User login

An Algorithm for Managing Spitting Sutures

Practice Gap

It is well established that surgical complications and a poor scar outcome can have a remarkable impact on patient satisfaction.1 A common complication following dermatologic surgery is suture spitting, in which a buried suture is extruded through the skin surface. When repairing a cutaneous defect following dermatologic surgery, absorbable or nonabsorbable sutures are placed under the skin surface to approximate wound edges, eliminate dead space, and reduce tension on the edges of the wound, improving the cosmetic outcomes.

Absorbable sutures constitute most buried sutures in cutaneous surgery and can be made of natural or synthetic fibers.2 Absorbable sutures made from synthetic fibers are degraded by hydrolysis, in which water breaks down polymer chains of the suture filament. Natural absorbable sutures are composed of mammalian collagen; they are broken down by the enzymatic process of proteolysis.

Tensile strength is lost long before a suture is fully absorbed. Although synthetic fibers have, in general, higher tensile strength and generate less tissue inflammation, they take much longer to absorb.2 During absorption, in some cases, a buried suture is pushed to the surface and extrudes along the wound edge or scar, which is known as spitting3 (Figure 1).

Suture spitting typically occurs in the 2-week to 3-month postoperative period. However, with the use of long-lasting absorbable or nonabsorbable sutures, spitting can occur several months or years postoperatively. Spitting sutures often are associated with surrounding erythema, edema, discharge, and a foreign-body sensation4—symptoms that can be highly distressing to the patient and can lead to postoperative infection or stitch abscess.3

Herein, we review techniques that can decrease the risk for suture spitting, and we present a stepwise approach to managing this common problem.

The Technique

Choice of suture material for buried sutures can influence the risk of spitting.

Factors Impacting Increased Spitting

The 3 most common absorbable sutures in dermatologic surgery include poliglecaprone 25, polyglactin 910, and polydioxanone; of them, polyglactin 910 has been found to have a higher rate of spitting than poliglecaprone 25 and polydioxanone.2 However, because complete absorption of polydioxanone can take as long as 8 months, this suture might “spit” much later than polyglactin 910 or poliglecaprone 25, which typically are fully hydrolyzed by 3 and 4 months, respectively.2 Placing sutures superficially in the dermis has been found to increase the rate of spitting.5 Throwing more knots per closure also has been found to increase the rate of spitting.5

How to Decrease Spitting

Careful choice of suture material and proper depth of suture placement might decrease the risk for spitting in dermatologic surgery. Furthermore, if polyglactin 910 or a long-lasting suture is to be used, sutures should be placed deeply.

What to Do If Sutures Spit

When a suture has begun to spit, the extruding foreign material needs to be removed and the surgical site assessed for infection or abscess. Exposed suture material typically can be removed with forceps without local anesthesia. In some cases, fine-tipped Bishop-Harmon tissue forceps or jewelers forceps might be required.

If the suture cannot be removed completely, it should be trimmed as short as possible. This can be accomplished by pulling on the exposed end of the suture, tenting the skin, and trimming it as close as possible to the surface. Once the foreign material is removed, assessment for signs of infection is paramount.

How to Manage Infection—Postoperative infection associated with a spitting suture can take the form of a periwound cellulitis or stitch abscess.3 A stitch abscess can reflect a sterile inflammatory response to the buried suture or a true infection4; the former is more common.3 In the event of an infected stitch abscess, provide warm compresses, obtain specimens for culture, and prescribe antibiotics after the spitting suture has been removed. Incision and drainage also might be required if notable fluctuance is present.

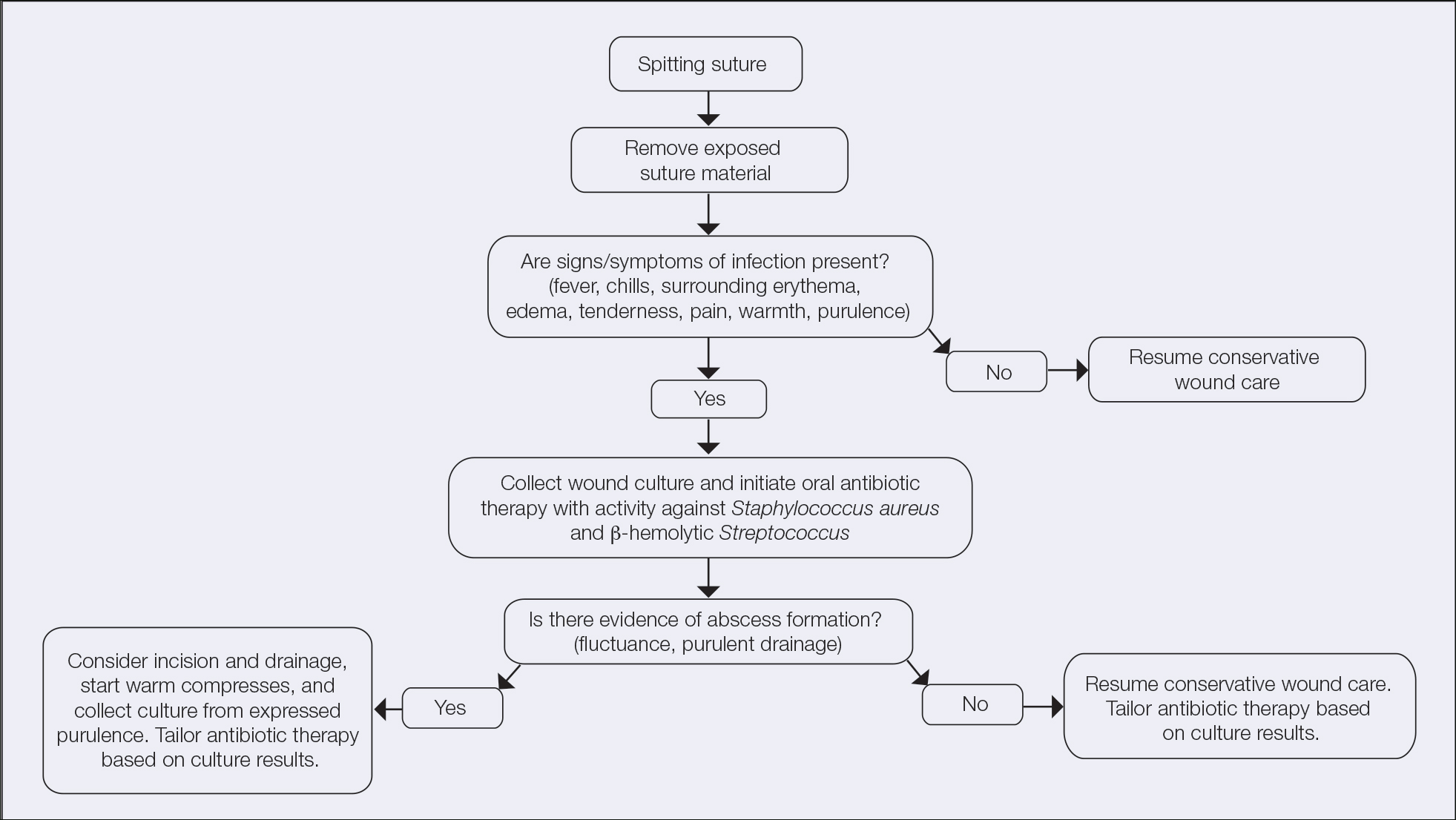

It is crucial for dermatologic surgeons to identify and manage these complications. Figure 2 illustrates an algorithmic approach to managing spitting sutures.

Practical Implications

Spitting sutures are a common occurrence following dermatologic surgery that can lead to remarkable patient distress. Fortunately, in the absence of superimposed infection, spitting sutures have not been shown to worsen outcomes of healing and scarring.5 Nevertheless, it is important to identify and appropriately treat this common complication. The simple algorithm we provide (Figure 2) aids in cutaneous surgery by providing a straightforward approach to managing spitting sutures and their complications.

- Balaraman B, Geddes ER, Friedman PM. Best reconstructive techniques: improving the final scar. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41(suppl 10):S265-S275. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000000496

- Yag-Howard C. Sutures, needles, and tissue adhesives: a review for dermatologic surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2014;40(suppl 9):S3-S15. doi:10.1097/01.DSS.0000452738.23278.2d

- Gloster HM. Complications in Cutaneous Surgery. Springer; 2011.

- Slutsky JB, Fosko ST. Complications in Mohs surgery. In: Berlin A, ed. Mohs and Cutaneous Surgery: Maximizing Aesthetic Outcomes. CRC Press; 2015:55-89.

- Kim B, Sgarioto M, Hewitt D, et al. Scar outcomes in dermatological surgery. Australas J Dermatol. 2018;59:48-51. doi:10.1111/ajd.12570

Practice Gap

It is well established that surgical complications and a poor scar outcome can have a remarkable impact on patient satisfaction.1 A common complication following dermatologic surgery is suture spitting, in which a buried suture is extruded through the skin surface. When repairing a cutaneous defect following dermatologic surgery, absorbable or nonabsorbable sutures are placed under the skin surface to approximate wound edges, eliminate dead space, and reduce tension on the edges of the wound, improving the cosmetic outcomes.

Absorbable sutures constitute most buried sutures in cutaneous surgery and can be made of natural or synthetic fibers.2 Absorbable sutures made from synthetic fibers are degraded by hydrolysis, in which water breaks down polymer chains of the suture filament. Natural absorbable sutures are composed of mammalian collagen; they are broken down by the enzymatic process of proteolysis.

Tensile strength is lost long before a suture is fully absorbed. Although synthetic fibers have, in general, higher tensile strength and generate less tissue inflammation, they take much longer to absorb.2 During absorption, in some cases, a buried suture is pushed to the surface and extrudes along the wound edge or scar, which is known as spitting3 (Figure 1).

Suture spitting typically occurs in the 2-week to 3-month postoperative period. However, with the use of long-lasting absorbable or nonabsorbable sutures, spitting can occur several months or years postoperatively. Spitting sutures often are associated with surrounding erythema, edema, discharge, and a foreign-body sensation4—symptoms that can be highly distressing to the patient and can lead to postoperative infection or stitch abscess.3

Herein, we review techniques that can decrease the risk for suture spitting, and we present a stepwise approach to managing this common problem.

The Technique

Choice of suture material for buried sutures can influence the risk of spitting.

Factors Impacting Increased Spitting

The 3 most common absorbable sutures in dermatologic surgery include poliglecaprone 25, polyglactin 910, and polydioxanone; of them, polyglactin 910 has been found to have a higher rate of spitting than poliglecaprone 25 and polydioxanone.2 However, because complete absorption of polydioxanone can take as long as 8 months, this suture might “spit” much later than polyglactin 910 or poliglecaprone 25, which typically are fully hydrolyzed by 3 and 4 months, respectively.2 Placing sutures superficially in the dermis has been found to increase the rate of spitting.5 Throwing more knots per closure also has been found to increase the rate of spitting.5

How to Decrease Spitting

Careful choice of suture material and proper depth of suture placement might decrease the risk for spitting in dermatologic surgery. Furthermore, if polyglactin 910 or a long-lasting suture is to be used, sutures should be placed deeply.

What to Do If Sutures Spit

When a suture has begun to spit, the extruding foreign material needs to be removed and the surgical site assessed for infection or abscess. Exposed suture material typically can be removed with forceps without local anesthesia. In some cases, fine-tipped Bishop-Harmon tissue forceps or jewelers forceps might be required.

If the suture cannot be removed completely, it should be trimmed as short as possible. This can be accomplished by pulling on the exposed end of the suture, tenting the skin, and trimming it as close as possible to the surface. Once the foreign material is removed, assessment for signs of infection is paramount.

How to Manage Infection—Postoperative infection associated with a spitting suture can take the form of a periwound cellulitis or stitch abscess.3 A stitch abscess can reflect a sterile inflammatory response to the buried suture or a true infection4; the former is more common.3 In the event of an infected stitch abscess, provide warm compresses, obtain specimens for culture, and prescribe antibiotics after the spitting suture has been removed. Incision and drainage also might be required if notable fluctuance is present.

It is crucial for dermatologic surgeons to identify and manage these complications. Figure 2 illustrates an algorithmic approach to managing spitting sutures.

Practical Implications

Spitting sutures are a common occurrence following dermatologic surgery that can lead to remarkable patient distress. Fortunately, in the absence of superimposed infection, spitting sutures have not been shown to worsen outcomes of healing and scarring.5 Nevertheless, it is important to identify and appropriately treat this common complication. The simple algorithm we provide (Figure 2) aids in cutaneous surgery by providing a straightforward approach to managing spitting sutures and their complications.

Practice Gap

It is well established that surgical complications and a poor scar outcome can have a remarkable impact on patient satisfaction.1 A common complication following dermatologic surgery is suture spitting, in which a buried suture is extruded through the skin surface. When repairing a cutaneous defect following dermatologic surgery, absorbable or nonabsorbable sutures are placed under the skin surface to approximate wound edges, eliminate dead space, and reduce tension on the edges of the wound, improving the cosmetic outcomes.

Absorbable sutures constitute most buried sutures in cutaneous surgery and can be made of natural or synthetic fibers.2 Absorbable sutures made from synthetic fibers are degraded by hydrolysis, in which water breaks down polymer chains of the suture filament. Natural absorbable sutures are composed of mammalian collagen; they are broken down by the enzymatic process of proteolysis.

Tensile strength is lost long before a suture is fully absorbed. Although synthetic fibers have, in general, higher tensile strength and generate less tissue inflammation, they take much longer to absorb.2 During absorption, in some cases, a buried suture is pushed to the surface and extrudes along the wound edge or scar, which is known as spitting3 (Figure 1).

Suture spitting typically occurs in the 2-week to 3-month postoperative period. However, with the use of long-lasting absorbable or nonabsorbable sutures, spitting can occur several months or years postoperatively. Spitting sutures often are associated with surrounding erythema, edema, discharge, and a foreign-body sensation4—symptoms that can be highly distressing to the patient and can lead to postoperative infection or stitch abscess.3

Herein, we review techniques that can decrease the risk for suture spitting, and we present a stepwise approach to managing this common problem.

The Technique

Choice of suture material for buried sutures can influence the risk of spitting.

Factors Impacting Increased Spitting

The 3 most common absorbable sutures in dermatologic surgery include poliglecaprone 25, polyglactin 910, and polydioxanone; of them, polyglactin 910 has been found to have a higher rate of spitting than poliglecaprone 25 and polydioxanone.2 However, because complete absorption of polydioxanone can take as long as 8 months, this suture might “spit” much later than polyglactin 910 or poliglecaprone 25, which typically are fully hydrolyzed by 3 and 4 months, respectively.2 Placing sutures superficially in the dermis has been found to increase the rate of spitting.5 Throwing more knots per closure also has been found to increase the rate of spitting.5

How to Decrease Spitting

Careful choice of suture material and proper depth of suture placement might decrease the risk for spitting in dermatologic surgery. Furthermore, if polyglactin 910 or a long-lasting suture is to be used, sutures should be placed deeply.

What to Do If Sutures Spit

When a suture has begun to spit, the extruding foreign material needs to be removed and the surgical site assessed for infection or abscess. Exposed suture material typically can be removed with forceps without local anesthesia. In some cases, fine-tipped Bishop-Harmon tissue forceps or jewelers forceps might be required.

If the suture cannot be removed completely, it should be trimmed as short as possible. This can be accomplished by pulling on the exposed end of the suture, tenting the skin, and trimming it as close as possible to the surface. Once the foreign material is removed, assessment for signs of infection is paramount.

How to Manage Infection—Postoperative infection associated with a spitting suture can take the form of a periwound cellulitis or stitch abscess.3 A stitch abscess can reflect a sterile inflammatory response to the buried suture or a true infection4; the former is more common.3 In the event of an infected stitch abscess, provide warm compresses, obtain specimens for culture, and prescribe antibiotics after the spitting suture has been removed. Incision and drainage also might be required if notable fluctuance is present.

It is crucial for dermatologic surgeons to identify and manage these complications. Figure 2 illustrates an algorithmic approach to managing spitting sutures.

Practical Implications

Spitting sutures are a common occurrence following dermatologic surgery that can lead to remarkable patient distress. Fortunately, in the absence of superimposed infection, spitting sutures have not been shown to worsen outcomes of healing and scarring.5 Nevertheless, it is important to identify and appropriately treat this common complication. The simple algorithm we provide (Figure 2) aids in cutaneous surgery by providing a straightforward approach to managing spitting sutures and their complications.

- Balaraman B, Geddes ER, Friedman PM. Best reconstructive techniques: improving the final scar. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41(suppl 10):S265-S275. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000000496

- Yag-Howard C. Sutures, needles, and tissue adhesives: a review for dermatologic surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2014;40(suppl 9):S3-S15. doi:10.1097/01.DSS.0000452738.23278.2d

- Gloster HM. Complications in Cutaneous Surgery. Springer; 2011.

- Slutsky JB, Fosko ST. Complications in Mohs surgery. In: Berlin A, ed. Mohs and Cutaneous Surgery: Maximizing Aesthetic Outcomes. CRC Press; 2015:55-89.

- Kim B, Sgarioto M, Hewitt D, et al. Scar outcomes in dermatological surgery. Australas J Dermatol. 2018;59:48-51. doi:10.1111/ajd.12570

- Balaraman B, Geddes ER, Friedman PM. Best reconstructive techniques: improving the final scar. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41(suppl 10):S265-S275. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000000496

- Yag-Howard C. Sutures, needles, and tissue adhesives: a review for dermatologic surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2014;40(suppl 9):S3-S15. doi:10.1097/01.DSS.0000452738.23278.2d

- Gloster HM. Complications in Cutaneous Surgery. Springer; 2011.

- Slutsky JB, Fosko ST. Complications in Mohs surgery. In: Berlin A, ed. Mohs and Cutaneous Surgery: Maximizing Aesthetic Outcomes. CRC Press; 2015:55-89.

- Kim B, Sgarioto M, Hewitt D, et al. Scar outcomes in dermatological surgery. Australas J Dermatol. 2018;59:48-51. doi:10.1111/ajd.12570