder.5 South Korea changed the name to “attunement disorder.” Hong Kong and Taiwan now use “dysfunction of thought and perception.” Some researchers recommend calling schizophrenia “Bleuler’s syndrome,” a neutral eponymous designation.

One of the most irritating things about the term schizophrenia is the widespread misconception that it means “split personality.” This prompts some sports announcers to call a football team “schizophrenic” if they play well in the first half and badly in the second. The stock market is labeled “schizophrenic” if it goes up one day and way down on the next. No other medical term is misused by the media as often as the term schizophrenia.

Narcissistic personality disorder. The origin of this diagnostic category is the concept of “malignant narcissism” coined by Erich Fromm in 1964, which he designated as “the quintessence of evil.” I strongly object to implying that evil is part of any psychiatric diagnosis. Numerous studies have found structural brain abnormalities (in both gray and white matter) in patients diagnosed with psychopathic traits.6 Later, malignant narcissism was reframed as narcissistic personality disorder in 1971 by Herbert Rosenfeld. Although malignant narcissism was never accepted by either the DSM or the International Classification of Diseases, narcissistic personality disorder has been included in the DSM for the past few decades. This diagnosis reeks of disparagement and negativity. Persons with narcissistic personality disorder have been shown to have pathological brain changes in resting-state functional connectivity,7 weakened frontostriatal white matter connectivity,8,9 and a reduced frontal thickness and cortical volume.10 A distorted sense of self and others is a socially disabling disorder that should generate empathy, not disdain. Narcissistic personality disorder should be replaced by a term that accurately describes its behavioral pathology, and should not incorporate Greek mythology.

Mania. This is another unfortunate diagnosis that immediately evokes a negative image of patients who suffer from a potentially lethal brain disorder. It was fortunate that Robert Kendall coined the term “bipolar disorder” to replace “manic-depressive illness,” but mania is still being used within bipolar disorder as a prominent clinical phase. While depression accurately describes the mood in the other phase of this disorder, the term mania evokes wild, irrational behavior. Because the actual mood symptom cluster in mania is either elation/grandiosity or irritability/anger, why not replace mania with “elation/irritability phase of bipolar disorder”? It is more descriptive of the patient’s mood and is less pejorative.

Nomenclature is vital, and words do matter, especially when used as a diagnostic medical term. Psychiatry must “cancel” its archaic names, which are infused with negative connotations. Reinventing the psychiatric lexicon is a necessary act of renewal in a specialty where a poorly worded diagnostic label can morph into the equivalent of a “scarlet letter.” Think of other contemptuous terms, such as refrigerator mother, male hysteria, moral insanity, toxic parents, inadequate personality disorder, neurasthenia, or catastrophic schizophrenia.

General medicine regularly discards many of its obsolete terms.11 These include terms such as ablepsy, ague, camp fever, bloody flux, chlorosis, catarrh, consumption, dropsy, French pox, phthisis, milk sickness, and scrumpox.

Think also of how society abandoned the antediluvian names of boys and girls. Few parents these days would name their son Ackley, Allard, Arundel, Awarnach, Beldon, Durward, Grower, Kenlm, or Legolan, or name their daughter Afton, Agrona, Arantxa, Corliss, Demelza, Eartha, Maida, Obsession, Radella, or Sacrifice.In summary, a necessary part of psychiatry’s progress is shedding obsolete terminology, even if it means slaughtering some widely used “traditional” vocabulary. It is a necessary act of renewal, and the image of psychiatry will be burnished by it.

1. Nasrallah HA. Borderline personality disorder is a heritable brain disease. Current Psychiatry. 2014;13(4):19-20,32.

2. Sagarwala R, Nasrallah HA. White matter pathology in patients with borderline personality disorder: a review of controlled DTI studies. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2020;32(4):281-286.

3. Keshavan MS, Tandon R, Nasrallah HA. Renaming schizophrenia: keeping up with the facts. Schizophr Res. 2013;148(1-3):1-2.

4. Lasalvia A, Penta E, Sartorius N, et al. Should the label “schizophrenia” be abandoned? Schizophr Res. 2015;162(1-3):276-284.

5. Takahashi H, Ideno T, Okubo S, et al. Impact of changing the Japanese term for “schizophrenia” for reasons of stereotypical beliefs of schizophrenia in Japanese youth. Schizophr Res. 2009;112(1-3):149-152.

6. Johanson M, Vaurio D, Tiihunen J, et al. A systematic literature review of neuroimaging of psychopathic traits. Front Psychiatry. 2020;10:1027.

7. Yang, W, Cun L, Du X, et al. Gender differences in brain structure and resting-state functional connectivity related to narcissistic personality. Sci Rep. 2015;5:10924.

8. Chester DS, Cynam DR, Powell DK, et al. Narcissismis associated with weakened frontostriatal connectivity: a DTI study. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2016;11(7):1036-1040.

9. Nenadic I, Gullmar D, Dietzek M, et al. Brain structure in narcissistic personality disorder: a VBM and DTI pilot study. Psychiatry Res. 2015;231(2):184-186.

10. Mao Y, Sang N, Wang Y, et al. Reduced frontal cortex thickness and cortical volume associated with pathological narcissism. Neuroscience. 2016;378:51-57.

11. Nasrallah HA. The transient truths of medical ‘progress.’ Current Psychiatry. 2014;13(6):23-24.

Psychiatry has made significant scientific advances over the past century. However, it is still saddled with archaic terms, with pejorative connotations, disguised as official medical diagnoses. It is time to “cancel” those terms and replace them with ones that are neutral and have not accumulated baggage.

This process of “creative destruction” of psychiatric terminology is long overdue. It is frankly disturbing that the psychiatric jargon used around the time that the American Psychiatric Association was established 175 years ago (1844) is now considered insults and epithets. We no longer work in “lunatic asylums for the insane,” and our patients with intellectual disabilities are no longer classified as “morons,” “idiots,” or “imbeciles.” Such “diagnoses” have certainly contributed to the stigma of psychiatric brain disorders. Even the noble word “asylum” has acquired a negative valence because in the past it referred to hospitals that housed persons with serious mental illness.

Thankfully, some of the outrageous terms fabricated during the condemnable and dark era of slavery 2 centuries ago were never adopted by organized psychiatry. The absurd diagnosis of “negritude,” whose tenet was that black skin is a disease curable by whitening the skin, was “invented” by none other than Benjamin Rush, the Father of Psychiatry, whose conflicted soul was depicted by concomitantly owning a slave and positioning himself as an ardent abolitionist!

Terms that need to be replaced

Fast-forward to the modern era and consider the following:

Borderline personality disorder. It is truly tragic how this confusing and non-scientific term is used as an official diagnosis for a set of seriously ill persons. It is loaded with obloquy, indignity, and derision that completely ignore the tumult, self-harm, and disability with which patients who carry this label are burdened throughout their lives, despite being intelligent. This is a serious brain disorder that has been shown to be highly genetic and is characterized by many well-established structural brain abnormalities that have been documented in neuroimaging studies.1,2 Borderline personality should not be classified as a personality disorder but as an illness with multiple signs and symptoms, including mood lability, anger, impulsivity, self-cutting, suicidal urges, feelings of abandonment, and micro-psychotic episodes. A more clinically accurate term should be coined very soon to replace borderline personality, which should be discarded to the trash heap of obsolete psychiatric terms, and no longer inflicted on patients.

Neurosis. What is the justification for continuing to use the term “neurotic” for a person who has an anxiety disorder? Is it used because Jung and Freud propagated the term “neurosis” (after it was coined by William Cullen in 1769)? Neurosis has degenerated from a psychiatric diagnosis to a scornful snub that must never be used for any patient.

Schizophrenia. This diagnosis, coined by Eugen Bleuler to replace the narrow and pessimistic “dementia praecox” proposed by Emil Kraepelin in the 1920s, initially seemed to be a neutral description of a thought disorder (split associations, not split personality). Bleuler was perceptive enough to call his book Dementia Praecox or the Group of Schizophrenias, which is consistent with the modern scientific research that confirms schizophrenia is a very heterogeneous syndrome with hundreds of genetic and environmental biotypes with a similar phenotype but a wide range of severity, treatment response, and functional outcomes. However, in subsequent decades, schizophrenia became one of the most demeaning labels in psychiatry, casting a shadow of hopelessness and disability on the people who have this serious neurologic condition with many psychiatric symptoms. The term that should replace schizophrenia should be no more degrading than stroke, multiple sclerosis, or myocardial infarction.

Continue to: Over the past 15 years...

Over the past 15 years, an expanding group of schizophrenia experts have agreed that this term must be changed to one that reflects the core features of this syndrome, and have proposed terms such as “salience syndrome,” “psychosis-spectrum,” and “reality distortion and cognitive impairment disorder.”3 In fact, several countries have already adopted a new official diagnosis for schizophrenia.4 Japan now uses the term “integration disorder,” which has significantly reduced the stigma of this brain disorder.5 South Korea changed the name to “attunement disorder.” Hong Kong and Taiwan now use “dysfunction of thought and perception.” Some researchers recommend calling schizophrenia “Bleuler’s syndrome,” a neutral eponymous designation.

One of the most irritating things about the term schizophrenia is the widespread misconception that it means “split personality.” This prompts some sports announcers to call a football team “schizophrenic” if they play well in the first half and badly in the second. The stock market is labeled “schizophrenic” if it goes up one day and way down on the next. No other medical term is misused by the media as often as the term schizophrenia.

Narcissistic personality disorder. The origin of this diagnostic category is the concept of “malignant narcissism” coined by Erich Fromm in 1964, which he designated as “the quintessence of evil.” I strongly object to implying that evil is part of any psychiatric diagnosis. Numerous studies have found structural brain abnormalities (in both gray and white matter) in patients diagnosed with psychopathic traits.6 Later, malignant narcissism was reframed as narcissistic personality disorder in 1971 by Herbert Rosenfeld. Although malignant narcissism was never accepted by either the DSM or the International Classification of Diseases, narcissistic personality disorder has been included in the DSM for the past few decades. This diagnosis reeks of disparagement and negativity. Persons with narcissistic personality disorder have been shown to have pathological brain changes in resting-state functional connectivity,7 weakened frontostriatal white matter connectivity,8,9 and a reduced frontal thickness and cortical volume.10 A distorted sense of self and others is a socially disabling disorder that should generate empathy, not disdain. Narcissistic personality disorder should be replaced by a term that accurately describes its behavioral pathology, and should not incorporate Greek mythology.

Mania. This is another unfortunate diagnosis that immediately evokes a negative image of patients who suffer from a potentially lethal brain disorder. It was fortunate that Robert Kendall coined the term “bipolar disorder” to replace “manic-depressive illness,” but mania is still being used within bipolar disorder as a prominent clinical phase. While depression accurately describes the mood in the other phase of this disorder, the term mania evokes wild, irrational behavior. Because the actual mood symptom cluster in mania is either elation/grandiosity or irritability/anger, why not replace mania with “elation/irritability phase of bipolar disorder”? It is more descriptive of the patient’s mood and is less pejorative.

Nomenclature is vital, and words do matter, especially when used as a diagnostic medical term. Psychiatry must “cancel” its archaic names, which are infused with negative connotations. Reinventing the psychiatric lexicon is a necessary act of renewal in a specialty where a poorly worded diagnostic label can morph into the equivalent of a “scarlet letter.” Think of other contemptuous terms, such as refrigerator mother, male hysteria, moral insanity, toxic parents, inadequate personality disorder, neurasthenia, or catastrophic schizophrenia.

General medicine regularly discards many of its obsolete terms.11 These include terms such as ablepsy, ague, camp fever, bloody flux, chlorosis, catarrh, consumption, dropsy, French pox, phthisis, milk sickness, and scrumpox.

Think also of how society abandoned the antediluvian names of boys and girls. Few parents these days would name their son Ackley, Allard, Arundel, Awarnach, Beldon, Durward, Grower, Kenlm, or Legolan, or name their daughter Afton, Agrona, Arantxa, Corliss, Demelza, Eartha, Maida, Obsession, Radella, or Sacrifice.In summary, a necessary part of psychiatry’s progress is shedding obsolete terminology, even if it means slaughtering some widely used “traditional” vocabulary. It is a necessary act of renewal, and the image of psychiatry will be burnished by it.

Psychiatry has made significant scientific advances over the past century. However, it is still saddled with archaic terms, with pejorative connotations, disguised as official medical diagnoses. It is time to “cancel” those terms and replace them with ones that are neutral and have not accumulated baggage.

This process of “creative destruction” of psychiatric terminology is long overdue. It is frankly disturbing that the psychiatric jargon used around the time that the American Psychiatric Association was established 175 years ago (1844) is now considered insults and epithets. We no longer work in “lunatic asylums for the insane,” and our patients with intellectual disabilities are no longer classified as “morons,” “idiots,” or “imbeciles.” Such “diagnoses” have certainly contributed to the stigma of psychiatric brain disorders. Even the noble word “asylum” has acquired a negative valence because in the past it referred to hospitals that housed persons with serious mental illness.

Thankfully, some of the outrageous terms fabricated during the condemnable and dark era of slavery 2 centuries ago were never adopted by organized psychiatry. The absurd diagnosis of “negritude,” whose tenet was that black skin is a disease curable by whitening the skin, was “invented” by none other than Benjamin Rush, the Father of Psychiatry, whose conflicted soul was depicted by concomitantly owning a slave and positioning himself as an ardent abolitionist!

Terms that need to be replaced

Fast-forward to the modern era and consider the following:

Borderline personality disorder. It is truly tragic how this confusing and non-scientific term is used as an official diagnosis for a set of seriously ill persons. It is loaded with obloquy, indignity, and derision that completely ignore the tumult, self-harm, and disability with which patients who carry this label are burdened throughout their lives, despite being intelligent. This is a serious brain disorder that has been shown to be highly genetic and is characterized by many well-established structural brain abnormalities that have been documented in neuroimaging studies.1,2 Borderline personality should not be classified as a personality disorder but as an illness with multiple signs and symptoms, including mood lability, anger, impulsivity, self-cutting, suicidal urges, feelings of abandonment, and micro-psychotic episodes. A more clinically accurate term should be coined very soon to replace borderline personality, which should be discarded to the trash heap of obsolete psychiatric terms, and no longer inflicted on patients.

Neurosis. What is the justification for continuing to use the term “neurotic” for a person who has an anxiety disorder? Is it used because Jung and Freud propagated the term “neurosis” (after it was coined by William Cullen in 1769)? Neurosis has degenerated from a psychiatric diagnosis to a scornful snub that must never be used for any patient.

Schizophrenia. This diagnosis, coined by Eugen Bleuler to replace the narrow and pessimistic “dementia praecox” proposed by Emil Kraepelin in the 1920s, initially seemed to be a neutral description of a thought disorder (split associations, not split personality). Bleuler was perceptive enough to call his book Dementia Praecox or the Group of Schizophrenias, which is consistent with the modern scientific research that confirms schizophrenia is a very heterogeneous syndrome with hundreds of genetic and environmental biotypes with a similar phenotype but a wide range of severity, treatment response, and functional outcomes. However, in subsequent decades, schizophrenia became one of the most demeaning labels in psychiatry, casting a shadow of hopelessness and disability on the people who have this serious neurologic condition with many psychiatric symptoms. The term that should replace schizophrenia should be no more degrading than stroke, multiple sclerosis, or myocardial infarction.

Continue to: Over the past 15 years...

Over the past 15 years, an expanding group of schizophrenia experts have agreed that this term must be changed to one that reflects the core features of this syndrome, and have proposed terms such as “salience syndrome,” “psychosis-spectrum,” and “reality distortion and cognitive impairment disorder.”3 In fact, several countries have already adopted a new official diagnosis for schizophrenia.4 Japan now uses the term “integration disorder,” which has significantly reduced the stigma of this brain disorder.5 South Korea changed the name to “attunement disorder.” Hong Kong and Taiwan now use “dysfunction of thought and perception.” Some researchers recommend calling schizophrenia “Bleuler’s syndrome,” a neutral eponymous designation.

One of the most irritating things about the term schizophrenia is the widespread misconception that it means “split personality.” This prompts some sports announcers to call a football team “schizophrenic” if they play well in the first half and badly in the second. The stock market is labeled “schizophrenic” if it goes up one day and way down on the next. No other medical term is misused by the media as often as the term schizophrenia.

Narcissistic personality disorder. The origin of this diagnostic category is the concept of “malignant narcissism” coined by Erich Fromm in 1964, which he designated as “the quintessence of evil.” I strongly object to implying that evil is part of any psychiatric diagnosis. Numerous studies have found structural brain abnormalities (in both gray and white matter) in patients diagnosed with psychopathic traits.6 Later, malignant narcissism was reframed as narcissistic personality disorder in 1971 by Herbert Rosenfeld. Although malignant narcissism was never accepted by either the DSM or the International Classification of Diseases, narcissistic personality disorder has been included in the DSM for the past few decades. This diagnosis reeks of disparagement and negativity. Persons with narcissistic personality disorder have been shown to have pathological brain changes in resting-state functional connectivity,7 weakened frontostriatal white matter connectivity,8,9 and a reduced frontal thickness and cortical volume.10 A distorted sense of self and others is a socially disabling disorder that should generate empathy, not disdain. Narcissistic personality disorder should be replaced by a term that accurately describes its behavioral pathology, and should not incorporate Greek mythology.

Mania. This is another unfortunate diagnosis that immediately evokes a negative image of patients who suffer from a potentially lethal brain disorder. It was fortunate that Robert Kendall coined the term “bipolar disorder” to replace “manic-depressive illness,” but mania is still being used within bipolar disorder as a prominent clinical phase. While depression accurately describes the mood in the other phase of this disorder, the term mania evokes wild, irrational behavior. Because the actual mood symptom cluster in mania is either elation/grandiosity or irritability/anger, why not replace mania with “elation/irritability phase of bipolar disorder”? It is more descriptive of the patient’s mood and is less pejorative.

Nomenclature is vital, and words do matter, especially when used as a diagnostic medical term. Psychiatry must “cancel” its archaic names, which are infused with negative connotations. Reinventing the psychiatric lexicon is a necessary act of renewal in a specialty where a poorly worded diagnostic label can morph into the equivalent of a “scarlet letter.” Think of other contemptuous terms, such as refrigerator mother, male hysteria, moral insanity, toxic parents, inadequate personality disorder, neurasthenia, or catastrophic schizophrenia.

General medicine regularly discards many of its obsolete terms.11 These include terms such as ablepsy, ague, camp fever, bloody flux, chlorosis, catarrh, consumption, dropsy, French pox, phthisis, milk sickness, and scrumpox.

Think also of how society abandoned the antediluvian names of boys and girls. Few parents these days would name their son Ackley, Allard, Arundel, Awarnach, Beldon, Durward, Grower, Kenlm, or Legolan, or name their daughter Afton, Agrona, Arantxa, Corliss, Demelza, Eartha, Maida, Obsession, Radella, or Sacrifice.In summary, a necessary part of psychiatry’s progress is shedding obsolete terminology, even if it means slaughtering some widely used “traditional” vocabulary. It is a necessary act of renewal, and the image of psychiatry will be burnished by it.

1. Nasrallah HA. Borderline personality disorder is a heritable brain disease. Current Psychiatry. 2014;13(4):19-20,32.

2. Sagarwala R, Nasrallah HA. White matter pathology in patients with borderline personality disorder: a review of controlled DTI studies. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2020;32(4):281-286.

3. Keshavan MS, Tandon R, Nasrallah HA. Renaming schizophrenia: keeping up with the facts. Schizophr Res. 2013;148(1-3):1-2.

4. Lasalvia A, Penta E, Sartorius N, et al. Should the label “schizophrenia” be abandoned? Schizophr Res. 2015;162(1-3):276-284.

5. Takahashi H, Ideno T, Okubo S, et al. Impact of changing the Japanese term for “schizophrenia” for reasons of stereotypical beliefs of schizophrenia in Japanese youth. Schizophr Res. 2009;112(1-3):149-152.

6. Johanson M, Vaurio D, Tiihunen J, et al. A systematic literature review of neuroimaging of psychopathic traits. Front Psychiatry. 2020;10:1027.

7. Yang, W, Cun L, Du X, et al. Gender differences in brain structure and resting-state functional connectivity related to narcissistic personality. Sci Rep. 2015;5:10924.

8. Chester DS, Cynam DR, Powell DK, et al. Narcissismis associated with weakened frontostriatal connectivity: a DTI study. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2016;11(7):1036-1040.

9. Nenadic I, Gullmar D, Dietzek M, et al. Brain structure in narcissistic personality disorder: a VBM and DTI pilot study. Psychiatry Res. 2015;231(2):184-186.

10. Mao Y, Sang N, Wang Y, et al. Reduced frontal cortex thickness and cortical volume associated with pathological narcissism. Neuroscience. 2016;378:51-57.

11. Nasrallah HA. The transient truths of medical ‘progress.’ Current Psychiatry. 2014;13(6):23-24.

1. Nasrallah HA. Borderline personality disorder is a heritable brain disease. Current Psychiatry. 2014;13(4):19-20,32.

2. Sagarwala R, Nasrallah HA. White matter pathology in patients with borderline personality disorder: a review of controlled DTI studies. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2020;32(4):281-286.

3. Keshavan MS, Tandon R, Nasrallah HA. Renaming schizophrenia: keeping up with the facts. Schizophr Res. 2013;148(1-3):1-2.

4. Lasalvia A, Penta E, Sartorius N, et al. Should the label “schizophrenia” be abandoned? Schizophr Res. 2015;162(1-3):276-284.

5. Takahashi H, Ideno T, Okubo S, et al. Impact of changing the Japanese term for “schizophrenia” for reasons of stereotypical beliefs of schizophrenia in Japanese youth. Schizophr Res. 2009;112(1-3):149-152.

6. Johanson M, Vaurio D, Tiihunen J, et al. A systematic literature review of neuroimaging of psychopathic traits. Front Psychiatry. 2020;10:1027.

7. Yang, W, Cun L, Du X, et al. Gender differences in brain structure and resting-state functional connectivity related to narcissistic personality. Sci Rep. 2015;5:10924.

8. Chester DS, Cynam DR, Powell DK, et al. Narcissismis associated with weakened frontostriatal connectivity: a DTI study. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2016;11(7):1036-1040.

9. Nenadic I, Gullmar D, Dietzek M, et al. Brain structure in narcissistic personality disorder: a VBM and DTI pilot study. Psychiatry Res. 2015;231(2):184-186.

10. Mao Y, Sang N, Wang Y, et al. Reduced frontal cortex thickness and cortical volume associated with pathological narcissism. Neuroscience. 2016;378:51-57.

11. Nasrallah HA. The transient truths of medical ‘progress.’ Current Psychiatry. 2014;13(6):23-24.

2020: The year a viral asteroid collided with planet earth

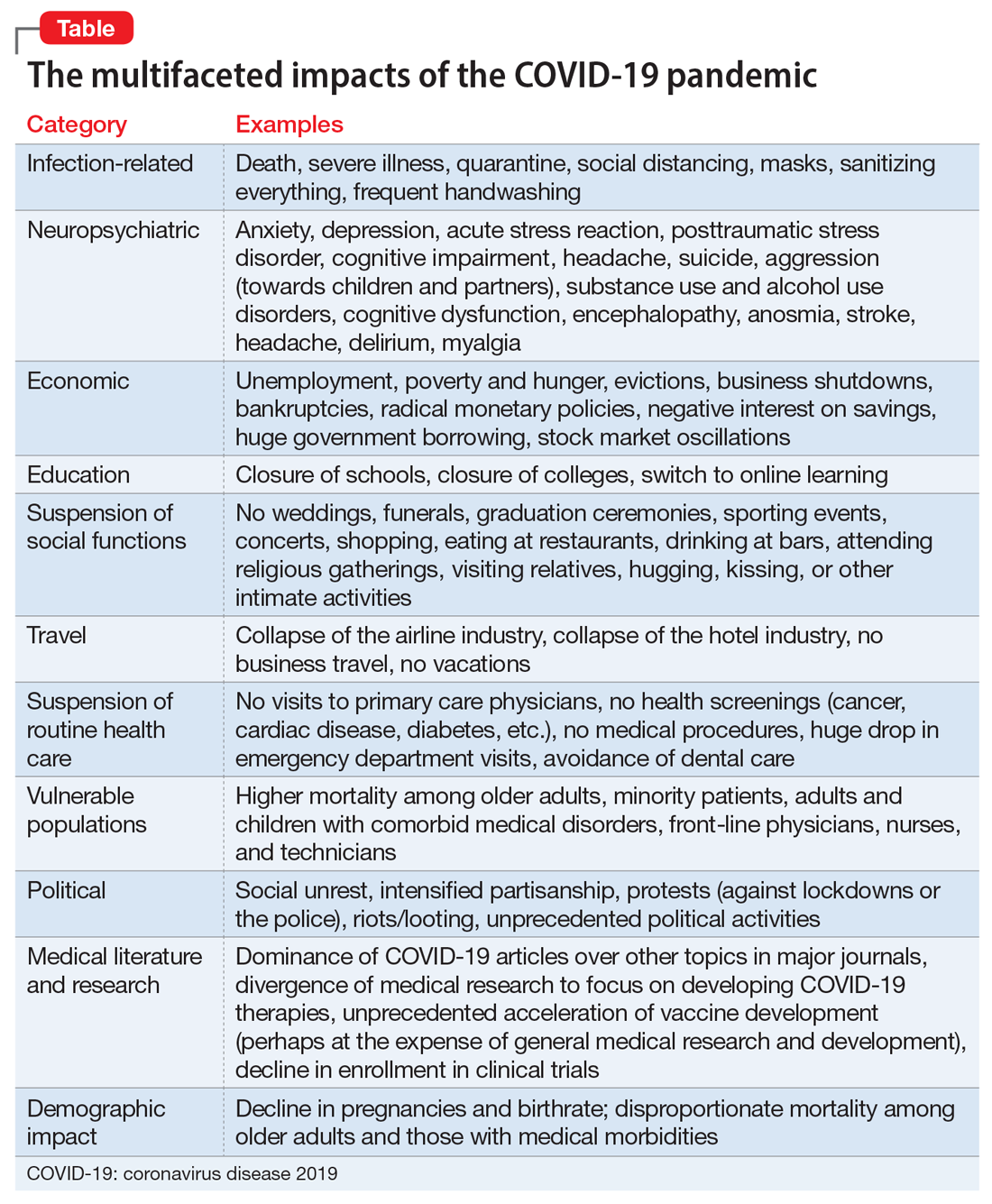

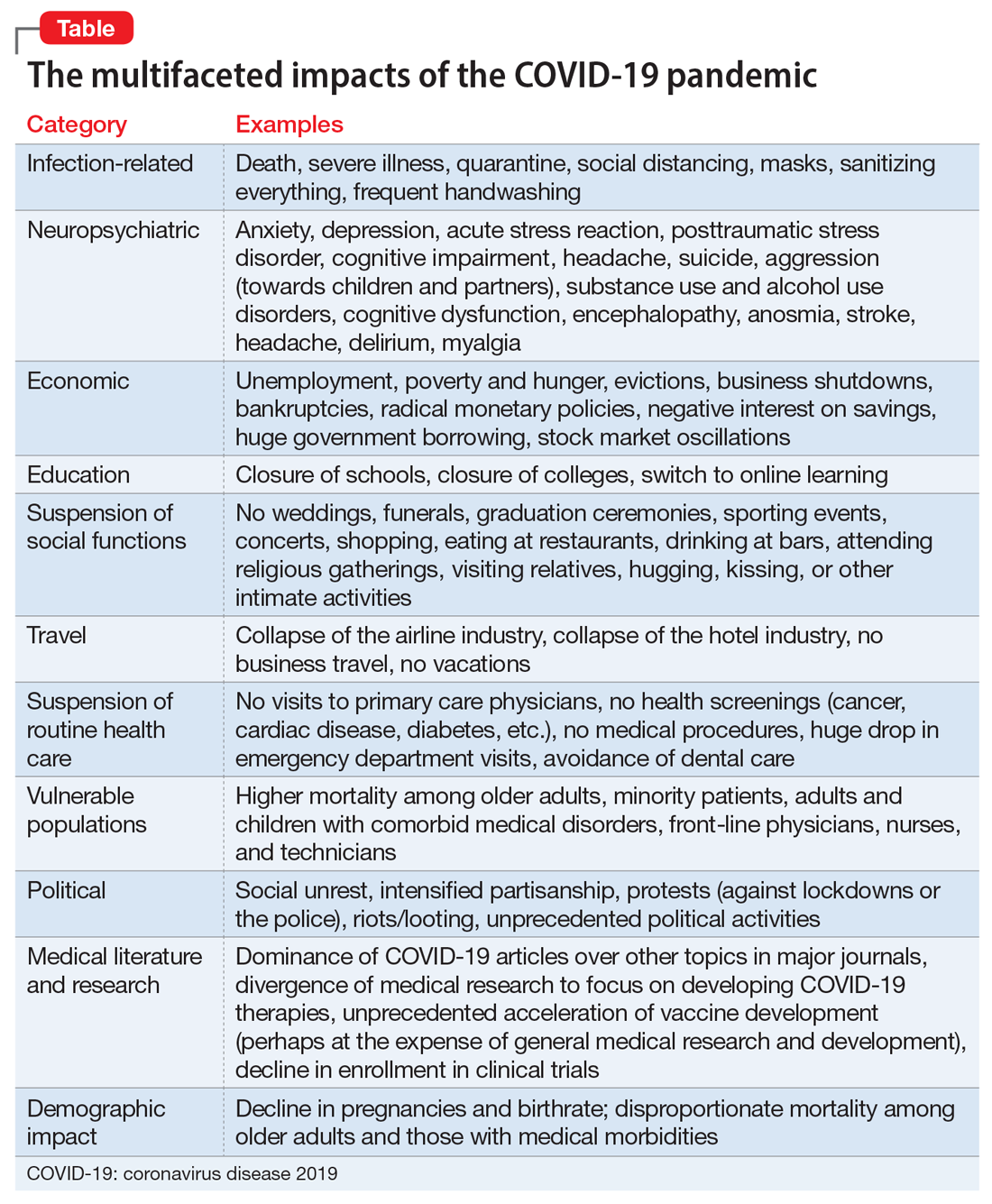

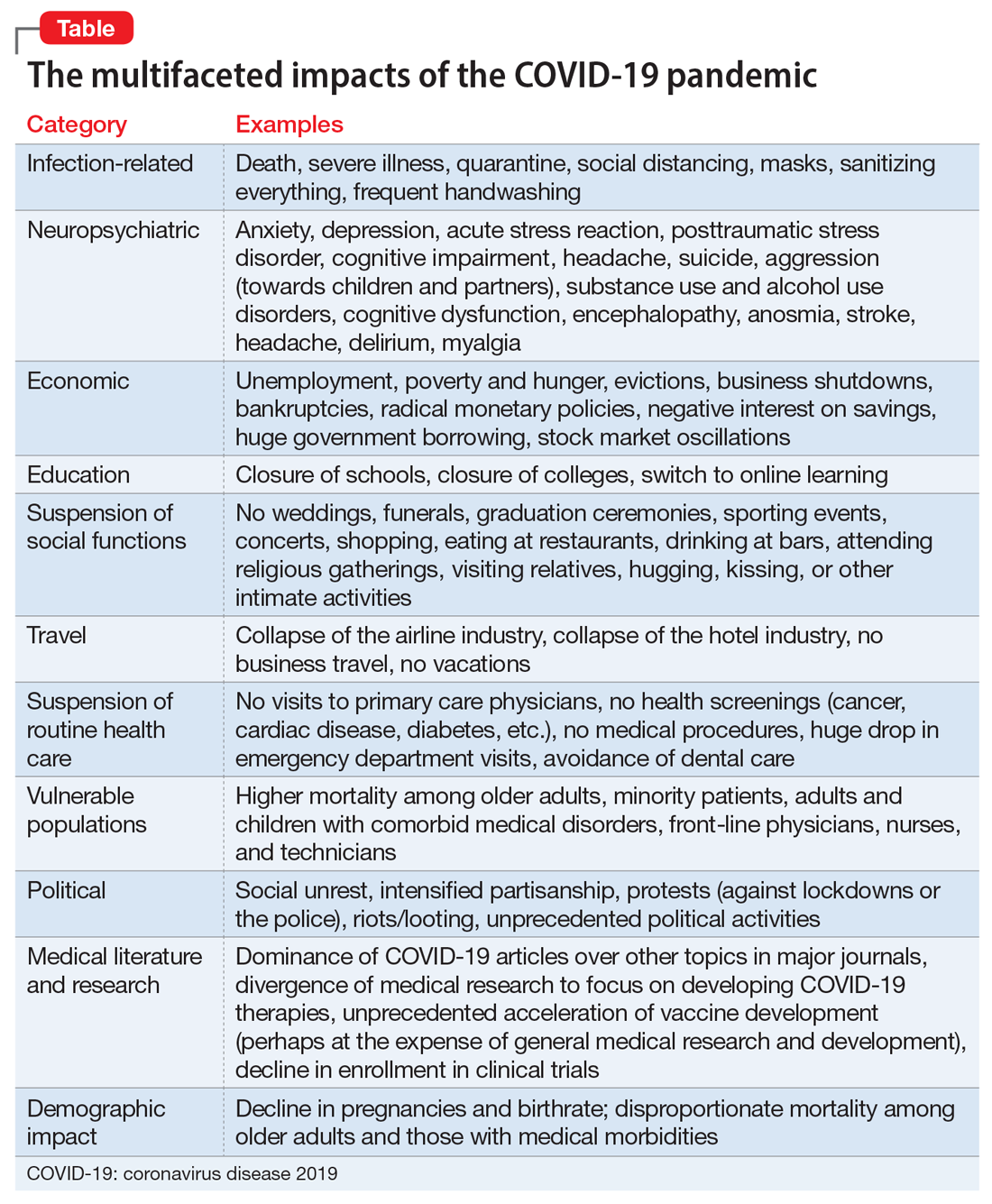

Finally, 2020 is coming to an end, but the agony its viral pandemic inflicted on the entire world population will continue for a long time. And much as we would like to forget its damaging effects, it will surely be etched into our brains for the rest of our lives. The children who suffered the pain of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic will endure its emotional scars for the rest of the 21st century.

Reading about the plagues of the past doesn’t come close to experiencing it and suffering through it. COVID-19 will continue to have ripple effects on every aspect of life on this planet, on individuals and on societies all over the world, especially on the biopsychosocial well-being of billions of humans around the globe.

Unprecedented disruptions

Think of the unprecedented disruptions inflicted by the trauma of the COVID-19 pandemic on our neural circuits. One of the wonders of the human brain is its continuous remodeling due to experiential neuroplasticity, and the formation of dendritic spines that immediately encode the memories of every experience. The turmoil of 2020 and its virulent pandemic will be forever etched into our collective brains, especially in our hippocampi and amygdalae. The impact on the developing brains of our children and grandchildren could be profound and may induce epigenetic changes that trigger psychopathology in the future.1,2

As with the dinosaurs, the 2020 pandemic is like a “viral asteroid” that left devastation on our social fabric and psychological well-being in its wake. We now have deep empathy with our 1918 ancestors and their tribulations, although so far, in the United States the proportion of people infected with COVID-19 (3% as of mid-November 20203) is dwarfed by the proportion infected with the influenza virus a century ago (30%). As of mid-November 2020, the number of global COVID-19 deaths (1.3 million3) was a tiny fraction of the 1918 influenza pandemic deaths (50 million worldwide and 675,000 in the United States4). Amazingly, researchers did not even know whether the killer germ was a virus or a bacterium until 1930, and it then took another 75 years to decode the genome of the influenza virus in 2005. In contrast, it took only a few short weeks to decode the genome of the virus that causes COVID-19 (severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus 2), and to begin developing multiple vaccines “at warp speed.” No vaccine or therapies were ever developed for victims of the 1918 pandemic.

An abundance of articles has been published about the pandemic since it ambushed us early in 2020, including many in

Most psychiatrists are familiar with the Holmes and Rahe Stress Scale,22 which contains 43 life events that cumulatively can progressively increase the odds of physical illness. It is likely that most of the world’s population will score very high on the Holmes and Rahe Stress Scale, which would predict an increased risk of medical illness, even after the pandemic subsides.

Exacerbating the situation is that hospitals and clinics had to shut down most of their operations to focus their resources on treating patients with COVID-19 in ICUs. This halted all routine screenings for cancer and heart, kidney, liver, lung, or brain diseases. In addition, diagnostic or therapeutic procedures such as endoscopies, colonoscopies, angiograms, or biopsies abruptly stopped, resulting in a surge of non–COVID-19 medical disorders and mortality as reported in several articles across many specialties.23 Going forward, in addition to COVID-19 morbidity and mortality, there is a significant likelihood of an increase in myriad medical disorders. The COVID-19 pandemic is obviously inflicting both direct and indirect casualties as it stretches into the next year and perhaps longer. The only hope for the community of nations is the rapid arrival of evidence-based treatments and vaccine(s).

Continue to: A progression of relentless stress

A progression of relentless stress

At the core of this pandemic is relentless stress. When it began in early 2020, the pandemic ignited an acute stress reaction due to the fear of death and the oddness of being isolated at home. Aggravating the acute stress was the realization that life as we knew it suddenly disappeared and all business or social activities had come to a screeching halt. It was almost surreal when streets usually bustling with human activity (such as Times Square in New York or Michigan Avenue in Chicago) became completely deserted and eerily silent. In addition, more stress was generated from watching television or scrolling through social media and being inundated with morbid and frightening news and updates about the number of individuals who became infected or died, and the official projections of tens of thousands or even hundreds of thousands of fatalities. Further intensifying the stress was hearing that there was a shortage of personal protective equipment (even masks), a lack of ventilators, and the absence of any medications to fight the overwhelming viral infection. Especially stressed were the front-line physicians and nurses, who heroically transcended their fears to save their patients’ lives. The sight of refrigerated trucks serving as temporary morgues outside hospital doors was chilling. The world became a macabre place where people died in hospitals without any relative to hold their hands or comfort them, and then were buried quickly without any formal funerals due to mandatory social distancing. The inability of families to grieve for their loved ones added another poignant layer of sadness and distress to the survivors who were unable to bid their loved ones goodbye. This was a jarring example of adding insult to injury.

With the protraction of the exceptional changes imposed by the pandemic, the acute stress reaction transmuted into posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) on a wide scale. Millions of previously healthy individuals began to succumb to the symptoms of PTSD (irritability, hypervigilance, intrusive thoughts, avoidance, insomnia, and bad dreams). The heaviest burden was inflicted on our patients, across all ages, with preexisting psychiatric conditions, who comprise approximately 25% of the population per the classic Epidemiological Catchment Area (ECA) study.24 These vulnerable patients, whom we see in our clinics and hospitals every day, had a significant exacerbation of their psychopathology, including anxiety, depression, psychosis, binge eating disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, alcohol and substance use disorders, child abuse, and intimate partner violence.25,26 The saving grace was the rapid adoption of telepsychiatry, which our psychiatric patients rapidly accepted. Many of them found it more convenient than dressing and driving and parking at the clinic. It also enabled psychiatrists to obtain useful collateral information from family members or partners.

If something good comes from this catastrophic social stress that emotionally hobbled the entire population, it would be the dilution of the stigma of mental illness because everyone has become more empathic due to their personal experience. Optimistically, this may also help expedite true health care parity for psychiatric brain disorders. And perhaps the government may see the need to train more psychiatrists and fund a higher number of residency stipends to all training programs.

Quo vadis COVID-19?

So, looking through the dense fog of the pandemic fatigue, what will 2021 bring us? Will waves of COVID-19 lead to pandemic exhaustion? Will the frayed public mental health care system be able to handle the surge of frayed nerves? Will social distancing intensify the widespread emotional disquietude? Will the children be able to manifest resilience and avoid disabling psychiatric disorders? Will the survivors of COVID-19 infections suffer from post–COVD-19 neuropsychiatric and other medical sequelae? Will efficacious therapies and vaccines emerge to blunt the spread of the virus? Will we all be able to gather in stadiums and arenas to enjoy sporting events, shows, and concerts? Will eating at our favorite restaurants become routine again? Will engaged couples be able to organize well-attended weddings and receptions? Will airplanes and hotels be fully booked again? Importantly, will all children and college students be able to resume their education in person and socialize ad lib? Will we be able to shed our masks and hug each other hello and goodbye? Will scientific journals and social media cover a wide array of topics again as before? Will the number of deaths dwindle to zero, and will we return to worrying mainly about the usual seasonal flu? Will everyone be able to leave home and go to work again?

I hope that the thick dust of this 2020 viral asteroid will settle in 2021, and that “normalcy” is eventually restored to our lives, allowing us to deal with other ongoing stresses such as social unrest and political hyperpartisanship.

1. Baumeister D, Akhtar R, Ciufolini S, et al. Childhood trauma and adulthood inflammation: a meta-analysis of peripheral C-reactive protein, interleukin-6 and tumour necrosis factor-α. Mol Psychiatry. 2016;21(5):642-649.

2. Zatti C, Rosa V, Barros A, et al. Childhood trauma and suicide attempt: a meta-analysis of longitudinal studies from the last decade. Psychiatry Res. 2017;256:353-358.

3. Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/. Accessed November 11, 2020.

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 1918 Pandemic. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/pandemic-resources/1918-pandemic-h1n1.html. Accessed November 4, 2020.

5. Chepke C. Drive-up pharmacotherapy during the COVID-19 pandemic. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(5):29-30.

6. Sharma RA, Maheshwari S, Bronsther R. COVID-19 in the era of loneliness. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(5):31-33.

7. Joshi KG. Taking care of ourselves during the COVID-19 pandemic. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(5):46-47.

8. Frank B, Peterson T, Gupta S, et al. Telepsychiatry: what you need to know. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(6):16-23.

9. Chahal K. Neuropsychiatric manifestations of COVID-19. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(6):31-33.

10. Arbuck D. Changes in patient behavior during COVID-19: what I’ve observed. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(6):46-47.

11. Joshi KG. Telepsychiatry during COVID-19: understanding the rules. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(6):e12-e14.

12. Komrad MS. Medical ethics in the time of COVID-19. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(7):29-32,46.

13. Brooks V. COVID-19’s effects on emergency psychiatry. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(7):33-36,38-39.

14. Desarbo JR, DeSarbo L. Anorexia nervosa and COVID-19. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(8):23-28.

15. Freudenreich O, Kontos N, Querques J. COVID-19 and patients with serious mental illness. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(9):24-27,33-39.

16. Ryznar E. Evaluating patients’ decision-making capacity during COVID-19. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(10):34-40.

17. Saeed SA, Hebishi K. The psychiatric consequences of COVID-19: 8 studies. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(11):22-24,28-30,32-35.

18. Lodhi S, Marett C. Using seclusion to prevent COVID-19 transmission on inpatient psychiatry units. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(11):37-41,53.

19. Nasrallah HA. COVID-19 and the precipitous dismantlement of societal norms. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(7):12-14,16-17.

20. Nasrallah HA. The cataclysmic COVID-19 pandemic: THIS CHANGES EVERYTHING! Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(5):7-8,16.

21. Nasrallah HA. During a viral pandemic, anxiety is endemic: the psychiatric aspects of COVID-19. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(4):e3-e5.

22. Holmes TH, Rahe RH. The social readjustment rating scale. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 1967;11(2):213-218.

23. Berkwits M, Flanagin A, Bauchner H, et al. The COVID-19 pandemic and the JAMA Network. JAMA. 2020;324(12):1159-1160.

24. Robins LN, Regier DA, eds. Psychiatric disorders in America. The Epidemiologic Catchment Area study. New York, NY: The Free Press; 1991.

25. Meninger KA. Psychosis associated with influenza. I. General data: statistical analysis. JAMA. 1919;72(4):235-241.

26. Simon NM, Saxe GN, Marmar CR. Mental health disorders related to COVID-19-related deaths. JAMA. 2020;324(15):1493-1494.

Finally, 2020 is coming to an end, but the agony its viral pandemic inflicted on the entire world population will continue for a long time. And much as we would like to forget its damaging effects, it will surely be etched into our brains for the rest of our lives. The children who suffered the pain of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic will endure its emotional scars for the rest of the 21st century.

Reading about the plagues of the past doesn’t come close to experiencing it and suffering through it. COVID-19 will continue to have ripple effects on every aspect of life on this planet, on individuals and on societies all over the world, especially on the biopsychosocial well-being of billions of humans around the globe.

Unprecedented disruptions

Think of the unprecedented disruptions inflicted by the trauma of the COVID-19 pandemic on our neural circuits. One of the wonders of the human brain is its continuous remodeling due to experiential neuroplasticity, and the formation of dendritic spines that immediately encode the memories of every experience. The turmoil of 2020 and its virulent pandemic will be forever etched into our collective brains, especially in our hippocampi and amygdalae. The impact on the developing brains of our children and grandchildren could be profound and may induce epigenetic changes that trigger psychopathology in the future.1,2

As with the dinosaurs, the 2020 pandemic is like a “viral asteroid” that left devastation on our social fabric and psychological well-being in its wake. We now have deep empathy with our 1918 ancestors and their tribulations, although so far, in the United States the proportion of people infected with COVID-19 (3% as of mid-November 20203) is dwarfed by the proportion infected with the influenza virus a century ago (30%). As of mid-November 2020, the number of global COVID-19 deaths (1.3 million3) was a tiny fraction of the 1918 influenza pandemic deaths (50 million worldwide and 675,000 in the United States4). Amazingly, researchers did not even know whether the killer germ was a virus or a bacterium until 1930, and it then took another 75 years to decode the genome of the influenza virus in 2005. In contrast, it took only a few short weeks to decode the genome of the virus that causes COVID-19 (severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus 2), and to begin developing multiple vaccines “at warp speed.” No vaccine or therapies were ever developed for victims of the 1918 pandemic.

An abundance of articles has been published about the pandemic since it ambushed us early in 2020, including many in

Most psychiatrists are familiar with the Holmes and Rahe Stress Scale,22 which contains 43 life events that cumulatively can progressively increase the odds of physical illness. It is likely that most of the world’s population will score very high on the Holmes and Rahe Stress Scale, which would predict an increased risk of medical illness, even after the pandemic subsides.

Exacerbating the situation is that hospitals and clinics had to shut down most of their operations to focus their resources on treating patients with COVID-19 in ICUs. This halted all routine screenings for cancer and heart, kidney, liver, lung, or brain diseases. In addition, diagnostic or therapeutic procedures such as endoscopies, colonoscopies, angiograms, or biopsies abruptly stopped, resulting in a surge of non–COVID-19 medical disorders and mortality as reported in several articles across many specialties.23 Going forward, in addition to COVID-19 morbidity and mortality, there is a significant likelihood of an increase in myriad medical disorders. The COVID-19 pandemic is obviously inflicting both direct and indirect casualties as it stretches into the next year and perhaps longer. The only hope for the community of nations is the rapid arrival of evidence-based treatments and vaccine(s).

Continue to: A progression of relentless stress

A progression of relentless stress

At the core of this pandemic is relentless stress. When it began in early 2020, the pandemic ignited an acute stress reaction due to the fear of death and the oddness of being isolated at home. Aggravating the acute stress was the realization that life as we knew it suddenly disappeared and all business or social activities had come to a screeching halt. It was almost surreal when streets usually bustling with human activity (such as Times Square in New York or Michigan Avenue in Chicago) became completely deserted and eerily silent. In addition, more stress was generated from watching television or scrolling through social media and being inundated with morbid and frightening news and updates about the number of individuals who became infected or died, and the official projections of tens of thousands or even hundreds of thousands of fatalities. Further intensifying the stress was hearing that there was a shortage of personal protective equipment (even masks), a lack of ventilators, and the absence of any medications to fight the overwhelming viral infection. Especially stressed were the front-line physicians and nurses, who heroically transcended their fears to save their patients’ lives. The sight of refrigerated trucks serving as temporary morgues outside hospital doors was chilling. The world became a macabre place where people died in hospitals without any relative to hold their hands or comfort them, and then were buried quickly without any formal funerals due to mandatory social distancing. The inability of families to grieve for their loved ones added another poignant layer of sadness and distress to the survivors who were unable to bid their loved ones goodbye. This was a jarring example of adding insult to injury.

With the protraction of the exceptional changes imposed by the pandemic, the acute stress reaction transmuted into posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) on a wide scale. Millions of previously healthy individuals began to succumb to the symptoms of PTSD (irritability, hypervigilance, intrusive thoughts, avoidance, insomnia, and bad dreams). The heaviest burden was inflicted on our patients, across all ages, with preexisting psychiatric conditions, who comprise approximately 25% of the population per the classic Epidemiological Catchment Area (ECA) study.24 These vulnerable patients, whom we see in our clinics and hospitals every day, had a significant exacerbation of their psychopathology, including anxiety, depression, psychosis, binge eating disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, alcohol and substance use disorders, child abuse, and intimate partner violence.25,26 The saving grace was the rapid adoption of telepsychiatry, which our psychiatric patients rapidly accepted. Many of them found it more convenient than dressing and driving and parking at the clinic. It also enabled psychiatrists to obtain useful collateral information from family members or partners.

If something good comes from this catastrophic social stress that emotionally hobbled the entire population, it would be the dilution of the stigma of mental illness because everyone has become more empathic due to their personal experience. Optimistically, this may also help expedite true health care parity for psychiatric brain disorders. And perhaps the government may see the need to train more psychiatrists and fund a higher number of residency stipends to all training programs.

Quo vadis COVID-19?

So, looking through the dense fog of the pandemic fatigue, what will 2021 bring us? Will waves of COVID-19 lead to pandemic exhaustion? Will the frayed public mental health care system be able to handle the surge of frayed nerves? Will social distancing intensify the widespread emotional disquietude? Will the children be able to manifest resilience and avoid disabling psychiatric disorders? Will the survivors of COVID-19 infections suffer from post–COVD-19 neuropsychiatric and other medical sequelae? Will efficacious therapies and vaccines emerge to blunt the spread of the virus? Will we all be able to gather in stadiums and arenas to enjoy sporting events, shows, and concerts? Will eating at our favorite restaurants become routine again? Will engaged couples be able to organize well-attended weddings and receptions? Will airplanes and hotels be fully booked again? Importantly, will all children and college students be able to resume their education in person and socialize ad lib? Will we be able to shed our masks and hug each other hello and goodbye? Will scientific journals and social media cover a wide array of topics again as before? Will the number of deaths dwindle to zero, and will we return to worrying mainly about the usual seasonal flu? Will everyone be able to leave home and go to work again?

I hope that the thick dust of this 2020 viral asteroid will settle in 2021, and that “normalcy” is eventually restored to our lives, allowing us to deal with other ongoing stresses such as social unrest and political hyperpartisanship.

Finally, 2020 is coming to an end, but the agony its viral pandemic inflicted on the entire world population will continue for a long time. And much as we would like to forget its damaging effects, it will surely be etched into our brains for the rest of our lives. The children who suffered the pain of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic will endure its emotional scars for the rest of the 21st century.

Reading about the plagues of the past doesn’t come close to experiencing it and suffering through it. COVID-19 will continue to have ripple effects on every aspect of life on this planet, on individuals and on societies all over the world, especially on the biopsychosocial well-being of billions of humans around the globe.

Unprecedented disruptions

Think of the unprecedented disruptions inflicted by the trauma of the COVID-19 pandemic on our neural circuits. One of the wonders of the human brain is its continuous remodeling due to experiential neuroplasticity, and the formation of dendritic spines that immediately encode the memories of every experience. The turmoil of 2020 and its virulent pandemic will be forever etched into our collective brains, especially in our hippocampi and amygdalae. The impact on the developing brains of our children and grandchildren could be profound and may induce epigenetic changes that trigger psychopathology in the future.1,2

As with the dinosaurs, the 2020 pandemic is like a “viral asteroid” that left devastation on our social fabric and psychological well-being in its wake. We now have deep empathy with our 1918 ancestors and their tribulations, although so far, in the United States the proportion of people infected with COVID-19 (3% as of mid-November 20203) is dwarfed by the proportion infected with the influenza virus a century ago (30%). As of mid-November 2020, the number of global COVID-19 deaths (1.3 million3) was a tiny fraction of the 1918 influenza pandemic deaths (50 million worldwide and 675,000 in the United States4). Amazingly, researchers did not even know whether the killer germ was a virus or a bacterium until 1930, and it then took another 75 years to decode the genome of the influenza virus in 2005. In contrast, it took only a few short weeks to decode the genome of the virus that causes COVID-19 (severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus 2), and to begin developing multiple vaccines “at warp speed.” No vaccine or therapies were ever developed for victims of the 1918 pandemic.

An abundance of articles has been published about the pandemic since it ambushed us early in 2020, including many in

Most psychiatrists are familiar with the Holmes and Rahe Stress Scale,22 which contains 43 life events that cumulatively can progressively increase the odds of physical illness. It is likely that most of the world’s population will score very high on the Holmes and Rahe Stress Scale, which would predict an increased risk of medical illness, even after the pandemic subsides.

Exacerbating the situation is that hospitals and clinics had to shut down most of their operations to focus their resources on treating patients with COVID-19 in ICUs. This halted all routine screenings for cancer and heart, kidney, liver, lung, or brain diseases. In addition, diagnostic or therapeutic procedures such as endoscopies, colonoscopies, angiograms, or biopsies abruptly stopped, resulting in a surge of non–COVID-19 medical disorders and mortality as reported in several articles across many specialties.23 Going forward, in addition to COVID-19 morbidity and mortality, there is a significant likelihood of an increase in myriad medical disorders. The COVID-19 pandemic is obviously inflicting both direct and indirect casualties as it stretches into the next year and perhaps longer. The only hope for the community of nations is the rapid arrival of evidence-based treatments and vaccine(s).

Continue to: A progression of relentless stress

A progression of relentless stress

At the core of this pandemic is relentless stress. When it began in early 2020, the pandemic ignited an acute stress reaction due to the fear of death and the oddness of being isolated at home. Aggravating the acute stress was the realization that life as we knew it suddenly disappeared and all business or social activities had come to a screeching halt. It was almost surreal when streets usually bustling with human activity (such as Times Square in New York or Michigan Avenue in Chicago) became completely deserted and eerily silent. In addition, more stress was generated from watching television or scrolling through social media and being inundated with morbid and frightening news and updates about the number of individuals who became infected or died, and the official projections of tens of thousands or even hundreds of thousands of fatalities. Further intensifying the stress was hearing that there was a shortage of personal protective equipment (even masks), a lack of ventilators, and the absence of any medications to fight the overwhelming viral infection. Especially stressed were the front-line physicians and nurses, who heroically transcended their fears to save their patients’ lives. The sight of refrigerated trucks serving as temporary morgues outside hospital doors was chilling. The world became a macabre place where people died in hospitals without any relative to hold their hands or comfort them, and then were buried quickly without any formal funerals due to mandatory social distancing. The inability of families to grieve for their loved ones added another poignant layer of sadness and distress to the survivors who were unable to bid their loved ones goodbye. This was a jarring example of adding insult to injury.

With the protraction of the exceptional changes imposed by the pandemic, the acute stress reaction transmuted into posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) on a wide scale. Millions of previously healthy individuals began to succumb to the symptoms of PTSD (irritability, hypervigilance, intrusive thoughts, avoidance, insomnia, and bad dreams). The heaviest burden was inflicted on our patients, across all ages, with preexisting psychiatric conditions, who comprise approximately 25% of the population per the classic Epidemiological Catchment Area (ECA) study.24 These vulnerable patients, whom we see in our clinics and hospitals every day, had a significant exacerbation of their psychopathology, including anxiety, depression, psychosis, binge eating disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, alcohol and substance use disorders, child abuse, and intimate partner violence.25,26 The saving grace was the rapid adoption of telepsychiatry, which our psychiatric patients rapidly accepted. Many of them found it more convenient than dressing and driving and parking at the clinic. It also enabled psychiatrists to obtain useful collateral information from family members or partners.

If something good comes from this catastrophic social stress that emotionally hobbled the entire population, it would be the dilution of the stigma of mental illness because everyone has become more empathic due to their personal experience. Optimistically, this may also help expedite true health care parity for psychiatric brain disorders. And perhaps the government may see the need to train more psychiatrists and fund a higher number of residency stipends to all training programs.

Quo vadis COVID-19?

So, looking through the dense fog of the pandemic fatigue, what will 2021 bring us? Will waves of COVID-19 lead to pandemic exhaustion? Will the frayed public mental health care system be able to handle the surge of frayed nerves? Will social distancing intensify the widespread emotional disquietude? Will the children be able to manifest resilience and avoid disabling psychiatric disorders? Will the survivors of COVID-19 infections suffer from post–COVD-19 neuropsychiatric and other medical sequelae? Will efficacious therapies and vaccines emerge to blunt the spread of the virus? Will we all be able to gather in stadiums and arenas to enjoy sporting events, shows, and concerts? Will eating at our favorite restaurants become routine again? Will engaged couples be able to organize well-attended weddings and receptions? Will airplanes and hotels be fully booked again? Importantly, will all children and college students be able to resume their education in person and socialize ad lib? Will we be able to shed our masks and hug each other hello and goodbye? Will scientific journals and social media cover a wide array of topics again as before? Will the number of deaths dwindle to zero, and will we return to worrying mainly about the usual seasonal flu? Will everyone be able to leave home and go to work again?

I hope that the thick dust of this 2020 viral asteroid will settle in 2021, and that “normalcy” is eventually restored to our lives, allowing us to deal with other ongoing stresses such as social unrest and political hyperpartisanship.

1. Baumeister D, Akhtar R, Ciufolini S, et al. Childhood trauma and adulthood inflammation: a meta-analysis of peripheral C-reactive protein, interleukin-6 and tumour necrosis factor-α. Mol Psychiatry. 2016;21(5):642-649.

2. Zatti C, Rosa V, Barros A, et al. Childhood trauma and suicide attempt: a meta-analysis of longitudinal studies from the last decade. Psychiatry Res. 2017;256:353-358.

3. Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/. Accessed November 11, 2020.

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 1918 Pandemic. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/pandemic-resources/1918-pandemic-h1n1.html. Accessed November 4, 2020.

5. Chepke C. Drive-up pharmacotherapy during the COVID-19 pandemic. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(5):29-30.

6. Sharma RA, Maheshwari S, Bronsther R. COVID-19 in the era of loneliness. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(5):31-33.

7. Joshi KG. Taking care of ourselves during the COVID-19 pandemic. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(5):46-47.